Abstract

Spontaneous rectus sheath haematomas and cough secondary to losartan are individually rare conditions. Abdominal wall haematomas present with abdominal pain and abdominal mass. Most patients are managed conservatively; Surgery or embolisation is indicated for shock, infection, rupture into the peritoneum or intractable pain. This is a man aged 65 years presented with dry cough and right-sided abdominal pain. He started losartan a few weeks prior to the onset of cough and had been on rivaroxaban for prior deep venous thrombosis. The right side of his abdomen was distended, bruised and tender. His haemoglobin dropped from 13.3to 9.5 g/dL. CT abdomen/pelvis showed a large 14.5×9.1×4.5 cm haematoma within the right lateral rectus muscle. His only risk factor for developing rectus sheath haematoma was cough in the setting of anticoagulation. Dry cough due to angiotensin receptor blockers is rare, but can have very serious consequences.

Background

Spontaneous rectus sheath haematoma is a rare condition and 29% of such cases are caused by cough. Owing to its rarity, it is clinically unfamiliar and can be easily missed or confused with other acute abdominal conditions. Early diagnosis is necessary to prevent life-threatening complications like haemorrhagic shock and death. Most cases are treated conservatively with pain management and blood transfusions. Surgery or vascular embolisation is reserved for life-threatening situations. Here, we report a rare and first case of rectus sheath haematoma as the result of cough caused by angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs). This case emphasises the importance of keeping in mind the rare side effects of medications and rare complications of such side effects in an appropriate clinical context. Our patient developed an ARBs-induced cough, which led to the development of rectus sheath haematoma in the clinical context of being anticoagulated with rivaroxaban.

Case presentation

A man aged 65 years with a medical history of metabolic syndrome, deep vein thrombosis (DVT) of lower extremities and pulmonary embolism (PE) presented with right-sided abdominal pain for 1 week. The pain was dull and aching. It radiated to the right lower quadrant and to the suprapubic region. This was associated with abdominal tightness and early satiety. The pain was aggravated by coughing, eating, movement and external pressure on that part of his body. He also reported of a dry cough that started 1 week prior to abdominal pain onset. He had no other associated respiratory symptoms. He felt like he was being punched in the abdomen with every coughing episode. He was on losartan for hypertension which was started few weeks prior to the onset of cough. He was also on therapeutic anticoagulation with rivaroxaban for DVT and PE. He visited his primary care provider for these symptoms a few days prior to this hospital presentation and was prescribed amoxicillin and antitussives with no improvement. His cough and abdominal pain continued to intensify which prompted his hospital visit.

Vital signs were normal. On inspection, his abdomen was asymmetric with worse distention on the right than on the left (figure 1). Multiple small bruises were noted on his abdomen. He also had a large bruise on his suprapubic region extending down to the penile shaft (figure 2), which he noted a few days after onset of the cough. His abdomen was tender and firm to touch on the right side.

Figure 1.

Abdominal distention on the right side with a bruise over the epigastric area.

Figure 2.

A bruise over the suprapubic region extending down to the penile shaft.

Investigations

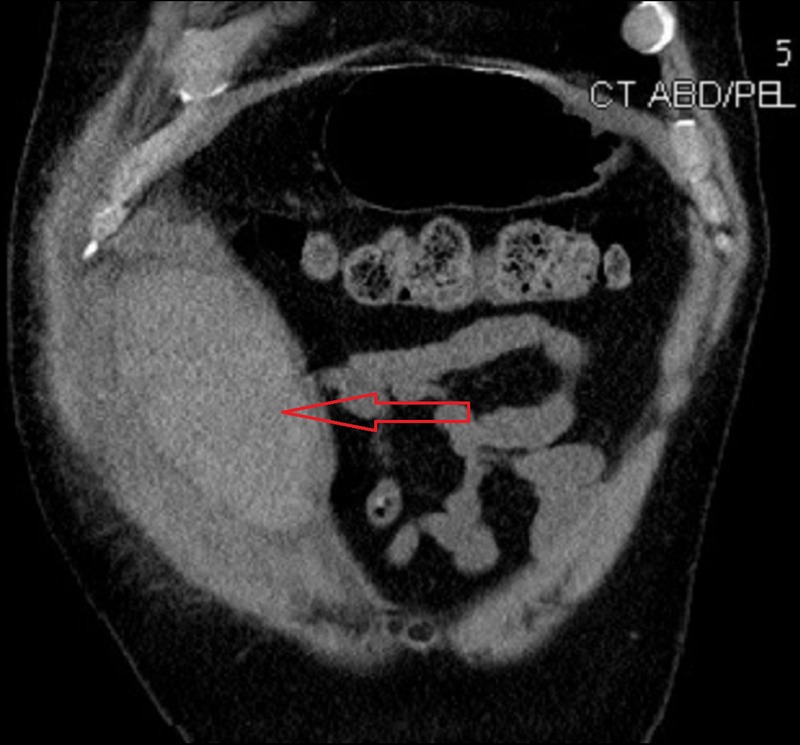

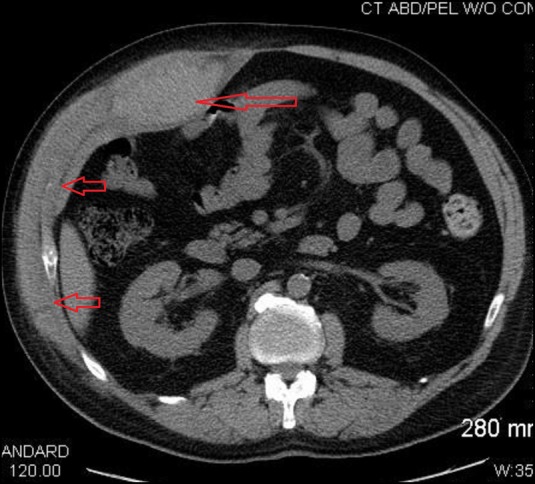

Laboratory findings were significant for haemoglobin of 9.5 g/dL, decreased from a prior recent value of 13.3 g/dL. His white count, platelets and PT/INR were normal. Chest imaging was negative. CT abdomen/pelvis without contrast showed a large haematoma measuring 14.5×9.1×4.5 cm within the right lateral rectus muscle (figure 3) extending laterally into the intercostal muscles (figure 4) and inferiorly into the pelvis.

Figure 3.

CT abdomen coronal plane demonstrating a large haematoma within the right rectus sheath measuring 14.5×9.1 cm.

Figure 4.

CT abdomen transverse plane demonstrating a large haematoma measuring 9.1×4.5 cm in the right rectus sheath. Haematoma extending laterally into intercostal muscles.

Differential diagnosis

Other conditions to be considered with this clinical presentation are intra-abdominal haematomas, intestinal perforation, ruptured abdominal aneurysm, cholecystitis, abdominal wall infection, appendicitis and peritonitis.

Treatment

Losartan and rivaroxaban were discontinued. His cough persisted despite dextromethorphan, but did improve after intravenous morphine for pain. His cough gradually improved a few days after discontinuing losartan. Surgical consultation recommended no surgical interventions. He was transfused packed red blood cells and haemoglobin was closely monitored. He improved clinically with time and his haemoglobin stabilised.

Discussion

Dry cough occurs in ∼10% of patients taking ACE inhibitors.1 Cough due to ARBs is reported, but the frequency is much less.2 3 ARBs are commonly substituted for patients who develop cough with ACE inhibitors in clinical practice. According to the adverse drug reaction probability scale developed by Naranjo et al,4 our patient's cough was probably (he scored 6 out of 14 possible points) related to losartan. As described in this case, ARBs producing cough is rare but can lead to very serious complications.

Reported mechanisms for ACE inhibitor-related cough include suppression of bradykinin dehydrogenase and Kininase II, which degrade bradykinin. This leads to accumulation of bradykinin, substance P and prostaglandins producing cough. Notably, ARBs do not suppress ACE activity or inhibit bradykinin breakdown, and so cough is uncommon with these agents. The proposed mechanism of cough with ARBs is via AT1 receptor blockade subsequently activating AT2 receptors due to increased levels of circulating angiotensin II. AT2 receptor activation leads to activation of the bradykinin–prostaglandin–nitrous oxide cascade which causes cough.5

Spontaneous rectus sheath haematoma is a rare condition that presents with abdominal pain and abdominal distention in 84% of patients. It accounts for around 2% cases of acute abdominal pain.6 Rectus sheath haematoma can occur from either external trauma such as blunt injuries or from internal causes such as cough. Twenty-nine per cent of rectus sheath haematomas are caused by cough. The incidence is higher if stressors are associated with antiplatelet agents, anticoagulation agents like warfarin, enoxaparin, heparin or direct oral anticoagulants.7 8 According to a study performed by Anyfantakis et al,9 the most common predisposing factor for rectus sheath haematoma was anticoagulation. Other risk factors like pregnancy, Wegener's granulomatosis, collagen disorders and muscle disorders have also been reported.8 10 Bleeding most commonly occurs from the inferior epigastric artery. Other common sources are superior epigastric arteries, veins and inferior epigastric veins7 or direct tear of rectus muscles.6

In our case, the losartan-induced cough associated with rivaroxaban caused rectus sheath haematoma.11 Early diagnosis of rectus sheath haematoma is crucial in preventing complications and decreasing mortality. The mortality can go up from 4% to 25% in patients on anticoagulation treatment.6 Reported complications include haemorrhagic shock, infection and abdominal compartment syndrome.12 Although ultrasound is the initial test of choice, CT abdomen is the definitive test to identify the origin, location and extent of bleeding.6 Most of the cases (86%) are treated conservatively with intravenous fluids, rest, cessation of predisposing factors, blood transfusion and pain management.6 9 Approximately 8% of patients require surgery or embolisation. Surgery is indicated in cases of shock, infection, rupture into the peritoneum, abdominal compartment syndrome and intractable pain.6–9

Learning points.

Patients on polypharmacy and who are at high risk of bleeding should be educated about potential complications of individual medications prescribed to them, the cumulative effect of adverse events, related warning signs and the importance of seeking medical attention immediately.

Patients on anticoagulation presenting with abdominal pain should be evaluated for abdominal haematomas without delay. Providers should be able to recognise early signs, potential causative agents, monitor for complications and take immediate necessary steps like in our case holding cough-inducing agents and anticoagulants to prevent adverse events.

Rectus sheath haematoma is treated conservatively in haemodynamically stable patients with stable haemoglobin. If bleeding is uncontrolled or patients become unstable, interventional radiology-guided vascular embolisation or surgical repair is warranted.

Footnotes

Contributors: GT identified the condition, involved in literature search and prepared the manuscript. PT is responsible for drafting and revision. JS is responsible for editing manuscript and final revision. SA is responsible for literature search, expert opinion, revision and final approval of the draft.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Vidt DG. Can angiotensin II receptor blockers be used in patients who have developed a cough or angioedema as a result of taking an ACE inhibitor? Cleve Clin J Med 2001;68:189–90. 10.3949/ccjm.68.3.189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tolerability and quality of life in ARB-treated patients. Am J Manag Care 2005;11(13 Suppl):S392–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Benz J, Oshrain C, Henry D et al. Valsartan, a new angiotensin II receptor antagonist: a double-blind study comparing the incidence of cough with lisinopril and hydrochlorothiazide. J Clin Pharmacol 1997;37:101–7. 10.1002/j.1552-4604.1997.tb04767.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Naranjo CA, Busto U, Sellers EM et al. A method for estimating the probability of adverse drug reactions. Clin Pharmacol Ther 1981;30:239–45. 10.1038/clpt.1981.154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gohlke P, Pees C, Unger T. AT2 receptor stimulation increases aortic cyclic GMP in SHRSP by a kinin-dependent mechanism. Hypertension 1998;31(Pt 2):349–55. 10.1161/01.HYP.31.1.349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hatjipetrou A, Anyfantakis D, Kastanakis M. Rectus sheath hematoma: a review of the literature. Int J Surg 2015;13:267–71. 10.1016/j.ijsu.2014.12.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cherry WB, Mueller PS. Rectus sheath hematoma: review of 126 cases at a single institution. Medicine (Baltimore) 2006;85:105–10. 10.1097/01.md.0000216818.13067.5a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Patel S, Thyagarajan B, Lalani I. Spontaneous rectus sheath haematoma secondary to severe coughing in a patient with no other precipitating factors. BMJ Case Rep 2016;2016:pii:bcr2016214362 10.1136/bcr-2016-214362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Anyfantakis D, Kastanakis M, Petrakis G et al. Rectus sheath hematoma in a single secondary care institution: a retrospective study. Hernia 2015;19:509–12. 10.1007/s10029-013-1186-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sivagnanam K, Ladia V, Bhavsar V et al. Spontaneous rectus sheath hematoma: two variant cases. J La State Med Soc 2014;166:197–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chan P, Tomlinson B, Huang TY et al. Double-blind comparison of losartan, lisinopril, and metolazone in elderly hypertensive patients with previous angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor-induced cough. J Clin Pharmacol 1997;37:253–7. 10.1002/j.1552-4604.1997.tb04788.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jafferbhoy SF, Rustum Q, Shiwani MH. Abdominal compartment syndrome—a fatal complication from a rectus sheath haematoma. BMJ Case Rep 2012;2012 10.1136/bcr.12.2011.5332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]