Abstract

Varicella-zoster virus (VZV) expresses at least six viral transcripts during latency. One of these transcripts, derived from open reading frame 63 (ORF63), is one of the most abundant viral RNAs expressed during latency. The VZV ORF63 protein has been detected in human and experimentally infected rodent ganglia by several laboratories. We have deleted >90% of both copies of the ORF63 gene from the VZV genome. Animals inoculated with the ORF63 mutant virus had lower mean copy numbers of latent VZV genomes in the dorsal root ganglia 5 to 6 weeks after infection than animals inoculated with parental or rescued virus, and the frequency of latently infected animals was significantly lower in animals infected with the ORF63 mutant virus than in animals inoculated with parental or rescued virus. In contrast, the frequency of animals latently infected with viral mutants in other genes that are equally or more impaired for replication in vitro, compared with the ORF63 mutant, is similar to that of animals latently infected with parental VZV. Examination of dorsal root ganglia 3 days after infection showed high levels of VZV DNA in animals infected with either ORF63 mutant or parental virus; however, by days 6 and 10 after infection, the level of viral DNA in animals infected with the ORF63 mutant was significantly lower than that in animals infected with parental virus. Thus, ORF63 is not required for VZV to enter ganglia but is the first VZV gene shown to be critical for establishment of latency. Since the present vaccine can reactivate and cause shingles, a VZV vaccine based on the ORF63 mutant virus might be safer.

Acute infection with varicella-zoster virus (VZV) causes chickenpox. The virus spreads throughout the body and infects the nervous system. Latent infection is established in dorsal root and cranial nerve ganglia, and the virus can subsequently reactivate and cause zoster (shingles). Several VZV gene products have been shown to be expressed during latency. Transcripts encoding VZV open reading frame 4 (ORF4), ORF21, ORF29, ORF62, ORF63, and ORF66 (3, 4, 10, 21) have been detected in latently infected human ganglia. ORF63 transcripts are among the most abundant VZV mRNAs expressed during latency in some studies and have been detected in 47 to 86% of human ganglia (4, 10). ORF63 mRNA is also one of the most frequently expressed viral genes in latently infected rodent ganglia (11, 25).

The ORF63 protein has been detected in neurons of latently infected human (10, 18, 20) and rodent (6, 11) ganglia. The protein is present in the cytoplasm of neurons during latency; however, during reactivation and in cell culture, the protein is present in both the nucleus and cytoplasm (18, 20, 25). VZV ORF63 is expressed as an immediate-early protein and is present in virions (13). While earlier studies reported conflicting results about the transregulatory activity of ORF63 (8, 14), Bontems et al. (1) found that in transient-expression assays ORF63 repressed the VZV thymidine kinase and DNA polymerase promoters. Repression of viral genes by ORF63 during latency might be a mechanism by which the virus could limit gene expression and avoid replication.

A previous study reported that VZV ORF63 is essential for growth of the virus in cell culture (32). Due to the association of ORF63 transcripts with VZV latency in both human and animal models, we attempted to construct a mutant virus that did not express ORF63. Here we show that ORF63 is actually not required for growth in cell culture; however, unlike two of the other latency genes (ORF21 and ORF66) that have been tested thus far, ORF63 has a critical role in establishment of latent infection.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cosmids and transfections.

Cosmids VZV NotIA, NotIBD, MstIIA, and MstIIB are derived from the Oka vaccine strain and encompass the entire VZV genome. Transfection of these cosmids into cells results in production of infectious virus. VZV ORF63 is located in the short internal repeat region of the viral genome, and a duplicate copy of the gene, termed ORF70, is located in the short terminal repeat of the genome (see Fig. 1). Both ORF63 and ORF70 are located within an SfiI fragment extending from VZV nucleotides 109045 to 120854 (5). To clone the VZV SfiI fragment, two SfiI sites were inserted into pBluescript SK+ (pBSSK+) (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.). pBSSK+ was modified to include the first SfiI site by cutting the plasmid with SpeI and SmaI, and a double-stranded DNA, derived from CTAGTTGGCCGCGGCGGCCTCCC and GGGAGGCCGCCGCGGCCAA, was inserted into the site. This SfiI site is compatible with the SfiI site at VZV nucleotide 109045. A second SfiI site, compatible with the SfiI site at VZV nucleotide 120854, was created by digesting the modified pBSSK+ plasmid with EcoRI and HindIII, and a double-stranded DNA, derived from AATTGTAGGCCGCCGCGGCCA and AGCTTGGCCGCGGCGGCCTAC, was inserted into the site. The resulting plasmid was cut with SfiI, and the SfiI fragment from cosmid MstIIA, containing ORF63 and ORF70 (VZV nucleotides 109045 to 120854), was inserted to create plasmid pBSSK+SfiI.

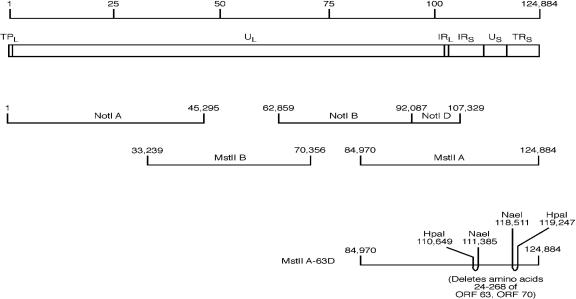

FIG. 1.

Construction of recombinant VZV with a deletion in ORF63 and ORF70. The VZV genome is 124,884 bp long (top line) and contains unique long (UL), unique short (US), internal repeat (IR), and terminal repeat (TR) regions. The four cosmids used to produce infectious virus (cosmids VZV NotIA, NotIBD, MstIIB, and MstIIA) span the VZV genome are shown in the middle of the figure. In cosmid MstIIA-63D, codons 24 to 268 of ORF63 and ORF70 (with a frameshift after codon 268) were deleted.

A modified plasmid pBSSK+ in which the NgoMI and ClaI sites were eliminated was constructed. First, plasmid pBSSK+ was cut with NgoMI, and a double-stranded oligonucleotide, derived from CCGGAGAGCCTAGGAGACT and CCGGAGTCTCCTAGGCTCT, was inserted into the site. The resulting plasmid, pBSSK+AvrII, now contains an AvrII site. Plasmid pBSSK+AvrII was cut with ClaI and KpnI, and a single-stranded oligonucleotide, CGGTAC, was inserted into the site to create plasmid pBSSK+AvrIIdCla.

The ORF63 gene from plasmid pBSSK+SfiI was inserted into plasmid pBSSK+AvrIIdCla. Plasmid pBSSK+SfiI was cut with SpeI (which is located in pBSSK+ adjacent to the site of the VZV insert) and EcoRI (located at VZV nucleotide 117034), and the resulting 3.9-kb fragment was inserted into the SpeI and EcoRI sites of pBSSK+AvrIIdCla to create plasmid ES. Next, the ORF70 gene from plasmid pBSSK+SfiI was inserted into plasmid pBSSK+AvrIIdCla. Plasmid pBSSK+SfiI was cut with AvrII (which is located at VZV nucleotide 112853) and HindIII (which is located in pBSSK+ adjacent to the site of the VZV insert), and the resulting 3.9-kb fragment was inserted into the AvrII and HindIII sites of pBSSK+AvrIIdCla to create plasmid AH.

The ORF63 and ORF70 genes were deleted from plasmids ES and AH, respectively. Plasmid ES was cut with HpaI (VZV nucleotide 110649) and NaeI (VZV nucleotide 111385), and the large, blunt-ended fragment was ligated to itself. Similarly, plasmid AH was cut with HpaI (VZV nucleotide 119247) and NaeI (VZV nucleotide 118511), and the large fragment was ligated to itself. Mutated plasmid ES was cut with EcoRI and SpeI, and the fragment in which ORF63 had been deleted was inserted in place of the wild-type EcoRI-SpeI fragment into plasmid pBSSK+SfiI. Mutated plasmid AH was cut with AvrII and HindIII, and the fragment in which ORF70 had been deleted was substituted for the wild-type AvrII-HindIII fragment of plasmid pBSSK+SfiI in which ORF63 had been deleted. Finally, plasmid pBSSK+SfiI in which ORF63 and ORF70 had been deleted was cut with SfiI, and the resulting fragment was substituted for the wild-type SfiI fragment of cosmid MstIIA. The resulting cosmid, termed MstIIA-63D, has identical deletions of ORF63 and ORF70 that result in loss of codons 24 to 268; the remaining codons (269 to 278) are out of frame. Two independently derived clones of plasmids ES and AH were obtained, and subsequent reactions were performed in parallel. Thus, two independently derived cosmids, MstIIA-63DA and MstII63-DB were obtained.

Recombinant VZV was produced by transfecting human melanoma (MeWo) cells with a plasmid expressing VZV ORF62 protein (pCMV62), with cosmids VZV NotIA, NotIBD, MstIIB, and either MstIIA, MstIIA-63DA, or MstIIA-63DB. To rescue the deletion in the ORF63 mutant, 0.5 μg of virion DNA from the ORF63 deletion mutant was cotransfected with 1.5 μg of a BclI DNA fragment that contains ORF63 and its promoter (VZV nucleotides 106592 to 112215).

Southern blotting, immunoblotting, immunoprecipitation, and growth studies.

Southern blotting was performed by isolating VZV DNA from nucleocapsids, cutting the DNA with restriction enzymes, and fractionating the DNA on 0.8% agarose gels. After transfer to a nylon membrane, the blot was probed with a [32P]dCTP-radiolabeled probe that contains the ORF63 gene. Immunoblotting was performed by preparing protein lysates of VZV-infected cells, fractionating the proteins on polyacrylamide gels, transferring the proteins to membranes, and incubating the blots with rabbit antibody to the ORF63 protein (22) (a gift of Paul Kinchington) or mouse monoclonal antibody to glycoprotein E (gE) (Chemicon, Temecula, Calif.). The membranes were then incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit or anti-mouse antibody and developed with an enhanced chemiluminescence kit (Pierce Chemical Company, Rockfield, Ill.).

Immunoprecipitation was performed by radiolabeling virus-infected cells with [35S]methionine, lysing the cells, and immunoprecipitating viral proteins with antibodies to VZV thymidine kinase (a gift of Christine Talarico) or gE, followed by the addition of protein A Sepharose. The immunoprecipitates were run on polyacrylamide gels, and autoradiography was performed.

Flasks of melanoma cells were infected with 100 to 200 PFU of VZV, and at days 1 to 5 after infection, the cells were treated with trypsin, and serial dilutions were used to infect melanoma cells. One week later, the cells were fixed and stained with crystal violet, and plaques were counted.

Analysis of acute or latent infection.

Four- to 6-week-old female cotton rats were inoculated intramuscularly along both sides of the spine with VZV-infected melanoma cells containing 1.75 × 105 or 3.0 × 105 PFU of recombinant viruses as previously described (26). Three to 10 days (for acute infection) or 5 to 6 weeks (for latent infection) after inoculation, the animals were sacrificed, and thoracic and lumbar ganglia on the left side from each animal were pooled and used to prepare DNA, while ganglia from the right side were used to prepare RNA. Approximately 10 μg of DNA and 25 μg of RNA were obtained from each animal. DNA was isolated, and PCR was performed using 500 ng of pooled ganglia DNA and VZV primers corresponding to the ORF21 gene of VZV (2). Serial dilutions of cosmid VZV NotIA (which contains ORF21) were added to 500 ng of ganglia DNA from uninfected cotton rats, and PCR was performed to generate a standard curve for estimating the copy number of latent viral DNA molecules. The PCR products were subjected to electrophoresis, and Southern blotting was performed using a radiolabeled probe to ORF21. Copy number was estimated by densitometry using a phosphorimager. The lower limit of detection was 10 copies of viral DNA when viral DNA was mixed with 500 ng of uninfected ganglia DNA.

RNA was isolated from cotton rat dorsal root ganglia after homogenization in Triazol (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, Calif.) following the manufacturer's protocol. The RNA was incubated with DNase I, heated to inactivate the DNase, and cDNA was prepared using reverse transcriptase with oligo(dT)12-18 as previously described (26). PCR was performed using primers TTCGTCCGATTCATAACGCG and GGTTTTGACTCGGACGAGTC to amplify a portion of the ORF63 gene, and after the reaction products were transferred to a nylon membrane, the blot was hybridized with a radiolabeled probe to ORF63.

RESULTS

VZV ORF63 is not required for replication in vitro.

To produce a virus in which both ORF63 and its duplicate gene (ORF70) were deleted, two independent cosmid clones MstIIA-63DA and MstIIA-63DB in which amino acids 24 to 268 of ORF63 and ORF70 had been deleted were constructed (Fig. 1). Transfection of melanoma cells with cosmids VZV NotIA, Not IBD, MstIIA, and MstIIB resulted in cytopathic effects (CPE) with production of a recombinant Oka (ROka) VZV 7 days after transfection. Transfecting cells with cosmids VZV NotIA, Not IBD, MstIIB, and either MstIIA-63DA or MstIIA-63DB resulted in CPE at 19 or 22 days after transfection, respectively. The resulting viruses were termed ROka63DA and ROka63DB, respectively.

A rescued virus, in which the two deletions in ROka63DA were repaired, was created by cotransfecting melanoma cells with ROka63DA virion DNA and a VZV fragment containing ORF63 with flanking regions. Eight days after transfection, CPE was observed. The resulting virus was passaged in melanoma cells, and after four rounds of plaque purification, full-length ORF63 viral DNA, but no residual ORF63 deletion mutant DNA could be detected by PCR (data not shown). An additional round of plaque purification was performed, and the resulting virus was termed ROka63DAR.

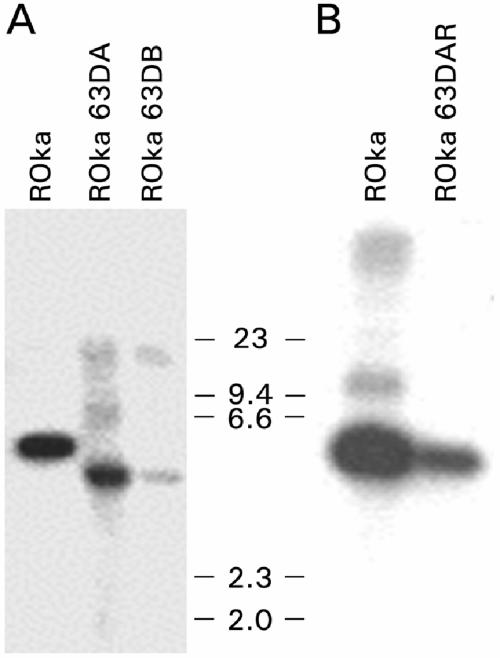

To verify that ROka63DA, ROka63DB, and ROka63DAR had the expected genome structures, Southern blotting was performed using virion DNAs. Digestion of viral DNA from VZV ROka or ROka63DAR with BamHI showed a 4.65-kb fragment, while digestion of ROka63A or ROka63B showed a 3.9-kb fragment (Fig. 2). Thus, the ORF63 deletion mutant and rescued viruses had the expected genome configurations. Nucleotide sequencing across the ORF63 deletion showed the expected sequence.

FIG. 2.

Southern blots of virion DNA from cells infected with parental virus (ROka) or viruses in which ORF63 was deleted. ROka, ROka63DA, and ROka63DB DNAs (A) or ROka and ROka63DAR DNAs (B) were digested with BamHI and hybridized to an ORF63 probe. The positions of markers showing the size of the DNA (in kilobase pairs) are indicated at the sides of the gels.

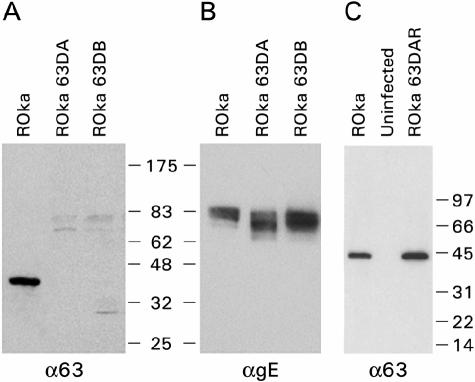

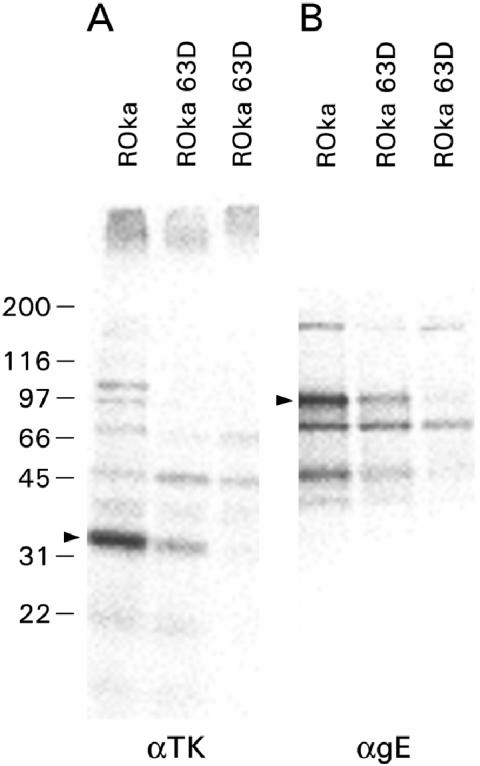

Immunoblotting was performed to confirm that ORF63 was not expressed in cells infected with mutant viruses in which ORF63 had been deleted. Lysates from cells infected with VZV ROka or ROka63DAR contained a 45-kDa ORF63 protein, while lysates from cells infected with ROka63DA or ROka63DB did not contain the protein (Fig. 3A and C). For a control, lysates from cells infected with ORF63 deletion mutant viruses were shown to express VZV gE (Fig. 3B). Therefore, cells infected with ORF63 deletion mutant viruses did not express the ORF63 protein.

FIG. 3.

Immunoblot of ORF63 expression in cells infected with recombinant VZV. A 45-kDa protein that reacts with antibody to ORF63 protein (α63) is present in cells infected with ROka and ROka63DAR, but not in cells infected with ROka63DA or ROka63DB (A and C). Bands of 70 to 90 kDa that react with antibody to VZV gE (αgE) are present in cells infected with VZV ROka, ROka63DA, and ROka63DB (B). Equivalent amounts of cell lysates were loaded for the cells infected with VZV mutants in which ORF63 had been deleted in panels A and B, but larger amounts of cell lysates were loaded for the cells infected with VZV mutants in which ORF63 had been deleted than for the cells infected with the parental virus. The positions of markers showing the sizes of proteins (in kilodaltons) are indicated to the right of the gels.

VZV in which ORF63 is deleted exhibits impaired growth in cell culture.

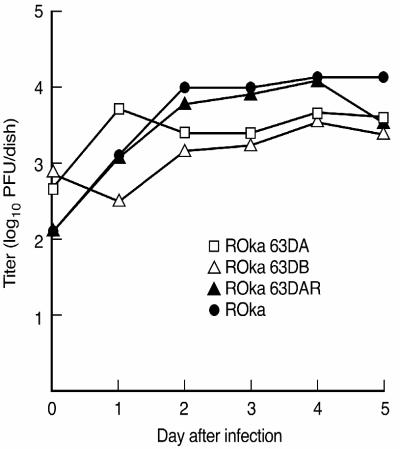

To determine whether the deletion of ORF63 affects the growth of the virus in cell culture, melanoma cells were infected with parental VZV, ORF63 deletion mutant viruses, or rescued virus, and viral titers were measured daily for 5 days. While the initial titers of VZV ROka63DA and ROka63DB were about 0.5 log units higher than that of VZV ROka, the peak titers of these viruses were about 0.5 log units lower than that of VZV ROka (Fig. 4). In contrast, ROka63DAR, in which the ORF63 deletions were repaired, grew to a titer similar to that of the parental virus. Thus, deletion of ORF63 impaired the growth of the virus in melanoma cells.

FIG. 4.

Growth in melanoma cells of parental VZV and mutant viruses in which ORF63 had been deleted. Cells were infected with the indicated viruses. Each day after infection, the cells were treated with trypsin, and the virus titer was determined.

ORF63 does not repress expression of putative early or late promoters during VZV infection in vitro.

Prior studies indicated that cotransfection of plasmids expressing ORF63 with reporter constructs resulted in repression of putative early gene expression in transient-expression assays (1, 8). Therefore, if ORF63 represses virus gene expression during virus infection, one might expect to see elevated levels of these viral proteins in cells infected with virus in which ORF63 had been deleted. To determine whether ORF63 expression during VZV infection results in inhibition of gene expression, we infected cells with parental virus or virus in which ORF63 had been deleted and performed immunoprecipitation using antibodies to putative early (VZV thymidine kinase) or late (gE) proteins. Cells were infected either with a higher titer of the ORF63 deletion mutant virus than of parental virus (Fig. 5A and B, leftmost ROka 63D lanes) that resulted in a similar level of CPE or with a titer of the deletion mutant virus that was equivalent to that of the parental virus (Fig. 5A and B, rightmost ROka 63D lanes). In either case, cells infected with VZV in which ORF63 had been deleted expressed less VZV thymidine kinase or gE than cells infected with parental virus. Thus, ORF63 protein does not repress expression of selected virus genes during VZV infection in vitro.

FIG. 5.

Expression of VZV thymidine kinase (A) and glycoprotein E (B) proteins in cells infected with parental VZV or virus in which ORF63 had been deleted. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with antibody to thymidine kinase (αTK) or to glycoprotein E (αgE). The positions of VZV thymidine kinase (35 kDa) and glycoprotein E (gE) (95 kDa) are indicated by the arrowheads. The positions of markers showing the sizes of proteins (in kilodaltons) are indicated to the left of the gels.

VZV ORF63 is critical for latent infection.

To determine whether ORF63 is important for VZV latency, cotton rats were inoculated intramuscularly with parental virus or virus in which ORF63 had been deleted. Five to 6 weeks later, the animals were sacrificed, and dorsal root ganglia were pooled. DNA was isolated from the ganglia, and PCR was performed, followed by Southern blotting, to determine VZV genome copy numbers in latently infected ganglia.

Pooled data from the first two independent experiments (Table 1, experiments 1 and 2) showed that VZV DNA was present in ganglia from 12 of 25 animals (48%) inoculated with VZV ROka and 2 of 24 animals (8%) infected with ROka63DA. To verify that the ORF63 deletion mutant virus did not have other mutations that would affect latency, cotton rats were inoculated with VZV ROka63DA and ROka63DAR, in which the deletion has been rescued. When results of two separate experiments were pooled (Table 1, experiments 3 and 4), significantly fewer animals infected with ROka63DA (7 of 20 [35%]) had latent virus in dorsal root ganglia compared with those infected with ROka63DAR (19 of 20 [95%]).

TABLE 1.

Number of animals with ganglia infected with VZVa

| Expt | Time after infection | No. of animals positive for VZV DNA/total no. of animals (%)

|

Mean copy no.b

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ROka63DA | ROka63DAR | ROka | ROk63DA | ROka or ROka63DAR | ||

| 1 | 6 wk | 0/10 (0) | NDc | 4/13 (31) | <10 | 48 |

| 2 | 6 wk | 2/14 (14) | ND | 8/12 (67) | 323 | 95 |

| Total | 2/24 (8)d | 12/25 (48) | ||||

| 3 | 6 wk | 3/12 (25) | 11/12 (92) | ND | 17 | 66 |

| 4 | 5 wk | 4/8 (50) | 8/8 (100) | ND | 71 | 813 |

| Total | 7/20 (35)d | 19/20 (95) | ||||

| 5 | 3 days | 9/9 (100) | 9/9 (100) | ND | >104 | >104 |

| 6 | 3 days | 9/9 (100) | 9/9 (100) | ND | >104 | >104 |

| Total | 18/18 (100) | 18/18 (100) | ||||

| 7 | 6 days | 2/6 (33) | 5/5 (100) | ND | 174 | 182 |

| 8 | 6 days | 2/7 (29) | 7/7 (100) | ND | 26 | 200 |

| Total | 4/13 (31)d | 12/12 (100) | ||||

| 9 | 10 days | 2/7 (29) | 4/4 (100) | ND | 95 | 63 |

| 10 | 10 days | 0/8 (0) | 7/7 (100) | ND | <10 | 129 |

| Total | 2/15 (13)d | 11/11 (100) | ||||

Animals were inoculated with 1.75 × 105 PFU in 50 μl at each site along the spine for 12 injections per animal in all experiments, except in experiment 2, where the titer was 3.0 × 105 PFU at each site.

Mean for the ganglia that were positive by PCR.

ND, not done.

The number of animals positive for ROka63DA VZV DNA was significantly different (P ≤ 0.001 by Wilcoxon two-sample test) from the number of animals positive for ROka or ROka63DAR VZV DNA.

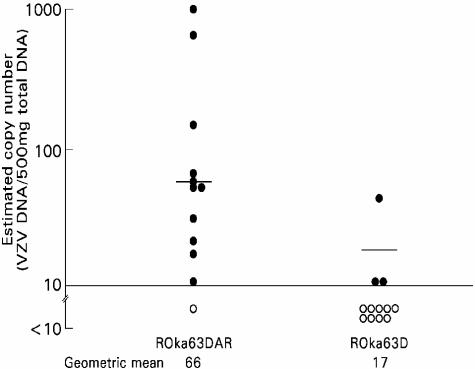

In experiment 3, animals inoculated with ROka63DAR with VZV PCR-positive ganglia had a geometric mean copy number of 66 VZV genomes, while animals inoculated with VZV ROka63DA with VZV PCR-positive ganglia had a geometric mean of 17 viral genomes (P = 0.0002) (Fig. 6). In experiment 4, the geometric mean copy numbers were 813 VZV genomes in animals infected with ROka63DAR with PCR-positive ganglia and 71 genomes for animals inoculated with VZV ROka63DA (P = 0.003). Thus, animals inoculated with the ORF63 mutant virus generally had lower mean copy numbers of latent VZV genomes in the dorsal root ganglia, and the frequency of latently infected animals was significantly lower than animals infected with virus in which the ORF63 deletion had been rescued.

FIG. 6.

Estimated copy number of VZV genomes in latently infected cotton rat ganglia from experiment 3 (Table 1). The geometric mean number of VZV genome copies per 500 ng of ganglia DNA in PCR-positive ganglia is shown at the bottom of the figure. Filled circles show the viral copy numbers for samples that exceeded the limit of detection (≥10 copies per 500 ng of DNA), while open circles represent samples whose copy numbers were below the limit of detection.

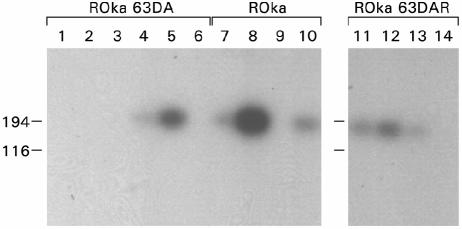

To determine whether ORF63 transcripts were expressed during latency, RNA was isolated from thoracic and lumbar ganglia on the left side of the spine from latently infected animals whose right dorsal root ganglia were positive for ORF21 DNA. cDNA was prepared from the RNA, and PCR was performed using one primer corresponding to the 5′ nontranslated region of ORF63 and another primer complementary to codons 11 to 16 of ORF63. Therefore, the portion of ORF63 amplified by PCR lies outside the region deleted from ROka63DA. Two of six animals infected with ROka63DA, three of four animals infected with ROka, and three of four animals infected with ROka63DAR expressed transcripts containing a portion of the ORF63 gene during latency (Fig. 7). Thus, some of the animals infected with the ORF63 deletion mutant expressed transcripts from the 5′ end of the gene during latency.

FIG. 7.

RNA transcripts corresponding to the 5′ end of ORF63 are expressed in animals latently infected with ROka63DA, ROka, and ROka63DAR. RNA was isolated from dorsal root ganglia, cDNA was prepared, and PCR was performed, followed by Southern blotting for ORF63. ORF63 transcripts were detected in animals 4 and 5 infected with ROka63DA, animals 7, 8, and 10 infected with ROka, and animals 11, 12, and 13 infected with ROka63DAR. The positions of markers showing the size of DNA (in base pairs) are indicated to the left of the gels.

VZV ORF63 is not essential for acute infection of dorsal root ganglia.

To determine whether the impairment in latent infection with ORF63 is due to reduced acute infection of ganglia or impaired persistence in the ganglia, cotton rats were infected with virus in which ORF63 had been deleted or virus in which the ORF63 deletion had been rescued, and dorsal root ganglia were obtained at early times after infection. All animals infected with the virus in which the ORF63 deletion had been rescued had viral DNA in their ganglia at days 3, 6, and 10 days after infection (Table 1, experiments 5 to 10). While all animals infected with the ORF63 deletion mutant had viral DNA in their ganglia at day 3 with high levels of VZV DNA (geometric mean copy numbers of >104 VZV genomes), the numbers of latently infected animals infected with ROka63DA and the mean copy numbers declined markedly by days 6 and 10 compared with day 3. Data from two independent experiments showed that at day 6, 31% (4 of 13) of animals inoculated with ROka63DA had VZV DNA in their ganglia (Table 1, experiments 7 and 8), while at day 10 only 13% (2 of 15) of animals inoculated with the deletion mutant had viral DNA in their ganglia (Table 1, experiments 9 and 10). Thus, VZV in which ORF63 had been deleted could enter ganglia early (3 days) after inoculation, resulting in high levels of VZV DNA in the ganglia; however, by 6 days after infection, the level of infection was already much lower for the ORF63 mutant virus than for the parental virus.

DISCUSSION

ORF63 is the first VZV gene shown to have a critical role for establishment of latent infection. Prior studies showed that several VZV genes (ORF1, ORF2, ORF10, ORF13, ORF17, ORF21, ORF32, ORF47, ORF57, ORF61, and ORF66 [26-29, 35]) are dispensable for latency. Virus in which ORF63 had been deleted exhibited impaired growth in cell culture; however, it is unlikely that this explains its marked impairment in establishing latency. First, virus with a deletion of ORF21 that is unable to grow in cell culture is still able to establish a latent infection at a frequency similar to that of parental virus (35). Second, VZV mutants with a deletion of ORF17 and ORF61 that show impaired growth in vitro similar to that of the ORF63 mutant virus do not show impaired ability to establish latency (26, 28).

A prior study suggested that ORF63 was required for replication in cell culture (32). These researchers used a different set of cosmids than those used in our study to make recombinant VZV. While they were able to construct a virus in which one copy of ORF63 or ORF70 (the duplicate gene in the other repeat region) had been deleted, they were unable to obtain a virus in which both of the genes had been deleted. Analysis of viral DNA from cells infected with virus in which a single copy of ORF63 (or its duplicate gene [ORF70]) had been deleted showed aberrant VZV DNA sequences that were not present in the cosmids used to make the viruses. These abnormalities suggest that some rearrangements occurred during replication of the virus; such rearrangements may have interfered with the ability to obtain a virus with a combined ORF63 and ORF70 deletion and to replicate. We verified the structure of our double deletion mutant by Southern blotting (Fig. 2), by PCR analysis of DNA across the deletion in ORF63 and ORF70 (J. I. Cohen and T. Krogmann, unpublished data), and by sequencing the region that spanned the deletions in ORF63 and ORF70 (Cohen and Krogmann, unpublished). These analyses combined with the immunoblot showing that ORF63 is not expressed (Fig. 3) indicate that the virus we constructed lacked ORF63 (and its duplicate gene, ORF70).

VZV in which ORF63 had been deleted exhibited impaired replication in cell culture. The ORF63 protein coimmunoprecipitates with the ORF62 protein (32), and a fraction of the ORF63 protein colocalizes with the ORF62 protein in virus-infected cells (19). The site where the ORF63 protein binds to the ORF62 protein overlaps with the region of the latter that interacts with basal transcription factors (TBP, TFIIB) and with DNA. The interaction between the ORF63 and ORF62 proteins may be important for virus replication. ORF62 encodes an immediate-early protein that is the major viral transactivator and is present in the virus tegument (12). ORF63 enhances the ability of ORF62 to transactivate the viral DNA polymerase and glycoprotein I promoters (19). Thus, the absence of ORF63 may reduce expression of putative early and late viral proteins.

VZV in which ORF63 had been deleted was able to enter ganglia early in infection (day 3) but showed increasing impairment in persistence at later time points (days 6 and 10 and 5 to 6 weeks) after infection. Multiple steps are required for establishing VZV latency. The virus must enter the nerve ending, be transported up the axon, enter the ganglia, persist in the ganglia during acute infection, and establish a latent infection. Three days after infection, 100% of animals inoculated with the ORF63 deletion mutant had VZV DNA in their ganglia; this number dropped to <40% by day 6 after infection and remained low for all times tested thereafter. In contrast, more than 90% of animals infected with virus in which the ORF63 deletion had been rescued had viral DNA in ganglia at each of these time points. Thus, ORF63 does not appear to be critical for transport of the virus to ganglia or entry into the ganglia (neuroinvasiveness) but instead is critical for persistence during acute infection and establishment of latency. While expression of the ORF63 protein in the absence of other viral proteins resulted in repression of early gene expression in transient-expression assays (1) and this might serve as a mechanism for its role in latency, the absence of ORF63 in the deletion mutant did not result in increased expression of putative early or late genes. Thus, ORF63 presumably has another role(s) in latency.

ORF63 is one of the most abundant VZV genes expressed during latency and the first VZV gene shown to be critical for establishment of latent infection. We showed that two other genes expressed during latency, ORF21 (4, 18) and ORF66 (3) are dispensable for latency (29, 35). In contrast to VZV, which expresses at least six viral genes during latency, herpes simplex virus (HSV) expresses only the latency-associated transcripts (LATs) in latently infected ganglia. In most studies, HSVs with LAT deletions did not have impaired ability to establish latency (9, 15, 16, 33). While an HSV-1 LAT null mutant resulted in extensive apoptosis in acutely infected ganglia (23), we did not observe an increase in apoptosis in ganglia acutely infected with VZV in which ORF63 had been deleted compared to virus in which the ORF63 deletion had been rescued (J. I. Cohen, unpublished data). ORF63 has limited homology with its HSV homolog, ICP22. HSV with ICP22 deleted established latency in the dorsal root ganglia of guinea pigs, but its ability to reactivate by explant cocultivation in cell culture was impaired (24). Therefore, the role of ORF63 in VZV latency is different from the roles of LATs or ICP22 in HSV latency.

The cotton rat model, like other small animal models of VZV, has limitations in that the animals do not develop acute disease and that reactivation has not been demonstrated. It is possible that reactivation might occur, but the absence of clinical disease limits the ability to detect reactivation. Similarly, reactivation has not been demonstrated for explanted human ganglia that are latently infected with VZV. In contrast, reactivation of HSV has been demonstrated both in small animal models and in ganglia explanted from latently infected animals and humans. Thus, it is possible that the inability to demonstrate reactivation of VZV in rodents may be due both to the nature of the virus itself and to properties of the animal model.

The live attenuated VZV vaccine currently licensed is effective for prevention of chickenpox; however, the virus vaccine establishes a latent infection and can reactivate and cause zoster (30, 34). One recent case was severe (17). It is uncertain how often similar cases will occur in the future. As the only approved VZV vaccine licensed at this time establishes a latent infection and can reactivate, this vaccine has a theoretical advantage in boosting immune responses through asymptomatic reactivation, but it is not certain that this occurs clinically or is immunologically significant. Second-generation vaccines that are unable to establish latency, such as glycoprotein subunit vaccines, have been proposed; however, there have been concerns about their efficacy. A live VZV vaccine in which ORF63 has been deleted could have advantages over the present vaccine, in that it might induce the strong immune responses associated with the live Oka vaccine strain but should be less likely to establish latency and therefore to reactivate and cause herpes zoster. Such a vaccine might also be useful to deliver other viral antigens to the immune system (7, 31). Deletion of nearly the entire ORF63 gene markedly reduced latent infection, but the mutant virus grew to a peak titer that was lower than that of the parental virus. At present, we are constructing other ORF63 mutants to determine whether other ORF63 deletion viruses can replicate and express viral proteins at levels comparable to that of parental virus yet still show impaired ability to establish latency and therefore be less likely to cause zoster.

Acknowledgments

We thank Paul Kinchington for antibody to ORF63, Christine Talarico for antibody to thymidine kinase, Mark VanRaden for statistical analyses, and Stephen Straus for reviewing the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bontems, S., E. Di Valentin, L. Baudoux, B. Rentier, C. Sadzot-Delvaux, and J. Piette. 2002. Phosphorylation of varicella-zoster virus IE63 protein by casein kinase influences its cellular localization and gene regulation activity. J. Biol. Chem. 277:21050-21060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brunell, P. A., L. C. Ren, J. I. Cohen, and S. E. Straus. 1999. Viral gene expression in rat trigeminal ganglia following neonatal infection with varicella-zoster virus. J. Med. Virol. 58:286-290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cohrs, R. J., D. H. Gilden, P. R. Kinchington, E. Grinfeld, and P. G. E. Kennedy. 2003. Varicella-zoster virus gene 66 transcription and translation in latently infected human ganglia. J. Virol. 77:6660-6665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cohrs, R. J., J. Randall, J. Smith, D. H. Gilden, C. Dabrowski, H. van der Keyl, and R. Tal-Singer. 2000. Analysis of individual human trigeminal ganglia for latent herpes simplex virus type 1 and varicella-zoster virus nucleic acids using real-time PCR. J. Virol. 74:11464-11471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davison, A. J., and J. Scott. 1986. The complete DNA sequence of varicella-zoster virus. J. Gen. Virol. 67:1759-1816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Debrus, S., C. Sadzot-Delvaux, A. F. Nikkels, J. Piette, and B. Rentier. 1995. Varicella-zoster virus gene 63 encodes an immediate-early protein that is abundantly expressed during latency. J. Virol. 69:3240-3245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Heineman, T. C., L. Pesnicak, M. Ali, T. Krogmann, N. Krudwig, and J. I. Cohen. 2004. Varicella-zoster virus expressing HSV-2 glycoproteins B and D induces protection against HSV-2 challenge. Vaccine 22:2558-2565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jackers, P., P. Defechereux, L. Baudoux, C. Lambert, M. Massaer, M.-P. Merville-Louis, B. Rentier, and J. Piette. 1992. Characterization of regulatory functions of varicella-zoster virus gene 63-encoded protein. J. Virol. 66:3899-3903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Javier, R. T., J. G. Stevens, V. B. Dissette, and E. K. Wagner. 1988. A herpes simplex virus transcript abundant in latently infected neurons is dispensable for establishment of the latent state. Virology 166:254-257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kennedy, P. G. E., E. Grinfeld, and J. E. Bell. 2000. Varicella-zoster virus gene expression in latently infected and explanted human ganglia. J. Virol. 74:11893-11898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kennedy, P. G. E., E. Grinfeld, S. Bontems, and C. Sadzot-Delvaux. 2001. Varicella-zoster virus gene expression in latently infected rat dorsal root ganglia. Virology 289:218-223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kinchington, P. R., and J. I. Cohen. 2000. Viral proteins, p. 74-104. In A. Gershon and A. M. Arvin (ed.), Varicella-zoster virus. Cambridge Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom.

- 13.Kinchington, P. R., D. Bookey, and S. E. Turse. 1995. The transcriptional regulatory proteins encoded by varicella-zoster virus open reading frames (ORFs) 4 and 63, but not ORF 61 are associated with purified virus particles. J. Virol. 69:4274-4282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kost, R. G., H. Kupinsky, and S. E. Straus. 1995. Varicella-zoster virus gene 63: transcript mapping and regulatory activity. Virology 209:218-224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Krause, P. R., L. R. Stanberry, N. Bourne, B. Connelly, J. F. Kurawadwala, A. Patel, and S. E. Straus. 1995. Expression of the herpes simplex virus type 2 latency-associated transcript enhances spontaneous reactivation of genital herpes in latently infected guinea pigs. J. Exp. Med. 181:297-306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leib, D. A., C. L. Bogard, M. Kosz-Vnenchak, K. A. Hicks, D. M. Coen, D. M. Knipe, and P. A. Schaffer. 1989. A deletion mutant of the latency-associated transcript of herpes simplex virus type 1 reactivates from the latent state with reduced frequency. J. Virol. 63:2893-2900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Levin, M. J., K. M. Dahl, A. Weinberg, R. Giller, A. Patel, and P. R. Krause. 2003. Development of resistance to acyclovir during chronic infection with the Oka vaccine strain of varicella-zoster virus in an immunosuppressed child. J. Infect. Dis. 188:954-959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lungu, O., C. A. Panagiotidis, P. W. Annunziato, A. A. Gershon, and S. J. Silverstein. 1998. Aberrant intracellular localization of varicella-zoster virus regulatory proteins during latency. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:7080-7085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lynch, J. M., T. K. Kenyon, C. Grose, J. Hay, and W. T. Ruychen. 2002. Physical and functional interaction between the varicella-zoster virus IE63 and IE62 proteins. Virology 302:71-82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mahalingam, R., M. Wellish, R. Cohrs, S. Debrus, J. Piette, B. Rentier, and D. H. Gilden. 1996. Expression of protein encoded by varicella-zoster virus open reading frame 63 in latently infected human ganglionic neurons. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93:2122-2124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Meier, J. L., R. P. Holman, K. D. Croen, J. E. Smialek, and S. E. Straus. 1993. Varicella-zoster virus transcription in human trigeminal ganglia. Virology 193:193-200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ng, T. I., L. Keenan, P. R. Kinchington, and C. Grose. 1994. Phosphorylation of varicella-zoster virus open reading frame (ORF) 62 regulatory product by viral ORF 47-associated protein kinase. J. Virol. 68:1350-1359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Perng, G. C., C. Jones, J. Ciacci-Zanella, M. Stone, G. Henderson, A. Yukht, S. M. Slanina, F. M. Hofman, H. Ghiasi, A. B. Nesburn, and S. L. Wechsler. 2000. Virus-induced neuronal apoptosis blocked by the herpes simplex virus latency-associated transcript. Science 287:1500-1503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Poffenberger, K. L., A. D. Idowu, E. B. Fraser-Smith, P. E. Raichlen, and R. C. Herman. 1994. A herpes simplex virus type 1 ICP22 deletion mutant is altered for virulence and latency in vitro. Arch. Virol. 139:111-119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sadzot-Delvaux, C., S. Debrus, A. Nikkels, J. Piette, and B. Rentier. 1995. Varicella-zoster virus latency in the adult rat is a useful model for human latent infection. Neurology 45(Suppl. 8):S18-S20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sato, H., L. D. Callanan, L. Pesnicak, T. Krogmann, and J. I. Cohen. 2002. Varicella-zoster virus (VZV) ORF17 protein induces RNA cleavage and is critical for replication of VZV at 37oC but not 33oC. J. Virol. 76:11012-11023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sato, H., L. Pesnicak, and J. I. Cohen. 2002. Varicella-zoster virus open reading frame 2 encodes a membrane phosphoprotein that is dispensable for viral replication and for establishment of latency. J. Virol. 76:3575-3578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sato, H., L. Pesnicak, and J. I. Cohen. 2003. Use of a rodent model to show that varicella-zoster virus ORF61 is dispensable for establishment of latency. J. Med. Virol. 70(Suppl. 1):S79-S81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sato, H., L. Pesnicak, and J. I. Cohen. 2003. Varicella-zoster virus ORF47 protein kinase, which is required for replication in human T cells, and ORF66 protein kinase, which is expressed during latency, are dispensable for establishment of latency. J. Virol. 77:11180-11185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sharrar, R. G., P. LaRussa, S. A. Steinberg, S. P. Steinberg, A. R. Sweet, R. M. Keatley, M. E. Wells, W. P. Stephenson, and A. A. Gershon. 2000. The postmarketing safety profile of varicella vaccine. Vaccine 19:916-923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shiraki, K., H. Sato, Y. Yoshida, J. I. Yamamura, M. Tsurita, M. Kurokawa, and S. Kageyma. 2001. Construction of Oka varicella vaccine expressing human immunodeficiency virus env antigen. J. Med. Virol. 64:89-95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sommers, M., E. Zagha, O. K. Serrano, C. C. Ku, L. Zerboni, A. Baiker, R. Santos, M. Spengler, J. Lynch, C. Grose, W. Ruyechan, J. Hay, and A. M. Arvin. 2001. Mutational analysis of the repeated open reading frames, ORFs 63 and 70 and ORFs 64 and 69, of varicella-zoster virus. J. Virol. 75:8224-8239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Steiner, I., J. G. Spivack, R. P. Lirette, S. M. Brown, A. R. MacLean, J. H. Subak-Sharpe, and N. W. Fraser. 1989. Herpes simplex virus type 1 latency-associated transcripts are evidently not essential for latent infection. EMBO J. 8:505-511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wise, R. P., M. E. Salive, M. M. Braunn, G. T. Mootrey, J. F. Seward, L. G. Rider, and P. R. Krause. 2000. Postlicensure safety surveillance for varicella vaccine. JAMA 284:1271-1279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xia, D., S. Srinivas, H. Sato, L. Pesnicak, S. E. Straus, and J. I. Cohen. 2003. Varicella-zoster virus ORF21, which is expressed during latency, is essential for virus replication but dispensable for establishment of latency. J. Virol. 77:1211-1218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]