Abstract

Introduction

Enhanced recovery programmes (ERPs) have been shown to improve short-term outcomes after major colorectal surgery. Benefits of the ERP in patients who are very elderly (VE) are less well understood. We aimed to evaluate the role of the ERP in the VE population, which for the purpose of this study was defined as any patient aged 75 years or over.

Methods

A prospectively compiled database was used to identify all patients aged ≥75 years who underwent elective colorectal resection in our unit between January 2011 and September 2012. These data were analysed to study the short-term outcomes in these patients and compared with those of patients aged <75 years.

Results

Overall, 352 patients underwent elective surgery during this period; 106 were identified as VE. The median length of stay (LOS) in the VE group was 7 days (5 days in non-VE group; p=0.002). Two-thirds (62%) underwent laparoscopic surgery. The median LOS of VE patients undergoing laparoscopic surgery was 6 days (11 days for open surgery; p=0.003). A third (33%) of the VE cohort was discharged by day 5. Of these patients, 85% underwent laparoscopic surgery. There was no statistical difference in overall complication rates (VE vs non-VE).

Conclusions

Accepting that some VE patients may stay in hospital for longer, this study supports our current policy of including everyone in the ERP regardless of age. Patients undergoing laparoscopic surgery appear to benefit, with a shorter LOS. Further large scale trials are required to support the results of this study and to identify long-term outcomes.

Keywords: Enhanced recovery programme, Colorectal surgery, Elderly

The enhanced recovery programme (ERP) is now an established postoperative schedule practised in many surgical disciplines including colorectal surgery. Evidence shows that the length of hospital stay (LOS) is reduced.1–3 Data suggest that the programme costs no more than traditional postoperative care and may in fact reduce healthcare costs.4–6 Nevertheless, despite its wide acceptance, the efficacy in the very elderly (VE) population is poorly understood. Examining the evidence for the ERP in the medical literature shows that many of the cohorts are below a certain age.7,8 The aim of this study was to evaluate the role of the ERP in the VE population. There is currently a paucity of data in the medical literature on this topic specifically. On the other hand, there is an abundance of evidence advocating the ERP overall.

The majority of research supports the use of laparoscopic surgery in the elderly population.9,10 However, one Canadian research group has identified advanced age as an independent predictor of risk for postoperative complications after laparoscopic surgery.11

Reducing LOS continues to challenge surgeons, managers and policy makers, and LOS is often regarded as a marker of hospital performance and healthcare efficiency. A shorter LOS has been achieved through the use of ERPs without having any detrimental effects on patients.12,13 One South American group has reported an impressive reduction in LOS to only two days.14

There is very little in the literature in terms of negative data on ERPs. A Cochrane review from 2011 reported that ERPs are safe and effective at reducing LOS.15 One concern that is often voiced in the literature is the effect of ERPs on readmission into hospital and some centres may even be underreporting readmission rates.16 The aim of our study was to evaluate the role of the ERP in the VE population. Suitability of the ERP in this population group was based on comparing short-term outcomes with those of a non-VE cohort.

Methods

All patients undergoing elective colorectal surgery between January 2011 and September 2012 at Worcestershire Royal Hospital were included in the study. The World Health Organization (WHO) defines ‘elderly’ as anybody aged 65 years or above.17 However, there is no clearly documented definition for ‘very elderly’. For the purpose of this study, patients were categorised into two groups: VE (≥75 years) and non-VE (<75 years).

Patients were identified using a prospectively maintained electronic enhanced recovery database of patients undergoing elective colorectal surgery. The database was then cross-referenced to electronic clinic letters to maintain accuracy and quality of the data collected. The database is a continually updated catalogue that is maintained by a specialist nurse. The hospital has developed a refined version of Kehlet’s original schedule. It takes the form of a 28-page orange booklet, which is designed to replace the conventional medical and nursing clinical record. Discharge by postoperative day 5 is the hospital’s aim and standard.

Statistical analysis

Information from the database was collected and entered into Excel® (Microsoft, Redmond, WA, US). This was imported into SPSS® version 21 (IBM, New York, US) to perform data analysis. A non-parametric test (Mann–Whitney U test) was used to compare the two groups (VE vs non-VE). Outcome measures included LOS, readmission rates and complication rates. Readmission was defined as admission or unplanned attendance to hospital within 30 days of discharge.

Results

During the 21-month study period, 352 elective operations were performed although 47 operations were excluded as they did not involve excision of the large bowel or rectum. A total of 305 cases were therefore analysed in this study and 106 patients (35%) were identified as VE. The remaining 199 patients (65%) were non-VE.

The mean age was 81.0 years (standard deviation [SD]: 4.75 years) in the VE group and 60.9 years (SD: 11.53 years) in the non-VE cohort while the mean body mass index was 26.6kg/m2 (SD: 4.23kg/m2) and 27.8kg/m2 (SD: 5.54kg/m2) respectively. The vast majority (93%) of the VE patients underwent surgery for cancer compared with three-quarters (76%) of the non-VE patients. Other patient demographics are listed in Table 1. The most common operation performed overall was a right-sided colectomy. A segmental colectomy was the most common operation performed in both of the groups (75% in the VE group and 52% in the non-VE group).

Table 1.

Patient demographics

| VE (n=106) | Non-VE (n=199) | p -value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age in years | 81.0 (SD: 4.75) | 60.9 (SD: 11.53) | |

| Mean body mass index in kg/m2 | 26.6 (SD: 4.23) | 27.8 (SD: 5.54) | |

| Male | 55 (52%) | 116 (58%) | |

| Laparoscopic surgery | 66 (62%) | 119 (60%) | 0.675 |

| Laparoscopic converted to open surgery | 8 (8%) | 19 (10%) | 0.551 |

| Open surgery | 32 (30%) | 61 (30%) | 0.933 |

| Segmental colectomy | 79 (75%) | 105 (52%) | 0.000 |

| > right-sided | 54 (51%) | 61 (31%) | 0.001 |

| > left-sided | 25 (24%) | 43 (21%) | 0.770 |

| > transverse | 0 (0%) | 1 (1%) | 0.465 |

| Total colectomy | 3 (3%) | 12 (6%) | 0.219 |

| Rectal excision | 24 (23%) | 82 (41%) | 0.001 |

| > with stoma formation | 10 (41%) | 43 (52%) | 0.413 |

VE = very elderly; SD = standard deviation

Length of stay

The median LOS in the VE cohort was 7 days compared with 5 days in the non-VE group (p=0.002) (Table 2). Two-thirds (62%) of the VE patients underwent laparoscopic surgery with a conversion rate of 8%. In the non-VE cohort, a slightly smaller proportion (60%) had laparoscopic surgery with a conversion rate of 10%. Of the patients who underwent successful laparoscopic surgery in the VE group, the median LOS was 6 days compared with 11 days for VE patients undergoing open surgery (p=0.000). In the non-VE group, the median LOS was 5 days for laparoscopic surgery and 7 days for open surgery (p=0.000).

Table 2.

Length of stay

| VE (n=106) | Non-VE (n=199) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median LOS | 7 days | 5 days | 0.002 |

| Median LOS for laparoscopic surgery | 6 days | 5 days | 0.008 |

| Median LOS for open surgery (including conversions) | 11 days | 7 days | 0.003 |

| Discharged by day 5 | 35 (33%) | 108 (54%) | 0.485 |

| Number of bed days lost* | 18 | 7 | 0.018 |

LOS = length of stay; VE = very elderly

*ie patient not discharged on same day as deemed medically suitable

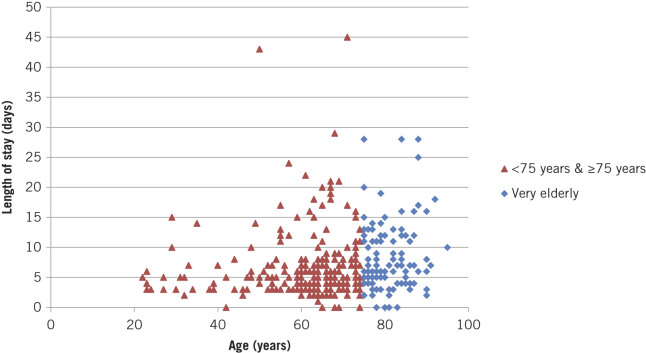

A third (33%) of the VE patients were discharged by day 5 compared with more than half (54%) of the non-VE cohort. Eighty-five per cent of the VE patients discharged by day 5 underwent laparoscopic surgery. Ninety-eight per cent of patients in the non-VE group were discharged from hospital on the same day they were deemed medically fit (7 bed days lost). Only 93% of VE patients were discharged on time (18 bed days lost). The difference in bed days lost was statistically significant (p=0.018). Overall comparison of age versus LOS is demonstrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Patient age versus length of stay

Complications

The most common postoperative complication across both cohorts was ileus (Table 3). Complication rates were relatively equal between the two groups with no statistical difference being identified (p=0.184). The VE patients had a slightly higher rate of respiratory complications and this is likely to reflect their reduced lung function as a group. This difference, however, was not statistically significant (p=0.184).

Table 3.

Complications

| VE (n=106) | Non-VE (n=199) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 43 (40.6%) | 95 (47.7%) | 0.065 |

| Cardiac problems | 5 (4.7%) | 1 (0.5%) | 0.012 |

| Postoperative ileus | 26 (24.5%) | 36 (18.1%) | 0.184 |

| Respiratory problems | 5 (4.7%) | 4 (2.0%) | 0.184 |

| Anastomotic leak | 1 (0.9%) | 6 (3.0%) | 0.251 |

| Venous thromboembolism | 0 (0%) | 1 (0.5%) | 0.465 |

| Wound infection | 6 (5.7%) | 8 (4.0%) | 0.515 |

| Death (within 30 days) | 0 (0%) | 3 (1.5%) | 0.205 |

VE = very elderly

There was a significant difference in postoperative cardiac problems between the two groups (p=0.012). Unsurprisingly, the VE patients suffered with more cardiac complications postoperatively. There were no deaths within 30 days of surgery in the VE cohort. Conversely, three deaths occurred among the non-VE patients.

Readmissions

Ten per cent of patients (n=19) from the non-VE group were readmitted to hospital within 30 days after discharge compared with seven per cent (n=8) of the VE patients. Despite fewer readmissions in the VE cohort, the difference was not statistically significant (p=0.470). The median LOS at readmission was 4.5 days in the VE group and 5.5 days in the non-VE group. The most common cause for readmission in both cohorts was wound infection. Other reasons are identified in Table 4.

Table 4.

Reasons for readmission

| VE (n=106) | Non-VE (n=199) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Readmissions (within 30 days) | 8 (7%) | 19 (10%) | 0.470 |

| Wound infection / breakdown | 3 | 7 | |

| Pain | 2 | 5 | |

| Anastomotic leak | 0 | 2 | |

| Intra-abdominal collection | 0 | 2 | |

| Urinary tract infection / retention | 1 | 1 | |

| Dehydration | 1 | 0 | |

| Stroke | 1 | 0 | |

| Constipation | 0 | 1 | |

| Other | 0 | 1 |

VE = very elderly

Discussion

In the UK, there are currently 3 million people over 80 years of age and this is projected to rise to 8 million by 2050.18 Longevity of the ageing population is likely to increase and with this rise, major abdominal surgery is likely to be performed more frequently. Over 30% of the patients undergoing major abdominal surgery from our database were aged over 75 years and one can only assume that this figure will continue to increase.

VE patients present to the medical profession with a unique challenge; they are more likely to require surgical intervention than the younger population, and yet they are also more likely to have complex medical conditions and poor cardiorespiratory reserve so they are not the fittest candidates for major surgery.19 Morbidity in this population group following surgery remains high, which is perhaps why there is sometimes reluctance in offering major surgery.20 It has been long established that mortality in the VE population undergoing emergency major abdominal surgery remains high despite advances in perioperative monitoring.21

Laparoscopic colorectal surgery for elderly patients improves short-term outcomes compared with open surgery. Evidence already exists that patients are likely to have a shorter LOS, require less intensive care and have lower complication rates.9,10,22,23 The results from our study confirm and strengthen the existing evidence for laparoscopic surgery. Many of the patients in the VE cohort were reaping the same benefits of ERP as non-VE patients. This study showed no statistical difference in readmission rates or overall complication rates between VE and non-VE groups. When the types of complications were categorised, the results revealed a significantly increased rate of postoperative cardiac problems for the VE cohort (4.7%). This rate is comparable with published data.24

There were no deaths in the VE group. Although three deaths occurred in the non-VE cohort, there was no statistical difference between the mortality rates. On the other hand, there was a significant difference in median LOS for the VE and non-VE groups (7 vs 5 days respectively). The median LOS was reduced to 6 days for VE patients undergoing laparoscopic surgery. We believe it is not unreasonable to accept that VE patients may need to stay in hospital for one day more than their younger counterparts.

In terms of LOS, the results for the VE group from our study are in line with those from other studies, for which the LOS varied between 7 and 10 days.25,26 Readmission rates, on the other hand, are not often reported. LOS can be regarded as a performance marker and has been described as ‘an effective and simple method of measuring the quality of care’.26 Nevertheless, LOS measurements without reporting potentially high readmission rates may actually indicate poor standards of care.

Readmission rates in our study were higher in the non-VE group (10% vs 7%). A similar pattern has been described in the literature.24 There was, however, no statistical difference in readmission rates between the two cohorts.

One should take into consideration that the postoperative requirements for patients in the VE group differ greatly to those of other patients. Discharge for VE patients may be complex and involve arranging community services such as nursing, physiotherapy and transportation. If these services are not in place by the time the patient is medically fit, discharge is likely to be delayed. This is potentially why 7% of VE patients in our study were not discharged on the same day they were deemed medically suitable for discharge. The number of bed days lost as a consequence totalled 18 in the VE group, a significant difference compared with the non-VE cohort (7 bed days) (p=0.018).

Study limitations

There are a number of limitations to this study, which undoubtedly affected the results. The cohorts were not case-matched. The group sizes varied considerably and the default position was to enrol every patient on to the ERP as opposed to randomly allocating them to traditional care or the ERP. This would have required a prospective study design and although this would have yielded a higher quality of data than using a retrospective approach, study numbers would have been far smaller. This may also have required approval by an ethics committee prior to starting the study.

The VE group consisted of patients aged 75 years or older. Verbal feedback from senior surgeons identified that the threshold could have been set at 80 years as 75 years may not represent the VE population adequately. Owing to the fact that no universally accepted definition of ‘very elderly’ exists, setting a minimum age for the VE cohort was based on the WHO criteria for ‘elderly’ and the observations of this population group in the published literature.17,23,27,28

Although the data were collated from a single unit, it was not a single surgeon study. During the study period, a total of five surgeons with varied experience operated on the patients.

Adherence to the ERP was not measured formally. This could have been arranged if the study design was prospective.

Conclusions

The ERP is a safe postoperative rehabilitation programme that can be deployed for an elderly population. This study has demonstrated that overall complication rates remain similar between VE and non-VE patients. When an ERP is combined with laparoscopic surgery, VE patients will benefit from a shorter LOS without a significant impact on readmission rates. Healthcare organisations will indirectly benefit from this also but should accept that VE patients may stay in hospital on average for one extra day compared with non-VE patients. Reallocation of resources to ensure discharge planning is efficient and that patients are discharged on the same day may also reduce LOS for this group of patients. Larger studies are required to provide a more robust evidence base.

References

- 1.Clinical Outcomes of Surgical Therapy Study Group A comparison of laparoscopically assisted and open colectomy for colon cancer. N Engl J Med 2004; : 2,050–2,059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wind J, Polle SW, Fung Kon Jin PH et al. . Systematic review of enhanced recovery programmes in colonic surgery. Br J Surg 2006; : 800–809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hemandas AK, Abdelrahman T, Flashman KG et al. . Laparoscopic colorectal surgery produces better outcomes for high risk cancer patients compared to open surgery. Ann Surg 2010; : 84–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kehlet H, Wilmore DW. Multimodal strategies to improve surgical outcome. Am J Surg 2002; : 630–641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.King PM, Blazeby JM, Ewings P et al. . Randomized clinical trial comparing laparoscopic and open surgery for colorectal cancer within an enhanced recovery programme. Br J Surg 2006; : 300–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lassen K, Soop M, Nygren J et al. . Consensus review of optimal perioperative care in colorectal surgery. Arch Surg 2009; : 961–969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Teeuwen PH, Bleichrodt RP, Strik C et al. . Enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) versus conventional postoperative care in colorectal surgery. J Gastrointest Surg 2010; : 88–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gillissen F, Hoff C, Maessen JM et al. . Structured synchronous implementation of an enhanced recovery program in elective colonic surgery in 33 hospitals in the Netherlands. World J Surg 2013; : 1,082–1,093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schwandner O, Schiedeck TH, Bruch HP. Advanced age – indication or contraindication for laparoscopic colorectal surgery? Dis Colon Rectum 1999; : 356–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Seshadri PA, Mamazza J, Schlachta CM et al. . Laparoscopic colorectal resection in octogenarians. Surg Endosc 2001; : 802–805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schlachta CM, Mamazza J, Seshadri PA et al. . Determinants of outcomes in laparoscopic colorectal surgery: a multiple regression analysis of 416 resections. Surg Endosc 2000; : 258–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lv L, Shao YF, Zhou YB. The enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) pathway for patients undergoing colorectal surgery: an update of meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Int J Colorectal Dis 2012; : 1,549–1,554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gustafsson UO, Scott MJ, Schwenk W et al. . Guidelines for perioperative care in elective colonic surgery: Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS®) Society recommendations. World J Surg 2013; : 259–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rossi G, Vaccarezza H, Vaccaro CA et al. . Two-day hospital stay after laparoscopic colorectal surgery under an enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) pathway. World J Surg 2013; : 2,483–2,489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Spanjersberg WR, Reurings J, Keus F, van Laarhoven CJ. Fast track surgery versus conventional recovery strategies for colorectal surgery. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011; : CD007635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schneider EB, Hyder O, Brooke BS et al. . Patient readmission and mortality after colorectal surgery for colon cancer: impact of length of stay relative to other clinical factors. J Am Coll Surg 2012; : 390–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Definition of an Older or Elderly Person. World Health Organization http://www.who.int/healthinfo/survey/ageingdefnolder/ (cited September 2015).

- 18.Cracknell R. The Ageing Population Mellows-Facer A. Key Issues for the New Parliament 2010. London: House of Commons Library; 2010. pp44–45. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bàllesta López C, Cid JA, Poves I et al. . Laparoscopic surgery in the elderly patient. Surg Endosc 2003; : 333–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pedersen T, Eliasen K, Henriksen E. A prospective study of mortality associated with anaesthesia and surgery: risk indicators of mortality in hospital. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 1990; : 176–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Turrentine FE, Wang H, Simpson VB, Jones RS. Surgical risk factors, morbidity, and mortality in elderly patients. J Am Coll Surg 2006; : 865–877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mutch MG. Laparoscopic colectomy in the elderly: when is too old? Clin Colon Rectal Surg 2006; : 33–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grailey K, Markar SR, Karthikesalingam A et al. . Laparoscopic versus open colorectal resection in the elderly population. Surg Endosc 2013; : 19–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Senagore AJ, Madbouly KM, Fazio VW et al. . Advantages of laparoscopic colectomy in older patients. Arch Surg 2003; : 252–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vignali A, Di Palo S, Tamburini A et al. . Laparoscopic vs open colectomies in octogenarians: a case-matched control study. Dis Colon Rectum 2005; : 2,070–2,075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Raymond TM, Dastur JK, Khot UP. Hospital stay and return to full activity following laparoscopic colorectal surgery. JSLS 2008; : 143–149. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Poon RT, Law WL, Chu KW, Wong J. Emergency resection and primary anastomosis for left-sided obstructing colorectal carcinoma in the elderly. Br J Surg 1998; : 1,539–1,542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Keller DS, Lawrence JK, Nobel T, Delaney CP. Optimizing cost and short-term outcomes for elderly patients in laparoscopic colonic surgery. Surg Endosc 2013; : 4,463–4,468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]