Abstract

Objective

To evaluate the effect and safety of extracorporeal shockwave therapy (ESWT) on chronic pelvic pain syndrome (CPPS)/chronic abacterial prostatitis after failure of most other modalities of treatment, the maintenance of the treatment effect for up to one year post treatment and whether the patients are in need for further sessions.

Materials and methods

In a follow-up survey of 41 patients, the study inclusion criteria were CPPS patients who failed at least previously 3 modalities of treatment other than ESWT, who were treated by ESWT once a week for one month with a protocol of 2500 pulses at 1 bar over 13 min, Nonaddiction to drugs and narcotics. The exclusion criteria included being under treatment by another method another diagnosis such as prostate cancer, therapy plan alteration, and noninclination to continue this treatment. Then the patients were followed up at 2 weeks, 6 months and 12 months after finishing the course of ESWT. The study was designed as an open-label uncontrolled therapeutic clinical trial which was conducted in Jordan university hospital through the period 2015–2016. Data were compared using paired samples t-test.

Results

Of our total 55 patients 8 of them did not complete the study protocol, 6 of them had missed follow up over the whole follow up period and 41 patients were evaluated. The patient's age group ranged between 18 and 78 years with a mean age of 42 and a median age of 43. The mean of National Institutes of Health -Chronic Prostatitis Symptom Index (NIH-CPSI), the International Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS), American Urological Association Quality of Life Due to Urinary Symptoms (AUA QOL_US) and International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF) were evaluated pre and post ESWT at 2 weeks, 6 months and 12 months and it showed statistically significant improvement in all parameters with maintenance of the effect without any significant side-effect of the treatment over the 12 months.

Conclusions

The evidence in this study would support the safety and efficacy of ESWT in refractory cases of CPPS at least for one year post treatment.

Keywords: CPPS, ESWT, Chronic abacterial prostatitis, Extracorporeal shock wave therapy, Prostate

Highlights

-

•

Prostatitis is one of the most frequent outpatient urological diagnoses.

-

•

The quality of life of affected men can be greatly impaired.

-

•

Most of the available treatments are symptomatic treatments and do not treat the underlying cause.

-

•

ESWT showed to be a safe, and effective as a long term therapy in CPPS.

1. Introduction

Prostatitis is one of the most frequent outpatient urological diagnoses [1].

Most men have the abacterial form of chronic prostatitis, or chronic pelvic pain syndrome (CPPS) [2]. The quality of life of affected men can be greatly impaired, in particular by pain, and the impact on the quality of life is comparable to those after a heart attack, angina pectoris and Crohn's disease [3].

According to the National Institutes of Health (NIH) classification Table 1. [4], CPPS (type IIIB) is characterized by the lack of signs of infection in urine and sperm as well as by the specific symptoms. Routine diagnostic procedure is still debatable, and the clinical diagnosis of CPPS is made in light of complaints, microbiologic findings, and exclusion of more severe, relevant diseases [5].

Table 1.

Prostatitis classification of the National Institute of Health (NIH).

| Category I: Acute Bacterial Prostatitis | Characterized by sudden fever, perineal and suprapubic pain and voiding symptoms. The urine shows signs of a urinary tract infection. |

| Category II: Chronic Bacterial Prostatitis | Chronic bacterial prostatitis is characterized by symptoms for more than 3 months with recurrent bacterial urinary tract infection. |

| Category III: Chronic Pelvic Pain Syndrome | (CPPS) is characterized by pain and voiding symptoms for more than 3 months, without detection of bacterial pathogens using standard microbiological methods. The CPPS is divided into two subcategories: |

| Category IIIA: Inflammatory CPPS | White blood cells in prostate fluid, urine, seminal fluid. |

| Category IIIB: Noninflammatory CPPS | No white blood cells in prostate fluid, urine, seminal fluid. |

| Category IV: Asymptomatic Inflammatory Prostatitis | White blood cells in prostate fluid, urine, seminal fluid, prostatic tissue with no symptoms. |

Analgesics, anti-inflammatory agents, antibiotics, α-receptor blockers, and 5α-reductase inhibitors as a single or combination therapy were proposed for treatment of CPPS with variable success rates [6], [7], [8].

However, numerous patients face frustration from the inadequate effects of treatment following multiple repeated attempts to cure this disorder. Recently, multi-modal treatment approaches and the utilization of complementary and alternative medicine strategies not presently considered part of conventional medicine, have been suggested as potential treatment options for CPPS, biofeedback, acupuncture, hyperthermia, and phytotherapy for example [9], [10].

The pathophysiology of CPPS is not yet completely understood. Psychiatric and somatic factors possibly play roles; however, no infection or bacterial pathogen has been detected [11].

ESWT has long been used successfully in lithotripsy for the elimination of urinary calculi as a standard urological procedure, which was discovered upon application for urolithiasis by chance, independent of high or low-dose energy. The analgesic side effect of ESWT is an interesting phenomenon, although the underlying mechanisms are unclear, and ESWT has since become an increasingly popular therapeutic approach as an alternative option for the treatment of a number of soft tissue complaints [12], [13]. Orthopaedic pain syndromes, fractures, and wound healing disorders are successfully treated by low energy extracorporeal shock wave therapy (ESWT) [14].

Some authors have suggested that an empirical trial period of anti-microbial treatment may be attempted at first especially in the inflammatory subtypes of the condition due to the possibility of chronic bacterial prostatitis being misdiagnosed as chronic nonbacterial prostatitis (CNBP), [15], [16].

2. Materials and methods

The study inclusion criteria were as follows: Patients with type IIIB prostatitis/CPPS of at least one year duration and no evidence of bacteria in urinary and seminal fluid culture tests (criteria according NIH classification) who failed to respond to other traditional modalities of CPPS treatment and took a combination of at least one course lipophilic antibiotic, simple analgesia and alpha blocker were eligible for the study. In addition some patients were given a course or more of thermal therapy and prostatic massage before ESWT enrolment and non addiction to drugs and narcotics.

A renal and bladder ultrasound was done in all patients to check for bladder or lower ureteral stones and whenever indicated, a further work up was requested for ruling out any other urological pathologies. The exclusion criteria of this study included being under treatment by another method at the beginning of the study, alpha blockers were not allowed, another diagnosis such as prostate cancer during workup, therapy plan alteration, and noninclination to continue this project. Patients with one or multiple comorbidities were not excluded.

Prostate cancer (PCa) was ruled out clinically and serologically by digital rectal examination (DRE) and PSA prior to therapy. Prostate ultrasound was also performed to rule out other pathologies.

Because of the wide varieties and different treatment periods and courses received by patients for treatment of this condition prior to ESWT; it didn't seem meaningful to stratify patients according to these criteria.

The investigation was designed as an open-label uncontrolled therapeutic clinical trial which was conducted in Jordan university hospital through the period 2015–2016.

Informed consent was obtained from each subject after obtaining approval of the experimental protocol by the institutional review board in the University of Jordan.

Our 41 Patients who were included received one perineally applied ESWT treatment weekly (2500 pulses at one Bar of pressure and maximum total energy flow density: 0.25 mJ/mm2; frequency: 3 Hz) for one month. The device used for the study was an electropneumatic shock wave unit with a focused shock wave source (E-S.W.T Roland, pagani, Italy). The ESWT machine and probe are shown in Fig. 1, Fig. 2.

Fig. 1.

ESWT machine.

Fig. 2.

ESWT probe.

The follow-up included clinical examinations and the questionnaire-based reevaluation of quality of life and complaints after 2 weeks, 6 months and 12 months of completing the ESWT course.

The degree of pain was evaluated using the Visual Analog Scale (VAS, 0–10). CPPS-related complaints were investigated using the NIH-Chronic Prostatitis Symptom Index (NIH-CPSI). Micturition conditions were examined using the International Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS) and American Urological Association (AUA) Quality of Life Due to Urinary Symptoms (QOL_US); the International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF) was used for potency function.

The data sets were examined by descriptive analysis methods. Data were compared using paired samples t-test. The characteristic values, such as mean values plus or minus standard deviation (SD) are listed in Table 2. All statistical analyses were carried out using the statistical software package IBM SPSS Statistics 21.

Table 2.

Results: mean values.

| Parameter | Mean ± SD |

|---|---|

| IPSS(pre) | 17.4 ± 7.8 |

| IPSS(2wk) | 11.5 ± 7.6 |

| IPSS (6m) | 10.8 ± 7.8 |

| IPSS (12m) | 10.8 ± 7.5 |

| NIH_P(pre) | 12.2 ± 5.1 |

| NIH_P(2wk) | 8.1 ± 4.6 |

| NIH_P(6m) | 8.7 ± 5.7 |

| NIH_P(12m) | 9.0 ± 5.8 |

| NIH_U(pre) | 6.4 ± 2.7 |

| NIH_U(2wk) | 4.0± 2.9 |

| NIH_U(6m) | 3.7 ± 3.1 |

| NIH_U(12m) | 3.7 ± 3.1 |

| NIH_QOL (pre) | 9.1 ± 2.6 |

| NIH_QOL(2wk) | 6.4 ± 3.1 |

| NIH_QOL (6m) | 6.5 ± 3.5 |

| NIH_QOL (12m) | 6.7 ± 3.5 |

| NIH_T (pre) | 27.7 ± 7.6 |

| NIH_T (2wk) | 18.5 ± 9.0 |

| NIH_T (6m) | 18.9 ± 10.5 |

| NIH_T (12m) | 19.5 ± 10.4 |

| AUA QOL_US(pre) | 4.5 ± 1.3 |

| AUA QOL_US(2wk) | 2.8 ± 1.4 |

| AUA QOL_US(6m) | 2.9 ± 1.5 |

| AUA QOL_US(12m) | 3.0 ± 1.7 |

| IIEF (pre) | 16.5 ± 6.1 |

| IIEF (2wk) | 19.2 ± 4.8 |

| IIEF (6m) | 19.5 ± 5.0 |

| IIEF (12m) | 19.4 ± 5.3 |

3. Results

During the whole course of treatment no significant side effects encountered nor any type of analgesia were required. The patient's age group ranged between 18 and 78 years with a mean age of 42 and a median age of 43. The patients were not stratified according to the type of treatments received previously because of the diversity of modalities and small sample size.

The results of our analysis after completing the 4 week course of treatment showed statistically significant improvement in all of the aspects considered in the evaluation and for the whole follow up period and as shown on Table 3.

Table 3.

Results: changes in parameters.

| Parameter | P-value | 95% CI | Mean dif. | % Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IPSS(pre) – IPSS (2wk) | 0.000 | 3.9–7.7 | 5.8 | 34% |

| IPSS(pre) – IPSS (6m) | 0.000 | 4.5–8.6 | 6.5 | 38% |

| IPSS(pre) – IPSS (12m) | 0.000 | 4.4–8.7 | 6.5 | 38% |

| IPSS(2wk) – IPSS (6m) | 0.383 | −0.9–2.3 | 0.7 | 6% |

| IPSS(2wk) – IPSS (12m) | 0.417 | −1.0–2.4 | 0.7 | 6% |

| IPSS(6m) – IPSS (12m) | 1.000 | −0.5–0.5 | 0.0 | 0% |

| NIH_P(pre) - NIH_P(2wk) | 0.000 | 2.4–5.7 | 4.0 | 34% |

| NIH_P(pre) - NIH_P(6m) | 0.000 | 2.1–4.5 | 3.5 | 29% |

| NIH_P(pre) - NIH_P(12m) | 0.000 | 1.7–4.7 | 3.1 | 26% |

| NIH_P(2wk) - NIH_P(6m) | 0.461 | −2.1–1.0 | −0.5 | −7% |

| NIH_P(2wk) - NIH_P(12m) | 0.272 | −2.5–0.7 | −0.9 | −11% |

| NIH_P(6m) - NIH_P(12m) | 0.352 | −1.0–0.4 | −0.3 | −3% |

| NIH_U(pre) - NIH_U(2wk) | 0.000 | 1.5–3.2 | 2.3 | 38% |

| NIH_U(pre) - NIH_U(6m) | 0.000 | 1.7–3.7 | 2.7 | 42% |

| NIH_U(pre) - NIH_U(12m) | 0.000 | 1.7–3.7 | 2.7 | 42% |

| NIH_U(2wk) - NIH_U(6m) | 0.262 | −0.3–1.0 | 0.3 | 8% |

| NIH_U(2wk) - NIH_U(12m) | 0.321 | −0.3–1.0 | 0.3 | 8% |

| NIH_U(6m) - NIH_U(12m) | 0.785 | −0.2–0.2 | 0.0 | 0% |

| NIH_QOL (pre) - NIH_QOL (2wk) | 0.000 | 1.8–3.6 | 2.7 | 30% |

| NIH_ QOL (pre) - NIH_ QOL (6m) | 0.000 | 1.4–3.6 | 2.5 | 29% |

| NIH_ QOL (pre) - NIH_ QOL (12m) ((12m)(12m) | 0.000 | 1.2–3.4 | 2.3 | 26% |

| NIH_ QOL (2wk) - NIH_ QOL (6m) | 0.649 | −0.9–0.6 | −0.1 | −2% |

| NIH_ QOL (2wk) - NIH_ QOL (12m) | 0.372 | −1.2–0.5 | −0.3 | −5% |

| NIH_ QOL (6m) - NIH_ QOL (12m) | 0.435 | −0.7–0.3 | −0.2 | −3% |

| NIH_T(pre) - NIH_ T (2wk) | 0.000 | 5.9–12.3 | 9.1 | 33% |

| NIH_ T (pre) - NIH_ T (6m) | 0.000 | 5.7–11.8 | 8.7 | 32% |

| NIH_ T (pre) - NIH_ T (12m) | 0.000 | 5.0–11.4 | 8.2 | 30% |

| NIH_ T (2wk) - NIH_ T (6m) | 0.776 | −3.0–2.2 | −0.3 | −2% |

| NIH_ T (2wk) - NIH_ T (12m) | 0.511 | −3.8–1.9 | −0.9 | −5% |

| NIH_ T (6m) - NIH_ T (12m) | 0.407 | −2.0–0.8 | −0.6 | −3% |

| AUA QOL_US(pre) - AUA (2wk) (2wkQOL_US(2wk) | 0.000 | 1.2–2.2 | 1.7 | 38% |

| AUA QOL_US(pre) - AUA (6m) (9QOL_US(6m) | 0.000 | 1.0–2.1 | 1.6 | 36% |

| AUA QOL_US(pre) - AUA (12m) QOL_US(12m) | 0.000 | 0.9–2.1 | 1.5 | 33% |

| AUA QOL_US(2wk) - AUA (6m) QOL_US(6m) | 0.445 | −0.5–0.2 | −0.1 | −4% |

| AUA QOL_US(2wk) - AUA (12m) QOL_US(12m) | 0.298 | −0.6–0.2 | −0.2 | −7% |

| AUA QOL_US(6m) - AUA (12m) QOL_US(12m) | 0.584 | −0.3–0.2 | −0.1 | −3% |

| IIEF (pre) - IIEF(2wk) | 0.000 | −4.0–-1.4 | −2.7 | 16% |

| IIEF (pre) - IIEF(6m) | 0.001 | −4.7–−1.3 | −3.0 | 18% |

| IIEF (pre) - IIEF(12m) | 0.002 | −4.7–−1.2 | −2.9 | 18% |

| IIEF (2wk) - IIEF(6m) | 0.486 | −1.2–0.6 | −0.3 | 2% |

| IIEF (2wk) - IIEF(12m) | 0.695 | −1.5–1.0 | −0.2 | 1% |

| IIEF (6m) - IIEF(12m) | 0.808 | 0.5–0.7 | −0.7 | −1% |

As shown above the IPSS, AUA QOL_US, the NIH-CPSI which was analyzed separately for each domain along with the total score and the IIEF all showed significant improvement with a P-value of 0.000 at week 2. And the effect of treatment was preserved throughout the whole period of study (6 months and 12 months).

Comparing parameters on 2 weeks, 6 months and 12 months the IPSS and NIH-CPSI_Urination domain showed marked improvement at week 2 with the maximum improvement achieved at 6 months then the effect stabilized till 12 months, but without statistically significant effect after 2 weeks.

On the other hand the other parameters showed the maximum effect at 2 weeks but slight deterioration was noticed at 6 months and 12 months, all without statistically significant changes after 2 weeks.

Best parameters to improve at 2 weeks were NIH-CPSI_Urination domain and AUA QOL_US both by 38% and the best to improve at 12 months was NIH-CPSI_Urination domain by 42%.

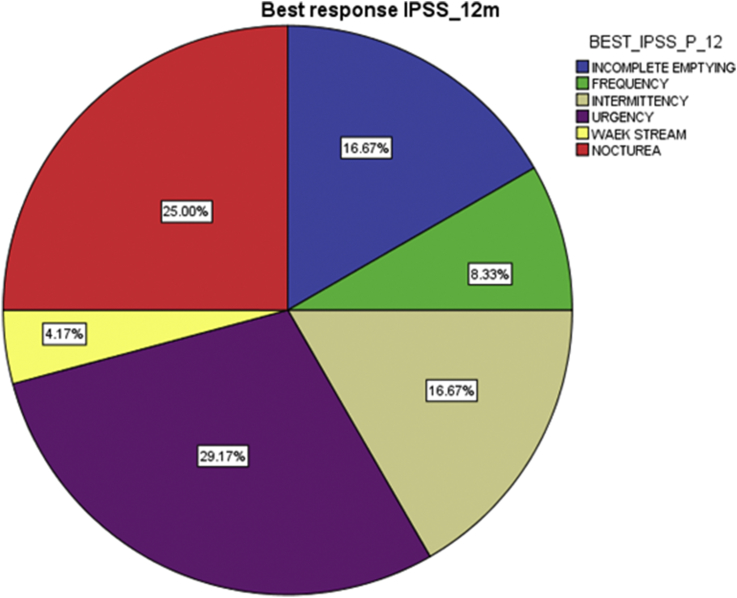

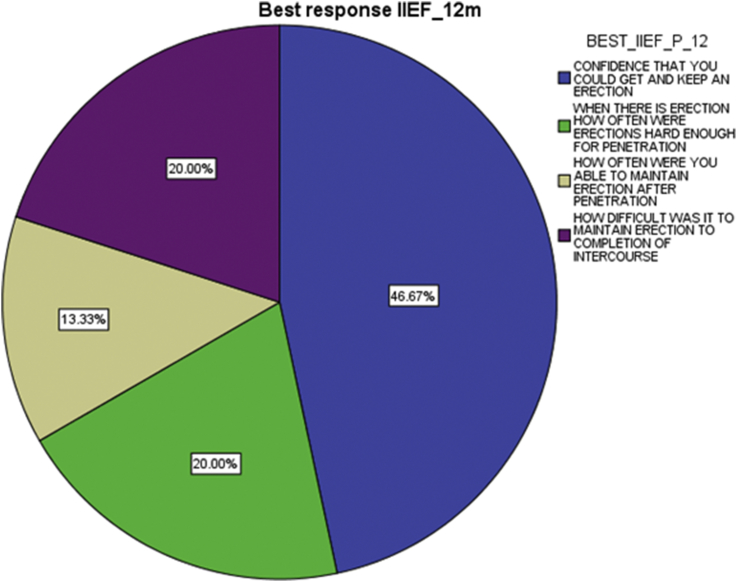

Best response in patients who showed improvement in the IPSS and IIEF was looked for at 2 weeks, 6 months and 12 months and showed the following:

IPSS best response at 2 weeks, 6 months and 12 months (Fig. 3) was urgency (34.5%, 28% and 29.2% respectively), and the IIEF best response at the same intervals (Fig. 4) was confidence that the patient could get and keep an erection (50%, 50% and 46.7% respectively).

Fig. 3.

Best response IPSS on 12 months.

Fig. 4.

Best response IIEF on 12 months.

4. Discussion

CPPS remains of unknown etiology which makes the treatment difficult and commonly insufficient. Most of the available treatments are symptomatic treatments and do not treat the underlying cause.

The suggested mechanisms of ESWT are currently under investigation. The electropneumatic shockwaves generated to the prostate perineally transform into biochemical signals in a process called mechanotransduction, this will hyperstimulate nocicepters and interrupt nerve impulses that carry pain sensation. On the other hand it will generate a cavitation bubbles that on popping will regenerate secondary energy waves known as microjets that cause again mechanical forces and increase local microvascularity [17].

After the follow-up of 12 months after completing the course of ESWT and comparing the IPSS, AUA QOL_US, NIH_CPPS and IIEF, marked improvements were noticed. Our study comes to support many other similar studies performed in different ways.

According to our literature review In 2 recent studies by Zimmermann et al., in first study [18]. they showed statistically significant improvements in pain and QOL after ESWT although voiding conditions, improved but with no statistical significance. In their later one [17], they found that All 30 patients in the verum group showed statistically significant improvement of pain, QOL, and voiding conditions following ESWT in comparison to the placebo group. In another study Moayednia et al. [19], randomized 40 patients with CPPS into a treatment and sham groups and found ESWT to be safe and effective therapy in CPPS in short-term follow-up but its long-term efficacy was not supported by this study, in contrast to our study in which the long term efficacy of ESWT was maintained over a 12 month period, although some of the effect was lost after 2 weeks but not to a statistically significant level and when compared to prior to treatment with ESWT will stay effective. Yan et al. [20], randomized study with 80 CPPS patients, NIH-CPSI, QOL and the pain domain scores significantly improved compared to the baseline at all post treatment time points in ESWT group.

In our study, the numbers of shock waves and the energy level were empirical. The selection of the number of treatments, the treatment intervals, and the number of pulses per session was made according to clinical studies of previous applications, It is still unclear the formula which should be used in the treatment protocol such as whether to increase the intervals between sessions or the number of sessions themselves and what energy or frequency will give the best long last results with the minimal side effects [17].

The fact that no significant side-effects were noted during and after treatment with the ease of application as an out-patient treatment and the long term efficacy, all encourage its use. However further follow up is still needed to monitor if there is any side-effects in the future.

The strength of our study lies in the fact that a long term follow up for the patients (over one year) was performed, all of our included patients have failed all other traditional modalities of treatments (combined alpha blocker, simple analgesia and antibiotics), and some of them even failed further modalities such as (thermotherapy and prostatic massage). Also, this investigation has been performed by an independent center with members who had no personal interest in the establishment of this new therapy.

The weakness of our study was its nature as an open-label clinical trial with the lack of a controlled group to compare with and a small sample size.

The evidence in this study would support the safety and efficacy of ESWT in refractory cases of CPPS at least for one year post treatment, although its long-term efficacy was not supported by many other studies and more comprehensive follow-up is essential.

ESWT is cost effective, easily conducted, and avoids the systemic side effects of other treatments being a local therapy with the possibility of repeating the treatment protocol at any time. Also it can be performed on an out-patient basis with little expenditure in terms of either time or personnel.

Ethical approval

Informed consent was obtained from each subject after obtaining approval of the experimental protocol by the institutional review board in the University of Jordan.

Ref Number:13008.

Sources of funding

None.

Author contribution

All authors have contributed significantly and as following:

Study concept and design: Ghazi Al Edwan.

Acquisition of data: Muheilan Mustafa Muheilan, Omar Nabeeh M. Atta.

Analysis and interpretation of data: Muheilan Mustafa Muheilan, Omar Nabeeh M. Atta.

Drafting of the manuscript: Muheilan Mustafa Muheilan, Omar Nabeeh M. Atta.

Statistical analysis: Muheilan Mustafa Muheilan.

Supervision: Ghazi Al Edwan.

Obtaining funding: None.

Conflicts of interest

We have no conflict of interest to disclose.

Guarantor

Ghazi Mohammad Al Edwan MD.

Research registration unique identifying number (UIN)

Researchregistry1664.

References

- 1.McNaughton-Collins M., MacDonald R., Wilt T.J. Diagnosis and treatment of chronic abacterial prostatitis: a systematic review. Ann. Intern Med. 2000;133:367–381. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-133-5-200009050-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nickel J.C. Classification and diagnosis of prostatitis: a gold standard? Andrologia. 2003;35:160–167. doi: 10.1046/j.1439-0272.2003.00557.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McNaughton Collins M., Pontari M.A., O'Leary M.P. Quality of life is impaired in men with chronic prostatitis: the chronic prostatitis collaborative research network. J. Gen. Intern Med. 2001;16:656–662. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2001.01223.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Krieger J.N., Nyberg L.J., Nickel J.C. NIH consensus definition and classification of prostatitis. JAMA. 1999;282:236–237. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.3.236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weidner W., Anderson R.U. Evaluation of acute and chronic bacterial prostatitis and diagnostic management of chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome with special reference to infection/inflammation. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents. 2008;31(Suppl. 1):91–95. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2007.07.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Anothaisintawee T., Attia J., Nickel J.C. Management of chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2011;305(1):78–86. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nickel J.C., Downey J., Clark J. Levofloxacin for chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome in men: a randomized placebo-controlled multicenter trial. Urology. 2003;62(4):614–617. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(03)00583-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nickel J.C., Krieger J.N., McNaughton-Collins M. Alfuzosin and symptoms of chronic prostatitis-chronic pelvic pain syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 2008;359(25):2663–2673. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0803240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Capodice J.L., Bemis D.L., Buttyan R., Kaplan S.A., Katz A.E. Complementary and alternative medicine for chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2005;2:495–501. doi: 10.1093/ecam/neh128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nickel J.C., Sorensen R. Transurethral microwave thermotherapy for nonbacterial prostatitis: a randomized double-blind sham controlled study using new prostatitis specific assessment questionnaires. J. Urol. 1996;155(6):1950–1955. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(01)66056-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pontari M.A., Ruggieri M.R. Mechanisms in prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome. J. Urol. 2004;172(3):839–845. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000136002.76898.04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chow G.K., Streem S.B. Extracorporeal lithotripsy. Update on technology. Urol. Clin. North Am. 2000;27:315–322. doi: 10.1016/s0094-0143(05)70260-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chow I.H., Cheing G.L. Comparison of different energy densities of extracorporeal shock wave therapy (ESWT) for the management of chronic heel pain. Clin. Rehabil. 2007;21:131–141. doi: 10.1177/0269215506069244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Manganotti P., Amelio E. Long term effect of shock wave therapy on upper limb hypertonia in patients affected by stroke. Stroke. 2005;36:1967–1971. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000177880.06663.5c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Krhen I., Skerk V., Schönwald S., Mareković Z. Classification, diagnosis and reatment of prostatitis syndrome. Lijec. Vjesn. 2002;124:89–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lipsky B.A. Prostatitis and urinary tract infection in men: What's new; what's true? Am. J. Med. 1999;106:327–334. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(99)00017-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zimmermann R., Cumpanas A., Miclea F., Janetschek G. Extracorporeal shock wave therapy for the treatment of chronic pelvic pain syndrome inmales: randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Eur. Urol. 2009 Sep;56(3):418–424. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2009.03.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zimmermann R., Cumpanas A., Hoeltl L., Janetschek G., Stenzl A., Miclea F. Extracorporeal shock-wave therapy for treating chronic pelvic pain syndrome: a feasibility study and the first clinical results. BJU Int. 2008;102:976–980. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2008.07742.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moayednia Amir, Haghdani Saeid, Khosrawi Saeid, Yousefi Elham, Vahdatpour Babak. Long-term effect of extracorporeal shock wave therapy on the treatment of chronic pelvic pain syndrome due to nonbacterial prostatitis. J. Res. Med. Sci. 2014 Apr;19(4):293–296. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yan X., Yang G., Cheng L., Chen M., Cheng X., Chai Y. Effect of extracorporeal shock wave therapy on diabetic chronic wound healing and its histological features. Zhongguo Xiu Fu Chong Jian Wai Ke Za Zhi. 2012;26:961–967. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]