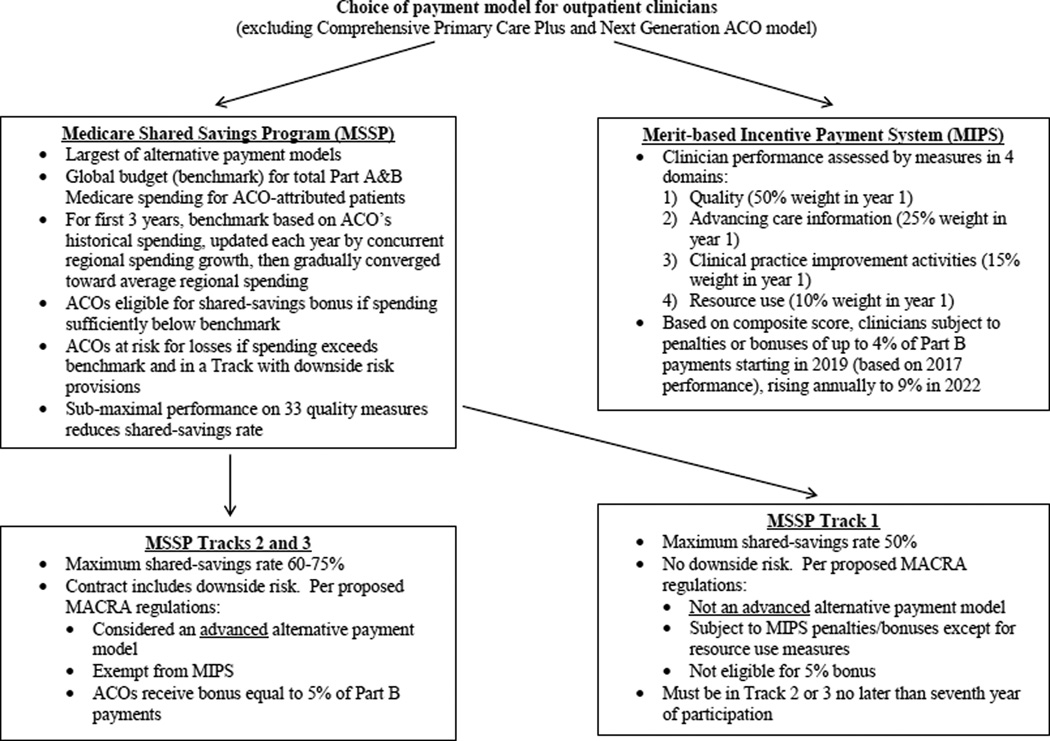

With 434 participating organizations, the Medicare Shared Savings Program (MSSP) represents the Affordable Care Act’s signature payment reform, the largest new payment model implemented by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), and the leading reason why the Department of Health and Human Services’ ambitious goal of tying 50% of fee-for-service Medicare payments to such models by 2018 remains possible. For each accountable care organization (ACO) in the MSSP, the program sets a benchmark for total spending for an attributed patient population and provides incentives to lower spending below the benchmark while providing high-quality care (Figure). Whether the MSSP will substantially reduce spending has been hotly debated and may very well shape the future of Medicare payment policy—and thus the opportunities for clinicians to be rewarded for high-value care.

Figure.

Anatomy of Payment Model Choice in Medicare

For the first 220 ACOs entering the MSSP in 2012 or 2013, actuarial calculations by CMS and an independent evaluation through 2013 indicated modest early spending reductions that were entirely offset by bonus payments to ACOs.(1) The offsetting bonus payments occurred in no small part because Track 1 of the MSSP—the predominant track chosen by 95% of current participants— requires no downside risk for spending in excess of benchmarks (Figure). Thus, Medicare pays shared-savings bonuses to many ACOs without recouping any portion of spending above ACO benchmarks. If spending fluctuated randomly, Medicare would incur losses from the program.

The lack of a net reduction in total Medicare spending was a major reason why Track 1 of the MSSP was not considered an advanced alternative payment model (advanced APM) by the recently proposed regulations for implementing the Medicare Affordability and CHIP Reauthorization Act (MACRA) of 2015.(2) The MACRA established a new status quo in fee-for-service Medicare—the Merit-based Incentive Payment System—that will adjust Part B payments to clinicians starting in 2019 based on a set of performance measures. Clinicians in advanced APMs are exempt from the otherwise mandatory Merit-based Incentive Payment System and will receive a lump sum bonus annually from 2019 through 2024 equal to 5% of their Part B reimbursements, followed by higher fee updates thereafter (Figure). Under the proposed MACRA regulations, ACO models are considered advanced APMs only if they involve downside risk (as in MSSP Tracks 2–3).

Instant savings from the MSSP, however, were unrealistic to expect. The fact that ACOs lowered spending at all within 1–2 years signified a promising behavioral response that established the prospect for growth in savings as ACOs redesign their care systems and learn which cost-cutting strategies are most effective. Indeed, more recent estimates indicate that spending reductions by ACOs in the MSSP roughly doubled from 0.8% in 2013 to 1.5% in 2014, exceeding bonus payments in 2014 and constituting a net savings to Medicare of $287 million.(3)

While these net savings amount to just 0.7% of total spending for beneficiaries in the MSSP, actual savings to Medicare are grossly underestimated both by CMS estimates and formal evaluations because spending reductions by ACOs have indirect effects on Medicare spending. First, provider responses to ACO contracts likely also affect care of patients served by ACOs but not attributed to them under the contracts. Conservatively assuming that a $1.00 reduction among attributed patients leads to a $0.20 reduction among non-attributed patients, and that at least half of ACOs’ Medicare revenue is devoted to non-attributed patients,(4) such spillover effects would have added upwards of $126 million in savings to Medicare in 2014.(3)

Second, spending reductions achieved by ACOs—regardless of offsetting bonus payments—lower ACO benchmarks because they lower the spending growth rates used to update benchmarks each year. Consequently, CMS’s comparisons of ACO spending with benchmarks underestimate actual ACO savings. The extent of underestimation will only grow as the MSSP expands and as regional spending trends replace national trends in benchmark updates—a recent change by CMS.(5) Third, spending reductions by ACOs similarly lower Medicare Advantage (MA) spending because MA plan payments are tied directly to local fee-for-service spending (as fee-for-service spending declines so do MA payments). With 1 in 4 fee-for-service beneficiaries currently in ACOs, for example, a 0.7% net spending reduction in the MSSP (as occurred in 2014) would be expected to lower MA spending by roughly $272 million.(6)

Thus, the actual net savings to Medicare attributable to the MSSP in 2014 was closer to $685 million, or 1.6% of spending for ACO patients. Although still modest, these early savings could be viewed as surprisingly large because MSSP incentives for ACOs to save have been very weak. Not only have shared-savings rates been low (≤50%), the original MSSP rules gave ACOs that lowered spending subsequently lower benchmarks, thereby undercutting incentives to ever lower spending.(7)

Recognition of the full and growing savings produced by the MSSP underscores the importance of encouraging program participation and calls for close scrutiny of the proposed exclusion of Track 1 from the definition of advanced APMs. The key policy decision before CMS is whether to use the 5% bonus under MACRA to encourage participation in ACO models broadly or only in models with downside risk. A strong argument could be made in favor of broader use of this participation incentive.

Because the 5% bonus is applied only to Part B payments for professional services, even modest savings from Track 1 would keep the costs of the bonus for Track 1 ACOs below the fee-for-service status quo. Moreover, growing savings among MSSP participants could grow further, particularly if incentives to save are strengthened,(1, 3, 8) and expanding the MSSP would accelerate indirect savings as long as expansion attracts more organizations that lower spending. In addition, all MSSP ACOs must eventually assume downside risk to stay in the program, and higher shared-savings rates could be used to encourage earlier entry into tracks with downside risk. Even if ACOs kept 100% of spending reductions below their benchmarks when bearing downside risk, Medicare would still save because the benchmarks would be lower if ACOs reduce spending, perhaps more so because higher shared-savings rates strengthen ACOs’ incentives to save. Finally, the 5% bonus may be particularly important for encouraging participation by physician groups that are not integrated with large systems or hospitals and thus lack the capital to invest in care infrastructure and financial reserves to cover potential losses from downside risk.(9, 10)

Redefining advanced APMs to include all MSSP tracks has become particularly important to the viability of the program in the wake of CMS’s recent decision to converge benchmarks for ACOs in the same region toward a common regional benchmark.(5, 8) Under original MSSP rules, benchmarks were based on ACOs’ historical spending levels so that ACOs would receive bonuses for improvement no matter their starting point. Under the revised rules, organizations with spending levels well above a regional average (and thus little hope for shared savings as benchmarks converge toward the regional average) will be less motivated to enter or continue in the program and to invest in strategies to lower spending. Thus, providing the 5% bonus to Track 1 ACOs would mitigate the risk of discouraging participation by high-spending organizations, which have generated the bulk of the savings so far.(1, 3)

CMS is under intense pressure to demonstrate savings from new payment models now. Any expectation beyond modest initial progress, however, was impossible to meet. Health care system reform is slow and incremental. Great strides are possible over a decade or two but require tradeoffs between short-term gains and long-term success. The implementation of recent legislation to encourage participation in new payment models presents such a tradeoff and an opportunity to build on a promising start to the ACO programs. It is time to acknowledge the early progress and allow policymakers to cast their gaze on the future.

Acknowledgments

Funding

Supported by grants from the Laura and John Arnold Foundation and the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health (P01 AG032952). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Laura and John Arnold Foundation or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Disclosures

Dr. McWilliams has no potential conflicts of interest to report.

REFERENCES

- 1.McWilliams JM, Hatfield LA, Chernew ME, Landon BE, Schwartz AL. Early Performance of Accountable Care Organizations in Medicare. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(24):2357–2366. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1600142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Department of Health and Human Services and Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare program; Merit-Based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) and alternative payment model (APM) incentive under the physician fee schedule, and criteria for physician-focused payment models. 2016 (available at: https://www.federalregister.gov/articles/2016/05/09/2016-10032/medicare-program-merit-based-incentive-payment-system-mips-and-alternative-payment-model-apm) [PubMed]

- 3.McWilliams JM. Changes in Medicare Shared Savings Program Savings from 2013 to 2014. JAMA. 2016 doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.12049. (published online: 10.1001/jama.2016.12049) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McWilliams JM, Chernew ME, Dalton JB, Landon BE. Outpatient care patterns and organizational accountability in Medicare. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(6):938–945. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Department of Health and Human Services and Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare program; Medicare Shared Savings Program; Accountable care organization-revised benchmark rebasing methodology, facilitating transition to peformance-based risk, and administrative finality of financial calculations. Final rule. 2016 (available at: https://s3.amazonaws.com/public-inspection.federalregister.gov/2016-13651.pdf) [PubMed]

- 6.Kaiser Family Foundation. The facts on Medicare spending and financing. 2015 (available at: http://files.kff.org/attachment/fact-sheet-the-facts-on-medicare-spending-and-financing) [Google Scholar]

- 7.Douven R, McGuire TG, McWilliams JM. Avoiding unintended incentives in ACO payment models. Health Aff (Millwood) 2015;34(1):143–149. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2014.0444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rose S, Zaslavsky AM, McWilliams JM. Variation In Accountable Care Organization Spending And Sensitivity To Risk Adjustment: Implications For Benchmarking. Health Aff (Millwood) 2016;35(3):440–448. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2015.1026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Colla CH, Lewis VA, Tierney E, Muhlestein DB. Hospitals Participating In ACOs Tend To Be Large And Urban, Allowing Access To Capital And Data. Health Aff (Millwood) 2016;35(3):431–439. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2015.0919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mostashari F, Sanghavi D, McClellan M. Health reform and physician-led accountable care: the paradox of primary care physician leadership. JAMA. 2014;311(18):1855–1856. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.4086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]