Abstract

The narrow host range of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) is due in part to dominant acting restriction factors in humans (Ref1) and monkeys (Lv1). Here we show that gag encodes determinants of species-specific lentiviral infection, related in part to such restriction factors. Interaction between capsid and host cyclophilin A (CypA) protects HIV-1 from restriction in human cells but is essential for maximal restriction in simian cells. We show that sequence variation between HIV-1 isolates leads to variation in sensitivity to restriction factors in human and simian cells. We present further evidence for the importance of target cell CypA over CypA packaged in virions, specifically in the context of gp160 pseudotyped HIV-1 vectors. We also show that sensitivity to restriction is controlled by an H87Q mutation in the capsid, implicated in the immune control of HIV-1, possibly linking immune and innate control of HIV-1 infection.

Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) is a zoonosis from chimpanzees infected with simian immunodeficiency virus SIVcpz (11). There are currently up to 46 million people living with HIV-1 infection, many with AIDS (42). Lentiviral zoonosis is rare, due in part to the narrow host range of these viruses. Recent work aiming to identify the host factors responsible for such species-specific lentiviral replication has identified a number of proteins able to dominantly block infection and protect the host. One such host factor is CEM15/Apobec3G (32). This protein is packaged into the virion, where it catalyzes the deamination of the viral DNA, leading to hypermutation and loss of infectivity (22). The sole function of the viral vif gene appears to be to counteract CEM15/Apobec3G activity by causing its degradation (14, 25-27, 33).

Another dominant factor in human cells is able to block HIV-1 particle release and appears to be counteracted by the viral Vpu protein (40). Third, factors named Ref1 in humans and Lv1 in monkeys are able to block infection by a range of unrelated retroviruses (3, 9, 29, 37; reviewed in references 5 and 38). Ref1 is able to block a gammaretrovirus, murine leukemia virus, as well as an unrelated lentivirus from horses, equine infectious anemia virus. Lv1 from rhesus macaques can block HIV-1 and Lv1 from African green monkeys can block a range of lentiviruses, including HIV-1, HIV-2, SIVmac, and equine infectious anemia virus as well as murine leukemia virus (16). HIV-1 appears to have avoided restriction in humans by recruiting the host protein CypA rather than through the activity of a viral protein (39). Ref1 and Lv1 are termed restriction factors and are targeted against the incoming viral capsid protein encoded by the gag gene (9, 37).

The retroviral Gag polyprotein forms the structural core of the virion and is sufficient to direct retroviral particle formation and budding from the infected cell. The ordered cleavage of the HIV-1 Gag protein leads to the formation of a mature HIV-1 particle with its typical cone-shaped CA core. The details of the immediate fate of the viral core during and after viral entry remain largely unknown. Recent pioneering work with real-time live imaging of fluorescent HIV-1 cores trafficking within infected cells begins to provide some clues (28), as has the investigation of the structure of the HIV-1 early postentry reverse transcription complex by electron microscopy (31). This work has suggested that HIV-1 can traffic within a cell through an association with microtubules and that the reverse transcription complexes are large, loosely packed nucleoprotein structures. However, the details of host cell factor involvement in the early postentry events of retroviral infection remain unclear.

Restriction factors in humans (Ref1) and primates (Lv1) are able to block infection by broadly unrelated retroviruses, targeting the incoming retroviral capsid protein (16). The mechanism of restriction remains unclear. The block occurs very early postentry, before reverse transcription but after entry into the target cell. These activities are reminiscent of the mouse restriction factor Fv1 (reviewed in reference 13). The Fv1 gene is related to mammalian endogenous retroviral gag genes (2, 4). A key difference between Fv1 and Ref1/Lv1 is that Fv1-restricted virus is able to complete reverse transcription (19), while a Ref1- or Lv1-restricted virus is not (3, 9, 37). Integration, and perhaps nuclear entry, is blocked during Fv1-restricted infection (43). There are also a number of Fv1-independent restrictions to lentiviruses in murine cells which can be either capsid dependent or capsid independent (15).

Recently we have shown that HIV-1 has escaped restriction in human cells through an interaction between the HIV-1 CA protein and the host protein CypA (39). HIV-1 CA binds cellular CypA, leading to its incorporation into HIV-1 particles (10, 24, 36). Exactly how the CA-CypA interaction allows HIV-1 to become unrestricted is unclear, but the simplest model is that the CypA protein masks the restriction factor binding site on the incoming HIV-1 CA. The relationship between CypA binding and restriction has been investigated with a competitive inhibitor of CypA-CA interactions, cyclosporine A (CSA). CSA competes with CA for CypA binding, allowing the demonstration that CypA-free HIV-1 is restricted by a saturable factor in human cells. As with similar restricted infections, infectivity can be rescued by coinfection with restriction-sensitive virus-like particles (VLPs) which are assumed to soak up the factor (39).

Changes in gag sequence have been shown to alter HIV-1's CypA dependence (6, 45). We imagined that changes in sensitivity to CSA might reflect changes in sensitivity to restriction. We therefore investigated the relationship between natural sequence variation in HIV-1 gag and sensitivity to CSA and restriction by Ref1 and Lv1. We also sought to better understand the influence of gag on species-specific tropism.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell lines.

FRhK4 cells were obtained from the Centro Substrati Cellulari, Brescia, Italy. OMK and TE671 cells are from the European Collection of Cell Cultures (Porton Down, United Kingdom). 293T and CV1 are from the American Type Culture Collection. NP2 cells expressing human CD4 and CXCR4 have been previously described (34). All cells were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (Invitrogen) with 10% fetal calf serum and antibiotics except OMK cells, which were grown in minimal essential medium (Sigma) with 10% fetal calf serum, nonessential amino acids (Sigma), and 1% glutamine (Sigma).

Generation of HIV-1 gag-pol expression vectors.

HIV-1 gag-pol expression vector constructs were made with the construct pCMV-Δ8.91 (30), referred to here as p8.91. A NotI site was inserted into p8.91 by site-directed mutagenesis (Quikchange; Stratagene) with the oligonucleotides fwd (5′-GAGGCGAGGGGCGGCCGCTGGTGAGAGATGGG-3′) and rev (5′-CCCATCTCTCACCAGCGGCCGCCCCTCGCCTC-3′; NotI site italic). Gag DNA was then cloned into p8.91 (NotI) between the NotI site and the BclI site at plasmid nucleotide 3248 in the protease gene. Gag cDNAs were amplified by PCR with the oligonucleotides MVP5180 forward (ATCGATGCGGCCGCGGGAGGAAGATGGGTGCGAGAGC) and reverse (ATGCATTGATCATACTCTTTTACTTTTATAAAGCCTCC). All other gag sgenes were amplified with forward (ATAGCGGCCGCTGGTGAGAGATGGGTGCGAGAGCGTCAGTATTA) and reverse (CTATGAGTATCTGATCATACTGTCTTACTTTGATAA) (NotI and BclI sites italic). Template DNAs for gag PCR were obtained from the National Institutes of Health AIDS reagent program and were described (12). Mutagenesis of gag sequence was performed with the Quikchange strategy (Stratagene).

Viral vectors were prepared as previously described (3). Where vectors were pseudotyped with HIV-1 gp160, gp160 was expressed from pSVIII encoding the envelope gene from HXB2 (17). Infection assays and saturation assays were performed by plating 105 cells per well in six-well plates, 24 h prior to infection. Serial dilutions of virus were titrated onto the cells with 5 μg of Polybrene per ml. Green fluorescent protein (GFP)-positive cells were enumerated by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (Becton Dickinson) 48 h later. For saturation assays a serial dilution of VLPs (vesicular stomatitis virus G pseudotyped HIV-1 vector encoding resistance to puromycin) was coinfected with a fixed dose of GFP-encoding virus, chosen to infect between 0.2 and 1% of the target cells. Cyclosporine A injections (Sandoz) were diluted to 1 mM in dimethyl sulfoxide and added to cells at 2.5 μM final concentration.

RESULTS

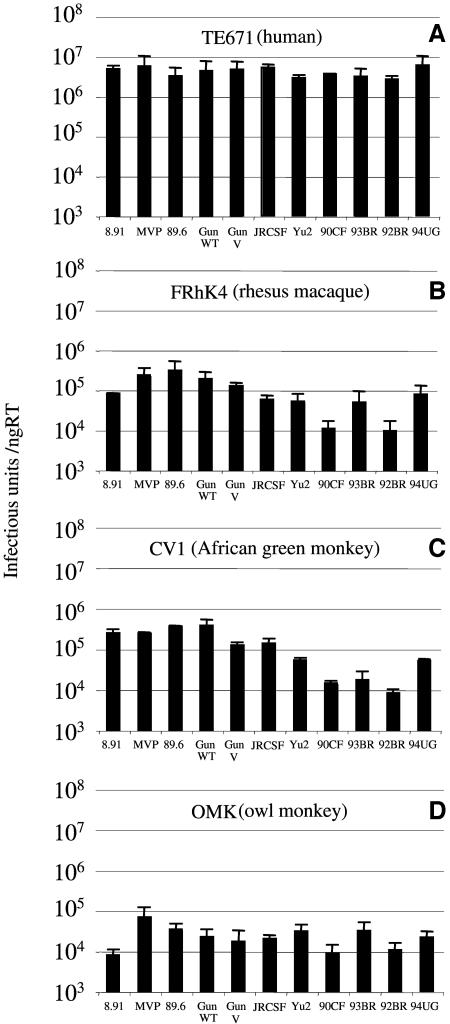

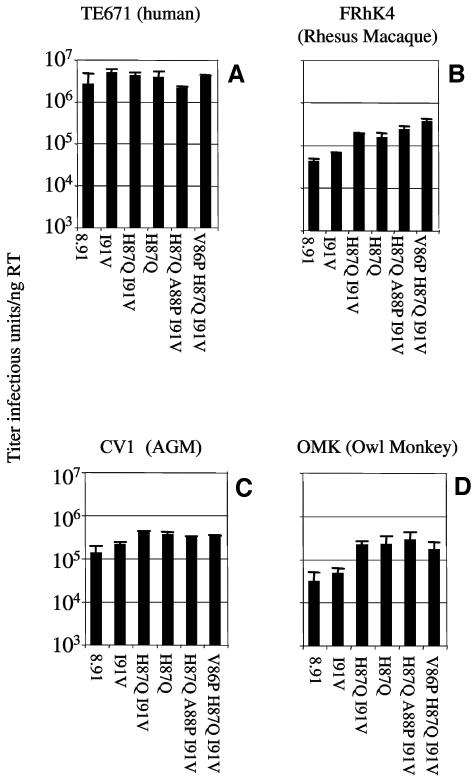

We generated or obtained gag-pol expression vectors encoding the full-length gag gene from 11 independently derived HIV-1 isolates. These constructs were used to make GFP-encoding, vesicular stomatitis virus G pseudotyped HIV-1 viral vectors by transfection of 293T cells as previously described (3). The reverse transcriptase activity of each virus was determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, and titers were determined on human TE671 cells (Fig. 1a), rhesus macaque FRhK4 cells (Fig. 1b), African green monkey CV1 cells (Fig. 1c), and owl monkey OMK cells (Fig. 1d). While the titers of the 11 HIV-1 vectors were very similar on human Ref1-positive TE671 cells, they varied considerably on the Lv1-positive simian cells. Titers were between 10- and 1,000-fold lower on simian cells, and the relative titers between the different Gags were similar between the two Old World monkey lines.

FIG. 1.

Titers of HIV-1 on cells from humans and monkeys. Cells from human (TE671) in panel A, rhesus macaque (FRhK4) in panel B, an African green monkey (CV1) in panel C, and owl monkey (OMK) in panel D were infected with HIV-1 vectors made with gag genes from the HIV-1 isolates as shown. Reverse transcriptase in each viral supernatant was measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (Cavidi Tech), and titers are shown as infectious units per nanogram of reverse transcriptase. Errors are standard errors of the mean. Titers were determined at infections of between 0.5 and 10% to ensure linearity of the infection assay.

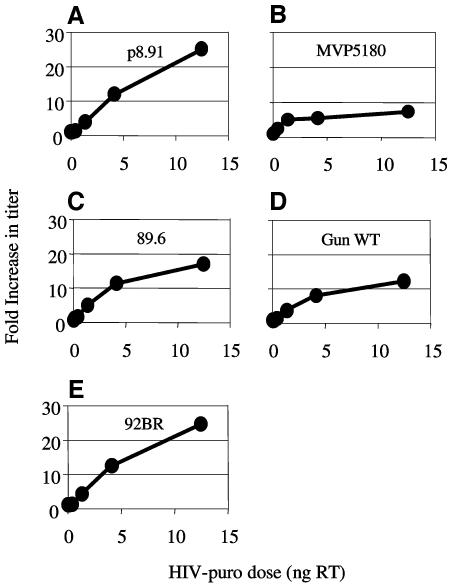

We next examined whether the highest titer (89.6) or the lowest titer (92BR) gag on Old World monkey cells could be explained by differences in their sensitivity to restriction by the primate restriction factor Lv1. In order to measure sensitivity to Lv1, we saturated Lv1 with p8.91 VLPs and coinfected with a fixed dose of each HIV-1 GFP (Fig. 2). The p8.91 VLP dose was able to completely saturate Lv1 activity as shown by a 25-fold increase in the titer of HIV-1 GFP (p8.91) (Fig. 2A). In each subsequent panel the same dose of p8.91 HIV-1 VLPs is used with a different HIV-1 GFP in each case. The fixed HIV-1 GFP dose chosen infected around 1% of the target cells, allowing the measurement of the increase in infection caused by saturating Lv1. Results are plotted as fold increase in titer against the dose of VLPs in ng reverse transcriptase. HIV-1 GFPs are made with gag from: the positive control (p8.91), Fig. 2A; MVP5180, Fig. 2B; 89.6, Fig. 2C; GunWT, Fig. 2D; and 92BR, Fig. 2E.

FIG. 2.

Sensitivity of HIV-1 Gags to Lv1 from rhesus macaques. Rhesus macaque FRhK4 cells were infected with a fixed dose of HIV-1 GFP made with gag from p8.91 (positive control, panel A), MVP5180 (panel B), 89.6 (panel C), GunWT (panel D), and 92BR (panel E) in the presence of increasing amounts of VLP made with the Lv1-sensitive gag from p8.91. Doses of HIV-1 encoding GFP were chosen to infect between 0.2 and 1% of the target cells. Values are plotted as the increase over the control (no VLP) against the VLP dose measured in nanograms of reverse transcriptase (RT). Values are representative of two independent experiments performed with two independent virus preparations.

Figure 2 shows that the relatively lower FRhK4 titers of 8.91 and 92BR can be partly explained by a stronger restriction by Lv1 (25 times), while the higher titers of 89.6, GunWT, and MVP5180 can be partly explained by a weaker sensitivity to Lv1 (between 8 and 17 times). We note that the least restricted Gag, MVP5180, has the highest infectivity on the strongest restrictors (OMK) and is also relatively high titer in FRhK4 and CV1 cells. Furthermore, 89.6 is high titer in FRhK4 and CV1 and less restricted than both p8.91 and 92BR. However the lowest titer virus in FRhK4, 92BR, is as restricted as p8.91. It seems therefore that sensitivity to Lv1 restriction can partly explain titers of the HIV-1 Gags in monkey cells, but it is clear that there are other determinants.

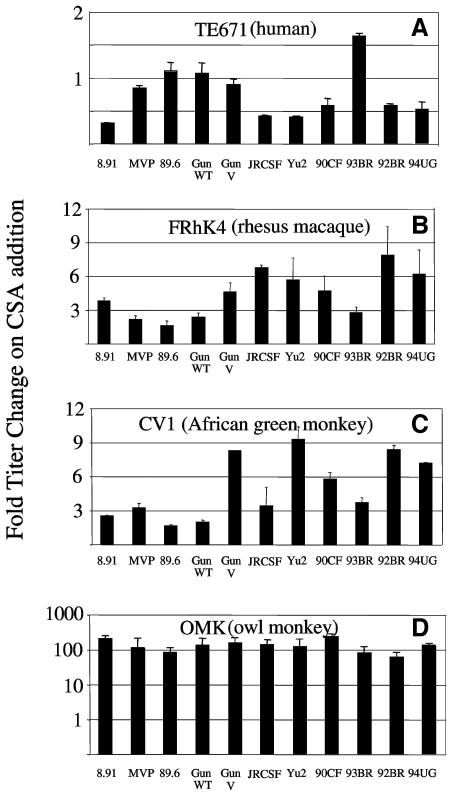

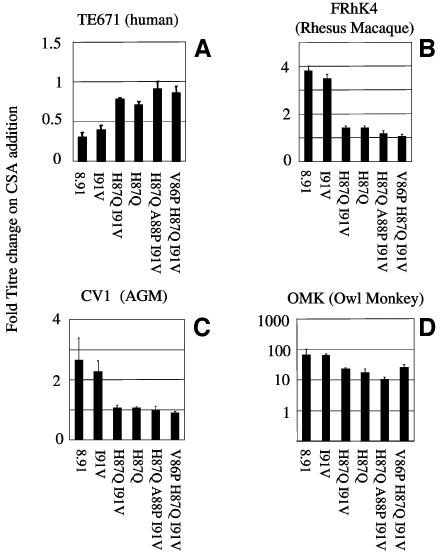

We have previously shown that HIV-1 becomes restricted in human cells when HIV-1 CA/CypA interactions are prevented (39). The drug CSA can block CA/CypA interactions by competing with Gag for CypA binding, leading to a loss in HIV-1 infectivity in human cells. Conversely in simian cells HIV-1 titers are increased by CSA suggesting that maximal restriction of HIV-1 by Lv1 is dependent on an interaction between CypA and the HIV-1 core. In order to test the influence of Gag sequence variation on species-specific CSA sensitivities, we titrated the 11 HIV-1 GFP vectors onto human and simian cell lines in the presence and absence of 2.5 μM CSA. Data are expressed as a percentage of the titer in the absence of CSA. A value less than 100% indicates a decrease in titer, whereas a value greater than 100% indicates an increase in titer, on CSA addition. The most CSA-sensitive virus in human cells was p8.91, with a threefold decrease in titer on CSA addition (Fig. 3A). A number of viruses appear to be CSA independent in human cells, namely, MVP5180, 89.6, GunWT, and GunV. Intriguingly, the 93BR titer on TE671 cells is increased by CSA treatment (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

Effect of CSA on HIV-1 titer. The titer of HIV-1 GFP vectors was determined in the presence and absence of 2.5 μM CSA on human TE671 cells (panel A), rhesus macaque FRhK4 cells (panel B), African green monkey CV1 cells (panel C), and owl monkey OMK cells (panel D). Values are expressed as change in titer compared to the titer in the absence of CSA. Errors are standard errors of the mean. Titers were determined at infections of between 0.5 and 10% to ensure linearity of the infection assay.

In owl monkey cells, CSA treatment increases HIV-1 GFP titers, indicating that CypA/CA interactions are required for maximal restriction by Lv1 (39). Here, with a variety of HIV-1 Gag sequences, we extend this observation to macaque and African green monkey cells. In macaque cells, the response to CSA varies between less than 3-fold (89.6) to nearly 10-fold (92BR). In CV1 cells the variation is similar. However, the strongest response to CSA is seen in cells from owl monkeys, where all virus titers are increased by around 100-fold by CSA treatment.

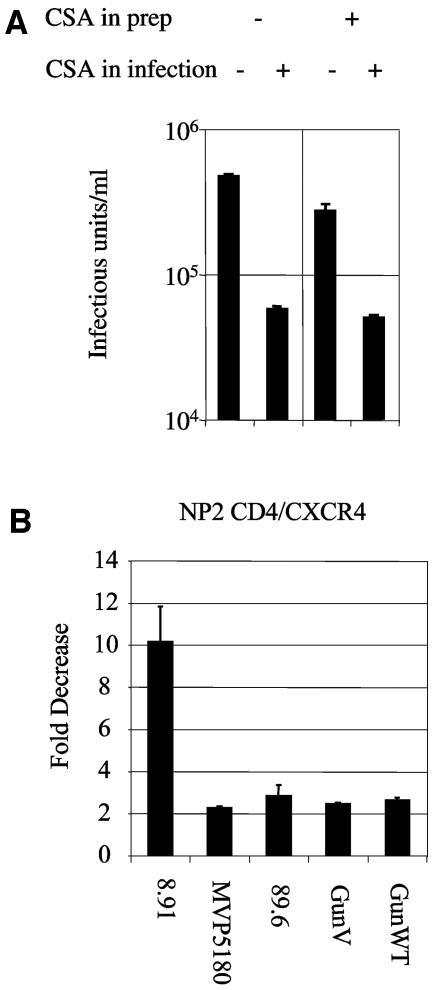

In order to examine the importance of CypA in the context of a natural HIV-1 envelope/receptor interaction, we pseudotyped HIV-1 GFP with gp160. First we compared the titers of gp160 pseudotyped HIV-1 GFP vector produced in the presence and absence of 2.5 μM CSA, i.e., the titers of CypA+ and CypA− virus. Both have similar titers on NP2 CD4/CXCR4 cells (Fig. 4A). Addition of CSA to the infection of either CypA+ or CypA− virus reduces infectivity by around 10-fold (Fig. 4A). We then tested whether CSA was able to reduce the titer of gp160 pseudotyped, CypA independent, MVP5180, 89.6, Gun V and Gun WT. CSA addition caused a 10-fold reduction in titer of HIV-1 GFP p8.91, whereas the titer of the 4 CSA independent HIV-1s was only reduced by 2 fold (Fig. 4B). These data indicate that gp160 pseudotyped HIV-1 behaves similarly to vesicular stomatitis virus G pseudotyped HIV-1 in terms of timing of CypA dependence and extend observations of CypA independence to M group viruses 89.6, GunWT, and GunV. A similar experiment performed on NP2 cells with vesicular stomatitis virus G pseudotyped HIV-1 8.91 gave around a threefold decrease on CSA addition, indicating that vesicular stomatitis virus G partially overcomes the requirement for CypA, as previously described (1) (data not shown).

FIG. 4.

Target cell CypA can rescue HIV-1 denuded of CypA. A: HIV-1 GFP pseudotyped with HXB2 gp160 was prepared by transfection of 293T cells in the presence or absence of 2.5 μM CSA. NP2 cells expressing CD4 and CXCR4 were then infected in the presence and absence of 2.5 μM CSA. B: gp160 pseudotyped HIV-1 containing Gags from MVP5180, 89.6, GunWT, and GunV have reduced sensitivity to CSA on NP2 cells expressing CD4 and CXCR4. Values are plotted as the decrease after addition of 2.5 μM CSA to the infection compared to the untreated control. Errors are standard errors of the mean.

An aim of this work is to generate an unrestricted HIV-1 better able to replicate in rhesus macaques, the current animal model for AIDS. We therefore attempted to increase the titer of p8.91 in FRhK4 cells by changing capsid sequences in the CypA binding loop to those from viruses better able to infect macaque cells. Firstly we made p8.91 capsid V83L H87Q I91V (HIV-1 89.6). V83L H87Q and V83L I91V mutants were also made. We mutated H87Q, A88P, I91V (HIV-1 Ba-L) (21) and V86P H87Q I91V (HIV-1 92UG) (12). The titers were measured in human and simian cell lines (Fig. 5). These data show that, as expected, these changes do not significantly alter the titer in human cells (Fig. 5A). However H87Q, Ba-L and 92UG changes specifically increase the titers in simian cells (Fig. 5B to D). A number of CypA binding loop sequences are therefore able to specifically increase the titer in simian but not in human cells.

FIG. 5.

HIV-1 GFP capsid mutants have increased species-specific titer on simian cells. The titers of HIV-1 GFP capsid mutants were measured on human TE671 cells (panel A), rhesus macaque FRhK4 cells (panel B), African green monkey CV1 cells (panel C), and owl monkey OMK cells (panel D). Errors are standard errors of the mean. Titers were determined at infections of between 0.5 and 10% to ensure linearity of the infection assay.

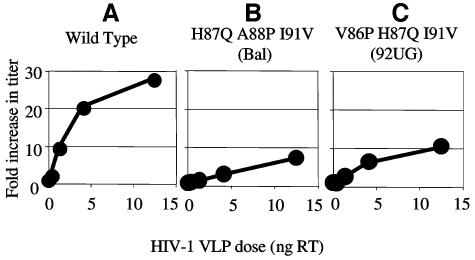

We then measured the sensitivity of the modified capsids to CSA in order to measure their CypA dependence (Fig. 6). In all cell lines, the changes that specifically increase titer in simian cells decrease sensitivity to CSA. In human cells the mutations decrease the dependence of HIV-1 on CypA, whereas in simian cells the mutations decrease the stimulation of HIV-1 by CSA. We predict that the changes in CSA sensitivity of the mutant viruses indicate changes in sensitivity to restriction by Lv1 in simian cells. This appears to be the case (Fig. 7). Lv1 saturation assays show that the two mutants with the highest titers and the lowest CSA sensitivities in FRhK4 cells are restricted significantly less than the wild-type p8.91 HIV-1 GFP. The Ba-L titer is increased by only 10-fold after saturation of Lv1 (Fig. 7B) and the 92UG titer is increased by less than 10-fold (Fig. 7C). These increases are significantly less than the 25-fold increase in wild-type p8.91 titer (Fig. 7A), indicating a reduced sensitivity of the mutants to Lv1.

FIG. 6.

Effect of CSA on HIV-1 capsid mutants. The titers of HIV-1 GFP capsid mutants were determined in the presence and absence of 2.5 μM CSA on human TE671 cells (panel A), rhesus macaque FRhK4 cells (panel B), African green monkey CV1 cells (panel C), and owl monkey OMK cells (panel D). Values are expressed as the difference in titer compared to the titer determined in the absence of CSA. Errors are standard errors of the mean. Titers were determined at infections of between 0.5 and 10% to ensure linearity of the infection assay.

FIG. 7.

Sensitivity of HIV-1 GFP capsid mutants to Lv1 from rhesus macaques. Rhesus macaque FRhK4 cells were infected with a fixed dose of HIV-1 GFP made with wild-type p8.91 capsid mutants in panel A, H87Q A88P I91V (Ba-L) in panel B, and V86P H87Q I91V (92UG) in panel C in the presence of increasing amounts of VLP made with the Lv1-sensitive Gag from p8.91. Doses of HIV-1 GFP were chosen to infect between 0.2 and 1% of the target cells. Values plotted are the increase over the control (no VLP) against the VLP dose. Values are representative of two independent experiments performed with two independent virus preparations.

DISCUSSION

We used 11 different gag-pol expression vectors derived from HIV-1 samples from a variety of geographic regions to generate GFP-encoding HIV-1 vectors. The 11 viruses gave similar titers on human cells but various titers on simian cells. This indicates that these Gags are equally adapted to infection of human cells and that gag encodes determinants of species-specific infection in monkeys. The differences can be explained in part through sensitivity to the simian restriction factor Lv1. Saturation of Lv1 with HIV-1 VLPs rescues the infectivity of the most infectious viruses least, indicating that they are the least restricted. These data also suggest that there are further determinants of species specificity encoded within the gag gene that are unrelated to saturable restriction factors. We imagine that the other determinants may be related to species-specific fitness. We speculate, for example, that 92BR might be less able to interact with a necessary rhesus macaque host cell factor(s) than 89.6, whereas both viruses are equally able to interact with the human host factors.

We then measured the importance of an interaction between the various capsids and the host protein CypA. We demonstrate that a number of wild type HIV-1 Gags are insensitive to CSA treatment (Fig. 3), as are a number of mutants of 8.91 Gag (Fig. 6). A CSA-insensitive phenotype has been previously described for some O group HIV-1 strains, including the MVP5180 virus used here (7, 42). These viruses were shown to be able to bind CypA, CypA was competed effectively from CA by CSA, but viral infectivity was unaffected, indicating CypA independence. Our data show that such CypA independence in human cells is not a unique property of O group viruses and several subtype B, M group viruses (89.6, GunWT, and GunV) have been identified.

We show that target cell CypA and not particle-associated CypA is important for gp160 pseudotyped HIV-1 infectivity as well as vesicular stomatitis virus G pseudotyped virus. CypA-positive virus and CypA-free virus are almost equally infectious, and the infectivity of either is reduced by 10-fold on addition of CSA at the time of infection. This experiment clearly shows that the important CypA interaction, allowing HIV-1 to avoid restriction, takes place during infection. We imagine that CypA is found in the core as a consequence of CypA-CA interactions taking place during viral assembly. Further, we speculate that the fact that only 1 in 10 CA molecules is bound to CypA in the core (46) suggests that, on infection, more and perhaps all of the capsid molecules might bind the abundant target cell CypA. It will be interesting to investigate the influence of producer cell CypA levels, particularly cell types relevant in vivo, such as T cells and macrophages.

The notion that HIV-1 is protected from Ref1-mediated restriction through its interaction with CypA is supported by analysis of the HIV-1 capsid mutants. Altering the capsid sequence to reduce restriction has no effect on HIV-1 titer in human cells because target cell CypA blocks HIV-1 restriction. The reduced restriction is revealed only when the protective CypA is removed with CSA. Therefore, the titer of a sensitive virus (p8.91) is reduced by CSA treatment, whereas the titers of relatively insensitive viruses (Ba-L and 92BR) remain unchanged (Fig. 5). Furthermore, restriction sensitivity in humans predicts restriction sensitivity in monkeys. Therefore, the viruses with reduced Ref1 sensitivity (Ba-L and 92BR loop viruses) have higher titers on simian cells. Furthermore, their decreased sensitivity to Lv1 bestows reduced sensitivity to CSA. We hypothesize that CypA forms an essential part of the Lv1 virus complex, as revealed by a decrease in restriction on CSA addition in simian cells. If a virus is insensitive to Lv1, then the effect of CypA removal is negated, as is the case for the Ba-L and 92BR loops. We are confident that all wild-type and mutant viruses are able to bind CypA and that this interaction is blocked by CSA, as all viruses have the glycine-proline CypA binding site intact and all are rendered unrestricted in OMK cells on addition of CSA (Fig. 1D and 6D).

CSA is known to bind many members of the cyclophilin family (reviewed in reference 18), and so it is formally possible that the effects of CSA, added at the time of infection, are through interaction with any one of the cyclophilins able to bind CSA. However as CypA is the most abundant cyclophilin and is found in the cytoplasm, it remains the most likely cyclophilin to be involved in the protection of HIV-1 from Ref1. Furthermore, a T-cell line with the CypA gene knocked out is unable to replicate HIV-1 (8). The amino acid sequences of CypA from humans, rhesus macaques, and African green monkeys are identical (44), suggesting that the opposite effects of CSA in humans and monkeys are due to differences between Ref1 and Lv1. We speculate that HIV-1's affinity for CypA and the consequent protection from Ref1 have allowed HIV-1 to colonize the human population, whereas this acquisition might prevent it from spreading to rhesus macaques, African green monkeys, or owl monkeys. It is interesting that the viral titers and pattern of CSA sensitivities are similar in the two Old World monkeys, rhesus macaques and African green monkeys, but different between humans and Old and New World monkeys. This presumably reflects the relatedness of these species and of their restriction factors.

We note with interest the recent observation that the H87Q change is selected in HIV-1 that has escaped cytotoxic T lymphocyte responses (23). It is proposed that this mutation might be linked to a fitness advantage in the context of the cytotoxic T lymphocyte escape mutant. Our data would suggest that this fitness advantage might be due to a decrease in sensitivity to Ref1 (Fig. 6). We suggest a link between immune and innate host defenses against retroviral infection. The recent identification of TRIM5α as a restriction factor in humans and monkeys (20, 35) will allow a more detailed analysis of the relationship between restriction and immunology.

Acknowledgments

We thank Paul Bieniasz, Yasuhiro Takeuchi, and Srinika Ranasinghe for helpful discussions.

This work was supported by a Wellcome Trust RCDF (no 064257) to G.J.T. and by Cancer Research United Kingdom to Y.I. M.K.-B. is a University of Malaya/Malaysian Public Services Dept. scholar.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aiken, C. 1997. Pseudotyping human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) by the glycoprotein of vesicular stomatitis virus targets HIV-1 entry to an endocytic pathway and suppresses both the requirement for Nef and the sensitivity to cyclosporin A. J. Virol. 71:5871-5877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Benit, L., N. De Parseval, J.-F. Casella, I. Callebaut, A. Cordonnier, and T. Heidmann. 1997. Cloning of a new murine retrovirus, MuERV-L with strong similarity to the human HERV-L element and with a gag coding sequence closely related to the Fv1 restriction gene. J. Virol. 71:5652-5657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Besnier, C., Y. Takeuchi, and G. Towers. 2002. Restriction of lentivirus in monkeys. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:11920-11925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Best, S., P. Le Tissier, G. Towers, and J. P. Stoye. 1996. Positional cloning of the mouse restriction gene Fv1. Nature 382:826-829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bieniasz, P. D. 2003. Restriction factors: a defense against retroviral infection. Trends Microbiol. 11:286-291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Braaten, D., C. Aberham, E. K. Franke, L. Yin, W. Phares, and J. Luban. 1996. Cyclosporine A-resistant human immunodeficiency virus type 1 mutants demonstrate that Gag encodes the functional target of cyclophilin A. J. Virol. 70:5170-5176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Braaten, D., E. K. Franke, and J. Luban. 1996. Cyclophilin A is required for the replication of group M human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) and simian immunodeficiency virus SIV(CPZ)GAB but not group O HIV-1 or other primate immunodeficiency viruses. J. Virol. 70:4220-4227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Braaten, D., and J. Luban. 2001. Cyclophilin A regulates HIV-1 infectivity, as demonstrated by gene targeting in human T cells. EMBO J. 20:1300-1309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cowan, S., T. Hatziioannou, T. Cunningham, M. A. Muesing, H. G. Gottlinger, and P. D. Bieniasz. 2002. Cellular inhibitors with Fv1-like activity restrict human and simian immunodeficiency virus tropism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:11914-11919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Franke, E. K., H. E. Yuan, and J. Luban. 1994. Specific incorporation of cyclophilin A into HIV-1 virions. Nature 372:359-362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gao, F., E. Bailes, D. L. Robertson, Y. Chen, C. Rodenburg, S. F. Michael, L. B. Cummins, L. O. Arthur, M. Peeters, G. M. Shaw, and B. H. Hahn. 1999. Origin of HIV-1 in the chimpanzee Pan troglodytes troglodytes. Nature 397:436-441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gao, F., D. L. Robertson, C. D. Carruthers, S. G. Morrison, B. Jian, Y. Chen, F. Barre-Sinoussi, M. Girard, A. Srinivasan, A. G. Abimiku, G. M. Shaw, P. M. Sharp, and B. H. Hahn. 1998. A comprehensive panel of near-full-length clones and reference sequences for non-subtype B isolates of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J. Virol. 72:5680-5698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goff, S., P. 1996. Operating under a Gag order: a block against incoming virus by the Fv1 gene. Cell 86:691-693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harris, R. S., K. N. Bishop, A. M. Sheehy, H. M. Craig, S. K. Petersen-Mahrt, I. N. Watt, M. S. Neuberger, and M. H. Malim. 2003. DNA deamination mediates innate immunity to retroviral infection. Cell 113:803-809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hatziioannou, T., S. Cowan, and P. D. Bieniasz. 2004. Capsid-dependent and independent postentry restriction of primate lentivirus tropism in rodent cells. J. Virol. 78:1006-1011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hatziioannou, T., S. Cowan, S. P. Goff, P. D. Bieniasz, and G. J. Towers. 2003. Restriction of multiple divergent retroviruses by Lv1 and Ref1. EMBO J. 22:1-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Helseth, E., M. Kowalski, D. Gabuzda, U. Olshevsky, W. Haseltine, and J. Sodroski. 1990. Rapid complementation assays measuring replicative potential of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope glycoprotein mutants. J. Virol. 64:2416-2420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ivery, M. T. 2000. Immunophilins: switched on protein binding domains? Med. Res. Rev. 20:452-484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jolicoeur, P., and E. Rassart. 1980. Effect of Fv-1 gene product on synthesis of linear and supercoiled viral DNA in cells infected with murine leukemia virus. J. Virol. 33:183-195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Keckesova, Z., L. M. J. Ylinen, and G. J. Towers. 2004. The human and African green monkey TRIM5a genes encode Ref1 and Lv1 retroviral restriction factor activities. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101:10780-10785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kootstra, N. A., C. Munk, N. Tonnu, N. R. Landau, and I. M. Verma. 2003. Abrogation of postentry restriction of HIV-1-based lentiviral vector transduction in simian cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100:1298-1303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lecossier, D., F. Bouchonnet, F. Clavel, and A. J. Hance. 2003. Hypermutation of HIV-1 DNA in the absence of the Vif protein. Science 300:1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Leslie, A. J., K. J. Pfafferott, P. Chetty, R. Draenert, M. M. Addo, M. Feeney, Y. Tang, E. C. Holmes, T. Allen, J. G. Prado, M. Altfeld, C. Brander, C. Dixon, D. Ramduth, P. Jeena, S. A. Thomas, A. St John, T. A. Roach, B. Kupfer, G. Luzzi, A. Edwards, G. Taylor, H. Lyall, G. Tudor-Williams, V. Novelli, J. Martinez-Picado, P. Kiepiela, B. D. Walker, and P. J. Goulder. 2004. HIV evolution: CTL escape mutation and reversion after transmission. Nat. Med. 10:282-289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Luban, J., K. L. Bossolt, E. K. Franke, G. V. Kalpana, and S. P. Goff. 1993. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Gag protein binds to cyclophilins A and B. Cell 73:1067-1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mangeat, B., P. Turelli, G. Caron, M. Friedli, L. Perrin, and D. Trono. 2003. Broad antiretroviral defence by human APOBEC3G through lethal editing of nascent reverse transcripts. Nature 424:99-103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mariani, R., D. Chen, B. Schrofelbauer, F. Navarro, R. Konig, B. Bollman, C. Munk, H. Nymark-McMahon, and N. R. Landau. 2003. Species-specific exclusion of APOBEC3G from HIV-1 virions by Vif. Cell 114:21-31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Marin, M., K. M. Rose, S. L. Kozak, and D. Kabat. 2003. HIV-1 Vif protein binds the editing enzyme APOBEC3G and induces its degradation. Nat. Med. 9:1398-1403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McDonald, D., M. A. Vodicka, G. Lucero, T. M. Svitkina, G. G. Borisy, M. Emerman, and T. J. Hope. 2002. Visualization of the intracellular behavior of HIV in living cells. J. Cell Biol. 159:441-452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Munk, C., S. M. Brandt, G. Lucero, and N. R. Landau. 2002. A dominant block to HIV-1 replication at reverse transcription in simian cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:13843-13848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Naldini, L., U. Blömer, P. Gallay, D. Ory, R. Mulligan, F. H. Gage, I. M. Verma, and D. Trono. 1996. In vivo gene delivery and stable transduction of non-dividing cells by a lentiviral vector. Science 272:263-267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nermut, M. V., and A. Fassati. 2003. Structural analyses of purified human immunodeficiency virus type 1 intracellular reverse transcription complexes. J. Virol. 77:8196-8206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sheehy, A. M., N. C. Gaddis, J. D. Choi, and M. H. Malim. 2002. Isolation of a human gene that inhibits HIV-1 infection and is suppressed by the viral Vif protein. Nature 418:646-650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sheehy, A. M., N. C. Gaddis, and M. H. Malim. 2003. The antiretroviral enzyme APOBEC3G is degraded by the proteasome in response to HIV-1 Vif. Nat. Med. 9:1404-1407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Soda, Y., N. Shimizu, A. Jinno, H. Y. Liu, K. Kanbe, T. Kitamura, and H. Hoshino. 1999. Establishment of a new system for determination of coreceptor usages of HIV based on the human glioma NP-2 cell line. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 258:313-321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stremlau, M., C. M. Owens, M. J. Perron, M. Kiessling, P. Autissier, and J. Sodroski. 2004. The cytoplasmic body component TRIM5alpha restricts HIV-1 infection in Old World monkeys. Nature 427:848-853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thali, M., A. Bukovsky, E. Kondo, B. Rosenwirth, C. T. Walsh, J. Sodroski, and H. G. Gottlinger. 1994. Functional association of cyclophilin A with HIV-1 virions. Nature 372:363-365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Towers, G., M. Bock, S. Martin, Y. Takeuchi, J. P. Stoye, and O. Danos. 2000. A conserved mechanism of retrovirus restriction in mammals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:12295-12299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Towers, G. J., and S. P. Goff. 2003. Post entry restriction of retroviral infections. AIDS Rev. 5:156-164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Towers, G. J., T. Hatziioannou, S. Cowan, S. P. Goff, J. Luban, and P. D. Bieniasz. 2003. Cyclophilin A modulates the sensitivity of HIV-1 to host restriction factors. Nat. Med. 9:1138-1143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Varthakavi, V., R. M. Smith, S. P. Bour, K. Strebel, and P. Spearman. 2003. Viral protein U counteracts a human host cell restriction that inhibits HIV-1 particle production. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100:15154-15159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Weigers, K., and H. G. Krausslich. 2002. Differential dependence of the infectivity of HIV-1 group O isolates on the cellular protein cyclophilin A. Virology 294:289-295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.World Health Organization. December2003, posting date. AIDS epidemic update 2003. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland. (Online.)

- 43.Yang, W. K., J. O. Kiggans, D. M. Yang, C. Y. Ou, R. W. Tennant, A. Brown, and R. H. Bassin. 1980. Synthesis and circularization of N- and B-tropic retroviral DNA Fv-1 permissive and restrictive mouse cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 77:2994-2998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yin, L., S. Boussard, J. Allan, and J. Luban. 1998. The HIV type 1 replication block in nonhuman primates is not explained by differences in cyclophilin A primary structure. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses 14:95-97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yin, L., D. Braaten, and J. Luban. 1998. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 replication is modulated by host cyclophilin A expression levels. J. Virol. 72:6430-6436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yoo, S., D. G. Myszka, C. Yeh, M. McMurray, C. P. Hill, and W. I. Sundquist. 1997. Molecular recognition in the HIV-1 capsid/cyclophilin A complex. J. Mol. Biol. 269:780-795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]