Abstract

A family of α-aryl-α-aminophosphonates and α-aryl-α-aminophosphine oxides was synthesized by the microwave-assisted solvent-free addition of dialkyl phosphites and diphenylphosphine oxide, respectively, to imines formed from benzaldehyde derivatives and primary amines. After optimization, the reactivity was mapped, and the fine mechanism was evaluated by DFT calculations. Two α-aminophosphonates were subjected to an X-ray study revealing a racemic dimer formation made through a N–H···O=P intermolecular hydrogen bridges pair.

Keywords: α-aryl-α-aminophosphine oxides, α-aryl-α-aminophosphonates, microwave, Pudovik reaction

Introduction

α-Aminophosphonates and related derivatives, considered as the structural analogues of α-amino acids, have significant importance, especially in medicinal [1–3] and agricultural chemistry [4–5], due to their potential biological activity. The two major synthetic routes towards α-aminophosphonate derivatives embrace the Kabachnik–Fields (phospha-Mannich) three-component condensation, where an amine, an aldehyde or ketone and a >P(O)H reagent, such as a dialkyl phosphite or a secondary phosphine oxide react in a one-pot manner [6–10], and the Pudovik (aza-Pudovik) reaction, in which a >P(O)H species is added on the double bond of imines [11–14]. In this article, the latter pathway is utilized for the synthesis of α-aryl-α-aminophosphonates and α-aryl-α-aminophosphine oxides. In most cases, the additions were carried out in the presence of a catalyst and solvent. The use of many types of catalysts, such as acids (HCOOH) [15] or bases (NaOH [16], 1,8-diazabicyclo[5.4.0]undec-7-ene (DBU) [17], tetramethylguanidine (TMG) [18–19]), p-toluenesulfonyl chloride [20], metal salts (MgSO4) [21], CdI2 [22]), metal complexes (BF3·EtO2 [23–24], t-PcAlCl [15]), and phase-transfer catalysts [25] were reported. The enantioselective hydrophosphonylation of imines was also described, where chiral catalysts were applied in various solvents [26–32]. There are a few examples, where the reactions were performed in a solvent in the absence of any catalyst [33–38], while in a few cases the catalysts, i.e., PTSA [39], Na [40], TEA [21] or MoO2Cl2 [41], were used under solvent-free conditions. As for the microwave (MW)-assisted additions, only two cases were reported, but the catalytic variations were carried out in kitchen MW ovens [32,42], and thus, do lack of exact temperatures, these results cannot be reproduced. From a ’green chemical’ point of view, the solvent-free and catalyst-free additions are of interest, however, in these reactions, relatively long reaction times (1.5–10 h), and/or unreasonably large excesses (50–150 equiv) of the dialkyl phosphite were applied [43–52].

The synthesis of α-aryl-α-aminophosphine oxides by the addition of secondary phosphine oxides to imines is much less studied. Only a few publications were found and the reported reactions were performed in solvent (in DEE, THF or toluene) [53–56], or in the presence of a chiral catalyst [57]. There is only one solvent and catalyst-free example [58], but in this case a long reaction time (9 h) was required. In the Pudovik synthesis of α-aminophosphine oxides, the MW-assisted accomplishment has not been utilized at all. In the current paper, we wished to develop a facile catalyst and solvent-free MW-assisted method for the synthesis of α-aryl-α-aminophosphonates and α-aryl-α-aminophosphine oxides by the addition of dialkyl phosphites or diphenylphosphine oxide to the double bond of imines, and aimed at the preparation of new derivatives.

Results and Discussion

Synthesis of α-aryl-α-aminophosphonates and α-aminophosphine oxides

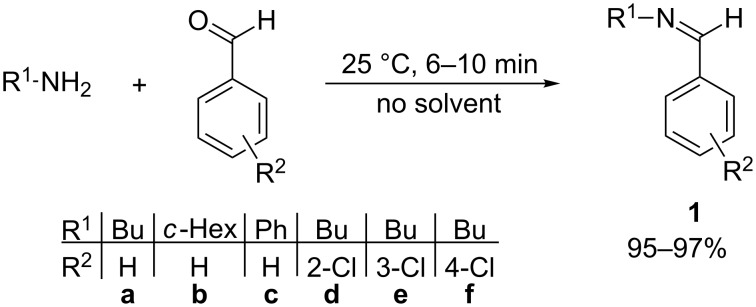

At first, the imine starting materials 1 were prepared by the condensation of benzaldehyde and its chloro-substituted derivatives with primary amines, such as butyl-, cyclohexylamine or aniline at room temperature under solvent-free conditions (Scheme 1).

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of starting N-benzylideneamines 1.

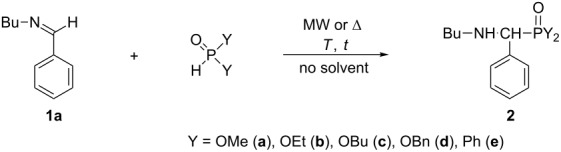

Then, the reaction of N-benzylidene(butyl)amine (1a) with four different dialkyl phosphites and diphenylphosphine oxide was investigated under MW-assisted solvent-free conditions searching for the optimum temperature and reaction time (Table 1). The products were α-aminophosphonates 2a–d and α-aminophosphine oxide 2e.

Table 1.

Addition of dialkyl phosphites and diphenylphosphine oxide to N-benzylidenebutylamine (1a).

| ||||||||

| Entry | Mode of heating | >P(O)H | >P(O)H (equiv) |

T (°C) |

t (min) |

Composition (%)a | Yieldb (%) |

|

| 1a | 2 | |||||||

| 1 | MW | DMP | 1 | 80 | 30 | 5 | 95 (2a) | 73 |

| 2 | Δ | DMP | 1 | 80 | 30 | 21 | 79 (2a) | – |

| 3 | MW | DMP | 1 | 100 | 30 | 4 | 90c (2a) | – |

| 4 | MW | DMP | 1.2 | 100 | 30 | 0 | 94c (2a) | – |

| 5 | MW | DEP | 1 | 80 | 60 | 24 | 76 (2b) | – |

| 6 | MW | DEP | 1 | 100 | 30 | 5 | 95 (2b) | – |

| 7 | MW | DEP | 1.2 | 100 | 30 | 0 | 100 (2b) | 85 |

| 8 | Δ | DEP | 1.2 | 100 | 30 | 17 | 83 (2b) | – |

| 9 | MW | DBuP | 1.2 | 100 | 30 | 1 | 99 (2c) | 90 |

| 10 | MW | DBnP | 1.2 | 100 | 30 | 0 | 100d (2d) | 69 |

| 11e | MW | DPPO | 1.2 | 100 | 10 | 0 | 100d (2e) | 89 |

aOn the basis of GC. bAfter column chromatography. cIn these experiments byproduct 3 was also formed in a proportion of 6% based on GC–MS:  dOn the basis of HPLC. eUnder N2 atmosphere.

dOn the basis of HPLC. eUnder N2 atmosphere.

The addition of 1 equivalent of dimethyl phosphite (DMP) to imine 1a at 80 °C was almost complete after 30 min, and dimethyl ((butylamino)(phenyl)methyl)phosphonate (2a) could be isolated in a yield of 73% (Table 1, entry 1). Under similar conditions, the comparative thermal experiment led to a lower conversion of 79% (Table 1, entry 2). A full conversion could be achieved by heating at 100 °C under MW for 30 min although 1.2 equivalent of DMP were required. The formation of 6% of the N-methylated by-product 3 {δp (CDCl3) 25.4, [M + H]+found = 286.1582, C14H25NO3P requires 286.1567} was inevitable (Table 1, entries 3 and 4). Similar N-methylations have been observed also in other cases [59–60]. At 80 °C, diethyl phosphite (DEP) was less reactive than DMP, as after an irradiation time of 1 h, the conversion was only 76% (Table 1, entry 5). At 100 °C/30 min, the reaction proceeded better (Table 1, entry 6), but a complete conversion was experienced only when using 1.2 equivalents of DEP (Table 1, entry 7). In the latter case, aminophosphonate 2b was obtained in a yield of 85%. The comparative thermal experiment led again to a significantly lower conversion (Table 1, entry 8). Changing for dibutyl phosphite (DBuP), and applying it in a 1.2-fold quantity at 100 °C for 30 min, the addition was practically quantitative, and aminophosphonate 2c was obtained in a yield of 90% (Table 1, entry 9). Under similar conditions, the reaction of dibenzyl phosphite (DBnP) was also clear-cut and afforded dibenzyl ((butylamino)(phenyl)methyl)phosphonate (2d) in 69% yield (Table 1, entry 10). Finally, diphenylphosphine oxide (DPPO) was added to imine 1a. After 10 min irradiation at 100 °C, complete conversion was observed and aminophosphine oxide 2e was obtained in a yield of 89% (Table 1, entry 11).

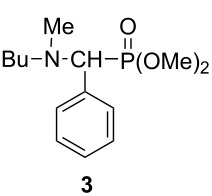

Next N-benzylidene(cyclohexyl)amine (1b) was tried in the aza-Pudovik reaction (Table 2).

Table 2.

Addition of >P(O)H reagents to N-benzylidene(cyclohexyl)amine (1b).

| ||||||||

| Entry | Mode of heating | >P(O)H | >P(O)H (equiv) |

T (°C) |

t (min) |

Composition (%)a | Yieldb (%) |

|

| 1b | 4 | |||||||

| 1 | MW | DMP | 1.2 | 80 | 30 | 11 | 89 (4a) | – |

| 2 | MW | DMP | 1.2 | 100 | 30 | 7 | 93c (4a) | – |

| 3 | MW | DMP | 1.5 | 100 | 30 | 1 | 99 (4a) | 87 |

| 4 | Δ | DMP | 1.5 | 100 | 30 | 9 | 91 (4a) | – |

| 5 | MW | DEP | 1.2 | 100 | 30 | 0 | 100 (4b) | 91 |

| 6 | MW | DBuP | 1.2 | 100 | 30 | 4 | 96c (4c) | 93 |

| 7 | MW | DBnP | 1.2 | 100 | 30 | 0 | 100d (4d) | 68 |

| 8e | MW | DPPO | 1.2 | 100 | 10 | 0 | 100d (4e) | 88 |

aOn the basis of GC. bAfter column chromatography. cThere was no change for further irradiation. dOn the basis of HPLC. eUnder N2 atmosphere.

Its reaction with 1.2 equivalents of DMP at 80 °C for 30 min led to aminophosphonate 4a at a conversion of 89% (Table 2, entry 1). Even at 100 °C, no quantitative conversion could be achieved (Table 2, entry 2). There was need for 1.5 equivalents of DMP to attain a conversion of 99%. In this case, dimethyl ((cyclohexylamino)(phenyl)methyl)phosphonate (4a) was isolated in a yield of 87% (Table 2, entry 3). The comparative thermal experiment led to a somewhat lower conversion (Table 2, entry 4). The addition of DEP and DBuP at 100 °C on the C=N moiety of imine 1b was quantitative or almost quantitative, respectively. The corresponding aminophosphonates 4b and 4c could be prepared in yields of approximately 92% (Table 2, entries 5 and 6). The reaction of N-benzylidene(cyclohexyl)amine (1b) with DBnP at 100 °C afforded the target compound 4d in a conversion of 100% that could be isolated in a yield of only 68% (Table 2, entry 7). The phosphinoylation of imine 1b was carried out at 100 °C for 10 min. The yield of ((cyclohexylamino)(phenyl)methyl)diphenylphosphine oxide (4e) was 88% (Table 2, entry 8). It can be noted that the reactivity of N-benzylidene(butyl)amine (1a) and N-benzylidene(cyclohexyl)amine (1b) is comparable.

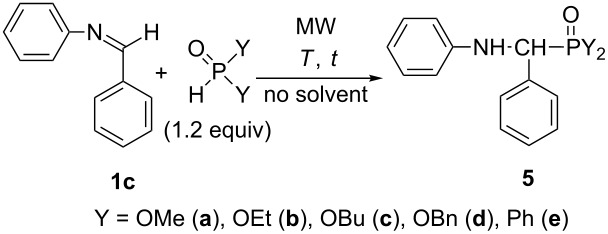

N-Benzylideneaniline (1c) revealed a somewhat enhanced reactivity in the reaction with the >P(O)H species (Table 3). The electron-donating butyl and cyclohexyl groups decrease the partial positive charge on the carbon atom of the >C=N- unit, as compared to the phenyl substituent. Hence, complete additions could be accomplished already at 80 °C within reaction times of 10–30 min. The yields of aminophosphonates 5a–c were in the range of 92–97%, while the benzyl ester (5d) was obtained in a yield of 70% (Table 3, entries 1–4). The aminophosphine oxide 5e was isolated in an 89% yield (Table 3, entry 5).

Table 3.

MW-assisted addition of >P(O)H reagents to N-benzylideneaniline (1c).

| ||||||

| Entry | >P(O)H |

T (°C) |

t (min) |

Composition (%)a | Yieldb (%) |

|

| 1c | 5 | |||||

| 1 | OMe | 80 | 10 | 1 | 99 (5a) | 92 |

| 2 | OEt | 80 | 10 | 0 | 100 (5b) | 93 |

| 3 | OBu | 80 | 20 | 0 | 100 (5c) | 97 |

| 4 | OBn | 80 | 30 | 0 | 100c (5d) | 70 |

| 5d | Ph | 80 | 10 | 0 | 100c (5e) | 89 |

aOn the basis of GC. bAfter column chromatography. cOn the basis of HPLC. dUnder N2 atmosphere.

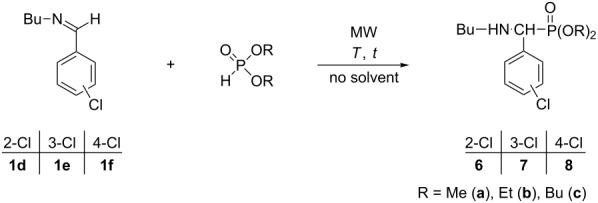

Next, N-chlorobenzylidene(butyl)amines 1d–f were reacted with dialkyl phosphites at 80–100 °C to obtain the corresponding α-aminophosphonates 6a–c, 7a–c and 8a–c. The results are collected in Table 4. The dialkyl ((butylamino)(chlorophenyl)methyl)phosphonates (6–8, a–c) were prepared in yields of 72–94% (Table 4, entries 1–9). There were no observable differences in the reactivities, as compared to the unsubstituted model compound 1a.

Table 4.

MW-assisted addition of dialkyl phosphites to N-chlorobenzylidene(butyl)amines 1d–f.

| ||||||||

| Entry | Imine | >P(O)H | >P(O)H (equiv) |

T (°C) |

t (min) |

Composition (%)a | Yieldb (%) |

|

| 1 | Product | |||||||

| 1 | 1d | DMP | 1 | 80 | 30 | 1 | 99 (6a) | 91 |

| 2 | 1d | DEP | 1.2 | 100 | 20 | 0 | 100(6b) | 72 |

| 3 | 1d | DBuP | 1.2 | 100 | 30 | 0 | 100 (6c) | 74 |

| 4 | 1e | DMP | 1 | 80 | 30 | 12 | 88 (7a) | 80 |

| 5 | 1e | DEP | 1.2 | 100 | 20 | 3 | 97 (7b) | 94 |

| 6 | 1e | DBuP | 1.2 | 100 | 30 | 7 | 93 (7c) | 73 |

| 7 | 1f | DMP | 1 | 80 | 30 | 12 | 88 (8a) | 75 |

| 8 | 1f | DEP | 1.2 | 100 | 20 | 0 | 100 (8b) | 80 |

| 9 | 1f | DBuP | 1.2 | 100 | 30 | 2 | 98 (8c) | 81 |

aOn the basis of GC. bAfter column chromatography.

All together 24 compounds including 21 α-aryl-α-aminophosphonates and three α-aryl-α-aminophosphine oxides were obtained by column chromatography and characterized. Among the aminophosphonates, 16 are new, and five are known in the literature, two out of the three aminophosphine oxides are new compounds.

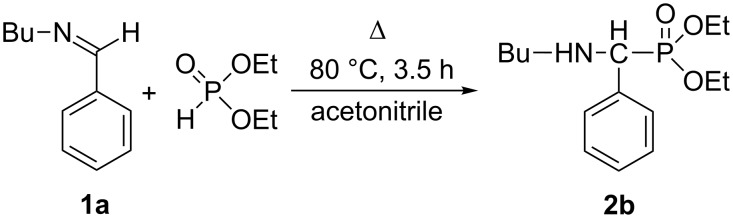

Study on the addition of diethyl phosphite to N-benzylidene(butyl)amine by in situ FTIR spectroscopy

Then, we wished to follow the addition reaction of DEP to N-benzylidene(butyl)amine (1a) at 80 °C in acetonitrile (Scheme 2) by in situ Fourier transform IR spectroscopy. Initially the IR spectra of the reaction components were recorded: imine 1a, DEP and diethyl ((butylamino)(phenyl)methyl)phosphonate (2b) (Table 5 and Figure 1). The spectrum of imine 1a has a strong absorption band at 1648 cm−1 corresponding to νC=N. At the same time, DEP may be identified by the strong signals at 961, 1042 and 1251 cm−1 assigned to the νP–O–C and the νP=O vibrations, respectively. The similar νP–O–C and νP=O absorptions of the product α-aminophosphonate 2b were somewhat shifted to 1026, 1057 and 1242 cm−1, respectively.

Scheme 2.

Addition of diethyl phosphite to N-benzylidene(butyl)amine in acetonitrile.

Table 5.

Characteristic IR absorptions of the reaction components.

| C6H5CH=NBu (1a) | (EtO)2P(O)H | (EtO)2P(O)CH(Ph)NHBu (2b) | |||

| 976 cm−1 | νC=N | 961 cm−1 | νP–O–C | 1026 cm−1 | νP–O–C |

| 1648 cm−1 | νC=N | 1042 cm−1 | νP–O–C | 1057 cm−1 | νP–O–C |

| 1251 cm−1 | νP=O | 1242 cm−1 | νP=O | ||

Figure 1.

IR spectra of the reaction components in acetonitrile solution.

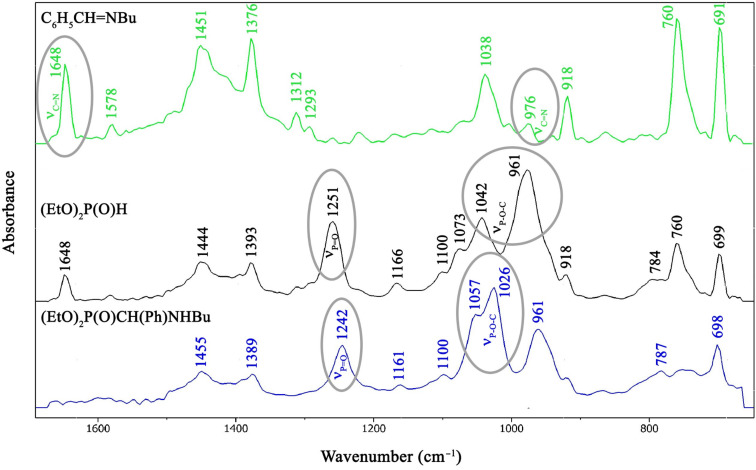

A segment of the time-dependent IR spectrum (3D diagram) can be seen in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

A segment of the time-dependent IR spectrum for the addition of diethyl phosphite to N-benzylidene(butyl)amine (1a) in acetonitrile under formation of diethyl ((butylamino)(phenyl)methyl)phosphonate (2b).

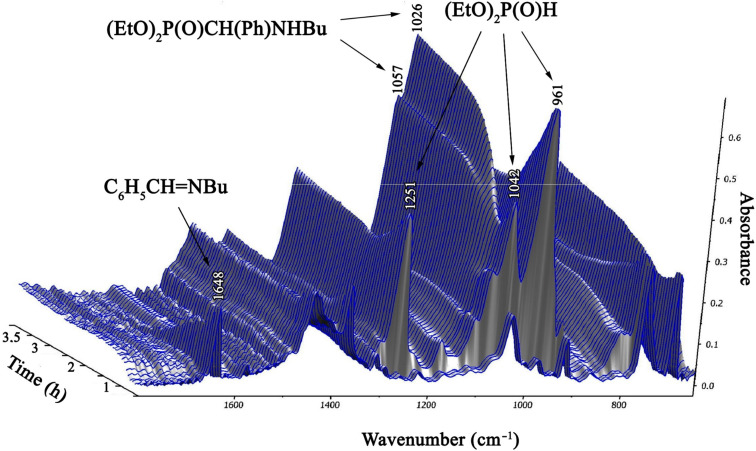

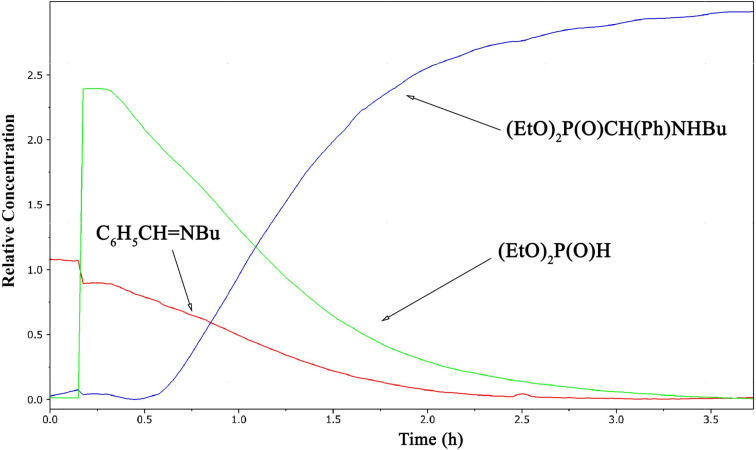

The obtained results from this study are shown in Figure 3 and show the concentration profile of the starting components imine 1a and DEP and the product 2b. The diagram was constructed by a so-called deconvolution on the basis of the decrease/increase of the different absorptions on the reaction time scale. This calculation (MCR-ALS, multivariate curve resolution – alternating least squares) gives the concentration profiles of the components and also the spectra of pure components. From Figure 3, it can be seen that the addition reaction was complete after 3.5 h.

Figure 3.

Concentration profiles of the reaction components in the addition reaction at 80 °C in acetonitrile.

Finally, the characteristic IR absorptions were taken from the calculated IR spectra and compared with those obtained in acetonitrile solutions (Table 6). As can be seen, the agreement is rather good.

Table 6.

IR absorptions measured and obtained from the 3D diagram after deconvolution (in cm−1).

| C6H5CH=NBu (1a) | (EtO)2P(O)H | (EtO)2P(O)CH(Ph)NHBu (2b) | |||

| Measured | Obtained | Measured | Obtained | Measured | Obtained |

| 1648 | 1648 | 1251 | 1262 | 1242 | 1246 |

| 976 | 976 | 1073 | 1073 | 1057 | 1053 |

| 1042 | 1046 | 1026 | 1026 | ||

| 961 | 980 | 961 | 961 | ||

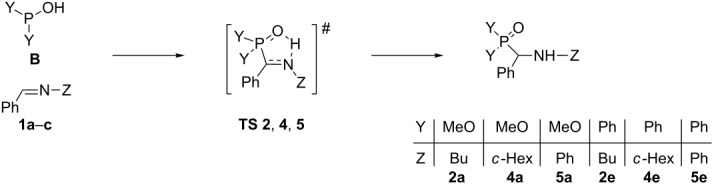

An X-ray crystallographic study on the α-aminophosphonates 5b and 5d

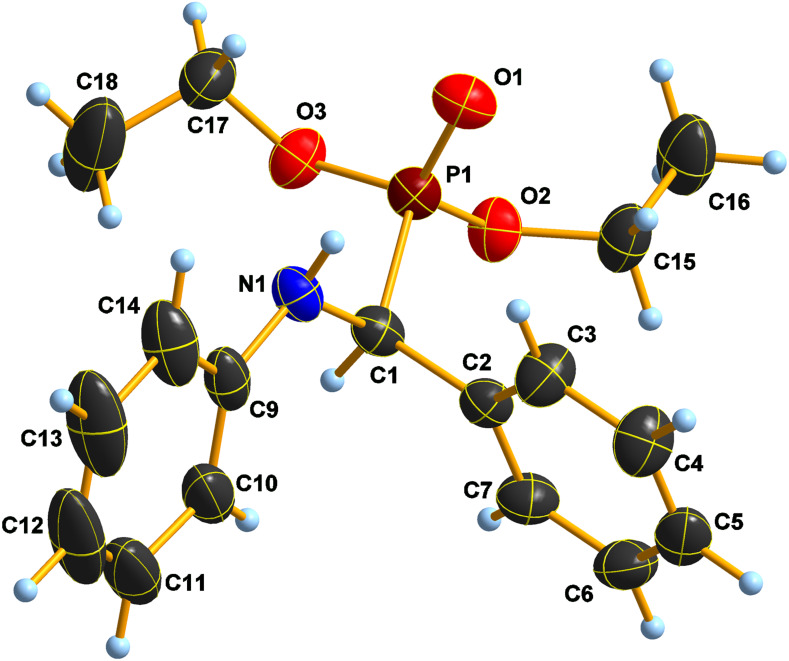

Large crystals of 5b are composed of very thin plates and one of these plates was dissected and used for X-ray measurement at low temperatures. There seems to be a slight disorder, which becomes evident in the ellipsoids of the aniline ring and one of the methyl carbon atoms (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Atomic numbering with anisotropic displacements plot of 5b at −100 °C.

The crystal structure of compound 5b was published almost 40 years ago [61], and a subsequent NMR and theoretical study was also done for comparative purposes [62]. This latter work claims SS and RR dimers, which is obviously wrong, as the centrosymmetric dimers formed must be RS due to symmetry. The crystal structure of 5b does not undergo a phase transition at −100 ºC, hence, it must be similar to the sample studied in the earlier work at room temperature [62]. Apart from the formation of the centrosymmetric dimer through a strong N–H···O=P hydrogen bridge (cf. Table 7), there is a C–H…O short contact to an ester oxygen atom of a next, translated and inverted 5b molecule, as well. In this way, sheets of symmetry center related dimers fused into endless sheets are formed in the crystal (cf. Supporting Information File 1, Figure S1).

Table 7.

Hydrogen bond dimensions (Å, Deg) for compounds 5b and 5d.a

| 5b | ||||

| D–H···A | D–H (Å) | H···A (Å) | D···A (Å) | D–H···A (°) |

| N1–H1A···O1b | 0.88(4) | 2.09(4) | 2.957(3) | 167(4) |

| C7–H7···O3c | 0.94(3) | 2.48(3) | 3.367(3) | 159(1) |

| 5d | ||||

| N1–H1A···O1d | 0.87(2) | 2.20(2) | 3.051(2) | 166(2) |

aD, donor; A, acceptor; bsymmetry related operator = 1−x,−y,−z; csymmetry related operator = 1−x, 1−y,−z; dsymmetry related operator = 1−x,−y,2−z.

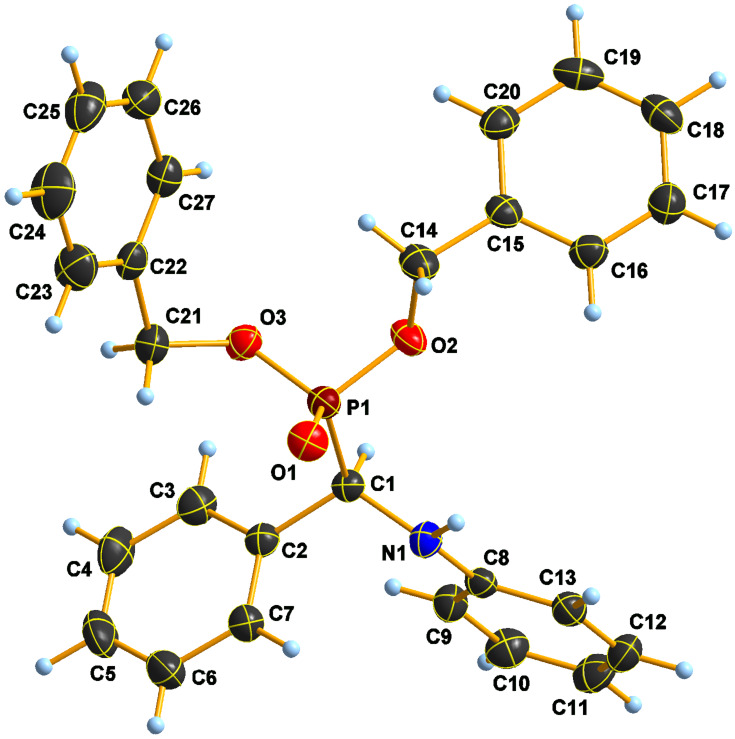

In the crystal structure of 5d (Figure 5), the formation of hydrogen-bonded dimers occurs through the same N–H···O=P hydrogen bonds in the solid state (Table 7 and Supporting Information File 1, Figure S2), too.

Figure 5.

Atomic numbering with anisotropic displacements plot of 5d at −100 °C.

A short intramolecular H(1)···H(10) distance in 5b appears to be nearly by −0.3 Å shorter than the sum of vdW radii (2.11(2) << 2.40), and is somewhat similar to those observed in other aminophosphonates [63]. No such short distance is seen in compound 5d, where all H···H contacts appear around or longer than the respective sums of van der Waals radii, and the only short attractive contact is in the H-bridge promoted dimer.

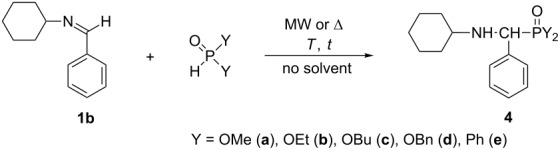

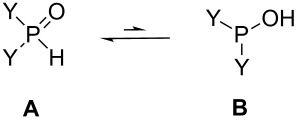

Theoretical study on the addition of the >P(O)H species to N-benzylideneamines

The calculations were carried out by the B3LYP/6-31G (d,p) method. In the solvent-free reaction, the dielectric constant of the P reagent was estimated as 78.3553. This value was taken into account as an implicit solvent effect. First, the tautomeric equilibria of dialkyl phosphites and diphenylphosphine oxide were studied (Table 8). It was not surprising to find that the pentavalent tetracoordinated form A was by 25–28 kJ mol−1 more stable than the trivalent form B.

Table 8.

Relative enthalpies, free energies and entropies for the tautomeric forms in case of methoxy and phenyl substituents.

| |||||||

| Y = MeO | ΔH [kJ mol−1] |

ΔG [kJ mol−1] |

ΔS [J (mol K)−1] |

Y = Ph | ΔH [kJ mol−1] |

ΔG [kJ mol−1] |

ΔS [J (mol K)−1] |

| A | 0 | 0 | 0 | A | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| B | 27.7 | 26.4 | 1.1 | B | 24.7 | 22.3 | 1.9 |

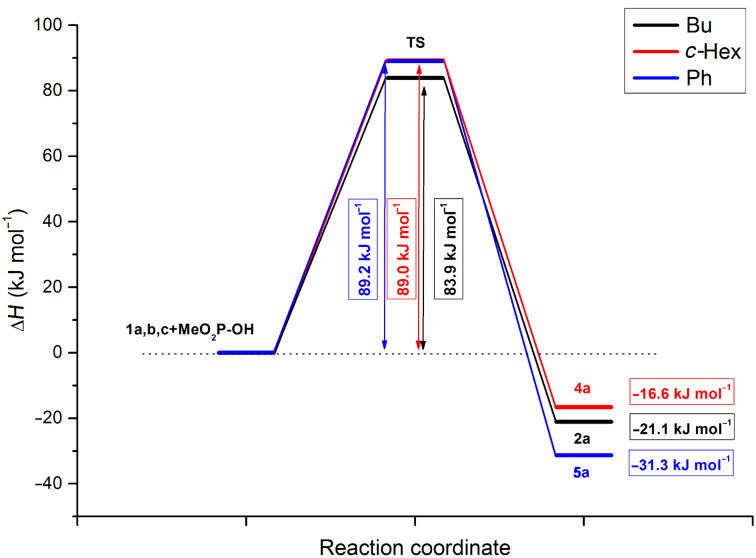

The calculations predicted the attack of the trivalent form B of the P reagent on the nitrogen atom of the C=N unit of the imine 1. Moreover, the P–C and the N–H bonds are formed in a single concerted step, via five-membered transition states TS 2, 4, and 5 (Table 9) and the additions are in all cases exothermic. The reactions with dimethyl phosphite are more favorable than those with diphenylphosphine oxide. It can also be seen that the additions to N-benzylideneaniline have the greatest driving force of ca. 31 kJ mol−1. The energy content of the TSs fall in the range of 77–89 kJ mol−1.

Table 9.

Relative enthalpies, free energies and entropies for the addition reaction of >P(O)H species to imines.

| |||||||

| Y = MeO | ΔH0/ΔH# [kJ mol−1] |

ΔG0/ΔG# [kJ mol−1] |

ΔS0/ΔS# [J (mol K)−1] |

Y = Ph | ΔH0/ΔH# [kJ mol−1] |

ΔG0/ΔG# [kJ mol−1] |

ΔS0/ΔS# [J (mol K)−1] |

| Z = Bu | Z = Bu | ||||||

| B + 1a → 2a | −21.1 | −4.7 | −13.1 | B + 1a → 2e | −10.9 | 3.5 | −11.5 |

| TS 2a | 83.9 | 100.5 | −13.3 | TS 2e | 80.8 | 92.4 | −9.3 |

| Z = c-hex | Z = c-hex | ||||||

| B + 1b → 4a | −16.6 | −5.6 | −8.8 | B + 1b → 4e | −7.6 | 8.3 | −12.8 |

| TS 4a | 89.2 | 96.7 | −6.0 | TS 4e | 85.3 | 100.8 | −12.4 |

| Z = Ph | Z = Ph | ||||||

| B + 1c → 5a | −31.3 | −17.4 | −11.2 | B + 1c → 5e | −30.9 | −15.3 | −12.5 |

| TS 5a | 89.0 | 98.8 | −7.9 | TS 5e | 77.4 | 90.9 | −10.8 |

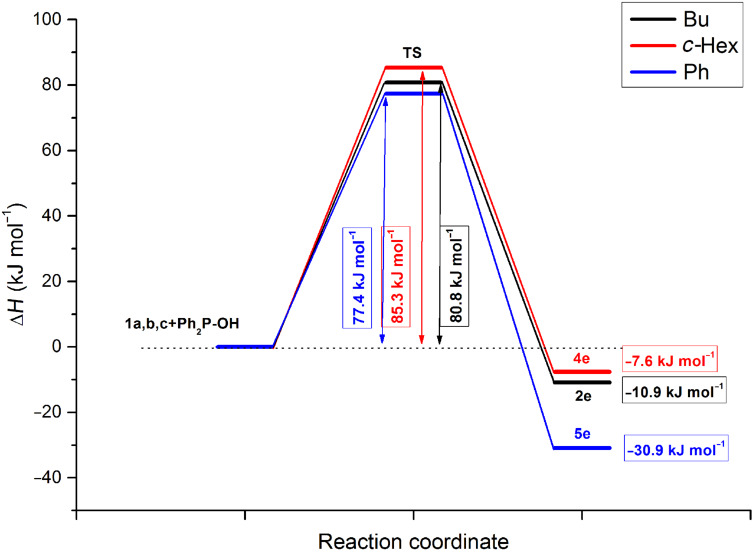

The energy diagrams for the reactions with dimethyl phosphite and diphenylphosphine oxide are shown in Figure 6 and Figure 7, respectively.

Figure 6.

The energy diagram for the reaction with dimethyl phosphite.

Figure 7.

The energy diagram for the reaction with diphenylphosphine oxide.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we have developed an efficient, solvent-free and catalyst-free MW-assisted method for the Pudovik synthesis of α-aryl-α-aminophosphonates and α-aryl-α-aminophosphine oxides. This method is a novel approach for the preparation of the target compounds, and was optimized for each case. Twenty-four derivatives were isolated and characterized. Except six compounds, these were new compounds. Furthermore, the reactivity was mapped, and the mechanism was evaluated by B3LYP/6-31G (d,p) calculations. The crystal structure of two α-aminophosphonates was studied by X-ray analysis suggesting centrosymmetric dimers.

Supporting Information

Experimental, X-ray crystallographic data, and NMR spectra.

Acknowledgments

The above project was supported by the Hungarian Scientific Research Fund (PD111895) and the Hungarian Research Development and Innovation Fund (K119202).

Contributor Information

Erika Bálint, Email: ebalint@mail.bme.hu.

György Keglevich, Email: gkeglevich@mail.bme.hu.

References

- 1.Kukhar V P, Hudson H R. Aminophosphonic and aminophosphinic acids: Chemistry and biological activity. Chichester: Wiley; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mucha A, Kafarski P, Berlicki Ł. J Med Chem. 2011;54:5955–5980. doi: 10.1021/jm200587f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sienczyk M, Oleksyszyn J. Curr Med Chem. 2009;16:1673–1687. doi: 10.2174/092986709788186246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Forlani G, Berlicki Ł, Duò M, Dziędzioła G, Giberti S, Bertazzini M, Kafarski P. J Agric Food Chem. 2013;61:6792–6798. doi: 10.1021/jf401234s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen M-H, Chen Z, Song B-A, Bhadury P S, Yang S, Cai X-J, Hu D-Y, Xue W, Zeng S. J Agric Food Chem. 2009;57:1383–1388. doi: 10.1021/jf803215t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kabachnik M I, Medved T Y. Dokl Akad Nauk SSSR. 1952;83:689–692. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fields E K. J Am Chem Soc. 1952;74:1528–1531. doi: 10.1021/ja01126a054. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cherkasov R A, Galkin V I. Russ Chem Rev. 1998;67:857–882. doi: 10.1070/RC1998v067n10ABEH000421. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Keglevich G, Bálint E. Molecules. 2012;17:12821–12835. doi: 10.3390/molecules171112821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nazish M, Saravanan S, Khan N-u H, Kumari P, Kureshy R I, Abdi S H R, Bajaj H C. ChemPlusChem. 2014;79:1753–1760. doi: 10.1002/cplu.201402191. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pudovik A N. Dokl Akad Nauk SSSR. 1950;73:499–502. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pudovik A N. Dokl Akad Nauk SSSR. 1952;83:865–868. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ali T E, Abdel-Kariem S M. ARKIVOC. 2015:246–287. doi: 10.3998/ark.5550190.p009.112. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Abdel-Rahman R M, Ali T E, Abdel-Kariem S M. ARKIVOC. 2016:183–211. doi: 10.3998/ark.5550190.p009.519. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Matveeva E D, Zefirov N S. Dokl Chem. 2008;420:137–140. doi: 10.1134/S0012500808060037. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lewkowski J, Tokarz P, Lis T, Ślepokura K. Tetrahedron. 2014;70:810–816. doi: 10.1016/j.tet.2013.12.042. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Motevalli S, Iranpoor N, Etemadi-Davan E, Moghadam K R. RSC Adv. 2015;5:100070–100076. doi: 10.1039/c5ra14393d. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reddy G C S, Annar S, Rao K U M, Balakrishna A, Reddy C S. Pharma Chem. 2010;2(1):177–184. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dadapeer E, Reddy S S, Rao V K, Raju C N. Orient J Chem. 2008;24:513–520. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kaboudin B, Jafari E. Synlett. 2008:1837–1840. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1078509. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marchand P, Griffe L, Poupot M, Turrin C-O, Bacquet G, Fournié J-J, Majoral J-P, Poupot R, Caminade A-M. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2009;19:3963–3966. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2009.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kabachnik M M, Ternovskaya T N, Zobnina E V, Beletskaya I P. Russ J Org Chem. 2002;38:480–483. doi: 10.1023/A:1016578602100. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ha H-J, Nam G-S. Synth Commun. 1992;22:1143–1148. doi: 10.1080/00397919208021098. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maier L, Diel P J. Phosphorus, Sulfur Silicon Relat Elem. 1991;57:57–64. doi: 10.1080/10426509108038831. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kabachnik M M, Ternovskaya T N, Zobnina E V, Beletskaya I P. Russ J Org Chem. 2002;38:484–486. doi: 10.1023/A:1016530718938. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nazish M, Jakhar A, Khan N-u H, Verma S, Kureshy R I, Abdi S H R, Bajaj H C. Appl Catal, A. 2016;515:116–125. doi: 10.1016/j.apcata.2015.12.037. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Joly G D, Jacobsen E N. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:4102–4103. doi: 10.1021/ja0494398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Akiyama T, Morita H, Itoh J, Fuchibe K. Org Lett. 2005;7:2583–2585. doi: 10.1021/ol050695e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pettersen D, Marcolini M, Bernardi L, Fini F, Herrera R P, Sgarzani V, Ricci A. J Org Chem. 2006;71:6269–6272. doi: 10.1021/jo060708h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Saito B, Egami H, Katsuki T. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:1978–1986. doi: 10.1021/ja0651005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Akiyama T, Morita H, Bachu P, Mori K, Yamanaka M, Hirata T. Tetrahedron. 2009;65:4950–4956. doi: 10.1016/j.tet.2009.03.023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Beletskaya I P, Patrikeeva L S, Lamaty F. Russ Chem Bull. 2011;60:2370–2374. doi: 10.1007/s11172-011-0364-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang Q, Zhu M, Zhu R, Lu L, Yuan C, Xing S, Fu X, Mei Y, Hang Q. Eur J Med Chem. 2012;49:354–364. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2012.01.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Naidu K R, Reddy K R K K, Kumar C V, Raju C N, Sharma D D. S Afr J Chem. 2009;62:185–188. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sobanov A A, Zolotukhin A V, Galkin V I, Cherkasov R A, Pudovik A N. Russ J Gen Chem. 2002;72:1067–1070. doi: 10.1023/A:1020794530963. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kraicheva I, Tsacheva I, Vodenicharova E, Tashev E, Tosheva T, Kril A, Topashka-Ancheva M, Iliev I, Gerasimova T, Troev K. Bioorg Med Chem. 2012;20:117–124. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2011.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Górniak M G, Kafarski P. Phosphorus, Sulfur Silicon Relat Elem. 2016;191:511–519. doi: 10.1080/10426507.2015.1094658. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhu S, Xu B, Zhang J, Qin C, Huang Q, Qu C. Phosphorus, Sulfur Silicon Relat Elem. 1996;112:219–224. doi: 10.1080/10426509608046365. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hong Y-P, Shangguan X-C, Iqbal Z, Yin X-L. Chin J Struct Chem. 2014;33:1673–1682. doi: 10.14102/j.cnki.0254-5861.2011-0367. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Failla S, Finocchiaro P, Hägele G, Kalchenko V I. Phosphorus, Sulfur Silicon Relat Elem. 1997;128:63–77. doi: 10.1080/10426509708031564. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.de Noronha R G, Romão C C, Fernandes A C. Catal Commun. 2011;12:337–340. doi: 10.1016/j.catcom.2010.10.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kabachnik M M, Zobnina E V, Beletskaya I P. Russ J Org Chem. 2005;41:505–507. doi: 10.1007/s11178-005-0194-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chen R-Y, Mao L-J. Phosphorus, Sulfur Silicon Relat Elem. 1994;89:97–104. doi: 10.1080/10426509408020438. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jagodić V. Eur J Inorg Chem. 1960;93:2308–2313. doi: 10.1002/cber.19600931020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gancarz R, Gancarz I, Walkowiak U. Phosphorus, Sulfur Silicon Relat Elem. 1995;104:45–52. doi: 10.1080/10426509508042576. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gruss U, Hägele G. Phosphorus, Sulfur Silicon Relat Elem. 1994;97:209–221. doi: 10.1080/10426509408020744. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Arsanious M H N. Heterocycl Commun. 2001;7:341–348. doi: 10.1515/HC.2001.7.4.341. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Alexander B H, Hafner L S, Garrison M V, Brown J E. J Org Chem. 1963;28:3499–3501. doi: 10.1021/jo01047a055. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Liu X-H, Weng J-Q, Tan C-X, Pan L, Wang B-L, Li Z-M. Asian J Chem. 2011;23:4031–4036. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hudson H R, Lee R J, Matthews R W. Phosphorus, Sulfur Silicon Relat Elem. 2004;179:1691–1709. doi: 10.1080/10426500490466274. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ćurić M, Tušek-Božić L, Vikić-Topić D. Magn Reson Chem. 1995;33:27–33. doi: 10.1002/mrc.1260330107. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Harger M J P, Williams A. J Chem Soc, Perkin Trans 1. 1989:563–569. doi: 10.1039/P19890000563. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Galkina I, Galkin V, Cherkasov R. Russ J Gen Chem. 1998;68:1402–1407. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gaumont A-C, Simon A, Denis J-M. Tetrahedron. 1998;39:985–988. doi: 10.1016/S0040-4039(97)10755-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hoarau C, Couture A, Deniau E, Grandclaudon P. Eur J Org Chem. 2001:2559–2567. doi: 10.1002/1099-0690(200107)2001:13<2559::AID-EJOC2559>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rohovec J, Vojtíšek P, Lukeš I. Phosphorus, Sulfur Silicon Relat Elem. 1999;148:79–95. doi: 10.1080/10426509908037002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ingle G K, Liang Y, Mormino M G, Li G, Fronczek F R, Antilla J C. Org Lett. 2011;13:2054–2057. doi: 10.1021/ol200456y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zhou Z-Y, Zhang H, Yao L, Wen J-H, Nie S-Z, Zhao C-Q. Chirality. 2016;28:132–135. doi: 10.1002/chir.22549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tajti Á, Bálint E, Keglevich G. Curr Org Synth. 2016;13:638–645. doi: 10.2174/1570179413666151218202757. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bálint E, Tóth R E, Keglevich G. Heteroat Chem. 2016;27:323–335. doi: 10.1002/hc.21343. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ruzic-Toros Z, Kojic-Prodic B, Sljukic M. Acta Crystallogr, Sect B: Struct Crystallogr Cryst Chem. 1978;34:3110–3113. doi: 10.1107/S0567740878010225. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Dronia H, Failla S, Finocchiaro P, Gruss U, Hägele G. Phosphorus, Sulfur Silicon Relat Elem. 1995;101:149–160. doi: 10.1080/10426509508042511. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hudson H R, Czugler M, Lee R J, Woodroffe T M. Phosphorus, Sulfur Silicon Relat Elem. 2016;191:469–477. doi: 10.1080/10426507.2015.1091833. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Experimental, X-ray crystallographic data, and NMR spectra.