Abstract

Objectives

To determine to what extent racial and ethnic variation in Medicare spending during the last six months of life are explained by demographic, social support, socioeconomic, geographic, medical and EOL planning factors.

Design

Retrospective cohort study

Setting

Health and Retirement Study (HRS)

Participants

7,105 decedents who participated in the Health and Retirement Study between 1998–2012 and previously consented to survey linkage with Medicare claims.

Measurements

Total Medicare expenditures in the last 180 days of life by race and ethnicity, controlling for demographic factors, social supports, geography, illness burden, and EOL planning factors including presence of advance directives, discussion of EOL treatment preferences, and whether death had been expected.

Results

Our analysis included 5548 (78.1%) non-Hispanic white, 1030 (14.5%) non-Hispanic black, 331 (4.7%) Hispanic, and 196 (2.8%) adults of other race/ethnicity. Unadjusted results suggest that average Medicare expenditures for black decedents was $13,522 (35%, p <0.001) more than for whites, while Medicare expenditures for Hispanics was $16,341 (42%, p<0.001) more at EOL. Controlling for demographic, socioeconomic, geographic, medical and EOL specific factors, the Medicare expenditure difference between groups reduced to $8,047 (22%, p<0.001) more for black and $6,855 (19%, p<0.001) more for Hispanic decedents compared to non-Hispanic whites’ expenditures. The expenditure differences between groups remained statistically significant across all models.

Conclusion

Racial and ethnic differences in Medicare spending in the last six months of life are not fully explained by patient-level factors, including EOL planning factors. Future research should focus on broader systemic, organizational and provider level factors to explain these differences.

Keywords: end-of-life, disparities, Medicare, race and ethnicity

Introduction

An extensive body of evidence documents racial and ethnic differences in medical care at the end-of-life (EOL) (1–14). These include differences reported in intensity of care, reported patient preferences, and Medicare spending (2, 3, 7, 8, 15). Black decedents have been found to spend between 28% and 37% more than white decedents (5, 7, 14, 16–19).

Despite examining individual and geographic factors that contribute to overall costs, there remains unexplained variation among racial and ethnic groups at EOL. Partial explanatory mechanisms include differences in preferences for more expensive, life-prolonging care among non-white minorities, with both quantitative and qualitative evidence for such differences (5, 16). However, established work suggests that these EOL preferences are not necessarily concordant with care received (3).

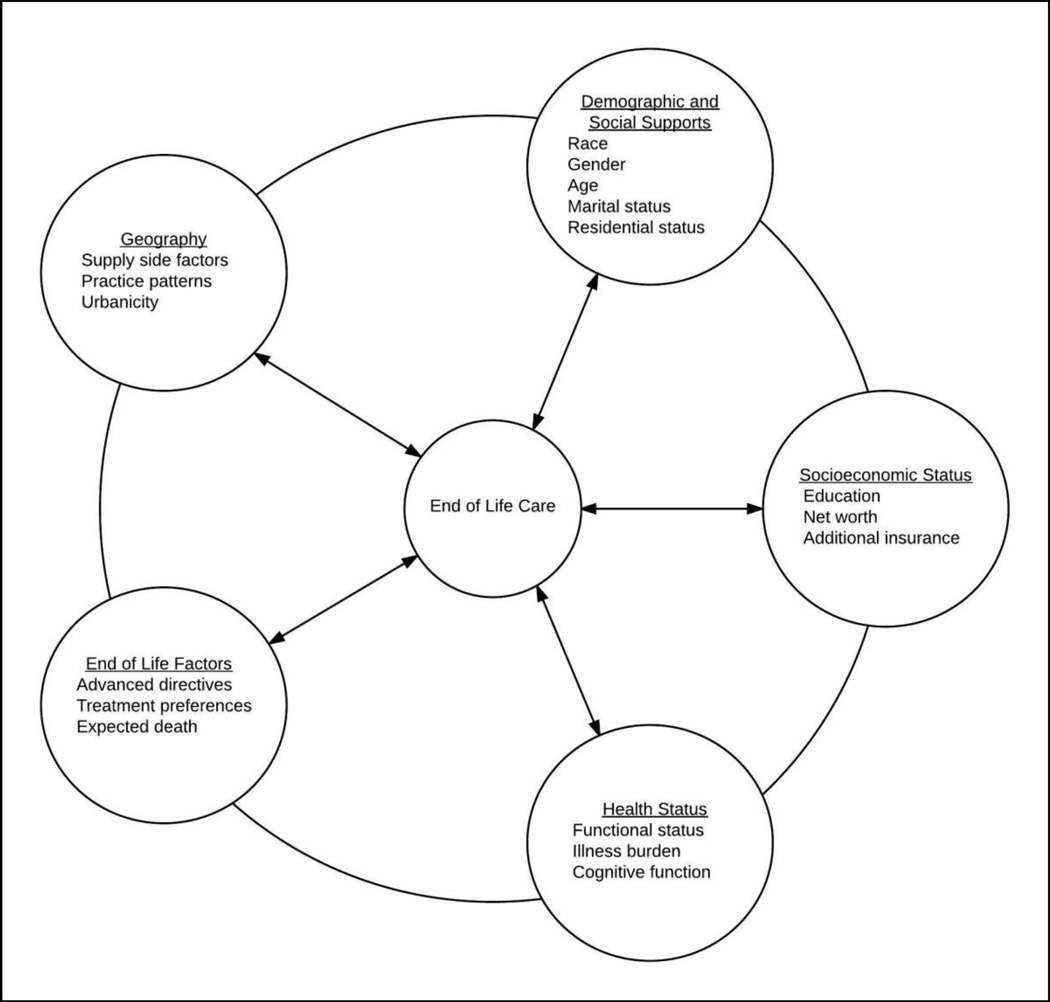

We sought to further understand elements that explain the association between race and EOL spending by examining a more complete array of patient level factors, including demographic, socioeconomic, geographic, medical and EOL planning variables. Guided by a modeling framework developed from prior research on mechanisms for racial health disparities (Figure 1) (5, 7, 19, 20), we used comprehensive data from the nationally representative Health and Retirement Study (HRS) to assess the extent to which racial and ethnic differences in EOL spending would be explained by these complex factors. By systematically examining multiple patient-level domains that have been associated with disparities in health care, we will better understand the causal pathways underlying the expenditure differences across racial and ethnic groups at the end of life. We hypothesized that the apparent racial and ethnic differences would be explained by these other factors not fully measured in past work.

Figure 1.

Modeling Framework for Factors Contributing to Differences in End-of-Life Care.

Methods

Study Population

We used data from the HRS, a biennial longitudinal survey of a nationally representative cohort of U.S. adults aged 51 or older that measures a broad range of scientific questions about health and aging (21). The HRS includes sufficient non-white minorities to examine racial and ethnic differences among older Americans. Telephone or in-person interviews with HRS participants are conducted every two years. During each interview cycle, HRS identifies participants who have died since the last core interview using information from family members and the National Death Index. Exit interviews are conducted with surviving family or friends who act as a proxy knowledgeable about the decedent.

We included HRS decedents aged 65 years or older who died between the 1998 and 2012 survey waves and who authorized that their HRS responses could be linked to Medicare claims data. We only included decedents who were continuously enrolled in Medicare Fee-For-Service parts A and B in the last six months of life in this analysis.

Measures

The primary outcome was total Medicare expenditures in the last six months of life. This measure includes all Medicare claims made for inpatient, outpatient, skilled nursing facility, durable medical equipment, home health care, physician supplier, and hospice care. All expenditures were adjusted for inflation (2012 U.S. dollars) using the medical component of the US Bureau of Labor Statistics Consumer Price Index.

We included demographic, social support, socioeconomic, geographic, and medical factors that have been shown in previous literature to be associated with Medicare expenditures in the last 6 months of life, as well as associated with differences in costs among racial and ethnic groups (Figure 1) (5, 7, 14, 19, 20, 22). Demographic and social support variables included self-reported race (non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, Hispanic, other), age at death, gender, marital status (married, never married, divorced, widowed, other), residential situation (lives at home alone, lives at home with others, lives in nursing home) and birth cohort (grouped years of birth by predefined generations from the HRS codebook). We included birth cohort as an independent variable in addition to age to control for generational specific associations with healthcare knowledge and preferences.

Socioeconomic variables included educational attainment (<12 years, 12 years, 13–15 years, ≥ 16 years), net worth by quartile, and non-Medicare insurance coverage (Medicaid, VA insurance, or Private insurance/Medigap). Geographic factors were included as urban residency determined by ZIP code, and using the End of Life Expenditure Index (EOL-EI) by quintile. Using the Dartmouth Atlas of Health Care, we linked each participant to a hospital referral region. The Dartmouth Atlas calculated End-of-Life Expenditure Index (EOL-EI), a measure of physician practice patterns based on utilization patterns among Medicare beneficiaries in the last six months of life for each hospital referral region. The EOL-EI takes into account regional variation and expenditure patterns that contribute to spending differences at EOL (23, 24).

We included 30 Elixhauser comorbidities as individual factor variables for each decedent to control for illness burden contributing to expenditure differences in the last six months of life (25). Using the HRS cognitive functioning measures collected at the decedent’s last survey interview, we included cognitive function variables. Cognitive function was categorized as normal, mild cognitive impairment, or dementia based on HRS validated definitions (26, 27). We also included functional status based on number of deficiencies in Activities of Daily Living (ADLs) collected during the last core interview. Functional status was categorized as no impairment (no ADL deficiencies), moderate impairment (1–3 ADL deficiencies) or severe impairment (4 or more ADL deficiencies).

End-of-life planning factors include presence of an advance directive, having discussed EOL treatment preferences prior to death, and having an “expected death.” Proxy informants were asked in the exit interview “Was the death expected at about the time it occurred or was it unexpected?” If the informant answered yes, the death was considered an “expected” death.

Data Analyses

We used multivariable generalized linear regression to model the extent to which association between race/ethnicity and EOL spending could be accounted for by all known factors. Because of the positively skewed distribution of Medicare expenditure data, the models used a gamma distribution with a log link (28). Model coefficients generated by the regression models were exponentiated to transform the data into rate ratios (RR). We constructed five multivariable models with total Medicare expenditures as the outcome variable, adding sequentially the clusters of variables hypothesized to contribute to racial and ethnic differences in EOL Medicare expenditures. The clusters were added to the bivariate model (1) with race and ethnicity in the following order: (2) demographic and social support variables, (3) socioeconomic and geographic indicators, (4) illness burden variables, (5) EOL planning variables. We tested for differential effects of all independent variables on total Medicare expenditures by calculating the marginal effects by race or ethnicity.

We imputed covariates for which any data were missing using multiple imputation (5 cycles) (29). Missing data values were most frequent among presence of an advance directive (11%), expecting death (9%), discussed EOL treatment preferences (8%), and having private or Medigap insurance (4%). There were no significant differences in results of multivariable analyses using imputed or non-imputed variables. We performed all analyses using STATA 13 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas).

Results

Our study sample included 7,105 Fee-for-Service Medicare beneficiaries aged 65 or older who died between the 1998 and 2012 survey waves and whose proxies responded to subsequent HRS exit surveys (72% of all Medicare–linked decedents). The characteristics of our study population are summarized in Table 1. The respondents included 5548 (78.1%) non-Hispanic whites, 1030 (14.5%) non-Hispanic blacks, 331 (4.7%) Hispanics, and 196 (2.8%) persons of other race/ethnicity. Mean total Medicare expenditures across the study population in the last 6 months of life, adjusted to 2012 U.S. dollars were $41,712 (range $0 to $754,124).

Table 1.

Decedent Characteristics by Race/Ethnicity

| Characteristic | Non-Hispanic white |

Black | Hispanic | Other Minority |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (7,105) | 5548 | 1030 | 331 | 196 |

| Mean age (SD) | 83.0 (8.47) | 81.2 (9.27) | 82.5 (9.11) | 79.5 (8.71) |

| Women, n (%) | 3016 (54.4) | 592 (57.5) | 174 (52.6) | 94 (48.0) |

| Marital Status, n (%) | ||||

| Married | 2477 (44.7) | 336 (32.7) | 143 (43.3) | 80 (41.0) |

| Never Married | 157 (2.83) | 45 (4.37) | 13 (3.94) | 10 (5.13) |

| Widowed | 2529 (45.6) | 515 (50.1) | 137 (41.5) | 84 (4301) |

| Separated/Divorced | 384 (6.92) | 133 (12.9) | 37 (11.2) | 21 (10.8) |

| Living situation, n (%) | ||||

| Lives alone | 1497 (27.0) | 273 (26.5) | 82 (24.8) | 50 (25.5) |

| Lives with others | 2989 (53.9) | 560 (54.4) | 204 (61.6) | 112 (57.1) |

| Lives in nursing home | 1062 (19.1) | 197 (19.1) | 45 (13.6) | 34 (17.4) |

| Educational attainment, n (%) | ||||

| <12y | 1963 (35.4) | 676 (65.6) | 260 (78.6) | 138 (70.4) |

| 12y | 1901 (34.3) | 204 (19.8) | 34 (10.3) | 26 (13.3) |

| 13–15y | 932 (16.8) | 81 (7.86) | 23 (6.95) | 15 (7.65) |

| >16y | 750 (13.5) | 69 (6.70) | 14 (4.23) | 17 (8.67) |

| Birth year cohort, n (%) | ||||

| AHEAD (<1923) | 3259 (58.7) | 544 (52.8) | 189 (57.1) | 80 (40.8) |

| CODA (1923–30) | 1181 (21.3) | 161 (15.6) | 59 (17.8) | 53 (27.0) |

| HRS (1931–41) | 1061 (19.1) | 307 (29.8) | 79 (23.9) | 57 (29.1) |

| War Baby (1942–47) | 47 (0.85) | 18 (1.75) | 4 (1.21) | 6 (3.06) |

| Net wealth median in 2012 USD (SD) |

141,796 (1,205,068) |

17,469 (189 637) |

16,610 (244,258) |

10,141 (544,775) |

| Urban residence, n (%) | 2116 (38.2) | 508 (49.4) | 137 (41.5) | 75 (38.5) |

| Additional Insurance coverage, n (%) | ||||

| Medicaid | 823 (15.1) | 388 (39.4) | 181 (55.9) | 85 (44.3) |

| Veterans Administration | 263 (4.78) | 34 (3.38) | 7 (2.12) | 8 (4.17) |

| MediGap (private) | 3524 (66.0) | 300 (30.4) | 59 (18.2) | 50 (26.2) |

| EOL_EIa quintile | ||||

| 1 | 800 (14.5) | 140 (13.7) | 14 (4.29) | 18 (9.18) |

| 2 | 1006 (18.2) | 200 (19.6) | 6 (1.84) | 19 (9.69) |

| 3 | 1327 (24.0) | 114 (11.2) | 39 (12.0) | 27 (13.8) |

| 4 | 974 (17.6) | 203 (19.9) | 54 (16.6) | 52 (26.5) |

| 5 | 1420 (25.7) | 362 (35.5) | 213 (65.3) | 80 (40.8) |

| Functional status (# of ADLb deficiencies) | ||||

| independent (0) | 2152 (38.9) | 338 (33.0) | 104 (31.6) | 73 (37.8) |

| mod impairment (1–3) | 1890 (34.2) | 335 (32.7) | 111 (33.7) | 61 (31.6) |

| severe impairment (>4) | 1489 (26.9) | 351 (34.3) | 114 (34.7) | 59 (30.6) |

| Chronic medical conditions | ||||

| CHF | 1666 (30.0) | 310 (30.1) | 105 (31.7) | 63 (32.1) |

| Chronic pulmonary disease | 1565 (28.2) | 243 (23.6) | 106 (32.0) | 66 (33.7) |

| Hypertension (complicated + uncomplicated) |

3594 (50.6) | 898 (12.6) | 273 (3.84) | 136 (1.91) |

| Diabetes (complicated + uncomplicated) |

1761 (24.8) | 517 (7.28) | 206 (2.90) | 99 (1.39) |

| Renal Failure | 662 (11.9) | 208 (20.2) | 62 (18.7) | 33 (16.8) |

| Liver disease | 150 (2.7) | 30 (2.91) | 15 (4.53) | 11 (5.61) |

| Lymphoma | 114 (2.05) | 14 (1.36) | 3 (0.91) | 2 (1.02) |

| Metastatic Cancer | 317 (5.71) | 58 (5.63) | 14 (4.23) | 8 (4.08) |

| Solid tumor | 951 (17.1) | 172 (16.7) | 45 (13.6) | 20 (10.2) |

| Depression | 729 (13.1) | 82 (7.96) | 49 (14.8) | 23 (11.7) |

| ≥2 comorbidities (CCIc) | 3195 (57.6) | 648 (62.9) | 213 (64.4) | 124 (63.3) |

| Cognitive Function | ||||

| Normal | 2270 (41.7) | 209 (20.9) | 80 (24.6) | 39 (20.3) |

| Mild cognitive impairment | 1465 (26.9) | 295 (29.5) | 86 (26.5) | 65 (33.9) |

| Severe cognitive impairment/dementia |

1706 (31.4) | 496 (49.6) | 159 (48.9) | 88 (45.8) |

| Median days in hospital (IQR) | 7 (0–16) | 11 (0–25) | 12 (0–25) | 10 (0–20) |

| Advanced Directive, n (%) | 3468 (71.9) | 332 (37.6) | 89 (31.2) | 74 (42.1) |

| Discussed Treatment Preferences | ||||

| yes | 2937 (58.7) | 373 (38.4) | 114 (37.5) | 95 (48.7) |

| no | 2016 (40.3) | 588 (60.6) | 186 (61.2) | 95 (48.7) |

| unsure | 47 (0.94) | 10 (1.03) | 4 (1.32) | 5 (2.56) |

| Died in Hospital, n (%) | 1605 (29.3) | 387 (38.7) | 129 (39.9) | 72 (36.9) |

| Any hospice use in last 6 months, n (%) | 2070 (37.3) | 258 (25.1) | 95 (28.7) | 57 (20.1) |

| Death expected? | ||||

| yes | 3150 (62.3) | 492 (52.5) | 181 (60.1) | 99 (53.5) |

| no | 1897 (37.5) | 441 (47.0) | 117 (38.9) | 84 (45.4) |

| unsure | 13 (0.26) | 5 (0.53) | 3 (1.00) | 2 (1.08) |

| Median time to deathd, mos (IQR) |

14.9 (7.61–22.2) |

14.4 (7.36–21.8) |

13.9 (6.77–22.3) |

15.2 (8.32–21.6) |

EOL-EI: End of Life Expenditure Index

Activities of Daily Living

Charlson Comorbidity Index

Number of months between last core interview and death

Table 2 reports rate ratio (RR) estimates provided by the sequential models to explain racial and ethnic differences in EOL expenditures. While controlling for previously hypothesized explanatory variables that contribute to differences in racial and ethnic spending at the EOL, the final model shows that despite controlling for all of these factors, there was still a significant difference in spending for non-Hispanic white, black, and Hispanic decedents.

Table 2.

Models Examining Explanatory Factors Contributing to Racial/Ethnic Differences in Medicare Spending in the Last 6 Months of Life

| Rate Ratios (95% CI) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1a | Model 2b | Model 3c | Model 4d | Model 5e | |

| Race/Ethnicity (ref = non- Hispanic white) |

|||||

| Black | 1.35 (1.26–1.44) |

1.31 (1.22–1.40) |

1.25 (1.16–1.34) |

1.20 (1.12–1.29) |

1.22 (1.13–1.31) |

| Hispanic | 1.42 (1.27–1.59) |

1.41 (1.26–1.58) |

1.27 (1.13–1.42) |

1.21 (1.08–1.36) |

1.19 (1.06–1.34) |

| Demographic & Social Supports | |||||

| female | 1.03 (0.98–1.08) |

1.02 (0.97–1.07) |

1.02 (0.96–1.07) |

1.00 (0.95–1.06) |

|

| age | 1.06 (1.00–1.12) |

1.06 (1.01–1.12) |

1.02 (0.97–1.07) |

1.02 (0.97–1.08) |

|

| Marital Status (ref = married) | |||||

| never married | 0.99 (0.86–1.14) |

0.96 (0.83–1.10) |

0.99 (0.86–1.14) |

0.99 (0.86–1.14) |

|

| widowed | 1.03 (0.96–1.10) |

1.02 (0.95–1.09) |

1.05 (0.98–1.12) |

1.05 (0.86–1.13) |

|

| divorced/separated | 1.02 (0.92–1.13) |

0.98 (0.89–1.09) |

0.98 (0.89–1.08) |

0.98 (0.89–1.08) |

|

| Residential status (ref = lives home alone) |

|||||

| Lives home with others | 1.08 (1.01–1.16) |

1.07 (1.00–1.14) |

1.09 (1.02–1.17) |

1.09 (1.02–1.17) |

|

| Lives in Nursing home | 0.83 (0.77–0.89) |

0.82 (0.76–0.88) |

0.89 (0.82–0.97) |

0.87 (0.81–0.95) |

|

| cohort (reference = AHEAD) | |||||

| CODA (1923–1930) | 0.96 (0.89–1.03) |

0.98 (0.92–1.06) |

0.94 (0.87–1.01) |

0.93 (0.87–1.00) |

|

| HRS (1931–1941) | 1.07 (0.97–1.19) |

1.13 (1.02–1.25) |

0.99 (0.89–1.09) |

0.99 (0.88–1.10) |

|

| War Baby (1942–1947) | 0.95 (0.73–1.23) |

1.06 (0.83–1.37) |

0.88 (0.68–1.13) |

0.88 (0.68–1.13) |

|

| Socioeconomic & Geographic Indicators | |||||

| Educational attainment (ref<12y) |

|||||

| 12y | 1.01 (0.96–1.07) |

0.99 (0.93–1.04) |

0.98 (0.92–1.04) |

||

| 13–15y | 0.96 (0.90–1.03) |

0.94 (0.87–1.01) |

0.94 (0.87–1.01) |

||

| 16+y | 1.04 (0.96–1.12) |

1.00 (0.93–1.09) |

0.99 (0.91–1.07) |

||

| Net worth (ref = 1st quartile) | |||||

| 2 | 0.98 (0.91–1.05) |

0.98 (0.92–1.06) |

0.99 (0.92–1.06) |

||

| 3 | 0.99 (0.92–1.07) |

1.02 (0.95–1.10) |

1.02 (0.95–1.10) |

||

| 4 | 1.01 (0.93–1.10) |

1.07 (0.98–1.16) |

1.07 (0.98–1.17) |

||

| Urban residence | 1.14 (1.07–1.20) |

1.12 (1.06–1.18) |

1.12 (1.06–1.19) |

||

| EOL Expenditure Index (ref = 1st quintile) |

|||||

| 2 | 1.19 (1.09–1.29) |

1.19 (1.10–1.30) |

1.19 (1.09–1.29) |

||

| 3 | 1.21 (1.12–1.31) |

1.19 (1.10–1.29) |

1.19 (1.09–1.28) |

||

| 4 | 1.25 (1.15–1.36) |

1.22 (1.12–1.32) |

1.23 (1.13–1.34) |

||

| 5 | 1.50 (1.38–1.63) |

1.43 (1.32–1.56) |

1.43 (1.32–1.56) |

||

| Additional Insurance | |||||

| Medicaid | 1.08 (1.01–1.16) |

1.03 (0.96–1.11) |

1.04 (0.97–1.12) |

||

| VA | 0.90 (0.81–1.01) |

0.84 (0.75–0.95) |

0.84 (0.75–0.94) |

||

| Medigap (private) | 1.07 (1.01–1.13) |

1.02 (0.97–1.08) |

1.02 (0.97–1.08) |

||

| Illness Burden | |||||

| Functional Status (ref = 0 ADL limitations) |

|||||

| moderate impairment | 1.02 (0.97–1.08) |

1.01 (0.96–1.07) |

|||

| severe impairment | 0.95 (0.89–1.02) |

0.94 (0.87–1.01) |

|||

| Elixhauser Comorbidities (30 indices) |

See appendix table | ||||

| Cognitive Function (ref = normal) |

|||||

| Mild Cognitive Impairment | 0.98 (0.93–1.04) |

0.98 (0.92–1.04) |

|||

| Dementia | 0.87 (0.81–0.93) |

0.86 (0.81–0.92) |

|||

| EOL Planning | |||||

| Discussed Preferences (ref = no) | |||||

| yes | 0.98 (0.92–1.04) |

||||

| unsure/don’t know | 1.08 (0.83–1.39) |

||||

| Had advance directive (ref=no) | |||||

| yes | 1.01 (0.95–1.06) |

||||

| unsure/don't know | 1.09 (0.73–1.56) |

||||

| Expected death (ref = no) | |||||

| yes | 1.24 (1.18–1.30) |

||||

Model 1: Unadjusted analysis

Model 2: Model 1 + demographic and social support variables (gender, age, marital status, residential status, birth cohort)

Model 3: Model 2 + socioeconomic and geographic variables (educational attainment, net worth by quartile, urban residence, EOL-EI by quintile, additional insurance –Medicaid, VA, private/Medigap)

Model 4: Model 3 + illness burden (Elixhauser comorbidities, functional status by deficiencies in Activities of Daily Living, cognitive function)

Model 5: Model 4 + End-of-life specific factors (discussed EOL treatment preferences, presence of advance directive, death was expected)

The unadjusted results of model (1) show that Medicare expenditures for black decedents was 35% more than for whites (RR 1.35, 95% CI 1.26–1.44) and Medicare expenditures for Hispanics was 42% more than for whites (RR 1.42, 95% CI 1.27–1.59). Model (2) accounted for demographic and social support by including model covariates for gender, age, marital status, residential status, and birth cohort. Only age and residential status had a statistically significant independent association with EOL Medicare expenditures. Living with others in the decedent’s home was associated with increased spending at the EOL (RR 1.08, 95%CI 1.01–1.16), while living in a nursing home was associated with decreased EOL Medicare spending (RR 0.83, 95% CI 0.77–0.89). Controlling for demographic covariates reduced the difference in expenditures to 31% (RR 1.31, 95% CI 1.22–1.40) for black decedents compared to whites, while expenditures for Hispanic decedents remained stable at 41% more than whites (RR 1.41, 95% CI 1.26–1.58).

Model (3) added socioeconomic and geographic indicators to the demographic and social support variables of model (2), which further reduced discrepancies in EOL Medicare expenditures. Included in this model were educational attainment, net worth (by quartile), urban residence, regional End of Life Expenditure Index (EOL-EI) by quintile, and additional insurance (Medicaid, VA insurance and private/Medigap were included). Of those, urban residence (RR 1.14, 95% CI 1.07–1.20), Medicaid (RR 1.08, 95% CI 1.01–1.16) and private/Medigap insurance (RR 1.07, 95% CI 1.01–1.13) were statistically significantly associated with increased EOL expenditures for all races/ethnicities. Each EOL-EI quintile contributed an increasing proportion of expenditures. Adjusting for both demographic, socioeconomic and geographic indicators in this model reduced the difference between both black/white EOL expenditures and Hispanic/white expenditures to 25% (RR 1.25, 95% CI 1.16–1.34) and 27% (RR 1.27, 95% CI 1.13–1.42), respectively.

Model (4) considered illness burden in addition to demographic, socioeconomic and geographic factors in evaluating expenditures. Factors included in this model were individual Elixhauser comorbidities, cognitive function, and functional status based on number of ADL limitations. Of the 30 Elixhauser comorbidities included in the model, only 11 of those had a statistically significant association with EOL Medicare expenditures (appendix table). Dementia was associated with a statistically significant reduction in EOL Medicare spending (RR 0.87, 95% CI 0.81–0.93). Model (4) further decreased the difference in EOL spending for blacks and Hispanics compared to non-Hispanic whites to 20% (RR1.20, 95% CI 1.12–1.29) and 21% (RR 1.21, 95% CI 1.08–1.31) respectively.

Finally, model (5) includes EOL planning factors. These variables include presence of an advance directive, discussion of EOL treatment preferences, and if death was expected. Having an expected death was associated with increased Medicare expenditures in the last six months of life. Neither the presences of an advance directive, nor discussion of treatment preferences for the final days of life were significantly associated with EOL Medicare expenditures. An expected death was associated with an increase in EOL expenditures by 24% (RR1.24, 95% CI 1.18–1.30) compared with those whose death was unexpected. Controlling for demographic, socioeconomic, geographic, medical, and end-of-life specific factors in this model shows expenditures for black decedents were 22% (RR1.22, 95% CI 1.13–1.31) higher and expenditures for Hispanic decedents were 19% (RR 1.19, 95% CI 1.06–1.33) higher than for non-Hispanic whites.

Figure 2 illustrates the mean differences in EOL expenditures by race for the unadjusted model (1) compared to the fully adjusted model (5). In unadjusted analyses, Medicare expenditures for black decedents was on average $13,522 more than for non-Hispanic whites, and Medicare expenditures for Hispanic decedents was $16,341 more. Accounting for all measured demographic, socioeconomic, geographic, medical, and EOL specific factors, Medicare expenditures for black decedents was on average $7,185 more than for non-Hispanic whites, while expenditures for Hispanic decedents was $6,164 more.

Figure 2.

Predicted Mean Medicare Expenditures in the Last 6 Months of Life by Race/Ethnicity

Model (1): Unadjusted analysis of race and total Medicare expenditures.

Model (5): Multivariable analysis including all demographic & social supports, socioeconomic factors, geographic factors, illness burden and end-of-life planning variables.

Discussion

In this national sample of decedents, significantly higher Medicare expenditures in non-Hispanic black and Hispanic decedents were not fully explained by an extensive array of patient characteristics. Tested variables included demographic and social supports, socioeconomic status, geography, medical, and EOL planning factors. As prior studies examining a more limited range of factors found, these variables did explain some of the variation in EOL spending between racial and ethnic groups (5, 8, 9, 12, 13, 30, 31). However, even in our fully adjusted models, approximately half of the variation remains unaccounted for.

Differences between racial and ethnic groups in Medicare spending in the last six months of life are frequently attributed to differences in patient preferences (2, 3, 5, 14, 30, 32). Qualitative survey work supports the conclusion that non-white patients are more likely to prefer life-sustaining treatments and prefer to die in the hospital compared to white patients (2, 3, 16, 32–37). However, inferring that unexplained variation in expenditures is due largely to these differences in preferences risks minimizing the extent to which other systemic or organizational factors contribute to this expenditure difference. Indeed, questions have been raised as to whether patient preferences—by any patient of any race—have any substantial effect on EOL care (7, 10, 13, 33, 38). Therefore, our analysis systematically examined several mechanisms that might contribute to racial and ethnic differences in EOL Medicare expenditures, including preferences. Our analysis suggests that EOL expenditure variation remains after controlling for many patient-oriented factors.

In this way, EOL expenditures are unlike many other health outcomes that have been evaluated for the effects of race and ethnicity. Prior studies have demonstrated that often what appears to be a race effect on health outcomes can actually be explained by other mechanisms, such as socioeconomic status, health literacy, clinical factors, hospital or neighborhood level effects, or insurance status (3, 4, 9, 11, 39–42). While our study included these factors, all of which somewhat attenuated the measured association with EOL Medicare expenditures between racial and ethnic groups, they failed to explain the total difference. This highlights how complexities surrounding care and decision-making at the EOL can be difficult to capture.

Our results suggest that factors which were not measured in our analysis—or in prior analyses—may be important to consider. Following our modeling framework, we were able to systematically eliminate several explanatory mechanisms for racial and ethnic variation in EOL Medicare expenditures. We suspect it is unlikely that the residual expenditure differentials are due solely to remaining patient-level factors, specifically preferences for life-prolonging treatment. Rather, we hypothesize that larger system-level or network-based factors are contributing to this unexplained difference. Important unexplored mechanisms potentially include interactions with the health care system, such as patient-family communication, patient-provider factors, and provider-provider interactions. As the literature in this area frequently focuses on patient level characteristics, insufficient attention has been paid to caregiver, provider, or health system contributions to EOL expenditures. Disagreements between family or other surrogates and patient preferences are well documented (32), yet little data exists as to how family or surrogate characteristics may be associated with EOL expenditures. Additionally, providers make assumptions based on presumed EOL preference differences by race, and thereby contribute to overall Medicare expenditures by providing unwanted life-sustaining care (8, 38, 43, 44). Further research is needed to understand if including family or caregiver and provider-level factors explains more of the variation in EOL expenditures between racial and ethnic groups. Much of the work in this domain has included evaluating additional patient level variables to understand EOL expenditure differences between racial and ethnic groups. There are many stakeholders involved at the EOL, and opportunities exist for these parties to exert influence in decisions for high cost care.

Our study has a number of potential limitations. Medicare expenditures do not account for all health care costs incurred by the decedent. Nursing home costs and expenditures covered by other insurance providers are not captured using these data and likely contribute significantly to total overall spending at the EOL. Out-of-Pocket costs for patients and families were also not included in this analysis and can be substantial at the EOL (45). Despite adjusting for hospital referral regions, facilities may vary within HRRs. We were not able to adjust for physician- or facility-level factors that may influence EOL care and utilization (46). The HRS lacks the sample size to study other racial and ethnic groups, therefore our analysis was limited to white, black and Hispanic decedents. By identifying decedents and looking retrospectively, our data are subject to selection bias because we cannot account for those who survived in the same cohort despite a high risk of death. Finally, data from proxy respondents in exit interviews were collected retrospectively and could be subject to recall bias.

Our study finds that both known and previously unexamined mechanisms do not fully explain racial and ethnic differences in EOL Medicare expenditures. Having individual respondent and proxy data over 14 years of survey collection provided a more detailed understanding of specific EOL planning factors that were unable to be examined on a national level in previous studies (5). However, much of the variation in expenditures remains unexplained. We suggest that future research should focus on broader systemic, organizational, or social-network factors that might underlie racial and ethnic differences in EOL spending. Such information is essential to developing policies and programs to understand and improve these factors that contribute to differences in care and spending at the end of life.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding Source: EB and JH were supported by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Clinical Scholars Program.

Sponsor’s Role: None

Footnotes

Prior Presentations: This work has been presented as a plenary presentation at the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Clinical Scholars National Meeting U November 2015, Seattle, WA.

Author Contributions:

EB contributed to study conceptualization and design, research, extraction and analysis of data, drafting of manuscript. TI contributed to conceptualization and design, analysis of data, drafting of manuscript. JH contributed to conceptualization and design, analysis of data and drafting of manuscript. KL contributed to study conceptualization and design, extraction of data and drafting of manuscript.

| Elements of Financial/Personal Conflicts |

*Author 1 EB |

Author 2 JAH |

Author 3 KML |

Etc. TJI |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | |

| Employment or Affiliation | x | x | x | x | ||||

| Grants/Funds | x | x | x | x | ||||

| Honoraria | x | x | x | x | ||||

| Speaker Forum | x | x | x | x | ||||

| Consultant | x | x | x | x | ||||

| Stocks | x | x | x | x | ||||

| Royalties | x | x | x | x | ||||

| Expert Testimony | x | x | x | x | ||||

| Board Member | x | x | x | x | ||||

| Patents | x | x | x | x | ||||

| Personal Relationship | x | x | x | x | ||||

References

- 1.Akinyemiju TF, Soliman AS, Johnson NJ, Altekruse SF, Welch K, Banerjee M, et al. Individual and neighborhood socioeconomic status and healthcare resources in relation to black-white breast cancer survival disparities. Journal of Cancer Epidemiology. 2013;2013 doi: 10.1155/2013/490472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barnato AE, Anthony DL, Skinner J, Gallagher PM, Fisher ES. Racial and Ethnic Differences in Preferences for End-of-Life Treatment. Journal of general internal medicine. 2009;24(6):695–701. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-0952-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Borum ML, Lynn J, Zhong Z. The effects of patient race on outcomes in seriously ill patients in SUPPORT: an overview of economic impact, medical intervention, and end-of-life decisions. Study to Understand Prognoses and Preferences for Outcomes and Risks of Treatments. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2000;48(5 Suppl):S194–S198. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb03132.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chan PS, Nichol G, Krumholz HM, Spertus Ja, Jones PG, Peterson ED, et al. Racial differences in survival after in-hospital cardiac arrest. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 2009;302(11):1195–1201. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hanchate A, Kronman AC, Young-Xu Y, Ash AS, Emanuel E. Racial and ethnic differences in end-of-life costs: why do minorities cost more than whites? Archives of internal medicine. 2009;169(5):493–501. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2008.616. Epub 2009/03/11. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2008.616. PubMed PMID: 19273780; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC3621787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hopp FP, Sonia AD. Racial Variations in End-of-Life Care. 2000:658–663. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb04724.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kelley AS, Ettner SL, Morrison RS, Du Q, Wenger NS, Sarkisian CA. Determinants of medical expenditures in the last 6 months of life. Ann Intern Med. 2011;154(4):235–242. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-154-4-201102150-00004. Epub 2011/02/16. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-154-4-201102150-00004. PubMed PMID: 21320939; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC4126809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Loggers ET, Maciejewski PK, Paulk E, DeSanto-Madeya S, Nilsson M, Viswanath K, et al. Racial differences in predictors of intensive end-of-life care in patients with advanced cancer. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2009;27(33):5559–5564. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.22.4733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Merchant RM, Becker LB, Yang F, Groeneveld PW. Hospital racial composition: A neglected factor in cardiac arrest survival disparities. American heart journal. 2011;161(4):705–711. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2011.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Muni S, Engelberg Ra, Treece PD, Dotolo D, Curtis JR. The influence of race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status on end-of-life care in the ICU. Chest. 2011;139(5):1025–1033. doi: 10.1378/chest.10-3011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Roseland ME, Pressler ME, E. Lamerato L, Krajenta R, Ruterbusch JJ, Booza JC, et al. Racial differences in breast cancer survival in a large urban integrated health system. Cancer. 2015 doi: 10.1002/cncr.29523. n/a-n/a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smith AK, Earle CC, McCarthy EP. Racial and ethnic differences in end-of-life care in fee-for-service medicare beneficiaries with advanced cancer. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2009;57(1):153–158. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.02081.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Welch LC, Teno JM, Mor V. End-of-life care in black and white: Race matters for medical care of dying patients and their families. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2005;53(7):1145–1153. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53357.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Johnson KS. Racial and ethnic disparities in palliative care. Journal of palliative medicine. 2013;16(11):1329–1334. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2013.9468. Epub 2013/10/01. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2013.9468. PubMed PMID: 24073685; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC3822363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kelley AS, Morrison RS, Wenger NS, Ettner SL, Sarkisian Ca. Determinants of treatment intensity for patients with serious illness: a new conceptual framework. Journal of palliative medicine. 2010;13(7):807–813. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2010.0007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barnato AE, Herndon MB, Anthony DL, Gallagher PM, Skinner JS, Bynum JPW, et al. Are regional variations in end-of-life care intensity explained by patient preferences?: A Study of the US Medicare Population. Medical care. 2007;45(5):386–393. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000255248.79308.41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hogan C, Lunney J, Gabel J, Lynn J. Medicare beneficiaries' costs of care in the last year of life. Health affairs. 2001;20(4):188–195. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.20.4.188. Epub 2001/07/21. PubMed PMID: 11463076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Karikari-Martin P, McCann JJ, Farran CJ, Hebert LE, Haffer SC, Phillips M. Race, Any Cancer, Income, or Cognitive Function: What Inf luences Hospice or Aggressive Services Use at the End of Life Among Community-Dwelling Medicare Beneficiaries? The American journal of hospice & palliative care. 2015 doi: 10.1177/1049909115574263. Epub 2015/03/11. doi: 10.1177/1049909115574263. PubMed PMID: 25753184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shugarman LR, Campbell DE, Bird CE, Gabel J, T AL, Lynn J. Differences in Medicare expenditures during the last 3 years of life. Journal of general internal medicine. 2004;19(2):127–135. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.30223.x. Epub 2004/03/11. PubMed PMID: 15009792; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC1492140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Heisler M, Faul JD, Hayward Ra, Langa KM, Blaum C, Weir D. Mechanisms for racial and ethnic disparities in glycemic control in middle-aged and older Americans in the health and retirement study. Archives of internal medicine. 2007;167(17):1853–1860. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.17.1853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Juster FT, Suzman R. An Overview of the Health and Retirement Study. The Journal of Human Resources. 1995;30:S7–S56. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zuckerman S, Waidmann T, Berenson R, Hadley J. Clarifying sources of geographic differences in Medicare spending. The New England journal of medicine. 2010;363(1):54–62. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0909253. Epub 2010/05/14. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0909253. PubMed PMID: 20463333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fisher ES, Wennberg DE, Stukel TA, Gottlieb DJ, Lucas FL, Pinder EL. The implications of regional variations in Medicare spending. Part 2: health outcomes and satisfaction with care. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138(4):288–298. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-138-4-200302180-00007. Epub 2003/02/15. PubMed PMID: 12585826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fisher ES, Wennberg DE, Stukel TA, Gottlieb DJ, Lucas FL, Pinder EL. The implications of regional variations in Medicare spending. Part 1: the content, quality, and accessibility of care. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138(4):273–287. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-138-4-200302180-00006. Epub 2003/02/15. PubMed PMID: 12585825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Elixhauser a, Steiner C, Harris DR, Coffey RM. Comorbidity measures for use with administrative data. Medical care. 1998;36(1):8–27. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199801000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ofstedal MBFG, Herzog AR. Documentation of Cognitive Functioning Measures in the Health and Retirement Study. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Crimmins EM, Kim JK, Langa KM, Weir DR. Assessment of cognition using surveys and neuropsychological assessment: the Health and Retirement Study and the Aging, Demographics, and Memory Study. The journals of gerontology Series B, Psychological sciences and social sciences. 2011;66(Suppl 1):i162–i171. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbr048. Epub 2011/07/16. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbr048. PubMed PMID: 21743047; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC3165454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Manning WG, Basu A, Mullahy J. Generalized modeling approaches to risk adjustment of skewed outcomes data. J Health Econ. 2005;24(3):465–488. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2004.09.011. Epub 2005/04/07. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2004.09.011. PubMed PMID: 15811539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schafer JL. Multiple imputation: a primer. Stat Methods Med Res. 1999;8(1):3–15. doi: 10.1177/096228029900800102. Epub 1999/05/29. PubMed PMID: 10347857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shugarman LR, Decker SL, Bercovitz A. Demographic and social characteristics and spending at the end of life. Journal of pain and symptom management. 2009;38(1):15–26. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2009.04.004. Epub 2009/07/21. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2009.04.004. PubMed PMID: 19615623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shugarman LR, Sorbero ME, Tian H, Jain AK, Ashwood JS. An exploration of urban and rural differences in lung cancer survival among medicare beneficiaries. American journal of public health. 2008;98(7):1280–1287. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.099416. Epub 2007/11/01. doi: 10.2105/ajph.2006.099416. PubMed PMID: 17971555; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC2424098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Phipps E, True G, Harris D, Chong U, Tester W, Chavin SI, et al. Approaching the end of life: attitudes, preferences, and behaviors of African-American and white patients and their family caregivers. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21(3):549–554. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.12.080. Epub 2003/02/01. PubMed PMID: 12560448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.A controlled trial to improve care for seriously ill hospitalized patients. The study to understand prognoses and preferences for outcomes and risks of treatments (SUPPORT). The SUPPORT Principal Investigators. JAMA. 1995;274(20):1591–1598. Epub 1995/11/22. PubMed PMID: 7474243. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Garrido MM, Harrington ST, Prigerson HG. End-of-life treatment preferences: A key to reducing ethnic/racial disparities in advance care planning? Cancer. 2014:3981–3986. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Blackhall LJ, Frank G, Murphy ST, Michel V, Palmer JM, Azen SP. Ethnicity and attitudes towards life sustaining technology. Social science & medicine. 1999;48(12):1779–1789. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00077-5. Epub 1999/07/15. PubMed PMID: 10405016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kagawa-Singer M, Blackhall LJ. Negotiating cross-cultural issues at the end of life: "You got to go where he lives". JAMA. 2001;286(23):2993–3001. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.23.2993. Epub 2001/12/26. PubMed PMID: 11743841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kwak J, Haley WE. Current research findings on end-of-life decision making among racially or ethnically diverse groups. Gerontologist. 2005;45(5):634–641. doi: 10.1093/geront/45.5.634. Epub 2005/10/04. PubMed PMID: 16199398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mack JW, Paulk ME, Viswanath K, Prigerson HG. Racial disparities in the outcomes of communication on medical care received near death. Archives of internal medicine. 2010;170(17):1533–1540. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.322. Epub 2010/09/30. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.322. PubMed PMID: 20876403; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC3739279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cooke CR, Nallamothu B, Kahn JM, Birkmeyer JD, Iwashyna TJ. Race and timeliness of transfer for revascularization in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Med Care. 2011;49(7):662–667. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31821d98b2. Epub 2011/06/17. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31821d98b2. PubMed PMID: 21677592; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC3905793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.LaVeist Ta, Thorpe RJ, Galarraga JE, Bower KM, Gary-Webb TL. Environmental and socio-economic factors as contributors to racial disparities in diabetes prevalence. Journal of general internal medicine. 2009;24(10):1144–1148. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-1085-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Volandes AE, Paasche-Orlow M, Gillick MR, Cook EF, Shaykevich S, Abbo ED, et al. Health literacy not race predicts end-of-life care preferences. Journal of palliative medicine. 2008;11(5):754–762. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2007.0224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Johnson KS, Kuchibhatla M, Payne R, Tulsky JA. Race and residence: intercounty variation in black-white differences in hospice use. Journal of pain and symptom management. 2013;46(5):681–690. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2012.12.006. Epub 2013/03/26. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2012.12.006. PubMed PMID: 23522516; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC3735723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.LoPresti Ma, Dement F, Gold HT. End-of-Life Care for People With Cancer From Ethnic Minority Groups: A Systematic Review. American Journal of Hospice and Palliative Medicine. 2014 doi: 10.1177/1049909114565658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wallace MP, Weiner JS, Pekmezaris R, Almendral A, Cosiquien R, Auerbach C, et al. Physician cultural sensitivity in African American advance care planning: a pilot study. Journal of palliative medicine. 2007;10(3):721–727. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2006.0212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kelley AS, McGarry K, Gorges R, Skinner JS. The Burden of Health Care Costs for Patients With Dementia in the Last 5 Years of Life. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163(10):729–736. doi: 10.7326/M15-0381. Epub 2015/10/27. doi: 10.7326/m15-0381. PubMed PMID: 26502320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Obermeyer Z, Powers BW, Makar M, Keating NL, Cutler DM. Physician Characteristics Strongly Predict Patient Enrollment In Hospice. Health affairs. 2015;34(6):993–1000. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2014.1055. Epub 2015/06/10. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2014.1055. PubMed PMID: 26056205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.