Abstract

We have devised a novel approach for producing simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) strains and, potentially, human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) strains that are limited to a single cycle of infection. Unlike previous lentiviral vectors, our single-cycle SIV is capable of expressing eight of the nine viral gene products and infected cells release immature virus particles that are unable to complete subsequent rounds of infection. Single-cycle SIV (scSIV) was produced by using a two-plasmid system specifically designed to minimize the possibility of generating replication-competent virus by recombination or nucleotide reversion. One plasmid carried a full-length SIV genome with three nucleotide substitutions in the gag-pol frameshift site to inactivate Pol expression. To ensure inactivation of Pol and to prevent the recovery of wild-type virus by nucleotide reversion, deletions were also introduced into the viral pol gene. In order to provide Gag-Pol in trans, a Gag-Pol-complementing plasmid that included a single nucleotide insertion to permanently place gag and pol in the same reading frame was constructed. We also mutated the frameshift site of this Gag-Pol expression construct so that any recombinants between the two plasmids would remain defective for replication. Cotransfection of both plasmids into 293T cells resulted in the release of Gag-Pol-complemented virus that was capable of one round of infection and one round of viral gene expression but was unable to propagate a spreading infection. The infectivity of scSIV was limited by the amount of Gag-Pol provided in trans and was dependent on the incorporation of a functional integrase. Single-cycle SIV produced by this approach will be useful for addressing questions relating to viral dynamics and viral pathogenesis and for evaluation as an experimental AIDS vaccine in rhesus macaques.

Continuous virus replication is a hallmark of lentiviral infections. Indeed, virus replication persists in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infected individuals and simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV)-infected animals in the face of even the most effective antiretroviral drug therapy and immune surveillance (18, 22). This has complicated efforts to experimentally address certain viral dynamic parameters, such as the burst size of virus production, i.e., the ratio of virus produced per infected cell in vivo. Identification of the first cells to become infected during mucosal transmission has also been difficult to determine unambiguously with replication-competent viruses (9, 27, 32). A system for producing SIV strains that are limited to a single cycle of infection would therefore represent a valuable tool for studies of viral dynamics and viral pathogenesis. Lentiviruses that are limited to a single cycle of infection may also represent a promising approach to the development of an AIDS vaccine with nonhuman primate models.

We have devised an approach for limiting SIV to a single cycle of infection that takes advantage of a unique combination of mutations in the gag-pol frameshift site that are specifically designed to prevent the generation of wild-type virus by recombination. Gag and Gag-Pol are naturally made from the same mRNA transcript at a molar ratio of approximately 20:1 in HIV type 1 (HIV-1)- and SIV-infected cells. This ratio is achieved by ribosomal frameshifting in the region of overlap between the gag and pol reading frames (28). As the precursor to the catalytic subunits of mature virions, Pol is essential for virion maturation and infectivity and its incorporation into assembling virus particles is dependent on its association with Gag (28). The gag-pol frameshift site consists of a conserved seven-nucleotide slippery sequence (UUUUUUA) followed immediately downstream by a region of RNA secondary structure (28). Ribosomal frameshifting physically occurs within the slippery sequence when the tRNAs for phenylalanine and leucine (codons UUU UUA) slip back one nucleotide (−1) relative to the gag frame (UUU UUA→UUU UUU) and translation continues in the pol reading frame (10). By introducing into this site mutations that prevent the translation of Pol and by providing Gag-Pol in trans from an expression construct that also contains mutations in the gag-pol frameshift site, we have developed a two-plasmid system for producing Gag-Pol-complemented virus that is limited to a single round of infection. One of the attractive features of this approach is that neither the mutated viral genome nor the Gag-Pol expression construct retains a functional ribosomal frame shift site. Consequently, even if recombination between these two constructs occurs, the resulting virus will remain defective for replication.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Single-cycle SIV constructs.

Mutations were introduced into the gag-pol frameshift site of SIVmac239 to knock out Pol expression by the virus. A 3,989-bp SpeI-to-SacI fragment of gag-pol was cloned into pBluescript II (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.), and three nucleotide changes were introduced into the frameshift site with the PCR primers −PolFS and FSR (CAGACAGGCGGGCTTCCTAGGCCTTGGTCCATGGGGAAAGAAGCC and TAGGAAGCCCGCCTGTCTGTCTGGGCATTTGGC, respectively) and a QuickChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene). These three nucleotide changes do not change the amino acid coding sequence of gag, and they create a unique AvrII site in the gag-pol frameshift site (26). Deletions of 104, 101, and 105 bp were then introduced into the protease (PR), reverse transcriptase (RT), and integrase (IN) coding regions of pol (nucleotides 2588 to 2691, 2852 to 2951, and 4529 to 4634, respectively (23), with the primer pairs +ΔPR/−ΔPR (AGACCAGTAGTCTAGTAGGAGGAATAGGAGGTTTTATTA/TTCCTCCTACTAGACTACTGGTCTCCTCCAAAGAGAGAA), +ΔRT/−ΔRT (TCTCTAAATTTTTAAGAGAAATCTGTGAAAAGATGGAAA/AGATTTCTCTTAAAAATTTAGAGACATCCCCAGAGCTGT), and +ΔIN/−ΔIN (AGACAAGTTCTCTAGTAGACACCTGTGATAAATGTCATC/AGGTGTCTACTAGAGAACTTGTCTAATCCCTTGACTAAC). These mutations were then cloned into a full-length genome with the gene for enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) at the nef locus (2) by using the unique restriction sites SpeI and PacI.

An expression construct based on pRS102 (24) was created to provide the Gag-Pol polyprotein in trans. In pRS102, the cytomegalovirus (CMV) immediate-early promoter drives Gag-Pol expression and inclusion of the Mason-Pfizer monkey virus cis-transport element (CTE) facilitates Rev-independent nuclear export of gag-pol mRNA transcripts (24). PCR mutagenesis was performed on a 3,989-bp SpeI-to-SacI fragment of gag-pol in pBluescript II with the primers GPfusF2 and GPfusR2 (GCGGGCTTCCTCAGGCCTTGGTCCATGGGGAAAGAAGCC and CCTGAGGAAGCCCGCCTGTCTGTCTGGGCATTTGGC, respectively). These changes were then cloned back into pRS102 to create pGPfusion. By following the same strategy, mutations conferring a combination of three amino acid changes in the active site of integrase (D64Q, D116Q, and E152N) were introduced into pGPfusion to create pGPfusionIN−.

Preparation of virus samples.

Virus was prepared by transient transfection of 293T cells with full-length SIV genomes alone or in combination with a Gag-Pol expression construct. Cells were seeded at 2 × 106 cells per 100-mm dish the day before transfection, and each dish was transfected with 5 μg of each plasmid by calcium phosphate precipitation (ProFection; Promega, Madison, Wis.). Vesicular stomatitis virus glycoprotein (VSV G)-pseudotyped virus was prepared by including 5 μg of the VSV G expression construct pHDM.G in the transfection mix. The day after transfection, the culture medium (Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, l-glutamine, and penicillin) was replaced with a minimal volume (3 ml) of fresh medium. The culture supernatants containing virus particles were harvested 24 h later. The supernatant was either used for infection immediately or concentrated approximately 20-fold by using YM-50 ultrafiltration units (Millipore, Bedford, Mass.) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Because the filtrate is collected by inverse flow in an upper chamber and the virus is never pelleted, ultrafiltration is very gentle and does not significantly reduce virion infectivity. This was demonstrated in a preliminary experiment in which a 25.2-fold concentration, as measured by p27 content (159 to 4,010 ng of p27/ml), translated into a 23.1-fold concentration in single-cycle SIV (scSIV) infectivity (3.6 × 104 to 8.3 × 105 IU/ml on CEMx174 cells).

Infectivity assays and growth curves.

Infectivity assays and growth curves were performed on immortalized human CD4+-T-cell lines, rhesus peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC), and rhesus alveolar macrophages. CD4+-T-cell lines included CEMx174 and T2-SEAP cells. T2-SEAP cells (provided by Welkin Johnson, Harvard Medical School) harbor a Tat-inducible secreted alkaline phosphatase (SEAP) reporter construct enabling SIV infection to be measured by SEAP production in the culture supernatant (20). Rhesus PBMC were isolated from peripheral blood by separation on Ficoll gradients and were activated with phytohemagglutinin (PHA) (1 μg/ml) for 2 days before infection. PHA-activated PBMC were maintained in R10 medium (RPMI 1640 medium with 10% fetal bovine serum, L-glutamine, penicillin, and HEPES buffer) supplemented with 20 U of interleukin-2 (IL-2)/ml (provided by Maurice Gately, Hoffman-La Roche, Nutley, N.J.). Macrophages were collected by bronchoalveolar lavage as previously described (21) and were maintained in 48-well plates in R10 medium supplemented with 5% type AB human serum (Sigma). After 2 days of culture, macrophages were infected at a cell density of 0.5 × 106 cells/well.

Virus samples were diluted in R10 medium and used to infect 106 cells (0.5 × 106 macrophages) in a volume of 100 μl for 2 h. Cultures were then expanded to a volume of 2 ml and maintained at 37°C and 5% CO2. Four days after infection, cells were fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde and analyzed for EGFP expression by using a FACSCalibur flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson). The percentage of EGFP+ cells in the live cell gate was determined after collecting 100,000 to 200,000 events for each sample.

Western blot analysis of virion and cell lysates.

SIV was pelleted from the cell culture supernatants at 13,000 rpm for 4 h at 4°C, and virus pellets were resuspended in 2× sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) sample buffer. Cell lysates were prepared by harvesting in 2× SDS sample buffer (0.5 ml per 100-mm dish) 2 days after transfection. Samples were boiled for 10 min and separated by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE). After electrophoresis, the proteins were transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride membranes (Immobilon-P; Millipore) by using a Trans-Blot SD semidry transfer cell (Bio-Rad, Hercules, Calif.). Blots were blocked in 5% milk-phosphate-buffered saline-Tween and probed with serum pooled from SIV-infected macaques at a 1:200 dilution or a cross-reactive monoclonal antibody to HIV-1 p24 capsid (183-H12-5C [4]; obtained from the NIH AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program) at a 1:400 dilution. Blots were then incubated with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated, goat anti-rhesus (1:1000) or anti-mouse immunoglobulin G1 (1:2000) secondary antibodies (Southern Biotechnology, Birmingham, Ala.) and developed with SuperSignal chemiluminescent substrate (Pierce, Rockford, Ill.). Bands were visualized by using a Fujifilm Image Reader LAS-1000 phosphoimager (Fujifilm Photo Film Co., Japan).

Sequence analysis of proviral DNA.

Genomic DNA was isolated from cryopreserved cell pellets (106 cells) by using a QIAamp DNA Blood Mini Kit (QIAGEN, Valencia, Calif.) according to the manufacturer's instructions. A 414-bp region of the SIV genome spanning the gag-pol frameshift site was amplified by PCR from proviral DNA with the forward and reverse primers 621 (AAAGAGGCCCTCGCACCA) and 626 (TCCAAAGAGAGAATTGAGGTGCA), respectively. PCR products obtained after 50 cycles of denaturation (94°C, 30 sec), annealing (50°C, 40 sec), and extension (72°C, 40 sec) were cloned into the pCR4 sequencing vector by TOPO TA cloning (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, Calif.). Multiple independent clones representing the population of proviral DNA sequences were sequenced with the M13 forward and reverse primers provided with the TOPO TA cloning kit. DNA sequencing reactions were performed by using BigDye v3.1 dye terminator mix (ABI, Foster City, Calif.) and analyzed on a 3730XL ABI capillary sequencer at the University of Washington DNA sequencing facility.

RESULTS

A novel system for producing single-cycle SIV.

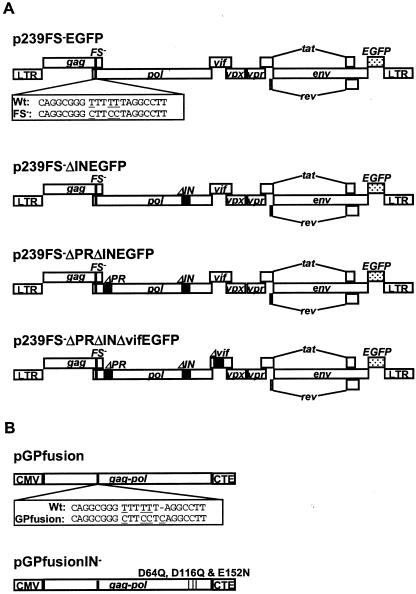

We introduced nucleotide substitutions into the gag-pol frameshift site of the SIVmac239 genome to create a provirus that was capable of expressing all of the viral gene products except Pol. Three T to C changes (TTTTTTA→CTTCCTA) were introduced into the seven-nucleotide slippery sequence of the gag-pol frameshift site. These three nucleotide substitutions inactivated Pol expression by preventing ribosomal frameshifting and were selected in part because they do not change the amino acid sequence of Gag (26). They were incorporated into a full-length SIV genome that also expressed the gene for EGFP from the nef locus (2) to create p239FS−EGFP+ (Fig. 1). Cells infected with this virus therefore express EGFP and can be identified easily by flow cytometry.

FIG. 1.

Plasmid DNA constructs for producing single-cycle SIV. (A) Three nucleotide substitutions were introduced into the gag-pol frameshift site of a full-length SIVmac239 clone carrying the gene for EGFP at the nef locus to create p239FS−EGFP. Derivatives of p239FS−EGFP with different combinations of deletions in the integrase (ΔIN) and protease (ΔPR) coding regions of pol (p239FS−ΔINEGFP and p239FS−ΔPRΔINEGFP) and a deletion in vif (pFS−ΔPRΔINΔvifEGFP) were also created. (B) Two different expression constructs, pGPfusion and pGPfusionIN−, were created to provide Gag-Pol in trans. These constructs were derived from the SIV Gag-Pol expression construct pRS102, which uses the CMV promoter to drive Gag-Pol expression and the MPMV CTE element to facilitate the nuclear export of gag-pol mRNA transcripts in the absence of Rev (24). To create pGPfusion, four nucleotide changes, including a single nucleotide insertion to place gag and pol in the same reading frame, were introduced into the gag-pol frameshift site of pRS102. This construct was subsequently modified by the introduction of mutations that confer three amino acid substitutions in the active site of integrase (D64Q, D116Q, and E152N) to create pGPfusionIN−.

To complement the inability of p239FS−EGFP to express Pol, we created the Gag-Pol expression construct pGPfusion (Fig. 1B). pGPfusion was derived from pRS102 (24), in which Gag-Pol expression is driven by the CMV intermediate-early promoter and Rev-independent nuclear export of the gag-pol mRNA is facilitated by the Mason-Pfizer monkey virus CTE (3). A single nucleotide insertion was introduced into the gag-pol frameshift site of pRS102 to permanently place gag and pol in the same reading frame, and the slippery sequence was disrupted with the same three nucleotide changes that were made in the viral genome (TTTTTTA→CTTCCTCA). Thus, pGPfusion expresses Gag-Pol, but not Gag. Since pGPfusion lacks the major packaging sequences (ψ) upstream of gag, the potential for copackaging and RNA-RNA recombination with the viral genome was greatly reduced.

Together, p239FS−EGFP and pGPfusion constitute a two-plasmid system for producing Gag-Pol-complemented virus by transient transfection. The virus produced by cotransfection of these two plasmid DNA constructs should package a viral genome deficient for Pol expression and therefore be limited to one round of proteolytic maturation, reverse transcription, and proviral integration. The principal advantage of this approach is that it is no longer possible to generate replication-competent virus simply by recombination between the two plasmids, since neither construct retains a functional gag-pol frameshift site.

Gag-Pol-complemented frameshift site mutants are limited to a single cycle of infection.

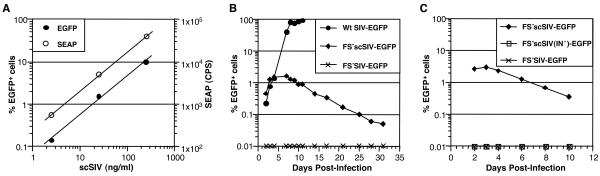

The phenotype of Gag-Pol-complemented SIV with mutations in the frameshift site (FS− scSIV-EGFP) was initially characterized by infection of human CD4+-T-cell lines. The culture supernatants were collected from 293T cells cotransfected with p239FS−EGFP and pGPfusion and used to infect CEMx174 and T2-SEAP cells, which harbor a Tat-inducible SEAP reporter construct (20). Virus infectivity was linearly dose dependent over a 3-log range as measured by the number of EGFP+ cells and by SEAP production 4 days after infection (Fig. 2A). The course of FS− scSIV-EGFP infection was then compared to the frameshift site mutant produced in the absence of pGPfusion (FS− SIV-EGFP) and to wild-type SIV (Wt SIV-EGFP) (Fig. 2B). In cultures infected with the Gag-Pol-complemented virus, the number of EGFP+ cells reached peak levels 3 to 7 days postinfection and steadily declined over the following 3 weeks (Fig. 2B). In contrast, no EGFP+ cells were observed in cultures infected with FS− SIV-EGFP produced in the absence of Gag-Pol-complementation consistent with the requirement for Gag-Pol incorporation in trans to produce infectious virus particles (Fig. 2B). As expected, wild-type virus spread rapidly through infected cultures, resulting in >90% EGFP+ cells by day 11 (Fig. 2B).

FIG. 2.

Properties of single-cycle SIV infection in human CD4+-T-cell lines. (A) FS− scSIV-EGFP was produced by cotransfection of p239FS−EGFP and pGPfusion into 293T cells. T2-SEAP cells containing a Tat-inducible SEAP reporter construct (20) were infected with 2.5, 25, and 250 ng of p27 equivalents of FS− scSIV-EGFP. Four days after infection, infectivity was measured by determining the percentage of EGFP+ cells by flow cytometry and SEAP production in the culture supernatants. (B) CEMx174 cells were infected with FS− scSIV-EGFP, the frameshift site mutant produced in the absence of Gag-Pol-complementation (FS− SIV-EGFP) and the wild-type (Wt SIV-EGFP). The course of infection by each virus was monitored over a 1-month period by determining the percentages of EGFP+ cells by flow cytometry. (C) CEMx174 cells were infected with FS− scSIV-EGFP, an integrase-deficient scSIV [FS− scSIV(IN−)-EGFP], and FS− SIV-EGFP at a dose of 250 ng of SIV p27 equivalents for each virus. FS− scSIV(IN−)-EGFP was produced by cotransfection of 293T cells with p239FS−EGFP and pGPfusionIN−. Since pGPfusionIN− expresses Gag-Pol with three amino acid changes in the active site of integrase (D64Q, D116Q, and E152N), FS− scSIV(IN−)-EGFP particles incorporate a Gag-Pol polyprotein with a functionally inactive integrase and are unable to complete proviral integration. The progress of infection by each of these viruses was monitored by flow cytometry.

Recent evidence suggests that some viral protein expression can occur from unintegrated proviral DNA (31). We therefore determined whether a functional integrase was necessary for EGFP expression in cells infected with our Gag-Pol-complemented frameshift site mutant. Mutations conferring amino acid changes in active site residues of integrase (D64Q, D116Q, and E152N) were introduced into pGPfusion to create pGPfusionIN− (Fig. 1B). Each of these three amino acid changes alone is sufficient to eliminate proviral integration without adversely affecting virion assembly or morphology (5, 16, 29). Thus, the cotransfection of p239FS−EGFP and pGPfusionIN− should produce virus containing functional protease and reverse transcriptase but not integrase [FS− scSIV(IN−)-EGFP]. As with control cultures infected with virus produced in the absence of Gag-Pol complementation, no EGFP+ cells were observed in cultures infected with FS− scSIV(IN−)-EGFP despite the use of a high dose of virus inoculum (250 ng of p27) (Fig. 2C). Indeed, the levels of EGFP expression for FS− scSIV-EGFP were such that 100-fold less EGFP expression by FS− scSIV(IN−)-EGFP infected cells would have been detected readily. Therefore, a functional integrase and presumably integration of proviral DNA appears to be essential for infection by our Gag-Pol-complemented SIV frameshift site mutant.

Deletions in pol and vif were introduced to prevent the recovery of replication-competent virus by nucleotide reversion.

Since p239FS−EGFP only differs from a replication-competent SIV genome by three nucleotides, nucleotide reversions or compensatory changes in the gag-pol frameshift site could conceivably lead to the generation of replication-competent viruses. We therefore introduced additional deletions into the viral genome to further guard against the emergence of replication-competent viruses. Deletions of approximately 100 bp were made in the PR, RT, and IN coding regions of pol (ΔPR 2588-2690, ΔRT 2852-2951, and ΔIN 4529-4634, respectively) (23) in combination with the three nucleotide substitutions in the gag-pol frameshift site to create p239FS−ΔPREGFP, p239FS−ΔRTEGFP, and p239FS−ΔINEGFP. These deletions did not reduce the infectivity of scSIV, since Pol expression by the viral genome was silenced by the disruption of the gag-pol frameshift site (data not shown). However, the deletions decreased the theoretical likelihood that these mutants would regain the capacity to replicate, since both a recombination event in pol and nucleotide reversions in the gag-pol frameshift site would be necessary to restore a replication-competent genome. The original frameshift site mutant was then combined with deletions in both the PR and IN coding regions to create p239FS−ΔPRΔINEGFP so that a double recombination event or a recombination over a large region would be required to restore the complete pol reading frame. As expected, the infectivity of this double-deletion mutant (FS−ΔPRΔIN scSIV-EGFP) did not differ significantly from that of a mutant with a single deletion (FS−ΔIN scSIV-EGFP) (Table 1). The infectivities of these scSIV strains also compared favorably to the infectivity of a stock of wild-type SIVmac239 (540 50% tissue culture infectious dose/ng), which was determined previously with the same cells by limiting dilution.

TABLE 1.

Infectivity titers of single-cycle SIV strains

| scSIV straina | Infectivity titerb

|

|

|---|---|---|

| IU/ng | IU/ml (106) | |

| FS−ΔIN scSIV-EGFP | 262 ± 6.4 | 1.12 ± 0.027 |

| FS−ΔPRΔIN scSIV-EGFP | 294 ± 14.8 | 1.00 ± 0.051 |

| FS−ΔPRΔINΔvif scSIV-EGFP | 609 ± 21.9 | 0.90 ± 0.032 |

Single-cycle SIV stocks were prepared by transient transfection in 293T cells and concentrated approximately 20-fold by ultrafiltration in YM-50 units (Millipore) with a 50-kDa pore size. CEMx174 cells (106) were infected in duplicate with 100 ng of p27 equivalents of each scSIV strain as determined by an SIV p27 antigen capture ELISA (Coulter, Miami, Fla.).

Infectivity titers were measured 4 days after infection and are expressed as the numbers of EGFP+ cells (IU) per nanogram of p27 and per milliliter of virus inoculum. Ranges indicate standard deviations from the means for duplicate wells.

As an additional safeguard to minimize the chances of recovering replication-competent viruses, the mutations were combined with a deletion of 234 nucleotides in vif (7) to create p239FS−ΔPRΔINΔvifEGFP (Fig. 1). Vif is required to overcome a cellular block to infectivity that is imposed by the virus producer cell (6, 25, 30), and while vif deletion mutants produced from most cells are not infectious, vif-deleted viruses produced from certain cell types, such as 293T cells, retain full infectivity. Therefore, under certain circumstances, vif deletion mutants may behave like single-cycle viruses and may be used to back up scSIV mutations in pol. In CEMx174 cells infected with FS−ΔPRΔINΔvif scSIV-EGFP, the incorporation of the vif deletion did not reduce virus infectivity (Table 1). Since the complete vif gene is not present in the Gag-Pol-complementing construct, this deletion cannot be restored by recombination.

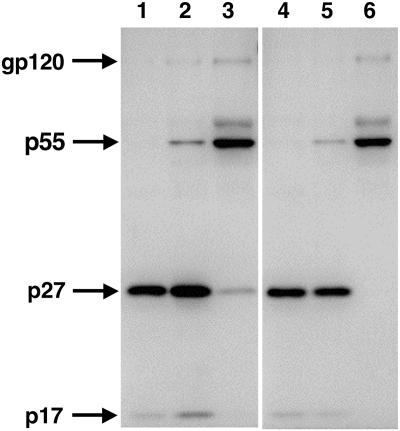

Virus particles released from scSIV-infected cells are unable to complete proteolytic maturation.

Since the nucleotide substitutions in the gag-pol frameshift site were designed to knock out Pol expression from the viral genome, virions released from scSIV-infected cells should be unable to complete proteolytic maturation due to the absence of the viral protease. To confirm this prediction, we infected 221 cells, an IL-2-dependent rhesus macaque CD4+-T-cell line (1), with scSIV and examined the protein profile of virus released from these cells in comparison to samples of wild-type SIV and the scSIV inoculum (Fig. 3). Two different strains of scSIV were used for infection. One contained only the three original nucleotide changes in the frameshift site (FS− scSIV-EGFP), while the other included additional backup deletions in the PR and IN coding regions of pol (FS−ΔPRΔIN scSIV-EGFP). Due to nearly complete proteolytic processing, only the p55Gag cleavage products p27 capsid and p17 matrix were visible for wild-type SIV (Fig. 3, lanes 1 and 4). Similarly, p27 and p17 were the predominant forms of Gag in both scSIV inoculum samples, although a weaker p55 band that was also detected likely reflects suboptimal Gag-Pol incorporation and incomplete proteolytic processing (Fig. 3, lanes 2 and 5). In contrast, virus released from scSIV-infected cells contained predominantly or exclusively unprocessed p55Gag (Fig. 3, lanes 3 and 6). Thus, the protein profile of the virus produced by scSIV-infected cells resembles that of immature virions that are unable to complete proteolytic maturation. A faint p27 band was also observed in virus collected from cells infected with FS− scSIV-EGFP containing only the frameshift site changes (Fig. 3, lane 3), but it was not detected in virus produced by cells infected with FS−ΔPRΔIN scSIV-EGFP carrying additional deletions in protease and integrase (Fig. 3, lane 6). This result suggests that the frameshift site mutations are leaky and may permit a low level of Pol translation.

FIG. 3.

Virus released from scSIV-infected cells is unable to complete proteolytic maturation. The protein profile of scSIV was compared to the protein profile of progeny virus released from scSIV-infected cells. A rhesus T-cell line (221) (1) was infected with FS− scSIV-EGFP and FS−ΔPRΔIN scSIV-EGFP. Four days after infection, the virus released from these cells was harvested and analyzed alongside wild-type SIV and a sample of each scSIV inoculum: wild-type SIV-EGFP (lanes 1 and 4), FS− scSIV-EGFP (lane 2, inoculum; lane 3, progeny virus), and FS−ΔPRΔIN scSIV-EGFP (lane 5, inoculum; lane 6, progeny virus). Viral proteins were separated on a 10% polyacrylamide gel and analyzed by Western blotting with serum pooled from SIV-infected macaques (1:200) and a goat anti-rhesus HRP-conjugated secondary antibody (1:1000). Bands were visualized after development in SuperSignal chemiluminescence substrate (Pierce) by using an Image Reader LAS-1000 phosphoimager (Fujifilm).

Deletions in pol are necessary to prevent virus spread at high multiplicities of infection.

While the frameshift site mutations alone were sufficient to prevent virus spread when the frequency of scSIV infection was limited to <5% (Fig. 2), the finding that these changes may not completely eliminate Pol translation raises the possibility for breakthrough spreading infection at higher multiplicities of infection. We therefore tested for the presence of virus replication under more rigorous assay conditions designed to maximize the numbers of scSIV-infected cells.

CEMx174 cells were infected with concentrated, VSV G-pseudotyped stocks of FS− scSIV-EGFP and FS− ΔPRΔIN scSIV-EGFP. By enabling CD4- and chemokine receptor-independent cell entry, VSV G pseudotyping substantially increased the infectivity of each of these strains, resulting in about 90% infection by day 4 (Fig. 4A). On day 4, the supernatant was collected from the cultures and passed directly to fresh CEMx174 cells. These cultures were then monitored for spreading infection over a period of 3 to 4 weeks. The supernatant from cells infected with FS− scSIV-EGFP resulted in detectable spreading infection by 11 days posttransfer (Fig. 4A). However, there was no evidence of spreading infection after transfer of the supernatant from cells infected with FS−ΔPRΔIN scSIV-EGFP (Fig. 4A). This finding was further confirmed by the inability to detect SIV p27 in the supernatant from FS−ΔPRΔIN scSIV-EGFP cultures by antigen capture enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) on day 25 posttransfer. Thus, at high multiplicities of infection, additional back-up deletions in pol do appear to be necessary to prevent spreading infection.

FIG. 4.

At high multiplicity of infection with VSV G-pseudotyped virus, spreading infection was observed after the supernatant transfer from FS− scSIV-EGFP but not from FS−ΔPRΔIN scSIV-EGFP-infected cells. (A) One million CEMx174 cells were infected with 100 ng of p27 equivalents of concentrated, VSV G-pseudotyped FS− scSIV-EGFP and FS−ΔPRΔIN scSIV-EGFP. Infections were performed in a volume of 100 μl for 2 h, which was then expanded to 2 ml. On day 4 postinfection, 1 ml of the supernatant was passed to one million fresh CEMx174 cells for a total culture volume of 2 ml and these cells were monitored for 3 to 4 weeks. Cells were fixed and analyzed for EGFP expression on day 4 postinfection (PI) and on days 11 and 21 posttransfer (PT). The percentage of infected, EGFP-positive cells is indicated at each time point. (B) An unusual 167-bp deletion was present in sequences amplified from proviral DNA of the FS− scSIV-EGFP culture. Genomic DNA was prepared from cryopreserved cell pellets collected on days 16 and 26 after the supernatant transfer. A 414-bp region of the SIV genome spanning the gag-pol frameshift site was PCR amplified from proviral DNA and cloned into the TOPO TA sequencing vector pCR4. An analysis of multiple independent clones revealed the presence of two predominant proviral sequences within this region. FS− represents the proviral sequence of the FS− scSIV-EGFP inoculum that was present in the majority of clones at each time point. Δ167 contains a unique 167-bp deletion that was identified in 3 of 18 clones on day 16 and 1 of 15 clones on day 26. The predicted amino acid sequences for Gag and Pol and the proteolytic cleavages sites for p2/NC, NC/p6, and transframe (TF)/PR are indicated by ><.

To investigate the mechanism of spreading infection in the FS− scSIV-EGFP culture, we sequenced a region of proviral DNA spanning the p2 coding region of gag through the PR coding region of pol. Genomic DNA was isolated from cells collected on days 16 and 26, and a 414-bp region encompassing the gag-pol frameshift site was PCR amplified from proviral DNA, cloned, and sequenced. Surprisingly, all of the clones retained the original three T→C changes in the slippery sequence, suggesting that spreading infection was not the result of nucleotide reversion. Furthermore, most of the clones represented the predicted sequence for the FS− scSIV-EGFP inoculum. The only new mutation that was consistently observed at each time point was a 167-bp deletion (nucleotides 2177 to 2343) (23) beginning in the p2 coding region of gag and ending seven nucleotides upstream of the mutated slippery sequence (Fig. 4B). This unusual deletion was present in 3 of 18 clones at day 16 and in 1 of 15 clones at day 26.

Interestingly, the deletion eliminated the entire nucleocapsid (NC) coding region of gag and placed the gag and pol genes in the same reading frame. Integrated proviruses containing this mutation are therefore predicted to express a mutated form of Gag-Pol lacking amino acid sequences for NC. These proviruses should also be unable to express p6 residues of Gag, since the p6 coding region downstream of the deletion is out of the frame. Virions produced from this mutant should therefore be defective for replication due to an inability to express NC and p6, which are required for the packaging of viral RNA and the release of virions from infected cells, respectively. Thus, sequence analysis of the FS− scSIV-EGFP culture did not reveal any mutations in proviral DNA predicted to produce replication-competent virus. However, it is conceivable that the observed spreading infection may be due to two defective viral genomes complementing each other. In this case, the 167-bp deletion mutant may provide Gag-Pol to complement the original FS− scSIV genome, allowing both viruses to spread in tandem. This intriguing possibility is supported by the dependence of spread on a high multiplicity of infection and the maintenance of each provirus at early and late stages of infection.

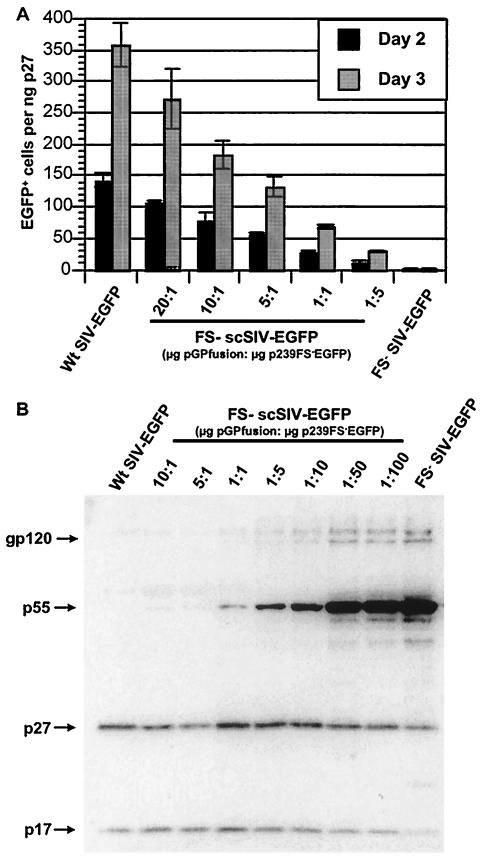

The infectivity of single-cycle SIV is limited by Gag-Pol incorporation in trans.

The infectivity of scSIV was compared to the infectivity of wild-type SIV by normalizing the number of infected cells to the amount of SIV p27 present in the inoculum. CEMx174 cells were infected with FS− scSIV-EGFP prepared by transfection of 293T cells with pGPfusion and p239FS−EGFP at five different plasmid ratios. Cells were analyzed for EGFP expression on days 2 and 3 postinfection, when the majority of the EGFP+ cells in the wild-type SIV infected cultures represented the first round of infection. As the amount of pGPfusion relative to that of p239FS−EGFP was reduced, the infectivity of the virus declined, revealing a dose-dependent relationship between scSIV infectivity and the ratio of the two constructs used to produce the virus (Fig. 5A). Contrary to our initial expectations, the maximal scSIV infectivity was achieved at the highest ratio of pGPfusion to p239FS−EGFP (Fig. 5A). Since the ratio of Gag-Pol to Gag in cells infected with wild-type virus is approximately 1:20, we had predicted that only 1/20 the amount of Gag-Pol expression relative to Gag would be needed to assemble fully infectious virus particles. Thus, the infectivity of scSIV appeared to be limited by the incorporation of Gag-Pol in trans.

FIG. 5.

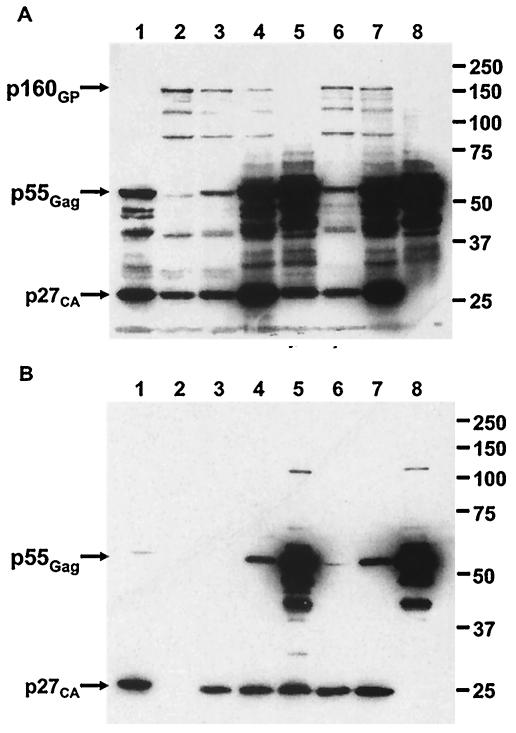

The infectivity of scSIV is dependent on Gag-Pol incorporation in trans. (A) CEMx174 cells were infected with FS− scSIV-EGFP produced at five different plasmid ratios, and the numbers of EGFP+ cells were determined by flow cytometry on days 2 and 3 postinfection. FS− scSIV-EGFP was produced by cotransfection of 293T cells with pGPfusion and p239FS−EGFP at ratios of 20:1 (20:1 μg), 10:1 (10:1 μg), 5:1 (10:2 μg), 1:1 (5:5 μg) and 1:5 (2:10 μg). Control cultures were infected with wild-type SIV-EGFP and FS− SIV-EGFP produced in the absence of pGPfusion. The infectivities of each sample were compared by normalizing the numbers of EGFP+ cells to the amount of SIV p27 present in the inoculum. (B) Virion protein profiles for FS− scSIV-EGFP samples produced at decreasing ratios of pGPfusion to p239FS−EGFP were compared by Western blot analysis. FS− scSIV-EGFP was produced by cotransfection of 293T cells with pGPfusion and p239FS−EGFP at ratios of 10:1 (10:1 μg), 5:1 (5:1 μg), 1:1 (5:5 μg), 1:5 (1:5 μg), 1:10 (0.5:5 μg), 1:50 (0.1:5 μg), and 1:100 (0.05:5 μg). Wt SIV-EGFP and FS− SIV-EGFP were produced by transfection of p239EGFP and p239FS−EGFP, respectively (5 μg each). Virus was pelleted from the culture supernatants and resuspended in SDS-PAGE sample buffer. Five nanograms of SIV p27 equivalents of each viral lysate was separated on an SDS-10% polyacrylamide gel and transferred to a nylon membrane. The blot was probed with pooled serum from SIV-infected macaques (1:200) and goat anti-rhesus HRP-conjugated secondary antibody (1:1000) and was developed by using SuperSignal (Pierce) chemiluminescence substrate. Bands were visualized following a 30-s exposure by using a Fujifilm Image Reader LAS-1000 phosphoimager.

We therefore analyzed the profile of viral proteins in scSIV prepared at decreasing ratios of pGPfusion to p239FS−EGFP. Virus samples were separated by SDS-PAGE and analyzed on a Western blot with serum pooled from SIV-infected animals. Similar to the results for the wild-type virus, the unprocessed p55 Gag band was not visible for scSIV produced at the highest ratios of pGPfusion to p239FS−EGFP (Fig. 5B). However, as the ratio of pGPfusion to p239FS−EGFP was decreased, the p55 Gag band became visible and increased in intensity (Fig. 5B). Due to the intensity of p55 Gag staining at the lower plasmid ratios, only the most abundant viral antigens (gp120, p55, p27, and p17) were visible. We were therefore unable to detect bands corresponding to the Pol cleavage products RT and IN in wild-type or scSIV virions. Since an antigen capture assay that detects p27 CA, but not unprocessed p55 Gag, was used to standardize the amount of virus loaded per lane, the intensity of the gp120 Env band also increased as increasing amounts of immature virus particles were loaded to achieve a constant loading of p27 (Fig. 5B). These results confirm that Gag-Pol incorporation into scSIV particles is reduced at lower transfection ratios of pGPfusion to p239FS−EGFP and corroborate the dose dependence of scSIV infectivity on the ratio of these two plasmids.

The phenomena of cotranslational packaging and assembly may account for the need to transfect excess pGPfusion to achieve wild-type levels of Gag-Pol in virions. According to this model, nascent Gag and Gag-Pol polyproteins preferentially associate with full-length genomic RNA and each other during or immediately after protein translation (8, 13). As a consequence, Gag-Pol expressed in trans from pGPfusion may be at a competitive disadvantage relative to Gag expressed from the FS− viral genome for incorporation into virus particles. Alternatively, the need to provide excess pGPfusion may simply reflect inefficient protein expression from this construct. To differentiate between these two possibilities, we compared the levels of Gag-Pol expression in cells transfected with pGPfusion alone or together with the scSIV genomic constructs p239FS−EGFP and p239FS−ΔPRΔINEGFP to cells transfected with the wild-type proviral construct p239EGFP (Fig. 6A). We also compared the efficiency of proteolytic processing of Gag for virions released from these cells (Fig. 6B).

FIG. 6.

Comparison of Gag and Gag-Pol in producer cells and virions for wild-type and single-cycle SIV. Whole cell lysates (A) and virus pellets (B) were prepared from 293T cells and the culture supernatants 2 days after transfection with wild-type and single-cycle SIV plasmid constructs. Cells were transfected individually with the wild-type proviral construct p239EGFP (lane 1), the Gag-Pol-complementing construct pGPfusion (lane 2), the scSIV genomic constructs p239FS−EGFP (lane 5), and p239FS−ΔPRΔINEGFP (lane 8). Additional cells were cotransfected with pGPfusion plus p239FS−EGFP (lanes 3 and 4) and pGPfusion plus p239FS−ΔPRΔINEGFP (lanes 6 and 7) at ratios of 10:1 and 1:1, respectively. Individual transfections were performed with a total of 6 μg of each plasmid, and cotransfections were performed with a constant mass of pGPfusion (6 μg) together with 0.6 μg (10:1) or 6 μg (1:1) of each scSIV genomic construct. Samples were separated on SDS-8% polyacrylamide gels and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. Western blots were probed with a cross-reactive monoclonal antibody to HIV-1 p24 (183-H12-5C; 1:400) (4) and an HRP-conjugated goat anti-mouse secondary antibody (1:2000). After saturation with SuperSignal chemiluminescence substrate (Pierce), bands were visualized following exposure times of 1 min for cell lysates (A) and 5 min for virus pellets (B).

Western blots of 293T cell lysates and virus pellets were probed with a monoclonal antibody to the HIV-1 capsid protein that cross-reacts with SIV p27 and its polyprotein precursors (4). A 160-kDa band corresponding to Gag-Pol was readily detectable in cells transfected with pGPfusion alone (Fig. 6A, lane 2) and in cells cotransfected at 10:1 and 1:1 ratios with a constant mass of pGPfusion plus either p239FS−EGFP (lanes 3 and 4) or p239FS−ΔPRΔINEGFP (lanes 6 and 7). In contrast, Gag-Pol was not observed in cells transfected with wild-type proviral DNA (Fig. 6A, lane 1) due to the naturally low levels of protein expression afforded by frameshift suppression. The overabundance of Gag-Pol in cells transfected with pGPfusion relative to cells transfected with wild-type proviral DNA suggests that the efficiency of protein expression from pGPfusion is not a limiting factor in the proteolytic maturation of scSIV.

An overabundance of Gag-Pol in cells did not translate into excess unprocessed Gag-Pol in virus particles. In contrast to the results with cell lysates, the 160-kDa Gag-Pol band was not detectable in any of the virus samples regardless of the plasmid ratio used for transfection (Fig. 6B). While the proteolytic processing of p55Gag in wild-type virions (Fig. 6B, lane 1) and in scSIV produced at 10:1 ratios of pGPfusion to p239FS−EGFP and p239FS−ΔPRΔINEGFP (lanes 3 and 6) was nearly complete, p55Gag cleavage remained incomplete at plasmid ratios of 1:1 (Fig. 6B, lanes 4 and 7). These observations further suggest that Gag-Pol incorporation into scSIV is less efficient than in wild-type virus and support a model in which RNA packaging and virus assembly may occur by cotranslational mechanisms.

Single-cycle SIV infection of primary macrophages and T cells.

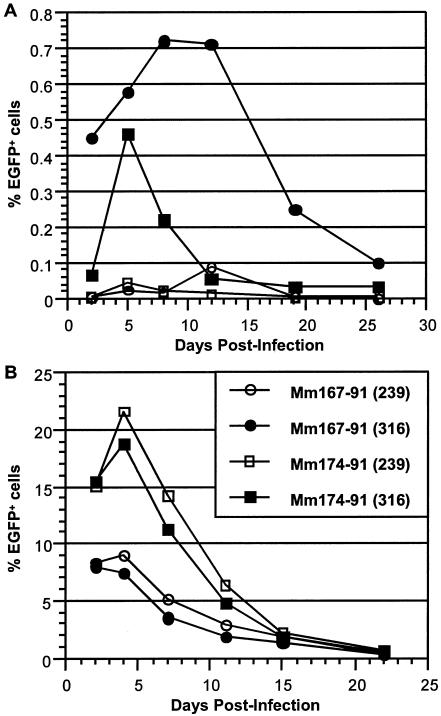

Although SIV infects both CD4+ T cells and macrophages in vivo, productive infection by SIVmac239 is primarily restricted to T cells. To generate a strain of scSIV that was also capable of infecting macrophages, a fragment of the macrophage-tropic SIVmac316 env gene (21), encoding six amino acid differences in gp120 and one amino acid difference ingp41, was exchanged with SIVmac239 env sequences in p239FS−ΔINEGFP. Concentrated stocks of FS−ΔIN scSIVmac239 and FS−ΔIN scSIVmac316 were prepared and used to infect primary alveolar macrophages and PHA-activated PBMC from two different rhesus macaque donors. Similar to the results with scSIV infection of CEMx174 cells, there was an initial increase in the number of infected EGFP+ cells during the first few days after infection followed by a gradual decline of this population over the following weeks of culture (Fig. 7). Both scSIVmac239 and scSIVmac316 were more infectious for PHA-activated PBMC than for macrophages (Fig. 7), and infectivity titers for activated PBMC ranged from 1,196 to 2,880 IU/ng and from 992 to 2,507 IU/ng, respectively (Table 2). However, the infectivity of scSIVmac316 for macrophages was more than 10-fold higher than that of scSIVmac239 (Table 2). These scSIV variants therefore recapitulated the cellular tropism of their parental strains and exhibited a phenotype consistent with a single cycle of infection in primary cell types.

FIG. 7.

Infection of primary macrophages and T cells with single-cycle SIV. Primary alveolar macrophages (A) and PHA-activated PBMC (B) from two different rhesus macaques (Mm167-91 and Mm174-91) were infected with scSIV strains (FS−ΔIN) bearing T-cell-tropic (239) and macrophage-tropic (316) envelope glycoproteins. Infections were monitored by measuring the percentages of EGFP+ cells in each culture by flow cytometry.

TABLE 2.

Relative infectivities of scSIVmac239 and scSIVmac316 for PBMC and macrophages

| Cell type and scSIV strainc | Donor | Infectivity titerd

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| IU/ng | IU/ml (106) | ||

| PBMCa | |||

| scSIVmac239 | Mm 167-91 | 1196 | 7.54 |

| Mm 174-91 | 2880 | 18.15 | |

| scSIVmac316 | Mm 167-91 | 992 | 6.05 |

| Mm 174-91 | 2507 | 15.28 | |

| Macrophageb | |||

| scSIVmac239 | Mm 167-91 | 6.1 | 0.039 |

| Mm 174-91 | 11.7 | 0.074 | |

| scSIVmac316 | Mm 167-91 | 155 | 0.94 |

| Mm 174-91 | 123 | 0.75 | |

Two days after isolation and stimulation with PHA (1 μg/ml), activated PBMC (106) were infected with 75 ng of p27 equivalents of scSIVmac239 and FS−ΔIN scSIVmac316.

Macrophages were collected by bronchoalveolar lavage, and adherent cells (0.5 × 106) were infected with 37.5 ng of p27 equivalents of scSIVmac239 and scSIVmac316 after 2 days in culture.

Single-cycle SIV strains expressing EGFP from the nef locus were prepared by cotransfection of 293T cells with pGPfusion and either p239FS−ΔINEGFP or p316FS−ΔINEGFP. Virus stocks were concentrated approximately 20-fold by ultrafiltration.

Infectivity titers are expressed as the numbers of infected EGFP+ cells per nanogram of p27 and per milliliter of concentrated supernatant. The number of EGFP+ cells was determined on day 4 postinfection for PBMC and on day 5 postinfection for macrophages.

DISCUSSION

We have devised a novel two-plasmid system for producing strains of SIV that are limited to a single cycle of infection. Three nucleotide substitutions were introduced into the heptanucleotide slippery sequence of the SIV gag-pol frameshift site to knock out Pol expression by the virus. To provide Gag-Pol in trans, a Gag-Pol expression construct was created with a single nucleotide insertion to permanently place gag and pol in the same reading frame. Nucleotide changes were also introduced into the frameshift site of this construct so that neither the viral genome nor the complementing construct retained a functional gag-pol frameshift site, thereby preventing the recovery of wild-type virus by recombination alone. To prevent the recovery of replication-competent virus as a result of reversion of changes in the frameshift site, additional back-up deletions were introduced into the pol and vif genes of the viral genome. Together, these constructs constitute a two-plasmid system for producing scSIV by transient transfection that is specifically designed to minimize the chances of generating replication-competent virus by recombination or nucleotide reversion.

In immortalized and primary cells that are permissive for wild-type SIV replication, the numbers of scSIV-infected cells peaked during the initial days after exposure to the virus and then steadily declined as the cultures were maintained over a 3- to 4-week period. Viral protein expression in scSIV-infected cells was dependent on a functional integrase and, presumably, on proviral integration, since EGFP expression became undetectable when a Gag-Pol-complementing construct with mutations in the active site of integrase was used to produce the virus. The initial increase in the numbers of scSIV-infected cells reflects, at least in part, the time required for virus receptor binding, cell entry, reverse transcription, proviral integration, the expression of Tat, and the accumulation of EGFP to detectable levels. Conversely, the relatively slow decline of the scSIV-infected cell population is likely due to the death of infected cells and/or a growth disadvantage of cells harboring integrated proviruses due to cytopathic effects associated with viral protein expression. Potential factors selecting against infected cells include Env-induced cell killing through membrane fusion (17) and cell cycle arrest by the Vpr protein (11). The silencing of proviral gene expression and the loss of EGFP expression as a result of LTR promoter methylation may also have contributed to the apparent decline in the numbers of scSIV-infected cells in these experiments. In either case, the course of infection by scSIV in otherwise permissive cell types is consistent with the phenotype of a virus that is limited to a single round of integration and viral protein expression.

We have not detected any evidence of spreading infection in cultures infected with scSIV at low multiplicities of infection or in cultures infected at higher infectious doses with scSIV strains containing additional back-up deletions in pol. Additionally, we have now inoculated macaques intravenously with multiple concentrated doses (>1010 virus particles) of an scSIV strain carrying a single back-up deletion in the IN coding region of pol and have not observed spreading infection in vivo (D. T. Evans et al., unpublished data). This finding suggests that the combination of nucleotide changes in the gag-pol frameshift site with even a single downstream deletion in pol is sufficient to prevent virus replication at high doses of inoculation in animals—perhaps the most rigorous test for the recovery of replication-competent virus thus far.

Nevertheless, spreading infection was observed following the supernatant transfer from cells infected at a high infectious dose with VSV G-pseudotyped scSIV containing the initial nucleotide substitutions in the gag-pol frameshift site without additional back-up mutations. Sequence analysis of proviral DNA from this culture did not reveal any evidence of nucleotide reversion of the frameshift site mutations. However, an unusual 167-bp deletion was observed in approximately 12% of the clones that eliminated the NC coding region of gag and placed downstream pol sequences in the same reading frame. This provirus is unlikely to produce replication-competent virus, due to an inability to express both NC and p6 sequences of Gag. Thus, we did not identify any proviral mutations expected to produce replication-competent virus. However, since integrated proviruses containing this deletion are predicted to express a mutated form of Gag-Pol, this genome could in principle complement the original frameshift site mutant to enable the tandem spread of both replication-defective genomes through the culture. This possibility is supported by the dependence of spread on a high multiplicity of infection and the observation that the frequency of the deletion mutant did not increase at late stages of infection.

Kuate et al. recently described an alternative approach for producing single-cycle SIV based on nucleotide substitutions in the primer-binding site (PBS) and complementation with an artificial tRNA (15). To further attenuate the virus, additional deletions were introduced into the vif, vpx, vpr, and nef genes. With the possible exception of the deletion in vif, however, none of these back-up deletions are expected to prevent virus replication. Therefore, replication-competent viruses may be recovered by point mutation in the PBS alone, in contrast to our system. Our approaches also differ with respect to the nature of the block to virus replication. After the first round of infection, virus produced by the approach described by Kuate et al. is blocked at the initiation of reverse transcription due to the absence of a cellular tRNA complementary to the mutated PBS sequence. Since we inactivated Pol expression by mutating the gag-pol frameshift site, virus released from cells infected with our scSIV encounters an earlier block at the stage of proteolytic maturation. As a result, our progeny virions have protein profiles that resemble those of immature virus particles. Both approaches retain the expression of similar percentages of overall SIV coding sequences, although the numbers of functional genes retained are quite different. With the exception of a single construct with a deletion in vif, we limited our inactivating mutations to the viral pol gene. We elected to inactivate Pol since it is essential for virus replication, is expressed at relatively low levels in infected cells, and does not appear to represent a major source of epitopes for virus-specific T-cell responses. Our scSIV was therefore designed to retain the expression of eight of the nine viral gene products when EGFP is not included as a reporter gene at the nef locus.

Maximal Gag-Pol incorporation and infectivity of scSIV occurred at the highest ratio of the Gag-Pol expression construct to the frameshift site mutant viral genome. This result was somewhat contrary to expectation since the ratio of Gag-Pol to Gag needed to assemble fully infectious HIV-1 is approximately 1:20 (26). These observations cannot be explained by inefficient protein expression from the Gag-Pol complementing plasmid, since the levels of Gag-Pol expression were higher in cells transfected with pGPfusion than in cells transfected with wild-type proviral DNA. An alternative explanation for the reduced efficiency of Gag-Pol incorporation into scSIV particles is the phenomenon of cotranslational packaging (8, 13). In contrast to HIV-1, the predominant packaging sequences of HIV-2 are located upstream of the major splice donor and are therefore present in both spliced and unspliced mRNA transcripts (19). Since Gag and Gag-Pol are translated from unspliced, full-length genomic RNA, cotranslational packaging has been proposed as a mechanism by which HIV-2, and presumably also SIV, preferentially package unspliced genomic RNA (8, 13). Likewise, the association of Gag-Pol with Gag may also be less efficient when these molecules are translated from separate mRNA transcripts than when they are made from the same mRNA, reflecting a mechanism of cotranslational assembly. In either case, Gag-Pol produced in trans would be at a competitive disadvantage relative to Gag expressed from the viral genome for incorporation into scSIV particles.

The infectivity of our scSIV was nevertheless comparable to the infectivities of other lentiviral vectors based on SIVmac239 (14, 15). After 20-fold concentration, virus titers obtained by cotransfection of equal amounts of the viral genome and the complementing vector were approximately 106 IU/ml for CEMx174 cells. Infectivity titers were 5- to 10-fold higher for PHA-activated rhesus PBMC than for CEMx174 cells, possibly reflecting differences in coreceptor usage or host-specific adaptations of SIV for replication in macaque cells. In comparison, the single-cycle infectivity titer reported by Kuate et al. was 104 IU/ml for the unconcentrated supernatants on S-MAGI cells (15), and the infectivity of an earlier replication-defective SIV vector was determined to be 1.2 × 105 IU/ml for CEMx174 cells (14). Thus, we were able to achieve high infectivity titers, like those obtained with other lentiviral vector systems.

In contrast to lentiviral vectors developed for gene therapy applications (12, 14), our scSIV recombinants are designed to retain the expression of eight of the nine viral gene products. Thus, most cellular interactions of the virus are preserved, as is the potential to elicit diverse virus-specific antibody and T-cell responses. Furthermore, our approach for producing scSIV is specifically designed to prevent the recovery of replication-competent viruses by recombination and nucleotide reversion; this design should enable in vivo studies with high doses of scSIV to be performed with a minimal risk of spreading infection. The inoculation of macaques with single-cycle SIV now affords an opportunity to study aspects of lentiviral infection that have been difficult to address with replication-competent viruses and to develop nonreplicating AIDS vaccine strains.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Public Health Service grants AI10464, AI52751, and AI35365.

We thank Stephen Braun for his helpful suggestions regarding the preparation and concentration of single-cycle SIV and Amy Forand for flow cytometry services.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alexander, L., Z. Du, M. Rosenzweig, J. U. Jung, and R. C. Desrosiers. 1997. A role for natural simian immunodeficiency virus and human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Nef alleles in lymphocyte activation. J. Virol. 71:6094-6099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alexander, L., R. S. Veazey, S. Czajak, M. DeMaria, M. Rosenzweig, A. A. Lackner, R. C. Desrosiers, and V. G. Sasseville. 1999. Recombinant simian immunodeficiency virus expressing green fluorescent protein identifies infected cells in rhesus monkeys. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 15:11-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bray, M., S. Prasad, J. W. Dubay, E. Hunter, K.-T. Jeang, D. Rekosh, and M.-L. Hammarskjöld. 1994. A small element from the Mason-Pfizer monkey virus genome makes human immunodeficiency virus type 1 expression and replication Rev-independent. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91:1256-1260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chesebro, B., K. Wehrly, J. Nishio, and S. Perryman. 1992. Macrophage-tropic human immunodeficiency virus isolates from different patients exhibit unusual V3 envelope sequence homogeneity in comparison with T-cell-tropic isolates: definition of critical amino acids involved in cell tropism. J. Virol. 66:6547-6554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Engleman, A., and R. Craigie. 1992. Identification of conserved amino acid residues critical for human immunodeficiency virus type 1 integrase function in vitro. J. Virol. 66:6361-6369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gabuzda, D. H., K. Lawrence, E. Langhoff, E. Terwilliger, T. Dorfman, W. A. Haseltine, and J. Sodroski. 1992. Role of vif in replication of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 in CD4+ T lymphocytes. J. Virol. 66:6489-6495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gibbs, J. S., D. A. Regier, and R. C. Desrosiers. 1994. Construction and in vitro properties of SIVmac mutants with deletions in “nonessential” genes. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 10:333-342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Griffin, S. D. C., J. F. Allen, and A. M. L. Lever. 2001. The major human immunodeficiency virus type 2 (HIV-2) packaging signal is present on all HIV-2 RNA species: co-translational RNA encapsidation and limitation of Gag protein confer specificity. J. Virol. 75:12058-12069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hu, J., M. B. Gardner, and C. J. Miller. 2000. Simian immunodeficiency virus rapidly penetrates the cervicovaginal mucosa after intravaginal inoculation and infects intraepithelial dendritic cells. J. Virol. 74:6087-6095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jacks, T., M. D. Power, F. R. Masiarz, P. A. Luciw, P. J. Barr, and H. E. Varmus. 1988. Characterization of ribosomal frameshifting in HIV-1 gag-pol expression. Nature 331:280-283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jowett, J. B. M., V. Planelles, B. Poon, N. P. Shah, M.-L. Chen, and I. S. Y. Chen. 1995. The human immunodeficiency virus type 1 vpr gene arrests infected T cells in the G2 + M phase of the cell cycle. J. Virol. 69:6304-6313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kafri, T. 2001. Lentivirus vectors: difficulties and hopes before clinical trials. Curr. Opin. Mol. Ther. 3:316-326. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kaye, J. F., and A. M. L. Lever. 1999. Human immunodeficiency virus types 1 and 2 differ in the predominant mechanism used for selection of genomic RNA for encapsidation. J. Virol. 73:3023-3031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim, S. S., N. Kothari, X. J. You, W. E. Robinson, T. Schnell, K. Uberla, and H. Fan. 2001. Generation of replication-defective helper-free vectors based on simian immunodeficiency virus. Virology 282:154-167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kuate, S., C. Stahl-Hennig, P. ten Haaft, J. Heeney, and K. Uberla. 2003. Single-cycle immunodeficiency viruses provide strategies for uncoupling in vivo expression levels from viral replicative capacity and for mimicking live-attenuated SIV vaccines. Virology 313:653-662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kulkosky, J., K. S. Jones, R. A. Katz, J. P. G. Mack, and A. M. Skalka. 1992. Residues critical for retroviral integrative recombination in a region that is highly conserved among retroviral/retrotransposon integrases and bacterial insertion sequence transposases. Mol. Cell. Biol. 12:2331-2338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.LaBonte, J. A., N. Madani, and J. Sodroski. 2003. Cytolysis by CCR5-using human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope glycoproteins is dependent on membrane fusion and can be inhibited by high levels of CD4 expression. J. Virol. 77:6645-6659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Louie, M., and M. Markowitz. 2002. Goals and milestones during treatment of HIV-1 infection with antiretroviral therapy: a pathogenesis-based perspective. Antivir. Res. 55:15-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McCann, E. M., and A. M. Lever. 1997. Location of cis-acting signals important for RNA encapsidation in the leader sequence of human immunodeficiency virus type 2. J. Virol. 71:4133-4137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Means, R. E., T. Greenough, and R. C. Desrosiers. 1997. Neutralization sensitivity of cell culture-passaged simian immunodeficiency virus. J. Virol. 71:7895-7902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mori, K., D. J. Ringler, T. Kodama, and R. C. Desrosiers. 1992. Complex determinants of macrophage tropism in env of simian immunodeficiency virus. J. Virol. 66:2067-2075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ramratnam, B., J. E. Mittler, L. Zhang, D. Boden, A. Hurley, F. Fang, C. A. Macken, A. S. Perelson, M. Markowitz, and D. D. Ho. 2000. The decay of the latent reservoir of replication-competent HIV-1 is inversely correlated with the extent of residual viral replication during prolonged anti-retroviral therapy. Nat. Med. 6:82-85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Regier, D. A., and R. C. Desrosiers. 1990. The complete nucleotide sequence of a pathogenic molecular clone of simian immunodeficiency virus. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 6:1221-1231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rizvi, T. A., R. D. Schmidt, K. A. Lew, and M. E. Keeling. 1996. Rev/RRE-independent Mason-Pfizer monkey virus constitutive transport element-dependent propagation of SIVmac239 vectors using a single round of replication assay. Virology 222:457-463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sheehy, A. M., N. C. Gaddis, J. D. Choi, and M. H. Malim. 2002. Isolation of a human gene that inhibits HIV-1 infection and is suppressed by the viral Vif protein. Nature 418:646-650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shehu-Xhilaga, M., S. M. Crowe, and J. Mak. 2001. Maintenance of the Gag/Gag-Pol ratio is important for human immunodeficiency virus type 1 RNA dimerization and viral infectivity. J. Virol. 75:1834-1841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Spira, A. I., P. A. Marx, B. K. Patterson, J. Mahoney, R. A. Koup, S. M. Wolinsky, and D. D. Ho. 1996. Cellular targets of infection and route of viral dissemination after intravaginal inoculation of simian immunodeficiency virus into rhesus macaques. J. Exp. Med. 183:215-225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Swanstrom, R., and J. W. Wills. 1997. Synthesis, assembly, and processing of viral proteins, p. 263-334. In J. M. Coffin, S. H. Hughes, and H. E. Varmus (ed.), Retroviruses. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y. [PubMed]

- 29.van Gent, D. C., A. A. M. O. Groeneger, and R. H. A. Plasterk. 1992. Mutational analysis of the integrase protein of human immunodeficiency virus type 2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 89:9598-9602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.von Schwedler, U., J. Song, C. Aiken, and D. Trono. 1993. vif is crucial for human immunodeficiency virus type 1 proviral DNA synthesis in infected cells. J. Virol. 67:4945-4955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wu, Y., and J. W. Marsh. 2001. Selective transcription and modulation of resting T cell activity by preintegrated HIV DNA. Science 293:1503-1506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang, Z.-Q., R. Schuler, M. Zupancic, S. Wietgriefe, K. A. Staskus, K. A. Reimann, T. A. Reinhart, M. Rogan, W. Cavert, C. J. Miller, R. S. Veazey, D. Notermans, S. Little, S. A. Danner, D. D. Richman, D. Havlir, J. Wong, H. L. Jordan, R. W. Schacker, P. Racz, K. Tenner-Racz, N. L. Letvin, S. Wolinsky, and A. T. Haase. 1999. Sexual transmission and propagation of SIV and HIV in resting and activated CD4+ T cells. Science 286:1353-1357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]