Abstract

We describe the incorporation of a bicyclo[1.1.1]pentane moiety within two known LpPLA2 inhibitors to act as bioisosteric phenyl replacements. An efficient synthesis to the target compounds was enabled with a dichlorocarbene insertion into a bicyclo[1.1.0]butane system being the key transformation. Potency, physicochemical, and X-ray crystallographic data were obtained to compare the known inhibitors to their bioisosteric counterparts, which showed the isostere was well tolerated and positively impacted on the physicochemical profile.

Keywords: LpPLA2, bicyclo[1.1.1]pentane, bioisostere, darapladib, cardiovascular disease, physicochemical

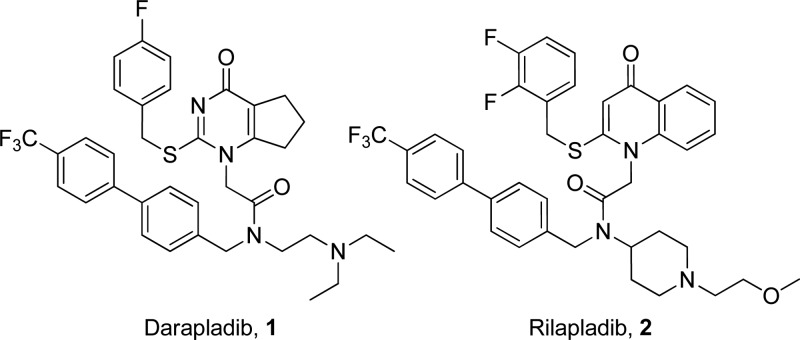

Lipoprotein-associated phospholipase A2 (LpPLA2) or platelet-activating factor acetylhydrolase (PAF-AH) has been extensively studied as a potential therapeutic target for the treatment of atherosclerosis1−6 and more recently in other diseases where vascular inflammation may play a role, e.g., diabetic macular edema and Alzheimer’s disease.7,8 A range of epidemiological and genetic evidence suggests that increased LpPLA2 concentration increases the risk of myocardial infarction (MI), ischemic stroke, and cardiac death in patients with stable cardiovascular disease (CVD).1,9−26 With considerable support for the hypothesis that LpPLA2 is associated with atherosclerosis, a range of inhibitors has been developed, with darapladib 1(27−29) and rilapladib 2(30) being well studied examples as both compounds have entered clinical trials (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Darapladib and rilapladib structures.

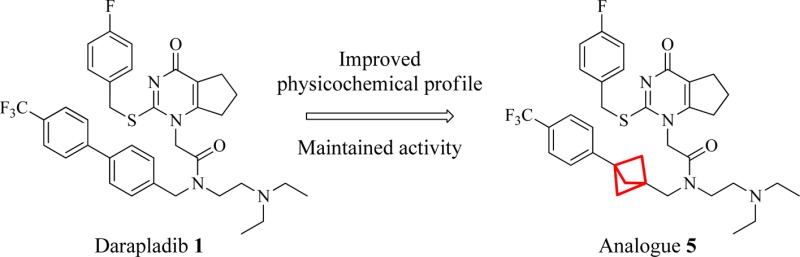

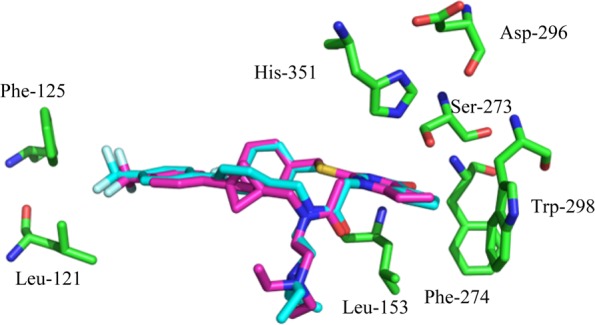

Compound 1 (Figure 1) shows excellent potency against LpPLA2 in in vitro assays with a pIC50 of 10.2.28 It is highly lipophilic (ChromLogD7.4: 6.3) but does have good artificial membrane permeability (AMP) of 230 nm/s. In vivo studies have consistently shown inhibition of the hydrolysis of LpPLA2 substrates in rats, dogs, rabbits, and pigs.28 The in vivo effects of 1 include reduced content of lyso-phosphatidylcholines (lyso-PCs) within atherosclerotic lesions, which are pro-inflammatory mediators.31 Both compounds 1 and 2 (Figure 1) bind to LpPLA2 in a similar manner with the cyclic amide/ketone mimicking the ester functionality of the enzyme substrates within the oxyanion hole.32,33 This blocks the active site where a Ser273, His351, and Asp296 form the catalytic triad and the backbone amide NHs of a Leu153 and Phe274 help to bind the substrate (Figure 4). The remaining functionality occupies lipophilic pockets adjacent to the active site. Compound 2 similarly displays excellent LpPLA2 potency in in vitro assays. Both inhibitors, however, exhibit suboptimal physicochemical profiles. They have high molecular weights, low aqueous solubility, and high property forecast indices (PFI); a risk indicator of developability.34 Improvement in the physicochemical properties of these compounds is therefore attractive. Methods of achieving this include introduction of polar functionality, removal of lipophilic groups, or replacement of suboptimal groups, such as aromatic rings with suitable bioisosteres, all of which were postulated to positively impact parameters such as PFI.34

Figure 4.

X-ray crystal structure of darapladib (blue) in LpPLA2 overlaid with modeled bioisosteric replacement (magenta).

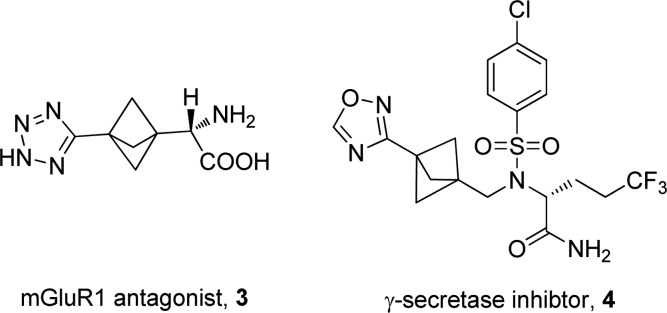

In this regard we targeted replacement of aromatic rings with saturated isosteres and became interested in the bicyclo[1.1.1]pentane system. There is a paucity of examples of the use of this template as a phenyl bioisostere35−37 including an mGluR1 receptor antagonist 3(38,39) and a γ-secretase inhibitor 4 (Figure 2).40 This is possibly due to the lack of tractable routes to the desired analogues. Despite this, we reasoned it could serve as a useful isostere of the aryl unit in the darapladib chemotype (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Drug compounds with bicyclo[1.1.1]pentane moiety.

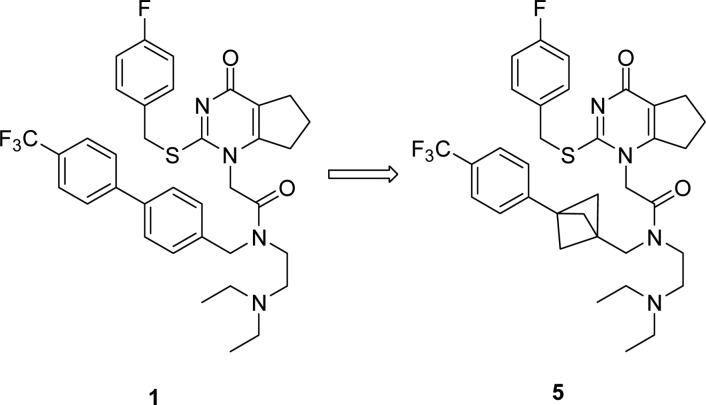

Figure 3.

Potential isosteric replacement for darapladib.

Accordingly, in this letter we illustrate the successful incorporation of the bicyclo[1.1.1]pentane into both the darapladib and rilapladib structures. The crystal structure of darapladib bound to LpPLA2, solved in-house and comparable to the structure recently published,33 indicates the internal aromatic of the biaryl system acts as a spacer, to allow access to a lipophilic pocket occupied by the trifluoromethylphenyl group. Modeling of the bicyclo[1.1.1]pentane moiety within LpPLA2 and comparison with the X-ray crystal structure of darapladib confirmed its potential viability as a replacement linker (Figure 4). It was envisaged that disrupting the planarity of the biaryl system would improve the physicochemical profile.

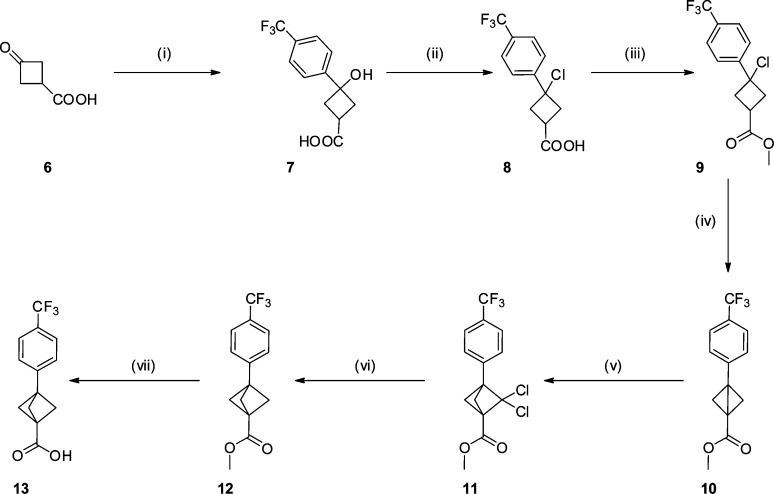

There are only two previously reported syntheses of the bicyclo[1.1.1]pentane moiety.41,42 These include utilizing a propellane as the key intermediate followed by a photochemical acetylation.43 Alternatively, addition of a carbene derivative to a bicyclo[1.1.0]butane followed by dechlorination can be employed.42 The latter was deemed more suitable for large scale chemistry and was therefore exploited in these syntheses.

The synthesis of key intermediate 13 commenced with an organometallic addition into the commercially available ketone 6 to furnish 7 as a ∼2:1 ratio of diastereomers in good yield. Alcohol 7 was converted to the chloride, and subsequent esterification and cyclization gave intermediate 10 with all steps proceeding in good to excellent yield.44 The bicyclo[1.1.0]butane derivative 10 was treated with a dichlorocarbene42 to generate 11 in a yield comparable with literature. Alternative carbene additions, including Simmons–Smith conditions, were investigated; however, these all proved unsuccessful. In a modification to the established process, dechlorination of the ring system was achieved utilizing a tin hydride replacement; tris(trimethylsilyl)silane (TTMSS).39,45 Dechlorination proceeded smoothly, and subsequent ester hydrolysis furnished the key carboxylic acid intermediate 13 in excellent yield (Scheme 1).

Scheme 1. Synthesis of Key Intermediate 13.

Reagents and conditions: (i) 4-bromotrifluorotoluene, nBuLi, THF, −78 °C to rt, 77%; (ii) conc. HCl, PhMe, rt, sonication, 75%; (iii) HCl, MeOH, 1,4-dioxane, rt, quant.; (iv) NaH, THF, rt, 98%; (v) sodium trichloroacetate, tetrachloroethylene, diglyme, 120 to 140 °C, 38%; (vi) TTMSS, 1,1′-azobis(cyclohexanecarbonitrile), PhMe, 110 °C, 74%; (vii) LiOH, 1,4-dioxane, rt, 95%.

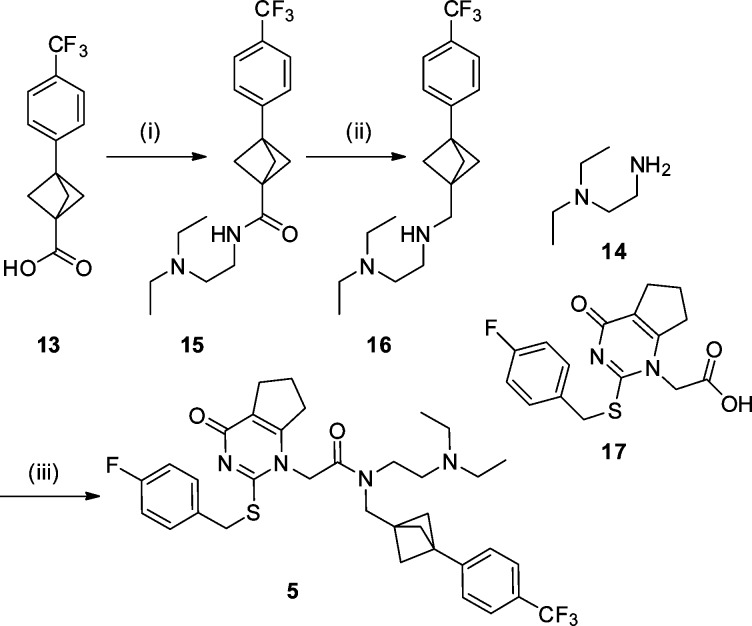

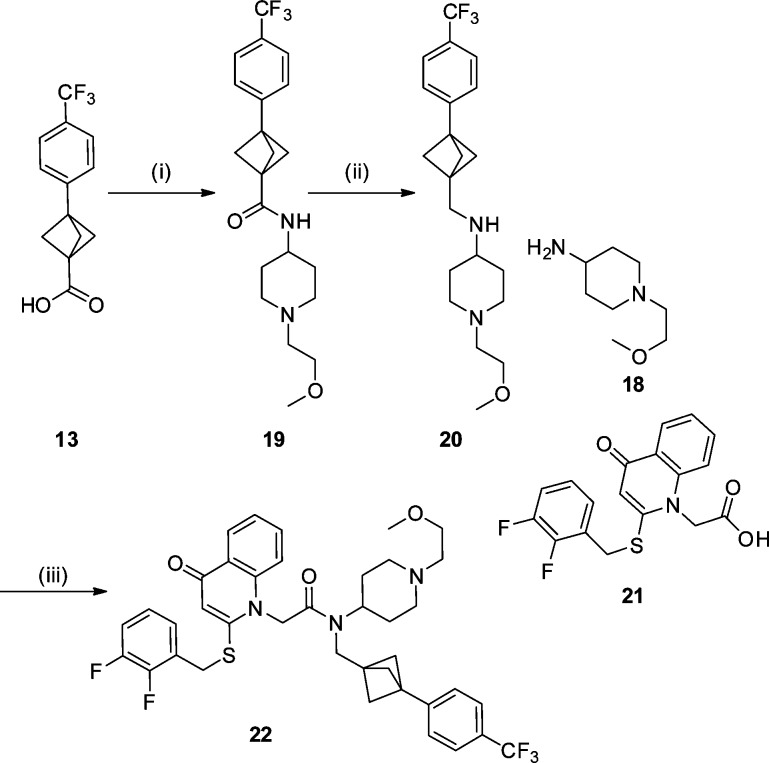

Intermediate 13 was then used in the synthesis of both LpPLA2 analogues. Amide coupling of 13 with commercially available amine 14 followed by reduction of the resulting amide 15 furnished intermediate 16 in good yield. Subsequent amide coupling of 16 with fragment 17(28) secured the darapladib analogue 5 (Scheme 2).

Scheme 2. Synthesis of Bioisosteric Darapladib Analogue 5.

Reagents and conditions: (i) 14, T3P, Et3N, EtOAc, rt, 99%; (ii) LiAlH4, THF, rt, 56%; (iii) 17, T3P, Et3N, rt, CH2Cl2, 60%.

Analogue 22 was synthesized in a similar fashion starting with an amide coupling of 13 with commercially available amine 18. Reduction46 of the resulting amide 19 to give intermediate 20, followed by amide coupling with fragment 21(47) produced the desired compound 22 in moderate yield (Scheme 3).

Scheme 3. Synthesis of Bioisosteric Rilapladib Analogue 22.

Reagents and conditions: (i) 18, T3P, Et3N, CH2Cl2, rt, 74%; (ii) [Ir(COE)2Cl]2, Et2SiH2, CH2Cl2, rt, 59%; (iii) 21, T3P, Et3N, CH2Cl2, rt, 53%.

With target compound 5 in hand, a comparison of its enzyme potency and physicochemical properties with that of 1 was undertaken. Data collected included LpPLA2 potency, solubility, ChromLogD7.4 (and associated PFI34), and AMP binding. Analogue 5 maintains high potency compared to that of its parent 1 with a pIC50 of 9.4 (1 pIC50 = 10.2). This suggested that the bioisosteric moiety was tolerated within the enzyme. In order to compare the binding mode of the bioisosteric analogue 5 with 1, an X-ray crystal structure of 5 in the LpPLA2 protein was generated.48 The structure, solved at ∼1.9 Å resolution, revealed a similar binding mode for both molecules (Figure 5), which is in agreement with the initial molecular modeling (Figure 4). The overlay of the two structures reveals that the bicyclo[1.1.1]pentane moiety slightly precludes the adjacent trifluorophenyl moiety extending as far toward Leu121 and Phe125, although these residues move slightly toward the inhibitor to fill the void. This suboptimal occupancy of the pocket could be an important factor in the slight drop-off in potency. Furthermore, the moiety has no effect on the key interactions within the oxyanion hole; retaining the carbonyl to backbone amide NH bonds with Leu153 and Phe274 residues and subsequently blocking the catalytic triad.

Figure 5.

X-ray crystal structure overlays of bound darapladib (blue) and analogue 5 (magenta) in LpPLA2.

With the binding mode of both progenitor compound 1 and analogue 5 confirmed, a comparison of the physicochemical profiles of both was conducted (Table 1).

Table 1. Summary of Physicochemical Data.

| 1 | 5 | 2 | 22 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| pIC50 | 10.2 | 9.4 | 9.652 | NTa |

| CLND (μM) | 8 | 74 | <1 | 32 |

| FaSSIF (μg/mL) | 399 | >1000 | 203 | 635 |

| AMP (nm/s)49 | 230 | 705 | NTa | NTa |

| ChromLogD7.4 | 6.3 | 7.0 | 6.74 | 7.06 |

| PFI | 10.3 | 10.0 | 11.74 | 11.06 |

NT = Not tested.

Analogue 5 showed an improved permeability of 705 nm/s from 230 nm/s49 over 1 and a 9-fold increase in kinetic solubility (74 vs 8 μM, respectively). However, this was accompanied by an undesired increase in lipophilicity, as determined by measured ChromLogD7.4, from 6.3 to 7.0. Calculation of Property Forecast Index (PFI), which is a summation of ChromLogD7.4 and number of aromatic rings,34 consequently indicated that compounds 1 and 5 have equivalent PFIs due to the removal of one aromatic ring. Thermodynamic fasted state simulated intestinal fluid (FaSSIF) solubility was also obtained with analogue 5 exhibiting an approximately 3-fold improvement (>1000 μg/mL compared to 399 μg/mL). This data is echoed by the comparison of 2 and 22, with 22 displaying improved solubility at pH 7.4 in both kinetic and thermodynamic measures as well as equivalent PFIs. Additionally, low clearance was observed for both 5 and 22 in a human liver microsomal assay, 1.22 and 0.76 mL/min/g, respectively. These data lend weight to the hypothesis that disrupting molecular planarity40,50,51 and reducing aromatic ring count34 can be beneficial to solubility and the overall pharmacokinetic profile.

In summary, the incorporation of the bioisoteric bicyclo[1.1.1]pentane replacement, within LpPLA2 analogues 5 and 22, respectively, has been enabled through a challenging synthesis. High potency was maintained for 5, and the binding mode was confirmed by X-ray crystallography.48 The bicyclo[1.1.1]pentane moiety imparts improved physicochemical properties compared to the known inhibitor. This confirms the utility of this group as a phenyl bioisostere in the context of LpPLA2 inhibition.

Acknowledgments

N.D.M. is grateful to GlaxoSmithKline R&D, Stevenage for Ph.D. studentship funding. We would also like to thank Sean Lynn for his help with the NMR assignments; Florent Potvain, Pascal Grondin, and Marie-Hélène Fouchet for running of the Lp-PLA2 assay; the Physicochemical Analysis Team; and Storm Hart and Thomas Clohessy for their intellectual input.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.6b00281.

Experimental procedures and analytical data for 5–22; X-ray crystallographic data (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Rosenson R. S.; Stafforini D. M. Modulation of Oxidative Stress, Inflammation, and Atherosclerosis by Lipoprotein-Associated Phospholipase A2. J. Lipid Res. 2012, 53 (9), 1767–1782. 10.1194/jlr.R024190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke J. E.; Dennis E. A. Phospholipase A2 Biochemistry. Cardiovasc. Drugs Ther. 2009, 23 (1), 49–71. 10.1007/s10557-008-6132-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaloske R. H.; Dennis E. A. The Phospholipase A2 Superfamily and Its Group Numbering System. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids 2006, 1761 (11), 1246–1259. 10.1016/j.bbalip.2006.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stremler K. E.; Stafforini D. M.; Prescott S. M.; McIntyre T. M. Human Plasma Platelet-Activating Factor Acetylhydrolase. Oxidatively Fragmented Phospholipids as Substrates. J. Biol. Chem. 1991, 266 (17), 11095–11103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinbrecher U. P.; Pritchard P. H. Hydrolysis of Phosphatidylcholine during LDL Oxidation Is Mediated by Platelet-Activating Factor Acetylhydrolase. J. Lipid Res. 1989, 30 (3), 305–315. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marathe G. K.; Harrison K. A.; Murphy R. C.; Prescott S. M.; Zimmerman G. A.; McIntyre T. M. Bioactive Phospholipid Oxidation Products. Free Radical Biol. Med. 2000, 28 (12), 1762–1770. 10.1016/S0891-5849(00)00234-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staurenghi G.; Ye L.; Magee M. H.; Danis R. P.; Wurzelmann J.; Adamson P.; McLaughlin M. M. Darapladib, a Lipoprotein-Associated Phospholipase A2 Inhibitor, in Diabetic Macular Edema: A 3-Month Placebo-Controlled Study. Ophthalmology 2015, 122 (5), 990–996. 10.1016/j.ophtha.2014.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maher-Edwards G.; De’Ath J.; Barnett C.; Lavrov A.; Lockhart A. A 24-Week Study to Evaluate the Effect of Rilapladib on Cognition and CSF Markers of Alzheimer’s Disease. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2014, 10 (June), 301–302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White H. Editorial: Why Inhibition of Lipoprotein-Associated Phospholipase A2 Has the Potential to Improve Patient Outcomes. Curr. Opin. Cardiol. 2010, 25 (4), 299–301. 10.1097/HCO.0b013e32833aaa94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipoprotein-Associated Phospholipase A2 and Risk of Coronary Disease, Stroke, and Mortality: Collaborative Analysis of 32 Prospective Studies. Lancet 2010, 375 (9725), 1536–1544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiechl S.; Willeit J.; Mayr M.; Viehweider B.; Oberhollenzer M.; Kronenberg F.; Wiedermann C. J.; Oberthaler S.; Xu Q.; Witztum J. L.; Tsimikas S. Oxidized Phospholipids, Lipoprotein(a), Lipoprotein-Associated Phospholipase A2 Activity, and 10-Year Cardiovascular Outcomes: Prospective Results From the Bruneck Study. Arterioscler., Thromb., Vasc. Biol. 2007, 27 (8), 1788–1795. 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.145805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsimikas S.; Mallat Z.; Talmud P. J.; Kastelein J. J. P.; Wareham N. J.; Sandhu M. S.; Miller E. R.; Benessiano J.; Tedgui A.; Witztum J. L.; Khaw K.-T.; Boekholdt S. M. Oxidation-Specific Biomarkers, Lipoprotein(a), and Risk of Fatal and Nonfatal Coronary Events. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2010, 56 (12), 946–955. 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.04.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryu S. K.; Mallat Z.; Benessiano J.; Tedgui A.; Olsson A. G.; Bao W.; Schwartz G. G.; Tsimikas S. Phospholipase A2 Enzymes, High-Dose Atorvastatin, and Prediction of Ischemic Events After Acute Coronary Syndromes. Circulation 2012, 125 (6), 757–766. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.063487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallat Z.; Lambeau G.; Tedgui a. Lipoprotein-Associated and Secreted Phospholipases A2 in Cardiovascular Disease: Roles as Biological Effectors and Biomarkers. Circulation 2010, 122 (21), 2183–2200. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.936393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenig W. Lipoprotein-Associated Phospholipase A2 Predicts Future Cardiovascular Events in Patients With Coronary Heart Disease Independently of Traditional Risk Factors, Markers of Inflammation, Renal Function, and Hemodynamic Stress. Arterioscler., Thromb., Vasc. Biol. 2006, 26 (7), 1586–1593. 10.1161/01.ATV.0000222983.73369.c8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabatine M. S.; Morrow D. A.; O’Donoghue M.; Jablonksi K. A.; Rice M. M.; Solomon S.; Rosenberg Y.; Domanski M. J.; Hsia J. Prognostic Utility of Lipoprotein-Associated Phospholipase A2 for Cardiovascular Outcomes in Patients With Stable Coronary Artery Disease. Arterioscler., Thromb., Vasc. Biol. 2007, 27 (11), 2463–2469. 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.151670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brilakis E. S. Association of Lipoprotein-Associated Phospholipase A2 Levels with Coronary Artery Disease Risk Factors, Angiographic Coronary Artery Disease, and Major Adverse Events at Follow-Up. Eur. Heart J. 2004, 26 (2), 137–144. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stafforini D. M.; Satoh K.; Atkinson D. L.; Tjoelker L. W.; Eberhardt C.; Yoshida H.; Imaizumi T.; Takamatsu S.; Zimmerman G. A.; McIntyre T. M.; Gray P. W.; Prescott S. M. Platelet-Activating Factor Acetylhydrolase Deficiency. A Missense Mutation near the Active Site of an Anti-Inflammatory Phospholipase. J. Clin. Invest. 1996, 97 (12), 2784–2791. 10.1172/JCI118733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miwa M.; Miyake T.; Yamanaka T.; Sugatani J.; Suzuki Y.; Sakata S.; Araki Y.; Matsumoto M. Characterization of Serum Platelet-Activating Factor (PAF) Acetylhydrolase. Correlation between Deficiency of Serum PAF Acetylhydrolase and Respiratory Symptoms in Asthmatic Children. J. Clin. Invest. 1988, 82 (6), 1983–1991. 10.1172/JCI113818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada Y.; Yoshida H.; Ichihara S.; Imaizumi T.; Satoh K.; Yokota M. Correlations between Plasma Platelet-Activating Factor Acetylhydrolase (PAF-AH) Activity and PAF-AH Genotype, Age, and Atherosclerosis in a Japanese Population. Atherosclerosis 2000, 150 (1), 209–216. 10.1016/S0021-9150(99)00385-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada Y.; Izawa H.; Ichihara S.; Takatsu F.; Ishihara H.; Hirayama H.; Sone T.; Tanaka M.; Yokota M. Prediction of the Risk of Myocardial Infarction from Polymorphisms in Candidate Genes. N. Engl. J. Med. 2002, 347 (24), 1916–1923. 10.1056/NEJMoa021445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada Y.; Ichihara S.; Fujimura T.; Yokota M. Identification of the G994--> T Missense in Exon 9 of the Plasma Platelet-Activating Factor Acetylhydrolase Gene as an Independent Risk Factor for Coronary Artery Disease in Japanese Men. Metab., Clin. Exp. 1998, 47 (2), 177–181. 10.1016/S0026-0495(98)90216-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unno N.; Nakamura T.; Kaneko H.; Uchiyama T.; Yamamoto N.; Sugatani J.; Miwa M.; Nakamura S. Plasma Platelet-Activating Factor Acetylhydrolase Deficiency Is Associated with Atherosclerotic Occlusive Disease in Japan. J. Vasc. Surg. 2000, 32 (2), 263–267. 10.1067/mva.2000.105670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiramoto M.; Yoshida H.; Imaizumi T.; Yoshimizu N.; Satoh K. A Mutation in Plasma Platelet-Activating Factor Acetylhydrolase (Val279-Phe) Is a Genetic Risk Factor for Stroke. Stroke 1997, 28 (12), 2417–2420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang Y.; Waterworth D.; Lee J.-E.; Song K.; Kim S.; Kim H.-S.; Park K. W.; Cho H.-J.; Oh I.-Y.; Park J. E.; Lee B.-S.; Ku H. J.; Shin D.-J.; Lee J. H.; Jee S. H.; Han B.-G.; Jang H.-Y.; Cho E.-Y.; Vallance P.; Whittaker J.; Cardon L.; Mooser V. Carriage of the V279F Null Allele within the Gene Encoding Lp-PLA2 Is Protective from Coronary Artery Disease in South Korean Males. PLoS One 2011, 6 (4), 18208–18214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang Y.; Kim O. Y.; Koh S. J.; Chae J. S.; Ko Y. G.; Kim J. Y.; Cho H.; Jeong T.-S.; Lee W. S.; Ordovas J. M.; Lee J. H. The Val279Phe Variant of the Lipoprotein-Associated Phospholipase A2 Gene Is Associated with Catalytic Activities and Cardiovascular Disease in Korean Men. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2006, 91 (9), 3521–3527. 10.1210/jc.2006-0116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darapladib for Preventing Ischemic Events in Stable Coronary Heart Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014, 370 (18), 1702–1711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackie J. A.; Bloomer J. C.; Brown M. J. B.; Cheng H.-Y.; Hammond B.; Hickey D. M. B.; Ife R. J.; Leach C. A.; Lewis V. A.; Macphee C. H.; Milliner K. J.; Moores K. E.; Pinto I. L.; Smith S. A.; Stansfield I. G.; Stanway S. J.; Taylor M. A.; Theobald C. J. The Identification of Clinical Candidate SB-480848: A Potent Inhibitor of Lipoprotein-Associated Phospholipase A2. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2003, 13 (6), 1067–1070. 10.1016/S0960-894X(03)00058-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Donoghue M. L.; Braunwald E.; White H. D.; Steen D. P.; Lukas M. A.; Tarka E.; Steg P. G.; Hochman J. S.; Bode C.; Maggioni A. P.; Im K.; Shannon J. B.; Davies R. Y.; Murphy S. A.; Crugnale S. E.; Wiviott S. D.; Bonaca M. P.; Watson D. F.; Weaver W. D.; Serruys P. W.; Cannon C. P. Effect of Darapladib on Major Coronary Events After an Acute Coronary Syndrome. Jama 2014, 312 (10), 1006. 10.1001/jama.2014.11061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tawakol A.; Singh P.; Rudd J. H. F.; Soffer J.; Cai G.; Vucic E.; Brannan S. P.; Tarka E. A.; Shaddinger B. C.; Sarov-Blat L.; Matthews P.; Subramanian S.; Farkouh M.; Fayad Z. A. Effect of Treatment for 12 Weeks with Rilapladib, a Lipoprotein-Associated Phospholipase A2 Inhibitor, on Arterial Inflammation as Assessed with 18F-Fluorodeoxyglucose-Positron Emission Tomography Imaging. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2014, 63 (1), 86–88. 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.07.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilensky R. L.; Shi Y.; Mohler E. R.; Hamamdzic D.; Burgert M. E.; Li J.; Postle A.; Fenning R. S.; Bollinger J. G.; Hoffman B. E.; Pelchovitz D. J.; Yang J.; Mirabile R. C.; Webb C. L.; Zhang L.; Zhang P.; Gelb M. H.; Walker M. C.; Zalewski A.; Macphee C. H. Inhibition of Lipoprotein-Associated Phospholipase A2 Reduces Complex Coronary Atherosclerotic Plaque Development. Nat. Med. 2008, 14 (10), 1059–1066. 10.1038/nm.1870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samanta U.; Bahnson B. J. Crystal Structure of Human Plasma Platelet-Activating Factor Acetylhydrolase: Structural Implication to Lipoprotein Binding and Catalysis. J. Biol. Chem. 2008, 283 (46), 31617–31624. 10.1074/jbc.M804750200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q.; Chen X.; Chen W.; Yuan X.; Su H.; Shen J.; Xu Y. Structural and Thermodynamic Characterization of Protein–Ligand Interactions Formed between Lipoprotein-Associated Phospholipase A2 and Inhibitors. J. Med. Chem. 2016, 59, 5115. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.6b00282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young R. J.; Green D. V. S.; Luscombe C. N.; Hill A. P. Getting Physical in Drug Discovery II: The Impact of Chromatographic Hydrophobicity Measurements and Aromaticity. Drug Discovery Today 2011, 16 (17–18), 822–830. 10.1016/j.drudis.2011.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews M. D.; Bagal S. K.; Gibson K. R.; Omoto K.; Ryckmans T.; Skerratt S. E.; Stupple P. A.. Pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidine Derivatives as Inhibitors of Tropomyosinrelated Kinases and Their Preparation and Use in the Treatment of Pain. WO2012137089, 2012.

- Bennett B. L.; Elsner J.; Erdman P.; Hilgraf R.; Lebrun L. A.; McCarrick M. .; Moghaddam M. F.; Nagy M. A.; Norris S.; Paisner D. A.; Sloss M. .; Romanow W. J.; Satoh Y.; Tikhe J.; Yoon W. H.; Delgrado M.. Preparation of Substituted Diaminocarboxamide and Diaminocarbonitrile Pyrimidines as JNK Pathway Inhibitors. WO2012145569, 2012.

- Hayashi K.; Watanabe T.; Toyama K.; Kamon J.; Minami M.; Uni M.; Nasu M.. Preparation of Tricyclic Heterocyclic Compounds as JAK Inhibitors. WO2013024895, 2012.

- Costantino G.; Maltoni K.; Marinozzi M.; Camaioni E.; Prezeau L.; Pin J.-P.; Pellicciari R. Synthesis and Biological Evaluation of 2-(3′-(1H-Tetrazol-5-yl)bicyclo[1.1.1]pent-1-Yl)glycine (S-TBPG), a Novel mGlu1 Receptor Antagonist. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2001, 9 (2), 221–227. 10.1016/S0968-0896(00)00270-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pellicciari R.; Filosa R.; Fulco M. C.; Marinozzi M.; Macchiarulo A.; Novak C.; Natalini B.; Hermit M. B.; Nielsen S.; Sager T. N.; Stensbøl T. B.; Thomsen C. Synthesis and Preliminary Biological Evaluation of 2′-substituted 2-(3′-carboxybicyclo[1.1.1]pentyl)glycine Derivatives as Group I Selective Metabotropic Glutamate Receptor Ligands. ChemMedChem 2006, 1 (3), 358–365. 10.1002/cmdc.200500071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stepan A. F.; Subramanyam C.; Efremov I. V.; Dutra J. K.; O’Sullivan T. J.; DiRico K. J.; McDonald W. S.; Won A.; Dorff P. H.; Nolan C. E.; Becker S. L.; Pustilnik L. R.; Riddell D. R.; Kauffman G. W.; Kormos B. L.; Zhang L.; Lu Y.; Capetta S. H.; Green M. E.; Karki K.; Sibley E.; Atchison K. P.; Hallgren A. J.; Oborski C. E.; Robshaw A. E.; Sneed B.; O’Donnell C. J. Application of the bicyclo[1.1.1]pentane Motif as a Nonclassical Phenyl Ring Bioisostere in the Design of a Potent and Orally Active γ-Secretase Inhibitor. J. Med. Chem. 2012, 55 (7), 3414–3424. 10.1021/jm300094u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belzner J.; Bunz U.; Semmler K.; Szeimies G.; Opitz K.; Schlüter A.-D. Concerning the Synthesis of [1.1.1]Propellane. Chem. Ber. 1989, 122 (2), 397–398. 10.1002/cber.19891220233. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Applequist D. E.; Renken T. L.; Wheeler J. W. Polar Substituent Effects in 1,3-Disubstituted bicyclo[1.1.1]pentanes. J. Org. Chem. 1982, 47 (25), 4985–4995. 10.1021/jo00146a031. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kaszynski P.; Michl J. A Practical Photochemical Synthesis of bicyclo[1.1.1]pentane-1,3-Dicarboxylic Acid. J. Org. Chem. 1988, 53 (19), 4593–4594. 10.1021/jo00254a038. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hall H. K.; Smith C. D.; Blanchard E. P.; Cherkofsky S. C.; Sieja J. B. Synthesis and Polymerization of Bridgehead-Substituted Bicyclobutanes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1971, 93 (1), 121–130. 10.1021/ja00730a022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chatgilialoglu C.; Griller D.; Lesage M. Tris(trimethylsilyl)silane. A New Reducing Agent. J. Org. Chem. 1988, 53 (15), 3641–3642. 10.1021/jo00250a051. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng C.; Brookhart M. Iridium-Catalyzed Reduction of Secondary Amides to Secondary Amines and Imines by Diethylsilane. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134 (28), 11304–11307. 10.1021/ja304547s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee M. Patent WO2013/30374 A1, 2013.

- Method and statistics provided in Supporting Information (pdb 5LP1).

- Darapladib permeability obtained at pH 7.05 and analogue 5 permeability obtained at pH 7.4.

- Nicolaou K. C.; Vourloumis D.; Totokotsopoulos S.; Papakyriakou A.; Karsunky H.; Fernando H.; Gavrilyuk J.; Webb D.; Stepan A. F. Synthesis and Biopharmaceutical Evaluation of Imatinib Analogues Featuring Unusual Structural Motifs. ChemMedChem 2016, 11, 31–37. 10.1002/cmdc.201500510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovering F.; Bikker J.; Humblet C. Escape From Flatland: Increasing Saturation as and Approach to Improving Clinical Success. J. Med. Chem. 2009, 52, 6752–6756. 10.1021/jm901241e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaddinger B. C.; Xu Y.; Roger J. H.; Macphee C. H.; Handel M.; Baidoo C. A.; Magee M.; Lepore J. J.; Sprecher D. L. Platelet Aggregation Unchanged by Lipoprotein-associated Phospholipase A2 Inhibition: Results from an In Vitro Study and Two Randomized Phase I Trials. PLoS One 2014, 9, e83094. 10.1371/journal.pone.0083094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.