Abstract

Background

The yield of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.), an important crop, is adversely affected by heat stress in many regions of the world. However, the molecular mechanisms underlying thermotolerance are largely unknown.

Results

A novel ferritin gene, TaFER, was identified from our previous heat stress-responsive transcriptome analysis of a heat-tolerant wheat cultivar (TAM107). TaFER was mapped to chromosome 5B and named TaFER-5B. Expression pattern analysis revealed that TaFER-5B was induced by heat, polyethylene glycol (PEG), H2O2 and Fe-ethylenediaminedi(o-hydroxyphenylacetic) acid (Fe-EDDHA). To confirm the function of TaFER-5B in wheat, TaFER-5B was transformed into the wheat cultivar Jimai5265 (JM5265), and the transgenic plants exhibited enhanced thermotolerance. To examine whether the function of ferritin from mono- and dico-species is conserved, TaFER-5B was transformed into Arabidopsis, and overexpression of TaFER-5B functionally complemented the heat stress-sensitive phenotype of a ferritin-lacking mutant of Arabidopsis. Moreover, TaFER-5B is essential for protecting cells against heat stress associated with protecting cells against ROS. In addition, TaFER-5B overexpression also enhanced drought, oxidative and excess iron stress tolerance associated with the ROS scavenging. Finally, TaFER-5B transgenic Arabidopsis and wheat plants exhibited improved leaf iron content.

Conclusions

Our results suggest that TaFER-5B plays an important role in enhancing tolerance to heat stress and other abiotic stresses associated with the ROS scavenging.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s12870-016-0958-2) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: TaFER-5B, Heat stress, Abiotic stress, Ferritin-lacking mutant, Wheat, Arabidopsis

Background

Most of the world’s wheat growing areas are frequently subject to heat stress during the growing season. High temperatures adversely affect wheat yield and quality [1]. Over the past three decades (1980–2008), heat stress has caused a decrease of 5.5% in global wheat yields [2]. Thus, research on the molecular mechanism of thermotolerance and the development of new wheat tolerant varieties using classical breeding techniques and biotechnological approaches is increasingly important. As sessile organisms, plants have evolved various response mechanisms to adapt to abiotic stress, particularly molecular responses to maintain normal life activities [3–6]. Genes that respond to adverse growth conditions are essential for enhancing abiotic stress tolerance and developing stress-tolerant crops.

Iron is an essential nutrient for all cells. However, excess free iron is harmful to cells because it promotes the formation of free radicals via the Fenton reaction. Thus, iron homeostasis must be well controlled. As iron-storage proteins, ferritins play important roles in sequestering or releasing iron upon demand [7]. Ferritins are a class of 450-kDa proteins consisting of 24 subunits, which are present in all cell types [8]. In contrast to animal ferritins, subcellular localization of plant ferritins in the cytoplasm has not been reported. Plant ferritins are exclusively targeted to plastids and mitochondria [9–12]. The model plant Arabidopsis contains four ferritin genes: AtFER1, AtFER2, AtFER3 and AtFER4. Hexaploid wheat contains two ferritin genes that map to chromosomes 5 and 4, and each of the individual homeoalleles can be located to the A, B or D genome [13]. Thus, ferritin genes are conserved throughout the plant kingdom, and two genes per genome have been identified in all studied cereals [13].

Transcriptome analysis of plant responses to stress has identified a number of genes. In plants, ferritin gene expression was induced in response to drought, salt, cold, heat and pathogen infection [9, 14]. Arabidopsis ferritin genes were induced by treatment with H2O2, iron and abscisic acid (ABA); however, not all four AtFER genes were induced [15]. Ferritin was up-regulated in response to drought in the SSH (Suppression Subtractive Hybridization) cDNA library of soybean nodules [16]. Overexpression of ferritin also significantly improved abiotic stress tolerance in grapevine plants [17].

Oxidative damage of biomolecules is a common trait of abiotic stress. If oxidative damage is not well controlled, it can ultimately trigger programmed cell death (PCD) [18]. Thus, reactive oxygen species (ROS) must be tightly managed by enhancing ROS scavenging and/or reinforcing pathways preventing ROS production. In addition to buffering iron, previous studies have also revealed that plant ferritins protect cells against oxidative damage [19]. However, little information is known about ferritin gene functions involved in tolerance to heat and other abiotic stresses. We previously analysed the genome-wide expression profiles of wheat under heat-stress conditions and identified a large number of genes responding to heat stress, including ferritin genes [14]. In the present study, the expression patterns of TaFER-5B in seedlings treated by various stress were studied, and the relationship between ferritins and thermotolerance was elaborated.

Results

Cloning of a ferritin-encoding gene, TaFER-5B, from wheat (Triticum aestivum L.)

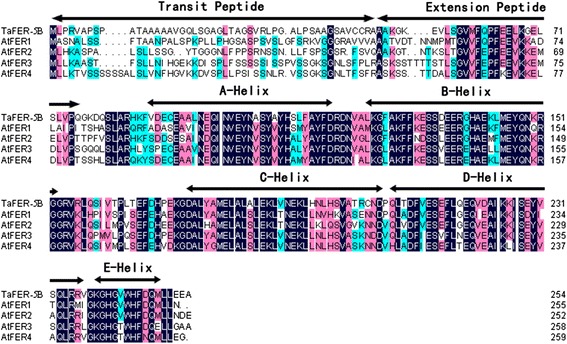

Microarray analysis using the Affymetrix Genechip® Wheat Genome Array indicated that the probe Ta.681.1.S1_x_at was induced 29.08-fold after high-temperature treatment for 1 h [14]. Based on the probe sequence, we cloned the full-length open reading frame of this gene (TaFER, accession no. GenBank KX025176; Additional file 1) from wheat cultivar “TAM107”. The coding sequence shares 97.15%, 99.66%, and 97.15% homology with sequences on chromosomes 5A, 5B, and 5D, respectively, of the recently published wheat cultivar Chinese Spring (CS) genome (International Wheat Genome Sequencing Consortium, 2014). The sequence on chromosome 5B corresponds to the original heat-responsive transcript named TaFER-5B. Comparison of the amino acid sequences between TaFER-5B and ferritin genes from the model plant Arabidopsis revealed that TaFER-5B is a conserved gene containing the transit peptide domain responsible for plastid localization, an adjoined extension peptide domain involved in protein stability and five helixes (Fig. 1) [20–22]. The amino acid sequence of TaFER-5B exhibits 60.47% identity with AtFER1, 62.26% identity with AtFER2, 61.69% identity with AtFER3, and 60.92% identity with AtFER4 (Fig. 1), and phylogenetic tree analysis revealed higher identity with the ferritins from maize, rice and barley (Additional file 2: Figure S1; Additional file 3).

Fig. 1.

Sequence alignment of TaFER-5B and previously reported ferritin genes AtFER1-4 in Arabidopsis. Regions corresponding to the ferritin domains are indicated by arrows

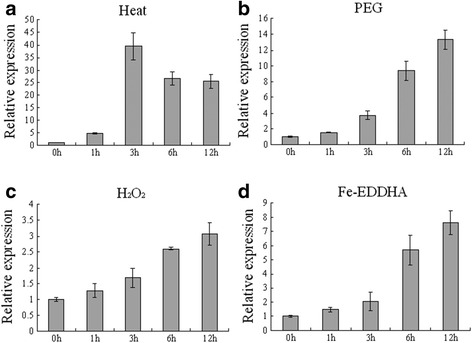

The TaFER-5B gene is expressed in response to different stress treatments

The expression patterns of ferritin genes in wheat under diverse abiotic stress conditions were analysed by RT-qPCR using gene-specific primers (Fig. 2). TaFER-5B expression increased significantly and peaked at 3 h after heat treatment at 40 °C. After long-term heat-stress treatment (12 h), TaFER-5B expression decreased, but increased mRNA abundance was maintained (Fig. 2a). We also analysed the expression level of TaFER-5B under PEG, H2O2 and Fe-EDDHA conditions. TaFER-5B expression gradually increased and peaked at 12 h of treatment (Fig. 2b, c and d). These results demonstrate that TaFER-5B expression is induced by heat, PEG, H2O2 and Fe-EDDHA treatment.

Fig. 2.

Expression pattern of TaFER-5B under heat (a), PEG (b), H2O2 (c) and Fe-EDDHA treatment (d) as assessed by RT-qPCR. The data represent the means of three replicates ± SD

TaFER-5B overexpression in wheat enhances thermotolerance at the seedling stage

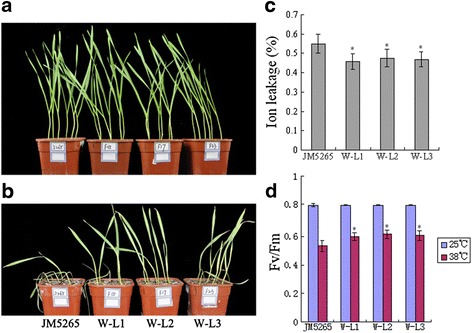

To gain insight into the function of TaFER-5B, TaFER-5B under the control of the maize ubiquitin promoter was transformed into wheat cultivar Jimai5265 (JM5265) by particle bombardment. In total, 15 transgenic events were produced, and integration of the ferritin gene was confirmed by PCR analysis with specific corresponding primers. The transgenic lines were analysed over the T1 and T2 generations. Three lines (W-L1, W-L2 and W-L3) that exhibited up-regulation of TaFER-5B in shoots at the early seedling stage (Additional file 4: Figure S2) were selected for further analysis.

Growth and stress resistance phenotypes were investigated at the seedling stage grown under normal and heat-stress conditions. Under normal conditions, the TaFER-5B transgenic lines exhibited no obvious differences (Fig. 3a). However, under heat-stress conditions, wild type (WT) wilted more rapidly than the TaFER-5B transgenic lines after heat stress at 45 °C for 18 h and recovery at 22 °C for 5 d. (Fig. 3b). As a parameter for evaluating stress-induced membrane injury, electrolyte leakage is often used to analyse plant tolerance to stress. Thus, we further evaluated electrolyte leakage with detached leaves under heat-stress conditions. The TaFER-5B transgenic lines exhibited reduced electrolyte leakage with detached leaves compared with JM5265 under heat-stress conditions (Fig. 3c). Under heat-stress conditions, photosynthetic activity was markedly reduced and accompanied by direct and indirect photosynthetic system damage. The ratio of variable to maximal fluorescence (Fv/Fm) is an important parameter used to assess the physiological status of the photosynthetic apparatus. Environmental stress that affects photosystem II efficiency decreases Fv/Fm. Previous studies have indicated that disturbance of the electron flow under moderate heat stress might be an important determinant of heat-derived damage of the photosynthetic system [23]. Fv/Fm values in TaFER-5B transgenic lines were increased compared with JM5265 under heat-stress conditions, whereas no significant difference was observed under control conditions (Fig. 3d). These results indicate that TaFER-5B protects photosynthetic activity under heat-stress conditions.

Fig. 3.

Thermotolerance assay of TaFER-5B transgenic wheat plants at the seedling stage. a Phenotype of 10-day-old JM5265 and three TaFER-5B transgenic wheat lines, W-L1, W-L2 and W-L3, before heat treatment. b 5-day-old JM5265 and three TaFER-5B transgenic wheat lines, W-L1, W-L2 and W-L3, were treated at 45 °C for 18 h, and photographs were taken after 5 d recovery at 22 °C. c Ion leakage assay of the seedlings in (a) after heat treatment. d Maximum efficiency of PSII photochemistry (Fv/Fm ratio) in the seedlings in (a) after heat treatment at 38 °C for 2 h. The data represent mean values ± SD of three independent experiments. (* indicates significance at P < 0.05)

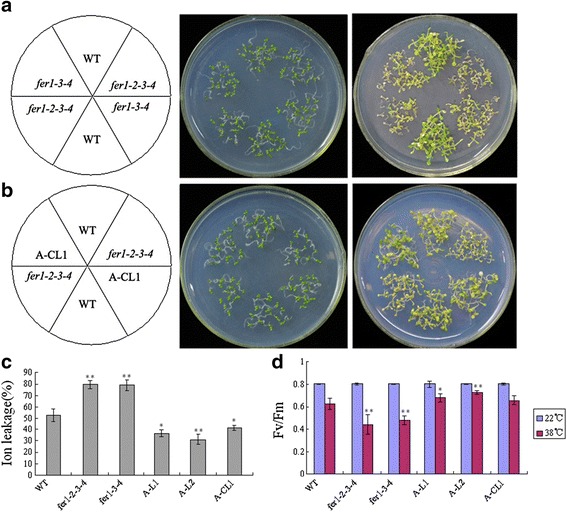

Arabidopsis ferritin-lacking mutants display heat stress-sensitive phenotypes and are rescued by TaFER-5B overexpression

The role of the ferritin gene in thermotolerance in Arabidopsis has not been characterized. To determine whether the function of ferritin from mono- and dico-species is conserved, the Arabidopsis ferritin gene triple mutant fer1-3-4 (lacking three isoforms expressed in vegetative tissues, AtFER1, 3 and 4) and quadruple mutant fer1-2-3-4 (lacking all ferritin isoforms) were created by crossing the single mutant as described previously [19, 24] (Additional file 5: Figure S3). Then, we transformed 35S::TaFER-5B into WT and fer1-2-3-4 plants. Detection of protein expression levels by Western blot analysis revealed that the expression level of ferritin increased in the overexpression lines (A-L1 and A-L2) compared with WT (Additional file 6: Figure S4A) but decreased in fer1-2-3-4 and fer1-3-4 plants compared with WT (Additional file 6: Figure S4B). As shown in Additional file 6: Figure S4B, ferritin protein levels in fer1-2-3-4 plants complemented by the TaFER-5B gene (A-CL1) were very similar to those in WT plants. No obvious morphological differences were observed in the transgenic lines at different developmental stages (data not shown).

Thus, fer1-2-3-4, fer1-3-4, A-L1, A-L2, A-CL1 and WT plants were analysed in further experiments. First, we examined the survival rate of these lines after heat stress. Briefly, 7-day-old seedlings grown at 22 °C were subjected to heat-stress treatment at 45 °C for 2 h. After recovery at 22 °C for 7 days, only 10% of fer1-2-3-4 and fer1-3-4 plants survived, whereas approximately 70% of WT plants survived (Fig. 4a). As shown in Fig. 4b, TaFER-5B overexpression functionally complemented the heat stress-sensitive phenotype of fer1-2-3-4 plants. In addition, TaFER-5B transgenic lines also exhibited an enhanced thermotolerance phenotype compared with WT plants (data not show). We further evaluated electrolyte leakage with detached leaves under heat-stress conditions. Detached leaves of fer1-2-3-4 and fer1-3-4 leaked more electrolytes than WT and A-CL1 leaves, whereas A-L1 and A-L2 leaked fewer electrolytes than WT leaves (Fig. 4c). Fv/Fm values were A-L2 > A-L1 > A-CL1 > WT > fer1-3-4 > fer1-2-3-4 under heat-stress conditions, whereas no significant differences were observed under control conditions (Fig. 4d). These results also suggest a role of TaFER-5B in thermotolerance in Arabidopsis.

Fig. 4.

Arabidopsis ferritin-lacking mutants displaying a heat stress-sensitive phenotype were rescued by overexpression of TaFER-5B. a 6-day-old seedlings of WT, fer1-3-4 and fer1-2-3-4 were treated at 45 °C for 2 h, and photographs were taken after 7-d recovery at 22 °C. b 6-day-old seedlings of WT, fer1-2-3-4 and A-CL1 (complemented line) were treated at 45 °C for 2 h, and photographs were taken after 7-d recovery at 22 °C. c Ion leakage assays of fer1-2-3-4, fer1-3-4, WT, overexpression lines A-L1 and A-L2 and complemented line A-CL1 seedlings after heat treatment. d Maximum efficiency of PSII photochemistry (Fv/Fm ratio) of fer1-2-3-4, fer1-3-4, WT, overexpression lines A-L1 and A-L2 and complemented line A-CL1 seedlings at 22 °C and 38 °C. The data represent mean values ± SD of three independent experiments. (* indicates significance at P < 0.05; ** indicates significance at P < 0.01)

Ferritin enhances thermotolerance associated with the ROS scavenging

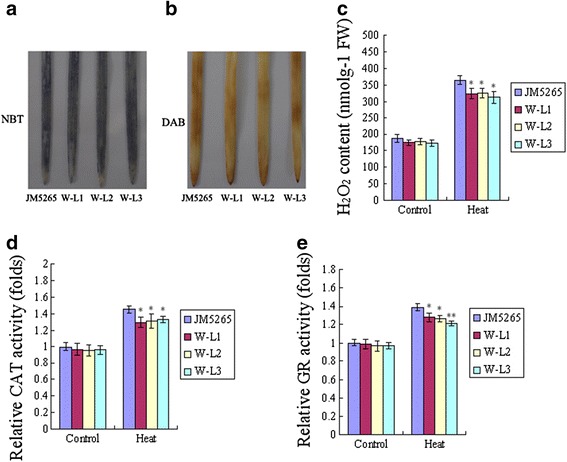

A number of recent studies have suggested that ferritin protects plant cells from oxidative damage induced by a wide range of stress. Under normal conditions, the fer1-3-4 mutant leads to enhanced ROS production and increased activity of several reactive oxygen species (ROS) detoxifying enzymes in leaves and flowers [19]. These results indicate that fer1-3-4 compensates for and bypasses the lack of safe iron storage in ferritins by increasing the capacity of ROS-detoxifying mechanisms [19]. However, when Arabidopsis plants are irrigated with 2 mM Fe-EDDHA, the lack of ferritins in fer1-3-4 plants strongly impairs plant growth and fertility. Thus, under high-iron conditions, free-iron-associated ROS production overwhelms the scavenging mechanisms activated in the fer1-3-4 mutant [19]. To further determine whether ferritin enhances thermotolerance associated with protecting cells against ROS, we evaluated the accumulation of superoxide radical anions (O2−) and H2O2 under heat-stress conditions. O2− was detected with nitroblue tetrazolium (NBT) staining, and H2O2 was measured by diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride (DAB) staining [25]. We also examined the H2O2 content and the enzyme activities of catalase (CAT) and glutathione reductase (GR) under normal and heat-stress conditions.

In wheat, transgenic lines accumulated less ROS than JM5265 under stress conditions (Fig. 5a and b). CAT and GR enzyme activities were also positively correlated with ROS content (Fig. 5c and d). These results indicate that overexpression of TaFER-5B in wheat effectively alleviates the accumulation of ROS.

Fig. 5.

Detection of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in wheat after heat treatment at 45 °C for 1 h. a O2 − accumulation in 7-day-old wheat leaves detected with NBT. b H2O2 accumulation in 7-day-old wheat leaves detected with DAB. c H2O2 content in 7-day-old JM5265 and transgenic wheat seedlings. d The activity of the antioxidant enzyme CAT in 7-day-old JM5265 and transgenic wheat seedlings. e The activity of the antioxidant enzyme GR in 7-day-old JM5265 and transgenic wheat seedlings. The data represent mean values ± SD of three independent experiments. (* indicates significance at P < 0.05; ** indicates significance at P < 0.01)

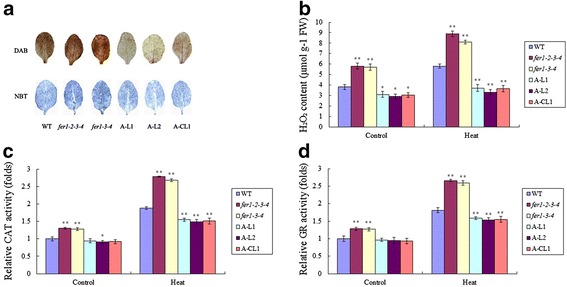

In Arabidopsis, even under normal conditions, differences were noted among fer1-2-3-4, fer1-3-4, A-L1, A-L2, A-CL1 and WT plants. Compared with WT, fer1-2-3-4 and fer1-3-4 exhibited enhanced H2O2 content and CAT and GR activities, consistent with a previous report [19]. In overexpression and complemented lines, the O2− and H2O2 content and the two enzyme activities decreased (Fig. 6a, b, c and d). These results indicate that overexpression of TaFER-5B in Arabidopsis effectively alleviated the accumulation of ROS.

Fig. 6.

Detection of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in Arabidopsis. a H2O2 accumulation was detected with DAB in 3-week-old rosette leaves after heat treatment at 45 °C for 1 h. O2 − accumulation was detected with NBT in 3-week-old rosette leaves after heat treatment at 45 °C for 1 h. b H2O2 content in 10-day-old seedlings after heat treatment at 45 °C for 1 h. c The activity of the antioxidant enzyme CAT in 10-day-old seedlings after heat treatment at 45 °C for 1 h. d The activity of the antioxidant enzyme GR in 10-day-old seedlings after heat treatment at 45 °C for 1 h. The data represent mean values ± SD of three independent experiments. (* indicates significance at P < 0.05; ** indicates significance at P < 0.01)

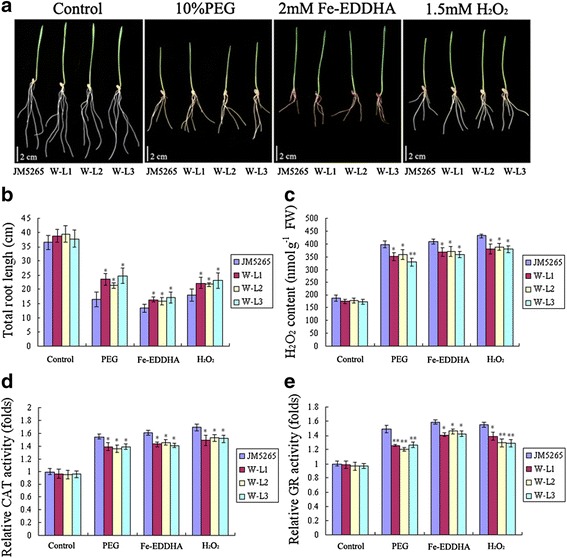

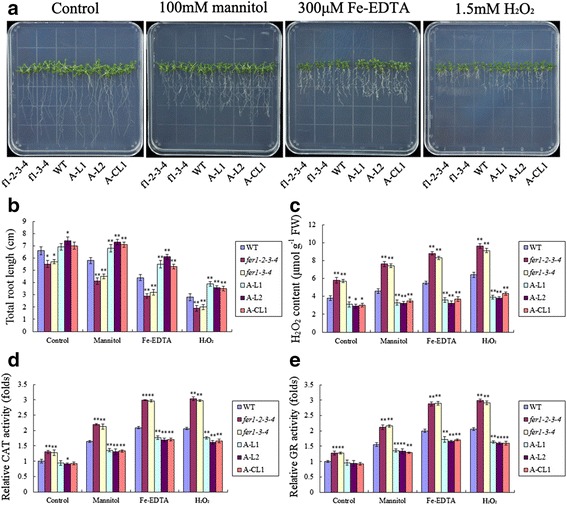

TaFER-5B overexpression also enhances tolerance to drought stress, oxidative stress and excess iron stress associated with the ROS scavenging

As mentioned above, TaFER-5B was also induced by PEG, H2O2 and excess iron treatment (Fig. 2b, c and d), suggesting that TaFER-5B may be involved in an intricate network for abiotic stress responses. To investigate the role of TaFER-5B in these abiotic stresses, we examined the effect of TaFER-5B on drought stress, oxidative stress and excess iron stress tolerance in wheat. The TaFER-5B transgenic lines exhibited significantly greater total root length in the presence of 10% PEG, 2 mM Fe-EDDHA or 1.5 mM H2O2 (Figs. 7a and b). The H2O2 content and CAT and GR enzyme activities were also dramatically decreased in the TaFER-5B transgenic lines (Fig. 7c, d and e). These results suggest that overexpression of TaFER-5B in wheat enhances drought, oxidative and excess iron stress tolerance associated with the ROS scavenging. In Arabidopsis, we also investigated tolerance to the above stresses in fer1-2-3-4, fer1-3-4, A-L1, A-L2, A-CL1 and WT plants. After 10 d of exposure to 10% PEG, 2 mM Fe-EDDHA or 1.5 mM H2O2, the total roots of the A-L1, A-L2 and A-CL1 lines were significantly longer than those of WT and fer1-2-3-4 (Fig. 8a and b). Consistent with this result, H2O2 content and CAT and GR activities were significantly decreased in the A-L1, A-L2 and A-CL1 lines compared to WT and fer1-2-3-4 (Fig. 8c, d and e). These data indicate that TaFER-5B is essential for enhancing abiotic stress tolerance associated with the ROS scavenging.

Fig. 7.

Drought, oxidative, excess iron stress tolerance assay and ROS accumulation analysis of TaFER-5B transgenic wheat plants. a Phenotypes of 10-day-old wheat plants overexpressing TaFER-5B under control, mannitol, Fe-EDTA and H2O2 conditions. b Total root length statistics for the roots of the 10-day-old seedlings in (a). c H2O2 content in 10-day-old seedlings in (a). d The activity of the antioxidant enzyme CAT in the seedlings in (a). e The activity of the antioxidant enzyme GR in the seedlings in (a). The data represent mean values ± SD of three independent experiments. (* indicates significance at P < 0.05; ** indicates significance at P < 0.01)

Fig. 8.

Drought, oxidative, excess iron stress tolerance assay and ROS accumulation analysis of Arabidopsis ferritin-lacking mutants, TaFER-5B-overexpressing lines and complemented lines. a Phenotypes of 10-day-old Arabidopsis ferritin-lacking mutants, TaFER-5B-overexpressing lines and complemented lines before and after mannitol, Fe-EDTA and H2O2 treatment. b Total root length statistics for the roots of the 10-day-old seedlings in (a). c H2O2 content in the 10-day-old seedlings in (a). d The activity of the antioxidant enzyme CAT in the seedlings in (a). e The activity of the antioxidant enzyme GR in the seedlings in (a). The data represent mean values ± SD of three independent experiments. (* indicates significance at P < 0.05; ** indicates significance at P < 0.01)

TaFER-5B overexpression improves the iron content in the leaves but not seeds of transgenic plants

To confirm the function of TaFER-5B in improving iron content in transgenic plants, ICP-AAS was used to analyse the iron concentration. In the shoots of transgenic Arabidopsis plants and mutants before bolting, the iron content displayed the same trend as ferritin protein levels (Fig. 9a and Additional file 6: Figure S4), and 10-day-old transgenic wheat plants exhibited similar results (Fig. 9b). As a major crop, we were more concerned about the iron content in the seeds of transgenic wheat. However, the results revealed no significantly differences in iron content in seeds between JM5265 and transgenic plants (Fig. 9c). This finding is consistent with the previous results [26]. Previous overexpression of GmFer in wheat and rice driven by the maize ubiquitin promoter resulted in improvements in the iron content in the vegetable tissue without significant changes in seeds. Supporting this finding, Arabidopsis ferritins store only approximately 5% of the total seed iron and do not constitute the major seed iron pool [19].

Fig. 9.

Iron content in Arabidopsis and wheat. a Iron content in leaves of 3-week-old TaFER-5B transgenic plants, ferritin-lacking Arabidopsis mutants and complemented lines in Arabidopsis before bolting. b Iron content in wheat shoots of 10-day-old TaFER-5B transgenic plants. c Iron content in dry wheat seeds of TaFER-5B transgenic plants. The data represent mean values ± SD of three independent experiments. (* indicates significance at P < 0.05; ** indicates significance at P < 0.01)

Discussion

Heat and drought stress have an adverse impact on crop productivity and quality worldwide. Plants have evolved various response mechanisms for heat and drought stress, particularly molecular responses, to maintain normal life activities [3, 4, 27]. Forward and reverse genetics have been applied to identify key molecular factors that facilitate crop acclimation to environmental stress. In this study, we successfully cloned the gene TaFER-5B and elucidated its function in tolerance to heat and other abiotic stresses in Arabidopsis and wheat.

TaFER-5B possesses the typical features of plant ferritins

Plant and animal ferritins evolved from a common ancestor gene. Animal ferritins contain two types of subunits, referred to as H- and L-chains. All plant ferritins all share higher identity with the H-chains of animal ferritins. In cereals, there are two ferritin genes per haploid genome. In hexaploid wheat, TaFer1 and TaFer2 are located on chromosomes 5 and 4, respectively, and three homeoalleles of each gene are located in the A, B and D genomes, respectively [13]. Similar to other plant ferritin genes, the gene structure of TaFER-5B contains seven introns and eight exons (data not show). Ferritin subunits are synthesized as a precursor, and the N-terminal sequence consists of two domains: the transit peptide and the extension peptide (Fig. 1a). The transit peptide domain has higher variability and is absent in the mature ferritin subunit; the transit peptide domain is responsible for plastid localization. The adjacent extension peptide domain present in the mature ferritin subunit is involved in protein stability [28]. In sea lettuce ferritins, the extension peptide contributes to shell stability and surface hydrophobicity [29]. The removal of the extension peptide in pea seed ferritin both increases protein stability and promotes the reversible dissociation of the mature ferritin protein [30]. The secondary structure of pea seed ferritin is highly similar to that of mammalian ferritin [31]. The ferritin cage structure is assembled from 24 individual four-helix bundle subunits (A, B, C, and D in Fig. 1a) and is conserved in plant and animal ferritins. In plants, which diverged from their animal counterparts, the ferritins also contain a smaller and highly conserved C-terminal E-helix that participates in the formation of the fourfold axis and is involved in electron transfer [21].

The expression of ferritins is modulated by heat stress and other abiotic stresses

In this study, the probe corresponding to TaFER-5B was induced by heat stress [14]. RT-qPCR analysis demonstrated that this gene was induced by heat treatment and peaked at 3 h of treatment (Fig. 2a). We also analysed the expression profiles of TaFER-4A, TaFER-4B, TaFER-4D, TaFER-5A, TaFER-5B and TaFER-5D under drought stress, heat stress and their combination in the expression database (http://wheat.pw.usda.gov/WheatExp/) [32]. TaFER-5A, TaFER-5B and TaFER-5D were all induced by drought stress, heat stress and their combination (Additional file 7: Figure S5). These results indicate that, in addition to functioning as the iron storage protein in the development stages, plant ferritins may also function as stress-responsive proteins. Previous studies have demonstrated that ferritin gene expression is induced by heat treatment. PpFer4 expression was significantly induced by 6 h of treatment at 40 °C [33]. In barley caryopses, heat treatment at 0.5 h, 3 h and 6 h could induced the expression of the ferritin gene-corresponding probe Barley1_02716 [34]. In cotton leaves, the expression of the ferritin gene-corresponding probe Gra.2040.1.A1_s_at was induced in cultivar Sicala45 but not in cultivar Sicot53 after 42 °C treatment. We also analysed the expression profiles of the four Arabidopsis ferritin genes after heat stress in the expression database (http://jsp.weigelworld.org/expviz/expviz.jsp). After 38 °C treatment, AtFER1, AtFER3 and AtFER4 expression was induced gradually and peaked at 3 h. After recovery to normal conditions, the expression levels of these three genes gradually decreased to normal levels. AtFER2 accumulates in dry seed. AtFER2 abundance in vegetative organs is minimal, and its expression is not induced by heat. Taken together, we believe that induction of the plant ferritin gene by heat is a common phenomenon and that ferritin genes are involved in coping with heat stress.

We analysed the 2000-bp sequence of TaFER-5B upstream of the start codon and did not identify the typical heat stress responsive element (HSE) (Additional file 8: Figure S6). This result indicates that TaFER-5B expression is not regulated by heat transcription factors but by other pathways. We also analysed the promoter region of the four Arabidopsis ferritin genes. HSEs were identified in the promoter regions of AtFER2, AtFER3 and AtFER4 but not in AtFER1 (Additional file 8: Figure S6). These results indicate that heat transcription factors participate in the regulation of ferritin genes; however, other pathways are also involved because some ferritin genes are induced by heat even though their promoter regions do not have the typical HSE.

Under drought or other stress conditions, free iron in plants increases rapidly and induces the expression of ferritin to cope with the stress [19]. This phenomenon may be a regulatory mechanism to induce the expression of ferritin under heat-stress conditions. In addition, in the OsHDAC1 overexpression lines, ferritin gene expression is decreased [35]. AtFER1 and AtFER2 are the target genes of AtGCN5, and the expression levels of AtFER3 and AtFER4 are decreased in the mutant gcn5-1 [36]. These results indicate that histone modification may be involved in the regulation of the ferritin gene.

Some abiotic stress and hormone responsive elements were identified in the promoter sequence of TaFER-5B (Additional file 8: Figure S6). The expression of TaFER-5B was also induced by PEG, H2O2 and Fe-EDDHA treatment (Fig. 2b, c, d). We also analysed the expression profiles of the four ferritin genes under abiotic stress conditions using the Arabidopsis expression database (http://jsp.weigelworld.org/expviz/expviz.jsp). After cold treatment, only the expression of AtFER3 was induced. Under salt-stress conditions, the expression of AtFER1 and AtFER3 was increased 6-fold and 3-fold, respectively, but the expression of AtFER4 was not altered. Under drought-stress conditions, only the expression of AtFER1 and AtFER3 was induced. In rice, OsFER2 was induced by Cu, paraquat, SNP (a nitric oxide donor) and iron [37]. Ferritin is one of the genes up-regulated in response to drought in the SSH cDNA library of soybean nodules [16]. These results indicated that ferritin gene expression is induced by various abiotic stress treatments. Thus, the regulation of the ferritin gene is very complicated.

Ferritin plays an important role in the defence against heat and other abiotic stresses in plants

In this study, we demonstrated that TaFER-5B is induced by heat stress and other abiotic stresses. Overexpression of TaFER-5B in both wheat and Arabidopsis enhanced heat, drought, oxidative and excess iron stress tolerance compared with control plants. Transgenic tobacco plants ectopically expressing MsFer are more tolerant to oxidative damage and pathogens compared with WT plants [38]. Transgenic grapevine plants overexpressing MsFer were used to evaluate the tolerance to oxidative and salt stress [17]. What is the mechanism by which plant ferritin improves tolerance to abiotic stress? We evaluated the accumulation of O2− and H2O2 in transgenic plants and control under heat stress, which revealed that the transgenic plants accumulated less O2− and H2O2. High temperature induces the production of ROS and cause oxidative stress. We hypothesized that when a plant is under oxidative stress caused by high temperature, ferritin transforms toxic Fe2+ to the non-toxic chelate complex and protect cells against oxidative stress. When no additional ROS scavenging mechanisms are available, the function of ferritin is amplified and plays an important role.

Conclusions

Ferritins are conserved throughout the plant kingdom, and two genes per genome have been identified in all studied cereals. In this study, we cloned TaFER-5B from wheat and determined that TaFER-5B is induced by heat stress and other abiotic stresses. The relationship between TaFER-5B and abiotic stress tolerance was characterized. Our results suggest that TaFER-5B plays an important role in enhancing tolerance to heat stress and other abiotic stresses associated with the ROS scavenging.

Methods

Plant materials, growth conditions, and stress treatments

The common wheat genotype “TAM107” [39], which has a thermotolerant phenotype released by Texas A&M University in 1984, was used in this study. Seeds were surface-sterilized and soaked overnight in the dark at room temperature. The sprouted seeds were transferred to petri dishes with filter paper and cultured in water (25 seedlings per dish). The seedlings were grown in a growth chamber at a temperature, light cycle and humidity of 22 °C/18 °C (day/night), 12 h/12 h (light/dark), and 60%, respectively. Briefly, 10-day-old wheat seedlings were treated. Drought stress, oxidative stress and excess iron stress were applied by replacing water with PEG-6000 (20%), H2O2 (5 mM) or Fe-EDDHA (10 mM), respectively. For high-temperature treatments, seedlings were transferred to a growth chamber maintained at 40 °C. Untreated control seedlings were grown in the growth chamber under normal conditions. Leaves were collected from the seedlings at 1 h, 3 h, 6 h and 12 h after stress treatment, frozen immediately in liquid nitrogen and stored at -80 °C until RNA isolation and other analyses.

Arabidopsis thaliana ecotype Col-0 was used as WT. The T-DNA insertion lines fer1-1 (SALK_055487), fer2-1 (SALK_002947), fer3-1 (GABI-KAT_496A08) and fer4-1 (SALK_068629) were obtained from The Arabidopsis Information Resource (TAIR, http://arabidopsis.org) as described previously [19, 40]. fer1-3-4 and fer1-2-3-4 were generated as described in previous studies [19, 24]. Seeds were surface-sterilized and cold treated at 4 °C for 3 days in the dark, and then seedlings were grown at 22 °C on horizontal plates containing Murashige and Skoog (MS) medium (pH 5.8) solidified with 0.8% agar unless otherwise specified. Plants were grown at 22 °C under a 16 h/8 h (light/dark) photoperiod in the greenhouse.

Cloning of the TaFER gene and sequence analysis

Total RNA was extracted with TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen), and purified RNA was treated with DNase I. Subsequently, 2 μg of total RNA was reverse transcribed by M-MLV reverse transcriptase (Promega, USA). Based on the candidate probe sequence (Ta.681.1.S1_x_at), a pair of gene-specific primers was used to amplify TaFER. The primer sequences are listed in Additional file 9: Table S1 (1, 2).

Database searches of the nucleotide and deduced amino acid sequences were performed by NCBI/GenBank/Blast. Sequence alignment and similarity comparisons were performed using DNAMAN. Sequence alignments were performed by ClustalX, and the neighbour-joining tree was constructed using the MEGA5.1 program.

Expression pattern analysis of the TaFER-5B gene in wheat

Quantitative real-time PCR (RT-qPCR) was performed to determine the relative expression pattern of TaFER-5B with specific primers designed previously [13]. The 2-ΔΔC T method [41] was used to quantify the relative expression levels of TaFER-5B, and wheat β-actin was used as the endogenous control. Each experiment was independently repeated three times. Additional file 9: Table S1 (3, 4, 9, 10) lists the RT-qPCR primers.

Immunoblot analysis

Total protein extracts were prepared with sample buffer (250 mM Tris–HCl, pH 6.8, 10% SDS, 0.5% bromophenol blue, 50% glycerol and 5% β-mercaptoethanol). Protein concentration was measured with a Coomassie Brilliant Blue binding assay. Protein samples were separated by SDS-PAGE and blotted onto PVDF membranes for immunoblot analysis. Immunodetection of ferritin was performed using rabbit anti-FER polyclonal antibody (Agrisera).

Generation of transgenic wheat lines overexpressing TaFER-5B

The complete ORF of TaFER-5B driven by the maize ubiquitin promoter was inserted into vector pBract806. The resulting expression constructs were used for the production of TaFER-5B-overexpressing transgenic wheat lines.

Immature embryos from cultivar JM5265 were used for wheat transformation via the particle bombardment method. The presence of a TaFER-5B transgene in the transgenic lines was verified by PCR. Additional file 9: Table S1 (5, 6) lists the primers used for PCR.

Thermotolerance assay in wheat

Seeds of JM5265 obtained from Institute of Cereal and Oil Crops of the Hebei Academy of Agriculture and Forestry Sciences and transgenic lines were sown in pots containing potting soil and grown under the above-mentioned conditions. 5-day-old seedlings were directly exposed to 45 °C for 18 h, typically at 9 AM, in a lighted growth chamber and then shifted to 22 °C to the previous day/night cycle for recovery. The results were photographically documented after 5-d at 22 °C.

Transgenic Arabidopsis plant generation

The complete ORF of TaFER-5B was amplified with primers (Additional file 9: Table S1). The PCR product was digested with Xba I and Kpn I and cloned into the pCAMBIA1300 vector (driven by the CaMV 35S promoter). Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain GV3101 containing this binary construct was used to transform Arabidopsis plants. Transformants were selected on MS medium containing hygromycin (30 mg/L) and subject to PCR amplification.

Thermotolerance assay in Arabidopsis

Seeds of WT and transgenic lines were sown on a petri dish with approximately 33 mL of solid medium and grown under the above-mentioned conditions. The plated 7-day-old seedlings were directly exposed to 45 °C for 120 min, typically at 9 AM, in an illuminated growth chamber and then shifted to 22 °C to the previous day/night cycle for recovery. The results were photographically documented after 5 to 7 days at 22 °C. The survival rate was the ratio of surviving seedlings to total seedlings planted. Seedlings that were still green and producing new leaves were scored as surviving seedlings.

Ion leakage assay

Electrolyte leakage was measured as previously described [42]. Leaf segments of uniform maturity were cut into discs and washed three times with de-ionized water to eliminate external residues. Six discs were placed in test tube flasks with 20 mL of de-ionized water and incubated at 42 °C for 1 h. After incubation at room temperature for 24 h, the conductivity of the solution was read with a Horiba Twin Cond B-173 conductivity metre (HORIBA Ltd, Kyoto, Japan) and noted as T1. Then, the sample was boiled for 15 min to kill the tissues, followed by incubation at room temperature for 24 h. Then, the conductivity of this solution was recorded as T2. Ion permeability was measured as T1/T2. The experiment was independently repeated in triplicate.

Chlorophyll fluorescence measurement

The maximum efficiency of photosystem II (PSII) photochemistry, the Fv/Fm ratio, was measured using a pulse-modulated fluorometer (MINI-PAM, Heinz Walz, Effeltrich, Germany). Heat treatment was performed by transferring the plants to another growth chamber at 38 °C for 2 h. The Fv/Fm ratio was measured immediately after heat stress.

Determination of H2O2 content and antioxidant enzyme activities

Plants were harvested for assays of ROS accumulation and antioxidant enzyme activities. H2O2 content was determined following the protocol of the H2O2 Colorimetric Assay Kit (Beyotime). The activities of the antioxidant enzymes CAT and GR were determined using the CAT Assay Kit (S0051; Beyotime) and GR Assay Kit (S0055; Beyotime), respectively, according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Iron content measurement

Fe contents were analysed by inductively coupled plasma atomic absorption spectrometry (ICP-AAS). Samples were mineralized as described previously [19].

Acknowledgements

We thank Jianhe Yan (China agricultural university) for help in the measurement of iron content.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31571747) and National Key Project for Research on Transgenic (2016ZX08002-002).

Availability of data and materials

Data are available in a supplementary file, and materials are available from the authors upon request.

Authors’ contributions

QS and HP designed the research. XZ, XG, FW, ZL, LZ, YZ and XT performed research. XZ, XG, HP, ZN, YY, ZH and MX analyzed the data. XZ and HP wrote the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- ABA

Abscisic acid

- CAT

Catalase

- CS

Chinese spring

- DAB

Diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride

- Fe-EDDHA

Fe-ethylenediaminedi (o-hydroxyphenylacetic) acid

- Fv/Fm

The ratio of variable to maximal fluorescence

- GR

Glutathione reductase

- HSE

Heat stress responsive element

- ICP-AAS

Inductively coupled plasma atomic absorption spectrometry

- JM5265

Jimai5265

- MS

Murashige and Skoog

- NBT

Nitroblue tetrazolium

- O2−

Superoxide radical anions

- PCD

Programmed cell death

- PEG

Polyethylene glycol

- PSII

Photosystem II

- ROS

Reactive oxygen species

- RT-qPCR

Quantitative real-time PCR

- SSH

Suppression subtractive hybridisation

- WT

Wild type

Additional files

Coding sequence of TaFER-5B. (DOCX 15 kb)

Phylogenetic tree analysis of plant FERs from wheat, Arabidopsis, maize, rice and barley. TaFER-5A: accession number FJ225137; TaFER-5B: accession number FJ225141 and KX025176; TaFER-5D: accession number FJ225144; TaFER-4A: accession number TC373825; TaFER-4B: accession number FJ2251491; TaFER-4D: accession number FJ225146; AtFER1: accession number AED90364.1 (AT5G01600); AtFER2: accession number AEE74997.1 (AT3G11050); AtFER3: accession number AEE79476.1 (AT3G56090); AtFER4: accession number AEC09810.1 (AT2G40300); ZmFER1: accession number X83076.1; ZmFER2: accession number X83077.1; OsFER1: accession number AK059354.1; OsFER1: accession number AK102242.1; HvFER1: accession number EF440353; HvFER2: accession number AK251285. (JPG 55 kb)

Phylogenetic data of Additional file 2: Figure S1. (DOCX 16 kb)

TaFER-5B overexpression in wheat. (A) Confirmation of TaFER-5B insertion in JM5265 by PCR analysis of JM5265, PC, W-L1, W-L2 and W-L3 transgenic plants. PC: Ubi::TaFER-5B vector was used as the positive control. (B) Transcript levels of TaFER-5B as determined by RT-qPCR. β-actin was used as the internal control. The data are presented as the mean ± SD of three independent biological replicates. (C) TaFER-5B insertion into JM5265 as analysed by Western blot in JM5265, W-L1, W-L2 and W-L3 transgenic plants. (JPG 81 kb)

Genotyping of WT, fer1, fer2, fer3, fer4, fer1-3-4 and fer1-2-3-4. (JPG 232 kb)

Western blot analysis of the WT and transgenic lines. (A) Western blot of the WT and transgenic plants overexpressing TaFER-5B. (B) Western blot of the ferritin-lacking mutants, WT and the complemented lines A-CL1. Rubisco was used as the loading control. (JPG 127 kb)

Expression analysis of TaFER4 and TaFER5 homeologous genes in the RNA-seq expression database WheatExp (http://wheat.pw.usda.gov/WheatExp). (JPG 187 kb)

Cis-acting regulatory elements predicted in the promoters of TaFER-5B from IWGSC database and AtFER1-4. Distances shown in base pairs are relative to the start codon (+1). (JPG 174 kb)

Primers used in this paper. (DOCX 15 kb)

Contributor Information

Xinshan Zang, Email: dulzxs@163.com.

Xiaoli Geng, Email: czxiaoli@126.com.

Fei Wang, Email: wangfeihh@163.com.

Zhenshan Liu, Email: liuzhenshan@cau.edu.cn.

Liyuan Zhang, Email: zhangliyuan1226@163.com.

Yue Zhao, Email: zwb1013@126.com.

Xuejun Tian, Email: tianxuejun1@163.com.

Zhongfu Ni, Email: nizf@cau.edu.cn.

Yingyin Yao, Email: yingyin@cau.edu.cn.

Mingming Xin, Email: xmmlyac@126.com.

Zhaorong Hu, Email: hzr803@163.com.

Qixin Sun, Email: qxsun@cau.edu.cn.

Huiru Peng, Phone: 010-62731452, Email: penghuiru@cau.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Collins NC, Tardieu F, Tuberosa R. Quantitative trait loci and crop performance under abiotic stress: where do we stand? Plant Physiol. 2008;147:469–486. doi: 10.1104/pp.108.118117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lobell DB, Schlenker W, Costa-Roberts J. Climate trends and global crop production since 1980. Science. 2011;333:616–620. doi: 10.1126/science.1204531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wahid A, Gelani S, Ashraf M, Foolad MR. Heat tolerance in plants: An overview. Environ Exp Bot. 2007;61:199–223. doi: 10.1016/j.envexpbot.2007.05.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kotak S, Larkindale J, Lee U, von Koskull-Doring P, Vierling E, Scharf KD. Complexity of the heat stress response in plants. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2007;10:310–316. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2007.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mittler R, Finka A, Goloubinoff P. How do plants feel the heat? Trends Biochem Sci. 2012;37:118–125. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2011.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Qu AL, Ding YF, Jiang Q, Zhu C. Molecular mechanisms of the plant heat stress response. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2013;432:203–207. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2013.01.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sigel A, Sigel H. Metal ions in biological systems, volume 35: iron transport and storage microorganisms, plants, and animals. Met Based Drugs. 1998;5:262. doi: 10.1155/MBD.1998.262a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Theil EC. Ferritin: structure, gene regulation, and cellular function in animals, plants, and microorganisms. Annu Rev Biochem. 1987;56:289–315. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.56.070187.001445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Briat JF, Duc C, Ravet K, Gaymard F. Ferritins and iron storage in plants. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1800:806–814. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2009.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fobis-Loisy I, Loridon K, Lobreaux S, Lebrun M, Briat JF. Structure and differential expression of two maize ferritin genes in response to iron and abscisic acid. Eur J Biochem. 1995;231:609–619. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1995.tb20739.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zancani M, Peresson C, Biroccio A, Federici G, Urbani A, Murgia I, et al. Evidence for the presence of ferritin in plant mitochondria. Eur J Biochem. 2004;271:3657–3664. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.2004.04300.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tarantino D, Casagrande F, Soave C, Murgia I. Knocking out of the mitochondrial AtFer4 ferritin does not alter response of Arabidopsis plants to abiotic stresses. J Plant Physiol. 2010;167:453–460. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2009.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Borg S, Brinch-Pedersen H, Tauris B, Madsen LH, Darbani B, Noeparvar S, et al. Wheat ferritins: Improving the iron content of the wheat grain. J. Cereal Sci. 2012;56:204–213. doi: 10.1016/j.jcs.2012.03.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Qin D, Wu H, Peng H, Yao Y, Ni Z, Li Z, et al. Heat stress-responsive transcriptome analysis in heat susceptible and tolerant wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) by using Wheat Genome Array. BMC Genomics. 2008;9:432. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-9-432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Petit JM, Briat JF, Lobreaux S. Structure and differential expression of the four members of the Arabidopsis thaliana ferritin gene family. Biochem J. 2001;359:575–582. doi: 10.1042/bj3590575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Clement M, Lambert A, Herouart D, Boncompagni E. Identification of new up-regulated genes under drought stress in soybean nodules. Gene. 2008;426:15–22. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2008.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zok A, Oláh R, Hideg É, Horváth VG, Kós PB, Majer P, et al. Effect of Medicago sativa ferritin gene on stress tolerance in transgenic grapevine. Plant Cell Tiss. Org. Cult. (PCTOC) 2009;100:339–344. doi: 10.1007/s11240-009-9641-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dat J, Vandenabeele S, Vranova E, Van Montagu M, Inze D, Van Breusegem F. Dual action of the active oxygen species during plant stress responses. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2000;57:779–795. doi: 10.1007/s000180050041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ravet K, Touraine B, Boucherez J, Briat JF, Gaymard F, Cellier F. Ferritins control interaction between iron homeostasis and oxidative stress in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2009;57:400–412. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03698.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ragland M, Briat JF, Gagnon J, Laulhere JP, Massenet O, Theil EC. Evidence for conservation of ferritin sequences among plants and animals and for a transit peptide in soybean. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:18339–18344. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Masuda T, Goto F, Yoshihara T, Mikami B. Crystal structure of plant ferritin reveals a novel metal binding site that functions as a transit site for metal transfer in ferritin. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:4049–4059. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.059790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fu X, Deng J, Yang H, Masuda T, Goto F, Yoshihara T, et al. A novel EP-involved pathway for iron release from soya bean seed ferritin. Biochem J. 2010;427:313–321. doi: 10.1042/BJ20100015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marutani Y, Yamauchi Y, Kimura Y, Mizutani M, Sugimoto Y. Damage to photosystem II due to heat stress without light-driven electron flow: involvement of enhanced introduction of reducing power into thylakoid membranes. Planta. 2012;236:753–761. doi: 10.1007/s00425-012-1647-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ravet K, Touraine B, Kim SA, Cellier F, Thomine S, Guerinot ML, et al. Post-translational regulation of AtFER2 ferritin in response to intracellular iron trafficking during fruit development in Arabidopsis. Mol Plant. 2009;2:1095–1106. doi: 10.1093/mp/ssp041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jambunathan N. Determination and detection of reactive oxygen species (ROS), lipid peroxidation, and electrolyte leakage in plants. Methods Mol Biol. 2010;639:292–298. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60761-702-0_18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Drakakaki G, Christou P, Stoger E. Constitutive expression of soybean ferritin cDNA in transgenic wheat and rice results in increased iron levels in vegetative tissues but not in seeds. Transgenic Res. 2000;9:445–452. doi: 10.1023/A:1026534009483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ashraf M. Inducing drought tolerance in plants: recent advances. Biotechnol Adv. 2010;28:169–183. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2009.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.van Wuytswinkel O, Briat JF. Conformational changes and in vitro core-formation modifications induced by site-directed mutagenesis of the specific N-terminus of pea seed ferritin. Biochem J. 1995;305(Pt 3):959–965. doi: 10.1042/bj3050959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Masuda T, Morimoto S, Mikami B, Toyohara H. The extension peptide of plant ferritin from sea lettuce contributes to shell stability and surface hydrophobicity. Protein Sci. 2012;21:786–796. doi: 10.1002/pro.2061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yang H, Fu X, Li M, Leng X, Chen B, Zhao G. Protein association and dissociation regulated by extension peptide: a mode for iron control by phytoferritin in seeds. Plant Physiol. 2010;154:1481–1491. doi: 10.1104/pp.110.163063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lobreaux S, Yewdall SJ, Briat JF, Harrison PM. Amino-acid sequence and predicted three-dimensional structure of pea seed (Pisum sativum) ferritin. Biochem J. 1992;288(Pt 3):931–939. doi: 10.1042/bj2880931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu Z, Xin M, Qin J, Peng H, Ni Z, Yao Y, et al. Temporal transcriptome profiling reveals expression partitioning of homeologous genes contributing to heat and drought acclimation in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) BMC Plant Biol. 2015;15:152. doi: 10.1186/s12870-015-0511-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xi L, Xu K, Qiao Y, Qu S, Zhang Z, Dai W. Differential expression of ferritin genes in response to abiotic stresses and hormones in pear (Pyrus pyrifolia) Mol Biol Rep. 2011;38:4405–4413. doi: 10.1007/s11033-010-0568-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mangelsen E, Kilian J, Harter K, Jansson C, Wanke D, Sundberg E. Transcriptome analysis of high-temperature stress in developing barley caryopses: early stress responses and effects on storage compound biosynthesis. Mol Plant. 2011;4:97–115. doi: 10.1093/mp/ssq058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chung PJ, Kim YS, Jeong JS, Park SH, Nahm BH, Kim JK. The histone deacetylase OsHDAC1 epigenetically regulates the OsNAC6 gene that controls seedling root growth in rice. Plant J. 2009;59:764–776. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2009.03908.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Benhamed M, Martin-Magniette ML, Taconnat L, Bitton F, Servet C, De Clercq R, et al. Genome-scale Arabidopsis promoter array identifies targets of the histone acetyltransferase GCN5. Plant J. 2008;56:493–504. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03606.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stein RJ, Ricachenevsky FK, Fett JP. Differential regulation of the two rice ferritin genes (OsFER1 and OsFER2) Plant Sci. 2009;177:563–569. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2009.08.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Deak M, Horvath GV, Davletova S, Torok K, Sass L, Vass I, et al. Plants ectopically expressing the iron-binding protein, ferritin, are tolerant to oxidative damage and pathogens. Nat Biotechnol. 1999;17:192–196. doi: 10.1038/6198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Porter K, Worrall W, Gardenhire J, Gilmore E, McDaniel M, Tuleen N. Registration of ‘TAM 107’wheat. Crop Sci. 1987;27:9. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dellagi A, Rigault M, Segond D, Roux C, Kraepiel Y, Cellier F, et al. Siderophore-mediated upregulation of Arabidopsis ferritin expression in response to Erwinia chrysanthemi infection. Plant J. 2005;43:262–272. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2005.02451.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Camejo D, Rodriguez P, Morales MA, Dell'Amico JM, Torrecillas A, Alarcon JJ. High temperature effects on photosynthetic activity of two tomato cultivars with different heat susceptibility. J Plant Physiol. 2005;162:281–289. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2004.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available in a supplementary file, and materials are available from the authors upon request.