Abstract

A large pool of clinicians is needed to meet growing demand for HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP). We surveyed a mixed group of HIV specialists and non-specialists in the San Francisco Bay Area to determine their attitudes toward and training needs regarding prescribing PrEP to persons at increased risk of HIV infection. Willingness to prescribe was associated with experience in caring for HIV-infected patients (AOR 4.76, 95% CI 1.43-15.76, p=0.01). Desire for further training was associated with concerns about drug resistance (p=0.04) and side effects (p=0.04), and was more common among non-ID specialists. Clinicians favored on-line and in-person training methods.

Keywords: HIV, PrEP, survey, clinical providers, capacity building

Introduction

On the basis of randomized controlled trials1–3, pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) consisting of daily oral emtricitabine/tenofovir (FTC/TDF) was approved by the US FDA in 2012 for use as HIV prevention in adults at increased risk of HIV infection. This was followed by comprehensive clinical guidelines from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in 20144 and endorsement of PrEP in the 2015 update to the National HIV/AIDS Strategy5. Recent data suggest an increase in PrEP knowledge and uptake among at-risk populations in several US cities and states 6, 7, although a nationally representative sample of primary care providers found one third of them were unaware of PrEP8.

As community interest in this highly effective strategy grows, diffusion of PrEP will require a sufficient number of providers who are knowledgeable and willing to prescribe it. Given that approximately 30% of eligible persons in San Francisco are estimated to have taken PrEP in 2013–20149 and both public10 and private11, 12 providers in San Francisco have documented burgeoning enrollment in their programs, understanding regional provider readiness to prescribe PrEP is critical to ensure that provider supply is well matched to patient demand.

The national discussion about provider capacity to offer PrEP is being heightened by recent estimates that over 1.2 million Americans at risk for HIV are eligible to receive it, comparable to the number of HIV-infected individuals eligible for antiretroviral treatment13. To meet this demand for PrEP, health systems will need to engage a large pool of providers, including primary care physicians. Many HIV specialists assert that primary care offices should be the principal venues for PrEP implementation, whereas many primary care providers contend that specialists’ knowledge of antiretroviral therapy make them better suited as PrEP providers, a “purview paradox”14 that must be solved if we are to realize the personal and public health benefits of this promising bio-behavioral HIV prevention strategy.14, 15

We surveyed a diverse group of primary care providers and HIV specialists in the San Francisco Bay Area, as a region that has seen early adoption of PrEP, to better understand their current PrEP prescribing behaviors, any concerns about PrEP, and educational needs to inform local training and capacity building efforts in support of further PrEP diffusion.

Methods

A 20-item electronic, structured questionnaire was emailed to primary care providers in May 2014 through the nine-county San Francisco Bay Area Collaborative Research Network (SFBCRN: www.SFBayCRN.org) comprised of community and private practice providers engaged by the UCSF Clinical Translational Science Institute, as well as to HIV specialists, some of whom are infectious disease (ID) trained, at the San Francisco General Hospital (SFGH) and University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) Medical Center HIV clinics. Main questionnaire domains included sociodemographics and practice characteristics, assessment of patients’ PrEP eligibility, intention to prescribe PrEP, concerns about PrEP, and desire for training and preferred methods to get additional information about PrEP. Participants were offered a $30 gift certificate for survey completion; non-responders were emailed 3 reminder invitations. Questionnaire data were collected, automatically de-identified and labeled with study codes using Qualtrics software (Qualtrics LLC, Provo, UT). Multivariate analyses were performed to assess the association between the main outcome variable (intention to prescribe PrEP, defined as would be definitely or highly likely to prescribe PrEP to an HIV-uninfected patient without medical contraindications) and sociodemographic and practice variables, PrEP knowledge and prior prescribing behaviors. The final model incorporated predictors significantly associated with the outcome at a p-value ≤0.10, as well as age. All statistical analyses were performed using STATA version 9.0 (STATA Corp, College Station, Texas). The study was approved by the Committee on Human Research at the University of California, San Francisco.

RESULTS

Provider Characteristics

Of the 686 providers contacted to complete the survey, 608 were general primary care providers and 78 were HIV specialist providers at SFGH and UCSF. Overall, 99 (14%) completed the survey (89% physicians, 9% nurse practitioners, and 2% physician assistants) and were included in subsequent analyses (see Table 1). Prescribers’ median age was 43 years, more than half were female, and a majority (69%) described themselves as white, whereas 24% were Asian, 2% Black and 8% Latino (race/ethnicity were not mutually exclusive). Over two thirds (69%) of the providers surveyed cared for a mix of HIV-infected and uninfected patients in their practices, whereas 20% percent saw HIV-uninfected patients exclusively, and 10% saw HIV-infected patients exclusively; 12% specialized in infectious disease. Over 75% had practiced medicine 5 or more years. Practice sites included academic (36%) and community (28%) clinics, private offices (14%), public health clinics (11%), and health maintenance organizations (3%). Most providers accepted a mix of public insurance plans, including Medicaid (90%), Medicare (87%), or city/county sponsored health plans (63%); 68% accepted uninsured patients.

Table 1. Provider Characteristics Associated with High Willingness to Prescribe PrEP.

Provider characteristics associated with the outcome variable of high willingness to prescribe PrEP (defined as very or extremely likely to prescribe FTC/TDF PrEP to an adult at ongoing risk of HIV infection and without contraindications to FTC/TDF). All associations were calculated using the χ2 test, and shown as unadjusted odds ratios, with corresponding 95% confidence intervals and corresponding p-values.

| Characteristic | N | % | OR | 95%CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | 99 | 100 | -- | -- | -- |

| Age (quartiles) | |||||

| 28–34 | 20 | 20 | 1 | ref | |

| 35–42 | 26 | 26 | 0.97 | (0.19–5.02) | 0.97 |

| 43–51 | 27 | 27 | 0.42 | (0.09–1.91) | 0.25 |

| 52–70 | 26 | 26 | 0.59 | (0.21–2.78) | 0.50 |

| Gender | |||||

| Female | 55 | 56 | 1 | ref | |

| Male | 43 | 43 | 0.65 | (0.24–1.72) | 0.38 |

| Decline | 1 | 1 | -- | ||

| Race/Ethnicity | |||||

| White | 69 | 69 | 1 | ||

| Nonwhite | 30 | 30 | 1.56 | (0.54–4.51) | 0.41 |

| Years in Practice | |||||

| <5 | 22 | 22 | 1 | ref | |

| 5–10 | 26 | 26 | 1.22 | (0.26–5.68) | 0.8 |

| >10 | 51 | 52 | 0.65 | (0.18–2.30) | 0.50 |

| Profession | |||||

| NP/PA | 11 | 11 | 1 | ref | |

| MD/DO | 88 | 89 | 2.39 | (0.61–9.26) | 0.19 |

| Specialty | |||||

| Non-Infectious Disease | 87 | 88 | 1 | ref | |

| Infectious Disease | 12 | 12 | 8.1 | (0.46–142.3) | 0.056 |

| Do you care for HIV+ Patients in your Practice | |||||

| No | 20 | 20 | 1 | ref | |

| Yes1 | 78 | 80 | 6.8 | (2.07–22.36) | 0.0003 |

| Insurance Accepted | |||||

| Public Only | 50 | 51 | 1 | ref | |

| Private and Public | 49 | 49 | 0.53 | (0.19–1.43) | 0.20 |

| Heard of PrEP | |||||

| No | 8 | 8 | 1 | ref | |

| Yes | 91 | 92 | 2.43 | (0.52–11.35) | 0.24 |

| Have Prescribed PrEP | |||||

| No | 73 | 74 | 1 | ref | |

| Yes | 26 | 26 | 4.22 | (0.88–20.35) | 0.051 |

| Want Training on PrEP | |||||

| No | 35 | 35 | 1 | ref | |

| Yes | 64 | 65 | 1.5 | (0.56–4.04) | 0.42 |

In a multivariate model including age, caring for HIV+ patients, specialty (ID vs non-ID) and PrEP prescribing history, caring for HIV+ patients was independently associated with willingness to prescribe (AOR 4.76, 95% CI 1.43-15.76, P=0.01).

Provider Experience with and Attitudes toward PrEP

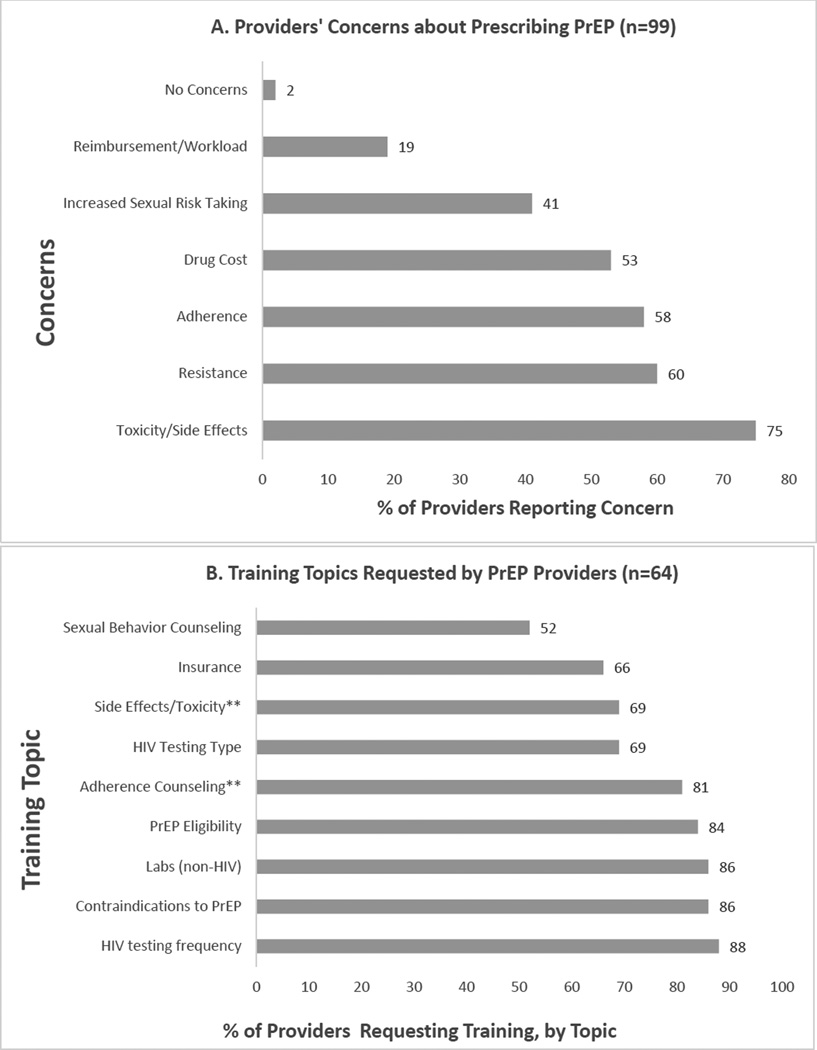

Almost all clinicians had heard of PrEP (92%), although only 26% had prescribed it. Nevertheless, most providers (70%) were very or somewhat confident in prescribing PrEP to patients with ongoing risk of HIV infection and no medical contraindications. When asked to which patients they would prescribe PrEP, most clinicians identified patients at increased risk in accordance with CDC guidelines4: men who have sex with men (MSM) and women with an HIV infected male partner (91% and 92%, respectively); women with multiple partners (88%); MSM with inconsistent condom use during receptive anal sex (83%); MSM with multiple partners (78%); and MSM with inconsistent condom use during insertive anal sex (71%). While not specifically identified in the guidelines as an eligible target population, but known to be a population at significant risk16, 69% would prescribe to male-to-female transwomen. When asked how likely they were to prescribe PrEP to a patient with ongoing risk of HIV and no medical contraindications, 77 (79%) were definitely or very likely to do so. In bivariate analysis (Table 1), experience in treating HIV-infected patients was associated with high (definitely or very likely) willingness to prescribe (p-value=0.0003), and while not statistically significant, it appears that ID specialty and prior PrEP prescribing may be associated with willingness (p values 0.056 and 0.051, respectively). Clinicians reported concerns about PrEP (Figure 1A), the most common being toxicity/side effects (75%), acquiring antiretroviral resistance (60%), and adherence (58%). There was no association between willingness to prescribe and any of the concerns reported about PrEP (data not shown).

Figure 1.

(A) Frequency of providers’ concerns about prescribing PrEP, expressed as percentage of all (n=99) providers reporting each concern. (B) Training topics requested by providers, expressed as the percentage of all providers wanting PrEP training (n=64) who requested training on each topic. **More non-ID providers than ID providers wanted training in adherence counseling (84% vs. 50%, p=0.04) and PrEP side effects and toxicities (74% vs. 17%, p=0.004).

In a multivariate logistic model including age, prior PrEP prescribing, ID specialty, and caring for HIV-infected patients, high willingness to prescribe was independently associated with caring for HIV-infected patients (AOR 4.76, 95% CI 1.43-15.76, P=0.01).

Provider Interest in Receiving Training on PrEP

Almost two-thirds of providers (65%) wanted further training on PrEP. Wanting further training was associated with having concerns about drug resistance (OR 2.43, 95%CI 1.02-5.80, p=0.04) and side effects (OR 2.5, 95%CI 1.01-6.19, p=0.04), but not with other concerns (adherence, toxicity, cost, sexual risk behavior). Although desire for PrEP training was more common among those who had never prescribed PrEP (68%, vs 54% among those who had prescribed), for non-ID specialists (67%, vs 50% among ID specialists), or did not care for HIV-infected patients (70%, vs. 64% among those caring for HIV infected patients), none of these associations reached statistical significance. As seen in Figure 1B, the most common training topics of interest were HIV testing frequency (88%), contraindications to PrEP use (86%), lab monitoring (86%), PrEP eligibility (84%), and adherence counseling (81%). More non-ID clinicians than ID specialists, however, wanted training in adherence counseling (84% vs. 50%, p=0.04) and PrEP side effects and toxicities (74% vs. 17%, P=0.004). There was a trend for more non-ID specialists compared to ID specialists to want additional training in sexual behavior counseling related to PrEP (55% vs. 17%, p=0.072). Providers expressed interest in a mix of training methods, including self-directed, online training in the form of web-based repositories of clinical (47%) and counseling (40%) guidelines, or eLearning courses (35%). Almost a third (31%) still desired face-to-face training and expressed interest in accessing a telephone warm line to seek clinical support (30%).

DISCUSSION

In this online survey, we found San Francisco Bay Area clinicians were highly aware of PrEP and willing to prescribe it to eligible adults. Approximately a quarter of the sample, largely composed of non-ID specialist primary care providers, had ever prescribed PrEP, versus fewer than 10% of primary care providers in a national survey in 201516. The San Francisco Bay Area prescribing experience may reflect early regional awareness about PrEP which began over a decade ago with the conduct of PrEP safety and efficacy trials17, the completion of a large demonstration project conducted at the municipal sexually transmitted disease clinic10, 18, as well as rapid uptake by several local health care organizations19. The tempo of PrEP use nationally may be increasing: Recently-presented national prescribing data indicate a surge in PrEP (738% from 2012 to 2015) 7, similar to that observed earlier in San Francisco11: Cities with the highest number of PrEP starts in 2015 were, in order, New York City, San Francisco, Chicago, and Washington, DC7. As in other studies in the Northeastern US and nationwide15, 16, 20, we found that provider experience in caring for HIV infected individuals was highly associated with willingness to prescribe. Thus, to accelerate regional PrEP provider capacity in the face of growing user demand, public health practitioners should initially target support to primary care providers with HIV care experience and primary care clinics with panels of patients at risk for infection based on recent HIV diagnoses. This strategy may be warranted in other early HIV epicenters where generalists often care for individuals living with HIV, and may also see the seronegative partners of their HIV-infected patients or other patients who may be eligible to receive PrEP.

We also found that a majority of providers surveyed wanted additional training on PrEP. Providers’ training needs centered on clinical issues: toxicities and side effects, the potential for drug resistance, and adherence. These likely reflect concerns, even among ART-experienced providers, about giving antiretroviral drugs to HIV-uninfected patients. It is understandable that primary care providers less experienced with antiretrovirals seemed especially interested in training on adherence, side effects and toxicities. As providers in our study preferred both in-person as well as self-directed training, public health detailing21 that involves brief, interactive face-to-face training with providers may be a useful strategy as it may increase the likelihood of PrEP prescribing22. In addition, the availability of the National Clinical Consultation Center Warmline for HIV providers, recently expanded to include PrEP23, should be promoted. Self-directed online learning resources that include updated guidelines, clinical protocols, and instructional videos could also be disseminated.

This study had limitations. The response rate for this online provider survey was relatively low, although consistent with several studies using this strategy24–27. The overall low response rate may have introduced bias as respondents may have already had strong interest in PrEP, thereby overestimating willingness to prescribe. However, approximately three quarters had still not prescribed it and a large proportion harbored concerns about PrEP and identified significant training needs, suggesting that this group may reflect the larger group of providers that would benefit from targeted outreach and capacity building, and not just innovators or early-adopters28. In addition, mid-level practitioners were underrepresented in our sample, and given their important role in providing PrEP in several settings16, 22, future assessments of their attitudes and training needs should be pursued as they may differ from physicians. While providers correctly identified persons at increased risk of HIV infection, including high risk heterosexual women, subgroups such as female partners of people who inject drugs and commercial sex workers were not explicitly listed, and future assessments should query providers regarding their readiness to identify these individuals and provide PrEP to maximize the benefit of this strategy to all women at risk. Finally, the generalizability of our findings may be limited to urban epicenters where it is common for primary care practices to care for both HIV infected and uninfected patients16.

Despite concerns about PrEP, this sample largely consisting of primary care providers expressed willingness to prescribe PrEP to patients at increased risk of HIV infection. Early outreach to clinicians with experience in caring for HIV-infected patients may be an efficient method for rapid PrEP expansion and should include training that focuses on clinical issues to incorporate prescribing ART and longitudinal follow-up into routine clinical care of HIV-uninfected persons.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the participants for their time and attention in responding to the survey. This project was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health, through Grant Number UL1TR001436, and by the National Institute of Mental Health, through Grant Number R25 MH097591 and Grant Number R01MH095628. The manuscript’s contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH or the San Francisco Department of Public Health

References

- 1.Grant RM, Lama JR, Anderson PL, et al. Preexposure chemoprophylaxis for HIV prevention in men who have sex with men. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(27):2587–2599. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1011205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thigpen MC, Rose CE, Paxton LA. Antiretroviral preexposure prophylaxis for HIV prevention. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(1):82–83. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1210464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baeten JM, Donnell D, Ndase P, et al. Antiretroviral prophylaxis for HIV prevention in heterosexual men and women. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(5):399–410. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1108524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. [Accessed April 5, 2016];Preexposure Prophylaxis for the Prevention of HIV Infection in the United States - 2014 - prepguidelines2014.pdf. http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/prepguidelines2014.pdf.

- 5. [Accessed April 5, 2016];National HIV/AIDS Strategy for The United States: Updated to 2020 - nhas-update.pdf. https://www.aids.gov/federal-resources/national-hiv-aids-strategy/nhas-update.pdf.

- 6.Eaton L, Herrick A, Bukowski L, et al. PrEP and PEP Awareness and Uptake, and Correlates of Use, among a Large Sample of Black Men who Have Sex with Men [Abstract 1769]; National HIV Prevention Conference; Atlanta. 2015. Dec, [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mera R, McCallister S, Palmer B, Mayer G, Magnusen D, Rawlings K. International AIDS Society 2016. Durban, South Africa: 2016. Jul, Truvada (TVD) for HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) utilization in the United States (2013-2015) [Google Scholar]

- 8.CDC. [Accessed April 5, 2016];Daily Drug Can Reduce HIV Risk. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. http://www.cdc.gov/vitalsigns/hivprep/index.html. Published November 24, 2015.

- 9.Grant RM, Liu AY, Hecht J, et al. Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections. Seattle: 2015. Feb, Scale-Up of Preexposure Prophylaxis in San Francisco to Impact HIV Incidence [Abstract 25] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu AY, Cohen SE, Vittinghoff E, et al. Preexposure Prophylaxis for HIV Infection Integrated With Municipal- and Community-Based Sexual Health Services. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(1):75–84. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.4683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Volk JE, Marcus JL, Phengrasamy T, et al. No New HIV Infections With Increasing Use of HIV Preexposure Prophylaxis in a Clinical Practice Setting. Clin Infect Dis Off Publ Infect Dis Soc Am. 2015;61(10):1601–1603. doi: 10.1093/cid/civ778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gibson S, Grant R, Hall C. National HIV Prevention Conference. Atlanta: 2015. Dec, San Francisco AIDS Foundation Launches PrEP Health Program in Community-Based Sexual Health Center [Abstract 1834] [Google Scholar]

- 13. [Accessed April 7, 2016];Vital Signs: Estimated Percentages and Numbers of Adults with Indications for Preexposure Prophylaxis to Prevent HIV Acquisition — United States. 2015 doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6446a4. http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6446a4.htm?s_cid=mm6446a4_w. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Hoffman S, Guidry JA, Collier KL, et al. A Clinical Home for Preexposure Prophylaxis: Diverse Health Care Providers’ Perspectives on the"Purview Paradox". J Int Assoc Provid AIDS Care. 2016;15(1):59–65. doi: 10.1177/2325957415600798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Krakower DS, Mayer KH. The role of healthcare providers in the roll out of preexposure prophylaxis. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2016;11(1):41–48. doi: 10.1097/COH.0000000000000206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smith DK, Mendoza MCB, Stryker JE, Rose CE. PrEP Awareness and Attitudes in a National Survey of Primary Care Clinicians in the United States, 2009–2015. PLOS ONE. 2016;11(6):e0156592. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0156592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grohskopf LA, Chillag KL, Gvetadze R, et al. Randomized trial of clinical safety of daily oral tenofovir disoproxil fumarate among HIV-uninfected men who have sex with men in the United States. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 1999. 2013;64(1):79–86. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31828ece33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cohen SE, Vittinghoff E, Bacon O, et al. High interest in preexposure prophylaxis among men who have sex with men at risk for HIV infection: baseline data from the US PrEP demonstration project. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 1999. 2015;68(4):439–448. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu A, Cohen S, Follansbee S, et al. Early experiences implementing pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for HIV prevention in San Francisco. PLoS Med. 2014;11(3):e1001613. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Krakower DS, Oldenburg CE, Mitty JA, et al. Knowledge, Beliefs and Practices Regarding Antiretroviral Medications for HIV Prevention: Results from a Survey of Healthcare Providers in New England. PloS One. 2015;10(7):e0132398. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0132398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Avorn J, Soumerai SB. Improving drug-therapy decisions through educational outreach. A randomized controlled trial of academically based"detailing". N Engl J Med. 1983;308(24):1457–1463. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198306163082406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Edelstein Z, Reid A, Daskalakis D. National HIV Prevention Conference. Atlanta: 2015. Dec, Public Health Detailing on Pre- and Post-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP and PEP) in New York City, 2014–2015 [Abstract 1344] [Google Scholar]

- 23.PrEP Guidelines & Resources. [Accessed April 7, 2016];Clin Consult Cent. 2015 May; http://nccc.ucsf.edu/clinical-resources/prep-guidelines-and-resources/

- 24.Nicholls K, Chapman K, Shaw T, et al. Enhancing Response Rates in Physician Surveys: The Limited Utility of Electronic Options: Enhancing Response Rates in Physician Surveys. Health Serv Res. 2011;46(5):1675–1682. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2011.01261.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Braithwaite D, Emery J, Lusignan S de, Sutton S. Using the Internet to conduct surveys of health professionals: a valid alternative? Fam Pract. 2003;20(5):545–551. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmg509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.VanGeest JB, Johnson TP, Welch VL. Methodologies for improving response rates in surveys of physicians: a systematic review. Eval Health Prof. 2007;30(4):303–321. doi: 10.1177/0163278707307899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim C, Vasaiwala S, Haque F, Pratap K, Vidovich MI. Radiation Safety Among Cardiology Fellows. Am J Cardiol. 2010;106(1):125–128. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2010.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Berwick DM. Disseminating innovations in health care. JAMA. 2003;289(15):1969–1975. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.15.1969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]