Abstract

Binding of the BZLF1 viral transactivator to Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) oriLyt has been reported to be essential for viral DNA replication. We have constructed a recombinant virus (E2-oriLyt-R) in which the oriLyt BZLF1-binding sites (ZRE) were exchanged against papilloma E2-binding sites. A fusion protein between the BZLF1 protein-transactivating domain and the E2 protein-binding domain was able to reactivate lytic replication in E2-oriLyt-R. However, BZLF1 alone could also induce E2-oriLyt-R, albeit with much lower efficiency. ZRE are therefore important but not absolutely essential cis elements for lytic replication. This shows the importance of recombinants to evaluate viral functions.

Lytic replication of herpesviruses is a multistep biological process that leads to the production of infectious particles (6). It involves proteins of both viral and cellular origin that bind and interact with several viral cis elements including two copies of the lytic origin of DNA replication, oriLyt. However, the viral genome contains redundant sequences as exemplified by Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) deletion mutants that carry only one oriLyt copy (e.g., the B95.8 laboratory isolate) and are still fully functional. Several cellular and viral proteins have been shown to bind to different subdomains of oriLyt (1, 5). One of the viral proteins is the EBV transactivator BZLF1 that has several functions during lytic replication. One function is to bind to the seven binding sites for BZLF1 (BZLF1 responsive elements [ZRE]) that are located within oriLyt. EBV reporter plasmids in which all seven ZRE sites were exchanged against binding sites for the papilloma virus transactivator E2 completely lose their ability to be replicated, whereas a fusion protein consisting of the papilloma virus E2 DNA-binding domain and of the BZLF1 transactivation domain could still induce lytic replication (8). By bringing the transactivation domain of BZLF1 close to the origin of replication, the ZRE contained in oriLyt are therefore thought to be essential for lytic replication (8). Because these results were obtained from an isolated origin of replication cloned onto a reporter plasmid, we wished to reexamine the function of the BZLF1-binding sites in oriLyt in the context of a recombinant EBV genome. To this aim, we have constructed a recombinant virus carrying a modified oriLyt in which ZRE were exchanged against E2-binding sites.

Construction of the E2-oriLyt-R EBV mutant.

We first introduced the construct p1199.2 initially designed by Schepers et al. (7) containing the modified oriLyt into an EBV recombinant virus using homologous recombination in Escherichia coli cells as previously described (Fig. 1) (3). This recombinant virus consists of wild-type EBV genome cloned onto an F plasmid which carries the gene for the green fluorescent protein (GFP) and the hygromycin resistance gene. The mutant oriLyt EBV construct, designated E2-oriLyt-R, was then stably transfected using lipid micelles (Lipofectamine; Invitrogen) into the 293 cell line, and cells carrying the recombinant were selected for hygromycin resistance (E2-oriLyt-R 293 cells). The circular EBV DNA was extracted from hygromycin-resistant 293 cells (4), and restriction fragment analysis confirmed the integrity of the recombinant EBV DNA (Fig. 2). 293 cell clones carrying the recombinant EBV were then tested for their ability to produce virions by cotransfecting them with BZLF1 and a chimeric protein containing the E2-binding domain (amino acids 128 to 410) and the BZLF1 transactivation domain (amino acids 1 to 169) (E2-BZLF1). Supernatants from different clones were harvested 3 days after induction with BZLF1 and E2-BZLF1 and incubated with Raji Burkitt's lymphoma cells for another 3 days. E2-oriLyt-R carries the gfp gene and infected Raji cells show bright green fluorescence. Supernatant from one of these clones resulted in 12% of Raji cells being GFP positive and was selected for further experiments. Cotransfection of BZLF1 and E2-BZLF1 fusion protein therefore complemented the defective phenotype induced by the exchange of ZRE against E2-binding sites in oriLyt. This shows that no additional unwanted mutations were introduced during construction of the viral recombinant and that variation between the wild type and E2-oriLyt-R was limited to the ZRE sites. We then assessed the function of the ZRE-binding sites by testing the ability of BZLF1 to induce the lytic cycle in E2-oriLyt-R 293 cells in the absence of E2-BZLF1. In this experiment, BZLF1 will not bind to the ZRE in oriLyt but will perform its remaining contributions to EBV lytic replication. E2-oriLyt-R 293 cells cotransfected with BZLF1 and the E2-BZLF1 fusion protein provided the appropriate positive control for the experiment. Viral titers in both samples were evaluated by infecting Raji cells with the supernatants. We found 0.09% GFP-positive cells after transfection of BZLF1 alone, compared with 11.3% GFP-positive cells after cotransfection of BZLF1 and E2-BZLF1 and 0% after incubation of the cells with supernatants from uninduced E2-oriLyt-R 293 cells. Therefore, the presence of E2-BZLF1 increased viral titers 125-fold. Transfection of BZLF1 alone nevertheless led to the production of infectious viruses in E2-oriLyt-R 293 cells.

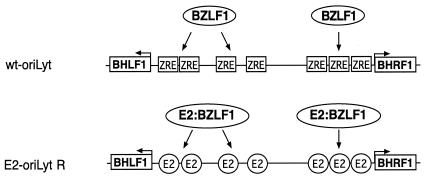

FIG. 1.

Schematic representation of the wild-type (wt) EBV lytic origin of DNA replication (top) and of the targeting vector used for construction of the E2-oriLyt recombinant (bottom). Seven binding sites for the EBV transactivator BZLF1 (ZRE 1 to 7) are located between the flanking genes BHLF1 and BHRF1 within oriLyt. All ZRE sites were replaced by E2-binding sites as described previously (7). Only an E2:BZLF1 chimeric protein will bind to the mutated E2-oriLyt.

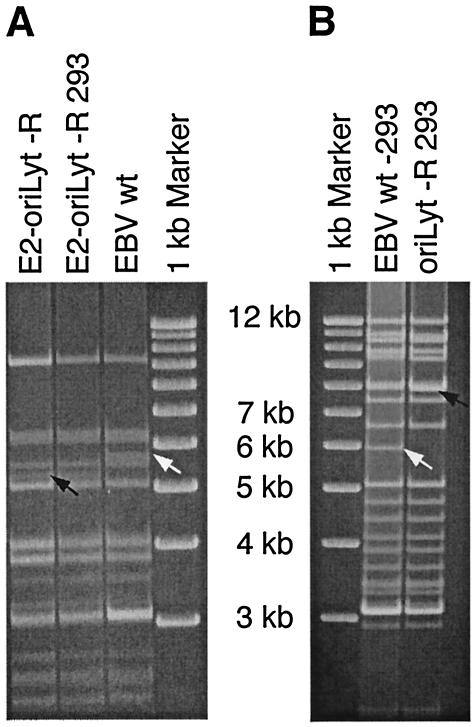

FIG. 2.

Restriction fragment analysis. (A) Plasmid DNA was extracted from bacterial cells containing the E2-oriLyt recombinant (E2-oriLyt-R) or the wild-type (wt) EBV genome. Circular EBV plasmid DNA from hygromycin-resistant 293 cells stably carrying E2-oriLyt-R was extracted and transformed into E. coli DH10B cells, and plasmid DNA was purified. All DNAs were digested with MscI, separated on a 0.8% agarose gel, and stained with ethidium bromide. Arrows indicate DNA fragments modified as the result of homologous recombination (5.7 kb for wild type and 5.3 kb for E2-oriLyt-R mutant). Restriction analysis shows that the E2-oriLyt-R 293 cells carry an intact E2-oriLyt-R mutant. (B) Circular EBV plasmid DNA from hygromycin-resistant 293 cells stably carrying oriLyt-KO or wild-type EBV was extracted as described above. Purified DNAs were digested with BamHI, submitted to electrophoresis, and stained with ethidium bromide. DNA fragments modified by homologous recombination events are indicated by arrows (6 kb for wild type and 7.9 kb for oriLyt-KO mutant).

Generation of lymphoblastoid cell lines with E2-oriLyt-R EBV mutant.

To confirm these observations, supernatants from E2-oriLyt-R 293 cells transfected with BZLF1 alone or in combination with E2-BZLF1 were used to infect primary B lymphocytes from peripheral blood. B cells were purified from buffy coats using a CD19 antibody conjugated to magnetic beads (Dynal Biotech, Bromborough, United Kingdom). B cells (105) were incubated with various dilutions of infectious supernatants (up to 1/50) and then plated at a density of 103 cells per well on a fibroblast feeder layer in 96-well cluster plates. To exclude contamination with endogenous lymphoblastoid cell lines (LCL), uninfected B cells were kept in culture in parallel. Three to 6 weeks after infection, lymphoblastoid cell lines from both infected cell populations grew out, confirming that ZRE-binding sites were not absolutely essential for virus production. In contrast, uninfected B cells showed no spontaneous outgrowth. Complemented supernatants used at a dilution of 1 in 50 gave rise to immortalized B-cell clones in 72% of the wells, compared to 28% with undiluted supernatants from E2-oriLyt-R 293 cells transfected with BZLF1 alone. Therefore, viral titers were 120 times higher after cotransfection of BZLF1 and E2-BZLF1 into E2-oriLyt-R 293 cells than after transfection of BZLF1 alone. Genomic DNA was extracted from some of these LCL and submitted to Southern blot analysis using a probe specific for the EBV terminal repeats (Fig. 3). In LCL obtained by incubation of the B cells with supernatants from E2-oriLyt-R 293 cells cotransfected with BZLF1 and E2-BZLF1, several bands were visible, whereas only one band was visible in LCL obtained with BZLF1 alone (Fig. 3). This suggests that the immortalized B-cell clones obtained from complemented supernatants were polyclonal in origin and resulted from infection of several primary B cells. This confirms that complemented supernatants had higher titers than supernatants obtained by transfecting BZLF1 in E2-oriLyt-R 293 cells alone. Finally, a Southern blot using an oriLyt-specific probe was performed to demonstrate that both LCL indeed carried the E2-oriLyt-R mutant but no wild-type viral isolate (Fig. 4).

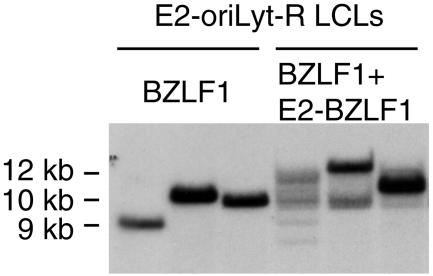

FIG. 3.

Southern blot analysis of lymphoblastoid B-cell clones that were established with supernatants obtained by transfection of E2-oriLyt-R 293 cells with BZLF1 or BZLF1 and E2-BZLF1. Ten micrograms of total DNA from each of these cells was digested with BamHI, and the blot was hybridized with the EBV terminal repeat probe. LCL generated by infection with viruses produced after transfection of E2-oriLyt-R with BZLF1 show a single terminal repeat band, contrasting with the multiple terminal repeat-specific signals in LCL generated with viruses produced after transfection with BZLF1 and E2-BZLF1.

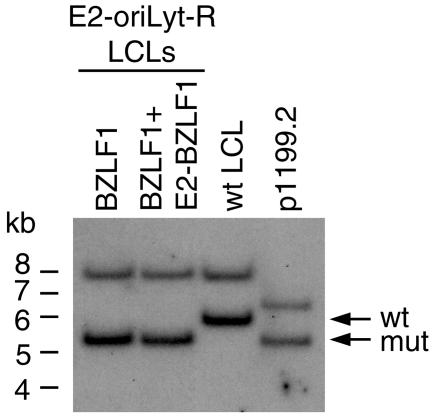

FIG. 4.

Southern blot analysis using an oriLyt-specific probe confirmed the presence of the recombinant E2-oriLyt-R genome in lymphoblastoid B-cell clones infected with the E2-oriLyt recombinant (lanes 1 and 2). The size of the BamHI fragment that encompasses the oriLyt locus is higher in the wild type than in E2-oriLyt-R and allows distinction between both types of viruses. Genomic DNA was cleaved with BamHI and separated on a 0.8% agarose gel. Five hundred picograms of plasmid p1199.2 containing the targeting vector used to construct the recombinant oriLyt and DNA from a LCL carrying wild-type EBV were loaded as controls. The 5.4-kb signal corresponds to the mutated oriLyt fragment. The 8-kb BamHI fragment also recognized by the oriLyt probe is common to both wild-type EBV and E2-oriLyt-R mutant.

EBV does not contain cryptic lytic replication sites.

One potential explanation for the results thus obtained is that EBV contains cryptic replication origins that could account for the residual lytic activity in E2-oriLyt-R 293 cells transfected with BZLF1 alone. We therefore constructed an EBV insertion mutant (oriLyt-KO) in which oriLyt was inactivated by separating its upstream and downstream elements at EBV coordinate 53237 with a 2.8-kb tetracycline resistance cassette (2) (Fig. 2B). Upon BZLF1 transfection in 293 cells carrying this mutant, expression of the BMRF1 early antigen could be clearly detected. However, incubation of Raji cells with supernatants from induced oriLyt-KO cells failed to reveal the presence of infectious particles (data not shown). This demonstrates that EBV does not contain cryptic lytic replication sites.

In summary, our results show that the oriLyt ZRE sites are not essential for EBV lytic replication but markedly amplify its efficiency when present. In principle, viruses devoid of oriLyt ZRE sites can be propagated with lower efficiency. Importantly, this work shows that experiments performed on viral cis elements cloned onto a plasmid can provide important information but that a more precise evaluation of the function of these elements requests an analysis in the context of the whole virus.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to A. Schepers and W. Hammerschmidt for providing the p1199.2 plasmid.

This work was supported by institutional funds.

REFERENCES

- 1.Baumann, M., R. Feederle, E. Kremmer, and W. Hammerschmidt. 1999. Cellular transcription factors recruit viral replication proteins to activate the Epstein-Barr virus origin of lytic DNA replication, oriLyt. EMBO J. 18:6095-6105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cherepanov, P. P., and W. Wackernagel. 1995. Gene disruption in Escherichia coli: TcR and KmR cassettes with the option of Flp-catalyzed excision of the antibiotic-resistance determinant. Gene 158:9-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Delecluse, H. J., T. Hilsendegen, D. Pich, R. Zeidler, and W. Hammerschmidt. 1998. Propagation and recovery of intact, infectious Epstein-Barr virus from prokaryotic to human cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:8245-8250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Griffin, B. E., E. Bjorck, G. Bjursell, and T. Lindahl. 1981. Sequence complexity of circular Epstein-Bar virus DNA in transformed cells. J. Virol. 40:11-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gruffat, H., O. Renner, D. Pich, and W. Hammerschmidt. 1995. Cellular proteins bind to the downstream component of the lytic origin of DNA replication of Epstein-Barr virus. J. Virol. 69:1878-1886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kieff, E., and A. B. Rickinson. 2001. Epstein-Barr virus and its replication, p. 2511-2628. In D. M. Knipe and P. M. Howley (ed.), Fields virology, 4th ed. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, Pa.

- 7.Schepers, A., D. Pich, and W. Hammerschmidt. 1996. Activation of oriLyt, the lytic origin of DNA replication of Epstein-Barr virus, by BZLF1. Virology 220:367-376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schepers, A., D. Pich, J. Mankertz, and W. Hammerschmidt. 1993. cis-acting elements in the lytic origin of DNA replication of Epstein-Barr virus. J. Virol. 67:4237-4245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]