Abstract

Background

HIV-associated vasculopathy and opportunistic infections (OIs) might cause vascular atherosclerosis and aneurysmal arteriopathy, which could increase the risk of incident stroke. However, few longitudinal studies have investigated the link between HIV and incident stroke. This cohort study evaluated the association of HIV and OIs with incident stroke.

Methods

We identified adults with HIV infection in 2000–2012, using the Taiwan National Health Insurance Research Database. A control cohort without HIV infection, matched for age and sex, was selected for comparison. Stroke incidence until December 31, 2012 was then ascertained for all patients. A time-dependent Cox regression model was used to determine the association between OIs and incident stroke among HIV patients.

Results

Among a total of 106,875 patients (21,375 HIV patients and 85,500 matched controls), stroke occurred in 927 patients (0.87%) during a mean follow-up period of 5.44 years, including 672 (0.63%) ischemic strokes and 255 (0.24%) hemorrhagic strokes. After adjusting for other covariates, HIV infection was an independent risk factor for incident all-cause stroke [adjusted hazard ratio (AHR) 1.83; 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.58–2.13]. When type of stroke was considered, HIV infection increased the risks of ischemic (AHR 1.33; 95%CI 1.09–1.63) and hemorrhagic stroke (AHR 2.01; 95%CI 1.51–2.69). The risk of incident stroke was significantly higher in HIV patients with cryptococcal meningitis (AHR 4.40; 95%CI 1.38–14.02), cytomegalovirus disease (AHR 2.79; 95%CI 1.37–5.67), and Penicillium marneffei infection (AHR 2.90; 95%CI 1.16–7.28).

Conclusions

HIV patients had an increased risk of stroke, particularly those with cryptococcal meningitis, cytomegalovirus, or P. marneffei infection.

Keywords: stroke, HIV, opportunistic infection

INTRODUCTION

Stroke remains one of the leading causes of death worldwide.1 Although vascular risk factors and aging are the most important contributors to the burden of stroke, current evidence indicates that infectious causes (e.g., HIV) might increase stroke risk.2,3

When HIV infects the host, HIV virion may increase endothelial permeability and cause vasculitis.4,5 HIV-associated vasculitis leads to intramural arterial ischemia, which may increase the risk of stroke.6,7 Although increasing evidence suggesting that HIV infection may increase the risk of stroke, few longitudinal studies have examined the association. A prior cohort study found that the risk of incident all-cause stroke was higher among HIV patients than among non-HIV patients.8 Another three studies showed that HIV infection was associated with increased risk of ischemic9,10 or hemorrhagic stroke.11 However, previous studies of the association between HIV infection and incident stroke were limited to male10 or hospital-based patients,9 those receiving antiretroviral treatment11, and inadequately controlled for potential confounders such as hypertension and coronary heart disease.8

Opportunistic infections (OIs) can cause vasculitis and are important in the development of stroke in HIV patients.3 A series of case reports showed that OIs [e.g., cryptococcal meningitis, cytomegalovirus (CMV), or Candida albicans infection] in HIV patients caused central nervous system vasculitis and may lead to stroke development.3,12–14 Although accumulating evidence suggests that OIs are associated with increased risk of incident stroke in HIV patients, few large-scale epidemiologic studies have investigated this association. Stroke management and prevention should include identification and prevention of specific stroke risk factors, particularly in high-risk populations. We therefore conducted a nationwide population-based cohort study of the risk of incident stroke in Taiwanese with and without HIV during the period 2000–2012.

METHODS

Data Source

The Taiwan National Health Insurance system is a mandatory universal health insurance program that has provided comprehensive medical care to more than 99% of Taiwanese citizens since 1995.15 In this nationwide cohort study we analyzed patient data obtained from the National Health Insurance Research Database (NHIRD). The NHIRD can be found at http://nhird.nhri.org.tw/ and are provided to scientists for research purposes. The NHIRD is a large-scale computer database that is derived from the national health insurance system, administered by the Bureau of National Health Insurance (NHI), and provided to scientists for research purposes. Patient identification codes in the NHIRD are scrambled and de-identified before the data are released to researchers. The accuracy of NHIRD diagnoses of major diseases such as diabetes mellitus and cerebrovascular disease has been well validated.16,17 This study was approved by the institutional review board of Kaohsiung Medical University.

Study Subjects

In this cohort study, we selected persons aged 15 years or older who received a new HIV diagnosis during the period from January 1, 2000 through December 31, 2012. A diagnosis of new HIV required the (1) presence of a relevant International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) code, namely, 042-044, 7958, or V08, in an inpatient setting or three or more outpatient visits and (2) presence of an examination for viral load or CD4 count (order codes: 26017A1, 14074B, 12071A, 12071B, 12073A, 12073B, 12074A, 12074B).18 Patients who had received a stroke diagnosis (ICD-9-CM codes 430-437) before an HIV diagnosis were excluded.

The control group was selected from the NHIRD. Since all individuals in the NHIRD had detailed information regarding the dates of hospital visit, the control group was matched by age, sex, and date of HIV diagnosis (±7 days). Four controls were randomly selected for each HIV patient.19,20 Control subjects were excluded if they had received a diagnostic code for HIV or stroke before the date of enrollment in the study. The HIV and control groups were both followed until a diagnosis of stroke, death, or December 31, 2012. Deaths were confirmed by examining the death certificate database of Taiwan.

Variables and Measures

The outcome new stroke was defined as ICD-9-CM codes 430-437 and included hemorrhagic stroke (ICD-9-CM codes 430-432) and ischemic stroke (ICD-9-CM codes 433-437).21 The sensitivity and specificity of stroke diagnosis in NHIRD were 94.5% and 97.9%, respectively, for patients hospitalized for stroke in Taiwan.16 To improve case ascertainment, only patients hospitalized for stroke were included in the analysis.

The covariates included sociodemographic characteristics, comorbidities, opportunistic infection after HIV diagnosis, and highly actively antiretroviral treatment (HAART). Sociodemographic characteristics included income level and urbanization. Income level was calculated from the average monthly income of the insured person and classified as low [≤19 200 New Taiwan Dollars (NTD)], intermediate (19 201 NTD to <40 000 NTD), and high (≥40 000 NTD). Urbanization was categorized as urban and rural area. HIV patients were considered to receive HAART if they received HAART before the new onset of stroke. The comorbidities included diabetes (ICD-9-CM code 250), chronic kidney disease (CKD; ICD-9-CM codes 580-587), hypertension (ICD-9-CM codes 401-405), coronary heart disease (ICD-9-CM codes 410-414), cancer (ICD-9-CM codes 140-208), dyslipidemia (ICD-9-CM code 272), and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE; ICD-9-CM code 710.0). OIs after diagnosis of HIV included Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection (ICD-9-CM codes 011-018), disseminated Mycobacterium avium complex infection (ICD-9-CM code 0312), Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia (ICD-9-CM code 1363), cryptococcal meningitis (ICD-9-CM code 3210), Penicillium marneffei infection (ICD-9-CM code 1179), Toxoplasma encephalitis (ICD-9-CM code 130), candidiasis (ICD-9-CM code 112), and herpes zoster (ICD-9-CM code 053). A person was considered to have a comorbidity or OI only if the condition occurred in an inpatient setting or was noted in three or more outpatient visits.22

Statistical Analysis

First, demographic data from study subjects were analyzed. Continuous data are presented as mean [standard deviation (SD)], and the two-sample t test was used for comparisons between groups. Categorical data were analyzed by using the Pearson χ2 test, when appropriate.

The incidences of ischemic, hemorrhagic, and all-cause stroke per 1000 PY were calculated in patients with and without HIV infection. Among HIV patients, the start date for the calculation of person-years was the date of the first HIV/AIDS clinic visit, whereas the start date for control groups was the date of enrollment. The end date for HIV and control groups was December 31, 2012 or the date of stroke or death during the study follow-up period. The relative hazards (RHs) of incident stroke in HIV patients, as compared with patients without HIV infection, were estimated by using Cox proportional hazards models.

A Cox proportional hazards model was used to determine the association between HIV infection and incident all-cause stroke after adjusting for age, sex, and comorbidities. The multinomial Cox proportional hazards regression was used to evaluate the association between HIV, incident ischemic, and hemorrhagic stroke. In addition, to determine the association between OIs and incident stroke, a time-dependent Cox proportional hazards model was used to identify risk factors for incident stroke among HIV patients. In these models, HAART and OIs were regarded as time-dependent covariates,12 whereas other confounders, such as age, sex, and comorbidities, which were collected at baseline, were treated as fixed covariates. Adjusted HRs (AHRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) are reported, to indicate the strength and direction of associations.

To examine the robustness of the main findings, sensitivity analyses were conducted after stratifying study subjects by age, sex, and comorbidities. Also, we conducted additional analyses for the association between HIV and incident stroke, with death as the competing risk.23 All data management and analyses were performed by using the SAS 9.4 software package (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

RESULTS

Participant Selection

We identified 22,327 persons who had received a new HIV diagnosis during the period from January 1, 2000 through December 31, 2012. After excluding those younger than 15 years (n = 317), those with antecedent stroke disorder (n = 350), those with unknown gender (n = 145), and those with unknown income (n = 140), the remaining 21,375 HIV patients were included in the analysis (Figure S1). Another 85 500 subjects without HIV were randomly selected for inclusion in the control group. The overall mean (SD) age was 33.92 (10.57) years, and 91.3% of the subjects in the HIV group were male. Mean (SD) follow-up time was 4.65 (3.36) years in the HIV cohort and 5.64 (3.33) years in the control group. The demographic characteristics of the two groups are shown in Table 1. As compared with the control group, HIV patients had a higher proportion of CKD, cancer, and SLE and a lower proportion of HTN and dyslipidemia.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of HIV Patients and Matched Controls

| Characteristics | No. (%) of subjects*

|

P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| HIV patients, n=21,375 | Control, n=85,500 | ||

| Age, yr | |||

| Mean ± SD | 33.92 ± 10.57 | 33.92 ± 10.57 | 1 |

| 15–49 | 19618 (91.78) | 78472 (91.78) | 1 |

| ≥50 | 1757 (8.22) | 7028 (8.22) | |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 19526 (91.35) | 78104 (91.35) | 1 |

| Female | 1849 (8.65) | 7396 (8.65) | |

| Income level | |||

| Low | 12524 (58.59) | 34029 (39.80) | <.001 |

| Intermediate | 6418 (30.03) | 32926 (38.51) | |

| High | 2433 (11.38) | 18545 (21.69) | |

| Urbanization | |||

| Rural | 4140 (19.37) | 26549 (31.05) | <.001 |

| Urban | 17235 (80.63) | 58951 (68.95) | |

| Comorbidities | |||

| Diabetes | 371 (1.74) | 1350 (1.58) | 0.103 |

| CKD | 127 (0.59) | 272 (0.32) | <.001 |

| HTN | 533 (2.49) | 2684 (3.14) | <.001 |

| CHD | 157 (0.73) | 550 (0.64) | 0.141 |

| Dyslipidemia | 201 (0.94) | 1391 (1.63) | <.001 |

| Cancer | 522 (2.44) | 1018 (1.19) | <.001 |

| SLE | 90 (0.42) | 47 (0.05) | <.001 |

| New onset of stroke | |||

| Ischemic stroke | 186 (0.87) | 486 (0.57) | <.001 |

| Hemorrhagic stroke | 66 (0.31) | 189 (0.22) | 0.019 |

| All-cause stroke | 252 (1.18) | 675 (0.79) | <.001 |

| Incidence of stroke‡ | |||

| Ischemic stroke | 1.87 | 1.01 | <.001 |

| Hemorrhagic stroke | 0.66 | 0.39 | <.001 |

| All-cause stroke | 2.53 | 1.40 | <.001 |

| Follow-up years, mean (SD) | 4.65 (3.36) | 5.64 (3.33) | <.001 |

HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; SD, standard deviation; CKD, chronic kidney disease; HTN, hypertension; CHD, coronary heart disease; SLE, systemic lupus erythematous.

Unless stated otherwise;

events per 1,000 person-years.

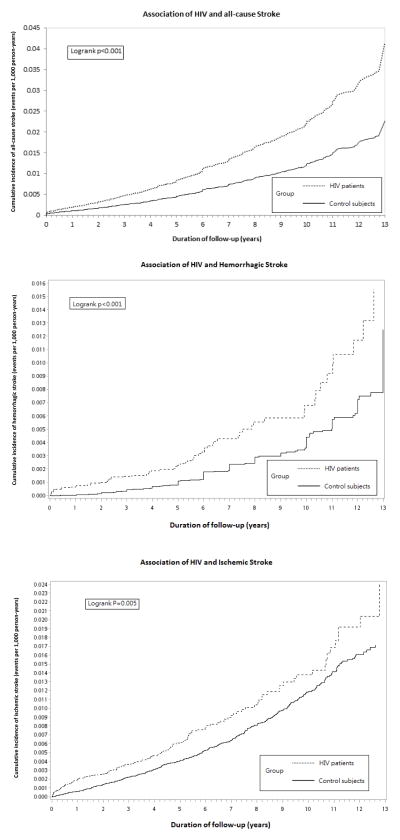

Stroke Incidence Rate

During the study follow-up period, new onset of all-cause stroke was noted in 927 individuals: 252 (1.18%) HIV patients and 675 (0.79%) controls. The incidence rate of all-cause stroke was 2.53 per 1000 PY among HIV patients and 1.40 per 1000 PY among the controls (P <0.001). The incidence rate of ischemic stroke was 1.87 per 1000 PY among HIV patients and 1.01 per 1000 PY among the control group (P <0.001) (Table 1). Moreover, the incidence rate of hemorrhagic stroke was 0.66 per 1000 PY among HIV patients and 0.39 per 1000 PY among the controls (P <0.001). Time to diagnosis of incident all-cause, ischemic, and hemorrhagic stroke was significantly shorter in patients with HIV infection (P <0.001, log-rank test; Figure 1). The RHs of incident ischemic, hemorrhagic, and all-cause stroke among HIV patients were 1.42 (95% CI 1.17–1.71), 2.10 (95% CI 1.59–2.77), and 1.93 (95% CI 1.67–2.23), respectively, as compared with controls.

FIGURE 1.

Kaplan–Meier curves for time to diagnosis of incident stroke in patients with and without HIV infection.

Abbreviations: HIV, human immunodeficiency virus.

Association of HIV Infection with Incident All-cause Stroke

A Cox proportional hazards model was used to identify independent risk factors for all-cause stroke. After adjusting for age, sex, and comorbidities, HIV infection significantly increased the risk of incident all-cause stroke (AHR 1.83; 95% CI 1.58–2.13) (Table 2). Other risk factors for incident all-cause stroke included age ≥50 years (AHR 6.15; 95% CI 5.31–7.12), diabetes (AHR 1.77; 95% CI 1.37–2.30), CKD (AHR 2.08; 95% CI 1.34–3.21), HTN (AHR 2.41; 95% CI 1.96–2.96), and cancer (AHR 1.53; 95% CI 1.08–2.16). As compared with patients with low incomes, those with high incomes (AHR 0.66; 95% CI 0.56–0.77) had a lower risk of incident all-cause stroke. Other factors inversely associated with incident all-cause stroke were being female (AHR 0.72; 95% CI 0.59–0.88) and living in an urban area (AHR 0.46; 95% CI 0.38–0.57).

TABLE 2.

Univariate and Multivariate Analyses of Factors Associated with All-cause Stroke among Patients with and without HIV Infection.

| Characteristic | No. of patients | All-cause Stroke | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||

| n (%) | HR (95% CI) | AHR (95% CI) | ||

| HIV infection | ||||

| No | 85500 | 675 (0.79) | 1 | 1 |

| Yes | 21375 | 252 (1.18) | 1.93 (1.67–2.23)*** | 1.83 (1.58–2.13)*** |

| Demographics | ||||

| Age, yr | ||||

| 15–49 | 98090 | 515 (0.53) | 1 | 1 |

| ≥50 | 8785 | 412 (4.69) | 8.16 (7.16–9.29)*** | 6.15 (5.31–7.12)*** |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 97630 | 815 (0.83) | 1 | 1 |

| Female | 9245 | 112 (1.21) | 1.19 (0.98–1.45) | 0.72 (0.59–0.88)** |

| Income level | ||||

| Low | 46553 | 591 (1.27) | 1 | 1 |

| Intermediate | 39344 | 231 (0.59) | 0.60 (0.52–0.70)*** | 0.91 (0.79–1.05) |

| High | 20978 | 105 (0.50) | 0.56 (0.45–0.69)*** | 0.66 (0.56–0.77)*** |

| Urbanization | ||||

| Rural | 30689 | 304 (0.99) | 1 | 1 |

| Urban | 76186 | 623 (0.82) | 0.85 (0.74–0.97)* | 0.46 (0.38–0.57)*** |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| Diabetes | ||||

| No | 105154 | 845 (0.80) | 1 | 1 |

| Yes | 1721 | 82 (4.76) | 7.09 (5.65–8.89)*** | 1.77 (1.37–2.30)*** |

| CKD | ||||

| No | 106476 | 905 (0.85) | 1 | 1 |

| Yes | 399 | 22 (5.51) | 7.67 (5.03–11.72)*** | 2.08 (1.34–3.21)** |

| HTN | ||||

| No | 103658 | 759(0.73) | 1 | 1 |

| Yes | 3217 | 168 (5.22) | 7.95 (6.72–9.39)*** | 1.02 (0.74–1.42) |

| CHD | ||||

| No | 106168 | 880 (0.83) | 1 | 1 |

| Yes | 707 | 47 (6.65) | 8.27 (6.16–11.09)*** | 1.20 (0.87–1.65) |

| Dyslipidemia | ||||

| No | 105283 | 880 (0.84) | 1 | 1 |

| Yes | 1592 | 47 (2.95) | 4.30 (3.21–5.77)*** | 1.64 (0.77–3.51) |

| Cancer | ||||

| No | 105335 | 893 (0.85) | 1 | 1 |

| Yes | 1540 | 34 (2.21) | 2.92 (2.07–4.11)*** | 1.53 (1.08–2.16)* |

| SLE | ||||

| No | 106738 | 920 (0.86) | 1 | 1 |

| Yes | 137 | 7 (5.11) | 5.18 (2.46–10.88)*** | 2.41 (1.96–2.96)*** |

<.05;

<.01;

<.001

SD, standard deviation; AHR, adjusted hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; CKD, chronic kidney disease; HTN, hypertension; CHD, coronary heart disease; SLE, systemic lupus erythematous.

Association of HIV Infection with Incident Ischemic and Hemorrhagic Stroke

Table 3 shows the results of multinomial Cox regression analysis of factors associated with ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke in the study subjects. HIV infection significantly increased the risks of incident ischemic (AHR 1.33; 95% CI 1.09–1.63) and hemorrhagic stroke (AHR 2.01; 95% CI 1.51–2.69).

TABLE 3.

Multinomial Regression Analysis of the Association of HIV Infection with Ischemic and Hemorrhagic Stroke in Patients with HIV and Matched Controls.

| Variables | Ischemic stroke

|

Hemorrhagic stroke

|

|---|---|---|

| AHR (95% CI) | AHR (95% CI) | |

| HIV infection | 1.33 (1.09–1.63)** | 2.01 (1.51–2.69)*** |

| Demographics | ||

| Age, yr | ||

| 15–49 | 1 | 1 |

| ≥50 | 7.63 (6.32–9.22)*** | 3.95 (2.83–5.50)*** |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 1 | 1 |

| Female | 0.79 (0.62–1.00)* | 0.57 (0.37–0.88)* |

| Income level | ||

| Low | 2.15 (1.67–2.75)*** | 2.11 (1.40–3.19)*** |

| Intermediate | 1.26 (0.95–1.66) | 1.78 (1.14–2.77)* |

| High | 1 | 1 |

| Urbanization | ||

| Rural | 1 | 1 |

| Urban | 0.95 (0.80–1.12) | 0.84 (0.64–1.10) |

| Comorbidities | ||

| Diabetes | 2.28 (1.70–3.07)*** | 0.55 (0.24–1.25) |

| CKD | 1.59 (0.90–2.81) | 4.26 (1.98–9.19)*** |

| HTN | 2.15 (1.65–2.81)*** | 3.41 (2.17–5.37)*** |

| CHD | 1.53 (1.07–2.19)* | 0.28 (0.08–0.94)* |

| Dyslipidemia | 0.92 (0.62–1.37) | 1.32 (0.67–2.61) |

| Cancer | 1.10 (0.67–1.82) | 2.27 (1.23–4.19)** |

| SLE | 1.96 (0.74–5.15) | 1.73 (0.38–7.97) |

<.05;

<.01;

<.001

SD, standard deviation; AHR, adjusted hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; CKD, chronic kidney disease; HTN, hypertension; CHD, coronary heart disease; SLE, systemic lupus erythematous.

Sensitivity Analysis of the Association between HIV Infection and Stroke

The sensitivity analyses of the association between HIV and stroke were conducted after stratifying study subjects by age, sex, and comorbidities (Figure S2). HIV infection was significantly positively associated with the risk of all-cause stroke in all patient subgroups. In addition, HIV infection significantly increased the risk of ischemic stroke in all patient subgroups except those aged ≥50 years, males, those with low or high incomes, those living in urban areas, and those with hypertension. Furthermore, HIV infection significantly increased the risk of hemorrhagic stroke in all patient subgroups except those with intermediate or high incomes.

Additional analysis with death as the competing risk showed that HIV infection was associated with increased risk of incident all-cause stroke (AHR 1.55; 95% CI 1.33–1.80) (Supplementary table 1).

Association of OIs with Incident Stroke

A time-dependent Cox proportional hazards model was used to analyze associations between OIs and incident stroke among HIV patients. After adjusting for age, sex, comorbidities, and HAART, CMV infection (AHR 2.79; 95% CI 1.37–5.67), cryptococcal meningitis (AHR 4.40; 95% CI 1.38–14.02), and P. marneffei infection (AHR 2.90; 95% CI 1.16–7.28) were associated with increased risk of incident all-cause stroke (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Univariate and Multivariate Analyses of the Associations of Opportunistic infections with Incident All-cause Stroke among HIV Patients.

| Characteristic | No. of patients | All-cause Stroke | Univariate analysis | Multivariates analysis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||

| n (%) | HR (95% CI) | AHR (95% CI) | ||

| Demographics | ||||

| Age, yr | ||||

| 15–49 | 19618 | 160 (0.82) | 1 | 1 |

| ≥50 | 1757 | 92 (5.24) | 9.11 (6.75–12.30)*** | 6.69 (4.73–9.46)*** |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 19526 | 209 (1.07) | ||

| Female | 1849 | 43 (2.33) | 2.14 (1.47–3.11)*** | 1.12 (0.74–1.69) |

| Income level | ||||

| Low | 12524 | 178 (1.42) | 1 | 1 |

| Intermediate | 6418 | 55 (0.86) | 0.55 (0.37–0.81)** | 0.59 (0.40–0.87)** |

| High | 2433 | 19 (0.78) | 0.60 (0.35–1.02) | 0.65 (0.38–1.11) |

| Urbanization | ||||

| Rural | 4140 | 63 (1.52) | 1 | 1 |

| Urban | 17235 | 89 (0.52) | 0.63 (0.45–0.89)** | 0.86 (0.60–1.24) |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| Diabetes | ||||

| No | 21004 | 235 (1.12) | 1 | 1 |

| Yes | 371 | 17 (4.58) | 5.29 (3.01–9.31)*** | 1.26 (0.66–2.42) |

| CKD | ||||

| No | 21248 | 246 (1.16) | 1 | 1 |

| Yes | 127 | 6 (4.72) | 4.74 (1.76–12.79)** | 1.42 (0.51–3.97) |

| HTN | ||||

| No | 20842 | 216 (1.04) | 1 | 1 |

| Yes | 533 | 36 (6.75) | 8.73 (5.86–13.01)*** | 2.07 (1.26–3.41)** |

| CHD | ||||

| No | 21218 | 243 (1.15) | 1 | 1 |

| Yes | 157 | 9 (5.73) | 5.72 (2.68–12.20)*** | 0.75 (0.33–1.71) |

| Dyslipidemia | ||||

| No | 21174 | 241 (1.14) | 1 | 1 |

| Yes | 201 | 11 (5.47) | 4.93 (2.32–10.51)*** | 0.98 (0.42–2.28) |

| Cancer | ||||

| No | 20853 | 235 (1.13) | 1 | 1 |

| Yes | 522 | 17 (3.26) | 2.75 (1.45–5.21)** | 1.38 (0.71–2.68) |

| SLE | ||||

| No | 21285 | 245 (1.15) | 1 | 1 |

| Yes | 90 | 7 (7.78) | 6.73 (3.14–14.41)*** | 1.93 (0.85–4.410 |

| OIs after HIV diagnosis | ||||

| CMV infection | ||||

| No | 21064 | 242(1.15) | 1 | 1 |

| Yes | 311 | 10 (3.22) | 3.14 (1.66–5.95)*** | 2.71 (1.34–5.49)** |

| TB infection | ||||

| No | 20676 | 237 (1.15) | 1 | 1 |

| Yes | 699 | 15 (2.15) | 1.94 (1.14–3.30)* | 1.64 (0.92–2.92) |

| Disseminated Mycobacterium avium complex infection | ||||

| No | 21269 | 249 (1.17) | 1 | 1 |

| Yes | 106 | 3 (2.83) | 3.23 (1.03–10.10)* | 2.68 (0.80–8.94) |

| Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia | ||||

| No | 20594 | 242 (1.18) | 1 | 1 |

| Yes | 781 | 10 (1.28) | 1.19 (0.63–2.25) | 1.11 (0.54–2.28) |

| Cryptococcal meningitis | ||||

| No | 21286 | 249 (1.17) | 1 | 1 |

| Yes | 89 | 3 (3.37) | 3.36 (1.07–10.53)* | 4.58 (1.44–14.62)* |

| Candidiasis | ||||

| No | 20392 | 241 (1.18) | 1 | 1 |

| Yes | 983 | 11 (1.12) | 0.97 (0.52–1.78) | 0.92 (0.48–1.78) |

| Penicillium marneffei infection | ||||

| No | 21249 | 247 (1.16) | 1 | 1 |

| Yes | 126 | 5 (3.97) | 3.43 (1.41–8.35)** | 2.82 (1.13–7.08)* |

| Toxoplasma encephalitis | ||||

| No | 21335 | 247 (1.16) | 1 | 1 |

| Yes | 40 | 2 (5.00) | 2.53 (0.36–18.09) | 1.75 (0.23–13.23) |

| Herpes zoster | ||||

| No | 20020 | 238 (1.19) | 1 | 1 |

| Yes | 1355 | 14 (1.03) | 0.88 (0.51–1.52) | 0.80 (0.46–1.40) |

| HAART | ||||

| No | 7290 | 136 (1.87) | 1 | 1 |

| Yes | 14085 | 116 (0.82) | 0.42 (0.31–0.57)*** | 0.49 (0.35–0.69)*** |

<.05;

<.01;

<.001

SD, standard deviation; AHR, adjusted hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; CMV, cytomegalovirus; CHD, coronary heart disease; CMV, cytomegalovirus; TB, tuberculosis; HAART, highly active antiretroviral therapy.

When type of stroke was considered, time-dependent multinomial Cox regression showed that CMV infection (AHR 2.96; 95% CI 1.17–7.52), disseminated Mycobacterium avium complex infection (AHR 3.51; 95% CI 1.02–12.06), and cryptococcal meningitis (AHR 5.82; 95% CI 1.78–19.02) were associated with increased risk of ischemic stroke (Supplemental table 2). P. marneffei infection was associated with increased risk of hemorrhagic stroke (AHR 4.48; 95% CI 1.07–18.76).

DISCUSSION

This nationwide cohort study found that after adjusting for demographic data, comorbidities, and income level, the risk of all-cause stroke was higher among HIV patients. When type of stroke was considered, HIV infection significantly increased the risks of both ischemic and hemorrhagic strokes. Moreover, among HIV-infected patients, stroke risk was significantly higher in those with cryptococcal meningitis, CMV disease, or P. marneffei infection.

An association between HIV infection and stroke has been previously reported. However, few longitudinal studies have evaluated the link between HIV infection and incident stroke. A Danish population-based cohort study found that HIV patients had a higher risk of all-cause stroke (AHR 1.60; 95% CI 1.30–1.95).8 A cohort study of the US healthcare system found that the incidence rate for ischemic stroke was 5.27 per 1000 PY for HIV patients and 3.75 per 1000 PY for non-HIV patients.9 In the US cohort study, HIV infection was an independent predictor of incident ischemic stroke (AHR 1.21, 95% CI 1.01–1.46).9 Another cohort study of the US Veterans Affairs administrative data showed that male veterans with HIV infection had an increased risk of ischemic stroke compared with uninfected male veterans (AHR 1.17; 95% CI 1.01–1.36).10 A study of Canadian administrative databases showed that HIV patients had a higher risk of intracranial hemorrhage as compared with persons without HIV (AHR 3.28; 95% CI 1.75–6.12).11 Our data show overall stroke rates of 2.53 per 1000 PY in HIV patients and 1.40 per 1000 PY in the controls (HR 1.93). HIV infection was an independent predictor of incident all-cause stroke. When type of stroke was considered, HIV infection significantly increased the risks of ischemic and hemorrhagic strokes. These findings suggest that HIV is an independent predictor of ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke.

HIV-associated vasculopathy (e.g., atherosclerosis and aneurysmal arteriopathy) may have increased the risk of incident ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke among the HIV patients in this study. When HIV virus infects a host, HIV virion or its particles (e.g., GP120 or TAT) may directly stimulate the endothelium and increase endothelial permeability, which facilitates leukocyte invasion of vessel walls and results in vascular inflammation.4,5 HIV-associated vasculitis of the vasa vasorum may lead to intramural arterial ischemia, which results in aneurysmal dilation and a potential increase in the risk of intracranial hemorrhage.6,7 HIV virion can also cause endothelial dysfunction, an early marker of atherosclerosis, which leads to platelet adhesion and aggregation, activation of blood clotting, fibrinolysis derangement, and a tendency toward a prothrombotic state.5,24 HIV-induced endothelial inflammation also increases production of reactive oxygen species, which results in vascular cell proliferation.3 Exacerbation of HIV-associated vasculopathy (e.g., aneurysmal arteriopathy and atherosclerosis) may cause dilating aneurysm, vascular constriction, and thrombotic occlusion, which might ultimately lead to hemorrhagic or ischemic stroke.

HIV-associated OIs may have increased the risk of incident stroke among the HIV patients in this study. OIs in HIV patients could exacerbate HIV-associated vasculopathy and increase the risk of incident stroke.3 A series of case reports found that OIs may increase the risk of incident stroke in HIV patients;12–14 however, few longitudinal studies have evaluated the association between OIs and incident stroke.3 This study followed 21,436 HIV patients, and time-dependent analysis revealed that HIV patients with OIs (e.g., cryptococcal meningitis, CMV infection, and P. marneffei infection) had higher risks of incident stroke. Cryptococcal meningitis may cause vasculitis with spasm and constriction,14,25 which could increase the risk of incident stroke in HIV patients.

A previous case study reported an association between CMV infection and incident stroke.12 However, only a limited number of long-term cohort studies have evaluated the link between CMV infection and incident stroke. To the best of our knowledge, only the recent Italian Cohort Naïve Antiretrovirals (ICoNA) study has evaluated the association between CMV infection and incident stroke in HIV patients. That study found that the risk of cerebrovascular disease was higher among HIV patients who were CMV-seropositive at baseline than among those who were CMV-seronegative (AHR 2.27; 95% CI 0.97–5.32; P = 0.058).26 Although the ICoNA study was the first cohort study of the link between CMV infection and stroke, it was limited by the small number of cerebrovascular events (n = 6). Time-dependent analysis in the present study showed that CMV infection was an independent predictor of incident ischemic stroke among HIV patients. CMV-induced inflammation and atherosclerosis may increase the risk of incident stroke in HIV patients coinfected with CMV. When CMV infects a host, it can infect vascular cells and cause vascular cell inflammation and proliferation by activating nuclear factor-kB.27,28 CMV infection of smooth muscle cells may also initiate production of powerful proinflammatory cytokines (e.g., leukotriene B4), which may contribute to atherosclerosis, stenosis, and incident stroke.29 The present findings suggest that, to reduce the risk of incident stroke, comprehensive care should be provided to HIV patients, particularly those with cryptococcal meningitis, P. marneffei, and CMV infections.

This study is the largest cohort study of the association between HIV infection and subsequent stroke development. Our research design, which included unbiased subject selection and strict HIV diagnostic criteria, enhances the validity of the findings. In addition, this nationwide population-based study traced all HIV and control patients, thus minimizing referral bias, because all medical care was covered by the Taiwan National Health Insurance system. Moreover, the large sample size was powered to detect even very small differences between the controls and HIV patients. Additionally, the timing of OIs was ascertained in all patients, and OIs were regarded as a time-dependent variable in the analysis. Longitudinal studies that do not account for changes in exposure during the study period do not yield precise estimates of the exposure effect on outcomes.30

The present study nevertheless has some limitations. First, viral loads and CD4 counts—the index of immunologic status of patients—were unavailable in our database. Therefore, our study used opportunistic infections as the proxy for immunologic status of patients and evaluated the association between OIs and incident stroke. However, more studies are needed to determine the association between CD4 count, viral loads, and incident stroke. Second, diagnoses of HIV, stroke, and OIs that rely on administrative claims data recorded by physicians or hospitals may be less accurate than those made in a prospective clinical setting. However, there is no reason to suspect that the validity of claims data would differ with respect to patient HIV status. HIV infection in this study was defined strictly, by using the relevant ICD-9 codes, and confirmed by an examination for viral load or CD4 count, which yielded better diagnostic validity. A stroke event was defined as patient hospitalization for stroke. Although a prior validity study found that the accuracy of the Taiwan NHIRD in recording stroke diagnoses was high (98%) among patients hospitalized for stroke,16 the outcome of stroke may have been misclassified. This non-differential misclassification of outcome would most likely to bias the results toward a null association. Finally, the external validity of our findings may be a concern because almost all our enrollees were Taiwanese. The generalizability of our results to other non-Asian ethnic groups thus requires further verification. Nevertheless, our findings suggest new avenues for future research.

In conclusion, this nationwide long-term cohort study found a link between HIV infection and stroke. HIV infection was associated with a higher risk of incident all-cause stroke, after adjustment for demographic characteristics and comorbidities. When type of stroke was considered, HIV infection significantly increased the risks of both ischemic and hemorrhagic strokes. Furthermore, among HIV-infected patients, stroke risk was significantly increased in those with cryptococcal meningitis, CMV disease, and P. marneffei infections. These findings suggest that HIV patients had an increased the risk of stroke, particularly those with cryptococcal meningitis, cytomegalovirus, or P. marneffei infection.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Supported by a grant from amfAR, The Foundation for AIDS Research, with support from the US National Institutes of Health’s National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, and the National Cancer Institute, as part of the International Epidemiologic Databases to Evaluate AIDS (IeDEA; U01AI069907). This study was also supported by a Kaohsiung Medical University “Aim for the Top Universities Grant” (No. KMU-TP103E01).

This study is based in part on data from the National Health Insurance Research Database provided by the Bureau of National Health Insurance, Department of Health and managed by National Health Research Institutes.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Murray CJ, Vos T, Lozano R, et al. Disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) for 291 diseases and injuries in 21 regions, 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2012;380:2197–2223. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61689-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Emsley HC, Hopkins SJ. Acute ischaemic stroke and infection: recent and emerging concepts. Lancet Neurol. 2008;7:341–353. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(08)70061-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Benjamin LA, Bryer A, Emsley HC, Khoo S, Solomon T, Connor MD. HIV infection and stroke: current perspectives and future directions. Lancet Neurol. 2012;11:878–890. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(12)70205-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kuller LH, Tracy R, Belloso W, et al. Inflammatory and coagulation biomarkers and mortality in patients with HIV infection. PLoS Med. 2008;5:e203. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kline ER, Sutliff RL. The roles of HIV-1 proteins and antiretroviral drug therapy in HIV-1-associated endothelial dysfunction. J Investig Med. 2008;56:752–769. doi: 10.1097/JIM.0b013e3181788d15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chetty R, Batitang S, Nair R. Large artery vasculopathy in HIV-positive patients: another vasculitic enigma. Hum Pathol. 2000;31:374–379. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(00)80253-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goldstein DA, Timpone J, Cupps TR. HIV-associated intracranial aneurysmal vasculopathy in adults. J Rheumatol. 2010;37:226–233. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.090643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rasmussen LD, Engsig FN, Christensen H, et al. Risk of cerebrovascular events in persons with and without HIV: a Danish nationwide population-based cohort study. AIDS. 2011;25:1637–1646. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283493fb0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chow FC, Regan S, Feske S, Meigs JB, Grinspoon SK, Triant VA. Comparison of ischemic stroke incidence in HIV-infected and non-HIV-infected patients in a US health care system. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2012;60:351–358. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31825c7f24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sico JJ, Chang CC, So-Armah K, et al. HIV status and the risk of ischemic stroke among men. Neurology. 2015;84:1933–1940. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000001560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Durand M, Sheehy O, Baril JG, LeLorier J, Tremblay CL. Risk of spontaneous intracranial hemorrhage in HIV-infected individuals: a population-based cohort study. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2013;22:e34–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2012.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Anderson AM, Fountain JA, Green SB, Bloom SA, Palmore MP. Human immunodeficiency virus-associated cytomegalovirus infection with multiple small vessel cerebral infarcts in the setting of early immune reconstitution. J Neurovirol. 2010;16:179–184. doi: 10.3109/13550281003735717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kieburtz KD, Eskin TA, Ketonen L, Tuite MJ. Opportunistic cerebral vasculopathy and stroke in patients with the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Arch Neurol. 1993;50:430–432. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1993.00540040082019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rosario M, Song SX, McCullough LD. An unusual case of stroke. Neurologist. 2012;18:229–232. doi: 10.1097/NRL.0b013e31825bbf4d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cheng TM. Taiwan’s new national health insurance program: genesis and experience so far. Health Aff (Millwood) 2003;22:61–76. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.22.3.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cheng CL, Kao YH, Lin SJ, Lee CH, Lai ML. Validation of the National Health Insurance Research Database with ischemic stroke cases in Taiwan. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2011;20:236–242. doi: 10.1002/pds.2087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lin CC, Lai MS, Syu CY, Chang SC, Tseng FY. Accuracy of diabetes diagnosis in health insurance claims data in Taiwan. J Formos Med Assoc. 2005;104:157–163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen M, Jen IA, Chen YM. Nationwide Study of Cancer in HIV-infected Taiwanese Children in 1998–2009. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2015 doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wacholder S, McLaughlin JK, Silverman DT, Mandel JS. Selection of controls in case-control studies. I. Principles. Am J Epidemiol. 1992;135:1019–1028. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Beaumont JJ, Steenland K, Minton A, Meyer S. A computer program for incidence density sampling of controls in case-control studies nested within occupational cohort studies. Am J Epidemiol. 1989;129:212–219. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Juang HT, Chen PC, Chien KL. Using antidepressants and the risk of stroke recurrence: report from a national representative cohort study. BMC Neurol. 2015;15:86. doi: 10.1186/s12883-015-0345-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yen YF, Chung MS, Hu HY, et al. Association of pulmonary tuberculosis and ethambutol with incident depressive disorder: a nationwide, population-based cohort study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2015;76:e505–511. doi: 10.4088/JCP.14m09403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jason PF, Gray RJ. A proportional hazards model for the subdistribution of a competing risk. J Am Stat Assoc. 1999;94:496–509. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Neuhaus J, Jacobs DR, Jr, Baker JV, et al. Markers of inflammation, coagulation, and renal function are elevated in adults with HIV infection. J Infect Dis. 2010;201:1788–1795. doi: 10.1086/652749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leite AG, Vidal JE, Bonasser Filho F, Nogueira RS, Oliveira AC. Cerebral infarction related to cryptococcal meningitis in an HIV-infected patient: case report and literature review. Braz J Infect Dis. 2004;8:175–179. doi: 10.1590/s1413-86702004000200008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huang ZR, Yu LP, Yang XC, et al. Human cytomegalovirus linked to stroke in a Chinese population. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2012;18:457–460. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-5949.2012.00326.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kowalik TF, Wing B, Haskill JS, Azizkhan JC, Baldwin AS, Jr, Huang ES. Multiple mechanisms are implicated in the regulation of NF-kappa B activity during human cytomegalovirus infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:1107–1111. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.3.1107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Speir E, Yu ZX, Ferrans VJ, Huang ES, Epstein SE. Aspirin attenuates cytomegalovirus infectivity and gene expression mediated by cyclooxygenase-2 in coronary artery smooth muscle cells. Circ Res. 1998;83:210–216. doi: 10.1161/01.res.83.2.210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Qiu H, Straat K, Rahbar A, Wan M, Soderberg-Naucler C, Haeggstrom JZ. Human CMV infection induces 5-lipoxygenase expression and leukotriene B4 production in vascular smooth muscle cells. J Exp Med. 2008;205:19–24. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Collett D. Modelling survival data in medical research. 2. Chapman & Hall; 2003. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.