Abstract

Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) cDNA synthesis is inhibited in cells from some nonhuman primates by an activity called Lv1. Sensitivity to restriction by Lv1 maps to a region of the HIV-1 CA required for interaction with the cellular protein cyclophilin A. A similar antiviral activity in mammalian cells, Ref1, inhibits reverse transcription of murine leukemia virus (MLV), but only with viral strains bearing N-tropic CA. Disruption of the HIV-1 CA-cyclophilin A interaction inhibits Lv1 restriction in some cells and, paradoxically, seems to render HIV-1 sensitive to Ref1. Lv1 and Ref1 activities are overcome by high-titer infection and are saturable with nonreplicating, virus-like particles encoded by susceptible viruses. Two compounds that disrupt mitochondrial membrane potential, As2O3 and m-Cl-CCP, reduce Ref1 activity. Here we show that these drugs, as well as a third compound with similar effects on mitochondria, PK11195, attenuate Lv1 activity in rhesus macaque and African green monkey cells. Effects of PK11195 and virus-like particles on HIV-1 infectivity in these cells were largely redundant, each associated with increased HIV-1 cDNA. Comparison of acutely infected macaque and human cells suggested that, in addition to effects on cDNA synthesis, Lv1 inhibits the accumulation of nuclear forms of HIV-1 cDNA. Disruption of the HIV-1 CA-cyclophilin A interaction caused a minimal increase in total viral cDNA but increased the proportion of viral cDNA in the nucleus. Consistent with a model in which Lv1 inhibits both synthesis and nuclear translocation of HIV-1 cDNA, complete suppression of macaque or African green monkey Lv1 was achieved by the additive effect of factors that stimulate both processes.

Retroviral tropism is determined in part by host factors necessary for virus replication. For instance, human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) replication in murine cells is impaired at three stages—virion entry, proviral transcription, and virion assembly—due to lack of obligatory factors present in human cells (9, 26, 31, 32, 46). Factors which inhibit viral replication are also important determinants of retroviral tropism. One demonstration of this is that mice bearing particular alleles of Fv1, a gene with homology to endogenous retroviral gag's, are relatively nonpermissive hosts for specific strains of murine leukemia virus (MLV) (8). Curiously, many mammalian species, including humans, exhibit an activity called Ref1 which restricts N-tropic MLV (42), a strain of virus that was identified because of its unique sensitivity to a particular allele of Fv1.

HIV-1 replication in nonhuman primate cells is inhibited by an activity called Lv1, which shares many properties with Fv1 and Ref1 (7, 14, 17, 20, 23, 33, 43). All three activities inhibit retroviral replication at a step following membrane fusion and preceding integration. All can be titrated out by using large quantities of the restricted virus or virus-like particles (VLPs). Another common feature is that viral determinants for sensitivity to all three restriction activities map to the CA region of gag (23, 35, 42, 43).

Ref1 appears to inhibit retroviruses other than N-tropic MLV (17) and, in a conditional fashion, it even appears to inhibit HIV-1 (43). Inhibition of HIV-1 by human Ref1 is only evident when the interaction between HIV-1 CA and the cellular protein cyclophilin A (CypA) is inhibited by CA mutants or by the competitive inhibitor cyclosporine (CsA). Paradoxically, these same factors which render HIV-1 susceptible to Ref1 activity in human cells attenuate Lv1 activity in cells from several nonhuman primates, especially cells from owl monkeys (43). These findings suggest that, by binding to CA, CypA modulates the susceptibility of HIV-1 to these antiviral activities. Lv1 and Ref1 are possibly encoded by related genes (41), but they are clearly distinct from Fv1, which has no homologue in the genome of humans and other primates (8, 42).

Previously our group reported that As2O3 and m-Cl-CCP, two drugs which disrupt the mitochondrial membrane potential, stimulate HIV-1 infection and counteract Ref1 activity (6). Here we show that these drugs, as well as a third compound with similar effects on mitochondria, PK11195, overcome Lv1 activity in cells from rhesus macaques and African green monkeys. We then characterized the effects on HIV-1 replication of these drugs and of other factors which disrupt Lv1 activity. In addition to finding that Lv1 activity in these monkey cells inhibits HIV-1 reverse transcription, we provide evidence that Lv1 may have additional effects on the nuclear translocation of HIV-1 cDNA.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmid DNAs.

pNL4-3 (2) contains a complete infectious HIV-1 provirus, HIV-1NL4-3. pNLΔEN is pNL4-3 with an inactivating mutation in env (5). pNL-GFP, a gift from Dana Gabuzda, is pNL4-3 with an env-inactivating mutation and enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP; Clontech) expressed in place of Nef (18). CSGW, a gift from Greg Towers, is an HIV-1-derived vector expressing EGFP from the cytomegalovirus (CMV) immediate-early promoter (7). pNL-GFP and pNLΔEN containing the G89V mutation were constructed by transfer of the 4.3-kbp SpeI-SalI fragment from pNL4-3 G89V (a gift from Paul Bieniasz). The HIV-1-derived packaging vector p8.9N, a gift from Greg Towers, is pCMVDR8.91 (50) with a NotI restriction site inserted between the CMV immediate-early promoter and the Gag start codon. A 1.8-kbp BglII-SpeI fragment was cut from p8.9N, and the resulting vector (p8.9NDSB) was recircularized after blunt ending the extremities using the Klenow enzyme. To generate the G89V, P90A, and A92E CA(p24) mutant versions of p8.9NDSB, an 821-bp fragment was PCR amplified from the relevant mutated pNL4-3 clones (11), using the following oligonucleotides: forward, 5′-ACGTACGTGCGGCCGCTGGTGAGAGATGGGTGCGAGAGCGTCGGT-3′; reverse, 5′-CCATCTTTTATAGATTTCTCC-3′. The PCR products were digested with NotI and SpeI and ligated to p8.9NDSB cut with the same enzymes. All mutations were confirmed by sequencing. The pMD-G plasmid, encoding the vesicular stomatitis virus G protein (VSV-G), the MLV-derived packaging vectors pCIG3 N and B, and the EGFP-expressing MLV-derived vector pCNCG have been described elsewhere (6). pSIV-GFP, a gift from Paul Bieniasz, contains a simian immunodeficiency virus (SIVMAC239) provirus with an inactivating mutation in env and EGFP expressed in place of Nef (14).

Cells and drugs.

FRhK4 (a gift from Greg Towers) is a fetal rhesus monkey kidney cell line (45). Vero cells (a gift from Vincent Racaniello) are an adult African green monkey kidney cell line (38). FRhK4, Vero, owl monkey kidney (OMK), 293T, HeLa, and Mus dunni tail fibroblast (MDTF) cells (6) were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with antibiotics and 10% fetal calf serum.

As2O3, m-Cl-CCP, and lamivudine (3TC) were prepared as described previously (6). PK11195 (Sigma) was prepared at 100 mM in dimethyl sulfoxide, kept at −20°C, and diluted further in culture medium before use. CsA (Bedford Laboratories) was prepared at 1.5 mg/ml in ethanol, kept at −20°C, and diluted further in culture medium before use.

Production of viral stocks.

To produce HIV-1 virions, 293T cells were transfected as previously described (6) with 10 mg of wild-type or mutant pNL-GFP or pNLDENV and 5 mg of pMD-G. To produce HIV-1 vectors, 293T cells were cotransfected with 10 mg of p8.9NDSB (wild type or mutant), 10 mg of pCSGW, and 5 mg of pMD-G. HIV-1 virion- or vector-containing supernatant was collected 2 days posttransfection, clarified by low-speed centrifugation, filtered (0.45-μm pore size; Pall Acrodisc), and stored at −80°C. Virion quantities were normalized prior to infection using the Perkin-Elmer HIV-1 capsid [CA(p24)] enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit. For SIVMAC239-GFP virions, 239T cells were cotransfected with 10 μg of pSIV-GFP and 5 μg of pMD-G. HIV-1NL-GFP and SIVMAC239-GFP virions were titrated on HeLa cells as described elsewhere (6).

For the MLV-derived vectors, 293T cells were cotransfected with 10 μg of pCNCG, 10 μg of pCIG3 N or B, and 5 μg of pMD-G. Titers were determined on MDTF cells as described previously (42).

To produce VLPs, 293T cells were transfected with 10 μg of p8.9NDSB (wild type or mutant) and 5 μg of pMD-G. VLPs were collected and normalized by CA(p24) ELISA as for HIV-1 virions.

Infections.

Except where indicated, FRhK4 and Vero cells were plated in 12-well plates (1 ml per well) and infected 16 h later. When drugs or VLPs were used, they were added on the cells at the same time as the virus, except for 3TC, which was added 2 h prior to infection. In most experiments, the cell supernatant was exchanged with fresh medium without drugs or virus 16 h after infection. This did not change the efficiency of the infection nor the effects of the drugs, but it significantly reduced the toxic effects associated with PK11195 and As2O3.

Flow cytometry.

For analysis of GFP expression, cells were detached by trypsinization, fixed for 10 min in 2% formaldehyde-phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), washed twice with PBS, and resuspended in PBS at 106 cells/ml. Alternatively, in some experiments, cells were trypsinized, fixed, and then submitted to immune staining of CA(p24) exactly as described before (6). Flow cytometry analysis was done on a FACScalibur using CellQuest software (Becton Dickinson). Intact cells were identified based on light scatter profiles, and only these cells were included in the analysis. GFP and RD1 were recorded on the FL1 and FL2 channels, respectively. A total of 10,000 to 25,000 cells per sample were processed, and cells positive for either marker were gated and counted as the percentage of total intact cells. None of the drugs caused the cells to become fluorescent at the concentrations used.

Monitoring HIV-1 cDNA synthesis.

FRhK4 cells (2 × 106) were infected in 10 ml of medium with VSV-G-pseudotyped HIV-1NL-GFP or HIV-1NLΔEN at multiplicities of infection (MOIs) around 0.1. Cells were washed with PBS at 16 to 26 h and trypsinized. In some experiments, an aliquot (1:20) of the cell suspension was maintained for another 24 h in the absence of any drug, in order to determine the percentage of infected cells by fluorometry. Total cellular DNA was extracted from the remainder of the cells by using the blood and cell culture DNA Midi kit (Qiagen). Two to 5 μg of DNA was digested with a mixture of XhoI, MscI, and DpnI. The products were resolved on agarose gels, transferred to a nylon membrane (Hybond N+; Amersham), and probed with 32P-labeled DNA probes (Rediprime kit; Amersham). Viral DNA was detected with a probe spanning the 5′ MscI site in HIV-1NL4-3 (nucleotides 1818 to 3498 in the provirus). As a control for even loading, the same membrane was rehybridized with a probe specific for mitochondrial DNA that was generated using the following oligonucleotides: 5′-AAGCTTTTCCGGCGCAAC-3′ and 5′-AAGCTTAGTGTTAGGTCT-3′.

RESULTS

Drugs targeting mitochondria counteract Lv1 in rhesus macaque cells.

Our group previously showed that As2O3 counteracts the inhibitory effect of human Ref1 on N-tropic MLV cDNA synthesis (6). Like Ref1, Lv1 anti-HIV-1 activity in rhesus macaque or OMK cells also reduces the amount of viral cDNA generated (7, 14, 33). We therefore tested the effect of As2O3 on HIV-1 replication in OMK cells or FRhK4 macaque cells. As2O3 had no effect on HIV-1 replication in these cells (data not shown), even at concentrations 10 times higher than those which blocked human Ref1 activity (6).

As2O3 was significantly less toxic to the monkey cells than it was to human cell lines (data not shown). We thought this might be relevant, since stimulation of retroviral infectivity by As2O3 correlated with toxic effects of the drug (6). Among known toxic effects of As2O3, permeabilization of the mitochondrial membrane (24, 27) is associated with effects on retroviral replication. Specifically, HIV-1 replication in human cells was enhanced by m-Cl-CCP, a protonophore that, like As2O3, induces apoptosis by disrupting mitochondrial transmembrane potential (6). In rhesus macaque cells, m-Cl-CCP was found to enhance HIV-1 replication (Fig. 1A). PK11195, a ligand of the mitochondrial benzodiazepine receptor that also disrupts mitochondrial membrane integrity (13, 19), similarly enhanced HIV-1 replication in these cells (Fig. 1B). The drugs had no effect on HIV-1 replication in OMK cells (data not shown). m-Cl-CCP and PK11195 stimulated HIV-1 replication at concentrations that were toxic to the macaque cells (data not shown), and concentrations greater than those shown in Fig. 1 could not be used. Stimulation of HIV-1 replication by these drugs was nonetheless specific, since other toxic compounds—camptothecin, cisplatin, or anti-Fas antibody—did not have the same effect (6). For unknown reasons, we observed that the optimal drug concentration for stimulating virus replication varied modestly after cells were maintained in tissue culture for several months.

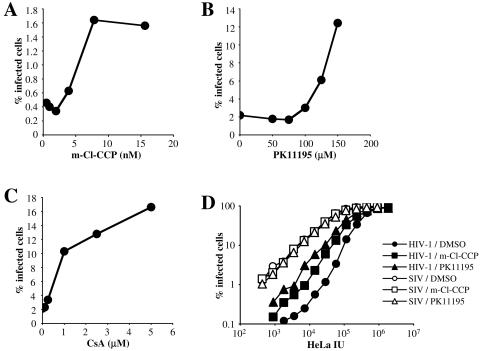

FIG. 1.

(A to C) m-Cl-CCP, PK11195, and CsA each counteract Lv1 activity in rhesus macaque cells. FRhK4 cells were infected with VSV-G-pseudotyped HIV-1NL-GFP in the presence of the indicated concentrations of m-Cl-CCP (A), PK11195 (B), or CsA (C). Supernatant was replaced with drug-free medium 16 h postinfection, and the percentage of cells expressing GFP was determined 2 days later by flow cytometry. (D) FRhK4 cells were infected with VSV-G-pseudotyped virus, either HIV-1NL-GFP or SIVMAC239-GFP, after normalizing the titer of the two viruses on HeLa cells (HeLa IU). Where indicated, infections were performed in the presence of 100 μM PK11195 or 10 nM m-Cl-CCP. GFP expression was analyzed by flow cytometry at 48 h.

HIV-1 replication in FRhK4 cells was also stimulated by CsA, with maximal effect occurring at roughly 5 μM (Fig. 1C). In contrast to PK11195 and m-Cl-CCP, CsA exhibited no detectable toxicity, even at concentrations up to 10 μM (data not shown). The stimulatory effect of CsA on HIV-1 replication in monkey cells was not observed with SIVMAC239, indicating that the drug works by counteracting Lv1 (43). We then determined if the effects of PK11195 and m-Cl-CCP were also specific to HIV-1. Stocks of SIVMAC239 and HIV-1 were normalized based on titer in HeLa cells and then used to challenge macaque FRhK4 cells (Fig. 1D). In the absence of drug, SIVMAC239 was about 50 times more infectious than HIV-1. m-Cl-CCP and PK11195 increased HIV-1 infectivity roughly four- and eightfold, respectively, over a range of MOIs. Neither drug had a significant effect on SIVMAC239 replication, but they specifically counteracted Lv1 activity.

Distinct effects of CsA and PK11195 on HIV-1 cDNA synthesis in macaque cells.

CsA and PK11195 both partially rescued HIV-1 replication in macaque FRhK4 cells. Since Lv1 inhibits HIV-1 cDNA synthesis, we then examined the effects of each drug on HIV-1 cDNA synthesis acutely after infection of FRhK4 cells by using Southern blotting. This assay permits simultaneous quantitation of full-length linear cDNA, 1-long terminal repeat (1-LTR) circles, and 2-LTR circles (6, 49). The circular DNAs are produced in the nucleus and serve as markers for nuclear translocation of viral cDNA (10, 15, 28, 49). In addition, a DNA fragment detected in this assay that we call “total” was present within all major viral DNA forms, including proviral DNA (Fig. 2A).

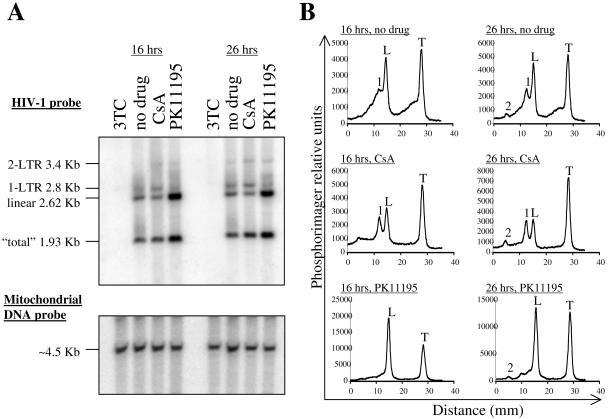

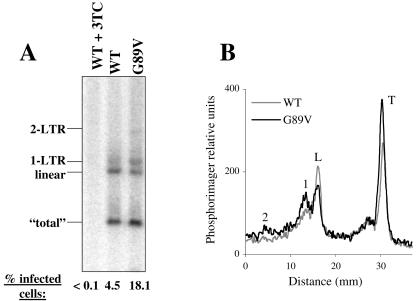

FIG. 2.

Effect of CsA and PK11195 on HIV-1 cDNA synthesis. (A) FRhK4 cells were infected with VSV-G-pseudotyped HIV-1 for 16 or 26 h in the presence of PK11195, CsA, or the reverse transcriptase inhibitor 3TC. Total cellular DNA was extracted, digested with XhoI, MscI, and DpnI, and processed for Southern blotting. The membrane was probed with an HIV-1-specific DNA probe (top) and then stripped and reprobed for human mitochondrial DNA (bottom). Viral DNA species are identified on the left of the blot. The total band corresponds to a DNA fragment that is part of all viral DNA species, including proviral DNA. (B) Plots of signal intensity for the indicated lanes from panel A, as determined with a phosphorimager. The main viral DNA species are indicated above the peaks. 2, 2-LTR circle; 1, 1-LTR circle; L, linear; T, total. Note differences in scales between panels.

FRhK4 cells were infected with HIV-1 for 16 or 26 h in the presence of CsA (2.5 μM), PK11195 (100 μM), or the reverse transcriptase inhibitor 3TC. The MOI was adjusted so that 5 to 10% of cells were infected in the absence of drug. Cells were lysed and processed for Southern blotting using probes specific for HIV-1 and for mitochondrial DNA as a control for equal loading. No signal was observed in the presence of 3TC, indicating that all signal from HIV-1 cDNA arose from de novo synthesis. In the absence of drug, total and linear cDNA were readily detected (Fig. 2A). Signal intensity for 1-LTR product was relatively faint at both 16 and 26 h postinfection, and the 2-LTR circles were barely detectable. The most obvious effect due to addition of CsA was an increase in the relative amount of 1-LTR circles (see quantitation in Fig. 2B). In contrast to CsA, PK11195 strongly increased the amount of linear and total cDNA (eight- and fourfold, respectively) but had no effect on the formation of 1-LTR DNA. This indicated that CsA and PK11195 counteract Lv1 via different mechanisms. We attempted to examine the combined effects of the two drugs on HIV-1 replication; however, this drug mixture was too toxic in FRhK4 cells for the assessment of HIV-1 infectivity (data not shown).

The effects of CsA suggested that, in addition to inhibiting reverse transcription, Lv1 might block nuclear transport of HIV-1 cDNA. To test this idea, we compared HIV-1 cDNA synthesis in FRhK4 and in human rhabdomyosarcoma TE671 cells (Fig. 3A). Analysis of the percentage of infected cells showed that HIV-1 was 11-fold more infectious in TE671 than in FRhK4 cells. However, the total amount of HIV-1 cDNA was only two to three times higher in TE671 cells. In TE671 cells, 1-LTR circles were as abundant as the linear DNA, while in FRhK4 cells the former were undetectable. In HeLa cells, the amount of 1-LTR DNA was almost equivalent to that of linear DNA, and in U937 and Jurkat T cells the amount of 1-LTR DNA was greater than the amount of the linear form (Fig. 3B). These results suggest that nuclear transport of HIV-1 cDNA is inefficient in FRhK4 cells and support the idea that Lv1 inhibits not just HIV-1 cDNA synthesis but also its transport to the nucleus.

FIG. 3.

Southern analysis of HIV-1 cDNA synthesis in rhesus macaque and human cell lines. (A) Comparison of HIV-1 cDNA species in FRhK4 and human TE671 cells infected for 16 h with the same quantity of VSV-G-pseudotyped HIV-1NL-GFP. An aliquot of each sample was maintained in culture for 2 days, and the percentage of GFP-positive cells was determined by flow cytometry. (B) Southern analysis of HIV-1 cDNA synthesis in HeLa, U937, and Jurkat T cells, as described in the legend for Fig. 2.

HIV-1 gag mutations that disrupt CypA binding decrease sensitivity to restriction by macaque Lv1.

Binding of CypA to CA is necessary for full infectivity of HIV-1 in human cells (12). Recently, it was reported that the G89V mutation in HIV-1 CA, which disrupts binding to CypA, completely suppressed Lv1 restriction in owl monkey cells but not in macaque FRhK4 cells (43). We revisited this last result, testing the effect of the G89V mutation on HIV-1 infection in FRhK4 cells. Included in this analysis were two additional mutants, P90A, which like G89V does not bind CypA and decreases HIV-1 infectivity in human cells, and A92E, which has a cell type-dependent effect on HIV-1 replication in human cells (1, 48). The three mutations were engineered into HIV-1-derived vectors expressing GFP, and virus stocks were normalized using a p24 ELISA and a reverse transcription assay. Both G89V and P90A enhanced HIV-1 infectivity by about fourfold compared to the wild-type vector (Fig. 4A); the A92E mutation had no effect. Thus, mutations that disrupt the CypA-binding site of CA partially counteract the restriction to HIV-1 replication in FRhK4 cells.

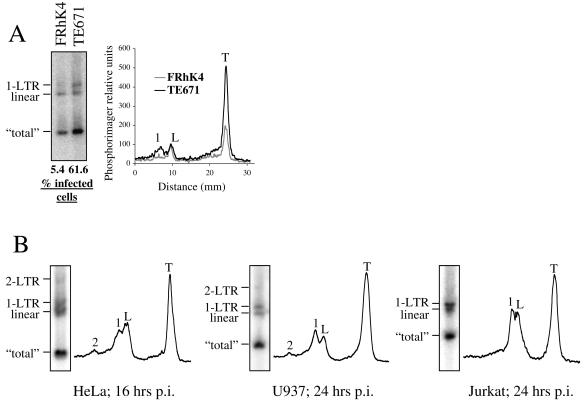

FIG. 4.

Disruption of the interaction between CypA and CA increases HIV-1 infectivity in rhesus macaque cells. FRhK4 cells were infected with GFP-transducing HIV-1 vectors (A and B) or viruses (B to E), either wild type or bearing the indicated CA mutations, in the presence of PK11195 or CsA (B to D) or in the presence of VLPs (E). Supernatant was replaced with drug-free medium 16 h later, and the percentage of GFP-expressing cells was determined 2 days later. The inset in panel E shows the average magnitude increase in infectivity due to addition of wild-type or G89V VLPs, when the percentage of infected cells in the absence of VLPs was less than 2%.

Next, we tested the effect of CsA or PK11195 on wild-type or G89V HIV-1 vectors or viruses. Identical amounts of either wild-type or G89V particles (normalized by p24 ELISA) were used to infect FRhK4 cells in the presence of PK11195 (150 μM) or CsA (5 μM). As shown in Fig. 4B, G89V had a similar enhancing effect on replication (four- to fivefold) in the context of either HIV-1NL-GFP or the HIV-1 vector. Similarly, CsA had the same six- to eightfold effect on wild-type HIV-1 vectors or viruses. In contrast, PK11195 had a much bigger effect on infection by wild-type HIV-1 virus (eightfold) than that by wild-type HIV-1 vectors (twofold). This result echoed the lack of a significant effect of As2O3 on vector replication in human cells (6). We speculate that differential sensitivity to restriction factors may result from the more stringent requirements for reverse transcription of a complete viral genome than for a partial vector genome.

Interestingly, CsA had no additional effect on G89V vectors or viruses. Similarly, PK11195 enhanced G89V virus replication twofold, compared to eightfold for the wild type. However, the MOIs in the absence of the drug were different (0.9% for the wild type, 4.6% for G89V). Therefore, we next tested the effects of CsA and PK11195 on wild-type and G89V HIV-1 at multiple virus doses. As shown in Fig. 4C, the replication of wild-type HIV-1 was enhanced by either CsA (∼8-fold) or PK11195 (∼6-fold). In contrast, replication of the G89V mutant was not improved by either of the drugs at any virus dose tested (Fig. 4D). Therefore, the mutation and the drugs seemed to have redundant enhancing effects on virus replication.

The G89V mutation does not disrupt HIV-1 CA recognition by Lv1.

The previous results (Fig. 4A to D) suggested that, to some extent, G89V renders HIV-1 resistant to Lv1. We therefore expected that saturation of Lv1 by using VLPs would have a smaller enhancing effect on G89V HIV-1 than on the wild type. Indeed, as shown in Fig. 4E, replication of wild-type HIV-1 was enhanced about 50-fold by VLPs, while replication of G89V was enhanced only about 6-fold. That the replication of G89V HIV-1 could still be enhanced by VLPs suggested that G89V renders HIV-1 only partially resistant to Lv1 in FRhK4 cells.

G89V mutation-induced resistance to Lv1 could be due to a decreased affinity of HIV-1 CA to restriction factors present in FRhK4 cells. In that case, one would expect G89V VLPs to be less efficient at saturating Lv1 than wild-type VLPs. However, G89V VLPs were at least as efficient as their wild-type counterpart at increasing the replication of HIV-1 (Fig. 4E). This suggests that the affinity between G89V CA and the substrate recognition component of the restriction factor is comparable to that of the wild type. This is in sharp contrast with what was seen in OMK cells, where G89V VLPs did not enhance the replication of wild-type HIV-1 while an equivalent concentration of wild-type VLPs increased infectivity 100-fold (43).

The G89V mutation increases nuclear translocation of HIV-1 cDNA in rhesus macaque cells.

FRhK4 cells were infected with either wild-type or G89V HIV-1NL-GFP. Cells were lysed and submitted to Southern analysis (Fig. 5). At the same time, an aliquot of cells was maintained in culture for 2 days and analyzed for HIV-1 infectivity (Fig. 5A, bottom). G89V was fourfold more infectious than wild-type HIV-1NL-GFP (as expected from the data in Fig. 4), but the G89V mutation resulted in only a slight increase in the amount of total cDNA. In contrast, G89V increased the nuclear transport of viral cDNA, as seen by an increase in DNA circles and a decrease in linear DNA (Fig. 5). This same result was obtained after harvesting viral cDNA from three separate infections. Therefore, G89V has an effect on HIV-1 cDNA similar to that of CsA.

FIG. 5.

Effect of the G89V CA mutant on HIV-1 cDNA synthesis. FRhK4 cells were infected for 16 h with wild-type or G89V mutant HIV-1NL-GFP. The two viruses were normalized by p24 ELISA. (A) Cells were trypsinized, and total DNA was extracted and processed for Southern blotting as described in the legend for Fig. 2. Similar amounts of DNA were loaded in each lane, as demonstrated with a probe against mitochondrial DNA (data not shown). As a control, cells were infected with wild-type virus in the presence of 3TC. The main viral DNA species are identified on the left of the blot. One-twentieth of each culture was set aside to determine the percentage of cells expressing GFP, as indicated at the bottom of each lane. (B) Signals in each lane of panel A were quantitated by a phosphorimager as described in the legend for Fig. 2.

HIV-1 VLPs and PK11195 have redundant effects on HIV-1 replication in macaque cells.

As shown in Fig. 4E, a high dose of VLPs will overcome almost all of the Lv1 restriction to HIV-1 replication in FRhK4 cells. We asked whether HIV-1 replication was still stimulated by PK11195 or CsA under conditions where VLPs only partially overcome Lv1. In the experiment shown in Fig. 6A, wild-type and G89V HIV-1NL-GFP were normalized by p24 ELISA and used to infect FRhK4 cells in the presence of VLPs, PK11195, or CsA. In the absence of VLPs, PK11195 and CsA enhanced wild-type HIV-1 replication by 23- and 11-fold, respectively. As expected, both drugs had a much smaller effect on G89V (threefold for PK11195, no effect for CsA). Adding VLPs during infection increased wild-type replication by 20-fold. When VLPs were combined with PK11195, the drug did not enhance HIV-1 replication any further. In fact, we observed a small decrease compared to VLPs alone, perhaps revealing negative effects of PK11195 on replication normally masked by its effect on Lv1. A very different result was seen when VLPs and CsA were combined: CsA had a fourfold additional enhancing effect on replication compared to that with VLPs alone. Together, VLPs and CsA increased infection by ∼80-fold in FRhK4 cells, thus totally overcoming the restriction to HIV-1 replication. As expected, VLP treatment had a comparatively small effect on G89V replication (∼4-fold), and neither PK11195 nor CsA provided additional enhancement to G89V replication.

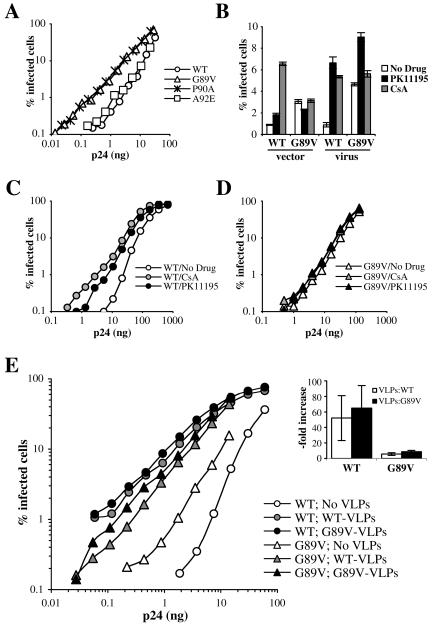

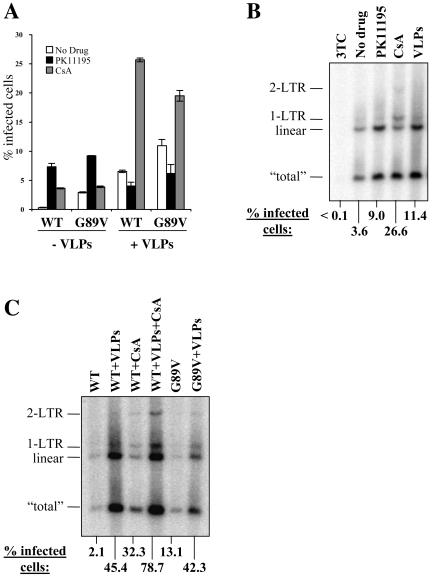

FIG. 6.

HIV-1 cDNA synthesis after infection of macaque cells is increased in the presence of VLPs. (A) Wild-type or G89V mutant HIV-1NL-GFP (normalized by p24 ELISA) were used to infect FRhK4 cells in the presence of wild-type HIV-1 VLPs, PK11195, or CsA as indicated. The percentage of cells expressing GFP was determined 2 days later by flow cytometry. (B) FRhK4 cells were infected for 16 h with VSV-G-pseudotyped HIV-1 in the presence of PK11195, CsA, VLPs, or 3TC, as indicated. Cells were processed for Southern blotting as described for Fig. 2. (C) FRhK4 cells were infected with wild-type or G89V HIV-1NL-GFP and treated with either VLPs or CsA (5 μM) or a combination of the two. HIV-1 cDNA was detected by Southern blotting as described above. The percentage of GFP-expressing cells was determined as above and is indicated at the bottom of the figure.

Since the effect of VLPs is redundant with that of PK11195, but not that of CsA, we postulated that VLPs would have the same effect as PK11195 on viral cDNA synthesis. We performed a Southern analysis of FRhK4 cells infected by HIV-1 in the presence of VLPs, CsA, or PK11195. An aliquot of the cells was maintained in culture for 2 days to monitor the percentage of infected cells. Under the conditions used, VLPs increased infectivity by threefold (Fig. 6B). CsA and PK11195 increased infectivity by 7- and 2.5-fold, respectively. As observed before, PK11195 resulted in a marked increase in the amount of linear, but not 1-LTR, viral cDNA (Fig. 6B). In contrast, CsA greatly stimulated the formation of the 1-LTR species. The effect of VLPs was remarkably similar to that of PK11195, with a large increase in the amount of linear cDNA but no effect on 1-LTR DNA. Therefore, under the conditions used, the effects of VLPs and PK11195 on viral cDNA synthesis were redundant, consistent with the infectivity results shown in Fig. 6A. PK11195 had no significant effect on cDNA synthesis by G89V (data not shown).

HIV-1 VLPs and CsA have additive effects on HIV-1 replication in macaque cells.

Since VLPs and CsA seemed to rescue HIV-1 replication in macaque cells by different mechanisms, we determined whether the effects of the two treatments would be additive. Treatment with VLPs (used at a dose 10 times higher than that in Fig. 6B) or CsA increased infectivity by 22- or 15-fold, respectively (Fig. 6C). A combination of both treatments increased HIV-1 replication by 37-fold. Even at such a high dose, the VLPs had no effect on the transport of HIV-1 cDNA to the nucleus, as judged by the amount of 1-LTR circular cDNA. In contrast, CsA increased the ratio of 1-LTR circles to linear cDNA but had only a moderate effect on total cDNA synthesis. A combination of the two treatments showed that the effects were additive, with an increase in total cDNA being synthesized, but also an increase in the relative amounts of the nuclear forms (both 1-LTR and 2-LTR). We also examined the effect of VLPs on cDNA synthesis by G89V. Consistent with the G89V mutation having a CsA-like effect on HIV-1 replication, G89V plus VLPs showed both enhanced total cDNA synthesis and enhanced nuclear transport of the cDNA (Fig. 6C).

Mitochondria-targeting drugs counteract both Ref1 and Lv1 in African green monkey cells.

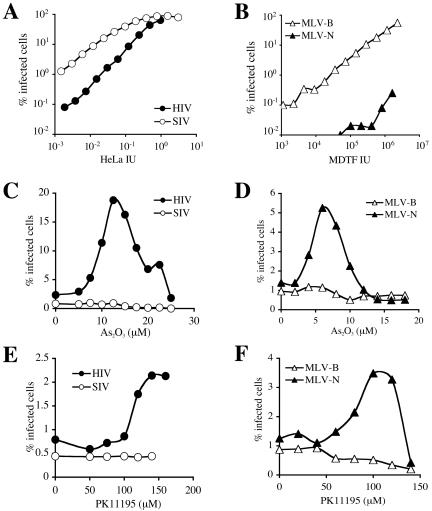

Our group previously found that As2O3 counteracts the effect of Ref1 on N-tropic MLV replication in human TE671 cells (6). PK11195, another drug that disrupts mitochondrial membrane potential, counteracts Lv1 in FRhK4 cells. We analyzed the effect of the two drugs on retroviral replication in African green monkey Vero cells, which are known to show both Ref1 and Lv1 activities (17, 42). To quantify Lv1 and Ref1 activities, we infected Vero cells at multiple viral doses using HIV-1NL-GFP, SIVMAC239-GFP, or the GFP-expressing MLV-derived vectors MLV-N and MLV-B. Viral stocks were normalized with respect to their titer on nonrestrictive cells: titers for HIV-1 and SIVMAC239 were determined on HeLa cells, and titers for MLV-N and MLV-B were determined on M. dunni fibroblasts. SIVMAC239 was roughly 20-fold more infectious than HIV-1 (Fig. 7A), and MLV-B was 200- to 500-fold more infectious than MLV-N (Fig. 7B). As2O3 enhanced HIV-1 replication, with a maximum enhancement of ∼8-fold at 12 μM, but it did not have any effect on SIVMAC239 (Fig. 7C). In addition, As2O3 enhanced the replication of MLV-N, with a maximum of ∼4-fold at 6 μM, but had no effect on MLV-B (Fig. 7D). Similarly, PK11195 enhanced the replication of HIV-1, but not SIVMAC239, in Vero cells (Fig. 7E). Finally, PK11195 increased the replication of MLV-N roughly threefold but had no stimulatory effect on MLV-B (Fig. 7F). Therefore, both As2O3 and PK11195 counteracted Ref1 and Lv1 in Vero cells. In these cells, As2O3 had a greater effect than PK11195 against both restriction activities.

FIG. 7.

As2O3 and PK11195 counteract Ref1 and Lv1 activity in African green monkey cells. (A) HIV-1NL-GFP and SIVMAC239-GFP were used to infect Vero cells with multiple doses of virus. The two virus stocks were normalized by determining infectious units on HeLa cells. (B) B-tropic and N-tropic GFP-expressing MLV vectors were used to infect Vero cells. Virus doses are expressed as infectious units on nonrestrictive MDTF cells. Vero cells were infected with HIV-1NL-GFP and SIVMAC239-GFP (C and E) or MLV-N and MLV-B (D and F) in the presence of the indicated concentrations of As2O3 (C and D) or PK11195 (E and F). In all cases, the percentage of cells expressing GFP at 48 h postinfection was determined by flow cytometry.

The CA G89V mutation renders HIV-1 partly resistant to Lv1 in African green monkey cells.

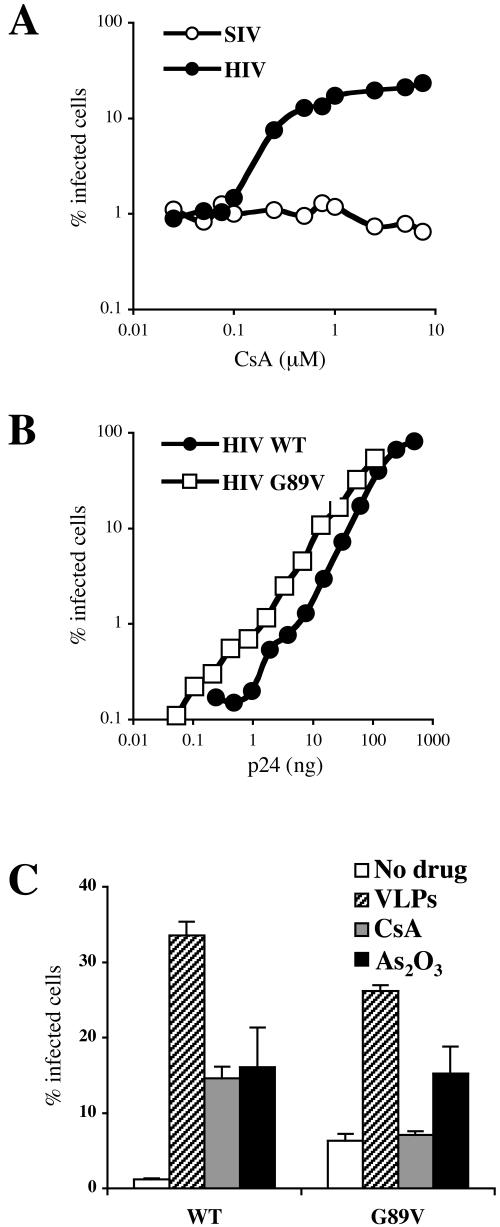

CsA and the CA G89V mutation both counteract Lv1 activity in OMK cells (43). In Vero cells, CsA was found to increase the infectivity of HIV-1, but not SIVMAC239, at concentrations higher than 0.1 μM, and the magnitude of this effect was roughly 10-fold at concentrations higher than 0.5 μM (Fig. 8A). HIV-1 bearing the G89V mutation was two- to threefold more infectious in Vero cells than the wild type over a range of MOIs (Fig. 8B). Therefore, as is the case in FRhK4 cells, the G89V mutation improved viral infectivity but did not enhance it to the level of the unrestricted control virus SIVMAC239-GFP.

FIG. 8.

Effect of CsA or the HIV-1 CA G89V mutation on Lv1 activity in African green monkey cells. (A) HIV-1NL-GFP and SIVMAC239-GFP were used to infect Vero cells in the presence of the indicated concentrations of CsA. (B and C) Wild-type and G89V mutant HIV-1NL-GFP (normalized by ELISA for p24) were used to infect Vero cells at multiple virus doses (B) or at a single dose in the presence of HIV-1 VLPs, PK11195, or CsA (C). In each case, the percentage of cells expressing GFP was determined 2 days postinfection by flow cytometry.

Wild-type and G89V HIV-1 were then normalized by p24 ELISA and used to infect Vero cells in the presence of VLPs, CsA (2.5 μM), or As2O3 (12.5 μM). G89V was again found to be more infectious than the wild type (Fig. 8C). CsA and As2O3 both enhanced infection with the wild-type virus by roughly 12-fold, and VLP treatment increased infection with the wild type by roughly 30-fold, thus abolishing Lv1 activity in these cells (Fig. 8C). As was the case in FRhK4 cells, CsA and As2O3 had little or no effect on G89V replication. VLPs still enhanced G89V infection by roughly fourfold, and G89V in the presence of VLPs was almost as infectious as wild-type HIV-1 in the presence of VLPs. These results in Vero cells closely resembled those obtained in FRhK4 cells and confirmed the relevance of the CypA-binding region of CA to Lv1 activity in different monkey species.

DISCUSSION

Effect of mitochondria-targeting drugs on Lv1.

We have shown here that PK11195 and m-Cl-CCP partly suppress Lv1 activity in macaque FRhK4 cells. In addition, As2O3 and PK11195 also counteract both Lv1 and Ref1 in African green monkey Vero cells. As2O3 has been reported to disrupt promyelocytic leukemia bodies (25), to trigger apoptosis through permeabilization of the mitochondrial membrane (24, 27), and to negatively regulate the NF-κB pathway via direct binding to the IκB kinase (21). Though some have found that As2O3 stimulates HIV-1 replication via effects on promyelocytic leukemia bodies (44), we and others have failed to obtain evidence for the importance of As2O3 effects on these structures (4, 6). Sulindac and thalidomide, two drugs that interfere with NF-κB signaling (22), had no effect on HIV-1 replication in Vero cells (data not shown), suggesting that the HIV-1 stimulatory effects of As2O3 did not involve effects on this pathway. The fact that we observed effects with two other drugs that disrupt mitochondrial membrane potential, PK11195 and m-Cl-CCP, suggests that the effects of As2O3 on mitochondria are relevant to the stimulation of HIV-1.

Unlike As2O3, the molecular target of PK11195 is well defined and the binding is highly specific. For instance, radiolabeled PK11195 has been used in imaging of mitochondrial benzodiazepine receptor-rich cells by positron emission tomography scanning (47). PK11195 in FRhK4 cells increased the amount of HIV-1 cDNA being synthesized, but it had no apparent effect on its transport to the nucleus. As2O3 similarly increased HIV-1 cDNA synthesis in human cells (6). Our data suggest that effects of these drugs on mitochondria somehow modulate the activity of retroviral restriction factors. Immuno-fluorescence microscopy of FRhK4 cells after HIV-1 infection showed no colocalization of HIV-1 CA with mitochondria (data not shown), though others have reported an accumulation of HIV-1 RNA in mitochondria (39). Perhaps the mitochondrial drugs used here act by shutting off a source of ATP necessary for the restriction activity, though we saw no effect of the drugs on cytoplasmic nucleotide pools (6). Many factors are released from the mitochondrial intermembrane space upon the action of these proapoptotic drugs (3, 19, 24, 27, 37, 40), and the effects of the drugs on viral replication might involve some of these factors.

Lv1 inhibits more than one step of HIV-1 replication.

Recent work has shown that in many monkey cells, including macaque cells, Lv1 results in less HIV-1 cDNA being made (7, 14, 33). Analysis of viral cDNA from acutely infected FRhK4 cells indeed pointed to a synthesis defect. This was suggested by the fact that treatment with VLPs increased the amount of HIV-1 cDNA being synthesized, and so did treatment with the drug PK11195 and, to a lesser degree, CsA (Fig. 2, 4, and 6). In addition, we found evidence that in FRhK4 cells, Lv1 affects the transport of viral cDNA to the nucleus and that this block is specifically overcome by CsA or a mutation in CA which disrupts interaction with CypA (Fig. 2, 5, and 6). Therefore, it appears that Lv1 in rhesus macaque cells not only inhibits HIV-1 cDNA synthesis but perhaps also blocks nuclear translocation of the DNA. This is reminiscent of the inhibition of MLV by Fv1, which has been reported to affect cDNA accumulation and/or transport to the nucleus (16, 36).

Improving either cDNA synthesis or its transport to the nucleus counteracts Lv1.

The effect of CsA was consistently found to be redundant with that of the G89V mutation but not with that of VLP treatment (Fig. 4, 6, and 8). Therefore, it is likely that in FRhK4 cells CsA prevents the same anti-HIV-1 restriction step also countered by the G89V mutation. The effect of PK11195 on HIV-1 replication in FRhK4 cells, in contrast, appeared to be redundant with that of VLPs, as seen in infection assays and also on viral cDNA profiles (Fig. 6). We could not directly determine if the effects of CsA and PK11195 were additive, as this drug combination was highly toxic to cells (data not shown). However, two other findings indicated that PK11195 and CsA enhanced HIV-1 replication by different mechanisms. First, CsA had the same magnitude effect on HIV-1 vectors and on full-length viruses, while PK11195 did not enhance the replication of vectors (Fig. 4B). Second, all mitochondria-targeting drugs stimulated retroviral replication at toxic concentrations on all cell lines examined, while CsA counteracted Lv1 at nontoxic concentrations. The effects of PK11195 treatment and the G89V mutation on HIV-1 replication in FRhK4 and Vero cells were also partly redundant (Fig. 4, 6, and 8).

The CypA-binding region in CA confers sensitivity to Lv1 in multiple monkey cell lines.

Our data show that mutations in the CypA-binding region of CA (11, 29, 30) increase HIV-1 replication in FRhK4 and also in Vero cells. The G89V mutation confers a roughly 5-fold increase of infectivity in FRhK4 cells, far from the ∼100-fold enhancement that would be expected for a mutation totally inhibiting the effect of Lv1 in these cells. In fact, VLPs, CsA, or PK11195 often mediated a greater enhancement of HIV-1 replication than the G89V mutation did. However, the idea that the CA G89V mutation indeed counteracted Lv1 in these cells was supported by the fact that G89V virus infection was less sensitive to the effects of CsA, PK11195, and VLP treatment. How the interaction between HIV-1 and CypA in human cells relates to restriction of HIV-1 replication in monkey cells remains unclear. It is possible that a component of Lv1 contains CypA-like domains that could be targeted by CsA. In addition, Ref1 is not sensitive to CsA in Vero cells (data not shown), while Lv1 activity was partly inhibited by this drug, implying differences in the nature and/or regulation of these two restrictions.

Surprisingly, we found that G89V VLPs saturate Lv1 activity as efficiently as wild-type VLPs (Fig. 4E). This result suggests that the determinants for CA recognition by restriction factors and sensitivity to restriction activity are independent, as reported by others (34). It also points out subtle differences that distinguish Lv1 activities from different species. G89V completely rescues HIV-1 from Lv1 restriction in owl monkey OMK cells (43). That the G89V mutation prevents recognition of HIV-1 CA by Lv1 in OMK cells but not in FRhK4 cells may explain why the mutation only partially rescues HIV-1 replication in the macaque cells.

Lv1-resistant HIV-1 in a rhesus macaque AIDS model.

Some SIV strains cause AIDS in rhesus macaques, but these monkeys cannot be infected by HIV-1, at least partly because of Lv1 activity. It is possible that G89V or P90A, two mutations that partly rescued HIV-1 replication in FRhK4 cells (Fig. 4), would permit HIV-1 propagation in macaque lymphocytes. Even a low level of replication might be sufficient to passage HIV-1 and attempt to isolate variants with greater infectivity. This strategy might make it possible to generate an HIV-1 strain able to infect rhesus macaques and to subsequently cause AIDS in these animals.

Acknowledgments

We thank Paul Bieniasz, Dana Gabuzda, Vincent Racaniello, and Greg Towers for providing reagents.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant RO1AI36199 to J.L. and the Columbia Rockefeller Center for AIDS Research. L.B. was an Elizabeth Glaser Pediatric AIDS Foundation Scholar.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aberham, C., S. Weber, and W. Phares. 1996. Spontaneous mutations in the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gag gene that affect viral replication in the presence of cyclosporins. J. Virol. 70:3536-3544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adachi, A., H. E. Gendelman, S. Koenig, T. Folks, R. Willey, A. Rabson, and M. A. Martin. 1986. Production of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome-associated retrovirus in human and nonhuman cells transfected with an infectious molecular clone. J. Virol. 59:284-291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Armstrong, J. S., K. K. Steinauer, J. French, P. L. Killoran, J. Walleczek, J. Kochanski, and S. J. Knox. 2001. Bcl-2 inhibits apoptosis induced by mitochondrial uncoupling but does not prevent mitochondrial transmembrane depolarization. Exp. Cell Res. 262:170-179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bell, P., L. J. Montaner, and G. G. Maul. 2001. Accumulation and intranuclear distribution of unintegrated human immunodeficiency virus type 1 DNA. J. Virol. 75:7683-7691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berthoux, L., C. Pechoux, and J. L. Darlix. 1999. Multiple effects of an anti-human immunodeficiency virus nucleocapsid inhibitor on virus morphology and replication. J. Virol. 73:10000-10009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berthoux, L., G. J. Towers, C. Gurer, P. Salomoni, P. P. Pandolfi, and J. Luban. 2003. As2O3 enhances retroviral reverse transcription and counteracts Ref1 antiviral activity. J. Virol. 77:3167-3180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Besnier, C., Y. Takeuchi, and G. Towers. 2002. Restriction of lentivirus in monkeys. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:11920-11925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Best, S., P. Le Tissier, G. Towers, and J. P. Stoye. 1996. Positional cloning of the mouse retrovirus restriction gene Fv1. Nature 382:826-829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bieniasz, P. D., and B. R. Cullen. 2000. Multiple blocks to human immunodeficiency virus type 1 replication in rodent cells. J. Virol. 74:9868-9877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bouyac-Bertoia, M., J. D. Dvorin, R. A. Fouchier, Y. Jenkins, B. E. Meyer, L. I. Wu, M. Emerman, and M. H. Malim. 2001. HIV-1 infection requires a functional integrase NLS. Mol. Cell 7:1025-1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Braaten, D., C. Aberham, E. K. Franke, L. Yin, W. Phares, and J. Luban. 1996. Cyclosporine A-resistant human immunodeficiency virus type 1 mutants demonstrate that Gag encodes the functional target of cyclophilin A. J. Virol. 70:5170-5176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Braaten, D., and J. Luban. 2001. Cyclophilin A regulates HIV-1 infectivity, as demonstrated by gene targeting in human T cells. EMBO J. 20:1300-1309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chelli, B., A. Falleni, F. Salvetti, V. Gremigni, A. Lucacchini, and C. Martini. 2001. Peripheral-type benzodiazepine receptor ligands: mitochondrial permeability transition induction in rat cardiac tissue. Biochem. Pharmacol. 61:695-705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cowan, S., T. Hatziioannou, T. Cunningham, M. A. Muesing, H. G. Gottlinger, and P. D. Bieniasz. 2002. Cellular inhibitors with Fv1-like activity restrict human and simian immunodeficiency virus tropism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:11914-11919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dvorin, J. D., P. Bell, G. G. Maul, M. Yamashita, M. Emerman, and M. H. Malim. 2002. Reassessment of the roles of integrase and the central DNA flap in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 nuclear import. J. Virol. 76:12087-12096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goff, S. P. 1996. Operating under a Gag order: a block against incoming virus by the Fv1 gene. Cell 86:691-693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hatziioannou, T., S. Cowan, S. P. Goff, P. D. Bieniasz, and G. J. Towers. 2003. Restriction of multiple divergent retroviruses by Lv1 and Ref1. EMBO J. 22:385-394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.He, J., Y. Chen, M. Farzan, H. Choe, A. Ohagen, S. Gartner, J. Busciglio, X. Yang, W. Hofmann, W. Newman, C. R. Mackay, J. Sodroski, and D. Gabuzda. 1997. CCR3 and CCR5 are co-receptors for HIV-1 infection of microglia. Nature 385:645-649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hirsch, T., D. Decaudin, S. A. Susin, P. Marchetti, N. Larochette, M. Resche-Rigon, and G. Kroemer. 1998. PK11195, a ligand of the mitochondrial benzodiazepine receptor, facilitates the induction of apoptosis and reverses Bcl-2-mediated cytoprotection. Exp. Cell Res. 241:426-434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hofmann, W., D. Schubert, J. LaBonte, L. Munson, S. Gibson, J. Scammell, P. Ferrigno, and J. Sodroski. 1999. Species-specific, postentry barriers to primate immunodeficiency virus infection. J. Virol. 73:10020-10028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kapahi, P., T. Takahashi, G. Natoli, S. R. Adams, Y. Chen, R. Y. Tsien, and M. Karin. 2000. Inhibition of NF-κB activation by arsenite through reaction with a critical cysteine in the activation loop of IκB kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 275:36062-36066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Karin, M., Y. Yamamoto, and Q. M. Wang. 2004. The IKK NF-kappa B system: a treasure trove for drug development. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 3:17-26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kootstra, N. A., C. Munk, N. Tonnu, N. R. Landau, and I. M. Verma. 2003. Abrogation of postentry restriction of HIV-1-based lentiviral vector transduction in simian cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100:1298-1303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kroemer, G., and H. de The. 1999. Arsenic trioxide, a novel mitochondriotoxic anticancer agent? J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 91:743-745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lallemand-Breitenbach, V., J. Zhu, F. Puvion, M. Koken, N. Honore, A. Doubeikovsky, E. Duprez, P. P. Pandolfi, E. Puvion, P. Freemont, and H. de The. 2001. Role of promyelocytic leukemia (PML) sumolation in nuclear body formation, 11S proteasome recruitment, and As2O3-induced PML or PML/retinoic acid receptor alpha degradation. J. Exp. Med. 193:1361-1371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Landau, N. R., M. Warton, and D. R. Littman. 1988. The envelope glycoprotein of the human immunodeficiency virus binds to the immunoglobulin-like domain of CD4. Nature 334:159-162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Larochette, N., D. Decaudin, E. Jacotot, C. Brenner, I. Marzo, S. A. Susin, N. Zamzami, Z. Xie, J. Reed, and G. Kroemer. 1999. Arsenite induces apoptosis via a direct effect on the mitochondrial permeability transition pore. Exp. Cell Res. 249:413-421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li, L., J. M. Olvera, K. E. Yoder, R. S. Mitchell, S. L. Butler, M. Lieber, S. L. Martin, and F. D. Bushman. 2001. Role of the non-homologous DNA end joining pathway in the early steps of retroviral infection. EMBO J. 20:3272-3281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Luban, J. 1996. Absconding with the chaperone: essential cyclophilin-Gag interaction in HIV-1 virions. Cell 87:1157-1159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Luban, J., K. L. Bossolt, E. K. Franke, G. V. Kalpana, and S. P. Goff. 1993. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Gag protein binds to cyclophilins A and B. Cell 73:1067-1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mariani, R., B. A. Rasala, G. Rutter, K. Wiegers, S. M. Brandt, H. G. Krausslich, and N. R. Landau. 2001. Mouse-human heterokaryons support efficient human immunodeficiency virus type 1 assembly. J. Virol. 75:3141-3151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mariani, R., G. Rutter, M. E. Harris, T. J. Hope, H. G. Krausslich, and N. R. Landau. 2000. A block to human immunodeficiency virus type 1 assembly in murine cells. J. Virol. 74:3859-3870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Munk, C., S. M. Brandt, G. Lucero, and N. R. Landau. 2002. A dominant block to HIV-1 replication at reverse transcription in simian cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:13843-13848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Owens, C. M., B. Song, M. J. Perron, P. C. Yang, M. Stremlau, and J. Sodroski. 2004. Binding and susceptibility to postentry restriction factors in monkey cells are specified by distinct regions of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 capsid. J. Virol. 78:5423-5437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Owens, C. M., P. C. Yang, H. Gottlinger, and J. Sodroski. 2003. Human and simian immunodeficiency virus capsid proteins are major viral determinants of early, postentry replication blocks in simian cells. J. Virol. 77:726-731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pryciak, P. M., and H. E. Varmus. 1992. Fv-1 restriction and its effects on murine leukemia virus integration in vivo and in vitro. J. Virol. 66:5959-5966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ravagnan, L., T. Roumier, and G. Kroemer. 2002. Mitochondria, the killer organelles and their weapons. J. Cell Physiol. 192:131-137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Simizu, B., J. S. Rhim, and N. H. Wiebenga. 1967. Characterization of the Tacaribe group of arboviruses. I. Propagation and plaque assay of Tacaribe virus in a line of African green monkey kidney cells (Vero). Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 125:119-123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Somasundaran, M., M. L. Zapp, L. K. Beattie, L. Pang, K. S. Byron, G. J. Bassell, J. L. Sullivan, and R. H. Singer. 1994. Localization of HIV RNA in mitochondria of infected cells: potential role in cytopathogenicity. J. Cell Biol. 126:1353-1360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sordet, O., C. Rebe, I. Leroy, J. M. Bruey, C. Garrido, C. Miguet, G. Lizard, S. Plenchette, L. Corcos, and E. Solary. 2001. Mitochondria-targeting drugs arsenic trioxide and lonidamine bypass the resistance of TPA-differentiated leukemic cells to apoptosis. Blood 97:3931-3940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stoye, J. P. 2002. An intracellular block to primate lentivirus replication. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:11549-11551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Towers, G., M. Bock, S. Martin, Y. Takeuchi, J. P. Stoye, and O. Danos. 2000. A conserved mechanism of retrovirus restriction in mammals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:12295-12299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Towers, G. J., T. Hatziioannou, S. Cowan, S. P. Goff, J. Luban, and P. D. Bieniasz. 2003. Cyclophilin A modulates the sensitivity of HIV-1 to host restriction factors. Nat. Med. 9:1138-1143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Turelli, P., V. Doucas, E. Craig, B. Mangeat, N. Klages, R. Evans, G. Kalpana, and D. Trono. 2001. Cytoplasmic recruitment of INI1 and PML on incoming HIV preintegration complexes: interference with early steps of viral replication. Mol. Cell 7:1245-1254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wallace, R. E., P. J. Vasington, J. C. Petricciani, H. E. Hopps, D. E. Lorenz, and Z. Kadanka. 1973. Development and characterization of cell lines from subhuman primates. In Vitro 8:333-341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wei, P., M. E. Garber, S. M. Fang, W. H. Fischer, and K. A. Jones. 1998. A novel CDK9-associated C-type cyclin interacts directly with HIV-1 Tat and mediates its high-affinity, loop-specific binding to TAR RNA. Cell 92:451-462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Weissman, B. A., and L. Raveh. 2003. Peripheral benzodiazepine receptors: on mice and human brain imaging. J. Neurochem. 84:432-437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yin, L., D. Braaten, and J. Luban. 1998. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 replication is modulated by host cyclophilin A expression levels. J. Virol. 72:6430-6436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zennou, V., C. Petit, D. Guetard, U. Nerhbass, L. Montagnier, and P. Charneau. 2000. HIV-1 genome nuclear import is mediated by a central DNA flap. Cell 101:173-185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zufferey, R., D. Nagy, R. J. Mandel, L. Naldini, and D. Trono. 1997. Multiply attenuated lentiviral vector achieves efficient gene delivery in vivo. Nat. Biotechnol. 15:871-875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]