Abstract

Aim

We conducted a prospective evaluation of all eosinophilic drug reactions (EDRs) through the Prospective Pharmacovigilance Program from Laboratory Signals at Hospital to find out the incidence and distribution of these entities in our hospital, their causative drugs, and predictors.

Methods

All peripheral eosinophilia >700 × 106 cells l−1 detected at admission or during hospitalisation, were prospectively monitored over 42 months. The spectrum of the localised or systemic manifestation of EDR, the incidence, the distribution of causative drugs, and the predictors were analysed.

Results

The incidence of EDR was 16.67 (95% Poisson confidence interval [CI]: 9.90–25.98) per 10 000 admissions. Of 274 cases of EDR, 154 (56.2%) cases in 148 patients were asymptomatic hypereosinophilia. In the remaining 120 (43.8%) cases, there was other involvement. Skin and soft tissue reactions were detected in 36 (13.1%) cases; visceral EDRs in 19(7.0%) cases; and drug‐induced eosinophilic cutaneous and visceral manifestations were detected in the remaining 65 (23.7%) cases, 64 of which were potential drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS). After adjusting for age, sex, and hospitalisation wards, predictors of symptomatic eosinophilia were earlier onset of eosinophilia (hazard ratio [HR], 10.49; 95%CI: 3.13–35.16) higher eosinophil count (HR, 8.51; 95%CI: 3.28–22.08), and a delayed onset of corticosteroids (HR, 1.34; 95%CI: 1.01–1.73). A higher eosinophil count in patients with DRESS was significantly associated with greater impairment of liver function, prolonged hospitalisation, higher cumulative doses of corticosteroids, and if hypogammaglobinaemia was detected, a reactivation of human‐herpesvirus 6 was subsequently detected.

Conclusions

Half (53.3%, 64/120 cases) of symptomatic EDRs were potential DRESS. The main predictor of severity of EDR was an early severe eosinophilia.

Keywords: adverse drug reaction, drug‐induced, eosinophilia, eosinophilic drug reactions, pharmacovigilance

What is Already Known about this Subject

In areas where helminth exposure is uncommon, medication‐related drug reactions are a common cause of persistent peripheral eosinophilia.

Eosinophilic drug reactions have a diversity of presentations, which range from benign and self‐limited to severe and life‐threatening.

The systemic disease, affecting multiple organs, is classically exemplified by drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms.

What this Study Adds

The main predictor of severity of eosinophilic drug reactions was an early severe eosinophilia.

A thorough investigation of prodromal symptoms that usually precede exanthema by up to 4 weeks and close patient follow‐up to achieve early drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms diagnosis and early detection of complications is essential in patients with early severe eosinophilia.

Table of Links

This Table lists key ligands in this article which are hyperlinked to corresponding entries in http://www.guidetopharmacology.org, the common portal for data from the IUPHAR/BPS Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 1, or in ATC/DDD Index 2016 http://www.whocc.no/atc_ddd_index/. In the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical classification system, the active substances are divided into different groups according to the organ or system on which they act and their therapeutic, pharmacological and chemical properties. Drugs are classified in groups at five different levels. The drugs are divided into fourteen main groups (1st level), with pharmacological/therapeutic subgroups (2nd level). The 3rd and 4th levels are chemical/pharmacological/therapeutic subgroups and the 5th level is the chemical substance. The 2nd, 3rd and 4th levels are often used to identify pharmacological subgroups when that is considered more appropriate than therapeutic or chemical subgroups.

Introduction

In areas where helminth exposure is uncommon, medication‐related drug reactions are a common cause of persistent peripheral eosinophilia. In the absence of other systemic involvement, this condition generally constitutes a benign drug effect that can be caused by a myriad of medication classes. Drugs commonly associated with benign eosinophilia include penicillin and sulphonamide drugs 2.

Nevertheless, the finding of eosinophilia is of limited value in the determination of whether the reaction is drug induced. In a broad evaluation of inpatient adverse cutaneous drug reactions, only 18% had peripheral eosinophilia (>700 × 106 cells l−1) 3. Eosinophilic drug reactions (EDRs) have recently been described as a type IVb reaction 4, which involves a Th2‐mediated immune response with secretion of IL‐4, IL‐13, and IL‐5. IL‐5 is known to be the key factor in regulating the growth, differentiation, and activation of eosinophils. Eosinophil activity is also augmented by Th1 cytokines, including IL‐3 and granulocyte‐macrophage colony‐stimulating factor (GM‐CSF) 5, 6, 7, 8. There are numerous types of EDR, ranging from benign, asymptomatic eosinophilia to potentially fatal reactions resulting in organ damage. The extent of clinical involvement is also heterogeneous, ranging from isolated peripheral eosinophilia or single organ involvement (skin, lung, kidney, liver) to systemic disease affecting multiple organs, classically exemplified by drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS). Given the multitude of clinical patterns associated with eosinophilic drug allergy, the diagnosis can be challenging. Our knowledge of these presentations is currently limited, but the potential for severe reactions should be considered to facilitate diagnosis and establish appropriate therapy at an early stage of the disease. Diagnosis is not easy because of the different times at which each symptom appears, which hides the severity of the condition.

The Pharmacovigilance Program from Laboratory Signals at Hospital (PPLSH) is a programme based on the systematic detection of predefined abnormal laboratory values (automatic laboratory signal [ALS]), using the laboratory information system of the hospital. PPLSH has been useful for the early detection and evaluation of specific severe adverse drug reactions (ADRs) 9. The aim of this study was to detect all forms of drug hypersensitivity associated with peripheral eosinophilia, hospital acquired or community acquired, through a PPLSH in all hospitalised patients over a period of 42 months.

Materials and methods

Setting

La Paz University Hospital in Madrid, Spain, is a tertiary‐care teaching facility. During the 42 months of the study (February 2012 to August 2015, except August 2014), all admissions were monitored by the PPLSH 9 in accordance with the Spanish Personal Data Protection Law 10. PIELenRed (una plataforma para la investigación de las reacciones cutáneas graves, a platform for the investigation of severe skin reactions) approval was obtained from the appropriate Institutional Review Board. All eosinophilic drug reaction cases were reported to the Spanish pharmacovigilance system. Drugs were categorised by active ingredient using the Anatomical Therapeutics Chemical classification system.

Information system and coverage

A specific database application was developed within the Integrated Laboratory System (Labtrack®, Woolloomooloo, Australia) to detect predefined ALS, which was retrieved systematically. When we detected a signal in a hospitalised patient, hospital acquired or community acquired, a systematic review of the patient's electronic medical record was performed, including laboratory, microbiological, immunological, and imaging tests as well as drugs administered both at home and in hospital.

Definition of signal

The criterion for eosinophilia was a total count of eosinophils >700 × 106 cells l−1 11. Hospital laboratories performing blood tests on inpatient and emergency patients are certified and accredited under the appropriate International Standards Organisation (ISO 9001:2000 and ISO 15189).

Definition of ADR

The International Conference on Harmonisation E2D definition of ADR was used 12. Medical errors, considered any in written prescription, dispensation, or administration, were excluded.

Procedure for ADR detection and evaluation

-

Phase I

On‐file laboratory data for all admissions were screened: 24 h per day, 7 days per week to find eosinophilia. If a single isolated elevated eosinophil count was retrieved, the laboratory performed an assessment, and if eosinophilia was confirmed, a case‐by‐case basis evaluation was made. Repeated ALS for the same patient on consecutive days with no normal eosinophil count between were discarded, except the first.

-

Phase II

The patient's files, including electronically available microbiological, immunological, and imaging results and medical reports were reviewed. The patients, who had eosinophilia upon arrival to the emergency wards (general, trauma, obstetric or paediatric) but who were not admitted to hospital, were discarded from the PPLSH, except those who died in the emergency wards. Those patients with eosinophilia upon arrival to the emergency wards who were admitted to hospital were included in the PPLSH, as well those hospitalised patients with hospital‐acquired eosinophilia. When a clear alternative cause was ascertained, the case was considered nondrug related. Alternative causes were evaluated on a case‐by‐case basis.

-

Phase III

For the remaining cases, one or two of the authors performed a detailed review of patient's paper charts. Whenever possible, we interviewed the attending physician and the patient and/or their relatives to obtain more details (e.g., the start date or approximate start date of every medication in current treatment); if necessary, further tests (herpes virus DNA and antibodies, including human herpesvirus 6 [HHV6], serum levels of gamma globulin, or biopsy) were performed according to the attending physician's criteria. Determination of HHV6 and immunoglobulin levels was recommended at the time of the DRESS diagnosis, before the onset of steroid therapy, and at the discharge. Changes in serum levels of gamma globulin were calculated. HHV6 antibodies were determined by indirect immunofluorescence assay; dilutions starting at 1:320 were considered positive and dilutions above 1:80 and below 1:160 were considered doubtful. Gamma globulin levels were measured by serum protein electrophoresis. The definition of hypogammaglobulinaemia was a count below the lower limit of normal.

Collection of patient data and reporting

When a patient was categorised as having a drug‐induced eosinophilia, a complete adverse reaction report was submitted to the pharmacovigilance centre in Madrid.

Diagnosis validation of potential DRESS

Potential DRESS syndrome was diagnosed when the case was evaluated as probable or definitive (a score of 4 or more), using the scoring system proposed by Kardaun et al. 13 Cases included in PIElenRed were at the same time included in the RegiSCAR study group, which validated the potential cases as definite, probable, or possible by the PIELenRed consortium or by RegiSCAR.

Assessment of causality

The causality assessment was performed using the algorithm of the Spanish pharmacovigilance system 14. This algorithm evaluates the following parameters: the chronology referred to as the interval between drug administration and effect, the literature defining the degree of knowledge of the relationship between the drug and the effect, the evaluation of drug withdrawal, the rechallenge effect, and the alternative causes. The final case evaluation is listed as improbable (not related), conditional (not related), possible (related), probable (related), or definitive (related). Alternative causes were evaluated as a practical approach 15. For asymptomatic drug‐induced eosinophilia, a careful history was taken and a case‐by‐case basis evaluation was made to attempt to elucidate the sequence of events from the introduction of a new treatment to the discovery of eosinophilia and/or the appearance of symptoms. In acute cases, identification of the offending agent was based on the chronology of drug initiation as well as the type of molecule itself (e.g. antibiotics, antiepileptics). In nonacute cases, the evaluation was more challenging, and we proceeded by trial and error. If, after withdrawal, the dechallenge effect appeared within 30 days and other causes were ruled out, an asymptomatic eosinophilic drug reaction was accepted. We recommended withdrawal of any drug that was not crucial for the patient's well‐being. In cases of immunosuppressive therapy or antineoplastic treatment, monitoring of the clinical evolution was recommended without withdrawing the suspected drug. If a symptomatic eosinophilia drug‐induced reaction developed, cessation of drug administration was warranted. For DRESS, a suggestive chronology was considered if the drug was initiated less than 6 months previously and was stopped in less than 14 days before the index day. In DRESS cases, the exanthema index day was the day in which the exanthema appeared, and the prodromal index day was the day in which the first symptom or sign occurred. Drug causality for DRESS syndrome patients was additionally established by allergological study, including a lymphocyte transformation test (LTT), and epicutaneous, prick, and intradermal (ID) tests 16, 17.

Data analysis

The in‐hospital incidence rate of eosinophilia was calculated by dividing the number of cases of drug‐induced reactions by the number of hospitalised patients obtained from the hospital management service during the 42 selected months. The uncertainty of the association was assessed by calculation of the 95% two‐sided Poisson confidence interval (CI). To evaluate possible differences in age, we performed Student t test for two samples or the Mann–Whitney test for unequal variance or non‐Gaussian distribution, respectively, as appropriate. The chi‐squared test was performed for categorical variables. Proportional CIs were calculated using the modified Wald method. A Cox proportional hazard model, backward procedure, was developed to obtain the predictors, including the varied time onset of eosinophilia and of corticosteroids, of symptomatic drug‐induced eosinophilia reactions. Both univariate and multivariate (adjusted for age, sex, and hospitalisation wards) hazard ratios (HRs) were estimated. The correlations were determined using Pearson's or Spearman's rank correlation, as appropriate. The data analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 20.0.0 (IBM Corporation, USA).

Results

Over the 42 months of the study, there were 164 379 admissions to hospital; of these, 3233 cases of eosinophilia were detected. Table 1 shows the number of cases, percentages, incidence rates, and CIs of incidence rates corresponding to the diagnoses causing eosinophilia. A total of 274 cases of eosinophilia in 267 patients were categorised as ADR. The incidence rate for 10 000 patients during the period of the study was 16.67 (CI 95%: 9.90–25.98). Of these, 106 (39.7%) cases were community acquired and 216 (78.8%) cases were hospital acquired. The general demographics and admission wards of the population with drug‐induced eosinophilia are shown in Table 2.

Table 1.

Breakdown by diagnosis of eosinophilia over 42 months of the Pharmacovigilance Program from Laboratory Signals at Hospital

| Total | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Signal category | Aetiologies | No. of cases | % of cases | Incidence rate (for 10 000 patients) | Confidence interval of incidence rate a (for 10 000 patients) |

| Eosinophilia | Convalescence of viral, bacterial or protozoal infections | 635 | 19.64 | 38.63 | 27.73–52.16 |

| Preterm neonates | 624 | 19.30 | 37.96 | 26.89–51.00 | |

| Solid malignancies | 356 | 11.01 | 21.66 | 13.79–32.10 | |

| Drugs | 274 | 8.48 | 16.67 | 9.90–25.98 | |

| Adultsb | 246 | 89.8 | 18.48 | 11.44–28.45 | |

| Childrenb | 28 | 10.2 | 8.97 | 4.12–15.76 | |

| Haematological diseases | 176 | 5.44 | 10.71 | 5.49–18.39 | |

| Acute lymphoid leukaemia | 56 | 1.73 | 3.41 | 1.09–8.76 | |

| Lymphoma | 54 | 1.67 | 3.29 | 1.09–8.76 | |

| Myeloproliferative disorders | 23 | 0.71 | 1.40 | 0.24–5.57 | |

| Graft versus host diseases | 23 | 0.71 | 1.40 | 0.24–5.57 | |

| Pernicious anaemia | 14 | 0.43 | 0.85 | 0.03–3.69 | |

| Fungoid mycosis | 6 | 0.19 | 0.37 | 0.03–3.69 | |

| Allergic disorders | 176 | 5.44 | 10.71 | 5.49–18.39 | |

| Extrinsic asthma | 93 | 2.88 | 5.66 | 2.20–11.67 | |

| Hay fever | 43 | 1.33 | 2.62 | 0.62–7.23 | |

| Rhinitis or conjunctivitis | 27 | 0.84 | 1.64 | 0.24–5.57 | |

| Food allergy | 6 | 0.19 | 0.37 | 0.03–3.69 | |

| Nondrug related urticaria | 5 | 0.15 | 0.30 | 0.03–3.69 | |

| Bronchopulmonary aspergillosis | 2 | 0.06 | 0.12 | 0.03–3.69 | |

| Prostheses and implants | 167 | 5.17 | 10.16 | 5.49–18.39 | |

| Postsurgical (tissue damage) | 162 | 5.01 | 9.86 | 4.80–17.08 | |

| Splenectomy | 90 | 2.78 | 5.48 | 2.20–11.67 | |

| Dermatologic diseases | 90 | 2.78 | 5.48 | 2.20–11.67 | |

| Atopic dermatitis | 67 | 2.07 | 4.08 | 1.62–10.24 | |

| Henoch–Schölein purpura | 8 | 0.25 | 0.49 | 0.03–3.69 | |

| Herpetiformis dermatitis | 5 | 0.15 | 0.30 | 0.03–3.69 | |

| Pemphigus | 5 | 0.15 | 0.30 | 0.03–3.69 | |

| Bullous pemphigoid | 3 | 0.09 | 0.18 | 0.03–3.69 | |

| Histiocytosis X | 1 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.03–3.69 | |

| Erythema nodosum | 1 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.03–3.69 | |

| Chronic renal failure | 78 | 2.41 | 4.75 | 1.62–10.24 | |

| Connective diseases | 70 | 2.17 | 4.26 | 1.62–10.24 | |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 27 | 0.84 | 1.64 | 0.24–5.57 | |

| Sjögren syndrome | 12 | 0.37 | 0.73 | 0.03–3.69 | |

| Dermatomyositis or polymyositis | 11 | 0.34 | 0.67 | 0.03–3.69 | |

| Churg–Strauss syndrome | 8 | 0.25 | 0.49 | 0.03–3.69 | |

| Polyarteritis nodosa | 5 | 0.15 | 0.30 | 0.03–3.69 | |

| Wegener's granulomatosis | 3 | 0.09 | 0.18 | 0.03–3.69 | |

| Scleroderma | 3 | 0.09 | 0.18 | 0.03–3.69 | |

| Eosinophilic fasciitis | 1 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.03–3.69 | |

| Solid organ transplantation rejection | 67 | 2.07 | 4.08 | 1.62–10.24 | |

| Adrenal insufficiency | 47 | 1.45 | 2.86 | 0.62–7.23 | |

| Abortion or delivery | 47 | 1.45 | 2.86 | 0.62–7.23 | |

| Immunodeficiencies | 46 | 1.42 | 2.80 | 0.62–7.23 | |

| Wiskott‐Aldrich syndrome | 15 | 0.46 | 0.91 | 0.03–3.69 | |

| HIV infection | 13 | 0.40 | 0.79 | 0.03–3.69 | |

| Selective IgA deficiency | 7 | 0.22 | 0.43 | 0.03–3.69 | |

| Severe combined immunodeficiency | 7 | 0.22 | 0.43 | 0.03–3.69 | |

| Hyper IgE syndrome | 4 | 0.12 | 0.24 | 0.03–3.69 | |

| Parasitic infections | 40 | 1.24 | 2.43 | 0.62–7.23 | |

| Pinworms | 10 | 0.31 | 0.61 | 0.03–3.69 | |

| Anisakis | 9 | 0.28 | 0.55 | 0.03–3.69 | |

| Strongyloids | 8 | 0.25 | 0.49 | 0.03–3.69 | |

| Echinococcus granulosus | 6 | 0.19 | 0.37 | 0.03–3.69 | |

| Taenia sp | 4 | 0.12 | 0.24 | 0.03–3.69 | |

| Hepatic fascioliasis | 3 | 0.09 | 0.18 | 0.03–3.69 | |

| Irradiation | 34 | 1.05 | 2.07 | 0.62–7.23 | |

| Gastrointestinal diseases | 31 | 0.96 | 1.89 | 0.24–5.57 | |

| Inflammatory bowel disease | 21 | 0.65 | 1.28 | 0.24–5.57 | |

| Cow's milk protein enteropathy | 7 | 0.22 | 0.43 | 0.03–3.69 | |

| Eosinophilic gastroenteritis | 3 | 0.09 | 0.18 | 0.03–3.69 | |

| Fungal infections (coccidioidomycosis and allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis) | 23 | 0.71 | 1.40 | 0.24–5.57 | |

| Total | 3233 | 100 | 196.68 | 167.66–222.23 | |

Two‐sided Poisson 95% confidence interval

Frequency was calculated with respect to total drug‐induced eosinophilia. Incidence rates and confidence intervals were calculated with respect to adult or child hospitalisations, respectively

Table 2.

Demographics, comorbidities, wards of admission, concomitant immunosuppressive therapy of population with drug‐induced eosinophilia, asymptomatic eosinophilia vs. symptomatic eosinophilia vs. drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS). Predictors of symptomatic eosinophilia among patients with drug‐induced eosinophilia based on Cox proportional hazard model

| Drug‐induced eosinophilia | Asymptomatic eosinophilia | Symptomatic eosinophilia | Significance | DRESS | Significance | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics (patients) | n = 267 | n = 148 | n = 120 | P valuea | n = 64 | P valueb |

| Total | ||||||

| Male patients (%) | 53.9% | 60.1% | 45.8% | 0.027 | 34.5% | 0.001 |

| Age (years), median, range | 62 (0.1–99) | 69 (0.1–99) | 56 (1–91) | 0.043 | 52 (12–91) | 0.031 |

| Community cases, n (%) | 106 (39.7%) | 70 (47.3%) | 36 (30.0%) | 0.006 | 22 (34.4%) | 0.081 |

| Paediatrics | 28 (10.5%) | 18 (12.2%) | 10 (8.3%) | 0.006 | 9 (14.1%) | <0.001 |

| Male patients, (%) | 53.6% | 57.9% | 44.4% | 0.674 | 44.4% | 0.674 |

| Age in years (median, range) | 5 (0.1–16) | 5 (0.1–12) | 12 (4–16) | 0.126 | 12 (4–16) | 0.126 |

| Community cases, n (%) | 12 (42.9%) | 9 (47.4%) | 3 (33.3%) | 0.770 | 3 (33.3%) | 0.770 |

| Adults | 239 (89.5%) | 129 (87.2%) | 110 (91.7%) | 0.326 | 55 (85.9%) | 0.809 |

| Male patients, (%) | 53.6% | 60.9% | 44.2% | 0.010 | 36.0% | 0.003 |

| Age in years (median, range) | 69 (19–99) | 72 (19–99) | 58 (18–91) | 0.004 | 55 (22–91) | 0.002 |

| Community cases, n (%) | 94 (39.3%) | 61 (47.3%) | 33 (27.5%) | 0.027 | 19 (34.5%) | 0.110 |

| Wards of hospitalisation (cases), n (%) | n = 274 | n = 154 | n = 120 | P valuea | n = 64 | P valueb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiology | 15 (5.5%) | 13 (8.4%) | 2 (1.7%) | 0.029 | 1 (1.6%) | 0.113 |

| Dermatology | 19 (6.9%) | ‐ | 19 (15.8%) | <0.001 | 12 (18.8%) | <0.001 |

| Gastroenterology | 15 (5.5%) | 8 (5.2%) | 7 (5.8%) | >0.999 | 3 (4.7%) | >0.999 |

| Geriatrics | 18 (6.6%) | 12 (7.8%) | 6 (5.0%) | 0.497 | 3 (4.7%) | 0.595 |

| Gynaecology and Obstetrics | 6 (2.2%) | 4 (2.6%) | 2 (1.7%) | 0.915 | 1 (1.6%) | 0.171 |

| Haematology | 19 (6.9%) | 15 (9.7%) | 4 (3.3%) | 0.067 | 2 (3.1%) | 0.171 |

| Intensive care units | 12 (4.4%) | 5 (3.2%) | 7 (5.8%) | 0.452 | 5 (7.8%) | >0.999 |

| Internal Medicine | 36 (13.1%) | 12 (7.8%) | 24 (20.0%) | 0.005 | 17 (26.6%) | <0.001 |

| Nephrology | 18 (6.6%) | 9 (5.8%) | 9 (7.5%) | 0.762 | 2 (3.1%) | 0.620 |

| Neurology | 13 (4.7%) | 11 (7.1%) | 2 (1.7%) | 0.067 | 2 (3.1%) | 0.408 |

| Oncology | 15 (5.5%) | 12 (7.8%) | 3 (2.5%) | 0.010 | 1 (1.6%) | 0.146 |

| Paed. haemato‐oncology | 9 (3.3%) | 4 (2.6%) | 5 (4.2%) | 0.703 | ‐ | 0.455 |

| Paed. nephrology hepatology | 5 (1.8%) | 3 (1.9%) | 2 (1.7%) | >0.999 | 1 (1.6%) | >0.999 |

| Paediatrics | 14 (5.1%) | 6 (3.9%) | 8 (6.7%) | 0.449 | 6 (9.4%) | 0.197 |

| Pneumology | 9 (3.3%) | 3 (1.9%) | 6 (5.0%) | 0.287 | 2 (3.1%) | 0.975 |

| Psychiatry | 12 (4.4%) | 12 /7.8%) | ‐ | 0.005 | ‐ | 0.049 |

| Rheumatology | 14 (5.1%) | 6 (3.9%) | 8 (6.7%) | 0.449 | 2 (3.1%) | >0.999 |

| Surgery | 18 (6.6%) | 14 (9.1%) | 4 (3.2%) | 0.096 | 2 (3.1%) | 0.210 |

| Tropical medicine | 7 (2.6%) | 5 (3.2%) | 2 (1.7%) | 0.669 | 2 (3.1%) | >0.999 |

| Comorbid diseases, (Patients), n (%) | n = 267 | n = 148 | n = 120 | P valuea | n = 64 | P valueb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Atopy | 49 (18.4%) | 20 (13.5%) | 29 (24.2%) | 0.081 | 17 (21.9%) | 0.022 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 25 (9.4%) | 8 (5.4%) | 17 (14.2%) | 0.025 | 9 (14.1%) | 0.033 |

| Active Cancer | 23 (8.6%) | 11 (7.4%) | 12 (10.0%) | 0.598 | 7 (10.9%) | 0.401 |

| Asthma | 15 (5.6%) | 4 (2.7%) | 11 (9.2%) | 0.043 | 6 (9.4%) | 0.035 |

| Collagen vascular disease | 24 (9.0%) | 13 (8.8%) | 11 (9.2%) | >0.999 | 6 (9.4%) | 0.803 |

| Drug hypersensitivity | 21 (7.9%) | 12 (8.1%) | 9 (7.5%) | >0.999 | 5 (7.8%) | 0.942 |

| Chronic liver disease | 16 (6.0%) | 9 (6.1%) | 7 (5.8%) | >0.999 | 4 (6.3%) | 0.962 |

| Radiation therapy | 6 (2.2%) | 4 (2.7%) | 2 (1.7%) | 0.877 | 1 (1.6%) | 0.993 |

| HIV | 6 (2.2%) | 3 (2.0)% | 3 (2.5%) | >0.999 | 1 (1.6%) | >0.999 |

| Comedication, (patients), n (%) | ||||||

| Systemic corticosteroids or other immunosuppressive drugs | 111 (41.6%) | 5 (3.4%) | 106 (88.3%) | <0.001 | 64 (100%) | <0.001 |

| Variables retained in the Cox proportional hazard model to assess the predictors of symptomatic eosinophilia in drug‐induced eosinophilia | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate HR (95% CI) | Univariate HR P valuea | Multivariate HR (95% CI) | Multivariate HR P valueb | |||

| Period after onset of eosinophilia, patient days | 11.29 (4.03–31.63) | <0.001 | 10.49 (3.13–35.16) | <0.001 | ||

| Eosinophil count, cells mm−3 | 8.51 (3.32–21.81) | <0.001 | 8.51 (3.28–22.08) | <0.001 | ||

| Delayed onset of corticosteroids, patient days | 1.34 (1.02–1.76) | 0.017 | 1.32 (1.01–1.73) | 0.021 | ||

| Chronic kidney disease | 3.53 (1.49–8.36) | <0.001 | 1.01 (0.99–1.02) | 0.387 | ||

Asymptomatic vs. symptomatic eosinophilia comparison

Asymptomatic vs. DRESS comparison

Based on Cox proportional hazard model, backward procedure, adjusted for age, sex, and hospitalisation wards; CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio

Asymptomatic eosinophilia

Out of 274 cases of drug‐induced eosinophilia, 154 cases in 148 patients were isolated peripheral blood eosinophilia. Of these, 70 (47.3%) cases were community acquired. The latency time (median, range) to onset of eosinophilia was 6 days (1–21 days). The peak (median, range) of eosinophil count was 760 × 106 cells l−1 (722–2300 × 106 cells l−1) Table 2 shows the demographics of the cases. The most frequent causal therapeutic group was anti‐infectives for systemic use (58 cases), primarily beta‐lactam drugs, the most frequent being enalapril and filgrastim (five cases each), followed closely by multiple drugs. The drugs associated with benign eosinophilia are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Drug causality of asymptomatic eosinophilia

| Drug | No. of cases |

|---|---|

| Anti‐infectives for systemic use | 58 |

| Amikacin | 1 |

| Amoxicillin | 3 |

| Amoxicillin clavulanic acid | 3 |

| Amphotericin b (liposomal) | 2 |

| Azithromycin | 3 |

| Aztreonam | 3 |

| Caspofungin | 1 |

| Ceftriaxone | 2 |

| Clarithromycin | 1 |

| Efavirenz | 3 |

| Ethambutol | 2 |

| Levofloxacin | 3 |

| Linezolid | 1 |

| Minocycline | 2 |

| Nevirapine | 1 |

| Penicillin G | 2 |

| Piperacillin tazobactam | 4 |

| Posaconazole | 3 |

| Rifabutin | 3 |

| Rifampin | 3 |

| Sulfamethoxazole‐trimethoprim | 3 |

| Tigecycline | 1 |

| Vaccines * | 4 |

| Vancomycin | 3 |

| Antiparasitic products, insecticides and repellents | 5 |

| Benznidazole | 4 |

| Pyrimethamine | 1 |

| Cardiovascular system | 18 |

| Alpha methyldopa | 3 |

| Atorvastatin | 2 |

| Diltiazem | 1 |

| Enalapril | 5 |

| Fenofibrate | 1 |

| Gemfibrozil | 1 |

| Quinidine | 1 |

| Simvastatin | 2 |

| Spironolactone | 2 |

| Nervous system | 18 |

| Carbamazepine | 3 |

| Chlorpromazine | 2 |

| Imipramine | 2 |

| Lamotrigine | 3 |

| Olanzapine | 2 |

| Oxcarbazepine | 2 |

| Phenytoin | 3 |

| Trazodone | 1 |

| Musculoskeletal system | 14 |

| Allopurinol | 4 |

| Dantrolene | 1 |

| Dexketoprofen | 3 |

| Gold salts | 1 |

| Ibuprofen | 2 |

| Metamizole | 2 |

| Tramadol | 1 |

| Blood and hematopoietic system | 13 |

| Acetylsalicylic | 1 |

| Bemiparin | 1 |

| Clopidogrel | 2 |

| Enoxaparin | 2 |

| Filgastrim | 5 |

| Prasugrel | 1 |

| Sodium heparin | 1 |

| Digestive system and metabolism | 11 |

| Mesalazine | 2 |

| Omeprazole | 2 |

| Pantoprazole | 2 |

| Ranitidine | 1 |

| Repaglidine | 1 |

| Sulfasalazine | 2 |

| Vildagliptine | 1 |

| Antineoplastic and immunomodulating agents | 11 |

| Azathioprine | 2 |

| Bleomycin | 1 |

| Fludarabine | 1 |

| Leflunomide | 2 |

| Methotrexate | 2 |

| Rituximab | 3 |

| Respiratory system | 3 |

| Zafirlukast | 1 |

| Montelukast | 2 |

| Others | |

| Iodinated contrast | 3 |

| Total | 154 |

Influenza vaccine (2), bacterial vaccine (2)

Symptomatic eosinophilia

The remaining 120 cases showed other involvement. Of these, 36 (30.0%) cases were community acquired. The peak (median, range) of eosinophil count was 880 × 106 cells l−1 (range, 791–8300 × 106 cells l−1). Skin and soft tissue reactions included maculopapular exanthema or morbilliform eruptions in 28 cases (amoxicillin [two cases], ampicillin, antifibrin, bemiparin, ceftriaxone, cefotaxime, ciprofloxacin, clindamycin, chlorthalidone, digoxin, enoxaparin, influenza vaccine, ethambutol, Gelatin agents, hydrochlorothiazide, ibuprofen, levofloxacin, meropenem, mesalazine, methamizole, methotrexate, minocycline, nimodipine, piperacillin/tazobactam, sirolimus, spironolactone, and sulfasalazine); acute generalised exanthematous pustulosis was detected in four cases in three patients (benznidazole, hydroxychloroquine, vancomycin positive rechallenge); eosinophilic cellulitis in three cases (adalimumab, etanercept, infliximab); and one case of neutrophilic dermatosis after azathioprine exposure. Visceral eosinophilic drug reactions included acute interstitial nephritis in eight cases (allopurinol, ibuprofen, levofloxacin, metamizole, pantoprazole, piperacillin/tazobactam, rifampicin, rifabutin); eosinophilic pneumonia in four cases (daptomycin, escitalopram, methotrexate, venlafaxine); eosinophilic hepatitis in three cases (amoxicillin/clavulanate, atorvastatin and simvastatin); eosinophilic myopathies in two cases (L‐tryptophan supplement and atorvastatin); and gastroenterocolitis in two cases (ibuprofen, tacrolimus). Drug‐induced eosinophilic cutaneous and visceral manifestations were detected in the remaining 65 cases: toxic epidermal necrolysis was detected in one case (levofloxacin) and potential DRESS was detected in 64 cases, of which 24 were included and validated in PIELenRed. During the acute phases, three (5%) of 65 cases died.

After adjusting for age, sex and hospitalisation ward, patients with hospital‐acquired symptomatic drug‐induced eosinophilia reactions were significantly more likely to have an earlier onset of eosinophilia (HR, 10.49; 95% CI: 3.13–35.16), a higher eosinophil count (HR, 8.51; 95% CI: 3.28–22.08), and a delayed onset of corticosteroids (HR, 1.34; 95% CI: 1.01–1.73). Although patients with chronic kidney injury had more serious organ involvement in symptomatic eosinophilia, this increase was not statistically significant after adjustment (Table 2).

Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms/drug‐induced hypersensitivity syndrome

Twenty‐two of 64 cases of potential DRESS (34.4%) were community cases, whereas in 42 (65.6%) cases, the reaction started during the hospitalisation. The incidence rate for 10 000 patients during the period of the study was 3.89 (CI 95%: 1.09–8.77). One case was classified as overlapping with possible Stevens–Johnson syndrome (benznidazole), and one case was diagnosed as overlapping with possible acute generalised exanthematous pustulosis (benznidazole). Table 2 shows the demographics of the cases. The most frequent symptoms were skin involvement (100%), fever ≥38.5°C (86%), and influenza‐like symptoms (67%). The cases' characteristics are shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Characteristics of probable and definitive cases of drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS), culprit drugs and latency of the probable causal drugs

| n | (%) | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Skin involvement | 64 | 100 | 93.2–100 |

| Rash > 50% of involvement | 47 | 73.4 | 61.4–82.8 |

| Facial oedema | 36 | 56.3 | 44.1–67.7 |

| Monomorphic maculopapular | 7 | 10.9 | 5.1–21.2 |

| Polymorphous maculopapular | 52 | 82.8 | 69.9–89.1 |

| Pustules | 19 | 30 | 19.9–41.8 |

| Purpura | 7 | 10.9 | 5.1–21.2 |

| Blisters | 5 | 7.8 | 3.0–17.4 |

| Eosinophilia | 64 | 100 | 93.2–100 |

| Influenza‐like symptoms | 43 | 67.2 | 55.0–77.5 |

| Fever ≥ 38.5°C | 55 | 85.9 | 75.2–92.7 |

| Lymphadenopathy | 29 | 45.3 | 33.7–57.4 |

| Other haematological abnormalities | 64 | 100 | 93.2–100 |

| Leucocytosis | 63 | 98.4 | 91.0 to >99.9 |

| Neutrophilia | 52 | 81.3 | 69.9–89.1 |

| Monocytosis | 45 | 70.3 | 58.2–80.2 |

| Atypical lymphocytes | 38 | 60.9 | 47.1–70.6 |

| Lymphocytosis | 37 | 57.8 | 45.6–69.1 |

| Neutropenia | 1 | 1.6 | <0.01–9.1 |

| Thrombocytopenia | 1 | 1.6 | <0.01–9.1 |

| Mucosal involvement | 27 | 42.1 | 49.1–77.1 |

| Mouth/throat/lips | 18 | 66.7 | 47.7–81.5 |

| Eyes | 3 | 11.1 | 3.0–28.9 |

| Genitalia | 2 | 7.4 | 1.0–24.5 |

| Others | 4 | 14.8 | 5.3–33.1 |

| Internal organ involvement | 64 | 100 | 93.2–100 |

| One organ | 26 | 40.6 | 29.5–52.9 |

| Two organs or > two organs | 38 | 59.4 | 47.1–70.6 |

| Liver | 50 | 78.1 | 66.5–86.6 |

| Kidney | 22 | 34.4 | 23.9–46.6 |

| Lung | 20 | 32.8 | 21.2–43.3 |

| Pancreas | 5 | 7.8 | 3.0–17.4 |

| Brain | 3 | 4.7 | 1.1–13.4 |

| Myositis | 1 | 1.6 | <0.01–9.1 |

| HHV‐6 reactivation | 10 of 37 | 37.8 | 15.2–43.1 |

| Duration of DRESS ≥ 15 days | 64 | 100 | 93.2–100 |

| Exposure | Cases | Exanthema latency time (days) | Prodromal latency time (days) b |

|---|---|---|---|

| n | Median (range) | Median (range) | |

| Total number of drugs | 517 | ||

| Causality a | |||

| Definitive (>8) | 0 | ||

| Probable (6–7) | 64 | 27 (3–86) | 13 (3–30) |

| Possible (4–5) | 87 | 24 (1–191) | 20 (1–164) |

| Conditional (1–3) | 288 | 113 (4 – >1092) | 106 (4 – >1092) |

| Unlikely (<0) | 74 | 102 (67 – >1092) | 95 (61 – >1092) |

| Undetermined (no data) | 4 | ||

| Drug probable causality | 64 (100%) | 23 (3–86) | 15 (3–58)c |

| Nervous system | 12 (18.8%) | 28.5 (14–51) | 14.5 (9–30)c |

| Carbamazepine | 4 | 28 (14–48) | 15 (9–28) |

| Lamotrigine | 1 | 29 | 14 |

| Levetiracetam | 2 | 27 | 15 |

| Phenytoin | 5 | 30 (28–51) | 14 (17–30) |

| Digestive system and metabolism | 2 (3.1%) | ||

| Sulfasalazine | 2 | 18–25 | 13–18 |

| Antiinfectives for systemic use | 27 (42.2%) | 24 (12–27) | 14 (7–27)c |

| Amoxicillin‐clavulanic acid | 1 | 25 | 18 |

| Cefepime | 1 | 19 | 13 |

| Ceftazidime | 1 | 17 | 9 |

| Clindamycin | 1 | 16 | 8 |

| Ethambutol | 1 | 24 | 13 |

| Imipenem | 1 | 21 | 16 |

| Isoniazid | 1 | 26 | 15 |

| Levofloxacin | 1 | 18 | 18 |

| Linezolid | 1 | 24 | 14 |

| Meropenem | 1 | 23 | 12 |

| Nevirapine | 2 | 27 | 27 |

| Piperacillin/tazobactam | 4 | 20 (8–28) | 12 (8–21) |

| Pyrazinamide | 1 | 28 | 19 |

| Sulfamethoxazole‐trimethoprim | 4 | 25 (21–30) | 16 (17–21) |

| Teicoplanin | 1 | 32 | 12 |

| Vancomycin | 4 | 27 (19–31) | 13 (11–23) |

| Voriconazole | 1 | 34 | 14 |

| Musculoskeletal system | 12 (18.8%) | 13 (7–39) | 9 (5–30) |

| Allopurinol | 7 | 20 (16–39) | 14 (9–30) |

| Dexketoprofen | 1 | 9 | 9 |

| Ibuprofen | 2 | (11–16) | (7–9) |

| Metamizole | 2 | (7–13) | (5–9) |

| Antineoplastic and immunomodulating agents | 2 (3.1%) | ||

| Azathioprine | 3 | 52 (36–86) | 20 (19–25) |

| Antiparasitic products | 3 (4.7%) | ||

| Benznidazol | 3 | 23 (19–21) | 10 (7–15) |

| Cardiovascular System | 2 (3.1%) | ||

| Diltiazem | 1 | 24 | 18 |

| Spironolactone | 1 | 29 | 23 |

| Others | 3 (4.7%) | ||

| Iodinated contrast | 1 | 3 | 3 |

| Rivaroxabam | 1 | 21 | 12 |

| Vitamin B12 | 1 | 17 | 17 |

Algorithm of the Spanish Pharmacovigilance System

cases developed during hospitalisation

significance, P < 0.05; CI, confidence interval; HHV‐6: human herpesvirus 6

Progression of DRESS signs or symptoms was sequential in all cases. The latency of the same sign or symptom can vary up to 56 days for eosinophilia (median, 21 days) or visceral involvement (median, 20 days), and up to 28 days for hypogammaglobulinaemia (median, 12 days) or fever (median, 11 days).

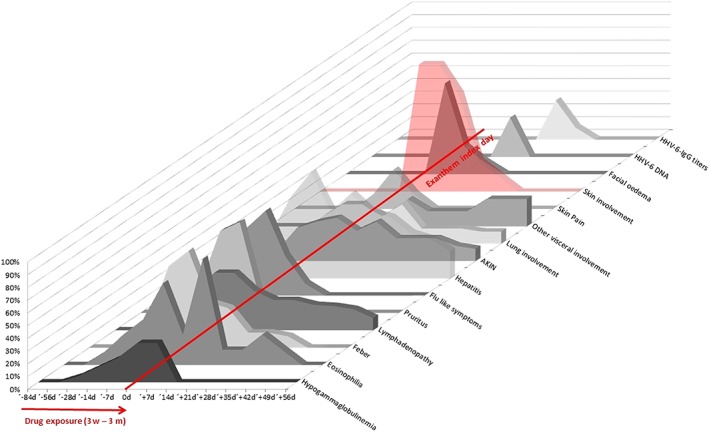

The prodromal stage, defined as the period between the onset of the reaction and the start of the exanthema, lasted up to 4 weeks (median 7 days, range 0–28 days), 9 days in PIELenRed cases (median 1 day, range 0–9 days). Early signs, such as haematological or asymptomatic organ involvement can be present up to 28 days before; in addition, signs and symptoms such as fever, lymphadenopathy, pruritus, influenza‐like symptoms, or skin pain can be evident 2 weeks before (Figure 1). This stage might contribute to the longer latency time in DRESS compared with other SCARs.

Figure 1.

Successive signs and symptoms since drug exposure (3 weeks–3 months), onset of the exanthema (index day, 0 d) and human herpesvirus 6 replication in drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms patients

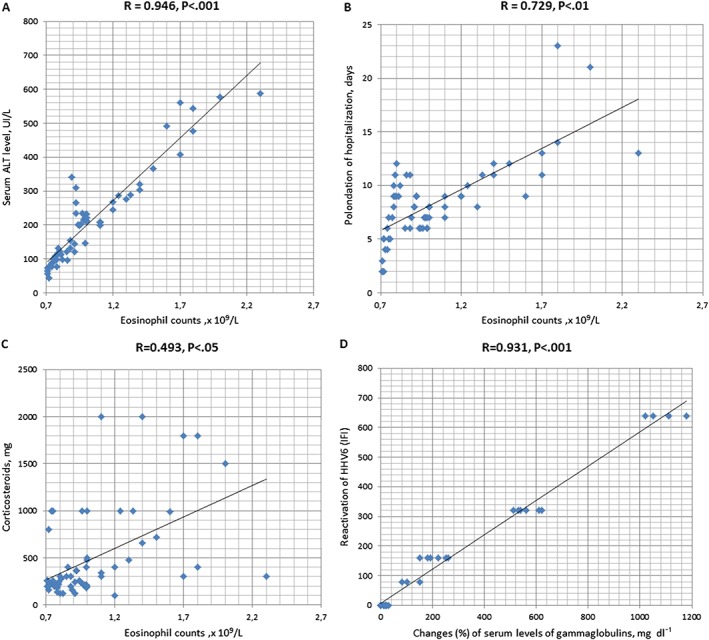

The 42 DRESS cases that developed during hospitalisation were evaluated to assess the predictive signs or symptoms. A positive correlation was found between eosinophil count and serum levels of alanine aminotransferase (R = 0.946; P < 0.001; Figure 2A). Furthermore, eosinophil count positively correlated with longer periods of hospitalisation (R = 0.729; P < 0.01; Figure 2B). These data indicate that circulating eosinophil levels might be closely related to disease severity in patients with DRESS. Longitudinal analyses indicated that the increased eosinophil count decreased significantly after treatment with corticosteroids (Figure 2C); although all the patients received corticosteroid treatment after diagnosis of drug eruption, we focused on the cumulative dose of corticosteroids in DRESS (R = 0.493; P < 0.05). These data suggest that eosinophil count correlates with the severity of the drug eruption; thus, eosinophil count might be a promising predictor of the severity of DRESS. Moreover, in cases in which hypogammaglobulinaemia was detected, a reactivation of HHV‐6 was subsequently detected (R = 0.931; P < 0.001; Figure 2D). This association was not limited to anticonvulsant causality. We ruled out the possibility of an association between hypogammaglobulinaemia and glucocorticoid therapy because Ig levels were measured before the onset of steroid therapy.

Figure 2.

Eosinophil count and drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms severity were positively correlated in patients. Comparisons between eosinophil count and serum alanine aminotransferase levels (A), days of hospitalisation (B), cumulative corticosteroid usage (prednisone, mg) (C). Changes (%) in serum levels of immunoglobulin classes were positively correlated with reactivation of human herpesvirus 6 (immunofluorescence assay) (D). Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms cases occurring during hospitalisation (n = 42)

Drug causality in DRESS was assessed for a total of 517 drugs. The number of suspect drugs was substantially reduced after elimination as a result of the time course. All the patients who took drugs known to cause DRESS had nonsuggestive chronology because of long‐term use (>6 months) or long‐time withdrawal (>14 days) were exposed to another drug within the chosen time window. Probable causality was concluded in all cases. In the DRESS cases that developed during hospitalisation, antibiotics were the most frequent culprits; and for DRESS causing hospitalisation, antiepileptics, allopurinol, azathioprine, and benznidazole were the most frequent causal drugs. Latency time to exanthema index day (median, range) was 23 (3–86) days. Latency time to prodromal index day (median, range) was significantly shorter at 15 (3–58) days, P < 0.05. Two patients experienced accidental re‐exposure to vancomycin and piperacillin/tazobactam, 2 years and 7 months later, respectively; they developed a maculopapular rash and an increase in liver enzymes hours after a unique dose. Of 64 cases, 34 were studied at the allergy department after discharge and at least 4 weeks after discontinuation of treatment with corticosteroids and resolution of the DRESS syndrome. The following allergy tests were performed: the LTT, epicutaneous prick, and ID tests. Of 34 cases, LTT results were positive for the culprit drug in all cases except azathioprine, probably because of the immunosuppressive effect of the drug. LTTs were also performed with other β‐lactams or other aromatic antiepileptic drugs to define a possible cross‐reactivity. Only 23.5% (9/34) of patients had a positive ID, and only 14.7% (5/34) of patients had a positive patch test.

Discussion

The number of eosinophils is normally tightly regulated in the human body. In healthy people, the eosinophil count is only a minority of peripheral blood leukocytes, and their presence in tissues is primarily limited to gastrointestinal mucosa 18. However, under certain conditions, eosinophils can selectively accumulate in peripheral blood or in tissue 19. Any perturbation that results in eosinophilia has profound clinical effects. In our series, the leading cause of eosinophilia was convalescence of viral, bacterial, or protozoal infections followed by preterm neonates, solid malignancies, followed by drugs. It is well established in the literature that a marked accumulation of eosinophils occurs in several disorders, such as convalescence of infections, parasitic infections, and cancer 15, 19, 20, 21. Eosinophilia in preterm newborns has been known for 6 decades 22. The neonatal intensive care unit of our hospital receives approximately 1500 premature newborns per year; thus, our results show a high incidence for this cause of eosinophilia.

In absence of other systemic involvement, isolated peripheral blood eosinophilia is a benign drug effect that can be caused by a myriad of medication classes. It might be a direct physiologic effect of certain cytokine therapies (IL2, GM‐CSF) secondary to expansion of IL‐5‐producing T cells; however, the mechanisms underlying most instances of drug‐related eosinophilia have not been elucidated 2. In our series, asymptomatic eosinophilia by drugs was more frequently observed than symptomatic eosinophilia (154 vs. 120). Our findings support current expert opinion regarding its frequency 23. Among symptomatic eosinophilia cases, the most frequent cause was DRESS (64 cases, 53%), followed by eosinophilia with only dermatological symptoms (36 cases, 30%), and then with visceral involvement (19 cases, 16%). Substantial tissue damage is unlikely to occur with a low eosinophil count, and expert opinion supports that isolated eosinophilia must be monitored; withdrawal of any drug that is not crucial for the patient is recommended 24. Drug‐induced eosinophilia, however, frequently prompts clinical concern regarding impending organ involvement. Our data have shown that the development of symptoms after eosinophilia onset was more likely with earlier onset of eosinophilia, higher eosinophil count, and a delayed onset of corticosteroids. Kimberly et al. 25, in a prospective cohort study of 824 patients receiving prolonged intravenous antibiotic therapy as outpatients, found that the patients with eosinophilia had a significantly higher likelihood of rash (adjusted HR, 4.16; 95% CI: 2.54–6.83) or renal injury (HR, 2.13; 95% CI: 1.36–3.33), compared with the patients without eosinophilia. However, DRESS syndrome only occurred in seven patients. Finally, our data support that DRESS syndrome can occur at a higher frequency than previously reported in the drug‐induced eosinophilia literature 26. The finding of eosinophilia is a diagnostic challenge in clinical practice. The treating physician immediately wonders if the condition is drug induced, which drug is causing it, if it will be benign or symptomatic, and if it will be necessary to withdraw the agent and to initiate corticosteroids.

Previous in vivo and in vitro data indicate that eosinophils are particularly involved in patients with DRESS syndrome 27, 28. DRESS is a distinctive reaction, first described during treatment with anticonvulsant drugs (most commonly carbamazepine), and subsequently with a multitude of medication classes. However, antiepileptic medications remain the predominant cause of DRESS, with an incidence of 1 per 5000 to 10 000 exposures 29. The DRESS incidence rate for 10 000 patients during the period of the study was 3.89. There are no other available data in the literature about the incidence of this syndrome in Spain. Antibiotics were the most frequent culprits during hospitalisation but allopurinol, antiepileptics, azathioprine, and benznidazole were the most frequent causal drugs in DRESS causing hospitalisation.

The actual definition of DRESS was proposed by Bocquet et al. in 1996 30 and updated in 2007 by the Registry of Severe Cutaneous Adverse Reactions (RegiSCAR) Study Group 13. DRESS syndrome diagnosis is complex due to the wide variety of signs and symptoms not all present at the same time in the patient 4, 31, 32, 33. The phenotype of the skin is imprecise; the most common presentation is polymorphous maculopapular (85%); however, monomorphic (15%), pustules (30%), and purpura (26%) also occur. Hypereosinophilia was present in 95% of cases. Other haematological manifestations were atypical lymphocytes (67%) and lymphadenopathy (54%). Internal organ involvement has been reported in 91% of cases, primarily due to hepatic injury (elevation of liver function tests or hepatomegaly). Other frequent symptoms were high fever (90%) and mild mucosal involvement (56%) 34. All the data are in concordance with our results except mild mucosal involvement, which was lower in our series (42%). The pathogenesis is unclear, but is most likely to involve several aspects, including a network of drug metabolites, specific HLA alleles, herpes viruses (EBV, HHV‐6, HHV‐7, or CMV), and immune system activation 35.

The results of PPLSH showed that the patients with higher peripheral blood eosinophilia had poorer liver function, prolongation of hospitalisation, and higher cumulative doses of corticosteroids. Yang et al. 36 found that eosinophil count in patients with an erythema multiform‐type drug eruption was associated with severe disease. In the RegiSCAR scoring system proposed by Kardaun et al. 34 for diagnosis of DRESS, the score increases with the degree of eosinophilia from one point if eosinophilia is between 700 and 1499 × 106 cells l−1, to two points if eosinophilia is >1500 × 106 cells l−1.

The association between hypogammaglobulinaemia and DRESS has been previously reported. In a retrospective study, Boccara et al. 37 found that the hypogammaglobulinaemia significantly associated with DRESS was not limited to carbamazepine, but also with other anticonvulsants (phenytoin, phenobarbital) and with other drugs (allopurinol, piperacillin/tazobactam, ibuprofen, celecoxib, vancomycin). This transient immune dysfunction might be a consequence of the severe depletion of B cells observed at the beginning of the DRESS induced by drugs in a predisposed genetic background 38. Most of the drugs associated with DRESS exhibit immunomodulatory properties (e.g., allopurinol, anticonvulsants, anti‐infectives, anti‐inflammatory drugs, azathioprine, benznidazole, sulfasalazine); the consequence can be herpesvirus reactivation, including HHV‐6 associated with DRESS. This reactivation occurs at the very beginning of DRESS, when the clinical symptoms are similar to mononucleosis syndrome, and during the subsequent flares of DRESS. The evolution of signs and symptoms were sequential in all our DRESS cases, as described previously, but with wide variation depending on the case. The usual sequence presentation according to median data was fever (11 days), hypogammaglobulinaemia (12 days), eosinophilia (21 days), visceral involvement (20 days), and exanthema (23 days). These prodromal symptoms are of utmost importance for differentiating asymptomatic eosinophilia of from DRESS syndrome and predicting its degree of severity. Our results are a helpful contribution to this field.

This study has several limitations. The study was performed at a single centre. It is possible that some drug‐induced eosinophilia cases were missed during the process of attributing alternative causes through electronic medical record review (phase II), although this possibility is low given that the alternative causes presented are well known.

Conclusions

The spectrum of eosinophilic drug reactions and the classes of medication associated with peripheral eosinophilia are expanding. Half (53.3%, 64/120 cases) of symptomatic eosinophilic drug reactions were potential DRESS cases, with higher numbers of cases during hospitalisation than in the community. Predictors of symptomatic drug‐induced eosinophilia reactions were earlier onset of eosinophilia, higher eosinophil count and a delayed onset of corticosteroids. Higher eosinophil count in patients with DRESS was significantly associated with greater impairment of liver function, prolonged hospitalisation, and higher cumulative doses of corticosteroids. In DRESS cases in which hypogammaglobulinaemia was assessed, a reactivation of HHV‐6 was subsequently detected. Due to variable clinical presentation, the potential for serious reactions should be considered to facilitate diagnosis and institute appropriate management. In patients with higher eosinophilia, a thorough investigation of prodromal symptoms that usually precede exanthema by up to 4 weeks is essential and close follow‐up of these patients is necessary to achieve early DRESS diagnosis and early detection of complications.

Competing Interests

The cases of PIElenRed were partially supported by research grants from the Instituto de Salud Carlos III‐Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación FIS PI12/02267 (co‐founded by FEDER) to F.J.d.A., EC10‐349, and FIS PI13/01768 (co‐founded by FEDER) to T.B.. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organisation or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in this manuscript.

We are grateful to other members of the PIELenRed consortium for their contribution to this work. The authors would like to thank Juliette Siegfried and her team at ServingMed.com for their editing of the manuscript.

Ethical conduct of research

This routine hospital care quality improvement research has been done in accordance with the Spanish Personal Data Protection Law and under the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki for all human investigations.

Contributors

Program concept and design: E.R., J.F. Data acquisition and entry: N.M.C., H.Y.T., M.M., A.M.B., E.T., J.G.R. Analysis and interpretation of data were carried out by E.R., T.B., R.C., A.F., J.G.R., P.H., and E.T. and verified by A.J.C. Drafting of the manuscript: E.R., N.M.C., and A.J.C. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: E.R., J.F.

Ramírez, E. , Medrano‐Casique, N. , Tong, H. Y. , Bellón, T. , Cabañas, R. , Fiandor, A. , González‐Ramos, J. , Herranz, P. , Trigo, E. , Muñoz, M. , Borobia, A. M. , Carcas, A. J. , and Frías, J. (2017) Eosinophilic drug reactions detected by a prospective pharmacovigilance programme in a tertiary hospital. Br J Clin Pharmacol, 83: 400–415. doi: 10.1111/bcp.13096.

Contributor Information

Elena Ramírez, Email: elena.ramirez@inv.uam.es.

Jesús Frías, Email: jesus.frias@uam.es.

References

- 1. Southan C, Sharman JL, Benson HE, Faccenda E, Pawson AJ, Alexander SP, et al. The IUPHAR/BPS Guide to PHARMACOLOGY in 2016: towards curated quantitative interactions between 1300 protein targets and 6000 ligands. Nucl Acids Res 2016; 44: D1054–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Tefferi A, Patnaik MM, Pardanani A. Eosinophilia: secondary, clonal and idiopathic. Br J Haematol 2006; 133: 468–492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Romagosa R, Kapoor S, Sanders J, Berman B. Inpatient adverse cutaneous drug eruptions and eosinophilia. Arch Dermatol 2001; 137: 511–512. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Pichler WJ. Delayed drug hypersensitivity reactions. Ann Intern Med 2003; 139: 683–693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Takatsu K, Nakajima H. IL‐5 and eosinophilia. Curr Opin Immunol 2008; 20: 288–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kouro T, Takatsu K. IL‐5 and eosinophil‐mediated inflammation: from discovery to therapy. Int Immunol 2009; 21: 1303–1309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Jung YJ, Woo SY, Jang MH, Miyasaka M, Ryu KH, Park HK, et al. Human eosinophils show chemotaxis to lymphoid chemokines and exhibit antigen‐presenting‐cell‐like properties upon stimulation with IFN‐gamma, IL‐3 and GM‐CSF. Int Arch Allergy Immunol 2008; 146: 227–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Pecaric‐Petkovic T, Didichenko SA, Kaempfer S, Spiegl N, Dahinden CA. Human basophils and eosinophils are the direct target leukocytes of the novel IL‐1 family member IL‐33. Blood 2009; 113: 1526–1534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ramirez E, Carcas AJ, Borobia AM, Lei SH, Piñana E, Fudio S, et al. Pharmacovigilance program from laboratory signals for the detection and reporting of serious adverse drug reactions in hospitalized patients. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2010; 87: 74–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Organic law 15/1999 of 13 December 1999 on the Protection of Personal Data (BOE núm. 298, de 14–12‐1999, pp. 43088–43099).

- 11. Brigden ML. A practical workup for eosinophilia. You can investigate the most likely causes right in your office. Postgrad Med 1999; 105: 193–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. ICH Guideline on E2D Postapproval Safety Data Management: Definitions and Standards for Expedited Reporting. London, 20 November 2003 CPMP/ICH/3945/03. Available at http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Scientific_guideline/2009/09/WC500002807.pdf (last accessed 24 September 2016).

- 13. Kardaun SH, Sidoroff A, Valeyrie‐Allanore L, Halevy S, Davidovici BB, Mockenhaupt M, et al. Variability in the clinical pattern of cutaneous side‐effects of drugs with systemic symptoms: does a DRESS syndrome really exist? Br J Dermatol 2007; 156: 609–611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Capellá D, Laporte JR. La notificación espontánea de reacciones adversas a medicamentos In: Principios de Epidemiología del Medicamento, 2nd edn, eds Laporte JAR, Tognoni G. Barcelona: Masson‐Salvat, 1993; 147–170. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Pérez Arellano JL, Pardo J, Hernández Cabrera M, Carranza C, Angel Moreno A, Muro A. Eosinophilia: a practical approach. An Med Interna 2004; 21: 244–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Barbaud A. Place of drug skin tests in investigating systemic cutaneous drug reactions In: Drug Hypersensitivity, ed Pichler WJ. Basel: Karger, 2007; 366–379. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Barbaud A, Goncalo M, Bruynzeel D, Bircher A. Guidelines for performing skin tests with drugs in the investigation of cutaneous adverse reactions. Contact Dermatitis 2001; 45: 321–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Yan BM, Shaffer EA. Primary eosinophilic disorders of the gastrointestinal tract. Gut 2009; 58: 721–732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Jacobsen EA, Taranova AG, Lee NA, Lee JJ. Eosinophils: singularly destructive effector cells or purveyors of immunoregulation? J Allergy Clin Immunol 2007; 119: 1313–1320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Cormier SA, Taranova AG, Bedient C, Nguyen T, Protheroe C, Pero R, et al. Pivotal advance: eosinophil infiltration of solid tumors is an early and persistent inflammatory host response. J Leukoc Biol 2006; 79: 1131–1139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Fabre V, Beiting DP, Bliss SK, Gebreselassie NG, Gagliardo LF, Lee NA, et al. Eosinophil deficiency compromises parasite survival in chronic nematode infection. J Immunol 2009; 182: 1577–1583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Medoff H, Barbero A. Total blood eosinophilic count in the newborn period. Pediatrics 1950; 6: 737–742. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Roufosse F, Weller PF. Practical approach to the patient with hypereosinophilia. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2010; 126: 39–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Weller P. Approach to the patient with eosinophilia. Uptodate, [online]. Available at http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.468.6336&rep=rep1&type=pdf (last accessed 6 September 2016).

- 25. Blumenthal KG, Youngster I, Rabideau DJ, Parker RA, Manning KS, Walensky RP, et al. Peripheral blood eosinophilia and hypersensitivity reactions among patients receiving outpatient parenteral antibiotics. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2015; 136: 1288–1294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Cacoub P, Musette P, Descamps V, Meyer O, Speirs C, Finzi L, et al. The DRESS syndrome: a literature review. Am J Med 2011; 124: 588–597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ramdial PK, Naidoo DK. Drug‐induced cutaneous pathology. J Clin Pathol 2009; 62: 493–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Shiohara T, Iijima M, Ikezawa Z, Hashimoto K. The diagnosis of a DRESS syndrome has been sufficiently established on the basis of typical clinical features and viral reactivations. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2007; 156: 1083–1084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Choudhary S, McLeod M, Torchia D, Romanelli P. Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS) syndrome. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol 2013; 6: 31–37. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Bocquet H, Bagot M, Roujeau JC. Drug‐induced pseudolymphoma and drug hypersensitivity syndrome (drug rush with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms: DRESS). Semin Cutan Med Surg 1996; 15: 250–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Takahashi R, Kano Y, Yamazaki Y, Kimishima M, Mizukawa Y, Shiohara T. Defective regulatory T cells in patients with severe drug eruptions: timing of the dysfunction is associated with the pathological phenotype and outcome. J Immunol 2009; 182: 8071–8079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Shiohara T, Kano Y, Takahashi R, Ishida T, Mizukawa Y. Drug‐induced hypersensitivity syndrome: recent advances in the diagnosis, pathogenesis and management. Chem Immunol Allergy 2012; 97: 122–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Chung WH, Hung SI, Chen YT. Human leukocyte antigens and drug hypersensitivity. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol 2007; 7: 317–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kardaun SH, Sekula P, Valeyrie‐Allanore L, Liss Y, Chu CY, Creamer D, et al. Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS): an original multisystem adverse drug reaction. Results from the prospective RegiSCAR study. Br J Dermatol 2013; 169: 1071–1080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Pavlos R, Mallal S, Ostrov D, Pompeu Y, Phillips E. Fever, rash, and systemic symptoms: understanding the role of virus and HLA in severe cutaneous drug allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2014; 2: 21–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Yang J, Yang X, Li M. Peripheral blood eosinophil counts predict the prognosis of drug eruptions. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol 2013; 23: 248–255. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Boccara O, Valeyrie‐Allanore L, Crickx B, Descamps V. Association of hypogammaglobulinemia with DRESS (drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms). Eur J Dermatol 2006; 16: 666–668. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Kano Y, Inaoka M, Shiohara T. Association between anticonvulsant hypersensitivity syndrome and human herpesvirus 6 reactivation and hypogammaglobulinemia. Arch Dermatol 2004; 140: 183–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]