Abstract

Ecological momentary assessment (EMA) is a novel data collection method that samples subject experiences in real‐time – minimizing recall bias. Here, we describe the feasibility of EMA to track breastfeeding behaviour through a mobile phone app. During their birth hospitalization, we approached healthy, first‐time mothers intending to exclusively breastfeed for at least 2 months to participate in a study tracking breastfeeding through 8 weeks postpartum. Participants downloaded a commercially available smartphone app, entered information and thoughts about breastfeeding as they occurred, and emailed this data weekly. We called participants at 2 and 8 weeks to assess breastfeeding status. At the 8‐week call, we also assessed participants' experiences using the app. Of the 61 participants, 38% sent complete or nearly complete feeding data, 24% sent some data, and 38% sent no data; 58% completed at least one free‐text breastfeeding entry, and five women logged daily or near daily entries. Compared with women who sent no data, those who sent any were more likely to be married, highly educated, intend to breastfeed more than 6 months, have a more favourable baseline attitude towards breastfeeding, and less likely to have used formula during hospitalization. There was a high degree of agreement between participant‐reported proportion of breast milk feeds via app and interview data at 2 weeks (ICC 0.97). Experiences with the app ranged from helpful to too time‐consuming or anxiety‐provoking. Participants and researchers encountered technical issues related to app use and analysis, respectively. While our data do not support the feasibility of stand‐alone app‐based EMA to track breastfeeding behaviour, it may provide rich accounts of the breastfeeding experience for certain subgroups of women. © 2016 John Wiley & Sons Ltd

Keywords: breastfeeding, ecological momentary assessment, mobile applications, maternal recall, feeding behaviour, infant, newborn

Introduction

While the majority of researchers and clinicians rely upon retrospective interview or self‐report data to obtain information on maternal breastfeeding practices, these data are highly amenable to recall bias. Indeed, accurate maternal recall of breastfeeding behaviour positively correlates with shorter total recall period and seminal rather than nuanced events (e.g. infant age at complete weaning from breastfeeding more accurately recalled than age at first introduction of formula or solid foods), with a tendency for mothers to overestimate the duration of exclusive breastfeeding (Li et al. 2005; Cupul‐Uicab et al. 2009; Agampodi et al. 2011; Barbosa et al. 2012; Burnham et al. 2014). Gillespie et al. (2006) found that accuracy of recalled reasons for breastfeeding cessation varied 1–3.5 years after birth, with mastitis and return to work having greater recall validity than nipple trauma. Recall bias may be particularly salient in the study of breastfeeding behaviour for the following reasons: (1) infant feeding is an emotionally imbued, often divisive subject; women may restructure their breastfeeding experience (consciously or subconsciously) to align with personal, familial, and societal expectations (Li et al. 2005; Barbosa et al. 2012); (2) physical and emotional fatigue during the postpartum period can contribute to memory lapses regarding feeding details (Swain et al. 1997); and (3) the breastfeeding relationship rapidly evolves, particularly in the first weeks postpartum as the infant matures, milk supply regulates, and other physiological and psychological changes occur; current breastfeeding status and mood can bias recollection of past breastfeeding practices and experiences (e.g. consistency bias) (Schacter 2001). To maximize the validity of reported breastfeeding data, The World Health Organization recommends that infant feeding practices be assessed via 24‐h maternal recall (‘previous day’) (World Health Organization 2008). The World Health Organization recommendation, however, does not take into account feeding and formula supplementation since birth, and as such, does not provide an accurate indication of duration of exclusive breastfeeding.

Ecological momentary assessment (EMA) may be one option to reduce recall bias inherent in the study of maternal breastfeeding behaviour. EMA is a novel data collection method that samples subject experiences – thoughts, behaviours, and symptoms, close to or concurrent with when they actually take place. It permits a nuanced measurement of – or real‐time intervention in – human behaviours in the contexts in which they occur (Shiffman et al. 2008). EMA has been applied to the study of wide‐ranging behaviours and responses, including pain, stress, physical activity, diet, and substance use. EMA data have been collected via diverse platforms, including written and electronic diaries, body sensors, phone calls, SMS (text messages), and increasingly, mobile phone applications (‘apps’) (Runyan et al. 2013).

Characterization of breastfeeding behaviour as it occurs, as EMA offers, affords the potential to uncover micro‐processes and antecedents associated with breastfeeding outcomes, track breastfeeding progress, and administer and assess the efficacy of breastfeeding interventions in a time‐sensitive manner. For the first time in the current study, we assess the feasibility of EMA via a widely available technology – a mobile phone app, as an alternate method to track early breastfeeding behaviour.

Key messages.

App‐based EMA was a highly reliable method for tracking proportion of breast milk feeds at 2 weeks postpartum.

Most participants completing study‐end interviews gave positive reviews of their experiences using the app to track breastfeeding.

Most participants used the app to enter at least some breastfeeding data, but only 38% sent complete feeding data over 8 weeks.

Participants logged single lines to detailed paragraphs in the app regarding their breastfeeding experience.

App‐based EMA may be useful as a supplementary data collection method among women of higher socioeconomic statuses and/or those highly committed and supported to breastfeed past 6 months.

Methods

Study design and purpose

The purpose of this prospective, observational study was to describe the feasibility and acceptability of EMA to capture real‐time breastfeeding practices of first‐time mothers in the first 2 months postpartum. This study was approved by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board.

Participants and recruitment

Between October 2014 and September 2015, we approached primiparous women during their postpartum birth hospitalization to take part in a study tracking breastfeeding through 8 weeks postpartum via a mobile phone app. The participants were at least 18 years, owned a smartphone, intended to breastfeed exclusively for at least 2 months, had no contraindications to breastfeeding, had no conditions expected to directly impact at breastfeeding or milk supply, and delivered a singleton infant within the past 4 days with no known health anomalies expected to impact at‐breast feeds.

We approached women during their postpartum hospitalization at a large regional obstetrical hospital. Those signing informed consent and meeting eligibility criteria were enrolled into the study. Because this was a pilot study designed to generate basic descriptive and feasibility data, no power calculation was performed. Instead, we aimed to enrol a convenience sample of roughly 50–60 women.

Procedures

At enrolment, we collected background demographic, social, medical, and breastfeeding data via medical record review and maternal self‐report. We also administered the 17‐item Iowa Infant Feeding Attitude Scale to assess breastfeeding attitude (higher score indicating more favourable attitude towards breastfeeding) (De La Mora et al. 1999) and a combined eight‐item anxiety and stress scale (Perceived Stress Scale and PROMIS Emotional Distress–Anxiety Scale; higher score indicating more stress/anxiety).

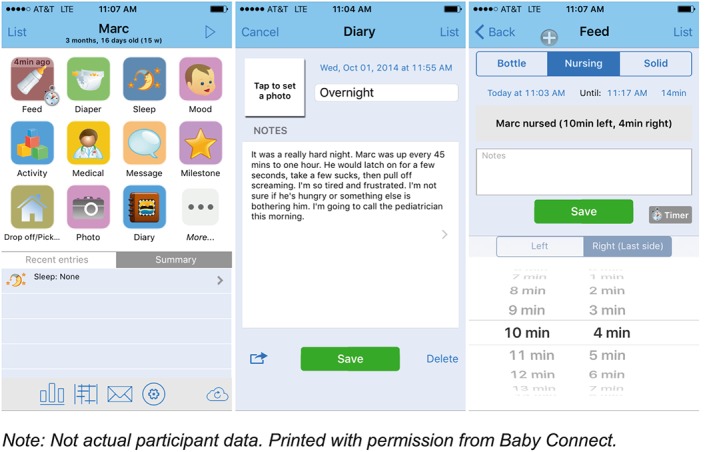

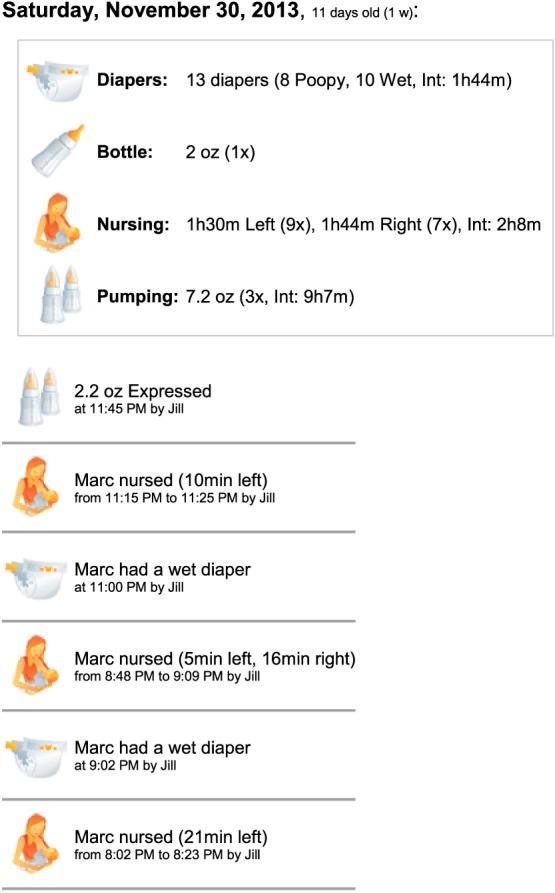

Also at enrolment, we showed the women how to download and use the commercial infant‐feeding mobile app (Baby Connect), compatible with both iPhone and Android phones. After a review of available infant‐feeding apps by the study team, this particular app was selected based on the detail and breadth of infant‐feeding information that could be inputted, as well as the ease with which data could be shared with researchers. The participants were instructed to immediately begin entering data into the app related to infant feeding and milk expression as it occurred (e.g. time, duration, volume, notes). The participants were also encouraged to use the app's diary feature daily, or at least once per week, to comment on how breastfeeding was progressing (e.g. problems, successes, unexpected events). Although not required for the study, the women could also use other features in the app to track infant sleep, stool/urine output, moods, physician appointments, and infant anthropometric data, vaccines, and milestones. We asked the women to send the app data daily or weekly via an email app feature (HTML format) through 8 weeks postpartum (Figs 1,2).

Figure 1.

Screenshots of Baby Connect app home screen, diary, and feeding entry screen.

Figure 2.

Example excerpt of emailed app data (not actual participant data). The box provides a 24‐h summary of urine and stool output, as well as volumes, total time, and average interval times for feeding and pumping.

We called all women at 2 and 8 weeks postpartum to assess breastfeeding status, as well as to confirm and seek elaboration on any breastfeeding problems noted in the app data. At 8 weeks, we also assessed the women's experiences using the app using an open‐ended question (‘Tell me about using the app’) and probes (‘Any difficulties inputting information?’, ‘Did you use the app, or refer back to it, for purposes other than the study?’, ‘Did you input information as it happened or at a later time? If the latter, did you find it difficult to recall data?’). The women were compensated for the cost of the app ($4.99), completion of baseline measures, interviews at 2 and 8 weeks, and app data every 2 weeks (pro‐rated for incomplete or partial data). Total study compensation was up to $110.

All weekly app data, questionnaire, and interview data were entered into and managed in REDCap electronic data capture tools hosted at the University of Pittsburgh (Harris et al. 2009). Telephone calls at 8 weeks were not audio‐recorded, but participant responses were entered directly into REDCap at the time of the interview using language as close as possible to the participants' actual words.

Analysis

We analysed qualitative 8‐week interview data for major themes. First author JD coded and condensed participant responses into general categories of positive, negative, and neutral feedback with subcategories/descriptors (e.g. helpful, annoying) and exemplars. Second author DB reviewed and approved the coding and final presentation of the data.

All quantitative data were analysed with SPSS v. 23 (IBM Corporation, 2015). We calculated summary statistics to describe the sample and proportion of women sending app data. Differences in categorical‐level characteristics between the women sending and not sending app data were assessed using Pearson chi‐square tests (global test of proportions) and binary logistic regression with unadjusted odd ratios and associated 95% confidence intervals to determine directionality of differences within variable categories. Between‐group differences in continuous variables were assessed via t‐tests for equality of means.

To assess the reliability of EMA for collection of breastfeeding data, we calculated intraclass correlation coefficients (two‐way mixed model) comparing the absolute agreement between interview‐ and app‐reported proportion of total breast milk feeds at 2 weeks. At the 2‐week interview, the participants were asked to estimate this proportion during the last 24 h. For the app data, we calculated the proportion of breast milk feeds from the total number of documented feeds for the day prior to the 2‐week interview. Only the participants who had complete feeding data documented in the app were included in the analysis (operationalized by researcher consensus as at least six documented feedings in 24 h and gaps of no more than 5 h between documented feedings during daytime hours). A paired‐sample t‐test was used to determine if the mean proportion of breast milk feeds differed significantly between the app and interview data. We did not assess the reliability of the 8‐week interview and app data because of gaps exceeding 24 h between the last sent app data and the interview in the majority of participants.

Results

Recruitment feasibility

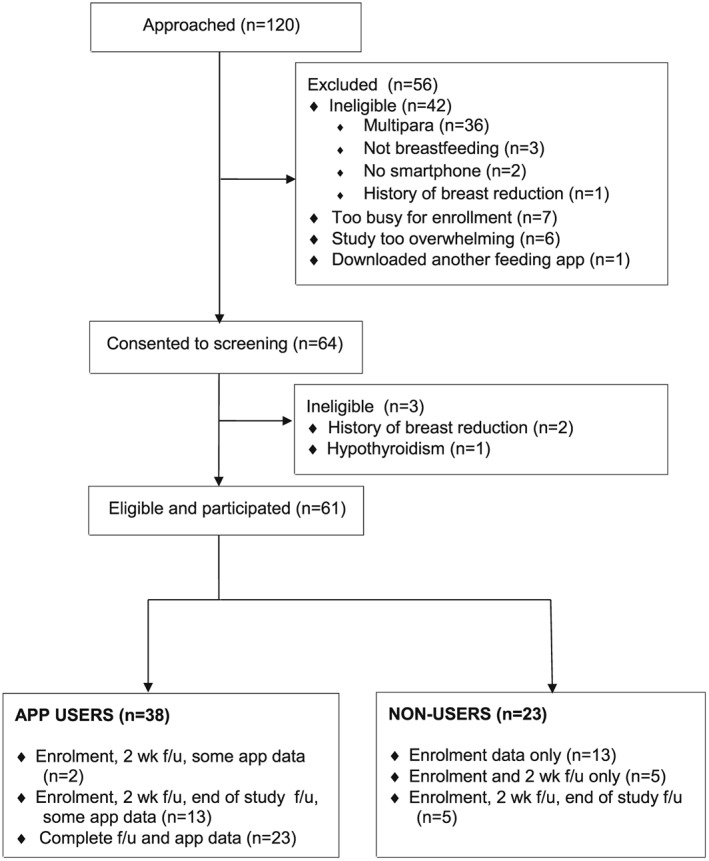

Among 120 women approached, 51% (n = 61) were eligible and participated in the study. Reasons for ineligibility and non‐participation are summarized in Fig. 3.

Figure 3.

Study flow diagram.

Sample characteristics

The majority of participants were non‐Hispanic White, married, held at least a Bachelor's degree, and intended to exclusively breastfeed for at least 6 months. The mean age of the sample was 27 years (range: 18–35 years). During the study enrolment hospitalization, 98% breastfed at‐breast at least once. The weekly incidence of formula use during the study period ranged from 42% of the participants (Weeks two and four) to 46% (Weeks one and eight). Of those who completed a final interview (n = 41), 22% had stopped breastfeeding.

The majority of study infants were born at term (≥39 gestational weeks), with a range of 362/7–416/7 weeks. Infant birthweight ranged from 2596–4645 g. No infants were admitted to the neonatal intensive care unit during their birth hospitalization (Table 1).

Table 1.

Proportions and means (with standard deviations) for continuous and categorical characteristics (respectively) of women who sent and did not send app data, with unadjusted odd ratios for sending any data (categorical variables only)

| App use | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Overall | Sent no app data | Sent any app data | uOR (95% CI) for any data | P‐value |

| N (%) | 61 (100) | 23 (38) | 38 (62) | ||

| Married | 67 | 44 | 82 | 5.8 (1.8–18.4) | <0.01 |

| Education | 0.03 | ||||

| High school diploma | 16 | 30 | 8 | 1.0 | |

| Some college or vocational program | 23 | 26 | 21 | 3.1 (0.6–17.3) | 0.20 |

| Bachelor's degree | 33 | 26 | 37 | 5.4 (1.0–28.5) | 0.05 |

| Post‐graduate degree | 28 | 17 | 34 | 7.6 (1.3–43.9) | 0.02 |

| Maternal age (y) * | 27 (4.4) | 26 (5.0) | 28 (3.9) | N/A | 0.06 |

| Hispanic ethnicity | 3 | 0 | 5 | N/A | N/A |

| Race | 0.15 | ||||

| White/Caucasian | 74 | 65 | 79 | 1.0 | |

| Black/African American | 15 | 26 | 8 | 0.3 (0.1–1.1) | 0.07 |

| Other | 12 | 9 | 13 | 1.3 (0.2–7.2) | 0.80 |

| WIC recipient | 28 | 39 | 21 | 0.4 (0.1–1.3) | 0.13 |

| Planned return to work ** | 0.02 | ||||

| No return or uncertain | 20 | 26 | 16 | 1.0 | |

| 5–8 weeks | 21 | 35 | 13 | 0.6 (0.1–3.1) | 0.56 |

| 9–12 weeks | 44 | 22 | 58 | 4.4 (1.0–19.5) | 0.05 |

| 13 weeks–1 year | 15 | 17 | 13 | 1.3 (0.2–7.1) | 0.80 |

| Planned duration of any bf | 0.01 | ||||

| Unsure | 12 | 26 | 3 | 1.0 | |

| ≤6 months | 30 | 35 | 26 | 7.5 (0.7–75.7) | 0.09 |

| >6 months | 59 | 39 | 71 | 18 (1.9–170.3) | 0.01 |

| Planned duration of exclusive bf | 0.18 | ||||

| Unsure | 23 | 36 | 16 | 1.0 | |

| <6 months | 13 | 9 | 16 | 4.0 (0.6–27.2) | 0.16 |

| ≥6 months | 63 | 55 | 68 | 2.9 (0.8–10.1) | 0.10 |

| Formula use in hospital | 38 | 56 | 26 | 0.3 (0.1–0.8) | 0.02 |

| Formula use at 2‐week interview (n = 48) | 38 | 20 | 42 | 2.9 (0.5–15.6) | 0.21 |

| First bf ≤1= h after delivery | 49 | 39 | 55 | 1.9 (0.7–5.5) | 0.22 |

| IIFAS score (baseline) * | 64.9 (6.3) | 62.5 (6.1) | 66.4 (6.1) | N/A | 0.02 |

| Combined EDA/PSS score (baseline) * | 11.0 (4.9) | 10.8 (4.3) | 11.1 (5.3) | N/A | 0.84 |

| Weeks of gestation at birth * | 39.4 (1.4) | 39.3 (1.5) | 39.5 (1.3) | N/A | 0.53 |

| Infant birthweight (g) * | 3389 (449) | 3356 (414) | 3409 (473) | N/A | 0.66 |

| Male infant | 64 | 57 | 68 | 1.7 (0.6–4.9) | 0.35 |

bf, breastfeeding.

Combined EDA/PSS, combined PROMIS Emotional Distress–Anxiety Scale and Perceived Stress Scale (possible score range 0–32; higher score indicative of higher stress/anxiety).

IIFAS, Iowa Infant Feeding Attitude Scale (possible score range 17–85; higher score indicative of more favorable attitude towards breastfeeding).

Represents continuous variables, where group means, rather than proportions, are reported; P‐value representing results of t‐test for equality of means.

No participants planned to return to work prior to 5 weeks postpartum.

Feasibility: use of the app

Of the 61 participants, 23 (38%) sent complete or nearly complete data (no more than 2 days of incomplete feeding data per week) for 8 weeks or until breastfeeding cessation. Fifteen (24%) sent some data, and 23 (38%) sent no data. The women who were married, had a post‐graduate degree, planned to breastfeed longer than 6 months, and had a more favourable attitude towards breastfeeding at baseline (via 17‐item Iowa Infant Feeding Attitude Scale) were more likely to send app data (P < 0.05). The women who used formula during the postpartum hospitalization were less likely to send app data (P < 0.05). Compared with the women who did not plan to return to work or were unsure about postpartum work plans, the women who intended to return to work at 9–12 weeks were marginally more likely to send app data (P = 0.05). Compared with the women with a high school diploma, the women with a Bachelor's degree were also marginally more likely to send app data (P = 0.05) (Table 1).

Thirty‐four participants (58%) completed at least one free‐text entry regarding breastfeeding during the study period. Most used the diary feature in the app to do this (or as a ‘note’ attached to a single breastfeeding session), while two participants sent breastfeeding updates directly via email. Five women logged daily or near daily free‐text breastfeeding entries.

Content and length of the free‐text entries varied. The women logged anywhere from a single line of text per entry to paragraphs. Content included (1) physical breastfeeding problems: description, current management, plans and contingencies, maternal feelings/effect on life and mood, and reactions and advice from healthcare providers and family; (2) summarization, evaluative, and classification statements regarding breastfeeding experience; (3) personal meaning and emotional investment in breastfeeding; (4) breastfeeding status and activity details (e.g. positioning at‐breast, length, frequency, volume of feeds); (5) interpretation of infant's behaviour at breast and satisfaction with breastfeeding; and (6) cultural and system barriers (Table 2). When the participants used the diary function to enter notes, the app required them to enter a title. The participants generally chose short titles of one to five words, summarizing problems, concerns, triumphs, and milestones (e.g. ‘sore nipples’, ‘hungry!’, ‘first day home’, ‘good day’, ‘getting somewhere’).

Table 2.

Excerpts from app diary entries related to breastfeeding – demonstrating data depth and range

| Content area | Participant examples |

|---|---|

| Physical problems | •‘Nipple pain: We've had what I feel is a serious setback, personally. I have been trying to feed [son] with the best latch I can, but in the last 24 hr some nipple problems have arisen. Last night I had a long feeding session, after which my nipple was very compressed and radiated pain. He must have stayed on too long?…I couldn't get an appt today since it's New Year's Eve, but I was able to speak to a lactation consultant on the phone. She advised to get a deeper latch whenever possible and to watch closely for his swallows‐‐once he stops eating, take him off the nipple so he's not nibbling. I am very discouraged by this nipple damage…Am I doing permanent damage? How is this ever going to heal if I keep feeding constantly? It feels like never‐ending problems sometimes.’ |

| •‘Emptiness revisited: My breasts still regularly feel empty near the end of the day, and combined with the end‐of‐the‐day pain, it makes me concerned [son] is not getting enough to eat before bed. …we have continued with a supplement [of expressed breast milk] at the end of the day. We'll discuss at our one‐month checkup if this is still necessary and then adjust our approach accordingly.’ | |

| •‘Leaking milk: Breastfeeding is going well, and I'm happy for that but my milk is coming in and I'm leaking everywhere. It's frustrating that even with shells and pads I'm still having to change shirts and sometimes pants multiple times a day because of the leaking. I'm hoping everything regulates that this will go away. If I continue having problems I think I'll call the lactation consultant back and see what she recommends.’ | |

| Summarization, evaluation, and classification | •‘Breastfeeding is going very well‐no problems.’ |

| •‘Groove: We have been in a groove the last few days and it feels great. Feeding is now pain free…’ | |

| •‘Thoughts: Today was better than yesterday for the most part. Good feedings and sleep during the day. Cluster feeding in the evening and night (very exhausting and rough)’ | |

| •‘[Son] is doing really well with breastfeeding. I started pumping after morning feed so that my husband can do one of the nighttime feedings. Overall, I expected this to be harder than it is for us.’ | |

| •‘Another hard day: [son] isn't himself. He is spitting up more now [after breastfeeding] than he was even the other day…This is not what I thought his first three weeks of life would be like. I feel so bad.’ | |

| Personal meaning/emotional investment | •‘I'm looking forward to [the lactation consultant's] advice because breastfeeding is something I love doing for [my daughter]’ |

| •‘Compliment: Some of our friends came over and I was nursing at the time. I put my cover on and went out in front of them. I wasn't sure beforehand how I would feel about it, but it was really no big deal. They didn't seem to be uncomfortable and I really didn't care even if they were. One of them texted me later and [said] she was so impressed with how much of a pro I looked like doing that. I thought that was super sweet and made me feel good!…’ | |

| •‘A little sad: The doctor told me yesterday to start introducing a bottle [of expressed breast milk] to [my son]. It's not to stop breastfeeding or giving him my milk, but that it was time to get him used to the idea [of a bottle]. I don't know exactly why, but it made me a little sad.’ | |

| •‘…[Cluster feeding] is a long cycle. It can be frustrating but I know it's important to keep on going! I want what is best for my little boy, that's what keeps me going!’ | |

| Breastfeeding status/activities | •‘MILK CAME IN!’ |

| •‘Right breast started to leak when nursing left [breast] so switched sides. Wasn't sure what to do’ | |

| •‘Not much swallowing’ | |

| •‘Had to pump 5 min on left side bc I was sore & he wouldn't wake up enough to eat.’ | |

| •‘Was being fussy and I offered a bottle before breast’ | |

| •‘Supplement‐only pumped two oz of breast milk! He usually needs 3 oz to fill him up.’ | |

| •‘We did try breastfeeding 1 more time, he did latch on and suckled. He didn't latch on properly. I stopped him and switched to the bottle. He wouldn't even latch on to the left breast. Breastfeeding just wasn't meant to be this time.’ | |

| Interpretation of infant's breastfeeding behaviour | •‘Breast feeding is going good. Yes, he looks satisfied. I can hear him swallow every time he breast feeds. He enjoys breastfeeding.’ |

| •‘Know when he is done: …I am still trying to figure [out when to feed son]. I also am having trouble figuring out when he is done. Sometimes I think he is but then he screams so we go back to the breast and he is happy.’ | |

| •‘Fed a lot more than usual today. Growth spurt? I'm exhausted.’ | |

| •‘I feel like [breastfeeding] keeps getting harder and harder. But I keep trying and I feel like [son] likes formula better than breast. He gets so mad when I put him on my breast, he likes the bottle nipple better.’ | |

| •‘[Son] was very fussy & gassy tonight. Wonder what I ate that bothered him?!?!’ | |

| Cultural and system barriers | •‘Milk in: Milk came in yesterday and [infant] has been feeding well. I didn't realize how big/firm it would make my breasts and was worried at first about engorgement…Wish that's something I had known about to better prepare for…had to run to Target today to buy sleep nursing bras. No mother wants to make a trip to Target with a 5 day old at home. Feel like I could have been better prepared for this.’ |

| •‘Nursing: So I had to nurse in a restaurant bathroom last night. I actually stood in one of their stalls. How is it that its 2015 and that was my only option. I feel like society is a total hypocrite. They say how great nursing is and everything and I agree, but nobody supports us. People look at you like you are a three headed monster. It really disappoints me.’ |

Note: Some entries are edited for length.

Feasibility: technical issues

We experienced several technical issues that potentially impacted participant compliance using the app, data accuracy, and scalability. For example, some participants were unable to download the app at enrolment because of an unreliable internet connection at the hospital and/or out‐of‐date or no credit card information stored in their mobile app purchasing software. Although we provided written and oral instructions regarding download and home use of the app, at least five women never downloaded it. Also, because the app was not breastfeeding‐specific, it offered no default option for feeding expressed breast milk (could be manually added as a drop‐down list item) and few breastfeeding customization options (e.g. feeding expressed breast milk via devices other than bottles). In end‐of‐study interviews, some participants mistakenly reported that the app did not permit retrospective data entry for the previous day, which was perceived as a design flaw.

From a staffing and scalability perspective, it took considerable time and resources to manually enter and compile large quantities of daily feeding data. Although the app offered the possibility to automate this process by sending data in comma separated value format, it still required a researcher to separate probable participant entry errors from accurate data (e.g. overlapping feeding periods, large gaps between feeding times).

Reliability of app data

Twenty‐four women had both 2‐week interview data and complete app data for the day prior to the interview and were included in the reliability analysis. We found a high degree of agreement between the 2‐week interview and app data for reported proportion of breast milk feeds (ICC 0.97; 95% CI 0.93–0.99). The mean proportion of breast milk feeds reported at 2 weeks via interview was 82.7% (SD 30.6) and 85.3% (SD 27.8) via the app. This difference was not statistically significant (t (23) = −1.27; P = 0.22).

Acceptability: participant feedback via interviews

Of the 41 participants completing end‐of‐study interviews, 34 gave positive reviews of the app overall or individual app features (‘liked it’, ‘helpful’, ‘easy to use’). These women used the app as a tool to observe trends in infant behaviour (e.g. sleeping, feedings) for daily planning purposes and reporting back to the paediatrician at well‐child visits. The app also served as a reminder of when to breastfeed and on which breast the infant last fed. The participants reported using the summary features of the app, including graphs that displayed counts, duration, volume and time intervals of sleep, diapers, feedings, and pumping. Notably, one participant found that reviewing the app's breastfeeding summaries validated her time‐ and emotional‐investment in the ‘work of breastfeeding’. The participants also described adding other caregivers as users (e.g. father of the baby), so that these individuals could also log and monitor the infant's daily activities. Some participants used other app features, including infant photo uploads and inputting infant behavioural milestones (e.g. smiling), moods (e.g. fussy, sleepy), activities (e.g. tummy time), and data from paediatric well‐visits (e.g. anthropometrics and vaccines).

The participants also provided equivocal or negative feedback on the app. For example, some thought logging daily data was time‐consuming or annoying at times (n = 9), anxiety‐provoking (n = 2), difficult to remember (n = 7), or carried out only for the researchers' benefit with no personal value (n = 2). Some of the latter participants preferred to track infant behaviours, including breastfeeding, via hand‐written notes and later entered these data into the app. Some participants initially found the app helpful but then burdensome or unnecessary after becoming accustomed to their infant's daily sleeping, feeding, and output patterns (n = 3). One mother logged her opinion of the app at 8 weeks using the diary feature:

Being a new mom, I just want to do everything right and I am realizing that I need to be more confident in myself. [My son] is a happy baby and if he wasn't getting what he needed, I would see signs. I am not sure if looking back at how long he fed on different days [on the app] is what made me question whether he was eating enough. I like keeping track of the diapers and times that he feeds, but focusing so much on time, rather than if it just appears that [he] is satisfied after feeding [made me anxious].

Discussion

Despite technical issues and some participant dissatisfaction, the majority of first‐time mothers entered at least some breastfeeding data and enjoyed tracking their breastfeeding progress in a mobile app over the first 8 weeks postpartum. When compared with 24‐h recall, we also found app‐based EMA to be a highly reliable method for tracking proportion of breast milk feeds among the participants with complete app data. However, given the equal numbers of participants providing no data and complete data, our study does not support the feasibility of stand‐alone, app‐based EMA to provide comprehensive accounts of breastfeeding behaviours and thought processes for a general population of first‐time mothers. It may be useful as a supplementary data collection method among women of higher socioeconomic statuses and/or those highly committed and supported to breastfeed past 6 months. Consistent with our findings, Pew research data indicate individuals who use apps are likely to be more highly educated and affluent compared with the general population who use cell phones (Purcell et al. 2010). There is a lack of comparable data examining demographic differences from other studies using apps to track and modify health behaviours.

Many participants found the app content personally relevant and beneficial, likely increasing compliance. Apps are a widely used and familiar technology, increasingly interwoven into daily life. In 2014, an estimated 50% of American cell phone users downloaded mobile apps (Pew Research Center 2014), with apps constituting 86% of the total time individuals spent using mobile devices per day (Khalaf 2013). We selected the app used in the study for its intuitive functionality and the ease with which breastfeeding data could be shared between research and participant. It is unclear how other apps or more traditional EMA methods (e.g. random telephone calls) compare in terms of garnering the most comprehensive breastfeeding data. We also used an asynchronous participant compensation schedule in our study, and it is possible that this impacted participant motivation to enter feeding data consistently.

The detail, length, and personal nature of many of the free‐text diary entries we received were unanticipated. Although there are many rich accounts of the breastfeeding experience from interview data and even audio diaries (Williamson et al. 2012), there are little data on electronic breastfeeding diaries. Our study demonstrates that among a subset of women, app‐based breastfeeding diaries are one potentially high‐yield source of qualitative breastfeeding data with comparatively lower costs than traditional data collection methods (e.g. focus groups, in‐person interviews).

The data gleaned from this study are being used to develop a text message‐based breastfeeding support program, with content based on breastfeeding practices and problems experienced by participants at specific postpartum time points, incorporating the language and descriptions they used. Yet, these and similar data have other potential research, clinical, and commercial implications. For example, future app design or data retrieval could be automated such that clinicians or mothers receive alerts when feeding frequency or signs of inadequate nutrition (e.g. insufficient number of urine diapers) fall below an established acceptable threshold. With shareable app‐based EMA, researchers and clinicians may be able to automate collection of more accurate breastfeeding histories and/or deliver real‐time intervention options (e.g. just in time adaptive interventions). As technology continues at its current pace, other modalities of tracking breastfeeding may prove even more valuable – including, for example, wearable bio‐monitoring devices.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine the feasibility of continuous tracking of breastfeeding via mobile devices. Confidence in findings is strengthened by the relatively long period for which we tracked compliance and a large pilot study sample. Conversely, a major limitation of the study was our relatively homogeneous sample of White, educated, healthy women and infants, from a single hospital system, most of whom intended to breastfeed exclusively for 6 months. The results cannot be generalized to minority populations and women who intend to non‐exclusively breastfeed or breastfeed for a short time. Another limitation was assuring accuracy of inputted data: (1) In some cases, it was difficult to distinguish between missing data vs. infrequent feedings; (2) there was no way to ensure that mothers themselves were recording the data vs. others caring for the infant and using the same mobile device; and (3) the app permitted backlogging data, and some mothers did state that they retrospectively entered data. The latter at least partially negates the benefit of EMA.

To account for user error and missing data, we recommend future studies tracking continuous breastfeeding data via apps combine several confirmatory data collection methods (e.g. brief telephone interviews or electronic surveys), and when possible, the option for mothers to select the most important data from lists in addition to the opportunity to free text. Considering the participant burden of long‐term, continuous data entry in such studies, even if personally beneficial, researchers should explore options for over‐enrolment, generous participant compensation, and automated immediate feedback (e.g. payment, thank you and reminder emails). Researchers would also do well to create or select EMA methods that maximize user‐centred design, minimize sources of potential bias (e.g. insufficient space to account for frequent breastfeeding), and avoid undermining maternal breastfeeding efforts (e.g. apps with formula advertisements).

Sources of funding

This study was funded by a K99/R00 NIH Pathway to Independence Award (NINR 1K99NR015106; PI: Demirci).

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Contributions

JD oversaw data collection, lead data analysis and compilation of results, and drafted the manuscript. DB provided input in study design, data collection and analysis decisions, critically reviewed the drafts of the manuscript, and approved the final version.

Acknowledgments

We thank Baby Connect for their permission to use the app in this research study. We also thank Kathleen Daniluk for her assistance with data collection and Briana Deer and Anastasia Alberty for their assistance with data entry and reliability.

Demirci, J. R. , and Bogen, D. L. (2017) Feasibility and acceptability of a mobile app in an ecological momentary assessment of early breastfeeding. Maternal & Child Nutrition, 13: e12342. doi: 10.1111/mcn.12342.

References

- Agampodi S.B., Fernando S., Dharmaratne S.D. & Agampodi T.C. (2011) Duration of exclusive breastfeeding; validity of retrospective assessment at nine months of age. BMC Pediatrics 11, 1471–2431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbosa R.W., Oliveira A.E., Zandonade E. & Neto E.T.S. (2012) Mothers' memory about breastfeeding and sucking habits in the first months of life for their children. Revista Paulista de Pediatria 30, 180–186. [Google Scholar]

- Burnham L., Buczek M., Braun N., Feldman‐Winter L., Chen N. & Merewood A. (2014) Determining length of breastfeeding exclusivity: validity of maternal report 2 years after birth. Journal of Human Lactation 30, 190–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cupul‐Uicab L.A., Gladen B.C., Hernandez‐Avila M. & Longnecker M.P. (2009) Reliability of reported breastfeeding duration among reproductive‐aged women from Mexico. Maternal & Child Nutrition 5, 125–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De La Mora A., Russell D.W., Dungy C.I., Losch M. & Dusdieker L. (1999) The Iowa Infant Feeding Attitude Scale: analysis of reliability and validity. Journal of Applied Social Psychology 29, 2362–2380. [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie B., D'arcy H., Schwartz K., Bobo J.K. & Foxman B. (2006) Recall of age of weaning and other breastfeeding variables. International Breastfeeding Journal 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris P.A., Taylor R., Thielke R., Payne J., Gonzalez N. & Conde J.G. (2009) Research electronic data capture (REDCap) — a metadata‐driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. Journal of Biomedical Informatics 42, 377–381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khalaf S. 2013. Flurry five‐year report: It's an app world. The web just lives in it. Flurry Insights [Online]. Available: http://flurrymobile.tumblr.com/post/115188952445/flurry-five-year-report-its-an-app-world-the [Accessed February 12, 2016].

- Li R., Scanlon K.S. & Serdula M.K. (2005) The validity and reliability of maternal recall of breastfeeding practice. Nutrition Reviews 63, 103–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pew Research Center . 2014. Mobile technology fact sheet. Available: http://www.pewinternet.org/fact-sheets/mobile-technology-fact-sheet/ [Accessed February 12, 2016].

- Purcell K., Entner R. & Henderson, N. (2010) Pew Research Center: the rise of apps culture. Available: http://www.pewinternet.org/2010/09/14/the-rise-of-apps-culture/ [Accessed May 3, 2016].

- Runyan J.D., Steenbergh T.A., Bainbridge C., Daugherty D.A., Oke L. & Fry B.N. (2013) A smartphone ecological momentary assessment/intervention “app” for collecting real‐time data and promoting self‐awareness. PLoS One 8, e71325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schacter D.L. (2001) The sin of bias In: The Seven Sins of Memory: How the Mind Forgets and Remembers (ed. Schacter D.L.). New York, NY: Houghton Mifflin Company. [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S., Stone A.A. & Hufford M.R. (2008) Ecological momentary assessment. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology 4, 1–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swain A.M., O'hara M.W., Starr K.R. & Gorman L.L. (1997) A prospective study of sleep, mood, and cognitive function in postpartum and nonpostpartum women. Obstetrics and Gynecology 90, 381–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williamson I., Leeming D., Lyttle S. & Johnson S. (2012) ‘It should be the most natural thing in the world’: exploring first‐time mothers' breastfeeding difficulties in the UK using audio‐diaries and interviews. Maternal & Child Nutrition 8, 434–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . 2008. Indicators for assessing infant and young child feeding practices: conclusions of a consensus meeting held 6–8 November 2007 in Washington D.C., USA. Available: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/43895/1/9789241596664_eng.pdf [Accessed February 12, 2016].