Abstract

Emotional and behavioral regulation has been linked to coping and enhancement motives and associated with different patterns of alcohol use and problems. The current studies examined emotional instability, urgency, and internal drinking motives as predictors of alcohol dependence symptoms and DSM-5 Alcohol Use Disorder. In Study 1, college drinkers (n = 621) completed alcohol involvement and behavioral/emotional functioning assessments. There was an indirect association between emotional instability and dependence symptoms via both coping and enhancement drinking motives which was potentiated by trait urgency. In Study 2, college drinkers (n = 510) completed alcohol involvement, behavioral/emotional functioning, and AUD criteria assessments. A significant indirect effect from emotional instability to the likelihood of meeting AUD criteria, via drinking to cope was found, again potentiated by urgency.

Introduction

In the college environment, alcohol misuse is common and frequently results in negative consequences ranging from minor social and academic problems to severe injury and death (Hingson, Zha, & Weitzman, 2009; Wechsler, Lee, Kuo, & Lee, 2000). It has been estimated that alcohol misuse among college students results in 1,800 deaths and 696,000 injuries annually (Hingson et al., 2009). Approximately 80% of college students drink (Johnston, O’Malley, Bachman, & Schulenberg, 2012) and about 1 in 5 (18.7%) meet DSM-IV-TR diagnostic criteria for an alcohol use disorder (Dawson, Grant, Stinson, & Chou, 2004). Identifying global antecedents that predispose these individuals to pathological alcohol use is an important area of research. The current studies examine emotional instability, urgency, and internal drinking motives as predictors of alcohol dependence symptoms (Study 1) and likely DSM-5 Alcohol Use Disorder (AUD) diagnosis and severity (Study 2).

Motivational Models of Alcohol Use

Motivational models of alcohol use posit that drinking motives are the most proximal antecedents to alcohol use (Cooper, 1994; Cox & Klinger, 1988; Dvorak, Pearson, & Day, 2014; Kuntsche, Knibbe, Gmel, & Engels, 2005). Enhancement motives are generally associated with drinking to enhance one’s mood, whereas coping motives are associated with drinking to ameliorate one’s negative mood (Cooper, 1994; Dvorak et al., 2014; Kuntsche et al., 2005). The present study focuses on these two internal motives (coping and enhancement), as they are directly tied to emotional instability and urgency (Gonzalez, Reynolds, & Skewes, 2011; Simons, Gaher, Correia, Hansen, & Christopher, 2005) and have been implicated as precursors to pathological alcohol use (Merrill, Wardell, & Read, 2014; Tragesser, Sher, Trull, & Park, 2007).

Research suggests that different drinking motives are associated with different patterns of alcohol use, and therefore are differentially related to alcohol-related problems (Cooper, 1994; Kuntsche et al., 2005; Merrill & Read, 2010; Merrill et al., 2014). Overall, enhancement motives seem most strongly related to increased alcohol use, which in turn predicts alcohol-related problems, whereas coping motives seem to be directly related to alcohol-related problems (Cooper, 1994; Kuntsche et al., 2005). However, research has shown considerable overlap in alcohol use motives (Cooper, Frone, Russell, & Mudar, 1995; Kuntsche, Stewart, & Cooper, 2008), and often it is impossible to classify individuals into mutually exclusive groups based on their self-reported reasons for drinking (Beseler, Aharonovich, Keyes, & Hasin, 2008; Littlefield, Vergés, Rosinski, Steinley, & Sher, 2013). Thus, a variety of motives may be associated with the progression to pathological alcohol use. Consistent with this notion, previous research has linked both enhancement and coping motives to symptoms of alcohol dependence (Beseler et al., 2008; Merrill & Read, 2010). Furthermore, these links appear to mediate the relationship between a myriad of temperament/personality factors and alcohol dependence symptoms (Loukas, Krull, Chassin, & Carle, 2000; Tragesser et al., 2007).

Mood and Problematic Alcohol Use

Several theoretical models posit a relationship between mood-related variables and alcohol outcomes. A variety of theories have been proposed that link mood and alcohol use via positive and/or negative reinforcement (Baker, Piper, McCarthy, Majeskie, & Fiore, 2004; Conger, 1956; Khantzian, 1997). These models posit that individuals use alcohol to cope with negative affect, to increase positive affective states, or both. Support for these models range from cross-sectional correlational research demonstrating a relation between depression/anxiety/negative affect and alcohol misuse (Kalodner, Delucia, & Ursprung, 1989), longitudinal studies documenting prospective associations (Kaplow, Curran, Angold, & Costello, 2001), epidemiological studies that reveal the comorbidity of mood/anxiety disorders with alcohol use disorders (B. F. Grant et al., 2005), and experience sampling studies that show day-to-day relationships between affect and alcohol consumption (Dvorak et al., 2014; Dvorak & Simons, 2014; Simons, Dvorak, Batien, & Wray, 2010).

All of these models share the prediction that mood-related variables are positively associated with alcohol misuse; however, they are focused generally on tonic emotional states rather than emotional instability. Emotional instability can be operationalized as mood variability, or the frequency and intensity of fluctuations in mood. Previous research has linked emotional instability to problematic alcohol use in cross-sectional (Kuvaas, Dvorak, Pearson, Lamis, & Sargent, 2013; Simons, Carey, & Wills, 2009; Simons et al., 2005), prospective (Simons & Carey, 2006), and ecological momentary assessment studies (Ebner-Priemer, Eid, Kleindienst, Stabenow, & Trull, 2009; Jahng et al., 2011). In terms of the effects of emotional instability on alcohol-related outcomes, each positive or negative fluctuation in mood offers an opportunity to drink for both positive and negative reinforcement. Therefore, based on motivational accounts of alcohol use, both coping and enhancement motives may mediate the associations between emotional instability and problematic alcohol-related outcomes.

Impulsivity and Problematic Alcohol Use

Another important factor to consider in the development and maintenance of problematic alcohol use is impulsivity. Nearly every model of personality contains a trait resembling ‘impulsivity’ (Whiteside & Lynam, 2001). Research supports that impulsivity concurrently (Magid & Colder, 2007) and prospectively (Cyders & Smith, 2008b) predicts alcohol misuse. However, one problem with impulsivity research is that impulsivity is a very loose, heterogeneous construct (Dick et al., 2010). Recently, a five-factor model of impulsivity has been developed to reflect this heterogeneous nature (Cyders & Smith, 2008b; Miller, Flory, Lynam, & Leukefeld, 2003). Among these factors, one aspect of emotionally driven impulsivity (i.e., urgency) has been consistently linked to negative outcomes (Cyders & Smith, 2008b; Simons et al., 2010; Wray, Simons, Dvorak, & Gaher, 2012). Cyders and Smith (2007) propose that urgency is comprised of two separate sub-types: positive urgency (i.e., behaving impulsively when experiencing positive affect) and negative urgency (i.e., behaving impulsively when experiencing negative affect).

Magid and Colder (2007) found that negative urgency predicted experiencing more alcohol-related consequences. Further, Smith et al. (2007) demonstrated that negative urgency predicted increased frequency/quantity of alcohol use as well as alcohol-related problems. Fischer and Smith (2008) found that negative urgency predicted increased problem drinking but not alcohol use. Using the five-factor model of impulsivity-like traits, Cyders, Flory, Rainer, and Smith (2009) showed that positive urgency prospectively predicted an increase in quantity of alcohol consumption and alcohol-related problems over the first year of college. Moreover, Curcio and George (2011) examined three of the impulsivity-like traits (sensation-seeking, positive urgency, and negative urgency), and found that only negative urgency predicted alcohol-related problems when controlling for alcohol use. Despite the benefit of looking at each impulsivity-like trait separately, some of the inconsistencies in the literature may be due to high collinearity between the positive and negative subtypes. In a recent factor analysis, Wills, Simons, Forbes, McGurk, and Nagakura (2013) found that the two urgency constructs load on a single factor. This is consistent with the original factor structure presented by Cyders and Smith (2007). For this reason, some researchers have begun to combine positive and negative urgency into a single factor, simply called urgency (Derefinko, DeWall, Metze, Walsh, & Lynam, 2011; Dvorak & Day, 2014; Kuvaas et al., 2013).

Integrating Urgency, Emotional Instability, and Drinking Motives

Importantly, some research has shown that the predictive effects of impulsivity constructs on alcohol outcomes are mediated by internal drinking motives. For example, Adams, Kaiser, Lynam, Charnigo, and Milich (2012) found that the relationship between impulsivity and alcohol-related problems was mediated by both coping and enhancement motives. Other studies have shown that motives partially or fully mediate the association between impulsivity and alcohol related problems (Littlefield, Sher, & Wood, 2009; Magid, MacLean, & Colder, 2007). Two studies found a significant direct relation between impulsivity and alcohol related problems that was not mediated by drinking motives (Curcio & George, 2011; Simons et al., 2005). However, impulsivity did not predict alcohol use in either of these studies. Thus, there is conflicting evidence that the predictive effects of impulsivity constructs on alcohol-related outcomes are mediated by drinking motives. Understanding when impulsivity is mediated via drinking motives may uncover important aspects of pathological use.

Finally, there is research suggesting that impulsivity interacts with emotional instability to predict alcohol-related problems. For example, Simons, Carey, and Gaher (2004) found that impulsivity and emotional instability synergistically increased the risk for alcohol-related problems. In a separate study, Simons et al. (2009) found emotional instability exhibited a direct effect on alcohol dependence symptoms; whereas, impulsivity (though, again, not specifically urgency) had a direct effect on alcohol abuse symptoms. Emotional instability and impulsivity only interacted to predict alcohol abuse symptoms. Stevenson and colleagues (2015) recently found that emotional instability predicted alcohol dependence symptoms among heavy college student drinkers, and this effect was more robust among those with lower cognitive control. Thus, it is possible that some of the inconsistencies regarding motives are a function of the facet of impulsivity used and the failure to account for the possibility that associations between impulsivity (i.e., urgency) and drinking motivation may vary as a function of emotional instability. Furthermore, previous studies have demonstrated that the synergistic interaction of impulsivity and emotional instability is more important for earlier stage alcohol use pathology, but is perhaps less important once a pattern of pathological use is established (see Simons et al., 2009).

Purpose

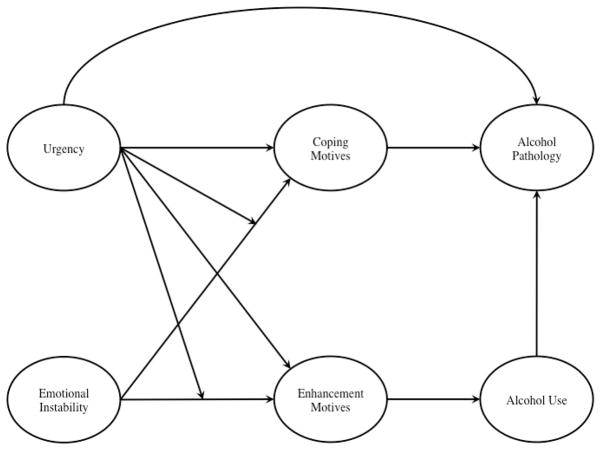

Research suggests that poor control over one’s emotions (i.e., emotional instability) and poor control of one’s behaviors in the face of intense emotions (i.e., urgency) predict problematic alcohol use via increased drinking motives. We conducted two studies testing hypotheses derived from an overarching theoretical model (see Figure 1). The present studies aim to examine the interaction of risk factors in the prediction of clinically relevant alcohol-related outcomes via drinking motives. Specifically, we anticipated that individuals with poor behavioral control and poor emotional control would have stronger internal drinking motivations, which in turn would be related to more pathological alcohol use. Further, we expected that the association between emotional instability and problematic alcohol-related outcomes would be higher among those with more urgency. Finally, we hypothesized that the synergistic association between urgency and emotional instability would be primarily important in the identification of pathological alcohol use.

Figure 1.

Theoretical model of alcohol pathology

Note. All hypothesized paths are positive in sign.

Study 1

Although many alcohol-related studies place frequency or quantity of alcohol use as the ultimate outcome of interest, we focused on symptoms of alcohol pathology, which is more directly associated with the degree of clinical impairment. In study 1, we examine alcohol dependence symptoms. Specifically, we modeled urgency and emotional instability as predictors of internal drinking motives (coping and enhancement), which in turn were hypothesized to predict alcohol use and alcohol dependence symptoms. We also examined the interactions between urgency and emotional instability in the prediction of drinking motives. We hypothesized that the main and interactive effects of urgency and emotional instability would be associated with alcohol use and alcohol dependence symptoms via drinking motives. The following hypotheses were proposed:

-

H1

The association between emotional instability and alcohol use would be mediated via enhancement drinking motives: instability→ enhancement motives→alcohol use.

-

H2

The association between emotional instability and dependence symptoms would be mediated via two distinct processes: (H2a) instability→enhancement motives→alcohol use→dependence symptoms and (H2b) instability→coping motives→dependence symptoms.

-

H3

The indirect effect in H1 from instability to alcohol use, via enhancement motives, would be potentiated by urgency. Specifically, the indirect effect between emotional instability and alcohol use would be potentiated when trait urgency was high.

-

H4

The path from emotional instability to alcohol dependence symptoms, via the two processes in H2 would be more robust among those with higher trait urgency. Specifically, urgency would potentiate the relationships between emotional instability and enhancement motives (H4a) and between emotional instability and coping motives (H4b) resulting in a more robust total indirect effect between emotional instability and dependence symptoms.

Methods

Participants

The current sample was drawn from a larger sample of college students (n = 860) who were recruited for a study examining “Emotion and Alcohol Use.” Individuals who reported that they never drank (n = 107) or drank once per month or less (n = 129) were removed prior to analysis. Three individuals who self-reported extremely high weekly drinking (see below) were also excluded prior to analysis. The analysis sample (n = 621; 56.91% female) ranged in age from 18–33 (M = 21.41, SD = 2.35). Participants were 90.68% Caucasian, 4.34% Asian, 1.61% African American, and 3.37% other or did not respond.

Measures

Emotional instability

Emotional instability was assessed via the Affect Lability Scale – Short Form (ALS-SF; Oliver & Simons, 2004). The ALS-SF is an 18-item self-report questionnaire. All items were measured on a 4-point response scale ranging from very undescriptive to very descriptive. The measure consists of three subscales (Anxiety/Depression: 5 items, α = .90; Depression/Elation: 8 items, α = .90; Anger: 5 items, α = .91). The ALS-SF has shown good internal consistency and validity with 30-day test-retest reliability ranging from r = .56 to .86 across subscales (Oliver & Simons, 2004). The three subscales were used to form the latent emotional instability variable.

Urgency

The UPPS-P (Cyders & Smith, 2007; Cyders et al., 2007; Whiteside & Lynam, 2001) is a self-report measure designed to assess five aspects of trait-like impulsivity. Two factors from the UPPS-P were used for the current study: negative urgency (12 items, α = .90) and positive urgency (14 items, α = .95). Research suggests these two aspects load on a common “urgency” trait (Cyders & Smith, 2007, 2008a; Wills et al., 2013). Items for positive and negative urgency were divided into two parcels for each construct and used to form the latent urgency variable. Negative urgency refers to the tendency to act rashly during times of negative emotion. Positive urgency refers to the tendency to act rashly during times of positive emotion (Cyders & Smith, 2008b). For both measures of urgency, participants responded to statements on a 4-point response scale ranging from strongly agree to strongly disagree.

Enhancement and Coping Motives

Drinking motives were assessed by the 20-item Drinking Motives Questionnaire (DMQ; Cooper, 1994). Each item was rated on a 5-point response scale (1 = almost never/never to 5 = almost always/always; sample item: “To forget your worries.”). The two motives included in the analysis were enhancement (5 items; α = .91) and coping (5 items; α = .90). Each indicator was used to form a latent drinking motivation variable. Previous research supports the convergent and discriminant validity of these motives with other drinking predictors (Kuntsche, von Fischer, & Gmel, 2008).

Alcohol Use

Alcohol use was assessed via the Modified Daily Drinking Questionnaire (DDQ-M; Dimeff, Baer, Kivlahan, & Marlatt, 1999) and the alcohol use subscale of the Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test (AUDIT; Saunders, Aasland, Babor, & de la Fuente, 1993). For the DDQ-M, individuals report the standard number of drinks they consume for each night of the week, as well as the amount of time spent drinking on each night. In addition, participants reported their weight in pounds. This information was used to compute average blood alcohol content (BAC) on drinking nights (Carey & Hustad, 2002). The alcohol use subscale of the AUDIT assesses typical alcohol use frequency (item 1) and quantity (item 2), and binge frequency (item 3). The three AUDIT items, the computed BAC variable, and the sum of weekly drinks reported in DDQ-M were used as indicators of the latent alcohol use variable.

Dependence Symptoms

Dependence symptoms were assessed via the dependence items (4–6) from the AUDIT (Saunders et al., 1993) and the Physical Dependence subscale of the Young Adult Alcohol Consequences Questionnaire (YAACQ; Read, Kahler, Strong, & Colder, 2006). These symptoms showed reasonable internal consistency (α = .73). These items served as indicators of a latent factor indexing dependence symptoms. Previous research supports the use of the AUDIT and YAACQ in college student samples (DeMartini & Carey, 2012; Dvorak, Lamis, & Malone, 2013; Read, Merrill, Kahler, & Strong, 2007).

Procedure

Participants, recruited via campus-wide email, completed an online survey assessing basic demographics, aspects of behavioral and emotional functioning, drinking motivation, and alcohol involvement/consequences. The university IRB approved this study and all participants were treated in accordance with APA ethical guidelines.

Planned analysis

In the current study, we tested the theoretical model, depicted in Figure 1, in the prediction of alcohol dependence symptoms among a sample of college students who endorsed typically drinking on at least two separate occasions per month. We first examined the univariate data. Three individuals reported unrealistically high alcohol consumption rates. These observations were excluded from the analysis. Next, we specified a measurement model to evaluate the latent constructs. During this phase, correlated errors among observed variables (but not structural model parameters) with modification indices >20 were allowed to covary. We then tested the theoretical model of alcohol dependence symptoms. All analyses were conducted in Mplus 7.11 (Muthén & Muthén, 2012) using full information maximum likelihood estimation with robust standard errors in the context of missing data. The inclusion of a latent variable interaction between urgency and emotional instability requires numerical integration, for which traditional fit indices are not available. Thus, we first estimated the model without the interaction to ensure adequate fit. Next, we added the interaction and used AIC/BIC to compare fit relative to the model without the latent interaction. Significant latent interactions were probed at +/− 1 SD on the latent urgency variable (Aiken & West, 1991).

Results

Descriptive and bivariate statistics

Descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations are listed in Tables 1 and 2, respectively. Men tended to be older, endorsed more alcohol use, and higher dependence symptoms. Urgency was positively correlated with coping and enhancement motives, alcohol use, and dependence symptoms, and inversely correlated with age. Emotional instability was positively correlated with both motives and with dependence symptoms, but not with alcohol use. Finally, alcohol use and dependence symptoms were positively correlated.

Table 1.

Descriptive data for Study 1 and Study 2

| Variables | Study 1 (n = 621) | Study 2 (n = 510) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Skew | Range | Mean | SD | Skew | Range | |

|

|

|

|

||||||

| Age | 21.41 | 2.35 | 1.00 | 18–33 | 20.31 | 2.29 | 2.03 | 18–34 |

| Gender | 0.43 | 0.50 | 0.28 | 0–1 | 0.45 | 0.50 | 0.21 | 0–1 |

| Emotional Instability | 33.76 | 12.71 | 0.79 | 18–72 | 34.49 | 11.82 | 0.69 | 18–72 |

| Positive Urgency | 26.85 | 9.96 | 0.89 | 14–56 | 25.71 | 8.30 | 0.67 | 14–56 |

| Negative Urgency | 26.60 | 7.68 | 0.36 | 12–47 | 26.15 | 6.99 | 0.24 | 12–46 |

| Coping Motives | 11.41 | 4.99 | 0.67 | 5–25 | 10.02 | 4.40 | 0.97 | 5–25 |

| Enhancement Motives | 14.64 | 0.98 | 4.90 | 5–25 | 13.67 | 4.94 | 0.06 | 5–25 |

| DDQ-M | 21.45 | 19.42 | 1.63 | 0–100 | 11.95 | 9.92 | 1.91 | 0–83 |

| Computed BAC | 0.05 | 0.07 | 2.77 | 0–0.55 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 1.97 | 0–0.53 |

| AUDIT – Use (1–3) | 5.71 | 2.26 | 0.34 | 2–12 | 5.83 | 2.23 | 0.28 | 2–11 |

| AUDIT – Consequences (4–10) | 3.77 | 4.06 | 1.55 | 0–24 | 3.61 | 3.88 | 1.86 | 0–23 |

| AUDIT – Total | 9.48 | 5.58 | 1.08 | 2–36 | 8.95 | 4.74 | 1.09 | 2–31 |

| YAACQ – PD scale | 0.44 | 0.75 | 2.01 | 0–4 | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| DSM-5 AUD DX | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | 0.49 | 0.50 | 0.03 | 0–1 |

| DSM-5 AUD Severity1 | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | 3.80 | 2.09 | 1.37 | 2–11 |

Note. Gender was dummy coded as 0 = female, 1 = male. DDQ-M = Modified Daily Drinking Questionnaire; BAC = Blood Alcohol Content; AUDIT = Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test; YAACQ – PD = Young Adult Alcohol Consequences Questionnaire – Physical Dependence Scale; AUD = Alcohol Use Disorder; DX = Diagnosis.

Number of items endorsed among those who met diagnostic criteria for an AUD (n = 251).

Table 2.

Bivariate correlations among Study 1 (n = 624) and Study 2 (n = 511) variables

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Sex | .10* | .01 | −.08 | −.04 | .06 | .27** | .13** | |

| 2. Age | −.01 | −.10* | −.07 | −.06 | −.15** | .00 | −.02 | |

| 3. Urgency | .16** | −.12** | .35** | .33** | .20** | .14** | .22** | |

| 4. Emotional Instability | −.01 | −.05 | .46** | .39** | .19** | .08 | .21** | |

| 5. Coping Motives | −.06 | −.11* | .48** | .39** | .49** | .20** | .38** | |

| 6. Enhancement Motives | .04 | −.22** | .30** | .19** | .55** | .47** | .34** | |

| 7. Alcohol Use | .25** | −.10* | .24** | .03 | .24** | .47** | .38** | |

| 8. Alcohol use pathology | .04 | −.02 | .34** | .20** | .40** | .39** | .41** |

Note. Study 1 is above the diagonal; Study 2 is below the diagonal. Gender was dummy-coded (0 = Women, 1 = Men). Study 1: Alcohol use pathology = alcohol dependence symptoms; Study 2: Alcohol use pathology = Alcohol Use Disorder Diagnosis (0 = no, 1 = yes).

p < .05

p < .01

Measurement model

We first specified a measurement model to assess overall structure of the latent constructs. The initial model showed adequate, though not ideal, fit to the data, χ2(df = 284, n = 621) = 1072.71, p < .001, Comparative Fit Index (CFI) = 0.89, Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) = 0.07, Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) = 0.07. Examination of modification indices suggested several correlated errors among observed variable indicators. Five correlations with modification indices >20 were sequentially allowed to covary and the model re-estimated, χ2(df = 279, n = 621) = 632.39, p < .001, CFI = 0.95, RMSEA = 0.05, SRMR = 0.06. This resulted in a significantly better fit to the data, Δχ2(df = 5, n = 621) = 467.76, p < .001. Table 3 lists the factor loadings of the latent constructs.

Table 3.

Latent construct factor loadings for Study 1 and Study 2

| Variables | Study 1 | Study 2 |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

| Positive Urgency 1 | 0.68 | 0.75 |

| Positive Urgency 2 | 0.76 | 0.71 |

| Negative Urgency 1 | 0.92 | 0.90 |

| Negative Urgency 2 | 0.84 | 0.82 |

| Anxiety/Depression | 0.89 | 0.86 |

| Depression/Elation | 0.83 | 0.78 |

| Anger | 0.76 | 0.77 |

| DMQ1 | 0.75 | 0.73 |

| DMQ4 | 0.80 | 0.80 |

| DMQ6 | 0.78 | 0.75 |

| DMQ15 | 0.52 | 0.58 |

| DMQ17 | 0.82 | 0.84 |

| DMQ7 | 0.87 | 0.79 |

| DMQ9 | 0.74 | 0.79 |

| DMQ10 | 0.50 | 0.59 |

| DMQ13 | 0.83 | 0.79 |

| DMQ18 | 0.76 | 0.80 |

| DDQ-M | 0.33 | 0.83 |

| AUDIT1 | 0.52 | 0.54 |

| AUDIT2 | 0.80 | 0.81 |

| AUDIT3 | 0.82 | 0.84 |

| BAC | 0.61 | 0.63 |

| YAACQ – PD | 0.65 | ------ |

| AUDIT4 | 0.68 | ------ |

| AUDIT5 | 0.71 | ------ |

| AUDIT6 | 0.47 | ------ |

Note. DMQ = Drinking Motives Questionnaire. DDQ-M = Modified Daily Drinking Questionnaire. AUDIT1–6 = specific Items from the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test. YAACQ-PD Scale = Young Adult Alcohol Consequences Questionnaire – Physical Dependence Scale.

Structural model

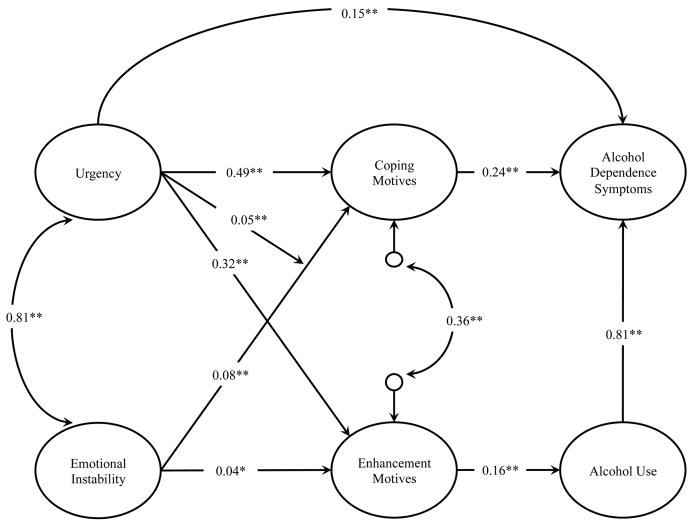

Next, we specified a structural equation model to test our hypotheses. We first specified the hypothesized model, without the latent interaction. This model showed reasonable fit to the data, χ2(df = 284, n = 621) = 637.22, p < .001, CFI = 0.95, RMSEA = 0.05, SRMR = 0.06, Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) = 42432.42, Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) = 42844.53, sample size adjusted Bayesian Information Criterion (SSBIC) = 42549.27. We next added the latent interaction. This required numerical integration, and hence traditional fit indices are not provided. In this model, urgency did not moderate the association between emotional instability and enhancement motives, thus, this path was dropped and the model was re-estimated, AIC = 42424.29, BIC = 42840.84, SSBIC = 42542.40. Though traditional fit indices are not provided, the final model, with a latent interaction predicting coping motives, had lower AIC, BIC, and SSBIC than the model without a latent interaction, indicating an improvement (though only slightly) in model fit over the initial model. The final model is depicted in Figure 2. Indirect and total effects are reported in Table 4.

Figure 2.

Model of alcohol dependence symptoms (Study 1)

Note. All coefficients are unstandardized.

* p < .05

** p < .01

Table 4.

Indirect and total effects from Study 1 final model

| Model Paths | Estimate | SE | p |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

| SPECIFIC INDIRECT EFFECTS

|

|||

| Instability→Enhancement→Alcohol | 0.006 | 0.003 | .028 |

| Urgency→ Enhancement→Alcohol | 0.052 | 0.020 | .008 |

| Instability→Enhancement→Alcohol→Dependence | 0.005 | 0.002 | .029 |

| Urgency→ Enhancement→Alcohol→Dependence | 0.042 | 0.016 | .010 |

| Instability→Coping→Dependence | 0.018 | 0.005 | <.001 |

| Urgency→Coping→Dependence | 0.104 | 0.026 | <.001 |

| TOTAL INDIRECT EFFECT

|

|||

| Instability→Dependence | 0.023 | 0.006 | <.001 |

| Urgency→Dependence | 0.147 | 0.035 | <.001 |

| TOTAL EFFECTS

|

|||

| Urgency→Dependence | 0.296 | 0.063 | <.001 |

| CONDITIONAL INDIRECT EFFECTS

|

|||

| High Urgency: Instability→Coping→Dependence | 0.031 | 0.008 | <.001 |

| Low Urgency: Instability→Coping→Dependence | 0.006 | 0.006 | .342 |

| CONDITIONAL TOTAL EFFECTS

|

|||

| High Urgency: Instability→Dependence | 0.036 | 0.009 | <.001 |

| Low Urgency: Instability→Dependence | 0.010 | 0.007 | .137 |

Note. All estimates are unstandardized.

Emotional instability was positively associated with alcohol use via enhancement motives, supporting H1. Additionally, this path continued to dependence symptoms, supporting H2a. There was also a significant indirect (mediated) path to dependence symptoms via coping motives from emotional instability, supporting H2b. Urgency did not moderate the relationship between emotional instability and enhancement motives. Thus, neither H3 nor H4a were supported. To maintain parsimony, the path from instability × urgency to enhancement motives was dropped. However, urgency did moderate the association between emotional instability and coping motives, resulting in a potentiated indirect effect from instability to dependence symptoms supporting H4b. Although H4a was not supported, the total indirect effect from instability to dependence symptoms was stronger at high levels of urgency, broadly supporting H4. Furthermore, at low levels of urgency, the indirect effect between emotional instability and dependence symptoms was attenuated and no longer statistically significant.

Discussion

Study 1 examined a model of alcohol pathology indexed via symptoms of alcohol dependence. Both urgency and emotional instability were associated with alcohol use pathology, with coping and enhancement motives mediating these associations. This is consistent with previous research demonstrating that both coping and enhancement motives mediate the association between impulsivity and alcohol-related consequences (Adams et al., 2012; Littlefield et al., 2009; Magid et al., 2007). Previous research has also linked emotional instability to alcohol consequences via coping motives (Simons et al., 2005), which is consistent with our findings. Although some studies have found a link between emotional instability and alcohol use (Gottfredson & Hussong, 2013), this is the first investigation to find an association between emotional instability and alcohol use via enhancement motives. We reasoned this might occur for individuals with labile emotions, as each mood fluctuation offers the opportunity for either positive or negative reinforcement. Still, the fact that previous research has not shown this association is somewhat puzzling. Perhaps this is due to the current study consisting of frequent drinkers, whereas many studies include all participants, irrespective of drinking level.

We also found that urgency moderated the effects of emotional instability on coping motivation, but not for enhancement motives. When urgency was high, the total effects from emotional instability to dependence were potentiated, but this relationship was attenuated and not significant when urgency was low. This is consistent with several studies indicating that urgency (or impulsivity more generally) moderates the relationship between emotional instability and problematic outcomes (Dvorak, Pearson, & Kuvaas, 2013; Simons et al., 2004). For example, Simons et al. (2009) found that this interaction was a predictor of alcohol abuse symptoms, but not alcohol dependence symptoms. As abuse is no longer a diagnostic category in the DSM-5, we did not examine abuse-like symptoms. Perhaps, though, this interaction is more pertinent at low, or threshold, levels of an AUD, but, becomes less pertinent as use pathology increases in severity.

Study 2

AUDs are prevalent in the United States with 17.8% lifetime prevalence and 4.7% 12-month prevalence (Hasin, Stinson, Ogburn, & Grant, 2007). The 12-month prevalence rate of AUD among college students is appreciably higher with estimates ranging from 7.0% (Dawson et al., 2004) to 31.6% (Knight et al., 2002). In the DSM-5, a semi-dimensional approach was incorporated for AUDs, with a focus on severity (Agrawal, Heath, & Lynskey, 2011). The revised diagnostic criteria for the DSM-5 are meant to reflect more pathological use, differentiating this form of use from irresponsible drinking-related behaviors (e.g., drinking and driving) which may or may not be pathological (Agrawal et al., 2011).

This modification falls in line with three of the four postulates of alcohol dependence syndrome, which focuses on the pathological nature of disordered alcohol consumption (Edwards, 1986). First, the syndrome can be recognized by the clustering of certain elements, but not all elements need be present, or be present in the same degree. Though, as severity increases, the syndrome is likely to show increased coherence. Second, the syndrome is not all or none, but occurs with graded intensity. Third, its presentation is shaped by a pathoplastic influence of personality and culture. Thus, a model meant to examine symptoms consistent with dependence syndrome (as was the case on Study 1), should replicate in the prediction of pathological or disordered alcohol use.

The purpose of study 2 was to replicate and extend the findings from Study 1 in an independent sample. Rather than using alcohol dependence symptoms as the outcome, we used the new DSM-5 AUD criteria. Thus, our model moves beyond predicting dependence symptoms, and now examines: (a) the likelihood of meeting AUD diagnostic criteria (among the full sample), and (b) the severity of the potential AUD among those who meet diagnostic criteria. We address this using a two-part continuous hurdle model in which the logistic portion of the model predicts the likelihood of an AUD while the continuous portion of the model predicts the severity of the AUD among those who “clear” the logistic hurdle. We expected that the mediated and moderated effects found in Study 1 would replicate in Study 2, though, associations were expected to differ across the two-parts of the model (AUD hurdle vs. AUD severity). As H3 was not supported in Study 1, we did not include this as a hypothesis in Study 2. Specifically, we hypothesized:

-

H1

The association between emotional instability and alcohol use would be mediated via enhancement drinking motives: instability→ enhancement motives→alcohol use.

-

H2

The association between emotional instability and AUD would be mediated via two distinct processes: (H2a) instability→enhancement motives→alcohol use→AUD and (H2b) instability→coping motives→AUD.

-

H3

The path from emotional instability to AUD, via coping motives, would be moderated by trait urgency. Specifically, high trait urgency would potentiate the relationship between emotional instability and coping motives resulting in a more robust total indirect effect between emotional instability and AUD.

Exploratory Analysis

We also sought to examine aspects of the Study 1 model that may differ across the two parts of the hurdle model, though no specific hypotheses were specified regarding potential differences.

Methods

Participants

The current sample was drawn from a larger sample of college students (n = 945) who were recruited for a study examining “Personality and Risky Behaviors among College Students.” Individuals who reported that they never drank (n = 203) or drank less than monthly (n = 231) were removed prior to analysis. One participant who reported extreme drinking values was also removed prior to analysis. The analysis sample (n = 510; 55.10% female) ranged in age from 18–34 (M = 20.31, SD = 2.29). Participants were 95.49% Caucasian, 1.37% Asian, 0.98% African American, and 2.16% other or did not respond.

Measures

DSM-5 Alcohol Use Disorder Criteria

In the DSM-5, alcohol dependence and abuse were removed in favor of a semi-dimensional scale that rates AUDs as mild, moderate, or severe. Mild AUD is defined by the presence of 2–3 symptoms, moderate AUD as the presence of 4–5 symptoms, and severe AUD as the presence of 6 or more symptoms. There are 11 possible symptoms listed in DSM-5 allowing for diverse symptomology among those with AUD. Internal reliability for the DSM-5 AUD symptoms (α = .76) was reasonable in the current data.

Overlapping measures

Study 2 utilized several measures already described above: emotional instability (α = .85), urgency (α = .82), four measures of alcohol use (AUDIT 1–3, DDQ-M, and average BAC: α = .90), and the Drinking Motives Questionnaire (coping α = .88 and enhancement α = .91).

Procedure

Procedures for Study 2 mirrored Study 1.

Planned analysis

The current study examined the theoretical model of pathological alcohol use, tested in Study 1, from a clinical context. Specifically, we examined the likelihood of meeting DSM-5 AUD diagnostic criteria, as well as the severity of pathology for those who met criteria. The outcome was analyzed using a two-part continuous hurdle model in Mplus 7.11 (Muthén & Muthén, 2012) with maximum likelihood estimation. This allows the data to be modeled for individuals who clear the diagnostic hurdle (i.e., 2 or more AUD symptoms) as well as a continuous model of severity once the hurdle is cleared. The hurdle portion of the model is analogous to a logistic model (i.e., meets diagnostic criteria vs. does not meet criteria), while the continuous portion of the model is analogous to a zero-truncated continuous model (i.e., symptom severity among those who meet diagnostic criteria). We examined the use of a negative-binomial hurdle model, however, the continuous portion of the model had no significant dispersion, was not substantially skewed (skew = 1.37), and provided parameter estimates nearly identical to the count model. The primary advantage of a continuous model was that it allowed for a more straightforward interpretation of the indirect effects. During examination of the data, one participant reported unrealistically high weekly alcohol use. This observation was excluded from the analysis. We first tested a measurement model of the latent constructs. Next, we estimated the structural model, identified in Study 1, as a predictor of both likelihood and severity of AUD diagnosis. Currently, chi-square-based fit indices are not available for two-part continuous hurdle models. Thus, we again rely on AIC, BIC, and SSBIC to examine iterative model improvement from the baseline model. Significant latent interactions are probed at +/− 1 SD on the latent urgency variable (Aiken & West, 1991).

Results

Descriptive and bivariate statistics

Descriptive and bivariate statistics are reported in Tables 1 and 2, respectively. Age was inversely correlated with both motives and urgency. Men endorsed higher urgency and more alcohol use. The correlations among urgency, emotional instability, drinking motives, and alcohol use, were consistent with those from Study 1. Among this moderate drinking sample, 28.43% met DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for AUD – mild, 12.55% met criteria for AUD – moderate, and 8.24% met criteria for AUD – severe.

Measurement model

We first specified a measurement model to assess overall structure of the latent constructs. The initial model showed adequate, though not ideal, fit to the data, χ2(df = 216, n = 510) = 878.59, p < .001, CFI = 0.88, RMSEA = 0.08, SRMR = 0.07. However, examination of modification indices suggested several correlated errors among observed variable indicators. Six observed variable indicators with modification indices >20 were sequentially allowed to covary and the model re-estimated, χ2(df = 193, n = 510) =509.93, p < .001, CFI = 0.94, RMSEA = 0.06, SRMR = 0.06. This resulted in significantly better fit to the data, Δχ2(df = 6, n = 510) = 391.52, p < .001. Table 3 lists the factor loadings of the latent constructs.

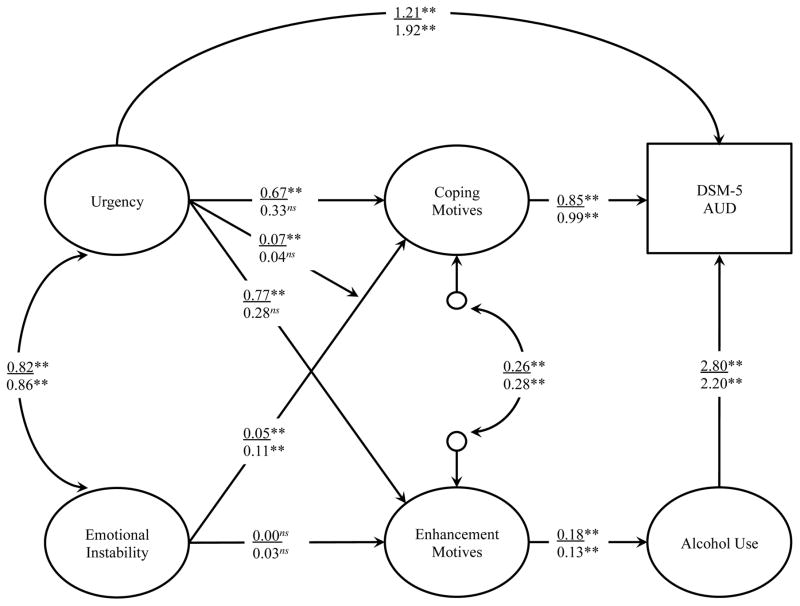

Two-part continuous hurdle model

We then tested the final path model from Study 1, with the only difference being the endogenous outcome. We analyzed the likelihood of meeting DSM-5 AUD diagnostic criteria as well as symptom severity using a two-part continuous hurdle model, allowing for the modeling of both presence and severity of alcohol pathology. Each portion of the model is discussed below. The full model is depicted in Figure 3, with hurdle coefficients above the vinculum and the severity coefficients below the vinculum.

Figure 3.

Model of likely DSM-5 AUD diagnosis (Study 2)

Note. DSM-5 AUD = Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders – 5 Alcohol Use Disorder. Coefficients from the likelihood portion of the model are depicted above of the vinculum. Coefficients from the continuous portion of the model (i.e., severity of symptoms among those who meet AUD criteria) are depicted below the vinculum. Coefficients are unstandardized.

* p < .05

** p < .01

Hurdle Model

Direct, indirect conditional, and total effects are in column one (i.e., hurdle model) of Table 5. In this portion of the model, there was no indirect association between emotional instability and alcohol use via enhancement motives; thus, H1 was not supported. Further, this resulted in a nonsignificant indirect effect between emotional instability and DSM-5 AUD likelihood, rejecting H2a. However, consistent with H2b, there was a significant indirect effect from emotional instability to the likelihood of meeting DSM-5 AUD diagnostic criteria via coping motives. In addition, the total indirect effect from emotional instability to DSM-5 AUD likelihood did not quite reach conventional levels of statistical significance (Estimate = 0.043, p = .051). Thus, H2 was partially supported. Furthermore, the indirect effects from emotional instability to the likelihood of meeting DSM-5 AUD diagnostic criteria was moderated by urgency. At low levels of urgency, the association between emotional instability and coping motives was diminished (B = −0.020, p = .299), which resulted in an attenuated and nonsignificant indirect effect between emotional instability and the likelihood of meeting DSM-5 AUD diagnostic criteria. However, at high levels of urgency, the association between emotional instability and coping motives was stronger (B = 0.102, p = .004), resulting in a potentiated indirect effect between emotional instability and the likelihood of meeting DSM-5 AUD diagnostic criteria. Thus, H3 was supported, at least in the likelihood model. In addition to hypothesized paths, there were significant associations between urgency to the likelihood of meeting DSM-5 AUD diagnostic criteria, both directly and via motives and use.

Table 5.

Indirect and total effects from Study 2 final model

| Model Paths | Hurdle Model

|

Severity Model

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | SE | p | Estimate | SE | p | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| SPECIFIC INDIRECT EFFECTS

|

||||||

| Instability→Enhancement→Alcohol | 0.000 | 0.004 | .903 | 0.003 | 0.005 | .448 |

| Urgency→Enhancement→Alcohol | 0.137 | 0.035 | <.001 | 0.035 | 0.034 | .297 |

| Instability→Enhancement→Alcohol→AUD | 0.001 | 0.010 | .903 | 0.008 | 0.010 | .444 |

| Urgency→Enhancement→Alcohol→AUD | 0.384 | 0.115 | .001 | 0.078 | 0.008 | .327 |

| Instability→Coping→AUD | 0.041 | 0.016 | .009 | 0.106 | 0.041 | .011 |

| Urgency→Coping→AUD | 0.566 | 0.179 | .002 | 0.328 | 0.191 | .086 |

| TOTAL INDIRECT EFFECTS

|

||||||

| Instability→AUD | 0.043 | 0.022 | .051 | 0.113 | 0.046 | .013 |

| Urgency→AUD | 0.950 | 0.226 | <.001 | 0.406 | 0.238 | .088 |

| TOTAL EFFECTS

|

||||||

| Urgency→AUD | 2.164 | 0.365 | <.001 | 2.325 | 0.504 | <.001 |

| CONDITIONAL SPECIFIC INDIRECT EFFECTS

|

||||||

| High Urgency: Instability→Coping→AUD | 0.102 | 0.036 | .004 | ----- | ----- | ----- |

| Low Urgency: Instability→Coping→AUD | −0.020 | 0.019 | .299 | ----- | ----- | ----- |

| CONDITIONAL TOTAL INDIRECT EFFECTS

|

||||||

| High Urgency: Instability →AUD | 0.104 | 0.039 | .008 | ----- | ----- | ----- |

| Low Urgency: Instability →AUD | −0.018 | 0.024 | .437 | ----- | ----- | ----- |

Note. All estimates are unstandardized.

Continuous Model

Direct, indirect and total effects from the zero-truncated continuous model are in column two (i.e., severity model) of Table 5. In this portion of the model, the indirect effect from emotional instability to alcohol use, via enhancement motives, was again not statistically significant, disconfirming H1 and subsequently H2a. Similar to Study 1 and the logistic portion of the model, there were significant indirect associations between emotional instability and AUD severity via coping motives, supporting H2b. Urgency did not moderate the association between emotional instability and coping motives in the severity model. Interestingly, there was no significant path from urgency to either coping or enhancement motives among people who met DSM-5 diagnostic criteria. However, the direct association between urgency and AUD severity remained significant.

Discussion

In study 2, we examined the model of pathological alcohol use from Study 1 as a predictor of AUD likelihood and severity. This allowed for the comparison of model aspects that are unique to AUD diagnostic thresholds versus AUD severity among those who likely meet the diagnostic threshold. In general, the model from Study 1 was replicated in Study 2, though several of the paths varied based on whether the model was predicting AUD likelihood or severity. Specifically, there are four important conclusions. First, several parameters were consistent across the models, indicating general risk factors for alcohol use pathology: (a) urgency was directly related to AUD likelihood and severity; (b) emotional instability was indirectly related to both likelihood and severity of AUD via coping; (c) coping was directly related to AUD likelihood and severity; and (d) enhancement was indirectly related to AUD likelihood and severity via alcohol use. All of these findings were consistent with Study 1. Second, the association between drinking to cope and urgency is an important predictor of whether or not someone meets AUD diagnostic criteria, but is not associated with severity of AUD symptoms. Third, there was high collinearity between urgency and emotional instability in the prediction of enhancement motives. Though this was not a factor in Study 1, it was in Study 2. Finally, consistent with our speculation following Study 1, urgency only moderated the indirect effect between emotional instability and the likelihood of an AUD, not AUD severity. Thus, the present results extend the DSM-IV diagnostic model presented by Simons et al. (2009) to the new DSM-5 diagnostic criteria. As hypothesized, this interaction is of primary importance for the AUD diagnostic threshold, but does not contribute to increased pathology (i.e., severity) among those who cross the threshold. In fact, the interaction effect of urgency, as well as its association with drinking motivation, is only a factor when it comes to meeting diagnostic thresholds. After this, urgency exerts a direct effect on AUD severity, but does not affect other aspects of the model.

General Discussion

In the present studies, we explored two common, internally driven, drinking motives (enhancement and coping) as potential mediators in the relation between emotional instability and clinically relevant alcohol-related outcomes, while also examining urgency as a possible moderator of these associations. Our study represents the first empirical effort to extend previous findings from DSM-IV based AUD (Simons et al., 2009) to the new the DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for AUD. Our findings highlight the importance of enhancement and coping motives in college students who report emotional instability and meet the diagnostic criteria as determined by the DSM-5. The current results also underscore the role of urgency moderating the indirect effect of coping motives in the relation between emotional instability and the likelihood of meeting AUD criteria. These results expand existing research on the etiology of alcohol use pathology among college students.

Simons and Carey (2002) offer an informative perspective grounded in their research on marijuana use and marijuana use-related problems. Based on self-medication models, one could reason that to avoid a negative emotional state, an individual may use marijuana, which is a necessary precursor to experiencing marijuana use-related problems. Therefore, the effect of affective variables on problems is expected to be mediated by frequency/quantity of use. However, another way in which emotion variables may relate to problems may be on its effect on use behaviors, “such as how a person acts while under the influence (e.g., excessively labile, aggressive) and his or her ability to mitigate the untoward consequences of a potentially destabilizing influence” (p. 72). They further argue that affective dysregulation may suggest that “use behavior may be erratic and unpredictable and thus have a greater potential to cause conflict with environmental demands” (p. 72). Applying this logic to alcohol use, one may posit that affective variables are not only a motivator of alcohol use, but may be associated with how one uses alcohol and thus be directly related to alcohol-related problems (i.e., not mediated by use). For example, in a longitudinal study, Grant and colleagues (2009) found that alcohol use fully mediated the prospective relationship between coping-depression motives and alcohol-related problems; however, coping-anxiety motives had a direct relationship with alcohol-related problems that could not be explained by its relationship with alcohol use. Thus, future scholars should continue to investigate affective states in relation to drinking motives in the prediction of problematic alcohol use outcomes.

Consistent with previous research, it is evident from this study that there are associations among emotional instability, urgency, drinking motives, and alcohol use outcomes. Given the high prevalence of alcohol use among college students (Hingson, 2010; Johnston et al., 2012), these results have significant implications for university staff, administration, and counselors. For instance, mental health professionals and prevention specialists could use the present findings to effectively identify young adults who may be at risk for problematic alcohol use and/or disorders while also uncovering motives that individuals may have for their drinking behaviors. Counseling center clinicians should be cognizant of students’ motives for drinking while also assessing emotional states and impulsive behaviors when determining the presence of an AUD. Accordingly, identified students who report problematic alcohol use in addition to these contributory risk factors may need to be referred to treatment.

In addition to assessment, treatment strategies could be tailored to address college students who consume alcohol to excess. Alcohol involvement should be examined both directly and indirectly by assessing specific risk factors, such as drinking motives and emotional functioning, to develop individualized treatment strategies that consider the etiology and maintenance of AUDs. Furthermore, preventative intervention efforts that target risk factors and motivations for AUDs should be designed and implemented specifically for students attending college. Psychoeducation about risk factors and drinking motives that may contribute to unhealthy alcohol use behaviors as well as large-scale campus screenings regarding AUDs may be key universal prevention strategies. In sum, preventing excessive alcohol use in young adults attending college is a difficult task; however, targeting emotional instability and urgency as well as enhancement and coping drinking motives may be a step in the right direction to accomplish the goal of reducing AUDs on college campuses.

Limitations

The findings should be considered within the context of the study’s limitations. First, the sample consisted of students at a single university who identified primarily as Caucasian; thus, the results may not be generalizable to other samples, such as racial minorities, clinical inpatients, and students enrolled at other universities. Future researchers should test the study hypotheses with more racially diverse, less educated, non-college, and clinical samples to either replicate or refute the study findings and potentially increase generalizability. Second, the current study was limited to self-report data, which could create bias in responding. The online format and anonymous responding likely helped limit demand characteristics; however, enhancing the reliability and validity of self-report data while utilizing a multi-modal data collection strategy is critical for conducting research on sensitive topics such as alcohol consumption. Third, and in line with the self-report data collection strategy, is the limitation of using retrospective reports, which have been shown to directly affect the validity of self-reported alcohol use, such that individuals tend to underreport alcohol use when asked retrospectively (Gmel & Daeppen, 2007). Ecological momentary assessment and other real time assessments should be used in conjunction with retrospective reports to more accurately estimate college students’ alcohol use and drinking patterns. Fourth, other possible mediators may help account for the association between emotional instability and alcohol use outcomes. Future researchers should consider including variables that assess diverse constructs, which may account for unique variance in alcohol use, severity, and dependence. Lastly, the study utilized a cross-sectional research design, which does not allow for a test of temporal precedence of associations among variables. Future longitudinal and experimental research is needed before strong causal inferences can be made regarding the directional pathways connecting these variables among college students.

Conclusions

Despite the aforementioned limitations, our study extends current research by identifying moderators and mediators of the association between emotional instability and AUDs, as defined both by the DSM-IV and DSM-5 criteria. Emotional instability serves as a risk factor for AUDs through its association with enhancement and coping motives. Moreover, in those individuals with high trait urgency, coping motives emerged as a particularly strong mediator in the relation between emotional instability and alcohol dependence symptoms as well as likelihood for AUD. Mental health professionals on college campuses are encouraged to consider the importance of emotional instability, impulsivity, and drinking motives when assessing AUD risk. Working with students to help them understand their motivations for drinking in conjunction with being aware of their affective states and the presence of any impulsive personality traits (e.g., urgency) may potentially prevent unfavorable outcomes, abuse, and/or dependence associated with alcohol use. This assessment and therapeutic process, which may utilize self-report instruments as well as clinical interviewing techniques, should help prevention specialists gain a greater understanding of how AUDs develop and provide specific targets of intervention in college students. Further investigation of the interrelations among identified risk markers (e.g., emotional instability, urgency) and drinking motives should aid in the development and enhancement of more effective alcohol use preventative intervention programs in this high-risk group.

References

- Adams ZW, Kaiser AJ, Lynam DR, Charnigo RJ, Milich R. Drinking motives as mediators of the impulsivity-substance use relation: Pathways for negative urgency, lack of premeditation, and sensation seeking. Addictive Behaviors. 2012;37(7):848–855. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agrawal A, Heath AC, Lynskey MT. DSM-IV to DSM-5: The impact of proposed revisions on diagnosis of alcohol use disorders. Addiction. 2011;106(11):1935–1943. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03517.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Newburg Park: Sage; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Baker TB, Piper ME, McCarthy DE, Majeskie MR, Fiore MC. Addiction Motivation Reformulated: An Affective Processing Model of Negative Reinforcement. Psychological Review. 2004;111(1):33–51. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.111.1.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beseler CL, Aharonovich E, Keyes KM, Hasin DS. Adult transition from at-risk drinking to alcohol dependence: The relationship of family history and drinking motives. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2008;32(4):607–616. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00619.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey KB, Hustad JTP. Are retrospectively reconstructed blood alcohol concentrations accurate? Preliminary results from a field study. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2002;63(6):762–766. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2002.63.762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conger JJ. Reinforcement theory and the dynamics of alcoholism. Quarterly Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1956;17:296–305. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper LM. Motivations for alcohol use among adolescents: Development and validation of a four-factor model. Psychological Assessment. 1994;6(2):117–128. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.6.2.117. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper LM, Frone MR, Russell M, Mudar P. Drinking to regulate positive and negative emotions: A motivational model of alcohol use. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1995;69(5):990–1005. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.69.5.990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox WM, Klinger E. A motivational model of alcohol use. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1988;97(2):168–180. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.97.2.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curcio AL, George AM. Selected impulsivity facets with alcohol use/problems: The mediating role of drinking motives. Addictive Behaviors. 2011;36(10):959–964. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cyders MA, Flory K, Rainer S, Smith GT. The role of personality dispositions to risky behavior in predicting first-year college drinking. Addiction. 2009;104(2):193–202. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02434.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cyders MA, Smith GT. Mood-based rash action and its components: Positive and negative urgency. Personality and Individual Differences. 2007;43(4):839–850. [Google Scholar]

- Cyders MA, Smith GT. Clarifying the role of personality dispositions in risk for increased gambling behavior. Personality and Individual Differences. 2008a;45(6):503–508. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2008.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cyders MA, Smith GT. Emotion-based dispositions to rash action: Positive and negative urgency. Psychological Bulletin. 2008b;134(6):807–828. doi: 10.1037/a0013341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cyders MA, Smith GT, Spillane NS, Fischer S, Annus AM, Peterson C. Integration of impulsivity and positive mood to predict risky behavior: Development and validation of a measure of positive urgency. Psychological Assessment. 2007;19(1):107–118. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.19.1.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson DA, Grant BF, Stinson FS, Chou PS. Another look at heavy episodic drinking and alcohol use disorders among college and noncollege youth. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2004;65(4):477–488. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2004.65.477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeMartini KS, Carey KB. Optimizing the Use of the AUDIT for Alcohol Screening in College Students. Psychological Assessment. 2012 doi: 10.1037/a0028519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derefinko K, DeWall NC, Metze AV, Walsh EC, Lynam DR. Do different facets of impulsivity predict different types of aggression? Aggressive Behavior. 2011;37(3):223–233. doi: 10.1002/ab.20387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dick DM, Smith G, Olausson P, Mitchell SH, Leeman RF, O’Malley SS, Sher K. Understanding the construct of impulsivity and its relationship to alcohol use disorders. Addiction Biology. 2010;15(2):217–226. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2009.00190.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimeff LA, Baer JS, Kivlahan DR, Marlatt GA. Brief Alcohol Screening and Intervention for College Students (BASICS): A harm reduction approach. New York, NY US: Guilford Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Dvorak RD, Day AM. Marijuana and Self-regulation: Examining Likelihood and Intensity of Use and Problems. Addictive Behaviors. 2014;39:709–712. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dvorak RD, Lamis DA, Malone PS. Alcohol use, depressive symptoms, and impulsivity as risk factors for suicide proneness among college students. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2013;149(1–3):326–334. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2013.01.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dvorak RD, Pearson MR, Day AM. Ecological momentary assessment of acute alcohol use disorder symptoms: Associations with mood, motives, and use on planned drinking days. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2014;22(4):285–297. doi: 10.1037/a0037157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dvorak RD, Pearson MR, Kuvaas NJ. The Five-factor Model of Impulsivity like Traits and Emotional Lability in Aggressive Behavior. Aggressive Behavior. 2013;39:222–228. doi: 10.1002/ab.21474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dvorak RD, Simons JS. Daily associations between anxiety and alcohol use: Variation by sustained attention, set shifting, and gender. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2014;(28):969–979. doi: 10.1037/a0037642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebner-Priemer UW, Eid M, Kleindienst N, Stabenow S, Trull TJ. Analytic strategies for understanding affective (in)stability and other dynamic processes in psychopathology. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2009;118(1):195–202. doi: 10.1037/a0014868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards G. The alcohol dependence syndrome: A concept as stimulus to enquiry. British Journal of Addiction. 1986;81(2):171–183. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1986.tb00313.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer S, Smith GT. Binge eating, problem drinking, and pathological gambling: Linking behavior to shared traits and social learning. Personality and Individual Differences. 2008;44(4):789–800. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2007.10.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gmel G, Daeppen J. Recall bias for seven-day recall measurement of alcohol consumption among emergency department patients: Implications for case-crossover designs. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2007;68:303–310. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2007.68.303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez VM, Reynolds B, Skewes MC. Role of impulsivity in the relationship between depression and alcohol problems among emerging adult college drinkers. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2011;19(4):303–313. doi: 10.1037/a0022720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottfredson NC, Hussong AM. Drinking to dampen affect variability: Findings from a college student sample. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2013;74(4):576–583. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2013.74.576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Hasin DS, Stinson FS, Dawson DA, Ruan WJ, Goldstein RB, … Huang B. Prevalence, correlates, co-morbidity, and comparative disability of DSM-IV generalized anxiety disorder in the USA: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Psychological Medicine. 2005;35(12):1747–1759. doi: 10.1017/S0033291705006069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant VV, Stewart SH, Mohr CD. Coping-anxiety and coping-depression motives predict different daily mood-drinking relationships. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2009;23(2):226–237. doi: 10.1037/a0015006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasin DS, Stinson FS, Ogburn E, Grant BF. Prevalence, correlates, disability, and comorbidity of DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence in the United States: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2007;64(7):830–842. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.7.830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hingson RW. Magnitude and prevention of college drinking and related problems. Alcohol Research & Health. 2010;33(1–2):45–54. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hingson RW, Zha W, Weitzman ER. Magnitude of and trends in alcohol-related mortality and morbidity among U.S. college students ages 18–24, 1998–2005. Journal Of Studies On Alcohol And Drugs. Supplement. 2009;(16):12–20. doi: 10.15288/jsads.2009.s16.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jahng S, Solhan MB, Tomko RL, Wood PK, Piasecki TM, Trull TJ. Affect and alcohol use: An ecological momentary assessment study of outpatients with borderline personality disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2011;120(3):572–584. doi: 10.1037/a0024686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Monitoring the Future national results on adolescent drug use: Overview of key findings, 2011. Ann Arbor: nstitute for Social Research, The University of Michigan; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Kalodner CR, Delucia JL, Ursprung AW. An examination of the tension reduction hypothesis: The relationship between anxiety and alcohol in college students. Addictive Behaviors. 1989;14(6):649–654. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(89)90007-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplow JB, Curran PJ, Angold A, Costello EJ. The prospective relation between dimensions of anxiety and the initiation of adolescent alcohol use. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 2001;30(3):316–326. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3003_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khantzian EJ. The self-medication hypothesis of substance use disorders: A reconsideration and recent applications. Harvard Review of Psychiatry. 1997;4(5):231–244. doi: 10.3109/10673229709030550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight JR, Wechsler H, Kuo M, Seibring M, Weitzman ER, Schuckit MA. Alcohol abuse and dependence among U.S. college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2002;63(3):263–270. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2002.63.263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuntsche E, Knibbe R, Gmel G, Engels R. Why do young people drink? A review of drinking motives. Clinical Psychology Review. 2005;25(7):841–861. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2005.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuntsche E, Stewart SH, Cooper ML. How stable is the motive-alcohol use link? A cross-national validation of the Drinking Motives Questionnaire Revised among adolescents from Switzerland, Canada, and the United States. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2008;69(3):388–396. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2008.69.388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuntsche E, von Fischer M, Gmel G. Personality factors and alcohol use: A mediator analysis of drinking motives. Personality and Individual Differences. 2008;45(8):796–800. [Google Scholar]

- Kuvaas NJ, Dvorak RD, Pearson MR, Lamis DA, Sargent EM. Self-regulation and alcohol use involvement: A latent class analysis. Addictive Behaviors. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.09.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Littlefield AK, Sher KJ, Wood PK. Is “maturing out” of problematic alcohol involvement related to personality change? Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2009;118(2):360–374. doi: 10.1037/a0015125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Littlefield AK, Vergés A, Rosinski JM, Steinley D, Sher KJ. Motivational typologies of drinkers: Do enhancement and coping drinkers form two distinct groups? Addiction. 2013;108(3):497–503. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2012.04090.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loukas A, Krull JL, Chassin L, Carle AC. The relation of personality to alcohol abuse/dependence in a high-risk sample. Journal of Personality. 2000;68(6):1153–1175. doi: 10.1111/1467-6494.00130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magid V, Colder CR. The UPPS Impulsive Behavior Scale: Factor structure and associations with college drinking. Personality and Individual Differences. 2007;43(7):1927–1937. [Google Scholar]

- Magid V, MacLean MG, Colder CR. Differentiating between sensation seeking and impulsivity through their mediated relations with alcohol use and problems. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32(10):2046–2061. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merrill JE, Read JP. Motivational pathways to unique types of alcohol consequences. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2010;24(4):705–711. doi: 10.1037/a0020135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merrill JE, Wardell JD, Read JP. Drinking motives in the prospective prediction of unique alcohol-related consequences in college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2014;75(1):93–102. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2014.75.93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller JD, Flory K, Lynam D, Leukefeld C. A test of the four-factor model of impulsivity-related traits. Personality and Individual Differences. 2003;34(8):1403–1418. doi: 10.1016/s0191-8869(02)00122-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus Statistical Modeling Software: Release 7.0. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Oliver MNI, Simons JS. The affective lability scales: Development of a short-form measure. Personality and Individual Differences. 2004;37(6):1279–1288. [Google Scholar]

- Read JP, Kahler CW, Strong DR, Colder CR. Development and Preliminary Validation of the Young Adult Alcohol Consequences Questionnaire. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2006;67(1):169–177. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2006.67.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Read JP, Merrill JE, Kahler CW, Strong DR. Predicting functional outcomes among college drinkers: Reliability and predictive validity of the Young Adult Alcohol Consequences Questionnaire. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32(11):2597–2610. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders JB, Aasland OG, Babor TF, de la Fuente JR. Development of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): WHO collaborative project on early detection of persons with harmful alcohol consumption: II. Addiction. 1993;88(6):791–804. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1993.tb02093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons JS, Carey KB. Risk and vulnerability for marijuana use problems: The role of affect dysregulation. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2002;16(1):72–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons JS, Carey KB. An affective and cognitive model of marijuana and alcohol problems. Addictive Behaviors. 2006;31(9):1578–1592. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons JS, Carey KB, Gaher RM. Lability and Impulsivity Synergistically Increase Risk for Alcohol-Related Problems. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 2004;30(3):685–694. doi: 10.1081/ada-200032338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons JS, Carey KB, Wills TA. Alcohol abuse and dependence symptoms: A multidimensional model of common and specific etiology. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2009;23:415–427. doi: 10.1037/a0016003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons JS, Dvorak RD, Batien BD, Wray TB. Event-level associations between affect, alcohol intoxication, and acute dependence symptoms: Effects of urgency, self-control, and drinking experience. Addictive Behaviors. 2010;35(12):1045–1053. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons JS, Gaher RM, Correia CJ, Hansen CL, Christopher MS. An affective-motivational model of marijuana and alcohol problems among college students. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2005;19(3):326–334. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.19.3.326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith GT, Fischer S, Cyders MA, Annus AM, Spillane NS, McCarthy DM. On the validity and utility of discriminating among impulsivity-like traits. Assessment. 2007;14(2):155–170. doi: 10.1177/1073191106295527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson BL, Dvorak RD, Kuvaas NJ, Williams TJ, Spaeth DT. Cognitive control moderates the association between emotional instability and alcohol dependence symptoms. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2015;29(2):323–328. doi: 10.1037/adb0000045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tragesser SL, Sher KJ, Trull TJ, Park A. Personality disorder symptoms, drinking motives, and alcohol use and consequences: Cross-sectional and prospective mediation. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2007;15(3):282–292. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.15.3.282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler H, Lee JE, Kuo M, Lee H. College binge drinking in the 1990s: A continuing problem: Results of the Harvard School of Public Health 1999 College Alcohol Study. Journal of American College Health. 2000;48(5):199–210. doi: 10.1080/07448480009599305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whiteside SP, Lynam DR. The Five Factor Model and impulsivity: Using a structural model of personality to understand impulsivity. Personality and Individual Differences. 2001;30(4):669–689. [Google Scholar]

- Wills TA, Simons JS, Forbes M, McGurk M, Nagakura A. Confirmatory Analysis for Urgency and Self-Regulation Measures Related to Adolescent Substance Use. Paper presented at the Annual Convention of the American Psychological Association; Oahu, HI. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Wray TB, Simons JS, Dvorak RD, Gaher RM. Trait-based affective processes in alcohol-involved “risk behaviors”. Addictive Behaviors. 2012;37(11):1230–1239. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]