Abstract

In prior work, we observed that soybean (Glycine max L. cv Merr.) seeds inoculated with a mutant Bradyrhizobium japonicum strain unable to catabolize Pro (Pro dehydrogenase− [ProDH−]) resulted in plants that, when forced to depend on N2 fixation as the sole source of nitrogen and subjected to mild drought stress, suffered twice as large a loss in seed yield as did plants inoculated with the parental strain. Here, we used a continuous gas flow system to measure H2 evolution as a function of time and leaf water potential (ΨL). Since one H2 is produced for every N2 fixed as an obligate part of the mechanism of N2 fixation, these measurements serve as the basis for continuous monitoring of the N2 fixation rate. In five replicate experiments, the slope of the decline in N2 fixation rate in response to water stress was always greater for plants inoculated with the mutant strain unable to catabolize Pro or take up H2 (ProDH−, hup−) than it was for plants inoculated with the parental strain (ProDH+, hup−). In aggregate, the probability that this difference occurred by chance alone was 0.005. In combination with the earlier result, this is consistent with bacteroid catabolism of Pro synthesized in response to mild drought stress having a positive impact on N2 fixation rate and seed yield.

Evidence supporting a role for Pro in protecting the N2-fixing machinery from injury during mild drought stress has been reviewed by Kohl et al. (1994) and is briefly outlined below. (1) Bacteroids in 55-d-old soybean (Glycine max L. cv Merr.) plants subjected to short-term drought stress showed a 4-fold increase in Pro concentration and a 1.6-fold increase in bacteroid Pro dehydrogenase (ProDH) activity (Kohl et al., 1991). (2) In a large greenhouse experiment (30 pots per treatment), soybean plants were forced to depend on atmospheric N2 and subjected to repeated mild drought stress. Seed yields of mature plants inoculated with a mutant Bradyrhizobium japonicum strain unable to catabolize Pro (ProDH−) decreased twice as much as did plants inoculated with the parental strain (ProDH+; Straub et al., 1997). (3) Pro supplied to greenhouse-grown soybean plants stimulated acetylene-reducing activity (the conventional method for measuring nitrogenase activity) to the same extent as did the same quantity of succinate or Glu (Zhu et al., 1992), indicating that Pro is able to supply reduced carbon to support N2 fixation as well as did succcinate or Glu. (4) Twenty-four hours after irrigation with Pro, bacteroids from Pro-treated plants had about 8 times the amount of free Pro as did plants supplied with only water (Zhu et al., 1992). This occurred despite lack of evidence of active transport of Pro across the peribacteroid membrane (PBM; Day et al., 1990; Udvardi et al., 1990; Pedersen et al., 1996) and despite an increase in bacteroid ProDH activity (Zhu et al., 1992).

These findings led us to the hypothesis that the higher seed yield of plants subjected to mild drought stress with ProDH+ versus ProDH− bacteroids was due to a differential impact on N2 fixation rate. That is, the inability to catabolize Pro might result in a steeper rate of decline of the N2 fixation rate in response to mild drought stress or in its slower recovery after rewatering.

To test this hypothesis, we measured the rate of N2 fixation continuously during imposition of drought stress imposed by withholding water. Because exposure to acetylene results in decreasing nitrogenase activity (Minchin and Witty, 1989), we chose to assess the rate of N2 fixation based on H2 evolution (Layzell et al., 1984) in plants whose seeds had been inoculated with ProDH+ and ProDH− strains of B. japonicum in a hup− background (Straub et al., 1996). It was necessary to use hup− strains because strains with uptake hydrogenase activity (hup+) can reutilize H2 produced by nitrogenase.

RESULTS

Preliminary Experiments

H2 evolution rate was measured continuously during imposition of drought and during recovery after rewatering. In order to relate N2 fixation rate to water status, the following preliminary experiments were necessary. (1) Since we wanted to determine N2 fixation rates by measuring rates of H2 evolution, and since nitrogenase can reduce both H+ and N2, it was necessary to measure the relationship between H2 evolution and N2 fixation under all of the experimental conditions to be used. (2) Because of the length of time (>24 h) required for well-watered plants to become stressed and the marked decrease of N2 fixation in the dark, it was necessary to determine whether there was an entrained diurnal effect that would influence the N2 fixation rate of plants being exposed to continuous light. (3) We were interested in the N2 fixation rate as a function of plant water status. The best measure of water status would have been to measure nodule water potential (ΨN). However, since the plants were to be monitored continuously during imposition of stress, it was not possible to measure ΨN during this period, since, in order to do this, it would have been necessary to uproot plants during the experiment. Rather, we measured leaf water potential (ΨL) and determined the relationship between ΨN and ΨL.

Relationship between H2 Evolution Rate and N2 Fixation Rate

The electron allocation coefficient (EAC) is a convenient reflection of the partitioning of electrons between protons and N2, both of which can serve as substrates for nitrogenase (Edie and Phillips, 1983; Hunt et al., 1987).

|

(1) |

where H2 produced in air is the rate of H2 production in atmosphere (21% O2:79% N2) and H2 production in Ar:O2 is the rate of H2 production in 21% O2:79% Ar. Taking into account that the reduction of N2 to NH3 requires six electrons while reduction of 2H+ to H2 requires two electrons, that the numerator is 3 times the rate of N2 production and that the denominator is 3 times the rate of N2 production plus the rate of production of H2 in air, Equation 1 can be transformed into Equation 2.

|

(2) |

The maximum value of EAC is 0.75 since of the eight e− required, only six are used to reduce N2 to two NH3. EAC values for soybean have been found to lie between 0.6 and 0.7 (Hunt and Layzell, 1993). The measurement of EAC is described in “Materials and Methods.”

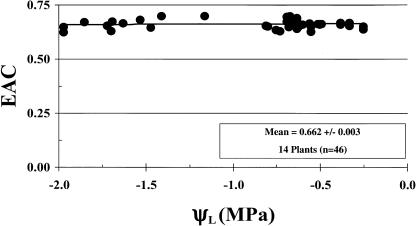

Figure 1 shows that EAC did not vary with ΨL. Therefore, H2 evolution rate is proportional to N2 fixation rate under the conditions of our experiments. This greatly simplified the experiments since determination of EAC is a time-consuming process (see “Materials and Methods”).

Figure 1.

EAC as a function of ΨL. Water was withheld from soybean plants (37 d after planting [DAP]) inoculated with ProDH+ or ProDH− B. japonicum. EAC (defined in the text) and ΨL were measured as the plants underwent dehydration. EAC is a measure of the competition for electrons between N2 and H+.

Diurnal Effect on N2 Fixation

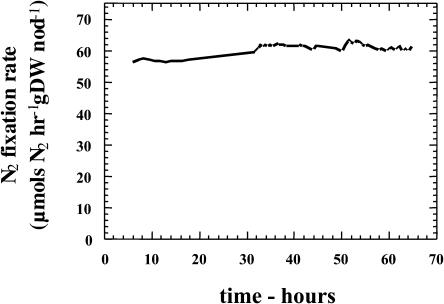

Figure 2 shows no entrained diurnal effect on N2 fixation.

Figure 2.

Effect of continuous illumination on H2 evolution by soybean root nodules. Soybean plants (36 DAP) inoculated with ProDH− B. japonicum were kept under constant illumination for 65 h. Similar results were obtained with plants inoculated with ProDH+ B. japonicum.

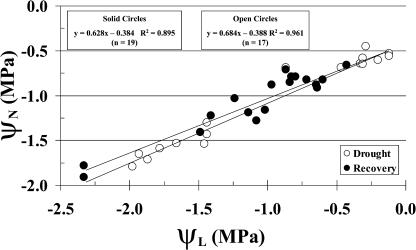

The Relationship between ΨL and ΨN

While the water status of nodules (ΨN) is the relevant parameter, we measured ΨL in order to avoid sacrificing plants during the course of the experiments. Figure 3 shows that the relationship between ΨL and ΨN is linear over the entire time during which water was withheld and as plants recovered after rewatering. Thus, ΨL can serve as a proxy for ΨN. The relationship between ΨL and ΨN is essentially the same whether plants are undergoing dehydration or recovery.

Figure 3.

Relationship between ΨL and ΨN during imposition of drought (28 DAP) and recovery after rewatering (42 DAP). Water was withheld from soybean plants inoculated with ProDH+ or ProDH− B. japonicum. Plants were harvested at different times during dehydration (white circles) and recovery after rewatering (black circles) for measurements of ΨL and ΨN.

ΨL was measured up to six times during imposition of drought. While ΨL can vary significantly from node to node, we found no significant difference in leaflets from the oldest nonsenescent node versus those from the second oldest nonsenescent node, nor from one leaflet to another at a single node (data not shown). This permitted six measurements per plant during an experiment: one leaflet from a single node three different times and one leaflet from a second node three different times.

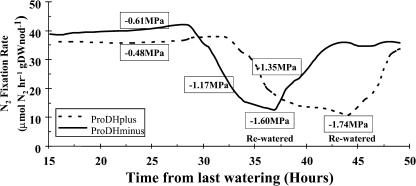

Effect of Symbiont Strain on the Relationship between ΨL and N2 Fixation Rate

Figure 4 shows the results of a typical experiment. ΨL are indicated by rectangles. The average value for well-watered plants was −0.63 ± 0.01 (n = 55). The N2 fixation rate for the well-watered control was constant over the course of the experiment (for example, see Fig. 2). In the example shown in Figure 4, N2 fixation rates began to drop 27 and 34 h after the last watering. In other experiments, the onset of the decline varied over a wide range of time since the last watering, depending on plant size, packing of support medium, etc. In the experiments that produced the data shown in Figure 4, the N2-fixing rate of the well-watered plants was about the same (36–38 μmol N2 hr−1 g dry weight nodule−1). However, in other experiments the rate varied up to 2-fold depending on plant size, density of nodules, etc. Leaves were visibly wilted when plants were rewatered (data not shown). After rewatering, plants returned to the prestress level of N2 fixation rate. Because of plant-to-plant variation in N2 fixation rate of well-watered plants, N2 fixation rates were expressed as percent of the well-watered value for the same plant. It is clear from Figure 4 that N2 fixation rate and ΨL both declined with time, as was expected, a reassuring verification that we were measuring a physiological response.

Figure 4.

A typical experiment showing N2 fixation rates over time after withholding water and during recovery after rewatering. This experiment was done 40 DAP. Results with plants inoculated with the parental strain (ProDH+) are indicated by the dashed line, and those inoculated with the ProDH− strain are indicated by the solid line. Values of ΨL at different times during the experiment are indicated in the boxes. The average value of ΨL for well-watered plants was −0.63 ± 0.01 MPa (n = 55).

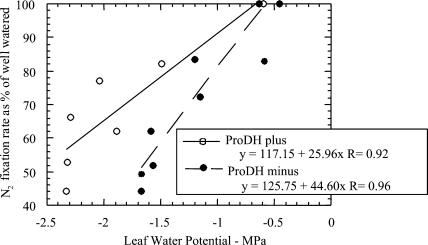

Figure 5 shows the relationship between N2 fixation rate and ΨL in the best of five experiments. This experiment was the best in the sense that the average of the correlation coefficients was higher than for experiments 2, 4, and 5, and the difference in slope between the two lines was slightly higher than in experiment 1. The slope of the decrease in N2 fixation rate of plants whose bacteroids were unable to catabolize Pro (ProDH−) was greater than it was for plants inoculated with ProDH+ B. japonicum (P = 0.03). Data for all five experiments are given in Table I below.

Figure 5.

One of five experiments showing the best relationship between ΨL and N2 fixation rate (% of well watered) during imposition of drought. Water was withheld from soybean plants (36 DAP) inoculated with ProDH+ (white circles) or ProDH− (black circles) strains of B. japonicum.

Table I.

Decline in N2 fixation rate (as percent of well-watered control) with ΨL

| Experiment No. | ProDH | Slope (N2 Fixation/ΨL) | R2 | Difference in Slope between Strains | % Difference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | + | 68.30 | 0.936 | 15.39 | 18.4% |

| − | 83.69 | 0.940 | |||

| 2 | + | 64.68 | 0.974 | 22.30 | 25.6% |

| − | 86.98 | 0.880 | |||

| 3 | + | 25.96 | 0.918 | 18.64 | 41.8% |

| − | 44.60 | 0.958 | |||

| 4 | + | 21.16 | 0.643 | 3.77 | 15.1% |

| − | 24.93 | 0.802 | |||

| 5 | + | 58.29 | 0.813 | 12.12 | 17.2% |

| − | 70.41 | 0.666 |

Mean of values in column 5 = 14.44; t value for calculating whether 14.4 > 0, t = 4.57; P = 0.005.

In five replicate experiments, the slope of the decline in N2 fixation rate as a function of ΨL of plants whose bacteroids were unable to catabolize Pro (ProDH−) was always greater than it was for ProDH+ plants. The probability of a significant difference in four of the five replicate experiments was >0.05. However, since the difference was always in the same direction, very robust statistical differences emerge (P = 0.005; Table I).

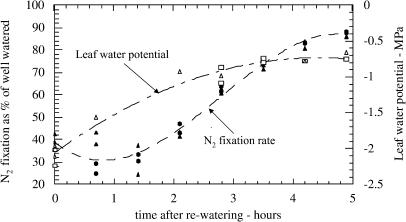

During recovery, both ΨL and N2 fixation increased (Fig. 6). However they did not increase in synchrony. N2 fixation showed a transient decrease following rewatering, possibly due to temporary water logging. By the time N2 fixation rates showed any increase over the rate at the time of rewatering (3 h after rewatering), ΨL had recovered about 65% of full turgor. This is not surprising since restoration of ΨL is a physical process, while recovery of N2 fixation is physiological. Because of the difference between ΨL and N2 fixation in timing of recovery, there is no basis for determining whether there is a difference between plants inoculated with ProDH+ or ProDH− strains in recovery of N2 fixation rate as a function of ΨL.

Figure 6.

Relationship between N2 fixation rate and ΨL versus time after rewatering drought-stressed plants. Soybean plants (42 DAP) were inoculated with either ProDH+ or ProDH− strains of B. japonicum. N2 fixation rates are indicated by black symbols (circles for ProDH+ and triangles for ProDH−), and ΨL are indicated by white symbols (squares for ProDH+ and triangles for ProDH−).

An alternative approach is to examine recovery as a function of time. However, even with curve-fitting techniques, we were sometimes unable to develop objective criteria for choosing the time at which to calculate the rate of change of N2 fixation rate, the parameter we wanted to compare for the two plant types. In the remaining, valid data set, the plant-to-plant variation within replicates exceeded the differences between the strains. Thus, our data provide evidence neither for nor against a difference in recovery rates due to strain differences.

DISCUSSION

The following are among the interesting results reported here. The efficiency of N2 fixation (EAC) did not decrease as plants became drought stressed (Fig. 1). Unlike many biological processes, the N2 fixation rate did not exhibit an entrained diurnal rhythm (Fig. 2). Despite leaves receiving their water from the xylem and nodules from the phloem, ΨL was an excellent proxy for ΨN (Fig. 3). Besides being interesting results in themselves, these results decreased the difficulty of testing the hypothesis stated in the introduction; namely, the inability to catabolize Pro might result in a steeper rate of decline of the N2 fixation rate in response to mild drought stress or in its slower recovery after rewatering. The quality of the data did not allow us to test the relative rates of recovery from mild drought stress. However, the results clearly show that the ability of bacteroids to catabolize accumulated Pro resulted in a less steep decline in N2 fixation rate when plants were subjected to mild drought stress (Table I).

It has been suggested that the Pro accumulating in response to drought stress might serve to stabilize protein structure (Schobert and Tschesche, 1978) and/or as an osmoprotectant (Kauss, 1977). We have hypothesized that the energy derived from oxidation of Pro might be useful to bacteroids. If the former were the case and those effects were the dominant manifestation of Pro accumulation, then we would expect plants inoculated with ProDH− B. japonicum to perform better than those inoculated with a ProDH+ strain. However, in our experiments, the opposite is the case. It is also possible that the enhanced respiration resulting from the catabolism of Pro might have affected the O2 diffusion barrier (Denison and Layzell, 1991), which in turn could have affected N2 fixation rate. Other indirect effects are also possible. We are unable to specify the mechanism responsible for the better performance of plants whose nodule bacteroids were able to catabolize Pro.

The results reported in this paper, together with prior results described in the introduction, support the proposition that the ability of B. japonicum bacteroids to catabolize Pro imparts benefit to the N2-fixing machinery as the plants become drought stressed. This conclusion is not in conflict with the absence of evidence for a Pro porter in the PBM. By whatever mechanism, Pro can move from the cytosol through the PBM and into bacteroids as discussed in the introduction. The rate of Pro uptake can be substantial compared with that of malate. For example, Pedersen et al. (1996) investigated the rate of uptake of malate and Pro into bacteroids within intact, peribacteroid units (symbiosomes) isolated in subambient oxygen. The rate of Pro uptake was 3 times that reported by Udvardi et al. (1990) for uptake into intact symbiosomes that were isolated in ambient oxygen. Pedersen et al. (1996) reported an approximately equal rate of uptake of malate (1 mm) versus Pro (2 mm). There may well be twice or more the amount of Pro versus malate in the cytosol of drought-stressed infected nodule cells. The photosynthetic rate (and presumably the quantity of malate in the nodules) declines sharply under drought-stressed conditions, while the amount of nodule Pro increases sharply (4-fold; Kohl et al., 1991).

While the importation of tricarboxylic acids from the host to the bacteroids provides the main reduced carbon source supporting N2 fixation when photosynthesis is vigorous, under conditions of water stress, photosynthate supplies decrease. In that circumstance, an alternative reduced carbon source might be useful to bacteroids, as discussed above. Pedersen et al. (1996) showed that nitrogenase activity supported by Pro was 8-fold higher in bacteroids from drought-stressed nodules than in bacteroids from control nodules, while there was no significant response to drought stress in the rate of nitrogenase activity supported by malate.

Soybeans growing in the United States Midwest suffer mild drought stress on most days during the growing season. By 2 pm these leaves are often visibly wilted. Since the catabolism of stress-induced Pro appears to provide some benefit to the N2-fixing machinery, it would be interesting to be able to direct more Pro into bacteroids. Engineering a Pro porter into the PBM and/or overexpressing it there might accomplish this. The sequences for a PBM-specific targeting transporter (Delauney et al., 1990) and for an Escherichia coli Pro porter (Culham et al., 1992) are known. This information should make it possible to accomplish this goal.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial Inoculant and Plant Material

Two strains of Bradyrhizobium japonicum were used in the study. JH47 (JH[hup::Tn5] KMr into hup locus) was able to catabolize Pro. KL1 (JH47[putA::Ω] Spr gene cassette into putA locus) was made from this parent (Straub et al., 1996). KL1 was unable to catabolize Pro. Neither had a functioning H2 uptake system (hup−). Strains were grown in yeast extract/mannitol (Dalton, 1980) medium in the presence of the appropriate antibiotics (100 μg/mL rifampicin and 100 μg/mL kanamycin for both strains and, in addition, 100 μg/mL of spectinomycin for KL1). Cultures were immobilized on peat (materials and protocol were provided by John Koshank, Liphatech, Nitragin Division, Milwaukee, WI).

Soybean (Glycine max L. cv Merr.) seeds (Williams 82) were inoculated with either JH47 or KL1. Five seeds per pot were planted in Hi Dry (Sud Chemie Absorbents, Munich), a calcined clay containing less than 0.06 mg N g−1, and able to hold 60% of its dry weight as water (data not shown). The pots were fabricated from 6-inch PVC pipe. Pots were 6 inches tall with a drainage tube near the bottom of the pot, which served as well for gas flow. After germination, plants were thinned to one per pot. Supplemental illumination (800 photons m−2 s−1 as measured with a LI-COR model LI1858 detector [Lincoln, NE], Quantum Q at plant height) was provided. Plants were fertilized with a nitrogen-free mineral medium (Fishbeck et al., 1973). One week prior to the start of each experiment, plants were moved to the growth chamber (CMP 3244; Conviron, Winnipeg, Canada) used for gas exchange measurements.

Determination of the Rate of N2 Fixation

All of the experiments reported here depend upon measurements of the H2 evolved by nodules infected with hup− strains of B. japonicum, either with or without the ability to catabolize Pro. The N2 fixation rate was calculated from the rate of H2 evolution (Layzell et al., 1984) as given in Equations 1 and 2 in “Results.”

N2 fixation rate is a function of H2 fixation rate and EAC (Eq. 2). H2 evolution rate was measured as described below. EAC was calculated based on Equation 1 in “Results.”

When measuring H2 evolution rate in Ar:O2 as required by Equation 1, care was taken to limit exposure to Ar to the briefest time necessary to make the measurement (6 mins), since nitrogenase activity is inhibited by Ar and to wait until H2 evolution rates had returned to their pre-Ar exposure levels (approximately 6 h) before using H2 evolution rate data.

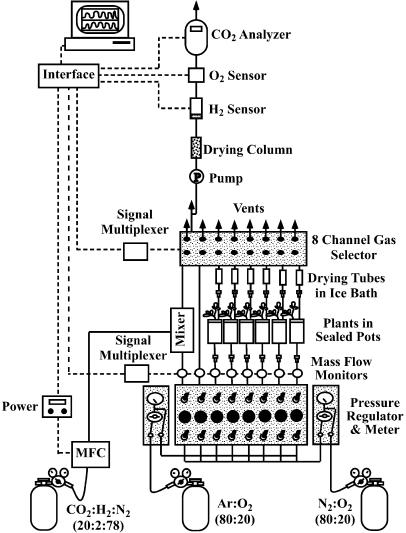

Measurement of H2 was done in a gas flow system similar to that described by Layzell et al. (1989). The system was fabricated by Qubit Systems, Kingston, Ontario. A diagram of the system is shown in Figure 7. It has eight ports accommodating six plants, the other two ports being used for reference gas (air) and for calibration. It includes an O2 sensor in order to make sure that the O2 concentration in the N2:O2 gas mixture was the same as that of the Ar:O2 mixture, since (1) nitrogenase activity is dependent on O2 concentration and (2) the output of the H2 detector is dependent on the composition of the gas mixture. The system also includes an infrared CO2 analyzer, which allows determination of the effect of stress on root respiration and nodule conductance. The H2 and CO2 analyzers were calibrated with gasses of known composition and concentrations. Several concentrations of H2 with both air and Ar:O2 are required since the output of the detector depends on the gas composition.

Figure 7.

Cartoon of gas flow system used for this work, including gases for measuring H2 evolution as well as for EAC determinations.

Preparation of Plants for Gas Exchange Measurements

One week prior to the start of each experiment, plants were moved to a growth chamber used for gas exchange measurements held at a constant temperature (22°C). The sharp decrease in N2 fixation during dark periods (data not shown) complicated interpretation of the decrease due to drought, since experiments typically lasted about 72 h. For this reason, we acclimatized the plants in 24 h of light (300 photons m−2 s−1 at plant height). Preliminary experiments established that there was no entrained diurnal effect on N2 fixation, as discussed above (Fig. 2). Before starting the experiment, lids equipped with an opening for the stem and a port for watering and for gas outflow were sealed around the plants with Qubitac Sealant (Qubit Systems). Air was pumped through the pots from the bottom at the rate of 1 L min−1. Gas coming out of the top of the pot was dehydrated, a crucial step, since the output of the H2 detector varies with relative humidity. The rate of H2 evolution from each plant was measured 6 min before cycling to the next port. The system can accommodate up to six plants (Fig. 7). Initially, we used four ports of the system for two drought-stressed plants inoculated with the ProDH+ and ProDH− strains and two ports for well-watered controls. Once it was established that the N2 fixation rate of the well-watered controls was constant, three plants inoculated with the ProDH+ strain and three plants inoculated with the ProDH− strain were connected to the six ports. After a stable H2 evolution was established in well-watered plants, drought was imposed by withholding water.

Estimation of the Degree of Water Stress

ΨL and ΨN were measured by dew point psychrometry (HR 33Y Dew point microvolt meter with thermocouple psychrometers; Wescor, Logan, UT). Preliminary experiments showed a very high correlation between ΨL and ΨN (Fig. 3). Therefore, ΨL was used as a proxy for water status of the nodule. ΨN measurements would have required uprooting the plant, making it impossible to make measurements of H2 evolution over the course of the experiment. ΨL was measured on one leaflet from the lowest two nonsenescent nodes. Since there were no significant differences between ΨL for the three leaflets on either node or for the average between the two nodes, we made up to six measurements of ΨL per plant during an experiment.

Acknowledgments

We thank Steve Hunt (Qubit Systems) for valuable discussions.

This work was supported by the Washington University-Monsanto Company Biology Research Program.

Article, publication date, and citation information can be found at www.plantphysiol.org/cgi/doi/10.1104/pp.104.044024.

References

- Culham DE, Lashby B, Marangon AG, Milner JL, Steer BA, van Ness RW, Wood JM (1992) Isolation and sequencing of Escherichia coli gene proP reveals unusual structural features of the osmoregulatory proline/betaine transporter ProP. J Mol Biol 229: 268–276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalton H (1980) The cultivation of diazotrophic microorganisms. In F Bergersen, ed, Methods for Evaluating Biological Nitrogen Fixation. John Wiley & Sons, New York, pp 13–64

- Day DA, Ou-Yang LJ, Udvardi MK (1990) Nutrient exchange across the peribacteroid membrane of isolated symbiosomes. In P Gresshoff, E Roth, G Stacey, W Newton, eds, Nitrogen Fixation: Achievements and Objectives. Chapman & Hall, New York, pp 219–226

- Delauney AJ, Cheon C-I, Verma DPS (1990) A nodule-specific sequence encoding a methionine-rich polypeptide, nodulin-21. Plant Mol Biol 14: 449–451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denison RF, Layzell DB (1991) Measurement of legume nodule respiration and O2 permeability by noninvasive spectrophotometry of leghemoglobin. Plant Physiol 72: 156–160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edie SA, Phillips DA (1983) Effect of the host legume on acetylene reduction and hydrogen evolution by Rhizobium nitrogenase. Plant Physiol 72: 156–160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fishbeck K, Evans HJ, Boersma LL (1973) Measurement of nitrogenase activity in intact legume symbionts in situ using the acetylene reduction assay. Agron J 65: 429–433 [Google Scholar]

- Hunt S, King BJ, Canvin DT, Layzell DB (1987) Steady and nonsteady state gas exchange characteristics of soybean nodules in relation to the oxygen diffusion barrier. Plant Physiol 84: 164–172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt S, Layzell DA (1993) Gas exchange of legume nodules and the regulation of nitrogenase activity. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol 44: 483–511 [Google Scholar]

- Kauss H (1977). Biochemistry of osmotic regulation. In DH Northcote, ed, International Review of Biochemistry: Plant Biochemistry II, Vol 13. University Park Press, Baltimore, pp 119–139

- Kohl DH, Kennelly EJ, Zhu Y-X, Schubert KR, Shearer G (1991) Proline accumulation, nitrogenase (C2H2 reducing) activity, and activities of enzymes related to proline metabolism in drought-stressed soybean nodules. J Exp Bot 42: 831–837 [Google Scholar]

- Kohl DH, Straub PF, Shearer G (1994) Does proline play a special role in bacteroid metabolism? Plant Cell Environ 17: 1257–1262 [Google Scholar]

- Layzell DB, Hunt S, King BJ, Walsh KB, Weagle GE (1989) A multichannel system for steady-state and continuous measurements of gas exchanges from legume roots and nodules. In J Torrey, L Winship, eds, Applications of Continuous and Steady-State Methods to Root Biology. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, The Netherlands, pp 1–28

- Layzell DB, Weagle G, Canvin DT (1984) A flow-through H2 gas analyzer for use in nitrogen fixation studies. Plant Physiol 75: 582–585 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minchin FW, Witty JF (1989) Limitations and errors in gas exchange measurements with legume nodules. In J Torrey, L Winship, eds, Applications of Continuous and Steady-State Methods to Root Biology. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, The Netherlands, pp 79–95

- Pedersen AL, Feldner HC, Rosendahl L (1996) Effect of proline on nitrogenase activity in symbiosomes from root nodules of soybean (Glycine max L.) subjected to drought stress. J Exp Bot 47: 1533–1539 [Google Scholar]

- Schobert B, Tschesche H (1978) Unusual properties of proline and its interaction with proteins. Biochim Biophys Acta 541: 270–277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straub PF, Reynolds PHS, Althomsons S, Mett V, Zhu Y-x, Shearer G, Kohl DH (1996) Isolation, DNA sequence analysis, and mutagenesis of a proline dehydrogenase gene (putA) from Bradyrhizobium japonicum. J Appl Exp Microbiol 62: 221–229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straub PF, Shearer G, Reynolds PHS, Sawyer SA, Kohl DH (1997) Effect of disabling bacteroid proline catabolism on the response of soybeans to repeated drought stress. J Exp Bot 48: 1299–1307 [Google Scholar]

- Udvardi MK, Ou-Yang LJ, Young S, Day DA (1990) Sugar and amino acid transport across symbiotic membranes from soybean nodules. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 3: 334–340 [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Y-X, Shearer G, Kohl DH (1992) Proline fed to intact soybean plants influences acetylene reducing activity, and proline content and metabolism in bacteroids. Plant Physiol 98: 1020–1028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]