Abstract

Vanishing bile duct syndrome (VBDS) has been described in different pathologic conditions including infection, ischemia, adverse drug reactions, autoimmune diseases, allograft rejection, and humoral factors associated with malignancy. It is an acquired condition characterized by progressive destruction and loss of the intra-hepatic bile ducts leading to cholestasis. Prognosis is variable and partially dependent upon the etiology of bile duct injury. Irreversible bile duct loss leads to significant ductopenia, biliary cirrhosis, liver failure, and death. If biliary epithelial regeneration occurs, clinical recovery may occur over a period of months to years. VBDS has been described in a number of cases of patients with Hodgkin’s lymphoma (HL) where it is thought to be a paraneoplastic phenomenon. This case describes a 25-year-old man found on liver biopsy to have VBDS. Given poor response to medical treatment, the patient underwent transplant evaluation at that time and was found to have classical stage IIB HL. Early recognition of this underlying cause or association of VBDS, including laboratory screening, and physical exam for lymphadenopathy are paramount to identifying potential underlying VBDS-associated malignancy. Here we review the literature of HL-associated VBDS and report a case of diagnosed HL with biopsy proven VBDS.

Keywords: Cholestasis, Bile ductopenia, Vanishing bile duct syndrome, Hodgkin’s lymphoma, Liver

Core tip: Vanishing bile duct syndrome (VBDS) is a rare form of liver injury and can be caused by multiple etiologies including malignancy. It is therefore critical for physicians to create a broad differential when VBDS is suspected and diagnosed. Liver biopsy is critical and should not be deferred. Once the diagnosis of VBDS is confirmed on biopsy, aggressive therapy, adjunctive medical management of cholestasis, and supportive care is indicated as achieving remission and symptom management in Hodgkin’s lymphoma -associated VBDS is crucial. If hepatic recovery does not occur, liver transplantation should be considered.

INTRODUCTION

Vanishing bile duct syndrome (VBDS) refers to a group of acquired disorders associated with progressive destruction and disappearance of the intra-hepatic bile ducts leading to cholestasis[1]. Although the pathogenesis is poorly understood, VBDS has been associated with potential infectious etiologies, ischemia, autoimmune diseases, adverse drug reactions, and humoral factors associated with malignancy (Table 1)[2]. Hodgkin’s Lymphoma (HL)-related VBDS is thought to be a paraneoplastic process which typically presents with jaundice, pruritus, and weight loss[3]. Here we extensively review available literature addressing HL-associated VBDS and report a case of HL with biopsy proven VBDS.

Table 1.

Causes of vanishing bile duct syndrome1

| Medications | Non-FDA approved weight loss supplements, sertraline, temozolomide, oxcarbazepine, levofloxacin,ibuprofen, sulfamethoxaxzole-trimethoprim, meropenom, lamotrigine , valproic acid, azithromycin, moxifloxacin, chlorpromazine, carbamazepine, interferon, mycophenolate mofetil, anabolic steroids, allopurinol |

| Infections | Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), cytomegalovirus (CMV), Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), cryptosporidium, reovirus type 3 |

| Malignancy | Lymphoma (B-cell, T-cell rich B-cell, Hodgkin’s, non-Hodgkin’s, and anaplastic large cell) |

| Immunologic | Primary biliary cholangitis, primary sclerosing cholangitis, sarcoidosis, chronic graft vs host disease |

Not a comprehensive list.

CASE REPORT

A 25-year-old man with past medical history significant for depression presented to the hospital with two-weeks of nausea and abdominal discomfort accompanied by loose, blood-tinged stools, and tenesmus. He denied recent travel and family history was only significant for a distant cousin with ulcerative colitis. The patient worked as a baker in a local pastry shop. He reported active tobacco use, social alcohol consumption, and occasional marijuana use, though no illicit substance abuse. His medications included bupropion for depression and omeprazole for occasional reflux symptoms.

On initial physical exam, he was noted to be febrile to 102 degrees Fahrenheit, markedly jaundice with icteric sclera bilaterally, and tenderness to palpation in the epigastric region of his abdomen without rebound, guarding, or organomegaly. The remainder of his exam was unremarkable aside from mild bipedal edema. Labs were significant for alkaline phosphatase (ALP) of 818 U/L, total protein of 4.5 g/dL, albumin of 2.5 g/dL, alanine aminotransferase (ALT)/aspartate aminotransferase (AST) of 146/144 U/L, total bilirubin/direct bilirubin of 6.2/3.9 mg/dL, and INR of 2.23. Remaining laboratory data including the complete blood count were within normal limits. Stool studies were negative other than positive fecal leukocytes. Viral hepatitis panel, anti-nuclear antibody (ANA), and an acetaminophen level were also negative.

Computerized tomography (CT) of the abdomen and pelvis showed mild to moderate circumferential thickening of the entire colon without peri-colonic fat stranding. Given the cholestatic pattern, magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) was obtained and unremarkable. The patient underwent a colonoscopy that showed no focal ulcers, but continuous erythema and edema of the mucosa from rectum to the cecum consistent with a pan-colitis. The terminal ileum was also noted to be inflamed. Random biopsies suggested epithelial injury secondary to ischemia, drug/toxin effect, or an enteroinvasive infection.

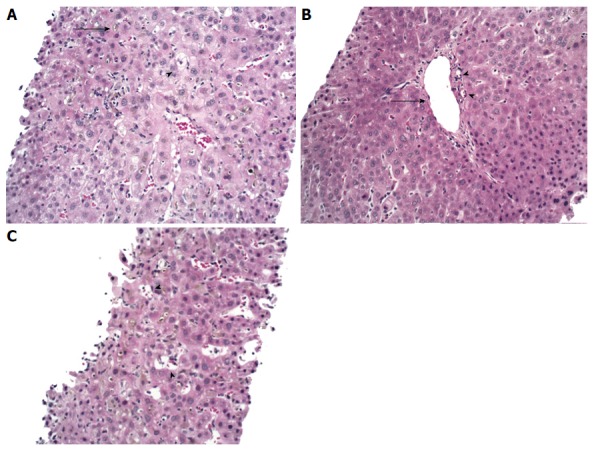

During the patient’s hospital course, his coagulopathy was corrected with phytonadione, his liver function remained stable, and abdominal pain resolved with supportive care. He was subsequently discharged; however, the patient was re-admitted with worsening cholestasis in setting of Influenza A. He was treated with oseltamivir and was initiated on ursodeoxycholic acid. ALP remained elevated at 501 U/L, while liver enzymes down trended (ALT/AST of 77/55 U/L). Despite this, the patient was found to have a worsening hyperbilirubinemia (total bilirubin/direct bilirubin of 6.2/3.9 mg/dL). Liver biopsy was obtained, which showed cholestatic hepatitis with ductopenia, consistent with VBDS (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Liver biopsy. A: The lobular parenchyma has marked cholestasis (arrow) with a zone 3 accentuation, associated with occasional feathery hepatocyte degeneration (arrowhead) and mild inflammation; B: Portal tract with portal vein (arrow) and two branches of hepatic arterioles (arrowheads) with missing bile duct; C: Ito cell lipidosis (arrowheads) were also seen. Hematoxylin-eosin staining, magnification × 200.

Given a static course without improvement over a three month period and follow-up biopsy noting persistent ductopenia, liver transplant workup was initiated. CT chest performed during transplant evaluation revealed a soft tissue density mass in the left hilar region. Biopsies of the lymph node confirmed classical stage IIB HL. He later developed worsening edema which was attributed to nephrotic syndrome. He began treatment at an outside facility with nitrogen mustard and high dose corticosteroids combined with radiation therapy and ultimately gemcitabine/oxaliplatin for disease outside of chest. The patient responded to treatment and achieved remission of HL. However, he has had persistent cholestasis and a recent transjugular liver biopsy revealed portal hypertension, continued bile duct loss and an increase in ductular proliferation and sinusoidal fibrosis. He has ascites and a Model for End Stage Liver Disease- Sodium score most recently of 23. The goal of current therapy is to manage portal hypertension and hope to achieve a recurrence free interval to consider future transplantation.

The patient subsequently underwent extended genetic panel sequencing to evaluate potential molecular defects in bile acid transport or synthesis. Next-generation whole exome sequencing identified a heterozygous missense variant of undetermined significance in the macrophage stimulating (MST1) gene, C265Y (chromosome 3: 49724179, TGC>TAC, hg19). This change is located in a highly conserved residue in evolution and is not found in the general population. Primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) show consistent association with common single nucleotide polymorphisms in the MST1 locus in population studies. The significance of rare variants in this gene is not known in the context of PSC or IBD and is a unique finding that may have a future role in testing in similar clinical presentations.

DISCUSSION

Here we present a case of VBDS in the setting of HL. The association between VBDS and HL, first detailed in 1993 by Hubscher et al[4], has subsequently been described in a number of published cases to date (Table 2)[3-39]. The first three patients, described by Hubscher et al[4], ultimately progressed to hepatic failure[4]. Even when hepatic failure does not occur, VBDS associated with HL may predict poor overall survival and prognosis.

Table 2.

Reported literature involving the association between vanishing bile duct syndromand Hodgkin’s lymphoma

| Author | Year | Liver biopsy | HL treatment (chemotherapy and/or XRT) | Outcome/cause of death |

| Our patient | 2014 | VBDS | Yes | Remission |

| Rota Scalabrini D | 2014 | VBDS | Yes | Remission |

| Nader K | 2013 | VBDS | Yes | Death/hepatic failure and sepsis |

| Aleem A | 2013 | VBDS | Yes | Death/hepatic failure |

| Wong KM | 2013 | VBDS | Yes | Remission |

| Umit H | 2009 | VBDS | Unknown | Unknown |

| Pass AK | 2008 | VBDS | Yes | Remission/awaiting liver transplant |

| Pass AK | 2008 | VBDS | Yes | Death/aspiration |

| Leeuwenburgh I | 2008 | VBDS | Yes | Remission |

| DeBenedet AT | 2008 | VBDS | Yes | Death/unknown |

| Ballonoff A | 2007 | VBDS | Yes | Remission |

| Barta SK | 2006 | IC | Yes | Remission |

| Schmitt A | 2006 | VBDS | No | Death/sepsis |

| Han WS | 2005 | VBDS | Unknown | Recurrent HL |

| Cordoba Iturriagagaitia A | 2005 | VBDS | Unknown | Remission |

| Guliter S | 2004 | VBDS | Yes | Death/sepsis |

| Liangpunsakul S | 2002 | Cholestatic hepatitis | Yes | Remission |

| Komurcu S | 2002 | VBDS | Yes | Death/hepatic failure |

| Ripoll C | 2002 | VBDS | Yes | Death/hepatic failure |

| Ripoll C | 2002 | VBDS | Yes | Remission |

| Ozkan A | 2001 | VBDS | Yes | Death/hepatic failure |

| Allory Y | 2000 | VBDS | Unknown | Unknown |

| Rossini MS | 2000 | VBDS | Yes | Death/hepatic failure |

| Yusuf MA | 2000 | VBDS | Yes | Death/hepatic failure |

| Dourakis SP | 1999 | Hepatocellular necrosis | Yes | Death/hepatic failure |

| Yalcin S | 1999 | IC | No | Death/sepsis |

| Yalcin S | 1999 | IC | Yes | Remission |

| De Medeiros BC | 1998 | VBDS | Yes | Death/hepatic failure |

| De Medeiros BC | 1998 | VBDS | Yes | Remission |

| Crosbie OM | 1997 | VBDS | Yes | Remission |

| Gottrand F | 1997 | VBDS | No | Death/hepatic failure |

| Warner AS | 1994 | IC | Yes | Remission |

| Jansen PLM | 1994 | IC | Yes | Death/variceal hemorrhage |

| Hubscher SG | 1993 | VBDS | Yes | Death/pneumonia |

| Hubscher SG | 1993 | VBDS | Yes | Death/unknown |

| Hubscher SG | 1993 | VBDS | Yes | Death/sepsis |

| Birrer MJ | 1987 | IC | Yes | Death/sepsis |

| Lieberman DA | 1986 | IC | No | Death/respiratory arrest |

| Trewby PN | 1979 | IC | Yes | Remission |

| Trewby PN | 1979 | Mild portal hepatitis | No | Death |

| Trewby PN | 1979 | Lymphoma infiltration | Yes | Death |

| Trewby PN | 1979 | Lymphoma infiltration | No | Death |

| Trewby PN | 1979 | Mixed inflammatory and atypical histiocytes | Yes | Remission |

| Trewby PN | 1979 | IC | Yes | Death/hepatic failure |

| Piken EP | 1979 | IC | Yes | Death/unknown |

| Perera DR | 1974 | IC | Yes | Death/hepatic failure |

| Perera DR | 1974 | IC | Yes | Remission |

| Perera DR | 1974 | IC | Yes | Remission |

| Groth C | 1972 | IC | Yes | Death/hepatic failure |

| Juniper K | 1963 | IC | Yes | Death/hepatic failure |

| Bouroncle B | 1962 | IC | Yes | Death/hepatic failure |

| Bouroncle B | 1962 | IC | Yes | Death/hepatic failure |

HL: Hodgkin’s lymphoma; VBDS: Vanishing bile duct syndrome; IC: Idiopathic cholestasis.

Hepatic involvement with HL may be seen in as many as 50% of patients. Though VBDS is rare, liver injury in VBDS has a high mortality in an otherwise curable disease. Other conditions that may cause jaundice in HL include biliary obstruction secondary to lymph node enlargement, hemolysis, and other viral illnesses, most commonly cytomegalovirus[5]. While hepatic failure is a major cause of mortality amongst patients with HL-related VBDS, many of the case reports reviewed noted complete remission with lymphoma treatment and improvement of hepatic function.

Patients with HL-related VBDS typically present with jaundice, pruritus, and weight loss as seen in the patient reported above[3]. Treatment revolves around treating the underlying cause. Appropriate therapy must balance the need for aggressive chemoradiation to achieve remission but is also limited by the degree of liver dysfunction. Treatment and decisions on when to treat remain difficult as there exists a delicate balance between aggressive chemoradiation regimens and worsening cholestasis. Many previous cases published in the literature utilized full dose chemotherapy or a reduced dose to treat the underlying malignancy. Despite a difference in dosage, some patients were cured while others succumbed to liver failure.

Radiotherapy has been shown to improve liver failure free survival. While chemoradiation is a treatment option, many cases ultimately lead to significant liver dysfunction requiring liver transplantation. Some authors feel HL-associated VBDS is irreversible and patients should therefore be considered for liver transplantation regardless of remission, though this remains controversial given the limited data and rarity of this syndrome[4,8,17,33]. Pass et al[29] reported on a patient awaiting liver transplant however the outcome of this case is unknown. They reported that early measures should be taken to prepare for liver transplant starting with aggressive treatment for HL remission with subsequent liver transplant evaluation. Our patient did not receive treatment at our institution though sought treatment with MOPP (mechlorethamine, vincristine, procarbazine, and prednisone). He showed improvement in regards to biliary regeneration and liver function and will be followed for consideration for liver transplantation should this become necessary.

The decision and timing of treatment of this disease is a challenge. The preferred treatment of HL-related VBDS is complex and controversial, driven largely by the fact that the mechanism of VBDS in HL remains unclear. Differing theories have proposed cell-mediated immunologic reactions or toxic cytokines derived from lymphoma cells that lead to ductopenia[1,9,40]. Alternative proposals postulate biliary epithelial cells are damaged due to cross reactive T cells recognizing auto-antigens leading to apoptosis of biliary epithelium[40-42]. Previous studies have shown the expression of major histo-compatibility complex as well as intercellular adhesion molecules in response to cytokines produced by HL[43]. Given the presumed immunological reaction causing VBDS, treatments targeting this response have been attempted. Rituximab, a chimeric monoclonal antibody against CD20 frequently expressed in HL, has been used with positive outcomes[44,45]. Rituximab may have a therapeutic role in CD20-negative patients given this presumed immunological reaction causing VBDS[45]. Apheresis treatment, in addition to chemotherapy and radiotherapy, has also been reported effective in curing patients with VBDS[46].

VBDS, colitis, and later nephrotic syndrome diagnosed in the setting of volume overload and edema, were all believed to be paraneoplastic manifestations of our patient’s underlying HL. Based upon the literature review and our patient’s presentation, cholestasis appears to be the predominant symptom of HL in patients who were found to have VBDS. This has been previously described by Hallén et al[46] who reported on a patient with severe hyperbilirubinemia in the setting of VBDS with subsequent diagnosis of HL. Strategies to improve cholestasis such as ursodeoxycholic acid and cholestyramine may benefit patient’s symptoms though limited data exists. Other treatment options have been recommended including rifampin which can improve bilirubin levels and symptoms of pruritus[47]. Hallén et al[46] additionally described the use of bilirubin apheresis treatment with an anion exchange adsorbent column for the reduction of bilirubin and bile acids with good symptomatic effect.

In summary, this case highlights the importance of exercising an exhaustive investigation into all potential causes of VBDS when the diagnosis is made - especially underlying malignancy[48]. Based on previous published case presentations, patients do not appear to recover from impaired liver function without achieving a complete remission of HL. This highlights the need for practitioners to be aware of the association of HL with VBDS and evaluate patients with such presentation for underlying malignancy. Early recognition of this association, appropriate laboratory screening, and survey for lymphadenopathy are critical to identifying HL-associated VBDS[8,29]. Early aggressive treatment and regeneration of the biliary epithelium are paramount to achieve a successful outcome.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors have nothing to disclose. All authors listed have contributed sufficiently to the project to be included as authors, and all those who are qualified to be authors are listed in the author byline. All authors contributed equally to this manuscript.

COMMENTS

Case characteristics

A 25-year-old man with past medical history significant for depression presented to the hospital with two-weeks of nausea and abdominal discomfort accompanied by loose, blood-tinged stools, and tenesmus.

Clinical diagnosis

Jaundice, pruritus, and weight loss.

Differential diagnosis

Primary biliary cholangitis, primary sclerosing cholangitis, graft-vs-host disease, biliary obstruction due to mass.

Laboratory diagnosis

Labs were significant for alkaline phosphatase of 818 U/L, total protein of 4.5 g/dL, albumin of 2.5 g/dL, alanine aminotransferase/aspartate aminotransferase of 146/144 U/L, total bilirubin/direct bilirubin of 6.2/3.9 mg/dL, and INR of 2.23.

Imaging diagnosis

Computerized tomography chest revealed a soft tissue density mass in the left hilar region.

Pathological diagnosis

Cholestatic hepatitis with ductopenia and classical stage IIB Hodgkin’s lymphoma.

Treatment

Nitrogen mustard and high dose corticosteroids combined with radiation therapy.

Related reports

Vanishing bile duct syndrome (VBDS) is a rare disease defined by the loss of intrahepatic bile ducts leading to ductopenia and cholestasis. Early recognition of potential underlying VBDS associated malignancy is critical.

Term explanation

VBDS refers to a group of acquired disorders associated with progressive destruction and disappearance of the intra-hepatic bile ducts leading to cholestasis.

Experiences and lessons

Early recognition of underlying HL-related VBDS, early aggressive treatment, cholestasis management, and liver transplantation evaluation are paramount to achieve successful outcomes in patients with HL-related VBDS.

Peer-review

The paper is well-written.

Footnotes

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: United States

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

Institutional review board statement: This case report was exempt from the Institutional Review Board standards at Yale-New Haven Hospital.

Conflict-of-interest statement: No authors have personal, financial, or other conflicts of interest to disclose.

Peer-review started: April 26, 2016

First decision: June 20, 2016

Article in press: August 5, 2016

P- Reviewer: Garcia-Olmo D, Lennerz JKM, Yoshida M S- Editor: Yu J L- Editor: A E- Editor: Liu WX

References

- 1.Nakanuma Y, Tsuneyama K, Harada K. Pathology and pathogenesis of intrahepatic bile duct loss. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2001;8:303–315. doi: 10.1007/s005340170002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reau NS, Jensen DM. Vanishing bile duct syndrome. Clin Liver Dis. 2008;12:203–217, x. doi: 10.1016/j.cld.2007.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wong KM, Chang CS, Wu CC, Yin HL. Hodgkin’s lymphoma-related vanishing bile duct syndrome: a case report and literature review. Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 2013;29:636–641. doi: 10.1016/j.kjms.2013.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hubscher SG, Lumley MA, Elias E. Vanishing bile duct syndrome: a possible mechanism for intrahepatic cholestasis in Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Hepatology. 1993;17:70–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rota Scalabrini D, Caravelli D, Carnevale Schianca F, D’Ambrosio L, Tolomeo F, Boccone P, Manca A, De Rosa G, Nuzzo A, Aglietta M, et al. Complete remission of paraneoplastic vanishing bile duct syndrome after the successful treatment of Hodgkin’s lymphoma: a case report and review of the literature. BMC Res Notes. 2014;7:529. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-7-529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aleem A, Al-Katari M, Alsaleh K, AlSwat K, Al-Sheikh A. Vanishing bile duct syndrome in a Hodgkin’s lymphoma patient with fatal outcome despite lymphoma remission. Saudi J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:286–289. doi: 10.4103/1319-3767.121037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Allory Y, Métreau J, Zafrani E. [Paraneoplastic vanishing bile duct syndrome in a case of Hodgkin’s disease] Ann Pathol. 2000;20:52–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ballonoff A, Kavanagh B, Nash R, Drabkin H, Trotter J, Costa L, Rabinovitch R. Hodgkin lymphoma-related vanishing bile duct syndrome and idiopathic cholestasis: statistical analysis of all published cases and literature review. Acta Oncol. 2008;47:962–970. doi: 10.1080/02841860701644078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barta SK, Yahalom J, Shia J, Hamlin PA. Idiopathic cholestasis as a paraneoplastic phenomenon in Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma. 2006;7:77–82. doi: 10.3816/CLM.2006.n.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Birrer MJ, Young RC. Differential diagnosis of jaundice in lymphoma patients. Semin Liver Dis. 1987;7:269–277. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1040582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bouroncle BA, Old JW, Vazques AG. Pathogenesis of jaundice in Hodgkin’s disease. Arch Intern Med. 1962;110:872–883. doi: 10.1001/archinte.1962.03620240054009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Córdoba Iturriagagoitia A, Iñarrairaegui Bastarrica M, Pérez de Equiza E, Zozaya Urmeneta JM, Martínez-Peñuela JM, Beloqui Pérez R. [Ductal regeneration in vanishing bile duct syndrome in Hodgkin’s lymphoma] Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;28:275–278. doi: 10.1157/13074061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Crosbie OM, Crown JP, Nolan NP, Murray R, Hegarty JE. Resolution of paraneoplastic bile duct paucity following successful treatment of Hodgkin’s disease. Hepatology. 1997;26:5–8. doi: 10.1002/hep.510260101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.de Medeiros BC, Lacerda MA, Telles JE, da Silva JA, de Medeiros CR. Cholestasis secondary to Hodgkin’s disease: report of 2 cases of vanishing bile duct syndrome. Haematologica. 1998;83:1038–1040. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.DeBenedet AT, Berg CL, Enfield KB, Woodford RL, Bennett AK, Northup PG. A case of vanishing bile duct syndrome and IBD secondary to Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Nat Clin Pract Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;5:49–53. doi: 10.1038/ncpgasthep1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dourakis SP, Tzemanakis E, Deutsch M, Kafiri G, Hadziyannis SJ. Fulminant hepatic failure as a presenting paraneoplastic manifestation of Hodgkin’s disease. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1999;11:1055–1058. doi: 10.1097/00042737-199909000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gottrand F, Cullu F, Mazingue F, Nelken B, Lecomte-Houcke M, Farriaux JP. Intrahepatic cholestasis related to vanishing bile duct syndrome in Hodgkin’s disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1997;24:430–433. doi: 10.1097/00005176-199704000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Groth CG, Hellström K, Hofvendahl S, Nordenstam H, Wengle B. Diagnosis of malignant lymphoma at laparotomy disclosing intrahepatic cholestasis. Acta Chir Scand. 1972;138:186–189. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guliter S, Erdem O, Isik M, Yamac K, Uluoglu O. Cholestatic liver disease with ductopenia (vanishing bile duct syndrome) in Hodgkin’s disease: report of a case. Tumori. 2004;90:517–520. doi: 10.1177/030089160409000516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Han WS, Jung ES, Kim YH, Kim CH, Park SC, Lee JY, Chang YJ, Yeon JE, Byun KS, Lee CH. [Spontaneous resolution of vanishing bile duct syndrome in Hodgkin’s lymphoma] Korean J Hepatol. 2005;11:164–168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jansen PL, van der Lelie H. Intrahepatic cholestasis and biliary cirrhosis associated with extrahepatic Hodgkin’s disease. Neth J Med. 1994;44:99–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Juniper K. Prolonged severe obstructive jaundice in Hodgkin’s disease. Gastroenterology. 1963;44:199–204. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kömürcü S, Ozet A, Altundag MK, Arpaci F, Oztürk B, Celasun B, Tezcan Y. Vanishing bile duct syndrome occurring after high-dose chemotherapy and autologous peripheral stem cell transplantation in a patient with Hodgkin’s disease. Ann Hematol. 2002;81:57–58. doi: 10.1007/s00277-001-0406-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leeuwenburgh I, Lugtenburg EP, van Buuren HR, Zondervan PE, de Man RA. Severe jaundice, due to vanishing bile duct syndrome, as presenting symptom of Hodgkin’s lymphoma, fully reversible after chemotherapy. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;20:145–147. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e3282b9e6c2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liangpunsakul S, Kwo P, Koukoulis GK. Hodgkin’s disease presenting as cholestatic hepatitis with prominent ductal injury. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2002;14:323–327. doi: 10.1097/00042737-200203000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lieberman DA. Intrahepatic cholestasis due to Hodgkin’s disease. An elusive diagnosis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1986;8:304–307. doi: 10.1097/00004836-198606000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nader K, Mok S, Kalra A, Harb A, Schwarting R, Ferber A. Vanishing bile duct syndrome as a manifestation of Hodgkin’s lymphoma: a case report and review of the literature. Tumori. 2013;99:e164–e168. doi: 10.1177/030089161309900426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ozkan A, Yoruk A, Celkan T, Apak H, Yildiz I, Ozbay G. The vanishing bile duct syndrome in a child with Hodgkin disease. Med Pediatr Oncol. 2001;36:398–399. doi: 10.1002/mpo.1096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pass AK, McLin VA, Rushton JR, Kearney DL, Hastings CA, Margolin JF. Vanishing bile duct syndrome and Hodgkin disease: a case series and review of the literature. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2008;30:976–980. doi: 10.1097/MPH.0b013e31818b37c4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Perera DR, Greene ML, Fenster LF. Cholestasis associated with extrabiliary Hodgkin’s disease. Report of three cases and review of four others. Gastroenterology. 1974;67:680–685. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Piken EP, Abraham GE, Hepner GW. Investigation of a patient with Hodgkin’s disease and cholestasis. Gastroenterology. 1979;77:145–147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ripoll C, Carretero L, Sabin P, Alvarez E, Marrupe D, Banares R. Idiopathic cholestasis associated with progressive ductopenia in two patients with hodgkin’s disease. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2002;25:313–315. doi: 10.1016/s0210-5705(02)79026-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rossini MS, Lorand-Metze I, Oliveira GB, Souza CA. Vanishing bile duct syndrome in Hodgkin’s disease: case report. Sao Paulo Med J. 2000;118:154–157. doi: 10.1590/S1516-31802000000500008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schmitt A, Gilden DJ, Saint S, Moseley RH. Clinical problem-solving. Empirically incorrect. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:509–514. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcps051762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Trewby PN, Portmann B, Brinkley DM, Williams R. Liver disease as presenting manifestation of Hodgkin’s disease. Q J Med. 1979;48:137–150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Umit H, Unsal G, Tezel A, Soylu AR, Pamuk GE, Turgut B, Demir M, Tucer D, Ermantas N, Cevikbas U. Vanishing bile duct syndrome in a patient with Hodgkin’s lymphoma and asymptomatic hepatitis B virus infection. Acta Gastroenterol Belg. 2009;72:277–278. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Warner AS, Whitcomb FF. Extrahepatic Hodgkin’s disease and cholestasis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1994;89:940–941. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yalçin S, Kars A, Sökmensüer C, Atahan L. Extrahepatic Hodgkin’s disease with intrahepatic cholestasis: report of two cases. Oncology. 1999;57:83–85. doi: 10.1159/000012005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yusuf MA, Elias E, Hübscher SG. Jaundice caused by the vanishing bile duct syndrome in a child with Hodgkin lymphoma. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2000;22:154–157. doi: 10.1097/00043426-200003000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Strazzabosco M, Fabris L, Spirli C. Pathophysiology of cholangiopathies. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2005;39:S90–S102. doi: 10.1097/01.mcg.0000155549.29643.ad. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Woolf GM, Vierling JM. Disappearing intrahepatic bile ducts: the syndromes and their mechanisms. Semin Liver Dis. 1993;13:261–275. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1007354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vierling JM, Howell CD. Disappearing bile ducts: immunologic mechanisms. Hosp Pract (Off Ed) 1990;25:141–150. doi: 10.1080/21548331.1990.11703976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Adams DH, Hubscher SG, Shaw J, Rothlein R, Neuberger JM. Intercellular adhesion molecule 1 on liver allografts during rejection. Lancet. 1989;2:1122–1125. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(89)91489-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Maeda LS, Advani RH. The emerging role for rituximab in the treatment of nodular lymphocyte predominant Hodgkin lymphoma. Curr Opin Oncol. 2009;21:397–400. doi: 10.1097/CCO.0b013e32832f3ca3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Saini KS, Azim HA, Cocorocchio E, Vanazzi A, Saini ML, Raviele PR, Pruneri G, Peccatori FA. Rituximab in Hodgkin lymphoma: is the target always a hit? Cancer Treat Rev. 2011;37:385–390. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2010.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hallén K, Sangfelt P, Nilsson T, Nordgren H, Wanders A, Molin D. Vanishing bile duct-like syndrome in a patient with Hodgkin lymphoma - pathological development and restitution. Acta Oncol. 2014;53:1271–1275. doi: 10.3109/0284186X.2014.897001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kremer AE, Bolier R, van Dijk R, Oude Elferink RP, Beuers U. Advances in pathogenesis and management of pruritus in cholestasis. Dig Dis. 2014;32:637–645. doi: 10.1159/000360518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bakhit M, McCarty TR, Park S, Njei B, Cho M, Karagozian R, Liapakis A. Vanishing Bile Duct Syndrome in Hodgkin’s Lymphoma: A Single Center Experience and Clinical Pearls. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2016;50:688. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000000548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]