Abstract

Sex-specific differentiation, development, and function of the reproductive system are largely dependent on steroid hormones. For this reason, developmental exposure to estrogenic and anti-androgenic endocrine disrupting chemicals (EDCs) is associated with reproductive dysfunction in adulthood. Human data in support of “Developmental Origins of Health and Disease” (DOHaD) comes from multigenerational studies on offspring of diethylstilbestrol-exposed mothers/grandmothers. Animal data indicate that ovarian reserve, female cycling, adult uterine abnormalities, sperm quality, prostate disease, and mating behavior are susceptible to DOHaD effects induced by EDCs such as bisphenol A, genistein, diethylstilbestrol, p,p′-dichlorodiphenyl-dichloroethylene, phthalates, and polyaromatic hydrocarbons. Mechanisms underlying these EDC effects include direct mimicry of sex steroids or morphogens and interference with epigenomic sculpting during cell and tissue differentiation. Exposure to EDCs is associated with abnormal DNA methylation and other epigenetic modifications, as well as altered expression of genes important for development and function of reproductive tissues. Here we review the literature exploring the connections between developmental exposure to EDCs and adult reproductive dysfunction, and the mechanisms underlying these effects.

Keywords: Developmental programming, epigenetic reprogramming, transgenerational transmission, DNA methylation, histone modification, non-coding RNA, reproductive behaviors, reproductive dysfunction

1. Introduction

In recent years, significant insights have been gained in our understanding of the critical roles of steroid hormones and other morphogens in orchestrating development, differentiation, and maturation of the reproductive system. These findings explain the exquisite sensitivity of the reproductive system to disruption by molecules that either mimic or disrupt steroid hormone actions. What remains to be uncovered are the long-term consequences of “environment by cell” and “environment by genome” interactions during critical developmental windows of the male and female reproductive systems and the mechanisms that govern these changes.

Here we discuss the concepts of windows of sensitivity to developmental disruption and the “Developmental Origins of Health and Disease” (DOHaD) hypothesis. We next review evidence from both human and animal studies that demonstrate developmental origins of adult reproductive dysfunction, and include detailed tabular summaries of this information. Examples of studies documenting mechanisms by which environmental exposures can lead to different types of epigenetic modifications to mediate DOHaD effects are provided. Finally, we review reports exploring the concept of transgenerational epigenetic inheritance of environmental exposures, and point out areas of research ripe for future exploration.

1.1. Timing of reproductive system development

Development of the mammalian reproductive system begins in early pregnancy with specification and migration of germ cells, followed by morphogenesis of the gonads, reproductive tract structures, and external genitalia. As the reproductive tissues form, they differentiate under the influence of numerous molecules including growth factors, transcription factors, and steroid hormones. Gross morphogenesis of reproductive tissues is largely complete before birth, but slow growth and regional and cellular differentiation continue through the onset of puberty. During puberty, a rapid phase of growth and additional structural and cellular reorganization occurs, regulated in large part by steroid hormones.

Some temporal aspects of reproductive system differentiation are distinct in females and males. For example, female germ cells enter meiosis prenatally and complete the initial phases of meiosis before birth, whereas male germ cells only begin to enter meiosis postnatally and continuously do so throughout adulthood. The protracted time period of reproductive system formation, growth, and differentiation creates a wide window of susceptibility to disruption by environmental factors, and because of differences in timing of specific developmental events, this window differs in some aspects between females and males.

1.2. Developmental origin of adult diseases – windows of susceptibility

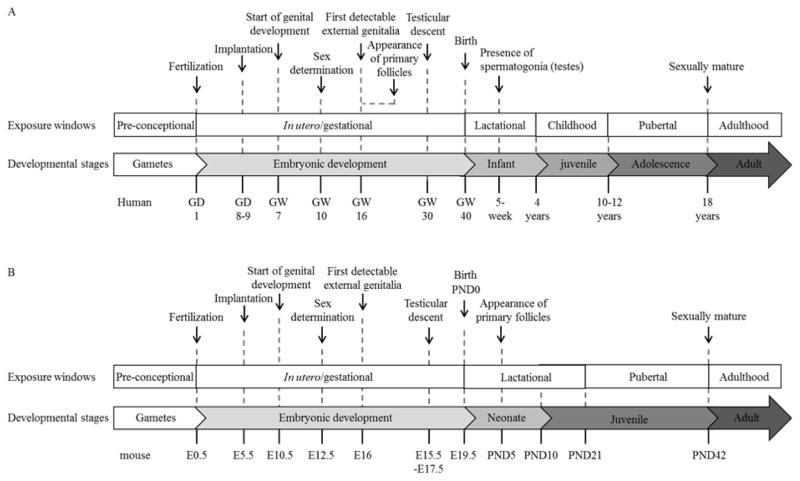

The DOHaD hypothesis proposes that the environment an individual experience during early development, can affect their sensitivity to, or risk of developing, disease later in life [1]. During development, dynamic interplay between the genome, epigenome, and stochastic and environmental factors contributes to the fate of individual cells to form functional organ systems in a “developed” adult state with stably differentiated tissues. That these tissue systems are stably, rather than terminally differentiated, allows for continual maintenance of a critical balance between cell death and proliferation, regeneration, and repair [2]. Most cells or organs have various degrees of phenotypic plasticity, whereby the phenotype expressed by a genotype is dependent on environmental influences [3]. The principle that the nutritional, hormonal, and metabolic environment afforded by the mother may permanently program the structure and physiology of her offspring was established long ago [4]. The DOHaD theory has now advanced to extend the critical developmental temporal windows of tissue reprogramming beyond in utero development to include preconception, perinatal, neonatal, postnatal, and pubertal development [5] (Figure 1). These adaptive traits are usually beneficial to the health of the individual. However, exceptions arise when an individual who is developmentally adapted to one environment is exposed to a contradictory environment [6]. Such exposures include the introduction of new chemicals and pollutants, which may increase the risk of developing disease later in life.

Figure 1.

Critical developmental stages of (A) human and (B) mouse reproductive systems, and windows of susceptibility for tissue reprogramming by environmental exposures. GD indicates gestational day; GW, gestational week; E, embryonic day; and PND, postnatal day.

A prime example is the strong correlation observed between gestational exposure to diethylstilbestrol (DES) and increased female and male reproductive tract structural anomalies including a rare form of cancer, an increased infertility rate and poor pregnancy outcomes in female offspring, and an increased incidence of genital abnormalities and possibly urological cancers in male offspring [7–9]. Fetal exposure to environmental chemicals with estrogenic or anti-androgenic action can disrupt testosterone synthesis and sexual differentiation, leading to adult testis dysfunction and infertility [10–13]. In addition, exposure to endocrine disrupting chemicals (EDCs) during fetal life disrupts female reproductive tract development by altering expression of genes encoding secreted signaling proteins critical for directing this process [14]; these effects have permanent consequences for reproductive tract morphology and function in both rodents and humans [15, 16].

In summary, many of the developmental differentiation events critical for reproductive function, are dependent at least in part on steroid hormone signaling [14, 17–20]. For this reason, exposure to environmental EDCs, during this critical window of reprogramming, may induce profound changes in regulatory signaling pathways, and have a significant impact on development in ways that affect later reproductive health [21]. This concept of DOHaD could easily be extended to other windows of susceptibility, although evidence from epidemiological, clinical, and experimental studies remain sparse for these windows.

1.3. Epigenetics – as a mechanism shaping DOHaD

Epigenetic modifications are defined as heritable changes in gene function that occur without a change in the nucleotide sequence [6, 22–24]. In the context of DOHaD, epigenetics can be viewed as an important “biostat” that allows an organism or a tissue to switch on or off anticipatory gene transcription programs in response to environmental changes, leading to adaptive phenotypic alterations to enhance survival. Gene transcriptional programs are changed in both a functional and temporal context as immediate and long-term responses to environmental cues. DNA methylation, histone modifications, transcription of new micro- and long non-coding RNAs, and other higher order chromatin remodeling events establish new adaptive traits for the tissue or organism. These epigenetic modifications are generated, maintained, and removed by a class of proteins known as “chromatin modifying enzymes”. The expression of these enzymes is exquisitely sensitive to specific environmental changes. Conversely, undesirable inherited or sporadic epimutations [25], or dysregulation of the epigenome in a tissue by harmful environmental disruption, could lead to disease development.

The most well studied epigenetic modification to DNA is methylation of cytosine residues in the context of a CpG (5′-C-phosphate-G-3′) dinucleotide. Methylation of CpG rich regions of DNA generally confers relatively stable silencing of gene expression, whereas unmethylated CpG regions are more accessible to transcription factor binding, which leads to gene transcription [26]. DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs) are primarily responsible for placing methyl groups on CpG dinucleotides, whereas the ten-eleven translocation (TET) family proteins remove methyl groups. DNMT1 is primarily responsible for maintaining CpG methylation once these marks have been established. DNMT3A and DNMT3B carry out de novo DNA methylation, which is important in embryo and tissue development as well as differentiation [27, 28]. Therefore, the proper expression of DNMTs and TETs cannot be overlooked when assessing the impact of the environment on DNA methylation.

To begin to understand how differential methylation impacts gene expression, comparisons are being made between methylation patterns (methylome) and gene expression patterns (transcriptome) in specific disease states. These types of studies will allow us to examine the intersection of DNA methylation and gene expression and how the environment can impact these differences. One study in women analyzed global DNA methylation and gene expression in leiomyoma tissue compared to normal adjacent tissue [29]. In this study, overlap of differential methylation of promoter regions and gene expression was found in 55 genes, and of these, three of them are known tumor suppressor genes that have been implicated in reproductive tract tumorigenesis. Hypomethylation of the promoter regions of these three genes correlated with decreased expression. This study demonstrates that the local environment (tumor vs. normal) also contributes to alterations in methylation patterns adding complexity to the resulting methylome and transcriptome. Of interest, this study also showed that the vast majority of genes with differential expression did not exhibit altered DNA methylation patterns at their promoter regions. This finding indicates other epigenetic mechanisms are involved, in a concerted manner, to control gene expression.

Another way transcription can be controlled epigenetically is the differential association of modified histones at various DNA regions (reviewed by [30]). Histones are closely associated with DNA, and specific residues of the histone tails can be modified with methyl groups, acetyl groups, and many other molecules. To increase the complexity of this regulatory system, there are often different types of modifications to histones at many different residues along their tails. This concert of modified histones associated with specific gene loci often correlates with transcriptional activity [31]. For example, the association of trimethylated histone 3 at lysine 4 (H3K4me3) at the promoter region is usually indicative of an actively transcribing gene. Conversely, trimethylated histone 3 at lysine 27 (H3K27me3) is usually associated with repression of gene expression [32, 33], although neither are exclusive and can co-exist (bivalency; [34]) in a careful balance to place a specific gene in a poised state – ready for transcription by cellular stimulus. Segregation of genes into active, repressed, bivalent, or poised is often achieved by an intricate balance between H3K4me3 and H3K27me3 occupancy as reviewed by Weng et al (2012; [35]). The coordination of DNA methylation and histone modification, to define the transcriptional state and readiness of a cohort of genes, are commonly noted in most physiological and pathological states [36].

In addition to DNA methylation and histone modification, microRNAs (miRs) and other non-coding RNAs can also be dysregulated by EDCs. In a mouse study, prenatal exposure to vinclozolin led to the upregulation of microRNAs such as mir-23b and let-7 in embryonic day (E) 13.5 primordial germ cells [37]. Such microRNA dysregulation was observed in three successive generations, but no prominent DNA methylation changes were found [37]. However, in a similar vinclozolin study in rats, DNA methylation abnormalities and transcriptional changes were observed in the E13 and E16 germ cells [38]. At present, the broad view that EDCs exert long-term effects via the epigenetic action of miRNAs/non-coding RNAs is still under construction, especially in the context of reproductive tract development.

2. Developmental origins of adult reproductive dysfunction associated with environmental factors – evidence from human studies

Human studies detailing female and male developmental origins of adult reproductive dysfunction associated with environmental factors are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Human studies – developmental origins of adult reproductive dysfunction associated with environmental factors.

| Environmental Factor | Exposure Window | Study Details/Observation Window | Phenotype | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | ||||

| DES | In utero (beginning in the first trimester) | 15–22 years of age (n=7/8) | Vaginal clear-cell adenocarcinoma (P<0.00001) | [39, 40] |

| DES | In utero | 16–20 years of age (n=5/6) | Vaginal clear-cell adenocarcinoma | [208] |

| DES | In utero | Diethylstilbestrol Adenosis (DESAD) Project (n=1,655) | Structural anomalies of the cervix or vagina | [47] |

| DES | In utero | Nurses’ Health Study II, prospective cohort study (n=84,446)/25–42 years of age | Endometriosis (RR = 1.8; 95% CI: 1.2–2.8) | [53] |

| DES | In utero | NIEHS Uterine Fibroid Study (n=504 white women)/35–49 years of age | Uterine leiomyoma (OR = 2.4; 95% CI: 1.1–5.4) (n=14/19) | [15] |

| DES | In utero | NIEHS Sister Study (n=19,972 non-Hispanic white women)/35–59 years of age | Greater risk of early fibroid diagnosis (RR = 1.42; 95% CI: 1.13–1.80) | [209] |

| DES | In utero | NIEHS Sister Study (n=3,201 black women)/35–59 years of age | Early-onset uterine fibroids (RR = 2.02; 95% CI: 1.28–3.18) (n=13/42) | [55] |

| DES | In utero (beginning in the first trimester) | Nurses’ Health Study II, prospective cohort study (n=102,164 premenopausal women)/25–42 years of age | Uterine leiomyoma (adjusted HR = 1.21; 95% CI: 1.02–1.43) | [56] |

| DES | In utero | Population-based case-control study (n=310 cases; n=727 controls) | Endometriosis (adjusted OR = 2.0; 95% CI: 0.8–4.9) | [54] |

| PCB | In utero | 8 years of age (n=33) | Greater proportion of shorter fundi lengths (P=0.025), and uteri lengths (P<0.05) | [73] |

| Soy formula | Infancy | Cohort study (females: n=128 soy formula; n=268 cow milk formula)/20–34 years of age | Longer duration of menstrual bleeding (adjusted mean difference, 0.37 days; 95% CI, 0.06–0.68; P=0.02), greater discomfort with menstruation (unadjusted RR = 1.77; 95% CI: 1.04–3.0; (n=23/128) P=0.04) | [51] |

| Soy formula | Infancy | NIEHS Sister Study (n=19,972 non-Hispanic white women)/35–59 years of age | Greater risk of early fibroid diagnosis (RR = 1.25; 95% CI: 0.97–1.61) | [209] |

| Soy formula | Infancy (≤4 months of age) | Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children (ALSPAC) (n=2,920 girls)/8–14.5 years of age | 25% higher risk of menarche (HR = 1.25; 95% CI, 0.92, 1.71) | [62] |

| Soy formula | Infancy | NIEHS Sister Study (n=3,201 black women)/35–59 years of age | Early-onset uterine fibroids (RR = 1.26; 95% CI: 0.83–1.89) (n=19/96) | [55] |

| Soy formula | Infancy | The Black Women’s Health study (n=23,505 premenopausal African-American women)/23–50 years of age | Uterine leiomyoma (IRR = 1.0; 95% CI: 0.86–1.16*) | [59] |

| Soy formula | Infancy | The NIEHS Study of Environment, Lifestyle & Fibroids (SELF) cohort study (n=1,696 African-American women)/23–34 years of age | Uterine fibroid prevalence (adjusted PR = 0.9; 95% CI: 0.7, 1.3*), 32% increase in the diameter of the largest fibroid (95% CI: 6%, 65%), 127% increase in total tumor volume (95% CI: 12%, 358%) | [60] |

| Soy formula | Infancy | Population-based case-control study (n=310 cases; n=727 controls) | Endometriosis (adjusted OR = 2.4; 95% CI 1.2–4.9) | [54] |

| BPA | Adult | Women undergoing IVF (n=174)/18–45 years of age | Decreased number of oocytes (overall and mature) | [69] |

| Male | ||||

| DES | In utero | OMEGA Dutch cohort study (n=4/205 exposed boys; n=8/8,727 unexposed boys) | Increased risk of hypospadias (PR = 21.3; 95% CI: 6.5–70.1) | [80] |

| DES | In utero | Combination US cohort study (n=10/3,916 exposed boys; n=3/1,746 unexposed boys) | Hypospadias prevalence (OR = 1.7; 95% CI: 0.4–6.8) | [81] |

| DES | In utero | Dutch cohort (n=21 exposed men; n=813 unexposed men) | Increased risk of hypospadias (adjusted OR = 2.3; 95% CI: 0.7–7.9) | [79] |

| DES | In utero | Combination cohort study (n=197/1,018 exposed men; n=159/1,018 unexposed men) | Infertility (RR = 1.3; 95% CI: 1.0–1.6) | [82] |

| DES | In utero | Collaborative cohort study (n=1,197 total exposed men; n=1,038 total unexposed men) | Cryptorchidism (RR = 1.9; 95% CI: 1.13.4) (n=38/1197) Epididymal cysts (RR = 2.5; 95% CI: 1.54.3) (n=55/1197) Inflammation/infection of the testes (RR = 2.4; 95% CI: 1.54.4) (n=49/1197) Exposure before 11th week of pregnancy: Cryptorchidism (RR = 2.9; 95% CI: 1.65.2) (n=29/625) Epididymal cyst (RR = 3.5; 95% CI: 2.06.0) (n =38/625) Inflammation/infection of testes (RR = 3.0; 95% CI: 1.75.4) (n=30/625) |

[77] |

| Tobacco smoking particulates | In utero | Cross-sectional European study (n=467/1,770 sons exposed to maternal smoking)/16–27 years of age | 20.1% reduction in sperm concentration (95% CI: 6.8, 33.5), 24.5% reduction in total sperm count (95% CI: 9.5, 39.5), 1.15 ml smaller testis size (95% CI: 0.66, 1.64), 1.85% lower sperm motility (95% CI: 0.46, 3.23), and 0.64% lower morphologically normal sperm (95% CI: −0.02, 1.30) | [90] |

| Tobacco smoking particulates | In utero | Danish “Healthy Habits for Two” cohort (n=347/5,109 sons exposed to maternal smoking)/18–21 years of age | Oligospermia (OR = 2.16; 95% CI: 0.68, 6.87) | [92] |

| PCB; PCDF | In utero | 16–18 years of age (n=12 total exposed men; n=23 total unexposed men) | 37.5% increase in abnormal sperm morphology (P<0.0001), 35.1% reduction in motile sperm (P=0.0058), and 25.5% reduction in rapidly motile sperm (P=0.017) | [93] |

| PFOA; PFOS* | In utero | Danish cohort (n=169)/19–21 years of age | 34% reduction in sperm concentration (P=0.01), and 34% reduction in total sperm count (P=0.001) | [210] |

| Dioxin | Lactation | 18–26 years of age (n=21 breast-fed sons/39) | Decreases in sperm concentration (P=0.002), total sperm count (P=0.02), progressive sperm motility (P=0.03), and total motile sperm count (P=0.01) | [211] |

| TCDD | Infancy (1–9 years), puberty (10–17 years), adulthood* (18–26 years) | 22 years after exposure (n=135 Caucasian men) | Infancy exposure group: decreases in sperm count (P=0.025), progressive sperm motility, (P=0.001), and total number of motile sperm (P=0.01) Puberty exposure group: stimulatory effect on semen parameters |

[91] |

| BPA | Adult | Chinese cohort (n=218 men with and without BPA exposure in the workplace) | Decreases in sperm concentration (adjusted (a)OR = 3.4; 95% CI, 1.4–7.9; P<0.001), total sperm count (aOR = 4.1; 95% CI, 1.7–9.9; P=0.004), sperm viability (aOR = 3.3; 95% CI, 1.4–7.5; P<0.001), and sperm motility (aOR = 2.3; 95% CI, 1.0–5.1; P<0.001) | [212] |

| BPA | Adult | 18–55 years of age (n=190) | Decreases in sperm concentration (adjusted (a)OR = 1.47; 95% CI, 0.85–2.54), total sperm count (aOR = 1.20; 95% CI, 0.71–2.03), sperm motility (aOR = 1.23; 95% CI, 0.83–1.80), and sperm morphology (aOR = 1.25; 95% CI, 0.77–2.06) | [213] |

DES indicates diethylstilbestrol; RR, relative risk; CI, confidence interval; NIEHS, National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences; OR, odds ratio; HR, hazard ratio; PCB, polychlorinated biphenyl;

, reported as not statistically significant;

IRR, incidence rate ratio; PR, Prevalence ratio; BPA, bisphenol A; IVF, in vitro fertilization; PCDF, polychlorinated dibenzofuran; PFOA, perflurorooctanoic acid; PFOS, perfluorooctane sulfonic acid, and TCDD, 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzodioxin.

2.1. Female

DES is a potent synthetic estrogen, historically prescribed to pregnant women during the 1940s–70s to prevent miscarriage. The consequences of exposing pregnant women to DES made clear not only the impact of EDCs on female reproductive tract development, but also the importance of timing of exposure during critical developmental windows in determining the extent of reproductive tract abnormalities. Prenatal DES exposure has been conclusively linked to the development of vaginal clear-cell adenocarcinoma in young female offspring (“DES daughters”) [39, 40], with a higher rate of incidence occurring in association with first trimester exposure [41]. A range of reproductive tract abnormalities have also been observed in DES daughters, including structural abnormalities of the uterus, vaginal adenosis, and malformations of the cervix (reviewed by [42–46]). A higher incidence and higher severity of abnormalities after earlier exposure to higher doses have been documented [47].

Presently, a notable source of exogenous estrogen exposure to humans comes from dietary phytoestrogens [48], most commonly from soybean-derived foods rich in genistein and daidzein. Relatively high levels of these compounds are also found in soy-based infant formulas, consumed by an estimated 12% of infants in the United States (US) [49]. Infants fed an exclusive diet of soy infant formula have urinary genistein concentrations that are 500 times higher than infants who are breast fed, or fed cow milk formula [50]. A number of recent studies have investigated associations between postnatal exposure to soy infant formula and adult female reproductive tract morbidities and symptoms. One study found that women fed soy-based formula as infants reported longer menstrual bleeding and more dysmenorrhea than women who had been fed cow milk formula [51]. This study did not report any association between infant feeding type and other reproductive organ problems such as endometriosis or uterine fibroids, yet notably, excessive bleeding and discomfort are common symptoms of these conditions [52].

DES and soy-based products continue to be studied as early-life factors associated with adult female reproductive health. At 10 years of follow up in a Nurses’ Health Study, the incidence rate of endometriosis was found to be 80% greater among women exposed to DES in utero [53]. A similar result was reported in a population-based case-control study, where both prenatal DES exposure and “regular” soy formula feeding during infancy were associated with an increased risk of surgically confirmed endometriosis [54]. Uterine fibroids have also been associated with these early-life factors, but with some inconsistency. A cohort study of almost 20,000 non-Hispanic white women from the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS) Sister Study, linked use of soy formula during infancy with a slightly increased risk of early uterine fibroid diagnosis [55]. Prenatal DES exposure has also been associated with increased incidence of uterine fibroids [15, 56] and increased risk of early-onset fibroids among non-Hispanic black women [55]. However, other studies have not supported the associations between fibroids and prenatal DES [57] or soy formula [58, 59]. In an ongoing cohort by the NIEHS, no association was observed between infant soy formula feeding and fibroid prevalence in African-American women, aged 23–34 years, who had no diagnosis of fibroids at enrollment [60]. However, soy formula-exposure was associated with a 32% increase in fibroid diameter, and a 127% increase in total fibroid volume [60]. Within this cohort, the data also suggest an association between soy-based infant formula feeding and heavy menstrual bleeding [61].

A common limitation of many of the aforementioned studies is that they rely on the participant’s recall of retrospective exposure. Although prospective studies of prenatal DES exposure are not feasible due to the banning of its use in humans, a number of prospective studies examining the potential effects of soy exposure through soy-based infant feeding are underway. Using data from a longitudinal cohort of children followed from infancy to adolescence, Adgent et al reported a slightly increased risk of menarche in early adolescence in association with soy formula exposure [62]. Another prospective study showed increased estrogenization of vaginal epithelium in soy fed infants compared to cow milk fed infants [63] and a recent follow up study of the same infants showed differential methylation patterns in those vaginal epithelial cells [64]. These findings demonstrate a direct connection in humans between soy formula exposure and temporarily altered epigenetic marks in an estrogen-responsive tissue. Other ongoing studies specifically designed to evaluate the effects of soy formula feeding, compared to breast milk or cow milk formula, on reproductive organ volume and characteristics at 4 months [65] and 5 years [66] of age, have reported no significant differences between the diet groups. Continued follow-up of these cohorts will be important to help delineate potential early infant feeding effects of soy on reproductive function later in life.

Another EDC that has estrogenic and/or anti-androgenic activity is bisphenol A (BPA), one of the highest-volume chemicals produced in the US. BPA is widely used in the manufacture of polycarbonate plastic, epoxy resins and many other consumer products [67] and is readily detected in the urine of over 95% of the US population [68]. Higher urinary BPA levels are associated with a decreased number of oocytes and mature oocytes [69], and recurrence of miscarriages, as well as with women undergoing in vitro fertilization [70]. The mechanisms involved in the development of these reproductive diseases are yet to be fully understood.

In addition to estrogenic and anti-androgenic chemicals, recent population studies have examined the effects of environmental chemicals that disrupt homeostasis of thyroid hormone and growth hormone actions during the prepubertal period [71, 72]. Study findings showed that in utero exposure to higher levels than median of polychlorinated dibenzo-p-dioxins and dibenzofurans (PCDFs) and polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) results in lower estradiol concentrations in eight year-old children, and that girls had impaired reproductive tract development including shorter uteri and fundi lengths [73].

Taken together, these studies suggest that EDCs impact human female reproductive health. Although these studies are beginning to reveal deleterious effects, more extensive studies on EDC exposures and potential consequences on reproduction are warranted.

2.2. Male

According to the National Survey of Family growth, about 12% of men at the reproductive age of 25–44 are subfertile [74]. Although in many cases the etiology remains largely unknown, developmental exposure to environmental agents is emerging as a contributing factor. The impact of environmental estrogens (herbicides, pesticides, PCBs, plasticizers, and polystyrenes) and anti-androgens (polyaromatic hydrocarbons, linuron, vinclozolin, and p,p′-dichlorodiphenyl-dichloroethylene (pp′-DDE)) on male sexual differentiation [75] and the testis [76] have been extensively reviewed, however, literature specific to DOHaD regarding the male reproductive system is limited.

A multi-cohort study of DES-exposed sons [77] showed that prenatal exposure to DES is associated with an increased risk of male urogenital tract abnormalities including cryptorchidism, epididymal cysts, and inflammation/infection of the testis. The association was strongest in men exposed during the first trimester [77]. These findings strongly support that the root cause of disruption is during the period of sexual differentiation, as epididymal cysts are related to the persistence of müllerian remnants, and testicular descent is dependent on the estrogen-sensitive hormone, insulin-like growth factor 3, secreted by the Leydig cells in the fetal testis [78]. Earlier observations [79–81] that gestational exposure to DES elevated risk of hypospadias were not confirmed in this collaborative cohort study. There are conflicting results in the literature regarding whether or not DES-exposed males have an increased risk of infertility [82, 83].

In addition to DES, there is increasing evidence that developmental exposure to BPA affects male reproduction (reviewed by [84]). Of particular concern is the finding that pregnant women have higher urinary BPA levels than non-pregnant women, suggesting that there is higher exposure to the fetus than was once thought [85]. Although maternal blood concentrations of ~2.5 ng/mL versus umbilical cord blood concentrations of ~0.5 ng/mL suggest a certain degree of placental protection, elevated risk of lower birth weight, smaller size for gestational age, higher fetal leptin, and lower adiponectin were observed in male newborns in the highest quartile of maternal BPA exposure [86]. Furthermore, children between the ages of 0 and 2 are now identified as a higher risk population for BPA exposure [87] because they have a lower capacity to metabolize BPA due to low expression of the liver enzyme, uridine 5′-diphospho-glucuronosyltransferases [88]. Therefore, early-life exposure to even low doses of BPA may have a greater impact on adult disease outcomes than anticipated based on dose levels [89].

Similarly, other epidemiological studies have linked in utero exposure to smoking particulates, PCB, PCDF, perfluorooctanoic acid, dioxin, and 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzodioxin (TCDD) to reduced semen concentration, and sperm count [90–92], reduced number of morphologically normal sperm, motile, and rapidly motile sperm [93] and smaller testis [90]. Further, in a small case control study, maternal exposure to higher levels of persistent organic pollutants including PCBs, pp′-DDE, hexachlorobenzene, chlordanes and polybrominated dibenzoethers (PBDEs) was found to be associated with increased testicular cancer risk [94]. Because these chemicals, especially pp′-DDE, are known for their endocrine disruption as anti-androgens, one can speculate that early-life disruption of androgen signaling reprograms cancer risk in testes.

These studies suggest developmental exposures to EDCs impact reproductive health in men as well as women. Again, more studies on EDC exposures to males during critical periods of development and their effects on subsequent reproduction and reproductive disease are warranted.

3. Developmental origins of adult reproductive dysfunction associated with environmental factors – evidence from experimental studies

There have been numerous animal studies documenting the adverse effects of EDCs on the developing female and male reproductive systems. A comprehensive list of these studies, which thoroughly validate the concept of developmental origins of reproductive dysfunction associated with environmental factors, are provided in Table 2.

Table 2.

Animal studies – developmental origins of reproductive dysfunction associated with environmental factors.

| Species | Exposure | Observation | Dysregulated gene(s) | Epigenetic mechanism | Reference | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dose and agent | Window | Route | Window (Age) | Phenotype | ||||

| Female | ||||||||

| CD-1 mouse | 50 mg/kg/day GEN | PND1–5 | s.c. injection | 3 weeks | Clitoris was abnormally widened and erythematous; urethral opening was located at varying positions on the ventral aspect of the clitoris | Not studied | Not studied | [95] |

| 6 weeks | Clitoris was less erythrmatous, urethra opening was abnormally positioned | [95] | ||||||

| CD-1 mouse | 0, 0.002 – 2 μg/pup/day DES | PND1–5 | s.c. injection | 12 months | Cystic endometrial hyperplasia, uterine endometrial adenocarcinoma | Not studied | Not studied | [96] |

| CD-1 mouse | 0 or100 μg/kg BW DES | GD9–16 | s.c. injection | 1 and 18 months | Vaginal adenosis and adenocarinoma | [97] | ||

| 0, 5, 10, and100 μg/kg BW DES | GD9–16 | s.c. injection | 1 month | Vaginal adenosis | [97] | |||

| zebrafish | 2.76 ng/L or 9.86 ng/L EE | 20–60 dpf | Environmental | 485 dpf | Reduced percentage of surviving embryos with high EE dose Reduced effectiveness in attracting male attention with high EE |

Not studied | Not studied | [125] |

| SD rats | 40 μg/kg BW BPA | Gestation and lactation | Oral | PND35 and 45 | Increased investigations of partners, exploration of environment, air smelling, and rearing | Not studied | Not studied | [126] |

| PND45 | Reduced play behavior with males, pounce, and chasing males Reduced social behavior and social grooming (aggressive and allo-grooming) |

[126] | ||||||

| FVB mice | 0, 0.5, 20, or 50 μg/kg BW/day BPA 0.05 μg/kg BW/day DES |

GD11 till birth | Oral gavage | PND4 | Increased number of germ cells to remain in nests Reduced number of primordial follicles with all BPA doses |

Decreased expression of Bax, Tnfrsf11b, Tnfrsf1a, Tnfdf12, and Ltbr with 0.5 μg/kg BW/day BPA; Increased expression of Bcl2l1 and decreased expression of Bax, Bak1, and Tnfrsf11b with 20 μg/kg BW/day BPA; Increased expression of Bcl2, Bcl2l1, and decreased expression of Bak1, Tnfrsf11b, Tnfrsf1a, Tnfdf12, and Ltbr with 50 μg/kg BW/day BPA |

Not studied | [112] |

| After PND21 | Earlier vaginal opening with DES Shorter time between vaginal opening and first estrus with DES and 50 μg/kg/day BPA |

[112] | ||||||

| 3 months | Increased number of dead pups with 0.5 μg/kg BW BPA | |||||||

| 6 months | Reduced litter size with 50 μg/kg BW BPA | |||||||

| 9 months | Only one out of five females with exposure to 0.5 μg/kg BW BPA gave birth and with no live pups | [112] | ||||||

| C57BL/6 mice | 1 mg/kg BW BaP or DMBA | Preconception: once a week for three weeks; Gestation: no treatment; Lactation: third day after birth and then once a week for three weeks |

s.c. injection | 3 weeks | Reduced number of primordial and primary follicles either either pregnancy or lactational exposure to PAH Follicular depletion with prepregnancy and lactational exposure of BaP |

Within 24 hours of exposure: Increased expression of Hrk with PAH exposure | Not studied | [107] |

| Sullfolk ewes | 100 mg testosterone | GD30–90, twice weekly | i.m. injection | GD140 | Reduced fetal growth Reduced uterus weight with T Reduced number of developed follicles per animal with T Reduced total number of follicles and primordial follicles with T Increased overall total number of primary,, small preantral, preantral, and antral follicles with T |

Not studied | Not studied | [214] |

| Wistar-derived rats | 0.2 or 20 μg/kg/day DES 0, 0.05, or 20 mg/kg/day BPA |

PND1, 3, 5, and 7 | s.c. injection | GD18 | Lack of mature follicles and functional corpus luteum, and no mating behavior with 20 μg/kg/day DES Reduced number of implantation sites with 0.2 μg/kg/day DES and 20 mg/kg/day BPA Reduced number of pregnant females with 0.2 μg/kg/day DES and 0.5 or 20 mg/kg BW BPA |

On GD5: Decreased expression of Hox10a with DES and BPA exposure; Reduced expression of Itgb3 and increased expression of Emx2 with 0.2 μg/kg/day DES and 20 mg/kg/day BPA |

Not studied | [110] |

| CD-1 mice | 5 mg/kg BPA | GD9–16 | i.p. injection | 2 weeks | Not studied | Increased expression of Hox10a | Promoter and intronic hypomethylation | [140] |

| FVB mice | 0.05 μg/kg/day DES 0, 0.5, 20, and 50 μg/kg/day BPA |

GD11 till birth | Oral | 9 months | Reduced pregnancy rate with all doses of BPA | Not studied | Not studied | [215] |

| CD-1 mice | 0 or 1 mg/kg/day DES | PND1–5 | s.c. injection | PND5 | Not studied | Increased expression of Ltf and Six1 | Recruitment of H3K9ac, H4K5ac and H3K4me3 in exon1/intron1 region of Six1 | [146] |

| CD-1 mice | 0 or 2 μg/mouse/day DES | PND1–5 | s.c. injection | 17, 21, and 30 days | Not studied | Increased expression of Ltf | Hypomethylati on at three CpG sites upstream of Ltf | [137] |

| CD-1 mice | 0 or 10 μg/kg BW DES | GD9–16 | i.p. injection | 2 weeks | Not studied | Increased expression of Hoxa10 in the caudal region, with decreased expression in the cranial area of the uterus | Hypermethylation at the promoter and intronic regions | [139] |

| Male | ||||||||

| Wistar rats | 0, 60, or 300 μg/kg BW PBDE-99 | GD6 | Oral gavage | PND140 | Smaller testes and reduced epididymis weight Reduced testicular spermatid count and sperm count from caudal epididymis Reduced daily sperm production with normal sperm morphology Reduced incidence of having two or more ejaculations during 20 minutes of mating with all doses of PBDE-99 |

Not studied | Not studied | [119] |

| CD-1 mice | 0 or 100 μg/kg BW DES | GD9–16 | s.c. injection | 7 months | Sterility | Not studied | Not studied | [123] |

| 9–10 months | Intra-abdominal testes, testicular lesions, and epididymal cysts | [123] | ||||||

| SD rats | 0.064, 0.16, 0.4, 1, or 2000 μg/kg BW TCDD | GD15 | Oral | PND32 | Reduced testis weight with the lowest and the two highest doses of TCDD | Not studied | Not studied | [120] |

| PND49 and 63 | Reduced testis weight with the higher doses | [120, 121] | ||||||

| PND32, 49, 63, and 120 | Reduced epididymis weight with the highest dose | [120] | ||||||

| PND120 | Reduced epididymis weight with the lowest dose | [120] | ||||||

| PND49 | Reduced daily sperm production with doses from 0.16 μg/kg BW | [120] | ||||||

| PND63 and 120 | Reduced daily sperm production with doses from 0.064 μg/kg BW | [120] | ||||||

| SD rats | 0, 0.064, 0.16, 0.4, or 1 μg/kg BW TCDD | GD15 | Oral | PND49 and 120 | Reduced weight of seminal vesicles with 0.16 μg/kg BW TCDD | Not studied | Not studied | [121] |

| PND32 and 120 | Reduced weight of ventral prostate with 0.064 μg/kg BW TCDD | |||||||

| Long Evans Hooded rats | 0, 0.05, 0.2, and 0.8 μg/kg BW TCDD | GD15 | Oral gavage | PND49 | Reduced weight of seminal vesicle and ventral prostate with 0.8 and 1 μg/kg BW TCDD Reduced total epididymal sperm count with 0.8 and 1 μg/kg BW TCDD |

[216] | ||

| 15 months | Reduced caudal epididymal sperm count with 0.2 and 0.8 μg/kg BW TCDD Reduced caudal epididymal sperm count with 0.05, 0.2 and 0.8 μg/kg BW TCDD |

[216] | ||||||

| C57BL/6 mice | 0, 0.1, 1, 10 μg/kg BW DES | GD12-PND20 | Oral gavage | PND21, 105, and 315 | Reduced number of sertoli cells per testis | PND21: Expression of Cyp17, Cyp11a, Star were decreased with 10 μg/BW DES PND105 and 315: Expression of Esr1 was decreased on with 1 μg/kg BW DES and undetectable with 10 μg/kg BW |

Not studied | [122] |

| PND315 | Reduced caudal epididymal sperm count, Increased beat-cross frequency of sperm with 1 and 10 μg/kg DES |

[122] | ||||||

| PND105 and 315 | Reduction in the number of motile sperm, and sperm motility, velocity, linearity, and ALH displacement Reduction in sperm fertilizing ability and number of embryos reaching 2-cell stage with 1 μg/kg BW DES Increase in sperm fertilizing ability with 0.1 μg/kg BW DES |

[122] | ||||||

| SD rats | 0, 12.5, 25, 50, 100 mg/kg BW GEN and 2 mg/kg BW EE | PND1–5 | Oral | 7 weeks | Reduced number of germ cells in seminiferous tubules | Not studied | Not studied | [124] |

| 18 weeks | Severe atrophy of testes and epidydimis with 100 mg/kg GEN Reduced paired epididymal weight with all doses of GEN |

[124] | ||||||

GEN indicates genistein; PND, postnatal day; s.c., subcutaneous; DES, diethylstilbestrol; BW, body weight; GD, gestational day; EE, ethinyl estradiol; dpf, day post-fertilization; SD Sprague-Dawley; BPA, bisphenol A; BaP, benzo(a)pyrene; DMBA, 7,12-Dimethylbenz[a]anthracene; PAH, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon; i.m., intramuscular; T, testosterone; i.p., intraperitoneal; H3K9ac, acetylated histone 3 at lysine 9; H4K5ac, acetylated histone 4 at lysine 5; H3K4me3, trimethylated histone 3 at lysine 4; PBDE-99, 2,2′,4,4′,5-pentabromodiphenyl ether; TCDD, 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin; and ALH, amplitude of lateral head.

3.1. Reproductive tract

There are numerous animal studies documenting that environmental factors strongly influence reproductive tract development and function. Indeed, studies performed on reproductive tract tissues highlight the importance of the timing of exposure to the outcome. In general, a differentiating tissue is more at risk of re-programming than a fully differentiated tissue. One example in support of this thesis is the effect of neonatal exposure to genistein on external genitalia development in the mouse. Female mice complete formation of the urethra during the first several days following birth, when the urethral folds arising from urogenital sinus mesenchymal cells undergo fusion. If female mice are exposed to genistein during the first five days of life, they fail to complete urethral fold fusion and as a result, develop hypospadias [95]. Urethral formation in male mice, which is completed prior to birth, is unaffected by this treatment. These findings are in concordance with human studies (see above) that show DES exposure during the first trimester, when sex differentiation takes place, inflicts higher incidences of abnormalities in the male and female reproductive tract of offspring [41, 77].

In addition, a tissue that is actively proliferating to generate additional cells required to form the developing structure will respond differently to an insult as compared to a tissue that has already generated many of the required cells and is undergoing a differentiation process. One example to support this notion is that exposure of female mice to DES prenatally, during the period of major organogenesis of the reproductive tract, results in numerous gross morphological abnormalities of the reproductive tract and rare uterine adenocarcinomas, whereas DES exposure immediately after birth does not significantly affect gross morphology, but instead causes a high incidence of endometrial [96] and vaginal [97] adenocarcinoma. Hence, the developmental context of a tissue is a critical driver of outcomes related to environmental exposures.

Prolonged developmental plasticity of a tissue can be an underlying cause of adult disease development linked to early-life exposures [98, 99]. Tissue recombination studies highlight the plasticity of the female reproductive tract epithelium during differentiation. When paired with vaginal mesenchyme, uterine epithelial cells from neonatal mice will transdifferentiate to become morphologically similar to vaginal epithelial cells and express vaginal cell markers; a similar effect is observed when vaginal epithelium is paired with uterine epithelium [100–103]. Although the developmental plasticity of the female reproductive tract epithelium gradually decreases following birth, uterine and vaginal epithelium from two month old mice can still be transdifferentiated, albeit to a lesser extent than neonatal tissue [103], indicating that this tissue is in a stably (not permanently) differentiated state and suggesting that the window for reprogramming in this epithelium is well-extended into adulthood. This phenomenon has been well characterized in other tissues; most notably, neuroplasticity and hence behavior is well-extended into adulthood making the brain a highly sensitive organ for developmental reprogramming [104].

3.2. Ovary

Ovarian differentiation is clearly impacted by EDC exposure, with the outcome dependent on the stage of ovarian development when the exposure occurs. The number of female germ cells, which comprises the “ovarian reserve”, reaches its peak during gestation and continues to decline during the reproductive lifespan of female mammals [105, 106]. It is now established that the ovarian reserve is established during gestation through a complex interplay between homeobox transcriptional factors, hormones, and genetic determinants, a process that can be disrupted by environmental factors through multiple mechanisms (reviewed by [105]). Some toxicants exert their action through induction of apoptosis during the breakdown of the germ cell nest, a critical step for establishing primordial follicles. Exposure to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), key toxicants in cigarette smoke, before pregnancy and/or during lactation reduces ovarian reserve in female mouse offspring through aryl receptor-mediated dysregulation of the cell death gene named harakiri [107]. In utero exposure to BPA similarly reduces the number of primordial follicles in mice. Other disruptors of ovarian reserve impact meiosis I progression in oocytes and reduce the overall primordial follicle pool in the developing ovaries as shown in prenatal BPA exposed offspring [108].

After gestation, the limited number of ovarian follicles are still susceptible to depletion by exposure to a wide-range of toxicants including DES, BPA, and genistein (reviewed by [109]). Further, postnatal exposure to DES induces the loss of mature follicles and functional corpora lutea in the ovaries of adult females [110]. The same treatment also reduces the mating preferences of these females, leading to infertility. In addition to targeting ovarian reserve, in utero exposure to EDCs (DES or BPA) decreases embryo implantation and increases embryo resorption [110].

Prenatal and postnatal exposure to androgen can cause anovulation [111], but whether the window of susceptibility remains open in later-life remains unclear. A recent study compared reproductive outcomes in female CD-1 mice given a single injection of a physiologically relevant dose of testosterone, 24 hours after birth or at the age of weaning (3–6 weeks) [111]. While a large percentage (66%) of the neonatally treated animals developed irregular cycles, were anovulatory, and had higher ovarian weights, none of these reproductive dysfunctions were observed in animals treated at the more advanced age period. This study indicates that the window of susceptibility of the ovary to reprogramming by environmental androgen mimics is similar to estrogens and occurs in differentiating tissues rather than adult tissues.

A consequence of altered ovarian function is altered hypothalamic/pituitary/gonadal signaling, which results in improper hormonal regulation of reproductive tract function. In fact, irregular cycles are a common symptom of prenatal exposure to EDCs or other infertility factors. This connection is difficult to document in humans because of the timing of exposure (developmental) and the latency between the exposure and the outcome (adulthood). In mice, in utero exposure to DES or BPA from gestational day (GD)11 until birth shortens the time between vaginal opening and the first estrus cycle [112]. Moreover, the exposures decrease the time in proestrus, and extends the time in metestrus. Because mating occurs precisely at estrus when ovulation occurs [113], the shortened estrus diminishes successful fertilization.

3.3. Testis

Male rodents have shown significant DOHaD effects for a number of EDCs including BPA. The finding that BPA is detectable in the fetal serum 30 minutes after the first single subcutaneous injection of BPA in GD17 mice [114] indicates that this agent can diffuse across the maternal placental barrier, exposing the fetuses to BPA. Furthermore, the liver enzymes responsible for BPA elimination are either absent or expressed at low levels during the fetal and neonatal period [115], making early-life more susceptible to the impact of this EDC. Neonatal exposure of male rats to BPA is associated with elevated risk of prostate premalignant lesions [116–118]. Multiple studies confirm the potent effects of gestational exposure to environmentally relevant doses of BPA on impairing testicular functions (reviewed by [84]). This xenoestrogen was found to signal through estrogen receptor (ER)α and G-protein coupled estrogen receptor 1 (GPER1) to affect spermatogonial cell proliferation and syntheses of steroidogenesis enzymes in the testis, resulting in systemic endocrine disruption. Mice exposed to BPA also exhibit disruption of ERα and ERβ expression at the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis.

Transient in utero exposure to other estrogenic EDCs such as polybrominated diphenylethers (PBE) and TCDD decreased the weight of the testes and accessory glands of the adult male rat [119–121]. These treatments consistently reduced the number of spermatids in the testes, caudal epididymal sperm count, and daily sperm production, although sperm morphology and motility were within the normal range [119, 120]. Importantly, the overall fertility of the TCDD-exposed males declined, as indicated by a marked reduction in impregnated females with successive mating [120]. Similarly, exposure of mice to DES from GD12, and during lactation, significantly diminished the number of Sertoli cells and the epididymal sperm count in the adult mice [122]. These treatment regimens also reduced sperm motility and quality leading to a decrease in fertilization ability. Resulting zygotes were mostly arrested at the 2-cell stage, which accounted for the higher incidence of preimplantation embryo loss [122]. In another study, exposure of mice to DES from GD9 to 16 inhibited testicular descent and induced testicular lesions and/or epididymal cysts, leading to sterility in the offspring [123]. The developmental impact of the phytoestrogen genistein mimics that of DES. Neonatal exposure (postnatal day, PND 1–5) to genistein reduced epididymal weight and the number of germ cells in the seminiferous tubules [124]. However, in utero exposure to genistein did not affect sperm quality. The latter finding again demonstrates that the window of exposure is an important determinant of outcomes.

3.4. Mating Behavior

Abnormal social and sexual behavior linked to early-life exposure to environmental toxicants affects reproduction. Exposure to ethinyl estradiol on day 20 to 60 post-fertilization causes the adult female zebrafish to be less attractive to the males during their spawning period [125]. Gestational and lactational exposure to BPA also increases the likelihood of female rats to investigate their partners and explore the new environment, but they are more reluctant to interact with their male mating partners [126]. Sexual behavior impairments were also observed in adult male rats prenatally exposed to PBE as they exhibited reduced ejaculation frequency during mating time [119]. Prenatal exposure to chlorpyrifo, an organophosphate insecticide, delayed neonatal motor maturation and altered sexual/mating behavior of male mice [127]. Adolescent exposure of male hamsters to anabolic/androgenic steroids promotes aggression and anxiety in adult-life [128]. Exposure of adult male mice to BPA suppressed sexual motivation and performance [129]. Other environmental agents that perturb sexual behavior include fluoxetine [130], diesel exhaust [131], PBDE and PCB [132], and a long list of environmental toxicants/pollutants (reviewed by [104]). The modes of action appear to be wide ranging, including acting as anti-androgens/androgens, activation of steroid hormone receptors [133], and inhibition of activation enzymes such as aromatase [134]. Other neuronal targets may include disruption of the melanocortical axis, and oxytocin/vasopressin signaling [133].

4. Epigenetics as a mediator of DOHaD

Upon fertilization, massive epigenetic modifications take place to erase the parental epigenetic marks while concomitantly building new marks in the totipotent zygote. As the pluripotent embryonic stem cells differentiate into distinct cell types, each with a unique epigenome, increased cellular differentiation leads to progressive chromatin restriction and loss of cellular plasticity in stably differentiated cells of an adult tissue [135, 136]. The process is accomplished through careful orchestration of epigenetic alterations leading to chromatin compaction and tissue-specification in various organs. The requirement of a high degree of spatial and temporal coordination provides opportunities for disruption by environmental chemicals. Although many molecular mechanisms are possible (see Section 1.3), a few examples are provided here to demonstrate how exposure to specific environmental factors can lead to stepwise changes in epigenetic status and thereby functional alterations.

4.1. DNA methylation

Several studies have demonstrated the impact of developmental exposure to EDCs on DNA methylation patterns in female reproductive tissues. A paper from almost two decades ago showed that neonatal exposure to DES results in hypomethylation of specific CpGs in the promoter region of the lactoferrin (Ltf) gene [137]. Ltf is normally an estrogen responsive gene in the uterus, but DES-induced hypomethylation was correlated with aberrant expression of Ltf in the absence of estrogen throughout life, suggesting that a permanent alteration in the hormone responsiveness of the gene had occurred. A subsequent study using the same model examined uterine DNA methylation pattern differences in a non-biased way [138]. Several gene promoter regions were found to have differential methylation following neonatal DES or genistein exposure; one of these was Nsbp1 (now named Hmgn5), a protein that plays a role in chromatin compaction. The promoter region of this gene was hypomethylated later in life (6 months of age) following developmental exposure to either DES or genistein, and this was correlated with aberrant over-expression of uterine Nsbp1. Prenatal DES exposure results in hypermethylation of the Homeobox (Hox)a10 promoter that correlates with a decrease in gene expression [139]. In contrast, prenatal BPA exposure increases Hoxa10 expression through promoter hypomethylation [140]. HOXA10 is an important regulator of embryo implantation in the uterus and its expression is altered in a number of female reproductive tract pathologies including endometriosis and endometrial cancer [141–143]. Therefore, alterations in methylation patterns of these genes impacts their expression, and subsequently alters adult reproductive function. The specific examples given above are based on candidate approaches, but future global DNA methylation studies correlated with gene expression analysis will most likely reveal many more genes controlled in this manner.

4.2. Histone modification

In addition to altered DNA methylation, EDC exposure during development impacts histone methylation. For example, rats treated postnatally with DES or genistein develop uterine leiomyomas by 16 months of age [144]. During the time of treatment, there is decreased global H3K27me3 in the uterus, which is attributed to increased phosphorylation of enhancer of zeste 2 (EZH2). EZH2 is a subunit of the polycomb repressive complex 2, a histone methyltransferase responsible for methylating H3K27. Because histone H3K27me3 is predominantly associated with repressed genes, it was hypothesized that there would be an increase in expression of some genes due to low levels of H3K27me3. Differential expression of a few selected estrogen-responsive genes was observed during the time of treatment, and a subset were permanently altered in response to estrogen later in life. While this study does not definitively prove that lowering H3K27me3 levels results in leiomyoma formation, it does demonstrate the influence of developmental exposures to EDCs on epigenetic machinery and suggests this mechanism as a potential point of interference.

Another example of EDC impact on the epigenetic machinery comes from a recent study from our laboratory. Neonatal exposure to DES or genistein in mice causes uterine cancer later in life, but the mechanism responsible for this phenotype is not known. Estrogenic action is required because deletion of estrogen receptor alpha (Esr1) completely blocks DES induced changes [145], but the mechanisms underlying permanent alterations in gene expression have not been delineated. We demonstrated that mice treated neonatally with DES exhibited alterations in several parts of the epigenetic machinery [146]. The most striking findings were a severe reduction in the histone deacetylase (HDAC1, HDAC2, and HDAC3) protein levels and a modest reduction in the histone acetyltransferase, EZH2, during the time of treatment (PND1–5). Although these proteins were altered, no global differences in overall amount of histone acetylation at specific residues [acetylated histone 3 at lysine 9 (H3K9ac) or acetylated histone 4 at lysine 5 (H4K5ac)] were observed. There was also a significant reduction in the histone acetylase, lysine acetyltransferase 2A, but no correlated difference in global histone methylation [H3K4me3, dimethylated histone 3 at lysine 9 (H3K9me2) or H3K27me3). However, there were significant differences in the locus-specific association of H3K4me3, H3K9ac and H4K5ac at the promoter regions of two highly differentially expressed genes, Ltf and Six1. In addition, the differential association of these activating marks at the promoter region of Six1 remained in adulthood, suggesting that permanent alterations in the epigenetic landscape resulted in aberrant expression of this gene throughout life. Importantly, overexpression of SIX1 is associated with several cancers including breast, uterine and cervical cancer [147, 148]. Future investigations are needed to elucidate the rules governing recruitment of these chromatin-modifiers to specific gene promoters, transcriptional factor binding sites, and enhancer/silencer elements during developmental reprogramming by environmental agents.

4.3. Methyl donors

One-carbon metabolism during pregnancy has a major impact on fetal development and the setting of methylation marks. Inadequate dietary intake of specific nutrients (folate, choline, betaine, B vitamins) impairs one-carbon metabolism, which in turn results in diminished availability of the methylation substrate, S-adenosyl methionine (SAM). SAM is required for the establishment and maintenance of both DNA and histone methylation marks during fetal differentiation [149]. Because DNA methylation is a common mechanism for stable repression of transposable elements and for the establishment of tissue-specific gene expression along a differentiation pathway, SAM depletion in the fetus has a direct connection to how tissues differentiate and eventually function [150]. For example, in the mouse, supplementation of maternal diet with methyl donors ameliorates BPA-induced hypomethylation of the agouti gene promoter [151]. Hence, nutritional influence on methyl donor availability provides a mechanistic basis for developmental changes in epigenetic marks that can impact reproductive function in adults.

4.4. Alterations in chromatin remodeling proteins

Another point of impact of EDCs on reproductive function is altered gene expression/repression. These alterations can directly or indirectly alter the levels of specific chromatin remodeling proteins within the cell or tissue, and as a result can modify the generation, removal, and maintenance of DNA methylation or specific histone marks. Neonatal BPA exposure elevates gene expression of specific DNA methylation enzymes (Dnmt1 and Dnmt3b) and methyl-CpG binding proteins (Mbd2, Mbd4) in PND10 prostate tissues [118]. Similarly, neonatal exposure to DES alters the expression of Dnmt3a, Dnmt3b, and Mbd2 in seminal vesicles [152]. Concordant aberrant methylation of gene promoters such as Hmgn5, Pde4d and Hpcal1 in adult prostate [116, 118] alters the expression and/or activities of DNA methylation enzymes or methyl-CpG binding protein gene expression through developmental reprogramming. Further studies of EDC-induced global alterations in chromatin modifying proteins and the resulting gene-associated epigenetic modifications, along with the effects on gene expression, are needed to fully understand the impact of these exposures.

Transcription factors that regulate differentiation during development are frequent targets of hormone action. Many hormonally active compounds interact with nuclear receptors to initiate rapid induction of alterations in gene expression, which are comprised of both transcriptional activation and repression. HOX transcription factors regulate the regional identity of tissues along the anterior-to-posterior body axis, including the male and female reproductive tracts. Expression of many HOX genes is altered by exposure to hormonally active chemicals, including estrogens, retinoic acid, and vitamin D, all of which interact with nuclear receptors to mediate their downstream effects [153]. These alterations in gene expression are accompanied by changes in histone modifications in the relevant gene loci as well as in enhancer regions regulating those loci. The new histone modifications can then be maintained and extended by chromatin remodeling proteins whose role is to perform maintenance activities for the histone marks. The end result is that the initial insult leads to stable alterations in expression of transcription factors that change the final differentiation status and function of the tissue.

5. Transgenerational epigenetic inheritance of environmental exposures in reproduction

5.1. Transgenerational inheritance in reproduction – evidence from animal models

Environmentally-induced transgenerational epigenetic inheritance is defined as germline transmission of modified epigenetic information across generations in the absence of continued direct exposures [154]. Conclusive evidence of transgenerational effects of in utero exposure to environmental factors requires changes to persist through and beyond the Filial (F)3 generation – the great grand-offspring of the originally exposed generation – the first unexposed generation. For exposure occurring outside of pregnancy, transgenerational inheritance must persist through the F2 generation that has had no prior exposure.

Transgenerational effects of EDCs on the male reproductive system was first reported by Skinner et al in a series of studies involving exposure of pregnant dams to vinclozolin [155–161]. Adverse transgenerational effects on male germ cells, testicular functions, and male fertility, accompanied by epigenomic (DNA methylation) and gene expression changes were observed in Sertoli cells of F3 or F4 generations derived from exposed F0 dams. Similar transgenerational impacts on the sperm and testis were also observed in animal models for ancestral exposure to a mixture of pesticide permethrin and insect repellent N,N-diethyl-meta-toluamide (DEET) [162], insecticide dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (DDT) [163], a mixture of BPA, bis(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate (DEHP) and dibutyl phthalate [164], BPA [165], DEHP [166], benzo(a)pyrene [167], and TCDD [168, 169]. Furthermore, prostate abnormalities, including epithelial hyperplasia, glandular atrophy and prostatitis, were observed in the ventral prostate of older F3/F4 generation rats and mice derived from F0 exposure to vinclozolin [170, 171]. The altered prostate phenotype was accompanied by transgenerational reprogramming of the expression of calcium and WNT signaling pathways [170]. In contrast, DDT-, plastic-, dioxin- or jet fuel exposures only elicit intergenerational effects on prostate disorders that appears in the F1 generation [163, 164, 172, 173]. Finally, male-mediated transgenerational behavioral changes were also observed in rats with ancestral exposure to vinclozolin [174]. Female rats, from control or exposed ancestors, avoided mating with males from the vinclozolin-lineage and preferred those from the control lineage. In contrast, males from both lineages exhibited no mate preference for females. Collectively, these findings demonstrate that transgenerational inheritance is specific to environmental pollutants and may affect multiple reproductive organs in subsequent generations of offspring even when the exposure has ceased.

5.2. Postulated mechanisms of environmentally-induced transgenerational epigenetic inheritance – heritable germline epigenome alterations

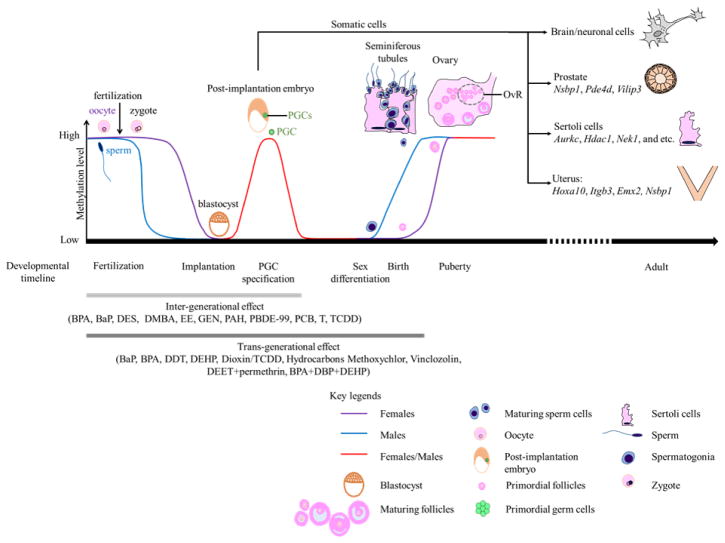

Epigenetic reprogramming has been proposed as the mechanism underlying transgenerational inheritance of reproductive dysfunction. A critical window of susceptibility has been identified to be during gonadal sex determination, a period marked by rapid and genome-wide DNA demethylation (Figure 2). Subsequent re-establishment of the DNA methylation marks is initiated during testicular and ovarian maturation [175–177]. Offspring (F3/F4) derived from pregnant F0 females exposed to vinclozolin during this window, from E8–E14 in rat [160, 161, 178, 179] or E7–E13 in mouse [171] displayed the most persistent transgenerational changes. Persistent changes in transcriptome and DNA methylome of male primordial germ cells in the F3 generation were reported [38]. Alterations in mature sperm DNA methylome were detected with the same period of exposure to vinclozolin [180], methoxychlor [181], pesticides (permethrin and DEET) [162], plastic chemicals (BPA and phthalates), dioxin, and hydrocarbons [172]. Thus, the period during gonadal sex determination is recognized as highly sensitive to transgenerational epigenetic reprogramming by environmental toxicants.

Figure 2.

Environmental exposures induce dynamic methylome changes during post-zygotic and primordial germ cell (PGC) development resulting in inter- and trans-generational inheritance. The first phase is the rapid erasure of methylation marks in the male (blue line) and female (purple line) germline, that occurs shortly after fertilization. It is followed by the establishment of a new methylome in the implanting blastocyst. Progressive chromatin restriction gives rise to differentiated tissues. Environmental agents induce unique gene promoter methylation changes in different tissues. The second phase launched during sexual differentiation through birth establishes the sperm- and oocyte- specific heritable marks. Ovarian reserve (OvR) is determined at birth while male germ cells are replenished throughout life. Inter-generational transmission (light grey line) largely involves the first phase while transgenerational inheritance (dark grey line) requires both phases.

Germline epigenetic marks are transmitted across generations, because they resist epigenetic erasure and resetting during post-zygotic embryogenesis and germline differentiation (Figure 2). It has been proposed that ancestral vinclozolin-induced differential methylation regions in sperm of F3 offspring may represent DNA demethylation escapees and are candidates of transgenerational epigenetic inheritance [172, 182]. Demethylation-resistant loci, including some classes of retrotransposons, have been identified in human and mouse germ cells [183–187]. Some escapees were incompletely reprogrammed in primordial germ cells, mature gametes, and preimplantation embryos [185, 187]. As such, these resistant loci may be vulnerable to environmental reprogramming, and become inheritable.

Evidence for the role of histone modification in transgenerational inheritance is currently lacking. This may be due to the rapid nature of histone modifications needed for chromatin remodeling during embryonic and germline development [183]. Another mechanism enabling epigenetic reprogramming in sperm [188] and oocytes [189–191] involves small noncoding RNA (sncRNA) populations including PIWI-interacting RNAs (piRNAs), microRNAs (miRNAs), nuclear sncRNAs [192], and endogenous small interfering RNAs (endo-siRNAs). These RNAs have now been implicated in gamete-mediated transgenerational epigenetic inheritance [183, 193–196]. Small RNAs, like piRNAs and endo-siRNAs, can serve as “sequence guides” to direct DNA methylation machinery or chromatin/histone modification complexes for targeting specific genomic loci [197]. The unique sequence of sncRNAs ensures the site-specificity of de novo epigenetic silencing being achieved. Additionally, piRNA is an effector for silencing of transposons in mammalian germ cells [198] and for establishing sequence-specific paternal DNA methylation imprinting during germline reprogramming in the mouse [199]. Endo-siRNA has now been shown to direct loci-specific histone H3K9 methylation and gene silencing through recruitment of H3K9 methyltransferase complexes in yeast [200].

The sperm-borne miRNA profiles are sensitive to various environmental exposures/conditions including paternal obesity in mice [201], and chronic stress in male mice [196, 202]. Such changes in sperm miRNA content correlated with transgenerational behavior and metabolic outcomes [201, 202]. Injection of stress-induced sperm miRNAs [196] or sperm total RNAs isolated from stressed males [202] recapitulated the offspring phenotype. Recently, ancestral exposure to vinclozolin induced transgenerational changes in specific miRNAs in primordial germ cells in F1 to F3 generations [37]. Information on the role of oocyte-borne sncRNAs in environmentally induced transgenerational phenomena is absent and warrants future investigations.

Although early life environmental exposures appear to impact reproductive systems across multiple generations in animal models, it remains controversial as to whether these transgenerational effects are mediated via epigenetics [178, 203–206]. Hence, when interpreting data, other factors, such as exposure-induced changes in intrauterine environment and/or maternal behavior, must be taken into consideration due to their influence on offspring phenotypes [206]. Increasing challenges are anticipated in establishing transgenerational epigenetic inheritance in humans. Differences in epigenomes between mice and humans may not allow a direct extrapolation of data from mouse models [207]. Additionally, genetics may contribute to changing the epigenetic landscape through multiple human generations [207]. Therefore, genetic variations in human populations will always be confounding factor for studying transgenerational epigenetic inheritance in humans [206]. Shared environmental exposures across generations in humans may result in epigenetic alterations associated with phenotypic changes, rather than a consequence of transgenerational epigenetic inheritance [206].

6. Conclusion and future directions

This review has identified early embryonic and various other stages of fetal development as susceptible periods of reprogramming leading to increased risk for adult diseases (Figure 2). Some key features that make a cell or a tissue susceptible to reprogramming have also been discussed. These include cellular differentiation, rapid cell proliferation, and meiotic events, because large-scale chromatin condensation or relaxation is usually a key feature driving these processes. The fidelity and adequacy of enzymes, precursors, co-factors, and non-coding RNAs responsible for chromatin modification, cell fate specification, and lineage commitment are critical for establishing a normal epigenome in the daughter cells. Due to the fact that these processes involve careful coordination among DNA methylation, histone modification, expression of non-coding RNAs, and other higher order chromatin sculpturing events, they are vulnerable to disruption by environmental agents. Literature pertaining to EDCs (BPA, genistein, DES, pp′-DDE, PAHs) that mimic the action of hormones, chemicals that activate morphogenic signaling (homeodomain proteins, retinoic acid, growth factors), nutritional imitators that disrupt the one-carbon cycle (folate), and activators of gene silencing RNAs (vinclozolin) were reviewed. The difference between epigenetic programming of somatic cells versus that required for germ cells has been emphasized. In this regard, the former experiences only one round of global erasure and re-establishment of epigenetic marks during differentiation from zygote-embryonic stem cells to fully differentiated cells. The latter undergo two rounds of massive epigenome re-sculpturing, one at the post-zygotic period and the second during primordial germ cell development. Since both phases occur in utero, it highlights the importance of prenatal exposure as the window of transmission of epigenetic inheritance through generations. Additional research is needed to explore toxicants capable of influencing inter- versus trans-generational transmission of epigenetic marks to fully appreciate their significance in human disease and health outcomes.

This review is by no means exhaustive, but rather seeking to address areas where major advancements have been made. Through the recognition of DOHaD as a root cause of exposure-associated reproductive dysfunctions, and the acknowledgement of epigenetics as one mediator of the process, future focus can be placed on intervention strategies to mitigate the impacts of developmental disruption by these exposures. First, the identification of reliable epigenetic biomarkers linked to an exposure-related DOHaD dysfunction enables early detection and surveillance as countermeasures. Secondly, if these biomarkers could be applied to risk assessment algorithms, new recommendations for exposure limits can be made in public health policy-making. Finally, relevant questions to be addressed in the future may include: (1) the reversibility of epigenetic marks, (2) inter- verse trans-generational inheritance, (3) exposomics or impacts of overall exposure across the life-course, (4) advanced age as a window of susceptibility, (5) resident stem cells in adult tissues as targets, and (6) the biology of regenerative medicine.

Highlights.

Epidemiological and model system studies support an early origin of reproductive dysfunction.

Estrogenic and anti-androgenic chemicals as endocrine disrupting chemicals (EDCs) have broad developmental influences on adult reproductive outcomes.

Gestational, perinatal, neonatal, and pubertal periods are “windows of susceptibility” for epigenetic programming.

EDCs induce exposure-specific epigenetic modifications in homeobox genes, nucleosome binding proteins, and cell growth-regulated genes in organs of the reproductive system.

Germline epigenetic disruption is a mechanism underlying transgenerational inheritance of reproductive disorders.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported in part by grants from the National Institutes of Environmental Health Sciences and the National Cancer Institute: RC2ES018758 (SMH), RC2ES018789 (SMH), R01CA062269 (SMH), R01ES022071 (SMH), R01ES015584 (SMH), R21ES013071 (SMH), U01ES019480 (SMH), U01ES020988 (SMH), P30ES006096 (SMH), the United States Department of Veterans Affairs I01BX000675 (SMH), R21CA156042 (NNCT), and the Department of Defense Prostate Cancer Research Program W81XWH-15-1-0496 (AC). This work was also supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health, National Institutes of Environmental Health Sciences, ZIAES102405 (CJW).

Abbreviations

- BPA

Bisphenol A

- CpG

5′-C-phosphate-G-3′

- DDT

dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane

- DEET

N,N-diethyl-meta-toluamide

- DEHP

bis(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate

- DES

Diethylstilbestrol

- DNMT

DNA methyltransferase

- DOHaD

Developmental Origins of Health and Disease

- E

Embryonic day

- EDC

Endocrine disrupting chemical

- Endo-siRNA

Endogenous small interfering RNA

- ER

Estrogen receptor

- EZH2

Enhancer of zeste 2

- F

Filial

- GD

Gestational day

- GPER1

G-protein coupled estrogen receptor 1

- HDAC

Histone deacetylase

- Hmgn5

High mobility group nucleosome biding protein 5

- HOX

Homeobox

- H3K4me3

Trimethylated histone 3 lysine 4

- H3K9ac

Acetylated histone 3 at lysine 9

- H3K9me2

Dimethylated histone 3 at lysine 9

- H3K27me3

Trimethylated histone 3 at lysine 27

- H4K5ac

Acetylated histone 4 at lysine 5

- miR/miRNA

microRNA

- NIEHS

National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences

- Nsbp1

Nucleosome binding protein 1

- PAH

Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon

- PBDE

Polybrominated dibenzoethers

- PBE

Polybrominated diphenylethers

- PCB

Polychlorinated biphenyl

- PCDF

Polychlorinated dibenzofuran

- piRNA

PIWI-interacting RNA

- PND

Postnatal day

- pp′-DDE

p,p′-dichlorodiphenyl-dichloroethylene

- SAM

S-adenosyl methionine

- Six1

Sineoculis homeobox homolog 1

- sncRNA

Small noncoding RNA

- TCDD

2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzodioxin

- TET

Ten-eleven translocation

- WNT

Wingless type MMTV integration site family

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Rosenfeld CS. Sex-Specific Placental Responses in Fetal Development. Endocrinology. 2015;156(10):3422–34. doi: 10.1210/en.2015-1227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sanchez Alvarado A, Yamanaka S. Rethinking differentiation: stem cells, regeneration and plasticity. Cell. 2014;157(1):110–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.02.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]