Abstract

Introduction

Subjects who undergo haemodialysis are living longer, which necessitates increasingly complex procedures for formation of arteriovenous fistulas. Basilic veins provide valuable additional venous ‘real estate’ but surgical transposition of vessels is required, which required a cosmetically disfiguring incision. A minimally invasive transposition method provides an excellent aesthetic alternative without compromised outcomes.

Methods

A retrospective review was made of minimally invasive brachiobasilic fistula transpositions (using two short incisions of <4 cm) between February 2005 and July 2011. Primary endpoints were one-year patency as well as the perioperative and late complications of the procedure.

Results

Thirty-one patients underwent 32 transposition procedures (eight pre-dialysis cases; 24 haemodialysis patients). All patients were treated with a minimally invasive method. Thirty-one procedures resulted in primary patency, with the single failure refashioned successfully. The only indication for a more invasive approach was intraoperative complications (two haematomas). All other complications presented late and were amenable to intervention (one aneurysm, one peri-anastomotic stricture).

Conclusion

Formation of arteriovenous fistulae using minimally invasive methods is a novel approach that ensures fistula patency with improved aesthetic outcomes and without significant morbidity.

Keywords: Arteriovenous fistula, Patency, Minimally invasive, vascular access

Timely and efficient provision of vascular access surgery (VAS) is crucial for ensuring optimal outcomes for patients requiring haemodialysis (HD) for renal replacement therapy (RRT). This requirement is coupled with a HD population in the UK that is increasing.1,2 Failure of vascular access (particularly loss of primary functional patency of a surgically created access) is difficult to estimate accurately in native arteriovenous fistulae (AVFs) after one year due to conflicting reports and potential inaccuracies in data collation, but are often quoted to approach 25–30%.3,4 One meta-analysis reported a prevalence of primary and secondary patency of radiocephalic AVFs at one year of 62.5% and 66%, respectively, with considerably worse results in prosthetic grafts.5

This scenario has resulted in maximisation of venous ‘real estate’ for further interventions, as well as recommendations for use of autologous veins for HD access because of the potential necessity of further interventions.6 These problems are coupled with the inherent limitations of the kidneys available for transplantation as an alternative RRT modality.7

An ‘ideal’ AVF should remain patent and useable to enable prolonged and efficient HD but provision of such an ideal AVF involves challenges. Therefore, variations of the original description of a radiocephalic fistula for venous access have had to be formulated.8 Patients using HD as their preferred method of RRT are surviving longer. Therefore, they require more interventions to maintain the patency of vascular access with increasingly variable anatomical locations. After exhaustion of the options using the cephalic vein (radiocephalic and brachiocephalic AVFs), use of an autologous basilic vein (BV) to create a brachiobasilic arteriovenous fistula (BBAVF) may be used in preference to any form of synthetic graft.9,10

Use of the BV to create BBAVFs was described first in 1976.11 The BV offers numerous advantages over the cephalic vein. Due to its deep location in the upper arm, the BV is less likely to be subjected to repeated trauma or previous venepuncture. Therefore, it is less likely to be occluded or scarred upon assessment or at the time of surgery. In addition, it has a straight course and naturally good calibre, thereby maximising the chances of maturation and subsequent excellent opportunities for needling or HD.9 Recent series have quoted a prevalence of primary failure of 20% with a primary patency of 70%, though there has been wide variation (23–90%) between series.12,13 However, this anatomical position offers distinct challenges for obtaining surgical access.

The traditionally large and extensive dissection required for VAS results in a time-consuming and technically challenging procedure with significant perioperative morbidity.9 However, studies comparing BBAVF with upper-arm grafts have found improvements in primary and cumulative patency, coupled with a lower risk of infection, thereby ensuring that this option is the preferable form of secondary VAS.14,15

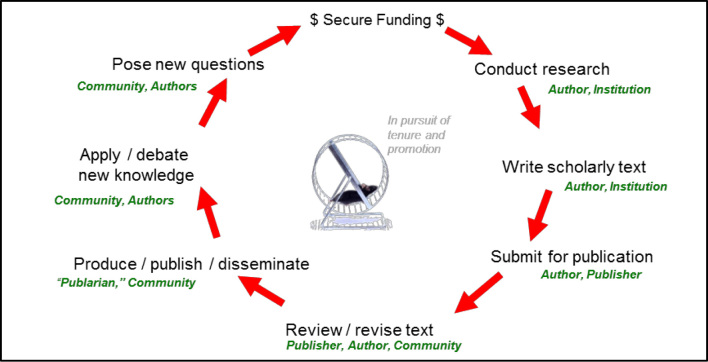

In a BBAVF, transposition of the BV is required to facilitate safe needling access. Such access can be achieved via a procedure synchronous to the arteriovenous anastomosis or as a metachronous two-staged procedure. Enthusiasts of a one-stage approach have quoted avoidance of an unnecessary second operation as an advantage, but this approach carries the appreciable risk of unnecessary morbidity if the initial procedure is unsuccessful.16 The two-stage approach with a large longitudinal incision in the medial aspect of the upper arm allows (i) avoidance of a general anaesthetic and an invasive procedure if primary patency is not achieved in an initial procedure and (ii) the technical advantages of the ease of mobilisation of a larger ‘arterialised’ vein (Figure 1).13,17

Figure 1.

Traditional longitudinal incision for transposition of the basilic vein has been associated with incisions that are disfiguring and painful (A) and associated with significant morbidity with unsightly cosmetic scarring (B).

The morbidity of the large incision is augmented by the impact of the delayed healing associated with end-stage renal failure. Surgical advances in recent decades have included the advent of minimally invasive methods. Such advances have allowed the time taken to return to functional activities to be shortened along with significant cosmetic improvements.

Logical progression of these advances within VAS is advent of a minimally invasive approach. Endoscopic approaches have been used in venous surgery for harvesting of the saphenous vein before coronary artery bypass grafting, and were described first in 1995.18,19 The significant morbidity and potential cosmetic disruption inherent in creation of BBAVFs suggest that this procedure may benefit considerably from a less invasive and more cosmetically acceptable approach.

Here we describe a minimally invasive approach for formation of BBAVFs employing two short incisions to assess the feasibility and acceptance of this approach. The effect that this approach may have upon fistula patency was also assessed, as were early and late postoperative complications.

Methods

Retrospective analyses of a contemporaneously maintained database of all patients who underwent a minimally invasive approach for creation of a BBAVF between February 2005 and July 2011 were undertaken.

All procedures were carried out consecutively by a single consultant surgeon at a single unit. Preoperatively, patients underwent assessment in a dedicated one-stop vascular access clinic. Assessment included a detailed history on vascular access, including details of all previous: VAS; clinical and arterial assessment; venous mapping with a proximal occluding cuff utilising Doppler ultrasonography of vessels.

In all cases, this assessment demonstrated no simple (cephalic) venous options for AVF formation. In accordance with local practice, BVs were deemed suitable for AVFs if >2.5 mm in diameter at elbow level using a proximal occluding cuff and, in accordance with established evidence and recent publications,20, 21 if they were compressible (not thrombosed) on vascular/clinical assessment. Venography of the assessed limb and central vein was also done upon clinician discretion if indicated by extensive previous use of central veins for venous access to exclude a central venous stenosis.

All BBAVFs in the present study were formed using a two-stage procedure with the first stage as described previously.11,17 Procedures were undertaken with the understanding and appropriate written informed consent of each patient. In accordance with guidance from the hospital, ethical approval was not sought.

Primary endpoints of the study were fistula patency (“primary” and “assisted primary” as defined using established standards) at six weeks and at one year.4 All patients were followed up for one year after the procedure unless excluded from further analyses and follow-up (death or successful transplantation). Secondary endpoints were surgical complications in perioperative and late (>6 weeks) settings.

Statistical analyses

A Kaplan–Meier curve was constructed for analyses of BBAVF patency. Statistical calculations were done using SPSS® v18.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA).

Surgical procedure

Four weeks after the initial vascular anastomosis (brachial or proximal radial artery to the BV), the patient was assessed (clinical, Doppler ultrasonography) to assess fistula maturation (adequate volume of flow as per local guidelines; BV dilatation; absence of clinically significant stenoses) before planning further surgery. If interventions were required to enable further surgery (second stage) then they were undertaken.

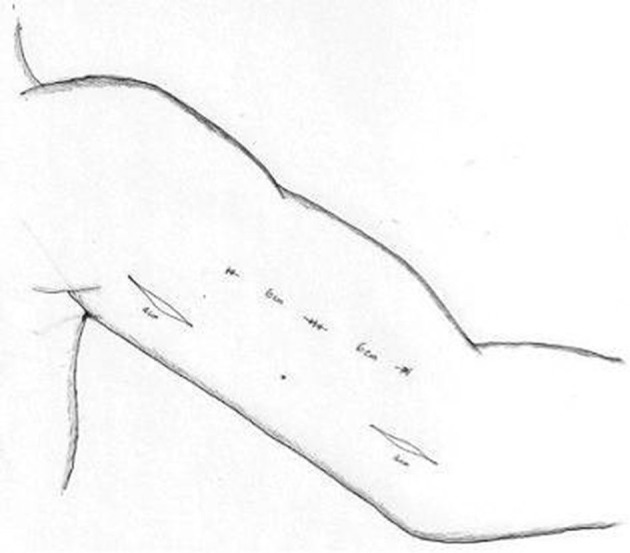

The second-stage procedure incorporated full mobilisation of the arterialised BV. Two short longitudinal incisions (each of length ≈4 cm) over the medial aspect of the upper arm were made (Figure 2). The lower incision was located directly over the anastomosis between the BV and brachial artery. This incision facilitated venous mobilisation with proximal extension for ≈6 cm towards the axilla with the aim of preservation of the medial cutaneous nerve of the forearm. This aim was achieved with full visualisation and meticulous preservation of the nerve. Location of this incision allows mobilisation of the proximal aspect of the vein in the juxta-anastomotic region, and allows full mobilisation of the area that is most prone to tethering by formation of scars and adhesions from the initial surgery (first stage).

Figure 2.

Surgical incisions employed to mobilise the basilic vein via two short longitudinal incisions (each <4 cm in diameter) over the medial aspect of the upper arm. The lower incision is placed near the anastomosis of the brachial artery and basilic vein to allow juxta-anastomotic mobilisation. The second incision is sited to allow maximal access to the vein along its course.

The procedure is carried out with the arm fully abducted at the shoulder to facilitate access to the entire length of the vein. It is undertaken under general anaesthesia as per conventional second-stage BBAVF formation unless prevented by patient comorbidities (in which case a regional block is employed). A single dose of antibiotics was given prophylactically upon induction of anaesthesia in all cases. This approach was carried out in all patients in the study, with body habitus not precluding the success of this approach.

Location of the upper incision is determined by the path of the BV projected onto the skin and as palpated digitally due to the fluid thrill through the arterialised vein. The distal margin of the upper incision is ≈12 cm from the proximal margin of the lower incision (Figure 2). Localisation is ascertained after maximal mobilisation of the BV using the proximal incision, and allows full distal venous mobilisation to the level of the axillary inlet. This strategy allows visualisation of the entire length of the BV because adequate retraction of skin of the area overlying the BV in the areas between the two incisions can be facilitated easily. This strategy also allows maximum potential mobilisation of the BV to enable superficialisation with minimal tension. The BV is transected after full mobilisation in the juxta-anastomotic region distally and tunnelled subcutaneously overlying the belly of the biceps muscle using a subcutaneous vascular tunneler, with subsequent anastomosis of the transected venous ends to facilitate subsequent needling for HD (Figures 3 and 4).13,17

Figure 3.

The basilic vein is mobilised away from the adjacent nerve, and side branches are ligated and divided routinely as distal as possible below the elbow crease to obtain a good length and to allow nerve preservation (A). The vein is then tunnelled subcutaneously (B) and reanastomosed in a pocket (C) to facilitate access for needling and a good cosmetic result (D).

Figure 4.

Healing of the wounds at six weeks resulted in marked cosmetic improvement in the appearance of the operated arm compared with that achieved using traditional methods.

Results

Thirty-one patients (15 males, 16 females; median age, 58 [range, 28–84] years) had 32 first-stage BBAVFs. Twenty-four patients were established on HD at the time of surgery, whereas eight cases had established end-stage renal failure but remained pre-dialysis. All patients underwent BBAVF formation using the method described above.

Primary patency after successful two-stage BBAVF formation (the primary endpoint) was achieved in 31 cases (96.8%) with one early failure (thrombosis detected at follow-up duplex ultrasound after first-stage BBAVF formation). This case was refashioned early (and achieved secondary patency) in the same patient using the same incisions (thereby accounting for multiple procedures in the same patient). No cases required any form of assisted maturation. There were no other primary failures.

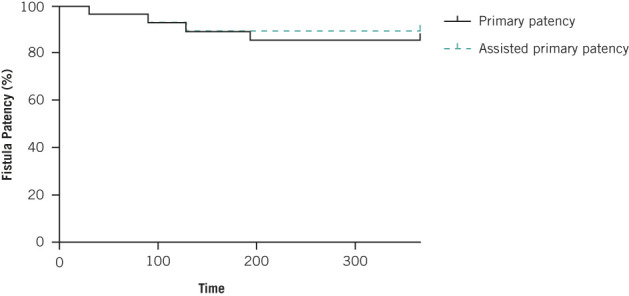

At one-year follow-up, 28 patients were evaluated (three patients were excluded – two deaths and one successful renal transplant – all excluded with patent fistulae) and demonstrating one-year primary patency of 85.7% (24/28) with assisted primary patency (two significant stenoses necessitating fistuloplasty) of 92.8% (26/28) (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Kaplan–Meier curve demonstrating primary (85%) and primary-assisted patency (93%) patency one year after BBAVF formation. These figures were censored for patient death and successful transplantation in the intervening period. All censored patients had patent BBAVFs at the time of exclusion.

In terms of further complications, there were two (8%) early haematomas in surgical wounds. Both settled with conservative management and did not require further surgical intervention. There were only two (8%) late complications: (i) a peri-anastomotic stricture that necessitated refashioning and (ii) a 5-cm aneurysm in a BBAVF (resulting from repeated needling for access) that required surgical intervention. There were no cases of vascular steal or wound infections. All other cases healed without complication and could be needled at the time of re-assessment (six weeks after surgery).

Discussion

The increasing number of individuals requiring HD is driving the evolution of innovative VAS methods. The BBAVF is becoming the access procedure of choice if simple native options have been exhausted. It enhances the available venous real estate to allow increased use of autologous veins for primary vascular access and avoids the potential adverse effects of prosthetic grafts. However, the anatomic inaccessibility of the BV has traditionally resulted in surgical procedures with a high prevalence of failure or cosmetically disfiguring incisions and scars in addition to significant potential morbidity.16 Reported prevalence of complications for BBAVF remains very high (≥71%).13,22,23 These complications include large haematomas necessitating surgical evacuation, seromas and wound infection, often resulting from this invasive approach.

However, these complications appear to be self-limiting. Primary patency for BBAVFs at one year of 72% (range, 23–90%) and at two years of 62% (11–86%) have been quoted.12,13 These favourable results, coupled with increasing enthusiasm for minimally invasive methods, have generated interest in novel approaches for VAS. Similar methods have been used extensively for harvesting of the saphenous vein in coronary artery bypass grafting.18,19

BBAVF formation offers excellent potential for minimally invasive approaches. There have been only two reported series of the use of minimally invasive methods for BV transposition to facilitate HD access. A study undertaken in the USA with an intention-to-treat series of 100 patients (98 successful) demonstrated excellent patency with minimal complications, but employed dissectors in the endoscopic vein and harvesting equipment.24 Similar methods have been used with minimal complications but have been associated with a poor prevalence of early maturation (71%) and, consequently, an unacceptably high prevalence of primary failure (21%) that has precluded widespread adoption.25

Our results, however, reflect excellent primary patency (96%) that compares favourably with those from traditional invasive methods.16 This factor is of paramount importance for providing timely and appropriate native vascular access to patients for HD. Our results may reflect the fact that ours was a two-stage procedure that excluded early failures, which is in keeping with the results of other studies on BBAVFs. Data suggesting use of a two-stage approach for creation of BBAVFs remain equivocal but our study suggests that it may confer a considerable advantage. Concerns regarding the potential complications of a second anastomosis, stenosis, or neo-intimal hyperplasia affecting fistula patency appeared to be unfounded at final follow-up in the present study.

Our study had several limitations inherent in a retrospective observational study. Nevertheless, it elegantly demonstrated a novel method to improve patient acceptance of an invasive modality of vascular access, and met with good patency and success. Quantifying long-term patency of these BBAVFs is crucial to ensure long-term outcomes that are comparable with more invasive methods.

There have been anecdotal reports of the use of a laryngoscope as an alternative/adjunct to facilitate exposure of the operative field in harvesting of the saphenous vein, a method that may be easily transferable to this procedure.26,27 The role and mechanism of BV use for BBAVF formation will be the subject of great interest as scholars focus on the novel and more extensive use of native veins for AVF formation. This method provides a useful alternative for BV transposition that avoids the morbidity associated with more invasive methods.

Conclusions

This study has established that a minimally invasive approach to BBAVF formation does not compromise patency. This approach ensures improvements in cosmetic results that rival those seen after formation of cephalic AVFs. This can be achieved while ensuring no compromise in preserving the excellent patency of AVFs. This strategy should allow for the continued use of BBAVFs as secondary adjuncts in preference to prosthetic grafts.

Acknowledgement

Sincere appreciation is expressed to Mr Zulfikar Pondor and Ms Lourinti Fletchman for assistance in data collection.

References

- 1.Fluck R, Kumwenda M. . Clinical Practice Guidelines: Vascular Access for Haemodialysis. London: UK Renal Association, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gilg J, Castledine C, Fogarty D, Feest T. . UK RRT Incidence in 2009: National and Centre-specific Analyses. London: UK Renal Registry, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weale AR, Bevis P, Neary WD et al. . Radiocephalic and brachiocephalic arteriovenous fistula outcomes in the elderly. J Vasc Surg 2008; : 144–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sidawy AN, Gray R, Besarab A et al. . Recommended standards for reports dealing with arteriovenous hemodialysis accesses. J Vasc Surg 2002; : 603–610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rooijens PP, Tordoir JH, Stijnen T, et al. . Radiocephalic wrist arteriovenous fistula for hemodialysis: meta-analysis indicates a high primary failure rate. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2004; : 583–589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fitzgerald JT, Schanzer A, McVicar JP, et al. . Upper arm arteriovenous fistula versus forearm looped arteriovenous graft for hemodialysis access: a comparative analysis. Ann Vasc Surg 2005; : 843–850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.NHS Blood and Transplant Organ Donation and Transplantation – Activity Figures for the UK. London: NHS England, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brescia MJ, Cimino JE, Appel K, Hurwich BJ. . Chronic hemodialysis using venipuncture and a surgically created arteriovenous fistula. N Engl J Med 1966; : 1,089–1,092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oliver MJ, McCann RL, Indridason OS, et al. . Comparison of transposed brachiobasilic fistulas to upper arm grafts and brachiocephalic fistulas. Kidney Int 2001; : 1,532–1,539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Palder SB, Kirkman RL, Whittemore AD, et al. . Vascular access for hemodialysis. Patency rates and results of revision. Ann Surg 1985; : 235–239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dagher F, Gelber R, Ramos E, Sadler J. . The use of basilic vein and brachial artery as an A-V fistula for long term hemodialysis. J Surg Res 1976; : 373–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dukkipati R, de VC, Reynolds T, Dhamija R. Outcomes of brachial artery-basilic vein fistula. Semin Dial 2011; : 220–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harper SJ, Goncalves I, Doughman T, Nicholson ML. . Arteriovenous fistula formation using transposed basilic vein: extensive single centre experience. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2008; : 237–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Matsuura JH, Rosenthal D, Clark M et al. . Transposed basilic vein versus polytetrafluorethylene for brachial-axillary arteriovenous fistulas. Am J Surg 1998; : 219–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Coburn MC, Carney WI Jr. Comparison of basilic vein and polytetrafluoroethylene for brachial arteriovenous fistula. J Vasc Surg 1994; : 896–902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kakkos SK, Haddad GK, et al. . Basilic vein transposition: what is the optimal technique? Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2010; : 612–619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dix FP, Khan Y, Al-Khaffaf H. . The brachial artery-basilic vein arterio-venous fistula in vascular access for haemodialysis – a review paper. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2006; : 70–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lumsden AB, Eaves FF III, , Ofenloch JC, Jordan WD. Subcutaneous, video-assisted saphenous vein harvest: report of the first 30 cases. Cardiovasc Surg 1996; : 771–776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Allen KB, Shaar CJ. . Endoscopic saphenous vein harvesting. Ann Thorac Surg 1997; : 265–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reynolds TS, Zayed M, Kim KM et al. . A comparison between one- and two-stage brachiobasilic arteriovenous fistulas. J Vasc Surg 2011; : 1,632–1,638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brimble KS, Rabbat C, Treleaven DJ, Ingram AJ. . Utility of ultrasonographic venous assessment prior to forearm arteriovenous fistula creation. Clin Nephrol 2002; : 122–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Taghizadeh A, Dasgupta P, Khan MS, Taylor J, Koffman G. . Long-term outcomes of brachiobasilic transposition fistula for haemodialysis. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2003; : 670–672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hossny A. . Brachiobasilic arteriovenous fistula: different surgical techniques and their effects on fistula patency and dialysis-related complications. J Vasc Surg 2003; : 821–826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Paul EM, Sideman MJ, Rhoden DH, Jennings WC. . Endoscopic basilic vein transposition for hemodialysis access. J Vasc Surg 2010; : 1,451–1,456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Veeramani M, Vyas J, Sabnis R, Desai M. . Small incision basilic vein transposition technique: a good alternative to standard method. Indian J Urol 2010; : 145–147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Goel P, Sankar NM, Rajan S, Cherian KM. . Use of direct laryngoscope for better exposure in minimally invasive saphenous vein harvesting. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2000; : 182–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ceresa F, Patane F. . Minimally invasive non-endoscopic vein harvest using a laryngoscope. A preliminary experience. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg 2010; : 312–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]