Abstract

Aggregation of amyloid-β (Aβ) peptides into fibrils or other self-assembled states is central to Alzheimer’s disease (AD) pathogenesis. Fibrils formed in vitro by 40- and 42-residue Aβ peptides (Aβ40 and Aβ42) are polymorphic, with variations in molecular structure that depend on fibril growth conditions.1–12 Recent experiments1,13–16 suggest that variations in Aβ fibril structure in vivo may correlate with variations in AD phenotype, in analogy to distinct prion strains that are associated with distinct clinical and pathological phenotypes.17–19 Here we have investigated correlations between structural variation and AD phenotype using solid state nuclear magnetic resonance (ssNMR) measurements on Aβ40 and Aβ42 fibrils prepared by seeded growth from extracts of AD brain cortex. We compared two atypical AD clinical subtypes, rapidly progressive AD (r-AD) and the posterior cortical atrophy variant (PCA-AD), with typical prolonged duration AD (t-AD). Based on ssNMR data from 37 cortical tissue samples from 18 individuals, we find that a single Aβ40 fibril structure is most abundant in samples from t-AD and PCA-AD patients, while Aβ40 fibrils from r-AD samples exhibit a significantly greater proportion of additional structures. Data for Aβ42 fibrils indicate structural heterogeneity in most samples from all patient categories, with at least two prevalent structures. These results demonstrate the existence of a specific predominant Aβ40 fibril structure in t-AD and PCA-AD, suggest that r-AD may relate to additional fibril structures, and suggest a qualitative difference between Aβ40 and Aβ42 aggregates in AD brain tissue.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, prion strain, amyloid structure, polymorphism, solid state NMR

Evidence that Aβ fibril polymorphism may correlate with variations in clinical and pathological features of AD includes: (i) Aβ40 fibrils with different molecular structures exhibit different levels of toxicity in primary neuronal cell cultures1; (ii) Patterns of amyloid deposition in transgenic mice, induced by exogenous amyloid-containing biological material, vary with the source of this material13,14; (iii) The size and composition of amyloid plaques induced in transgenic mice by synthetic Aβ42 fibrils depend on the morphology and growth conditions of these fibrils15; (iv) Size distributions and resistance to chemical denaturation of Aβ42 aggregates in brain tissue differ in rapidly progressing and slowly progressing AD patients.16 Improved characterization of the structures of neurotoxic Aβ assemblies in AD and of correlations between structure and disease phenotype would have a major impact on our understanding of pathogenesis, on the development of appropriate diagnostic and therapeutic biomarkers, and on drug development.

Data from ssNMR are particularly sensitive to structural variations, allowing two-dimensional (2D) 13C-13C and 15N-13C ssNMR spectra to be used as “fingerprints” of specific fibril polymorphs.1,4,20,21 Since ssNMR requires milligram-scale quantities of isotopically labeled fibrils, we amplified and labeled structures in brain tissue by seeded growth, using brain tissue as the source of fibril seeds, as described by Lu et al.4

By analogy with prion diseases, in which different strains produce different durations of illness, preferentially target different brain regions, and are associated with conformational differences in disease-related prion proteins17–19,22, we selected tissue samples from patients from two unusual AD subtypes, namely PCA-AD, which is associated with disruption of visual processing23, and r-AD, in which neurodegeneration occurs within months and which clinically resembles Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease.24 We also included tissue from three individuals who died without dementia (ND) but who were found to have Aβ deposition at autopsy.

We separately prepared Aβ40 and Aβ42 fibrils by seeded growth from amyloid-enriched cortical extracts. Transmission electron microscope (TEM) images were acquired for all fibril samples. ssNMR measurements were attempted for all samples, although in some cases the signal-to-noise ratios were insufficient for acquisition or subsequent analysis of 2D spectra. Table 1 summarizes the tissue samples, patient categories, and ssNMR measurements. Examples of TEM images and full sets of 2D spectra are given in Extended Data Figs. 1–3. Control experiments with cortical extract from a non-AD patient who did not have significant Aβ deposition are described in the Supplementary Discussion and Extended Data Fig. 4.

Table 1.

Summary of brain tissue samples and 2D ssNMR data.

| patient | gender | age at clinical onset* | clinical duration | sample† | cortical region | Aβ40 13C-13C‡ | Aβ40 15N-13C | Aβ42 13C-13C | Aβ42 15N-13C |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| t-AD1 | female | 65 | 11 y | t-AD1f | frontal | X | X | X | X |

| t-AD1o | occipital | X | X | w | n | ||||

| t-AD1p | parietal | X | X | X | X | ||||

| t-AD2 | male | 64 | 13 y | t-AD2f | frontal | X | X | X | X |

| t-AD2o | occipital | w | w | X | X | ||||

| t-AD2p | parietal | X | X | w | n | ||||

| t-AD3 | male | 57 | 7 y | t-AD3f | frontal | X | X | X | X |

| t-AD3o | occipital | X | X | X | X | ||||

| t-AD3o′ | occipital | X | X | n | n | ||||

| t-AD3p | parietal | X | w | X | X | ||||

| t-AD3p′ | parietal | X | X | n | n | ||||

| t-AD4 | female | 51 | 11 y | t-AD4f | frontal | X | X | w | n |

| t-AD5 | female | 65 | 5 y | t-AD5f | frontal | X | X | w | n |

| t-AD6 | female | 58 | 21 y | t-AD6f | frontal | X | X | w | w |

| PCA-AD1 | male | 55 | 9 y | PCA1f | frontal | X | w | X | X |

| PCA1o | occipital | X | X | X | n | ||||

| PCA1p | parietal | X | n | X | X | ||||

| PCA-AD2 | male | 56 | 6 y | PCA2f | frontal | X | X | X | X |

| PCA2o | occipital | X | X | X | w | ||||

| PCA2p | parietal | X | X | w | n | ||||

| PCA-AD3 | male | 58 | 10 y | PCA3f | frontal | X | X | X | w |

| PCA3o | occipital | X | w | X | X | ||||

| PCA3p | parietal | X | X | w | w | ||||

| r-AD1 | male | 79 | 3 m | r-AD1f | frontal | X | X | w | w |

| r-AD1p | parietal | X | X | w | n | ||||

| r-AD2 | male | 83 | 6 m | r-AD2f | frontal | w | X | X | X |

| r-AD2f′ | frontal | X | X | n | n | ||||

| r-AD2o | occipital | X | X | n | n | ||||

| r-AD2p | parietal | X | X | X | X | ||||

| r-AD2p′ | parietal | X | X | n | n | ||||

| r-AD3 | female | 73 | 8 m | r-AD3f | frontal | w | X | X | X |

| r-AD4 | female | 74 | 18 m | r-AD4f | frontal | X | X | w | n |

| r-AD5 | female | 66 | 21 m | r-AD5f | frontal | X | X | w | n |

| r-AD6 | female | 65 | 18 m | r-AD6f | frontal | w | n | n | n |

| ND1 | female | 73 | -- | ND1f | frontal | X | X | w | X |

| ND2 | male | 88 | -- | ND2f | frontal | X | w | w | n |

| ND3 | male | 83 | -- | ND3f | frontal | w | w | n | n |

For ND samples, age at death.

Samples t-AD3o′, t-AD3p′, r-AD2f′, and r-AD2p′ are separate cortical tissue samples from the same patients and brain regions as t-AD3o, t-AD3p, r-AD2f, and r-AD2p, respectively.

X = data obtained; w = data obtained, but low signal-to-noise; n = data not obtained

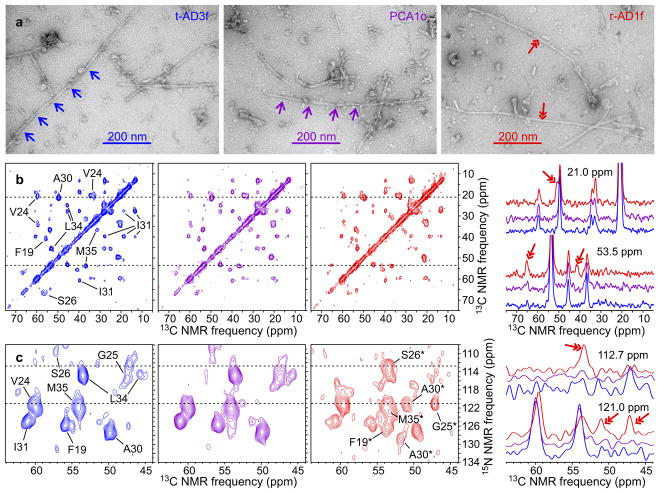

Fig. 1 shows representative data for Aβ40 fibrils. In TEM images (Fig. 1a and Extended Data Fig. 1), certain fibrils exhibit modulations of their apparent width with a period of 107 ± 20 nm (mean and standard deviation based on 65 measurements). This fibril morphology may be more abundant in images of Aβ40 fibrils derived from t-AD and PCA-AD tissue samples. However, quantification of the relative populations of fibril polymorphs from the TEM images is not possible because only a small subset of the fibrils can be visualized clearly. In contrast, all fibrils contribute to the 2D ssNMR spectra. Most 2D spectra of brain-seeded Aβ40 fibrils contain the same set of strong crosspeak signals, indicated by assignments to the isotopically labeled residues in Figs. 1b and 1c, while spectra of certain samples contain additional crosspeak signals with varying intensities.

Figure 1. Representative TEM images and 2D ssNMR spectra of brain-seeded Aβ40 fibrils.

a, Images of negatively-stained fibrils derived from t-AD3f, PCA1o, and r-AD1f tissue, recorded 4 h after initiation of seeded fibril growth (out of 37 fibril samples). Single-headed arrows indicate the periodic modulation of apparent fibril width in a common Aβ40 fibril morphology. Double-headed arrows indicate an additional morphology. b, Aliphatic regions of 2D 13C-13C spectra of the same samples (color coded), with assignments of crosspeak signals to isotopically labeled residues shown in the 2D spectrum of t-AD3f fibrils. Aβ40 was uniformly 15N,13C-labeled at F19, V24, G25, S26, A30, I31, L34, and M35. Contour levels increase by successive factors of 1.5. 1D slices at 21.0 ppm and 53.5 ppm are shown on the right, with double-headed arrows indicating signals that arise from the less common fibril structures. c, 2D 15N-13C spectra of the same samples, with assignments of the predominant crosspeak signals shown in the 2D spectrum of t-AD3f fibrils and assignments of additional signals shown in the 2D spectrum of r-AD1f fibrils. Contour levels increase by successive factors of 1.3. 1D slices at 112.7 ppm and 121.0 ppm are shown on the right, with double-headed arrows indicating signals that arise from the less common fibril structures.

Fig. 2 shows representative data for Aβ42 fibrils. TEM images do not show a single morphology that is clearly predominant within any of the tissue categories (Fig. 2a). 2D spectra of most samples do not show a single set of crosspeak signals from the isotopically labeled residues (Figs 2b and 2c).

Figure 2. Representative TEM images and 2D ssNMR spectra of brain-seeded Aβ42 fibrils.

a, Images of negatively-stained fibrils derived from t-AD3p, PCA1f, and r-AD2p tissue (out of 33 fibril samples). b, 2D 13C-13C spectra of the same samples (color coded), with assignments of crosspeak signals to isotopically labeled residues shown in the 2D spectrum of t-AD3p fibrils. Aβ42 was uniformly 15N,13C-labeled at F19, G25, A30, I31, L34, and M35. 1D slices at 27.6 ppm and 53.5 ppm are shown on the right. c, 2D 15N-13C spectra of the same samples, with assignments of the crosspeak signals shown in the 2D spectrum of t-AD3p fibrils. Two 15N-13Cα crosspeaks with similar intensities are observed for A30 and I31, indicating similar populations of two distinct fibril structures. 1D slices at 119.5 ppm and 127.1 ppm are shown on the right.

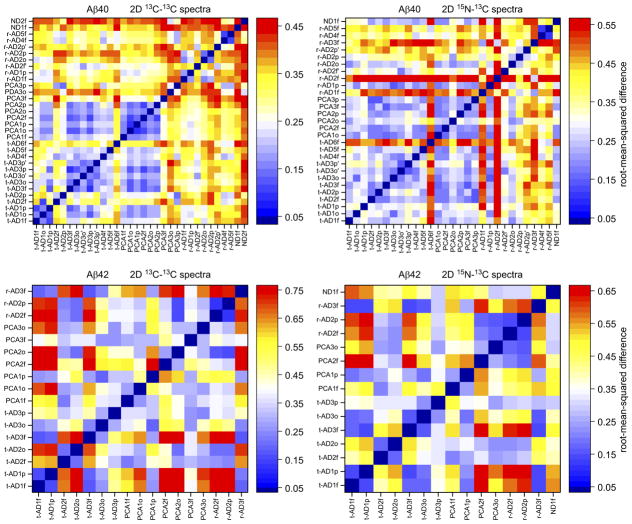

We analyzed the 2D ssNMR spectra with two independent methods, both intended to be objective and devoid of assumptions regarding the nature of the fibril structures or structural variations. Only 2D spectra with adequate signal-to-noise ratios (see Supplementary Methods) were included in these analyses. In the first method, we compared each 2D spectrum in a given set (13C-13C or 15N-13C, Aβ40 or Aβ42) with all other 2D spectra in the same set. Comparisons were quantified by pairwise root-mean-squared deviation (RMSD) values between 2D spectra, calculated as described in the Supplementary Methods. For 2D 13C-13C and 15N-13C spectra of Aβ40 fibrils, plots in Fig. 3 indicate that RMSDs among spectra from t-AD and PCA-AD samples are relatively small (blue shades) in most cases, while RMSDs between spectra from r-AD samples and spectra from either t-AD or PCA-AD samples are relatively large (red shades). Thus, t-AD and PCA-AD spectra are similar to one other, but contrast sharply with r-AD spectra, which have larger variability.

Figure 3. Pairwise differences among 2D ssNMR spectra of brain-seeded Aβ40 and Aβ42 fibrils.

RMSD values are displayed on the color scales shown to the right of each plot, with blue shades indicating relatively similar spectra and red shades indicating relatively dissimilar spectra. RMSD plots for Aβ40 fibrils indicate that fibrils derived from t-AD and PCA-AD tissue have similar 2D spectra in most cases, while greater differences are observed in spectra of Aβ40 fibrils derived from r-AD tissue. For Aβ42 fibrils, correlations between RMSD values and tissue categories are not observed. Statistical analyses are summarized in Extended Data Table 1a. Shades above white represent significant differences between 2D spectra.

Statistics are summarized in Extended Data Table 1a. Mean RMSDs among t-AD spectra are not significantly different from mean RMSDs between t-AD spectra and PCA-AD spectra. However, mean RMSDs among t-AD spectra or among PCA-AD spectra are significantly smaller than mean RMSDs between t-AD spectra and r-AD spectra or between PCA-AD spectra and r-AD spectra (p < 0.001, Welch’s t-test). In addition, for 2D 15N-13C spectra of Aβ40 fibrils, the mean RMSD value among PCA-AD spectra is significantly smaller than the mean RMSD value among t-AD spectra, the mean RMSD value among PCA-AD spectra is significantly smaller than the mean RMSD value among r-AD spectra, and the mean RMSD value among tAD spectra is significantly smaller than the mean RMSD value among r-AD spectra (p < 0.001).

For 2D spectra of Aβ42 fibrils, plots in Fig. 3 do not show clear patterns, and no statistically significant differences among mean RMSDs are identified.

In the second method of analysis, we used singular value decomposition to determine principal component spectra25 for each set of 2D spectra (see Supplementary Methods). For each set, the number N of principal component spectra equals the number of experimental 2D spectra. The experimental spectra within each set, including both crosspeak signals and random noise, can be represented exactly as linear combinations of the principal component spectra (Extended Data Figs. 5 and 6), with coefficients Ck (k = 1, 2,…, N). As shown in Fig. 4 and Extended Data Table 1b, mean values of C2 for 13C-13C and 15N-13C spectra of Aβ40 fibrils derived from r-AD tissue are significantly larger than the corresponding mean values of C2 for both t-AD spectra and PCA-AD spectra (p < 0.01). This indicates that 2D spectra of Aβ40 fibrils derived from r-AD tissue differ more strongly from the average 2D spectra than do spectra of Aβ40 fibrils derived from t-AD and PCA-AD tissue. For Aβ42 fibrils, differences in mean values of Ck are not significant.

Figure 4. Principal component analyses of 2D ssNMR spectra of brain-seeded Aβ40 and Aβ42 fibrils.

For each set of 2D spectra, the coefficients of the first five principal components (C1 through C5) are plotted in groups corresponding to fibrils derived from different tissue categories. Horizontal bars indicate mean values. The mean value of C2 for Aβ40 fibrils from r-AD tissue (n = 8 for 2D 13C-13C, n = 10 for 2D 15N-13C) is significantly different from the mean value of C2 for Aβ40 fibrils from t-AD (n = 13 for 2D 13C-13C, n =12 for 2D 15N-13C) or PCA-AD (n = 9 for 2D 13C-13C, n = 6 for 2D 15N-13C) tissue. Statistical analyses are summarized in Extended Data Table 1b.

An alternative analysis of the 2D 15N-13C spectra, in which the spectra were fit with a fixed number of crosspeaks at fixed chemical shift positions, is described in the Supplementary Methods and Extended Data Fig. 7. According to this analysis, on average, the predominant Aβ40 fibril structure typically accounts for approximately 80% of the crosspeak signal volume in 2D 15N-13C spectra of Aβ40 fibrils derived from t-AD and PCA-AD tissue, and approximately 65% in 2D 15N-13C spectra of Aβ40 fibrils derived from r-AD tissue. 15N and 13C chemical shifts in our spectra of brain-seeded fibrils are compared with previously reported chemical shifts for Aβ40 and Aβ42 fibrils1,2,4,6,7,26–28 in the Supplementary Discussion and Extended Data Fig. 8.

We draw the following main conclusions from these ssNMR experiments: (i) Although brain-seeded Aβ40 fibrils can be polymorphic, a single structure is most abundant in cortical tissue of most t-AD patients and most PCA-AD patients; (ii) Polymorphism of Aβ40 fibrils is more pronounced in r-AD samples than in t-AD and PCA-AD samples; (iii) Brain-seeded Aβ42 fibrils are generally more structurally heterogeneous than brain-seeded Aβ40 fibrils, without a clearly predominant structure even in t-AD and PCA-AD samples. Although the small number of samples prevents us from drawing definite conclusions regarding fibril structures in ND brain tissue, we have not observed ssNMR signals that are unique to ND-derived fibrils.

2D ssNMR spectra of the predominant Aβ40 fibril structure, along with the fibril morphology in Fig. 1a, match data reported previously by Lu et al. for Aβ40 fibrils from one of their two AD patients.4 This patient, called “patient 2”, was a t-AD case. In contrast, Aβ40 fibrils from their “patient 1” exhibited distinctive ssNMR signals that are not present in any of the measurements described above (Extended Data Fig. 8). The clinical history of patient 1 was also different, including an initial diagnosis of Lewy body dementia rather than AD. Thus, it remains possible that the Aβ40 fibril structure of patient 1, for which a full molecular model was developed4, is associated with a specific AD variant.

The indistinguishability of Aβ fibrils from t-AD and PCA-AD tissue suggests that phenotypic differences between these two categories arise from factors other than fibril structure, perhaps including genetic factors or differences in nonfibrillar Aβ assemblies. The greater polymorphism of Aβ40 fibrils from r-AD tissue indicated by 2D ssNMR spectra has at least two possible interpretations: (i) A fibril structure that is prevalent in r-AD tissue has enhanced neurotoxicity, through either direct or indirect mechanisms; (ii) In r-AD samples, fibrils reside in the tissue for a shorter period than in t-AD and PCA-AD samples, possibly allowing fibrils with a greater range of thermodynamic stabilities or resistance to degradation to be present at autopsy.

The greater overall heterogeneity of Aβ42 fibrils seeded with t-AD and PCA-AD extract, compared with the corresponding Aβ40 fibrils, is conceivably a consequence of imperfect amplification of Aβ42 fibril structures from brain tissue under our experimental conditions, possibly due to a stronger tendency of the more hydrophobic Aβ42 peptide to spontaneously form nonfibrillar aggregates or due to the lower abundance of Aβ42 fibrils in most of our tissue samples (Extended Data Table 2). However, 2D ssNMR spectra of a control sample, in which Aβ42 fibrils were grown in the presence of extract from occipital tissue that lacked detectable fibril seeds, show surprisingly sharp crosspeak signals that indicate roughly 70% population of a single structure (Supplementary Discussion and Extended Data Fig. 4). Thus, the greater structural heterogeneity of AD brain-seeded Aβ42 fibrils in our experiments most likely indicates greater heterogeneity of the fibril seeds within the cortical tissue. Recent experiments by Cohen et al. indicate differences in structural heterogeneity and sizes of Aβ42 aggregates, but not Aβ40 aggregates, in r-AD and t-AD brain tissue.16

In conclusion, experiments described above represent the first use of ssNMR to screen multiple tissue samples for variations in amyloid fibril structure. Similar approaches can be applied in other amyloid diseases, where related phenomena exist.20,29,30 Obvious goals for future work are to develop a full structural model for the predominant Aβ40 polymorph identified above and to determine whether structurally distinct Aβ40 polymorphs can consistently seed different patterns of Aβ pathology in suitable animal models.

Extended Data

Extended Data Figure 1. Additional TEM images of brain-seeded fibrils.

(a) TEM grids were prepared 4 h after addition of solubilized Aβ40 or Aβ42 to sonicated brain extract and were negatively stained with uranyl acetate. Collagen fibrils in the extract (40–100 nm width, with characteristic transverse bands) appear in some images. Material with an amorphous appearance is nonfibrillar, non-Aβ components of the brain extract. Yellow arrows indicate Aβ40 fibrils with an apparent width modulation, attributable to an approximately periodic twisting of the fibril structure about the fibril growth direction. TEM images of all 37 brain-seeded Aβ40 and all 33 Aβ42 fibril samples are available on-line at http://dx.doi.org/10.17632/whgp9r7tkd.1. (b) Histogram of distances between width minima for Aβ40 fibrils with apparent width modulation. The Gaussian fit to this histogram (red curve) has a mean value of 107.2 nm (n = 65) and a full-width-at-half-maximum of 46.1 nm.

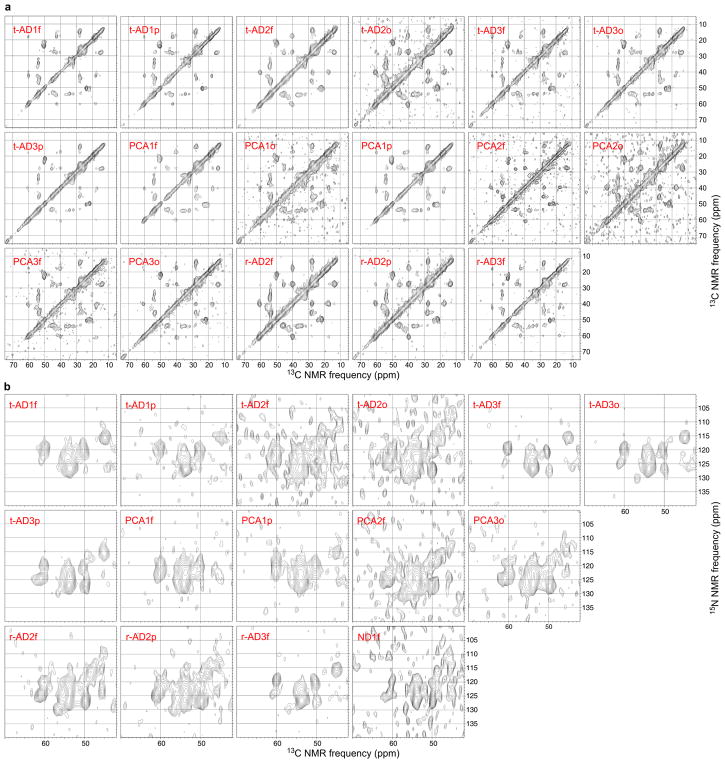

Extended Data Figure 2. 2D ssNMR spectra of brain-seeded Aβ40 fibrils.

a, 2D 13C-13C spectra of fibrils seeded with extract from t-AD, PCA-AD, r-AD, or ND tissue. Aliphatic regions are shown, with 15 contour levels increasing by successive factors of 1.3, and with the highest contour at the maximum signal in each 2D spectrum. b, 2D 15N-13C spectra of fibrils seeded with extract from t-AD, PCA-AD, r-AD, or ND tissue. Regions containing intra-residue 15N-13Cα crosspeaks are shown, with 11 contour levels increasing by successive factors of 1.3, and with the highest contour at the maximum signal in each spectrum. 15N-13Cβ crosspeaks from L34 appear in some spectra. Positions of crosspeaks from the predominant Aβ40 fibril structure are indicated by color-coded circles (F19 = blue, V24 = cyan, G25 = pink, S26 = orange, A30 = purple, I31 = red, L34 = green, M35 = magenta). Only 2D spectra that were included in the analyses in Figs. 3 and 4 of the main text are shown. The full set of 42 2D 13C-13C spectra and 40 2D 15N-13C spectra, including those with lower signal-to-noise, controls, and technical replicates, is available on-line at http://dx.doi.org/10.17632/tbp45pm92x.1.

Extended Data Figure 3. 2D ssNMR spectra of brain-seeded Aβ42 fibrils.

a, 2D 13C-13C spectra of fibrils seeded with extract from t-AD, PCA-AD, r-AD, or ND tissue. Aliphatic regions are shown, with 15 contour levels increasing by successive factors of 1.3, and with the highest contour at the maximum signal in each spectrum. b, 2D 15N-13C spectra of fibrils seeded with extract from t-AD, PCA-AD, r-AD, or ND tissue. Regions containing intra-residue 15N-13Cα crosspeaks are shown, with 11 contour levels increasing by successive factors of 1.3, and with the highest contour at the maximum signal in each spectrum. Only 2D spectra that were included in the analyses in Figs. 3 and 4 of the main text are shown. The full set of 33 2D 13C-13C spectra and 23 2D 15N-13C spectra, including those with lower signal-to-noise, controls, and technical replicates, is available on-line at http://dx.doi.org/10.17632/tbp45pm92x.1.

Extended Data Figure 4. Control experiments using cortical tissue without Aβ deposits.

Occipital tissue of a female who died from cardiac arrest at age 86 was used as a control. a, Comparison of TEM images of control tissue extract and r-AD2p′ extract after incubation for 4.0 h with solubilized Aβ40, under conditions identical to those that led to fibrils shown in Extended Data Fig. 1a. Fibrils associated with brain material were abundant on the TEM grid of the r-AD2p′-seeded sample, but were not observed in an extensive search over the TEM grid of the control sample. b, TEM images of control tissue extract and r-AD2p′ extract after incubation for 4.0 h with solubilized Aβ42, under conditions identical to those that led to fibrils shown in Extended Data Fig. 1b. Fibrils associated with brain material were abundant on the TEM grid of the r-AD2p′-seeded sample, but were not observed in an extensive search over the TEM grid of the control sample. c, 2D 13C-13C and 15N-13C spectra of Aβ40 fibrils (blue) and Aβ42 fibrils (red) that developed in control samples after 168 h or 48 h incubation, respectively, followed by 24 h intermittent sonication (see Supplemental Methods), followed by 72 h additional incubation. Contour levels increase by successive factors of 1.4. d, RMSDs between 2D spectra of control fibrils and 2D spectra of AD brain-seeded fibrils, with dashed lines at RMSD values corresponding to white shades in Fig. 3 of the main text.

Extended Data Figure 5. Principal component analyses of 2D 13C-13C and 15N-13C ssNMR spectra of brain-seeded Aβ40 fibrils.

a, The first five principal components (PC1-PC5) of the 32 experimental 2D 13C-13C spectra, shown as contour plots with positive contours in blue and negative contours in red. Principal component spectra were obtained by singular value decomposition of the experimental spectra, considering only the aliphatic region and excluding points within 5 ppm of the diagonal. Contour levels increase (or decrease, in the case of negative contours) by successive factors of 1.5. b, Experimental 2D 13C-13C spectrum of t-AD4f Aβ40 fibrils (left) and 2D spectrum constructed as a linear combination of PC1-PC5 (right, with coefficients of PC1-PC5 shown in parentheses). c, Experimental 2D 13C-13C spectrum of r-AD1f Aβ40 fibrils (left) and 2D spectrum constructed as a linear combination of PC1-PC5 (right). c, The first five principal components of the 29 experimental 2D 15N-13C spectra. d, Experimental 2D 15N-13C spectrum of PCA2p Aβ40 fibrils (left) and 2D spectrum constructed as a linear combination of PC1-PC5 (right). e, Experimental 2D 15N-13C spectrum of r-AD2o Aβ40 fibrils (left) and 2D spectrum constructed as a linear combination of PC1-PC5 (right).

Extended Data Figure 6. Principal component analyses of 2D 13C-13C and 15N-13C ssNMR spectra of brain-seeded Aβ42 fibrils.

a, The first five principal components (PC1-PC5) of the 17 experimental 2D 13C-13C spectra, plotted as in Extended Data Fig. 5. b, Experimental 2D 13C-13C spectrum of t-AD1p Aβ42 fibrils (left) and 2D spectrum constructed as a linear combination of PC1-PC5 (right, with coefficients of PC1-PC5 shown in parentheses). c, Experimental 2D 13C-13C spectrum of r-AD2f Aβ42 fibrils (left) and 2D spectrum constructed as a linear combination of PC1-PC5 (right). c, The first five principal components of the 15 experimental 2D 15N-13C spectra. d, Experimental 2D 15N-13C spectrum of t-AD3f Aβ42 fibrils (left) and 2D spectrum constructed as a linear combination of PC1-PC5 (right). e, Experimental 2D 15N-13C spectrum of r-AD2p Aβ42 fibrils (left) and 2D spectrum constructed as a linear combination of PC1-PC5 (right).

Extended Data Figure 7. Analysis of 2D 15N-13C ssNMR spectra of brain-seeded fibrils by fitting with crosspeaks at fixed chemical shift positions.

a, Examples of 2D spectra (out of the 29 Aβ40 and 15 Aβ42 spectra with adequate signal-to-noise in Table 1), with fitted crosspeak positions indicated by crosses. Red and blue crosses indicate crosspeaks for chemical shift sets “a” and “b”, respectively (see Supplementary Methods, Supplementary Discussion, and Extended Data Fig. 8). Cyan crosses indicate additional crosspeaks. Contour levels increase by successive factors of 1.4. b, Pairwise differences among fitted crosspeak volumes for spectra of Aβ40 fibrils (left) and Aβ42 fibrils (right), with color scales representing RMSD values. Total crosspeak volumes in each spectrum were normalized before calculation of RMSD values. Results from this crosspeak-fitting analysis are similar to results in Fig. 3, in which the same experimental data were analyzed by direct comparisons of signal amplitudes in 2D spectra without fitting the signals with crosspeaks at specific positions. c, Fractions of the total fitted crosspeak volumes at “a” and “b” chemical shifts, with mean values indicated by horizontal bars. For Aβ40, mean values of “a” volumes in spectra of t-AD (n = 12) or PCA-AD (n = 6) samples are significantly greater than the mean value (n = 10) in spectra of r-AD samples (p < 0.02, Welch’s t-test; p < 0.02, Mann-Whitney-Wilcoxon test).

Extended Data Figure 8. Comparisons of ssNMR chemical shifts of brain-seeded Aβ40 and Aβ42 fibrils with previously reported chemical shifts.

a, 15N and 13C chemical shifts (ppm) from spectra of brain-seeded samples in Table 1 (grouped into sets “a”, “b”, etc., based on correlations of the corresponding signal amplitudes over multiple 2D spectra) are compared with chemical shifts from previous ssNMR studies of Aβ40 and Aβ42 fibrils, as deposited in the Biological Magnetic Resonance Bank with the indicated BMRB accession numbers. b, Chemical shift differences after adjustments of chemical shift referencing in each set to make the average 13Cα shifts and the average 15N shifts equal in all sets.

Extended Data Table 1. Statistical significance of analyses in Figures 3 and 4.

a, From Fig. 3, mean RMSD values for pairs of 2D spectra within a given tissue category are compared with mean RMSD values between tissue categories or within a different tissue category. The significance of differences in mean RMSD values is assessed by Welch’s t-test (two-sided). b, From Fig. 4, mean values of coefficients of the second principal component in 2D spectra (C2) from three tissue categories are compared. The significance of differences in mean C2 values is assessed by Welch’s t-test (two-sided).

| a

| |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2D ssNMR data | t-AD/t-AD vs. t-AD/PCA-AD | t-AD/t-AD vs. t-AD/r-AD | PCA-AD/PCA-AD vs. PCA-AD/r-AD | t-AD/t-AD vs. PCA-AD/PCA-AD | t-AD/t-AD vs. r-AD/r-AD | PCA-AD/PCA-AD vs. r-AD/r-AD | |

| Aβ40 13C-13C | mean RMSD values | 0.246,0.255 | 0.246,0.308 | 0.248,0.317 | 0.246,0.248 | 0.246,0.299 | 0.248,0.299 |

| t-statistic | −0.758 | −6.48 | −4.70 | −0.11 | −2.94 | −2.29 | |

| degrees of freedom | 182 | 147 | 50 | 54 | 40 | 60 | |

| p-value | 0.45 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.91 | 0.005 | 0.026 | |

|

| |||||||

| Aβ40 15N-13C | mean RMSD values | 0.299,0.262 | 0.298,0.399 | 0.220,0.381 | 0.299,0.220 | 0.299,0.396 | 0.220,0.396 |

| t-statistic | 2.17 | −5.83 | −8.15 | 4.77 | −4.54 | −8.50 | |

| degrees of freedom | 134 | 165 | 67 | 53 | 84 | 57 | |

| p-value | 0.032 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

|

| |||||||

| Aβ42 13C-13C | mean RMSD values | 0.428,0.465 | 0.428,0.464 | 0.404,0.431 | 0.428,0.404 | 0.428,0.552 | 0.404,0.552 |

| t-statistic | −0.719 | −0.55 | −0.58 | 0.46 | −0.56 | −0.68 | |

| degrees of freedom | 37 | 39 | 38 | 35 | 2 | 2 | |

| p-value | 0.48 | 0.59 | 0.56 | 0.65 | 0.63 | 0.57 | |

|

| |||||||

| Aβ42 15N-13C | mean RMSD values | 0.317,0.381 | 0.317,0.380 | 0.387,0.373 | 0.317,0.387 | 0.317,0.437 | 0.387,0.437 |

| t-statistic | −1.61 | −1.31 | 0.191 | −1.14 | −0.804 | −0.320 | |

| degrees of freedom | 46 | 36 | 12 | 8 | 2 | 3 | |

| p-value | 0.11 | 0.20 | 0.85 | 0.29 | 0.012 | 0.77 | |

| b

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2D ssNMR data | t-AD vs. PCA-AD | t-AD vs. r-AD | PCA-AD vs. r-AD | |

| Aβ40 13C-13C | mean C2 values | −1.15,−1.60 | −1.15,4.35 | −1.60,4.35 |

| t-statistic | 0.37 | −4.16 | −3.98 | |

| degrees of freedom | 15 | 12 | 14 | |

| p-value | 0.72 | 0.0012 | 0.0013 | |

|

| ||||

| Aβ40 15N-13C | mean C2 values | −4.58,−7.47 | −4.58, 16.53 | −7.47, 16.53 |

| t-statistic | 0.714 | −3.38 | −3.58 | |

| degrees of freedom | 10 | 12 | 13 | |

| p-value | 0.49 | 0.0056 | 0.0032 | |

|

| ||||

| Aβ42 13C-13C | mean C2 values | −3.07,2.85 | 3.07,1.80 | 2.85,1.80 |

| t-statistic | −1.93 | −0.82 | 0.19 | |

| degrees of freedom | 10 | 3 | 2 | |

| p-value | 0.082 | 0.47 | 0.86 | |

|

| ||||

| Aβ42 15N-13C | mean C2 values | 8.32,−8.08 | 8.32,−7.33 | −8.08,−7.33 |

| t-statistic | 1.76 | 1.06 | −0.05 | |

| degrees of freedom | 8 | 3 | 3 | |

| p-value | 0.12 | 0.37 | 0.96 | |

Extended Data Table 2. Quantification by ELISA of Aβ40/Aβ40 molar ratios in amyloid-enriched brain extracts.

Estimated uncertainties are approximately 20%.

| sample | Aβ40/Aβ42 ratio |

|---|---|

| t-AD1o | 2.4 |

| t-AD2f | 1.4 |

| t-AD2o | 1.0 |

| t-AD2p | 1.5 |

| t-AD3f | 3.4 |

| t-AD3o | 3.8 |

| t-AD3p | 0.7 |

| PCA1o | 0.5 |

| PCA1p | 6.7 |

| PCA2f | 2.2 |

| PCA2o | 4.5 |

| PCA3f | 3.2 |

| PCA3o | 1.8 |

| PCA3p | 2.1 |

| r-AD1f | 3.1 |

| r-AD1p | 4.5 |

| r-AD2f | 4.1 |

| r-AD2o | 1.2 |

| r-AD2p | 1.9 |

| r-AD3f | 0.6 |

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases of the US National Institutes of Health, by the UK Medical Research Council and the National Institute of Health Research (NIHR) UCLH/UCL Biomedical Research Centre. We are grateful for the assistance of Simon Mead, Oke Avwenagha, and Jonathan Wadsworth at the MRC Prion Unit in selection and processing of tissue samples. We thank UK neurologists for referral of rapidly progressive dementias to the NHS National Prion Clinic, National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery (NHNN), University College London Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust (UCLH). We thank the Queen Square Brain Bank for Neurological Disorders (supported by the Reta Lila Weston Trust for Medical Research, the Progressive Supranuclear Palsy [Europe] Association and the Medical Research Council) at the UCL Institute of Neurology, for provision of the human brain tissue samples. We thank all patients and their families for generous consent to use of tissues in research.

Footnotes

Data Availability

Datasets generated during the current study are available through Mendeley Data at http://dx.doi.org/10.17632/whgp9r7tkd.1 (TEM images of Aβ40 and Aβ42 fibrils) and http://dx.doi.org/10.17632/tbp45pm92x.1 (2D ssNMR spectra of Aβ40 and Aβ42 fibrils).

Author Contributions

W.Q, J.-X.L., J.C., and R.T. designed experiments, including selection of tissue samples, development of protocols for preparation of brain-seeded fibrils, and selection of ssNMR measurements. W.Q., J.-X.L., and R.T. prepared fibril samples and acquired TEM images and ssNMR data. W.-M. Y. synthesized isotopically labelled peptides and performed ELISA measurements. W.Q. and R.T. analysed ssNMR data. J.C. and R.T. wrote the manuscript, with contributions from all other authors.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Petkova AT, et al. Self-propagating, molecular-level polymorphism in Alzheimer’s β-amyloid fibrils. Science. 2005;307:262–265. doi: 10.1126/science.1105850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Paravastu AK, Leapman RD, Yau WM, Tycko R. Molecular structural basis for polymorphism in Alzheimer’s β-amyloid fibrils. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:18349–18354. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806270105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Paravastu AK, Qahwash I, Leapman RD, Meredith SC, Tycko R. Seeded growth of β-amyloid fibrils from Alzheimer’s brain-derived fibrils produces a distinct fibril structure. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:7443–7448. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812033106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lu JX, et al. Molecular structure of β-amyloid fibrils in Alzheimer’s disease brain tissue. Cell. 2013;154:1257–1268. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.08.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bertini I, Gonnelli L, Luchinat C, Mao JF, Nesi A. A new structural model of Aβ(40) fibrils. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:16013–16022. doi: 10.1021/ja2035859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schutz AK, et al. Atomic-resolution three-dimensional structure of amyloid β fibrils bearing the Osaka mutation. Angew Chem-Int Edit. 2014;53:1–6. doi: 10.1002/anie.201408598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xiao YL, et al. Aβ(1–42) fibril structure illuminates self-recognition and replication of amyloid in Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2015;22:499–505. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sgourakis NG, Yau WM, Qiang W. Modeling an in-register, parallel “Iowa” Aβ fibril structure using solid state NMR data from labeled samples with Rosetta. Structure. 2015;23:216–227. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2014.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goldsbury C, Frey P, Olivieri V, Aebi U, Muller SA. Multiple assembly pathways underlie amyloid-β fibril polymorphisms. J Mol Biol. 2005;352:282–298. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.07.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Meinhardt J, Sachse C, Hortschansky P, Grigorieff N, Fandrich M. Aβ(1–40) fibril polymorphism implies diverse interaction patterns in amyloid fibrils. J Mol Biol. 2009;386:869–877. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang R, et al. Interprotofilament interactions between Alzheimer’s Aβ(1–42) peptides in amyloid fibrils revealed by cryoEM. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:4653–4658. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0901085106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kodali R, Williams AD, Chemuru S, Wetzel R. Aβ(1–40) forms five distinct amyloid structures whose β-sheet contents and fibril stabilities are correlated. J Mol Biol. 2010;401:503–517. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.06.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Meyer-Luehmann M, et al. Exogenous induction of cerebral β-amyloidogenesis is governed by agent and host. Science. 2006;313:1781–1784. doi: 10.1126/science.1131864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Langer F, et al. Soluble Aβ seeds are potent inducers of cerebral β-amyloid deposition. J Neurosci. 2011;31:14488–14495. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3088-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stohr J, et al. Distinct synthetic Aβ prion strains producing different amyloid deposits in bigenic mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:10329–10334. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1408968111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cohen ML, et al. Rapidly progressive Alzheimer’s disease features distinct structures of amyloid-β. Brain. 2015;138:1009–1022. doi: 10.1093/brain/awv006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bessen RA, Marsh RF. Distinct PrP properties suggest the molecular basis of strain variation in transmissible mink encephalopathy. J Virol. 1994;68:7859–7868. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.12.7859-7868.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Collinge J, Sidle KCL, Meads J, Ironside J, Hill AF. Molecular analysis of prion strain variation and the aetiology of ‘new variant’ CJD. Nature. 1996;383:685–690. doi: 10.1038/383685a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Safar J, et al. Eight prion strains have PrPSc molecules with different conformations. Nat Med. 1998;4:1157–1165. doi: 10.1038/2654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gath J, et al. Unlike twins: An NMR comparison of two α-synuclein polymorphs featuring different toxicity. PLoS One. 2014;9 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0090659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.van der Wel PCA, Lewandowski JR, Griffin RG. Solid state NMR study of amyloid nanocrystals and fibrils formed by the peptide GNNQQNY from yeast prion protein Sup35p. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:5117–5130. doi: 10.1021/ja068633m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Collinge J, Clarke AR. A general model of prion strains and their pathogenicity. Science. 2007;318:930–936. doi: 10.1126/science.1138718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tang-Wai DF, et al. Clinical, genetic, and neuropathologic characteristics of posterior cortical atrophy. Neurology. 2004;63:1168–1174. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000140289.18472.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schmidt C, et al. Rapidly progressive Alzheimer’s disease: A multicenter update. J Alzheimers Dis. 2012;30:751–756. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2012-120007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Henry ER, Hofrichter J. Singular value decomposition: Application to analysis of experimental data. Method Enzymol. 1992;210:129–192. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Qiang W, Yau WM, Luo YQ, Mattson MP, Tycko R. Antiparallel β-sheet architecture in Iowa-mutant β-amyloid fibrils. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:4443–4448. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1111305109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Colvin MT, et al. Atomic resolution structure of monomorphic Ab42 amyloid fibrils. J Am Chem Soc. 2016;138:9663–9674. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b05129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Walti MA, et al. Atomic-resolution structure of a disease-relevant Aβ(1–42) amyloid fibril. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016 doi: 10.1073/pnas.1600749113. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Guo JL, et al. Distinct α-synuclein strains differentially promote tau inclusions in neurons. Cell. 2013;154:103–117. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.05.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sanders DW, et al. Distinct tau prion strains propagate in cells and mice and define different tauopathies. Neuron. 2014;82:1271–1288. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.04.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.