Abstract

The vertebrate visual photoreceptor rhodopsin (Rho) is a unique G protein-coupled receptor as it utilizes a covalently tethered inverse agonist (11-cis-retinal) as the native ligand. Previously, electrophysiological studies showed that ligand binding of 11-cis-retinal in dark-adapted Rho was essentially irreversible with a half-life estimated to be 420 years, until after thermal isomerization to all-trans-retinal, which then slowly dissociates. This long lifetime of 11-cis-retinal binding was considered to be physiologically important for minimizing background signal (dark noise) of the visual system. However, in vitro biochemical studies on the thermal stability of Rho showed that Rho decays with a half-life on the order of days. In this study, we resolve the discrepancy by measuring the chromophore exchange rate of the bound 11-cis-retinal chromophore with free 9-cis-retinal from Rho in an in vitro phospholipid/detergent bicelle system. We conclude that the thermal decay of Rho primarily proceeds through spontaneous breaking of the covalent linkage between opsin and 11-cis-retinal, which was overlooked in the electrophysiological recording. We estimate that this slow spontaneous release of 11-cis-retinal from Rho should result in 104 to 105 free opsin molecules in a dark-adapted rod cell—a number that is three orders of magnitude higher than previously expected. We also discuss the physiological implications of these findings on the basal activity of opsins and the associated dark noise in the visual system.

Introduction

The vertebrate visual system has two main classes of photoreceptor pigments: cone opsins for bright-light (photopic) vision, and rhodopsin (Rho) for dim-light (scotopic) vision. Cone photopigments and Rho are all G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) comprised of a heptahelical transmembrane apoprotein opsin and a chromophore, 11-cis-retinal (the bound chromophore is 6-s-cis-11-cis-retinylidene, 11CR). In the dark state, opsin and 11CR are covalently linked together through a protonated Schiff base (PSB) bond. Upon photoactivation, 11CR absorbs a photon to isomerize to all-trans-retinal (ATR, 6-s-cis-11-trans-retinylidene), triggering a series of conformational changes eventually culminating in the formation of the metarhodopsin II (Meta-II) state that is able to activate a heterotrimeric G protein (transducin) to allow downstream signaling. The decay of Meta-II is accompanied by the hydrolysis of the Schiff base and subsequent dissociation of ATR from its binding pocket (1). A previous fluorescence study showed that the Meta-II species has a decay half-time of 2.3 min at 37°C (2).

11CR is an inverse agonist that minimizes the basal activity of photoreceptors. For cone receptors, 11CR has a finite binding lifetime, and the spontaneous breaking of the PSB bond has been reported (3). In contrast, 11CR binding to Rho has been considered essentially irreversible. The covalent linkage between 11CR and opsin ensures that the ligand-receptor complex has a long lifetime in the inactive state until it absorbs a photon. Electrophysiological studies have suggested that dark-adapted Rho decays as a result of the thermal isomerization of 11CR to ATR (4, 5). These rare thermal events occur with a half-time of 420 years (5). This exceptional stability of dark-state Rho is thought to be a primary factor underlying the excellent photosensitivity of the rod system (6). In contrast, an in vivo radioactive labeling study on dark-adapted mouse retina showed that the rate of chromophore turnover in Rho was 1.8 × 10−7 s−1, or a half-life of 45 days (7). However, this value was derived from a single temperature, which makes comparison with other thermally activated processes difficult, and the experiments could not definitely distinguish between de novo pigment synthesis and chromophore exchange within the existing pigment. Moreover, all these in vivo data are at odds with the in vitro biochemical measurements, which found that the thermal decay rates of Rho at physiological temperature is on the order of 10−6 s−1 (8, 9).

In our study, we revisited the stability of dark-state Rho by measuring the exchange rate of bound 11CR with free 9-cis-retinal (9CR) in Rho reconstituted into detergent/lipid bicelles. We found that the rate of the light-independent chromophore dissociation at 37°C was 2.2 × 10−7 s−1, corresponding to a half-time of 36 days. This dissociation rate and the activation energy are distinct from the earlier biochemical data that measured the denaturation rate of Rho and opsin in vitro (8, 9, 10), and from the electrophysiological studies that measured thermal activation of single Rho molecules in native disc membranes (4, 5). We conclude that the direct breaking of the PSB bond gave rise to the observed chromophore release. Our data also suggested that the chromophore turnover rate obtained from the radioactive labeling study (7) was primarily attributable to spontaneous release of retinal from dark-state Rho molecules, rather than de novo protein synthesis. Thus both rod photoreceptors and cone receptors spontaneously release their chromophore at physiological temperature. We estimate the resulting number of free opsin molecules in a dark-adapted rod cell to be in the range of 104 to 105, which is three orders of magnitude higher than previously thought. Finally, we discuss the physiological implications of our findings for rod cell signaling.

Materials and Methods

Materials

1D4-Sepharose 2B was prepared from 1D4 mAb and cyanogen bromide-activated Sepharose 2B (2 mg IgG per ml packed beads). n-dodecyl-β-d-maltoside (DM) and 3-((3-cholamidopropyl)dimethylammonio)-1-propanesulfonate (CHAPS) in the highest purity grade were obtained from Anatrace (Maumee, OH). 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (POPC) was obtained from Avanti (Avanti Polar Lipids, Alabaster, AL). 9CR was obtained from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). 11-cis-retinal was a gift from Drs. P. Sorter and V. Toome at Hoffmann-La Roche. In this study, we utilized Rho and opsin purified from bovine rod outer segment (ROS). The detailed methods for preparing these samples are given in the Supporting Material.

The measurement of retinal binding kinetics based on quenching of Trp

Fluorescence spectroscopy was performed at 28°C on a SPEX Fluorolog tau-311 spectrofluorometer (Horiba, Edison, NJ) in photon-counting mode. The excitation wavelength was 295 nm with a 0.6-nm band-pass, and the emission was measured at with the monochromator set to 330 nm with a 15-nm band-pass and an additional Hoya UG-340 UV band-pass filter. The signal was sampled every 30 s with 2 s integration time. The excitation beam was closed between integrations to minimize photobleaching. The concentration of Rho purified in 0.1% DM micelles was typically 0.25–0.30 μm. The time course experiments were done by adding aliquots of the elution samples from receptors (30 μl) to the POPC/CHAPS bicelle buffer A (1% (weight/volume) POPC, 1% (w/v) CHAPS, 125 mm KCl, 25 mm MES, 25 mm HEPES, 12.5 mm KOH (pH 6.0), 450 μl) under constant stirring. The 11CR or 9CR ethanolic stock solution was diluted in the POPC/CHAPS bicelle buffer, and 20 μl of this working dilution was added to the cuvette to give a desired final concentration (typically ∼1.5 to 2.0 μm). The sample was constantly stirred to facilitate mixing. For each measurement, the concentrations of freshly diluted retinoids were determined from their absorption maxima (ε378 nm = 25,600 m−1 s−1 for 11CR and ε374 nm = 36,200 m−1 s−1 for 9CR). The decrease of Trp fluorescence was fitted with a pseudo first-order exponential decay model to derive the apparent regeneration rate (kobs). The second-order rate constant (k2) for the binding between opsin and retinal was calculated as k2 = kobs/[retinal].

The chromophore exchange of ROS Rho

Lectin-affinity purified ROS Rho was exchanged by gel filtration into the POPC/CHAPS bicelle buffer B (1% (w/v) POPC, and 1% (w/v) CHAPS, 137.5 mm NaCl, 0.25 mm EDTA, 25 mm MES, 25 mm HEPES hemisodium salt (pH 6.0)). The samples (5.3 μm Rho) were supplemented with the 9CR (49 μm) and incubated in the dark for 106, 2 × 106, and 3 × 106 s (11.6, 23.2, and 34.8 days) at three different temperatures (28°C, 36°C, and 44°C). The samples were then purified using 1D4-sepharose resin and characterized by UV-Vis spectroscopy. The dark-state absorption spectra (dark spectra) of Rho samples supplemented with 50 mm hydroxylamine were recorded in a 50-μl microcuvette with 10-mm path length on a Lambda-800 spectrophotometer (PerkinElmer Life Sciences, Waltham, MA). To acquire the absorption spectra of the photobleached Rho (light spectra), the sample was irradiated for 30 s with a 335-mW 505-nm LED light source (Thorlabs, Newton, NJ) placed on top of the cuvette. First, the dark and light spectra were corrected for baseline offsets by subtracting a constant to give zero absorbance at 650 nm. Second, the dark-light difference spectra were obtained by subtracting the offset-corrected dark and light spectra. Third, the difference spectra were normalized to –1 absorbance units at 365 nm. Fourth, the double-difference spectra were obtained by subtracting the normalized difference spectra of the Rho-isoRho mixtures from the normalized difference spectrum of pure Rho. Last, the extent of chromophore exchange was calculated by ratio of the amplitude of the double-difference spectra of the exchanged sample with the amplitude of a double-difference spectrum obtained from pure isoRho and Rho. For more details of the chromophore exchange procedures see the Supporting Material.

Results

Rationale of using chromophore exchange to quantifying 11CR dissociation

Our aim in this study is to measure the spontaneous dissociation of 11CR from Rho, without previous activation by light or heat. A major challenge is how to quantify the fraction of newly formed free opsin resulting from 11CR dissociation. Since Rho and opsin share identical primary sequence and similar tertiary structures (11, 12), no immunopurification method would separate them. Moreover, the ligand-binding pocket of opsin is enclosed by the heptahelical scaffold, making it impossible to develop a ligand-affinity chromatography method. In principle, Rho and opsin can be spectrophotometrically resolved, as opsin lacks the 500-nm absorption peak that is characteristic for Rho. However, the dissociation constant (Kd) is so small that at equilibrium it is impossible to reliably quantify the amount of free opsin whose concentration must be orders of magnitude lower than that of Rho in equilibrium. Moreover, unliganded opsin is less thermally stable than rhodopsin and it has a propensity to denature and precipitate (13), further increasing the likelihood of underestimating the amount of opsin.

We propose to use the in vitro chromophore exchange rate of the bound 11CR with free 9CR to approximate the dissociation rate of 11CR (Fig. 1). Free opsin can also form a PSB linkage with 9CR to give a recombinant product termed isorhodopsin (isoRho). Compared with Rho, isoRho has its absorbance maximum shifted from 500 to 487 nm (14), thus providing an optical read-out. 11CR and 9CR occupy the same ligand-binding pocket (Fig. 1 A) (15, 16). Therefore, dissociation of 11CR from the ligand-binding pocket is a prerequisite for subsequent 9CR binding. Similar to 11CR, 9CR enhances the thermal stability of the receptor, thereby preventing the loss of opsin following 11CR dissociation. We envision that incubating Rho with 9CR would drive forward the dissociation equilibrium of 11CR from Rho, resulting in slow but appreciable conversion of Rho to isoRho, which can then be spectrophotometrically determined.

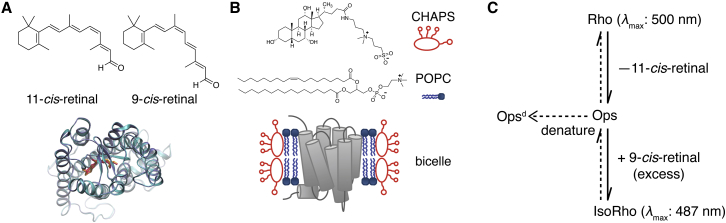

Figure 1.

Scheme for measuring chromophore exchange in rhodopsin. (A) Superimposition of the structure of Rho (PDB: 1U19, cyan) (15) and isoRho (PDB: 2PED, ice blue) (16) shows 11-cis-retinal (11CR, orange) and 9-cis-retinal (9CR, red) occupy the same ligand binding pocket in opsin. Chemical isomer structures are shown above. (B) The structures of CHAPS and POPC and a cartoon of Rho reconstituted in a POPC/CHAPS bicelle are shown. (C) The spontaneous dissociation of 11CR from Rho forms opsin, which gets trapped by 9CR to form isoRho, or less likely, denatures irreversibly. To see this figure in color, go online.

Kinetics of retinal binding with opsin

An important question in this experimental scheme is whether 9CR would effectively compete with 11CR in binding to opsin. 11CR dissociation from Rho would produce free 11CR in the system. If the binding between 9CR and opsin is significantly slower than that between 11CR and opsin, then the reassociation of 11CR and opsin may not be negligible. We employed a fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET)-based assay to measure the binding kinetics of 11CR and 9CR with opsin (Fig. 2). The dark-state Rho exhibits a distinct 500-nm absorption peak due to the PSB linkage between opsin and 11CR, as well as a less-intense 350-nm peak. In dark-state Rho, energy transfer between Trp residues and 11CR results in ∼80% quenching of the Trp fluorescence (Fig. 2 A) (2). Photoisomerization of 11CR to ATR converts the inactive Rho to the active Meta-II species with a deprotonated Schiff base, and the retinal absorption peak correspondingly shifts from 500 to 380 nm. At the Meta-II state, the spectral overlap of the Trp emission and retinal absorption spectrum is greater, leading to even higher quenching efficiency as compared with the dark state (Fig. 2 B) (2). When ATR is released from the binding pocket, there is essentially no spectral overlap of the absorption spectrum of opsin apoprotein and the Trp emission spectrum, and the energy transfer between retinal and the Trp residues of opsin is completely lost (Fig. 2 C). Therefore, the energy transfer between retinal and the Trp residues in opsin can be utilized as a reporter for retinal entry or release from the ligand-binding site (2).

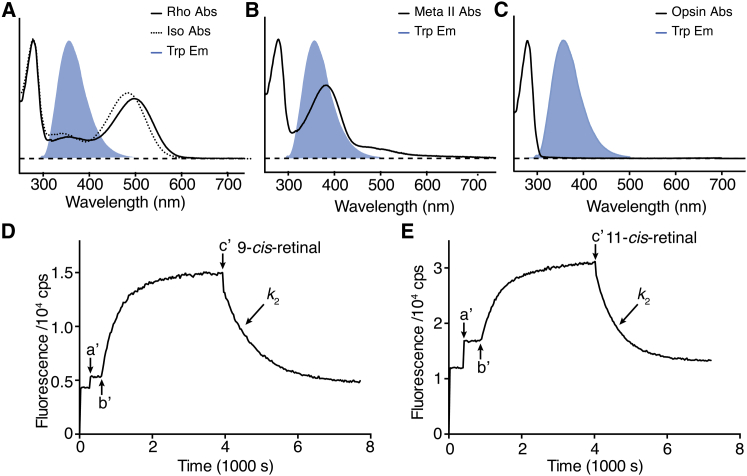

Figure 2.

Measurement of the binding kinetics between opsin and retinals. The absorption spectra of Rho and isoRho (A), Meta-II state (B), and opsin (C) are overlaid with the fluorescence emission peaks of Trp (blue, maximum at 330 nm). The spectra are normalized to the intensities of the absorption and fluorescence emission peaks. (D and E) Tryptophan fluorescence time course traces are presented. The dark-state pigment was added into the assay buffer at arrow a′. The sample was then photobleached at arrow b′ to form the Meta-II state. After Meta-II decay was close to completion at arrow c′, ligand 11CR was added to initiate pigment regeneration. The binding between opsin and 9CR (k2 = (0.67 ± 0.03) × 103m−1 s−1) was slightly slower than that between opsin and 11CR (k2 = (1.08 ± 0.04) × 103m−1 s−1). To see this figure in color, go online.

We reconstituted immunopurified Rho into a POPC/CHAPS bicelle system. The long-chain phospholipid POPC forms small lipid bilayer fragments, which are edge-stabilized by the detergent CHAPS to promote dispersion in the aqueous phase. Similar to nanodiscs or nanoscale apolipoprotein-bound bilayers (NABBs) (17), bicelles provide a planar lipid environment for membrane proteins.

We photobleached the samples and observed a monoexponential increase of Trp fluorescence corresponding to Meta-II decay. After the Meta-II photoproduct decayed to completion, we added exogenous 11CR or 9CR to the photobleached Rho (Fig. 2, D and E). We found that the addition of 9CR or 11CR initiated a robust monoexponential decrease in the Trp fluorescence signals, indicating the formation of the binding product between retinals and opsin. The binding rates of opsin with 9CR and 11CR at 28°C were determined to be (0.67 ± 0.03) × 103 m−1 s−1 and (1.08 ± 0.04) × 103 m−1 s−1, respectively.

Because the binding between opsin and 9CR was only modestly slower than that between opsin and 11CR, when 9CR is supplied in excess of Rho, the small fraction of 11CR released from Rho would not efficiently compete with 9CR for the newly formed opsin. The conversion of the newly formed opsin to isoRho will be essentially complete. Therefore, the concentration of isoRho should closely approximate the extent of 11CR dissociation.

Spectrophotometric analysis of chromophore exchange in Rho

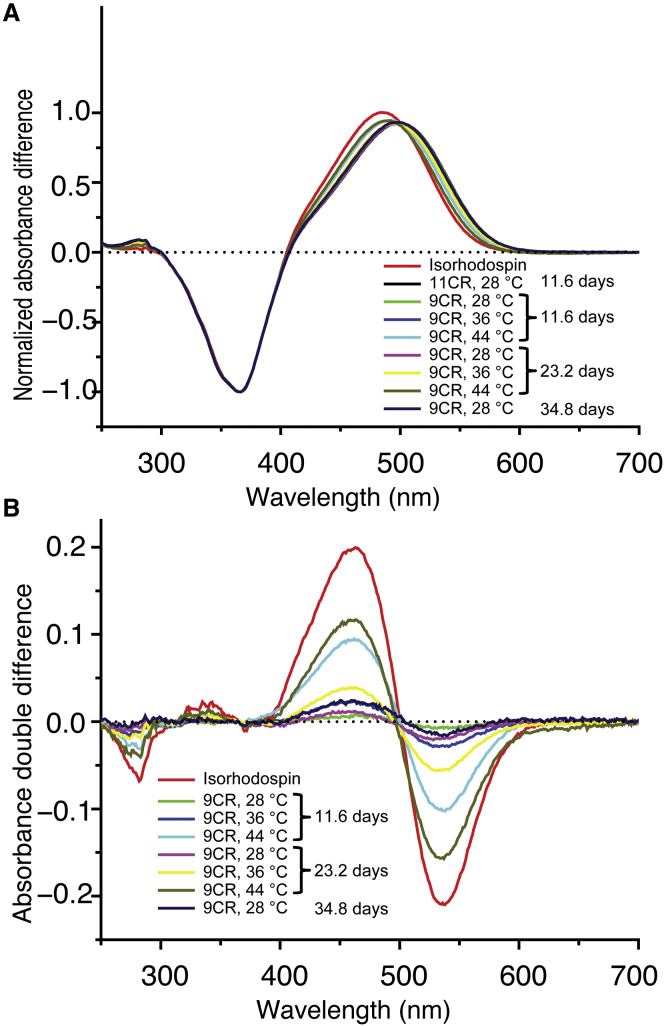

We incubated purified Rho with excess 9CR (the initial molar ratio of 9CR to Rho was 9.2 to 1) at three different temperatures (28°C, 36°C, and 44°C). The slow dissociation rate necessitated very long reaction times (up to 3 × 106 s, 34.8 days) to reliably quantify the chromophore exchange. At the conclusion of the incubation, the samples were immunopurified to remove free retinal and analyzed by ultraviolet-visible (UV-Vis) spectroscopy (Fig. 3). The difference spectra between the dark and the light (photobleached) state correspond to the combined contribution of 11CR and 9CR bound to opsin. As the incubation with 9CR prolonged, the maxima of the difference absorption spectra steadily shifted from 500 to 487 nm, indicating the conversion of the 11CR-bound Rho to 9CR-bound isoRho (Fig. 3 A). We further subtracted the difference spectra of the Rho-isoRho mixtures from the difference spectrum of pure Rho. The decrease in the 500-nm absorbance was used to calculate the fraction of 11CR dissociation (Fig. 3 B).

Figure 3.

Spectrophotometric analysis of the slow chromophore exchange in ROS Rho. Purified Rho (5.3 μm) in POPC/CHAPS bicelle buffer B was supplemented with 9CR (49 μm) and incubated at different temperatures (28°C, 36°C, and 44°C). Aliquots were taken at three different time points (106 s or 11.6 days, 2 × 106 s or 23.2 days, and 3 × 106 s or 34.8 days) and repurified to remove excess retinal. The formation of isoRho was quantified by UV-Vis spectroscopy. (A) The normalized difference absorption spectra were obtained by subtracting the drift-corrected spectra of the photobleached Rho-isoRho mixtures from the spectra of the dark-state samples in presence of hydroxylamine and normalizing to –1 at 365 nm. (B) The double-difference spectra (subtracting the difference spectra of Rho-isoRho mixtures from the difference spectrum of pure Rho) reveal the decrease in the 500-nm absorbance of Rho and increase in the 487-nm absorbance of isoRho. The extent of chromophore exchange was calculated from the decrease of 500-nm absorbance in the double-difference spectra.

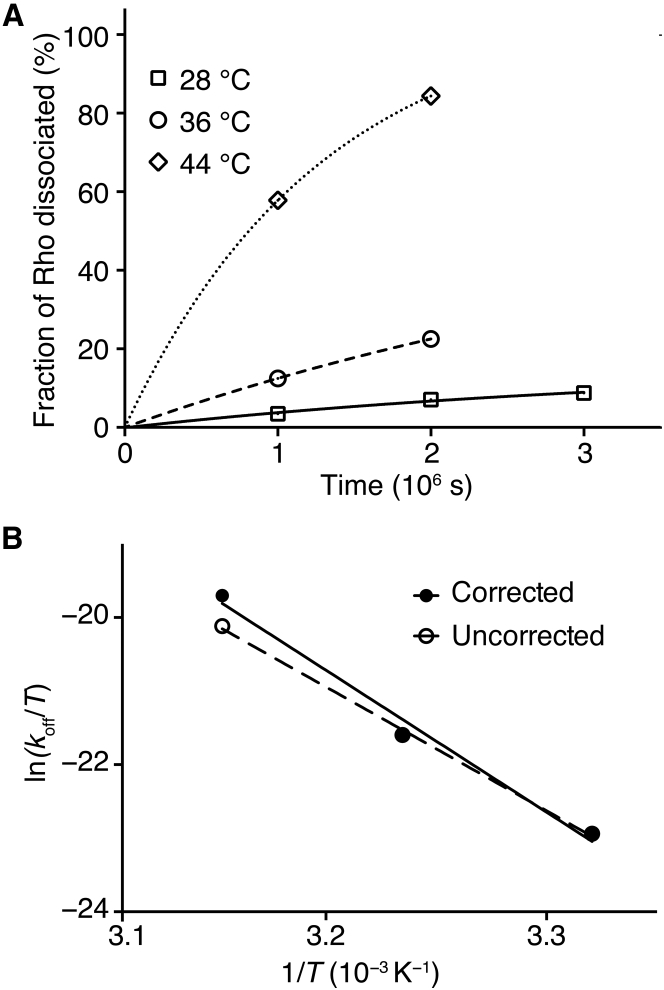

We derived the dissociation rate constant (koff) by assuming that 11CR dissociation from Rho followed a monoexponential model (Fig. 4 A). We found that the POPC/CHAPS bicelle system effectively stabilized opsin over the long incubation time, as loss of denatured opsin was observed only at 44°C, whose effect was corrected as described in the Supporting Material. The dissociation rate (koff) at 37°C was calculated to be 2.2 × 10−7 s−1. We performed Eyring analysis (Fig. 4 B) to derive the activation enthalpy (38.4 ± 4.4 kcal mol−1).

Figure 4.

Analysis of the chromophore exchange rates. (A) Derivation of the dissociation rate constant (koff): the fraction of Rho dissociation in the chromophore exchange measurement was plotted versus the incubation time at 28°C (square), 36°C (circle), and 44°C (diamond, corrected for the denaturation of opsin) and fitted using a monoexponential model. (B) Eyring plot for the chromophore dissociation kinetics is shown. The exchange rate at 44°C was corrected for contribution of opsin denaturation as described in the Supporting Material. The activation enthalpies derived from the corrected data (solid line) and the uncorrected data (dash line) are 38.5 ± 4.4 kcal mol−1 and 33.5 ± 1.4 kcal mol−1, respectively.

Discussion

Advantages of using POPC/CHAPS bicelles for receptor reconstitution

Our aim was to characterize the chromophore exchange in Rho in a homogeneous, chemically defined system. Here we utilized the POPC/CHAPS bicelle system to reconstitute Rho. Various bicelle systems have been shown to retain the structural and functional integrity of membrane proteins (18). Previously, we have shown that the binding product between 11CR and photobleached Alexa488-labeled Rho in the bicelle system could be repeatedly photoactivated, demonstrating the regeneration of mature pigment (19). In our study, we used Trp fluorescence to show that the photobleached Rho in bicelles bind with 11CR or 9CR with comparable kinetic rate constants.

The attempt at direct characterization of the chromophore exchange in the native ROS disc membrane has significant technical challenges. The ROS disc membranes have a heterogeneous structure containing Rho, residual retinoids, and other integral and periphery membrane proteins. Notably, the ROS membranes contain phosphatidylethanolamine that have a chance to react with retinals through Schiff-base chemistry (20). The nonspecific binding between retinal and other components in the ROS membrane, as well as the binding between retinal and lipids, might affect the measurements in a nontrivial way. Also, the ROS membranes contain a high level of polyunsaturated lipids that are highly susceptible to oxidative damage. Experiments under an inert argon atmosphere and in presence of antioxidants are possible for short experiments, but not on a timescale of weeks required for the chromophore exchange experiment.

The spontaneous dissociation of 11CR from Rho

A key finding in this study is that the spontaneous PSB bond breaking and dissociation of 11CR occurs at an appreciable rate under the physiological temperatures (koff of 2.2 × 10−7 s−1 or t1/2 = 36 days at 37°C ). This slow in vitro exchange rate in bicelles is consistent with the earlier observation that incubating salamander red rods with 9CR for 5 h did not produce any spectral shift detectable by microspectrophotometry (3). Our in vitro data showed a dissociation rate constant that is slightly larger than the in vivo chromophore exchange rate measured by radioactive labeling study on dark-adapted retinas in living mice kept in the dark (1.8 × 10−7 s−1 at 37°C) (7). This ∼20% discrepancy could have resulted from the increased water accessibility in the bicelles as compared with native membranes of ROS, a subtle structural difference of murine versus bovine rhodopsin, or merely experimental variation. The comparison of the in vivo and in vitro exchange rates suggests that our value is likely to have the correct order of magnitude, and that the POPC/CHAPS bicelle system is a good approximation of native membranes for biochemical studies. An advantage of our in vitro measurement, however, is that we could investigate the temperature-dependence of the chromophore release rate.

Chromophore exchange of 11CR by 9CR has been demonstrated for cone pigments (21, 22, 23). The exchange in gecko cone pigment P521 reconstituted in digitonin was shown to be ∼30% in 15 h at 15°C, corresponding to a koff of 6.6 × 10−6 s−1 (22). Our measured dissociation kinetics, when extrapolated to 15°C, gives a koff of 1.5 × 10−9 s−1. Thus the dissociation of chromophore from the gecko cone pigment is 4400-fold faster than that in rod pigment. Rod pigment has an enclosed ligand binding pocket, whereas ligand binding pockets of cone pigments are inferred to be much more accessible to solvents. Our data suggest that the difference between rod and cone pigments is not entirely clear-cut; the ligand-binding pocket of rod pigment could be more labile than previously thought.

The chromophore dissociation pathways of Rho

Our measured dissociation rate theoretically could include the contributions of two pathways: 1) direct bond breaking between 11CR and opsin, followed by the release of 11CR from the ligand binding pocket; and 2) thermal isomerization of 11CR to ATR, followed by the release of ATR. The second pathway involves the formation of the active opsin-ATR complex (Meta-II Rho). In the literature, these two pathways are often collectively referred to as the “thermal decay” of Rho. The question here is how much each pathway contributed to the chromophore dissociation measured in our study.

Previously, the thermal decay of Rho has been quantified by heating Rho samples in native disc membranes (10, 24) or reconstituted in detergent micelles (8, 9, 10, 24) (Figs. 5 and S1; Table S2). Janz and Farrens (8) and Guo et al. (9) described the measurement of the thermal decay of Rho in DM micelles using the decrease of the 500-nm peak as the read-out. We noticed that Janz and Farrens performed their measurement at 1-min interval over a time course of hours (8). By comparison, Guo et al. derived the decay rates from fewer time points (9). To obtain the absorption spectrum, a small fraction of dark-state Rho was necessarily photobleached. It is possible that the higher thermal decay rates in the Janz and Farrens study could be an overestimation due to the accumulated photobleaching effect.

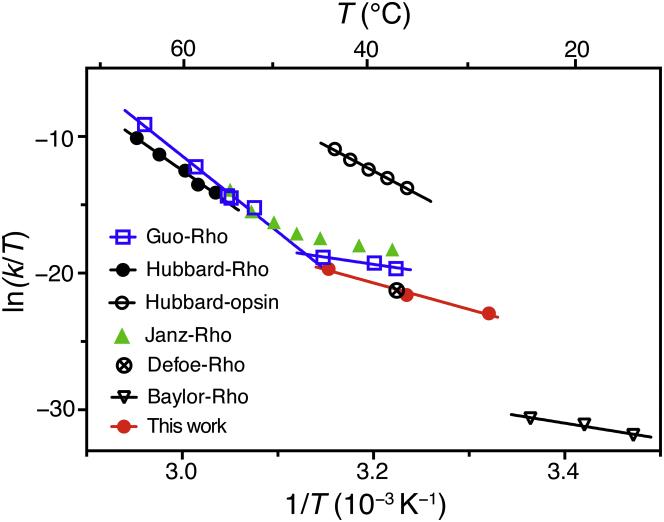

Figure 5.

Comparison of the Eyring plots for the chromophore exchange reaction with thermal decay rates of Rho or opsin, and with spontaneous isomerization and activation of rhodopsin: (empty blue square) the thermal decay of Rho in 0.1% DM (9); (solid black circle) Rho in 2% digitonin (10); (empty black circle) opsin in 2% digitonin (10); (solid green triangle) Rho in 0.05% DM (8); (crossed empty circle) chromophore exchange of Rho in mouse retina measured by radioactive tracers in vivo (7); (inverted empty triangle) spontaneous isomerization and activation of Rho in toad retina measured electrophysiological recording (4); and (red solid circle) Rho chromophore release and exchange with 9CR in 1% POPC/CHAPS bicelles from our study. The in vivo chromophore exchange rate closely matches that observed in our study. Chromophore release is more than three orders of magnitude faster than spontaneous isomerization, suggesting that breaking of the covalent protonated Schiff base (PBS) rather than thermal isomerization is the mechanism underlying the measured chromophore exchange process. The activation enthalpies and entropies of the linear fittings are shown in Table S2. To see this figure in color, go online.

Both Janz and Farrens (8) and Guo et al. (9) reported that the thermal decay of Rho in DM micelles exhibited a concave slope in the Eyring plot. Guo et al. found that at high temperatures (∼52.0°C to 64.6°C), the activation enthalpy (Δ‡H =110 ± 7 kcal mol−1) and entropy (Δ‡S = 261 ± 15 cal mol−1K−1) were unusually large (9), which was consistent with the data for rhodopsin denaturation obtained by Hubbard (10). This very high activation enthalpy was attributed to the breaking of a hydrogen bond network and subsequent denaturation of Rho (9). In the lower temperature regime (∼37.1°C to 44.6°C), which is comparable with the conditions investigated in our study (∼28.0°C to 44.0°C), the activation enthalpy for the thermal decay of Rho dropped to 20.6 ± 4.5 kcal mol−1 (9). Here we determined the activation energy for 11CR dissociation to be 38.5 ± 4.4 kcal mol−1. Moreover, our dissociation rate (∼10−7 s−1) is one order of magnitude slower than the thermal decay rate (∼10−6 s−1) obtained by Janz and Farrens, or Guo et al.

Our experimental scheme differs from those earlier studies (8, 9, 10) in two important ways. First, we chose to use membrane bilayer-mimic detergent/lipid bicelles to reconstitute Rho, whereas Janz and Farrens, and Guo et al. performed the measurements in 0.05% or 0.1% (w/v) DM micelles, respectively. It is known that substituting lipids for detergents reduced the thermal stability of Rho and opsin (10, 24). Hubbard measured the thermal decay rate in 2% digitonin, which has been shown more effective than DM in stabilizing opsin (13). It is worth noting that in the Hubbard study petroleum ether was used to extract the lipids from ROS membranes. If the extraction were incomplete, the measurement would be inadvertently performed in a mixed detergent/lipid system. Second, the presence of excess 9CR further stabilizes the apoprotein by forming isoRho. In our study we only observed a moderate degree of opsin denaturation in the chromophore exchange experiment at 44°C and corrected for this effect. Compared with heating rod pigment in solution, our chromophore exchange scheme should include less contribution from opsin denaturation.

We did not attempt to quantify the amount of ATR, if any, in our system. The excess of 9CR to Rho imposed a technical challenge for quantifying the presence of ATR. More importantly, Hubbard showed that thermally denatured Rho released 11CR, which, however, quickly isomerized to all-trans configuration; even the presence of denatured opsin made 11CR sterically labile and prone to isomerization (10). Therefore, even if the concentration of ATR in our system could be reliably measured, it would be difficult to determine, in such an in vitro biochemical experiment, whether cis-trans isomerization of retinal occurred inside the ligand binding pocket or only after dissociation from the apoprotein.

Meanwhile, the electrophysiological recording may provide a clue for the isomerization rate of 11CR inside the binding pocket. Baylor et al. found that rod cells in dark-adapted retina underwent spontaneous activation events similar to the single photon effect on the rods. Because the retina was not illuminated by any photon, the electrophysiologically detectable activation of single Rho molecules was mostly likely to arise from the thermal isomerization of 11CR to ATR inside the ligand-binding pocket that then produced active Meta-II molecules. The thermal activation rate of Rho in the native disc membrane was on the order of 10−11 s−1 (4, 5), with an activation energy of 22 kcal mol−1 (4). Comparison of the electrophysiological data and our data suggests that the first pathway, i.e., direct 11CR dissociation, is three orders of magnitude faster than the second pathway involving the thermal isomerization of bound 11CR.

Based on these kinetic and thermodynamic measurements, the thermal decay process of Rho examined here consists of one predominant pathway, that is, the breaking of the PSB linkage between retinal and opsin. By contrast, those earlier reports (8, 9, 10) measured a mixed process compounded by the denaturation of protein. At low temperature (<45°C), direct PSB breaking is faster than the thermal denaturation of Rho. At high temperature (>45°C), Rho denaturation becomes the dominant mechanism leading to subsequent retinal release.

Estimating the level of free opsin in rod cells from the chromophore dissociation rate

Is it possible to determine how many ligand-free opsin molecules exist in a rod cell? The psychophysical data on dark adaptation shows that at low bleaching levels, the exponential component of Rho regeneration in human retina has a kreg of 0.09 min−1, or 1.5 × 10−3 s−1 (25). This pseudo first-order rate for Rho regeneration is determined by the second-order reaction rate for the recombination between 11CR and opsin (k2) and the concentration of free 11CR in the ROS. Assuming the concentration of available 11CR in the exponential phase of regeneration is the same as in the dark-adapted retina we obtain the following:

| (1) |

In the equilibrium of the dark-adapted retina, the rate of the dissociation of 11CR from Rho is equal to that of the formation of new Rho molecules, thus we have the following:

| (2) |

Together with Eq. 1 we can eliminate the need to determine the concentration of free 11CR and obtain the following relations:

| (3) |

| (4) |

Therefore, the opsin-to-Rho ratio is 1.5 × 10−4 in dark-adapted rod cells. The concentration of rhodopsin in rods was reported to be 4.6 mm (26), and we estimate the concentration of free opsin as 0.67 μm. The numbers of Rho molecules in a single monkey rod and toad rod are 1.2 × 108 and 2.7 × 109, respectively (4, 5), which corresponds to a range of 104 to 105 free opsin molecules per rod cell. Since human rods are comparable in size with monkey rods, we estimate the number of free opsin molecules in one typical human rod cell to be ∼18,000.

The physiological implications of free opsin in rod cell signaling

The dark noise of a single rod cell consists of two components: the discrete photon-like events characterized by low frequency and high amplitude; and the continuous fluctuations with high frequency and low amplitude (4, 5, 27). The discrete component (Ea = 22 kcal mol−1) was attributed to the thermal isomerization of the bound 11CR to ATR (Ea = 24.5 kcal mol−1) (28) based on their similar activation energies. Thermal activation of Rho, like photoactivation, proceeds through the Meta-II pathway to generate fully activated receptor, which would eventually translate into a decreased cGMP level and the hyperpolarization of the rod cell. The continuous noise was thought to reflect the shot effect of weaker events like the spontaneous activities of downstream signaling molecules occurring at a much higher frequency. In salamander rods, the continuous component was shown to be independent of G protein (29). The discrete component corresponding to the thermal isomerization events is thought to set the rod visual threshold (30).

The obvious question related to our biochemical determinations is whether the free opsin makes any contribution to the dark noise. In contrast to the opsin formed during Meta-II decay following the photoactivation or thermal activation of Rho, the free opsin resulting from spontaneous PSB breaking should not be phosphorylated nor arrestin-bound. Opsin exhibits a low level (∼10−6 relative to fully activated Meta-II Rho, Table 1) of basal activity (31, 32). The total number of opsin (∼104 to 105) correspond to ∼0.01 to 0.1 Meta-II Rho per rod cell per second. This value is well below the background light required for background adaptation of mammalian rods (equivalent to ∼30 to 50 Meta-II Rho per rod cell per second) (33). Moreover, if signaling of free opsin, like the continuous noise, exhibits high frequency and low amplitude, it may be filtered by the nonlinearity of rod-to-rod bipolar synapses (30). In earlier studies, exogenous supply of 11CR to dark-adapted rod cells failed to enhance rod sensitivity, suggesting that the small population of free opsin indeed does not cause elevated threshold (3).

Table 1.

Light-Independent Pathways for Rod Photoreceptor Activation

| Receptor | Free Opsin | Opsin-ATR Noncovalent Complex | Opsin-11CR Noncovalent Complex | Meta-II (Thermally Activated) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number/roda | ∼104 to 105b | –c | ∼10 to 102 s−1d | ∼10−2 to 10−1 s−1e |

| Relative activity | 10−6f | ∼0.03 to 0.14g | –h | 1 |

| Predicted response to extra 11CR | decrease | decrease | transiently increasei | unchanged |

| Predicted response to extra ATR | decrease | increase | decrease | unchanged |

One rod cell contains ∼108 to 109 molecules of Rho, depending on the species (26).

Calculated from Eqs. 1 to 4.

The value is dependent on the concentration of ATR in dark-adapted retina, which was estimated to be less than 5% of 11CR (39).

Calculated based on the koff (2.2 × 10−7 s−1 at 37°C) and the total number of Rho (∼108 to 109). At the equilibrium state, the rate of 11CR binding is equal to the dissociation rate. The activity of this noncovalent complex is transient and only detected by electrophysiological recording.

Estimated based on the discrete dark noise, using a koff of 5.2 × 10−11 s−1 in monkey retina (5).

Although the opsin-11CR noncovalent complex cannot be purified and characterized because of its transient nature, the electrophysiological data showed substantial signaling by the complex (37).

Upon addition of 11CR, the number of the opsin-11CR noncovalent complexes will transiently increase and then relax to the original level.

On the other hand, opsin is exposed to the retinoids present in the ROS membrane, many of which are agonists for opsin, with ATR as the most potent one (34). The activity of ATR/opsin noncovalent complex (∼0.03 to 0.14 of Meta-II) is five orders of magnitude higher than that of free opsin (35, 36). The concentration of ATR/opsin complex has not been determined, but is dependent on the availability of ATR in ROS disc membrane. Moreover, an electrophysiological study showed that the binding between opsin and 11CR first transiently activates the rod receptor and then deactivates it (37). The formation of transiently active 11CR/opsin noncovalent complex occurs at a frequency of ∼10 to 100 s−1 based on our estimates of the steady-state opsin regeneration rates in the dark-adapted rod cells. The potential roles of retinal/opsin complexes with respect to dark noise have not been assessed.

Ensemble measurements cannot shed light on the activity of opsin/retinal complex at the single-molecule level. The conformational ensemble of GPCRs with low apparent activities actually are comprised mostly of single molecules at inactive conformational states, and a small subpopulation at the active states that may activate G protein (38). Because a photon-like signaling event in rod cells involves activation of tens to hundreds of transducin molecules within less than 0.1 s (6), the lifetimes of opsin-retinal complex at the active state would be a major factor for determining whether such a photo-like event is possible. We contend that electrophysiological recording should be employed to examine whether a fraction of opsin-retinal complex can reach the fully active conformation to produce the discrete photon-like noise and potentially cause an elevated scotopic threshold. The relatively high activity of ATR/opsin noncovalent complex implies that the mechanism to deplete ATR from the disc membrane may be important for suppressing rod noise.

Conclusion

We utilized a chromophore exchange assay to show that 11CR slowly dissociates from the ligand-binding pocket of dark-adapted Rho with a koff of 2.2 × 10−7 s−1 at 37°C. Our analysis found that the spontaneous hydrolysis of PSB bond is three orders of magnitude faster than the thermal isomerization of 11CR, thus constituting the major decay pathway of dark-state Rho. This slow dissociation of 11CR from Rho suggests the presence of a population of free opsin and constant turnover of Rho molecules in dark-adapted mammalian rods. We contend that this higher-than-expected level of opsin may have implications in rod cell dark noise.

Author Contributions

H.T., T.P.S., and T.H designed the study, analyzed the results, and wrote the manuscript. H.T. and T.H. conducted the experiments.

Acknowledgments

We thank Prof. King-Wai Yau for discussions of this work.

We acknowledge the generous support from the Crowley Family Fund and the Danica Foundation. This work has also been generously supported by an International Research Alliance with Professor Thue W. Schwartz at The Novo Nordisk Foundation Center for Basic Metabolic Research (http://www.metabol.ku.dk) through an unconditional grant from the Novo Nordisk Foundation to University of Copenhagen. We also acknowledge the support from NIH R01 EY012049 (T.P.S. and T.H.), as well as the Tri-Institutional Training Program in Chemical Biology in supporting H.T.

Editor: Elsa Yan

Footnotes

He Tian’s present address is Department of Chemistry and Chemical Biology, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA.

Supporting Material and Methods, one figure, and two tables are available at http://www.biophysj.org/biophysj/supplemental/S0006-3495(16)34280-1.

Contributor Information

Thomas P. Sakmar, Email: sakmar@rockefeller.edu.

Thomas Huber, Email: hubert@rockefeller.edu.

Supporting Material

References

- 1.Menon S.T., Han M., Sakmar T.P. Rhodopsin: structural basis of molecular physiology. Physiol. Rev. 2001;81:1659–1688. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2001.81.4.1659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Farrens D.L., Khorana H.G. Structure and function in rhodopsin: measurement of the rate of metarhodopsin II decay by fluorescence spectroscopy. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:5073–5076. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.10.5073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kefalov V.J., Estevez M.E., Yau K.W. Breaking the covalent bond—a pigment property that contributes to desensitization in cones. Neuron. 2005;46:879–890. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baylor D.A., Matthews G., Yau K.W. Two components of electrical dark noise in toad retinal rod outer segments. J. Physiol. 1980;309:591–621. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1980.sp013529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baylor D.A., Nunn B.J., Schnapf J.L. The photocurrent, noise and spectral sensitivity of rods of the monkey Macaca-Fascicularis. J. Physiol. 1984;357:575–607. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1984.sp015518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Luo D.G., Xue T., Yau K.W. How vision begins: an odyssey. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:9855–9862. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708405105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Defoe D.M., Bok D. Rhodopsin chromophore exchanges among opsin molecules in the dark. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 1983;24:1211–1226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Janz J.M., Farrens D.L. Role of the retinal hydrogen bond network in rhodopsin Schiff base stability and hydrolysis. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:55886–55894. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M408766200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guo Y., Sekharan S., Yan E.C. Unusual kinetics of thermal decay of dim-light photoreceptors in vertebrate vision. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2014;111:10438–10443. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1410826111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hubbard R. The thermal stability of rhodopsin and opsin. J. Gen. Physiol. 1958;42:259–280. doi: 10.1085/jgp.42.2.259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Palczewski K., Kumasaka T., Miyano M. Crystal structure of rhodopsin: a G protein-coupled receptor. Science. 2000;289:739–745. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5480.739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Park J.H., Scheerer P., Ernst O.P. Crystal structure of the ligand-free G-protein-coupled receptor opsin. Nature. 2008;454:183–187. doi: 10.1038/nature07063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Degrip W.J. Thermal stability of rhodopsin and opsin in some novel detergents. Methods Enzymol. 1982;81:256–265. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(82)81040-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hubbard R., Wald G. Cis-trans isomers of vitamin A and retinene in the rhodopsin system. J. Gen. Physiol. 1952;36:269–315. doi: 10.1085/jgp.36.2.269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Okada T., Sugihara M., Buss V. The retinal conformation and its environment in rhodopsin in light of a new 2.2 Å crystal structure. J. Mol. Biol. 2004;342:571–583. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.07.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nakamichi H., Buss V., Okada T. Photoisomerization mechanism of rhodopsin and 9-cis-rhodopsin revealed by X-ray crystallography. Biophys. J. 2007;92:L106–L108. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.108225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Banerjee S., Huber T., Sakmar T.P. Rapid incorporation of functional rhodopsin into nanoscale apolipoprotein bound bilayer (NABB) particles. J. Mol. Biol. 2008;377:1067–1081. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.01.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Durr U.H., Gildenberg M., Ramamoorthy A. The magic of bicelles lights up membrane protein structure. Chem. Rev. 2012;112:6054–6074. doi: 10.1021/cr300061w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tian H., Naganathan S., Huber T. Bioorthogonal fluorescent labeling of functional G protein-coupled receptors. ChemBioChem. 2014;15:1820–1829. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201402193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Anderson R.E., Maude M.B. Phospholipids of bovine rod outer segments. Biochemistry. 1970;9:3624–3628. doi: 10.1021/bi00820a019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Matsumoto H., Tokunaga F., Yoshizawa T. Accessibility of the iodopsin chromophore. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1975;404:300–308. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(75)90337-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Crescitelli F. The gecko visual pigment: the chromophore dark exchange reaction. Exp. Eye Res. 1988;46:239–248. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4835(88)80081-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shichida Y., Kato T., Yoshizawa T. Effects of chloride on chicken iodopsin and the chromophore transfer reactions from iodopsin to scotopsin and B-photopsin. Biochemistry. 1990;29:5843–5848. doi: 10.1021/bi00476a028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Corley S.C., Sprangers P., Albert A.D. The bilayer enhances rhodopsin kinetic stability in bovine rod outer segment disk membranes. Biophys. J. 2011;100:2946–2954. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2011.05.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lamb T.D., Pugh E.N., Jr. Dark adaptation and the retinoid cycle of vision. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2004;23:307–380. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2004.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nickell S., Park P.S., Palczewski K. Three-dimensional architecture of murine rod outer segments determined by cryoelectron tomography. J. Cell Biol. 2007;177:917–925. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200612010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Barlow R.B., Birge R.R., Tallent J.R. On the molecular origin of photoreceptor noise. Nature. 1993;366:64–66. doi: 10.1038/366064a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hubbard R. The stereoisomerization of 11-cis-retinal. J. Biol. Chem. 1966;241:1814–1818. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rieke F., Baylor D.A. Molecular origin of continuous dark noise in rod photoreceptors. Biophys. J. 1996;71:2553–2572. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(96)79448-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Field G.D., Sampath A.P., Rieke F. Retinal processing near absolute threshold: from behavior to mechanism. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2005;67:491–514. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.67.031103.151256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cornwall M.C., Fain G.L. Bleached pigment activates transduction in isolated rods of the salamander retina. J. Physiol. 1994;480:261–279. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1994.sp020358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Melia T.J., Cowan C.W., Wensel T.G. A comparison of the efficiency of G protein activation by ligand-free and light-activated forms of rhodopsin. Biophys. J. 1997;73:3182–3191. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(97)78344-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fu Y., Kefalov V., Yau K.W. Quantal noise from human red cone pigment. Nat. Neurosci. 2008;11:565–571. doi: 10.1038/nn.2110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kono M., Goletz P.W., Crouch R.K. 11-cis- and all-trans-retinols can activate rod opsin: rational design of the visual cycle. Biochemistry. 2008;47:7567–7571. doi: 10.1021/bi800357b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jager S., Palczewski K., Hofmann K.P. Opsin/all-trans-retinal complex activates transducin by different mechanisms than photolyzed rhodopsin. Biochemistry. 1996;35:2901–2908. doi: 10.1021/bi9524068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Han M., Sakmar T.P. Assays for activation of recombinant expressed opsins by all-trans-retinals. Methods Enzymol. 2000;315:251–267. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(00)15848-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kefalov V.J., Crouch R.K., Cornwall M.C. Role of noncovalent binding of 11-cis-retinal to opsin in dark adaptation of rod and cone photoreceptors. Neuron. 2001;29:749–755. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00249-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Deupi X., Kobilka B.K. Energy landscapes as a tool to integrate GPCR structure, dynamics, and function. Physiology (Bethesda) 2010;25:293–303. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00002.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Saari J.C., Garwin G.G., Palczewski K. Reduction of all-trans-retinal limits regeneration of visual pigment in mice. Vision Res. 1998;38:1325–1333. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6989(97)00198-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.