Abstract

Arachidonic acid (ARA) is one of the most abundant polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) in the mammalian brain. Many enzymatically- and nonenzymatically-produced metabolic products have important and potent pharmacological properties. However, uniformly isotope labeled forms of ARA are not commercially available for studying the metabolic fates of ARA. This study describes a simple and efficient protocol for the biosynthesis of U-13C-ARA from U-13C-glucose, and U-14C-ARA from U-14C-glucose by Mortierella alpina. The protocols yield approximately 100 nmol quantities of U-13C-ARA with an isotopic purity of 95 % from a 500 μl batch volume, and approximately 2 μCi quantities of U-14C-ARA with an apparent specific activity in excess of 1200 Ci/mole from a 250 μl batch volume.

Keywords: Mortierella alpina, arachidonic acid, carbon isotope labeling, micro-scale culture

1. Introduction

The production of arachidonic acid (ARA, 20:4ω6), a polyunsaturated fatty acid (PUFA), from M. alpina is an important industrial scale process that has been extensively studied and optimized (Shinmen et al., 1989; Bajpai et al., 1991; Dyal and Narine, 2005; Zhu et al., 2006; You et al., 2011; Ji et al., 2014a; Ji et al., 2014b; Li et al., 2015a; Li et al., 2015b). ARA is an “essential” dietary PUFA for terrestrial metazoans, who rely on single-cell oceanic organisms such as M. alpina as their ultimate source of PUFAs.

ARA is a biochemical precursor for enzyme-mediated synthesis of diverse eicosanoids, many of which have potent hormonal and signaling functions. It is also the source of chemically-reactive oxidative degradation products such as 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal and 4-oxo-2-nonenal when subjected to chemically-mediated (i.e. non enzymatically-mediated) oxidative damage (Esterbauer et al., 1986; Schneider et al., 2001). Other products of chemically-mediated oxidative damage such as isoprostanes are relatively inert and are used as biomarkers of oxidative stress (Morrow et al., 1992; Marrow et al., 1994; Morrow et al., 1994).

Given the importance and diversity of ARA-derived biomolecules, especially in the brain where ARA is concentrated, isotope-labeled forms of ARA would be valuable for measuring turnover, for studying the metabolic fate of oxidation products, and for use as internal standards when quantifying these products by mass spectrometry. The biosynthetic production of 13C-labeled ARA has been described previously, but an isotopic purity of only ~20% was achieved (Kawashima et al., 1995). The biosynthesis of a partially 13C-labeled forms of the closely related PUFA, docosahexaenoic acid (DHA, 22:6ω3) has also been described (de Swaaf et al., 2003). However, for use as an internal standard for mass spectrometry, and to prepare 13C-labeled derivatives, uniformly labeled forms of ARA are required.

A deuterated form of ARA is commercially available (d8-ARA, Cayman Chemical Company, Ann Arbor, MI, USA), and commonly used for mass spectrometric quantitation of ARA. However, the deuterium atoms are frequently lost during both chemical oxidation and enzymatic metabolism. Moreover, they are labile during saponification procedures. There are no 13C-labeled forms of ARA commercially available at the time of this writing. A 14C-labeled form with a single radiolabel in position 1 is available (Perkin-Elmer Inc., Wellesley, MA, USA), although labels in this position do not become part of some critically important degradation products (such as hydroxynonenal) that are derived from the distal carbon atoms (Schneider et al., 2001).

Therefore, procedures for the laboratory-scale preparation of ARA with a uniform distribution of carbon isotopes are of interest. This work describes the biosynthesis of U-13C-ARA and U-14C-ARA from isotope-labeled glucose on a laboratory scale, and with a level of purity that is suitable for in vivo use.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

D-[U-13C]glucose (99% atom 13C) was purchased from Cambridge Isotope Laboratories (Andover, MA, USA). D-[U-14C]glucose (300–360 Ci/mol, 1mCi/mL) was purchased from American Radiolabeled Chemicals (Saint Louis, MO, USA). Unlabeled ARA was purchased from Nu-Check Prep Inc. (Elysian, MN). d8-ARA was purchased from Cayman Chemical Company (Ann Arbor, MI). All other chemicals were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Mortierella alpina (ATCC 32222) was purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA, USA). Glassware and pipette tips were sterilized by autoclave. All manipulations were performed in a biosafety hood using sterile technique.

2.2. Media

Media salt concentrations were adapted from Zhu et al. Seven stock solutions were prepared and mixed to yield the media indicated in Table 1. Solution A was 2gm of K2HPO4, 1gm of MgSO4•7H2O, and 1 gm KCl in 1000 ml water. Solution B1 was 2 gm of Na2NO3 in 50 ml water. Solution B2 was 0.25 gm of Na2NO3 in 50 ml water. Solution C1 was 20 gm of ordinary D-glucose in 100 ml water. Solution C2 was 2 gm of U-13C-glucose in 100 ml water. Solution D was 25 gm of CaCl2 in 50 ml water. Solution E was 50 mg of FeCl3, 1 gm of H3BO3, 150 mg of MnCl2•4H2O, 10 mg of ZnCl2, and 5 mg of CoCl2•H2O in 100 ml water. All water was Millipore analytical grade. The pH of stock solutions A, C1, and C2 was adjusted to 7.0 with 1M NaOH or 1M HCl as needed. Stock solution E was sterilized by filtration through 0.22 μm Milex® syringe filters. All stock solutions were stored in the dark at 4°C. M. alpina stocks were kept in maintenance media (table 1) at ambient temperature and light. Inoculating suspensions were prepared by adding sterile glass beads to a 7-day-old culture and vortexing for 1–2 min to pulverize the mycelial mass. Subcultures were made by adding 200 μl of the inoculating suspension to 5 mL of maintenance media.

Table 1.

Media compositions

| Stock Solution | Maintenance | 5 gm/L 13C-glucose | 0.1 gm/L 12C-glucose | 0.1 gm/L 13C-glucose | 0.1 gm/L 14C-glucose |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 500 ml | 5 ml | 5 ml | 5 ml | 5 ml |

| B1 | 16 ml | 160 μl | – | – | – |

| B2 | – | – | 32 μl | 32 μl | 32 μl |

| C1 | 250 ml | 2.5 ml | 50 μl | – | – |

| C2 | – | – | – | 50 μl | – |

| U-14C-glucose | – | – | – | – | 2 mCi |

| D | 5 ml | 50 μl | 50 μl | 50 μl | 50 μl |

| E | 1 ml | 10 μl | 10 μl | 10 μl | 10 μl |

| Final Volume | 1000 ml | 10 ml | 10 ml | 10 ml | 10 ml |

| Key Concentrations | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glucose (mM) | 28 | 28 | 0.55 | 0.55 | 0.55 | |

|

|

9.5 | 9.5 | 0.19 | 0.19 | 0.19 | |

| C:N ratio | 17.7 | 17.7 | 17.4 | 17.4 | 17.4 | |

2.3. Glucose consumption and growth rates

Glucose concentrations in various media were measured after centrifugation for 15 min at 1600 × g with the DNS method (Miller, 1959). The DNS reagent consisted of 0.5 gm 3,5-dinitrosalicylic acid, 0.05 gm Na2SO3, and 0.5 gm NaOH in 50 ml of water. An equal volume of DNS reagent (300 μl) was mixed with an equal volume of the solution to be assayed (typically 300 μl) and incubated at 90 °C for 10 min. Following the incubation, 600 μl of quencher was added (2 gm of sodium potassium tartrate, NaKC4H4O6•4H2O in 50 ml water) and samples were cooled to room temperature. The absorbance at 540 nm was recorded and compared to a standard curve to determine concentrations. A concentration of 0.8 g/L in the medium typically yielded an absorbance of 1.10 AU at 540 nm, and the absorbance was proportional to concentration down to 0.2 g/L. Cultures starting with 5 g/L glucose were diluted 6× before the assay.

To measure growth rates, cultures were centrifuged for 15 minutes at 1600 × g, and the supernatant was discarded. The pellet was re-suspended in 1 or 2 mL of deionized water for cultures with initial volumes of 250 μl or 500 μl, respectively. Intact cells were evenly suspended by adding sterile glass beads to the solution and vortexing for 2 min to pulverize the mycelial mass. OD600 was measured on a Cary 400 Bio UV-vis spectrophotometer (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA) in lieu of cell dry weights so that growth could be monitored while the organisms were growing, and to avoid drying of the organisms which complicates PUFA extraction.

2.4. Lipid extraction and saponification

Lipid extractions were performed with the Bligh-Dyer (BD) method (Bligh and Dyer, 1959) modified by substituting dicholoromethane for chloroform. Fungal cultures in 13×100 mm glass tubes were centrifuged for 15 min at 1600 × g, the supernatant was removed, and the mycelial mass was resuspended in 640 μL of water. This suspension was subjected to 3 freeze-thaw cycles (liquid nitrogen alternating with boiling water). 1600 μL of methanol and 800 μL of dichloromethane were then added and the mixture was tip-sonicated for 90 sec on ice with a model F60 sonic dismembrator (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA). 800 μL of dichloromethane and 640 μL of water were then added to create separate phases, which were clarified by centrifugation at 110 × g for one minute. The lower (dichloromethane) phase (~1.6 mL) was withdrawn, transferred to a new 13×100 mm glass tube, dried under argon, and saponified in 85% methanol in water with 0.5 M NaOH (2 mL final volume) at 85°C for 1 hour. Following saponification, samples were cooled to room temperature, acidified with 400 μL of 5M HCl, and extracted with 1 mL of isooctane three times. The three upper (isooctane) phases were combined in a Teflon tube, and evaporated under Argon gas. The dried residue was dissolved in 100 μL of ethanol and stored under argon at −80°C.

2.5. HPLC separation and mass spectrometry parameters

HPLC separations were performed with a 4.6 × 150 mm XDB-C18 column (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA) and a mobile phase pumped at 0.50 mL/min. Solvent A was 60% acetonitrile and 40% H2O by volume, with 0.1% formic acid added; solvent B was 100% acetonitrile to which 0.1% formic acid was added. The gradient program was 40% B (0–10 min), 40–100% B (10–40 min), and 100% B (40–50 min), before returning to 40% B.

Non-radioactive extracts were analyzed on an ABI 4000 mass spectrometer (Sciex, Toronto, Canada) operating in negative ion multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) or Q1 mode. The MRM transitions monitored were m/z 303→259 for 12C-ARA with the neutral loss of CO2, 323→279 for U-13C-ARA, and 311→267 for d8-ARA.

NH4OH (0.15 M) in 1:1 methanol: water at 100 μL/min was introduced into the post-column effluent via tee junction prior to the MS analysis to deprotonate the fatty acids. The DP was −75 V for both modes; the CAD was 7 psi and the CE was −20 V for MRM.

Both radioactive and non-radioactive extracts were collected in 30 second fractions. A small portion of each radioactive fraction was analyzed by scintillation counter to verify the location of peaks. The fractions corresponding to the elution time for ARA were collected, dried in a Teflon tube, reconstituted in ethanol, purged with Argon gas, and stored at −80°C.

2.6. Calculations

2.6.1. Isotopic Purity

ARA purified from fungal extracts eluted as a single peak with an m/z of 303 to 323, depending on the number of 13C atoms in the molecule. The isotopic purity (Piso) of 13C-labeled ARA was calculated using Equation 1, where fi is the integrated area of the peak at m/z = i.

| Equation 1 |

2.6.2. Conversion Efficiency

A sample of d8-ARA was calibrated with known concentrations of unlabeled ARA by MRM mass spectrometry, and aliquots were added to extracts to quantify the 13C-ARA recovered from each culture. For extracts of cultures grown in 13C-glucose, the efficiency of 13C conversion into ARA (i.e. the conversion efficiency) is given by

| Equation 2 |

2.6.3. Specific Activity

14C-ARA purified from fungal extracts was quantified by scintillation counting. To estimate the mass of the radiolabeled material, U-13C-ARA was produced under the same conditions and quantified by MRM mass spectrometry. The specific activity of 14C-ARA was then estimated using Equation 3, where A is the total activity of 14C-ARA.

| Equation 3 |

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. 13C-ARA production

M. alpina did not grow, consume glucose, or yield 13C-labeled ARA when cultivated in U-13C-glucose without nitrogen (data not shown). ARA yield has been reported to be optimal when the C/N ratio in the media is between 15–20 (Koike et al., 2001). Therefore, the media used in these experiments was made with a C/N ratio of 17.5.

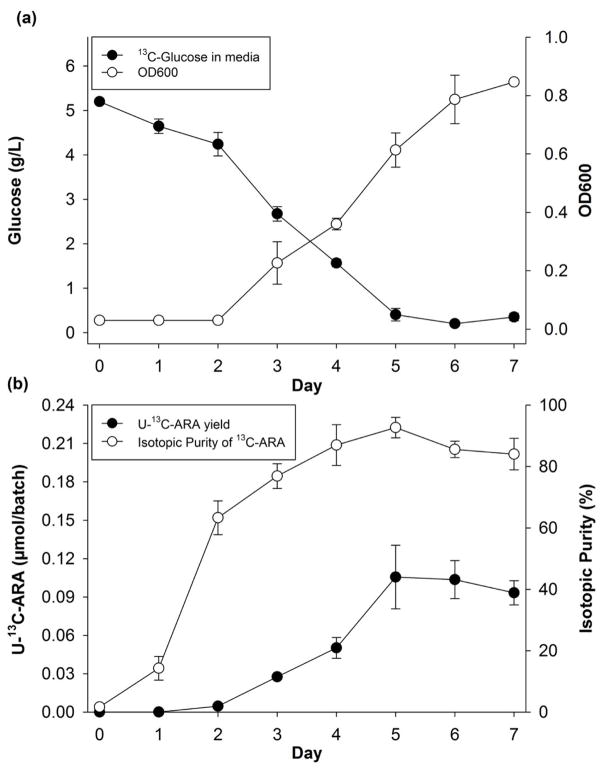

In 500 μl batches of media containing 5 gm/L U-13C-glucose, glucose concentration declined almost linearly, reaching a minimum after 5 days (Fig. 1a). Fungal growth was first detected by OD600 on day 3, and continued almost linearly through day 7. The U-13C-ARA yield was measured by MRM mass spectrometry after adding a calibrated aliquot of d8-ARA to the final purified fraction. The yield reached a maximum on day 5 (Fig. 1b). The colony was a single white mass composed of mycelia with visible oil droplets.

Fig. 1.

Production in 5 gm/L 13C-glucose media. Averages of three separate batches ± standard deviations, (a) glucose consumption and growth curve, (b) U-13C-ARA yield and % 13C labels in all of recovered isotopes.

Isotopic purity also reached a maximum of 95% on day 5, and then declined slightly. Extracted U-13C-ARA eluted between 25.0 and 26.5 minutes and a Q1 mass spectrum of this peak revealed quantifiable signals at m/z ratios ranging from 319–323, corresponding to ARA with 16–20 13C labels. U-12C-ARA (m/z=303) was not detected. Isotopically pure 13C-ARA (U-13C-ARA, m/z=323) constituted 38% of the purified material. From three separate cultures, each containing 14 μmol of U-13C-glucose, an average of 110 ± 20 nmol of U-13C-ARA was recovered for a conversion efficiency of 2.8 ± 0.6% (Equation 2).

The isotopic purity of U-13C-ARA is important because the most sensitive approach to mass spectrometric quantitation (MRM), relies on complete isotope substitution in both parent ion and collision-induced fragments. The production of U-13C-ARA from U-13C-glucose has been reported previously (Kawashima et al., 1995). The yields in that work were higher than reported herein (14 % vs 2.8 % in this work). However, the isotopic purity that material was lower (78–83%), and the yield was estimated for the transesterified methyl ester. Yields would have probably been lower if the saponified product had been assayed.

Isotopic purity was maximized in the current experiments by omitting various 12C sources in the growth media, such as yeast extract, and substituting an inorganic source of nitrogen. The stated isotopic purity of the commercially-prepared U-13C-glucose was 99%, although our measurements and calculations according to Equation 1 indicated it to be 97% (data not shown). Ultimately, the isotopic purity of recovered ARA was 95%.

3.2. 14C-ARA production

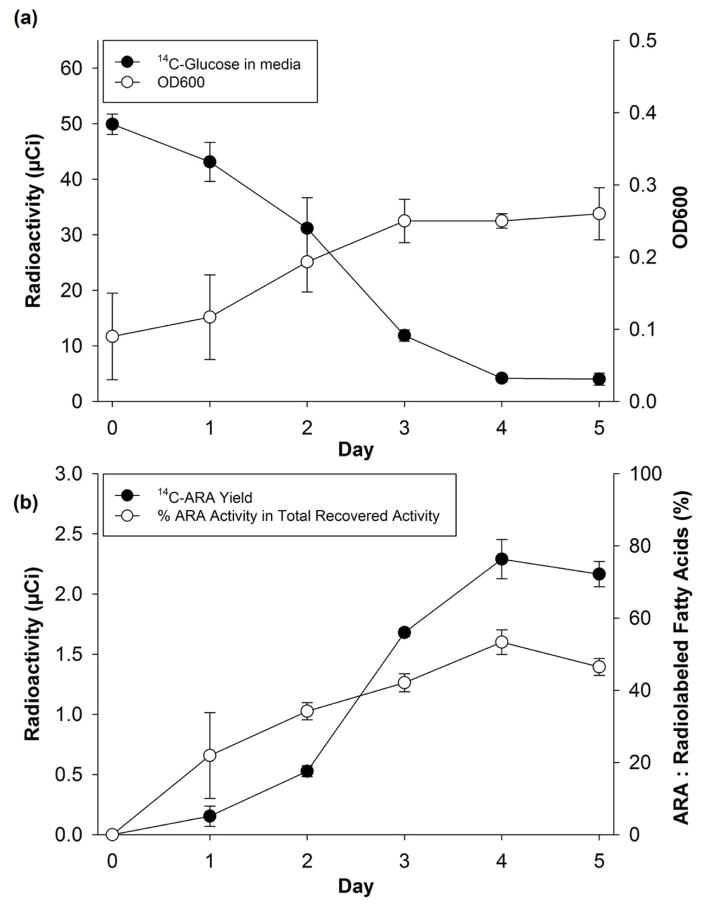

U-14C-glucose is supplied with a maximum specific activity of 360 Ci/mole, and purchased in lots of 5 mCi. Therefore, one lot of U-14C-glucose, diluted into 25 ml of media, yielded sufficient complete media for 100 batches of 250 μl, each containing 50 μCi of 14C-glucose and a maximum glucose concentration of 0.1 gm/L.

In this media, 14C activity remaining in the supernatant after centrifugation declined almost linearly, reaching a minimum of 4.2 ± 0.5 μCi on day 4 (Fig. 2a), suggesting slightly faster glucose consumption than in the 5 gm/L cultures described above. OD600 estimates of fungal growth increased almost linearly for 3 days, reaching an apparent plateau between 3–5 days. 14C activity recovered as ARA reached a maximum of 2.3 ± 0.2 μCi per batch on day 4 (Fig. 2b), for a conversion efficiency of 4.6 ± 0.4 %. It is not surprising that the conversion efficiency in these experiments with 0.1 gm/L glucose in the media is higher than the efficiency in experiments with 5 gm/L glucose, given prior reports about efficiency and yield in the literature (Bajpai et al., 1991), although the concentrations of other media components also differed in our experiments.

Fig. 2.

Production in 0.1 gm/L 14C-glucose media. Averages of three separate batches ± standard deviations, (a) glucose consumption and growth curves, (b) 14C activity in ARA and % 14C Activity ARA activity in total recovered activity.

To estimate the isotopic purity and specific activity of the radiolabeled material when its mass could not be measured, U-13C-ARA was produced under the same conditions (i.e. after 4 days in media containing 0.1 gm/L U-13C-glucose) and examined by Q1 and MRM mass spectrometry after adding a calibrated aliquot of d8-ARA. The Q1 scan revealed that the ARA contained 16–20 atoms of 13C (m/z = 319–323) for an isotopic purity of 93% (Equation 1). There was 1.9 ± 0.2 nmol of U-13C-ARA recovered, corresponding to a 5.0% conversion efficiency. This efficiency (with 0.1 gm/L glucose in the media) is 1.8-fold greater than the efficiency reported above with 5 gm/L glucose, which may be attributed to metabolic shifts in the organism under nutrient-limited conditions. The yield suggests that the specific activity of 14C-ARA may have been as high as 1210 Ci/mol (Equation 3), which is near the theoretical maximum of 62.4 Ci/mol/carbon for a 20-carbon molecule (i.e. 1248 Ci/mol). To the extent that the specific activity of U-14C-glucose is less than 360 Ci/mol, of course, the estimated specific activity for 14C-ARA will be lower.

In addition to ARA, six other fatty acids were identified in fungal extracts by Q1 mass spectrometry and associated with measurable 14C activity: linolenic acid (18:3ω3), linoleic acid (18:2ω6), eicosapentaenoic acid (20:5ω3), palmitic acid (16:0), oleic acid (18:1), and stearic acid (18:0) (Table 2). Notably, there was no docosahexanoic acid (22:5ω3) detected. The total activity recovered in these fractions was 2.0 ± 0.2 μCi, making the overall conversion efficiency for U-14C-glucose into fatty acids equal to 8.6 %, of which 53 % was ARA. The latter result is similar to the fraction of ARA in total fatty acids reported by Koike (~40–50%) for a C/N range of 15–20 in flask cultures (Koike et al., 2001).

Table 2.

Distribution of 14C Activity in the Fatty Acids Produced from [U-14C]glucose.

| Linolenic Acid | Arachidonic Acid | Linoleic Acid | Eicosapentaenoic Acid | Palmitic Acid | Oleic Acid | Stearic Acid | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Activity (μCi) a | 0.09 ± 0.02 | 2.29 ± 0.16 | 0.26 ± 0.13 | 0.14 ± 0.02 | 0.69 ± 0.30 | 0.50 ± 0.07 | 0.35 ± 0.02 |

| Conversion (%) | 0.18 | 4.6 | 0.51 | 0.28 | 1.4 | 1.0 | 0.70 |

| Elution time (min) | 21.82 | 25.77 | 27.56 | 30.38 | 34.02 | 35.19 | 43.55 |

| m/z ratio | 277 | 303 | 279 | 305 | 255 | 281 | 283 |

Fatty acids extracted and purified from M. alpina after 4 days of growth in 0.1 gm/L 14C-glucose media. Averages of three separate batches ± standard deviations.

4. Conclusion

U-13C-ARA and U-14C-ARA can be produced efficiently from isotope-labeled glucose on a laboratory scale. The use of low glucose concentrations in the cultivation media facilitates efficient conversion of the carbon atoms in glucose into carbon atoms in ARA. Upon separation by HPLC, the free fatty acid form of ARA may be purified in a form that is suitable for in vivo (intracerebroventricular) injection (Furman et al., 2016). In addition, smaller quantities of 6 other uniformly-labeled free fatty acids are obtained.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Procedures for the laboratory-scale preparation of U-13C-ARA and U-14C-ARA are described.

The yield of U-13C-ARA was >100 nmole with an isotopic purity of 95%

The yield of U-14C-ARA was > 2 μCi with an estimated specific activity of >1200 Ci/mol

Conversion efficiencies from glucose to ARA were 4–5%

Smaller quantities of other isotope-labeled fatty acids were also obtained.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NS74178 and GM76201 from the NIH, and from the Alzheimer’s Association, the American Health Assistance Foundation, and the Glenn Foundation (all to P.H.A.).

Footnotes

Supplementary Data associated with this article may be found in the online version at doi: _____________

Reference List

- 1.Bajpai PK, Bajpai P, Ward OP. Production of Arachidonic Acid by Mortierella alpina ATCC-32222. J Ind Micro. 1991;8:179–186. doi: 10.1007/BF01575851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bligh EG, Dyer WJ. A Rapdi Method of Total Lipid Extraction and Purification. Can J Biochem Physiol. 1959;37:911–917. doi: 10.1139/o59-099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.de Swaaf ME, de Rijk TC, van der Meer P, Eggink G, Sijtsma L. Analysis of docosahexaenoic acid biosynthesis in Crypthecodinium cohnii by C-13 labelling and desaturase inhibitor experiments. J Biotech. 2003;103:21–29. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1656(03)00070-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dyal SD, Narine SS. Implications for the use of Mortierella fungi in the industrial production of essential fatty acids. Food Res Int. 2005;38:445–467. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Esterbauer H, Benedetti A, LANG J, Fulceri R, Fauler G, Comporti M. Studies On the Mechanism of Formation of 4-Hydroxynonenal During Microsomal Lipid-Peroxidation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1986;876:154–166. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(86)90329-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Furman R, Murray IVJ, Schall HE, Liu Q, Ghiwot Y, Axelsen PH. Amyloid Plaque-Associated Oxidative Degradation of Uniformly Radiolabeled Arachidonic Acid. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2016;7:367–377. doi: 10.1021/acschemneuro.5b00316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ji XJ, Ren LJ, Nie ZK, Huang H, Ouyang PK. Fungal arachidonic acid-rich oil: research, development and industrialization. Crit Rev Biotech. 2014a;34:197–214. doi: 10.3109/07388551.2013.778229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ji XJ, Zhang AH, Nie ZK, Wu WJ, Ren LJ, Huang H. Efficient arachidonic acid-rich oil production by Mortierella alpina through a repeated fed-batch fermentation strategy. Biores Technol. 2014b;170:356–360. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2014.07.098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kawashima H, Akimoto K, Fujita T, Naoki H, Konishi K, Shimizu S. Preparation of C-13-Labeled Polyunsaturated Fatty-Acids by An Arachidonic Acid-Producing Fungus Mortierella-Alpina 1S-4. Anal Biochem. 1995;229:317–322. doi: 10.1006/abio.1995.1419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Koike Y, Cai HJ, Higashiyama K, Fujikawa S, Park EY. Effect of consumed carbon to nitrogen ratio on mycelial morphology and arachidonic acid production in cultures of Mortierella alpina. J Biosci Bioeng. 2001;91:382–389. doi: 10.1263/jbb.91.382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li XY, Lin Y, Chang M, Jin QZ, Wang XG. Efficient production of arachidonic acid by Mortierella alpina through integrating fed-batch culture with a two-stage pH control strategy. Biores Technol. 2015a;181:275–282. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2015.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li XY, Liu RJ, Li J, Chang M, Liu YF, Jin QZ, Wang XG. Enhanced arachidonic acid production from Mortierella alpina combining atmospheric and room temperature plasma (ARTP) and diethyl sulfate treatments. Biores Technol. 2015b;177:134–140. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2014.11.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marrow JD, Minton TA, Badr KF, Roberts LJ., II Evidence that the F2-Isoprostane, 8-epi-prostaglandin F2alpha, is Formed In Vivo. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1994;1210:244–248. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(94)90128-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miller GL. Use of Dinitrosalicylic Acid Reagent for Determination of Reducing Sugar. Anal Chem. 1959;31:426–428. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morrow JD, Awad JA, Boss HJ, Blair IA, Roberts LJ., II Non-cyclooxygenase-derived Prostanoids (F2-Isoprostanes) are Formed in situ on Phosphlipids. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:10721–10725. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.22.10721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Morrow JD, Minton TA, Mukundan CR, Campbell MD, Zackert WE, Daniel VC, Badr KF, Blair IA, Roberts LJ., II Free Radical-Induced Generation of Isoprostanes in Vivo. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:4317–4326. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schneider C, Tallman KA, Porter NA, Brash AR. Two distinct pathways of formation of 4-hydroxynonenal - Mechanisms of nonenzymatic transformation of the 9-and 13-hydroperoxides of linoleic acid to 4-hydroxyalkenals. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:20831–20838. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M101821200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shinmen Y, Shimizu S, Akimoto K, Kawashima H, YAMADA H. Production of Arachidonic-Acid by Mortierella Fungi - Selection of A Potent Producer and Optimization of Culture Conditions for Large-Scale Production. Appl Micro Biotech. 1989;31:11–16. [Google Scholar]

- 19.You JY, Peng C, Liu X, Ji XJ, Lu JM, Tong QQ, Wei P, Cong LL, Li ZY, Huang H. Enzymatic hydrolysis and extraction of arachidonic acid rich lipids from Mortierella alpina. Biores Technol. 2011;102:6088–6094. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2011.01.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhu M, Yu LJ, Li W, Zhou PP, Li CY. Optimization of arachidonic acid production by fed-batch culture of Mortierella alpina based on dynamic analysis. Enz Micro Technol. 2006;38:735–740. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.