Abstract

Background

Tick-borne flaviviruses (TBFs) cause thousands of human cases of encephalitis worldwide each year, with some TBF infections progressing to hemorrhagic fever. TBFs are of medical and veterinary importance and strategies to reduce flavivirus transmission by the tick vector may have significant application. Analyses of the proteome of ISE6 cells derived from the black legged tick, Ixodes scapularis infected with the TBF, Langat virus (LGTV), have provided insights into proteins and cellular processes involved with LGTV infection.

Methods

RNA interference (RNAi)-induced knockdown of transcripts was used to investigate the role of ten tick proteins in the LGTV infection cycle in ISE6 cells. LGTV-infected cells were separately transfected with dsRNA corresponding to each gene of interest and the effect on LGTV genome replication and release of infectious virus was assessed by RT-qPCR and plaque assays, respectively.

Results

RNAi-induced knockdown of transcripts for two enzymes that likely function in amino acid, carbohydrate, lipid, terpenoid/polykeytide and vitamin metabolism, and a transcript for one protein of unknown function were associated with decreased replication of the LGTV genome and release of infectious virus from cells. The knockdown of transcripts for five enzymes predicted to function in metabolism, a protein likely associated with folding, sorting and degradation, and a protein of unknown function was associated with a decrease only in the amount of infectious LGTV released from cells.

Conclusions

These data suggest tick proteins potentially associated with metabolism and protein processing may be involved in LGTV infection of ISE6 cells. Our study provides information to begin to elucidate the function of these proteins and identify targets for the development of new interventions aimed at controlling the transmission of TBFs.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s13071-016-1944-0) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Ixodes scapularis, Tick-borne disease, Flavivirus, Langat, ISE6, RNAi, Functional studies, Metabolism, Protein-processing

Background

Tick-borne flaviviruses (TBFs) impact human and animal health worldwide. These positive, single-stranded RNA viruses are transmitted by an infected tick (subphlym Chelicerata, subclass Acari, family Ixodidae) during blood-feeding. Tick-borne encephalitis virus (TBEV), Powassan virus (POWV), Kyasanur Forest Disease virus (KFDV) and Omsk hemorrhagic fever virus (OHFV) are members of the TBF complex and can cause encephalitis (TBEV and POWV) and hemorrhagic fever (KFDV and OHFV). Many TBFs are considered a biosecurity threat and are classified as biosafety containment level (BSL) three or four. Research is ongoing to develop vaccines and therapeutics to prevent or treat TBF infections. The less virulent Langat virus (LGTV), classified BSL-2, has been widely used as a model for more virulent TBFs. Many studies have employed LGTV and cell lines derived from the black-legged tick, Ixodes scapularis to investigate viral pathogenesis in the tick host cell, although I. scapularis is not a natural vector of LGTV.

Studies to understand the pathogenesis of tick-virus interactions will benefit from the recently published assembly of the I. scapularis genome. As the first such resource for a tick vector of disease [1–3], the assembly is expected to help advance investigations of tick-virus interactions at the molecular level. Proteomic studies have identified hundreds of I. scapularis proteins [4–7] and helped to define the proteome of this vector. Using mass spectrometry, Grabowski et al. identified 486 proteins in the I. scapularis ISE6 cell line, 266 of which were differentially regulated in cells infected with LGTV [4]. Proteins likely associated with metabolic processes exhibited increased or decreased expression following LGTV infection. These and other studies [7–9] provide a logical starting point for detailed molecular research to determine the role of tick proteins during the TBF life-cycle in the vector.

RNA interference (RNAi) is a tool widely used for functional studies of arthropod proteins, including proteins produced by the I. scapularis IDE8 cell line during infection with flavivirus [7–9]. At least one of these studies suggests induction of the RNAi-based antiviral pathway identified in other organisms and a role for Argonaute and Dicer in suppression of LGTV genome replication [9], although a role for the RNAi-pathway protein, Tudor-SN in LGTV replication or release of infectious virus is questioned [8]. Other IDE8 gene products implicated in the antiviral response of the tick cell against LGTV include Factor H, trypsin, HSP90 and HSP70 [7], with the latter two proteins predicted to function in protein folding and/or processing. Previous studies shed light on lipids and metabolic processes potentially manipulated by dengue virus (DENV) to facilitate infection and replication in human and mosquito systems [10–12]. Equivalent studies are required to better understand metabolic processes affected during tick-flavivirus interaction.

Efforts are underway to develop new transmission-blocking technologies that target proteins produced by the host cell (i.e. host factors) that are essential to virus infection and replication [13–16]. Here, we investigated the hypothesis that proteins which exhibited increased expression in LGTV-infected I. sapularis ISE6 cells and are predicted to function in (i) the metabolism of amino acids, vitamins/cofactors, carbohydrates, nucleotides and lipids, (ii) DNA replication/repair or (iii) protein folding/sorting/degradation [4] are involved in flaviviral infection. The functional roles performed by these proteins during LGTV infection was pursued using loss-of-function, RNAi knockdown assays. Ten genes of interest were selected for analyses: fumarylacetoacetase (FAH; ISCW020196), endoplasmic reticulum protein 29 (ERP29; ISCW018425), aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH; ISCW015982), carbon-nitrogen hydrolase/pantetheine hydrolase/vanin-like (VNN; ISCW004822), malate dehydrogenase (MDH2; ISCW003528), poly [ADP-ribose] polymerase (PARP; ISCW019519), cytidine/uridine monophosphate kinase (CMPK; ISCW012446), acetyl-CoA acetyltransferase (ACAT1; ISCW016117) and two hypothetical proteins (Hypo195; ISCW011195 and Hypo576; ISCW020576). The process used to select these ten genes is summarized in Additional file 1: Figure S1. Transcripts corresponding to the above genes were confirmed in ISE6 cells and adult I. scapularis. Subsequently, ISE6 cells were separately transfected with dsRNA corresponding to each gene of interest, the knockdown of transcripts was confirmed by reverse transcriptase quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) and the effect on LGTV genome replication and release of infectious virus was assessed by RT-qPCR and plaque assay, respectively. Knockdown of transcripts for VNN, ACAT1, and Hypo576 was associated with decreased LGTV genome replication and LGTV release, while knockdown of transcripts for FAH, ERP29, ALDH, MDH2, CMPK, and Hypo195 was associated with decreased LGTV release only. These proteins are candidates for further functional analyses and studies aimed at development of new technologies to prevent transmission of TBF infection.

Methods

Cell and LGTV culture

The ISE6 cell line derived from I. scapularis embryonic cells (obtained from T. Kurtti, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN) was cultured at 34 °C in L15B-300 medium in the absence of CO2 [17, 18]. Baby hamster kidney 15 cells (BHK15) and Green African monkey kidney cells (Vero) originally obtained from American Tissue Culture Collection (ATCC), were cultured at 37 °C in Minimum Essential Medium (MEM) supplemented with L-glutamine, non-essential amino acids, and 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum (FCS) with 5% CO2. LGTV TP21 wildtype strain (passage 2) was obtained from A. Pletnev (NIH-NAID, Bethesda, MD) and amplified using a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 0.01 [19, 20] in Vero cells (cells were grown as described above, with 2.5% heat-inactivated FCS) to produce a working stock (passage 4). The titer of the LGTV p4 stock was determined via serial immunofluorescence assays (IFAs) in Vero cells using expression of the LGTV nonstructural protein 3 (NS3) as described by Junjhon et al. [21] and Grabowski et al. [4]. LGTV infection of ISE6 cells was performed using an MOI of 10 to achieve maximal infection of the cell population [4] and capture the synchronized release of the first population of infectious virus. Manual cell counts (cells/ml) were conducted using a hemocytometer [22] to quantify cell numbers before (a) seeding and (b) infection with LGTV.

Preparation of RNA from adult I. scapularis and ISE6 cells and cDNA synthesis

A single I. scapularis female collected by flagging from Tippecanoe State Park, Winamac, IN (October 29, 2013) was flash frozen in liquid N2 and ground in TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, USA) using mortar and pestle, and RNA was extracted as per manufacturer instructions. RNA was isolated from ISE6 cells (passage 96–100) grown in 96 well plates using the RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) and processed according to kit instructions. cDNA was synthesized from RNA samples using the iScript cDNA synthesis kit (BioRad, Hercules, USA). Thermocycler conditions used for cDNA synthesis were as follows: 25 °C for 5 min, 42 °C for 50 min, and 85 °C for 5 min.

Confirmation of transcripts for genes of interest in adult I. scapularis and ISE6 cells

Primers were designed using Primer3 software [23, 24] and NCBI Primer-BLAST [25] (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/tools/primer-blast/). GenBank accession numbers for the genes of interest are as follows: fumarylacetoacetase (FAH; XP_002407463), endoplasmic reticulum protein 29 (ERP29; XP_002435676), aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH; XP_002399265), carbon-nitrogen hydrolase/pantetheine hydrolase/vanin-like (VNN; XP_002402506), malate dehydrogenase (MDH2; XP_002402153), poly [ADP-ribose] polymerase (PARP; XP_002409668), cytidine/uridine monohydrate kinase (CMPK; XP_002413690), acetyl-CoA acetyltransferase (ACAT1; XP_002402965), hypothetical protein (Hypo195; XP_002411582), and hypothetical protein (Hypo576; XP_002408828). Primers were designed to amplify products ranging from 300 to 607 bp and spanning at least one intron (Additional file 1: Table S1).

PCR was conducted using Phusion high-fidelity PCR master mix with HF buffer (NE Biolabs, Ipswich, USA), cDNA template prepared from female I. scapularis or ISE6 cell RNA, and the following thermocycler conditions: 94 °C for 5 min; 32 cycles of 94 °C for 30 s, 58 °C for 30 s and 72 °C for 2 min, and 72 °C for 7 min. Following gel electrophoresis on 1.5% TBE agarose gel, amplicons of expected size were excised and purified using the Qiagen gel extraction kit (Qiagen) and the sequence was confirmed via direct sequencing at the Purdue Genomics Core Facility (PGCF), Purdue University.

Synthesis of dsRNA corresponding to I. scapularis genes of interest

T7-tagged cDNA template was generated using cDNA prepared from ISE6 cell RNA and T7-tagged primers (Additional file 1: Table S1). Two-step PCR was performed using the following thermocycler conditions: 94 °C for 5 min; 5 cycles at 94 °C for 30 s, 58 °C for 30 s, 72 °C for 2 min; 27 cycles at 94 °C for 30 s, 68 °C for 30 s, 72 °C for 2 min, and final extension at 72 °C for 7 min. dsRNA was synthesized from T7-tagged cDNA template using the MEGAscript RNAi synthesis kit according to manufacturer’s instructions and Barry et al. [26]. Conceptual cDNA sequences were searched by BLASTn against the I. scapularis IscaW1.4 transcript dataset at VectorBase (https://www.vectorbase.org/) to confirm the specificity of expected siRNA products for the target gene (i.e. to limit off-target effects).

Transfection of ISE6 cells with dsRNA and transcript knockdown

ISE6 cells were seeded at ~ 1 × 105 cells per well in 96-well flat-bottom cell culture plates pretreated with poly-L-lysine (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, USA). For dsRNA transfections, ISE6 cells were cultured for 48 h, following which half of the media was removed from each well and replaced with an equal volume of transfection mix (OptiMEM Reduced Serum Medium, Glutamax supplement [Invitrogen] and X-tremeGENE siRNA transfection reagent [Roche, Basel, Switzerland] prepared according to [26]) and 10 ng dsRNA per well. Cells were incubated for 60 h, following which media/transfection mix was removed and cells were incubated with resazurin salt (Sigma Aldrich) complete tick media (0.275 mM final concentration) for 12 h and cell viability was assessed via fluorescent readout on a Molecular Devices SpectraMax M5 plate reader coupled with SoftMax Pro v4.8 software (excitation at 560nm, emission at 590 nm) as described in Grabowski et al. [4]. In parallel, RNA was extracted from cells collected at 60 h post-transfection using RLT lysis buffer (from Qiagen RNeasy kit) to confirm knockdown of transcripts.

To assess the effect of dsRNA-mediated knockdown on replication of the LGTV genome, media/transfection mix was removed at 60 h post-transfection, cells were infected with LGTV (1 h rocking adsorption at room temperature), rinsed 3 times with 1× PBS, and incubated with fresh media for 12 h, following which RNA was extracted using RLT buffer for RT-qPCR analyses.

To assess the effect of dsRNA-mediated knockdown on the release of infectious LGTV, cells were either transfected with dsRNA (i) prior to (pre-treatment with dsRNA) or (ii) immediately following (post-treatment with dsRNA) LGTV infection. For pretreated cells, media/transfection mix was removed at 60 h post-transfection, cells were infected with LGTV (as above), rinsed 3 times with 1× PBS and incubated with fresh media for 16 h post-infection (hpi), following which media was collected for plaque assays. Post-treated cells were first infected with LGTV as above, rinsed three times with 1× PBS, incubated with media/transfection mix for 60 h and media was collected for plaque assays. Unpaired, two-tailed t-test statistical analyses were performed with GraphPad Prism (v4.03) software.

The amount of RNA extracted per 96-well following dsRNA transfections or LGTV infection ranged from 5.8 to 29.9 ng/μl. To confirm dsRNA-mediated knockdown of mRNA, the relative levels of ISE6 cell transcripts were determined using the Quantifast SYBR Green PCR kit (Qiagen) and RT-qPCR primers (Additional file 1: Table S2) relative to the I. scapularis β-actin gene. Primers targeting the negative strand of the replicative LGTV genome intermediate were used to quantify LGTV transcripts as described by Mitzel et al. [27] as a measure of LGTV genome replication relative to the β-tubulin gene. Reactions were performed on the Applied Biosystems 7300 PCR system (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, USA) in MicroAmp Optical 96-well reaction plates with labeled barcode (Life Technologies). The SDS RQ study software (v1.4.1) was used to collect raw Ct cycle values and the Comparative CT Method (ΔΔCt Method) [28, 29] was used to determine relative transcript expression and an unpaired, two-tailed t-test was performed with GraphPad Prism (v4.03) software.

Analysis of proteins using the DAVID functional clustering software

The annotation tool DAVID (http://david.abcc.ncifcrf.gov/ ) [30], was used to assign putative biological function to clusters of ISE6 proteins that exhibited increased expression following incubation with LGTV (LGTV), UV inactivated LGTV (UV-LGTV) or both (LGTV & UV-LGTV) identified in Grabowski et al. [4]. The GenBank accessions of orthologous proteins that mapped to I. scapularis KEGG pathways were used as input. Gene Ontology (GO) options were selected as output for DAVID clustering and an enrichment score of “≥1.3 is equal to a P-value ≤ 0.05” was used as cut-off. For each cluster, a modified Fisher’s exact test P-value ≤ 0.05 was used as an additional cut-off.

Prediction of protein-protein interactions using STRING

STRING (v9.1; string91.embl.de; [31, 32]) was used to predict protein-protein interactions for the conceptual products of the 10 genes analyzed in this study. Binding partners were predicted for each gene product using VectorBase accession ID as input and a cut-off score of ≥ 0.70 (high confidence score).

Results

Selection and characterization of I. scapularis genes of interest for dsRNA-mediated knockdown of ISE6 transcripts

Ten genes of interest were selected based on (i) evidence of increased protein expression following LGTV infection, (ii) quality of the protein identification data from LC-MS/MS (proteins supported by ≥ 2 peptides), and (iii) orthology to vertebrate/invertebrate proteins (based on KEGG) [4] (Additional file 1: Figure S1). The genes were fumarylacetoacetase (FAH; VectorBase accession ID ISCW020196), secreted protein (ERP29; ISCW018425), aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH; ISCW015982), carbon-nitrogen hydrolase (VNN; ISCW004822), malate dehydrogenase (MDH2; ISCW003528), poly [ADP-ribose] polymerase (PARP; ISCW019519), cytidine/uridine monophosphate kinase (CMPK; ISCW012446), acetyl-CoA acetyltransferase (ACAT1; ISCW016117), hypothetical protein (Hypo195; ISCW011195), and hypothetical protein (Hypo576; ISCW020576) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Summary of Ixodes scapularis genes selected for RNAi analyses

| Tick Protein; KEGGa Entry | I. scapularis VectorBase accession ID | GenBank accession number | Predicted function | % amino acid identity to H. sapiens ortholog | Location of gene on IscaW1 (scaffold: bp range) | Number of paralogs identified in IscaW1 assembly | Predicted number of protein binding partnersb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fumarylacetoacetase (FAH) | ISCW020196 | XP_002407463 | Amino acid metabolism | 65.9 | DS831757: 33,311–44,738 | – | 2 |

| Endoplasmic reticulum protein 29 (ERP29) | ISCW018425 | XP_002435676 | Protein folding, sorting, & degradation | 17 | DS758338: 84,585–88,966 | – | 0 |

| Aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH) | ISCW015982 | XP_002399265 | Amino acid metabolism | 56.7 | DS612682: 208,981–240,639 | 16 | 6 |

| Carbon-nitrogen hydrolase/pantetheine hydrolase/vanin-like (VNN) | ISCW004822 | XP_002402506 | Metabolism of cofactors & vitamins | 33.9 | DS712062: 22,027–47,303 | – | 0 |

| Malate dehydrogenase (MDH2) | ISCW003528 | XP_002402153 | Carbohydrate metabolism | 68.9 | DS711115: 47,872–64,175 | – | 21 |

| Poly [ADP-ribose] polymerase (PARP) | ISCW019519 | XP_002409668 | DNA replication & repair | 48.6 | DS807313: 23,492–74,749 | 2 | 30 |

| Cytidine/uridine monophosphate kinase (CMPK) | ISCW012446 | XP_002413690 | Nucleotide metabolism | 40.2 | DS915558: 7422–14,364 | 3 | 2 |

| Acetyl-CoA C-acetyltransferase (ACAT1) | ISCW016117 | XP_002402965 | Carbohydrate, lipid, amino acid, terpenoid/polykeytide metabolism | 60.2 | DS624476: 15,968–41,821 | 2 | 24 |

| Hypothetical protein (Hypo195) | ISCW011195 | XP_002411582 | Unknown | – | DS857119: 268,751–271,378 | – | – |

| Hypothetical protein (Hypo576) | ISCW020576 | XP_002408828 | Unknown | – | DS835548: 71,893–118,756 | – | – |

aKyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes; http://www.genome.jp/kegg/

bNumber of potential protein binding partners as predicted via STRING

The DAVID cluster analyses of biological function provided insight into the response of ISE6 cells to infection with LGTV and UV-LGTV. ISE6 cell proteins reported in Grabowski et al. [4] that exhibited increased expression following exposure to LGTV or UV-inactivated LGTV (i.e. assigned to one or more of the following four datasets: LGTV, UV-LGTV, LGTV/UV-LGTV or LGTV & UV-LGTV) and mapped to KEGG pathways, were used to identify “clusters of biological processes” (Additional file 1: Table S3). Of the 10 ISE6 proteins selected for knockdown studies, MDH2 and PARP were identified in the cluster “translation, ribosomal function, and protein metabolic processing”, FAH, ALDH, and CMPK in both “nitrogen metabolic processing” and “nitrogen/amine/amino acid metabolic processing” clusters, and ACAT1 in the cluster “nitrogen metabolic processing function”. FAH, ALDH, MDH2, PARP, and CMPK were also identified in the cluster “ribonucleoprotein/ribosomal/translation/protein metabolic function.”

Sequence similarity analyses revealed that four of the 10 proteins (ERP29, VNN, PARP, and CMPK) had < 50% amino acid identity to the human ortholog (Table 1). Searches of the I. scapularis genome revealed no evidence of paralogs for the genes FAH, ERP29, VNN, MDH2, Hypo195, and Hypo576. Analyses suggest that ALDH, PARP, CMPK, and ACAT1 are members of multi-gene families comprising 16, 2, 3, and 2 genes respectively (Table 1). STRING predicted multiple binding partners for PARP (30), ACAT1 (24), MDH2 (21), ALDH (6), FAH (2), and CMPK (2) in I. scapularis, suggesting these proteins may be associated with multiple protein-protein interactions and cellular processes. Binding partners were not predicted for ERP29 and VNN in I. scapularis.

Transcripts for the 10 genes of interest amplified from a single female I. scapularis or the ISE6 cell line had a minimum of 96% nucleotide identity to the corresponding IscaW1 gene model (Additional file 1: Table S4), suggesting significant conservation between the genome of the ISE6 cell line, field collected material, and the Wikel reference strain used to produce the IscaW1 genome assembly and annotation.

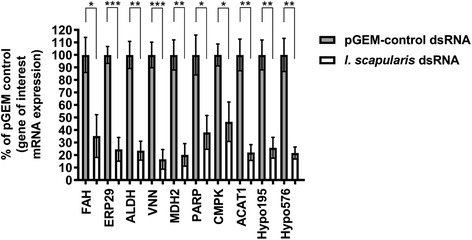

Confirmation of dsRNA-mediated knockdown of transcripts for genes of interest in ISE6 cells

In vitro studies using pGEM dsRNA revealed that 10 or 25 ng dsRNA had no significant effect (P ≤ 0.05) on viability of ISE6 cells (Additional file 1: Figure S2, Table S5). Subsequent RNAi knockdown experiments were conducted using 10 ng dsRNA and in vitro studies revealed no significant effect (P ≤ 0.05) of dsRNA treatment on cell viability of RNAi-treated cells (Additional file 1: Figure S3). In parallel, knockdown of transcripts for all ten genes of interest was confirmed using RT-qPCR (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

dsRNA-mediated knockdown of transcripts for I. scapularis genes of interest in ISE6 cells. Following transfection of ISE6 cells with 10 ng dsRNA for 60 h, total RNA was prepared from ~ 1 × 105 cells and cDNA was amplified via a two-step RT-PCR reaction. mRNA levels were normalized to I. scapularis β-actin and expressed relative to the percentage of pGEM control cDNA. Results show relative expression of ten I. scapularis genes of interest following knockdown (white bars) relative to the pGEM dsRNA negative control (gray bars). Error bars represent standard error of the mean (SEM). Statistical analysis was performed using an unpaired t-test between the negative pGEM control and dsRNA treatments for each gene of interest. Results represent 2–3 technical replicates (each with 2–3 machine replicates) and 2 biological replicates. *P ≤ 0.05; **P ≤ 0.01; ***P ≤ 0.001. Abbreviations: FAH, fumarylacetoacetase (ISCW020196); ERP29, endoplasmic reticulum protein 29 (ISCW018425); ALDH, aldehyde dehydrogenase (ISCW015982); VNN, carbon-nitrogen hydrolase/vanin-like (ISCW004822); MDH2, malate dehydrogenase (ISCW003528); PARP, poly [ADP-ribose] polymerase (ISCW019519); CMPK, cytidine/uridine monophosphate kinase (ISCW012446); ACAT1, acetyl-CoA acetyltransferase (ISCW016117); Hypo195, hypothetical protein (ISCW011195); Hypo576, hypothetical protein (ISCW020576); pGEM, pGEM plasmid (negative control)

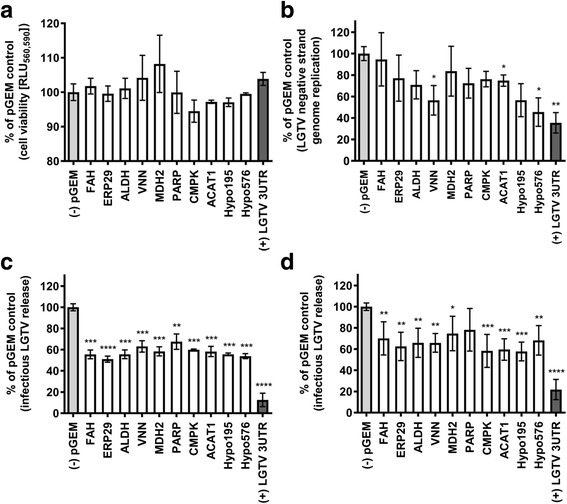

Effect of dsRNA-mediated knockdown of transcripts on LGTV infection

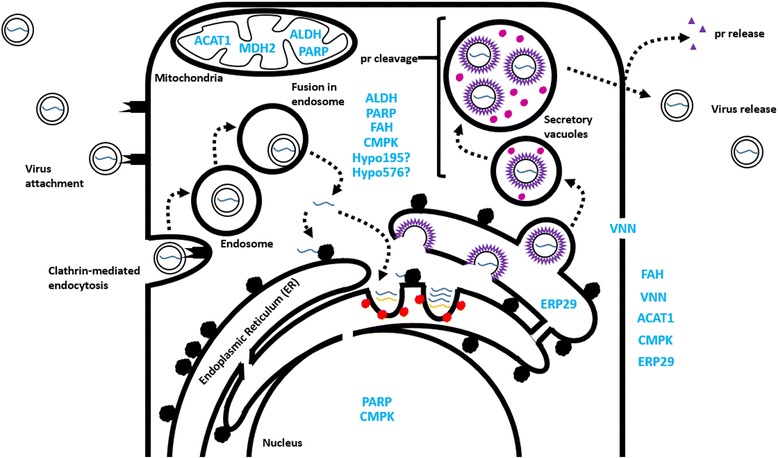

In vitro studies revealed no significant effect (P ≤ 0.05) on the viability of LGTV-infected ISE6 cells when dsRNA for the ten genes of interest was introduced either pre- or post-infection (Fig. 2a and Additional file 1: Figure S3, Table S5). dsRNA-mediated knockdown of transcripts for VNN, ACAT1, and Hypo576 revealed a decrease in relative levels (P ≤ 0.05) of the LGTV negative strand as compared to the negative pGEM control (Fig. 2b and Additional file 1: Table S5). Plaque assays showed that pre-treatment of ISE6 cells with dsRNA for all 10 genes of interest prior to LGTV infection resulted in a decrease (P ≤ 0.01) in the amount of infectious LGTV released from the cells (Fig. 2c and Additional file 1: Table S5), while treatment of ISE6 cells with dsRNA for all but one gene (PARP), following LGTV infection resulted in a decrease in amount (P ≤ 0.05) of infectious virus released from cells (Fig. 2d and Additional file 1: Table S5). The results of RNAi and LGTV infection studies (pre-treatment and post-treatment of cells with dsRNA) are summarized in Table 2. The location of expression of the 10 ISE6 proteins evaluated in this study was predicted using the program COMPARTMENTS and was based on homology to proteins from H. sapiens [33] (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2.

Effect of knockdown of I. scapularis transcripts on LGTV infection of ISE6 cells. a ISE6 cell viability following transfection with 10ng dsRNA for 60 h and 12 h post-infection (hpi) with LGTV, compared to the pGEM negative control. Results represent 2–5 technical replicates and 3 biological replicates. b Effect of I. scapularis transcript knockdown on LGTV genome replication in ISE6 cells following transfection with 10ng dsRNA for 60 h and 12 hpi with LGTV as compared to the negative control. Comparison of fold change in transcripts for the LGTV negative strand were normalized to the I. scapularis β-tubulin gene and expressed relative to percentage of pGEM control. Results represent 2 technical replicates (each with 3 machine replicates) and 2 biological replicates. c Effect of I. scapularis transcript knockdown on release of infectious LGTV from ISE6 cells transfected with dsRNA for 60 h prior to LGTV infections as assessed by plaque assay and normalized to the pGEM dsRNA negative control. Results represent 5 technical replicates and 2 biological replicates. d Effect of I. scapularis transcript knockdown on release of infectious LGTV from ISE6 cells infected with LGTV and transfected with dsRNA for 60 h. Results represent 2–5 technical replicates and 3 biological replicates. Error bars represent SEM for unpaired t-tests comparing cell viability, negative strand levels or pfu/ml of the negative pGEM control versus each gene of interest. *P ≤ 0.05; **P ≤ 0.01; ***P ≤ 0.001. Abbreviations: FAH, fumarylacetoacetase; ERP29, endoplasmic reticulum protein 29; ALDH, aldehyde dehydrogenase; VNN, carbon-nitrogen hydrolase/vanin-like; MDH2, malate dehydrogenase; PARP, poly [ADP-ribose] polymerase; CMPK, cytidine/urdine monophosphate kinase; ACAT1, acetyl-CoA acetyltransferase; Hypo195 and Hypo576, hypothetical proteins 195 and 576; pGEM, pGEM plasmid negative control (light gray bars); LGTV 3UTR, 3’ UTR of LGTV positive control (dark gray bars); RLU, relative light units

Table 2.

Results of RNAi knockdown of I. scapularis transcripts on LGTV infection in ISE6 cells

| Tick Protein | VectorBase accession ID | Effect of treatment on ISE6 protein expressiona | Effect of transcript knockdown on LGTV negative strand replication | Effect of transcript knockdown on release of infectious LGTV | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LGTVb | UV-LGTVb | ||||

| Fumarylacetoacetase (FAH) | ISCW020196 | Up | Up | No change | Decreased |

| Endoplasmic reticulum protein 29 (ERP29) | ISCW018425 | Up | Up | No change | Decreased |

| Aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH) | ISCW015982 | Up | Up | No change | Decreased |

| Carbon-nitrogen hydrolase/pantetheine hydrolase/vanin-like (VNN) | ISCW004822 | Up | NC | Decreased | Decreased |

| Malate dehydrogenase (MDH2) | ISCW003528 | Up | NC | No change | Decreased |

| Poly [ADP-ribose] polymerase (PARP) | ISCW019519 | Up | NC | No change | No change |

| Cytidine/uridine monophosphate kinase (CMPK) | ISCW012446 | Up | Up | No change | Decreased |

| Acetyl-CoA C-acetyltransferase (ACAT1) | ISCW016117 | Up | Up | Decreased | Decreased |

| Hypothetical protein (Hypo195) | ISCW011195 | Up | NC | No change | Decreased |

| Hypothetical protein (Hypo576) | ISCW020576 | Up | Up | Decreased | Decreased |

aProtein expression following LGTV and/or UV-LGTV treatment of ISE6 cells compared to mock treatment [4]. Up = increased expression and NC = no statistically-significant change in expression

bLGTV = LGTV infection; UV-LGTV = UV inactivated LGTV treatment

Fig. 3.

Proposed cellular location of I. scapularis proteins investigated in the present study. Expression of FAH, ERP29, ALDH, VNN, MDH2, PARP, CMPK, ACAT1, Hypo195 and Hypo576 (light blue) is shown based on studies of orthologous proteins in H. sapiens (excluding Hypo195 and 576). Black circles, ribosomes; dark blue lines, LGTV positive strand; orange lines, LGTV negative strand; red circles, viral proteins associated with replication complexes on the endoplasmic reticulum; purple particles, immature LGTV prior to cleavage of the pr peptide; magenta circles, furin protease produced by the host cell and responsible for cleavage of the pr peptide from the Membrane protein, producing mature LGTV; extracellular purple circles, cleaved pr peptide; extracellular black smooth particles, mature LGTV. Protein localization was based on COMPARTMENTS [33] predictions using data from H. sapiens

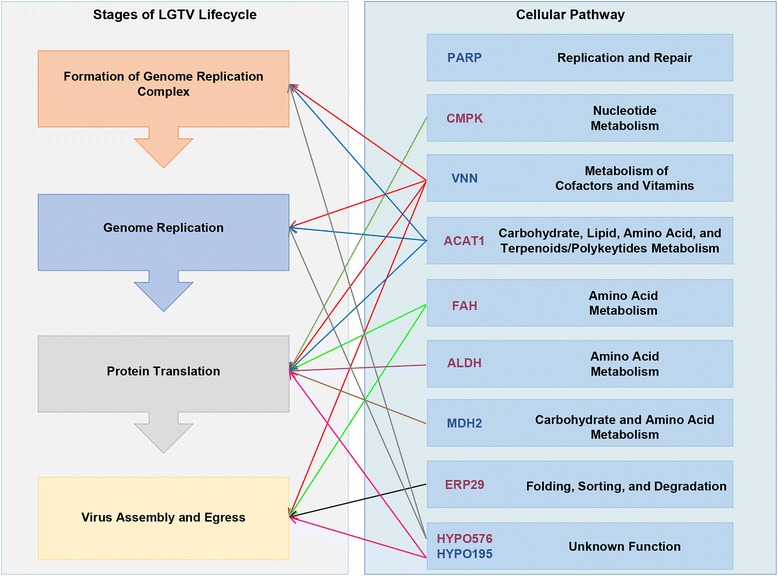

Discussion

We report the first RNAi-based study to evaluate the role of ten I. scapularis proteins (FAH, ERP29, ALDH, VNN, MDH2, PARP, CMPK, ACAT1, Hypo195, and Hypo576) in the LGTV life-cycle. Our results suggest that all ten proteins are involved in one or more aspects of the virus life-cycle in ISE6 cells (Fig. 2). Figure 4 shows the potential role(s) of these proteins in the LGTV life-cycle, predicted based on homology to proteins from H. sapiens and RNAi results. Here we used PCR and the LGTV negative strand template (the LGTV positive strand is copied from the negative strand in replication complexes on the endoplasmic reticulum; Fig. 3) to assess viral genome replication and plaque assays to quantify infectious virus particles released from cells. LGTV infection was reduced in the case of all ten targets when dsRNA was introduced prior to LGTV infection. Introduction of dsRNA following LGTV infection reduced viral titer for all targets except PARP, and this exception could reflect modest RNAi impact on PARP levels. Reduction in transcript levels ranged from 50 to 80% across the ten targets as compared to the control. This range is comparable to those achieved in other RNAi studies using I. scapularis cell lines which report reductions in transcript levels from 9 to 40% [9] and 7–100% [7] in IDE8, and from 5 to 80% in ISE6 cells [26]. Our data suggest that the RNAi effect persists in ISE6 cells for at least 60 h post-transfection, although studies to evaluate impact at the protein level are recognized as a critical next step.

Fig. 4.

Cellular pathways of I. scapularis proteins and possible roles in the LGTV life-cycle inferred from RNAi data. VNN, MDH2, PARP, and Hypo195 exhibited increased expression following LGTV infection only (blue text). FAH, ERP29, ALDH, CMPK, ACAT1, and Hypo576 (magenta text) exhibited increased expression following LGTV infection and/or UV-LGTV treatment [4]. CMPK: orange arrow, VNN: red arrows, ACAT1: blue arrows, FAH: green arrows, ALDH: purple arrow, MDH2: brown arrow, ERP29: black arrow, Hypo576: gray arrows, and Hypo195: pink arrows. Cellular pathways were inferred based on the classification of ISE6 proteins by KEGG PATHWAY analysis and RNAi data (pre-treatment and post-treatment with dsRNA; Fig. 2b-d; Table 2)

Our previous investigations revealed an average replication time for LGTV in ISE6 cells of 12 h with peak release of infectious LGTV at 36 hpi [4]. Here, we pre-treated cells with dsRNA for 60 h (hereafter referred to as “pre-treatment with dsRNA”) and subsequently measured infectious LGTV particles at 16 hpi (Fig. 2c). This time-point was selected in an attempt to capture the first population of infectious virus particles released from cells. For comparative purposes, we also assessed infectious LGTV release from ISE6 cells exposed to LGTV and subsequently transfected with dsRNA for 60 h (post-treatment with dsRNA; Fig. 2d). The latter measurement may reflect several rounds of virus infection and in the case of FAH, ERP29, ALDH, MDH2, PARP, and Hypo576, may explain our observation of higher viral titers in comparison to the results for pre-treated cells.

The proposed cellular location and function of the ten I. scapularis proteins investigated in this study, and the predicted role(s) of these proteins in the LGTV life-cycle is depicted in Figs. 3 and 4. The knockdown of transcripts for VNN, ACAT1, and Hypo576 was associated with a decrease in both LGTV genome replication and release of infectious virus from cells (Fig. 2b-d). Further studies are required to dissect the contributions of these proteins to the LGTV infection process and determine whether the observed reduction in release of LGTV reflects the disruption of processes pre- and/or post-replication of the viral genome. The knockdown of transcripts for FAH, ERP29, ALDH, MDH2, PARP, CMPK, and Hypo195 was associated with a decrease in infectious LGTV only, suggesting that these proteins may be involved in processes independent of viral genome replication (i.e. viral protein synthesis, packaging, egress, and release).

VNN is a glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI)-anchored protein [34] found at the surface of many different vertebrate cells [35] and may also be secreted [33]. GPI proteins perform diverse cellular functions, including lipid remodeling, which occurs during the replication of flaviviruses. KEGG pathway analyses suggest that VNN may function in pantothenate/coenzyme-A (CoA) biosynthesis [36], which is critical for lipid metabolism. This protein family is worthy of further investigation in I. scapularis and other TBF vectors as antiviral targets. ACAT1 may be expressed in the mitochondria and potentially secreted [33]. This enzyme likely utilizes CoA metabolites during metabolism of fatty acids (lipids) and amino acids [37] and may be linked to formation of the lipid-based replication complex in I. scapularis cells through provision of lipids. Small molecules that target enzymes associated with fatty acid and lipid metabolism, such as fatty-acid synthase [10, 11, 13, 38], have been associated with a reduction in mosquito-borne flavivirus infection. However, the possible interaction of ACAT1 with multiple binding partners (Table 1) deserves further investigation as enzymatic promiscuity could impact the potential of this molecule as a target for development of antiviral compounds and transmission blocking vaccines.

ALDH is likely expressed in the mitochondria and cytosol [33] and associated with amino acid metabolism [37] in tick cells. Members of this enzyme class complete the conversion of delta-1-pyrroline-5-carboxylate (P5C) to glutamate, a necessary step linking the urea and tricarboxylic acid cycles with glutaminolysis. In tick cells, the presumably mitochondrial MDH2 [33] may function in pyruvate metabolism [37] and as a rate-limiting enzyme in the citrate cycle. Both ALDH and MDH2 were assigned to the biological processes “ribonucleoprotein/ribosomal/translation/protein metabolic function” (Additional file 1; Table S3) and RNAi data support involvement of these metabolic pathways in viral production in tick cells, possibly via effects on the translation of virus or host RNA. ALDH and MDH2 may represent targets for antivirals and anti-tick vaccines although their potential interaction with multiple binding partners (Table 1) and involvement in multiple cellular processes requires further evaluation. CMPK may be expressed in the cytosol and nucleus [33], and may be involved in nucleotide metabolism in I. scapularis [37]. We speculate that a reduction in this enzyme may reduce nucleotides for DNA/RNA synthesis, and suppress virus production. Suppression of pyrimidine biosynthesis was associated with reduced DENV infection [39] and small molecules that inhibit other enzymes involved in nucleotide biosynthesis reduced arboviruses in cell culture [13, 40, 41]. Inhibition of CMPK may reduce TBF infection but would likely have broad impacts on cellular processes. ALDH, MDH2 and CMPK exhibited increased expression in human hepatoma 7.5 cells (HUH7.5) infected with Hepatitis C virus (HCV) [42] and FAH was decreased in HCV-associated carcinoma tissue [43]. Products that disrupt host proteins involved in enzymatic pathways commonly manipulated by flaviviruses, may provide broad anti-viral effect.

Analyses suggest FAH is a secreted and cytosolic protein that may perform amino acid metabolism [33, 37] in I. scapularis. Disruption of amino acid synthesis could affect the production of virus or host proteins at one or more points in the virus life-cycle. ERP29 is likely associated with the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and also secreted [33]), and may be involved in protein processing and ER associated degradation [37] in the tick. ERP29 showed increased expression in mouse brain tissue following infection with the Japanese Encephalitis virus (JEV) [44]. Studies of polyomavirus-infected cells also suggest a role for ERP29 in viral binding and release from the ER lumen [45–47]. Additional studies are required to investigate the role of ERP in LGTV infection and evaluate the potential of this target.

PARP is likely expressed in the cytosol, mitochondria, and nucleus [33] and may be involved in DNA replication and repair [37] in the tick. This protein has a role in pro-apoptotic signaling and is activated by oxidative stress [48]. The HCV non-structural protein 5A (NS5A) can create oxidative stress, leading to activation of PARP [49]. JEV and DENV also induced cleavage of PARP1, resulting in a variety of pro-apoptotic responses [50]. The increased expression of the ISE6 proteins observed on infection with LGTV may reflect a generalized cellular response or metabolic processes and products used by the virus [4]. Flaviviruses are thought to exploit the cellular stress response to aid replication [51] and oxidative stress is thought to aid the replication of positive-strand RNA viruses [52]. Further, it has been proposed that the balance between antioxidant responses maintains an anti-apoptotic environment during flavivirus infection of the cell [53, 54], presumably facilitating virus replication and transmission.

LGTV concentration has been linked to efficiency of establishment of infection in I. scapularis larvae [27]. In the present study, transcript knockdown produced a modest reduction in LGTV replication and genome replication. It is recognized that a small reduction in amount of infectious virus can profoundly affect transmission; further functional analyses might investigate transcript knockdown over time and it will be necessary to establish that a reduction in protein level or impairment of enzymatic activity in vivo translates to a meaningful reduction in virus transmission. Recapitulation of such studies in the natural vectors of LGTV will also be important as flavivirus replication may differ among natural vector and non-vector cell types [55]. Our predictions regarding cellular compartments associated with protein expression were made based on homology to proteins from H. sapiens and studies are needed to determine the spatio-temporal expression of tick proteins. Transcripts for MDH2 were identified in the salivary glands of blood-fed I. scapularis nymphs [56] and both MDH2 and Hypo195 were identified in the synganglia of I. scapularis [6] suggesting potential roles in neurological processes. Functional studies would be of particular value in the case of Hypo195 and Hypo576. Orthologs of Hypo195 and Hypo576 have not been identified in H. sapiens (Table 1) and these proteins may represent targets for development of vector-specific products to control flavivirus transmission.

Conclusions

Our work provides for investigations of orthologous protein targets in transmission of more virulent TBFs, including POWV and TBEV. Theoretically, small molecules that disrupt one or more tick proteins could be used to limit virus transmission from the tick to mammalian reservoirs and intermediate hosts. Small molecule inhibitors of FAH [57, 58] and PARP [59, 60] are known but their potential to regulate flavivirus infection in arthropods has not been investigated. In addition, there is precedent for development of transmission blocking vaccines against TBFs. The outer surface protein A (OspA) of the Borrelia burgdorferi bacterium is the basis for a Lyme disease (LD) vaccine and has been deployed in the Peromyscus leucopus (white-footed mouse) reservoir [61, 62]. This vaccine, delivered via oral bait, offers one strategy to reduce circulation of B. burgdorferi in the reservoir, and subsequent transmission to the tick vector. Functional studies described here highlight proteins associated with pathogenesis of TBFs and are a necessary precursor to anti-tick vaccine development [63]. Further functional studies will reveal the potential of these proteins as targets for development of new strategies to prevent TBF infections.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Alexander Pletnev (NIH/NIAID, Bethesda, MD) and Timothy J. Kurtti (University of Minnesota) for providing the LGTV TP21 strain and ISE6 cell line, respectively. We thank Esther Schnettler (MRC-University of Glasgow Centre for Virus Research; Roslin Institute and Royal (Dick) School of Veterinary Studies, University of Edinburgh), Sonja M. Best (NIH/NIAID, Hamilton, MT) and Andres F. Sandoval-Mojica (Department of Entomology, Purdue University) for advice on RNAi studies. pGEM plasmid and pGEM primers with T7 promoter were kindly supplied by Michael E. Scharf (Department of Entomology, Purdue University).

Funding

JMG was supported by an NSF Graduate Research Fellowship (Program DGE-1333468) and the Indiana Clinical and Translational Science Institute Pre-doctoral Training Program (NIH/NCATS-ICTSI TL1 TR000162). Research funds provided by the Entomological Society of America, Monsanto Research Grant Award to JMG are gratefully acknowledged. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Availability of data and material

All data are presented in the main paper and Additional file 1.

Authors’ contributions

Conceived and designed the experiments: JMG, MGN, RJK, and CAH. Performed the experiments: JMG. Analyzed the data: JMG, MGN, RJK, and CAH. Contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools: JMG, RJK, and CAH. Wrote the paper: JMG and CAH. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- ACAT1

Acetyl-CoA acetyltransferase

- ALDH

Aldehyde dehydrogenase

- ATCC

American Tissue Culture Collection

- cDNA

Complementary DNA

- CMPK

Cytidine/uridine monophosphate kinase

- DENV

Dengue virus

- dsRNA

Double stranded RNA

- ER

Endoplasmic reticulum

- ERP29

Endoplasmic reticulum protein 29

- FAH

Fumarylacetoacetase

- GO

Gene ontology

- HCV

Hepatitis C virus

- HUH

Human hepatoma cell line

- Hypo195/576

Hypothetical proteins 195/576

- IDE8/ISE6

Ixodes scapularis cell line 8/6

- IFA

Immunofluorescence assay

- JEV

Japanese encephalitis

- KEGG

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes

- LD

Lyme disease

- LGTV

Langat virus

- MDH2

Malate dehydrogenase 2

- MOI

Multiplicity of infection

- Opti

OptiMEM

- PARP

Poly [ADP-ribose] polymerase

- RNAi

RNA interference

- RT-qPCR

reverse transcriptase-quantitative polymerase chain reaction

- SEM

Standard error of the mean

- TBF

Tick-borne flavivirus

- VNN

Carbon nitrogen hydrolase/vanin-like

- Xtr

X-tremeGENE transfection reagent

Additional file

Summary of the process employed to select I. scapularis genes for RNAi knockdown experiments. Δ ISE6 proteins from the differential proteomic analysis at 36 hpi were analyzed. Proteins were selected based on (1) increased expression level, (2) strength of proteomic support (minimum 2 peptides identified from LC-MS-MS per protein) from proteins identified in Grabowski et al. [4], and (3) orthology to vertebrate/invertebrate proteins; * orthologous proteins identified in published proteomic studies [4–6, 8]. LGTV denotes proteins that exhibited increased expression following LGTV infection and LGTV & UV-LGTV denotes proteins that exhibited increased expression following both LGTV infection and UV-LGTV treatment. + proteins that exhibited increased expression following LGTV infection as compared to UV-LGTV treatment. FAH, fumarylacetoacetase; ERP29, endoplasmic reticulum protein 29; ALDH, 1-pyrroline-5-carboxylate dehydrogenase; VNN, pantetheine hydrolase; MDH2, malate dehydrogenase; PARP, poly [ADP-ribose] polymerase; CMPK, UMP-CMP kinase; ACAT1, acetyl-CoA acetyltransferase; Hypo195, hypothetical protein; Hypo576. The prefix “ISCW” denotes VectorBase accession IDs. Figure S2 Effect of pGEM dsRNA concentrations on ISE6 cell viability following transfection for 60 h. X-tremeGENE (Xtr) transfection reagent was used to optimize pGEM dsRNA (RNAi negative control) concentrations in ISE6 cells at 60 h post transfection. Cell viability readings were compared to the Xtr + OptiMEM (Opti) control (gray bar). Red boxes indicate increased or no significant decrease in ISE6 cell viability. RLU560,590, relative light units 560 nm excitation and 590 nm emission. Error bars represent SEM. Statistical analysis was performed using an unpaired t-test between Xtr + Opti control and each pGEM dsRNA concentration. *p value ≤ 0.05 and **p value ≤ 0.01. Results represent 3 technical replicates and 1 biological replicate (multiple biological replicates completed with 10 ng concentration). Figure S3 Effect of transfection with dsRNA on ISE6 cell viability. FAH, fumarylacetoacetase; ERP29, endoplasmic reticulum protein 29; ALDH, 1-pyrroline-5-carboxylate dehydrogenase; VNN, pantetheine hydrolase; MDH2, malate dehydrogenase; PARP, poly [ADP-ribose] polymerase; CMPK, UMP-CMP kinase; ACAT1, acetyl-CoA acetyltransferase; Hypo195, hypothetical protein; Hypo576, hypothetical protein; pGEM, pGEM plasmid (negative control; light gray bars); LGTV 3UTR, 3’ UTR of LGTV TP21 strain (positive control; dark gray bars), RLU560,590, relative light units 560 nm excitation and 590 nm emission. ISE6 cell viability following transfection with 10ng dsRNA for 60 h normalized to the negative control pGEM dsRNA. Results represent 2–5 technical replicates and 3 biological replicates. Error bars represent SEM and unpaired t-tests for comparison of cell viability of the negative pGEM control versus each gene of interest. Table S1 T7-tagged primers used to amplify cDNA and synthesize dsRNA. Table S2 Primers used to amplify cDNA for I. scapularis genes of interest by RT-qPCR. Table S3 Enrichment/cluster analysis of ISE6 proteins that exhibited increased expression following LGTV and UV-LGTV treatment. ISE6 proteins with increased expression following LGTV infection and/or UV-LGTV treatment from [4] were searched via DAVID enrichment analysis. For each cluster, the P value represents a modified Fisher Exact P value, and EASE score implemented in DAVID gene enrichment and functional annotation analysis. Enrichment (E) score of ≥ 1.3 is equal to P value of ≤ 0.05. Table S4 Nucleotide similarity of RT-PCR products amplified from I. scapularis and ISE6 cells and IscaW1 gene models. Table S5 Summary of statistically significant values corresponding to figures. (DOCX 329 kb)

Contributor Information

Jeffrey M. Grabowski, Email: jeffrey.grabowski@nih.gov

Monika Gulia-Nuss, Email: mgulianuss@unr.edu.

Richard J. Kuhn, Email: kuhnr@purdue.edu

Catherine A. Hill, Email: hillca@purdue.edu

References

- 1.Pagel Van Zee J, Geraci NS, Guerrero FD, Wikel SK, Stuart JJ, Nene VM, et al. Tick genomics: the Ixodes genome project and beyond. Int J Parasitol. 2007;37(12):1297–1305. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2007.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hill CA, Wikel SK. The Ixodes scapularis Genome Project: an opportunity for advancing tick research. Trends Parasitol. 2005;21(4):151–153. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2005.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gulia-Nuss M, Nuss AB, Meyer JM, Sonenshine DE, Roe RM, Waterhouse RM, et al. Genomic insights into the Ixodes scapularis tick vector of Lyme disease. Nat Commun. 2016;7:10507. doi: 10.1038/ncomms10507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grabowski JM, Perera R, Roumani AM, Hedrick VE, Inerowicz HD, Hill CA, et al. Changes in the proteome of Langat-infected Ixodes scapularis ISE6 cells: Metabolic pathways associated with flavivirus infection. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2016;10(2):e0004180. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0004180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ayllon N, Villar M, Galindo RC, Kocan KM, Sima R, Lopez JA, et al. Systems biology of tissue-specific response to Anaplasma phagocytophilum reveals differentiated apoptosis in the tick vector Ixodes scapularis. PLoS Genet. 2015;11(3):e1005120. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1005120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oliver JD, Chavez AS, Felsheim RF, Kurtti TJ, Munderloh UG. An Ixodes scapularis cell line with a predominantly neuron-like phenotype. Exp Appl Acarol. 2015;66(3):427–442. doi: 10.1007/s10493-015-9908-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weisheit S, Villar M, Tykalova H, Popara M, Loecherbach J, Watson M, et al. Ixodes scapularis and Ixodes ricinus tick cell lines respond to infection with tick-borne encephalitis virus: transcriptomic and proteomic analysis. Parasit Vectors. 2015;8:599. doi: 10.1186/s13071-015-1210-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ayllon N, Naranjo V, Hajdusek O, Villar M, Galindo RC, Kocan KM, et al. Nuclease tudor-SN is involved in Tick dsRNA-mediated RNA interference and feeding but not in defense against Flaviviral or Anaplasma phagocytophilum Rickettsial Infection. PLoS One. 2015;10(7):e0133038. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0133038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schnettler E, Tykalova H, Watson M, Sharma M, Sterken MG, Obbard DJ, et al. Induction and suppression of tick cell antiviral RNAi responses by tick-borne flaviviruses. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42(14):9436–9446. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Perera R, Riley C, Isaac G, Hopf-Jannasch AS, Moore RJ, Weitz KW, et al. Dengue virus infection perturbs lipid homeostasis in infected mosquito cells. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8(3):e1002584. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Heaton NS, Perera R, Berger KL, Khadka S, Lacount DJ, Kuhn RJ, Randall G. Dengue virus nonstructural protein 3 redistributes fatty acid synthase to sites of viral replication and increases cellular fatty acid synthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107(40):17345–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Heaton NS, Randall G. Dengue virus-induced autophagy regulates lipid metabolism. Cell Host Microbe. 2010;8(5):422–432. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2010.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Krishnan MN, Garcia-Blanco MA. Targeting host factors to treat West Nile and dengue viral infections. Viruses. 2014;6(2):683–708. doi: 10.3390/v6020683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pastorino B, Nougairede A, Wurtz N, Gould E, de Lamballerie X. Role of host cell factors in flavivirus infection: implications for pathogenesis and development of antiviral drugs. Antiviral Res. 2010;87(3):281–294. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2010.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leyssen P, Balzarini J, De Clercq E, Neyts J. The predominant mechanism by which ribavirin exerts its antiviral activity in vitro against flaviviruses and paramyxoviruses is mediated by inhibition of IMP dehydrogenase. J Virol. 2005;79(3):1943–1947. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.3.1943-1947.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chang J, Schul W, Yip A, Xu X, Guo JT, Block TM. Competitive inhibitor of cellular alpha-glucosidases protects mice from lethal dengue virus infection. Antiviral Res. 2011;92(2):369–371. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2011.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Munderloh UG, Kurtti TJ. Formulation of medium for tick cell culture. Exp Appl Acarol. 1989;7(3):219–229. doi: 10.1007/BF01194061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Munderloh UG, Liu Y, Wang M, Chen C, Kurtti TJ. Establishment, maintenance and description of cell lines from the tick Ixodes scapularis. J Parasitol. 1994;80(4):533–543. doi: 10.2307/3283188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pletnev AG, Men R. Attenuation of the Langat tick-borne flavivirus by chimerization with mosquito-borne flavivirus dengue type 4. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95(4):1746–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Campbell MS, Pletnev AG. Infectious cDNA clones of Langat tick-borne flavivirus that differ from their parent in peripheral neurovirulence. Virology. 2000;269(1):225–237. doi: 10.1006/viro.2000.0220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Junjhon J, Lausumpao M, Supasa S, Noisakran S, Songjaeng A, Saraithong P, et al. Differential modulation of prM cleavage, extracellular particle distribution, and virus infectivity by conserved residues at nonfurin consensus positions of the dengue virus pr-M junction. J Virol. 2008;82(21):10776–10791. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01180-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Strober W. Monitoring cell growth. Curr Protoc Immunol. 2001;Appendix 3:Appendix 3A. doi: 10.1002/0471142735.ima03as21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Untergasser A, Cutcutache I, Koressaar T, Ye J, Faircloth BC, Remm M, et al. Primer3 - new capabilities and interfaces. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40(15):e115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Koressaar T, Remm M. Enhancements and modifications of primer design program Primer3. Bioinformatics. 2007;23(10):1289–1291. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ye J, Coulouris G, Zaretskaya I, Cutcutache I, Rozen S, Madden TL. Primer-BLAST: a tool to design target-specific primers for polymerase chain reaction. BMC Bioinformatics. 2012;13:134. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-13-134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Barry G, Alberdi P, Schnettler E, Weisheit S, Kohl A, Fazakerley JK, et al. Gene silencing in tick cell lines using small interfering or long double-stranded RNA. Exp Appl Acarol. 2013;59(3):319–338. doi: 10.1007/s10493-012-9598-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mitzel DN, Wolfinbarger JB, Long RD, Masnick M, Best SM, Bloom ME. Tick-borne flavivirus infection in Ixodes scapularis larvae: development of a novel method for synchronous viral infection of ticks. Virology. 2007;365(2):410–418. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2007.03.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 2001;25(4):402–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Rao X, Huang X, Zhou Z, Lin X. An improvement of the 2^(-delta delta CT) method for quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction data analysis. Biostat Bioinforma Biomath. 2013;3(3):71–85. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Dennis G, Jr, Sherman BT, Hosack DA, Yang J, Gao W, Lane HC, et al. DAVID: Database for Annotation, Visualization, and Integrated Discovery. Genome Biol. 2003;4(5):3. doi: 10.1186/gb-2003-4-5-p3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.von Mering C, Jensen LJ, Snel B, Hooper SD, Krupp M, Foglierini M, et al. STRING: known and predicted protein-protein associations, integrated and transferred across organisms. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33(Database issue):D433–437. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Szklarczyk D, Franceschini A, Wyder S, Forslund K, Heller D, Huerta-Cepas J, et al. STRING v10: protein-protein interaction networks, integrated over the tree of life. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43(Database issue):D447–452. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Binder JX, Pletscher-Frankild S, Tsafou K, Stolte C, O’Donoghue SI, Schneider R, et al. COMPARTMENTS: unification and visualization of protein subcellular localization evidence. Database (Oxford) 2014;2014:bau012. doi: 10.1093/database/bau012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Aurrand-Lions M, Galland F, Bazin H, Zakharyev VM, Imhof BA, Naquet P. Vanin-1, a novel GPI-linked perivascular molecule involved in thymus homing. Immunity. 1996;5(5):391–405. doi: 10.1016/S1074-7613(00)80496-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Boersma YL, Newman J, Adams TE, Cowieson N, Krippner G, Bozaoglu K, et al. The structure of vanin 1: a key enzyme linking metabolic disease and inflammation. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2014;70(Pt 12):3320–3329. doi: 10.1107/S1399004714022767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kinoshita T, Fujita M. Biosynthesis of GPI-anchored proteins: special emphasis on GPI lipid remodeling. J Lipid Res. 2016;57(1):6–24. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R063313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kanehisa M, Sato Y, Kawashima M, Furumichi M, Tanabe M. KEGG as a reference resource for gene and protein annotation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44(D1):D457–462. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv1070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Martin-Acebes MA, Blazquez AB, Jimenez de Oya N, Escribano-Romero E, Saiz JC. West Nile virus replication requires fatty acid synthesis but is independent on phosphatidylinositol-4-phosphate lipids. PLoS One. 2011;6(9):e24970. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0024970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang QY, Bushell S, Qing M, Xu HY, Bonavia A, Nunes S, et al. Inhibition of dengue virus through suppression of host pyrimidine biosynthesis. J Virol. 2011;85(13):6548–6556. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02510-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Morrey JD, Smee DF, Sidwell RW, Tseng C. Identification of active antiviral compounds against a New York isolate of West Nile virus. Antiviral Res. 2002;55(1):107–116. doi: 10.1016/S0166-3542(02)00013-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Qing M, Zou G, Wang QY, Xu HY, Dong H, Yuan Z, et al. Characterization of dengue virus resistance to brequinar in cell culture. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2010;54(9):3686–3695. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00561-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Diamond DL, Syder AJ, Jacobs JM, Sorensen CM, Walters KA, Proll SC, et al. Temporal proteome and lipidome profiles reveal hepatitis C virus-associated reprogramming of hepatocellular metabolism and bioenergetics. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6(1):e1000719. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kim W, Oe Lim S, Kim JS, Ryu YH, Byeon JY, Kim HJ, et al. Comparison of proteome between hepatitis B virus- and hepatitis C virus-associated hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9(15):5493–5500. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sengupta N, Ghosh S, Vasaikar SV, Gomes J, Basu A. Modulation of neuronal proteome profile in response to Japanese encephalitis virus infection. PLoS One. 2014;9(3):e90211. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0090211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Magnuson B, Rainey EK, Benjamin T, Baryshev M, Mkrtchian S, Tsai B. ERp29 triggers a conformational change in polyomavirus to stimulate membrane binding. Mol Cell. 2005;20(2):289–300. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.08.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Walczak CP, Tsai B. A PDI family network acts distinctly and coordinately with ERp29 to facilitate polyomavirus infection. J Virol. 2011;85(5):2386–2396. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01855-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Inoue T, Tsai B. How viruses use the endoplasmic reticulum for entry, replication, and assembly. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2013;5(1):a013250. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a013250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mao Z, Hine C, Tian X, Van Meter M, Au M, Vaidya A, et al. SIRT6 promotes DNA repair under stress by activating PARP1. Science. 2011;332(6036):1443–1446. doi: 10.1126/science.1202723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Paracha UZ, Fatima K, Alqahtani M, Chaudhary A, Abuzenadah A, Damanhouri G, et al. Oxidative stress and hepatitis C virus. Virol J. 2013;10:251. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-10-251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lee CJ, Liao CL, Lin YL. Flavivirus activates phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase signaling to block caspase-dependent apoptotic cell death at the early stage of virus infection. J Virol. 2005;79(13):8388–8399. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.13.8388-8399.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Blazquez AB, Escribano-Romero E, Merino-Ramos T, Saiz JC, Martin-Acebes MA. Stress responses in flavivirus-infected cells: activation of unfolded protein response and autophagy. Front Microbiol. 2014;5:266. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2014.00266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gullberg RC, Jordan Steel J, Moon SL, Soltani E, Geiss BJ. Oxidative stress influences positive strand RNA virus genome synthesis and capping. Virology. 2015;475:219–229. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2014.10.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chen TH, Lo YP, Yang CF, Chen WJ. Additive protection by antioxidant and apoptosis-inhibiting effects on mosquito cells with dengue 2 virus infection. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2012;6(4):e1613. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chen TH, Tang P, Yang CF, Kao LH, Lo YP, Chuang CK, et al. Antioxidant defense is one of the mechanisms by which mosquito cells survive dengue 2 viral infection. Virology. 2011;410(2):410–417. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2010.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ruzek D, Bell-Sakyi L, Kopecky J, Grubhoffer L. Growth of tick-borne encephalitis virus (European subtype) in cell lines from vector and non-vector ticks. Virus Res. 2008;137(1):142–146. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2008.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.McNally KL, Mitzel DN, Anderson JM, Ribeiro JM, Valenzuela JG, Myers TG, et al. Differential salivary gland transcript expression profile in Ixodes scapularis nymphs upon feeding or flavivirus infection. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2012;3(1):18–26. doi: 10.1016/j.ttbdis.2011.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bateman RL, Bhanumoorthy P, Witte JF, McClard RW, Grompe M, Timm DE. Mechanistic inferences from the crystal structure of fumarylacetoacetate hydrolase with a bound phosphorus-based inhibitor. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(18):15284–15291. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M007621200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bateman RL, Ashworth J, Witte JF, Baker LJ, Bhanumoorthy P, Timm DE, et al. Slow-onset inhibition of fumarylacetoacetate hydrolase by phosphinate mimics of the tetrahedral intermediate: kinetics, crystal structure and pharmacokinetics. Biochem J. 2007;402(2):251–260. doi: 10.1042/BJ20060961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tempera I, Deng Z, Atanasiu C, Chen CJ, D’Erme M, Lieberman PM. Regulation of Epstein-Barr virus OriP replication by poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase 1. J Virol. 2010;84(10):4988–4997. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02333-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gibson BA, Kraus WL. New insights into the molecular and cellular functions of poly(ADP-ribose) and PARPs. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2012;13(7):411–424. doi: 10.1038/nrm3376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bhattacharya D, Bensaci M, Luker KE, Luker G, Wisdom S, Telford SR, et al. Development of a baited oral vaccine for use in reservoir-targeted strategies against Lyme disease. Vaccine. 2011;29(44):7818–7825. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.07.100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Richer LM, Brisson D, Melo R, Ostfeld RS, Zeidner N, Gomes-Solecki M. Reservoir targeted vaccine against Borrelia burgdorferi: a new strategy to prevent Lyme disease transmission. J Infect Dis. 2014;209(12):1972–1980. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiu005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.de la Fuente J, Merino O. Vaccinomics, the new road to tick vaccines. Vaccine. 2013;31(50):5923–5929. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.10.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]