Abstract

Objective

The federal Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act (MHPAEA) sought to eliminate historical disparities between insurance coverage for behavioral health (BH) treatment and coverage for medical treatment. Our objective was to evaluate MHPAEA’s impact on BH expenditures and utilization among “carve-in” enrollees.

Method

We received specialty BH insurance claims and eligibility data from Optum, sampling 5,987,776 adults enrolled in self-insured plans from large employers. An interrupted time series study design with segmented regression analysis estimated monthly time trends of per-member spending and use before (2008–2009), during (2010), and after (2011–2013) MHPAEA compliance (N=179,506,951 member-month observations). Outcomes included: total, plan, patient out-of-pocket spending; outpatient utilization (assessment/diagnostic evaluation visits; medication management; individual and family psychotherapy); intermediate care utilization (structured outpatient; day treatment; residential); and inpatient utilization.

Results

MHPAEA was associated with increases in monthly per-member total spending, plan spending, assessment/diagnostic evaluation visits (respective immediate increases of: $1.05 [p=0.02]; $0.88 [p=0.04]; 0.00045 visits [p=0.00]), and individual psychotherapy visits (immediate increase of 0.00578 visits [p=0.00] and additional increases of 0.00017 visits/month [p=0.03]).

Conclusions

MHPAEA was associated with modest increases in total and plan spending and outpatient utilization; e.g., in July 2012 predicted per-enrollee plan spending was $4.92 without MHPAEA and $6.14 with MHPAEA. Efforts should focus on understanding how other barriers to BH care unaddressed by MHPAEA may affect access/utilization. Future research should evaluate effects produced by the Affordable Care Act’s inclusion of BH care as an essential health benefit and expansion of MHPAEA protections to the individual and small group markets.

Keywords: behavioral health care, health service research, policy evaluation, health insurance, claims data

Introduction

In 2014, almost a quarter of U.S. adults were estimated to have a mental illness (MI) or substance use disorder (SUD).1 However, insurance coverage for such behavioral health (BH) conditions has traditionally been less generous compared to coverage for physical illness, resulting in restricted access to,2,3 and disproportionately high patient out-of-pocket spending on,4,5 BH treatment services. The landmark 2008 federal Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act (MHPAEA) is the latest in a long line of parity laws6 attempting to rectify this disparity.

MHPAEA applied to health insurance plans sponsored by “large” employers with more than 50 employees, including both fully insured (FI) and self-insured (SI) plans. Under MHPAEA, if a plan offered BH benefits, these benefits had to be comparable to medical/surgical benefits. According to statutory provisions, key benefit features required to be “at parity” included financial requirements (e.g., deductibles, copayments) and quantitative treatment limits (“QTLs”, e.g., number of visits, days of coverage). Interim final rules (IFR) added the requirement of parity in non-quantitative treatment limits (“NQTLs”, e.g., pre-authorization, reimbursement, medical necessity review). Insurers and employers were expected to make a “good faith effort” to comply with statutory provisions (effective January 1, 2010 for plans that renew on January 1 of each year, also known as “calendar-year” plans), and were legally required to comply with the IFR7 (effective January 1, 2011 for calendar-year plans).8 Final rules (effective January 1, 2015 for calendar-year plans) clarified MHPAEA’s interaction with the Affordable Care Act (ACA).9

For SI plans, in which 63% of workers covered by employer-sponsored insurance are enrolled,10 MHPAEA was the first law to require parity in all of the aforementioned benefit features for MI, and the first law to require any benefit features be at parity for SUD. Notably, MHPAEA also required out-of-network (OON) benefits to be at parity. Barry et al. argued MHPAEA’s main contribution was the removal of treatment limitations that restricted access to BH services.11 Indeed, studies have found substantial changes to plans’ BH benefit design as a result of MHPAEA and little evidence of employers dropping BH coverage.12–14 However, little is known about the effects of MHPAEA on plan enrollees.

Thus far, three peer-reviewed studies have examined the impact of MHPAEA on members’ BH utilization and spending, but only for SUD treatment, or only among high utilizers. Busch et al. found MHPAEA was associated with a modest increase in total spending on SUD treatment, but only examined SUD-related utilization and expenditures one year before (2009) and one year after MHPAEA (2010, before all plans were legally required to comply with MHPAEA’s IFR, including NQTL parity).15 McGinty et al. found that MHPAEA was associated with increased access to, use of, and total spending on OON SUD services between 2007 and 2012, but did not consider in-network utilization or expenditures, and limited to users of SUD services, not all members.16 Grazier et al. found an association between MHPAEA and increases in outpatient mental health service use among high utilizers, but only studied data from one employer, and only considered changes between 2009 and 2010.17

The objective of our study is to investigate whether MHPAEA achieved its goals of increased access to and use of BH treatment, and lower out-of-pocket spending. We hypothesize that utilization and plan costs will increase; patient out-of-pocket costs could increase or decrease, depending on whether reductions in cost-sharing are more than offset by utilization increases. Our study complements the current literature by broadening the investigation of MHPAEA’s impact. We used an interrupted time series (ITS) study design and 6 years of data to evaluate MHPAEA’s impact on access to, use of, and spending on outpatient, intermediate, and inpatient BH treatment (MI and SUD) among adults enrolled in SI plans from large employers.

Methods

Study design and data

An individual-level ITS study design and segmented regression analysis18 were used to estimate changes in the monthly time trend of per-member expenditures and utilization during the year after the MHPAEA statute went into effect (2010, the “transition” period) and the 3 years after MHPAEA’s IFR was in effect (2011–2013, the “post-parity” period, when legal compliance was required, including parity in NQTLs), relative to the 2 years prior to implementation (2008–2009, the “pre-parity” period). Data were provided by Optum, one of the largest managed behavioral health organizations (MBHOs) in the nation. We linked: (1) specialty BH insurance claims providing spending and utilization information; (2) eligibility and demographic data; and (3) employer and plan characteristics from Optum’s Book of Business. This study was approved by University of California, Los Angeles Institutional Review Board #12-000006.

Sample

We analyzed data from adults aged 27–64 living in the 50 U.S. states enrolled in a “carve-in” plan subject to MHPAEA as of January 1, 2010 (eFigure 1). Here, we focused on “carve-in” plans (plans for which there is one contract for both BH care and medical care benefits); MHPAEA’s effects on “carve-out” plans (plans which contract directly for BH benefits, separate from any contract[s] for medical benefits) are investigated in a separate paper. We chose to stratify our analyses because MHPAEA’s impact among carve-ins may be different from its impact among carve-outs, due to historic differences in care management between the two models and due to the higher administrative burden associated with parity compliance for carve-outs (behavioral health benefits must be at parity with medical benefits from potentially multiple medical vendors). To be included in our sample, carve-in plans had to include a BH component (excluding employee assistance program and work/life -only plans), not be a retiree, supplemental or indemnity plan, not be collectively bargained, renew on a calendar-year cycle (to ensure uniform timing of MHPAEA compliance), be associated with a large employer, and be SI (excluding the very few FI plans in our data). Please see eMethods for further discussion of sampling decisions. The final sample included 179,506,951 member-months (the unit of analysis), consisting of 5,987,776 members, 6,587 plans, and 393 employers.

Measures

Outcomes included monthly enrollee use of, and spending on, outpatient, intermediate, and inpatient BH care. All outcomes are defined at the member-month level, meaning that each observation corresponds to expenditures (or utilization) by a member in a month. We defined total expenditures as the sum of plan and patient out-of-pocket spending for a given enrollee in the given month. Plan expenditures include Optum and “coordination of benefit” payments by other insurers. Patient out-of-pocket expenditures include copayment, coinsurance, and deductible spending. Expenditures were adjusted to 2013 dollars (inpatient dollars using inpatient CPI, and outpatient using “other medical professionals” CPI) and adjusted to a national mean to account for geographic variation. Outpatient utilization measures include visits for assessment/diagnostic evaluation, medication management, individual psychotherapy, and family psychotherapy. Intermediate care measures include days of structured outpatient, day treatment, and residential care. Lastly, we counted the days of inpatient care each enrollee used in the given month.

Each spending/utilization outcome was used to calculate two more measures: (1) whether an enrollee had any spending/utilization in the given month, which measured the “penetration rate” or percent of enrollees accessing care; and (2) the amount of spending/utilization if an enrollee had any spending/utilization in the given month, which measured the “conditional” amount among “users” (the subset of enrollees with positive values for the given outcome).

Covariates of interest included indicator and spline variables that measured changes in an outcome’s time trend (changes in level and slope) in the transition and post periods, relative to the pre-parity period. Indicator variables were used to measure the immediate impact of MHPAEA on an outcome (the change in level of the outcome at the start of the intervention period). Spline variables were used to measure any gradual or long-term changes MHPAEA may have had on an outcome over time (the change in slope of the outcome during the intervention period). Specifically, a continuous variable for time in months controlled for the outcome’s linear pre-parity “baseline” time trend. The indicator variable for the post period (=1 for months in 2011–2013, 0 otherwise) measured the discontinuity, or immediate change in level of the outcome, after MHPAEA’s IFR became effective in January 2011, relative to the level expected based on the pre-parity trend. The spline variable for the post period (counting months in 2011–2013, from 1 to 36) measured changes in an outcome’s slope (i.e., gradual monthly rate of change) from pre- to post-parity. The indicator/spline variables for the transition period measure respective changes in level/slope in 2010, compared to pre-parity. While we accounted for the transition period, we focused on comparisons with the post-parity period, when plans were legally required to comply with MHPAEA (including parity in NQTLs). Other covariates include sex, age group, primary insured vs. dependent status, employer size, plan type, fixed state and seasonal effects, and provider supply rates (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographics and spending/service use at the member-month level.

| Table 1a: Demographics and

employer, plan, and provider information | ||

|---|---|---|

| Total number of employers | 393 | |

| Total number of plans | 6,587 | |

| Total number of members | 5,987,776 | |

| Total number of member-months | 179,506,951 | |

|

|

||

| n | % | |

|

|

||

| Age group | ||

| 27–34 years | 35,742,653 | 19.9 |

| 35–44 | 49,634,679 | 27.7 |

| 45–54 | 52,758,152 | 29.4 |

| 55–64 | 41,371,467 | 23.0 |

| Male (vs. female) | 87,980,696 | 49.0 |

| Census Division | ||

| Northeast: New England | 7,272,335 | 4.1 |

| Northeast: Middle Atlantic | 20,034,873 | 11.2 |

| Midwest: East North Central | 28,083,675 | 15.6 |

| Midwest: West North Central | 17,624,910 | 9.8 |

| South: South Atlantic | 34,657,012 | 19.3 |

| South: East South Central | 8,603,236 | 4.8 |

| South: West South Central | 28,129,871 | 15.7 |

| West: Mountain | 17,226,012 | 9.6 |

| West: Pacific | 17,875,027 | 10.0 |

| Primary insured person (vs. dependent) | 120,533,776 | 67.2 |

| Employer group size | ||

| >40K enrolled employees | 44,609,973 | 24.9 |

| >10K & ≤40K | 75,906,647 | 42.3 |

| 5,000–10,000 | 30,849,945 | 17.2 |

| <5,000 | 28,140,386 | 15.7 |

| Plan type is EPO, POS, or HMO (vs. PPO, MIN, HDHP)1 | 163,955,965 | 91.9 |

|

|

||

| Number of providers per 1000 members, for a given state & year, by provider type: | Mean | SD |

|

|

||

| MD (doctor of medicine) | 0.8 | 0.7 |

| MSW (master of social work) | 3.1 | 3.7 |

| PHD (doctor of philosophy) | 1.1 | 1.1 |

| RN (registered nurse) | 0.2 | 0.3 |

| Non-independent licensed | 0.2 | 2.3 |

| Table 1b: Member-months with

any spending/service use, and diagnostic distribution | ||

|---|---|---|

| n | % | |

|

|

||

| Any spending/service use | 4,251,730 | 2.4 |

| Among member-months with any spending/service use: | ||

| Any adjustment disorder | 1,081,747 | 25.4 |

| Any post-traumatic stress disorder | 167,027 | 3.9 |

| Any generalized anxiety | 817,409 | 19.2 |

| Any obsessive-compulsive disorder | 80,100 | 1.9 |

| Any panic disorder | 180,569 | 4.2 |

| Any phobia | 37,360 | 0.9 |

| Any cognitive disorder | 16,386 | 0.4 |

| Any bipolar disorder | 370,660 | 8.7 |

| Any depressive disorder | 1,863,744 | 43.8 |

| Any personality disorder | 33,435 | 0.8 |

| Any psychotic disorder | 50,627 | 1.2 |

| Any alcohol use disorder | 139,158 | 3.3 |

| Any drug use disorder | 81,333 | 1.9 |

| Any other psychiatric disorder | 222,506 | 5.2 |

| Table 1c: Spending and service

use, by expenditure/utilization type | ||

|---|---|---|

| Any spending/service use | n | % |

|

|

||

| Total Expenditures | 4,246,461 | 2.37 |

| Plan Expenditures | 3,581,143 | 2.00 |

| Patient Out-Of-Pocket Expenditures | 3,849,122 | 2.14 |

| Outpatient Assessment/Diagnostic Evaluation | 502,497 | 0.28 |

| Outpatient Medication Management | 1,476,538 | 0.82 |

| Outpatient Individual Psychotherapy | 2,469,851 | 1.38 |

| Outpatient Family Psychotherapy | 195,433 | 0.11 |

| Structured Outpatient Care | 56,120 | 0.03 |

| Day Treatment Care | 21,011 | 0.01 |

| Residential Care | 12,948 | 0.01 |

| Inpatient Care | 50,030 | 0.03 |

|

|

||

| Level of spending/service use, among users | Mean | SD |

|

|

||

| Total Expenditures ($) | 345.4 | 1,453.0 |

| Plan Expenditures ($) | 300.6 | 1,449.0 |

| Patient Out-Of-Pocket Expenditures ($) | 101.6 | 252.0 |

| Outpatient Assessment/Diagnostic Evaluation (visits) | 1.3 | 1.1 |

| Outpatient Medication Management (visits) | 1.3 | 0.9 |

| Outpatient Individual Psychotherapy (visits) | 2.3 | 1.6 |

| Outpatient Family Psychotherapy (visits) | 1.8 | 1.2 |

| Structured Outpatient (days) | 6.2 | 5.5 |

| Day Treatment (days) | 6.3 | 5.9 |

| Residential (days) | 9.1 | 8.4 |

| Inpatient (days) | 5.9 | 5.1 |

Note:

“EPO”: exclusive provider organization; “POS”: point of service; “HMO”: health maintenance organization; “PPO”: preferred provider organization; “MIN”: managed indemnity; “HDHP”: high-deductible health plan.

Statistical analyses

Segmented regression analysis modeled changes in an outcome’s time trend between the pre, transition, and post periods, controlling for the aforementioned covariates. For each outcome, we modeled changes in the monthly (1) unconditional mean (mean among all enrollees) using linear regression; (2) penetration rate (probability an enrollee had any spending/use) using logistic regression; and (3) conditional mean (mean among “users”, the subset of enrollees with positive values) using gamma regression. Each model adjusted for employer-level clustering using Generalized Estimating Equations cluster robust “sandwich” standard errors, to account for employer-level sampling and the nesting of months within members within plans within employers.19,20 We used p≤0.05 as our cutoff for statistical significance.

As well as estimating changes in each outcome’s time trend, we used the above models to predict per-enrollee spending/utilization amounts, penetration rates, and peruser amounts in July 2012 under two scenarios, assuming (1) MHPAEA never happened, and (2) MHPAEA was in effect. These predictions illustrate how changes in level and slope affect an outcome’s value at the midpoint of the post-parity period. Furthermore, we tested our models and results via several sensitivity analyses; see eMethods for details.

Results

Sample characteristics

Table 1 presents demographics and unadjusted BH spending/service use for our sampled member-months in three sections: member, employer, plan, and provider characteristics (Table 1a); diagnostic characteristics (Table 1b); and spending/service use by expenditure/utilization type, providing percentages of member-months with any spending/service use (penetration rates) and average levels of spending/service use among users (Table 1c). Penetration rates illustrate that monthly BH spending/utilization was rare; e.g., 2% of member-months had any total BH expenditures, and 0.01% used residential care. In analyses not shown here, we compared sample characteristics in the pre-parity and post-parity periods, finding them stable over time.

Changes among all enrollees

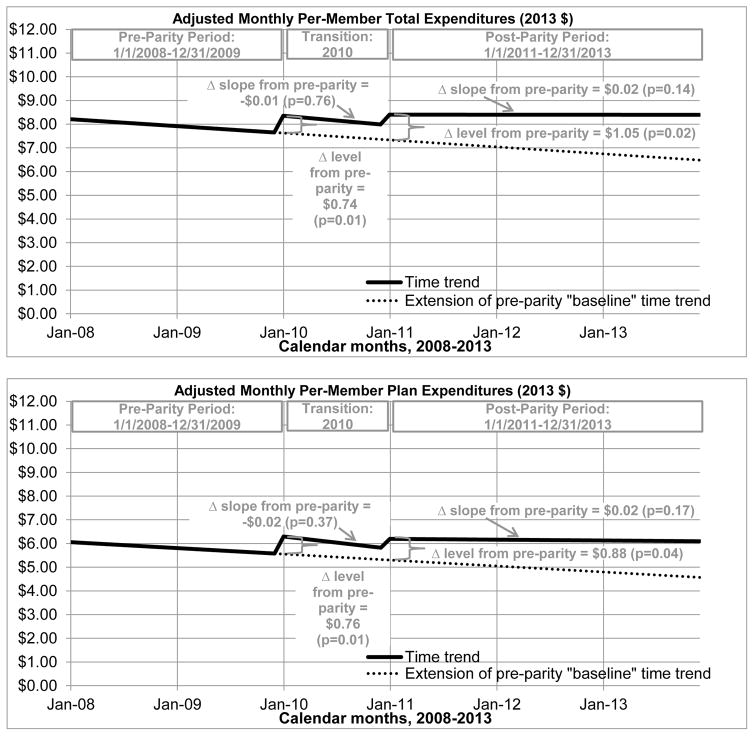

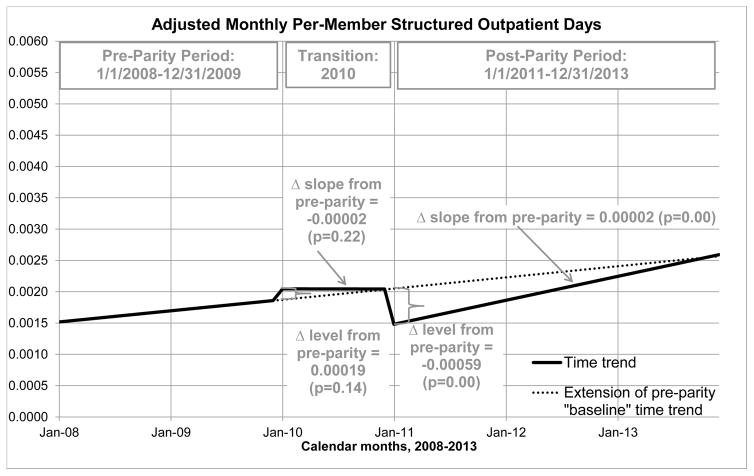

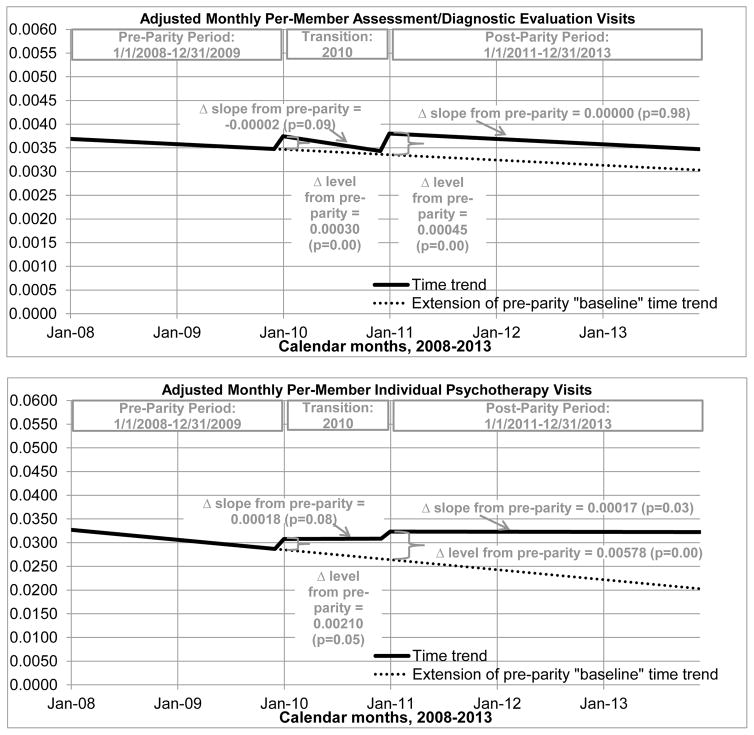

Focusing on changes in the post period when plans were legally required to comply, MHPAEA is associated with statistically significant increases in the time trends of monthly per-member total and plan spending and outpatient visits, and mixed effects for intermediate care. Figures 1–3 display significant results graphically, representing an outcome’s adjusted monthly time trend via solid black line; a dotted line projects the pre-parity “baseline” time trend forward in time, to represent what would be expected in MHPAEA’s absence. Figure 1 illustrates that, relative to what would be expected based on the pre-parity trend, monthly per-member total and plan expenditures had immediate increases of $1.05 (p=0.02) and $0.88 (p=0.04), respectively. For outpatient utilization (Figure 2), monthly per-member assessment/diagnostic evaluation had an immediate increase of 0.00045 visits (p=0.00), and monthly per-member individual psychotherapy had both an immediate increase of 0.00578 visits (p=0.00) and additional gradual increases of 0.00017 visits/month (p=0.03). In contrast, monthly per-member structured outpatient care’s changes in level and slope offset each other (Figure 3): an immediate decrease of 0.00059 days (p=0.00) was followed by gradual increases of 0.00002 days/month (p=0.00), leading to the convergence of the post-parity and pre-parity trends by the end of the study period. There were no significant changes to the time trends of monthly per-member patient expenditures, or to medication management, family psychotherapy, day treatment, residential, or inpatient utilization. A comprehensive table of estimates may be found in eTable 1.

Figure 1. Significant changes in the time trends of average monthly BH spending associated with MHPAEA, among all enrollees.

Notes: Results for patient out-of-pocket spending not shown in figure due to lack of significance. Sample is member-months from 2008–2013 (N=179,506,951). Estimates from linear regression; significance defined at p≤.05. Interrupted time series segmented regression analysis controlled for a linear monthly time trend, indicators and splines (measuring respective changes in level and slope) for the transition and post periods, sex, age group, primary insured vs. dependent, employer size, plan type, state fixed effects, provider supply, and seasonality.

Figure 3. Significant changes in the time trends of average monthly intermediate and inpatient BH utilization associated with MHPAEA, among all enrollees.

Notes: Results for day treatment, residential, and inpatient care not shown in figure due to lack of significance. Sample is member-months from 2008–2013 (N=179,506,951). Estimates from linear regression; significance defined at p .05. Interrupted time series segmented regression analysis controlled for a linear monthly time trend, indicators and splines (measuring respective changes in level and slope) for the transition and post periods, sex, age group, primary insured vs. dependent, employer size, plan type, state fixed effects, provider supply, and seasonality.

Figure 2. Significant changes in the time trends of average monthly outpatient BH utilization associated with MHPAEA, among all enrollees.

Notes: Results for medication management and family psychotherapy not shown in figure due to lack of significance. Sample is member-months from 2008–2013 (N=179,506,951). Estimates from linear regression; significance defined at p≤.05. Interrupted time series segmented regression analysis controlled for a linear monthly time trend, indicators and splines (measuring respective changes in level and slope) for the transition and post periods, sex, age group, primary insured vs. dependent, employer size, plan type, state fixed effects, provider supply, and seasonality.

Changes in penetration rates and changes among users

MHPAEA is associated with increases in the penetration rates and per-user amounts of expenditures, outpatient utilization, and inpatient utilization, but declines in these measures for intermediate care utilization. Please see eTable 2 for specific estimates, and eResults for a summary of significant effects.

Predicted spending and use, with and without MHPAEA

While the aforementioned figures describe the significant changes in an outcome’s time trend associated with MHPAEA, Table 2 summarizes parity’s effect on an outcome’s predicted value at the midpoint of the post period. For each spending and utilization outcome, per-enrollee amounts, penetration rates, and per-user amounts were predicted for July 2012, under two scenarios: (1) assuming MHPAEA never happened, and (2) assuming parity was in effect. This shows how changes in level and slope work together to affect an outcome’s value at one point in time: e.g., in July 2012 MHPAEA’s predicted effect on total per-enrollee expenditures is an increase of $1.50 per enrollee (from $6.90 to $8.40). Furthermore, Table 2 illuminates the outcomes for which overall per-enrollee increases in spending and outpatient utilization were driven by significant increases in the penetration rate (e.g., plan spending and assessment/diagnostic evaluation visits), by significant increases in spending/utilization among users (e.g., total expenditures), or by both (e.g., individual psychotherapy). Lastly, Table 2 highlights the modest magnitude of parity’s positive effects on expenditures and outpatient utilization. For example, use of outpatient individual psychotherapy increased (per-enrollee visits, penetration rate, and per-user visits), but the predicted increases in July 2012 were small (0.02 vs. 0.03; 1.2% vs. 1.4%; and 2.1 vs. 2.3, respectively). The exception is parity’s negative effect on intermediate care utilization among users; in particular, users were predicted to consume an average of 7 days of residential care in July 2012 under parity, 50% lower than the 13 days predicted without MHPAEA.

Table 2.

Predicted BH spending and utilization for the month of July 2012: per-enrollee amounts, penetration rates, and per-user amounts. Predictions are made first assuming no parity, and then assuming MHPAEA is in effect.

| Predicted Mean Among All Enrollees1 | Predicted Penetration Rate2 | Predicted Mean Among Users3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Outcome | No Parity | Parity | No Parity | Parity | No Parity | Parity |

| Expenditures | ||||||

| Total | $6.90 | $8.40* | 2.14% | 2.43% | $321.49 | $345.69* |

| Plan | $4.92 | $6.14* | 1.65% | 2.01%* | $295.89 | $305.84 |

| Patient Out-Of-Pocket | $1.98 | $2.26 | 1.95% | 2.17% | $99.52 | $103.77 |

| Outpatient Visits | ||||||

| Assessment/Diagnostic Evaluation | 0.003 | 0.004* | 0.25% | 0.28%* | 1.29 | 1.30 |

| Medication Management | 0.010 | 0.011 | 0.81% | 0.84% | 1.22 | 1.26* |

| Individual Psychotherapy | 0.023 | 0.032* | 1.16% | 1.42%* | 2.12 | 2.28* |

| Family Psychotherapy | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.12% | 0.12% | 1.75 | 1.82* |

| Days of Intermediate Care | ||||||

| Structured Outpatient | 0.002 | 0.002† | 0.04% | 0.03%‡ | 6.93 | 6.12‡ |

| Day Treatment | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.01% | 0.01% | 7.40 | 5.12‡ |

| Residential | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.01% | 0.01% | 13.49 | 6.77‡ |

| Days of Inpatient Care | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.03% | 0.03% | 5.34 | 5.94* |

Notes: Sample is member-months from 2008–2013 (N=179,506,951). Interrupted time series segmented regression analysis models controlled for a linear monthly time trend, indicators and splines (measuring respective changes in level and slope) for the transition and post periods, sex, age group, primary insured vs. dependent, employer size, plan type, state fixed effects, provider supply, and seasonality.

Predictions are from linear regression models.

Percent of enrollees with any spending (utilization). Predictions are from logistic regression models.

Mean among the subset of enrollees with any spending (utilization) for the given outcome. Sample size of “users” varies for each outcome. Predictions are from gamma regression models.

Model predicts significant positive changes in level and/or slope for the given outcome.

Model predicts significant mixed effects for level and slope for the given outcome.

Model predicts significant negative changes in level for the given outcome.

Sensitivity analyses

Our results were robust to: (1) inclusion of claims diagnoses in conditional regressions; (2) exclusion of plan type from model specification; (3) type of regression used (conditional models: gamma vs. linear; unconditional models: linear regression vs. two-part model predictions); and (4) restricting to individuals associated with employers continuously enrolled from 2008–2013 (see eTable 3 for specific effects, and eResults for a summary).

Discussion

This is the first study to investigate MHPAEA’s impact on a broad range of specialty BH service use and spending for commercially-insured adults enrolled in SI carve-in plans from large employers. We found MHPAEA was associated with increased access to and use of BH services, mainly through modest increases in outpatient BH utilization. While MHPAEA was associated with small increases in total and plan spending, there were no changes to patient out-of-pocket spending. This suggests that growth in out-of-pocket spending resulting from utilization increases may have offset any decline in out-of-pocket spending resulting from reductions in cost-sharing. Among all enrollees, there was no overall change in intermediate or inpatient care utilization by the end of the study period. However, among the subset of members who used such services, MHPAEA was associated with a small increase in inpatient use, and decreases in intermediate care use. One possible explanation for decreased intermediate care utilization among users is that because these specialized BH services (e.g., residential treatment) had no medical/surgical equivalent, employers had to choose whether to categorize intermediate care as inpatient care or as outpatient care during parity compliance. Categorization as inpatient care could have led to increased cost-sharing for intermediate care services post-MHPAEA.

Our result of increased total BH spending with no change to out-of-pocket BH spending is consistent with previous peer-reviewed evaluations of MHPAEA’s impact on SUD spending.15,16 Our finding of increased outpatient BH utilization parallels that of McGinty et al. regarding outpatient OON SUD utilization,16 and Grazier et al. regarding outpatient MI utilization.17 Our result of increased per-user inpatient BH utilization suggests a roughly similar story to that of McGinty et al., though via a different mechanism: the latter study found increases in the probability of any inpatient OON SUD service use among users of SUD services,16 and our study found increases in the number of days of inpatient treatment among users of inpatient care. To our knowledge there are no peer-reviewed studies reporting significant changes to plan spending or intermediate care use.

MHPAEA’s small impact on spending suggests that fears regarding parity substantially increasing insurers’ costs were unfounded. We found that total spending on BH services increased by $1.05 per enrollee in January 2011, a 14% increase from the predicted $7.35 total per-enrollee spending on BH services without MHPAEA. This amount is an even smaller proportion of spending for all health services: per-enrollee private health insurance expenditures were $4878 in 2011;21 prorating this number across months results in $407/month in 2011. Our result of $1.05 is roughly 0.3% of this.

We found that MHPAEA’s impact on utilization was also modest. BH utilization rates are low in general; in our data, 2% of enrollees used any BH services in a given month, with outpatient individual psychotherapy visits being the most commonly used service. With 0.027 predicted individual psychotherapy visits per enrollee in January 2011 without MHPAEA, our result of an immediate increase of 0.00578 visits per enrollee represents a 22% increase for that month.

While such modest increases in utilization and spending could be due to some plans already being at parity pre-MHPAEA, there is evidence that MHPAEA did affect the design and management of BH benefits for many plans, particularly via the removal of quantitative treatment limitations.11–14 Thus, it could be that our privately-insured population was not sick enough to see large changes in utilization. Additionally, attention should be paid to how other potential barriers to care unaddressed by MHPAEA (e.g., provider availability, stigma, lack of consumer information) are still affecting access to and use of BH treatment.22,23

Study strengths include the use of specialty BH data from Optum, one of the largest MBHOs in the U.S. Our large, nationally-representative sample includes 6 million people from 50 states. Importantly, we studied 6 years of data, allowed for lags in MHPAEA’s implementation, and analyzed three years of post-MHPAEA data, allowing us to consider how MHPAEA affected trends in BH care through 2013. In a future study, we will analyze data from 2014 to investigate interactions between MHPAEA and the ACA. Moreover, our results are consistent across many sensitivity analyses. Although we did not impose a continuous eligibility requirement, our sample has stable demographics before and after parity, and our results were similar to estimates based on the subset of individuals associated with continuously enrolled (2008–2013) employers. Thus, there is minimal evidence to suggest that MHPAEA’s estimated effects were confounded by changing demographics.

There are several study limitations. We used administrative data, which does not address quality of care, patient health status, or wellbeing. Furthermore, pre-parity, some plans limited the number of covered BH treatment days/visits, so payments for services above the limit whose claims were denied or that were not submitted to the insurer would not show up in claims databases. Post-parity, these limits were eliminated; thus, even though relatively few individuals ever reached their limits, part of the increase in utilization post-parity could have been due to our greater ability to identify service use above the caps.

Our results may not generalize to children, or to adults enrolled in carve-out plans; we are currently investigating MHPAEA’s effects on these populations in separate papers. We also did not study MHPAEA’s effect on FI plans; this is because they accounted for less than 2% of sampled plans, which is consistent with the fact that the overwhelming majority of large employers self-insure.10

ITS requires assuming that an outcome’s pre-parity time trend, when extrapolated, accurately represents the outcome’s trend in the absence of parity. Similar to McGinty et al.’s evaluation of MHPAEA’s effect on OON SUD service use16 and as explained in eMethods, we lacked a comparison group, and therefore assumed all changes in the post-parity period were due to MHPAEA. Thus, our results must be interpreted with caution. In reality, secular trends may have confounded parity’s effect, such as other changes in insurance markets and plans, the overall economy, or attitudes towards BH treatment. Nonetheless, ITS is one of the strongest quasi-experimental study designs,18 even in the absence of a comparison group.24,25 ITS is frequently used to evaluate important policy changes when no comparison group is available.26–31

While MHPAEA was a landmark piece of legislation that addressed historical inadequacies in BH insurance benefits, our study suggests MHPAEA’s effect on members’ BH use and spending was modest. BH treatment is now an essential health benefit under the ACA, which has gone beyond MHPAEA by mandating BH coverage and expanding MHPAEA protections to the individual and small group insurance markets. Because these markets tend to have less generous benefits than the large groups studied here, future research is needed to evaluate whether benefit design and corresponding service use patterns in these markets respond more vigorously to parity. In addition, efforts to remove remaining barriers to BH care unaddressed by legislation will be crucial to ensuring individuals with BH disorders receive the quality, affordable treatment they need.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge support for this study from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA, 1R01DA032619-01, PI: Ettner), and data from Optum. The academic team members analyzed all data independently and retained sole authority over all publication-related decisions throughout the course of the study. NIDA had no role in the design and conduct of the study, collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data, or preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript. We would like to thank Brent Bolstrom and Nghi Ly from Optum for the extraction, preparation and delivery of data to UCLA. Ms. Harwood wrote the manuscript and conducted the data analysis. Ettner, Azocar, Ong, Tseng, and Wells made substantial contributions to the conception or design of the study. Ettner, Azocar, Friedman, Harwood, Thalmayer, Tseng, and Xu made substantial contributions to the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data. All authors critically revised the manuscript and approved of this submission. Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed here are those of the investigators and do not necessarily reflect those of the National Institutes of Health, Optum, or UCLA. The authors certify that the manuscript represents valid work and that neither this manuscript nor one with substantially similar content under their authorship has been published or is being considered for publication elsewhere. Conflicts of interest: Dr. Azocar is an employee of Optum®, United Health Group and as such receives salary and stock options as part of her compensation. Dr. Thalmayer was a contractor for and received salary from Optum®, United Health Group.

Footnotes

All other authors declare they have no conflicts of interest.

List of supplemental digital content:

“9_CI claim20160613_V31_Supplement.docx”

“10_SuppDiagnoses20160429_V02.xls”

References

- 1.Behavioral Health Trends in the United States: Results from the 2014 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality; 2015. [Accessed December 7, 2015]. (HHS Publication No. SMA 15-4927, NSDUH Series H-50) http://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUH-FRR1-2014/NSDUH-FRR1-2014.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hodgkin D, Horgan CM, Garnick DW, Merrick EL. Benefit Limits for Behavioral Health Care in Private Health Plans. Adm Policy Ment Health Ment Health Serv Res. 2009;36(1):15–23. doi: 10.1007/s10488-008-0196-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cunningham PJ. Beyond Parity: Primary Care Physicians’ Perspectives On Access To Mental Health Care. Health Aff (Millwood) 2009;28(3):w490–w501. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.3.w490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hodgkin D, Horgan CM, Garnick DW, Merrick EL. Cost Sharing for Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services in Managed Care Plans. Med Care Res Rev. 2003;60(1):101–116. doi: 10.1177/1077558702250248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zuvekas SH, Meyerhoefer CD. Coverage for mental health treatment: do the gaps still persist? J Ment Health Policy Econ. 2006;9(3):155–163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barry CL, Huskamp HA, Goldman HH. A political history of federal mental health and addiction insurance parity. Milbank Q. 2010;88(3):404–433. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2010.00605.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. [Accessed December 7, 2015];Interim Final Rules Under the Paul Wellstone and Pete Domenici Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act of 2008. http://webapps.dol.gov/FederalRegister/HtmlDisplay.aspx?DocId=23511&AgencyId=8&DocumentType=2. [PubMed]

- 8. [Accessed December 7, 2015];Fact Sheet: The Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act of 2008 (MHPAEA) http://www.dol.gov/ebsa/newsroom/fsmhpaea.html.

- 9.Final Rules Under the Paul Wellstone and Pete Domenici Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act of 2008. [Accessed January 6, 2016];Technical Amendment to External Review for Multi-State Plan Program. http://webapps.dol.gov/FederalRegister/HtmlDisplay.aspx?DocId=27169&AgencyId=8&DocumentType=2. [PubMed]

- 10.Employer Health Benefits - 2015 Annual Survey. Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation and Health Research & Educational Trust; 2015. [Accessed December 7, 2015]. http://kff.org/report-section/ehbs-2015-summary-of-findings/ [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barry CL, Huskamp HA. Moving beyond Parity — Mental Health and Addiction Care under the ACA. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(11):973–975. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1108649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mental Health and Substance Use. Employers’ Insurance Coverage Maintained or Enhanced Since Parity Act, but Effect of Coverage on Enrollees Varied. United States Government Accountability Office; 2011. [Accessed January 15, 2016]. http://www.gao.gov/products/GAO-12-63. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Consistency of Large Employer and Group. Health Plan Benefits with Requirements of the Paul Wellstone and Pete Domenici Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act of 2008. United States Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, Office of Disability, Aging and Long-Term Care Policy; 2013. [Accessed January 15, 2016]. https://aspe.hhs.gov/report/consistency-large-employer-and-group-health-plan-benefits-requirements-paul-wellstone-and-pete-domenici-mental-health-parity-and-addiction-equity-act-2008. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Horgan CM, Hodgkin D, Stewart MT, et al. Health Plans’ Early Response to Federal Parity Legislation for Mental Health and Addiction Services. Psychiatr Serv. 2015 Sep; doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201400575. appi.ps.201400575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Busch SH, Epstein AJ, Harhay MO, et al. The effects of federal parity on substance use disorder treatment. Am J Manag Care. 2014;20(1):76–82. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McGinty EE, Busch SH, Stuart EA, et al. Federal parity law associated with increased probability of using out-of-network substance use disorder treatment services. Health Aff Proj Hope. 2015;34(8):1331–1339. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2014.1384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grazier KL, Eisenberg D, Jedele JM, Smiley ML. Effects of Mental Health Parity on High Utilizers of Services: Pre-Post Evidence From a Large, Self-Insured Employer. Psychiatr Serv. 2015 Dec; doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201400586. appi.ps.201400586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wagner AK, Soumerai SB, Zhang F, Ross-Degnan D. Segmented regression analysis of interrupted time series studies in medication use research. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2002;27(4):299–309. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2710.2002.00430.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liang KY, Zeger SL. Regression Analysis for Correlated Data. Annu Rev Public Health. 1993;14(1):43–68. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pu.14.050193.000355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cameron AC, Miller DL. A Practitioner’s Guide to Cluster-Robust Inference. J Hum Resour. 2015;50(2):317–372. doi: 10.3368/jhr.50.2.317. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.CMS. [Accessed March 3, 2016];National Health Expenditure Accounts. https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/NationalHealthExpendData/NationalHealthAccountsHistorical.html. Published December 3, 2015.

- 22.A Long Road Ahead: Achieving True Parity in Mental Health and Substance Use Care. [Accessed January 15, 2016];The National Alliance on Mental Illness. 2015 https://www.nami.org/parityreport.

- 23.Health Policy Brief: Enforcing Mental Health Parity. [Accessed December 8, 2015];Health Aff (Millwood) 2015 Nov; http://www.healthaffairs.org/healthpolicybriefs/brief.php?brief_id=147.

- 24.Fretheim A, Soumerai SB, Zhang F, Oxman AD, Ross-Degnan D. Interrupted time-series analysis yielded an effect estimate concordant with the cluster-randomized controlled trial result. J Clin Epidemiol. 2013;66(8):883–887. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2013.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lagarde M. How to do (or not to do) ... Assessing the impact of a policy change with routine longitudinal data. Health Policy Plan. 2012;27(1):76–83. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czr004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.FitzGerald JD, Mangione CM, Boscardin J, Kominski G, Hahn B, Ettner SL. Impact of changes in Medicare Home Health care reimbursement on month-to-month Home Health utilization between 1996 and 2001 for a national sample of patients undergoing orthopedic procedures. Med Care. 2006;44(9):870–878. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000220687.92922.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.FitzGerald JD, Boscardin WJ, Hahn BH, Ettner SL. Impact of the Medicare Short Stay Transfer Policy on patients undergoing major orthopedic surgery. Health Serv Res. 2007;42(1 Pt 1):25–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Aliu O, Auger KA, Sun GH, et al. The effect of pre-Affordable Care Act (ACA) Medicaid eligibility expansion in New York State on access to specialty surgical care. Med Care. 2014;52(9):790–795. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Du DT, Zhou EH, Goldsmith J, Nardinelli C, Hammad TA. Atomoxetine use during a period of FDA actions. Med Care. 2012;50(11):987–992. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31826c86f1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hacker KA, Penfold RB, Arsenault LN, Zhang F, Soumerai SB, Wissow LS. Effect of Pediatric Behavioral Health Screening and Colocated Services on Ambulatory and Inpatient Utilization. Psychiatr Serv Wash DC. 2015;66(11):1141–1148. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201400315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kozhimannil KB, Adams AS, Soumerai SB, Busch AB, Huskamp HA. New Jersey’s efforts to improve postpartum depression care did not change treatment patterns for women on medicaid. Health Aff Proj Hope. 2011;30(2):293–301. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2009.1075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.