Abstract

OBJECTIVES

The vestibular system allows the perception of position and motion and its dysfunction presents as motion impairment, vertigo and balance abnormalities, leading to debilitating psychological discomfort and difficulty performing daily tasks. Although declines and deficits in vestibular function have been noted in rats exposed to lead (Pb) and in humans exposed to Pb and cadmium (Cd), no studies have directly examined the pathological and pathophysiological effects upon the vestibular apparatus of the inner ear.

METHODS

Eighteen young adult mice were exposed through their drinking water (3 mM Pb, 300 μM Cd, or a control treatment) for 10 weeks. Before and after treatment, they underwent a vestibular assessment, consisting of a rotarod performance test and a novel head stability test to measure the vestibulocolic reflex. At the conclusion of the study, the utricles were analyzed immunohistologically for condition of hair cells and nerve fibers.

RESULTS

Increased levels of Pb exposure correlated with decreased head stability in space; no significant decline in performance on rotarod test was found. No damage to the hair cells or the nerve fibers of the utricle was observed in histology.

CONCLUSIONS

The young adult CBA/CaJ mouse is able to tolerate occupationally-relevant Pb and Cd exposure well, but the correlation between Pb exposure and reduced head stability suggests that Pb exposure causes a decline in vestibular function.

Keywords: Environmental exposure, lead, cadmium, vestibular function, head stability, mouse, ototoxicity

INTRODUCTION

The vestibular system allows the perception of position and motion in space and provides major sensory inputs for control of head and body posture. The structure is well-conserved in vertebrates and some invertebrates (Graf 2009), consisting of the utricle, the saccule, and three semi-circular canals containing a sensory ampulla each.. Spatial information is detected by hair cells (HCs), topped with stereociliary bundles and a kinocilium, which hyperpolarize or depolarize in response to motion and gravity (Highstein et al., 2004). Dysfunction of the vestibular system typically manifests as sensations of vertigo and instability, imbalance, and unusual changes in gait (Highstein et al., 2004). Vestibular dysfunction can be very detrimental to quality of life and psychosocial well-being, leading to decreased physical fitness, difficulty in concentration, depression, and socioeconomic decline (Patatas et al., 2009). Vestibular dysfunction can have a range of causes, which include age (Ishiyama 2009), infection, auto-immune disease, Meniere’s disease, and ototoxicity (Xie et al., 2011). Clinically and in animal studies, vestibular dysfunction is commonly assessed and diagnosed indirectly by measuring vestibular reflexes, which stabilize the eyes and head in space.

Several epidemiological studies have established that industrial exposure to Pb correlates with postural and balance deficits in children and adults (Bhattacharya et al., 2006; Iwata et al., 2005), and with decreases in walking speed (Ji et al., 2013). Cd frequently co-occurs with Pb, and higher blood levels for both metals were associated with poorer performance in balance tests (Min et al., 2012). Exposing rats for 90 days, beginning when they were 7 weeks of age, to 0.15 mM Pb caused a gradual decline in the vestibuloocular reflex (VOR), which stabilizes the eyes in space (Mameli et al. 2001). Collectively, these studies suggest that heavy metals affect the vestibular system, presumably through their general neurotoxicity.

The current study sought to characterize pathological changes in the vestibular system after Pb and Cd exposure by performing functional tests in vivo as well as histological examinations of vestibular tissue. We hypothesized that the damage induced to the animals’ vestibular systems would be detectible by appropriate functional tests, even in the absence of overt changes in behavior. In addition to the physiological assessment, we examined the HCs and neurofilaments of the vestibular sensory epithelia.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

All animal protocols were reviewed and approved by the University of Michigan University Committee on the Use and Care of Animals. Two cohorts, each consisting of nine four-week old male CBA/CaJ mice, were purchased from Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). The two-cohort approach was adopted in order to stagger testing dates and streamline the design. CBA/CaJ mice have vestibular systems that functionally decline with age much like that of a human (Mock et al., 2011), and are considered to be the “gold standard” for normal hearing among inbred mouse strains (Zheng et al. 1999; Gao et al. 2004). Females were excluded from previous studies because the estrus cycle is known to cause changes in hearing (Charitidi et al. 2012); the anatomical connection to the vestibular system may make it sensitive to such changes as well. Over the course of the experiment, the mice were housed three per cage to create equal groups for each exposure condition in a temperature- and light-controlled containment facility and allowed ad libitum access to water and standard mouse chow.

After their arrival, animals were given a one-week acclimation period. Implant surgery and baseline assessment, described in detail below, were completed over the course of four weeks to allow proper recovery time. The ten-week treatment period then began, during which the animals were exposed to Pb or Cd through their drinking water. After completion of the treatment period, and a three-day clearance period, the animals completed a second assessment, which took only two weeks, since surgery was not involved. Finally, the animals were sacrificed at 21 weeks of age, and their utricles, the most easily studied vestibular sensory organs, were harvested for histological analysis.

Vestibular Assessment Protocol

The vestibular function of the animals was assessed using two tests. The rotarod test, a measure of overall balance and neuromuscular function, involved placement of mice on a rod in an enclosed housing that began rotating at 5 rpm and accelerated at a rate of 0.1 rpm/s. The length of time the animals were able to remain on the device before dropping onto the instrumented floor of the housing was displayed on a timer and recorded after each test run (Jones and Roberts 1968). Each testing session consisted of 3 consecutive runs, after which the animals were returned to their housing area for at least two hours before another testing session; a total of 3 testing sessions were conducted.

The second test was a novel method based on assessment of the vestibulocollic reflex (VCR), a 3-neuron reflex arc similar to the vestibuloocular reflex (VOR) except the head, rather than the eye, is stabilized in space. Head movements were measured with a motion sensor (IMU) that detects angular velocity and linear acceleration. The IMU tracks acceleration and velocity of the head in space along three orthogonal axes (e.g., forward/backward, side-to-side, and up-down), as well as rotation around these axes (commonly referred to as pitch, yaw, and roll). A small post (0.02 g) was implanted onto the top of each animal’s head, which allowed the IMU to be attached during testing. To assess head stability, the animal was placed in a darkened 30 cm by 30 cm cubic arena located in a soundproof booth and allowed to move freely with the device attached. Head motion was then sampled at 1 kHz for five minutes. The amount and direction of measured head motion was considered indicative of VCR function (Godin et al. 2015; Lee et al. 2015).

Vestibular testing was performed before and after the treatment period to assess potential changes in vestibular function. We opted to exclude a positive control treatment group to confirm the sensitivity of the head stability test compared to the rotarod based on the results of previously published studies that used the VCR assessment to evaluate vestibular function (Godin et al. 2015; Lee et al. 2015), and which determined that vestibular dysfunction corresponds to significant changes in head motion.

Chemicals and Treatment

Nitric acid and a 2% w/v lead acetate stock solution were purchased from Fisher Scientific International, Inc. (Hampton, NH), and a 1 M cadmium chloride stock solution was purchased from VWR International (Radnor, PA). Purified water was prepared using a MilliQ system from EMD Millipore (Billerica, MA).

Cages were randomly assigned to a 3 mM Pb treatment, a 300 μM Cd treatment, or a metal-free control treatment, delivered through their drinking water over the course of 10 weeks. The oral ingestion route was chosen over air inhalation because of its public health relevance and as the more practical procedure. The treatment conditions had been previously established to represent potential occupational exposures to these metals; a multi-dose pilot study in our laboratory had demonstrated that these doses were high enough to potentially result in ototoxicity while low enough to avoid frank systemic toxicity (data not shown; manuscript in preparation). All treatment solutions were prepared in 4 L batches of purified and deionized water and transferred into acid-washed water bottles in a cleanroom. Control treatment consisted of only purified water; Pb and Cd treatments were prepared from stock solutions. During the treatment period, animals were weighed weekly to ensure the metal levels were not causing overt toxicity. Before the post-treatment assessment, the animals were allowed a three-day clearance period to reduce concentrations of Pb or Cd in their blood and urine so that equipment was not contaminated.

Sacrifice and Histology

After the post-treatment assessment, the animals were anesthetized and decapitated. The bulla was immediately harvested, placed in paraformaldehyde, and perfused. The utricle was dissected out and stored in phosphate-buffered saline solution in a cold room. The right tibia of each mouse was also harvested, cleaned, dissolved in 375 μL of trace metal grade nitric acid (Fisher Scientific), and sent to the Michigan Department of Community Health for inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) analysis to measure the dose of Pb and Cd each animal had received.

The left utricle from each animal was stained with antibodies for myosin VIIa, to detect HCs, and neurofilaments, to assess nerve fibers and calyx-type nerve endings surrounding Type I HCs. Briefly, the dissected tissues were permeabilized using 0.3% Triton X-100, followed by blocking in normal goat serum (NGS). The primary antibodies, rabbit anti-myosin VIIa (Proteus 25-6791) and mouse anti-neurofilament (Millipore/Chemicon AB9563), were applied simultaneously for one hour. The secondary antibodies, fluorescently labeled goat anti-rabbit AF594 and goat anti-mouse AF488 (Invitrogen/Molecular Probes, Carlsbad, CA) were applied simultaneously for 30 minutes. The tissues were then whole-mounted onto a slide and stored in a cold-room until analysis.

Analyses

Descriptive statistics were computed for all data collected. Rotarod data were analyzed using a mixed models analysis in SPSS Statistics (IBM, Armonk, New York). Time was modeled using several variables, including run number, test number, treatment received, and whether the mouse was in the pre- or post-exposure phase. All of these temporal variables were treated as fixed effects. Mouse number was entered into the model as a random effect to account for the repeated measurements made on each animal.

Head movement data collected from the IMU was exported to MatLab (The MathWorks, Inc., Natick, MA), and averaged into 100 ms blocks. The average and standard deviation of the X, Y, and Z components of head angular velocity and linear acceleration were computed across each block. In addition, the mean and standard deviation of the vector magnitude of head angular velocity and linear acceleration were computed for each block. Individual bone metal levels within each exposure group were compared to these measures using linear regression. Additionally, a Kruskal-Wallis test was used to assess the difference in variance of overall magnitude of angular head velocity and linear acceleration averaged over each test date before and after the exposure period. The magnitude data were averaged over each test date, so there is one value for each mouse and each day of testing.

The whole-mounted utricles were visually examined using a Leica DMRB epi-fluorescence microscope (Leica, Eaton, PA). Images were photographed with a SPOT-RT digital camera (Diagnostic Instruments, Sterling Heights, MI) and the resultant images were processed with Adobe Photoshop (Adobe Systems, San Jose, CA). If regions of potential HC or neurofilament loss were observed, counts were made.

RESULTS

Sacrifice and Bone Analysis

All animals (n = 18) survived until sacrifice with normal weight gain and no overt behavioral detriment following treatment. Inner ear organs and tibias were successfully harvested from all animals; however, 2 utricles were lost during staining, and 2 more were mislabeled during mounting (valid n = 14).

The tibias showed detectible levels of Pb in all animals, and levels were higher in Pb-treated animals (178 mg/kg, SD = 12) than in control- or cadmium-treated animals (0.29 mg/kg, SD = 0.06 and 0.24 mg/kg, SD = 0.07, respectively, Table 1). Cd was detected only in animals that had been exposed to Cd, with a mean level of 0.15 mg/kg (SD = 0.01).

Table 1.

Pb and Cd levels in the bone

| Group | Tissue/Metal | N | Mean | Standard Deviation | Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pb-Exposure | Bone Pb (mg/kg) | 6 | 178 | 12 | 160 – 190 |

| Bone Cd (mg/kg) | < LoDa | N/A | All < LoD | ||

| Cd-Exposure | Bone Pb (mg/kg) | 6 | 0.24 | 0.07 | 0.17 – 0.27 |

| Bone Cd (mg/kg) | 0.15 | 0.01 | 0.13 – 0.17 | ||

| Control | Bone Pb (mg/kg) | 6 | 0.29 | 0.06 | 0.23 – 0.39 |

| Bone Cd (mg/kg) | < LoD | N/A | All < LoD |

Limit of detection for Cd was 0.05 mg/kg

Vestibular assessment

Rotarod data suggested a decline in performance post-exposure for all animals in the first cohort, with a non-significant trend towards a change among Pb- and Cd-exposed animals compared to controls. However, the second cohort of animals unexpectedly demonstrated an improved post-exposure performance on the rotarod, particularly among Cd-exposed animals (Table 2). A comparison of the two cohorts showed that the first cohort had a higher baseline performance than the second (p = 0.004). Mixed model analysis (Table 3) showed no significant relationship between treatment group and rotarod performance. Significant effects were limited to the test number (p < 0.001) and to the variable assigned to indicate pre- or post-exposure tests (p = 0.002).

Table 2.

Time on rotarod (sec)

| Time period | Exposure group | Overall (n=6)

|

Cohort 1 (n= 3)

|

Cohort 2 (n=3)

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||

| Baseline | Pb-exposed | 56.5 | 14.3 | 76.8 | 15.5 | 36.2 | 15.0 |

| Cd-exposed | 52.7 | 6.1 | 63.9 | 4.4 | 41.6 | 10.6 | |

| Control | 48.3 | 16.0 | 53.6 | 9.8 | 42.9 | 23.7 | |

| Post-treatment | Pb-exposed | 35.4 | 5.4 | 26.8 | 9.0 | 44.5 | 4.6 |

| Cd-exposed | 48.0 | 14.6 | 18.7 | 9.5 | 77.3 | 20.5 | |

| Control | 40.5 | 11.1 | 32.1 | 15.3 | 48.9 | 8.5 | |

| Change from baseline | Pb-exposed | 21.1 | 38.2 | 50.2 | 32.3 | -8.1a | 7.4 |

| Cd-exposed | 4.7 | 50.0 | 45.0 | 14.9 | -35.7 | 34 | |

| Control | 5.4 | 23.2 | 17.1 | 13.2 | -6.2 | 27.6 | |

negative change from baseline indicates an improved performance

Table 3.

Mixed models significance (p-value) of fixed variables and their effect on time on rotarod

| Variable | Significance in Overall Model | Significance in Cohort 1 Model | Significance in Cohort 2 Model |

|---|---|---|---|

| Test number | < 0.001 | 0.021 | < 0.001 |

| Run number | 0.954 | 0.941 | 0.945 |

| Pre/Post exposure | 0.002 | < 0.001 | 0.001 |

| Treatment received | 0.851 | 0.743 | 0.562 |

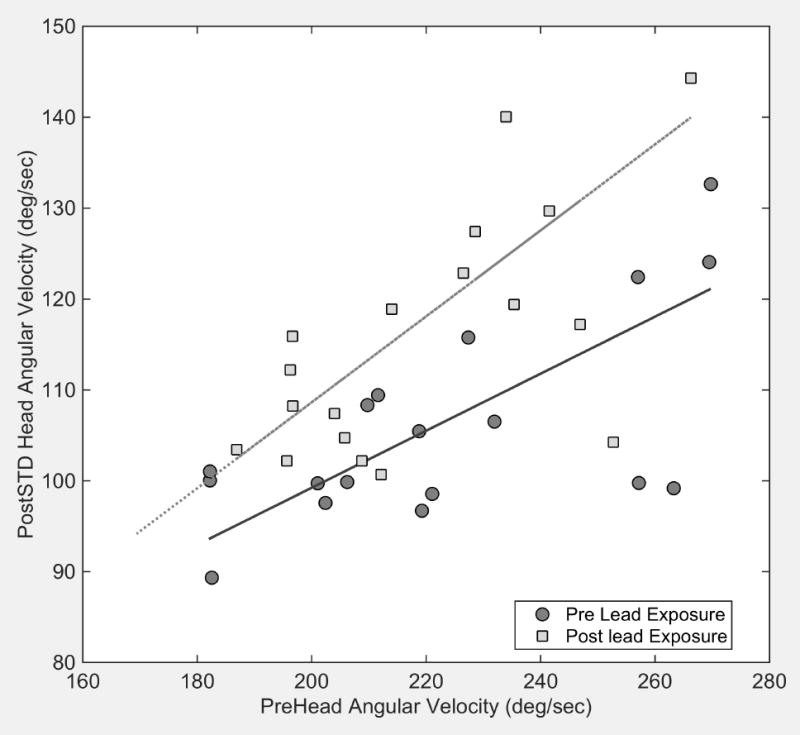

Head stability data showed significant increases in the variability of angular head velocity and a decrease in the magnitude of linear head acceleration in animals exposed to lead (Figure 1). Results of one way ANOVA on ranks confirmed the significance of the increased variance in head angular velocity among Pb-exposed animals (Kruskal-Wallis = 0.014) and the decreased linear head acceleration (Kruskal-Wallis = 0.005). There was no significant change in the magnitude of angular head velocity (Kruskal-Wallis = 0.45) or in the variability of linear head acceleration (Kruskal=Wallis = 0.85) in lead exposed animals. There were no statistically significant changes in these measures in Cd exposed or control animals.

Figure 1.

Greater variability of angular head velocity is associated with larger magnitudes of angular head velocity in pre exposed mice (dark gray circles). The solid line is a linear regression of these data (slope=0.31, r2=0.66). Following exposure to lead, the variance of angular head velocity is increased (light gray squares) relative to pre exposure values in the same mice as shown by the linear regression of the post exposure data (gray dashed line, slope=0.47, r2=0.75)

In order to determine if there was a relationship between bone metal deposits and head stability, we normalized each animal’s head velocity and acceleration by dividing post-exposure values by pre-exposure values. Among Pb-exposed animals, linear regression demonstrated a significant correlation between the average deviation of normalized head angular velocity and bone Pb levels (p = 0.038). There was no correlation between normalized head linear acceleration and lead exposure (p=0.11). No correlations were found between head stability data and individual Cd exposure (p=0.4, angular velocity; p=0.2 linear acceleration).

Histology

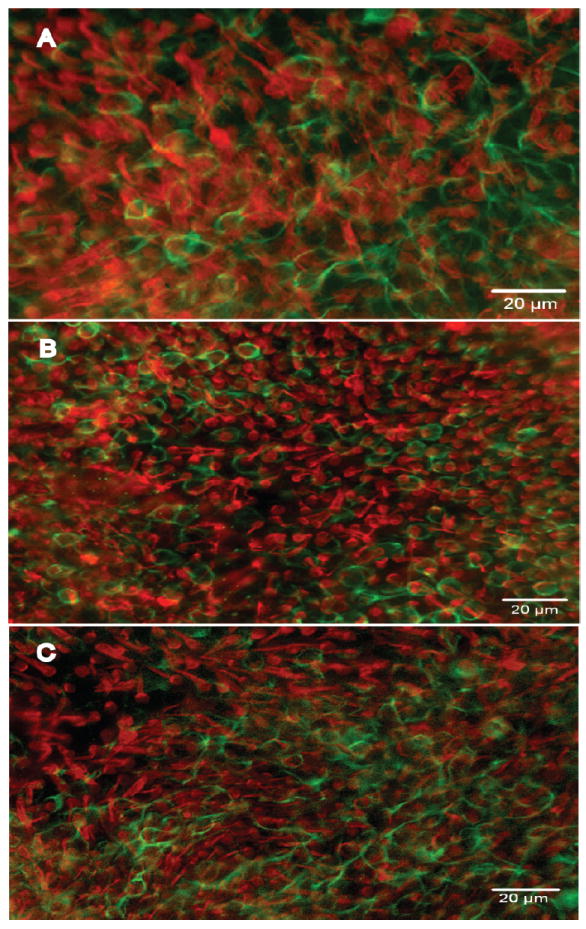

Histological examination did not show vestibular HC loss. The distribution of calyx type nerve endings was similar in control and experimental animals (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Whole-mounts of utricles stained with antibodies to myosin VIIa (red) and neurofilament (green) viewed with epi-fluorescence. A. A normal (control) utricle displaying a confluent population of HCs. Rings of neurofilament around HCs denote a calyx-type nerve endings surrounding type I HCs. B-C. Utricles from animals treated with cadmium (B) and lead (C) in which the density of HCs and calyx-type nerve endings is similar to control.

DISCUSSION

Our study has revealed vestibular deficits in CBA mice exposed to occupationally-relevant doses of lead. These deficits, which are highly relevant for human pathophysiology, were unmasked via a newly developed multi-axis test of head stability (Godin et al. 2015; Lee et al. 2015), but not by a common but less specific test of vestibular function, the rotarod. The deficits observed in the head stability tests were greater among animals that received higher Pb exposures, and correlated with individual bone Pb levels. The significance of the correlation between head angular velocity and bone Pb levels indicates that Pb exposure may decrease the mouse’s ability to stabilize its head in space. For humans, a correlate of this deficit would be poorer reflex control of head position in space and possible postural instability and increased risk of falling. HC loss was not observed in the utricles, but it is possible that ultrastructural analysis might reveal changes at the level of the epithelium or the neural components of the utricles or other vestibular end organs that would account for the functional changes.

The absence of any robust effect of metal exposure on rotarod performance suggests that the relatively non-specific rotarod test of neuromuscular performance may not be suitable for assessing subtle vestibular deficits. The effect observed in the head stability test was small enough that it was unlikely to cause changes in overall physical coordination, and could therefore be compensated for by vision in lighted environments (e.g., during the rotarod test) or other compensation processes within the central nervous system.

Our study is consistent with and extends the existing literature. Bhattacharya et al (2006) and Iwata et al (2005) reported increased postural sway among individuals with higher levels of Pb exposure, much like the head stability correlation found in our mice. Similarly, Mameli et al. (2001) demonstrated that Pb exposure through drinking water causes a decline in the VOR of rats. We have demonstrated that the VCR is also subject to decline in mice treated with Pb in drinking water – an important extension to a species with a greater availability of transgenic strains and molecular tools. Oral delivery of Pb (e.g., through drinking water, food, or ingested dust) is a relevant occupational and public health exposure model, given the well-known problems with Pb contamination in some public (Hanna-Attisha et al. 2015) and private (Pieper et al. 2015) drinking water supplies in the US, as well as ingestion of leaded paint and other materials by children (Levin et al. 2008) and ingestion of lead dust or handling of food with lead-contaminated hands by workers (Sato and Yano 2006). Inhalation delivery of Pb, as would be appropriate to model certain occupational exposures in the US (Kim et al. 2015), has been used in some mouse models previously (Valverde et al. 2002; Bizarro 2003), but not with CBA mice.

Results in our mouse model differ from the findings in humans by Min et al. (2012) that suggested that Cd exposure was associated with vestibular deficits . The discrepancy may indicate possible uncontrolled confounding factors in the NHANES data analyses reported by Min et al. On the other hand, rodents may also be more resistant to the effects of Cd; inter-species differences have already that suggest increased ototoxicity of chemotherapeutic agents (Sockalingam et al. 2000), antibiotics (Meza and Aguilar-Maldonado 2007), and industrial solvents (Cappaert et al. 2002; Gagnaire et al. 2007) in guinea pigs compared to rats.

The VCR is more easily measured in a rodent model than the VOR, and our study found that the head stability test is a useful method for assessing changes in vestibular function, even in cases of subtle decline. This may aid future research by simplifying methodology, and may also have important clinical ramifications for assessment of subclinical vestibular damage.

Limitations

CBA/CaJ mice were selected as a standard strain for inner ear research (Mock et al. 2011). Furthermore, they are robust and remain in good health into advanced age. To the best of our knowledge, different mouse strains have not been compared for their sensitivity to heavy metals in terms of vestibular toxicity or, more general, changes in peripheral nerve conduction velocity. It therefore remains open whether this strain is more vulnerable or more resistant to vestibular effects from exposure to Pb or Cd than other rodents.

The histological examination conducted as part of this experiment found no changes in overall appearance of the utricle surface, but it is possible that subtle changes in HC morphology, loss of calyx type nerve endings, or changes in peripheral synaptic efficacy occurred but were not identified by our methodology. While decreased head stability is consistent with utricle involvement, it remains possible that additional toxicity may have occurred elsewhere in the vestibular system, such as the other tissues of the vestibular apparatus or the neural pathways that comprise the vestibular reflexes.

We found detectable Pb levels in the bones of animals not intentionally exposed. This occurred in spite of the use of purified water and acid-washed bottles, and may indicate exposure prior to arrival at the University of Michigan or contamination from the following sources: metal drinking spouts that were attached to the water bottles, which could not be acid washed; contaminated animal feed; pre-experimental exposure; exposure through non-purified drinking water during the clearance period. Exposure to airborne lead seems unlikely given the time spent in the closely-controlled animal handling facility with only brief periods when the animals were assessed in unfiltered ambient building air. While detected levels were not significant compared with the intentional exposures, this finding does emphasize the importance of comprehensively evaluating potential sources of contamination, and indicates that testing of samples of animal food and water supplies, as well as ambient air, to ensure it is free from heavy metals is warranted.

In summary, our study demonstrates Pb-induced vestibulotoxicity in the adult mouse, and suggests the need forfollow-up studies on vestibular ototoxicity. For example, age affects the inner ear, as amply documented in vestibular and auditory dysfunction in both the aging human population and animal models (Ishiyama 2009; Mock et al. 2011). Whether age alters the susceptibility of the vestibular system to Pb toxicity has not yet been evaluated, however. Furthermore, it is important for health prognosis and rehabilitation to assess the permanence of any vestibular changes induced by temporary exposure to heavy metals. Two mechanisms may come into play: the compensation by the vestibular apparatus to injuries, and the limited ability of the peripheral tissues for regeneration. It is therefore possible that once exposure has ceased, the vestibular system could begin recovery. Again, such recovery processes might be age-dependent and it would be valuable to know whether early life exposures are more or less likely to cause lasting damage.

CONCLUSIONS

This study detected a change in head stability in space and revealed a correlation between the variance of an animals’ head angular velocity and the individual Pb exposure measured from its bones, findings associated with vestibular dysfunction. In contrast, histological examination of the utricle did not show any lesions. This result suggests that Pb exposure compromises vestibular function in subtle ways that might not be detectable using conventional or relatively insensitive assessment methods. Further evaluation of the VCR subsequent to Pb exposure is warranted based on our findings.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Krystin Carlson, Ann Kendall, Jonie Dye, Ashley Godin, and Kan Sun for their assistance. Supported by the R. Jamison and Betty Williams Professorship and NIH/NIDCD Grants R03DC013378, R01-DC010412, R01-DC011294 and P30-DC05188.

Contributor Information

Katarina E. M. Klimpel, University of Michigan Department of Environmental Health Sciences, Ann Arbor, MI USA

Min Young Lee, Kresge Hearing Research Institute, Department of Otolaryngology - Head and Neck Surgery, University of Michigan Medical School, Ann Arbor, MI USA

W. Michael King, Kresge Hearing Research Institute, Department of Otolaryngology - Head and Neck Surgery, University of Michigan Medical School, Ann Arbor, MI USA

Yehoash Raphael, Kresge Hearing Research Institute, Department of Otolaryngology - Head and Neck Surgery, University of Michigan Medical School, Ann Arbor, MI USA

Jochen Schacht, Kresge Hearing Research Institute, Department of Otolaryngology - Head and Neck Surgery, University of Michigan Medical School, Ann Arbor, MI USA.

Richard L. Neitzel, University of Michigan Department of Environmental Health Sciences, Ann Arbor, MI USA.

References

- Bhattacharya A, Shukla R, Dietrich KN, Bornschein RL. Effect of early lead exposure on the maturation of children’s postural balance: A longitudinal study. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2006;28:376–85. doi: 10.1016/j.ntt.2006.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bizarro P. Ultrastructural modifications in the mitochondrion of mouse Sertoli cells after inhalation of lead, cadmium or lead–cadmium mixture. Reprod Toxicol. 2003;17:561–566. doi: 10.1016/s0890-6238(03)00096-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cappaert NLM, Klis SFL, Muijser H, Kulig BM, Ravensberg LC, Smoorenburg GF. Differential susceptibility of rats and guinea pigs to the ototoxic effects of ethyl benzene. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2002;24:503–10. doi: 10.1016/s0892-0362(02)00208-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charitidi K, Meltser I, Canlon B. Estradiol treatment and hormonal fluctuations during the estrous cycle modulate the expression of estrogen receptors in the auditory system and the prepulse inhibition of acoustic startle response. Endocrinology. 2012;153:4412–21. doi: 10.1210/en.2012-1416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gagnaire F, Marignac B, Blachère V, Grossmann S, Langlais C. The role of toxicokinetics in xylene-induced ototoxicity in the rat and guinea pig. Toxicology. 2007;231:147–58. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2006.11.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao J, Wu X, Zuo J. Targeting hearing genes in mice. Molecular Brain Research. 2004;132:192–207. doi: 10.1016/j.molbrainres.2004.06.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godin A, Dye J, Brewer S, Takada Y, Lee MY, Swiderski D, Raphael Y, King WM. Head stability during natural locomotion: quantitative peripheral vestibular assessment in rodents. Association for Research in Otolaryngology Annual Midwinter Meeting; Baltimore, MD, USA. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Graf WM. Evolution of the Vestibular System. In: Binder Marc D, Hirokawa Nobutaka, Windhorst Uwe., editors. Encyclopedia of Neuroscience. Berlin Heidelberg: Springer; 2009. pp. 1440–48. [Google Scholar]

- Hanna-Attisha M, LaChance J, Sadler RC, Champney Schnepp A. Elevated Blood Lead Levels in Children Associated With the Flint Drinking Water Crisis: A Spatial Analysis of Risk and Public Health Response. Am J Public Health. 2015:e1–e8. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2015.303003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Highstein SM, Fay RR, Popper AN. The Vestibular System. New York: Springer; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Ishiyama G. Imbalance and vertigo: The aging human vestibular periphery. Semin Neurol. 2009;29:491–99. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1241039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwata T, Yano E, Karita K, Dakeishi M, Murata K. Critical dose of lead affecting postural balance in workers. Am J Ind Med. 2005;48:319–25. doi: 10.1002/ajim.20220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji JS, Elbaz A, Weisskopf MG. Association between Blood Lead and Walking Speed in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES 1999–2002) Environ Health Perspect. 2013:711–16. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1205918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones BJ, Roberts DJ. The quantiative measurement of motor inco-ordination in naive mice using an acelerating rotarod. J Pharm Pharmacol. 1968;20:302–04. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-7158.1968.tb09743.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H-C, Jang T-W, Chae H-J, Choi W-J, Ha M-N, Ye B-J, Kim B-G, Jeon M-J, Kim S-Y, Hong Y-S. Evaluation and management of lead exposure. Ann Occup Environ Med. 2015;27:30. doi: 10.1186/s40557-015-0085-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee MY, Takada T, Takada Y, Kappy MD, Beyer LA, Swiderski DL, Godin AL, Brewer S, King WM, Raphael Y. Mice with conditional deletion of Cx26 exhibit no vestibular phenotype despite secondary loss of Cx30 in the vestibular end organs. Hear Res. 2015;328:102–12. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2015.07.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin R, Brown MJ, Kashtock ME, Jacobs DE, Whelan EA, Rodman J, Schock MR, Padilla A, Sinks T. Lead exposures in U.S. children, 2008: Implications for prevention. Environ Health Perspect. 2008;116:1285–1293. doi: 10.1289/ehp.11241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mameli O, Caria MA, Melis F, Solinas A, Tavera C, Ibba A, Tocco M, Flore C, Sanna Randaccio F. Neurotoxic effect of lead at low concentrations. Brain Research Bulletin. 2001;55:269–75. doi: 10.1016/s0361-9230(01)00467-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meza G, Aguilar-Maldonado B. Streptomycin action to the mammalian inner ear vestibular organs: comparison between pigmented guinea pigs and rats. Comp Biochem Physiol C Toxicol Pharmacol. 2007;146:203–6. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpc.2006.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Min K-B, Lee K-J, Park J-B, Min J-Y. Lead and cadmium levels and balance and vestibular dysfunction among adult participants in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 1999-2004. Environ Health Perspect. 2012;120:413–7. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1103643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mock B, Jones T, Jones SM. Gravity receptor aging in the CBA/CAJ strain: A comparison to auditory aging. JARO - J Assoc Res Otolaryngol. 2011;12:173–83. doi: 10.1007/s10162-010-0247-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patatas OHG, Ganança CF, Ganança FF. Quality of life of individuals submitted to vestibular rehabilitation. Brazilian J Otorhinolaryngol. 2009;75:387–94. doi: 10.1016/S1808-8694(15)30657-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pieper KJ, Krometis L-A, Gallagher D, Benham B, Edwards M. Profiling Private Water Systems to Identify Patterns of Waterborne Lead Exposure. Environ Sci Technol. 2015;49:12697–704. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.5b03174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato M, Yano E. The association between lead contamination on the hand and blood lead concentration: A workplace application of the sodium sulphide (Na2S) test. Sci Total Environ. 2006;363:107–113. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2005.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sockalingam R, Freeman S, Cherny TL, Sohmer H. Effect of high-dose cisplatin on auditory brainstem responses and otoacoustic emissions in laboratory animals. Am J Otol. 2000;21:521–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valverde M, Fortoul TI, Díaz-Barriga F, Mejía J, del Castillo ER. Genotoxicity induced in CD-1 mice by inhaled lead: differential organ response. Mutagenesis. 2002;17:55–61. doi: 10.1093/mutage/17.1.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie J, Talaska AE, Schacht J. New developments in aminoglycoside therapy and ototoxicity. Hear Res. 2011;281:28–37. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2011.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng QY, Johnson KR, Erway LC. Assessment of hearing in 80 inbred strains of mice by ABR threshold analyses. Hear Res. 1999;130:94–107. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(99)00003-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]