Abstract

Background:

Malaria is the most important transfusion-transmitted infection (TTI) in worldwide after viral hepatitis and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection. The main objective of the present study was to review and evaluate the transmission of malaria via blood transfusion in Iran.

Methods:

A literature search was done without time limitation in the electronic databases as follows: PubMed, Scopus, Google Scholar, Web of Science, Science Direct, scientific information database (SID), Magiran, IranMedex and Irandoc. The searches were limited to the published papers to English and Persian languages.

Results:

Six papers were eligible. From 1963 to 1983, 344 cases of Transfusion-transmitted malaria (TTM) had been reported from different provinces of Iran. The most prevalent species of involved Plasmodium in investigated cases of TTM was Plasmodium malariae (79.24%). The screening results of 1,135 blood donors for malaria were negative by microscopic examination of peripheral blood smears and rapid diagnostic test (RDT) methods.

Conclusion:

Lack of TTM report from Iran in the last three decades indicates that the screening of blood donors through interviewing (donor selection) may be effective in the prevention of the occurrence of transfusion-transmitted malaria.

Keywords: Transfusion-transmitted malaria, Blood transfusion, Donors, Screening, Iran

Introduction

Malaria is one of the most important protozoan parasitic infections of humans in the world mainly transmitted by the bite of infected female Anopheles mosquitoes. Nearly half of the world’s population (3.3 billion people) are at risk of being infected with malaria and 198 million cases of malaria were reported from 97 countries with 584,000 deaths in 2013 (1).

The first case of transfusion-transmitted malaria (TTM) was reported in 1911 (2). The transmission of malaria via blood transfusion is rare, but can lead to serious consequences in non-immune recipients to malaria (3–5). In malaria non-endemic and endemic areas, the frequency of TTM has been estimated to be one case per four million and more than 50 cases per million units of transfused blood, respectively (3, 6–9). Totally, more than 3,000 cases of TTM were reported globally (3, 6, 10).

The most prevalent species associated with TTM are Plasmodium falciparum, P. malariae and P. vivax. Considering the malaria infected blood donors are semi-immune, the parasites load is low and no clinical symptoms is observed, as well as Plasmodium species can survive for years in those donors. As the result of the asymptomatic persistence of parasites, the transmission of P. malariae has been documented as long as 44 years, P. vivax for five years and a period of eight years for P. falciparum after the last exposure (3, 11). The malaria parasites can live for about 20 days at temperature between 2 °C and 6 °C, the used condition for banking red blood cells (RBCs) or erythrocytes (10, 12–14). Although whole blood and RBCs concentrates are the most common source of TTM, cases from blood components containing infected RBCs such as platelets, leukocytes and fresh frozen plasma (FFP), as well as frozen RBCs have been reported (15–20).

The screening of blood donors for malaria is performed in malaria non-endemic and endemic countries by various strategies including donor selection (donor history) and laboratory tests (parasitological, immunodiagnostic and molecular methods) (4). Donor selection or screening of blood donors through interviewing is the first and in many countries the only step in the prevention of transfusion-transmitted infections (TTIs) such as malaria (21). The laboratory tests available for malaria screening include the light microscopic examination of peripheral blood smears, quantitative buffy coat (QBC), and antigen and antibody detection by immunodiagnostic methods and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) types. All of these tests have limitations in sensitivity, specificity, cost, speed, reliability and complexity (14, 22). Although the world health organization (WHO) recommends that all donated blood should be screened for malaria (23, 24), there is no reliable approved laboratory test yet available for malaria screening in blood donors (14). However, the optimum strategy for minimizing the risk of TTM in non-endemic and endemic areas is a combination of proper donor selection together with donation blood screening by using a laboratory test, which should be simple, sensitive, fast and cost effectiveness (4, 11, 25 ).

In Iran, located in the Eastern Mediterranean Region, malaria is one of the most important public health problems that its transmission mainly occurs in the southeast of country. This part of Iran consists of three provinces as malaria endemic areas with low endemicity, including Sistan and Baluchestan, Hormozgan and Kerman (Fig. 1) (1, 26). In 2013, based on the latest report of the WHO, 1,373 malaria cases were reported from Iran, of which 82% were microscopically diagnosed as P. vivax and the remaining 18% as P. falciparum (1).

Fig. 1:

Geographical situation of malaria endemic areas of Iran namely Sistan and Baluchestan, Hormozgan and Kerman provinces in the southeast of this country, bordering Afghanistan, Pakistan, the Oman Sea and the Persian Gulf (27)

The objective of this study was to review and evaluate the transmission of malaria via blood transfusion in Iran and to remind the necessity of blood donors screening in malaria endemic areas of Iran by appropriate laboratory test.

Materials and Methods

Search strategy and databases

The present research was performed without time limitation using such terms as follows: “Malaria”, “Blood transfusion”, “Transfusion-transmitted malaria”, “Induced malaria”, “Blood donors”, “Screening” and “Iran” alone or in combination, both in English and Persian (Farsi) languages. The used electronic databases for searching included as follows: PubMed, Scopus, Google Scholar, Web of Science, Science Direct, scientific information database (SID), Magiran, IranMedex and Iran-doc. The searches were limited to the published papers to English and Persian languages.

Data extraction and collection

We comprehensively searched all abovementioned databases. The collected bibliographic references were carefully screened to eliminate the duplicates and non-related studies. Overall, six papers were selected. As the number of carried out studies was low in Iran, all six found papers were reviewed. The following data were extracted from the papers: first author, calendar period, year of publication, geographical region (province/city) of study, sample size, laboratory screening method and malaria prevalence. Finally, the extracted data were recorded in a checklist that was prepared for this purpose.

Results

After search in all nine databases, six papers were eligible. Two papers were in English.

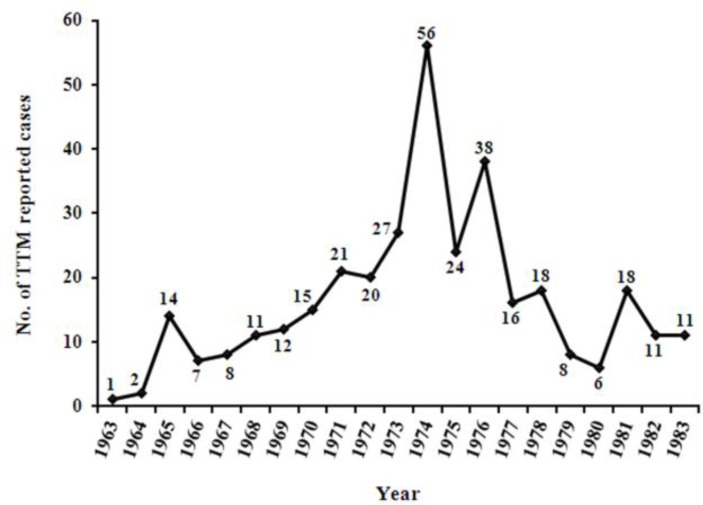

The incidence of TTM had been reported from different provinces of Iran in two papers. In the annual reports of the malaria eradication organization (MEO) and the Employees Health Department of the National Iranian Oil Company 111 cases of TTM had been recorded from 10 provinces during the 10 years from 1963 to 1972 (Fig. 2). The species of plasmodia involved in 56 investigated cases of TTM from 1970 to 1972 were P. malariae (73%, 41/56) and P. vivax (27%, 15/56) by the light microscopic examination of peripheral blood smears.

Fig. 2:

Trend of transfusion-transmitted malaria (TTM) reported cases from different provinces of Iran during the 21 years from 1963 to 1983 (28, 29)

From 1973 to 1983, 233 cases of TTM had been recorded in the general office of malaria eradication (GOME) of the Ministry of Health and the School of Public Health and Institute of Public Health Research of Tehran University from 19 provinces during the 11 years (Fig. 2). In 50 diagnosed cases using the light microscopic examination of Giemsa-stained thick and thin blood smears, the plasmodia species were P. malariae (86%, 43/50) and P. vivax (14%, 7/50).

So far, the P. falciparum has not been reported as the cause of TTM from Iran and the P. malariae is the most prevalent reported species (79.24%, 84/106).

Five studies had been done on 1,135 blood donors from malaria non-endemic and endemic areas of Iran including Gilan (n = 177), Tehran (n = 404), Sistan and Baluchestan (n = 504) and Hormozgan (n = 50) provinces. All studies were cross-sectional and had been conducted in 1973–75, 2002, 2009 and 2010, respectively. In these studies, blood donors had been screened for malaria using light microscopic examination of Giemsa-stained thick and thin blood smears, antigen detection by rapid diagnostic test (RDT) or Dipstick, antibody detection with indirect immunofluorescence assay (IFA) or enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and PCR methods.

The malaria screening results of blood donors were negative by microscopic examination of peripheral blood smears and RDT methods, as well as PCR but 1% (2/50) belonging to Bandar Abbas City that were positive with real-time PCR. In four studies that the blood donors screening for malaria had been performed using IFA and ELISA methods, the tests results were positive in 13.98% (91/651) and 4.69% (18/384), respectively (Table 1).

Table 1:

Characteristics and results of included studies on blood donors in the present review

| First author (Reference) | Calendar period | Year of publication | Province | City | No. of donors | Laboratory screening method | Malaria Prevalence (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Edrissian (29, 30) | 1973–75 | 1985, 1975 | Gilan and Tehran | Rasht and Tehran | 531a | MEb, IFA | 47 (8.85) donors by IFA |

| Moghtadaei et al. (31) | 2002 | 2005 | Sistan and Baluchestan | Iranshahr | 120 | ME, IFA, PCR | 44 (36.67) donors by IFA |

| Sanei Moghaddam et al. (32) | 2009 | 2011 | Sistan and Baluchestan | Zahedan | 384 | ME, RDT, ELISA, PCR | 18 (4.69) donors by ELISA |

| Hassanpour et al. (33) | 2010 | 2011 | Hormozgan and Tehran | Bandar Abbas and Tehran | 100 | ME, RDT, Real-time PCR | 2 (1) donors by real-time PCRc |

ME: light microscopic examination of Giemsa-stained thick and thin blood smears, IFA: indirect immunofluorescence assay, PCR: polymerase chain reaction, RDT: rapid diagnostic test, ELISA: enzyme linked immunosorbent assay

These were paid donors.

This test was performed only in IFA positive donors.

Two (1%) cases of 50 blood donors belonging to Bandar Abbas city

Discussion

The need for blood and blood components is universal and are mainly used in the management of patients who suffer from cancer, blood disorders, trauma and emergencies. Although blood transfusion is a lifesaving procedure, it may also cause adverse reactions and the transmission of blood-borne pathogens (34). Many infectious diseases can be transmitted via blood and blood components such as human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), viral hepatitis, syphilis, brucellosis, visceral leishmaniasis (VL), malaria, toxoplasmosis, measles, American trypanosomiasis (Chagas disease) and babesiosis (10, 35).

Malaria is one of the first TTIs recorded worldwide (4). With regard to the prevalence of malaria and the extensive use of blood and blood components in the world, as well as the possibility of malaria transmission through blood transfusion, the importance of TTM well is evident especially in malarious regions.

Before starting the malaria eradication program (MEP) in Iran, malaria was prevalent in most areas of the country with low to high endemicity. With the performance of the MEP and the malaria control program (MCP) since 1958 and 1980, respectively, malaria was limited to the southeast provinces namely Sistan and Baluchestan, Hormozgan and Kerman (Fig. 1) (36, 37).

The Iranian blood transfusion organization (IBTO) was established in 1974 with the purpose of supplying a sufficient and safe blood and blood components to recipients (38–40). Until that time, the blood donors mostly were paid and limited in number (28). Since the establishment and start working of the IBTO, the paid donation was forbidden and relied on family/replacement and voluntary non-remunerated blood donation (VNRBD). Since 2007, the IBTO reached to a 100% VNRBD (39, 41). In Iran, all of the donated blood is screened for HIV, hepatitis B virus (HBV), hepatitis C virus (HCV), syphilis and in some regions for human T-lymphotropic virus type 1 (HTLV-1) and type 2 (HTLV-2). The malaria screening is carried out in the IBTO through interviewing with donors by a trained physician who asks questions about the history of malaria disease and traveling and living in malaria endemic areas (39, 40, 42). In Iran, based on the IBTO standard operating procedures (SOPs), volunteers who have the past history of malaria are permanently deferred from blood donation. A history of residence and travel to malarious areas leads to a deferral for three years and one year from donating, respectively.

Given the high prevalence of malaria almost in all regions of Iran before starting the MEP (36, 37) and the lack of diagnosis or report, a large number of TTM cases (30), 344 cases of reported TTM from 1963 to 1983 do not reflect the actual number of TTM (Fig. 2). Although with the establishment and start working of the IBTO in most provinces, the paid donation was forbidden and used from blood of eligible donors instead of paid donors. During the years 1963 to 1972, the incidence of TTM had increased in Iran (Fig. 2) which could be because of more attention and more accurate survey of TTM and the report of occurred cases. However, the incidence of TTM cases had decreased from 1973 to 1983 that could be due to the establishment and start working of the IBTO and the exclusion of paid donors from blood donation, as well as the screening of blood donors through interviewing. Due to the consumption increasing of blood and blood components and more awareness and attention of physicians and health careers workers (HCW) to the diagnosis and report of TTM, the number of TTM reported cases during 1973 to 1983 was more than two times the years 1963 to 1972 (Fig. 2).

From 1983 to the end of June 2015, no case of TTM has been reported from Iran that may be for the following reasons: 1) Effectiveness of blood donors screening through interviewing (donor selection) in the IBTO; 2) Inattention to the incidence of malaria in non-endemic areas; 3) Lack of timely diagnosis and treatment of TTM cases and consequently the death or self-limited of infected individuals; 4) Severe decrease of malaria cases in the general population during the recent two decades (37, 43) and 5) Lack of reporting of the occurrence of TTM to authorities such as the ministry of health and medical education (MOHME).

In this review, the results of malaria screening in blood donors were negative using microscopic examination of peripheral blood smears and RDT methods, as well as with PCR but two cases. These results indicate that the donor selection or screening of blood donors through interviewing may be effective for minimizing the risk of TTM in non-endemic and endemic areas. However, the limitations of laboratory screening tests of malaria particularly their sensitivity should be considered in interpreting of negative results (29).

Conclusion

Lack of TTM report from Iran in the last three decades indicates that the screening of blood donors through interviewing (donor selection) may be effective in the prevention of the occurrence of transfusion-transmitted malaria. Since malaria is endemic in parts of Iran and the screening of blood donors is done only through interviewing, as well as due to the extensive use of blood and blood components, the immigration increasing from malaria endemic to non-endemic areas and traveling to malarious regions, the transmission of malaria via blood transfusion is possible.

Acknowledgements

We thank the cooperation of Prof. GhH. Edrissian from the Department of Medical Parasitology and Mycology, School of Public Health, Tehran University of Medical Sciences (TUMS) for providing the original version of his papers. The authors declare that they have no conflict of interests.

References

- 1. World Health Organization World Malaria Report 2014. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2014. Available from: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/144852/2/9789241564830_eng.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 2. Woolsey G. Transfusion for pernicious anaemia: Two cases. Ann Surg. 1911; 5 3: 132– 5. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mungai M, Tegtmeier G, Chamberland M, Parise M. Transfusion transmitted malaria in the United States from 1963 through 1999. N Engl J Med. 2001; 344 (26): 1973– 8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kitchen AD, Chiodini PL. Malaria and blood transfusion. Vox Sang. 2006; 90 (2): 77– 84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Owusu-Ofori AK, Betson M, Parry CM, Stothard R, Bates I. Transfusion-transmitted malaria in Ghana. Clin Infect Dis. 2013; 56 (12): 1735– 41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bruce-Chwatt LJ. Transfusion malaria revisited. Trop Dis Bull. 1982; 79 (10): 827– 40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bruce-Chwatt LJ. Transfusion associated parasitic infections. Prog Clin Biol Res. 1985; 18 2: 101– 25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Nahlen BL, Lobel HO, Cannon SE, Campbell CC. Reassessment of blood donor selection criteria for United States travellers to malarious areas. Transfusion. 1991; 31 (9): 798– 804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Reesink HW. European strategies against the parasite transfusion risk. Transfus Clin Biol. 2005; 12 (1): 1– 4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bruce-Chwatt LJ. Blood transfusion and tropical disease. Trop Dis Bull. 1972; 69 (9): 825– 62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kitchen AD, Barbara JAJ, Hewitt PE. Documented cases of post-transfusion malaria occurring in England: a review in relation to current and proposed donor-selection guidelines. Vox Sang. 2005; 89 (2): 77– 80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chattopadhyay R, Majam VF, Kumar S. Survival of Plasmodium falciparum in human blood during refrigeration. Transfusion. 2011; 51 (3): 630– 5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Grant DB, Perinpanayagam MS, Shute PG, Zeitlin RA. A case of malignant tertian (Plasmodium falciparum) malaria after blood-transfusion. Lancet. 1960; 2 (7148): 469– 70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Seed CR, Kitchen A, Davis TM. The current status and potential role of laboratory testing to prevent transfusion-transmitted malaria. Transfus Med Rev. 2005; 19 (3): 229– 40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Dover AS, Guinee VF. Malaria transmission by leukocyte component therapy. JAMA. 1971; 217 (12): 1701– 2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Garfield MD, Ershler WB, Maki DG. Malaria transmission by platelet concentrate transfusion. JAMA. 1978; 240 (21): 2285– 6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wylie BR. Transfusion transmitted infection: viral and exotic diseases. Anaesth Intensive Care. 1993; 21 (1): 24– 30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Elghouzzi MH, Senegas A, Steinmetz T, Guntz P, Barlet V, Assal A, et al. Multicentric evaluation of the DiaMed enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay malaria antibody test for screening of blood donors for malaria. Vox Sang. 2008; 94 (1): 33– 40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Mollison PL, Engelfriet CP, Contreras M. Blood transfusion in clinical medicine. 10th ed. Oxford: Blackwell Science Ltd; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Shulman IA. Parasitic infections and their impact on blood donor selection and testing. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1994; 118 (4): 366– 70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Slinger R, Giulivi A, Bodie-Collins M, Hindieh F, John RS, Sher G, et al. Transfusion-transmitted malaria in Canada. CMAJ. 2001; 164 3: 377– 379. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Boyd MF. Epidemiology of malaria. In: Boyd MF, editor. Malariology. Philadelphia & London: WB Saunders Co; 1949. p. 551– 607. [Google Scholar]

- 23. World Health Organization Screening donated blood for transfusion transmissible infections: recommendations. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010. Available from: http://www.who.int/bloodsafety/ScreeningTTI.pdf . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Okwa OO. The status of malaria among pregnant women: a study in Lagos, Nigeria. Afr J Reprod Health. 2003; 7 (13): 77– 83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Fugikaha E, Fornazari PA, Penhalbel RSR, Lorenzetti A, Maroso RD, Amoras JT, et al. Molecular screening of Plasmodium sp. asymptomatic carriers among transfusion centers from Brazilian Amazon region. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 2007; 49 (1): 1– 4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Sadrizadeh B. Malaria in the world, in the Eastern Mediterranean Region and in Iran: review article. WHO/EMRO Report. 2001; 1: 1– 13. [Google Scholar]

- 27. http://original.antiwar.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/12/Iran-provinces-map.png

- 28. Edrissian GhH. Blood transfusion induced malaria in Iran. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1974; 68 (6): 491– 3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Edrissian GhH. Transfusion-transmitted malaria in Iran. J Med Counc Iran. 1985; 9( 5): 314– 23 [In Persian]. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Edrissian GhH. Induced malaria. J Med Counc Iran. 1975; 4( 6): 472– 9 [In Persian]. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Moghtadaei M, Edrissian GH, Amini Kafiabad S, Samiei Sh, Keshavarz H, Nateghpoor M. Application and evaluation of PCR in detection of malaria in donors of transfusion centers in Sistan-Baloochestan province in 2002. Sci J Iran Blood Transfus Organ. 2005; 2( 4): 105– 14 [In Persian]. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Sanei Moghaddam E, Khosravi S, Pousharifi M, Jafari F, Moghtadaei M. Malaria screening of blood donor in Zahedan. Sci J Iran Blood Transfus Organ. 2011; 8( 3): 165– 73 [In Persian]. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hassanpour G, Mohebali M, Raeisi A, Abolghasemi H, Zeraati H, Alipour M, et al. Detection of malaria infection in blood transfusion: a comparative study among real-time PCR, rapid diagnostic test and microscopy. Parasitol Res. 2011; 108 (6): 1519– 23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Cheesbrough M. District laboratory practice in tropical countries, Part 1. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Choudhury N. Transfusion transmitted infections: How many more? Asian J Transfus Sci. 2010; 4( 2): 71– 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Manouchehri AV, Zaim M, Emadi AM. A review of malaria in Iran, 1975–90. J Am Mosq Control Assoc. 1992; 8 (4): 381– 5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Edrissian GhH. Malaria in Iran: Past and present situation. Iranian J Parasitol. 2006; 1 (1): 1– 14. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Azizi MH, Nayernouri T, Bahadori M. The history of the foundation of the Iranian national blood transfusion service in 1974 and the biography of its founder; professor Fereydoun Ala. Arch Iran Med. 2015; 18 (6): 393– 400. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Pourfathollah AA, Hosseini Divkolaye NS, Seighali F. Four decades of national blood service in Iran: outreach, prospect and challenges. Transfus Med. 2015; 25 (3): 138– 43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Cheraghali AM. Overview of blood transfusion system of Iran: 2002–2011. Iran J Public Health. 2012; 41 (8): 89– 93. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Maghsudlu M, Nasizadeh S, Abolghasemi H, Ahmadyar S. Blood donation and donor recruitment in Iran from 1998 through 2007: ten years’ experience. Transfusion. 2009; 49 (11): 2346– 51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Abolghasemi H, Maghsudlu M, Amini Kafiabad S, Cheraghali A. Introduction to Iranian blood transfusion organization and blood safety in Iran. Iran J Public Health. 2009; 38 (Suppl 1): 82– 7. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Hemami MR, Sari AA, Raeisi A, Vatandoost H, Majdzadeh R. Malaria elimination in Iran, importance and challenges. Int J Prev Med. 2013; 4 (1): 88– 94. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]