SUMMARY:

Adult-onset leukoencephalopathy with axonal spheroids and pigmented glia is a rare neurodegenerative disease resulting from mutations in the colony stimulating factor 1 receptor gene. Accurate diagnosis can be difficult because the associated clinical and MR imaging findings are nonspecific. We present 9 cases with intracranial calcifications distributed in 2 brain regions: the frontal white matter adjacent to the anterior horns of the lateral ventricles and the parietal subcortical white matter. Thin-section (1-mm) CT scans are particularly helpful in detection due to the small size of the calcifications. These calcifications had a symmetric “stepping stone appearance” in the frontal pericallosal regions, which was clearly visible on reconstructed sagittal CT images. Intrafamilial variability was seen in 2 of the families, and calcifications were seen at birth in a single individual. These characteristic calcification patterns may assist in making a correct diagnosis and may contribute to understanding of the pathogenesis of leukoencephalopathy.

Adult-onset leukoencephalopathy with axonal spheroids and pigmented glia (ALSP) is a rare inheritable neurodegenerative disease caused by a mutation in the colony stimulating factor 1 receptor (CSF1R) gene. Before discovery of the causative gene, the term “hereditary diffuse leukoencephalopathy with spheroids or pigmented orthochromatic leukodystrophy” was used to describe patients with the clinical and neuropathologic phenomena, which are now associated with ALSP. ALSP has been proposed to encompass both of these diseases because of the clinical and pathologic overlap between them1,2 and because CSF1R mutations have been identified in families with both of these diseases.3,4 Although ALSP may be observed anywhere in the world, it seems to be relatively common in Japan.5

The clinical presentation of ALSP is heterogeneous. Some patients show parkinsonian features,6 while others, particularly young women, are sometimes misdiagnosed as having multiple sclerosis.7,8 Imaging findings may be helpful to distinguish these differential diagnoses. Patients with ALSP have several characteristic white matter findings that can be seen on MR imaging, including patchy and later diffuse nonenhancing lesions predominantly in the frontal and parietal regions, a thinning of the corpus callosum accompanied by abnormal signal intensity, lesions in the pyramidal tracts, and foci of restricted diffusion on DWI, which persists at least for months.5,9–11 Patients can also show disproportionately large lateral ventricles for their age and cortical atrophy as the disease progresses. These findings are commonly seen in patients with ALSP but are not specific. Furthermore, calcifications in the white matter can be detected in some patients with ALSP by CT.5,12 However, the clinical significance and pathogenesis of the calcifications remain unclear. Here we describe 9 cases of ALSP with a characteristic distribution of white matter calcifications on head CT. These calcifications allow correct and timely diagnosis of ALSP.

Case Series

Clinical Presentations and Brain CT Findings

Due to the retrospective nature of the study, the acquisition criteria for the CT scans were variable. The sagittal and coronal images were reconstructed with MPR methods.

Case 1

A 37-year-old woman noticed that the slipper on her right foot came off while walking. She developed difficulties with writing and speaking, motor aphasia, general spasticity, gait disturbances, and increasing micturition frequency. She was diagnosed with MS and treated with steroid therapy and interferon β-1b without any benefit. The disease progressed rapidly. Cognitive impairment, tremor, and right-sided hemiconvulsion appeared; she required a gastrostomy due to severe dysphagia. She was bedridden at 41 years of age. Her family history was not notable.

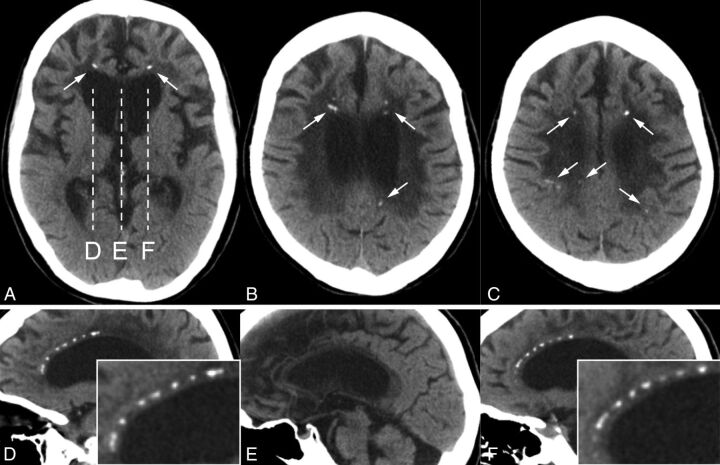

A brain CT scan showed punctate calcifications in the frontal and parietal subcortical white matter bilaterally (Fig 1A–C). On sagittal images, these calcifications had a symmetric “stepping stone appearance” in the frontal pericallosal regions (Fig 1D–F).

Fig 1.

A–C, Case 1. Small bilateral calcifications in the frontal and parietal subcortical white matter on axial CT images (arrows). D–F, Sagittal CT images corresponding to the dashes in A show pericallosal calcifications. Note that these calcifications symmetrically aligned with the upper edges of the lateral ventricles have a stepping stone appearance (enlarged images are inserted); no calcifications are seen in the midline (E).

Case 2

A 30-year-old woman initially presented with gait disturbances followed by cognitive impairment and personality changes, which rapidly progressed. A year later, she had severe dementia. She was found to have total aphasia, indifference, abnormal eating behavior, hyperreflexia, and ataxic gait. A demyelinating disorder was suspected; steroid therapy resulted in no benefit. None of her family members had any similar symptoms.

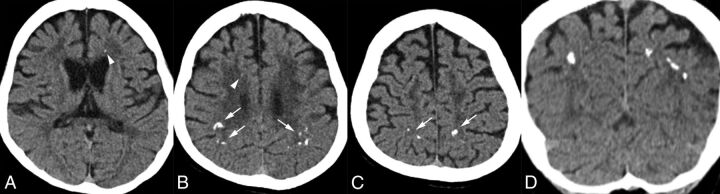

A CT scan showed brain calcifications predominantly in the bilateral parietal subcortical white matter (Fig 2A–C). Some of them appeared to be located in the cortex on axial images; however, they could definitely be seen in the white matter on coronal images (Fig 2D). She also had very small bilateral calcifications in the frontal white matter.

Fig 2.

A–C, Case 2. Bilateral, scattered calcifications in the parietal subcortical white matter on axial CT images (arrows in B and C). There are also very tiny calcifications in the bilateral frontal white matter (arrowheads in A and B). D, Coronal CT imaging reveals that the parietal calcifications are located in the subcortical white matter, not in the cortex.

Cases 3 and 4

A 27-year-old woman had difficulty releasing items she was holding in her left hand. Subsequently, she developed gait disturbances, tremor, micrographia, postural instability, urge incontinence, and constipation. She was euphoric and had frontal lobe dysfunction. She also had apraxia, left alien hand syndrome, forced grasping, and spastic gait by 28 years of age. She was treated with steroid therapy, which did not benefit her condition.

Her father (case 4) insidiously developed cognitive impairment and personality changes around 58 years of age. He became irritable and could not do simple calculations or 2 different tasks at the same time. He did not think that his daughter's condition was serious. He mainly had cognitive and frontal lobe dysfunctions. He did not have any parkinsonian symptoms, but he did have truncal imbalance and hyperreflexia in his lower limbs.

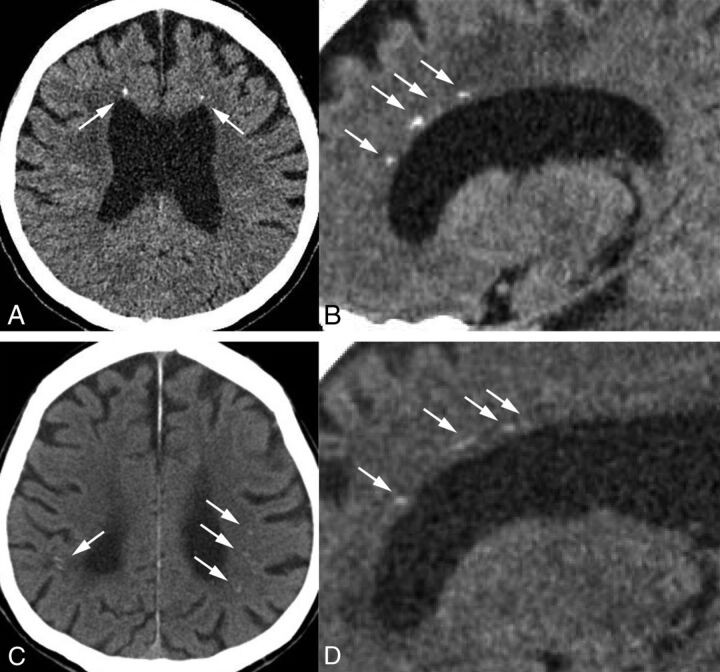

A brain CT scan of case 3 showed bilateral punctate calcifications in the frontal white matter adjacent to the anterior horns of the lateral ventricles (Fig 3A). On sagittal CT images, these calcifications had a characteristic symmetric stepping stone appearance (Fig 3B). The brain CT scan of case 4 displayed small bilateral calcifications in the parietal subcortical white matter, but we could not see any frontal calcifications on 4-mm-thick axial images (Fig 3C). However, on the 1-mm-thick sagittal images, we observed the characteristic stepping stone appearance of calcifications on the anterior part of pericallosal regions (Fig 3D).

Fig 3.

A, Case 3. Small bilateral calcifications in the frontal white matter adjacent to the anterior horns of the lateral ventricles on an axial CT image (arrows). B, Sagittal view represents the symmetric and characteristic stepping stone appearance (arrows). C, Case 4. Small bilateral calcifications in the parietal subcortical white matter on an axial CT image (arrows), but there are no calcifications in the frontal area. D, Sagittal CT image displays subtle calcifications in the anterior pericallosal region bilaterally (arrows).

Case 5

The clinical and MR imaging findings of case 5 have already been reported.3,10 In brief, this woman exhibited cognitive decline, psychiatric symptoms, apraxia, and spastic-ataxic gait impairment when she was 24 years of age. She was born prematurely but had essentially normal development until disease onset. She had no family history of neurodegenerative disease.

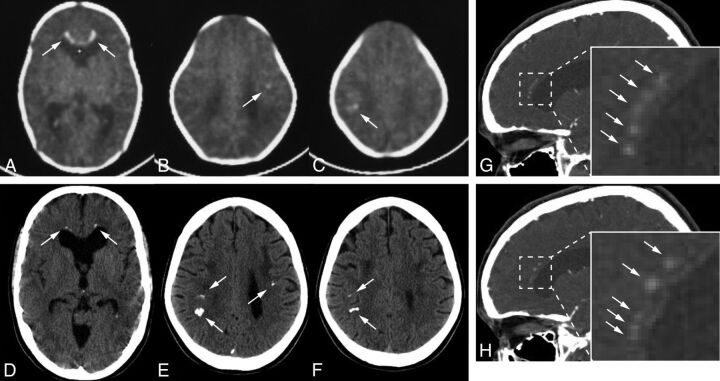

Several calcified lesions were detected in the frontal and parietal white matter on a CT scan obtained 1 month after birth (Fig 4A–C). Toxoplasmosis, Other agents, Rubella (also known as German measles), Cytomegalovirus, and Herpes simplex (TORCH) syndrome had been suspected at that time, but she had not been definitively diagnosed. The calcifications remained visible when she was 24 years of age (Fig 4D–H). Most interesting, some of them, especially the ones in the frontal white matter, seemed to have decreased in size. The calcifications were symmetric and had the characteristic stepping stone appearance on sagittal imaging (Fig 4G, -H).

Fig 4.

A–C, Case 5. Axial CT images at 1 month after birth show bilateral frontal and parietal calcifications (arrows). D–F, These calcifications still exist when the patient is 24 years of age, but they are somewhat smaller, especially those in the frontal regions (arrows). The white cursor inside the anterior horn is included (A) because this is a captured image. G and H, Sagittal views show symmetric frontal pericallosal calcifications in the characteristic stepping stone appearance (arrows; enlarged images in the inserts: G is the right hemisphere, and H is the left hemisphere).

Case 6

This case has been included in previous reports.3,6,9 The female patient exhibited cognitive impairment and depression from 18 years of age. Subsequently, parkinsonian signs such as hypomimia, bradykinesia, and rigidity developed. Her symptoms gradually worsened. Her mother, who died at the 30 years of age, had similar symptoms and seizures. The mother was diagnosed as having ALSP by postmortem examination.

Small calcifications were observed bilaterally in the frontal white matter on CT (On-line Fig 1A, -B). The stepping stone appearance was seen on the sagittal view (On-line Fig 1C, -D).

Cases 7 and 8

Some of the clinical findings of case 7 have been previously reported.3,6,12 The male patient's initial symptoms were forgetfulness and difficulty finding words at 58 years of age. His cognitive function deteriorated rapidly. He had depression, apraxia, aphasia, agraphia, parkinsonian symptoms, hyperreflexia, myoclonus, seizure, and urinary incontinence during his disease course. He died at 62 years of age and was diagnosed as having ALSP by postmortem examination and genetic testing.

It was previously reported that there was no evidence of brain calcifications on either CT scans or pathologic analysis.12 However, when his brain CT images were reviewed, we identified extremely small calcifications in the bilateral frontal white matter (On-line Fig 2A).

His sister (case 8), whose clinical features have also been previously reported,11 had genetically confirmed ALSP and brain calcifications. Her calcifications were scattered and distributed predominantly in the parietal subcortical white matter, particularly on the right side.12 There was clear intrafamilial variability of the pattern of calcifications.

Case 9

A 67-year-old man initially presented with balance difficulties and multiple falls at 57 years of age. Cognitive impairment and speech problems began around 63 years of age. On neurologic examination, he showed ideomotor apraxia, vertical gaze limitations, frequent stammer, dysarthria, dysphagia, unusual flexor posturing of his fingers and wrists, reduced arm swing, diffuse rigidity, subtle action tremor in his right upper arm, difficulty in initiating gait, small steps with postural instability, and urinary incontinence. In addition, he had depression with occasional suicidal thoughts. He was clinically suspected of having corticobasal syndrome. He died at 68 years of age. Postmortem findings were comparable with those for ALSP.

The brain CT showed very small bilateral calcifications in the frontal white matter adjacent to the anterior horns (On-line Fig 2B–D). This case only had axial images available, and we could not identify any parietal calcifications on the available 3-mm axial images.

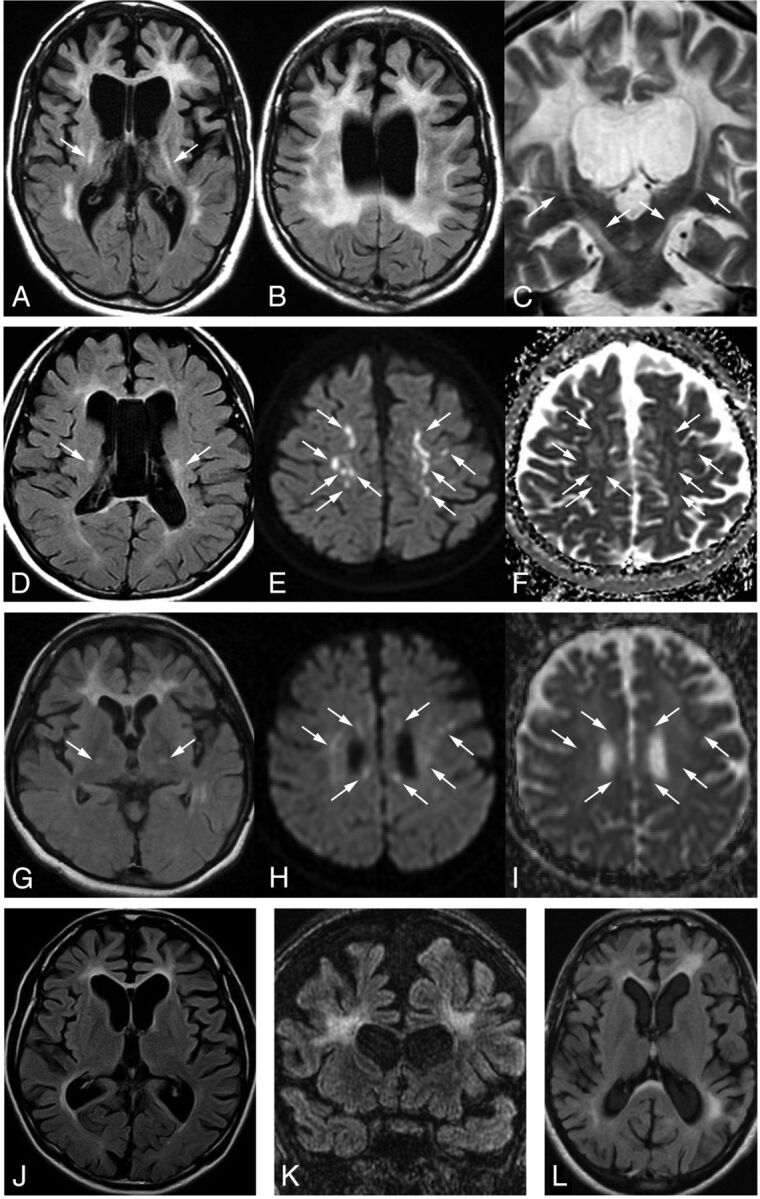

Brain MR Images

Although the degree of lesions was variable for each case, all except 1 case (case 9) showed typical findings consistent with ALSP (Fig 5). The MR images of cases 5 and 6 have been presented previously.9,10 Unfortunately, we did not have MR images of case 9. Of note, there was intrafamilial variability between cases 3 and 4. The calcifications in cases 2, 3, and 6 were not apparently recognized by T2* at 5-mm section thickness.

Fig 5.

A–C, Case 1. Typical white matter changes involving the corpus callosum and the pyramidal tracts (A and C, arrows), dilation of the lateral ventricles and cortical atrophy seen on FLAIR axial (A and B) and T2-weighted coronal imaging (C). D–F, Case 2. Abnormal signaling in the white matter, corpus callosum, and bilateral pyramidal tracts (D, arrows) and enlargement of the lateral ventricles on FLAIR (D). Several diffusion-restricted lesions with low ADC values in the white matter on DWI (E, arrows) and ADC maps (F, arrows). G–I, Case 3. FLAIR image shows frontal-dominant white matter changes bilaterally as well as in the internal capsules (G, arrows). The genu of the corpus callosum is also involved. Several diffusion-restricted lesions in the subcortical white matter can be seen around the lateral ventricles on DWI (H, arrows). These lesions demonstrate decreased signals on ADC maps (I, arrows). J, Case 4. The severity of the white matter changes is less evident than in case 3, the daughter of case 4, on the FLAIR axial image. K, Case 6. Bifrontal white matter lesions, thinning of the corpus callosum, dilation of the lateral ventricles, and cortical atrophy on FLAIR coronal image. L, Case 7. Left-side predominant white matter changes in the frontal and parietal regions and involvement in the corpus callosum on a FLAIR axial image.

Genetic and Functional Analyses of CSF1R

All genetic studies were conducted with approval by the institutional review board of Niigata University School of Medicine and Mayo Clinic Florida. We identified 3 novel heterozygous mutations in 4 cases (Table): 2 missense mutations, p.Gly589Arg (case 1) and p.Ala652Pro (case 2), and 1 splice-site mutation, c.2442+5G>A (cases 3 and 4). The mutations in cases 5, 6, 7, and 8 have already been reported elsewhere, c.2442+5G>C (case 5), p.Met766Thr (case 6), and p.Gly589Glu (cases 7 and 8).3 We could not analyze case 9 because the samples were not available.

Case series of ALSP with brain calcifications

| Case | Sex | CSF1R Mutation | Origin | FH | Age at Onset (yr) | Age at CT (yr) | Section Thickness (mm) | Location of Calcifications |

Stepping Stone Appearance on Sagittal CT | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frontal | Parietal | |||||||||

| 1 | F | c.1765G>A/p.G589Ra | Japan | − | 37 | 44 | 5 | + | + | + |

| 2 | F | c.1954G>C/p.A652Pa | Japan | − | 30 | 31 | 2 | + | + | NA |

| 3 | F | c.2442+5G>Aa | Japan | + | 27 | 28 | 1 | + | − | + |

| 4 | M | c.2442+5G>Aa | Japan | + | 58 | 61 | 4 (1)c | + | + | + |

| 5 | F | c.2442+5G>C | US | − | 23 | 0, 24 | 6, 5 | + | + | + |

| 6 | F | c.2297T>C/p.M766T | US | + | 18 | 30 | 1.3 (1)c | + | − | + |

| 7 | M | c.1766G>A/p.G589E | US | + | 58 | 60 | 3 | + | − | NA |

| 8 | F | c.1766G>A/p.G589E | US | + | 47 | 52 | 7 | + | + | NA |

| 9 | M | Untestedb | US | − | 57 | 67 | 3 | + | − | NA |

Note:—FH indicates family history; NA, not available for sagittal images.

Novel mutations.

This case was diagnosed by pathologic analysis. We could not conduct genetic testing because of a lack of samples.

For axial images, 4 or 1.3 mm and 1 mm for reconstructed sagittal images.

We also showed that the novel missense mutant CSF1Rs were not autophosphorylated after treatment with CSF1R ligands (colony stimulating factor 1 and interleukin-34) and that abnormal splicing was induced by the novel splice-site mutation by using functional and splicing assays as previously described (On-line Fig 3).5 A subcloning analysis revealed that these aberrant splice variants were identical to those of a previously reported case carrying a c.2442+1G>T.5

Discussion

While most genetic and metabolic brain calcifications are usually observed in the basal ganglia, thalamus, and cerebellum,13,14 these regions are not typically affected in ALSP. The calcifications seen in these 9 cases of ALSP were distributed mainly in 2 regions: the frontal white matter adjacent to the anterior horns of the lateral ventricles as described previously5 (all cases) and the parietal subcortical white matter (cases 1, 2, 4, 5, and 8). Parietal calcifications were larger than frontal calcifications in some cases (cases 2, 5). The calcifications were usually symmetric, but some level of laterality may exist. The calcifications could often be overlooked because they were extremely small; thus, thin-section CT scans would be preferable for detecting them. Indeed, no calcifications were identified during the initial evaluation of cases 7 and 9. In addition, calcifications were not identified at 4-mm section thickness, but they were visible on 1-mm sections in a previously reported case.5 MRI T2* and/or susceptibility-weighted images that are calcium-sensitive can be used as an alternative to CT scans, but T2* imaging apparently failed to detect the calcifications in cases 2, 3, and 6, probably because of the section thickness. Given that relatively young female patients tended to be misdiagnosed as having demyelinating disorders, such as MS (cases 1–3), brain CT scans could be useful for the differential diagnosis.

The appearance of the frontal calcifications can be clearly demonstrated on the reconstructed sagittal view. They had a stepping stone appearance (Figs 1, 3, 4, and On-line Fig 1). Most interesting, they seemed to line up along a structure running anterior to posterior through the pericallosal region of the brain. While brain calcifications in other diseases often were observed in small vessels,15,16 there was no evidence of an association between these calcifications and the vessels in 1 postmortem case.5

There was phenotypic variability seen in the families with c.2442+5G>A and p.Gly589Glu mutations. In the family with the c.2442+5G>A mutation, case 3 showed a young-onset spastic gait and fewer cognitive deficits in the early disease course, while her father (case 4) presented with dementia as an initial symptom at 58 years of age. Not only the MR imaging findings (Fig 5) but also the predominant area of calcifications was also different in both cases (Fig 3). However, the degree of aberrant splicing was not apparently different in the 2 cases (On-line Fig 3). In the family with the p.Gly589Glu mutation, case 7 mainly presented with cognitive decline, but pyramidal dysfunction was the most prominent feature in his sister. In addition, her disease began >10 years earlier than his.12 The distribution of calcifications also differed. These findings suggest that the phenotype might be determined by not only a CSF1R mutation but potentially other genetic, environmental, or biologic factors, such as sex.

The most interesting finding was that case 5 had calcifications present at birth. This case indicated that ALSP should be considered in the differential diagnosis for TORCH syndrome. Furthermore, some of these calcifications seemed to decrease in size as she grew older. Given that the CSF1R is required for microglial differentiation, proliferation, and migration into the brain during embryogenesis,17 a loss of function of CSF1R due to a CSF1R mutation might induce developmental problems in the microglia. In the fetal brain, microglia are clustered in the frontal crossroads that intersect callosal, associative, and thalamocortical fibers.18,19 These microglia organize axonal projections in the prospective white matter.18 This microglial accumulation spreads along the rostocaudal axis above the immature anterior horn of the lateral ventricles.18,19 Because these embryonic microglial distributions are similar to those of the calcifications presented here, we assume that microglial dysfunction has a causal relationship with the development of calcifications. In addition, microglial dysfunction might lead to incomplete white matter integrity. However, the patients who had CSF1R mutations were asymptomatic until they were adults. This finding suggests that the residual wild-type CSF1R should be sufficient for function until adulthood. It also suggests that neurodegeneration of the white matter may insidiously begin and progress, but symptom onset may not occur until the middle of life. Indeed, white matter changes have been observed in elderly asymptomatic mutation carriers.20,21 Additionally, the calcifications may diminish while white matter pathology progresses. However, to elucidate the mechanism by which CSF1R mutations cause such unique calcifications, further investigation is still required.

Conclusions

We demonstrated a characteristic distribution of intracranial calcifications in 9 cases of ALSP. The unique distribution of the calcifications may make it possible to diagnose ALSP correctly.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Ms Kelly Viola, ELS, for her assistance with the technical preparation of this manuscript.

ABBREVIATIONS:

- ALSP

adult-onset leukoencephalopathy with axonal spheroids and pigmented glia

- CSF1R

colony stimulating factor 1 receptor

- TORCH syndrome

Toxoplasmosis, Other agents, Rubella, Cytomegalovirus, and Herpes simplex

Footnotes

Disclosures: Takuya Konno—OTHER: Received research support from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science Postdoctoral Fellowships for Research Abroad and is partially supported by a gift from Carl Edward Bolch Jr, and Susan Bass Bolch. B. Mark Keegan—UNRELATED: Grants/Grants Pending: Terumo BCT*; Payment for Development of Educational Presentations: American Academy of Neurology, Consortium of MS Centers meeting. Masatoyo Nishizawa—UNRELATED: Consultancy: Kissei Pharmaceuticals, Comments: an adviser for the development of a new disease-modifying drug for cerebellar ataxia; OTHER: supported by Grants-in-Aid (A) for Scientific Research from Japan Society of Promotion of Science and a grant-in-aid from the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, Japan. Zbigniew K. Wszolek—RELATED: Grant: National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke P50 NS072187; UNRELATED: Grants/Grants Pending: National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Aging (primary) and National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (secondary) 1U01AG045390-01A1, Mayo Clinic Center for Regenerative Medicine, Mayo Clinic Center for Individualized Medicine, Mayo Clinic Neuroscience Focused Research Team (Cecilia and Dan Carmichael Family Foundation and the James C. and Sarah K. Kennedy Fund for Neurodegenerative Disease Research at Mayo Clinic in Florida), and The Sol Goldman Charitable Trust; Employment: Mayo Clinic Foundation (salary); Patents (planned, pending or issued): Mayo Clinic and I have a financial interest in technologies entitled “Identification of Mutations in PARK8, a Locus for Familial Parkinson's Disease” and “Identification of a Novel LRRK2 Mutation, 6055G>A (G2019S), Linked to Autosomal Dominant Parkinsonism in Families from Several European Populations”; these technologies have been licensed to a commercial entity, and to date, I have received royalties of <$1500 through Mayo Clinic in accordance with its royalty-sharing policies.* Takeshi Ikeuchi—RELATED: Grant: grants from the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare,* and KAKENHI (26117506 and H16H01331), a grant-in-aid from the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan, and a grant-in-aid from Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development. *Money paid to the institution.

Author Contributions: Takuya Konno: drafting the manuscript; design and conceptualization of the study; acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and final approval of the manuscript. Daniel F. Broderick: reviewing the manuscript, conceptualization of the study, acquisition and interpretation of the data, and final approval of the manuscript. Naomi Mezaki: reviewing the manuscript, acquisition and analysis of the data, and final approval of the manuscript. Aiko Isami: reviewing the manuscript, acquisition and analysis of the data, and final approval of the manuscript. Daita Kaneda: reviewing the manuscript, acquisition of the data, and final approval of the manuscript. Yuichi Tashiro: reviewing the manuscript, acquisition of the data, and final approval of the manuscript. Takayoshi Tokutake: reviewing the manuscript, acquisition of the data, and final approval of the manuscript. B. Mark Keegan: reviewing the manuscript, acquisition of the data, and final approval of the manuscript. Bryan K. Woodruff: reviewing the manuscript, acquisition of the data, and final approval of the manuscript. Takeshi Miura: reviewing the manuscript, acquisition of the data, and final approval of the manuscript. Hiroaki Nozaki: reviewing the manuscript, acquisition of the data, and final approval of the manuscript. Masatoyo Nishizawa: reviewing the manuscript, conceptualization of the study, interpretation of the data, and final approval of the manuscript. Osamu Onodera: reviewing the manuscript, conceptualization of the study, interpretation of the data, and final approval of the manuscript. Zbigniew K. Wszolek: reviewing the manuscript, conceptualization of the study, interpretation of the data, and final approval of the manuscript. Takeshi Ikeuchi: reviewing the manuscript, design and conceptualization of the study, interpretation of the data, and final approval of the manuscript.

This study was supported by a grant from the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, and Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (26117506 and 16H01331), Japan, and was partially supported by the National Institutes of Health grant P50 NS072187.

Paper previously presented in the form of poster at: Keystone Symposia, June 14, 2016; Keystone, Colorado.

References

- 1. Marotti JD, Tobias S, Fratkin JD, et al. Adult onset leukodystrophy with neuroaxonal spheroids and pigmented glia: report of a family, historical perspective, and review of the literature. Acta Neuropathol 2004;107:481–88 10.1007/s00401-004-0847-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Wider C, Van Gerpen JA, DeArmond S, et al. Leukoencephalopathy with spheroids (HDLS) and pigmentary leukodystrophy (POLD): a single entity? Neurology 2009;72:1953–59 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181a826c0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Rademakers R, Baker M, Nicholson AM, et al. Mutations in the colony stimulating factor 1 receptor (CSF1R) gene cause hereditary diffuse leukoencephalopathy with spheroids. Nat Genet 2012;44:200–05 10.1038/ng.1027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Nicholson AM, Baker MC, Finch NA, et al. CSF1R mutations link POLD and HDLS as a single disease entity. Neurology 2013;80:1033–40 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31828726a7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Konno T, Tada M, Tada M, et al. Haploinsufficiency of CSF-1R and clinicopathologic characterization in patients with HDLS. Neurology 2014;82:139–48 10.1212/WNL.0000000000000046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sundal C, Fujioka S, Van Gerpen JA, et al. Parkinsonian features in hereditary diffuse leukoencephalopathy with spheroids (HDLS) and CSF1R mutations. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2013;19:869–77 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2013.05.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Saitoh BY, Yamasaki R, Hayashi S, et al. A case of hereditary diffuse leukoencephalopathy with axonal spheroids caused by a de novo mutation in CSF1R masquerading as primary progressive multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler 2013;19:1367–70 10.1177/1352458513489854 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Granberg T, Hashim F, Andersen O, et al. Hereditary diffuse leukoencephalopathy with spheroids: a volumetric and radiological comparison with multiple sclerosis patients and healthy controls. Eur J Neurol 2016;23:817–22 10.1111/ene.12948 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sundal C, Van Gerpen JA, Nicholson AM, et al. MRI characteristics and scoring in HDLS due to CSF1R gene mutations. Neurology 2012;79:566–74 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318263575a [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Mateen FJ, Keegan BM, Krecke K, et al. Sporadic leucodystrophy with neuroaxonal spheroids: persistence of DWI changes and neurocognitive profiles: a case study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2010;81:619–22 10.1136/jnnp.2008.169243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bender B, Klose U, Lindig T, et al. Imaging features in conventional MRI, spectroscopy and diffusion weighted images of hereditary diffuse leukoencephalopathy with axonal spheroids (HDLS). J Neurol 2014;261:2351–59 10.1007/s00415-014-7509-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Fujioka S, Broderick DF, Sundal C, et al. An adult-onset leukoencephalopathy with axonal spheroids and pigmented glia accompanied by brain calcifications: a case report and a literature review of brain calcifications disorders. J Neurol 2013;260:2665–68 10.1007/s00415-013-7093-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Klünemann HH, Ridha BH, Magy L, et al. The genetic causes of basal ganglia calcification, dementia, and bone cysts: DAP12 and TREM2. Neurology 2005;64:1502–07 10.1212/01.WNL.0000160304.00003.CA [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Baba Y, Broderick DF, Uitti RJ, et al. Heredofamilial brain calcinosis syndrome. Mayo Clin Proc 2005;80:641–51 10.4065/80.5.641 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Linnankivi T, Valanne L, Paetau A, et al. Cerebroretinal microangiopathy with calcifications and cysts. Neurology 2006;67:1437–43 10.1212/01.wnl.0000236999.63933.b0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Miklossy J, Mackenzie IR, Dorovini-Zis K, et al. Severe vascular disturbance in a case of familial brain calcinosis. Acta Neuropathol 2005;109:643–53 10.1007/s00401-005-1007-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Saijo K, Glass CK. Microglial cell origin and phenotypes in health and disease. Nat Rev Immunol 2011;11:775–87 10.1038/nri3086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Judas M, Rados M, Jovanov-Milosevic N, et al. Structural, immunocytochemical, and MR imaging properties of periventricular crossroads of growing cortical pathways in preterm infants. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2005;26:2671–84 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Monier A, Adle-Biassette H, Delezoide AL, et al. Entry and distribution of microglial cells in human embryonic and fetal cerebral cortex. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 2007;66:372–82 10.1097/nen.0b013e3180517b46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Karle KN, Biskup S, Schüle R, et al. De novo mutations in hereditary diffuse leukoencephalopathy with axonal spheroids (HDLS). Neurology 2013;81:2039–44 10.1212/01.wnl.0000436945.01023.ac [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. La Piana R, Webber A, Guiot MC, et al. A novel mutation in the CSF1R gene causes a variable leukoencephalopathy with spheroids. Neurogenetics 2014;15:289–94 10.1007/s10048-014-0413-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.