Abstract

To prevent inguinal hernia after retropubic radical prostatectomy, many urologists have utilized a prevention technique of inguinal hernia at the same time as retropubic radical prostatectomy. Here, we report the clinical benefit of the prevention technique of inguinal hernia as well as risk factors for the incidence of inguinal hernia. We investigated the medical records of 223 men who underwent retropubic radical prostatectomy for clinically localized prostate cancer between January 2007 and March 2013 at our medical center. We assessed the association between the postoperative inguinal hernia and variables such as age, body mass index, and previous abdominal surgery. Inguinal hernia-free survival was analyzed to verify risk factors of postoperative inguinal hernia. Of 223 patients, 67 (30 %) received prevention of inguinal hernia and 156 (70 %) did not. The median follow-up period after retropubic radical prostatectomy was 36 months (range, 3–58 months). Thirty one (14 %) patients developed unilateral or bilateral inguinal hernia after retropubic radical prostatectomy. The rate of postoperative inguinal hernia in prevented and non-prevented group was 3 % (2 of 67) and 19 % (29 of 156), respectively (P < 0.01, Mann-Whitney U test). Moreover, postoperative inguinal hernia-free survival in the prevention group was significantly longer than that in the non-prevented group (P < 0.01, log-rank test). In the prevention group, 1-, 2-, and 3-year inguinal hernia-free survival rates were 100 %, 96 %, and 96 %, respectively. Other clinical factors including age, body mass index, previous abdominal surgery, and previous inguinal hernia were not associated with the incidence of inguinal hernia in our cohort. The prevention technique was simple and safe to perform, and it could increase inguinal hernia-free survival rates after retropubic radical prostatectomy.

Keywords: Inguinal hernia, Prostate cancer, Retropubic radical prostatectomy, Prevention procedure

Introduction

In the modern prostate-specific antigen (PSA) era, prostate cancer (PCa) has become one of the most commonly diagnosed malignancies among Japanese men. Retropubic radical prostatectomy (RRP) is a standard treatment option for clinically localized and a part of locally advanced PCa. Since the first report by Regan et al. in 1996 [1], the high incidence of postoperative inguinal hernia (IH) has been recognized as a common complication of RRP. The incidence of IH after RRP has been reported to range from 12 % to 38.7 % [1–7]. Furthermore, reportedly more than 90 % of IH after RRP was indirect hernia [4, 6].

Postoperative IH can cause discomfort or dull pain in the groin and requires repair surgery for it such as placement of mesh patches. Once IH develops, patient’s quality of life is remarkably reduced. Strangulated hernia may occur and require consequently bowel resection in a severe case. The etiology of postoperative IH after RRP remains unclear for now. One of the most likely hypotheses is the potential opening of processus vaginalis by the damage to the abdominal wall during surgery [4].

In this retrospective and single institution study, we investigated the risk factors of postoperative IH after RRP and the clinical benefit of the prevention technique for it.

Methods

Patient Selection and Data Collection

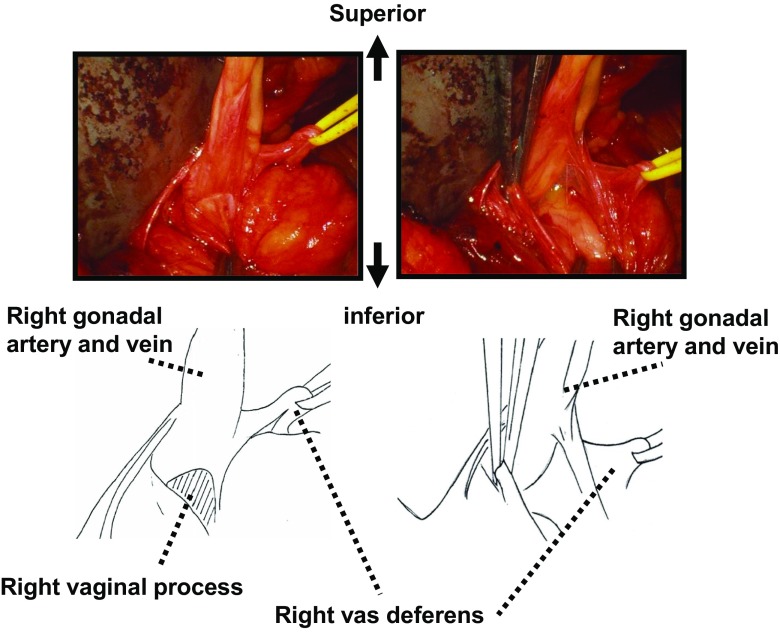

The clinical information was collected by retrospective chart review after approval by the ethical committees of the hospitals involved. We reviewed the clinical and pathologic data of 223 consecutive patients who underwent RRP at our medical center between January 2007 and March 2013. RRP was performed through a lower midline incision from the subumbilicus to the suprapubic symphysis. Some proportion of patients was carried out simultaneously with pelvic lymph nodes dissection or a nerve sparing technique. Of the 223, 67 patients underwent procedures for concurrent IH prevention at the time of RRP. The procedure for hernia prevention we performed was blunt dissection of the peritoneum at the internal inguinal ring to isolate the spermatic cord, as Sakai et al. previously reported (Fig. 1) [8]. The complete dissection of the processus vaginalis from surrounding tissues such as abdominal wall, vas deferens and testicular blood vessels results in the adhesion at around the processus vaginalis after RRP. The adhesion prevents the onset of postoperative indirect IH.

Fig. 1.

The technique of inguinal hernia prevention. a, the spermatic cord is dissected from the inner surface of the abdominal wall and the peritoneum at the internal inguinal ring. b, the spermatic cord is isolated from surrounding peritoneum. c, the vas deferens is dissected from the spermatic cord. d, the processus vaginalis just distal to the peritoneum is dissected free of the other spermatic cord elements

Of the 223, 31 patients developed postoperative IH and 192 patients did not. All patients were followed up with PSA tests every 3 months for 1–2 years, semiannually for 3–5 years, and annually thereafter. Imaging studies including lung and abdominal computed tomography scans, pelvic magnetic resonance imaging, and radioisotope bone scan were performed if the biochemical or clinical disease progression was suspected. The median follow-up period in this cohort was 44 months. We first investigated the risk factors of the IH after RRP. The risk factor previously reported such as age, body mass index (BMI), pelvic lymph nodes dissections (PLND), past history of IH repair, past history of abdominal surgery, and postoperative anastomotic stricture were considered. Second, we investigated the incidence of the IH in patients with or without the prevention technique.

Statistical Analysis

The statistically significant differences were analyzed using the Mann-Whitney U test, Chi-square test, and Fisher’s exact test. The IH-free survival curves were obtained using the Kaplan-Meier method and compared by the log-rank test for each prognostic variable. PRISM software 5.00 (San Diego, CA, USA) were utilized for statistical analyses and data plotting, respectively. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Of 223 patients, 31 (14 %) men developed a postoperative IH during follow-up. The median time to IH onset was 36 months. The laterality of the IH was the right in 16, left in 7, and bilateral in 8 patients, respectively. The type of IH was direct in 2, indirect in 25, and unknown in 4 patients, respectively. The rate of postoperative IH in prevented and non-prevented group was 3 % (2 of 67) and 19 % (29 of 156), respectively (P < 0.01, Mann-Whitney U test). The comparison in clinical characteristics between patients with and without the postoperative IH was summarized in Table 1. The incidence of IH was significantly lower in the patients who had undergone the IH prevention technique (2 out of 31, 6 %) as compared with those who had not (65 out of 192, 34 %). Higher BMI was not associated with higher incidence of postoperative IH in our cohort (P = 0.12). The median follow-up duration of the patients with postoperative IH group and those without IH was 46 months (range 12 to 81) and 44 months (range 12 to 84), respectively. Of 31 patients who developed postoperative IH, 6 patients (19 %) had a history of previous abdominal surgery and 2 patients (6 %) had a history of previous IH repair. Previous history of surgery and postoperative anastomotic stricture were not associated with incidence of postoperative IH.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| Variables | Postoperative inguinal hernia | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | ||

| Patients (%) | 31 (14 %) | 192 (86 %) | |

| Age (median [IQR]) | 69 (57–78) | 69 (51–78) | 0.38 † |

| Follow-up months (median [IQR]) | 46 (12–81) | 44 (12–84) | 0.03 † |

| PSA (median [IQR]) | 7.9 (4.3–146) | 7.8 (4.0–121) | 0.77 † |

| BMI (median [IQR]) | 23 (18–28) | 23 (17–33) | 0.12 † |

| Prostate volume (median [IQR]) | 30 (11–123) | 30 (6–76) | 0.27 † |

| Previous abdominal surgery (%) | 6 (19 %) | 25 (13 %) | 0.40 ‡ |

| Previous inguinal hernia repair (%) | 2 (6 %) | 10 (5 %) | 0.68 ‡ |

| Operative time (median [IQR]) | 266 (184–352) | 267 (150–465) | 0.69 † |

| LND (%) | 7 (22 %) | 55 (28 %) | 0.67 ‡ |

| Inguinal hernia prevention (%) | 2 (6 %) | 65 (34 %) | <0.01 ‡ |

| Postoperative anastomotic stricture (%) | 2 (6 %) | 8 (4 %) | 0.63 ‡ |

† Mann-Whiteny U test

‡ Chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test

IQR interquartile range,PSA Prostate Specisfic Antigen, BMI Body Mass Index, LND Lymph Node Dissection

Table 2 depicts the comparison in clinical characteristics between the patients who have undergone the prevention technique and those who do not. Of 223 patients, 67 (30 %) have undergone the prevention technique of IH. The median follow-up duration of the IH prevention group and no prevention group was 35 months (range 12 to 65) and 45 months (range 12 to 84), respectively (P < 0.01). With regard to surgery-related factors, such as operative time or perioperative complications, there was no significant relationship between those factors and incidence of IH.

Table 2.

Patient characteristics according to adding inguinal hernia prevention

| Variables | Inguinal hernia prevention | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | ||

| Patients (%) | 67 (30 %) | 156 (70 %) | |

| Age (median [IQR]) | 69 (52–78) | 69 (51–78) | 0.27 † |

| Follow-up months (median [IQR]) | 35 (12–65) | 45 (12–84) | <0.01 † |

| PSA (median [IQR]) | 7.8 (4.0–56) | 7.9 (4.0–146) | <0.01 † |

| BMI (median [IQR]) | 24 (18–29) | 23 (17–33) | 0.16 † |

| Prostate volume (median [IQR]) | 33 (7–74) | 31 (6–123) | 0.03 † |

| Operative time (median [IQR]) | 269 (174–382) | 267 (150–465) | 0.64 † |

| LND (%) | 20 (30 %) | 42 (27 %) | 0.74 ‡ |

| Other complications | 2 (6 %) | 6 (3 %) | 1.00 ‡ |

† Mann-Whiteny U test

‡ Chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test

IQR interquartile range, PSA Prostate Specisfic Antigen, BMI Body Mass Index, LND Lymph Node Dissection

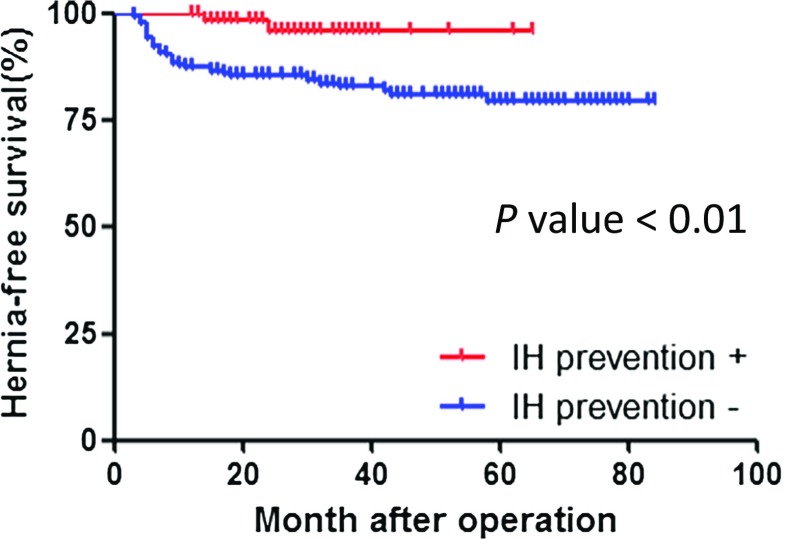

Next, we analyzed IH-free survival curves to identify the risk factors for the incidence of postoperative IH (Table 3). Carrying out the IH prevention technique was the only one factor associated with the lower risk of incidence of postoperative IH (hazard ratio 0.34, P < 0.007). The hernia-free survival rates in patients who underwent the IH prevention were 100 %, 96 %, and 96 %, for 1-, 2-, and 3-year, respectively (Fig. 2). In contrast, the hernia-free survival rates in patients who did not undergo the IH prevention were 87 %, 85 %, and 82 %, for 1-, 2-, and 3-year, respectively (Fig. 2). Patients who did not undergo IH prevention were significantly in higher development of the postoperative IH than those who underwent it. Age, BMI, previous history of abdominal surgery, lymph node dissection and postoperative anastomotic stricture were not predictors for the incidence of postoperative IH.

Table 3.

Univariated analysis for prognostic factors

| Variables | Hernia-free survival | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95 % CI | P value | |

| Age (years) | |||

| 69 ≤ | 1 | ||

| 69 > | 0.67 | 0.33–1.37 | 0.28 † |

| BMI | |||

| 23 ≤ | 1 | ||

| 23 > | 1.40 | 0.67–2.92 | 0.35 † |

| Previous abdominal surgery | |||

| Yes | 1 | ||

| No | 0.76 | 0.29–2.02 | 0.62 ‡ |

| Previous inguinal hernia repair | |||

| Yes | 1 | ||

| No | 0.82 | 0.17–3.90 | 0.61 ‡ |

| LND | |||

| Yes | 1 | ||

| No | 1.25 | 0.57–2.78 | 0.69 ‡ |

| Postoperative anastomotic stricture | |||

| Yes | 1 | ||

| No | 0.46 | 0.07–3.00 | 0.36 ‡ |

| Inguinal hernia prevention | |||

| Yes | 1 | ||

| No | 2.93 | 1.29–6.63 | 0.007 ‡ |

† Mann-Whiteny U test

‡ Chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test

HR hazard ratio, CI confience interval, BMI Body Mass Index, LND Lymph Node Dissection

Fig. 2.

Comparison of inguinal hernia-free survival curves between prevention group (67 patients) and non-prevention group (156 patients). P value is calculated with log-rank test

Discussion

We observed a 14 % incidence of postoperative IH and the median time of its development from RRP was 36 months. This result was almost the same as the previous reports. Currently several clinical risk factors of postoperative IH are reported, such as increasing age, low value of BMI, PLND, previous history of IH repair, previous history of abdominal surgery, postoperative anastomotic stricture, and postoperative wound-related problems [4]. In our present study, none of these factors we analyzed showed statistical significance. This reason is not known. Our data showed that adding the prevention technique the incident rate of postoperative IH reduced to as low as 3 %. Although it may be difficult to predict postoperative IH, the preventing procedure for IH is easy to perform and does not take time for all of urologists. Once a strangulated hernia is occurred, the emergency surgery is inevitable and the reported mortality rate is as high as 14 % [9]. Then we urologists should make an effort to prevent incidence of postoperative IH.

Fujii et al. reported the processus vaginalis transection method [7]. They showed the patients who underwent IH prevention were lower incidence of the postoperative IH than those who did not and the hernia-free survival rates for 1-, 2-, and 3-year were 87 %, 81 %, and 77 %, respectively. Our result also showed the procedure for the IH prevention at our medical center was effective in keeping free from development of postoperative IH. Although Regan et al. reported the relation between the RRP and the postoperative IH in 1996, the mechanism of its development is still poorly understood [1]. The most likely hypothesis is that potential opening of processus vaginalis which has existed preoperatively changes into more complete one through the mechanical damage to the abdominal wall and the inguinal ring during RRP resulting in the failure of shutter mechanism. The shutter mechanism is produced by the transversus aponeurotic arch when the transversus abdominal muscle and internal oblique muscles are stretched. Thus it is important to preserve the transversalis fascia intact. But this is not sufficient to explain the incidence of postoperative IH because patients who underwent laparoscopic radical prostatectomy or robot-assisted laparoscopic radical prostatectomy also developed 3 to 14 % incidence of postoperative IH [4, 10, 11].

Ichioka et al. reported 3 of 56 patients who underwent total cystectomy developed postoperative IH and the IH free rate of total cystectomy group was significantly higher than RRP group [3]. We focused on this point and hypothesized that at the time of bladder urethra anastomosis of RRP, peritoneum attached to the bladder dome was pulled caudally and the angle of processus vaginalis became more obtuse resulting in widening its root. We believe this anatomical change is one of the fundamental factors of the development of postoperative IH. In order to prove this hypothesis, it remains to be done that we demonstrate the expected morphological change of processus vaginalis which develops by RRP.

In conclusion, IH as one of common complications after RRP can be prevented by adding a simple procedure we demonstrated here. Because IH sometimes falls into emergency, adding the procedure of IH prevention should be standard at RRP.

IH inguinal hernia; RRP retoropubic radical prostatectomy; PSA prostate-specific antigen; PCa prostate cancer; CT computed tomography; MRI magnetic resonance imaging; BMI body mass index; PLND pelvic lymph node dissections.

Acknowledgments

This work was not funded by any companies.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Regan TC, Mordkin RM, Constantinople NL, et al. Incidence of inguinal hernias following radical retropubic prostatectomy. Urology. 1996;47:536–537. doi: 10.1016/S0090-4295(99)80491-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Twu CM, Ou YC, Yang CR, et al. Predicting risk factors for inguinal hernia after radical retropubic prostatectomy. Urology. 2005;66:814–818. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2005.04.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ichioka K, Yoshimura K, Utsunomiya N, et al. High incidence of inguinal hernia after radical retropubic prostatectomy. Urology. 2004;63:278–281. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2003.09.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abe T, Shinohara N, Harabayashi T, et al. Postoperative inguinal hernia after radical prostatectomy for prostate cancer. Urology. 2007;69:326–329. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2006.09.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Koie T, Yoneyama T, Kamimura N, et al. Frequency of postoperative inguinal hernia after endoscope-assisted mini-laparotomy and conventional retropubic radical prostatectomies. Int J Urol. 2008;15:226–229. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2042.2007.01983.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lodding P, Bergdahl C, Nyberg M, et al. Inguinal hernia after radical retropubic prostatectomy for prostate cancer: a study of incidence and risk factors in comparison to no operation and lymphadenectomy. J Urol. 2001;166:964–967. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)65874-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fujii Y, Yamamoto S, Yonese J, et al. A novel technique to prevent postradical retropubic prostatectomy inguinal hernia: the processus vaginalis transection method. Urology. 2010;75:713–717. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2009.05.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sakai Y, Okuno T, Kijima T, et al. Simple prophylactic procedure of inguinal hernia after radical retropubic prostatectomy: isolation of the spermatic cord. Int J Urol. 2009;16:848–851. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2042.2009.02370.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jasper WS., Sr Combined open prostatectomy and herniorrhaphy. J Urol. 1974;111:370–373. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)59968-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lin BM, Hyndman ME, Steele KE, et al. Incidence and risk factors for inguinal and incisional hernia after laparoscopic radical prostatectomy. Urology. 2011;77:957–962. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2010.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stranne J, Johansson E, Nilsson A, et al. Inguinal hernia after radical prostatectomy for prostate cancer: results from a randomized setting and a nonrandomized setting. Eur Urol. 2010;58:719–726. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2010.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]