Abstract

Objective

To assess how easily minors can purchase cigarettes online and online cigarette vendors’ compliance with federal age/ID verification and shipping regulations, North Carolina’s 2013 tobacco age verification law, and federal prohibitions on the sale of non-menthol flavoured cigarettes or those labelled or advertised as light’.

Methods

In early 2014, 10 minors aged 14–17 attempted to purchase cigarettes by credit card and electronic check from 68 popular internet vendors.

Results

Minors received cigarettes from 32.4% of purchase attempts, all delivered by the US Postal Service (USPS) from overseas sellers. None failed due to age/ID verification. All failures were due to payment processing problems. USPS left 63.6% of delivered orders at the door with the remainder handed to minors with no age verification. 70.6% of vendors advertised light cigarettes and 60.3% flavoured, with 23.5% and 11.8%, respectively, delivered to the teens. Study credit cards were exposed to an estimated $7000 of fraudulent charges.

Conclusions

Despite years of regulations restricting internet cigarette sales, poor vendor compliance and lack of shipper and federal enforcement leaves minors still able to obtain cigarettes (including light’ and flavoured) online. The internet cigarette marketplace has shifted overseas, exposing buyers to widespread credit card fraud. Federal agencies should rigorously enforce existing internet cigarette sales laws to prevent illegal shipments from reaching US consumers, shut down non-compliant and fraudulent websites, and stop the theft and fraudulent use of credit card information provided online. Future studies should assess whether these agencies begin adequately enforcing the existing laws.

INTRODUCTION

Online cigarette sales have long been a public health and regulatory concern. Vendors often overtly advertise and normalise tax evasion strategies, depriving government of billions of dollars in annual tax revenue,1–3 undermining the public health benefits of higher taxes: reduced initiation, consumption and increased cessation.1,4–7

Furthermore, internet cigarette vendors (ICVs) have historically sold cigarettes without carefully verifying age.8,9 Prior to federal regulation, teens successfully bought cigarettes from 92% of vendors,10 and none complied with California’s ICV youth access law.11 Youth purchases from ICVs are widespread; a million adolescents had purchased cigarettes and other tobacco products online in 2012.12 Youth who buy cigarettes online are typically younger, with greater perceived difficulty obtaining cigarettes offline.13 Youth refused sales at retail stores are over three times more likely to buy online.14

The once burgeoning and unrestricted ICV industry has been subject to increasing levels of regulation in recent years. Following years of vendors clearly violating laws related to tax reporting and sales to minors, in 2005 ICVs were subject to federal agreements with credit card companies, PayPal, UPS, DHL and FedEx prohibiting participation in internet cigarette sales transactions.15–18 This was followed by the 2009 federal Prevent All Cigarette Trafficking (PACT) Act19 which expanded the shipping ban to US Postal Service (USPS) and required age verification with a public records database (PRD) at the point of order and with ID at delivery,20,21 cutting off most legal means of accepting payment for and shipping cigarettes to customers. In 2013, North Carolina joined other states requiring age verification for ICV sales,22 passing a law requiring age verification via PRD at the point of order for all tobacco products.23 The 2009 Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act (FSPTCA)24 provided Food and Drug Administration (FDA) with enforcement authority for ICV age verification,25,26 and also prohibited any sale of cigarettes labelled or advertised as ‘light’ or with any flavour other than tobacco or menthol.27,28

This is the first study to assess ICVs’ compliance with: (1) PACT Act’s age verification requirements and shipping restrictions, (2) North Carolina’s 2013 tobacco age verification law or (3) FSPTCA prohibitions on the sale of light and flavoured cigarettes. Our previous study of advertised compliance with FSPTCA prohibitions indicated that banned products were still widely available online (at 89% of vendors) in 2011.29 This is the first study to determine whether US teens can still successfully purchase banned products online.

METHODS

Sample

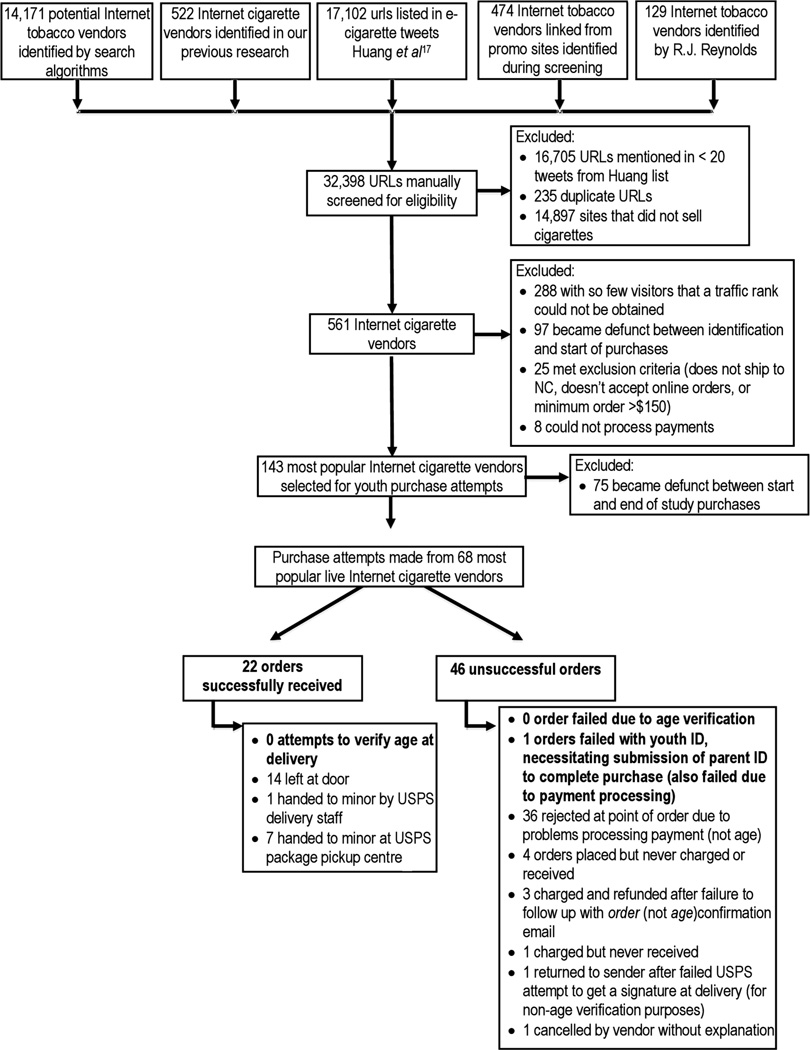

ICVs were identified from a concurrent study of the sales and marketing practices of internet tobacco vendors (ITVs). Figure 1 depicts study sampling procedures, purchase attempts and order results. The list of potential ITVs was compiled from five sources. The primary source was complex search algorithms, annually updated since 2004, searching over 180 million websites, message boards, newsgroups and spam emails, identifying 14 171 potential ITVs. Other sources included a study of Twitter data (17 102 URLs),30 prior waves of data collection by our team (522), sites linked from promotional sites identified during screening (474) and 129 sites provided by R.J. Reynolds. Ultimately, 32 398 URLs were manually screened for eligibility, resulting in the identification of 561 ITVs selling cigarettes for home delivery. Alexa.com website traffic rankings31 were used to select the most popular vendors for study inclusion, excluding 288 with so few visits among Alexa’s global user panel that a traffic estimate could not be created. Ninety-seven sites became defunct between identification and the start of study purchases, and 25 met additional exclusion criteria (did not ship to North Carolina, did not accept online orders or had a minimum order >$150, which would presumably be cost prohibitive to minors). Another eight were removed because they could not process payments. The remaining 143 popular ICVs were selected for purchase attempts. Some of those became defunct during the study, as described below.

Figure 1.

Sampling and order resolution for internet cigarette vendor youth purchase survey. NC, North Carolina; USPS, US Postal Service.

Buyers

Multiple buyers (10 14–17 years old) were employed to minimise the chances of delivery drivers’ age verification attempts becoming biased by increased recognition of recipients. Monitored phone numbers and email accounts were created for each buyer to avoid ICV correspondence being sent to their personal accounts. Letters of immunity from prosecution were obtained from the local district attorney and police chiefs to protect all staff and buyers involved in the study.

Study procedures

Between February and June 2014, under one-on-one staff supervision, using procedures approved by the University of North Carolina Institutional Review Board, buyers visited study websites, attempting to purchase one carton of each of the following products if available: Marlboro cigarettes (light if available), light cigarettes of another brand if Marlboro lights were unavailable and the cheapest brand of flavoured cigarettes, while staff monitored and tracked purchase details (including products purchased, cost, age verification attempts and delivery). Buyers attempted to purchase Marlboros due to their global popularity; and light and flavoured cigarettes were purchased to assess compliance with the FSPTCA bans. We tracked whether vendors used age verification at the point of order and/or age verification at delivery (AVAD). Where available, buyers chose USPS delivery to assess compliance with PACT Act’s USPS ban.

When encountering age verification, buyers were allowed to misrepresent their age and identity in several ways, including clicking checkboxes or typing false birth dates to bypass age verification. In one of our prior age verification studies (Williams RS, Lewis MJ, Ribisl KM. Effectiveness of age verification restrictions on tobacco company brand marketing websites. Under Review), the 20 teen participants all said they had easy access to their parents’ driver licences and no qualms about using them to bypass age verification, indicating that past internet purchase studies prohibiting teen buyers from using another’s identity almost certainly underestimated actual youth purchase success rates. To address this issue, we recruited youth buyers with a parent who gave written permission for their child to use their ID to attempt to bypass age verification. The legal definition of identity theft is using someone’s identity without their permission,32 so no laws were broken.

This also allowed for the first ever testing of ICVs’ use of challenge questions and their efficacy. Challenge questions verify that the submitter of an ID is the owner of the ID by asking multiple choice questions based on public records information that someone other than the owner would be unlikely to know, such as ‘Which model car did you own in 1993?’ When teens used their parent’s ID online, we could assess whether challenge questions were used, and when used, whether they blocked youth access.

Most purchases were made with credit cards issued in the name of each youth buyer and parent. A checking account was set up for one buyer to make purchases from the few vendors that accepted only electronic checks.

Buyers first attempted to make purchases using their own identity, and if they failed due to age verification, they made a follow-up attempt with their parent’s identity. They agreed to answer the door for deliveries when they were home, and to pick up packages at delivery centres as needed. When packages were delivered, buyers recorded the details of any age verification attempts at delivery. Staff regularly retrieved delivered packages from buyers’ homes.

RESULTS

Vendor attrition

During the study’s purchase phase, 75 ICVs became defunct, leaving 68 for actual purchase attempts. Including the 97 removed between identification and the start of the purchase study produces, an attrition rate of 30.6% (172 sites) of all ICVs identified becoming defunct during the 14 months between identification and study completion. This rate of attrition is comparable to ICV turnover found in previous years of study.33,34 It could be prompted by vendors choosing to close shop in the face of restrictive legislation, or from internet sellers simply discontinuing one website when faced with potential legal violations and starting another in another jurisdiction.

Products ordered and received: federal regulatory compliance

Figure 1 describes the entire process from initially identifying potential ICV websites through attempting purchases and subsequent results regarding orders and deliveries. After purchase attempts were completed, 46 more vendors appeared to be defunct (because they could not process payments, or did not charge the buyer and/or deliver products).

Table 1 describes the products ordered and received and compliance among ICVs with FSPTCA bans on light and flavoured cigarettes. Only three vendors complied with the 2005 ban on credit cards/PayPal for online cigarette sales,17 accepting only e-checks for payment.

Table 1.

Products ordered and received by teens from internet cigarette vendors (N=68) and compliance with the Family Smoking Prevention Tobacco Control Act (FSPTCA) bans on light and flavoured cigarettes

| Product | Orders attempted n | Orders received n |

|---|---|---|

| Marlboro Reds or Golds* | 39 | 7 |

| Marlboro Lights† | 24 | 10 |

| Other brand light cigarettes† | 28 | 7 |

| Flavoured cigarettes‡ | 41 | 8 |

No orders failed due to age verification; most failures were due to problems processing payment; specific details are provided in figure 1.

Sales of Marlboro Reds or Golds are in compliance with the FSPTCA’s ban on cigarettes with misleading descriptors such as ‘light’.

Marlboro or other brand cigarettes specifically identified on the vendor website or the packaging with ‘light’ or other misleading descriptors are in violation of the FSPTCA.

Any flavoured cigarettes sold were in violation of the FSPTCA ban on cigarettes with flavours other than tobacco or menthol.

Despite the bans, 70.6% of ICVs advertised light cigarettes and 60.3% advertised flavoured cigarettes in violation of the FSPTCA bans, and 23.5% and 11.8% of all vendors delivered light and flavoured cigarettes to teens, respectively. USPS delivered all packages, in violation of the PACT Act prohibition on shipping cigarettes to consumers. All received packages originated overseas.

Age verification

Of the 68 youth purchase attempts in this study, 22 were successfully received. As described in table 2, no orders failed due to age verification at the point of order, and there were no attempts to verify age at delivery—USPS carriers simply left 63.6% of received orders at the buyer’s door, and handed the remaining nine packages to teen buyers without verifying age. No packages were marked as containing cigarettes or were clearly in the shape of cigarette cartons (and therefore easily identifiable by USPS). The remaining 46 orders failed for reasons unrelated to age verification, primarily problems with the website processing payments (see figure 1). One unsuccessful order was returned to sender after the recipient failed to retrieve the package from the post office. While this presents a minor study limitation, it would have had a negligible effect on the results.

Table 2.

Age warnings and age verification strategies encountered at the point of order in internet cigarette purchase survey; strategies not mutually exclusive, some vendors used more than one (N=68)

| Strategy | Order attempts n (%) |

Buy rate* n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age warning on home page | 24 (35.3) | 10 (45.5) |

| No attempts to verify age at all | 13 (19.1) | 5 (22.7) |

| Age verification strategies that cannot effectively verify age |

31 (45.6) | 12 (54.5) |

| User clicks checkbox/button | 15 (22.1) | 6 (27.3) |

| Claim that ‘submitting order’ certifies age | 45 (66.2) | 12 (54.6) |

| Age verification strategies that could potentially block youth access |

24 (35.3) | 5 (22.7) |

| Date of birth | 23 (33.8) | 5 (22.7) |

| Claims to use online age verification service | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Site claims age verified at delivery | 1 (1.5) | 0 (0.0) |

| Sending a copy of driver licence | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Entering driver licence number | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Challenge questions | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Total | 68 | 22 (32.4) |

| Total excluding orders that failed for reasons unrelated to age verification |

22 | 22 (100) |

While the percentages in the order attempts column represent the per cent of all order attempts (from vendors N=68) that used each strategy, the ‘buy rate’ percentages represent successfully received orders (n=22) that used each youth access prevention strategy; for example, 22.7% of all order attempts that asked for date of birth were successfully received. All except the final row include orders that failed for reasons related to payment processing, not age verification.

While most vendors featured some form of age verification, 46% featured only token strategies that clearly cannot effectively verify age (such as a checkbox), and 19% featured no attempts to verify age at all. Few vendors (35%) used age verification strategies that could be effective at verifying age. Date of birth (DOB), which could potentially be used in conjunction with name and address to verify customers’ age in PRDs, was used by 34% of vendors, however, failed orders that collected DOB for reasons related to payment processing, not age verification.

Only one vendor claimed to use stronger age verification (at delivery), but that order was not shipped due to payment processing problems. No vendors claimed to use an online age verification service or required buyers to submit driver licence information, which could be used to verify age with PRDs. No vendors used challenge questions; only one rejected the youth ID prompting use of the parent ID and potential challenge question presentation, but that order failed due to payment processing problems. No vendors complied with North Carolina and PACT Act age verification requirements.

Widespread fraud

The credit cards used in this study were exposed to widespread fraud totalling more than $7000 (detailed in an online supplementary table S1). Each card was brand new, used only for a handful of purchase attempts, and locked up when not in use. Their use at ICVs were followed by many hundreds of fraudulent charges, including some occurring shortly after cigarette purchase attempts, and others where criminals waited several months to make much larger fraudulent charges. ICV fraud also included instructing buyers to lie about what they were buying when sending payments (to a shell company or money transfer service), and 30 websites seemed unable to complete the transaction after buyers input credit card details; they may have been collecting credit card details explicitly for use in credit card fraud.

DISCUSSION

This study demonstrates that despite years of state and federal regulation restricting internet cigarette sales, with inadequate enforcement, many internet sellers are still violating those regulations, and teens can still obtain cigarettes online without being thwarted by age verification. Relying almost exclusively on age verification strategies that cannot possibly verify age effectively, none of the ICVs in the study complied with NC state law and federal PACT Act age verification requirements. Not surprisingly, after excluding the orders that failed for reasons unrelated to age verification (eg, payment processing problems), the teen buyers had a 100% buy rate from vendors, an even higher success rate than that (91.6%) experienced during the industry’s pre-regulation infancy.8 Furthermore, this study found extensive violations of the FSPTCA ban on flavoured and light cigarettes.

All of the ICVs that delivered cigarettes in this study were based outside of the USA. These vendors may think that they are not subject to the US regulations affecting internet cigarette sales to US customers (especially if the enforcing federal agencies do not notify them of their obligation to comply), and even if they are aware, they are unlikely to comply due to the lack of federal enforcement of applicable laws. At the same time, the ICVs’ desire to maximise profits disincentivises effective age verification implementation unless forced to do so.

Age verification strategies

Most commonly—and at the same rate found among internet alcohol vendors35—a third of ICVs verified age by requesting buyers’ DoB, in a few instances in conjunction with their social security number, which could have been used in combination with their address to verify age with PRDs, although there was no indication that any vendors attempted such verification. We cannot recommend the use of social security numbers for age verification, as it presents substantial risk of identity theft, especially on these often poorly designed websites with problematic payment processing methods, and in many cases, the fraudulent later use information provided by buyers.

None of the ICVs required buyers’ driver licence information prior to processing the order, the standard for age verification in face-to-face tobacco sales. The single vendor that claimed the buyer might need to send a copy of their licence accepted and processed the order without it, once the buyer provided a fake DoB, indicating that PRD verification was either not used or ineffective. Examining driver licences at the point of delivery is also the standard for age verification in retail sales and is the only opportunity in online transactions for face-to-face age verification. Unfortunately, no AVAD was done in any of the deliveries in this study—and prior studies by our team have shown that AVAD is infrequent in online sales,8 14 and has been ineffective at stopping deliveries to youth when it is used.35

AVAD has the potential to effectively prevent tobacco deliveries to minors, but only if it is consistently used by vendors and administered consistently and competently by those making the deliveries. In our recent youth online alcohol purchase study, UPS and FedEx delivery staff frequently failed to properly administer their companies’ AVAD policies, resulting in two-thirds of packages marked as requiring AVAD being left with a minor or at the door.35

Since USPS delivered all packages received in this study (in violation of the PACT Act), the federal government needs to carefully enforce the PACT Act to detect and prevent cigarettes from being illegally shipped through the mail to US customers (often from other countries).

Considering only one vendor even rejected a purchase attempt with a youth ID, prompting use of the parent’s ID, and not a single vendor in this study (or in our concurrent e-cigarette study)36 used challenge questions, whether challenge questions are an effective age verification strategy to block teens armed with their parent’s ID remains unanswered. Further research is needed to determine whether challenge questions can effectively prevent youth access to age restricted content.

While many orders in this study failed for reasons other than age verification, the continued lack of effective age verification used by ICVs (and lack of enforcement of PACT Act’s age verification requirements) is a serious problem. Despite federal laws requiring strict age verification at the points of order and delivery, the online cigarette youth buy rate is higher now than it was in our similar research conducted prior to any federal regulation,8 with no orders rejected due to properly conducted age verification. Simply passing laws requiring age verification clearly is not enough. Additional oversight and enforcement by the responsible federal agencies is needed.

It should also be noted that this study assessed sales rates as a function of how many vendors sold to minors, but did not assess changes in overall number of illegal online cigarette sales to minors; while the overall number of vendors selling to minors has fallen, those that sell to children may do so on a widespread basis.

State and federal policies

Lack of enforcement of federal policies15,16,18,19 to prohibit credit card payments, shipping of cigarettes and requiring age verification combined with highly adaptable vendors in an international marketplace has severely limited those policies’ effectiveness.37,38 No vendors complied with the federal shipping ban or age verification requirements, and despite having been in place for 6 months at the start of this study’s purchases, no vendors complied with North Carolina’s tobacco age verification law. Furthermore, despite the 2009 federal law banning sales of light and flavoured cigarettes, they are still widely available from online vendors.

To date, there has been no evidence of federal agencies enforcing the federal policies examined in this study. There were legal challenges delaying enforcement of the PACT Act, but those were dismissed in 2013.39 Attorneys for the city and state of New York have launched several lawsuits against ICVs and delivery companies in the name of PACT Act’s violations,40–46 but they have been focused on tax evasion and shipping bans, primarily with Native American vendors, ignoring shipments from overseas.

More must be done by federal agencies such as the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (BATFE), FDA, USPS and US Customs to ensure that all internet cigarette sellers to US consumers (including the vast majority that are now located internationally) know that they must comply with US policies and that they will face rigorous enforcement if they fail to do so. Since most ICVs are now located overseas, thorough screening by USPS and US Customs to stop illegally shipped cigarettes at the border (eg, with dogs trained to detect tobacco) is a crucial step for law enforcement.

Fraud: the new ICV story

The vast amount of fraud experienced in this study marks a major change in the story of what happens when people buy cigarettes online. Fraudulent charges totalled more than $7000, at least 3.7 times more than the $1877.08 that was spent on actual study purchases. Some vendors may have stolen credit card information or used unsecured connections to process credit cards, allowing a third party to steal the information. Furthermore, sites that failed to process orders may have been fake sites designed to look like legitimate ITVs in order to steal credit card information. Many fraudulent charges occurred 4–6 months after study completion, when the average credit card user would be unlikely to link the fraudulent charges to the cigarettes they ordered months earlier. This study indicates that in today’s internet market, consumers seeking to buy cigarettes online may be more likely to be victims of credit card fraud than to actually receive cigarettes.

CONCLUSIONS

In the absence of adequate enforcement of existing federal policies, most ICVs have moved overseas in an attempt to evade US laws by selling cigarettes (including banned light and flavoured cigarettes) and illegally shipping them to US customers, failing to verify age in accordance with state and federal regulations. While the US government’s strict laws have diminished the number of US-based vendors attempting to skirt these laws, it has resulted in a market filled with overseas vendors and has created a previously unseen issue with widespread credit card fraud. Federal agencies should work more effectively together, with international law enforcement authorities and private sector partners to devise better means of preventing these illegal cigarettes from reaching US consumers, particularly minors, and in preventing the theft of customers’ credit cards used on ICV websites, shutting down those sites where purchase attempts lead to fraud. Future studies should assess the success, extent and enforcement of these efforts.

Supplementary Material

What this paper adds.

-

►

Internet cigarette sales are a significant public health concern because they evade taxes by undermining state and federal excise tax collection; offer easy access to tobacco products for users who may be trying to quit, to underage users and experimenters; and because they are difficult to regulate.

-

►

To address those concerns, federal and state regulations have been passed to help better regulate internet cigarette vendors (ICVs), including the federal Family Smoking Prevention Tobacco Control Act (FSPTCA), the Prevent All Cigarette Trafficking (PACT) Act and a 2013 North Carolina age verification law. Among other provisions, they require strict online age verification for internet sales, prohibit the sale of cigarettes labelled as ‘light’ or with flavours (other than menthol) and prohibit internet vendors from using any major US shipping carrier (including the US Postal Service, UPS, FedEx and DHL).

-

►

This study is the first since the implementation of the above laws to examine the extent to which the ICV industry complies, and how it has changed in response to the recent legislation.

-

►

This study indicates that the majority of popular US-based ICVs have gone out of business, and the overwhelming majority of remaining ICVs selling to US customers are based outside the USA and not complying with US legislation, resulting in, among other things, an increase in the overall rate of sales by vendors to minors.

-

►

This study was the first to try to assess the use and success of challenge questions for age verification among ICVs, though none of the sites used challenge questions, leaving results inconclusive.

-

►

This study exposes additional hazards to purchasing cigarettes through the internet, including elevated risk of credit card fraud.

Acknowledgments

Funding This study was funded by grant 5R01CA169189-02 from the National Cancer Institute.

Footnotes

Additional material is published online only. To view please visit the journal online (http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2015-052844).

Contributors RSW had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. RSW was involved in study concept and design, obtained funding, and provided administrative, technical or material support. RSW also was involved in study supervision. All authors were involved in acquisition, analysis or interpretation of data, and critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. RSW, JD and KJP were involved in drafting of the manuscript. JD was involved in statistical analysis.

Competing interests None declared.

Ethics approval University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Institutional Review Board.

Provenance and peer review Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cohen JE, Sarabia V, Ashley MJ. Tobacco commerce on the internet: a threat to comprehensive tobacco control. Tob Control. 2001;10:364–367. doi: 10.1136/tc.10.4.364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Youth Smoking Prevention and State Revenue Enforcement Act. Hearing before the subcommittee on courts, the internet, and intellectual property of the committee on the judiciary House of Representatives. 108th. Washington DC, USA: Government Printing Office; 2003. p. 124. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mackey TK, Miner A, Cuomo RE. Exploring the e-cigarette e-commerce marketplace: identifying internet e-cigarette marketing characteristics and regulatory gaps. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2015;156:97–103. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.08.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chaloupka FJ. Macro-social influences: the effects of prices and tobacco-control policies on the demand for tobacco products. Nicotine Tob Res. 1999;1(Suppl 1):S105–S109. doi: 10.1080/14622299050011681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Reducing tobacco use: a report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA, USA: Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ribisl KM, Kim AE, Williams RS. Sales and marketing of cigarettes on the internet: emerging threats to tobacco control and promising policy solutions. In: Bonnie RJ, Stratton K, Wallace RB, editors. Ending the tobacco problem: a blueprint for the nation. Washington DC: The National Academies Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goolsbee A, Lovenheim M, Slemrod JB. Playing with fire: cigarettes, taxes and competition from the internet. Am Econ J. 2009;2:131–154. https://www.nber.org/papers/w15612. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ribisl KM, Williams RS, Kim AE. Internet sales of cigarettes to minors. JAMA. 2003;290:1356–1359. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.10.1356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jensen JA, Hickman NJ, III, Landrine H, et al. Availability of tobacco to youth via the Internet. JAMA. 2004;291:1837. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.15.1837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ribisl KM, Kim AE, Williams RS. Are the sales practices of internet cigarette vendors good enough to prevent sales to minors? Am J Public Health. 2002;92:940–941. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.6.940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Williams RS, Ribisl KM, Feighery EC. Internet cigarette vendors’ lack of compliance with a California state law designed to prevent tobacco sales to minors. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2006;160:988–989. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.160.9.988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [accessed 20 May 2014];2012 National Youth Tobacco Survey. 2014 http://www.cdc.gov/TOBACCO/data_statistics/surveys/NYTS/index.htm.

- 13.Unger JB, Rohrbach LA, Ribisl KM. Are adolescents attempting to buy cigarettes on the internet? Tob Control. 2001;10:360–363. doi: 10.1136/tc.10.4.360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Abrams SM, Hyland A, Cummings KM. Internet cigarette purchasing among ninth-grade students in Western New York. Prev Med. 2003;36:731–733. doi: 10.1016/s0091-7435(03)00056-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Attorney General of the State of New York Health Care Bureau. [accessed 7 Jul 2016];In the Matter of Federal Express Corporation, and FedEx Ground Package Systems, Inc.: Assurance of Compliance. 2006 Feb; http://www.ag.ny.gov/sites/default/files/press-releases/archived/FedEx%20-%20Executed%20AOC.pdf.

- 16.Attorney General of the State of New York Health Care Bureau. [accessed 22 Mar 2012];In the Matter of United Parcel Service: Assurance of Discontinuance. 2005 Oct; http://www.ag.ny.gov/sites/default/files/press-releases/archived/9tiupsaodfinal.oct.pdf.

- 17.Office of the New York State Attorney General. [accessed 23 Feb 2011];State AGs and ATF Announce Initiative with Credit Card Companies to Prevent Illegal Internet Cigarette Sales. 2005 http://www.ag.ny.gov/media_center/2005/mar/mar17b_05.html.

- 18.Attorney General of the State of New York Health Care Bureau. [accessed 7 Jul 2016];In the Matter of DHL Holdings USA, Inc., and DHL Express (USA), Inc.: Assurance of Discontinuance. 2005 Jul; http://www.ag.ny.gov/sites/default/files/press-releases/archived/dhlaogfinal.pdf.

- 19. [accessed 7 Jul 2016];Prevent All Cigarette Trafficking Act of 2009, 124 Stat. 1087 USC. 2009 https://www.congress.gov/111/plaws/publ154/PLAW-111publ154.pdf.

- 20. [accessed 7 Jul 2016];Prevent All Cigarette Trafficking Act of 2009, 124 Stat. 1087 USC, §2A(b)(4)(A) 2009 https://www.congress.gov/111/plaws/publ154/PLAW-111publ154.pdf.

- 21.United States Postal Service. [accessed 14 Mar 2016];DMM Revision: Treatment of Cigarettes and Smokeless Tobacco as Nonmailable Matter. 2010 http://about.usps.com/postal-bulletin/2010/pb22287/html/updt_002.htm.

- 22.Chriqui J, Ribisl KM, Wallace R, et al. State cigarette delivery sales laws: a review of provisions aimed at preventing youth access and tax evasion. Oral presentation at the 13th World Conference on Tobacco OR Health; Washington DC. 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 23.General Assembly of North Carolina. S.L. 2013-165 (S 530). An act to prohibit the distribution of tobacco-derived products and vapor products to minors. North Carolina: Raleigh; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 24. [accessed 7 Jul 2016];Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act 123 Stat. 1776 USC. 2009 https://www.congress.gov/111/plaws/publ31/PLAW-111publ31.pdf.

- 25. [accessed 7 Jul 2016];Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act 123 Stat. 1776 USC, §103(q)1(F)(iv) 2009 https://www.congress.gov/111/plaws/publ31/PLAW-111publ31.pdf.

- 26. [accessed 7 Jul 2016];Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act 123 Stat. 1776 USC, §906(d)4(A)(i) 2009 https://www.congress.gov/111/plaws/publ31/PLAW-111publ31.pdf.

- 27. [accessed 7 Jul 2016];Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act 123 Stat. 1776 USC, §911. 2009 https://www.congress.gov/111/plaws/publ31/PLAW-111publ31.pdf.

- 28. [accessed 7 Jul 2016];Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act 123 Stat. 1776 USC, §907(a)1(A) 2009 https://www.congress.gov/111/plaws/publ31/PLAW-111publ31.pdf.

- 29.Jo CL, Williams RS, Ribisl KM. Tobacco products sold by internet vendors following restrictions on flavors and light descriptors. Nicotine Tob Res. 2015;17:344–349. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntu167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Huang J, Kornfield R, Szczypka G, et al. A cross-sectional examination of marketing of electronic cigarettes on Twitter. Tob Control. 2014;23(Suppl 3):iii26–iii30. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2014-051551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. [accessed 10/9/2014];Alexa Traffic Ranking. 2014 http://www.alexa.com.

- 32.Williams RS, Ribisl KM. Effectiveness of Tobacco Company Efforts to Verify Age and Restrict Minors’ Access to Cigarette Marketing Websites: A Report to the National Association of Attorneys General. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Williams RS, Ribisl KM. Effectiveness of tobacco company efforts to verify age and restrict minors’ access to cigarette marketing websites: a report to the National Association of Attorneys General. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Institute of Medicine. Ending the tobacco problem: a blueprint for the nation. Washington DC: The National Academies Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Williams RS, Ribisl KM. Internet alcohol sales to minors. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2012;166:808–813. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2012.265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Williams RS, Derrick J, Ribisl KM. Electronic cigarette sales to minors via the internet. JAMA Pediatr. 2015;169:e1563. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Williams RS, Ribisl KM. Vendor compliance with bans on credit card payments and commercial shipping for online cigarette sales; American Public Health Association Annual Meeting; 2 November 2011; Washington DC. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Williams RS, Ribisl KM. Internet cigarette vendor compliance with credit card payment and shipping bans. Nicotine & Tobacco Research; 2013. Oct 24, [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.U.S. Attorney’s Office. [accessed 29 Mar 2016];PACT Act Now Fully Enforceable. 2013 http://www.justice.gov/usao-wdny/pr/pact-act-now-fully-enforceable.

- 40.Gregorian D. [accessed 29 Mar 2016];FedEx hit with $235m lawsuit from Attorney General Eric Schneiderman for shipping untaxed cigarettes. 2014 http://www.nydailynews.com/new-york/fedex-hit-235m-lawsuit-shipping-untaxed-cigarettes-article-1.1739975.

- 41.Caruso DB. [accessed 29 Mar 2016];Law fails to stop cigarette flow from Native American tribes. 2013 http://www.democratandchronicle.com/story/news/2013/12/02/law-fails-to-stop-cigarette-flow-from-native-american-tribes/3904503/

- 42.The Associated Press. [accessed 29 Mar 2016];Government lawsuits seen as slowly snuffing out NY Indian sales of untaxed cigarettes. 2013 http://www.syracuse.com/news/index.ssf/2013/12/government_lawsuits_seen_as_snuffing_out_ny_indian_sales_of_untaxed_cigarettes.html.

- 43.Straight B. [accessed 29 Mar 2016];New York authorities allege package delivery company has been shipping illegal cigarettes. Trucking Straight Talk. 2013 http://fleetowner.com/blog/new-york-authorities-allege-package-delivery-company-has-been-shipping-illegal-cigarettes.

- 44.The Oneida Daily Dispatch. [accessed 29 Mar 2016];N.Y. Attorney General Eric Schneiderman sues major contraband cigarette dealers for evading state taxes. 2013 http://www.oneidadispatch.com/article/OD/20130304/NEWS/303049992.

- 45.Corporate Crime Reporter. [accessed 29 Mar 2016];New York Attorney General Sues FedEx. 2014 http://www.corporatecrimereporter.com/news/200/new-york-attorney-general-sues-fedex/

- 46. [accessed 7 Jul 2016];State of New York et al. v. United Parcel Service, 16 September 2015 (U.S. District Court Southern District of New York 2015) http://law.justia.com/cases/federal/district-courts/new-york/nysdce/1:2015cv01136/438585/49/

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.