Abstract

Introduction

Bone, native joint and soft tissue infections are frequently referred to orthopaedic units although their volume as a proportion of the total emergency workload has not been reported previously. Geographic and socioeconomic variation may influence their presentation. The aim of this study was to quantify the burden of such infections on the orthopaedic department in an inner city hospital, determine patient demographics and associated risk factors, and review our current utilisation of specialist services.

Methods

All cases involving bone, native joint and soft tissue infections admitted under or referred to the orthopaedic team throughout 2012 were reviewed retrospectively. Prosthetic joint infections were excluded.

Results

Almost 15% of emergency admissions and referrals were associated with bone, native joint or soft tissue infection or suspected infection. The cohort consisted of 169 patients with a mean age of 43 years (range: 1–91 years). The most common diagnosis was cellulitis/other soft tissue infection and the mean length of stay was 13 days. Two-thirds of patients (n=112, 66%) underwent an operation. Fifteen per cent of patients were carrying at least one blood borne virus, eleven per cent were alcohol dependent, fifteen per cent were using or had been using intravenous drugs and nine per cent were homeless or vulnerably housed.

Conclusions

This study has shown that a significant number of patients are admitted for orthopaedic care as a result of infection. These patients are relatively young, with multiple complex medical and social co-morbidities, and a long length of stay.

Keywords: Infection, Psychosocial deprivation, Urban hospitals, Orthopaedics, Infectious diseases, Interdisciplinary communication

Infections in bone and joints can have devastating long-term consequences resulting in extensive inpatient investigation, multiple operations, prolonged antibiotic courses, and inpatient and community rehabilitation. This leads to increased direct costs for the healthcare provider and decreased earnings for the patient. While there are variations between trusts and units, the financial cost of infection in total hip and total knee arthroplasty averages £70,000 per patient.1

The prevention, diagnosis and treatment of periprosthetic joint infections along with their impact on orthopaedic resources and society remain some of the most closely studied subjects for the orthopaedic community worldwide.2–4 The focus of study tends to be pathogen, site or risk factor specific, such as the use of intravenous drugs.5–7 Such infections can be a regular source of emergency referral or admission to specialist units and may require a variety of interventions ranging from the administration of antibiotics to extensive surgical procedures.8,9 However, beyond this group of infections, there is also a burden of bone, native joint and soft tissue infection, in which prevalence, patient demographics and risk factors have often only been studied in isolation. A holistic capture of data on such a group of patients receiving treatment in an orthopaedic unit has not, to our knowledge, been undertaken previously.

In 2012–2013, 121,049 patients were seen in the emergency department of our institution. The hospital serves the London boroughs of Camden and Islington, representing some of the most deprived areas in London for homelessness and inequality in life expectancy.10 The catchment area is estimated to cover a population of 410,000 patients. The complexity of the patient demographic has led to the development of a local network of specialist services aimed at improving the health of patients who are homeless, patients with addiction, patients with blood borne viruses, and facilitating reduced admission rates and early discharge, with significant rates of success.11 Nevertheless, we believe that our inner city location and patient population lead to a disproportionate pattern of emergency referrals and admissions under our teams in trauma and orthopaedics.

Similar observations have been reported in a specific cohort of necrotising soft tissue infections in a metropolitan UK population.12 Variation in patient and disease characteristics attributable to the metropolitan nature of their catchment area compared with other countries and more rural settings means that certain diagnostic scoring systems designed with non-UK datasets should be used with caution.

The primary aim of this study was therefore to quantify the burden of bone, native joint and soft tissue infection in terms of referral and emergency admissions to our unit. The study also sought to determine the patient demographics, co-morbidities and utilisation of specialist services during the treatment of such patients.

Methods

A prospectively collected database was reviewed for all admissions under the trauma team in our unit during 2012. The recorded patient details, diagnosis, investigations and results, management plans, length of stay and discharge details were collated. Any patients referred to or admitted under the on-call trauma and orthopaedic team with a query of bone, native joint or soft tissue infection were included in the study. Prosthetic joint infections were excluded as their care is provided by our specialist arthroplasty service and periprosthetic infections were not a feature in our study. Similarly, diabetic foot ulcers and infections were excluded as these are managed by a dedicated diabetic foot multidisciplinary team (MDT), of which the senior author is a member. Demographic data included age, sex, home postcode and ethnicity, as recorded on our hospital database. Those patients without a home address were classified as having no fixed abode.

Diagnosis of infection was made where a patient presented with local or systemic symptoms and signs, responded to appropriate medical and surgical management, and/or had positive microbiological specimens on laboratory records. Final diagnoses were grouped into categories including abscesses, septic arthritis, osteomyelitis, necrotising fasciitis, cellulitis, infected wounds, infected ulcers, infected haematomas, infected cysts, infected metalwork, tropical infections and animal or human bites. Cases were also recorded if they were referred for suspected infection and the final diagnosis included inflammatory arthropathy, combined pathologies or was unknown. Involvement of the relevant MDT members was ascertained by an explicit reference to their role in the computerised discharge summary. Co-morbidities, including alcohol and drug use, were ascertained from medical and laboratory records. Local statistical data and geographic indices of social deprivation were obtained from Camden Council and Trust for London.

Results

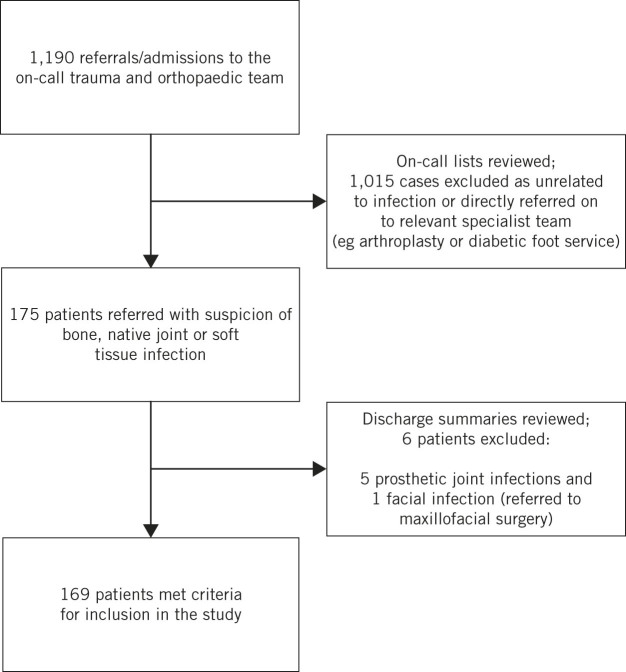

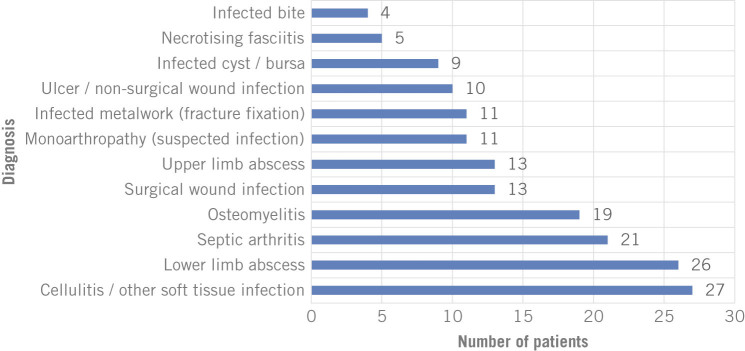

Out of 1,190 emergency admissions and referrals to the department during the study period, 169 patients (15%) fulfilled the inclusion criteria of having a suspected bone, native joint or soft tissue infection (Fig 1). The mean age at admission was 43 years (range: 1–91 years) with a male-to-female ratio of 1.4:1. The final diagnoses at point of discharge are demonstrated in Figure 2. The most common diagnoses were cellulitis, abscesses, septic arthritis and osteomyelitis.

Figure 1.

The inclusion and exclusion criteria for this study

Figure 2.

The final diagnoses as documented at time of discharge

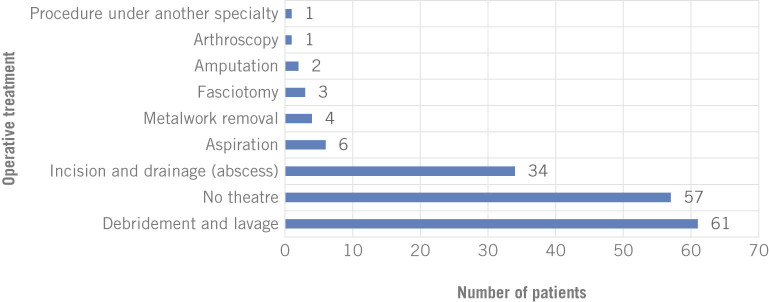

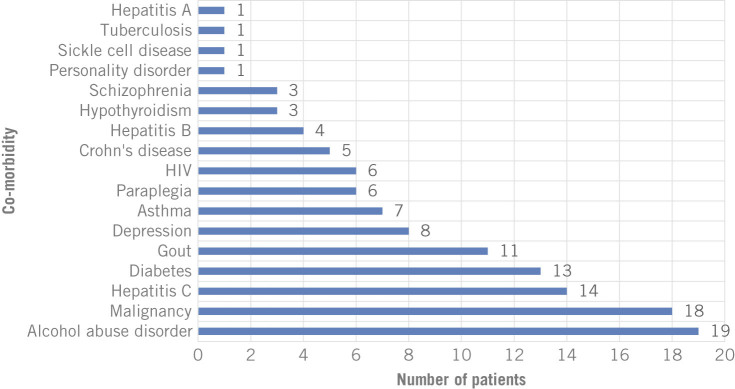

Figure 3 shows the operative interventions required. One hundred and twelve patients (66%) required operative management. The mean length of hospital stay was 13 days. The maximum length of stay was 122 days and 5 patients were admitted to hospital for more than 100 days. Two of those patients were dependent on alcohol and intravenous drugs. In the whole study group, 26 patients (15%) were documented as currently using or having previously used intravenous drugs. Fifteen (9%) were receiving methadone prescriptions. Thirty-one patients (18%) had a psychiatric diagnosis, which included alcohol abuse disorder. The range of co-morbidities is shown in Figure 4.

Figure 3.

The operations carried out as well as the number of those managed non-operatively

Figure 4.

The range of co-morbidities

Ten patients (6%) were of no fixed abode. Five (3%) were living in a hostel designated to support individuals without a home. Sixty-five patients (38%) lived in the catchment area of the hospital while forty-eight (28%) lived in other London boroughs. Fifteen patients (9%) lived in other areas of the UK and nine (5%) lived abroad.

Two patients (1%) received input from the specialist drug and alcohol liaison team, and one patient (1%) was seen by the specialist homeless team. The specialist infectious diseases physicians saw 26 (15%) of the patients and 17 patients (10%) had input from a microbiologist.

Discussion

This study examined the burden of bone, native joint and soft tissue infection on orthopaedic emergency referrals and admissions, taking a holistic approach to assess the complex medical and social needs of these patients as well as how we currently use specialist services to meet these needs and improve overall care. This group of patients accounted for 15% of all emergency admissions or referrals. This is equivalent to one full day of admissions per week at our unit. The needs of this cohort of patients can vary considerably from those of many other trauma patients.

A wide variety of infection related diagnoses was encountered, the most common being cellulitis and lower limb abscesses, which is similar to other studies looking at infections in intravenous drug users.7,13,14 Despite the wide variety and significant proportion of infection related admissions, however, only 112 (66%) of these patients required operative management, which raises the question of whether a surgical team should lead patient care in almost a third of these cases.

Levell et al reported that their dermatology-led cellulitis clinic for secondary care emergency admissions resulted in improved accuracy in initial diagnosis, increased diagnosis of other underlying skin conditions and increased savings in treating cellulitis.15 As with fragility fracture care, where access to an orthogeriatrician is recognised to be best practice with improved care of a high risk and vulnerable patient group, so the care of patients with infection should have access to other specialties.16 Copley et al showed that by instigating a multidisciplinary approach to the care of children with osteomyelitis, including infectious disease specialists, there was a significant decrease in length of stay, readmission rates and the number of antibiotic changes during treatment.17

In 2012 our institution did not have a policy or formalised multidisciplinary approach to native orthopaedic infection. An infectious diseases or microbiology specialist opinion required formal referral from a member of the admitting team. It may be that our low rate of referral and multidisciplinary care plans reflects this as junior doctors involved in receiving referrals from the emergency department may not have been aware of the team of infectious disease specialists, which is not present in many hospitals, or they may not have considered the referral necessary. Given the clear benefit shown with a multidisciplinary approach and the significant proportion of cases that can be successfully managed non-operatively, it may be appropriate to initiate an automatic process of referral in cases of bone, native joint or soft tissue infection, or at least inclusion in a regular MDT meeting.

This cohort of patients was, in the main, of working age with a mean age of 43 years. A lengthy hospital stay and any long-term consequences of infection will have significant financial costs for the patient. Many forms of state support are stopped or decreased when a patient is admitted to hospital and unemployment rises.18 In inner London in 2011, of those whose day-to-day activities were significantly limited, 79% were unemployed and 75% were economically inactive.10

The average length of stay (13 days) far exceeds the figures quoted for some of the most frequently performed elective orthopaedic procedures (6.9 days after primary hip replacement and 6.6 days after primary knee replacement).19 For some patients, this was due to the severity of their infection and subsequent prolonged hospitalisation for treatment. However, for others, there were complicated social matters. For example, two of our patients with prolonged hospital stay required long-term intravenous antibiotics but could not be discharged with a central line to receive their treatment at home because of a history of intravenous drug use (IVDU). There was also a significant proportion of homeless people and individuals who were vulnerably housed (9%). These patients must be provided with safe and appropriate housing before they can be discharged, a process that is invariably challenging and time consuming.

Prolonged length of stay is an independent variable in the overall cost of healthcare.20 It is associated with both additional financial costs and a negative effect on the availability of resources for the management of other pathologies.21

When dealing with a group as diverse as the one in this study, addressing the issues behind the prolonged length of stay is unlikely to be successful with a single intervention. Outpatient administration of intravenous antibiotics, MDT involvement during hospitalisation and when planning discharge, and contribution by specialist teams in patients with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), hepatitis, homelessness and alcohol abuse disorder are some of the interventions that have been proven to help reduce the in-hospital burden from severe infections.11,17 Involving doctors with infectious disease and microbiological training decreases the length of antibiotic administration as well as the antibiotic cost per admission, which Coello et al found to be the second largest contributor to cost in treating hospital patients with infection.20

Although 33% of patients in the cohort had no co-morbidities, it was common for patients to have one or multiple recognised risk factors for infection. The large burden of psychiatric illness was particularly evident, with 18% having a psychiatric diagnosis, the most common being alcohol abuse disorder. Furthermore, this percentage is likely to be an underestimate as this information would only have been included in the hospital documents used in this study for patients who openly admitted to psychiatric illness, alcohol and drug abuse. Studies of the adverse psychiatric effects of infection on patients in hospital have focused on isolation and loneliness, experience from infection control precautions and its negative psychological effects on patients.22

The phenomenon of drug abuse and its repercussions on non-orthopaedic specialist services has been studied previously.7,8,13 Orthopaedic units have also reported their experience treating the sequelae of drug abuse. Henriksen et al treated 89 IVDU patients during 145 hospitalisations focusing on soft tissue sequelae, with 58 superficial abscesses, 27 deep abscesses and 57 cases of cellulitis accounting for the majority of their workload.14 They concluded that best practice should involve antimicrobials, microbiological analysis and surgical exploration, and revision was to be followed by active wound care.

More recently, Allison et al reported on the microbiology of orthopaedic related infections secondary to drug abuse.23 They reviewed 215 patients over 7 years, and found a high incidence of osteomyelitis (59%) and a predominance of Gram positive bacteria. Wang et al compared the demographics, presentation, treatment and outcomes of surgically treated primary pyogenic infections of the spine between IVDU and non-IVDU patients.9 The IVDU group required more complex surgical management, had a higher incidence of surgical site infections, and were found to be unreliable during treatment and the follow-up period.

Reviewing the IVDU subgroup of patients in isolation was beyond the scope of this study. Nevertheless, our experience of the challenges in the overall management of these patients, including their complex presentation, co-morbidities and social circumstances, is mirrored closely by the reports from other units.

There were no new cases of diabetes, HIV, hepatitis or tuberculosis in our study cohort. In a region in which the prevalence of each of these is higher than the national average, this is a surprising result.24–26 Story et al showed that homeless people, prisoners and problem drug users collectively comprise 17% of London’s tuberculosis cases.27 The prevalence in London is 27 per 100,000 population. Among the homeless population it is 788 per 100,000 and for problem drug users, it is 354 per 100,000.

Our lack of new diagnoses in a such a high risk cohort of this size, together with low rates of referral to infectious disease specialists, would suggest that treatment was prioritised over investigating for immunodeficiency; further postgraduate education as well as close teamwork with infectious disease and diabetes specialists will benefit patient outcome. Consideration should therefore be given to developing a policy to investigate for blood borne viruses and causes of immunodeficiency in patients with infection in bone, native joints and soft tissue in the future.

In London there are estimated to be 10,000 single homeless people living on the streets or in hostels.27 Homeless patients are admitted 3.2 times as often as those who are not homeless.11 Patients with no home were also overrepresented in our study. Engaging specifically in issues surrounding homelessness has been shown to decrease the total number of bed days, decrease rates of readmission, improve discharge planning and decrease total cost.11

Study limitations

There are some limitations to this study. It relies on our prospectively collected data, electronic records and discharge summaries. We did not have access to the hospital notes and appreciate that there may have been evidence for documented consultations that were not registered in our dataset. The retrospective review of the data is a potential source for inaccuracies, in terms of both the actual prevalence of the problem and the relevant demographic characteristics. Our perception is that the reported prevalence may be an underestimate due to some of the referrals being documented incorrectly in the initial electronic records. Nevertheless, our data highlights the disproportionate burden on our cohort of admissions.

Furthermore, the findings of this study are a reflection of the local population. As a result, the relatively high number of IVDU, alcohol dependent and HIV/hepatitis positive patients may not be representative of other parts of the country, with the overall burden of bone, native joint and soft tissue infection smaller than that reported here.

Conclusions

This study demonstrates that infections of bone, native joint and soft tissue are a frequent cause for referral and admission to an orthopaedic unit. The patient characteristics can be an added source of increasing complexity during the treatment. Engagement of other relevant services, both medical and social, might prove crucial in reducing the overall burden on the orthopaedic specialists.

References

- 1.Briggs TW. Getting It Right First Time. Stanmore: TWR Briggs; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berbari E, Mabry T, Tsaras G et al. Inflammatory blood laboratory levels as markers of prosthetic joint infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2010; : 2,102–2,109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vanhegan IS, Morgan-Jones R, Barrett DS, Haddad FS. Developing a strategy to treat established infection in total knee replacement: a review of the latest evidence and clinical practice. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2012; : 875–881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kapadia BH, McElroy MJ, Issa K et al. The economic impact of periprosthetic infections following total knee arthroplasty at a specialized tertiary-care center. J Arthroplasty 2014; : 929–932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vardakas KZ, Kontopidis I, Gkegkes ID et al. Incidence, characteristics, and outcomes of patients with bone and joint infections due to community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: a systematic review. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2013; : 711–721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Termaat MF, Raijmakers PG, Scholten HJ et al. The accuracy of diagnostic imaging for the assessment of chronic osteomyelitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2005; : 2,464–2,471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marks M, Pollock E, Armstrong M et al. Needles and the damage done: reasons for admission and financial costs associated with injecting drug use in a Central London Teaching Hospital. J Infect 2013; : 95–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Takahashi TA, Baernstein A, Binswanger I et al. Predictors of hospitalization for injection drug users seeking care for soft tissue infections. J Gen Intern Med 2007; : 382–388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang Z, Lenehan B, Itshayek E et al. Primary pyogenic infection of the spine in intravenous drug users: a prospective observational study. Spine 2012; : 685–692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Trust for London London’s Poverty Profile 2013. London: Trust for London; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hewett N, Halligan A, Boyce T. A general practitioner and nurse led approach to improving hospital care for homeless people. BMJ 2012; : e5999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Glass GE, Sheil F, Ruston JC, Butler PE. Necrotising soft tissue infection in a UK metropolitan population. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 2015; : 46–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hope V, Kimber J, Vickerman P et al. Frequency, factors and costs associated with injection site infections: findings from a national multi-site survey of injecting drug users in England. BMC Infect Dis 2008; : 120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Henriksen BM, Albrektsen SB, Simper LB, Gutschik E. Soft tissue infections from drug abuse. A clinical and microbiological review of 145 cases. Acta Orthop Scand 1994; : 625–628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Levell NJ, Wingfield CG, Garioch JJ. Severe lower limb cellulitis is best diagnosed by dermatologists and managed with shared care between primary and secondary care. Br J Dermatol 2011; : 1,326–1,328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.British Orthopaedic Association The Care of Patients with Fragility Fracture. London: BOA; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Copley LA, Kinsler MA, Gheen T et al. The impact of evidence-based clinical practice guidelines applied by a multidisciplinary team for the care of children with osteomyelitis. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2013; : 686–693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Change of Circumstances: Hospital Admission. NI Direct http://www.nidirect.gov.uk/change-of-circumstances-hospital-admission (cited September 2015).

- 19.National Joint Registry for England and Wales 7th Annual Report 2010. Hemel Hempstead: NJR; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Coello R, Glenister H, Fereres J et al. The cost of infection in surgical patients: a case-control study. J Hosp Infect 1993; : 239–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bozic KJ, Ries MD. The impact of infection after total hip arthroplasty on hospital and surgeon resource utilization. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2005; : 1,746–1,751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Morgan DJ, Diekema DJ, Sepkowitz K, Perencevich EN. Adverse outcomes associated with Contact Precautions: a review of the literature. Am J Infect Control 2009; : 85–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Allison DC, Holtom PD, Patzakis MJ, Zalavras CG. Microbiology of bone and joint infections in injecting drug abusers. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2010; : 2,107– 2,112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Public Health England Tuberculosis in the UK: 2013 Report. London: PHE; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Public Health England HIV in the UK: 2013 Report. London: PHE; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Public Health England Hepatitis C in the UK: 2013 Report. London: PHE; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Story A, Murad S, Roberts W et al. Tuberculosis in London: the importance of homelessness, problem drug use and prison. Thorax 2007; : 667–671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]