Abstract

Background

Tuberculosis (TB) remains a major cause of global morbidity and mortality, especially in the context of HIV co-infection, since immunity is not completely restored following antiretroviral therapy (ART). The identification of immune correlates of risk for TB disease could help in the design of host-directed therapies and clinical management. This study aimed to identify innate immune correlates of TB recurrence in HIV+ ART-treated individuals with a history of previous successful TB treatment.

Methods

Twelve participants with a recurrent episode of TB (cases) were matched for age, sex, time on ART, pre-ART CD4 count with 12 participants who did not develop recurrent TB in 60 months of follow-up (controls). Cryopreserved peripheral blood mononuclear cells from time points prior to TB recurrence were stimulated with ligands for Toll like receptors (TLR) including TLR-2, TLR-4, and TLR-7/8. Multi-color flow cytometry and intracellular cytokine staining was used to detect IL-1β, TNF-α, IL-12 and IP10 responses from monocytes and myeloid dendritic cells (mDCs).

Results

Elevated production of IL-1β from monocytes following TLR-2, TLR-4 and TLR-7/8 stimulation was associated with reduced odds of TB recurrence. In contrast, production of IL-1β from both monocytes and mDCs following Bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) stimulation was associated with increased odds of TB recurrence (risk of recurrence increased by 30% in monocytes and 42% in mDCs respectively).

Conclusion

Production of IL-1β by innate immune cells following TLR and BCG stimulations correlated with differential TB recurrence outcomes in ART-treated patients and highlights differences in host response to TB.

Keywords: Toll like receptor, monocytes, myeloid dendritic cells, HIV/TB co-infection, TB recurrence

INTRODUCTION

Tuberculosis (TB) is a global health problem causing nearly 10 million new infections every year. In particular, TB is the most common cause of death in HIV-infected individuals in Africa [1]. While TB infects approximately one third of the global population, the vast majority of these individuals readily contain TB infection, with only 5 to 10% developing active TB during their lifetime. A substantially higher risk of active TB does however exists in immunosuppressed individuals especially those with HIV co-infection [2].

South Africa has the highest burden of HIV and TB co-infection globally. Studies show that TB recurrence rates greatly depend on TB incidence and HIV prevalence [3–5]. A study conducted in South Africa reported that recurrent TB after successful treatment was up to four times that of new TB disease indicating a high risk of TB recurrence in people who experienced a TB episode [5]. Thus, factors that predispose individuals to TB acquisition may continue to play a role for susceptibility to TB recurrence as well.

Millenia of co-evolution with the host has equipped TB with many ways to elude natural immune defences and transit into a stage of relative dormancy [6–9]. Satisfactory control of TB would be best achieved using effective preventative TB vaccines. Progress in new TB vaccine development has been hampered by incomplete understanding of correlates of natural protection against TB that successful vaccines should emulate.

The continuum of host-pathogen interaction following infection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb) to Mtb disease traverses innate immune, adaptive immune, quiescent and active replicating phases of infection. This continuum may extend beyond successful Mtb treatment when the cycle of TB re-infection may occur. In approximately 5% of treated patients live Mtb infection persists, which may subsequently cause a relapse of TB disease, whereas in others re-infection with Mtb may cause subsequent TB disease [10]. Several biomarkers have been described that reflects the biology of TB infection and or disease, however to date no biomarker that accurately predicts latent, active TB or recurrent TB exists.

While the innate immune response is the first to encounter Mtb upon exposure, this arm of the immune system has not been well studied in the setting of TB in humans. Key immune cells that are the first contact include macrophages and dendritic cells, and these cells express Toll like receptors (TLRs) that recognize specific signatures on pathogens, initiating signaling pathways that trigger production of innate immune effector molecules, cytokines and chemokines. This response not only dictates the activity of the innate immune system, but is also critical in initiating the adaptive responses to Mtb likely leading to successful long-term containment [11]. Previous studies have implicated TLR-2 and TLR-4 in the direct recognition of Mtb [12, 13]. Data from a case-population study found a significant association between polymorphisms in a negative regulator gene of TLR/IL-1R signaling with increased TB susceptibility [14]. Additionally, an additive risk of TB susceptibility was observed with coinheritance of these polymorphisms and previously identified TLR risk alleles.

While antiretroviral therapy (ART) restores CD4 T cell numbers, effects of HIV infection on TB immunity are only partially reversed [15]. For example, reservoirs of HIV harbored in tissue macrophages make it difficult for eradication by ART and may lead to HIV-related neurological conditions [16, 17], and the impact of this reservoir on TB immunity in ART-treated subjects is unknown [18]. Defects in myeloid dendritic cell and monocyte function may result in impaired cytokine production, which could render individuals more susceptible to TB.

The interleukin 1 (IL-1) and type 1 interferon (type 1 IFN) signaling pathways are well studied in mouse models but poorly understood in humans, and have been shown to play opposing roles in Mtb host resistance. Type-1 IFNs contribute to pathogenesis through impairment of host resistance to Mtb [19, 20] while IL-1β is required for host control of infection [21]. Thus the balance between the IL-1β and type 1-IFN responses is pivotal for host survival during Mtb infection. In line with this work, recent reports in mouse models revealed a mechanism behind the role of IL-1 in TB containment is mediated by the induction of prostaglandin E2 by IL-1 which limits production of type-1 IFNs [22]. The study by Mayer-Barber and others provided proof of concept that therapies directed against the host innate inflammatory response are possible and can alter TB outcome. Given the fact that immunological features of TB differs in mice and humans (e.g. characteristic tissue destruction preceding pulmonary cavitation is found in humans and not mice), validating these findings among HIV infected patients most vulnerable to TB disease is critical.

We evaluated whether differences in innate immunological factors mediated protection or risk of TB recurrence through investigation of antigen presenting cell (APC) responses following stimulation with TLR ligands in Mtb/HIV co-infected participants on ART with a previously-defined history of successfully treated pulmonary TB.

METHODS

Study Design and Cohort

We conducted a nested case control study among 24 virally suppressed HIV-infected patients from a larger prospective cohort of 520 subjects conducted between 2009 and 2014 investigating the incidence of TB recurrence following successful TB treatment among stable patients on ART, the TB Recurrence upon Successful Treatment for Tuberculosis and HIV (TRuTH) study. All participants previously enrolled in a CAPRISA trial investigating timing of ART initiation during treatment for pulmonary TB [23] and with proven successful treatment for the previous TB episodes were eligible for enrolment into the TRuTH study. The TRuTH study screened participants quarterly over 60 months for TB recurrence, defined as first microbiologic confirmation of Mycobacterium tuberculosis by TB smear or TB culture. A total of 12 cases and 12 controls were selected from the overall cohort. Matching criteria for cases and controls included age (within a 5 year window), gender, study arm assignment in the previous trial, previous history of TB and baseline pre-ART CD4 count (within a 100 cells/μl window). Written informed consent was obtained from all study participants prior to enrolment and the University of KwaZulu-Natal Biomedical Research Ethics Committee approved the study (ref: BF 051/09; Clin trials.gov number NCT 01539005).

Peripheral blood mononuclear cell (PBMC) samples were collected prospectively and stored at 3–6 month intervals. Among the 12 cases, two time-points before TB recurrence were studied; and compared to time-points from the matched control subjects. There were 42 sample visits for the 12 controls, while for the 12 cases the number of sample visits in TB recurrent participants included pre-TB (n=16), untreated TB recurrence (n=11), TB treatment (n=13), and post-TB treatment (n=4).

In vitro stimulation of PBMCs with Toll-like receptor ligands

Cryopreserved PBMCs from cases and controls were thawed, re-suspended at 1 × 106 cells/ml in R10 media [RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum (FCS), 100U/ml penicillin, 1.7nM sodium glutamate and 5.5ml HEPES buffer] and rested for 2 hours at 37°C, 5% CO2. One million cells were stimulated with pre-titrated amounts of the following antigens: 1μg/ml of heat killed Listeria monocytogenes (TLR-2 HKLM), 1μg/ml Lipoarabinomannans from Mycobacterium smegmatis (TLR-2, LAM-MS), 0.1μg/ml of Lipopolysaccharide (TLR-4, LPS-EK), 1μg/ml thiazoloquinolone derivative (TLR-7/8, CL075); 75ng/ml of Trehalose-6,6-dibehenate (C-Type Lectin Receptor TDB), and 3μg/ml of Bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG). All ligands were from Invivogen aside from BCG (Statens Serum Institute). Samples with viability above 50% were used in experimental assays. The viability was not statistically different in cases and controls (median viability at baseline was 80% in cases and 64% in controls, P=0.17; and the median was 74% and 73% in cases and controls respectively for all time-points assessed (P=0.43). A negative control tube with PBMCs in media alone was included in all assays and for all analyses, cytokine production in stimulated samples was subtracted from the negative control with media alone. Brefeldin A (5μg/ml, Sigma) was added to all tubes immediately after adding the TLR ligands and stimulation of PBMCs was carried out for 18 hours at 37°C and 5% CO2. Due to sample limitations, stimulation with TB specific antigens LAM and TDB was performed in half of the participants.

Flow Cytometry

Following stimulation, PBMCs were washed with phosphate buffer saline (PBS) and stained for intracellular amine groups to differentiate live and dead cells using the aqua viability dye (Invitrogen) for 20 minutes at 4°C. Cells were then stained for 20 minutes at room temperature (RT) using monoclonal antibodies specific for the following surface markers: HLA-DR Pacific Blue (clone L243, Biolegend), CD14-APC CY7 (clone Mphip9), CD19-Alexa Flour 700 (clone HIB19), CD56-Alexa Flour 700 (clone B159), CD3-Alexa Flour 700 (clone UCHT1) and CD11c-PE Cy5 (clone B-ly6) (all from BD Biosciences). Cells were then washed, fixed with Fix/Perm Medium A (Caltag), and incubated for 20 minutes at RT. Cells were washed again, permeabilized (Fix/Perm B, Caltag) and stained for intracellular expression of: TNFα-PE Cy7 (clone MAb11), IL-12 (clone C11.5) APC, IL1β-FITC (clone AS10), IP10-PE (clone 6D4/D6/G2) (all from BD Biosciences) for 30 minutes at RT. Cells were finally washed and re-suspended in PBS before acquisition on an LRSII flow cytometer. At least 500,000 events were acquired per sample, and analyzed using the Flowjo software (version 9.4.11, TreeStar).

Statistical analyses

In order to assess the predictive value of cytokine expression on TB recurrence, a generalized estimating equations (GEE) model was fitted to case-control status, using a binomial distribution, accounting for possible repeated measures and controlling for matched variables. Cytokine concentrations measured at pre-TB time points were compared to all other time points from those individuals who never experienced a TB recurrence. Longitudinal assessment of IL-1β changes in APCs in participants with TB recurrence was done using Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed ranked test. Differences between groups and cytokine expression were considered statistically significant at the p<0.05 level. Statistical analysis was performed using SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary) and graphs were plotted using Graphpad Prism (version 5).

RESULTS

Clinical characteristics of participant groups

The incidence rate of TB recurrence in the overall cohort was 4.07 % (95%CI. 3.24–5.06). The median CD4 count for the studied participants was not statistically different at 289 cells/mm3 (IQR 105–470) for the cases and a median of 423 cells/mm3 (IQR 335–536) for the controls (p=0.2). The mean age was 34 years for the cases and 35 years for the controls and the cohort was predominantly female (67%) irrespective of the arm. The majority of the subjects were clinically stable, had their viral loads suppressed and had received ART for a median of 31 months (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics for nested case-control study participants, overall and stratified by TB recurrence outcome.

| Characteristic | All (n=24) | TB recurrence (n=12) | No TB recurrence (n=12) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Age in years at pre-ART; Mean (SD) | 34.7 (6.11) | 34.2 (5.73) | 35.2 (6.67) |

| Min to max | 24 – 47 | 24 – 43 | 24 – 47 |

|

| |||

| Female; n (%) | 16 (66.7%) | 8 (66.7%) | 8 (66.7%) |

|

| |||

| Integrated arm; n (%) | 16 (66.7%) | 8 (66.7%) | 8 (66.7%) |

|

| |||

| Previous history of TB; n (%) | 14 (58.3%) | 7 (58.3%) | 7 (58.3%) |

|

| |||

| Pre-ART CD4 count, cells/μl; Mean (SD) | 113 (72.06) | 114 (73.85) | 113 (73.50) |

| Min to max | 11 – 237 | 11 – 237 | 11 – 230 |

|

| |||

| Pre-ART Log viral load, copies/ml; Mean (SD) | 5.10 (0.83) | 5.14 (0.70) | 5.08 (1.00) |

| Min to max | 2.60 – 6.18 | 3.62 – 6.15 | 2.60 – 6.18 |

|

| |||

| Current time on ARVs in years*; Median (IQR) | 2.5 (1.9 – 3.6) | 3.1 (1.4 – 1.3) | 2.5 (0.7 – 1.6) |

|

| |||

| Current CD4 count, cells/μl; Mean (SD) | 453 (435.35) | 466 (604.73) | 439 (119.55) |

| Min to max | 14 – 2188 | 14 – 2188 | 271 – 671 |

|

| |||

| Current CD4 count, cells/μl; Median (IQR) | 354 (271 – 519) | 289 (105 – 470) | 423 (335 – 536) |

| Min to max | 14 – 2188 | 14 – 2188 | 271 – 671 |

|

| |||

| Current viral load suppressed**; n/N (%) | 19/23 (82.6%) | 8/12 (66.7%) | 11/11 (100%) |

|

| |||

| Weight, kg; Mean (SD) | 58.2 (8.75) | 59.1 (9.16) | 57.3 (8.62) |

|

| |||

| Body mass index; Mean (SD) | 21.6 (3.42) | 21.9 (3.62) | 21.4 (3.36) |

|

| |||

| Cavitory disease at occurrence; n (%) | |||

|

| |||

| No | 16 (66.7%) | 7 (58.3%) | 9 (75.0%) |

|

| |||

| One lung | 5 (20.8%) | 2 (16.7%) | 3 (25.0%) |

|

| |||

| Both lungs | 3 (12.5%) | 3 (25.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

|

| |||

| Infiltrates at occurrence; n (%) | |||

|

| |||

| No | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

|

| |||

| One lung | 7 (29.2%) | 1 (8.3%) | 6 (50.0%) |

|

| |||

| Both lungs | 17 (70.8%) | 11 (91.7%) | 6 (50.0%) |

|

| |||

| Adenopathy at occurrence; n (%) | |||

|

| |||

| No | 23 (95.8%) | 12 (100%) | 11 (91.7%) |

|

| |||

| One lung | 1 (4.2%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (8.3%) |

|

| |||

| Both lungs | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

|

| |||

| Pleural infusion at occurrence; n (%) | |||

|

| |||

| No | 21 (87.5%) | 12 (100%) | 9 (75.0%) |

|

| |||

| One lung | 3 (12.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | 3 (25.0%) |

|

| |||

| Both lungs | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

One TB recurrence case was not on ARVs at the time of enrolment on TRUTH and the pre-TB time point was a month prior to initiating treatment.

One patient, who did not experience TB recurrence, did not have VL data available at the first time point measured. Current refers to the very first time-point CD4 and VL were measured and duration of time on ARVs in this substudy.

APC frequencies between cases and controls

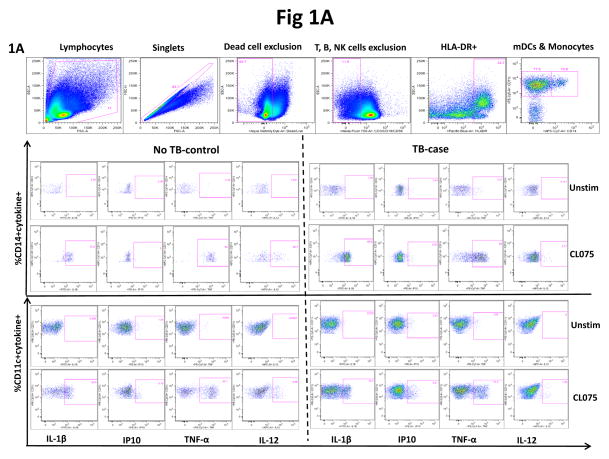

We first assessed the frequencies of monocytes and myeloid dendritic cells (mDCs) in cases and controls. Monocytes were defined as HLA-DR+CD11c+CD14+ and mDCs as HLA-DR+CD14−CD11c+ following gating on live cells and exclusion of T cells, B cells and NK cells (CD3−CD19−CD56−) respectively (see gating strategy in Figure 1A). The median baseline frequency of monocytes was 2.5% (IQR 2.1–7.6) in cases and 1.88% (IQR 0.4–4.1) of HLA-DR positive live dump negative PBMCs in controls. We also evaluated the frequencies of monocytes of following stimulation and neither of the comparisons were statistically significant suggesting that the frequency of the monocytes were not predictors of TB outcome in this study (p=0.14 without stimulation, or BCG (p=0.2), LPS (p=0.4), HKLM (p=0.15), CL075 (p=0.47) stimulated (data not shown).

Figure 1.

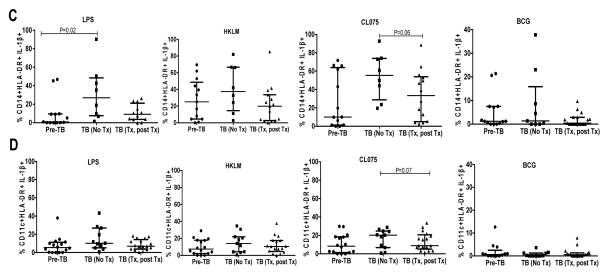

Representative gating strategy and measurement of all cytokines (IL-1β, IP10, TNF-α and IL-12) in monocytes (HLA-DR+CD11c+CD14+) and myeloid dendritic cells (mDCs; HLA-DR+CD14−CD11c+) following stimulation with TLR-7/8 ligand (CL075). (A) Gating was initially on lymphocytes followed by exclusion of cell doublets; dead cells, T cells, B cells and NK cell exclusion using the live/dead exclusion dye and CD3, CD19 and CD56 markers respectively followed by gating on HLA-DR positive cells. PBMCs were either unstimulated or stimulated with TLR-7/8 ligand (CL075) and all cytokine responses are shown for monocytes (HLA-DR+CD11c+CD14+), for first 2 rows and (mDCs; HLA-DR+CD14−CD11c+) for the last 2 rows in a control subject without TB recurrence (no TB) shown on the left panel or in an individual who experienced TB recurrence (case), shown of the right panel. Monocytes and mDC gates were each derived from the lineage negative followed by gating on HLA-DR positive cells. Initial representative gating strategy (top row) refers to an unstimulated sample. (B) Representative predictive (0–6mo & 6mo time points) cytokine (IL-1β) response profiles in monocytes (top panel) and mDCs (bottom panel) of individuals with TB recurrence (cases) during successful treatment of TB prior to TB recurrence (TB) versus controls (NTB) over time. Only cases sampled prior to TB recurrence (0–6mo & 6mo time-points) were analyzed as well as all control samples. Box and whiskers represent individual IL-1β responses in cases (red) and controls (blue, for monocytes or green for mDCs); the p-value refers to differences in IL-1β production between cases and controls at the predictive time-points (also referred to in Table 2 (monocytes) and Suppl Table 1 (mDCs) (C–D). Longitudinal assessment of IL-1β changes in monocytes (C) and mDCs (D) at pre-TB (n=16), during (n=11) and post TB (n=17) time-points in the TB recurrence group. Assessment of IL-1β changes in monocytes and mDCs of participants with TB recurrence was done using Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed ranked test. Lines represent median with inter-quartile range. Fewer time points were analyzed for monocytes compared to mDCs due to cell availability from cryopreserved PBMC.

In contrast, the median frequency of mDCs in cases was significantly higher than in controls at baseline and following antigen stimulation, suggesting that this could be an indicator to predict TB recurrence. At baseline, mDCs were detected at 61.1% (IQR 50.3–68.6) and 33.8% (IQR 20.7–57.3) of HLA-DR positive live dump negative PBMCs in controls (p=0.04 for unstimulated, p=0.02 for BCG, p=0.02 for LPS, p=0.008 for HKLM and p=0.01 for CL075 stimulation, data not shown).

Decreased IL-1β and TNF-α expression in monocytes is associated with the risk of TB recurrence

We next assessed whether APC function, particularly early cytokine production signatures in both monocytes and mDCs of cases and controls would predict TB recurrence. We initially analyzed the predictive time-point (closest to TB recurrence) in cases compared to the matched time-point in the controls and found lower cytokine production in cases than in controls, however these differences were not statistically significant (data not shown). Next, a generalized estimating equations (GEE) model using binomial distribution was fitted to case-control status and corrected for repeated measures and matched variables. Only cases sampled at two time-points prior to TB recurrence and all control samples were analyzed. We found that increased IL-1β expression was significantly associated with protection from TB recurrence when stimulated with several antigens including LPS, HKLM, CL075 and that this response was mostly mediated by monocytes (Table 2, Figure 1B). For every 1% increase in IL-1β (in response to LPS stimulation) in monocytes, the odds of TB recurrence decreased by 6% (OR 0.94; 95%CI 0.89 – 1.00, p=0.04, Table 2). Similar data were observed for HKLM (OR 0.96; 95%CI 0.92 – 1.00, p=0.05) and CL075 (OR 0.95; 95%CI 0.91 – 0.99, p=0.02). The expression of TNF-α, another pro-inflammatory innate mediator, was also decreased in monocytes following LPS stimulation in individuals who experienced TB recurrence (p=0.03, Table 2).

Table 2.

Association of monocyte cytokine responses with susceptibility to TB recurrence. Cytokine expression in monocytes from the cases, prior to TB acquisition and controls over time were analyzed using the Generalized Estimating Equations (GEE) model correcting for repeated measures and matched variables.

| Cytokine | No TB recurrence | TB recurrence | Unadjusted Odds Ratio (95%CI) | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Median (IQR) | N | Median (IQR) | |||

| Monocytes (CD14) | ||||||

| Antigen: BCG | ||||||

| IL-1β | 37 | 0.96 (0.00 – 2.86) | 12 | 1.46 (0.20 – 7.51) | 1.30 (1.09 – 1.55) | 0.0033 |

| IL-12 | 36 | 0.01 (0.00 – 0.51) | 9 | 0.08 (0.00 – 0.34) | 0.40 (0.01 – 11.15) | 0.5901 |

| IP10 | 36 | 0.13 (0.00 – 1.14) | 9 | 0.00 (0.00 – 1.34) | 1.53 (0.84 – 2.77) | 0.1640 |

| TNF-α | 36 | 1.19 (0.00 – 3.78) | 9 | 1.43 (0.38 – 5.41) | 1.06 (0.78 – 1.44) | 0.7162 |

| Antigen: LPS | ||||||

| IL-1β | 34 | 21.03 (0.00 – 45.51) | 11 | 0.92 (0.00 – 9.28) | 0.94 (0.89 – 1.00) | 0.0462 |

| IL-12 | 33 | 1.85 (0.00 – 7.28) | 9 | 3.08 (1.31 – 7.69) | 0.98 (0.85 – 1.13) | 0.8143 |

| IP10 | 33 | 0.00 (0.00 – 1.15) | 9 | 0.18 (0.00 – 2.86) | 0.94 (0.84 – 1.05) | 0.2807 |

| TNF-α | 33 | 57.44 (23.10 – 73.02) | 9 | 41.80 (20.95 – 61.51) | 0.95 (0.91 – 1.00) | 0.0316 |

| Antigen: HKLM | ||||||

| IL-1β | 38 | 45.45 (23.93 – 70.23) | 11 | 25.11 (4.44 – 52.85) | 0.96 (0.92 – 1.00) | 0.0564 |

| IL-12 | 37 | 4.81 (0.00 – 8.60) | 9 | 7.14 (4.51 – 7.75) | 1.07 (0.96 – 1.18) | 0.2294 |

| IP10 | 37 | 0.52 (0.00 – 1.92) | 9 | 2.13 (0.44 – 2.70) | 0.95 (0.86 – 1.04) | 0.2768 |

| TNF-α | 37 | 62.30 (28.50 – 74.55) | 9 | 59.60 (43.94 – 71.30) | 1.00 (0.95 – 1.05) | 0.9469 |

| Antigen: CL075 | ||||||

| IL-1β | 36 | 51.16 (32.04 – 73.55) | 11 | 10.05 (1.25 – 62.00) | 0.95 (0.91 – 0.99) | 0.0243 |

| IL-12 | 35 | 6.42 (2.02 – 15.30) | 9 | 11.29 (9.76 – 18.65) | 1.02 (0.96 – 1.08) | 0.5811 |

| IP10 | 35 | 0.09 (0.00 – 1.88) | 9 | 0.54 (0.00 – 1.54) | 1.61 (0.80 – 3.24) | 0.1815 |

| TNF-α | 35 | 62.88 (46.20 – 76.72) | 9 | 62.71 (24.45 – 77.10) | 0.99 (0.94 – 1.03) | 0.4948 |

| Antigen: LAMMS | ||||||

| IL-1β | 16 | 34.81 (28.60 – 56.89) | 5 | 12.50 (0.00 – 17.21) | N/A | |

| IL-12 | 15 | 1.19 (0.33 – 1.42) | 2 | 1.40 (0.95 – 1.85) | N/A | |

| IP10 | 15 | 0.00 (0.00 – 0.75) | 2 | 0.08 (0.00 – 0.16) | N/A | |

| TNF-α | 15 | 40.83 (28.90 – 52.18) | 2 | 43.49 (34.22 – 52.75) | N/A | |

| Antigen: TDB | ||||||

| IL-1β | 12 | 19.05 (8.97 – 33.42) | 5 | 0.00 (0.00 – 6.33) | N/A | |

| IL-12 | 11 | 4.61 (1.96 – 8.65) | 2 | 11.04 (9.17 – 12.90) | N/A | |

| IP10 | 11 | 0.00 (0.00 – 0.83) | 2 | 0.21 (0.00 – 0.42) | N/A | |

| TNF-α | 11 | 71.22 (52.90 – 76.01) | 2 | 77.64 (73.92 – 81.35) | N/A | |

Interestingly, no similar observations were noted with regards to IL-1β production in mDCs following stimulation with multiple TLR stimulations with the exception of TDB (Supplementary Table 1), suggesting that this IL-1β defect in the cases is mediated by the monocytes. We instead observed that BCG stimulation was associated with 42% and 30% increased risk of TB recurrence per 1% increase in IL-1β expression in both mDCs and monocytes (OR 1.42; 95% CI 1.04 – 1.95; p=0.02; OR 1.30; 95% CI 1.09 – 1.55; p=0.003; in mDCs and monocytes respectively, Supplementary Table 1 and Table 2). In addition we also noted a similar pattern of increased odds of TB recurrence with IL-12 production in response to HKLM stimulation only in mDCs, but not in response to other antigens or in monocytes. We did not observe any association of IP10 with TB recurrence.

Longitudinal changes in IL-1β expression amongst subjects with recurrent TB

We next investigated longitudinal changes in IL-1β levels beyond the predictive time-points in the TB recurrent group. Our findings showed a significant increase in IL-1β production on monocytes following LPS stimulation and only non-significant increase was noted for other stimulations during TB, however, these levels decreased following TB treatment suggesting that antigen load mediated the observed increase in the studied individuals. Differences were noted pre TB and during TB recurrence following stimulation with LPS (p=0.02) and a trend towards decreased IL-1β production was observed following CL075 stimulation during TB and post TB treatment (p=0.06). In addition, a trend towards higher IL-1β production was noted for CL075 stimulation following onset of TB recurrence and this decreased post TB treatment (p=0.07) in mDCs Fig 1C,D).

Taken together, our data show that the observed elevated production of IL-1β from monocytes following several antigen stimulations with TLR-2, TLR-4, TLR 7/8 may be associated with odds ratios of protection from TB recurrence and may therefore suggest that the status of the innate immune system, particularly impaired APC responses to TLR stimulation, may predict susceptibility to TB disease.

DISCUSSION

Factors that mediate protective immunity against Mtb are not fully understood and involve both innate and adaptive mechanisms. There is a need to identify biomarkers that accurately predict the risk of TB recurrence following successful treatment of TB, and define underlying immune mechanisms that may serve as vaccine or therapeutic targets. This study aimed to address this gap by investigating innate immune factors prospectively linked to TB outcomes. In particular, we investigated whether the functional status of antigen presenting cells confers protection or risk from TB recurrence amongst stable HIV-infected patients accessing ART with previous history of successful TB therapy.

Our findings show that of all cytokines tested following TLR stimulation; the overall expression of IL-1β, and to a lesser extent TNF-α, from monocytes was the best predictor of TB recurrence. We show that the cytokine production defect as demonstrated by lower IL-1β frequencies in the cases than in the controls was consistent across multiple TLR stimulations and may indicate a functional defect in monocytes following stimulation with TLR ligands. In addition, we demonstrated that APC responses to BCG stimulation were associated with increased risk of TB recurrence and may mark an important difference in innate host response to TB in cases compared to controls.

Phagocytes such as macrophages and dendritic cells are the first line of defense against TB, engulfing the bacilli and (if successful) limiting the severity of infection. They also alert the host to the presence of infection through pattern recognition of Mtb, thus coordinating the innate and subsequent adaptive host immune responses. The importance of IL-1β in mediating host response against TB has been previously reported [24]; and recent reports show that IL-1β directly augments TNF-signaling, up-regulates TNF secretion and TNFR1 cell surface expression leading to caspase-3 activation, apoptosis and direct killing of Mtb in macrophages [25]. Data from animal models and human clinical studies describe a network of pathways involving immune regulatory molecules that increase the risk of developing TB among which interleukins and interferons feature prominently [20, 21, 24, 26, 27]. Our findings on the IL-1β differences at the onset of TB are consistent with a report from a recent study conducted in mice infected with TB. The study demonstrated the importance of IL-1 in reducing disease severity through the induction of prostaglandin E2 levels (PGE2) that limit the production of type-I interferons, which are associated with increased TB disease severity [22]. The authors provided proof of concept for host-directed TB therapy and a potential for alternative options for TB infected individuals in the absence of a vaccine. We here make similar observations on the possible role of IL-1β in mediating TB containment, however the mechanism behind this defect or augmentation with some antigen stimulations requires further investigation in our cohort as well as in untreated HIV infected and HIV uninfected cohorts.

There are several other factors that could affect the innate immune system’s decreased capacity to respond, precipitating TB recurrence. Firstly, systemic inflammation that is not fully suppressed despite successful ART, may be an indication of low-level HIV-1 viremia and microbial translocation, which could be sources of continuous in vivo TLR stimulation of APCs. Secondly, Mtb can escape host recognition by inducing type 1 IFN that inhibits IL-1β release by macrophages and dendritic cells through suppression of IL-1β at transcriptional mRNA level [28, 29]. Expansion of patrolling monocytes with unusual phenotypes (CD16 expression and low levels of CD14) has been reported to be induced by HIV infection even in the presence of ART resulting in continuous TLR stimulation by the virus [30]. Host genetic factors may play a role in influencing the nature of the generated immune response [31, 32] accounting for the differences in outcome between the two study groups. Lastly, a defect in innate immunity as suggested by our findings or induced by any of the listed possible mechanisms, could result in failure to induce CD4+ T cell mediated immune responses well known to be fundamental to the control of Mtb. The above listed are some of the possible mechanisms that warrant follow-up investigation using this cohort. It was surprising to note that mDCs did not demonstrate a clear predictive outcome of TB risk with several antigens as noted for monocytes. Studies show that TB could induce impairment of dendritic cell maturation and increase IL-10 production known to suppress T cell response resulting in an imbalance of IFN- γ, enhanced IL-6 and IL-10 production and other causes implicated in low antigen-specific response and function associated with TB infection [33–35]. It is possible that the response of mDCs and monocytes to BCG as a risk factor for TB could be a pre-clinical response. Extremes in the ratio of peripheral blood to monocyte lymphocytes were found to be associated with increased risk of TB in HIV infected adults in South Africa and suggested to be a tool to stratify risk of TB [36]. In a separate study in infants who received BCG vaccination at birth and had higher monocyte to T cell ratios, transcriptional profiles were associated with an activated macrophage phenotype likely involved in pathogenesis of risk of TB disease suggesting that a phenotype of activated monocytes may be detrimental to the host [37]. It is thus important to classify the monocyte subsets behind this IL-1β response in further studies as well as measure associated soluble markers of inflammation.

The ability of monocyte/macrophages and myeloid dendritic cells (mDCs) to modulate immune responses relevant to TB immunity has been demonstrated [38, 39]. The long TLR stimulations employed in our study, the low frequency and identification of monocytes from frozen samples are some of the study limitations that warrant further interrogation in future studies. Nevertheless, our findings from a well described prospective cohort of HIV/TB co-infected individuals following multiple TLR stimulations of innate cells suggest that innate immune signaling may be an important predictor of TB pathogenesis. In particular, production of IL-1β by innate immune cells following TLR and BCG stimulations correlated with differential TB recurrence outcomes in ART-treated patients and highlights differences in host response to TB. While this is a pilot study with a very small participant sample size and needs to be validated in a larger cohort, with accompanying exploration of the innate mechanisms, it nonetheless supports recent findings and provides evidence in humans that IL-1β levels may have an impact on reactivation of TB. The study may therefore have public health implications calling for a need to identify individuals at risk for TB reactivation for host-directed therapies to reverse or reduce TB severity in TB endemic areas in the future.

Supplementary Material

Association of mDC cytokine responses with susceptibility to TB recurrence. Cytokines expression in mDCs from the cases, prior to TB acquisition and controls over time were analyzed using the Generalized Estimating Equations (GEE) model correcting for repeated measures and matched variables.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by Doris Duke Charitable Foundation and the South African Medical Research Council. We would like to thank the CAPRISA clinic team and participants of the SAPIT and TRUTH study at the eThekwini Clinic. The TRUTH study was supported by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, Grant # 55007065, as well as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Cooperative Agreement Number UY2G/PS001350-02. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of either the Howard Hughes Medical Institute or the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The research infrastructure to conduct this trial, including the data management, laboratory and pharmacy cores were established through the US National Institutes for Health’s Comprehensive International Program of Research on AIDS grant (CIPRA, grant # AI51794). KN was supported by the Columbia University-South Africa Fogarty AIDS International Training and Research Program (AITRP, grant # D43 TW000231). Patient care was supported by the KwaZulu-Natal Department of Health and the U.S. President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR). The funding sources listed here did not have any role in the analysis or preparation of the data in this manuscript, nor was any payment received by these or other funding sources for this manuscript. TN is an International Early Career Scientist of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute (Grant # 55007427) and received additional funding from the South African Research Chairs Initiative and the Victor Daitz Foundation (Grant # 64809).

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

None declared

References

- 1.Chaisson RE, Martinson NA. Tuberculosis in Africa--combating an HIV-driven crisis. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1089–1092. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp0800809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Corbett EL, Watt CJ, Walker N, Maher D, Williams BG, Raviglione MC, et al. The growing burden of tuberculosis: global trends and interactions with the HIV epidemic. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:1009–1021. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.9.1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Glynn JR, Murray J, Bester A, Nelson G, Shearer S, Sonnenberg P. High rates of recurrence in HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected patients with tuberculosis. J Infect Dis. 2010;201:704–711. doi: 10.1086/650529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sonnenberg P, Murray J, Glynn JR, Shearer S, Kambashi B, Godfrey-Faussett P. HIV-1 and recurrence, relapse, and reinfection of tuberculosis after cure: a cohort study in South African mineworkers. Lancet. 2001;358:1687–1693. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)06712-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Verver S, Warren RM, Beyers N, Richardson M, van der Spuy GD, Borgdorff MW, et al. Rate of reinfection tuberculosis after successful treatment is higher than rate of new tuberculosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171:1430–1435. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200409-1200OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cosma CL, Sherman DR, Ramakrishnan L. The secret lives of the pathogenic mycobacteria. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2003;57:641–676. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.57.030502.091033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Diedrich CR, Flynn JL. HIV-1/mycobacterium tuberculosis coinfection immunology: how does HIV-1 exacerbate tuberculosis? Infect Immun. 2011;79:1407–1417. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01126-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kaufmann SH. Tuberculosis vaccines: time to think about the next generation. Semin Immunol. 2013;25:172–181. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2013.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Monack DM, Mueller A, Falkow S. Persistent bacterial infections: the interface of the pathogen and the host immune system. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2004;2:747–765. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aaron L, Saadoun D, Calatroni I, Launay O, Memain N, Vincent V, et al. Tuberculosis in HIV-infected patients: a comprehensive review. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2004;10:388–398. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2004.00758.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hossain MM, Norazmi MN. Pattern recognition receptors and cytokines in Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection--the double-edged sword? Biomed Res Int. 2013;2013:179174. doi: 10.1155/2013/179174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Akamine M, Higa F, Arakaki N, Kawakami K, Takeda K, Akira S, et al. Differential roles of Toll-like receptors 2 and 4 in in vitro responses of macrophages to Legionella pneumophila. Infect Immun. 2005;73:352–361. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.1.352-361.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Poltorak A, He X, Smirnova I, Liu MY, Van Huffel C, Du X, et al. Defective LPS signaling in C3H/HeJ and C57BL/10ScCr mice: mutations in Tlr4 gene. Science. 1998;282:2085–2088. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5396.2085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Horne DJ, Randhawa AK, Chau TT, Bang ND, Yen NT, Farrar JJ, et al. Common polymorphisms in the PKP3-SIGIRR-TMEM16J gene region are associated with susceptibility to tuberculosis. J Infect Dis. 2012;205:586–594. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lawn SD, Myer L, Edwards D, Bekker LG, Wood R. Short-term and long-term risk of tuberculosis associated with CD4 cell recovery during antiretroviral therapy in South Africa. AIDS. 2009;23:1717–1725. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32832d3b6d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cobos-Jimenez V, Booiman T, Hamann J, Kootstra NA. Macrophages and HIV-1. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2011;6:385–390. doi: 10.1097/COH.0b013e3283497203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gavegnano C, Schinazi RF. Antiretroviral therapy in macrophages: implication for HIV eradication. Antivir Chem Chemother. 2009;20:63–78. doi: 10.3851/IMP1374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Walker NF, Meintjes G, Wilkinson RJ. HIV-1 and the immune response to TB. Future Virol. 2013;8:57–80. doi: 10.2217/fvl.12.123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stanley SA, Johndrow JE, Manzanillo P, Cox JS. The Type I IFN response to infection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis requires ESX-1-mediated secretion and contributes to pathogenesis. J Immunol. 2007;178:3143–3152. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.5.3143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Manca C, Tsenova L, Bergtold A, Freeman S, Tovey M, Musser JM, et al. Virulence of a Mycobacterium tuberculosis clinical isolate in mice is determined by failure to induce Th1 type immunity and is associated with induction of IFN-alpha/beta. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:5752–5757. doi: 10.1073/pnas.091096998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fremond CM, Togbe D, Doz E, Rose S, Vasseur V, Maillet I, et al. IL-1 receptor-mediated signal is an essential component of MyD88-dependent innate response to Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. J Immunol. 2007;179:1178–1189. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.2.1178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mayer-Barber KD, Andrade BB, Oland SD, Amaral EP, Barber DL, Gonzales J, et al. Host-directed therapy of tuberculosis based on interleukin-1 and type I interferon crosstalk. Nature. 2014;511:99–103. doi: 10.1038/nature13489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Abdool Karim SS, Naidoo K, Grobler A, Padayatchi N, Baxter C, Gray AL, et al. Integration of antiretroviral therapy with tuberculosis treatment. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:1492–1501. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1014181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mayer-Barber KD, Barber DL, Shenderov K, White SD, Wilson MS, Cheever A, et al. Caspase-1 independent IL-1beta production is critical for host resistance to mycobacterium tuberculosis and does not require TLR signaling in vivo. J Immunol. 2010;184:3326–3330. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0904189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jayaraman P, Sada-Ovalle I, Nishimura T, Anderson AC, Kuchroo VK, Remold HG, et al. IL-1beta promotes antimicrobial immunity in macrophages by regulating TNFR signaling and caspase-3 activation. J Immunol. 2013;190:4196–4204. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1202688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Berry MP, Graham CM, McNab FW, Xu Z, Bloch SA, Oni T, et al. An interferon-inducible neutrophil-driven blood transcriptional signature in human tuberculosis. Nature. 2010;466:973–977. doi: 10.1038/nature09247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Manca C, Tsenova L, Freeman S, Barczak AK, Tovey M, Murray PJ, et al. Hypervirulent M. tuberculosis W/Beijing strains upregulate type I IFNs and increase expression of negative regulators of the Jak-Stat pathway. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2005;25:694–701. doi: 10.1089/jir.2005.25.694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Novikov A, Cardone M, Thompson R, Shenderov K, Kirschman KD, Mayer-Barber KD, et al. Mycobacterium tuberculosis triggers host type I IFN signaling to regulate IL-1beta production in human macrophages. J Immunol. 2011;187:2540–2547. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1100926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Remoli ME, Giacomini E, Lutfalla G, Dondi E, Orefici G, Battistini A, et al. Selective expression of type I IFN genes in human dendritic cells infected with Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Immunol. 2002;169:366–374. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.1.366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cros J, Cagnard N, Woollard K, Patey N, Zhang SY, Senechal B, et al. Human CD14dim monocytes patrol and sense nucleic acids and viruses via TLR7 and TLR8 receptors. Immunity. 2010;33:375–386. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bellamy R. Susceptibility to mycobacterial infections: the importance of host genetics. Genes Immun. 2003;4:4–11. doi: 10.1038/sj.gene.6363915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moller M, de Wit E, Hoal EG. Past, present and future directions in human genetic susceptibility to tuberculosis. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2010;58:3–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2009.00600.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hanekom WA, Mendillo M, Manca C, Haslett PA, Siddiqui MR, Barry C, 3rd, et al. Mycobacterium tuberculosis inhibits maturation of human monocyte-derived dendritic cells in vitro. J Infect Dis. 2003;188:257–266. doi: 10.1086/376451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sakhno LV, Shevela EY, Tikhonova MA, Nikonov SD, Ostanin AA, Chernykh ER. Impairments of Antigen-Presenting Cells in Pulmonary Tuberculosis. J Immunol Res. 2015;2015:793292. doi: 10.1155/2015/793292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wolf AJ, Linas B, Trevejo-Nunez GJ, Kincaid E, Tamura T, Takatsu K, et al. Mycobacterium tuberculosis infects dendritic cells with high frequency and impairs their function in vivo. J Immunol. 2007;179:2509–2519. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.4.2509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Naranbhai V, Hill AV, Abdool Karim SS, Naidoo K, Abdool Karim Q, Warimwe GM, et al. Ratio of monocytes to lymphocytes in peripheral blood identifies adults at risk of incident tuberculosis among HIV-infected adults initiating antiretroviral therapy. J Infect Dis. 2014;209:500–509. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jit494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fletcher HA, Filali-Mouhim A, Nemes E, Hawkridge A, Keyser A, Njikan S, et al. Human newborn bacille Calmette-Guerin vaccination and risk of tuberculosis disease: a case-control study. BMC Med. 2016;14:76. doi: 10.1186/s12916-016-0617-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Akira S, Hemmi H. Recognition of pathogen-associated molecular patterns by TLR family. Immunol Lett. 2003;85:85–95. doi: 10.1016/s0165-2478(02)00228-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Takeda K, Akira S. Toll-like receptors in innate immunity. Int Immunol. 2005;17:1–14. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxh186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Association of mDC cytokine responses with susceptibility to TB recurrence. Cytokines expression in mDCs from the cases, prior to TB acquisition and controls over time were analyzed using the Generalized Estimating Equations (GEE) model correcting for repeated measures and matched variables.