Abstract

Objective

Anxiety, the most common and impairing psychological problem experienced by youth, is associated with numerous individual and environmental factors. Two such factors include childhood emotional abuse (CEA) and low distress tolerance (DT). The current study aimed to understand how CEA and low DT impacted anxiety symptoms measured annually across five years among a community sample of youth. We hypothesized DT would moderate the relationship between CEA and anxiety, such that youth with higher levels of CEA and lower levels of DT would have elevated anxiety over time.

Method

Community youth (N = 244) were annually assessed across five years using the Revised Child Anxiety and Depression Scale, Childhood Trauma Questionnaire, and Behavioral Indicator of Resiliency to Distress.

Results

Higher CEA at baseline was associated with higher anxiety at baseline, higher anxiety at each annual assessment, and with greater overall decreases in anxiety over time. Lower DT was associated with higher anxiety at baseline, but did not predict changes in anxiety over time. Baseline DT significantly moderated the relationship between baseline CEA and anxiety, such that youth with both higher CEA and lower DT had the highest anxiety at each annual assessment.

Conclusions

Youth with lower DT and higher CEA scores had the highest level of anxiety symptoms across time.

Keywords: anxiety, distress tolerance, childhood emotional abuse, longitudinal, gender

Anxiety disorders are among the most persistent, recurrent, and frequently diagnosed psychiatric conditions across the lifespan (Bruce et al., 2005; Kessler et al., 2012). Problems with anxiety typically emerge during childhood and adolescence (Roza, Hofstra, van der Ende, & Verhulst, 2003), with 10–25% of youth reporting clinically significant symptoms of anxiety (Kessler et al., 2012). Among youth, sub-threshold levels of anxiety are associated with significant functional impairments in familial relationships, school, and other life domains (Angold, Costello, Farmer, Burns, & Erkanli, 1999). Indeed, over time, youth with sub-threshold anxiety have significantly increased odds (3.7 to 13.5) of legal (serious criminality, incarceration), financial (high school dropout, unable to keep job), and social (early parenthood) problems, as compared to youth without sub-threshold anxiety symptoms (Copeland, Wolke, Shanahan, & Costello, 2015). Interestingly, epidemiological work demonstrates that more than 50% of youth receiving mental health treatment do not actually meet diagnostic criteria for psychiatric disorders, but rather may be experiencing functional impairments related to sub-diagnostic symptomatology (Angold et al., 1999). This suggests problems associated with anxiety are more widespread than diagnosis rates suggest and that sub-threshold symptoms greatly impact youth.

Although elevated rates of anxiety are generally observed cross-sectionally, there have been conflicting findings regarding stability and changes in anxiety during childhood and adolescence (Cooper-Vince, Chan, Pincus, & Comer, 2014; Copeland, Angold, Shanahan, & Costello, 2014; Gullone, King, & Ollendick, 2001; Hale Raaijmakers, Muris, van Hoof, & Meeus, 2008). Thus, when attempting to understand patterns of anxiety among youth, it is not only relevant to examine factors predictive of anxiety symptoms more broadly, but also to examine factors associated with stability and change over time, as anxiety during this period is strongly predictive of anxiety and impairments during adulthood (Copeland et al., 2014). Following from this, exploring early baseline risk factors influencing the course of anxiety not only is relevant in understanding how and why anxiety develops, but also in considering appropriate interventions for anxiety symptoms across the spectrum of severity. Two relevant risk factors we will discuss here are childhood emotional abuse and low distress tolerance.

Childhood emotional abuse (CEA), defined as verbal assaults or humiliating/demeaning behavior directed towards a child by an adult (Bernstein & Fink 1998) is at the core of all forms of child abuse (Hart & Brassard, 1987) and is part of an entrenched maladaptive relationship pattern that develops between an adult and child (Glaser, 2002). Large cross-sectional studies of youth demonstrate CEA is more strongly associated with anxiety than physical or sexual abuse (Al-Fayez, Ohaeri, & Gado, 2012; Tonmyr, Williams, Hovdestad, & Draca, 2011) and uniquely predicts anxiety above and beyond other forms of abuse (Mills et al., 2013). Further, CEA predicts elevated anxiety across nine months among 12–13 year-olds (Hamilton et al., 2013). Findings among adults demonstrate CEA, as compared to other forms of abuse, is more strongly associated with the presence and severity of anxiety, and that CEA is associated with more pervasive and chronic anxiety (Hovens, Giltay, Spinhoven, Pennix, & Zitman, 2012; Kuo et al., 2011; Schneider, Baumrind, & Kimerling, 2007; Shi, 2013; Simon et al., 2009). Although there are clear associations between CEA and anxiety (see meta-analysis: Fernandes & Osório, 2015), it is unclear how CEA affects anxiety among youth over time, as the majority of research in this area has been cross-sectional, retrospective, or limited in the period of time examined. Given that CEA is the most common form of abuse children experience (Edwards et al., 2003), it would be useful to determine whether it is potent enough to result in elevated anxiety across development, rather than solely examining its impact at one assessment point.

Beyond prospectively examining the impact of CEA on anxiety, it is also relevant to consider which youth develop anxiety following CEA. Although there are strong relations between CEA and anxiety, not all youth develop anxiety following abuse, suggesting the importance of considering individual-level factors influencing youths’ responses to abusive adult behaviors. One relevant factor to consider is low distress tolerance (DT), conceptualized as the perceived or actual inability to tolerate negative experiential states (e.g., negative emotions, discomfort, uncertainty; Leyro, Zvolensky, & Bernstein, 2010). Low DT can be understood within a negative reinforcement framework, which emphasizes the escape and avoidance of negative affective states as a primary motivational factor. Following from this, we might expect low DT youth to have considerable difficulties managing distress associated with experiencing CEA, and to make attempts to avoid interactions with adults, as well as the resulting distress. This conceptualization fits well with behavioral theories of anxiety, which suggest avoidance is critical in the development and persistence of anxiety (Barlow, 2004), thereby explaining why low DT youth (e.g., Cummings et al., 2013; Danielson, Ruggiero, Daughters, & Lejuez, 2010; Daughters, Gorka, Magidson, MacPherson, & Seitz-Brown, 2013; Daughters et al., 2009) and adults (Banducci, Bujarski, Bonn-Miller, Patel, & Connolly, 2016; Keough, Riccardi, Timpano, Mitchell, & Schmidt, 2010; Telch, Jacquin, Smits, & Powers, 2003) experience particularly elevated anxiety. Although the tendency to engage in avoidant behaviors might be adaptive in abusive environments, when expressed across all relationships, this type of avoidant response is associated with emotional arousal, vigilance, and anxiety (Cicchetti & Sroufe, 2000; Cloitre, Cohen, & Koenen, 2006; Kring & Bachoeowski, 1999; Shankman & Klein, 2003). Moreover, among low DT youth who are experiencing CEA, their frequent inability to escape or avoid abusive caregivers may lead to particularly heightened anxiety symptoms. Thus, youth who have experienced CEA and who have low DT might be those most likely to respond in an anxious/avoidant manner to abusive parental behaviors more specifically, and to interpersonal interactions more broadly, resulting in problematic anxiety symptoms.

Current Study

In order to explore the impact of CEA and DT on anxiety from early through middle adolescence, we examined trajectories of anxiety symptoms across five annual waves of data collection, as a function of these factors. Broadly, we hypothesized that: (1) anxiety symptoms would decrease over time, in line with previous research (e.g., Cooper-Vince et al., 2014; Gullone et al., 2001; Hale et al., 2008); (2) youth with higher levels of self-reported CEA, or lower levels of DT, would have higher anxiety symptoms than their peers across the five assessments; and (3) given that we expected low DT youth to be most reactive to CEA, we expected that DT would moderate the relations between CEA and anxiety, such that youth with lower DT scores and higher CEA scores would have the highest anxiety symptoms.

Method

Participants

The current study included youth recruited to take part in a larger longitudinal study of behavioral, environmental, and genetic mechanisms for HIV-related risk behaviors (see Banducci et al., 2013; Cummings et al., 2013). Youth and their families were recruited from the Washington D.C. Metropolitan Area through media outreach, postings, and fliers at community centers, area schools, libraries, and Boys and Girls clubs. Interested families, with 5th and 6th grade youth, were screened for proficiency in English and their willingness to take part in annual assessments; there were no other inclusion criteria. The original cohort included 277 youth who were asked to participate annually over the course of six assessments; as key measures were not introduced until the second wave of data collection, the current study utilized data collected during Waves 2–6. Of the original sample of 277 youth in the first cohort, 244 youth (45% girls; 49% White, 35% Black, 3% Latino/a, 1% Asian, 12% “Mixed/Other”) between ages 10 and 14 (Mage=12.07, SDage = 0.91) participated at the second wave of assessment (considered the baseline for the purposes of the current study). Youth who completed both Waves 1 and 2 did not significantly differ from youth who only completed Wave 1 on any demographic or study variables (ps > .27). Sample characteristics and the number of youth participating in each wave are included in Table 1.

Table 1.

Means and Standard Deviations of Dependent and Independent Variables

| Factor M (SD) |

Wave 2 N = 244 |

Wave 3 N = 246 |

Wave 4 N = 231 |

Wave 5 N = 210 |

Wave 6 N = 179 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anxiety | 22.41 (13.38) | 20.60 (13.01) | 19.92 (12.70) | 18.69 (11.58) | 17.63 (12.19) |

| Age | 12.01 (0.82) | 13.05 (0.89) | 14.01 (0.89) | 15.04 (0.95) | 16.02 (0.99) |

| Percentage Quit BIRD | 50.2% | 52.0% | 53.4% | 56.1% | 53.0% |

| Persistence on BIRD | 219.01 (102.53) | 215.94 (101.18) | 211.43 (106.52) | 194.73 (115.24) | 201.11 (113.15) |

| % Youth with Score ≥ 9 on CEA | 21.7% | 27.4% | 22.0% | 19.9% | 20.6% |

| CEA Score | 7.54 (3.50) | 7.85 (3.36) | 7.47 (3.04) | 7.45 (3.03) | 7.81 (2.98) |

| Sex | 54.5% male | 55.9% male | 56.3% male | 56.5% male | 58.2% male |

| Family Annual Income | 97,809 + 55,163 | 103,187 + 55,832 | 103,910 + 58,883 | 109,510 + 62,010 | 106,620 + 70,079 |

“Anxiety” is the Total Anxiety Composite score on the Revised Child Anxiety and Depression Scale; “BIRD” is the Behavioral Indicator of Resiliency to Distress (score is persistence is in seconds); “CEA” is Childhood Emotional Abuse. CEA Score is the total emotional abuse subscale score on the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire, Family Annual Income is in dollars.

To determine whether data were missing completely at random (MCAR), we conducted Little’s MCAR test (1998). Based on Little’s test, our data were MCAR (χ2 = 77.42, p = .78). This suggests missing data on the dependent variable (Anxiety) at each assessment wave (waves 2–6) and independent variables (CEA, DT, and gender) were not dependent upon the values or potential values of any of our variables.

Procedure

Trained research assistants conducted the assessment sessions. Study procedures and confidentiality were separately described to parents and youth at each assessment; informed consent and assent were obtained annually. Youth and their parents were administered measures in separate, private rooms. Parents provided demographic information about themselves and their child. Youth completed several self-report measures and two computerized tasks that were a part of the larger study. Each assessment lasted approximately two hours; computerized tasks took 10–15 minutes to complete, self-report measures took 60–90 minutes to complete. Parents were paid for their participation. Youth were compensated with toys, games, or gift cards. The University of Maryland Institutional Review Board approved study procedures.

Measures

Revised Child Anxiety and Depression Scale (RCADS; Chorpita et al., 2000)

The RCADS is a reliable and valid self-report questionnaire for youth corresponding to DSM-IV anxiety and depressive disorders (Chorpita et al., 2000). In line with previous studies (e.g. Ebesutani et al., 2011; 2012), we created a Total Anxiety composite, which included 37 items from five anxiety disorder subscales (6–9 items per disorder; separation anxiety, social phobia, generalized anxiety, panic, and obsessive compulsive disorder were included). Items in this composite score were ranked on a 4-point Likert scale on frequency of occurrence (0 = never to 3 = always; range 0 – 111). Items targeted anxiety symptoms experienced by youth (e.g., “I worry when I think I have done poorly at something”), which all load onto a broad anxiety factor (Ebustani et al., 2012) that we examined continuously. This composite has convergent and divergent validity when compared to other measures of anxiety and depression (Ebesutani et al., 2011; 2012), with higher scores indicating higher levels of anxiety. Across our five annual assessments, internal consistency of this RCADS Anxiety Total (hereafter referred to as “Anxiety”) was excellent (α = .93 – .97).

Childhood Trauma Questionnaire, emotional abuse subscale (CTQ; Bernstein & Fink 1998)

The CTQ is a well-validated, reliable self-report measure of CEA, with discriminant, convergent, and construct validity (Bernstein, Fink, Handelman, & Foote, 1994; Fink, Bernstein, Handelsman, Foote, & Lovejoy, 1995). The CTQ has good sensitivity and satisfactory specificity compared to child welfare records and family/clinician reports (Bernstein, Ahluvalia, Pogge, & Handelsman, 1997). We administered the Emotional Abuse subscale, which includes five items scored on a five point Likert scale (1 = never true to 5 = very often true; total score range: 5–25) and examines whether participants experienced humiliating or demeaning behavior from adults in their lives (e.g., “People in my family called me things like stupid, lazy, or ugly”). We did not administer the Physical or Sexual Abuse subscales. Internal consistency of the CEA subscale for Waves 2–6 was good (α = .79 – .84) and CEA scores were highly correlated across the five Waves (Table 2). We examined CEA scores continuously as a predictor of Anxiety scores.

Table 2.

Correlation Matrix of Dependent and Independent Variables

| Gender | CEA W2 |

CEA W3 |

CEA W4 |

CEA W5 |

CEA W6 |

DT W2 |

DT W3 |

DT W4 |

DT W5 |

DT W6 |

Anx W2 |

Anx W3 |

Anx W4 |

Anx W5 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CEA W2 | .045 | __ | |||||||||||||

| CEA W3 | .005 | .591** | __ | ||||||||||||

| CEA W4 | −.105 | .426** | .558** | __ | |||||||||||

| CEA W5 | −.121 | .462** | .416** | .581** | __ | ||||||||||

| CEA W6 | −.182* | .306** | .340** | .482** | .706** | __ | |||||||||

| DT W2 | .006 | −.032 | .003 | −.087 | −.025 | −.047 | __ | ||||||||

| DT W3 | .078 | −.062 | −.038 | −.151* | −.173* | −.169* | .355** | __ | |||||||

| DT W4 | −.025 | −.068 | −.033 | −.068 | −.019 | .046 | .452** | .428** | __ | ||||||

| DT W5 | −.046 | −.047 | −.001 | −.054 | −.104 | −.080 | .259** | .434** | .440** | __ | |||||

| DT W6 | .015 | .045 | .048 | −.010 | −.038 | .000 | .270** | .370** | .408** | .553** | __ | ||||

| Anx W2 | −.013 | .533** | .427** | .304** | .306** | .253** | −.145* | −.042 | −.013 | −.049 | −.038 | __ | |||

| Anx W3 | −.193** | .288** | .304** | .305** | .25zc1** | .222** | −.090 | −.120 | −.020 | −.027 | −.019 | .602** | __ | ||

| Anx W4 | −.218** | .266** | .216** | .367** | .314** | .211** | −.180** | −.167* | −.053 | −.058 | −.112 | .437** | .576** | __ | |

| Anx W5 | −.246** | .183* | .227** | .389** | .342** | .258** | −.108 | −.157* | −.110 | −.036 | −.038 | .414** | .565** | .662** | __ |

| Anx W6 | −.253** | .065 | .181* | .290** | .207** | .311** | −.255** | −.218** | −.110 | −.031 | −.053 | .411** | .480** | .598** | .693** |

Note:

p < .05;

p < .01.

Phi coefficients are reported for correlations within dichotomous variables over time. Otherwise, Pearson correlations are presented.

“W” is Wave; “Anx” is the Total Anxiety Composite score on the Revised Child Anxiety and Depression Scale; “DT” is the score in seconds on the Behavioral Indicator of Resiliency to Distress; “CEA” is the total emotional abuse subscale score on the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire.

Gender is dichotomized as female = 0, male = 1.

The Behavioral Indicator of Resiliency to Distress

(BIRD; Lejuez, Daughters, Danielson, & Ruggiero, 2006) was developed based upon the adult computerized distress tolerance task, the PASAT-C (Lejuez et al., 2003). The BIRD has previously been used as an indicator of DT among youth (Daughters et al., 2009; 2013; Danielson et al., 2010; MacPherson et al., 2010). Briefly, during the BIRD, youth have the option of persisting on a distressing task (with positive reinforcement available for persisting), or quitting the task to reduce emotional distress (see Daughters et al., 2009 or MacPherson et al., 2010 for a thorough description of the task). As in previous studies, youth were shown possible prizes they could earn prior to beginning the task (e.g., DVDs, games, art supplies, sporting equipment, gift cards, etc.), but were not provided information about the number of points necessary to earn the prizes. Consistent with previous studies, persistence on the final level of the BIRD was used to assess DT and was indicated by the number of seconds youth persisted (range: 0–300 seconds). Youth who quit the task perform equally well, and do not differ in the amount of self-reported distress elicited by the task, as compared to youth who do not quit the task (Daughters et al., 2009; Danielson et al., 2010; MacPherson et al., 2010). Previous work provides support for concurrent validity (Daughters et al., 2008) and test re-test reliability (Cummings et al., 2013) of the BIRD.

Positive and Negative Affect Schedule-Children (PANAS-C; Laurent et al, 1999)

As in prior work using the BIRD, youth completed the 27-item PANAS-C before the task and after the second level of the task (Daughters et al., 2009) to ensure youth experienced an increase in distress post-task. The PANAS-C has been used to measure positive and negative affect by asking youth to rate adjectives for a variety of mood states (e.g., nervous, guilty, joyful, gloomy) on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = very slightly or not at all to 5 = extremely) based on how they are feeling. The PANAS-C has good convergent and discriminant validity (Laurent et al., 1999). As in previous studies (e.g., Daughters et al., 2009; MacPherson et al., 2010), distress was indexed based on the composite of mad, frustrated, upset, embarrassed, and nervous (range = 5 – 25), with pre to post BIRD comparisons of this distress composite.

Analyses

Preliminary analyses

In order to ensure the BIRD was psychologically stressful, pre-post affect changes on the PANAS-C was examined using paired samples t-tests. PANAS-C change scores for the distress composite were compared among those who did versus did not quit the BIRD to determine whether quitting was significantly related to negative affect. To ensure the ability to succeed on the task did not impact quit time, quit time was examined as a function of youths’ skill level (see Amstadter et al., 2012; Daughters et al., 2009; MacPherson et al., 2010).

Analytic method

We examined within-subjects variation in Anxiety and predictors of the course of Anxiety using multi-level modeling with HLM 7 (Scientific Software International Inc., IL) to assess individual-level change (level 1) and prediction of individual-level differences in change (level 2). We utilized a multilevel approach to allow for the analysis of covariation in data over time between repeated measures of multiple variables, which are considered to be non-independent observations (Bryk & Raudenbush, 1987). Multilevel modeling enabled us to model growth curves, despite there being missing data for our outcome variable, by estimating the trajectory based on existing data for individuals. Restricted maximum likelihood (REML) uses the EM algorithm (Little & Rubin, 2002; Raudenbush & Bryk, 2002), which produces better estimation than alternative approaches when there are data missing completely at random. Within this type of growth model, main effects at level 2 represent a cross-level interaction with time (Curran, Bauer, & Willoughby, 2006).

For all analyses, Anxiety was treated as the dependent variable. Time was anchored at baseline (time = 0) so the Anxiety intercept (β00) reflected the average of individuals’ Anxiety at baseline. To examine main effects and interactions of level 2 predictors on the intercept and slope of Anxiety, interaction terms were created by z-score transforming continuous variables, then multiplying the terms to reflect the product of level 2 predictors of interest (Aiken & West, 1991). All models included random slopes and random intercepts.

Model building

We utilized a model building approach to estimate the contributions of level 1 and 2 predictors. Baseline trajectory models were estimated to examine change over time in Anxiety. Linear and quadratic growth models were estimated at level 1 to examine within-subjects regression of an individual’s Anxiety onto the time of each assessment. Then, CEA and DT (at Waves 2–6) were tested as time-varying covariates in the level 1 model to determine their co-occurrence with the Anxiety trajectory.

Between-subjects level 2 variables were examined as predictors of Anxiety over time. Within-subjects intercepts and slopes were treated as outcomes predicted by the between-subjects variables measured at baseline. At level 2, we tested the main effects of covariates (gender, baseline age, race/ethnicity). Then, we examined the effects of baseline DT, baseline CEA, and their interaction to determine whether these factors predicted the Anxiety trajectory. For moderation, we probed interactions with simple slopes tests (Aiken & West, 1991).

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Paired t-tests comparing distress on the PANAS-C pre-post the BIRD revealed distress increased during the task (p < .001 for all Waves). Logistic regression demonstrated youth who did versus did not quit the task did not differ significantly on pre-post changes in distress in response to the BIRD (all p’s > .30 for all Waves). Logistic regression revealed youths’ ability on the task did not predict whether youth quit the BIRD (all p’s > .15 for all Waves).

All means and standard deviations are presented in Table 1. In general, Anxiety, CEA, and DT scores were moderately stable over time, with some decreases in Anxiety (Table 1). Using a cutoff score of nine for the CEA subscale (Bernstein & Fink, 1998) 20–27% of youth experienced CEA across all Waves (Table 1). Table 2 presents correlations between Anxiety scores at the five assessment points and all major study independent variables. Baseline CEA and Anxiety were significantly correlated at Waves 2–5 and CEA measured at each wave was significantly correlated with Anxiety measured at the same wave and at the following wave. Baseline DT and Anxiety were correlated at Waves 2, 4, and 6.

Model Building

In line with our first hypothesis, our level 1 model demonstrated a significant linear decrease in Anxiety over time, but not a significant quadratic effect (Table 3). Thus, we included a linear term, but not a quadratic term, in our equation estimating Anxiety over time. Within this model, the random error terms associated with the intercept and slope were significant, demonstrating variability among youth Anxiety, supporting the examination of between-person predictors of these components. We examined CEA and DT measured at each assessment (all Waves) on level 1 as time varying covariates to determine whether they contributed to this model. There was a positive longitudinal association between CEA and Anxiety measured at each assessment (β = 3.74, SE = 0.48, t = 7.81, p < .001, r = 0.45); however, there was not a significant longitudinal association between DT and Anxiety (p > .10). Thus, CEA was retained as a time-varying covariate. We also examined whether DT measured at baseline interacted with CEA at each time point; this relationship was not significantly associated with Anxiety (p > .15).

Table 3.

Anxiety as a Function of Childhood Emotional Abuse and Distress Tolerance.

| β | SE | t | r1 | Var. Component | SD | χ2 test of variance | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline Trajectory Model of Anxiety | |||||||

| Intercept | 22.30 | 0.87 | 25.72*** | 133.64 | 11.56 | 830.14*** | |

| Time (slope) | −1.65 | 0.69 | −2.37* | 40.42 | 6.36 | 321.56*** | |

| Time2 (curvature) | 0.15 | 0.16 | 0.93 | 1.26 | 1.12 | 274.00** | |

|

| |||||||

| CEA and DT as Time-Varying Covariates | |||||||

| Intercept | 75.75 | 8.70 | 215.39* | ||||

| Intercept | 22.02 | 0.70 | 31.37*** | ||||

| Time Slope | 5.44 | 2.33 | 244.33*** | ||||

| Intercept | −0.93 | 0.25 | −3.73*** | 0.23 | |||

| CEA Slope | 10.40 | 3.22 | 231.55** | ||||

| Intercept | 4.00 | 0.50 | 8.07*** | 0.46 | |||

| DT Slope | 1.75 | 1.32 | 183.35 | ||||

| Intercept | −0.70 | 0.37 | −1.88 | 0.12 | |||

|

| |||||||

| Full Model with Moderation | |||||||

| Intercept | 68.27 | 8.26 | 496.51*** | ||||

| Intercept | 23.12 | 0.98 | 23.49*** | ||||

| Gender | −1.93 | 1.32 | −1.46 | 0.09 | |||

| Baseline CEA | 5.20 | 0.81 | 6.38*** | 0.38 | |||

| Baseline DT | −1.46 | 0.66 | −2.21* | 0.14 | |||

| Baseline CEAxDT | −2.61 | 0.79 | −3.29*** | 0.20 | |||

| Time Slope | 4.22 | 2.06 | 362.02*** | ||||

| Intercept | −0.50 | 0.33 | −1.49 | ||||

| Gender | −1.14 | 0.45 | −2.54* | 0.16 | |||

| Baseline CEA | −1.25 | 0.24 | −5.13*** | 0.32 | |||

| Baseline DT | −0.08 | 0.22 | −0.34 | 0.02 | |||

| Baseline CEAxDT | 0.52 | 0.25 | 2.05* | 0.13 | |||

| CEA Slope | 7.11 | 2.67 | 248.78* | ||||

| Intercept | 2.59 | 0.49 | 5.27*** | 0.32 | |||

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001.

Effect sizes were computed with the following formula: r = √[t2/(t2 + df)] (Rosenthal, Rosnow, & Rubin, 2000).

“Var” is Variance; “CEA” is the total emotional abuse subscale score on the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire; “DT” distress tolerance measured in seconds on the BIRD, “CEAxDT” is the interaction between CEA and DT.

Gender is coded as 0 = girls, 1 = boys

On level 2, we examined three covariates potentially associated with Anxiety. Baseline age and race/ethnicity were not associated with the slope or intercept of Anxiety (p’s > .05). Gender was not significantly associated with the intercept (p > .05), but was negatively associated with the slope, indicating boys experienced significantly greater decreases in Anxiety over time as compared to girls (β = −1.54, SE = 0.50, t = −3.05, p = .003, r = .19). Because of this, we included gender as a level 2 covariate. Since gender was a significant predictor of the slope of Anxiety, we examined whether it moderated the relationship between baseline CEA and Anxiety, or baseline DT and Anxiety; these relations were not significant (all p’s > .05).

We used the following equations to estimate the effects of our main model:

Level-1 Model

Level-2 Model

Intercept:

Time (Slope):

CEA (Slope):

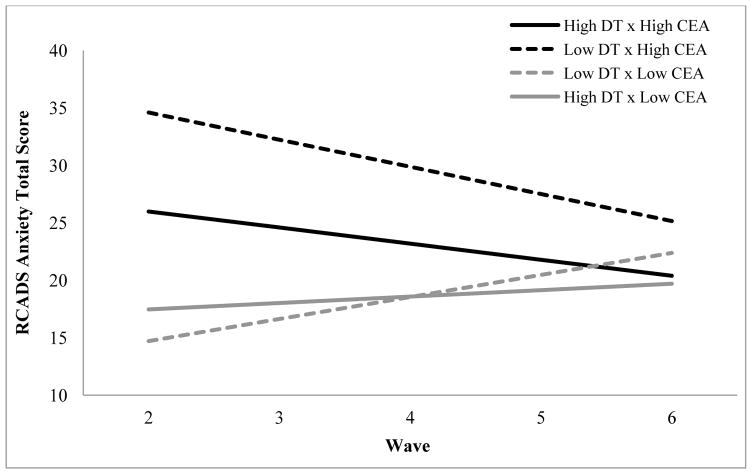

Higher baseline CEA scores were associated with higher baseline Anxiety and with a greater decrease in Anxiety over time, as indicated by a significant effect of CEA on the slope of anxiety over time (Table 3). Lower baseline DT was associated with higher baseline Anxiety, but was not associated with the Anxiety trajectory. There was a significant interaction between baseline DT and baseline CEA on baseline Anxiety and on the Anxiety trajectory. To better understand this interaction, we substituted values one standard deviation above and below mean baseline DT scores into our equations so model coefficients would reflect the effects of baseline CEA when baseline DT was at high and low levels (Figure 1; Aiken & West, 1991). For youth with lower baseline DT, baseline CEA was associated with higher baseline Anxiety (β = 7.58, SE = 1.17, t = 6.50, p < .001, r = 0.39) and with a greater decrease in Anxiety over time (β = −1.80, SE = 0.35, t = −5.15, p < .001, r = 0.32). For youth with higher baseline DT, baseline CEA was associated with lower baseline Anxiety (β = 2.46, SE = 1.07, t = 2.30, p = .02, r = 0.14) and less decrease in Anxiety over time (β = −0.74, SE = 0.32, t = −2.30, p = .02, r = 0.14).

Figure 1. Effects of Baseline Childhood Emotional Abuse and Baseline Distress Tolerance on Anxiety over Time.

CEA” is the total emotional abuse subscale score on the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire; “DT” distress tolerance measured in seconds on the BIRD, “CEAxDT” is the interaction between CEA and DT.

To better understand the patterns of Anxiety for youth with lower DT and higher CEA, we conducted additional simple regression analyses1. In line with hypotheses 2 and 3, the overall pattern of findings from regression analyses suggests that youth with lower DT and higher CEA had the highest Anxiety at Waves 2–5. Thus, despite the greatest declines in anxiety over time among this group, likely due to their particularly elevated baseline Anxiety, these youth had the highest levels of Anxiety at each time point.

Discussion

Adolescence represents a critical developmental period in which to examine individual and environmental factors influencing trajectories of anxiety symptoms. Consistent with our first hypothesis, youth anxiety symptoms decreased across the five waves of this study, which is in line with findings from the literature (Cooper-Vince et al., 2014; Gullone et al., 2001; Hale et al., 2008). In order to determine when it might be most beneficial to intervene with anxious youth who do have persistent anxiety, it is relevant to examine when CEA and DT exert their greatest influence on symptomatology. Given strong cross-sectional associations between CEA and anxiety among youth (e.g., Al-Fayez et al., 2012; Tonmyr et al., 2011), we elected to examine whether these relations persisted across time and whether low DT magnified these effects.

We replicated findings demonstrating higher baseline CEA was associated with higher baseline anxiety (e.g. Tonmyr et al., 2011). Consistent with hypothesis 2, baseline CEA was predictive of elevated anxiety symptoms at each assessment wave, using simple regression analyses. However, despite baseline CEA predicting higher anxiety at each wave, the overall anxiety trajectory across the five years had a steeper negative slope as a function higher CEA. This suggests CEA had a continued effect over time, but that the magnitude of the effect decreased, perhaps because of other developmentally relevant factors. It is possible interactions with adults may have become less salient over time for youth. For example, peer relationships may become more central during middle adolescence. It is relevant to note, however, that previous research demonstrates that low DT adolescents, whose parents respond harshly to them, have the poorest relationships with their peers during middle adolescence (Ehrlich, Cassidy, Gorka, Lejuez, & Daughters, 2013). Thus, harsh parental behavior effects may extend meaningfully over time, but the magnitude of the effects may decrease as youth develop other relationships. This hints at the importance of intervening on CEA earlier in development, given that this when anxiety symptoms are particularly elevated and may be most amenable to change.

Expanding upon previous work demonstrating relations between lower DT and higher anxiety (e.g., Cummings et al., 2013; Daughters et al., 2009; Keough et al., 2010), our study demonstrates youth with lower DT had higher levels of anxiety on average (at Waves 2, 4, and 6) as compared to youth with higher DT, in line with hypothesis 2. Consistent with prior work (Cummings et al., 2013), DT was not associated with changes in anxiety over time, but rather appeared to exert a consistent effect on anxiety symptoms. In line with hypothesis 3, youth with higher CEA and lower DT at baseline had the most elevated levels of anxiety symptoms at each assessment, despite experiencing the sharpest decreases in anxiety over time. Although this observation offers a message of hope, in that these youth experienced lessened anxiety over time, they still had higher anxiety at each assessment point compared to their peers, suggesting they might experience significant functional impairments (Angold et al., 1999; Copeland et al., 2009).

There are a number of strengths of the current study, including the diversity of the sample; the focus on CEA as a prospective predictor of anxiety, in combination with low DT; and the inclusion of multiple assessment waves during a critical developmental transition. Despite this, there are also limitations that must be considered. First, we were unable to examine whether this relationship is specific to CEA, or whether DT also acts as a moderator of the relations between childhood physical/sexual abuse and anxiety. Second, we utilized self-report symptom-based assessments, rather than interviewer-based assessments, which could be subject to information biases or inaccurate reporting. Third, this was a convenience-based community sample. It is necessary to determine whether these relations generalize to randomly selected samples with clinical diagnoses and/or more severe abuse. Fourth, it is possible peer-related behaviors may have a strong impact during this period, which should be examined in future work.

Clinical and Practical Implications

There are a number of broader clinical implications of these findings. Our work suggests the importance of considering CEA in the development and maintenance of anxiety. Too often, researchers and clinicians focus on physical and sexual abuse to the exclusion of emotional abuse, which amplifies the effects of other forms of abuse and is significantly predictive of anxiety (Clemmons, Walsh, DeLillio, & Messman-Moore, 2007). Somewhat reassuringly, within our study the impact of baseline CEA was negligible at the final assessment point. Despite this, baseline CEA was predictive of elevated anxiety symptoms at multiple time points, which could indicate youth with sub-threshold symptoms are at an increased risk of functional impairments, like criminality, incarceration, school dropout, and early parenthood (e.g., Angold et al., 1999; Copeland et al., 2015). Given this, it would be prudent to screen for CEA and intervene among youth experiencing significant anxiety and associated functional impairments.

Simultaneously focusing efforts toward reducing CEA, when this type of behavior is detected in caregivers or other adults interacting with youth, and increasing DT, might result in the best outcomes for youth. Based on this, there are a number of potential areas to target. Aiding caregivers and other adults to become more aware of how their emotionally abusive behaviors affect youth and intervening to change these behaviors is crucial. Clearly, there are challenges associated with targeting CEA, as it is less observable than physical or sexual abuse (Edwards et al., 2003). Despite this, it is important to target CEA both within prevention and intervention efforts. For youth who do develop functionally impairing anxiety symptoms following CEA, evidence-based psychotherapies for anxiety would be recommended (e.g., Silverman, Pina, & Viswesvaran, 2008). An additional avenue of exploration might be targeting low DT within structured interventions, including exposures to uncomfortable internal states (Bornovalova et al., 2012). Further, interventions focused on increasing willingness to experience emotions and engage in valued anxiety-provoking interactions when feeling anxious might be beneficial (e.g., Livheim et al., 2015) for low DT youth. Additional work is necessary in this area to understand how these factors interact and to determine how to best intervene with youth with pre-existing characteristics that increase their vulnerability to anxiety following abusive adult behaviors.

Conclusions

In conclusion, our work demonstrates CEA, low DT, and their interaction are potent predictors of anxiety symptoms over multiple assessment waves. Further extensions and replications of these main effects and interactions are necessary to determine whether these findings extend to other groups and within clinical populations. However, this research does suggest CEA has a significant and lasting impact on anxiety symptomatology, especially among youth with low DT. This highlights the importance of targeted anxiety-related treatment strategies for this vulnerable population. Researchers and clinicians should consider the impact of these factors on anxiety among community youth in order to better understand and serve this population, which is often overlooked in favor of targeting clinical samples.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by NIDA grants: F31 DA035033 (PI: Anne N. Banducci) and R01 DA018647 (PI: C.W. Lejuez).

Footnotes

Using multiple linear regression (CEA and DT were z-score transformed and multiplied to create interaction terms), we found higher baseline CEA scores were significantly associated with higher anxiety at Waves 2, 3, 4, and 5 (all p’s < .01). We found lower DT was significantly associated with higher anxiety at Waves 2, 4, and 6 (all p’s < .05). We found the interaction between DT and CEA was significantly associated with anxiety at Waves 2, 3, 4, and 5 (all p’s < .05). Probing with simple slopes (+ 1 standard deviation for DT), we found for youth with lower DT, CEA predicted higher anxiety at all time points, except Wave 6 (all p’s < .01), whereas for youth with higher DT, CEA predicted lower anxiety at Waves 2–4 (all p’s < .05) and was not associated with anxiety at Waves 5 and 6.

Compliance with Ethical Standards. The authors have no conflicts of interest. All procedures performed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Informed consent and assent was obtained from all participants.

References

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Fayez GA, Ohaeri JU, Gado OM. Prevalence of physical, psychological, and sexual abuse among a nationwide sample of Arab high school students: Association with family characteristics, anxiety, depression, self-esteem, and quality of life. Social Psychiatry And Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2012;47(1):53–66. doi: 10.1007/s00127-010-0311-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amstadter AB, Daughters SB, MacPherson L, Reynolds EK, Danielson C, Wang F, … Lejuez CW. Genetic associations with performance on a behavioral measure of distress intolerance. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2012;46(1):87–94. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2011.09.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angold A, Costello E, Farmer EZ, Burns BJ, Erkanli A. Impaired but undiagnosed. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1999;38(2) doi: 10.1097/00004583-199902000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banducci AN, Bujarski SJ, Bonn-Miller MO, Patel A, Connolly KM. The impact of intolerance of emotional distress and uncertainty on veterans with co-occurring PTSD and substance use disorders. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2016.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banducci AN, Gomes M, MacPherson L, Lejuez CW, Potenza MN, Gelernter J, Amstadter AB. A preliminary examination of the relationship between the 5-HTTLPR and childhood emotional abuse on depressive symptoms in 10–12-year-old youth. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy. 2013;6(1):1–7. doi: 10.1037/a0031121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barlow DH. Anxiety and its disorders: The nature and treatment of anxiety and panic. Guilford press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein DP, Ahluvalia T, Pogge D, Handelsman L. Validity of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire in an adolescent psychiatric population. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1997;36(3):340–348. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199703000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein DP, Fink L. Childhood Trauma Questionnaire Manual. Harcourt, The Psychological Corporation; San Antonio, TX, USA: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein DP, Fink L, Handelsman L, Foote J. Initial reliability and validity of a new retrospective measure of child abuse and neglect. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 1994 doi: 10.1176/ajp.151.8.1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornovalova MA, Gratz KL, Daughters SB, Hunt ED, Lejuez CW. Initial RCT of a distress tolerance treatment for individuals with substance use disorders. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2012;122(1–2):70–76. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruce SE, Yonkers KA, Otto MW, Eisen JL, Weisberg RB, Pagano M, Shea MT, Keller MB. Influence of psychiatric comorbidity on recovery and recurrence in generalized anxiety disorder, social phobia, and panic disorder: a 12-year prospective study. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2005;162:1179–1187. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.6.1179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryk AS, Raudenbush SW. Application of hierarchical linear models to assessing change. Psychological Bulletin. 1987;101(1):147. [Google Scholar]

- Chorpita BF, Yim L, Moffitt C, Umemoto LA, Francis SE. Assessment of symptoms of DSM-IV anxiety and depression in children: A revised child anxiety and depression scale. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2000;38(8):835–855. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(99)00130-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clemmons JC, Walsh K, DiLillo D, Messman-Moore TL. Unique and combined contributions of multiple child abuse types and abuse severity to adult trauma symptomatology. Child Maltreatment. 2007;12(2):172–181. doi: 10.1177/1077559506298248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper-Vince CE, Chan PT, Pincus DB, Comer JS. Paternal autonomy restriction, neighborhood safety, and child anxiety trajectory in community youth. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology. 2014;35(4):265–272. doi: 10.1016/j.appdev.2014.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copeland WE, Angold A, Shanahan L, Costello J. Longitudinal patterns of anxiety from childhood to adulthood: The Great Smoky Mountain Study. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2014;53:21–33. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2013.09.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copeland WE, Wolke D, Shanahan L, Costello EJ. Adult functional outcomes of common childhood psychiatric problems: a prospective, longitudinal study. JAMA psychiatry. 2015;72(9):892–899. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.0730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costello EJ, Egger HL, Copeland W, Erkanli A, Angold A. The developmental epidemiology of anxiety disorders: phenomenology, prevalence, and comorbidity. In: Silverman WK, Field AP, editors. Anxiety disorders in children and adolescents: Research, assessment and intervention. Cambridge University Press; 2011. pp. 56–75. [Google Scholar]

- Cummings JR, Bornovalova MA, Ojanen T, Hunt E, MacPherson L, Lejuez C. Time doesn’t change everything: The longitudinal course of distress tolerance and its relationship with externalizing and internalizing symptoms during early adolescence. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2013;41(5):735–748. doi: 10.1007/s10802-012-9704-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curran PJ, Bauer DJ, Willoughby MT. Testing and Probing Interactions in Hierarchical Linear Growth Models. In: Bergeman Cindy S, Boker Steven M., editors. Methodological issues in aging research. Mahwah, NJ, US: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers; 2006. pp. 99–129. Notre Dame series on quantitative methods. [Google Scholar]

- Danielson C, Ruggiero KJ, Daughters SB, Lejuez CW. Distress tolerance, risk-taking propensity, and PTSD symptoms in trauma-exposed youth: Pilot study. The Behavior Therapist. 2010;33(2):28–34. [Google Scholar]

- Daughters SB, Gorka SM, Magidson JF, MacPherson L, Seitz-Brown CJ. The role of gender and race in the relation between adolescent distress tolerance and externalizing and internalizing psychopathology. Journal of Adolescence. 2013;36(6):1053–1065. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2013.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daughters SB, Reynolds EK, MacPherson L, Kahler CW, Danielson CK, Zvolensky M, Lejuez CW. Distress tolerance and early adolescent externalizing and internalizing symptoms: The moderating role of gender and ethnicity. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2009;47(3):198–205. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2008.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebesutani C, Chorpita BF, Higa-McMillan CK, Nakamura BJ, Regan J, Lynch RE. A psychometric analysis of the Revised Child Anxiety and Depression Scales—Parent Version in a school sample. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2011;39(2):173–185. doi: 10.1007/s10802-010-9460-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebesutani C, Reise SP, Chorpita BF, Ale C, Regan J, Young J, … Weisz JR. The Revised Child Anxiety and Depression Scale-Short Version: Scale reduction via exploratory bifactor modeling of the broad anxiety factor. Psychological Assessment. 2012;24(4):833–845. doi: 10.1037/a0027283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards VJ, Holden GW, Felitti VJ, Anda RF. Relationship between multiple forms of childhood maltreatment and adult mental health in community respondents: results from the adverse childhood experiences study. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2003;160(8):1453–1460. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.8.1453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrlich KB, Cassidy J, Gorka SM, Lejuez CW, Daughters SB. Adolescent friendships in the context of dual risk: The roles of low adolescent distress tolerance and harsh parental response to adolescent distress. Emotion. 2013;13(5):843. doi: 10.1037/a0032587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes V, Osório FL. Are there associations between early emotional trauma and anxiety disorders? Evidence from a systematic literature review and meta-analysis. European Psychiatry. 2015;30(6):756–764. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2015.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaser D. Emotional abuse and neglect (psychological maltreatment): A conceptual framework. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2002;26:697–714. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(02)00342-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gullone E, King NJ, Ollendick TH. Self-reported anxiety in children and adolescents: A three-year follow-up study. The Journal of Genetic Psychology: Research and Theory on Human Development. 2001;162(1):5–19. doi: 10.1080/00221320109597878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hale WW, III, Raaijmakers QAW, Muris P, van Hoof A, Meeus WHJ. Developmental trajectories of adolescent anxiety disorder symptoms: A 5-year prospective community study. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2008;47:556–564. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181676583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton JL, Shapero BG, Stange JP, Hamlat EJ, Abramson LY, Alloy LB. Emotional maltreatment, peer victimization, and depressive versus anxiety symptoms during adolescence: Hopelessness as a mediator. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2013;42(3):332–347. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2013.777916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart SN, Brassard MR. A major threat to children’s mental health: Psychological maltreatment. American Psychologist. 1987;42:160–165. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.42.2.160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hovens JM, Giltay EJ, Wiersma JE, Spinhoven PP, Penninx BH, Zitman FG. Impact of childhood life events and trauma on the course of depressive and anxiety disorders. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2012;126(3):198–207. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2011.01828.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keough ME, Riccardi CJ, Timpano KR, Mitchell MA, Schmidt NB. Anxiety symptomatology: The association with distress tolerance and anxiety sensitivity. Behavior Therapy. 2010;41(4):567–574. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2010.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Avenevoli S, Costello E, Georgiades K, Green J, Gruber MJ, … Merikangas K. Prevalence, persistence, and sociodemographic correlates of DSM- IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication Adolescent Supplement. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2012;69(4):372–380. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kring AM, Bachorowski JA. Emotions and psychopathology. Cognition and Emotion. 1999;13:575–599. [Google Scholar]

- Kuo JR, Goldin PR, Werner K, Heimberg RG, Gross JJ. Childhood trauma and current psychological functioning in adults with social anxiety disorder. Journal Of Anxiety Disorders. 2011;25(4):467–473. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2010.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laurent J, Catanzaro SJ, Joiner Tr, Rudolph KD, Potter KI, Lambert S, … Gathright T. A measure of positive and negative affect for children: Scale development and preliminary validation. Psychological Assessment. 1999;11(3):326–338. [Google Scholar]

- Lejuez CW, Daughters SB, Danielson CW, Ruggiero K. The behavioural indicator of resilience to distress (BIRD) 2006 Unpublished manual. [Google Scholar]

- Leyro TM, Zvolensky MJ, Bernstein A. Distress tolerance and psychopathological symptoms and disorders: A review of the empirical literature among adults. Psychological Bulletin. 2010;136(4):576. doi: 10.1037/a0019712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little RJA. A test of missing completely at random for multivariate data with missing values. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1998;83:1198–1202. [Google Scholar]

- Little RJ, Rubin DB. The analysis of social science data with missing values. Sociological Methods & Research. 1989;18(2–3):292–326. [Google Scholar]

- Livheim F, Hayes L, Ghaderi A, Magnusdottir T, Högfeldt A, Rowse J, … Tengström A. The effectiveness of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy for adolescent mental health: Swedish and Australian pilot outcomes. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2015;24(4):1016–1030. [Google Scholar]

- MacPherson L, Reynolds EK, Daughters SB, Wang F, Cassidy J, Mayes LC, Lejuez CW. Positive and negative reinforcement underlying risk behavior in early adolescents. Prevention Science. 2010;11(3):331–342. doi: 10.1007/s11121-010-0172-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHugh RK, Daughters SB, Lejuez CW, Murray HW, Hearon BA, Gorka SM, Otto MW. Shared variance among self-report and behavioral measures of distress tolerance. Cognitive Research and Therapy. 2010 doi: 10.1007/s10608-010-9295-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mills R, Scott J, Alati R, O’Callaghan M, Najman JM, Strathearn L. Child maltreatment and adolescent mental health problems in a large birth cohort. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2013;37(5):292–302. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2012.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal R, Rosnow RL, Rubin DB. Contrasts and effect sizes in behavioral research: A correlational approach. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Roza SJ, Hofstra MB, van der Ende J, Verhulst FC. Stable prediction of mood and anxiety disorders based on behavioral and emotional problems in childhood: a 14-year follow-up during childhood, adolescence, and young adulthood. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2003;160(12):2116–2121. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.12.2116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider R, Baumrind N, Kimerling R. Exposure to child abuse and risk for mental health problems in women. Violence And Victims. 2007;22(5):620–631. doi: 10.1891/088667007782312140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shankman SA, Klein DN. The relation between depression and anxiety: An evaluation of the tripartite, approach-withdrawal and valence-arousal models. Clinical Psychology Review. 2003;23:605–637. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(03)00038-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi L. Childhood abuse and neglect in an outpatient clinical sample: Prevalence and impact. American Journal of Family Therapy. 2013;41(3):198–211. [Google Scholar]

- Simon NM, Herlands NN, Marks EH, Mancini C, Letamendi A, Li Z, … Stein MB. Childhood maltreatment linked to greater severity and poorer quality of life and function in social anxiety disorder. Depression And Anxiety. 2009;26(11):1027–1032. doi: 10.1002/da.20604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons JS, Gaher RM. The Distress Tolerance Scale: Development and validation of a self-report measure. Motivation and Emotion. 2005;29(2):83–102. [Google Scholar]

- Telch MJ, Jacquin K, Smits JJ, Powers MB. Emotional responding to hyperventilation as a predictor of agoraphobia status among individuals suffering from panic disorder. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry. 2003;34(2):161–170. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7916(03)00037-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tonmyr L, Williams G, Hovdestad WE, Draca J. Anxiety and/or depression in 10–15-year-olds investigated by child welfare in Canada. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2011;48(5):493–498. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]