Abstract

Oxidative stress is a toxicological endpoint that correlates with the nutrition status of fish through cellular damage, inflammation, and apoptosis. In order to understand the antioxidant mechanism induced by dietary emodin in Megalobrama amblycephala liver, a comparative proteomic analysis was performed to investigate the proteome alteration under emodin administration. 27 altered protein spots were separated under 30 mg kg−1 emodin stimulation based on 2-DE, and were all successfully identified using MALDI-TOF/TOF, representing 17 unique proteins. These proteins were functionally classified into antioxidant, metabolism, cytoskeleton, chaperone, signal transduction and cofactor groups. Network interaction and Gene Ontology annotation indicated 10 unique proteins were closely related to antioxidation and directly regulated by each other. Compared with the control group, administration of 30 mg kg−1 emodin significantly increased the antioxidant-related mRNA expressions of GPx1, GSTm and HSP70, but decreased the mRNA expressions of GAPDH and Sord, which was consistent with the protein expression. Nevertheless, Pgk1 and Aldh8a1 were up- and down-regulated, and ALDOB was down- and up-regulated at the mRNA and protein levels, respectively. These results revealed that the altered proteins enhanced antioxidation via complex regulatory mechanisms, and 30 mg kg−1 emodin was a suitable immunostimulant for M. amblycephala.

Fish health and growth depend on a stable internal environment of the body, including a balanced antioxidant defence system. Immunostimulant is an effective nutritional feed additive that typically affects antioxidant and immunity mechanisms1, which provide protection against a wide range of adverse stresses. Purivirojkul2 reported that 0.18 g kg−1 dietary peptidoglycan significantly enhanced the superoxide anion, phenoloxidase, and bactericidal activity in shrimp. Other research documented that oral administration of vitamin C and Chinese herbs effectively improved immune activity and vibriosis resistance capability in the shrimp Litopenaeus vennamei3. In addition, studies have confirmed that dietary folic acid, probiotics and chitosan can increase the antioxidant activity of M. amblycephala4, gilthead seabream5 and Nile tilapia6, respectively. Emodin is an active anthraquinone that is extracted from the rhizomes of rhubarb (Rheum officinale Bail)7. In mammals, functional research investigating emodin has typically focused on its antitumor, anti-bacterial, anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, liver protective, and immune regulatory capabilities8,9,10. Previous studies have shown that dietary emodin can improve growth11, enhance immunity12, and provide antioxidant properties13 in M. amblycephala.

Oxidative stress results from an imbalance between pro-oxidants and anti-oxidant defense systems. Pro-oxidants include reactive oxygen species (ROS) that primarily arise as by-products of normal metabolic activities14 and have been reported to be involved in the toxicity of several xenobiotics15,16. If not scavenged properly, pro-oxidants may cause oxidative damage to proteins, nucleic acids and other macromolecules17. Under pro-oxidant conditions, there is a need for a cellular defense system to maintain normal metabolism18. Therefore, enhancement of antioxidant activity through nutrition is of much interest in intensive aquaculture strategies.

Proteins play an essential role in a variety of cellular functions, and oxidative damage can reduce the function of critical proteins19; traditional physiological and biochemical methods cannot determine the molecular mechanisms underlying this phenomenon. Proteomic approaches are being increasingly applied in aquaculture on the premise that the identification of specific changes in protein expression in response to a particular challenge can elucidate the underlying molecular pathways20,21,22. More recently, nutritional omics has also become a research focus aiming at understanding how diet influences gene transcription, protein expression and metabolite synthesis23. In reviews, Kussmann24,25 considered the application of proteomics in nutritional research to contribute to the identification of bioactive food components, assess their biological efficacy, and to elucidate biomarkers for defining the susceptibility of an individual to diet in nutritional interventions.

M. amblycephala is one of the most widely cultivated freshwater fish species in China, and has also been introduced to America, Africa and Euro-Asia. M. amblycephala has great consumer demand in China, and its production reached 0.73 million tons in 201426. Nevertheless, in an intensive culture system, cultivated M. amblycephala has suffered adverse stressors from their living surroundings, such as overcrowding, high temperature, poor water quality, and pathogen infection. All these adverse stressors could lead to poor growth performance12, disease outbreak27 and even massive mortalities28,29. Therefore, to alleviate the effects of these stressors should be an important goal of aquaculture research.

As one of the most important defensive tissues, liver combats oxidative stress caused by excessive ROS and plays an important role in the metabolism of different nutrients and toxins30. Recently, we found that 30 mg kg−1 emodin was the optimum level of dietary supplementation to enhance the growth performance, non-specific immunity, and disease resistance to Aeromonas hydrophila12 (shown in Supplementary Material 1). Although research has shown that emodin affects both immunity and antioxidation, the underling molecular mechanisms are still not entirely understood. Thus, the 30 mg kg−1 group was selected to examine the altered antioxidant-related proteins of livers of M. amblycephala fed with dietary emodin using proteomic approaches. Furthermore, identification and expression analysis of these proteins at mRNA and protein levels elucidated the antioxidant molecular mechanism associated with emodin. To our knowledge, this is the first documented application of a proteomic approach in M. amblycephala research stimulated with dietary emodin. Our results provide new insights into the anti-oxidative responses and molecular mechanisms underlying the protective effect of emodin on M. amblycephala.

Results

2-DE and classification of altered proteins

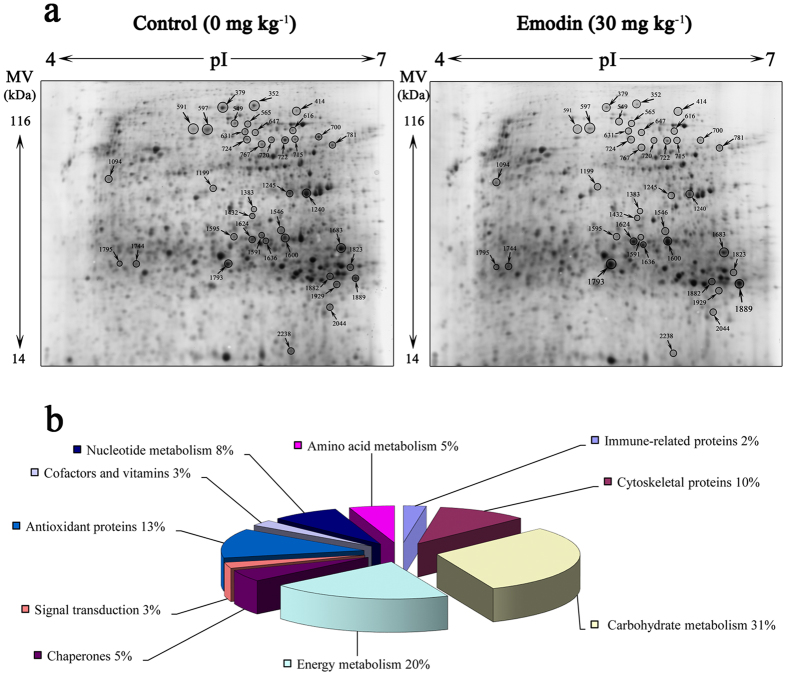

Figure 1a shows the 2-DE maps for the control and 30 mg kg−1 emodin groups after an 8-week feeding trial. A total of 27 significantly altered protein spots between the control and emodin groups (up/down-regulated ≥2 fold) were detected, including 6 up-regulated and 21 down-regulated spots. Eventually, all protein spots were identified and were found to represent 17 unique proteins (shown in Table 1). The MALDI-TOF analysis results were shown with Target No. of altered proteins in Supplementary Material 2. The peptides for MS/MS identification were shown in Supplementary Material 3.

Figure 1. The 2-DE reference maps and functional classification of altered proteins derived from the hepatic cells of the control and 30 mg kg−1 emodin groups (pI 4-7).

(a) Significantly increased or decreased proteins are denoted by a circle, arrow and spot number. Molecular masses of marker proteins and pI are mentioned on the left side and at the top, respectively. (b) The identified M. amblycephala liver proteins were classified based on their GO annotations for biological processes and molecular functions.

Table 1. Altered proteins in hepatic cells from the 30 mg kg−1 versus the control emodin group detected by 2-DE and TOF-MS/MS.

| Spot No. | Target No. | Protein name | Species | Accession No. | Abbr. | T-test P-value | Fold change |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cytoskeleton proteins | |||||||

| 597 | C6 | keratin 18 | Danio rerio | gi|29335504 | Krt18 | 0.049 | −3.71 |

| 591 | C7 | keratin, type I cytoskeletal 18 | Danio rerio | gi|30410758 | Krt18 | 0.002 | −2.28 |

| 1094 | C9 | keratin-like protein | Ctenopharyngodon idella | gi|226510657 | Krt8 | 0.017 | 3.50 |

| 616 | D4 | keratin 18 | Danio rerio | gi|29335504 | Krt18 | 0.002 | −3.13 |

| Carbohydrate metabolism | |||||||

| 549 | C18 | malic enzyme 1, NADP(+)-dependent, cytosolic | Xenopus tropicalis | gi|187608085 | ME1 | 0.039 | −4.87 |

| 631 | C21 | aldehyde dehydrogenase family 8 member A1 | Danio rerio | gi|52218932 | Aldh8a1 | 0.001 | −3.70 |

| 647 | C22 | beta-enolase | Danio rerio | gi|47551317 | Eno3 | 3.252e–4 | −3.85 |

| 722 | D6 | Eno3 protein | Danio rerio | gi|77567762 | Eno3 | 0.003 | −2.47 |

| 715 | D7 | beta-enolase | Danio rerio | gi|47551317 | Eno3 | 0.011 | −4.99 |

| 724 | C23 | Eno3 protein | Danio rerio | gi|77567762 | Eno3 | 1.833e–4 | −2.30 |

| 720 | D1 | beta-enolase | Danio rerio | gi|47551317 | Eno3 | 0.001 | −2.06 |

| 781 | D9 | phosphoglycerate kinase 1 | Danio rerio | gi|41388972 | Pgk1 | 0.001 | −3.37 |

| 2044 | E3 | L-lactate dehydrogenase B-B chain | Danio rerio | gi|50540008 | LDHBB | 0.010 | −2.95 |

| 1432 | F19 | Sorbitol dehydrogenase | Salmo salar | gi|213514212 | Sord | 7.320e–5 | −18.68 |

| Energy metabolism | |||||||

| 1823 | F1 | glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase | Gobiocypris rarus | gi|298201228 | GAPDH | 0.001 | −4.35 |

| 1546 | F4 | fructose-bisphosphate aldolase B | Oryzias latipes | gi|46849373 | ALDOB | 0.025 | −5.06 |

| 1600 | F5 | fructose 1,6-bisphosphate aldolase B | Cynoscion | gi|77380115 | ALDOB | 0.004 | 2.83 |

| 1245 | F21 | PREDICTED: fructose-bisphosphate aldolase B-like | Oncorhynchus mykiss | gi|348514442 | ALDOB | 0.022 | −4.95 |

| 1240 | F23 | PREDICTED: fructose-bisphosphate aldolase B-like | Oncorhynchus mykiss | gi|348514442 | ALDOB | 0.001 | −2.19 |

| Chaperone | |||||||

| 1636 | F9 | HSP70 protein | Poecilia reticulata | gi|157679184 | HSP70 | 0.005 | 4.87 |

| Signal transduction | |||||||

| 1793 | E15 | apolipoprotein A-I | M. amblycephala | gi|319429949 | ApoA1 | 0.008 | 3.64 |

| Antioxidant proteins | |||||||

| 1795 | E11 | glutathione S-transferase mu | Cyprinus carpio | gi|112901117 | GSTm | 0.039 | 5.86 |

| 1889 | E24 | glutathione peroxidase 1 | Danio rerio | gi|169403976 | GPx1 | 0.006 | 4.29 |

| Cofactors and vitamins | |||||||

| 700 | D8 | betaine--homocysteine S-methyltransferase 1 | Danio rerio | gi|60279651 | Bhmt1 | 0.003 | −2.40 |

| Amino acid metabolism | |||||||

| 1199 | C17 | aspartate aminotransferase, cytoplasmic | Danio rerio | gi|47085773 | AST | 1.860e–5 | −3.58 |

| Nucleotide metabolism | |||||||

| 1591 | F8 | eukaryotic translation elongation factor 2b | Danio rerio | gi|41386743 | EEF2b | 6.77e–4 | −2.81 |

| 1595 | G10 | eukaryotic translation elongation factor 2b | Danio rerio | gi|41386743 | EEF2b | 7.19e–4 | −4.53 |

Liver proteins were differentially expressed in the 30 mg kg−1 versus the control emodin groups as described in the Methods section and identified by 2-DE and MS/MS, with relative expression ratios.

The identified M. amblycephala liver proteins could be classified into 9 categories based on their GO annotations for biological processes and molecular functions (shown in Table 1 and Fig. 1b). Approximately 38% of the identified protein spots (10 spots containing 6 unique proteins) were functionally determined to participate in carbohydrate metabolism, representing the most abundant category in this study. Proteins related to energy metabolism (19% of the spots, 5 spots, 2 unique proteins) came the second in terms of the amount. Another large set of identified proteins belonged to the cytoskeletal category (15% of the spots, 4 spots, 2 unique proteins). Other categories associated with the identified proteins included antioxidant proteins (7% of the spots, 2 spots, 2 unique proteins), nucleotide metabolism (7% of the spots, 2 spots, 1 unique protein), chaperones (4% of the spots, 1 spot), amino acid metabolism (4% of the spots, 1 spot), cofactors and vitamins (4% of the spots, 1 spot), and signal transduction (4% of the spots, 1 spot). Proteins related to carbohydrate and energy metabolism were predominant and accounted for approximately 57% of the altered proteins.

Network analysis and functional annotation of altered proteins

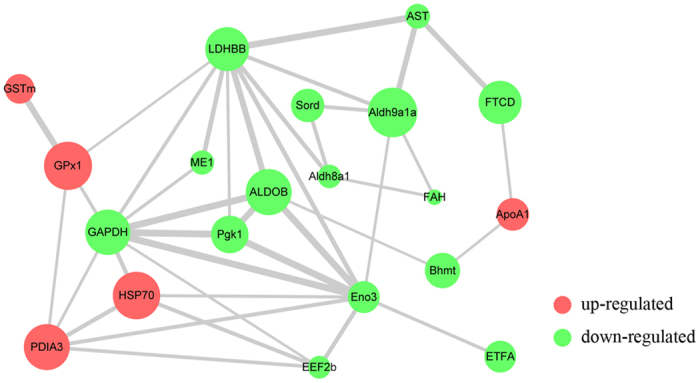

To further explore the potential antioxidant-related proteins in M. amblycephala, network interaction and functional annotation analysis were performed. The interaction network was constructed using Cytoscape based on the protein expression database, and the interaction and intensity retrieved from NCBI and STRING. The results indicated that 15 unique proteins had important roles in the interaction network (shown in Fig. 2).

Figure 2. Network interaction of altered proteins identified in the 30 mg kg−1 emodin group.

In the network, each node represents a protein; nodes in red and green color represent up- and down-regulated proteins, respectively. The size of a node represents an average of the protein abundance. The width of a line connecting proteins represents the intensity of the protein interaction, as extracted from STRING database.

Concomitantly, the annotation results indicated that 10 proteins were functionally involved in antioxidant processes, including fructose-bisphosphate aldolase B (ALDOB), glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH), glutathione peroxidase 1 (GPx1), glutathione S-transferase mu (GSTm), heat shock 70 kDa protein (HSP70), malic enzyme 1 (ME1), L-lactate dehydrogenase B-B (LDHBB), phosphoglycerate kinase 1 (Pgk1), aldehyde dehydrogenase family 8 member A1 (Aldh8a1) and sorbitol dehydrogenase (Sord). According to the interaction network, these 10 antioxidant-related proteins were directly regulated by each other, and 5 of them (ALDOB, GAPDH, GPx1, GSTm, and HSP70) were up-regulated while the other 5 (Aldh8a1, Sord, ME1, LDHBB, and Pgk1) were down-regulated at the protein level. Among the antioxidant-related proteins, ALDOB and GAPDH were functionally annotated to energy metabolism, GPx1 and GSTm were annotated to antioxidants, HSP70 was chaperones, and the remaining 6 proteins (ME1, LDHBB, Pgk1, Aldh8a1, Eno3 and Sord) played a role in carbohydrate metabolism. Considered together, these results suggested that the 10 uniquely expressed proteins could be related to the enhancement of the antioxidant reaction in M. amblycephala hepatic cells.

Besides, altered proteins of keratin 8 (krt8, up-regulated) and keratin 18 (krt18, down-regulated) were not involved in the network interaction. The other 5 proteins of eukaryotic translation elongation factor 2b (EEF2b), beta-enolase (Eno3), betaine-homocysteine S-methyltransferase 1 (Bhmt) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) were down-regulated, whereas apolipoprotein A-I (ApoA1) was up-regulated since it was involved in network interaction but not directly related to antioxidation.

RT-PCR analysis of altered proteins

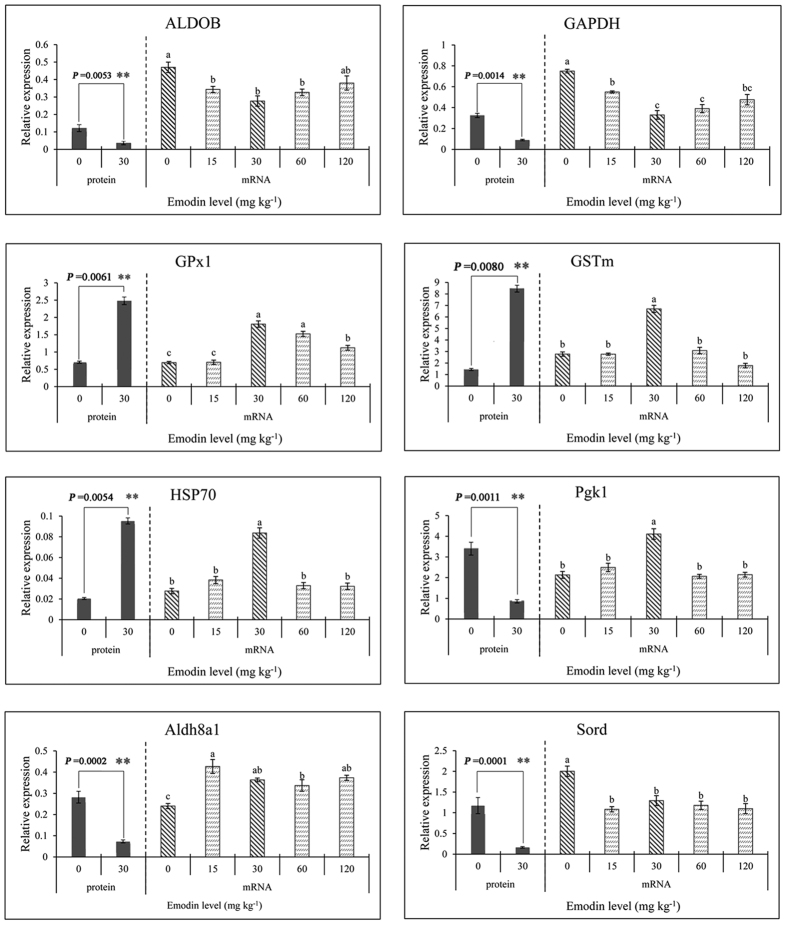

Among the identified proteins, 8 key proteins out of 10 involved in antioxidation were selected for further expression pattern analysis at the transcript level. The RT-PCR results (shown in Fig. 3) indicated that 30 mg kg−1 emodin significantly improved the mRNA expression of GPx1, GSTm, HSP70, Pgk1 and Aldh8a1 compared with the control group (P < 0.05). In contrast, the mRNA expressions of ALDOB, GAPDH, and Sord were significantly decreased (P < 0.05) during dietary emodin stimulation. In addition, the mRNA expressions of GPx1, GSTm, HSP70 and Pgk1 first increased and then decreased with the increasing of dietary emodin levels, with the highest expression being observed in the 30 mg kg−1 group (P < 0.05); ALDOB and GAPDH showed a reverse pattern, exhibiting the lowest expression in the 30 mg kg−1 group (P < 0.05).

Figure 3. Relative expression of antioxidant-related proteins at protein and mRNA levels.

Diverse little letters above histogram bars show significant differences (P < 0.05) in different dosage groups in Duncan’s multiple range tests. Significant differences (P < 0.05 or P < 0.01) between values obtained the control 30 mg kg−1 emodin group were marked by asterisks above histogram bars in Independent-Samples t-tests.

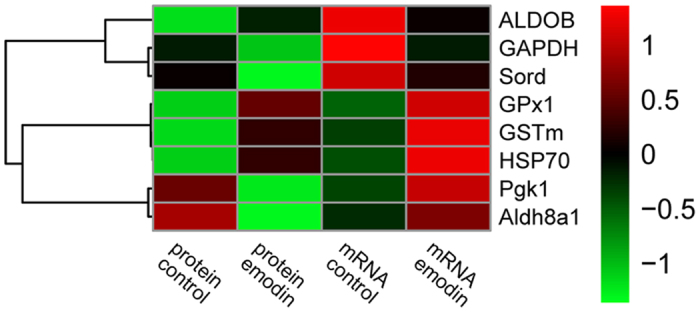

Expression analysis at the mRNA and protein levels

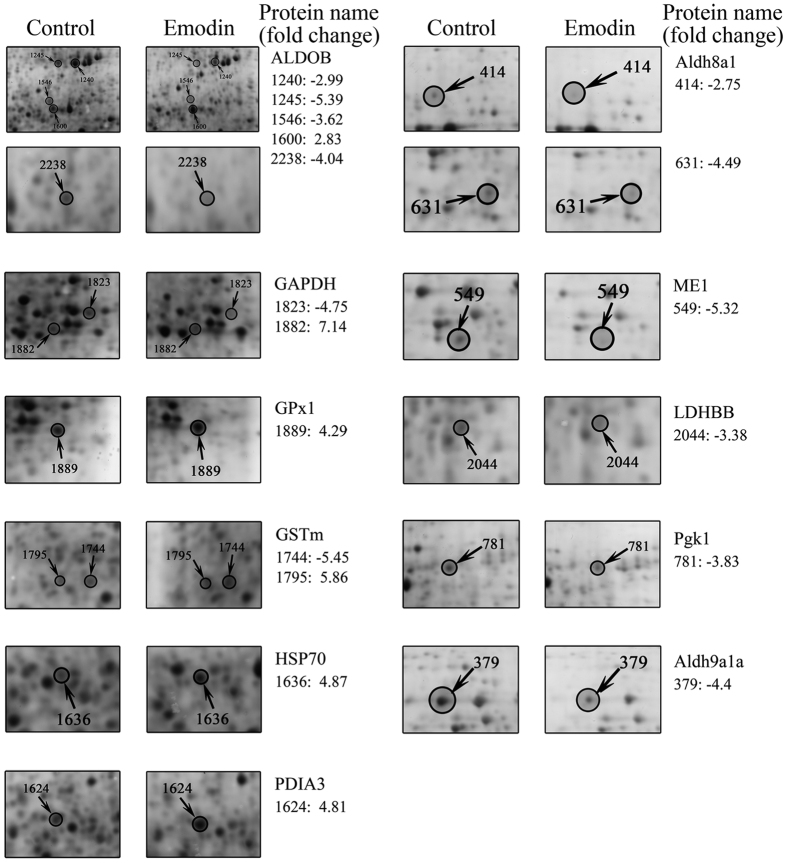

The mRNA and protein expression trends observed for antioxidant-related proteins were generally influenced by dietary emodin (shown in Figs 3 and 4). More precisely, the representative 2D protein profiles of the control and 30 mg kg−1 emodin groups are shown in Fig. 3. GPx1, GSTm and HSP70 were up-regulated at the mRNA and protein levels in the 30 mg kg−1 group compared with the control group, while GAPDH and Sord were down-regulated at both levels. Conversely, the expression levels of Pgk1 and Aldh8a1 were up- and down-regulated at mRNA and protein levels, while ALDOB was down-regulated at the mRNA level but up-regulated at the protein level. Briefly, these results suggested that the 10 altered antioxidant-related proteins might be involved in the enhancement of antioxidation in M. amblycephala via a complex molecular regulatory mechanism.

Figure 4. Emodin-responsive changes in the abundance of antioxidant-related proteins.

Differentially expressed proteins with increased or decreased abundance are marked in the control and 30 mg kg−1 groups. Fold changes of protein spots are mentioned on the right side.

Heatmap analysis of altered proteins at mRNA and protein levels

Figure 5 presents the heatmap based on the Spearman correlation matrix of the antioxidant-related altered proteins. In this figure, the proteins were clustered into 3 groups based on the mRNA and protein expression under 30 mg kg−1 emodin stimulation: ALDOB, GAPDH, and Sord representing the first group; GPx1, GSTm, and HSP70 the second group; and Pgk1 and Aldh8a1 the third group. The heatmap results indicated that the expression patterns of the second clustered group under emodin stimulation were up-regulated at both mRNA and protein levels compared with the control group. Meanwhile, the expressions in the third clustered group were up-regulated and down-regulated at mRNA and protein levels, respectively.

Figure 5. Heatmap of antioxidant-related altered proteins based on mRNA and protein expressions.

In this figure, weak and strong correlations between variables are displayed in green and red, respectively. The dendrogram for strain clustering is shown on the left-hand side of the heatmap. The width of the cluster merged from the left side represents the distance of the two clusters.

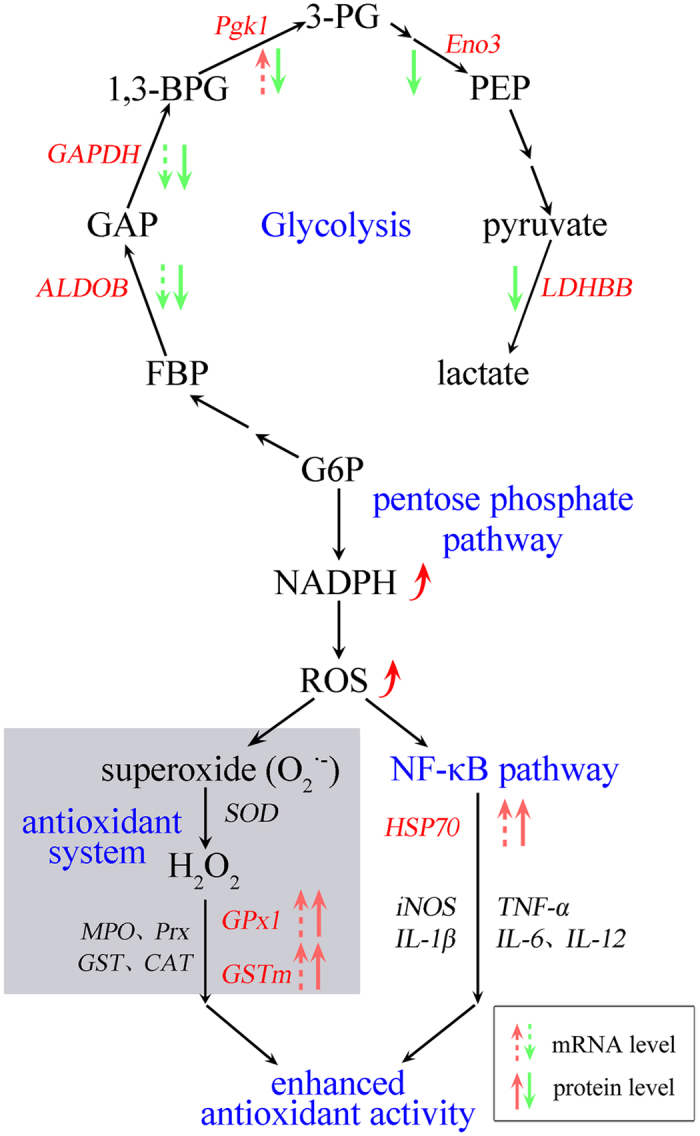

Emodin induced antioxidant mechanism analysis

Antioxidant mechanism induced by dietary emodin is elucidated in Fig. 6. The down-regulated expression of altered proteins (ALDOB, GAPDH, Pgk1, Eno3, and LDHBB) inhibited the glycolysis pathway, but inversely activated NADPH through pentose phosphate pathway (PPP). Simultaneously, NADPH stimulated ROS production, then activated the antioxidant system and NF-κB pathway by enhancing the expression of GPx1, GSTm, and HSP70, which synergically enhanced the antioxidant mechanism. These results were complemented with the network interaction and GO annotation analysis.

Figure 6. Antioxidant-related mechanism of altered proteins under emodin stimulation in M. amblycephala.

Abbreviations in red represent the altered proteins in present study. Dashed arrows are used for mRNA expression, and solid arrows are used for protein expression. The up-arrow in red represents up-regulation, and down-arrow in green represents down-regulated. G6P, glucose-6-phosphate; FBP, fructose-1,6-bisphosphate; GAP, glyceraldaldehyde-3-phosphate; 1,3-BPG, 1,3-bisphosphoglycerate; 3-PG, 3-phosphoglycerate; PEP, phosphoenolpyruvate; SOD, superoxide dismutase; MPO; CAT, catalase; NF-κB, nuclear factor κappa Β; iNOS, inducible nitric oxide synthase; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor-α; IL-1β, Interleukins-1β; IL-6, Interleukins-6; IL-12, Interleukins-12.

Discussion

In the present study, the identified proteins were functionally categorized and annotated according to the gene ontology of biological processes and molecular functions. Accordingly, the altered proteins could be classified into 9 categories, indicating their complex regulatory relationships in response to dietary emodin. To gain deeper insight into the antioxidant mechanism induced by dietary emodin, the uniquely altered proteins were then subjected to the network instruction and GO annotation. Protein-protein interaction networks provided insights into the functional mechanisms of living cells31. GO annotation analysis of the differentially expressed proteins revealed more information about protein functions in the antioxidant pathway. Notably, 15 proteins were involved in the interaction network, and interestingly, 10 of them were directly regulated by each other and functionally related to antioxidation. These results revealed that the administration of dietary emodin had significant effects on the regulation of antioxidation in M. amblycephala, and the 10 altered proteins might play important roles in the antioxidant response to dietary emodin.

Moreover, 2 altered cytoskeleton proteins of krt8 and krt18 were not involved in the network interaction, while the other 5 network interacted proteins (EEF2b, Eno3, Bhmt, AST, and ApoA1), which were respectively identified as nucleotide metabolism, carbohydrate metabolism, cofactors, amino acid metabolism and signal transduction proteins, were not related to antioxidation.

To clearly elaborate the dynamics underlying the expression of antioxidant-related proteins at the transcript level, 8 proteins that were closely related to antioxidant metabolism were subjected to mRNA expression analysis by RT-PCR. All quantified mRNA levels exhibited highly dynamic mRNA profiles from the control to the 120 mg kg−1 emodin group. Some proteins showed different expression patterns at the mRNA compared with those at the protein level. For example, Pgk1 and Aldh8a1 were up-regulated at the mRNA level but down-regulated at the protein level, while ALDOB was down-regulated at the mRNA level but up-regulated at the protein level, which potentially revealed the evidence that transcription and translation are differentially regulated and timed. In addition, these results will urge us to be careful when interpreting the mechanisms underlying protein expression at the transcriptional or translational level. Briefly, the gene-specific unique mRNA expression patterns supported the importance of antioxidant-related gene regulations during emodin administration.

We also applied a so-called heatmap analysis to the Spearman correlation matrix. The heatmap also re-arranges the rows and columns of the data so that similar rows, and similar columns, are grouped together, with their similarity represented by a dendrogram. The heatmap results indicated that the key variables of altered proteins stimulated by dietary emodin are comparable with the results from the RT-PCR analysis.

Liver is one of the most important organs for obtaining an overall assessment of the immune response and antioxidant activity. In this study, 10 uniquely expressed proteins in liver were functionally related to antioxidation based on a proteomic analysis.

One remarkable change in the proteome in response to emodin administration was the alteration of antioxidant proteins32. GPx, an antioxidant enzyme, is an important component of the antioxidant system, together with SOD, CAT, and GST. The level of GPx activity reflects the redox level in the fish body, and is a common physiological index to quantify oxidative stress in fish33. GSTm is a membrane-bound protein that has been shown to protect cells against oxidative stress34,35. Over-expression of GSTm can impact antioxidant stress status via lipid oxidation36. In the present study, both enzymes substantially increased at mRNA and protein levels in response to emodin administration, potentially because they had a common substrate of reduced glutathione. These results were consistent with previous reports that emodin could enhance antioxidant levels37,38. Thus, the two enzymes are the primary defense components and play an important role in cellular protection against adverse effects and in the antioxidant pathway.

In the present study, a chaperone protein (HSP70) was functionally related to antioxidant metabolism. There is growing evidence that over expressed HSP70 can mediate oxidative activity39. Another research in our lab also demonstrated that HSP70 could have the relationship with antioxidant system13. HSP70 protects cells against oxidative damage either due to necrosis or apoptosis40,41. For example, HSP70 is a potent regulator of inflammation because of its ability to prevent activation of the NF-κB pathway42. Moreover, it has been well documented that oxidative stress, especially hyperoxia, stimulates the expression of HSP7043. In addition, ROS are well known to cause protein misfolding44. HSP70 is integrally related to antioxidation by regulating the ROS level and modulating the redox status of the cytosol via reactions between their cysteine groups and cytochrome C41,45. In the present study, HSP70 was up-regulated following emodin administration, which was consistent with our previous studies7, and equivalent findings have been reported in other aquatic animals46,47. In summary, we hypothesize that HSP70 can alleviate antioxidant stress via a mutual regulation of other identified proteins.

Among the altered proteins in the liver of M. amblycephala, ALDOB and GAPDH have been associated with energy metabolism. ALDOB and GAPDH are well known for their role in glycolysis36,48. In addition to the roles in antioxidant regulation, these two proteins have also been implicated in apoptosis and cellular stress49,50, as well as frequently associated with oxidative stress51,52. In the present study, ALDOB was down-regulated at the mRNA level but up-regulated at protein level, while GAPDH was down-regulated at both levels. These expression patterns may potentially due to more efficient transport and utilization of nutrition, which results in an increase in the energy available for growth53. In addition, it might reflect the differences in energy demands between emodin administration and the control groups. Moreover, apoptosis has been linked to inflammation54, and the increased expression of ALDOB and decreased expression of GAPDH at protein level were associated with increased expressions of HSP70, GPx1, and GSTm in the present study, revealing enhanced immunity.

Moreover, proteins that play a role in carbohydrate metabolism (Pgk1 and Aldh8a1) were also altered under emodin administration. Pgk1 was reported to suppress ROS production and coordinate glycolysis and the TCA cycle55, which have been shown to decrease oxidative stress55,56. In the present study, the interaction network also demonstrated that these carbohydrate-associated proteins might modulate antioxidant activity. For example, Pgk1 and Aldh8a1 were all up-regulated at the mRNA level but down-regulated at the protein level in response to emodin administration, which might provide the evidence that transcription and translation are differentially regulated and timed.

Meanwhile, the antioxidant-related mechanisms highlight the modulation of altered proteins involved in the glycolysis, pentose phosphate pathway, NF-κB pathway, and antioxidant system. In the current study, the glycolysis process was suppressed with the regulating of ALDOB, GAPDH, Pgk1, Eno3 and LDHBB under dietary emodin stimulation. Reports also suggested that there was a metabolic balance of glucose-6-phosphate (G6P) consumption between pentose phosphate pathway (PPP) and glycolysis57, and increased G6P could activate NADPH58. Besides, the NADPH oxidase enzymes (NOXes) are the major sources of ROS59. Therefore, ROS was generated with the activation of NADPH. The ROS induced enhancement of antioxidant activity has been well documented60. NF-κB is targeted as an integral messenger in the enhancement of the response to environmental perturbation, which activates a series of cellular genes including HSP70, iNOS, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-12 and TNF-α41,61,62 to enhance the antioxidant mechanism. Consequently, dietary emodin enhanced the antioxidant mechanism by glycolysis, pentose phosphate pathway, NF-κB pathway and antioxidant system. A complete understanding of the mechanisms underlying this pattern of expression requires further elucidation of protein functions, modification, regulation, and protein-protein interactions, but we speculate that the regulation at the protein level might reflect a low level of inflammation and oxidative stress in the M. amblycephala. Furthermore, these up- or down-regulated proteins play important roles in the oxidative defense of fish.

In conclusion, the present work revealed that 10 altered proteins were involved in antioxidant process by regulating each other, suggesting the beneficial effects of dietary emodin on antioxidant mechanisms in M. amblycephala. Our data showed that 27 protein spots responded to 30 mg kg−1 dietary emodin, all of which were successfully identified (6 up-regulated and 21 down-regulated), representing 17 unique proteins. The results also explicitly demonstrated that 30 mg kg−1 dietary emodin induced different expression patterns of various antioxidant related proteins at the transcript level (GPx1, GSTm, HSP70, Pgk1, and Aldh8a1 were increased, and ALDOB, GAPDH, and Sord were decreased). The altered proteins were directly regulated by each other, and 10 proteins categorized as related to energy metabolism, antioxidants, chaperones, and carbohydrate metabolism were responsible for the reduction of oxidative stress. Although additional work is required to evaluate the precise regulatory mechanisms of the identified proteins, the results of the present study may indicate the antioxidative properties of dietary emodin in M. amblycephala.

Methods

Ethics statement

This study was approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Nanjing Agricultural University (Nanjing, China). All animal procedures were performed according to the Guideline for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals in China.

Experimental animals and feeding experiments

Healthy M. amblycephala fingerlings with an average weight of 3.94 ± 0.15 g were obtained from the Freshwater Fisheries Research Center, Chinese Academy of Fishery Sciences. Two weeks acclimation was conducted prior to the feeding experiments. After acclimation, 375 fishes were randomly distributed into five groups (15 circular fiberglass tanks, 300 L water/tank, 3 tanks/group, 25 individuals/tank): the control group fed the basal diet (0 mg kg−1 emodin) and the treatment groups fed experimental diets (15, 30, 60 and 120 mg kg−1 emodin) by hand to apparent satiation three times daily (08:30, 12:00, and 16:00) for 8 weeks.

The emodin used in this study was purchased from Xi’an Feida Bio-Tech Co., Ltd, China (purity >99%). Formulation of the experimental diets and environmental quality preferences were performed according to established protocols12.

Sample collection and soluble protein preparation

After a rearing period of 8 weeks, the fish were fasted for 24 h, and then 9 livers from each group (3 individuals/tank, 3 tanks/group) were dissected individually, frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80 °C for further analysis. The 3 livers (0.5 g/each) in each tank of the control and 30 mg kg−1 group were randomly mixed together and chopped into 3 mm × 3 mm pieces. Protein extraction was performed using a homogenizer in lysis buffer containing 7 M urea, 2 M thiourea, 65 mM Tris, 4% CHAPS and 0.2% IPG buffer; enzyme inhibitor was added simultaneously at a ratio of 50:1. Protein extracts were centrifuged at 12000 rpm for 30 min at 4 °C, washed three times, lyophilized and re-dissolved in lysis buffer. The protein concentration was estimated using a modified Bradford assay (Bio-Rad, USA) with BSA as a standard63.

Two-dimensional gel electrophoresis

Three biological replicates in each group were considered for 2-DE analysis. The preliminary experiment showed that the pI of most proteins ranged from 4 to 7, and the strip of 4–7 exhibited a clearer 2-DE spectrum. In order to achieve a better separation of liver proteins, a narrow strip of 4–7 was employed for further analysis. A total of 500 μg of liver proteins in rehydration buffer (7 M Urea, 2 M thiourea, 4% CHAPS, 65 mM DDT and 3.4 μl of IPG buffer) was used to rehydrate the IPG strip (7 cm, pH 4–7, Bio-Rad, USA) for 16 h. The IEF was performed at a constant temperature of 20 °C with a continuous increase in voltage up to 8000 V with an Ettan IPGphor Isoelectric Focusing System (GE Amersham, Sweden). For second dimension electrophoresis, 14% SDS-PAGE was performed using a Hofer SE 600 (GE Amersham, Sweden) system.

The gel was stained with Coomassie G-250 (10% w/v ammonium sulfate, 10% v/v phosphoric acid, 20% v/v methanol and 0.12% w/v CBB G-250) for at least 2 h until saturation, then destained in water for 30 min until the background is clear.

Image analysis

The 2-DE images were scanned with a UMAX Power Look 1120 scanner (UMAX, Taiwan) at 400 dpi and analyzed with Image Master 2D Platinum 6.0 (GeneBiology, Sweden). Comparative analysis of the protein spots was conducted by matching corresponding spots across different gels. The spot intensity was quantified by total spot volume normalization, and the statistical comparison was performed using the resulting spot volume percentage. Only proteins with significant changes (P < 0.05, up/down-regulation ≥2.0-fold) were considered differentially expressed and subjected to subsequent identification by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry.

MALDI-TOF-MS and MS/MS

To identify the proteins of interest, the altered spots were subjected to MALDI-TOF analysis. Before MS analysis, the differentially expressed protein spots were manually excised from the gels for in-gel digestion. The gel pieces were digested in 10 μg/mL trypsin at 37 °C for 24 h. The digested samples were collected and vacuum-dried, dissolved in 50% v/v ACN containing 5% v/v TFA and subjected to MALDI-TOF/TOF.

MS spectra were obtained using ReFlexTM III MALDI-TOF (Bruker, Germany), and peptide mass maps were acquired in reflectron mode (20 kV and 23 kV accelerating voltage) with 100 laser shots per spectrum. For MS/MS spectra, 8 abundant precursor ions per sample were selected for subsequent fragmentation using 2000 laser shots per precursor ion. The selected peptides were submitted to Mascot for an NCBInr database search (database downloaded in February 10, 2012), and the tolerance was set at 1 Da. High confidence identifications with statistically significant search scores (P < 0.05) were regarded as a positive identification.

Network construction and GO annotation

The associated interaction data and score were extracted from STRING (Version 10.0, http://string-db.org/). The protein network was constructed based on data retrieved and protein expression using Cytoscape 3.1.2 for further analysis.

Gene Ontology (GO) annotation of altered proteins was performed by DAVID (Version 6.7, https://david.abcc.ncifcrf.gov/) based on the information obtained for BP (Biological Processes), MF (Molecular Functions) and CC (Cellular Components).

RNA extraction and RT-PCR analysis

Total RNA was extracted from 9 livers in each group using RNAiso Plus reagent (Dalian Takara Co. Ltd., China). Primers (shown in Table 2) for each gene were designed using primer premier 5.0 based on the mRNA sequences obtained from the M. amblycephala liver genome database of aquatic disease and feed laboratory of Freshwater Fisheries Research Center, Chinese Academy of Fishery Sciences (mRNA sequences were shown in Supplementary Material 4). All primers were synthesized by Shanghai Generay Biotechnology, Co., Ltd, China. Real-time quantitative PCR (RT-PCR) was performed according to Habte-Tsion64 with the SYBR® Primix Ex TaqTM II (TliRNase Plus) Kit using an ABI 7500 Real-time PCR System. The relative expression levels of the target genes were normalized to the housekeeping M. amblycephala gene β-actin, and further calculated using the double-standard curve method65.

Table 2. Primer sequences for RT-PCR analysis of antioxidant related genes.

| Genes | Primer sequences (5′ → 3′) | Product size (bp) | Amplification efficiency (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| β-actin | (F) TCTGCTATGTGGCTCTTGACTTCG | 132 | 94.27 |

| (R) CCTCTGGGCACCTGAACCTCT | |||

| ALDOB | (F) AGGACAAGGGCATCGTAGTTGGTAT | 137 | 103.89 |

| (R) GTCACAACCGTCCTTTTTGTACTGG | |||

| GAPDH | (F) TGGTGCCAGTCAGAACATCA | 196 | 98.97 |

| (R) TGCAGCCTTGACGACTTTCT | |||

| GPx1 | (F) GAACGCCCACCCTCTGTTTG | 122 | 97.75 |

| (R) CGATGTCATTCCGGTTCACG | |||

| GSTm | (F) AACCTCTGTGGGGAAACTGAAGAAG | 150 | 92.53 |

| (R) TAGAGTTCCTGGCAGATTCTCATCG | |||

| HSP70 | (F) CGACGCCAACGGAATCCTAAAT | 92 | 95.87 |

| (R) CTTTGCTCAGTCTGCCCTTGT | |||

| Pgk1 | (F) GCCTTTACCTTCCTCAAGGTTCTCA | 150 | 96.79 |

| (R) GTCTGCAGTGATGAAGTCAACAGGA | |||

| Aldh8a1 | (F) ACATTCCACGATCAGCGTACAACTT | 177 | 98.38 |

| (R) TCTTCCAGGTCAGGAGATACAGTGG | |||

| Sord | (F) GAGCAGCATTCAAACAGCCATCTAT | 104 | 98.94 |

| (R) CTGCTGCATTCAGAAGAGGTATGGT |

Primers for each gene were designed using primer premier 5.0. Amplification efficiency was determined according to RT-PCR analysis.

Heatmap analysis

The heatmap was conducted in R with the pheatmap package. The input data is a 4 by 8 symmetric Spearman correlation matrix. The rows and columns are reordered by dendrogram, because of the symmetry of the input data, rows and columns are rearranged in the same order.

Data analysis

Duncan’s multiple range test was used to analyze the RT-PCR results after one-way ANOVA in SPSS (version 19.0), and an independent samples t-test was conducted to analyze the protein expressions. All results are expressed as the mean ± standard error of the mean (X ± SEM).

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Song, C. et al. Comparative proteomic analysis of liver antioxidant mechanisms in Megalobrama amblycephala stimulated with dietary emodin. Sci. Rep. 7, 40356; doi: 10.1038/srep40356 (2017).

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Technology System for Conventional Freshwater Fish Industries, the Modern Agriculture Industrial Technology System (CARS-46), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31572662), the National Nonprofit Institute Research Grant of Freshwater Fisheries Research Center, Chinese Academy of Fishery Sciences (2014A08XK02), the Independent Innovation of Agricultural Science and Technology in Jiang-su province (CX(16)1004) and the Three New Projects of Fishery in Jiangsu province (D2016-18). The authors gratefully acknowledge the postgraduate students of the Fish Disease and Nutrition Department, FFRC, CAFS, Wuxi City, PR China for their assistance during the sampling period.

Footnotes

Author Contributions C.S., B.L., and P.X. conceived and designed the research. J.X. and M.R. provided essential reagents and materials for the research. C.S., Y.Z., Z.Z., H.Z., Q.Z and L.H. conducted the experiment. C.S., J.X. and X.G. analyzed the data. C.S. and B.L. wrote the paper. B.L. and P.X. revised the paper. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

References

- Sakai M. Current research status of fish immunostimulants. Aquaculture. 172, 63–92 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- Purivirojkul W., Areechon N. & Srisapoome P. The Effect of peptidoglycan on Immune response in black tiger shrimp (Penaeus monodon Fabricius). Kasetsart J. (Nat Sci.). 40, 181–187 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- Qiao J. et al. Proteomic identification of the related immune-enhancing proteins in shrimp Litopenaeus vannamei stimulated with vitamin C and Chinese herbs. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 31, 736–745 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sesay D. F. et al. Effects of dietary folic acid on the growth, digestive enzyme activity, immune response and antioxidant enzyme activity of blunt snout bream (Megalobrama amblycephala) fingerling. Aquaculture. 452, 142–150 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- Esteban M. A. et al. Effect of dietary supplementation of probiotics and palm fruits extracts on the antioxidant enzyme gene expression in the mucosae of gilthead seabream (Sparus aurata L.). Fish Shellfish Immunol. 39, 532–540 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abu-Elala N. M., Mohamed S. H., Zaki M. M. & Eissa A. E. Assessment of the immune-modulatory and antimicrobial effects of dietary chitosan on Nile tilapia (Oreochrmis niloticus) with special emphasis to its bio-remediating impacts. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 46, 678–685 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu B. et al. Effects of anthraquinone extract from Rheum officinale Bail on the physiological responses and HSP70 gene expression of Megalobrama amblycephala under Aeromonas hydrophila infection. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 32, 1–7 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei W. T., Lin S. Z., Liu D. L. & Wang Z. H. The distinct mechanisms of the antitumor activity of emodin in different types of cancer (Review). Oncol Rep. 30, 2555–2562 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shrimali D. et al. Targeted abrogation of diverse signal transduction cascades by emodin for the treatment of inflammatory disorders and cancer. Cancer Lett. 341, 139–149 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen R. et al. Potential antineoplastic effects of Aloe-emodin: a comprehensive review. Am J Chin Med. 42, 275–288 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ming J. et al. Effects of emodin and vitamin C on growth performance, biochemical parameters and two HSP70s mRNA expression of Wuchang bream (Megalobrama amblycephala Yih) under high temperature stress. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 32, 651–661 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y. Y. et al. Effects of dietary emodin supplementation on growth performance, non-specific immune responses, and disease resistance to Aeromonas hydrophila in juvenile Wuchang bream (Megalobrama amblycephala). Isr J Aquacult-Bamid. 66, 1–9 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu B. et al. Effects of emodin and vitamin E on the growth and crowding stress of Wuchang bream (Megalobrama amblycephala). Fish Shellfish Immunol. 40, 595–602 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akhgari M., Abdollahi M., Kebryaeezadeh A., Hosseini R. & Sabzevari O. Biochemical evidence for free radical induced lipid peroxidation as a mechanism for subchronic toxicity of malathion in blood and liver of rats. Hum Exp Toxicol. 22, 205–211 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sohn H. Y., Kwon C. S., Kwon G. S., Lee J. B. & Kim E. Induction of oxidative stress by endosulfan and protective effect of lipid-soluble antioxidants against endosulfan-induced oxidative damage. Toxicol Lett. 151, 357–365 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escobedo J., Pucci A. M. & Koh T. J. HSP25 protects skeletal muscle cells against oxidative stress. Free Radical Biol Med. 37, 1455–1462 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baud O. et al. Developmental up-regulation of MnSOD in rat oligodendrocytes confers protection against oxidative injury. Eur J Neurosci. 20, 29–40 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierce A. et al. GAPDH is conformationally and functionally altered in association with oxidative stress in mouse models of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Mol Biol. 382, 1195–1210 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin S. A. M., Cash P., Blaney S. & Houlihan D. F. Proteome analysis of rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) liver proteins during short term starvation. Fish Physiol Biochem. 24, 259–270 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- Vilhelmsson O. T., Martin S. A., Médale F., Kaushik S. J. & Houlihan D. F. Dietary plant-protein substitution affects hepatic metabolism in rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss). Brit J Nutr. 92, 71–80 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunt J., Hansen R., Jamieson D. J. & Austin B. Proteomic analysis of rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss, Walbaum) serum after administration of probiotics in diets. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 121, 199–205 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sissener N. H. et al. Proteomic profiling of liver from Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) fed genetically modified soy compared to the near-isogenic non-GM line. Mar Biotechnol. 12, 273–281 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X., Yap Y., Wei D., Chen G. & Chen F. Novel omics technologies in nutrition research. Biotechnol Adv. 26, 169–176 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kussmann M., Raymond F. & Affolter M. OMICS-driven biomarker discovery in nutrition and health. J Biotechnol. 124, 758–787 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kussmann M., Rezzi S. & Daniel H. Profiling techniques in nutrition and health research. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 19, 83–99 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Agriculture of the People’s Republic of China, Chinese Fisheries Yearbook, Chinese Agricultural Press, Beijing, (2015).

- Liu B. et al. Effects of anthraquinone extract from Rheum officinale Bail on the growth performance and physiological responses of Macrobrachium rosenbergii under high temperature stress. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 29, 49–57 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ojolick E. J., Cusack R., Benfey T. J. & Kerr S. R. Survival and growth of all-female diploid and triploid rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) reared at chronic high temperature. Aquaculture. 131, 177–187 (1995). [Google Scholar]

- Jeney G., Galeotti M., Volpatti D., Jeney Z. & Anderson D. P. Prevention of stress in rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) fed diets containing different doses of glucan. Aquaculture. 154, 1–15 (1997). [Google Scholar]

- Winzer K., Noorden C. & Köhler A. Sex-specific biotransformation and detoxification after xenobiotic exposure of primary cultured hepatocytes of Europeanflounder (Platichthysflesus L.). Aquat Toxicol. 59, 17–33 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marteau P., Pochart P., Bouhnik Y. & Rambaud J. The fate and effects of transiting, nonpathogenic microorganisms in the human intestine. World Rev Nutr Diet. 74, 1–21 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tenorio-Laranga J., Männistö P. T., Karayiorgou M., Gogos J. A. & García-Horsman J. A. Sex-dependent compensated oxidative stress in the mouse liver upon deletion of catechol O-methyltransferase. Biochem Pharmacol. 77, 1541–1552 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan J., Cai H., Yang S., Yan L. & Tan W. Comparison between the effects of normoxia and hypoxia on antioxidant enzymes and glutathione redox state in ex vivo culture of CD34+ cells. Comp Biochem Physiol., Part B: Biochem Mol Biol. 151, 153–158 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosialou E., Ekström G., Adang A. E. & Morgenstern R. Evidence that rat liver microsomal glutathione transferase is responsible for glutathione-dependent protection against lipid peroxidation. Biochem Pharmacol. 45, 1645–1651 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeda A., Crabb J. W. & Palczewski K. Microsomal glutathione S-transferase 1 in the retinal pigment epithelium: protection against oxidative stress and a potential role in aging. Biochemistry. 44, 480–489 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamza N. et al. Differential protein expression profile in the liver of pikeperch (Sander lucioperca) larvae fed with increasing levels of phospholipids. Comp Biochem Physiol., Part D: Genomics Proteomics. 5, 130–137 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du Y. & Ko K. Effects of emodin treatment on mitochondrial ATP generation capacity and antioxidant components as well as susceptibility to ischemia-reperfusion injury in rat hearts: Single versus multiple doses and gender difference. Life Sci. 77, 2770–2782 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tao L. et al. Protective effects of aloe-emodin on scopolamine-induced memory impairment in mice and H2O2-induced cytotoxicity in PC12 cells. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 24, 5385–5389 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi A. et al. Oxidative stress-induced expression of HSP70 contributes to the inhibitory effect of 15d-PGJ 2 on inducible prostaglandin pathway in chondrocytes. Free Radical Biol Med. 76, 114–126 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H. P. et al. Heat shock protein-70 mediates the cytoprotective effect of carbon monoxide: involvement of p38β MAPK and heat shock factor-1. J Immunol. 175, 2622–2629 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravagnan L. et al. Heat-shock protein 70 antagonizes apoptosis-inducing factor. Nat Cell Biol. 3, 839–843 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Y. et al. The inhibition of LPS-induced production of inflammatory cytokines by HSP70 involves inactivation of the NF-κB pathway but not the MAPK pathways. Shock. 26, 277–284 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landis G. N. et al. Similar gene expression patterns characterize aging and oxidative stress in Drosophila melanogaster. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 101, 7663–7668 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freedman R. B., Hirst T. R. & Tuite M. F. Protein disulphide isomerase: building bridges in protein folding. Trends Biochem Sci. 19, 331–336 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalmar B. & Greensmith L. Induction of heat shock proteins for protection against oxidative stress, Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 61, 310–318 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ming J. et al. Molecular cloning and expression of two HSP70 genes in the Wuchang bream (Megalobrama amblycephala Yih). Fish Shellfish Immunol. 28, 407–418 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z., Wu Z., Jian J. & Lu Y. Cloning and expression of heat shock protein 70 gene in the haemocytes of pearl oyster (Pinctada fucata, Gould 1850) responding to bacterial challenge. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 26, 639–645 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liiv I. et al. AIRE-induced apoptosis is associated with nuclear translocation of stress sensor protein GAPDH. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 423, 32–37 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh S. et al. Aldehyde dehydrogenases in cellular responses to oxidative/electrophilicstress. Free Radical Bio Med. 56, 89–101 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hara M. R. et al. S-nitrosylated GAPDH initiates apoptotic cell death by nuclear translocation following Siah1 binding. Nat Cell Biol. 7, 665–674 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ralser M. et al. Dynamic rerouting of the carbohydrate flux is key to counteracting oxidative stress. J Biology. 6, 1–18 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tristan C., Shahani N., Sedlak T. W. & Sawa A. The diverse functions of GAPDH: Views from different subcellular compartments. Cell Signal. 23, 317–323 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuang D. M., Hough C. & Senatorov V. V. Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase, apoptosis, and neurodegenerative diseases*. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 45, 269–290 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haanen C. & Vermes I. Apoptosis and inflammation. Mediators Inflammation 4, 5–15. (1995) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X. et al. Mitochondria-Translocated PGK1 Functions as a Protein Kinase to Coordinate Glycolysis and the TCA Cycle in Tumorigenesis. Mol Cell. 61, 705–719 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J. et al. Characterization of phosphoglycerate kinase-1 expression of stromal cells derived from tumor microenvironment in prostate cancer progression. Cancer Res. 70, 471–480 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Rodriguez R. P., Almeida A. & Bolaños J. P. Brain energy metabolism in glutamate-receptor activation and excitotoxicity: role for APC/C-Cdh1 in the balance glycolysis/pentose phosphate pathway. Neurochem Int. 62, 750–756 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winston G. W., Moore M. N., Kirchin M. A. & Soverchia C. Production of reactive oxygen species by hemocytes from the marine mussel, Mytilus edulis: lysosomal localization and effects of xenobiotics. Comp Biochem Physiol., Part C: Pharmacol., Toxicol. Endocrinol. 113, 221–229 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambeth J. NOX enzymes and the biology of reactive oxygen, Nat Rev Immunol. 4, 181–189 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nordberg J. & Arner E. Reactive oxygen species, antioxidants, and the mammalian thioredoxin system. Free Radical Biol Med. 31, 1287–1312 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S. L., Degli Esposti S., Yao T., Diehl A. M. & Zern M. A. Vitamin E therapy of acute CCl4-induced hepatic injury in mice is associated with inhibition of nuclear factor kappa B binding. Hepatology. 22, 1474–1481 (1995). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reyes G. K. et al. Curcumin protects against acute liver damage in the rat by inhibiting NF-κB, proinflammatory cytokines production and oxidative stress. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1770, 989–996 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramagli L. & Rodriguez L. Quantitation of microgram amounts of protein in two-dimensional polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis sample buffer. Electrophoresis. 6, 559–563 (1985). [Google Scholar]

- Habte-Tsion H. M. et al. Threonine influences the absorption capacity and brush-border enzyme gene expression in the intestine of juvenile blunt snout bream (Megalobrama amblycephala). Aquaculture. 448, 436–444 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- Tang Y. & Jia Y. The processing method study of real-time PCR data. Biotechnology. 18, 89–91 (In Chinese) (2008). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.