Abstract

Several direct‐acting antiviral agents (DAAs) have marketing authorization in Europe and in the USA and have changed the landscape of hepatitis C treatment: each DAA has its own metabolism and drug–drug interactions (DDIs), and managing them is a challenge. To compile the pharmacokinetics and DDI data of the new DAA and to provide a guide for management of DDI. An indexed MEDLINE search was conducted using the keywords: DAA, hepatitis C, simeprevir, daclatasvir, ledipasvir, sofosbuvir, 3D regimen (paritaprevir/ritonavir, ombitasvir, dasabuvir), DDI and pharmacokinetics. Data were also collected from hepatology, and infectious disease and clinical pharmacology conferences abstracts. Food can play a role in the absorption of DAAs. Most of the interactions are linked to metabolism (cytochrome P450‐3 A4 [CYP3A4]) or hepatic and/or intestinal transporters (organic anion‐transporting polypeptide and P‐glycoprotein [P‐gp]). To a lesser extent other pathways can be involved such as breast cancer resistance protein transporter or UDP‐glucuronosyltransferase metabolism. DDI are more likely to occur with 3D regimen, daclatasvir, simeprevir and ledipasvir, as they are all both substrates and inhibitors of P‐gp and/or CYP3A4, than with sofosbuvir. They can increase concentrations of coadministered drugs and their concentrations may be influenced by P‐gp or CYP3A4 inducers or inhibitors. Overdosage or low dosage can be encountered with potent inducers or inhibitors of CYP3A4 or drugs with a narrow therapeutic range. The key to interpret DDI data is a good understanding of the pharmacokinetic profiles of the drugs involved. Their ability to inhibit CYP450‐3A4 and transporters (hepatic and/or intestinal) can have significant clinical consequences.

Keywords: direct‐acting antiviral, drug–drug interaction, hepatitis C, management

Tables of Links

| TARGETS | |

|---|---|

| Enzymes 2 | Transporters 3 |

| CYP1A2 | ABCB1 (P‐gp) |

| CYP2C8 | ABCG2 (BCRP) |

| CYP2C9 | OATP1B1 http://www.guidetopharmacology.org/GRAC/ObjectDisplayForward?objectId=2593 |

| CYP2C19 | |

| CYP2D6 | |

| CYP3A4 |

This Tables lists key protein targets and ligands in this article that are hyperlinked to corresponding entries in http://www.guidetopharmacology.org, the common portal for data from the IUPHAR/BPS Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 1, and are permanently archived in the Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2015/16 2, 3.

Background

The emergence of direct‐acting antiviral agents (DAAs) represents a major advance in hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection treatment. New DAAs include: new NS3 protease inhibitor simeprevir and paritaprevir boosted by ritonavir; the NS5A inhibitors daclatasvir, ledipasvir and ombitasvir; and the nucleotide NS5B polymerase inhibitors sofosbuvir and dasabuvir. They are approved in an interferon‐free regimen, with or without ribavirin 4, 5 and can cure 80–90% of patients 6, 7. Although highly effective and well tolerated, each DAA has its own metabolism and presents an important potential for drug–drug interactions (DDI). The most common metabolic pathways leading to DDI include CYP450, drug uptake transporters such as organic anion transporting polypeptide, and drug efflux transporters such as P‐glycoprotein (P‐gp) and breast cancer resistance protein (BCRP). DAAs can act as substrates, inhibitors and/or inducers of metabolic enzymes, and transporters, so they can increase toxicity or decrease effectiveness of coadministrated drugs and vice versa 8, 9. Comedications can influence the choice of a DAA. In clinical practice, non‐HCV medications that have the potential for interactions with HCV treatments are frequently prescribed to patients with chronic HCV infection 10, 11.

Understanding pharmacokinetic mechanisms is an essential prerequisite to manage DDI 12. In this review we summarise pharmacokinetics and DDI with new DAA agents against hepatitis C: simeprevir, daclatasvir, ledipasvir/sofosbuvir and 3D regimen, with a view to help clinicians manage DDI issues.

Methods

Only articles, abstracts and posters in English were selected. An indexed MEDLINE search was conducted concurrently from January 2007 until December 2015 by the medical head of hepatology department and a clinical pharmacist, using the keywords: “simeprevir”, “daclatasvir”, “ledipasvir”, “sofosbuvir”, “paritaprevir”, “ombitasvir”, “dasabuvir”, “direct‐acting antiviral”, “hepatitis C”, “hepatitis C treatment”, <AND > “drug–drug interactions” or <AND > “pharmacokinetic”. Randomised clinical trials, in vitro studies, prospective and retrospective human studies both in HCV infected patients and in healthy subjects, literature reviews, and expert clinician opinion papers were included. We collected all reviews and articles that summarised DDI for DAA.

Articles were first reviewed based on title and abstract (n = 134) and secondly on full text (n = 61). We excluded: the first generation protease inhibitors telaprevir and boceprevir as they are no longer used; new DAA that were still in clinical trials in Europe in 2015; DAAs that were discontinued; and articles on DDI simulations.

To complete the data, the two reviewers collected abstracts from hepatology, infectious diseases and clinical pharmacology meetings. Meetings selected were the Annual Meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD), the Annual Meeting of the European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL), HEPDART, The Annual Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (CROI), the Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy (ICAAC), and The International Workshop on Clinical Pharmacology of HIV and Hepatitis Therapy. Each meeting was screened to find all abstracts or posters regarding DAA and DDI and pharmacokinetics (n = 53). European summaries of product characteristics were also included (n = 5).

Results

All the factors that influence DAA pharmacokinetics are summarised in Table 1.

Table 1.

Factors influencing pharmacokinetic parameters of direct‐acting antiviral agents

| Sofosbuvir | Ledipasvir | Simeprevir | Daclatasvir | Paritaprevir (ABT‐450)

Ritonavir Ombitasvir (ABT‐267) Dasabuvir (ABT‐333) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Food effect | No 16 | No 16 | Take with food 13 | No 23 | Take with food 19 |

| Hepatic impairment | No dose adjustment for patients with mild, moderate or severe hepatic impairment 104 | No dose adjustment for patients with mild, moderate or severe hepatic impairment 105 | – Child–Pugh A, B: no dose adjustments | No dose adjustment for patients with mild, moderate or severe hepatic impairment 108 | – Child–Pugh A: no dose adjustment |

| – Child–Pugh C: no recommendation | – Child–Pugh: not recommended | ||||

| – Child–Pugh C: contraindicated 109 | |||||

| AUC 3‐fold higher than HCV‐compensated patients 107 | |||||

| Renal impairment | – mild or moderate renal impairment: no dose adjustment – severe renal impairment: sofosbuvir 200 mg was safe and well‐tolerated (but higher exposures up to 20‐fold of GS‐331 007 101, 102, 110 | – mild or moderate renal impairment: no dose adjustment | No dose adjustmentwith mild, moderate, or severe renal impairment 105, 106, 112 | No dose adjustment in renal impairment (unbound AUC of daclatasvir were increased 1.8‐ and 1.5‐fold, respectively in subjects with severe renal impairment compared with subjects with normal renal function 113, 114 | No dose adjustmentwith mild, moderate, or severe renal impairment. (change no clinically relevant) ESRD: safe 115, 116 |

| – severe renal impairment or ESRD: No dosage recommendation 111 | |||||

| Transporters | Sofosbuvir:

– P‐gp: substrate. – OATP 1B1/ B3: not a substrate GS 331007: – P‐gp: not a substrate – OATP 1B1/ B3: not a substrate 37 |

– P‐gp: substrate and weak inhibitor | – P‐gp: substrate and inhibitor | – P‐gp: substrate and inhibitor | ‐ P‐gp: substrate |

| ‐ OATP1B1/B3: substrate and inhibitor (paritaprevir) | |||||

| – OATPB1: substrate and inhibitor 28 | – OATP1B1: substrate and inhibitor 23 | ||||

| – OATPB1/B3: substrate and weak inhibitor 21 | – BCRP: substrate and inhibitor (ritonavir, dasabuvir) 19 | ||||

| Cytochromes and UGT A1 | Not a substrate or inhibitor or inducerof CYP3A4 14 | Not a substrate or inhibitor or inducer of CYP3A4 21 | Substrate of CYP3A4, mild inhibitor of intestinal (but not hepatic) CYP3A4 and 1 A2.No clinically relevant effects on CYP2C9, 2C19 or 2D6 22 | Substrate of CYP3A4. Not an inducer or inhibitor of CYP3A4 23 | Substrate and inhibitor of CYP3A4 (paritaprevir + ritonavir)

Substrate of CYP2C8 (dasabuvir) ‐ UGT1A1, inhibitor 19 |

| QT | Avoid with amiodarone or other bradycardia treatment 37 | Avoid with amiodarone or other bradycardia treatment 37 | Avoid with amiodarone or other bradycardia treatment 22 | No clinically relevant effect with therapeutic or supra‐therapeutic dose 23 | Contraindicated with CYP2C8 inhibitors 19 |

AUC, area under the curve; ESRD, end‐stage renal disease; HCV, hepatitis C virus; UGT, UDP‐glucuronosyltransferase; P‐gp, P‐glycoprotein

Food effects and absorption

Food increased the area under the curve (AUC) of simeprevir by 61% after a high‐fat, high‐calorie breakfast, so simeprevir is best taken with food 13.

Sofosbuvir is a prodrug that is converted to GS‐461 203, an active metabolite, and GS‐331 007, its predominant metabolite which represents >90% of the exposure 14, 15. As he exposure to GS‐331 007 was not altered in the presence of a high‐fat meal, sofosbuvir can be taken with or without food 16.

Ledipasvir exhibits pH‐dependent solubility but studies showed that AUC of ledipasvir and sofosbuvir were not significantly changed by H2‐receptor antagonists (famotidine) or omeprazole 20 mg if it is taken simultaneously. However, if omeprazole 20 mg was taken 2 h before ledipasvir, exposure to ledipasvir was decreased by 50% (Table 2) 16. As others dosages were not tested, ledipasvir should preferably not be taken with proton pump inhibitors 17. The administration of ledipasvir/sofosbuvir with a meal did not alter ledipasvir AUC or C max 16 so ledipasvir/sofosbuvir can be taken with or without food.

Table 2.

Drug–drug interactions between digestive drugs and direct‐acting antiviral agents (DAAs)

| Drug | DAA | Type of patients | Pharmacological effect on DAA AUC (%) | Pharmacological effect on coadministered drug AUC (%) | Recommendations | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Aluminium

Magnesium hydroxide

Calcium carbonate |

Daclatasvir | Not tested | No data. | |||

| Ledipasvir/ sofosbuvir | Not tested | Expected: ledipasvir ↓ (increase in gastric pH) | It is recommended to take antacid and ledipasvir‐sofosbuvir 4 hours apart. | 17 | ||

| Simeprevir | Not tested | Not expected. No dose adjustment. | 22 | |||

| Sofosbuvir | Not tested | No data. | ||||

| Famotidine | Daclatasvir | NA | ↔ | Increase in gastric pH | No dose adjustment. | 23 |

| Ledipasvir/ sofosbuvir | Healthy subjects | Simultaneous

ledipasvir ↔ 12 h stagger ↔ |

NA | H2‐receptor antagonists may be administered simultaneously with or staggered from ledipasvir/sofosbuvir at a dose that does not exceed doses comparable to famotidine at 40 mg twice daily. | 16 | |

| Simeprevir | Not tested | Not expected. No dose adjustment. | 22 | |||

| Sofosbuvir | Healthy subjects | Simultaneous

↔ sofosbuvir ↔ GS‐331 007: 12 h stagger ↔ sofosbuvir: ↔ GS‐331 007 |

NA | Do not exceed doses comparable to famotidine 40 mg twice daily. | 16 | |

| Omeprazole | Daclatasvir | NA | ↔ | NA | No dose adjustment. | 23 |

| Ledipasvir/sofosbuvir | NA | ↓ ledipasvir | NA | Proton pump inhibitors should not be coadministrated. | 16, 17 | |

| Simeprevir | NA | NA | ↑: +21% | Not considered clinically relevant. | 32 | |

| Sofosbuvir | NA | ↔ sofosbuvir ↔ GS‐331 007 | NA | No dose adjustment. | 16, 17 | |

| Ombitasvir/ paritaprevir/ ritonavir/ dasabuvir | ↔ ombitasvir

↔ paritaprevir ↔ dasabuvir |

↓ omeprazole with dasabuvir: −38%

without dasabuvir ↓ omeprazole −54% (CYP2C19 induction by ritonavir) |

Use higher dose of omeprazole if needed | 33 |

↔, no clinical change (< 25%); ↑, increase in AUC; ↓, decrease in AUC

AUC, area under the curve; HCV, hepatitis C virus; NA, not applicable

Daclatasvir C max and AUC were reduced by 28% and 23%, respectively with a high‐fat meal but this reduction was not considered clinically significant 18.

Paritaprevir is combined with ritonavir and ombitasvir in a tablet coat. Food increased the exposure (AUC) of 2D regimen by up to 82%, 211% and 49%, respectively relative to the fasting state, so the combination of these drugs should be taken with food 19, 20.

Food increased the AUC of dasabuvir by up to 30% compared to fasting. It is therefore recommended to take dasabuvir with food 19.

Distribution

Daclatasvir, simeprevir, ledipasvir and 3D regimen extensively bind to plasma proteins (> 98%), 19, 21, 22, 23. Sofosbuvir is 85% bound to human plasma proteins, whereas protein binding of GS‐331 007 is very low 21. Contrary to preconceived ideas, the concentration increase linked to competitive binding to plasma proteins rarely has any clinical impact 24, as kinetic interactions initially attributed to a protein displacement are actually explained by metabolic inhibition or by renal transport inhibition 24.

Effect of transporters

P‐pg

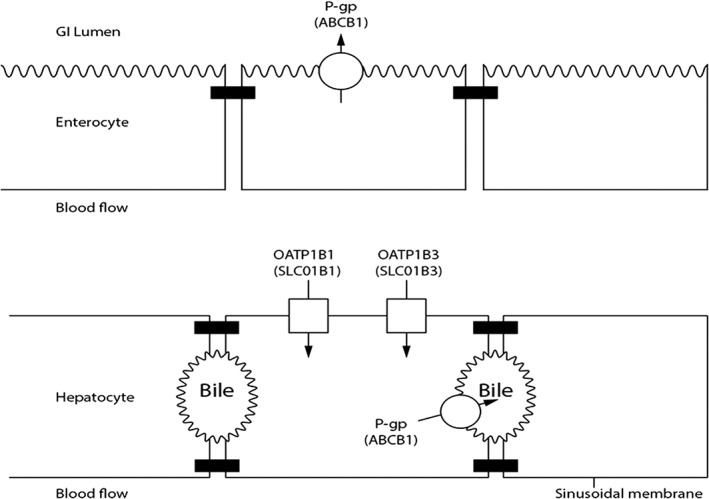

Drugs in enterocytes can be excreted back into the gut lumen by efflux transporters such as P‐gp (Figure 1). P‐gp can limit drug absorption 25. In the liver, P‐gp is a main transport protein on the bile canalicular membrane responsible for biliary excretion of drug metabolites 26, 27. Sofosbuvir and ombitasvir are substrate of P‐gp 14. Paritaprevir, ritonavir, dasabuvir, ledipasvir, daclatasvir and simeprevir are substrates and inhibitors of P‐gp 18, 19, 21, 28, 29 (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Transporters involved in drug–drug interaction of new DAAs

Coadministration of a P‐gp inhibitor (e.g. simeprevir, ledipasvir or daclatasvir) with a P‐gp drug substrate will block P‐gp's action and thus increases substrate absorption. Coadministration of a P‐gp inducer (i.e. rifampicin) with a P‐gp substrate results in a substrate concentration decrease. Thus rifampicin, when administered with ledipasvir/sofosbuvir, led to a 72% and 59% decrease in sofosbuvir and ledipasvir AUC, respectively 30, 31. P‐gp potent inducers should not be used with daclatasvir, ledipasvir/sofosbuvir or 3D regimen. In healthy subjects, administration of digoxin (a P‐gp substrate) with simeprevir or daclatasvir or ledipasvir or paritaprevir/ritonavir/ombitasvir (P‐gp inhibitors) led to a digoxin AUC increase of 39%, 27%, 34% and 36% AUC respectively 18, 30, 32, 33. Digoxin should thus be initiated at a lower dosage and be monitored.

P‐gp substrates are often also cytochrome P450 (CYP450) substrates, which make P‐gp interactions most often negligible when compared with cytochrome interactions 25. It should be noted, however, that a few drugs are exclusively P‐gp substrates, such as digoxin, and some nucleotide and nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTI) 34.

Organic anion‐transporting polypeptide

The organic anion‐transporting polypeptide 1B1 (OATP1B1) transporter at the sinusoidal pole of the hepatocyte is an influx transporter (Figure 1). This transporter is involved in the hepatic influx of some drugs such as statins (pravastatin, rosuvastatin) 35. Simeprevir, daclatasvir, ledipasvir, paritaprevir and ritonavir are all substrates and inhibitors of the OATP1B1 transporter, whereas sofosbuvir, ombitasvir and dasabuvir are not substrates 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19. In healthy subjects, administration of a single dose of rosuvastatin with simeprevir or daclatasvir at 60 mg once daily or 3D regimen results in a respectively AUC increase by 181%, 58% and 159%, by blocking their hepatic uptake 18, 28, 33. The dose of rosuvastatin should be decreased when coadministrated with simeprevir or daclatasvir, and should not exceed 5 mg with 3D regimen. Tolerance should be monitored 19, 28, 33. With 3D regimen pravastatin dose should be reduced by 50% 19, 33.

BCRP

BCRP (ABCG2) limits intestinal absorption of low‐permeability substrate drugs and mediates biliary excretion of drugs and metabolites. Many drugs were identified as substrates (e.g. sulfasalazine, rosuvastatine) or inhibitors of BCRP (e.g. curcumin, lapatinib) in vitro 36, yet clinical DDIs attributed directly and specifically to BCRP are limited due to overlap with other transporters, as well as metabolic pathways. Sofosbuvir is a substrate of BCRP whereas GS‐331 007 is not 37. Ombitasvir and simeprevir are substrates of BCRP 19. Paritaprevir, simeprevir, ritonavir, dasabuvir, ledipasvir and daclatasvir are inhibitors of BCRP 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28. However, sulfasalazine, curcumin, lapatinib have not been studied with any of DAAs. Only rosuvastatin was tested with daclatasvir, simeprevir and 3D regimen but the increase of rosuvastatin AUC could be also due to OATP inhibition 33.

Metabolism

Biotransformation very often involves isoenzymes of the cytochrome P450 superfamily especially the isoenzyme cytochrome P450‐3 A4 (CYP3A4). A drug with a narrow therapeutic range (immunosuppressants for example) can give rise to a clinically significant interaction more readily than a drug with a wide therapeutic range 38.

Effects of DAAs on CYP3A4 substrates

Sofosbuvir and ledipasvir are not metabolised by CYP3A4 37. Ledipasvir is slowly metabolised via an unknown mechanism 21 (Table 1). Sofosbuvir and ledipasvir have been tested in healthy volunteers with cyclosporine, tacrolimus, methadone, ethinyl oestradiol, all substrates of CYP3A4, without clinically significant interactions as expected (Tables 3, 4, 5) 28, 39, 42. Several studies have tested sofosbuvir and ledipasvir in post‐transplant patients and no interaction with any concomitant immunosuppressive agent was reported 43, 44. German et al. suggest that sofosbuvir with ledipasvir could be administered with cyclosporine or tacrolimus 30, 45.

Table 3.

Drug–drug interactions between immunosuppressants and direct‐acting antiviral agents (DAAs)

| Drug | DAA | Type of patients | Pharmacological effect on DAA AUC (%) | Pharmacological effect on coadministered drug AUC (%) | Recommendations | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tacrolimus | Daclatasvir | Healthy subjects | ↔ | ↔ | No clinically relevant interactions. Monitor blood concentration of tacrolimus. | 60 |

| Ledipasvir/ sofosbuvir | Not tested | Not expected. | 43, 109 | |||

| No dose adjustment. | ||||||

| Simeprevir | HCV transplanted patients | ↑ +85% | ↔ | No dose adjustments. | 51, 53 | |

| Sofosbuvir | Healthy subjects | ↔ | ↔ | No clinically significant interactions. | 40 | |

| 3D regimen | Healthy subjects | ↔ Ombitasvir

↓ paritaprevir −34% ↔ dasabuvir |

With dasabuvir ↑tacrolimus: +5610% Without dasabuvir↑tacrolimus: +8480% | No dose adjustment of 3D regimen initiate tacrolimus at 0.5 mg every 7 days and monitore blood concentration. | 47 | |

| Cyclosporin | Daclatasvir | Healthy subjects | ↑ + 40% | ↔ | No clinically relevant interactions. | 60 |

| Ledipasvir/ sofosbuvir | Not tested | Not expected. | 43, 109 | |||

| Simeprevir | HCV transplanted patient | ↑ + 481% | ↔ | Significantly increased plasma SMV concentrations. | 51, 53 | |

| Sofosbuvir | Healthy subjects | ↑Sofosbuvir +353% ↔ GS 331007 | ↔ | No clinically significant interactions. | 40 | |

| 3D regimen | ↔ Ombitasvir

↑ paritaprevir (with dasabuvir): +72% ↑ paritaprevir +46% (without dasabuvir) ↓ dasabuvir: −30% |

With dasabuvir

↑ cyclosporin: +482% without dasabuvir ↑ cyclosporin: +328% |

Give one fifth of the total daily dose of cyclosporin once daily with 3D regimen. Monitor cyclosporin levels No dose adjustment needed for 3D regimen. | 47 |

↔, no clinical change (< 25%); ↑, increase in AUC; ↓, decrease in AUC

AUC, area under the curve; HCV, hepatitis C virus

Table 4.

Drug–drug interactions between neuropsychiatric drugs and direct‐acting antiviral agents (DAAs)

| Drug | DAA | Type of patients | Pharmacological effect on DAA AUC (%) | Pharmacological effect on coadministered drug AUC (%) | Recommendations | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Escitalopram | Daclatasvir | NA | ↔ | ↔ | No dose adjustment. | 23 |

| Ledipasvir/ sofosbuvir | Not tested | No data. | ||||

| Simeprevir | Healthy subjects | ↓: −25% | ↔ | Not expected. No dose adjustment. | 99 | |

| Sofosbuvir | Not tested | No data. | ||||

| 3D regimen | ↔ ombitasvir

↔ paritaprevir ↔ dasabuvir |

↔ escitalopram

↑ S‐desmethyl‐citalopram (with dasabuvir) + 36% ↔ S‐desmethyl‐citalopram (without dasabuvir) |

No dose adjustment. | 33 | ||

| Duloxetine | 3d regimen | ↔ ombitasvir

↔ paritaprevir ↔ dasabuvir |

↓ duloxetine: −25% | No dose adjustment. | 33 | |

| Alprazolam | 3D regimen | ↔ ombitasvir

↔ paritaprevir ↔ dasabuvir |

↑ alprazolam: +34% | If needed, decrease the dose of alprazolam. | 33 | |

| Midazolam | Daclatasvir | healthy subjects | NA | ↔ | No clinically significant interaction. | 110 |

| Ledipasvir/ sofosbuvir | Not tested | No data. | ||||

| Simeprevir | NA | ↑ midazolam oral +45% ↔ midazolam i.v: | Simeprevir exhibits clinically relevant CYP3A4 inhibition in the intestine (with per os midazolam) but not in the liver (intravenous midazolam). Caution with midazolam oral. | 32 | ||

| Sofosbuvir | Not tested | No data. | ||||

| Zolpidem | 3D regimen | ↔ ombitasvir

↓ paritaprevir: −32% ↔ dasabuvir |

↔ zolpidem | No dose adjustment. | 33 | |

| Methadone | Daclatasvir | NA | No change | ↔R‐methadone | No dose adjustment. | 23 |

| Ledipasvir/ sofosbuvir | Not tested | Not expected. | 21 | |||

| Simeprevir | HCV negative | ↔R‐methadone ↔S‐methadone | No dose adjustment. | 115 | ||

| Sofosbuvir | HCV negative patients | ↑ Sofosbuvir: +30% ↔ GS‐331 007 | ↔S‐methadone ↔R‐methadone | No dose adjustment. | 39 | |

| 3D regimen | ↔ | ↔ R‐Methadone ↔ S‐Methadone | No dose adjustment. | 85 | ||

| Buprenorphine/ naloxone | Daclatasvir | No change | ↔Buprenorphine

↑norbuprenorphine +62% |

No dose adjustment. | 23 | |

| Ledipasvir/ sofosbuvir | Not tested | No data. | ||||

| Simeprevir | Not tested | Not expected. No dose adjustment. | 22 | |||

| Sofosbuvir | Not tested | No data | ||||

| Ombitasvir/ paritaprevir/ ritonavir/ dasabuvir | ↔ paritaprevir /ombitasvir/ dasabuvir | ↑ buprenorphine with dasabuvir: +107%

↑ buprenorphine (without dasabuvir): +51% ↑ norbuprenorphine +84% ↑ naloxone: +28% |

No dose adjustment. | 85 | ||

| Dextromethorphan | Simeprevir | Healthy subjects | NA | ↔ | No dose adjustment. | 32 |

|

Anticonvulsants

(carbamazepine

Oxcarbazepine Phenobarbital Phenytoin) |

Daclatasvir | Not tested | Expected: AUC daclatasvir ↓ (strong induction of CYP3A4) | Coadministration of daclatasvir with (ox) carbamazepine, phenobarbital, phenytoin or other strong inducers of CYP3A4 is contraindicated. | 23 | |

| Ledipasvir/ sofosbuvir | Not tested | Expected: ledipasvir/ sofosbuvir↓ (Induction of P‐gp) | Not recommended. Loss of therapeutic effect of ledipasvir. | 21 | ||

| Simeprevir | Not tested | Expected: simeprevir↓ (strong induction of CYP3A4) | Not recommended. Loss of therapeutic effect of simeprevir. | 22 | ||

| Sofosbuvir | Not tested | Expected: ↓ sofosbuvir AUC ↓ GS‐331 007 | Not recommended. Loss of therapeutic effect of ledipasvir. | 37 | ||

| 3D regimen | Healthy subjects | ↓ ombitasvir −30%

↓ paritaprevir −30% ↓ dasabuvir −70% |

↔Carbamazepine | Contraindicated. | 33 |

↔, no clinical change (< 25%); ↑, increase in AUC; ↓, decrease in AUC

AUC, area under the curve; HCV, hepatitis C virus; NA, not applicable

Table 5.

Drug–drug interactions between contraceptives and direct‐acting antiviral agents (DAAs)

| Drug | DAA | Type of patients | Pharmacological effect on DAA AUC (%) | Pharmacological effect on coadministered drug AUC (%) | Recommendations | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ethynilestradiol/ Norgestimate | Daclatasvir | Healthy female subjects | NA | ↔: EE:

↔ norelgestromin ↔ norgestrel. |

No clinically relevant effects. | 116 |

| Ledipasvir/ sofosbuvir | HCV‐uninfected women | NA | ↔ norelgestromin

↔ norgestrel ↔ ethinylestradiol |

No dose adjustment. | 42 | |

| Simeprevir | Healthy female volunteers | ↔ EE: ↔ norethindrone | No dose adjustment. | 117 | ||

| Sofosbuvir | HCV‐uninfected women | NA | ↔ norgestromin ↔ norgestrel ↔ ethinyl oestradiol | No dose adjustment. | 42 | |

| 3D regimen | ↔ ombitasvir

↓ paritaprevir: −34% ↓ dasabuvir −52% |

↔ EE

↑ norgestrel: +154% ↑ norelgestromine +160% |

Ethinyl oestradiol‐containing oral contraceptives are contraindicated. | 33 | ||

| Norethindrone | 3D regimen | ↔ ombitasvir

↑ paritaprevir:+23% ↔ dasabuvir: |

↔ norethindrone | No dose adjustment. | 33 |

↔, no clinical change (< 25%); ↑, increase in AUC; ↓, decrease in AUC

AUC, area under the curve; HCV, hepatitis C virus; NA, not applicable

Paritaprevir, ombitasvir and dasabuvir are substrates of CYP3A4 19. Paritaprevir is an inhibitor of CYP3A4 and ritonavir is used as a booster in 3D regimen because it is a strong inhibitor of CYP3A4 that leads to increased bioavailability of paritaprevir 20. Ritonavir of the 3D regimen increases human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) protease inhibitors exposure, which is why the recommended dose of darunavir is 800 mg once daily and the recommended dose of atazanavir is 300 mg once daily, without ritonavir, when administered with 3D regimen 46.

3D regimen with substrates of CYP3A4 could increase coadministered drug exposition. A phase 1 study demonstrated a three‐fold increase in cyclosporine half‐life and seven‐fold increase in tacrolimus half‐life when administered concomitantly with 3D regimen 47. Therefore, in liver transplant recipients with recurrent HCV genotype 1 infection on stable cyclosporine or tacrolimus therapy, cyclosporine was reduced to 20% of the usual daily dose given once daily, while tacrolimus was reduced to either 0.5 mg once weekly or 0.2 mg every 3 days 48. Dick et al. recommend empirically close monitoring, 2–3 times a week when 3D regimen is used with immunosuppressive agents 49.

Simeprevir is a substrate and mild inhibitor of CYP3A4 in the intestine by increasing midazolam AUC by 45% when administered orally and C max by 31%, 32 (Table 4) 50. In healthy volunteers, administration of single atorvastatin dose at 40 mg or simvastatin at 40 mg with simeprevir increases atorvastatin AUC by 110% and simvastatin AUC by 50%, probably via inhibition of CYP3A and OATP by simeprevir 32 (Table 6).

Table 6.

Drug–drug interactions between cardiovascular drugs and direct‐acting antrtiviral agents (DAAs)

| Drug | DAA | Type of patients | Pharmacological effect on DAA AUC (%) | Pharmacological effect on coadministered drug AUC (%) | Recommendations | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Atorvastatin | Daclatasvir | Not tested | Expected: ↑ (inhibition of OATPB1 by daclatasvir) | Use with caution. | 23 | |

| Ledipasvir/ sofosbuvir | Not tested | Expected: ↑ | A reduced dose of statins should be considered. | 21 | ||

| Simeprevir | NA | ↑ +112% | Titrate the atorvastatin dose carefully and use the lowest necessary dose while monitoring for safety. | 32 | ||

| Sofosbuvir | Not tested | No data. | ||||

| 3D regimen | Not tested | Contraindicated. | 19 | |||

| Pravastatin | Daclatasvir | Not tested | Expected: ↑ (OATP1B1 inhibition by daclatasvir) | Clinical and biochemical control. A dose adjustment may be needed. | 23 | |

| Ledipasvir/ sofosbuvir | NA | NA | ↑ +168% | Clinical and biochemical control. A dose adjustment may be needed. | 114 | |

| Simeprevir | Not tested | Expected: AUC pravastatin ↑ (OATP1B1 inhibition by simeprevir) | Titrate pravastatin dose and use the lowest necessary dose while monitoring for safety. | 22 | ||

| Sofosbuvir | Not tested | No data. | ||||

| 3D regimen | ↔ ombitasvir

↔ dasabuvir ↔ paritaprevir (with dasabuvir) ↑ paritaprevir (without dasabuvir) |

↑ +82% | Reduce pravastatin dose by 50%. No dose adjustment needed for 3D regimen with or without dasabuvir. | 33 | ||

| Rosuvastatin | Daclatasvir | NA | NA | ↑ +58% (OATP 1B1 inhibition by daclatasvir) | Use with precaution and with a lower dose. | 23 |

| Ledipasvir/ sofosbuvir | NA | NA | ↑ +699% | Contraindicated. | 114 | |

| Simeprevir | NA | NA | ↑ +181% (OATP1B1 inhibition by simeprevir) | Titrate rosuvastatin dose and use the lowest necessary dose while monitoring for safety. | 32 | |

| Sofosbuvir | Not tested | No data. | ||||

| 3D regimen | ↔ ombitasvir

↑ paritaprevir (with dasabuvir): +52% ↔ paritaprevir (without dasabuvir) ↔ dasabuvir |

With dasabuvir

↑ rosuvastatin: +159% Without dasabuvir ↑ rosuvastatin: +33% |

With dasabuvir, the maximum daily dose of rosuvastatin should be 5 mg Without dasabuvir, the maximum daily dose of rosuvastatin should be 10 mg. No dose adjustment for 3D regimen. | 33 | ||

| Simvastatin | Daclatasvir | Not tested | OATP inhibition by daclatasvir is expected | A reduced dose of statins should be considered careful monitoring for statin adverse reactions. | 23 | |

| Ledipasvir/ sofosbuvir | Not tested | Expected: ↑ possible OATP inhibition by ledipasvir | A reduced dose of statins should be considered and careful monitoring for statin adverse reactions. | 21 | ||

| Simeprevir | NA | ↑ +51% (OATP inhibition and CYP3A4 by simeprevir) | Titrate simvastatin dose carefully and use the lowest necessary dose while monitoring for safety. | 32 | ||

| Sofosbuvir | Not tested | No data. | ||||

| 3D regimen | Not tested | Contraindicated. | 23 | |||

| Gemfibrozil | 3d regimen | ↑ paritaprevir +38%

OATP inhibition by gemfibrozil ↑ dasabuvir + 1025% (CYP2C8 inhibition by gemfibrozil) |

NA | Contraindicated. | 33 | |

| Calcium channel blockers | Daclatasvir | Not tested | Expected: ↑daclatasvir (moderate inhibition of CYP3A4 by verapamil, diltiazem, mild inhibition by amlodipine) | Use with caution. | 23 | |

| Ledipasvir/ sofosbuvir | Not tested | Not expected. | 21 | |||

| Simeprevir | Not tested | Expected: ↑simeprevir (moderate inhibition of CYP3A4 by verapamil, diltiazem, mild inhibition by amlodipine) | Use with caution. | 22 | ||

| Sofosbuvir | Not tested | No data. | ||||

| 3D regimen | ↔ ombitasvir

↓ paritaprevir: −22% ↔ dasabuvir |

↑amlodipine: +157% | Decrease the dose of amlodipine by 50%. | 33 | ||

| Valsartan | 3d regimen | Not tested | Expected: ↑ (OATP1B inhibition by paritaprevir.) | Clinical monitoring and dose reduction is recommended. | 19 | |

| Furosemide | 3D regimen | ↔ ombitasvir

↔ paritaprevir ↔ dasabuvir |

↑ furosemide possibly due to UGT1A1 inhibition by paritaprevir, ombitasvir and dasabuvir. | A decrease in furosemide dose of up to 50% may be required. No dose adjustment needed for Viekirax with or without dasabuvir. | 33 | |

| Alfuzosine | 3d regimen | Not tested | Expected: ↑ (CYP3A4 inhibition by ritonavir) | Contraindicated. | 33 | |

| Dabigatran | Daclatasvir | Not tested | Expected: ↑ dabigatran (inhibition of P‐gp) | Safety monitoring is advised when initiating. | 23 | |

| Ledipasvir/ sofosbuvir | Not tested | Expected: ↔ ledipasvir | Expected ↑ dabigatran (inhibition of P‐gp) | Clinical monitoring is recommended. | 21 | |

| Simeprevir | Not tested | Expected ↑ dabigatran (inhibition of P‐gp) | Safety monitoring is advised when initiating. | 22 | ||

| Sofosbuvir | Not tested | Expected: ↔sofosbuvir ↔ GS‐331 007 | Not expected. | |||

| 3D regimen | Not tested | Expected: AUC↑ (inhibition of P‐gp by paritaprevir and ritonavir | Use with caution. | 19 | ||

| Digoxine | Daclatasvir | NA | ↑ + 27% (P‐gp inhibition by daclatasvir) | The lowest dose of digoxin should be initially prescribed. Serum digoxin concentrations should be monitored. | 23 | |

| Ledipasvir/ sofosbuvir | NA | NA | ↑ +34% | Monitor for serum digoxin. | 114 | |

| Simeprevir | Healthy subjects | NA | ↑ +39% (P‐gp inhibition by simeprevir) | AUC increase of digoxin. Monitor for digoxin blood concentration. | 32 | |

| Sofosbuvir | Not tested | No data. | ||||

| 3D regimen | No change | With dasabuvir ↔ Without dasabuvir↑ | With dasabuvir; no dose adjustment. Without dasabuvir decrease digoxin dose by 30–50%. Monitor for digoxin blood concentration. | 33 | ||

| Amiodarone/quinidine | Daclatasvir | Not tested | Expected: ↑ (inhibition of CYP3A4 by amiodarone.) | Use only if no other alternative is available. Close monitoring is recommended. | 23 | |

| Ledipasvir/ sofosbuvir | Not tested | Case of severe bradycardia | Use only if no other alternative is available. Close monitoring is recommended. | 21 | ||

| Simeprevir | Not tested | Expected: ↑ (due to inhibition of CYP3A4 by amiodarone) | Expected: ↑ amiodarone (intestinal CYP3A4 enzyme inhibition) | Use only if no other alternative is available. Close monitoring is recommended. | 22 | |

| Sofosbuvir | Not tested | Case of severe bradycardia | Use only if no other alternative is available. Close monitoring is recommended. | 37, 115 | ||

| 3D regimen | Not tested | Expected: ↑ amiodarone (intestinal CYP3A4 enzyme inhibition) | Contraindicated. | 19 | ||

| Warfarin | Daclatasvir | Not tested | No dose adjustment but monitor for INR. | 23 | ||

| Ledipasvir/ sofosbuvir | Not tested | No data, monitor for INR. | ||||

| Simeprevir | Healthy volunteers | NA | ↔ | Not considered clinically significant. Monitor for INR. | 22 | |

| Sofosbuvir | Not tested | No data, monitor for INR. | ||||

| 3D regimen | ↔ ombitasvir

↔ paritaprevir ↔ dasabuvir |

↔ | No dose adjustment, monitore for INR. | 23 |

↔, no clinical change (< 25%); ↑, increase in AUC; ↓, decrease in AUC

AUC, area under the curve; INR, International Normalised Ratio; NA, not applicable; OATP, organic anion‐transporting polypeptide

Sometimes, interactions are not as expected. For example, simeprevir with single‐dose tacrolimus at 2 mg resulted in a 17% decrease in tacrolimus AUC compared with tacrolimus administered alone 51. With cyclosporine, simeprevir increased cyclosporine AUC by 19%, which was not considered clinically relevant 51. However, therapeutic drug monitoring is recommended 52. These results were confirmed in the SATURN study 28, 53 but cyclosporine increased simeprevir exposure AUC by 481% so the coadministration is now contraindicated (Table 3). Apart from this result, new DAAs in liver transplanted patients have a good safety profile 54, 55, 56, 57, 58.

Daclatasvir is a CYP3A4 substrate 19, 23. Tacrolimus and cyclosporin were unaffected by concomitant administration of multiple doses of daclatasvir 59, 60. Studies conducted in liver‐transplanted patients treated with tacrolimus or everolimus or cyclosporine confirms that the coadministration of sofosbuvir and daclatasvir is safe and efficient in these patients. 61, 62, 63.

Effects of DAAs on other CYP substrates

Simeprevir and daclatasvir have no clinically relevant effects on CYP2C9, 2C19 and 2D6 50 as confirmed by their nonsignificant effect when coadministrated with escitalopram, dextrometorphan (substrates of CYP2D6) 32, 64, omeprazole (substrate of CYP2C19) and warfarin (substrate of CYP2C9) 32.

Ritonavir could induce CYP2C19 65. When omeprazole 40 mg once daily was coadministered with the 3D regimen in healthy volunteers, omeprazole AUC decreased by 38% due to ritonavir induction on CYP2C19, so it is recommended to monitor patients for decreased efficacy of all proton pump inhibitors 33 (Table 2). However, with sulfamethoxazole (substrate of CYP2C19) and trimethoprim, no dose adjustment is required 66.

The 3D regimen did not affect the exposures of the CYP2C9 substrates (such as warfarin) or the CYP1A2 substrates (such as theophylline and caffeine) or CYP2D6 substrates (such as duloxetine, desipramine). Therefore, these drugs are not expected to require dose adjustments 67.

Effect of CYP inducers or inhibitors on DAAs

The US Food and Drug Administration classification states that a drug is a powerful inhibitor (or inducer) of CYP if it increases (or decreases) substrate exposure by a factor of at least five 68. Strong inducers of CYP3A4 (e.g. rifampicin, carbamazepine) may decrease therapeutic effect of daclatasvir, simeprevir and 3D regimen. Thus in healthy subjects, administration of rifampin with simeprevir or with daclatasvir at 60 mg once daily led to a 48% decrease in simeprevir AUC 50 and a 79% decrease in daclatasvir AUC 18. 3D regimen was tested with carbamazepine, it resulted in paritaprevir AUC decrease by 70%, dasabuvir AUC by 70% and ombitasvir AUC by 30% respectively 33. Coadministration of daclatasvir or simeprevir or 3D regimen with a strong inducer is therefore not recommended. Likewise, the concomitant use of efavirenz with simeprevir or daclatasvir 60 mg induced a reduction of simeprevir AUC by 71% and of daclatasvir AUC by 22% 69, 70. An extrapolated daclatasvir dose of 90 mg with efavirenz is estimated to provide exposure similar to daclatasvir at 60 mg daily alone 71 and simeprevir and efavirenz should not be associated.

Efavirenz with 3D regimen resulted in alanine aminotransferase elevations and early discontinuation of the study. The association is contraindicated 72.

As expected, coadministration of sofosbuvir/ledipasvir and efavirenz did not induce a clinically significant effect on ledipasvir and sofosbuvir AUC 29, 73.

Strong inhibitors of CYP3A4 may increase the plasma levels of daclatasvir, simeprevir and 3D regimen. In healthy volunteers, erythromycin and simeprevir association increased AUC simeprevir by 647% and AUC erythromycin by 90%. 32. Ritonavir with simeprevir increases simeprevir AUC by 618% respectively 47, 70. Thus coadministration of simeprevir with any protease inhibitor is not recommended. Ketoconazole at 400 mg once a day with daclatasvir or 3D regimen increases daclatasvir AUC by 200% 18, paritaprevir AUC by 100%, ritonavir AUC by 57%, and dasabuvir AUC by 42% 74. The dose of daclatasvir should be decreased to 30 mg once daily if coadministered with ketoconazole and 3D regimen is contraindicated with all antifungal azoles (Table 7).

Table 7.

Drug–drug interactions between anti‐infective drugs and direct‐acting antiviral agents (DAAs)

| Drug | DAA | Type of patients | Pharmacological effect on DAA AUC (%) | Pharmacological effect on coadministered drug AUC (%) | Recommendations | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rifampicin | Daclatasvir | NA | ↓ –79% CYP3A4 induction by rifampicin | NA | Coadministration with rifampicin, rifabutin, rifapentine or other strong inducers of CYP3A4 is contraindicated. | 23 |

| Ledipasvir/ sofosbuvir | NA | ↓ C max −35% ↓ AUC −59% | NA | Not recommended. | 30 | |

| Simeprevir | Healthy volunteers | ↓: −48% | ↔ | Not recommended loss of therapeutic effect of simeprevir. | 50 | |

| Sofosbuvir | Healthy volunteers | Sofosbuvir ↓ –72% GS‐331 007: ↔ | NA | Decrease in sofosbuvir exposure is clinically significant and is likely to alter therapeutic effect; sofosbuvir should not be used with potent inducers of intestinal P‐gp. | 30, 31 | |

| 3D regimen | Not tested | Contraindicated. | 19 | |||

| Rifabutin | Daclatasvir | Not tested | Expected: ↓simeprevir (induction of CYP3A4 by rifabutin) | Coadministration of daclatasvir with rifampicin, rifabutin, rifapentine or other strong inducers of CYP3A4 is contraindicated. | 23 | |

| Ledipasvir/ sofosbuvir | Not tested | Expected: ↓ ledipasvir | Not recommended. May result in loss of therapeutic effect of ledipasvir. | 21 | ||

| Simeprevir | Not tested | Expected: ↓simeprevir (induction of CYP3A4 by rifabutin) | Not recommended. May result in loss of therapeutic effect of simeprevir. | 22 | ||

| Sofosbuvir | Not tested | Expected: ↓ sofosbuvir

↔ GS‐331 007 (Induction of P‐gp) |

Not recommended. May result in loss of therapeutic effect of sofosbuvir. | 37 | ||

| Ketoconazole | Daclatasvir | NA | AUC ↑: +200% (strong inhibition of CYP3A4 by krtoconazole) | NA | The dose of daclatasvir should be reduced to 30 mg once daily when coadministered with ketoconazole or other strong inhibitors of CYP3A4. | 23 |

| Ledipasvir/ sofosbuvir | Not tested | No data. | ||||

| Simeprevir | Not tested | Expected: ↑ simeprevir (strong CYP3A4 inhibition) | NA | Not recommended. | 22 | |

| Sofosbuvir | Not tested | No data. | ||||

| 3D regimen | ↔ ombitasvir

↑ paritaprevir (with dasabuvir): +98% ↑ paritaprevir (without dasabuvir): +116 ↑ dasabuvir: +42/% |

↑ +117% | Contraindicated. | 33 | ||

| Erythromycin | Daclatasvir | Not tested | Expected AUC ↑ (strong CYP3A4 inhibition by erythromycin) | Not recommended. Prefer azithromycin without dose adjustment. | 23 | |

| Ledipasvir/ sofosbuvir | Not tested | No data. | ||||

| Simeprevir | Healthy volunteers | ↑ + 647% (strong CYP3A4 inhibition) | ↑ +90% | Not recommended. Prefer azithromycin without dose adjustment. | 32 | |

| Sofosbuvir | Not tested | No data. | ||||

| 3D regimen | Not tested | Expected: ↑paritaprevir

↑ dasabuvir (strong CYP3A4 inhibition by erythromycin) |

Expected ↑ (CYP3A4 and P‐gp inhibition by paritaprevir, ritonavir, dasabuvir) | Caution is advised. | 32 |

↔, no clinical change (< 25%); ↑, increase in AUC; ↓, decrease in AUC

AUC, area under the curve; NA, not applicable; P‐gp, P‐glycoprotein

Daclatasvir, simeprevir or paritaprevir coadministration with cyclosporine (a CYP3A4 inhibitor) resulted in daclatasvir, simeprevir and paritaprevir AUC increase (40%, 481% and 72%) 19, 53, 59. No dose adjustment of antiviral is required except for simeprevir, coadministration of which is contraindicated 45, 49, 75.

Dasabuvir is a substrate of CYP2C8: in the presence of gemfibrozil (CYP2C8 inhibitor), dasabuvir AUC increased by 1030%, so gemfibrozil is contraindicated with 3D regimen 19.

Other drugs were tested with simeprevir, sofosbuvir, ledipasvir, daclatasvir and 3D regimen 76, 77, 78, 79, 80, 81, 82: data available are appended in supporting information (Tables S1, S2, S3, S4, S5 published online). Treatment with daclatasvir, simeprevir, sofosbuvir/ledipasvir is associated with a low potential for serious DDI. However, moderate DDI are frequent and have to be considered 73, 83. Polepally et al. have studied the effects of more than 120 comedications with the 3D regimen. Despite of an apparent effect on paritaprevir exposure, no dose adjustment of 3D regimen was necessary 80, 81. In HIV‐coinfected patients, addition of sofosbuvir‐containing therapy is associated with a lower DDI prevalence than a simeprevir‐containing therapy 86, 87 (Table 8). Sofosbuvir and daclatasvir are ideally suited for HCV/HIV‐coinfected patients, whereas simeprevir with sofosbuvir is recommended for HCV‐monoinfected patients 88, 89, 90, 91. 3D regimen has a highest potential of DDI and comedication should be analysed carefully before initiating HCV treatment 87, 92.

Table 8.

Drug–drug interactions between direct‐acting antiviral agents (DAAs) and antiretrovirals

| Drug | DAA | Type of patients | Pharmacological effect on DAA AUC | Pharmacological effect on coadministered drug AUC | Recommendations | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Efavirenz | Daclatasvir | Healthy subjects | AUC ↓ –32% | ↔ | An extrapolated daclatasvir dose of 90 mg with efavirenz is estimated to provide exposures similar to daclatasvir at 60 mg daily alone. | 116 |

| Ledipasvir/ sofosbuvir | Not tested | Expected: ↔ | Expected: ↔ | No dose adjustment. | 29 | |

| Simeprevir | Healthy subjects | AUC ↓ –71% | ↔ | Avoid coadministration of simeprevir and efavirenz. | 69 | |

| Sofosbuvir | Not tested | No data. | ||||

| 3 Regimen | Not tested | Contraindicated (adverse effect with efavirenz/emtricitabine/tenofovir). | 46 | |||

| Raltegravir | Daclatasvir | HIV/HCV coinfected patient | No clinically relevant drug interaction. | 93 | ||

| Ledipasvir/ sofosbuvir | Healthy subjects | ↔ | ↔ | No dose adjustment of raltegravir or ledispavir is required. | 29 | |

| Simeprevir | Healthy subjects | ↔ | ↔ | No dose adjustments. | 69 | |

| Sofosbuvir | Healthy subjects | ↔ sofosbuvir ↔ GS‐33 100 | ↔ | No dose adjustment of sofosbuvir or raltegravir. | 73 | |

| 3D regimen | With dasabuvir

↑raltegravir: +134% Without dasabuvir ↑raltegravir: + 20% |

No dose adjustment. | 46 | |||

| Rilpivirin | Daclatasvir | Not tested | Not expected. No dose adjustment. | 23 | ||

| Ledipasvir/ sofosbuvir | Not tested | Expected: ↔ | Expected: ↔ | Not expected. | 21 | |

| Simeprevir | Healthy subjects | ↔ | ↔ | Not considered clinically significant. No dose adjustments. | 69 | |

| Sofosbuvir | Healthy subjects | ↔ sofosbuvir ↔ GS‐331 007 | ↔ | Not considered clinically significant. No dose adjustments. | 73 | |

| 3D regimen | ↔ ombitasvir

↑ Paritaprevir +23% ↔ dasabuvir |

↑ +225% | Not recommended. If the combination is used, repeated ECG‐monitoring should be done. | 46 | ||

| Ritonavir | Daclatasvir | Not tested | Expected: daclatasvir ↑ Inhibition of CYP3A4 by ritonavir | Dose of daclatasvir should be reduced to 30 mg with strong inhibitors of CYP3A4. | 23 | |

| Ledipasvir/ sofosbuvir | Not tested | Not expected. | 21 | |||

| Simeprevir | Healthy subjects | ↑ +618% | ↑ +32% | It is not recommended to coadminister simeprevir with ritonavir, boosted or unboosted HIV protease inhibitors. | 50 | |

| Sofosbuvir | Not tested | ↔ | Not expected. | 37 | ||

| Tenofovir | Daclatasvir | Healthy subjects | ↔ | ↔ | No dose adjustment is required with coadministration. | 115 |

| Simeprevir | Healthy subjects | ↔ | ↔ | No dose adjustments are required. | 69 | |

| Sofosbuvir | Not tested | No data. | 37 | |||

| Tenofovir/ emtricitabine | 3d regimen | ↔ ombitasvir

↔ paritaprevir with dasabuvir: ↔ paritaprevir without dasabuvir: ↔ dasabuvir |

↔ emtricitabine ↔ tenofovir | No dose adjustment. | 46 | |

| Abacavir/lamivudine | Daclatasvir | Not tested | Not expected. No dose adjustment. | 23 | ||

| Simeprevir | Not tested | Not expected. No dose adjustment. | 22 | |||

| Ledipasvir/ sofosbuvir | Healthy subjects | ↔ ledipasvir

↔ sofosbuvir ↔ GS‐331 007 |

↔ abacavir ↔ lamivudine | No dose adjustment is required. | 21 | |

| Ombitasvir/ paritaprevir/ ritonavir / dasabuvir | Healthy subjects | ↔ ombitasvir

↔ paritaprevir with dasabuvir ↔ paritaprevir without dasabuvir ↔ dasabuvir |

↔ abacavir ↔ lamivudine | No dose adjustment. | 117 | |

| Darunavir/ritonavir | Daclatasvir | HIV/HCV | ↔ daclatasvir | ↔ darunavir | No dose adjustment. | 90, 118 |

| Ledipasvir/ sofosbuvir | Healthy subjects | ↑ledipasvir: +39% | ↔ darunavir | No dose adjustment of ledipasvir/ sofosbuvir or darunavir (ritonavir boosted). | 21 | |

| Simeprevir | Healthy subjects | ↑ +159% | ↔ darunavir ↑ritonavir +32% | It is not recommended to coadminister simeprevir with ritonavir, boosted or unboosted HIV protease inhibitors. | 119 | |

| Sofosbuvir | Healthy subjects | ↑ sofosbuvir + 34% ↔ GS‐331 007 | ↔ darunavir ↔ ritonavir: | These changes are not considered clinically significant and doseadjustments are not warranted. | 73 | |

| Darunavir alone | 3D regimen | Healthy subjects | ↓ombitasvir: – 27%

↓paritaprevir: – 41% ↓dasabuvir: –27% |

↔ darunavir | Not considered clinically significant. No dose adjustment. | 19, 46 |

| Lopinavir/ritonavir | Daclatasvir | Healthy subjects | NS | Not studied | No dose adjustment. | 97 |

| Ledipasvir/ sofosbuvir | Not tested | Expected: AUC ↑ (P‐gp inhibition by lopinavir) | No data. | 21 | ||

| Sofosbuvir | Not tested | Expected: AUC ↑ (P‐gp inhibition by lopinavir) | No data. | 37 | ||

| Simeprevir | Not tested | Expected: AUC ↑ | Not recommended. | 22 | ||

| 3D regimen | ↔ ombitasvir ↑ paritaprevir with dasabuvir: +117%

↑ paritaprevir (without dasabuvir): ↑ +510% ↔ dasabuvir |

↔ lopinavir | Contraindicated. | 46 | ||

| Atazanavir/ ritonavir | Daclatasvir | Healthy subjects | ↑ + 110% | ↔ | An extrapolated daclatasvir dose of 30 mg with atazanavir/ ritonavir is estimated to provide exposures similar to daclatasvir at 60 mg daily alone. | 116 |

| Ledipasvir/ sofosbuvir | Healthy subjects | ↑ ledipasvir +113%

↔ sofosbuvir ↔ GS‐331 007 |

↔ atazanavir | No dose adjustment of ledipasvir/ sofosbuvir or atazanavir (ritonavir boosted) is required. | 21 | |

| Simeprevir | Not tested | Expected: ↑ AUC simeprevir (CYP3A4 enzyme inhibition by ritonavir) | It is not recommended to coadminister simeprevir with any HIV PI, with or without ritonavir. | 22 | ||

| Atazanavir alone | 3D regimen | Healthy subjects | ↔ ombitasvir

↑ paritaprevir with dasabuvir: + 94% ↑paritaprevir without dasabuvir +187% ↔ dasabuvir |

↔ atazanavir | No dose adjustment needed for ombitasvir/ paritaprevir/ ritonavir with dasabuvir and atazanavir alone. Treatment with atazanavir + Ombitasvir/ paritaprevir/ ritonavir without dasabuvir is not recommended. | 46 |

| Atazanavir ritonavir + emtricitabine/ tenofovir disoproxil fumarate / | Daclatasvir | Not tested | Expected AUC daclatasvir ↑ (CYP3A4 enzyme inhibition by ritonavir) | Not recommended. | 23 | |

| Ledipasvir/ sofosbuvir | Healthy subjects | ↑ ledipasvir: +96%

↔ sofosbuvir ↔ GS‐331 007 |

↔ AUC atazanavir

↑ C

min + 63% ↔ AUC ritonavir ↑ C min + 45% ↔Emtricitabine ↑ tenofovir +35% C min+ 47% |

Ledipasvir–sofosbuvir increased the concentration of tenofovir. The combination should be used with caution with frequent renal monitoring. Atazanavir concentrations are also increased, with a risk for an increase in bilirubin levels/icterus. | 120 | |

| Simeprevir | Not tested | Expected: AUC simeprevir↑ (CYP3A4 enzyme inhibition) | It is not recommended to coadminister simeprevir with any HIV PI, with or without ritonavir. | 22 | ||

| 3D regimen | Discontinued due to adverse effect | Contraindicated (alanine amino transferase elevation). | 19, 46 | |||

| Darunavir / ritonavir + emtricitabine/ tenofovir disoproxil fumarate | Daclatasvir | Not tested | Expected AUC daclatasvir ↑ (CYP3A4 enzyme inhibition by ritonavir) | Not recommended. | 23 | |

| Ledipasvir/ sofosbuvir | Healthy subjects | ↔ ledipasvir ↔ sofosbuvir ↔ GS‐331 007 | ↔ darunavir

↔ ritonavir ↔ emtricitabine ↑ tenofovir +50% |

Ledipasvir‐sofosbuvir is expected to increase the concentration of tenofovir. The combination should be used with caution with frequent renal monitoring, if other alternatives are not available. | 21 | |

| Simeprevir | Not tested | Expected: simeprevir ↑ (CYP3A4 enzyme inhibition) | It is not recommended to coadminister simeprevir with any HIV PI, with or without ritonavir. | 22 | ||

| 3D regimen | Not tested | Not recommanded with association with ritonavir. | 19 | |||

| Efavirenz, tenofovir, emtricitabine | Daclatasvir | Not tested | Expected: AUC daclatasvir ↓ (CYP3A4 induction by efavirenz) | Increase the dose of daclatasvir to 90 mg. | 23 | |

| Ledipasvir/ sofosbuvir | Healthy subjects | ↓ledipasvir: −34%

↔ sofosbuvir ↔ GS‐331 007 |

↔ efavirenz

↔ emtricitabine ↑ tenofovir: +98% |

No dose adjustment of ledipasvir‐sofosbuvir or emtricitabine/ rilpivirine/ tenofovir disoproxil fumarate is required. | 29 | |

| Simeprevir | Not tested | Expected: AUC simeprevir ↓ CYP3A4 induction by efavirenz | Not recommended. | 22 | ||

| Sofosbuvir | Healthy subjects | ↔ sofosbuvir ↔ GS‐331 007 | ↔ tenofovir

↔ emtricitabine ↔ efavirenz |

No dose adjustments. | 73 | |

| Ombitasvir/ paritaprevir/ ritonavir / dasabuvir | Discontinuated due to adverse effect | Contraindicated. | 19 | |||

| Emtricitabine/ rilpivirine/ tenofovir disoproxil fumarate | Daclatasvir | Not tested | Not expected. No dose adjustment. | 23 | ||

| Ledipasvir/ sofosbuvir | Healthy subjects | ↔ ledipasvir

↔ sofosbuvir ↔ GS‐331 007 |

↔ emtricitabine

↔ rilpivirine ↑ tenofovir +40% |

No dose adjustment of ledapasvir‐sofosbuvir or emtricitabine/rilpivirine/ tenofovir disoproxil fumarate is required. | 29 | |

| Simeprevir | Not tested | Not expected. No dose adjustment. | 22 | |||

| Ombitasvir/ paritaprevir/ ritonavir / dasabuvir | Not tested | Expected: ↑ rilpivirin ↔ tenofovir ↔ emtricitabine | Not recommended. Monitore ECG. | 19 | ||

| Elvitegravir/ cobicistat/ emtricitabine/ tenofovir disoproxil fumarate | Daclatasvir | Not tested | Expected: daclatasvir ↑ (CYP3A4 inhibition by cobicistat) | The dose of daclatasvir should be reduced to 0 mg once daily when coadministered with cobicistat or other strong inhibitors of CYP3A4. | 18 | |

| Ledipasvir/ sofosbuvir | Healthy subjects | ↑ ledipasvir +78%

↑ sofosbuvir + 36% ↑ GS‐331 007 + 44% |

↔ elvitegravir

↑ cobicistat: +59% tenofovir not studied |

Ledapasvir‐sofosbuvir is expected to increase tenofovir exposure. The combination should be used with caution with frequent renal monitoring, if other alternatives are not available. | 121 | |

| Simeprevir | Not tested | Expected AUC simeprevir ↑ (CYP3A4 inhibition by cobicistat) | Not recommended. | 22 | ||

| 3D regimen | Not tested | Expected:

↑ ombitasvir ↑ paritaprevir ↑ dasabuvir |

Contraindicated. | 19 |

↔, no clinical change (< 25%); ↑, increase in AUC; ↓, decrease in AUC.

AUC, area under the curve; HCV, hepatitis C virus; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; NA, not applicable

Other factors influencing the metabolism of DAAs: UGTA1 enzyme

UDP‐glucuronosyltransferase (UGT) enzymes catalyse the conjugation of endogenous substances such as bilirubin and exogenous drugs. Sofosbuvir, ledipasvir, simeprevir and daclatasvir were tested with raltegravir, whose metabolism depends on UGTA1 enzyme: no clinically significant pharmacokinetic changes were observed, and no dose adjustments are needed 42, 69, 73, 93. Paritaprevir, ombitasvir and dasabuvir are inhibitors of UGT1A1 so coadministration with raltegravir increase raltegravir AUC by 134%. 3D regimen is contraindicated with norgestimate/ethynylestradiol because of an increase of norgestrel and norgestromine by 164 and 160% respectively 33.

Elimination

Only competition in the urinary excretion of a drug causes a risk of clinically significant DDI. Elimination of simeprevir, ledipasvir daclatasvir and 3D regimen occurs mainly via biliary excretion. Sofosbuvir is eliminated at the rate of approximately 80%, 14% and 2.5% in urine, faeces and expired air, respectively 37. Most of the sofosbuvir dose recovered in urine was GS‐331 007 (78%). As GS‐331 007 is an inactive metabolite, a competition with another drug mainly eliminated by the kidneys could lead to an overdosage of sofosbuvir 94. A small study in HCV patients with severe renal impairment showed that low dose of sofosbuvir (200 mg) with ribavirin at 200 mg once daily resulted in comparable sofosbuvir and approximately four‐fold higher GS‐331 007 exposures compared with sofosbuvir at 400 mg. The treatment was safe and well‐tolerated 95, 96.

Conclusion

DDIs can occur at several steps during drug metabolism. Food can play a role in the absorption of DAAs. Transporters and cytochromes are mainly responsible for clinically significant interactions. Sofosbuvir is less prone to DDIs, because its metabolism does not depend on cytochromes. Online tools can be helpful, but clinicians should also run a checklist of key questions before beginning a HCV treatment, such as:

Does the liver metabolise the coadministered drug? If so, are they substrates inhibitors or inducers of P‐gp, OATP or CYP3A4 or other transporters?

Is the patient taking drugs with a narrow therapeutic range? Is it possible to monitor the drug?

Should a substitution be considered? How?

The selected treatment will need to be regularly re‐assessed jointly with the pharmacist in an effort to minimise potential interactions and provide therapeutic alternatives.

Competing Interests

All authors have completed the Unified Competing Interest form at http://www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available on request from the corresponding author) and declare no support from any organisation for the submitted work. A. Abergel has received speaking and teaching fees from Abbvie, Bristol‐Myers Squibb, Gilead Sciences, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, and Merck Sharp & Dohme (MSD); grant and research support from Abbvie, Bristol‐Myers Squibb, Gilead Sciences, and MSD; and he has served on advisory boards for Abbvie, Bristol‐Myers Squibb, Gilead Sciences, and MSD in the previous 3 years; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Guarantor of the article: Dr Sarah Talavera Pons.

Contributors

F.T.C. collected the data; S.T.P. and A.A. contributed to literature searching, reviewing, and writing the paper; A.B., V.S., P.C. and G.L. corrected the paper; A.A. supervised the topic. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Supporting information

Table S1 Drug–drug interactions with sofosbuvir.

Table S2 Drug–drug interactions with simeprevir.

Table S3 Drug–drug interactions with daclatasvir.

Table S4 Drug–drug interactions with ledipasvir/sofosbuvir.

Table S5 Drug–drug interactions with 3D regimen.

Supporting info item

Talavera Pons, S. , Boyer, A. , Lamblin, G. , Chennell, P. , Châtenet, F. ‐T. , Nicolas, C. , Sautou, V. , and Abergel, A. (2017) Managing drug–drug interactions with new direct‐acting antiviral agents in chronic hepatitis C. Br J Clin Pharmacol, 83: 269–293. doi: 10.1111/bcp.13095.

References

- 1. Southan C, Sharman JL, Benson HE, Faccenda E, Pawson AJ, Alexander SP, et al. The IUPHAR/BPS Guide to PHARMACOLOGY in 2016: towards curated quantitative interactions between 1300 protein targets and 6000 ligands. Nucl Acids Res 2016; 44: D1054–D1068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Alexander SPH, Fabbro D, Kelly E, Marrion N, Peters JA, Benson HE, et al The Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2015/16: Enzymes. Br J Pharmacol 2015; 172: 6024–60109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Alexander SPH, Fabbro D, Kelly E, Marrion N, Peters JA, Benson HE, et al. The Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2015/16: Transporters. Br J Pharmacol 2015; 172: 6110–6202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Pearlman BL, Ehleben C, Perrys M. The combination of simeprevir and sofosbuvir is more effective than that of peginterferon, ribavirin, and sofosbuvir for patients with hepatitis C‐related Child's class A cirrhosis. Gastroenterology 2015; 148: 762–770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Höner Z, Siederdissen C, Maasoumy B, Deterding K, Port K, Sollik L, et al. Eligibility and safety of the first interferon‐free therapy against hepatitis C in a real‐world setting. Liver Int 2015; 35: 1845–1852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Peter J, Nelson DR. Optimal interferon‐free therapy in treatment‐experienced chronic hepatitis C patients. Liver Int 2015; 35 (Suppl. 1): 65–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Muir AJ. The rapid evolution of treatment strategies for hepatitis C. Am J Gastroenterol 2014; 109: 628–635. quiz 36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Furihata T, Matsumoto S, Fu Z, Tsubota A, Sun Y, Matsumoto S, et al. Different interaction profiles of direct‐acting anti‐hepatitis C virus agents with human organic anion transporting polypeptides. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2014; 58: 4555–4564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kiser JJ, Burton JR, Everson GT. Drug–drug interactions during antiviral therapy for chronic hepatitis C. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2013; 10: 596–606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lauffenburger JC, Mayer CL, Hawke RL, Brouwer KL, Fried MW, Farley JF. Medication use and medical comorbidity in patients with chronic hepatitis C from a US commercial claims database: high utilization of drugs with interaction potential. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2014; 26: 1073–1082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Maasoumy B, Port K, Calle Serrano B, Markova AA, Sollik L, Manns MP, et al. The clinical significance of drug–drug interactions in the era of direct‐acting anti‐viral agents against chronic hepatitis C. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2013; 38: 1365–1372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Talavera Pons S, Lamblin G, Boyer A, Sautou V, Abergel A. Drug interactions and protease inhibitors used in the treatment of hepatitis C: how to manage? Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2014; 70: 775–789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ouwerkerk‐Mahadevan S, Simion A, Mortier S, Peeters M, Beaumont‐Mauviel M. The effect of food and different meal types on the bioavailability of simeprevir (TMC435), an HCV protease inhibitor in clinical development. [poster no. 0_20] [Abstract presented at the 8th international workshop on clinical pharmacology of hepatitis therapy]. Cambridge, MA, 2013.

- 14. Kirby B, Gordi T, Symonds WT, Kearney BP, Mathias A. Population pharmacokinetics of sofosbuvir and its major metabolite (GS‐331007) in healthy and HCV‐infected adult subjects. [Abstract presented at the 64th Annual Meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases]. Washington, DC, 2013.

- 15. Kirby BJ, Symonds WT, Kearney BP, Mathias AA. Pharmacokinetic, pharmacodynamic, and drug‐interaction profile of the hepatitis C virus NS5B polymerase inhibitor sofosbuvir. Clin Pharmacokinet 2015; 54: 677–690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. German P, Yang J, West S, Han L, Sajwani K, Mathias A. Effect of food and acid reducing agents on the relative bioavailability and pharmacokinetics of ledipasvir/sofosbuvir fixed dose combination tablet. [Abstract P_15] [Abstract presented at the 15th International Workshop on Clinical Pharmacology of HIV and Hepatitis Therapy]. Washington, DC, 2014.

- 17. Terrault N, Zeuzem S, Di Bisceglie AM, Lim JK, Pockros PJ, Frazier LM, et al Treatment outcomes with 8, 12 and 24 week regimens of ledipasvir/sofosbuvir for the treatment of hepatitis C infection: analysis of a multicenter prospective, observational study. [Abstract presented at the 66th Annual Meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD)]. Boston, MA, 2015.

- 18. Eley T, You X, Wang R, Luo W‐L, Huang S, Kandoussi H, et al Daclatasvir: overview of drug–drug interactions with antiretroviral agents and other common concomitant drugs [Abstract presented at the HIV DART]. Miami, FL, 2014.

- 19. Abbvie Corporation . Viekira Pak (ombitasvir, paritaprevir and ritonavir tablets; dasabuvir tablets) Prescribing Information. North Chicago, IL December, 2014. In.

- 20. Menon RM, Klein CE, Lawal AL, Lawal A, Chiu YL, Awni WM, et al Pharmacokinetics, safety and tole rability of the HCV protease inhibitor ABT‐450 with ritonavir following multiple ascending doses in healthy adult volunteers. [abstract 58] [Abstract presented at the HepDART]. Hawaii, USA, 2009.

- 21. Gilead . Harvoni (sofosbuvir/ledipasvir) Summary of Product Characteristics. European Union 2014.

- 22. Janssen‐Cilag . Olysio (simeprevir) Summary of Product Characteristics. European Union 2014.

- 23. Bristol‐Myers‐Squibb . Daklinza (daclatasvir) Summary of Product Characteristics. European Union 2014.

- 24. Benet LZ, Hoener B‐A. Changes in plasma protein binding have little clinical relevance. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2002; 71: 115–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lin JH, Yamazaki M. Role of P‐glycoprotein in pharmacokinetics: clinical implications. Clin Pharmacokinet 2003; 42: 59–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Zamek‐Gliszczynski MJ, Chu X, Polli JW, Paine MF, Galetin A. Understanding the transport properties of metabolites: case studies and considerations for drug development. Drug Metab Dispos 2014; 42: 650–664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. König J, Müller F, Fromm MF. Transporters and drug–drug interactions: important determinants of drug disposition and effects. Pharmacol Rev 2013; 65: 944–966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Huisman MT, Snoeys J, Monbaliu J, Martens M, Sekar V, Raoof A. In vitro studies investigating the mechanism of interaction between TMC435 and hepatic transporters. [Poster 278] [Abstract presented at the 61st Annual Meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD)]. Boston, USA, 2010.

- 29. German P, Pang P, West S, Han L, Sajwani K, Mathias A. Drug interactions between direct acting anti‐HCV antivirals sofosbuvir and ledipasvir and HIV antiretrovirals. [abstract O_06] [Abstract presented at the 15th International Workshop on Clinical Pharmacology of HIV and Hepatitis Therapy.]. Washington, DC, 2014.

- 30. German P, Pang P, Fang L, Chung D, Mathias A. Drug–drug interaction profile of the fixed‐dose combination tablet ledipasvir/sofosbuvir. [Abstract 1976] [Abstract presented at the 65th Annual Meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD)]. Boston, MA, 2014.

- 31. Garrison K, Wang Y, Brainard D. The effect of rifampin on the pharmacokinetics of sofosbuvir in healthy volunteers. [abstract 992] [Abstract presented at the 65th Annual Meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD)]. Boston, MA, 2014.

- 32. Ouwerkerk‐Mahadevan S, Simion A, Peeters M, Beaumont M. Summary of pharmacokinetic drug–drug interactions for simeprevir (TMC435), a hepatitis C virus Ns3/4 A protease inhibitor. [abstract PE 10/7] [Abstract presented at the 14th European AIDS Conference]. Brussels, Belgium, 2013.

- 33. Menon RM, Badri PS, Wang T, Polepally AR, Zha J, Khatri A, et al. Drug–drug interaction profile of the all‐oral anti‐hepatitis C virus regimen of paritaprevir/ritonavir, ombitasvir, and dasabuvir. J Hepatol 2015; 63: 20–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kis O, Robillard K, Chan GNY, Bendayan R. The complexities of antiretroviral drug–drug interactions: role of ABC and SLC transporters. Trends Pharmacol Sci 2010; 31: 22–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Neuvonen PJ, Niemi M, Backman JT. Drug interactions with lipid‐lowering drugs: mechanisms and clinical relevance. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2006; 80: 565–581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Lee CA, O'Connor MA, Ritchie TK, Galetin A, Cook JA, Ragueneau‐Majlessi I, et al. Breast cancer resistance protein (ABCG2) in clinical pharmacokinetics and drug interactions: practical recommendations for clinical victim and perpetrator drug–drug interaction study design. Drug Metab Dispos 2015; 43: 490–509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Gilead . Sovaldi (sofosbuvir) Summary of Product Characteristics. European Union 2014.ldi. In.

- 38. Levêque D, Lemachatti J, Nivoix Y, Coliat P, Santucci R, Ubeaud‐Séquier G, et al. Mécanismes des interactions médicamenteuses d'origine pharmacocinétique. Rev Med Interne 2010; 31: 170–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Denning J, Cornpropst M, Clemons D, Fang L, Sale M, Berrey MM, et al Lack of effect of the nucleotide analog polymerase inhibitor PSI‐7977 on methadone pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics. [abstract 372] [Abstract presented at the 62nd Annual Meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD)]. San Francisco, USA, 2011.

- 40. Mathias A, Cornpropst M, Clemons D, Denning J, Symonds WT. No clinically significant pharmacokinetic drug–drug interactions between sofosbuvir (GS‐7977) and the immuno suppressants, cyclosporine A or tacrolimus in healthy volunteers. [abstract 1869] [Abstract presented at the 63rd Annual Meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD)]. Boston, MA, 2012.

- 41. De Kanter CTMM, Drenth JPH, Arends JE, Reesink HW, Van Der Valk M, De Knegt RJ, et al. Viral hepatitis C therapy: pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic considerations. Clin Pharmacokinet 2014; 53: 409–427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. German P, Moorehead L, Pang P, Vimal M, Mathias A. Lack of a clinically important pharmacokinetic interaction between sofosbuvir or ledipasvir and hormonal oral contraceptives norgestimate/ethinyl estradiol in HCV‐uninfected female subjects. J Clin Pharmacol 2014; 54: 1290–1298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Charlton M, Gane E, Manns MP, Brown RS, Curry MP, Kwo PY, et al. Sofosbuvir and ribavirin for treatment of compensated recurrent hepatitis C virus infection after liver transplantation. Gastroenterology 2015; 148: 108–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Reddy KR, Everson GT, Flamm SL, Denning JM, Arterburn S, Brandt‐Sarif T, et al Ledipasvir/sofosbuvir with ribavirin for the treatment of HCV in patients with post transplant recurrence: preliminary results of a prospective, multicenter study. [abstract 8] [Abstract presented at the 65th Annual Meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD)]. Boston, MA, 2014.

- 45. Campos‐Varela I, Peters MG, Terrault NA. Advances in therapy for HIV/hepatitis C virus‐coinfected patients in the liver transplant setting. Clin Infect Dis 2015; 60: 108–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Khatri A, Wang T, Wang H, Podsadecki TJ, Trinh R, Awni WM, et al Drug–drug interactions of the direct acting antiviral regimen of ABT‐450/r, ombitasvir and dasabuvir with HIV protease inhibitors. [abstract V‐484] [Abstract presented at the 54th Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy (ICAAC)]. Washington, DC, 2014.

- 47. Badri P, Dutta S, Coakley E, Cohen D, Ding B, Podsadecki T, et al. Pharmacokinetics and dose recommendations for cyclosporine and tacrolimus when coadministered with ABT‐450, ombitasvir, and dasabuvir. Am J Transplant 2015; 15: 1313–1322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Kwo PY, Mantry P, Coakley EP, Te H, Vargas H, Brown RS, et al Results of the phase 2 study M12‐999: interferon‐free regimen of ABT‐450/R/ABT‐267 + ABT‐333 + ribavirin in liver transplant recipients with recurrent HCV genotype 1 infection. [abstract O114] [Abstract presented at the 49th Annual Meeting of the European Association for the Study of the Liver (ILC)]. London, UK, 2014.

- 49. Dick TB, Lindberg LS, Ramirez DD, Charlton MRA. clinician's guide to drug–drug interactions with direct‐acting antiviral agents for the treatment of hepatitis C viral infection. Hepatology 2016; 63: 634–643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Sekar V, Verloes R, Meyvisch P, Spittaels K, Akuma SH, Smedt GD. Evaluation of metabolic interactions for TMC435 via cytochrome P450 (CYP) enzymes in healthy volunteers. [abstract 1076] [Abstract presented at the 45th annual meeting of the European Association for the Study of the Liver (ILC)]. Vienna, Austria, 2010.

- 51. Ouwerkerk‐Mahadevan S, Simion A, Mortier S. No clinically significant interaction between the investigational HCV protease inhibitor simeprevir (TMC435) and the mmunosuppressive agents cyclosporine and tacrolimus. [abstract 80] [Abstract presented at the 63rd Annual Meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD)]. Boston, MA, 2012.

- 52. Ueda Y, Kaido T, Uemoto S. Fluctuations in the concentration/dose ratio of calcineurin inhibitors after simeprevir administration in patients with recurrent hepatitis C after liver transplantation. Transpl Int 2015; 28: 251–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Ouwerkerk‐Mahadevan S, Vanwelkenhuysen I, Peeters M, Simonts M, Ilsbroux I, Simion A, et al Significant drug–drug interaction between simeprevir and cyclosporine a but not tacrolimus in patients with recurrent chronic HCV infection after orthotopic liver transplantation: the SATURN study. [poster P0834] [Abstract presented at the 50th annual meeting of the European Association for the Study of the Liver (ILC)]. Vienna, Austria, 2015.

- 54. Tanaka T, Sugawara Y, Akamatsu N, Kaneko J, Tamura S, Aoki T, et al. Use of simeprevir following pre‐emptive pegylated interferon/ribavirin treatment for recurrent hepatitis C in living donor liver transplant recipients: a 12‐week pilot study. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci 2015; 22: 144–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Coilly A, Roche B, Duclos‐Vallée J‐C, Samuel D. Optimal therapy in hepatitis C virus liver transplant patients with direct acting antivirals. Liver Int 2015; 35 (Suppl. 1): 44–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Wendt A, Adhoute X, Castellani P, Oules V, Ansaldi C, Benali S, et al. Chronic hepatitis C: future treatment. Clin Pharmacol 2014; 6: 1–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Dumortier J, Botta‐Fridlund D, Coilly A, Leroy V, Fougerou‐Leurent C, Danjou H, et al Treatment of severe HCV‐recurrence after liver transplantation using sofosbuvir‐based regimens: the ANRS CO23 CUPILT study. [abstract O109] [Abstract presented at the 50th annual meeting of the European Association for the Study of the Liver (ILC)]. Vienna, Austria, 2015.

- 58. Johnson H, Lichvar AB, Rustgi VK. The effect of ledipasvir/sofosbuvir on dose‐normalized levels of immunosuppression in liver transplant recipients. [abstract 1741] [Abstract presented at the 66th Annual Meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD)]. San Francisco, CA, 2015.

- 59. Bifano M, Adamczyk R, Hwang C, Kandoussi H, Marion A, Bertz R. Daclatasvir pharmacokinetics in healthy subjects: no clinically‐relevant drug–drug interactions with either cyclosporine or tacrolimus. [abstract 1081] [Abstract presented at the 64th Annual Meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD)]. Washington, DC, 2013.

- 60. Bifano M, Adamczyk R, Hwang C, Kandoussi H, Marion A, Bertz RJ. An open‐label investigation into drug–drug interactions between multiple doses of daclatasvir and single‐dose cyclosporine or tacrolimus in healthy subjects. Clin Drug Investig 2015; 35: 281–289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Fontana RJ, Hughes EA, Bifano M, Appelman H, Dimitrova D, Hindes R, et al. Sofosbuvir and daclatasvir combination therapy in a liver transplant recipient with severe recurrent cholestatic hepatitis C. Am J Transplant 2013; 13: 1601–1605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Pellicelli AM, Montalbano M, Lionetti R, Durand C, Ferenci P, D'Offizi G, et al. Sofosbuvir plus daclatasvir for post‐transplant recurrent hepatitis C: potent antiviral activity but no clinical benefit if treatment is given late. Dig Liver Dis 2014; 46: 923–927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Coilly A, Fougerou C, Ledinghen VD, Houssel‐Debry P, Duvoux C, Martino VD, et al The association of sofosbuvir and daclatasvir for treating severe recurrence of HCV infection after liver transplantation: Results from a large french prospective multicentric ANRS CO23 CUPILT cohort. [abstract G15] [Abstract presented at the 50th annual meeting of the European Association for the study of the liver (ILC)]. Vienna, Austria, 2015.

- 64. Ouwerkerk‐Mahadevan S, Beumont M, Peeters M, Spittaels K, Sekar V. The pharmacokinetic interaction between the investigational NS3/4 A HCV protease inhibitor TMC435 and escitalopram. [abstract 1354] [Abstract presented at the 63rd Annual Meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD)]. Boston, MA, 2012.

- 65. Foisy MM, Yakiwchuk EM, Hughes CA. Induction effects of ritonavir: implications for drug interactions. Ann Pharmacother 2008; 42: 1048–1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Polepally AR, Jennifer K, Ding B, Shuster D, Dumas E, Khatri A, et al Drug–drug interactions of commonly used medications with direct acting antiviral HCV combination therapy of paritaprevir/r, ombitasvir and dasabuvir. [abstract 16] [Abstract presented at the 16th International Workshop on Clinical Pharmacology of HIV & Hepatitis Therapy]. Washington, DC, 2015.

- 67. Badri PS, Dutta S, Wang H, Podsadecki TJ, Polepally AR, Khatri A, et al. Drug interactions with the direct‐acting antiviral combination of ombitasvir and paritaprevir‐ritonavir. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2015; 60: 105–114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Huang SM, Temple R, Throckmorton DC, Lesko LJ. Drug interaction studies: study design, data analysis, and implications for dosing and labeling. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2007; 81: 298–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Ouwerkerk‐Mahadevan S, Sekar V, Peeters M, Beaumont‐Mauviel M. The pharmacokinetic interactions of HCV protease inhibitor TMC435 with rilpivirine, tenofovir, efavirenz or raltegravir in healthy volunteers. [abstract 49] [Abstract presented at the 19th Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (CROI)]. Seattle, WA, 2012.

- 70. Karageorgopoulos DE, El‐Sherif O, Bhagani S, Khoo SH. Drug interactions between antiretrovirals and new or emerging direct‐acting antivirals in HIV/hepatitis C virus coinfection. Curr Opin Infect Dis 2014; 27: 36–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Bifano M, Hwang C, Oosterhuis B, Hartstra J, Grasela D, Tiessen R, et al. Assessment of pharmacokinetic interactions of the HCV NS5A replication complex inhibitor daclatasvir with antiretroviral agents: ritonavir‐boosted atazanavir, efavirenz and tenofovir. Antivir Ther 2013; 18: 931–940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Menon RM. Ombitasvir/paritaprevir/ritonavir + dasabuvir: drug interactions with antiretroviral agents. [Abstract presented at the 16th International Workshop on Clinical Pharmacology of HIV & Hepatitis Therapy]. Washington, DC, 2015.