A 55 year-old female with a history of depression, epilepsy, and severe alcohol and opiate dependence was admitted after a methadone overdose. In the days prior to this incident, she was drinking alcohol, and when her family intervened, she resorted to drinking Listerine. She had lost her job as a college professor for special education because of her substance dependence after failing several detoxification admissions and outpatient addiction treatment programs. She was successfully resuscitated and gradually recovered. One month later, she was cognitively intact and her neurological exam was notable only for mild facial dyskinesias, which also subsequently resolved. A brain MRI obtained few days after her overdose revealed bilateral infarcts of the internal segment of the Globus Pallidus (GPi) consistent with a hypoxic ischemic injury (Figure 1A–C); she had an unremarkable brain MRI two years prior to presentation. Interestingly, her substance dependence remitted since the overdose. Her alcohol and opiate cravings and her compulsive drug seeking resolved. She continues to be abstinent after ten years.

Figure 1.

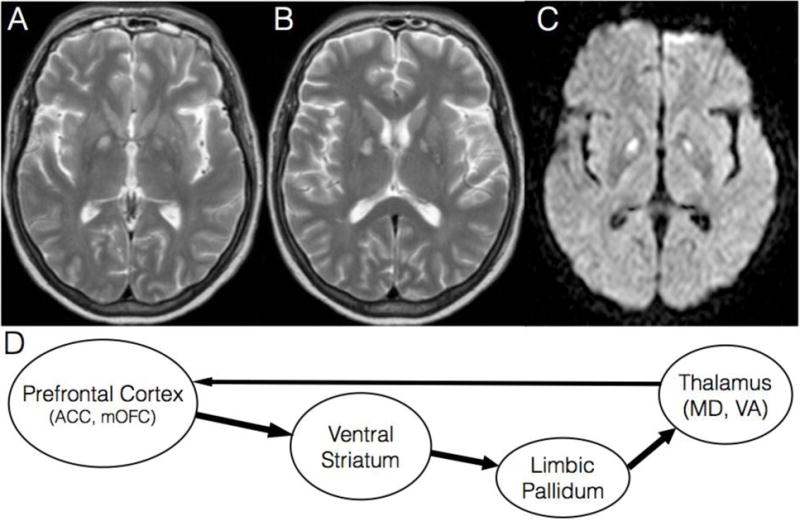

A–B. Axial brain MRI slices with T2 weighted sequence at the level of anterior commissure (A) and 5 mm dorsally (B) reveal hyper intense signal in the GPi bilaterally.

C. Diffusion weighted imaging (DWI) MRI sequence shows restricted diffusion in GPi bilaterally, corresponding to the lesions in A–B.

D. Extrapolated final common pathway for compulsive drug seeking based on the rodent animal model of relapse. This circuit is necessary and sufficient for drug seeking. ACC = anterior cingulate cortex, mOFC = medial orbitofrontal cortex; Ventral Striatum = nucleus accumbens, ventromedial caudate, ventral putamen; Limbic Pallidum = ventral pallidum, medial GPi, and rostromedial pole of GPe; MD = mediodorsal nucleus; VA = ventroanterior nucleus.

The GPi is supplied by the confluence of the anterior choroidal artery, perforating branches of the internal carotid artery, and perforating branches of the anterior cerebral artery1. Like other borderzone territories of the brain, the GPi is especially susceptible to hypoxic ischemic injury. At autopsy, 5–10% of opiate addicts have bilateral pallidal lesions from hypoxic ischemic injuries2.

The GPi, through its projections to the ventrolateral thalamic nucleus, has classically been associated with the direct and indirect basal ganglia circuits controlling motor activity. In addition, the medial aspect of the GPi (adjacent to the internal capsule) receives projections from the limbic striatum and in turn projects to the ventral anterior and centromedian thalamic nuclei, which are key nodes in the reward circuitry3 (Figure 1D). The ventral striatum projects densely to the limbic globus pallidus including the ventral pallidum (ventral to the anterior commissure), rostral pole of the external segment (GPe), and medial GPi, which collectively form one functional unit that we refer to as limbic pallidum4.

Reinstatement of compulsive drug seeking in addicted rodents after a period of abstinence (or extinction) is a powerful model of relapse to drug seeking in human addicts5. In this model, the limbic pallidum along with the medial prefrontal cortex and ventral striatum constitute the final common pathway necessary and sufficient for compulsive drug seeking5 (Figure 1D). Structural lesions or functional inactivation of any of these areas, including the limbic pallidum, block relapse to drug seeking5.

Deep brain stimulation (DBS) targeting the internal segment of the Globus Pallidus is currently approved for treatment of dystonias. The main advantage of DBS is its adjustability and reversibility. Interestingly, in animals models of obsessive compulsive disorders (OCD), DBS of the GPi was shown to reduce compulsive behaviors measured as lever presses in an operant box6. However, DBS of the GPi has not been tested in addiction models, despite the marked similarity of the underlying circuitry and behavioral compulsivity between OCD and addiction. Similarly, DBS studies in human addicts target the ventral striatum and subthalamic nucleus, but not the limbic pallidum6.

In the present case, we believe that bilateral ischemic GPi lesions after a methadone overdose contributed sustained remission from opiate and alcohol dependence. A similar case has been reported where bilateral pallidal injury after methadone overdose in a young man resulted in abstinence from drug use though this was in the setting of general anhedonia and ongoing extrapyramidal symptoms, which were not observed in our patient7. Our patient returned to her functional baseline and she is currently working as a special education specialist without any limitations. She has not exhibited any signs of substance, mood, anxiety, or personality disorders since the overdose. This is corroborated by her family and colleagues at work. This case is an experiment of nature that validates the addiction research literature in animal models where functional or structural lesions of the limbic pallidum block relapse to drug seeking. In addition, this case highlights the limbic pallidum, specifically the medial GPi as a new potential therapeutic target for DBS in the treatment of drug addiction.

Footnotes

Authors contributions:

Khaled Moussawi: conceived, wrote, and revised the manuscript.

Peter Kalivas: conceived and revised the manuscript.

Jong W. Lee: conceived and revised the manuscript.

Author Disclosures:

Khaled Moussawi: reports no disclosures.

Peter W. Kalivas: reports no disclosures.

Jong W. Lee: reports no disclosures.

References

- 1.Tatu L, Moulin T, Vuillier F, Bogousslavsky J. Arterial territories of the human brain. Front Neurol Neurosci. 2012;30:99–110. doi: 10.1159/000333602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andersen SN, Skullerud K. Hypoxic/ischaemic brain damage, especially pallidal lesions, in heroin addicts. Forensic Science International. 1999;102:51–59. doi: 10.1016/s0379-0738(99)00040-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tekin S, Cummings JL. Frontal–subcortical neuronal circuits and clinical neuropsychiatry. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2002;53:647–654. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(02)00428-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haber SN, Knutson B. The Reward Circuit: Linking Primate Anatomy and Human Imaging. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2009;35:4–26. doi: 10.1038/npp.2009.129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kalivas PW, Volkow ND. The neural basis of addiction: a pathology of motivation and choice. The American journal of psychiatry. 2005;162:1403–1413. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.8.1403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hamani C, Temel Y. Deep Brain Stimulation for Psychiatric Disease: Contributions and Validity of Animal Models. Science Translational Medicine. 2012;4:142rv8–142rv8. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3003722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miller JM, et al. Anhedonia after a selective bilateral lesion of the globus pallidus. The American journal of psychiatry. 2006;163:786–788. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.5.786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]