Abstract

The US pays about twice as much per capita for health care than any other developed country, yet its health metrics rank among the lowest among peer nations – for example, the US has 12.2 maternal mortality deaths per 100,000 compared to 4.8 in Canada which, like other developed nations, has a single payer health care program. The leading cause of bankruptcies in the US is attributable to medical expenses. Despite recently introduced legislation (the Affordable Care Act) many millions of Americans remain uninsured or underinsured. We shall consider views on the pathogenesis of such a dysfunctional health care system and make suggestions for how it can be improved. We shall also emphasize the importance of an integrated system of universal health care for population-based epidemiological research and preventive medicine, including its implications for the enhancement of the healthspans and lifespans of future generations via trans-generational inheritance. Finally, we suggest that the anticipated major health care savings of such a system, if partially invested in basic and translational research, should accelerate progress towards further gains in healthspans and lifespans.

Keywords: Single payer health care, Universal health care, Medical economics, Medical ethics, Medical research, Epidemiology, Socioeconomic disparities, Gerontology, Geroscience, Healthspan

1. Introduction

We must first ask why a publically funded single payer system of universal health care is of special relevance to medical ethics as it impacts our geriatric patients. Answers to that question are motivated by an extrapolation of a favorite admonition by the late Robert Butler, the founding director of the National Institute on Aging and a Pulitzer Prize author (Butler, 1975). His response to skeptics concerning the need to support research on aging was to remind them that our elderly grandparents are “our future selves”. Given the growing evidence from research on epigenetic inheritance (Bohacek and Mansuy, 2015), the substrate for healthy aging can potentially begin at least as far back as grandparental generations and most certainly are functions of the quality of pre-natal and pediatric care. How well one builds an organism makes a great deal of difference in how long it lives and how well it functions. Given these views, geroscientists should not only be advocating for more research and healthcare in geriatrics; they should extend their efforts to embrace such disciplines as developmental biology and pediatrics, particularly as regards preventive medicine. The quality, universality and cost-effectiveness of a nation’s healthcare system are therefore of central importance to our collective goals to enhance both healthspans and lifespans of our populations, particularly the enhancements of Healthspan/Lifespan ratios. We shall review evidence that, despite the effort of the recent Affordable Care Act, the system of health care in the US continues to fail to meet the needs of many millions of its residents, unlike other peer developed nations. Moreover, the per capita costs of our complex, dysfunctional system are about twice that of any other peer nation http://www.pgpf.org/chart-archive/0006_health-care-oecd.

As a pathologist, the author will frame the discussion in terms of the “pathogenesis” of this national “disease”. We shall therefore consider six major relevant issues: 1) the hypothesis that the balance between two broad ethical views on health care (Actuarial Fairness vs. Community Solidarity) (Stone, 1993) is shifted towards the former among Americans; 2) the failure of the United States to recognize healthcare as a human right; 3) the “love affair” of Americans with the magical power of the “Free Market Economy”; 4) the American paranoia of the influence of government; 5) the extraordinary recent growth of the monetary and political power of special corporate interests in American politics; 6) the growing socioeconomic disparities within our American society. As a physician scientist, I am also interested in a “cure” for this “disease” and shall argue that we need a multifactorial approach, certainly including the development of a single payer (i.e., single bargaining agent), publically funded system of universal health care. Legislation already exists in the form of HS 676, a bill introduced in the US House of Representatives by the Honorable John Conyers (https://www.congress.gov/bill/114th-congress/house-bill/676/cosponsors.

2. Evidence for a dysfunctional US healthcare system

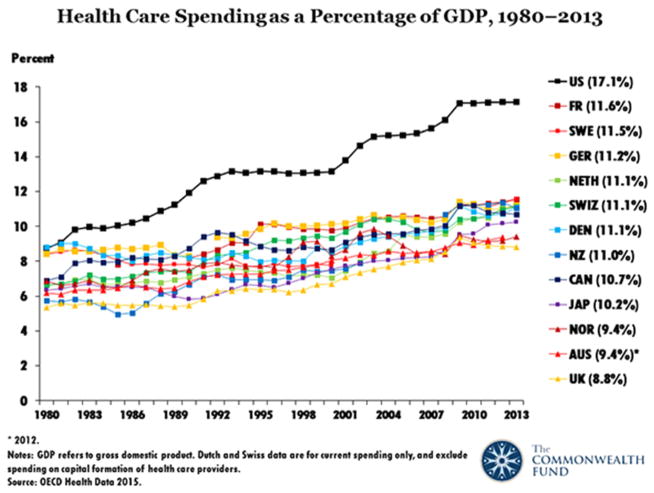

Let us first consider the per capita costs for health care here in the US as compared to the costs of the US health care system up to the implementation of the Affordable Care Act. As shown in Fig. 1 (see http://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/issue-briefs/2015/oct/us-health-care-from-a-global-perspective), the rapid rate of growth of health care spending in the US, expressed as the percentage of the gross domestic product (GDP) is compared to 12 other high income peer nations. In 2013, our spending was at the level of ~17% of GDP compared to a mean of about 10% for the case of the cluster of these 12 peer nations. Given the slope of the US curve and absent any effective amelioration of these trends, an extrapolation into the mid-21st century could result in costs of ~25% of the GDP. Given the demographic trends of an aging society (Halaweish and Alam, 2015) and the anticipated increased costs associated with the care of the elderly, the costs of medical care could easily approach ~30% of GDP, clearly an unsustainable burden on the economy and upon those who cannot afford the high premiums and co-payments of the currently structured US system of private health insurance. Evidence that the current system is dysfunctional comes from studies of the causes of bankruptcies in the United States. In 2007, Dr. David Himmelstein and colleagues published the first-ever national random survey of bankruptcies in the United States (Himmelstein et al., 2009). Remarkably, they found that 62.1% of all bankruptcies were due to failure to pay medical bills. Moreover, there was evidence that within the six year period between 2001 and 2007, that proportion had risen by approximately 50%. Also of considerable interest were their observations that some ¾ of these medical debtors actually had some form of health insurance and were typically middle class, well-educated individuals. The contrast with what is observed in European countries with some form of a single payer universal health care system is stark: 65.2% to essentially 0%, as I cannot find any credible reports of such bankruptcies.

Fig. 1.

The rate of increase in health care expenditures in the United States, expressed as percentages of GDP (Gross Domestic Product) greatly surpasses those of 17 other developed countries. Figure is reproduced with the permission of David Squires of the Commonwealth Fund.

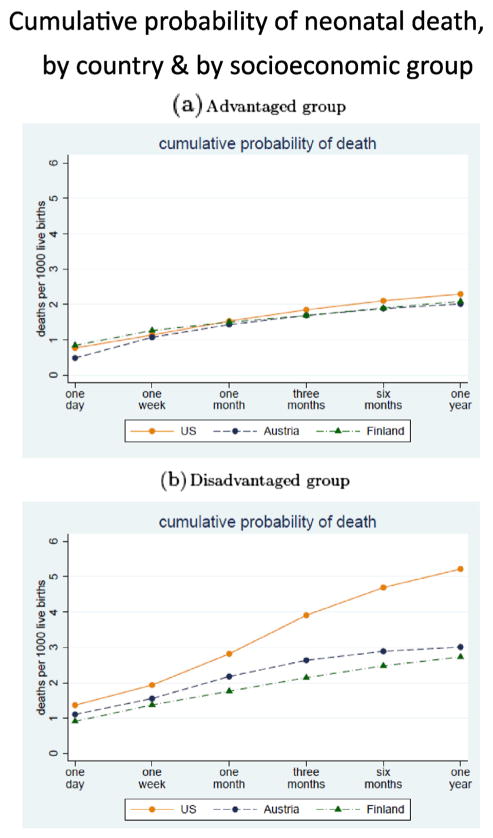

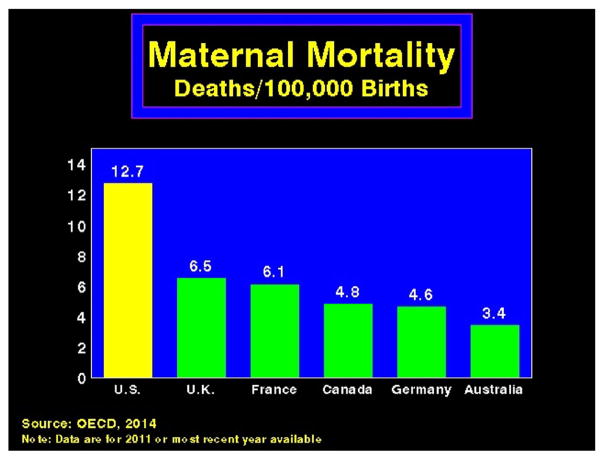

Now let us see what all this money has done for our health here in America. Alas, for most health metrics, we rank far below our peer nations, including our rates of infant mortality and maternal mortality. These comparative data depend upon the gestational ages of mortality. For all neonatal deaths, however, a study of 2010 data ranked the US last among 26 mostly European Nations (MacDorman et al., 2014). A recent more nuanced study clearly demonstrates, however, that the major variable underlying this statistic is the socioeconomic status of the mother (Fig. 2) (Chen et al., 2014). The US also ranks last among peer nations in the category of maternal mortality (see Fig. 3 for a sub-set of this data). One would predict that, as in the case of infant mortality, socioeconomic status may also be a major contributor to the poor US performance.

Fig. 2.

The cumulative probabilities of neonatal deaths in the US, Austria and Finland: While these probabilities over the ages from 1 day to one year are roughly comparable for subsets of families with comparatively high socioeconomic status (the advantaged groups), mortalities for infants in the US become increasingly greater from ages one day to one year for subsets of families with comparatively low socioeconomic status (the disadvantaged groups). For details of this study, see Chen et al. (2014). The figure is reproduced with permission of the Economic Policy Institute and the American Economic Association (NBER working paper #20525 2014).

Fig. 3.

The rates of maternal mortalities in the US are substantially higher than those of a subset of five other developed countries. The data, derived from the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), are reproduced by permission of David U. Himmelstein, MD, and Steffie Woolhandler, MD, MPH, Professors of Public Health at the City University of New York at Hunter College and co-founders of Physicians for a National Health Program.

In an impressive analysis of a gerontologically relevant, but often neglected parameter – Healthy Life Expectancy (defined as “the number of years that a person at a given age can expect to live in good health, taking into account mortality and disability”), Professor Chris Murray and his colleagues found that, from among the 34 member OECD nations, the US ranked 26, just below Slovenia (Murray et al., 2013). A more nuanced set of data than that shown in these metrics would likely have demonstrated that the burden of these unacceptable results is carried by lower socioeconomic groups (Ezzati et al., 2008), certainly including many African-Americans (Rossen and Schoendorf, 2014).

The superior results of treatments for some forms of cancer in the US are interesting exceptions to the above generalizations. These achievements are associated with much higher costs than what is the case for other peer nations, however. Consider, for example, the monoclonal antibody (blinatumomab) which, when initially approved for the treatment of acute lymphoblastic leukemia by the US Food and Drug Administration, was priced at $178,000 per year (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Blinatumomab).

Are the high costs worth it? A group of distinguished health epidemiologists answered this question in the affirmative, particularly for the case of prostate and breast cancers. The authors used an established metric for the calculation of the monetary value of the additional years of life (Philipson et al., 2012), but were careful to point out several caveats in the interpretation of their results. One such caveat strikes me as being particularly relevant, namely that there were no evaluations of the impacts of the degree of continued morbidity and associated parameters of quality of life during the purchase of those few extra years of survival. The United Kingdom, whose population has supported a single payer system of universal health care for many years, has addressed this ethical dilemma of determining the relative cost effectiveness of expensive new therapies by creating a National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (usually referred to as NICE; https://www.nice.org.uk/). For some patients whose hopes of gaining access to expensive new treatments that provide some increase in survival from cancer, they regard that solution as “not so nice”!

3. Six likely pathogenic mechanisms responsible for the dysfunctional US health care system

3.1. The ratio of the ethics of community solidarity/the ethics of actuarial fairness is proportionately lower in the US compared to those of other developed countries

In 1993, Deborah A. Stone published a seminal paper describing two contrasting ethical principles that underlie the views of Americans regarding the support of healthcare in their communities (Stone, 1993). She referred to one as the ethic of actuarial fairness, which she described as an “antiredistributive ideology”. In laymen’s terminology, Americans often ask: “why should my taxes or insurance premiums subsidize health insurance for guys who smoke and gorge on junk food?” She noted that trade associations of the health and life insurance Industry had developed advertisements designed to persuade the public that “paying for someone else’s risks” is a bad idea. Given the power of such advertisements, one can understand why such views appear to be widespread here in America. Professor Stone described the alternative ethic as “community solidarity” by which, via social insurance paradigms, “individuals are entitled to receive whatever care they need, and the amounts they pay to finance the scheme are totally unrelated to the amount or cost of care they actually use.” One can imagine an individual who embraces such an ethic being concerned not only for the welfare of the unfortunate chap who does not pursue good health practices, but also for his children, realizing that a healthy community leads to a healthy society and, moreover, that providing preventive medical services to all residents of a community is cost effective. Professor Stone’s hypothesis that the ratio of the Ethic of Community Solidarity/the Ethic of Actuarial Fairness is lower in the US as compared to other developed countries is consistent with a number of findings in a complex quantitative review comparing social welfare policies in the US with those of European countries, all of which contribute a greater share of their GDP to social welfare programs (Alesina et al., 2001). These authors demonstrated growing disparities in governmental expenditures between the US and the European Union dating from 1870. In 1998, governmental expenditures on subsidies and transfers, expressed as percentages of GDP, were ~22% in Europe and ~12% in the US. The authors summarized the likely causes of this discrepancy. Readers interested in these issues are encouraged to examine the thoughtful commentaries embedded at the end of this paper and to also consider an interesting and more recent paper with somewhat different conclusions, although accompanied by a concern that the approach that they had taken “has many shortcomings” (Collado and Iturbe-Ormaetxe, 2010). It is clear that we need more research on this subject.

3.2. The failure of the US to recognize health care as a human right

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights was adopted by the UN General Assembly in 1948 (see Article 25 regarding health care as a human right, http://www.un.org/en/universal-declaration-human-rights/). These concepts were elaborated upon in 1966 with the adoption by the UN General Assembly of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (see Article 12, (http://www.ohchr.org/EN/ProfessionalInterest/Pages/CESCR.aspx. The US Senate failed to ratify this declaration, however, unlike other member states.

3.3. The free market economy

Private, for-profit insurance companies dominate the US health care system. They are likely to do so for the indefinite future, given its role under the Affordable Care Act, which includes public subsidization for its management of Medicaid enrollees (http://www.hhs.gov/healthcare/about-the-law/read-the-law/index.html). While free market economics can work for a wide variety of industries, shopping for the best buy (re the quality and expense of care) when one is seriously ill would obviously be very difficult, if not impossible. Moreover, if the health care facility is outside of the network covered by your medical insurance company, you may not be covered. Even when covered, you may have substantial co-payments, particularly if you have chosen a low-premium option of insurance. As the NY Times as recently pointed out, “even experts were wrong about the best places for better and cheaper health care” (http://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2015/12/15/upshot/the-best-places-for-better-cheaper-health-care-arent-what-experts-thought.html). What is now becoming clearer are the enormous geographical variations in costs and the absence of a correlation between costs for Medicare (a federal health insurance program for people who are 65 or older, certain younger people with disabilities, and people with End-Stage Renal Disease) and those for private insurance, which are typically much higher (http://www.healthcarepricingproject.org/).

3.4. The American paranoia of government

“The nine most terrifying words in the English language are I’m from the government and I’m here to help.” (http://www.quotationspage.com/quotes/Ronald_Reagan/21). Given the widespread popularity of President Reagan, he may well have reflected the views of many of his fellow Americans. The Pew Foundation has gathered polling data on the subject of mistrust of government between 1958 and 2014, demonstrating striking trends of increasing distrust (http://www.people-press.org/2014/11/13/public-trust-in-government/). The most recent survey, conducted in February of 2014, revealed that only 24% of respondents replied that they trusted their federal government “always or most of the time”. A more thorough examination of this subject is given in a recent publication by two political scientists (Hacker and Pierson, 2016).

3.5. The excessive influences of money and special interests upon the political process

It is no secret that there has been a rising tide of major political contributions in the US from a small number of wealthy elites, particularly since the Supreme Court decision on Citizens United (Citizens United vs. Federal Election Commission, No. 08-205 558 U.S. 310, 2010). A 2015 study by Ian Vandewalker of the Brennan Center for Justice at New York University School of Law concluded that outside spending on Senate elections more than doubled since 2010, increasing to $486 million in 2014 (http://www.brennancenter.org/sites/default/files/analysis/Outside%20Spending%20Since%20Citizens%20United.pd). Moreover, the author points out that this is an underestimate, as certain types of advertisements are not required to be reported. Considering the most competitive Senate races of 2014 and the ten highest spending funds (“Super PACS”), less than 1% of the money came from small donors contributing less than $200 in eight of these ten. Given the importance of campaign advertisements, the power of the mass media and the influence of paid political lobbyists, it should come as no surprise that such funds get results. But is there credible research that supports that contention? The answer is yes. For example, an influential 2014 publication by two political scientists, Martin Gilens and Benjamin I. Page, concluded that “our analyses suggest that majorities of the American public actually have little influence over the policies our government adopts” (Gilens and Page, 2014). In another example, Patrick Flavin of Baylor University asked “Do states with stricter lobbying regulations actually display more egalitarian patterns of political representation?” His answer is yes (Flavin, 2015).

An example of the power of special corporate interests to influence the global economy is given by the secretly negotiated Trans-Pacific Pact. Dr. Margaret Flowers is one of a number of colleagues who are concerned, for example, with the potential negative influences of such legislation upon the health and environment and rising prices of pharmaceuticals (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Co6b9R3DU_E).

3.6. The growing socioeconomic disparities of Americans

The GINI coefficient (named after Corrado Gini, an Italian statistician and sociologist) is a widely used measure of income inequality. Data from the late 2000s that considers income after taxes and transfers rank the US as the third most unequal among the 34 OECD countries (behind Mexico and Turkey) (https://en.Wikipedia.Org/wiki/List_of_countries_by_income_equality).

The importance of this issue for human health is highlighted by a current search of the PubMed database using the search terms of “socioeconomic status and health”, which yielded 67,655 references. An example that reinforces earlier comments concerning the importance of early developmental influences upon health outcomes is a recent study that demonstrated that children born to socioeconomically disadvantaged parents were more likely to exhibit neurological abnormalities when examined at various times of development (4 months, one year and seven years) (Chin-Lun Hung et al., 2015). While complications of pregnancy and delivery are also more prevalent among lower socioeconomic groups, they could not explain these neurological findings. It will obviously be of great importance to discover the underlying mechanisms and potential reversibility of these abnormalities, which can impact different neurological domains, including the autonomic nervous system. Moreover, given the recent interest in transgenerational epigenetic inheritance, it is not inconceivable that at least a subset of these neurological deficiencies can be passed on to one or a few subsequent generations; for two recent relevant reviews, see Yuan et al. (2015) and Skinner (2015). Socioeconomic factors are of course major contributors to chronic late life disorders, certainly including type 2 diabetes mellitus, where death rates from the disease are greater in lower socioeconomic groups, in part because of later diagnoses (Casagrande et al., 2014) A recent large study of a Scottish cohort failed to find evidence that co-morbidities explained the severity of the disease among the lower socioeconomic groups (Walker et al., 2015). The authors point to literature implicating such socioeconomic variables as material deprivation, childhood social development, social exclusion, occupational status and security, educational attainment, and housing environment and tenure upon health and mortality as potential explanations. They do not comment, however, on the recent evidence of transgenerational epigenetic inheritance of obesity via male spermatozoa; for a partial review, see (Soubry, 2015). Other cogent examples of evidence consistent with potentials for transgenerational inheritance involve exposures of the fetus of a pregnant woman who smokes cigarettes (Joubert et al., 2016) and fetal exposure to lead (Sen et al., 2015). Exposure to cigarette smoke is of particular relevance to gerontology, as it has been characterized as a “gerontogen” (Bernhard et al., 2007; Martin, 1987; Sorrentino et al., 2014).

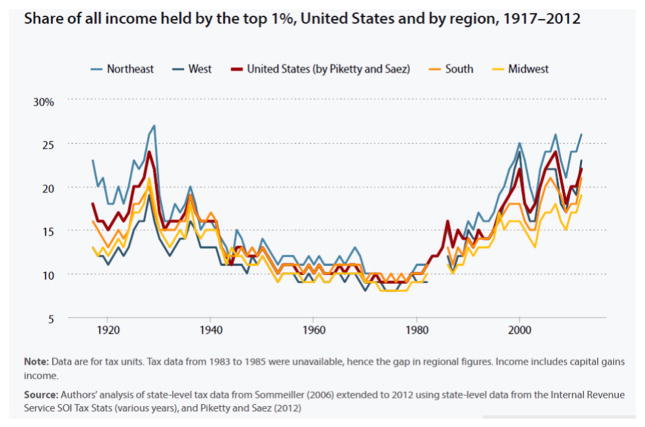

Given the above, those responsible for the health of our population should consider the recent patterns of ever-increasing economic disparities in the US (Fig. 4) (http://www.epi.org/publication/income-inequality-by-state-1917-to-2012/).

Fig. 4.

Evidence of recent increasing levels of income disparities in the US. The figure is reproduced from (http://www.epi.org/publication/income-inequality-by-state-1917-to-2012/ with permission from the Economic Policy Institute.

4. Seven therapeutic interventions

4.1. Educate our population regarding the value of a democratic society unfettered by the monetary power of special interests

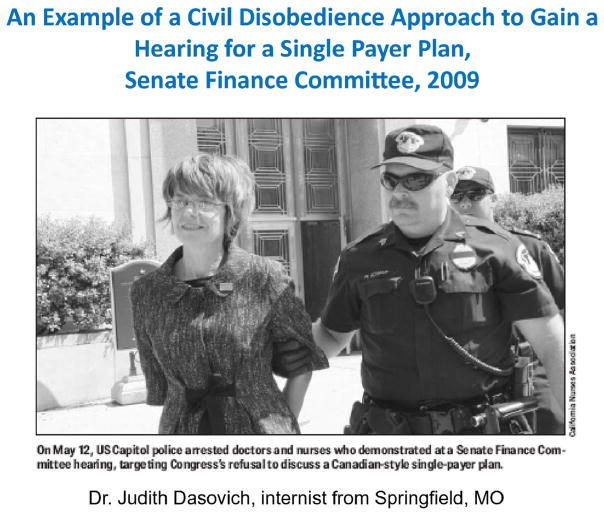

It is not surprising that, given the trillions of dollars of expenditures on health care in the US, for-profit private insurance companies have lobbied against a single payer, publically funded system of universal health care. It was not even politically feasible for representatives of Physicians for a National Health Program (PNHP) to obtain permission to discuss their views on a single payer system from the then Chair of the Senate Finance Committee, which was charged with the responsibility of evaluating proposals for the reform of our health care system prior to the passage of the Affordable Care Act. Several members of PNHP concluded that the only remaining option for getting their views to the American public was via civil disobedience (Fig. 5). For a first person account of this story, readers should go to the following link: http://pnhp.org/blog/2009/05/08/why-we-risked-arrest-for-single-payer-health-care/. To the best of my knowledge, this story was not reported by any major television networks or newspapers. This is perhaps not surprising, given the extensive direct to consumer advertising of pharmaceutical products on television in our country. Such advertising has been illegal in European countries with some form of single payer universal health care, but there have been recent efforts to pass legislation to allow “high quality information” on mass media (http://pnhp.org/blog/2010/12/05/ask-your-doctor/). One can also understand opposition of pharmaceutical companies to single payer systems, as those of us in the US pay substantially more for our drugs because of the absence of a single bargaining agent (see Chart 4 in http://www.oecd.org/unitedstates/49084355.pdf). The Veterans Administration, a single payer system, is an exception. Those supporting the efforts of the pharmaceutical companies to raise drug prices in these European countries (including some members of the US Congress) have argued that consumers in these European countries have gotten a “free ride” because of the expenses of US companies for research and development; see references in Light and Lexchin (2005). Those claims have been amply refuted, however (Light and Lexchin, 2005); these authors concluded that: “The idea that the US is subsidizing other rich countries contradicts basic economics and the global nature of pharmaceutical markets”.

Fig. 5.

An example of health care professionals (physicians and nurses) who, following their failure to obtain permission to present the case of a single payer system of universal health care at the 2009 hearings of the US Senate Finance Committee on options of health care reform, made the decision to participate in civil disobedience actions. The figure is reproduced by permission of Dr. Judith Dasovich, Professor Leonard Rodberg (http://archive.psc-cuny.org/Clarion/ClarionSummer09.pdf) and the California Nursing Association (http://www.nationalnursesunited.org/site/entry/california-nurses-association).

4.2. Reversal of the increasing socioeconomic disparities in our society via a series of affirmative actions

In keeping with a major gerontological theme of this review, educational efforts to prepare our citizens for productive, long and healthy lives should start in very early childhood. I have been very impressed with oral and written presentations on this subject by Bruce Alberts, the former President of the National Academy of Sciences and former Editor-in-Chief of Science magazine. Consider, for example, the following quotation from his editorial for Science (Alberts, 2011): “Especially informative are the long-term studies on the effects of early childhood interventions, which indicate that an appropriate schooling of children as young as 3 years old produces remarkably large benefits for society, even in cases where the children do not perform significantly better academically.” Imagine if we could encourage teachers and parents to instill into their precious charges, regardless of their socioeconomic status, the ability to ask the question “How do we know that’s true?” What a marvelous preparation for future voters! Recent interest in publically funded pre-school education in some communities is a good beginning http://nieer.org/publications/why-cities-are-making-preschool-education-available-all-children.

Progressive public educational initiatives will have difficulty making an impact when children are hungry, in poor health, deprived of parental support and in unsafe neighborhoods. A wide range of additional programs must therefore be maintained or initiated. This will require governmental actions on tax reforms and educational programs aimed at decreasing the ratio of the ethics of Actuarial Fairness/Community Solidarity.

4.3. Enhancement of primary care and preventive medicine

While the number of primary care physicians is projected to increase from 205,000 FTEs (full time equivalents) in 2010 to 220,800 in 2020 (an 8% increase), the demand for primary care physicians is projected to grow by 28,700 – from 212,500 FTEs in 2010 to 241,200 FTEs in 2020 (a 14% increase) (http://bhpr.hrsa.gov/healthworkforce/supplydemand/usworkforce/primarycare/projectingprimarycare.pdf). While an anticipated more robust growth of nurse practitioners and physician assistants will partially compensate for this shortage, a deficiency of well-trained primary care personnel will persist and will translate into diminished opportunities for what should be regarded as the most cost-effective approach to improving the health of our population – preventive medicine. It is the primary care physician (the family physician, general practitioner, general internist or pediatrician) who is in the best position to understand the ecology of their patients and to take early actions to positively influence the attainment of healthy life styles. This will be increasingly the case as we move towards the implementation of precision medicine, with its promise to tailor interventions to the patient’s unique genotype (Bowdin et al., 2014).

4.4. Acceleration of basic and translational research to address the striking demographic changes of an aging society

A dynamic graphical representation of the extent to which the US population has been drifting towards higher proportions of older individuals can be viewed online: https://www.census.gov/dataviz/visualizations/055/. These trends are projected to continue well into the mid-century: https://www.census.gov/population/projections/files/analytical-document09.pdf. Centenarians have become the fastest growing subset of our population. During the period from 1980 to 2010, there was a 65.8% increase in the numbers of US centenarians, during which time the total US population increased by 36.3% (https://www.census.gov/prod/cen2010/reports/c2010sr-03.pdf.

The result is that there will be fewer and fewer younger members of our population to support the needs of the elderly, a growing number of whom are expected to suffer from chronic degenerative disorders, including several prevalent forms of dementia (frontotemporal dementias, Lewy Body dementias, multi-infarct dementias and the most prevalent forms – dementias with the characteristic pathologies of Alzheimer’s disease (Dickson and Weller, 2011). How are we to prepare for this “tsunami” of chronic diseases? Many of my colleagues argue that our best hope is to invest more funding for both basic and translational research into the emerging entity now being referred to as geroscience (Kennedy et al., 2014). Basic research using model organisms amenable to genetic analysis has documented promising approaches to retarding the rates of biological aging in human subjects and thus hopefully delaying and retarding the onset of age-related disorders (Kaeberlein et al., 2015). Some research suggests that interventions that can enhance longevity are likely to increase the ratio of Healthspan/Lifespan – in other words, there can be a compression of morbidity towards the end of an enhanced lifespan (Andersen et al., 2012; Fries et al., 2011). Others find less support for such an outcome (Crimmins and Beltran-Sanchez, 2011).

4.5. We will require gradual, incremental increases in the age of retirement to follow putative increases in our Healthspan/Lifespan ratios

A group of health economists used microsimulations to measure the impact upon costs of entitlement programs of interventions that slowed the rate of aging to produce modest increases in lifespans (2.2 years) (Goldman et al., 2013). (There are in fact such potential agents – for example, the development of mTOR inhibitors free of significant side effects when administered relatively late in the lifespan) (Harrison et al., 2009). Goldman and colleagues compared those results with scenarios in which there were linear 25% reductions in the rates of either heart disease or cancer over comparable periods of time (two decades) as well as the scenario of the status quo. These might be regarded as partial tests of two contrasting approaches to the enhancement of healthspans – the “one disease at a time hypothesis” versus what has been referred to as the “Longevity Dividend” hypothesis (Olshansky et al., 2007), whereby interventions that slow the rate of intrinsic aging would impact multiple chronic diseases and thus would be more cost effective. Goldman et al. concluded that “we see extremely large population health benefits in our delayed aging scenario”. To ensure the cost-effectiveness of such hypothetical increases in lifespan (and, hopefully, in healthspan/lifespan ratios), the authors suggested gradual increases in the ages of eligibility for Medicare from sixty-five to sixty-eight, and for Social Security from sixty-seven to sixty-eight, thus extending the Social Security Amendments of 1983.

4.6. We must develop a single payer system of publically funded universal health care

The Affordable Care Act, while having made medical insurance available to millions of additional Americans, still leaves millions of additional Americans either without insurance (http://kff.org/uninsured/fact-sheet/key-facts-about-the-uninsured-population/) or with serious degrees of underinsurance (http://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/fund-reports/2014/mar/americas-underinsured). Moreover, although there was early evidence of a degree of amelioration of health care costs under the act, more recent data shows trends of substantial cost increases, including future projections (http://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/blog/2015/dec/2015-health-care-in-review?omnicid=EALERT954793&mid=gmmartin@uw.edu). The Affordable Care Act is an extraordinarily complex piece of legislation, with more than 7 megabytes of information (http://www.hhs.gov/healthcare/about-the-law/read-the-law/index.html). Serious problems are beginning to arise because of the complex administrative structure and decreases in the anticipated federal subsidies, a recent example being the financial failure of a previously successful extensive health care system in Colorado (http://www.coloradoindependent.com/155753/heres-what-happened-to-colorados-health-co-op).

The Affordable Care Act permits individual states, beginning in 2017, to apply for waivers for the creation of innovative programs of health care, including publically funded single payer programs. The state of Vermont developed a highly successful grass-roots campaign that led to such legislation but it lost support of the Governor because of the perception of excessive costs (Fox and Blanchet, 2015). While several other states are in the process of proposing similar legislation, there are both political and economic problems in their implementations, in part because they cannot include funding from existing federal programs such as Medicare. The obvious solution is the passage of federal legislation that will provide a publically funded universal health program for the entire nation. There are two approaches to this goal. The first is the gradual lowering of the ages of eligibility for Medicare, often referred to as “Medicare for All” or, given the current limitations of Medicare, such as the lack of long term care, “Improved Medicare for All” (see the highly informative daily email communications of Dr. Don McCanne on this subject, http://www.pnhp.org/news/quote-of-the-day). The other approach is federal legislation to immediately initiate a single payer system of universal health care. Such legislation (HR 676) has in fact been recently re-introduced in the US House of Representatives by the Honorable John Conyers of Michigan (https://www.congress.gov/bill/113th-congress/house-bill/676). An economic analysis of the anticipated impact of that legislation has been published by Professor Gerald Friedman, Chair of the Department of Economics of the University of Massachusetts-Amherst (http://www.pnhp.org/sites/default/files/Funding%20HR%20676_Friedman_7.31.13_proofed.pdf). His calculations indicate a savings of almost $600 billion dollars in the first year and 1.8 trillion dollars over the first decade, largely from greatly reduced administrative and pharmaceutical costs. The paper emphasized that some $51 billion of these savings could fund the retraining of displaced workers and the phasing out of investor owned, for-profit delivery systems.

4.7. The development of a public educational campaign that provides evidence on how the ethics of community solidarity and universal health care are cost-effective as well as humanitarian

Legislation such as 676 is unlikely to be passed in the absence of a massive grass roots educational campaign. It is our responsibility as physicians, nurses, economists, public health workers, educators and civic leaders to organize such a campaign. Earlier in this paper the importance of basic and translational research leading to more effective preventive and personalized medicine was discussed. I want to once again emphasize that such research can impact the health and well-being of all age groups, certainly including our geriatric patients. Moreover, it is often not appreciated that a single payer system of health care has the potential, via a unified and comprehensive electronic database, to greatly expedite population-based epidemiological research. An example of an exceptionally well designed study, made possible by the French integrated, universal system of health care data, demonstrated evidence for a role of automotive vehicular traffic density and benzene exposure in the pathogenesis of childhood leukemia (Houot et al., 2015)

Given the above, the author would like to conclude with a modest proposal: Assuming HR 676 or some similar legislation will eventually become the law of the land, let us urge our congressional representatives to utilize $3 billion of the anticipated annual savings to enlarge the budget of the National Institutes of Health and thus substantially accelerate the rate of progress of such research. An anticipated result of such accelerated progress would be a “positive feedback” upon accelerated rates of improvements in the public health and thus substantial additional savings for our tax payers.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks Joel T. Braslow and Martha L. Schmidt for helpful comments on earlier drafts of this manuscript

Footnotes

Disclosures

The author is an unpaid member of the Board of Directors of the Western Washington Chapter of Physicians for a National Health Program and a member of its parental non-profit national organization (http://www.pnhp.org/), a group of some 20,000 physicians, medical students and health professionals who support a national single payer system of universal health care.

References

- Alberts B. Getting education right. Science. 2011;333:919. doi: 10.1126/science.1212394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alesina A, Glaeser E, Sacerdote B. Why doesn’t the United States have a European-style welfare state? Brook Pap Econ Act. 2001:187–277. [Google Scholar]

- Andersen SL, Sebastiani P, Dworkis DA, Feldman L, Perls TT. Health span approximates life span among many supercentenarians: compression of morbidity at the approximate limit of life span. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2012;67:395–405. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glr223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernhard D, Moser C, Backovic A, Wick G. Cigarette smoke—an aging accelerator? Exp Gerontol. 2007;42:160–165. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2006.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohacek J, Mansuy IM. Molecular insights into transgenerational non-genetic inheritance of acquired behaviours. Nat Rev Genet. 2015;16:641–652. doi: 10.1038/nrg3964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowdin S, Ray PN, Cohn RD, Meyn MS. The genome clinic: a multidisciplinary approach to assessing the opportunities and challenges of integrating genomic analysis into clinical care. Hum Mutat. 2014;35:513–519. doi: 10.1002/humu.22536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler RN. Being old in America. Harper & Row; New York: 1975. Why survive? [Google Scholar]

- Casagrande SS, Cowie CC, Genuth SM. Self-reported prevalence of diabetes screening in the U.S., 2005–2010. Am J Prev Med. 2014;47:780–787. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2014.07.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen A, Oster E, Williams HL National Bureau of Economic Research. Why is Infant Mortality Higher in the US Than in Europe? National Bureau of Economic Research; Cambridge, MA: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Chin-Lun Hung G, Hahn J, Alamiri B, Buka SL, Goldstein JM, Laird N, Nelson CA, Smoller JW, Gilman SE. Socioeconomic Disadvantage and Neural Development from Infancy through Early Childhood. Int J Epidemiol. 2015;44:1889–1899. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyv303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collado MD, Iturbe-Ormaetxe I. Public transfers to the poor: is Europe really much more generous than the United States? Int Tax Public Financ. 2010;17:662–685. [Google Scholar]

- Crimmins EM, Beltran-Sanchez H. Mortality and morbidity trends: is there compression of morbidity? J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2011;66:75–86. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbq088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickson D, Weller RO. Neurodegeneration: The Molecular Pathology of Dementia and Movement Disorders. xvii. Wiley-Blackwell; Chichester, West Sussex; Hoboken, NJ: 2011. p. 177. [Google Scholar]

- Ezzati M, Friedman AB, Kulkarni SC, Murray CJ. The reversal of fortunes: trends in county mortality and cross-county mortality disparities in the United States. PLoS Med. 2008;5:e66. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flavin P. Lobbying regulations and political equality in the American States. Am Polit Res. 2015;43:304–326. [Google Scholar]

- Fox AM, Blanchet NJ. The little state that couldn’t could? The politics of “single-payer” health coverage in Vermont. J Health Polit Policy Law. 2015;40:447–485. doi: 10.1215/03616878-2888381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fries JF, Bruce B, Chakravarty E. Compression of morbidity 1980–2011: a focused review of paradigms and progress. J Aging Res. 2011;2011:261702. doi: 10.4061/2011/261702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilens M, Page BI. Testing theories of American politics: elites, interest groups, and average citizens. Perspect Polit. 2014;12:564–581. [Google Scholar]

- Goldman DP, Cutler D, Rowe JW, Michaud PC, Sullivan J, Peneva D, Olshansky SJ. Substantial health and economic returns from delayed aging may warrant a new focus for medical research. Health Aff (Millwood) 2013;32:1698–1705. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.0052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hacker JS, Pierson P. American Amnesia: how the War on Government led us to Forget What Made America Prosper. Simon & Schuster; New York: 2016. First Simon & Schuster hardcover edition. [Google Scholar]

- Halaweish I, Alam HB. Changing demographics of the American population. Surg Clin North Am. 2015;95:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.suc.2014.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison DE, Strong R, Sharp ZD, Nelson JF, Astle CM, Flurkey K, Nadon NL, Wilkinson JE, Frenkel K, Carter CS, et al. Rapamycin fed late in life extends lifespan in genetically heterogeneous mice. Nature. 2009;460:392–395. doi: 10.1038/nature08221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Himmelstein DU, Thorne D, Warren E, Woolhandler S. Medical bankruptcy in the United States, 2007: results of a national study. Am J Med. 2009;122:741–746. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2009.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houot J, Marquant F, Goujon S, Faure L, Honore C, Roth MH, Hemon D, Clavel J. Residential proximity to heavy-traffic roads, benzene exposure, and childhood leukemia—the GEOCAP study, 2002–2007. Am J Epidemiol. 2015;182:685–693. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwv111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joubert BR, Felix JF, Yousefi P, Bakulski KM, Just AC, Breton C, Reese SE, Markunas CA, Richmond RC, Xu CJ, et al. DNA methylation in newborns and maternal smoking in pregnancy: genome-wide consortium meta-analysis. Am J Hum Genet. 2016;98:680–696. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2016.02.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaeberlein M, Rabinovitch P, Martin GM. Healthy aging: the ultimate preventative medicine. Science. 2015;350:1191–1193. doi: 10.1126/science.aad3267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy BK, Berger SL, Brunet A, Campisi J, Cuervo AM, Epel ES, Franceschi C, Lithgow GJ, Morimoto RI, Pessin JE, et al. Geroscience: linking aging to chronic disease. Cell. 2014;159:709–713. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.10.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Light DW, Lexchin J. Foreign free riders and the high price of US medicines. BMJ. 2005;331:958–960. doi: 10.1136/bmj.331.7522.958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDorman MF, Matthews TJ, Mohangoo AD, Zeitlin J. International comparisons of infant mortality and related factors: United States and Europe, 2010. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2014;63:1–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin GM. Interactions of aging and environmental agents: the gerontological perspective. Prog Clin Biol Res. 1987;228:25–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray CJ, Atkinson C, Bhalla K, Birbeck G, Burstein R, Chou D, Dellavalle R, Danaei G, Ezzati M, Fahimi A, et al. The state of US health, 1990–2010: burden of diseases, injuries, and risk factors. JAMA. 2013;310:591–608. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.13805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olshansky SJ, Perry D, Miller RA, Butler RN. Pursuing the longevity dividend: scientific goals for an aging world. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2007;1114:11–13. doi: 10.1196/annals.1396.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philipson T, Eber M, Lakdawalla DN, Corral M, Conti R, Goldman DP. An analysis of whether higher health care spending in the United States versus Europe is ‘worth it’ in the case of cancer. Health Aff (Millwood) 2012;31:667–675. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.1298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossen LM, Schoendorf KC. Trends in racial and ethnic disparities in infant mortality rates in the United States, 1989–2006. Am J Public Health. 2014;104:1549–1556. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sen A, Cingolani P, Senut MC, Land S, Mercado-Garcia A, Tellez-Rojo MM, Baccarelli AA, Wright RO, Ruden DM. Lead exposure induces changes in 5-hydroxymethylcytosine clusters in CpG islands in human embryonic stem cells and umbilical cord blood. Epigenetics. 2015;10:607–621. doi: 10.1080/15592294.2015.1050172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner MK. Endocrine disruptors in 2015: epigenetic transgenerational inheritance. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2015;12:68–70. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2015.206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorrentino JA, Sanoff HK, Sharpless NE. Defining the toxicology of aging. Trends Mol Med. 2014;20:375–384. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2014.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soubry A. Epigenetic inheritance and evolution: a paternal perspective on dietary influences. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 2015;118:79–85. doi: 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2015.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone DA. The struggle for the soul of health insurance. J Health Polit Policy Law. 1993;18:287–317. doi: 10.1215/03616878-18-2-287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker J, Halbesma N, Lone N, McAllister D, Weir CJ, Wild SH Scottish Diabetes Research Network Epidemiology, G. Socioeconomic status, comorbidity and mortality in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus in Scotland 2004–2011: a Cohort study. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2015 doi: 10.1136/jech-2015-206702. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/jech-2015-206702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Yuan TF, Li A, Sun X, Ouyang H, Campos C, Rocha NB, Arias-Carrion O, Machado S, Hou G, So KF. Transgenerational inheritance of paternal neurobehavioral phenotypes: stress, addiction, ageing and metabolism. Mol Neurobiol. 2015 doi: 10.1007/s12035-015-9526-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]