Abstract

An ERF/AP2-type transcription factor (CaPF1) was isolated by differential-display reverse transcription-PCR, following inoculation of the soybean pustule pathogen Xanthomonas axonopodis pv glycines 8ra, which induces hypersensitive response in pepper (Capsicum annuum) leaves. CaPF1 mRNA was induced under conditions of biotic and abiotic stress. Higher levels of CaPF1 transcripts were observed in disease-resistant tissue compared with susceptible tissue. CaPF1 expression was additionally induced using various treatment regimes, including ethephon, methyl jasmonate, and cold stress. To determine the role of CaPF1 in plants, transgenic Arabidopsis and tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) plants expressing higher levels of CaPF1 were generated. Gene expression analyses of transgenic Arabidopsis and tobacco revealed that the CaPF1 level in transgenic plants affects expression of genes that contain either a GCC or a CRT/DRE box in their promoter regions. Furthermore, transgenic Arabidopsis plants expressing CaPF1 displayed tolerance against freezing temperatures and enhanced resistance to Pseudomonas syringae pv tomato DC3000. Disease tolerance was additionally observed in CaPF1 transgenic tobacco plants. The results collectively indicate that CaPF1 is an ERF/AP2 transcription factor in hot pepper plants that may play dual roles in response to biotic and abiotic stress in plants.

During their life cycle, plants have to deal with various environmental stress conditions. Biotic and abiotic stress factors cause adverse effects on the growth and productivity of crops. To adjust to changes in the environment, plants trigger rapid defense responses via a number of signal transduction pathways. A major target of signal transduction is the cell nucleus, where terminal signals lead to the transcriptional activation of numerous genes. Alterations in the expression of genes coding for transcription regulators greatly influence plant stress tolerance. In Arabidopsis, a number of transcription factor families, each containing a distinct type of DNA-binding domain, such as ERF/AP2, bZIP/HD-ZIP, Myb, WRKY, and several classes of zinc-finger domains, have been implicated in plant stress responses in view of the finding that their expression is induced or repressed under different stress conditions (Rushton and Somssich, 1998; Shinozaki and Yamaguchi-Shinozaki, 2000). For example, Arabidopsis plants expressing the tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum) ethylene-response factor (ERF) Pti4 displayed increased resistance to the fungal pathogen Erysiphe orontii, and increased tolerance to the bacterial pathogen Pseudomonas syringae pv tomato. Pti4 may function as a transcriptional activator to regulate the expression of GCC box-containing genes (Gu et al., 2002; Wu et al., 2002). In another case, overexpression of two Arabidopsis ERF/AP2 genes, CBF1/DREBP1B and DREBP1A, resulted in enhanced tolerance to drought, salt, and freezing (Jaglo-Ottosen et al., 1998). These two transcription factors bind the cold-responsive cis-element CRT/DRE and activate the expression of target genes (Kasuga et al., 1999).

Common regulatory components, including phytohormones, are involved in separate signaling pathways. Salicylic acid (SA), ethylene (ET), and jasmonic acid (JA) possibly act as secondary signals following pathogen attack and enhance the expression of many pathogen-responsive genes (Yang et al., 1997). Drought and high salinity lead to the production of high levels of abscisic acid (ABA). Exogenous application of ABA induces a number of genes that are expressed in response to dehydration and cold stress. These findings suggest that differences in expression patterns of biotic- and abiotic-responsive genes are a result of the alternative regulation of transcription factors and phytohormones by diverse stress signals. Recent studies provide evidence for cross-talk between biotic and abiotic stress signaling pathways. For example, the gene expression profiles observed during an incompatible plant-fungal interaction overlap with those derived from wounding (Durrant et al., 2000). Experiments with cDNA microarrays reveal that a substantial number of genes are coordinately regulated by different biotic/abiotic stress signals via infection with a fungal pathogen (Schenk et al., 2000) or in conditions of cold/drought stress (Seki et al., 2001). Another global gene expression approach using microarrays with 402 Arabidopsis transcription factors revealed a clear overlap of genes expressed in response to different stress factors. There was also significant overlap with the genes expressed during senescence (Chen et al., 2002). However, despite accumulating data, the molecular mechanisms underlying this cross-talk are largely unknown. Thus, a thorough knowledge at the molecular level of the mechanism of regulation of cross-talk between biotic and abiotic stress signal pathways is essential to understand how plants activate the correct responses to various environmental stress factors.

Here, we report the characterization of cDNA encoding new pepper ERF, CaPF1 (Capsicum annuum pathogen and freezing tolerance-related protein 1), which binds to both GCC and CRT/DRE cis-elements. The GCC box and CRT/DRE element have similar core sequences, which are implicated in the activation of different signal transduction pathway-related genes. The issue of whether CaPF1 activates two distinct sets of genes that contain the GCC and/or CRT/DRE element in their promoter region and participates in two different stress tolerance events was investigated. In this article, we elucidate the function of this novel ERF, which may contribute to understanding the molecular mechanisms of cross-talk between biotic and abiotic stress signaling pathways.

RESULTS

Expression of CaPF1 during the Hypersensitive Response of Hot Pepper

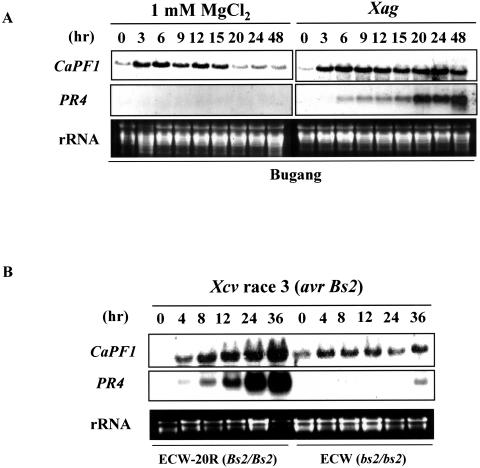

During the selection of non-host resistance hypersensitive response (HR)-induced genes in pepper leaves using mRNA differential-display reverse transcription-PCR, we isolated a CaPF1 cDNA fragment with amino acid similarity to other functionally characterized ERF/AP2 family proteins. We examined whether cDNA expression was induced upon pathogen attack. Young pepper leaves (cv Bugang) were syringe infiltrated with a suspension containing either the soybean pustule pathogen Xanthomonas axonopodis pv glycines 8ra (Xag 8ra) or 1 mm MgCl2 as a control. Non-host HR was noted 18 h after inoculation with Xag 8ra. As shown in Figure 1A, CaPF1 mRNA was induced in both HR and non-HR tissue. However, the abundance and period of the induction were higher and longer, respectively, in HR-occurring tissues. To determine the specificity of CaPF1 in response to HR, we analyzed expression following host resistance-induced HR. Leaves of pepper cultivars ECW-20R (BS2/BS2) and ECW (bs2/bs2) were syringe infiltrated with the pepper bacterial spot pathogen Xanthomonas campestris pv vesicatoria race 3 (Xcv race3), which expresses the avrBS2 gene. Total RNA was extracted from inoculated leaves at different times after infection, and CaPF1 expression was analyzed by northern blotting. Susceptible pepper (cv ECW) infiltrated with Xcv race3 did not exhibit any visible responses until 36 h after infiltration, whereas resistant pepper (cv ECW-20R) developed HR lesions on infiltrated leaf tissues within 24 h (data not shown). Stronger CaPF1 expression was detected in incompatible interactions, while only mild expression was detected in compatible interactions (Fig. 1B). Pepper pathogenesis-related protein 4b (C.J. Park et al., 2001) gene was monitored as a positive control. As expected, up-regulation of the PR4b transcript was only detected in Xcv race 3 (avrBS2) infections of cv ECW-20R (BS2/BS2).

Figure 1.

Expression of CaPF1 mRNA in response to bacterial pathogens. A, Pepper leaves were infiltrated with either a mock solution (1 mm MgCl2) or with solution containing X. axonopodis pv glycines 8ra (non-host pathogen). B, Pepper near-isogenic lines (ECW-20R, resistance; ECW, susceptible) were infiltrated with a pepper leaf spot pathogen, as described in “Materials and Methods.” One blot was hybridized to the CaPF1 probe, while an identical blot was hybridized to the PR4b probe as a positive marker for pathogen infection.

These findings indicate that the CaPF1 expression observed after infection with the HR-inducible bacterial pathogen is consistent and associated with incompatible plant-pathogen interactions.

Isolation and Sequence Analysis of CaPF1

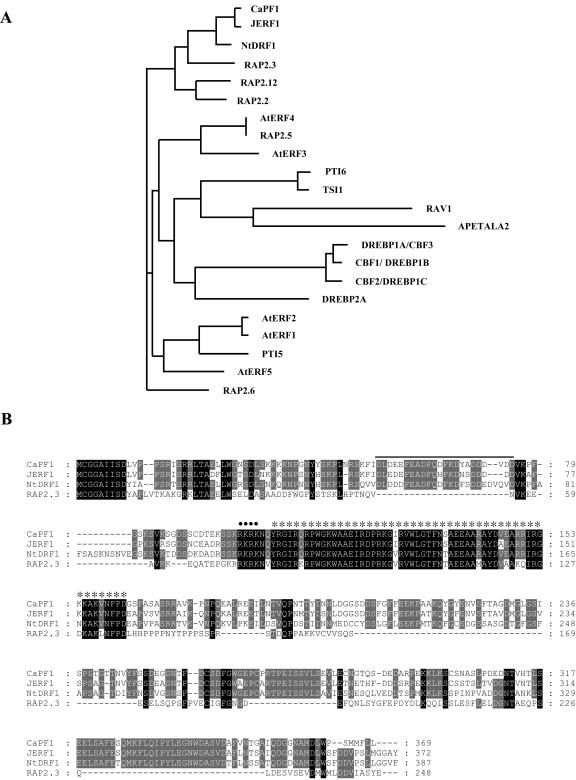

To isolate full-length cDNA, a partial cDNA fragment with sequence similarity to ERF/AP2 family proteins was used as a probe to screen a cDNA library previously constructed from C. annuum (S.Y. Yi, S.H. Yu, and D. Choi, unpublished data). Twelve positive clones were isolated and further analyzed by restriction enzyme digestion and DNA sequencing, resulting in the identification of seven clones with 1.4-kb cDNA inserts. Among these, 5 clones encoded a predicted full-length protein with an open reading frame of 369 amino acids and molecular mass of 41 kD. Nucleotide and protein database searches reveal that the CaPF1 protein contains a 57-amino acid region that constitutes a DNA-binding ERF/AP2 domain, which is highly conserved in members of the ERF/AP2 family of plant transcription factors. CaPF1 contains short clusters of basic residues similar to known nuclear localization sequences (for review, see Dingwall and Laskey, 1991) and an acidic N-terminal region (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2.

Deduced amino acid sequences of ERF/AP2-related proteins and phylogenic relationships of selected ERF domains from ERF/AP2-related proteins. A, Phylogenic comparison of the published ERF/AP2-related protein sequences as well as any published, selected ERF/AP2 domain amino acid sequences in the databases. Alignments were made in ClustalW using the default parameters. The dendrogram was then drawn using PhyloDraw. Accession numbers for the ERF/AP2 proteins used are as follows: CaPF1, AY246274; RAP2.3, P42736; AtERF4, O80340; AtERF2, O80338; AtERF5, O80341; AtERF3, O80339; PTI5, 04681; AtERF1, O80337; PTI6, O04682; RAV1, Q9ZWM9; APETALA2, P47927; JERF1, AAK95687; RAP2.12, AAF02863; RAP2.6, D96498; RAP2.2, AAC49768; RAP2.5, AAC49771.1; Tsi1, AF058827; DREBP1A/CBF3, AB007787; DREBP2A, AB007790; CBF2/DREBP1C, AAC99371; NtDRF1, AAP40022; and CBF1/DREBP1B, AAC99369. B, Comparison of deduced amino acid sequences of ERF/AP2-related proteins that have high sequence similarity with CaPF1. The black bar above the sequences represents the putative acidic domain. Spots (•) represent putative nuclear localization signals. Asterisks (*) indicate conserved DNA-binding domain (ERF domain). Dashes indicate gaps used to optimize alignment. The GenBank, DDBJ, EMBL, and NCBI accession numbers of nucleotide sequences are as follows: pepper cDNA, AY246274 (CaPF1); tomato cDNA, AAK95687 (JERF1); tobacco cDNA, AAP40022 (NtDRF1); and Arabidopsis cDNA, P42736 (RAP2.3).

To explore further the evolutionary distance among the ERF/AP2 proteins, AP2 domains from different plant species that have relatively high amino acid sequence similarity with CaPF1 were subjected to construct phylogenic tree using the PhyloDraw program (version 0.8; Fig. 2A). Phylogenetic analysis with ERF/AP2 domain indicated that the CaPF1 is most similar to previously described ERF class B-2 subgroup (RAP2.3, RAP2.2, and RAP2.12; Sakuma et al., 2002). The deduced amino acid sequence of the CaPF1 and those of its homologs are well conserved in different plant species. CaPF1 has 79% identity with JERF1 from tomato (AAK95687), 65% with NtDRF1 from tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum; AAP40022), and 50% with RAP 2.3 from Arabidopsis (P42736). Conserved domains include the ERF/AP2 domain, putative nuclear localization signals, and a conserved N-terminal motif of unknown function (MCGGAIISD; Fig. 2B). Tournier et al. (2003) recently identified tomato LeERF2, a novel class IV ERF, characterized by an N-terminal signature sequence, MCGGAII/L. This motif was also found in CaPF1; therefore, it could belong to a class IV ERF (Fig. 2B).

Genomic DNA-Blot Analysis and Tissue-Specific Expression of the CaPF1 Transcript

Genomic DNA isolated from pepper was digested with DraI, EcoRI, HindIII, or XbaI. The blot was hybridized to radioactively labeled CaPF1 cDNA (full length) or the 3′ end fragment. Four to five fragments were detected with the CaPF1 full-length cDNA probe, while only a single band hybridized to the 3′ end-specific probe (data not shown). This restriction pattern strongly suggests that the pepper genome contains a single copy of the CaPF1 gene, which belongs to a gene family.

Tissue-specific expression of CaPF1 mRNA was analyzed by northern blotting in eight different tissues. The CaPF1 transcript was less abundant in dormant seeds than germinating seeds (data not shown). Lower levels of CaPF1 transcripts were detected in leaves and seedlings, whereas higher levels of transcripts were detected in floral organs and stem.

Expression of CaPF1 mRNA in Response to Various Treatment Regimes

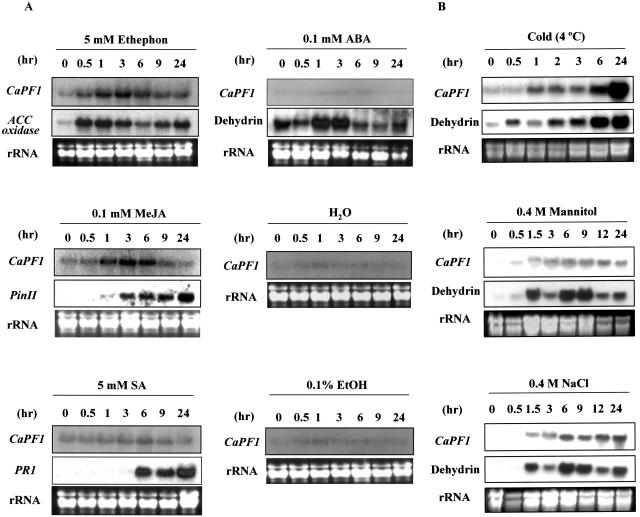

Ethylene plays important roles in a number of plant stress responses (including response to pathogens) and the expression of ERF genes, including ERF1 and AtERF1 (Solano et al., 1998; Fujimoto et al., 2000). To determine whether CaPF1 expression is regulated by ethylene, we treated 2-month-old pepper plants with ethephon. Expression of ACC oxidase (Wang et al., 2002) was monitored as a positive marker for ethephon treatment. CaPF1 mRNA levels were up-regulated within 30 min of treatment with ethephon (Fig. 3A).

Figure 3.

Expression of CaPF1 mRNA in response to chemicals and abiotic stress. A, Expression of CaPF1 mRNA following treatment with ethephon, MJ, SA, or ABA. ACC oxidase, PinII, PR1, and dehydrin genes were used as positive markers for ethephon, MJ, SA, and ABA treatment, respectively. B, CaPF1 expression in response to low temperature, mannitol (drought mimic), and high salt. Total RNA was prepared from 2-month-old pepper plants transferred to a 4°C chamber (cold), 0.4 m mannitol solution, and 0.4 m NaCl solution, as described in “Materials and Methods.” The pepper Dehydrin gene was used as a positive marker for abiotic treatment. Total RNA was extracted from leaf tissues at the different time points indicated.

Similar to ET, SA, and methyl jasmonate (MJ) are important phytohormones involved in signaling in response to pathogen infections. To determine the possible involvement of the CaPF1 gene in SA and MJ signaling pathways, we examined mRNA expression after treatment with these hormones. As shown in Figure 3A, expression of CaPF1 mRNA was detected following treatment with MJ but not SA. The levels of MJ-regulated hot pepper proteinase inhibitor II (PinII) and SA-inducible pathogenesis-related protein I (PR1) genes (Lee et al., 2002) were monitored as positive markers of each treatment. As expected, both transcripts were induced by MJ and SA, respectively.

We additionally examined the expression of CaPF1 mRNA, following challenge with abiotic stress. The pepper dehydrin gene (Chung et al., 2003) was used as a positive marker for abiotic stress treatment. Dehydrin is expressed in spruce seedlings in response to cold, drought, ethylene, as well as treatment with ABA, JA, or wounding (Richard et al., 2000). Pepper plants were grown in soil at 25°C and transferred to low temperatures (4°C) for various periods of time. Northern-blot analysis using a gene-specific probe for CaPF1 revealed an increase in transcript levels within 1 h of cold treatment. Increased CaPF1 transcript levels were observed at all the sampling time points and peaked at 24 h (Fig. 3B). In addition to low temperature, osmotic stress-responsive expression of CaPF1 was monitored following treatment with 0.4 m mannitol (drought mimic conditions) and 0.4 m NaCl. CaPF1 transcript levels were slightly increased within 0.5 and 1.5 h of treatment, which was maintained for 24 h (Fig. 3B). However, CaPF1 transcript level is not responsive to ABA (Fig. 3A). These results collectively indicate that various plant signal, cold, and osmotic stress conditions induce CaPF1 expression.

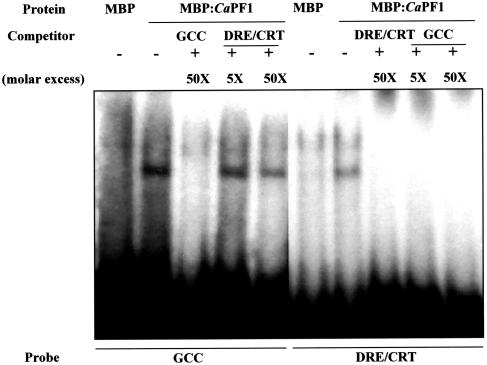

CaPF1 Protein Binds GCC and CRT/DRE Boxes

The observed CaPF1 expression in diverse stress conditions signifies that the protein may function in the activation of numerous stress-responsive genes through binding to one or two cis-acting elements. To test this hypothesis, binding specificity of the CaPF1 protein to known ERF/AP2 factor-binding sequences, GCC box and CRT/DRE cis-element, was evaluated. The entire coding region of CaPF1 was expressed in Escherichia coli by translational fusion with a maltose-binding protein (MBP), and an electrophoretic mobility shift assay was performed. The MBP-CaPF1 fusion protein bound both the GCC-box sequence, and the CRT/DRE cis-element (Fig. 4). To determine the binding specificities, we performed a competition assay by adding unlabeled GCC box and CRT/DRE cis-element to the mobility shift assay. This led to decreased binding of MBP-CaPF1 to the labeled GCC box and CRT/DRE cis-element. Moreover, 50-fold excess of unlabeled GCC box and CRT/DRE DNA resulted in complete loss of binding of the labeled sequences to the MBP-CaPF1 protein. The addition of unlabeled CRT/DRE cis-element DNA (50×) to the binding assay decreased MBP-CaPF1 binding to labeled GCC-box DNA. However, addition of 5-fold excess of unlabeled GCC-box DNA resulted in complete loss of binding of the labeled CRT/DRE cis-element DNA to MBP-CaPF1 (Fig. 4). From these results, we conclude that the CaPF1 binds competitively to both the GCC box and CRT/DRE cis-element. Furthermore, binding specificity is higher with a combination of MBP-CaPF1 and GCC.

Figure 4.

Gel mobility shift assay of the CaPF1 protein. Electrophoretic mobility shift assays were performed using MBP-CaPF1 fusion proteins. 32P γ-ATP-labeled GCC-box and CRT/DRE-box fragments were incubated as described in “Materials and Methods.” The MBP protein was used as a control. Binding of CaPF1 to two radioisotope-labeled cis-elements was competed out with excess unlabeled DNA fragments.

Overexpression of CaPF1 in Arabidopsis Affects Expression of PR and COR Genes

ERF/AP2s are unique to the plant kingdom and have been characterized in different plants, including Arabidopsis, tomato, soybean, and tobacco. They all possess a number of features in common, such as induction by biotic and abiotic stresses and mediation of the expression of GCC box or CRT/DRE box-containing genes such as PDF1.2 in Arabidopsis. Because pepper is a very recalcitrant species in terms of genetic transformation (Li et al., 2000), we constructed transgenic Arabidopsis plants constitutively expressing CaPF1 under control of the cauliflower mosaic virus 35S promoter to study the function of CaPF1 in biotic and abiotic stress responses of plants. From 22 independent Arabidopsis transgenic lines confirmed by northern- and genomic Southern-blot analyses with the transgene probe, three lines (lines 3, 8, and 22; T3 generation) with a single insertion of the transgene were selected for further analyses. None of these transgenic lines displayed any phenotypic abnormality throughout their life cycle.

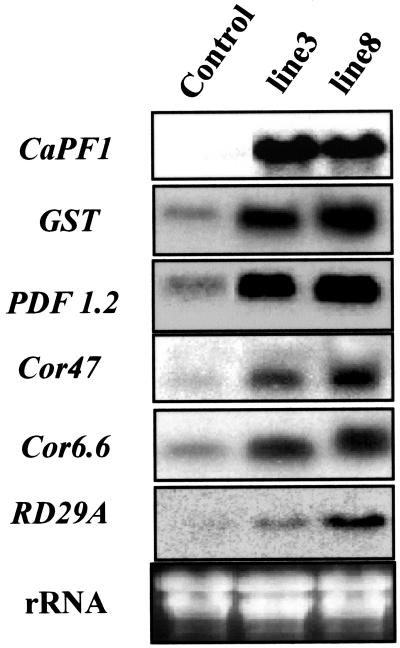

To evaluate the role of ectopically expressed CaPF1 in stress-responsive gene expression of transgenic Arabidopsis, northern-blot analysis was performed using genes containing the GCC box (PDF 1.2) and CRT/DRE element (COR47, COR6.6, and COR78/RD29) in their promoter regions as probes. All the genes tested were constitutively expressed in selected transgenic Arabidopsis lines. Earlier studies show that the expression of PDF1.2 and GST genes in Arabidopsis is dependent on the functions of the JA and ET signaling pathways (Zhou and Goldsbrough, 1993; Penninckx et al., 1998). CaPF1 expression induced an increase in transcript levels of PDP1.2 and GST (Fig. 5). CRT/DRE elements, which contain a conserved 5-bp core sequence (CCGAC), are present in the promoter regions of a number of cold- and dehydration-responsive genes of Arabidopsis, including those designated COR (cold regulated; Thomashow, 1999). CaPF1 transgenic Arabidopsis display COR gene expression in the absence of a low temperature stimulus (Fig. 5). Thus, it seems most likely that CaPF1 is functional in Arabidopsis plants, thereby CaPF1 affects transactivating PR and COR genes.

Figure 5.

Overexpression of CaPF1 in Arabidopsis causes constitutive up-regulation of PR and COR genes. Two individual transgenic lines (lines 3 and 8; T3 generation) and pMPB-1 transformed Arabidopsis (Control) were selected for the RNA gel-blot analysis. Total RNA was isolated from leaves of 4-week-old Arabidopsis plants. Multiple RNA gel blots were hybridized to the indicated probes.

CaPF1 Overexpression Confers Tolerance to Pathogens and Freezing in Transgenic Plants

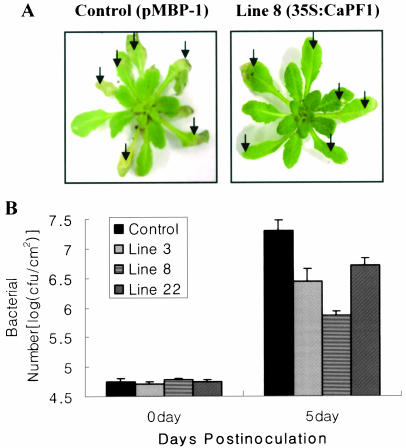

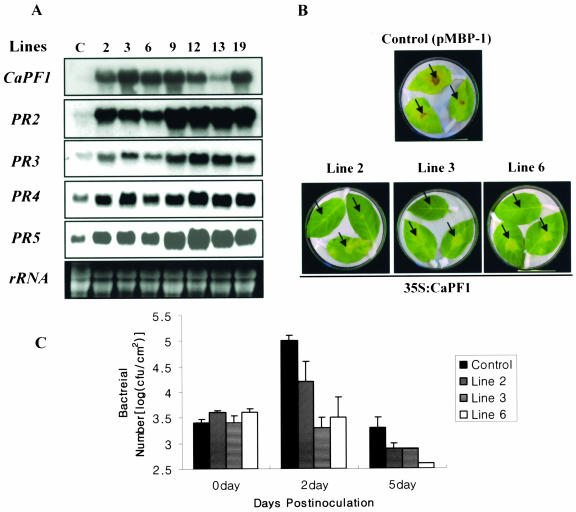

As shown in Figure 5, the expression of CaPF1 in Arabidopsis led to constitutive expression of the stress-related genes. This raised the possibility that stress tolerance is activated in these plants. The CaPF1 plants were first tested in disease tolerance. Three CaPF1 T3 generation transgenic Arabidopsis lines (lines 3, 8, and 22) were tested for resistance against P. syringae pv tomato DC3000 that infects wild-type Arabidopsis Col-0. Leaf bacterial numbers were determined at 0, 3, and 5 d after inoculation. All three plants displayed reduced disease lesion and leaf bacterial numbers compared with the control plant. At 3 d postinoculation, the overexpression of CaPF1 reduces bacterial numbers by 5- to 10-fold (data not shown). As depicted in Figure 6B, 10- to 100-fold reduction in bacterial numbers were detected at 5 d after inoculation in CaPF1 transgenic leaves compared with empty vector-transformed control plants. To confirm the role of CaPF1 in disease tolerance, transgenic tobacco plants were also generated. Tobacco plants were transformed with the same vector construct used in Arabidopsis study. From 16 independent transgenic lines conformed by northern- and Southern-blot analysis with the transgene probe, 7 lines (lines 2, 3, 6, 9, 12, 13, and 19) with a single insertion of the transgene were selected for further analyses. We observed that all selected seven transgenic lines (T0 progenies of CaPF1 transgenic tobacco plants; lines 2, 3, 6, 9, 12, 13, and 19) constitutively expressed pathogenesis-related genes, such as PR2, 3, 4, and 5, in absence of pathogen attack (Fig. 7A). Next, we tested for resistance of transgenic tobacco plants (lines 2, 3, and 6) against P. syringae pv tabaci that infects wild-type tobacco. All three transgenic tobacco lines displayed reduced lesions and leaf bacterial numbers compared with control plants transformed with empty vector (Fig. 7, B and C).

Figure 6.

Bacterial pathogen tolerance of CaPF1 transgenic Arabidopsis plants. A, Photographs were taken 5 d after pathogen inoculation. One typical data from three independent experiments with similar results was presented. Arrows highlight areas of DC3000 infection. B, Reduced bacterial growth in CaPF1 transgenic Arabidopsis plants (lines 3, 8, and 22) compared with control (pMBP-1 transformed). Plants were syringe-infiltrated with 2 × 105 CFU/mL solution of P. syringae pv tomato DC3000, and leaf bacterial numbers were determined at 0 and 5 d after inoculation. Data are presented as means ± sd (n = 3).

Figure 7.

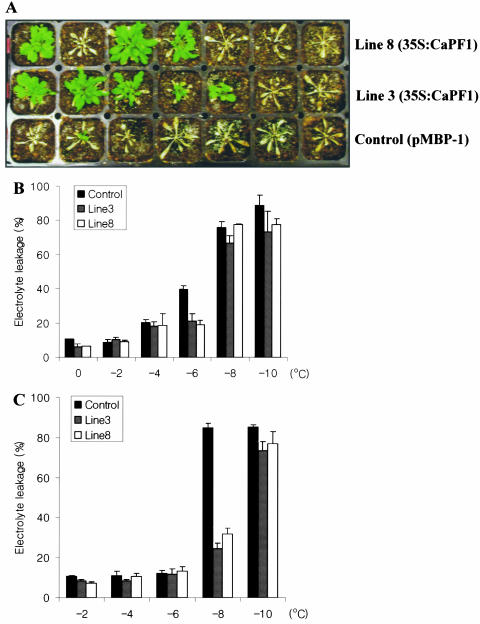

Freezing tolerance of CaPF1 transgenic Arabidopsis plants. A, Photographs were taken 7 d after returning to 25°C. The 5-week-old plants growing on sterile soil in a growth chamber were exposed to −6°C for 1 d, followed by 25°C for 7 d. One data from two independent experiments with similar results was presented. B, Arabidopsis Col-0 (empty vector transformed) plants and CaPF1-expressing line 3 and line 8 plants were grown at 25°C, and the freezing tolerance of leaves was measured using the electrolyte leakage test. C, Same as B, except that plants were grown at 25°C followed by a 7-d cold acclimation at 4°C. Data are presented as means ± sd (n = 4). One out of three independent experiments with similar results is shown.

For the freezing tolerance test, transgenic (lines 3 and 8) and control Arabidopsis plants were grown in soil at 25°C for 3 weeks. Plants were transferred to −6°C for 24 h and returned to a 25°C growth chamber for 1 week. As a result of two independent experiments, 65% of CaPF1 transgenic Arabidopsis survived. In the same condition, only 17% of nontransgenic Arabidopsis survived (Fig. 8A). To quantify the increase in freezing tolerance, electrolyte leakage was measured following freezing treatment. Electrolyte leakage from frozen and thawed tissues is a sensitive indicator of loss of integrity of the plasmalemma and has been commonly used to assay freezing injury (for review, see Calkins and Swanson, 1990). The electrolyte leakage assay was applied to both nonacclimated and cold-acclimated leaf tissues of transgenic lines 3 and 8, those autoregulated PR and COR genes. The results indicated that the freezing tolerance of nonacclimated CaPF1-expressing Arabidopsis plants was slightly greater than that of nonacclimated control plants; nonacclimated control plants had an EL50 (temperature that caused a 50% leakage of electrolytes) of approximately −6°C, and the two CaPF1-expressing lines had EL50 values of approximately −7°C (Fig. 8B). The freezing tolerance of cold-acclimated CaPF1-expressing Arabidopsis plants was also greater than that of cold-acclimated control plants. CaPF1-expressing plants that had been cold acclimated for 7 d had EL50 values of approximately −9°C. The cold-acclimated control plants had EL50 values of approximately −7°C (Fig. 7C) under these particular conditions.

Figure 8.

Overexpression of CaPF1 in tobacco causes constitutive up-regulation of PR genes and bacterial pathogen tolerance. A, Expression analysis of PR genes in transgenic tobacco plants. The numbers indicate independent lines of transgenic T0 tobacco plants. C is pMBP-1 transformed control. B, Disease symptoms in tobacco (cv Xanthi nc) transformed with or without 35S:CaPF1 at 5 d postinoculation of P. syringae pv tabaci. Arrows highlight areas of P. syringae pv tabaci infection. Tobacco leaves carrying the 35S:CaPF1 (lines 2, 3, and 6) with mild disease symptoms compared with tobacco leaves carrying pMBP1 (Control). C, Inhibition of bacterial growth in transgenic tobacco plants. Two-month-old transgenic tobacco plants were syringe-infiltrated with 2 × 105 CFU/mL solution of P. syringae pv tabaci, and leaf bacterial numbers were determined at 0, 2, and 5 d after inoculation, respectively. Data are presented as means ± sd (n = 3). One data out of three independent experiments with similar results is shown.

These results indicate that overexpression of CaPF1 confers disease and freezing tolerance in transgenic plants, presumably via activation of the signaling pathway that involves the expression of PR and COR genes.

DISCUSSION

ERF factors are a subfamily of ERF/AP2 transcription factor that is only present in the plant kingdom. In Arabidopsis, 124 ERF proteins were annotated (Riechmann et al., 2000), and molecular genetic studies for unveiling the roles of this family of genes are actively performed in diverse aspects of biological phenomena. Recent studies revealed the role of some ERF proteins during abiotic stresses of plants (for review, see Kizis et al., 2001; Singh et al., 2002; Shinozaki et al., 2003). In this article, we describe the characterization of cDNA encoding a new pepper ERF, CaPF1, which binds to either GCC or CRT/DRE cis-elements. CaPF1 mRNA is induced by pathogen attack and cold stress. CaPF1-expressing transgenic Arabidopsis plants up-regulate various stress-responsive genes and exhibit tolerance against pathogen and freezing temperatures. These results may suggest that overexpression of the CaPF1 functions in heterologous plants as a transcription factor and alters the regulation of in vivo targets of its not yet defined ortholog in transgenic plants, and results in expression of biotic and abiotic stress-responsive genes.

CaPF1 Is a Novel Transcriptional Activator

CaPF1 contains a highly conserved ERF domain. However, outside the ERF domain, little sequence similarity exists between CaPF1 and other known ERF proteins (Fig. 2). In vitro sequence-specific DNA-binding activity of ERF domain-containing proteins is well documented. ERF proteins and Pti5 and 6 specifically interact with GCC boxes present in the promoter regions of PR genes (Ohme-Takagi and Shinshi, 1995; Zhou et al., 1997). DREB1, DREB2A, and CBF1 proteins bind to the CRT/DRE element containing the core sequence PuCCGAC (Liu et al., 1998). Minor differences in the surrounding common core target sequences of ERF and DREB proteins result in the regulation of distinct target genes (Sakuma et al., 2002). In this article, electrophoretic mobility shift assays with GCC or CRT/DRE cis-elements demonstrate that CaPF1 binds both sequences, and overexpression of CaPF1 in Arabidopsis induces constitutive expression of PR and COR genes (Figs. 4 and 5). One of the tobacco ERFs, Tsi1, could also bind both the GCC box and the CRT/DRE box. However, transgenic tobacco plants overexpressing Tsi1 did not show induced expression of rd29A, which contains a CRT/DRE box in its promoter region, under normal growth conditions (J.M. Park et al., 2001).

JERF1 (AY044235) and NtDRF1 (AY286010) have the most similarity in amino acid sequence of CaPF1 protein. Interestingly, the three ERFs (CaPF1, JERF1, and NtDRF1) contain a novel, highly conserved N-terminal motif of unknown function (MCGGAIISD; Fig. 2B). Tournier et al. (2003) isolated four new members of the ERF family from tomato (LeERF1–4), and phylogenetic analysis indicated that LeERF2 belongs to a new ERF class, which is characterized by a conserved N-terminal MCGGAII/L sequence. This N-terminal motif is only found in ERF genes, including AtEBP from Arabidopsis (Buttner and Singh, 1997) and OsEBP-89 from rice (Yang et al., 2002). Based on dual DNA-binding activities of the CaPF1 protein to both the GCC and CRT/DRE boxes and N-terminal MCGGAII/L signature sequence, we conclude that CaPF1 is a novel ERF protein.

CaPF1 Is Responsive to Various Stress Factors

ERF family of genes plays various roles in plant growth, development, and response to different environmental stress factors (Okamuro et al., 1997). The pepper ERF CaPF1 gene also responds to pathogen attack and various abiotic stresses (Figs. 1 and 3).

CaPF1 transcripts are up-regulated during an incompatible interaction between pepper and bacterial pathogens (Fig. 1). One possible role of CaPF1 in response to pathogens is the orchestration of the correct temporal response in defense-related gene expression. In plants, pathogen infection generates multiple defense-response signaling pathways. One is mediated by SA, which culminates in the activation of pathogenesis-related protein genes. Signaling through the synergistic action of JA and ET is also involved in stress responses of plants and operates in a SA-independent fashion. The JA/ET pathway involves the induction of PR3, PR4, and PDF1.2 (Moller and Chua, 1999). In our experiment, CaPF1 transcript level is not responsive to SA. However, ET or JA induces CaPF1 expression in pepper within 1 h of treatment (Fig. 3A), and elevated PDF1.2 and GST transcript levels were detected in CaPF1-overexpressing Arabidopsis (Fig. 5). These results indicate that CaPF1 may regulate defense-related genes, in part, through the JA/ET pathway.

The CaPF1 transcript level is not responsive to ABA (Fig. 3A), like other ERF/AP2-type transcription factors (Liu et al., 1998). Induction of several abiotic stress-inducible genes, such as rd29A and COR, is known to mediate by ABA-independent pathways (Yamaguchi-Shinozaki and Shinozaki, 1994; Shinozaki et al., 2003). Our study showed that the CaPF1 mRNA is induced by low temperature, mannitol, and high salt (Fig. 3B), and constitutive expression of CaPF1 in transgenic Arabidopsis plants results in enhancing the expression of rd29A and COR genes containing CRT/DRE (Fig. 5). These results indicate that CaPF1 may play a role in regulating COR class of genes through ABA-independent pathway. Taken together, our data suggest that CaPF1 is a multiple stress-responsive factor responding to both biotic and abiotic stressors, including pathogen, low temperature, salt, and water stress.

Overexpression of CaPF1 in Arabidopsis Confers Tolerance against Various Stresses

The hypothesis that CaPF1 may play a role in biotic/abiotic stress resistance in plants is supported by the results of CaPF1-overexpressing transgenic Arabidopsis and tobacco plants. Overexpression of CaPF1 resulted in constitutive overexpression of stress-related genes such as PR and COR and stress tolerance under normal growth condition. It has been reported that overexpression of the Pti4, an ERF/AP2-type factor of tomato, in Arabidopsis activated the expression of GCC box-containing PR genes and exhibited increased resistance against pathogens (Gu et al., 2002). Overexpression of DREB1A, a stress-inducible ERF/AP2-type transcription factor, was also shown to enhance tolerance to multiple abiotic stresses via expression of COR genes containing DRE/CRT in their promoter regions (Kasuga et al., 1999). To date, only one example of ERF/AP2-type factor was shown to confer tolerance to both pathogen and abiotic stress by overexpression of a single transcription factor. Overexpression of Tsi1, a tobacco ERF/AP2-type factor, in tobacco improved tolerance to salt and pathogens (J.M. Park et al., 2001). Tsi1 was also reported to have dual binding activities to GCC and DRE/CRT cis-acting elements. However, overexpression of the Tsi1 in tobacco resulted in enhanced expression of PR genes but not rd29A. In this study, we show that the pepper ERF/AP2-type factor can confer disease and freezing stress tolerances in transgenic plants with constitutive expression of both PR and COR genes.

Recent studies in molecular and genomic analyses on the complex cascades of gene expression in abiotic stress response identified specificity and cross-talk in stress signaling (Shinozaki and Yamaguchi-Shinozaki, 2000; Shinozaki et al., 2003). Using full-length cDNA microarray, Seki et al. (2001) found that many genes are induced by both drought and cold stress and suggest the existence of cross-talk between the drought and cold stress. In this study, we described elevated expression of PR and COR genes and enhanced tolerance to pathogen and freezing tolerance in an ERF protein overexpressor plant. This result together with others (J.M. Park et al., 2001) could be a starting point to study the cross-talk between biotic and abiotic stress-responsive gene expression in plants. Global gene expression study using CaPF1-overexpressing transgenic plants and transgenic approach using mutants in hormone signaling may provide new insight into the roles of CaPF1 in biotic and abiotic stress responses in plants.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Isolation of CaPF1 cDNA and Sequence Analysis

The hot pepper (Capsicum annuum) cDNA library was constructed from mRNA prepared from 8-week-old plants inoculated with Xanthomonas axonopodis pv glycines and screened with a random prime-labeled CaPF1 differential-display reverse transcription-PCR fragment (421 bp) as a probe. Plaques (5 × 104) were screened at 42°C using the hybridization and washing conditions described by Choi et al. (1996). The DNA sequences of CaPF1 cDNA clones were determined using standard procedures (Sambrook et al., 1989).

Plant Materials, Growth Conditions, and Treatment

Arabidopsis (ecotype Colombia) and tobacco plants (Nicotiana tabacum cv Xanthi nc) were grown in a chamber (16 h of light and 8 h of darkness at 25°C). For growth under sterile conditions, Arabidopsis and tobacco seeds were surface-sterilized with 70% ethanol for 15 min, washed three times in sterile water, and grown on Murashige and Skoog (DUCHEFA, Haarlem, The Netherlands) medium. To determine temporal expression of the CaPF1 gene during bacterial pathogen inoculation or chemical (ethephon, MJ, SA, and ABA) treatment, treated pepper leaf samples were collected as described in previous procedures (Lee et al., 2002). For pepper inoculation, 2 × 108 colony-forming units (CFU)/mL solutions of X. axonopodis pv glycines and Xanthomonas campestris pv vesicatoria race 3 were pressure-infiltrated into leaf tissues using a needleless syringe. For chemical treatment, SA and ethephon were dissolved in water at a concentration of 5 mm, and MJ was dissolved in 0.1% ethanol at a final concentration of 0.1 mm. The ABA stock solution was diluted to 0.1 mm with water and adjusted to pH 6.0 with 0.1 n HCl. Chemicals were sprayed onto mature leaves of pepper cv Bugang. Pepper plants were grown on autoclaved soil for 2 months and transferred to a cold chamber (4°C) or a flask filled with mannitol (0.4 m), NaCl (0.4 m) solutions for abiotic stress treatment (Kasuga et al., 1999; Chung et al., 2003). To monitor bacterial growth in Arabidopsis and tobacco, leaves were inoculated by syringe infiltration of a 2 × 105 CFU/mL suspension of Pseudomonas syringae pv tomato DC3000 and P. syringae pv tabaci (Thilmony et al., 1995). At indicated time points, samples were removed from leaves using a cork borer (1 cm in diameter) and macerated in a 1.5-mL microcentrifuge tube containing 200 μL of 10 mm MgCl2. Samples were diluted in 10 mm MgCl2 and plated on selective medium (Luria-Bertani containing 100 μg/mL rifampicin).

DNA and RNA Gel-Blot Analyses

Genomic DNA was isolated from mature leaves of pepper cv Bugang as described in a previous report (Choi et al., 1996). Genomic DNA samples (20 μg) were digested to completion with DraI, EcoRI, HindIII, or XbaI. Digested genomic DNA was separated by electrophoresis on a 0.8% agarose gel, denatured, and blotted onto a nylon membrane (Amersham Pharmacia, Uppsala). Southern blotting was performed as described previously (Church and Gilbert, 1984), and membranes were hybridized with the CaPF1 cDNA probe (full length or gene specific) labeled with [α-32P]dCTP. RNA was extracted from pepper or Arabidopsis plants, using the procedure of Yi et al. (1999). For northern-blot analyses, total RNA was separated on formaldehyde-containing agarose gels and blotted onto nylon membranes following standard procedures (Sambrook et al., 1989). Equal loading of RNA was verified by visualizing of rRNA following staining with ethidium bromide. Blots were hybridized with [α-32P]dCTP-labeled probes. Arabidopsis-specific probes were generated via PCR amplification with gene-specific primers: AtGST1 (1890155), 5′-GAGTTCTCATCGCTCTTCAC-3′, 5′-GGCTAGCTTAGCCTCTTCTT-3′; COR6.6 (X55053), 5′-AGTATATCGGATGCGGCAGT-3′, 5′-CAAACGTAGTACATCTAAAGGGAGAA-3′; COR47 (X90959), 5′-CGACGAGAAAGCAGAGGATT-3′, 5′-ATGTCCCACTCCCACATCAT-3′. The Arabidopsis RD29A, PDF1.2, and PR2 probes were synthesized as described earlier (Uknes et al., 1992; Penninckx et al., 1996; J.M. Park et al., 2001). All the amplified DNA fragments were cloned into a pGEM-T easy vector (Promega, Madison, WI), and partial DNA sequences were determined for confirmation of correct gene. Pepper cDNA probes (PR1, PR4, PinII, ACC oxidase, and dehydrin cDNA) and tobacco cDNA probes (PR2, 3, 4, and 5) used in this study were isolated previously from pepper and tobacco (Lee et al., 2002; Chung et al., 2003).

Preparation of Recombinant Proteins and Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assays

The coding region of CaPF1 was cloned into pMAL (New England Biolabs, Beverly, MA) and expressed in Escherichia coli BL21 cells (Amersham Pharmacia). A MBP-CaPF1 fusion protein was purified using amylose resin, according to the manufacturer's instructions (New England Biolabs).

For the electrophoretic mobility shift assay, both strands of the following oligonucleotides were synthesized for the GCC box (ATAAGAGCCGCCACTAAAAT; Ohme-Takagi and Shinshi, 1995) and CRT/DRE element (ATTTCATGGCCGACCTGGTTTTAAGCTTTT; Stockinger et al., 1997). Double-stranded oligonucleotides were labeled with 32P-γATP (5,000 Ci mmol−1; Amersham) by treatment with T4 polynucleotide kinase (Promega) and purified on Sephadex G-25 columns (Roche, Mannheim, Germany), according to manufacturer's instructions. Radioactive probes were incubated with 1 μg protein in 10 μL 1 x binding buffer (HEPES:KOH, pH 7.5, 25 mm/KCl, 40 mm/EDTA, 0.1 mm/glycerol, 10% DTT, 1 mm/PMSF, poly d(I.C.)/500 μg) for 20 min at room temperature before loading onto a 4% polyacrylamide gel. Electrophoresis was performed at 100 V at room temperature. For competition assays, the protein was incubated with cold probe for 15 min at room temperature, then incubated further 20 min after adding radioactive probe.

Plant Transformation

CaPF1 full-length cDNA was constructed into a polylinker site of a binary vector, pMBP-1, a derivative of pBI121, in the sense orientation. Constructs were introduced into Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain C58C1. Arabidopsis plants used for transformation were grown in 8-cm pots filled with soil at 25°C for 5 weeks and transformed by vacuum infiltration, as described by Bechtold and Pelletier (1998). Kanamycin-resistant T1 plants were selected by planting seeds on Murashige and Skoog medium supplemented with 100 μg/mL of kanamycin, and transferring KanR seedlings to soil. Homozygous lines for the transgene were identified in the T2 generation by segregation for kanamycin resistance and confirmed by genomic DNA gel-blot analyses. The same 35S:CaPF1 construct was also employed for tobacco transformation. Tobacco transformants were analyzed by genomic DNA gel-blot analyses with CaPF1-specific probe (250 bp) generated by PCR amplification with the gene-specific primers SP19F (5′-GGCTTTTGAATCCCAGATGA-3′) and SP19R (5′-ATAAGGGAAGGTGCGTGTTG-3′).

Electrolyte Leakage Measurement

Electrolyte leakage tests were performed essentially as described (Warren et al., 1996) with minor modifications. Five-week-old seedlings were incubated in growth chambers at either 25°C (for nonacclimated plants) or 4°C (for cold-acclimated plants). After 7 d, young leaves were harvested, washed, and 4 leaves per plant were placed in 5-mL aliquots of 0.4 m sorbitol (Sigma, St. Louis). Tubes were equilibrated to either −2°C or 0°C in a cooled incubator (MIR-153; Sanyo, Osaka), and allowed to remain there for 24 h. The cooled incubator temperature was then ramped down to −10°C at a rate of 2°C d−1. The cold-treated tubes were held at 4°C for 2 h and then warmed to room temperature. Electrical conductivity was measured (model 455C, Istek conductivity meter; Seoul, Korea), after which the tubes were autoclaved to release all electrolytes for the second determination of the total content of electrolytes in each sample.

Sequence data from this article have been deposited with the EMBL/GenBank data libraries under accession number AY246274.

This work was supported by grants from the Plant Diversity Research Center, Crop Functional Genomics Center of the 21st Century Frontier Research Program funded by the Ministry of Science and Technology and the Plant Molecular Genetics and Breeding Research Center through the Korea Science and Engineering Foundation.

Article, publication date, and citation information can be found at www.plantphysiol.org/cgi/doi/10.1104/pp.104.042903.

References

- Bechtold N, Pelletier G (1998) In planta Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of adult Arabidopsis thaliana plants by vacuum infiltration. Methods Mol Biol 82: 259–266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buttner M, Singh KB (1997) Arabidopsis thaliana ethylene-responsive element binding protein (AtEBP), an ethylene-inducible, GCC box DNA-binding protein interacts with an ocs element binding protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 94: 5961–5966 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calkins JB, Swanson BT (1990) The distinction between living and dead plant tissue-viability tests in cold hardiness research. Cryobiology 27: 194–211 [Google Scholar]

- Chen W, Provart NJ, Glazebrook J, Katagiri F, Chang HS, Eulgem T, Mauch F, Laun S, Zou G, Whitham SA, et al (2002) Expression profile matrix of Arabidopsis transcription factor genes suggests their putative functions in response to environmental stresses. Plant Cell 14: 559–574 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi D, Kim HM, Yun HK, Park JA, Kim WT, Bok SH (1996) Molecular cloning of a metallothionein-like gene from Nicotiana glutinosa L. and its induction by wounding and tobacco mosaic virus infection. Plant Physiol 112: 353–359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung E, Kim SY, Yi SY, Choi D (2003) Capsicum annuum dehydrin, an osmotic-stress gene in hot pepper plants. Mol Cells 15: 327–332 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Church GM, Gilbert W (1984) Genomic sequencing. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 81: 1991–1995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dingwall C, Laskey RA (1991) Nuclear targeting sequences—a consensus? Trends Biochem Sci 16: 478–481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durrant WE, Rowland O, Piedras P, Hammond-Kosack KE, Jones JDG (2000) cDNA-AFLP reveals a striking overlap in race-specific resistance and wound response gene expression profile. Plant Cell 12: 963–977 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujimoto SY, Ohta M, Usui A, Shinshi H, Ohme-Takagi M (2000) Arabidopsis ethylene responsive-element binding factors act as transcriptional activators or repressors of GCC box mediated gene expression. Plant Cell 12: 393–404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu YQ, Wildermuth MC, Chakravarthy S, Loh YT, Yang C, He X, Han Y, Martin GB (2002) Tomato transcription factors pti4, pti5, and pti6 activate defense responses when expressed in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 14: 817–831 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaglo-Ottosen KR, Gilmour SJ, Zarka DG, Schabenberger O, Thomashow MF (1998) Arabidopsis CBF1 overexpression induces COR genes and enhances freezing tolerance. Science 3: 104–106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasuga M, Liu Q, Miura S, Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K, Shinozaki K (1999) Improving plant drought, salt, and freezing tolerance by gene transfer of a single stress-inducible transcription factor. Nat Biotechnol 17: 287–291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kizis D, Lumbreras V, Pages M (2001) Role of AP2/EREBP transcription factors in gene regulation during abiotic stress. FEBS Lett 498: 187–189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SJ, Lee MY, Yi SY, Oh SK, Choi SH, Her NH, Choi D, Min BW, Yang SG, Harn CH (2002) PPI1: a novel pathogen-induced basic region-leucine zipper (bZIP) transcription factor from pepper. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 15: 540–548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li D, Xie B, Zhang B, Zhao K, Luo K (2000) The current problems and the solution for pepper disease-resistant gene engineering (in Chinese). Acta Hortic Sin 27(Suppl): 509–514 [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q, Kasuga M, Sakuma Y, Abe H, Miura S, Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K, Shinozaki K (1998) Two transcription factors, DERB1 and DREB2, with an EREBPERF/AP2 DNA binding domain separate two cellular signal transduction pathways in drought- and low-temperature-responsive gene expression, respectively, in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 10: 1391–1406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moller SG, Chua NH (1999) Interactions and intersections of plant signaling pathways. J Mol Biol 22: 219–234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohme-Takagi M, Shinshi H (1995) Ethylene inducible DNA binding proteins that interact with an ethylene-responsive element. Plant Cell 7: 173–182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamuro JK, Caster B, Villarroel R, Montagu M, Jofuku KD (1997) The AP2 domain of APETALA2 defines a large new family of DNA binding proteins in Arabidopsis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 94: 7076–7081 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park CJ, Shin R, Park JM, Lee GJ, Yoo TH, Paek KH (2001) A hot pepper cDNA encoding a pathogenesis-related protein 4 is induced during the resistance response to tobacco mosaic virus. Mol Cells 28: 122–127 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park JM, Park CJ, Lee SB, Ham BK, Shin R, Paek KH (2001) Overexpression of the tobacco Tsi1 gene encoding an EREBPERF/AP2-type transcription factor enhances resistance against pathogen attack and osmotic stress in tobacco. Plant Cell 13: 1035–1046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penninckx IA, Eggermont K, Terras FR, Thomma BP, De Samblanx GW, Buchala A, Metraux JP, Manners JM, Broekaert WF (1996) Pathogen-induced systemic activation of a plant defensin gene in Arabidopsis follows a salicylic acid-independent pathway. Plant Cell 8: 2309–2323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penninckx IA, Thomma BP, Buchaala A, Metraux JP, Broekaert WF (1998) Concomitant activation of jasmonate and ethylene response pathways is required for induction of a plant defensin gene in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 10: 2103–2113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richard S, Morency M-J, Drevet C, Jouanin L, Seguin A (2000) Isolation and characterization of a dehydrin gene from white spruce induced upon wounding, drought and cold stresses. Plant Mol Biol 43: 1–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riechmann JL, Martin JH, Leuber L, Jiang CZ, Keddie J, Adam L, Pineda O, Ratcliffe OJ, Samaha RR, Creelman R, et al (2000) Arabidopsis transcription factors: genome-wide comparative analysis among eukaryotes. Science 290: 2105–2110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rushton PJ, Somssich IE (1998) Transcriptional control of plant genes responsive to pathogens. Curr Opin Plant Biol 1: 311–315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakuma Y, Liu Q, Dubouzet JG, Abe H, Shinozaki K, Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K (2002) DNA-binding specificity of the ERF/AP2 domain of Arabidopsis DREBs, transcription factors involved in dehydration- and cold-inducible gene expression. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 25: 998–1009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook J, Fritrsch EF, Maniatis T (1989) Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual, Ed 2. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Plainview, NY

- Schenk PM, Kazan K, Wilson I, Anderson JP, Richmond T, Somerville SC, Manners JM (2000) Coordinated plant defense responses in Arabidopsis revealed by microarray analysis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97: 11655–11660 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seki M, Narusaka M, Abe H, Kasuga M, Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K, Carnici P, Hayashizaki Y, Shinozaki K (2001) Monitoring the expression pattern of 1300 Arabidopsis genes under drought and cold stress by using a full-length cDNA microarray. Plant Cell 13: 61–72 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinozaki K, Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K (2000) Molecular responses to dehydration and low temperature: differences and cross talk between two stress signaling pathways. Curr Opin Plant Biol 3: 217–223 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinozaki K, Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K, Seki M (2003) Regulatory network of gene expression in the drought and cold stress responses. Curr Opin Plant Biol 6: 410–417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh KB, Foley RC, Onate-Sanchez L (2002) Transcription factors in plant defense and stress responses. Curr Opin Plant Biol 5: 430–436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solano R, Stepanova A, Chao Q, Ecker JR (1998) Nuclear events in ethylene signaling: a transcriptional cascade mediated by ETHYLENE-INSENSITIVE3 and ETHYLENE-RESPONSE-FACTOR1. Genes Dev 12: 3703–3714 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stockinger EJ, Gilmour SJ, Thomashow MF (1997) Arabidopsis thaliana CBF1 encodes an AP2 domain-containing transcriptional activator that binds to the C-repeat/DRE, a cis-acting DNA regulatory element that simulates transcription in response to low temperature and water deficit. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 94: 1035–1040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thilmony RL, Chen Z, Bressan RA, Martin GB (1995) Expression of the tomato Pto gene in tobacco enhances resistance to Pseudomonas syringae pv. tabaci expressing avrPto. Plant Cell 7: 1529–1536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomashow MF (1999) Plant cold acclimation: freezing tolerance genes and regulatory mechanisms. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol 50: 571–599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tournier B, Sanchez-Ballesta MT, Jones B, Pesquet E, Regad F, Latche A, Pech JC, Bouzayen M (2003) New members of the tomato ERF family show specific expression pattern and diverse DNA-binding capacity to GCC box element. FEBS Lett 550: 149–154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uknes S, Mauch-Mani B, Moyer M, Potter S, Williams S, Dincher S, Chandler D, Slusarenko A, Ward E, Ryals J (1992) Acquired resistance in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 4: 645–656 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang KLC, Li H, Ecker JR (2002) Ethylene biosynthesis and signaling network. Plant Cell 14: S131–S151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warren G, McKown R, Marin AL, Teutonico R (1996) Isolation of mutations affecting the development of freezing tolerance in Arabidopsis thaliana (L.) Heynh. Plant Physiol 111: 1011–1019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu K, Tian L, Hollingworth J, Brown DC, Miki B (2002) Functional analysis of tomato Pti4 in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol 128: 30–37 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K, Shinozaki K (1994) A novel cis-acting element in an Arabidopsis gene is involved in responsiveness to drought, low-temperature, or high-salt stress. Plant Cell 6: 251–264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang HJ, Shen H, Chen L, Xing YY, Wang ZY, Zhang JL, Hong MM (2002) The OsEBP-89 gene of rice encodes a putative EREBP ERF transcription factor and is temporally expressed in developing endosperm and intercalary meristem. Plant Mol Biol 50: 379–391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y, Shash J, Klessig DF (1997) Signal perception and transduction in plant defense responses. Genes Dev 11: 1621–1639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yi SY, Yu SH, Choi D (1999) Molecular cloning of a catalase cDNA from Nicotiana glutinosa L. and its repression by tobacco mosaic virus infection. Mol Cells 30: 320–325 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou J, Goldsbrough PB (1993) An Arabidopsis gene with homology to glutathione S-transferases is regulated by ethylene. Plant Mol Biol 22: 517–523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou J, Tang X, Martin GB (1997) The Pto kinase conferring resistance to tomato bacterial speak disease interact with proteins that bind a cis-element of pathogenesis-related genes. EMBO J 16: 3207–3218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]