Abstract

Background

Premature rupture of membranes and preterm delivery are associated with Ureaplasma infection. We hypothesized that Ureaplasma induced extracellular collagen fragmentation results in production of the tripeptide PGP (proline-glycine-proline), a neutrophil chemoattractant. PGP release from collagen requires matrix metalloproteases (MMP-8/MMP-9) along with a serine protease, prolyl endopeptidase (PE).

Methods

Ureaplasma culture negative amniotic fluid (indicated preterm birth, n=8; spontaneous preterm birth, n=8) and Ureaplasma positive amniotic fluid (spontaneous preterm birth, n=8) were analyzed by electro-spray ionization-liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry for PGP, and for MMP-9 by zymography. PE was evaluated in lysates of U. parvum serovar 3 (Up3) and U. urealyticum serovar 10 (Uu10) by western blotting and activity assay.

Results

PGP and MMP-9 were increased in amniotic fluid from spontaneous preterm birth with positive Ureaplasma cultures, but not with indicated preterm birth or spontaneous preterm birth with negative Ureaplasma cultures. Human neutrophils co-cultured with Ureaplasma strains showed increased MMP-9 activity. PE presence and activity were noted with both Ureaplasma strains.

Conclusions

Ureaplasma spp. carry the protease necessary for PGP release, and PGP and MMP-9 are increased in amniotic fluid during Ureaplasma infection, suggesting Ureaplasma spp. induced collagen fragmentation contributes to preterm rupture of membranes and neutrophil influx causing chorioamnionitis.

Introduction

Preterm delivery is an important health care concern, accounting for more than half of perinatal mortality and long-term morbidity1. Intrauterine infection is often associated with preterm delivery1 and combined clinical and histologic chorioamnionitis is noted in 40–70% of preterm births with either preterm premature rupture of membranes (PPROM) or spontaneous preterm labor (SPTL)2,3. While chorioamnionitis is often polymicrobial, the genital mycoplasmas Ureaplasma parvum (Up) or Ureaplasma urealyticum (Uu) are the most frequently isolated microbes occurring in almost half the cases of culture-confirmed chorioamnionitis2,4, and are strongly associated with PPROM and prematurity5,6. In a non-human primate (NHP) model, it has been shown that Up as the sole pathogen elicits a robust proinflammatory response and leads to preterm labor7. A critical barrier to the field is that it is not clear how Ureaplasma spp. (Up/Uu) induce chorioamnionitis and initiate PPROM or spontaneous preterm labor. Previous studies evaluating variation of the MB antigen8, hemolysins4 urease9, IgA1 protease4 or phospholipases A and C4 have not led to major insights into pathophysiology, and the use of antimicrobial agents has not reduced preterm birth2,10, 11.

Ureaplasma spp. infections associated with spontaneous preterm labor are characterized by neutrophil influx, with remodeling of extracellular matrix (especially type IV collagen) in the fetal membranes. Recent evidence from our group has demonstrated a novel mechanism of neutrophil influx through extracellular fragmentation of collagen, producing the tripeptide PGP that induces chemotaxis of polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMNs)12. PGP activates CXC receptors on PMNs due to a structural homology with ELR+ chemokines, such as IL-8. Using electro-spray ionization-liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (ESI-LC MS/MS), we have detected PGP in human diseases such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and cystic fibrosis (CF)10,13, 14. The mechanism for PGP release from collagen involves the coordinated efforts of MMPs (specifically, MMP-8 and MMP-9) along with a serine protease, prolyl endopeptidase (PE). In addition, human neutrophils contain PE, which is constitutively active, and can generate PGP de novo from collagen after activation with LPS12. It has been shown that neutrophils activated by cigarette smoke extract can breakdown collagen into acetylated PGP (Nac-PGP) and that this collagen fragment itself can activate neutrophils, which may lead in vivo to a self-propagating cycle of neutrophil infiltration, chronic inflammation and lung emphysema15. More recently, it has also been found that the loss of the PGP degrading enzyme - leukotriene A4 hydrolase (LTA4H), leads to sustained and pronounced pulmonary inflammation due to acute infection16.

We tested the hypothesis that Ureaplasma spp. (Up/Uu) infection leads to release of PGP and MMP-9, which would potentially lead to neutrophil accumulation and be associated with an increased risk of PROM, due to collagen fragmentation.

Results

Analysis of PGP

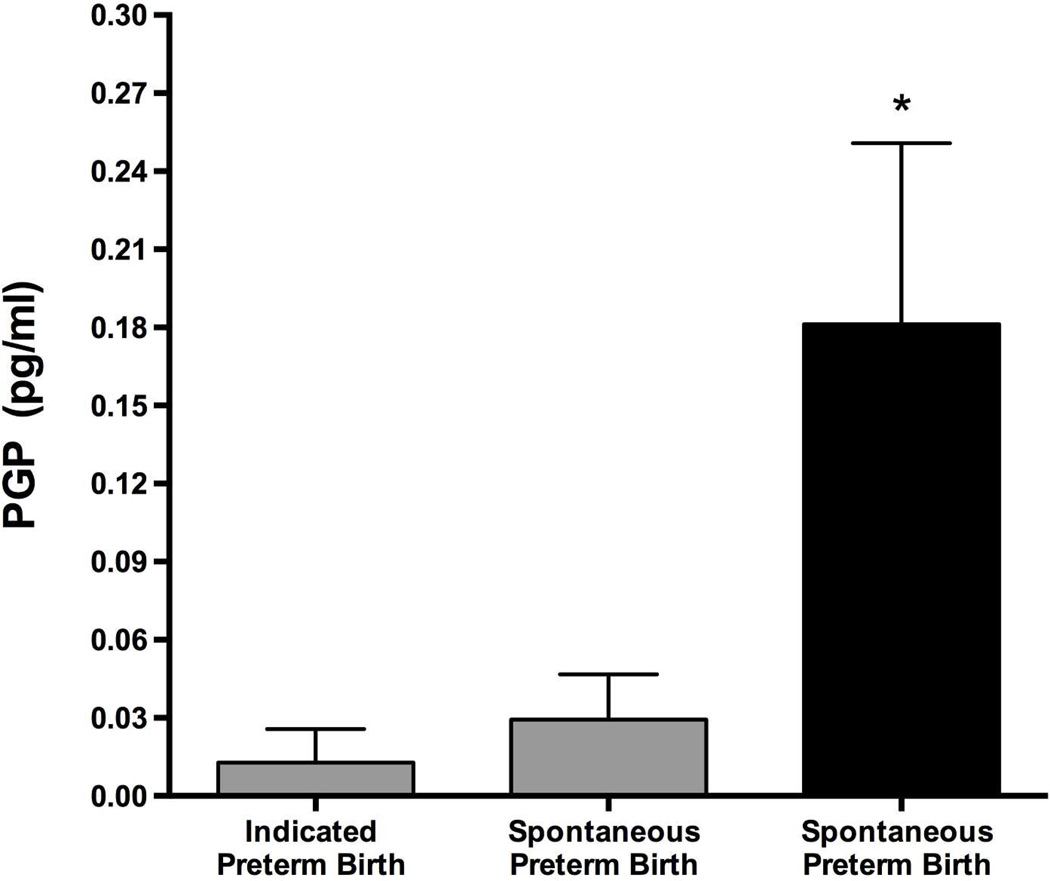

PGP was elevated only in amniotic fluid of spontaneous preterm labor with ureaplasma infection, but not in amniotic fluid of spontaneous preterm labor without ureaplasma infection, or in amniotic fluid of induced preterm birth that was Ureaplasma spp. (Up/Uu) negative (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

PGP activity in Amniotic Fluid. ESI-LC MS/MS of AF demonstrates increased PGP in amniotic fluid if Ureaplasma culture is positive with spontaneous preterm birth (SPTB), but not with indicated preterm birth or SPTB with negative Ureaplasma and bacterial cultures. (n = 8 per group, *p<0.05 vs. other groups, gray bar indicates Ureaplasma culture negative, black bar indicates Ureaplasma culture positive).

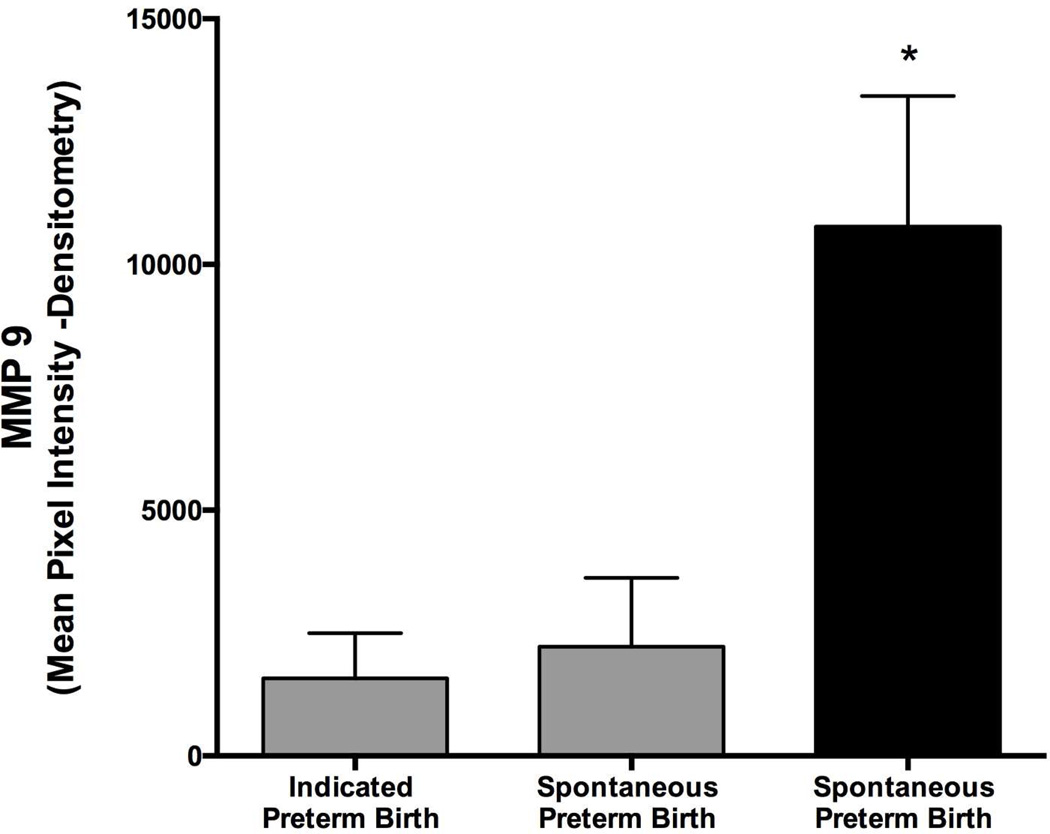

Analysis of MMP-9

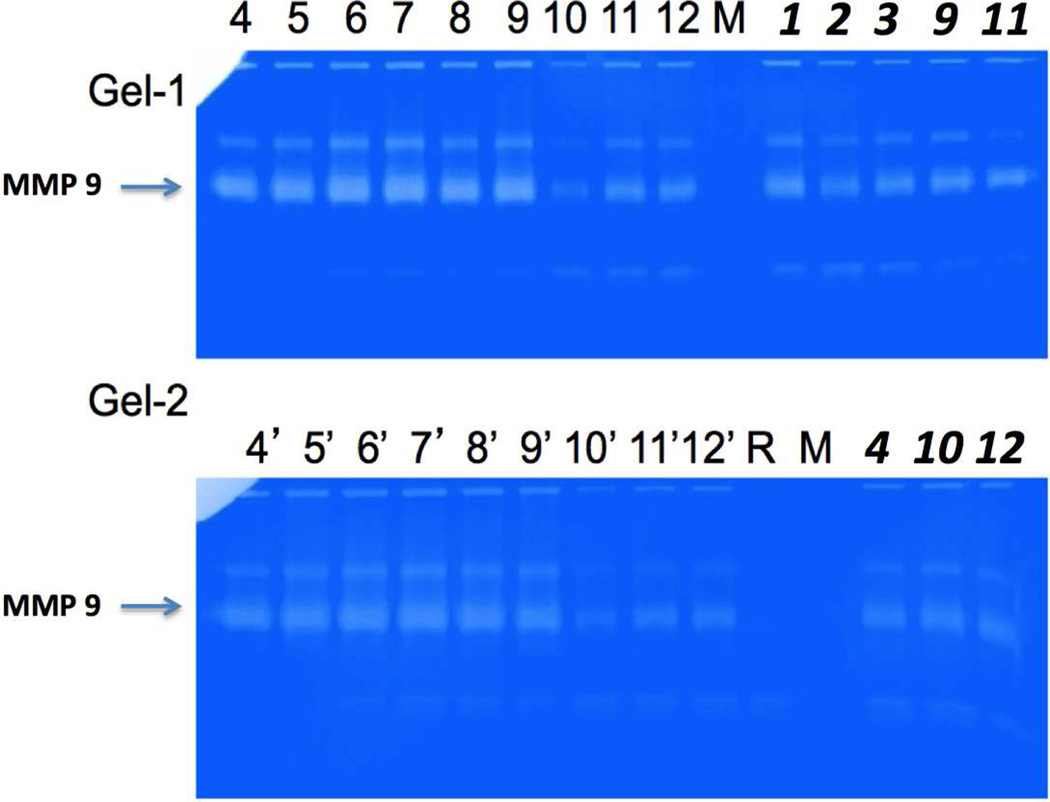

As PGP was evident in amniotic fluid from individuals with Ureaplasma infection, we evaluated whether MMP-9 activity might also be elevated in these samples. As shown (Figure 2, Figure 3), gelatinase activity was elevated in amniotic fluid from spontaneous preterm labor patients with Ureaplasma infection, and was correlated with PGP (r = 0.53, p = 0.01). Since PMNs are a major cell type responsible for production of MMP-9, which is required for the generation of PGP, the potential role of Ureaplasma in a feed-forward cycle of MMP-9 production was investigated by examining whether Ureaplasma induces MMP-9 release in neutrophils in vitro. Freshly isolated human PMNs were stimulated with Ureaplasma and 1.0 µg/ml IL-8 as shown in (Figure 4). This concentration was selected as they reflect the relative potency for neutrophil chemotaxis for IL-817. In fact, when both Up3 and Uu10 were incubated with PMNs, there was a notable increase in MMP-9 release (Figure 4) demonstrating a hostpathogen interaction leading to protease release.

Figure 2.

Densitometric estimation of MMP-9 activity in Amniotic Fluid: MMP-9 was increased in amniotic fluid if Ureaplasma culture is positive with spontaneous preterm birth (SPTB), but not with indicated preterm birth or SPTB with negative Ureaplasma cultures (n = 8 / group, *p<0.05 vs. other groups, gray bar indicates Ureaplasma culture negative, black bar indicates Ureaplasma culture positive).

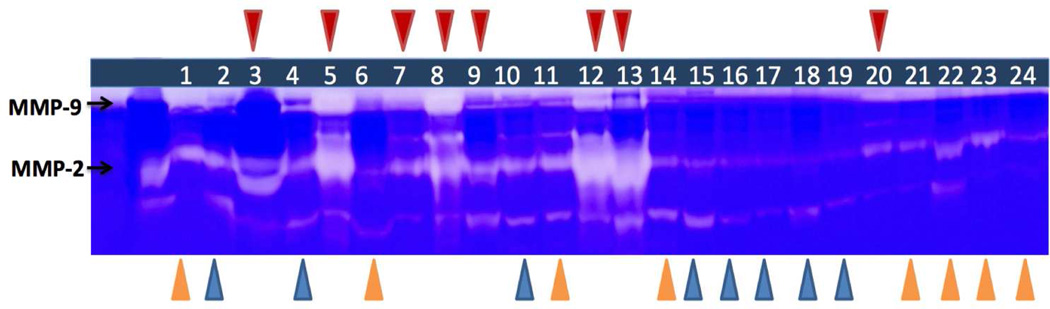

Figure 3.

Gelatin Zymography showing MMP-9 activity is increased in AF of Ureaplasma (+) pregnancies. MMP-9 was increased in amniotic fluid if Ureaplasma culture is positive with spontaneous preterm birth (SPTB – red triangles), but not with indicated preterm birth (blue triangles) or SPTB with negative Ureaplasma cultures (yellow triangles).

Figure 4.

MMP-9 Activity in Human Polymorphonuclear Leukocytes (PMN): MMP-9 was increased in PMNs co cultured with Ureaplasma strains compared to PBS control. The effect was similar to PMN co cultured with IL-8. Figure Key - 4 and 4’: PMN + IL-8 (30 min), 5 and 5’: PMN + IL-8 (45 min), 6 and 6’: PMN + Up3 (30 min), 7 and 7’: PMN + Up3 (45 min), 8 and 8’: PMN + Uu10 (30 min), 9 and 9’: PMN + Uu10 (45 min), 10 and 10’: PMN + PBS/20% FCS + 0.1%HBSS (10 min), 11 and 11’: PMN + PBS/20%FCS + 0.1%HBSS (30 min), 12 and 12’: PMN + PBS/20%FCS + 0.1%HBSS (45 min); 1: PC-PMA (3h), 2: NC-PBS/20%FCS (3h), 3: Up3 (3h), 9: PMA + Up3 (3h), 11: PMA + Up3 + actin (3h); 4: Uu10 (3h), 10: PMA + Uu10 (3h), 12: PMA + Uu10 + actin (3h). (PC - positive control, NC - negative control, PMA - phorbol myristate acetate, PBS - phosphate-buffered saline, FCS - fetal calf serum, HBSS - hank's balanced salt solution, h - hours, min - minutes).

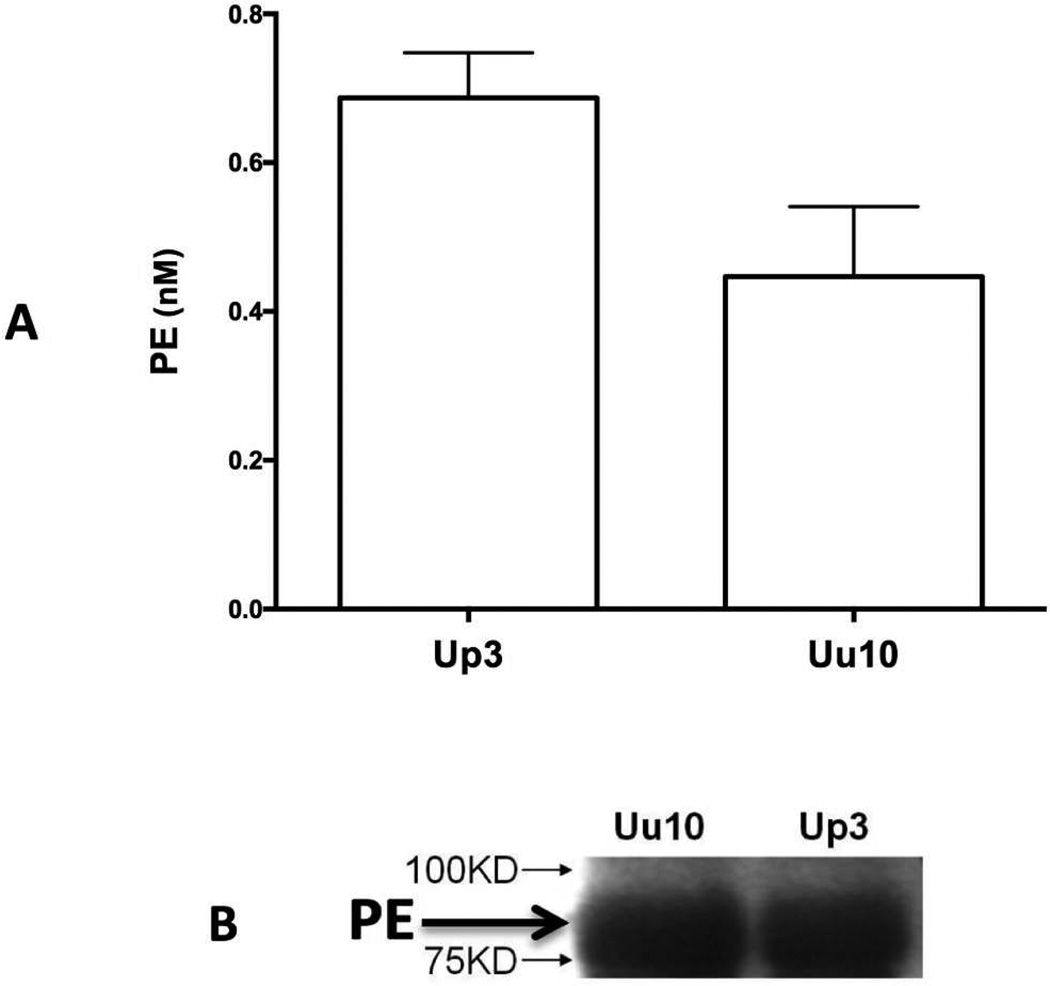

Analysis of PE

PE presence and activity were detected in both Up3 and U. urealyticum serovar (Uu10) lysates (Figure 5), indicating that Up/Uu have the critical enzyme necessary for PGP generation.

Figure 5.

PE presence and activity in Ureaplasma lysate: Both PE presence (A) and PE activity (B) were noted in both Ureaplasma strains examined.

Discussion

Intrauterine infection is often associated with preterm delivery1 and in a non-human primate model, Ureaplasma as the sole pathogen elicits a robust proinflammatory response and leads to preterm labor7. A critical barrier to prevention of Ureaplasma spp. (Up/Uu) induced premature delivery is a current lack of knowledge as to how the organisms initiate preterm premature rupture of membranes or spontaneous preterm labor. The widespread prevalence (35–60%) of Ureaplasma spp. in women of childbearing age4,18–20 and the potential for rising antibiotic resistance21–23 increases the importance of characterizing the process of pathogenesis so that targets for therapeutic strategies can be devised.

In this study, PGP was increased in amniotic fluid during Ureaplasma infection. In addition, these microbes were determined to have the critical prolyl endopeptidase (PE) protease necessary for PGP release from collagen. The increase in gelatinase activity from the amniotic fluid, but not from the Ureaplasma spp., strongly suggests a novel bacteria-host interaction whereby Ureaplasma spp. might induce the release of MMP-9 from host neutrophils and critical interplay of Ureaplasma regulating host protease release. These findings indicate a mechanism whereby Ureaplasma infection leads to collagen fragmentation (which may predispose to preterm rupture of membranes) and PMN influx (leading to chorioamnionitis and additional protease release resulting in more collagen fragmentation). These observations are clinically relevant, as they suggest a potential therapeutic strategy of inhibiting PGP production, which may attenuate chorioamnionitis and delay preterm delivery.

We have previously reported that mid-trimester elevated amniotic fluid MMP-8 is a marker for subsequent PPROM24. MMP-8, in combination with MMP-9, is one of the metalloproteases that generates PGP from collagen. We found that MMP-9 activity was also increased in amniotic fluid during Ureaplasma infection and is correlated with increased PGP. In addition, PE was present and quantified from Up3, which suggests that the generation of PGP could possibly involve a critical host -pathogen interaction (MMPs from neutrophils in combination with PE from Ureaplasma).

One of the weaknesses of our study is that we employed only culture-based methods for Ureaplasma detection. With the advent of genomic methods like 16S sequencing, it has now become possible to detect the microbiome composition of any body organ or fluid. Consistent with other reports about a resident ‘fetal and placental microbiome’25–28, we speculate that the amniotic fluid may harbor other microbes, which could play a role in preterm labor, preterm rupture of membranes, chorioamionitis, and diseases of prematurity such as bronchopulmonary dysplasia.

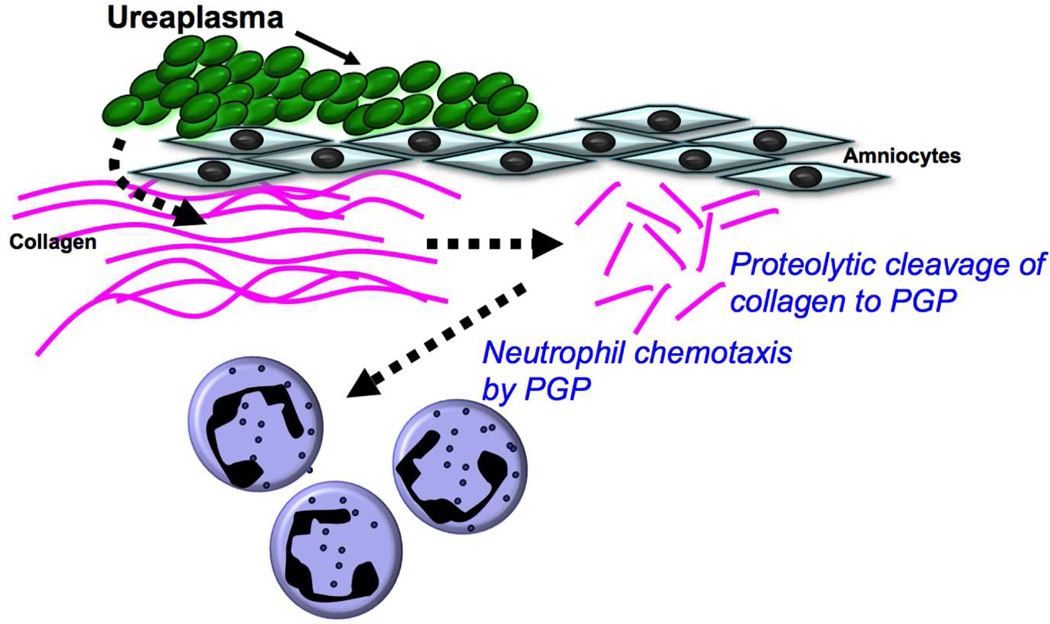

Our study identifies an important alteration in host response due to pertubation in microbial homeostasis leading to preterm rupture of membranes (Figure 6). Further studies involving novel diagnostic and prognostic tools (e.g. Chip-based assays for detection and quantitation of PGP in amniotic or vaginal pool fluid) and novel therapeutic strategies (involving PGP blockade) are warranted.

Figure 6.

Schematic showing the proposed mechanism of PGP mediated premature rupture of membranes and chorioamnionitis.

Methods

Patient Samples and ureaplasma cultures: Amniotic fluid samples were collected at birth as a part of a prospective cohort study of 457 consecutive singleton deliveries of infants born between 23 and 32 weeks gestation, conducted at the University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB), Birmingham, AL, between December 1996 and June 200129. Approval was obtained from the Institutional Review board at UAB, with a waiver of informed consent requirement. Amniotic fluid samples were collected processed and cultured as described previously (26). Ureaplasma cultures enabled the identification of organisms to the genus level based on colonial morphology and urease production on A8 agar (ATCC type strains for U. parvum serovar 3 and U. urealyticum serovar 10). Further identification of Ureaplasma to species level was not possible since no PCR testing was performed on the isolates, but there is no reason to believe this information would have affected the interpretation of the results. Spontaneous preterm birth was defined as delivery after either spontaneous preterm labor or spontaneous preterm premature rupture of membranes (PROM). Indicated preterm birth was defined as delivery effected for maternal or fetal indications. A total of 24 random amniotic fluid samples were analyzed, 16 of which were Ureaplasma culture negative (indicated preterm birth, n=8; spontaneous preterm birth, n=8) and 8 of which were Ureaplasma culture positive (spontaneous preterm birth, n=8). The clinical characteristics and demographics of the study population have been described in previous publications29,30.

Analysis

PGP measurement

PGP, was measured using a MDS Sciex API-4000 spectrometer (Applied Biosystems Inc, CA, USA) equipped with HPLC (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan). HPLC was performed using a 2.1 × 150 mm Develosi C30 column. Background was removed by flushing with 100% isopropanol/0.1% formic acid. Positive electrospray mass transitions are at 270-70 and 270-116 for PGP.

Gelatin Zymography

10 µl of specimen was mixed with 5 µl of sample loading buffer, loaded and run on a 10% polyacrylamide gel with gelatin (Criterion zymogram pre-cast gel, Bio-Rad Life Science Research, Hercules, CA.) followed by renaturation, development, and Coomassie Blue staining and destaining as per a standard protocol (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) as previously described31. Bands were identified corresponding to both active MMP-9 and MMP-2.

PE activity

20 µl of specimen was incubated with 2mM Z-Gly-Pro-pNa for 24 h at 37°C and 5% CO2, and cleavage of para-nitroaniline (pNa) from the substrate is detected spectrophotometrically at 410nm and compared to a generated standard curve for PE activity. These methods have been previously described13.

PE Western Blotting

Ureaplasma lysate was separated by SDS-PAGE under reducing conditions and transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes. Membranes were blocked in 5% dry non-fat milk for 1 h at room temperature and incubated with polyclonal, rabbit, anti-PE antibody (22.4 µg/ml) for 1 h at room temperature. After incubation, membranes were washed and incubated with goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody conjugated with horseradish peroxidase (Southern Biotechnology, Birmingham, AL) for 1 h. Immunoblots were developed by chemiluminescence (Pierce, Rockford, IL).

Statistical Analysis

Results from multiple groups were analyzed by 2-way ANOVA followed by the Tukey multiple-comparison test if significant differences are found. The SigmaPlot v.12 statistical package (Systat Software, Inc. San Jose, CA) was used for analysis.

Acknowledgments

Funding Source: This study was supported in parts by National Institute of Health (NIH) Bethesda, MD – NIH R01 HL092906 (N.A) and NIH R01 HL129907 (N.A, C.L); NIH R01 HL102371 (A.G); NIH R01 AI072577 (K.W)

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest/Financial Disclosures: There are no conflicts of interest or financial disclosures (other than funding as stated above) for any of the authors.

References

- 1.Goldenberg RL, Hauth JC, Andrews WW. Intrauterine infection and preterm delivery. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1500–1507. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200005183422007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tita AT, Andrews WW. Diagnosis and management of clinical chorioamnionitis. Clin Perinatol. 2010;37:339–354. doi: 10.1016/j.clp.2010.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yoon BH, Romero R, Moon JB, et al. Clinical significance of intra-amniotic inflammation in patients with preterm labor and intact membranes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;185:1130–1136. doi: 10.1067/mob.2001.117680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Waites KB, Katz B, Schelonka RL. Mycoplasmas and ureaplasmas as neonatal pathogens. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2005;18:757–789. doi: 10.1128/CMR.18.4.757-789.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Larsen B, Hwang J. Mycoplasma, Ureaplasma, and adverse pregnancy outcomes: a fresh look. Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol. 2010 doi: 10.1155/2010/521921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oh KJ, Lee KA, Sohn YK, et al. Intraamniotic infection with genital mycoplasmas exhibits a more intense inflammatory response than intraamniotic infection with other microorganisms in patients with preterm premature rupture of membranes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;203:211 e1–211 e8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2010.03.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Novy MJ, Duffy L, Axthelm MK, et al. Ureaplasma parvum or Mycoplasma hominis as sole pathogens cause chorioamnionitis, preterm delivery, and fetal pneumonia in rhesus macaques. Reprod Sci. 2009;16:56–70. doi: 10.1177/1933719108325508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zheng X, Teng LJ, Watson HL, Glass JI, Blanchard A, Cassell GH. Small repeating units within the Ureaplasma urealyticum MB antigen gene encode serovar specificity and are associated with antigen size variation. Infect Immun. 1995;63:891–898. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.3.891-898.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ligon JV, Kenny GE. Virulence of ureaplasmal urease for mice. Infect Immun. 1991;59:1170–1171. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.3.1170-1171.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.O'Reilly P, Jackson PL, Noerager B, et al. N-alpha-PGP and PGP, potential biomarkers and therapeutic targets for COPD. Respir Res. 2009;10:38. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-10-38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van den Broek NR, White SA, Goodall M, et al. The APPLe study: a randomized, community-based, placebo-controlled trial of azithromycin for the prevention of preterm birth, with meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000191. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.O'Reilly PJ, Hardison MT, Jackson PL, et al. Neutrophils contain prolyl endopeptidase and generate the chemotactic peptide PGP, from collagen. Journal of neuroimmunology. 2009;217:51–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2009.09.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gaggar A, Jackson PL, Noerager BD, et al. A novel proteolytic cascade generates an extracellular matrix-derived chemoattractant in chronic neutrophilic inflammation. J Immunol. 2008;180:5662–5669. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.8.5662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gaggar A, Rowe SM, Matthew H, Blalock JE. Proline-Glycine-Proline (PGP) and High Mobility Group Box Protein-1 (HMGB1): Potential Mediators of Cystic Fibrosis Airway Inflammation. Open Respir Med J. 2010;4:32–38. doi: 10.2174/1874306401004010032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Overbeek SA, Braber S, Koelink PJ, et al. Cigarette smoke-induced collagen destruction; key to chronic neutrophilic airway inflammation? PloS One. 2013;8:e55612. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0055612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Akthar S, Patel DF, Beale RC, et al. Matrikines are key regulators in modulating the amplitude of lung inflammation in acute pulmonary infection. Nature Commun. 2015;6:8423. doi: 10.1038/ncomms9423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weathington NM, van Houwelingen AH, Noerager BD, et al. A novel peptide CXCR ligand derived from extracellular matrix degradation during airway inflammation. Nat Med. 2006;12:317–323. doi: 10.1038/nm1361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kafetzis DA, Skevaki CL, Skouteri V, et al. Maternal genital colonization with Ureaplasma urealyticum promotes preterm delivery: association of the respiratory colonization of premature infants with chronic lung disease and increased mortality. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;39:1113–1122. doi: 10.1086/424505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kataoka S, Yamada T, Chou K, et al. Association between preterm birth and vaginal colonization by mycoplasmas in early pregnancy. J Clin Microbiol. 2006;44:51–55. doi: 10.1128/JCM.44.1.51-55.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gonzalez Bosquet E, Gene A, Ferrer I, Borras M, Lailla JM. Value of endocervical ureaplasma species colonization as a marker of preterm delivery. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2006;61:119–123. doi: 10.1159/000089457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xiao L, Crabb DM, Duffy LB, et al. Mutations in ribosomal proteins and ribosomal RNA confer macrolide resistance in human Ureaplasma spp. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2011;37:377–379. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2010.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Waites KB, Crabb DM, Duffy LB. Comparative in vitro susceptibilities of human mycoplasmas and ureaplasmas to a new investigational ketolide, CEM-101. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2009;53:2139–2141. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00090-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Waites KB, Crabb DM, Duffy LB. In vitro activities of ABT-773 and other antimicrobials against human mycoplasmas. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2003;47:39–42. doi: 10.1128/AAC.47.1.39-42.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Biggio JR, Jr, Ramsey PS, Cliver SP, Lyon MD, Goldenberg RL, Wenstrom KD. Midtrimester amniotic fluid matrix metalloproteinase-8 (MMP-8) levels above the 90th percentile are a marker for subsequent preterm premature rupture of membranes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;192:109–113. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.06.103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Payne MS, Bayatibojakhi S. Exploring preterm birth as a polymicrobial disease: an overview of the uterine microbiome. Front Immunol. 2014;5:595. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wassenaar TM, Panigrahi P. Is a foetus developing in a sterile environment? Lett Appl Microbiol. 2014;59:572–579. doi: 10.1111/lam.12334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Collado MC, Rautava S, Aakko J, Isolauri E, Salminen S. Human gut colonisation may be initiated in utero by distinct microbial communities in the placenta and amniotic fluid. Sci Rep. 2016;6:23129. doi: 10.1038/srep23129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Aagaard K, Ma J, Antony KM, Ganu R, Petrosino J, Versalovic J. The placenta harbors a unique microbiome. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6:237ra65. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3008599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Goepfert AR, Andrews WW, Carlo W, et al. Umbilical cord plasma interleukin-6 concentrations in preterm infants and risk of neonatal morbidity. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;191:1375–1381. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.06.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Goldenberg RL, Andrews WW, Faye-Petersen O, Cliver S, Goepfert AR, Hauth JC. The Alabama Preterm Birth Project: placental histology in recurrent spontaneous and indicated preterm birth. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;195:792–796. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2006.05.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ambalavanan N, Nicola T, Li P, et al. Role of matrix metalloproteinase-2 in newborn mouse lungs under hypoxic conditions. Pediatr Res. 2008;63:26–32. doi: 10.1203/PDR.0b013e31815b690d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]