Abstract

Hydrogen production from water splitting by photo/photoelectron‐catalytic process is a promising route to solve both fossil fuel depletion and environmental pollution at the same time. Titanium dioxide (TiO2) nanotubes have attracted much interest due to their large specific surface area and highly ordered structure, which has led to promising potential applications in photocatalytic degradation, photoreduction of CO2, water splitting, supercapacitors, dye‐sensitized solar cells, lithium‐ion batteries and biomedical devices. Nanotubes can be fabricated via facile hydrothermal method, solvothermal method, template technique and electrochemical anodic oxidation. In this report, we provide a comprehensive review on recent progress of the synthesis and modification of TiO2 nanotubes to be used for photo/photoelectro‐catalytic water splitting. The future development of TiO2 nanotubes is also discussed.

Keywords: modification, photocatalysis, photo/photoelectro‐catalytic water splitting, synthesis, TiO2 nanotubes

1. Introduction

The rapid development of globalization and industrialization has caused a series of serious environmental problems to the world's population.1, 2, 3, 4, 5 The supplies of fossil energy sources such as oil and gas are depleting exponentially and may be depleted within the next several decades if the current trend continues. The consumption of fossile fuels has also contaminated the environment, leading to global warming and climate changes due to the greenhouse effect.6, 7, 8, 9, 10 To address these concerns, there has been considerable attention devoted to the development of clean and renewable energy sources to meet the increasing energy demand.11, 12, 13, 14 Water splitting for hydrogen production in the presence of a semiconductor photocatalyst has been studied extensively as a potential method to provide hydrogen, a clean energy source. On exposure to sunlight, solar energy can be absorbed on photocatalysts to produce hydrogen and degrade pollutants at the same time, paving the way for producing clean energy source and creating a cleaner environment.15, 16, 17, 18, 19

Since the titanium dioxide (TiO2) was discovered for its potential for water photolysis by Fujishima and Honda in 1972,20 it has been widely investigated in photocatalytic degradation of pollutants,21, 22 photoreduction of CO2 into energy fuels,23, 24 water splitting,25, 26 supercapacitors,27, 28 dye‐sensitized/quantum dot‐sensitized/perovskite solar cells,29, 30, 31 lithium‐ion batteries,32, 33 biomedical devices34, 35 and self‐cleaning.36, 37 After Iijima et al. discovered carbon nanotubes (CNTs) in 1991,38 much more interests were activated in the one dimensional (1D) dimensional tubular nanomaterials. In contrast to CNTs, TiO2 nanotubes were readily fabricated by template‐assisted technique,39 solvothermal method,40, 41 hydrothermal method,42, 43 and electrochemical anodic oxidation.44, 45 Different fabrication methods have their own unique advantages and features. Since TiO2 nanotubes were first synthesized by Hoyer using template‐assisted method,46 the effects of fabrication factors, doping methods and applications have expanded rapidly.47, 48, 49, 50 However, there are still some intrinsic drawbacks that have limited the wide application of TiO2 nanotubes in some fields. On the one hand, wide band gap makes TiO2 (anatase: 3.2 eV, rutile: 3.0 eV) occupy only 3–5% of the total solar spectrum. On the other hand, fast recombination of photogenerated electron‐hole pairs also leads to decreased efficiency in the photo/photoelectro‐catalytic activity.51, 52, 53, 54, 55 Therefore, many works have been devoted to enlarging the photocatalytic active surface, forming Schottky junction or heterojunctions, and engineering the band structure to match particular energy levels. These efforts aim to widen the visible light absorption, separate the recombination of electron/holes for improved photo‐to‐energy conversion efficiency.56, 57, 58, 59, 60

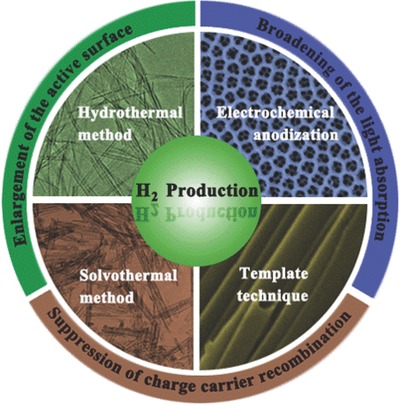

In this review, the preparation methods of TiO2 nanotube are summarized and the optimum conditions are proposed (Scheme 1 ). Besides, this review will address various methods to modify TiO2 nanotube by enhancing the visible light absorption and suppressing the recombination of photogenerated electron/hole pairs. In addition, the mechanism and application of photo/photoelectro‐catalytic water splitting are comprehensively discussed. Challenges and the future development on 1D TiO2 nanotubes will be discussed in the end.

Scheme 1.

Schematic illustration of the preparation methods and modification strategies of TiO2 nanotubes for enhanced solar water splitting.

2. Basic Mechanism of Photo/photoelectro‐catalytic Water Splitting for Hydrogen Generation on TiO2 Nanotubes

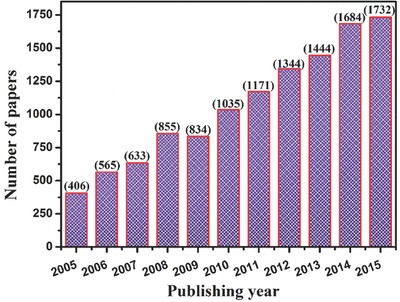

Energy crisis and environmental issues are hot topics all over the word. Hydrogen is considered to be an ideal fuel for future energy demands because it can be produced in a sustainable manner and its consumption does not generate environmental pollutants. Besides, the photo/photoelectro‐catalytic water splitting reaction for hydrogen generation can be integrated with simultaneous pollutant removal in the oxidation process.61, 62, 63 After the early work of TiO2 photoelectrochemical hydrogen production reported by Fujishima and Honda, scientific and engineering interests in semiconductor photocatalysis have expanded tremendously.64, 65, 66, 67 The number of technical publications on water splitting for hydrogen production has grown rapidly; more than 10000 papers have been published in the last decade (Figure 1 ).

Figure 1.

Number of articles published on photo/photoelectro‐catalytic water splitting for hydrogen production from 2005 to 2015 (Data was obtained from web of science database on March 31, 2016 using water splitting, hydrogen production and generation as key words).

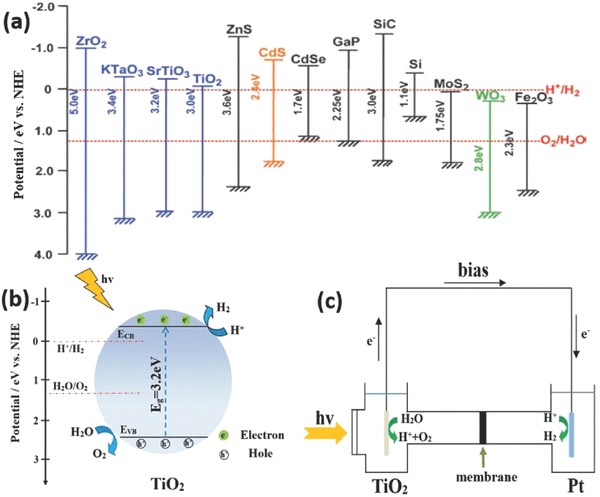

The mechanism of water splitting can be elaborated as follows. The water molecules are reduced by electrons to form H2, while they are also oxidized by holes to form O2 at the same time. The reduction potential (H+/H2) of water is 0 V and the oxidation potential (H2O/O2) is 1.23 V with respect to the normal hydrogen electrode (NHE). For hydrogen production, the conduction band (CB) level should be more negative than hydrogen production level (0 V) while the valence band (VB) should be more positive than water oxidation level (1.23 V) for efficient oxygen production from water by photo/photoelectro‐catalysis.68, 69, 70, 71 As we can see from band levels of various semiconductor materials (Figure 2 a), TiO2 is one of the most used semiconductors for hydrogen production as a result of their suitable band structures, low environmental impact and low toxicity, and high stability, while some other semiconductors such as SiC, CdS may not be suitable for water splitting because of the problem of photocorrsion.72, 73 In a photocatalytic water splitting process (Figure 2b), electrons at the valance band of TiO2 are exicted to the conduction band upon UV illumination. Hydrogen ions are reduced into hydrogen by the electrons at the conduction band, while the generated holes at the valence band oxide water molecules into oxygen (or degrade pollutants if they are presentin the solution). Apart from photocatalytic water splitting, photoelectrocatalytic water splitting has been proven a facile and promising route to solve the difficult problem of the fast recombination between photogenerated electron and holes, which can be beneficial for improving the photoelectrocatalytic hydrogen production efficiency. As depicted in Figure 2c, when a low bias potential is applied on the TiO2 nanotube, it can significantly facilitate the transfer of photocarriers and suppressed the recombination of photogenerated electrons and holes. Upon UV light irradiation, the electrons can leap up the valance band of TiO2 to the conduction band, and then be driven to the counter electrode via the external circuit, leaving the holes on the surface of the TiO2 nanotubes electrode. Meanwhile, a large number of active species were produced. The electrons at the counter electrode can react with hydrogen ions to generate hydrogen, while the holes at the valance band can react with water molecules to generate oxygen and hydrogen ions, or to degrade the pollutants, similar to the above discussed photocatlystic process.74, 75, 76, 77, 78, 79 The reaction mechanism is described as follows:

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

Figure 2.

Relationship between band structure of semiconductor and redox potentials of water splitting (a). Schematic diagram for photocatalytic (b) and photoelectrocatalytic (c) water splitting on TiO2, respectively. (a) Reproduced with permission.72 Copyright 2009, American Chemical Society.

Compared to TiO2 nanoparticles, TiO2 nanotubes are widely used in water splitting due to their ordered tubular structure, strong ion‐exchange ability, relatively longer lifetime of electron/hole pairs.80, 81, 82, 83 However, the power conversion efficiency from solar to hydrogen by TiO2 nanotubes photo/photoelectro‐catalytic water splitting is still low, mainly due to fast (in absolute terms) recombination of electron/hole pairs and inability to utilize visible light. Therefore, continuous efforts have been made to solve these problems, which will be discussed in section 4.84, 85, 86

The photo/photoelectro‐catalytic activity for water splitting can be directly evaluated by the H2 or O2 gas evolution rate (μmol h–1 g–1 or μmol h–1 cm–2) and photocurrent density (mA cm–2). For photocatalytic systems, the time course and stoichiometry of H2 and O2 evolution should be taken into account for the evaluation of activity. In addition, for photoelectrocatalytic systems, the applied potential, wavelength and intensity of incident light should also be provided when performing an evaluation of activity. In order to compare the activity of photocatalysts under different reaction conditions, it is important to determine the overall quantum yield (QY) of TiO2 nanotube for water splitting.87 The overall QY is defined in Equation (5) and (6) for H2 and O2, respectively.73

| (5) |

| (6) |

Similarly, the incident photon to charge carrier generation efficiency (IPCE) in a photoelectrocatalytic system describes the ratio of effective photons or generated charges that generate electrochemical current to “incident photons” of monochromatic light. IPCE at different wavelengths is determined from the short circuit photocurrents (Isc) monitored at different excitation wavelengths (λ) to compare the photoresponse of the samples using Equation (7).88

| (7) |

where Isc is the photocurrent density (mA cm–2) under illumination, λ is the wavelength (nm) of incident radiation, and Iinc is the incident light power intensity on the TiO2 electrode (mW cm–2).

Besides, the turnover number (TON) for H2 generation is usually defined by the number of reacted molecules to that of an active site. However, it is often difficult to determine the number of active sites for photocatalysts. Therefore, the number of reacted electrons to the number of atoms in TiO2 nanotube (Equation (8)) or on the surface of TiO2 nanotube (Equation (9)) is employed as the TON.72

| (8) |

| (9) |

It should be noteworthy that the quantum yield and turnover number is different from the solar energy conversion efficiency that is usually used for evaluation of hydrogen production activity. The overall conversion of solar energy is given by the following equation:72

| (10) |

3. Processing Techniques

Microstructure of TiO2 nanotubes plays a key role in their properties and photocatalytic efficiency. Various methods have been developed to prepare 1D TiO2 nanotubes in the past. In this section, we briefly introduce several main preparation methods, namely, the hydrothermal, solvothermal, electrochemical anodization, and template‐assisted method. Each fabrication method has unique advantages and functional features, comparison among these approaches is summarized in Table 1 .89

Table 1.

Comparison of available methods for TiO2 nanotubes preparation

| Fabrication method | Reaction conditions | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrothermal method | High pressure and high temperature. | High nanotube production rate. | Long reaction duration. |

| Aqueous based solvent. | Easy to enhance the features of titanium nanotubes. | Difficult to achieve uniform size. | |

| Solvothermal method | High pressure and high temperature. | Better control of the nanosize, crystal phase and narrow size distribution. Varieties of chosen organic solvent. | Critical reaction conditions. |

| Organic solvent. | Long reaction time. | ||

| Electrochemical anodization method | 5–50 V and 0.2–10 h under ambient conditions. | Ordered alignment with high aspect ratio. | Limited mass production. |

| F–‐based buffered electrolytes and organic electrolytes, F–‐free electrolytes. | Controllable dimension of nanotubes by varying the voltage, electrolyte, pH and anodizing time. | Length distribution and separation of nanotubes over a large surface area is not well‐developed. | |

| Template method | AAO, ZnO etc. as sacrificial template under specific conditions. | Controllable scale of nanotube by applied template. | Complicated fabrication process. Contamination or destroy of tubes may occur during fabrication process. |

| Uniform size of nanotubes. |

3.1. Hydrothermal Method

Hydrothermal is an advanced nanostructural material processing technique encompassing the crystal growth, crystal transformation, phase equilibrium, and final ultrafine crystals formation.90 The hydrothermal method is the most widely used method for fabrication of 1D TiO2 nanostructures due to its simplicity and high productivity. Since the fabrication of TiO2‐based nanotubular materials through hydrothermal method by treating amorphous TiO2 powder at high temperatures in a highly concentrated NaOH solution without sacrificial templates was reported by Kasuga et al. for the first time in 1998,91 many efforts have been made on the synthesis of TiO2 nanotubes in such way.92, 93

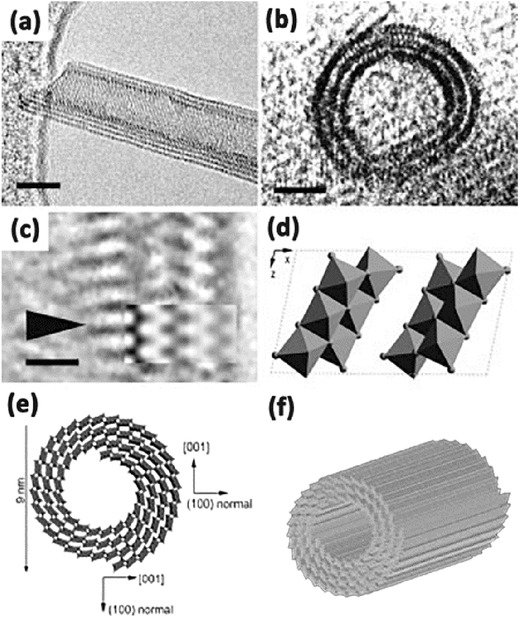

In a typical synthesis process, precursors of TiO2 and reaction solutions are mixed and enclosed in a stainless steel vessel under controlled temperature and pressure. After the reaction is complete, rinse with deionized water and acidic solution is needed to remove the impurities. Usually, there is a nearly 100% conversion for the precursors to TiO2 nanotubes in one single hydrothermal process. The morphologies of the obtained TiO2 depend on the process parameters, such as the structure of raw materials, the concentration of reacting solutions, reaction temperature and time, and even the acid washing. That is to say, the synthesis is controllable, hollow structure of the nanotubes with several layers via a single alkali treatment can be achieved (Figure 3 ).94

Figure 3.

HRTEM image (a,b) of the multilayers TiO2 nanotubes. Enlarged HRTEM image (c) of a part in (a). Structure model of one‐unit cell of H2Ti3O7 on the [010] projection (d). Schematic drawing of the structure of nanotubes (e,f). Reproduced with permission.94

The synthesis method can be classified into the acid‐hydrothermal and alkali‐hydrothermal approaches according to the reactants used for the hydrothermal synthesis of 1D TiO2 nanostructures. In the former method, the reactants are usually titanium salts with inorganic acid, and normally this method leads to the formation of TiO2 nanorods. Accordingly, the reactants in the latter method are generally TiO2 nanoparticles reacting in sodium hydroxide solution. The dissolution‐recrystallization is always involved in this process and the products include nanotubes or nanowires. These two methods have different reaction mechanisms, which produce different morphology and crystalline phases of the product in the 1D nanostructures.

Though the hydrothermal process is a cost‐effective method, and the as‐prepared nanotubes have good dispersibility and high purity showing great potential for the formation of TiO2 nanostructures, some shortcomings still should not be ignored which limit its applications. For example, slow reaction kinetics result in long reaction time and limited length of the nanotubes. And nanotubes prepared are always non‐uniform on a large‐scale. For improvement, various approaches have been explored, such as ultrasonication assisted, microwave‐assisted, and rotation‐assisted hydrothermal methods. Nawin et al. has proved that the length of TiO2 nanotube becomes longer by the hydrothermal process coupled with sonication pretreatment.95 By varying size of raw TiO2 powder (400 nm and 1 μm), reaction temperature and sonication power, morphology of TiO2 nanostructures, length of TiO2 nanotube could be easily adjusted (Figure 4 a–c). TiO2 with various morphologies such as whiskers, nanotubes and nanofibers can be obtained at different sonication powers.96, 97 Huang et al. demonstrated a new method based on microwave irradiation for the preparation of rutile/titania‐nanotube composites that exhibit highly efficiency in visible light induced photocatalysis (Figure 4d,e).98 The nanocomposites exhibit multilayer‐wall morphologies with open‐ended cylindrical structures, and the presence of the rutile phase in the TiO2 nanotubes enhanced the light‐harvesting efficiency in photocatalytic reactions. In 2011, a facile vapor phase hydrothermal method for direct growth of vertically aligned TiO2 nanotubes with larger diameter on a titanium foil substrate was reported for the first time by Zhao et al.99 The resultant nanotubes consisted of more than 10 titanate layers, and displayed external diameters of 50–80 nm with an average wall thickness of 10 nm. Typically, unlike the mechanism frequently encountered in conventional liquid‐phase hydrothermal reactions, a distinctive nanosheet roll up mechanism can be observed during the nanotubes formation process (Figure 5 a–g). Torrente et al. synthesized TiO2 nanotubes with even longer length than conventional method at a low revolving speed.100 In particular, Tang et al. reported a new process to grew elongated TiO2 nanotubes with length up to tens of micrometers by a stirring hydrothermal method.101 This study confirmed that the mechanical force‐driven stirring process simultaneously improved the diffusion and surface reaction rate of TiO2 nanocrystal growth in solution phase, and the nanotube aspect ratio is strongly related to the precursor and the stirring rate. This method has provided 1D TiO2‐based nanotubular materials for long‐life and ultrafast rechargeable lithium‐ion batteries.

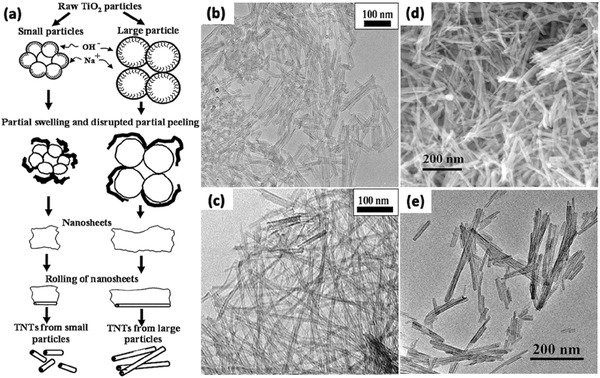

Figure 4.

Schematic model of formation of TNTs from different size of raw TiO2 particles (a). TEM images of TiO2 nanotubes synthesized at reaction temperature of 120 °C with sonication power of 0 W (b) and 7.6 W (c). FE‐SEM (d) and TEM (e) images of the rutile/TiO2 nanotubes. (a–c) Reproduced with permission.95 Copyright 2009, Elsevier. (d,e) Reproduced with permission.98 Copyright 2013, Elsevier.

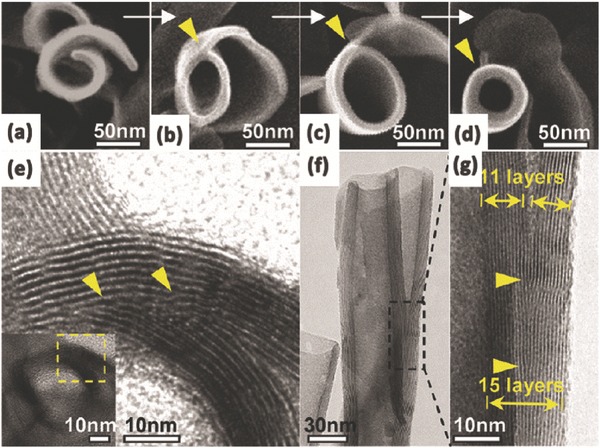

Figure 5.

SEM images of the morphological evolution from a nanosheet into a nanotube (a–d); TEM image of a joint of a scrolled nanosheet in cross‐section (e); side‐view TEM image of a nanotube with an undetached exfoliating nanosheet (f) and its magnified TEM image (g). Reproduced with permission.99 Copyright 2011, American Chemical Society.

3.2. Solvothermal Method

The solvothermal method is also widely used in synthesizing metallic oxides such as ZrO2, ZnO, and Fe3O4 etc., and it is almost identical to the hydrothermal method except that the aqueous solutions used here are organic solvents.102, 103, 104 However, the temperature and pressure can be controlled at a higher level than that in hydrothermal method because a variety of chosen organic solvent have higher boiling points, thus it has better control with respect to the nanosize, crystal phase, size distribution and agglomeration of products.105, 106 The solvent plays a key role in determining the crystal morphology. Solvents with different physical and chemical properties can influence the solubility, reactivity, the diffusion behavior of the reactants, and the crystallization behavior of the final products. For example, TiO2 nanorods could be prepared by hydrothermal treatment of a titanium trichloride aqueous solution with NaCl at 160 °C for 2 h,107 while when TiO2 powders are put into NaOH aqueous solution and held at 20–110 °C for 20 h in an autoclave, TiO2 nanotubes are obtained.91 Typically, the solvothermal synthesis is usually conducted in an organic solvent such as ethanol and ethylene glycol, while the hydrothermal method reacts in water solutions.108, 109 Wang et al. successfully synthesized open‐ended TiO2 nanotubes by the solvothermal method using glycerol as solvents (Figure 6 a,b).110 The nanotubes consisted of continuous bilayers or multilayers (Figure 6b); this indicated that the nanotubes may probably be formed by scrolling conjoined multilayer nanosheets. And it exhibited a favorable discharge performance as anode materials in the application of lithium‐ion batteries. Zheng et al. prepared visible‐light‐responsive N‐doped TiO2 nanotubes via an environment‐conscious solvothermal treatment of protonated titanate nanotubes in an NH4Cl/ethanol/water solution at modest temperatures (Figure 6c,d).111 The obtained N‐doped TiO2 nanotubes are thermally stable and robust for photodegradation of methylene blue under visible light irradiation.

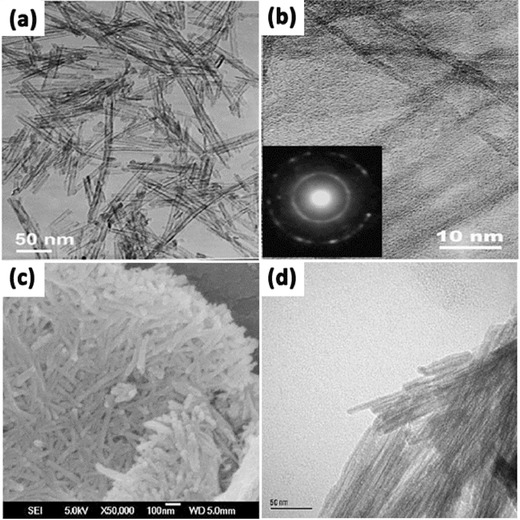

Figure 6.

TEM images (a,b) at different magnifications of TiO2 synthesized by the solvothermal method (inset of b: electron diffraction pattern of a single TiO2 nanotube). SEM (c) and TEM (d) image of N‐doped TiO2 nanotubes fabricated by the solvothermal method. (a,b) Reproduced with permission.110 Copyright 2006, American Chemical Society. (c,d) Reproduced with permission.111 Copyright 2008, Royal Society of Chemistry.

3.3. Electrochemical Anodization Method

The anodization method can be effectively employed to fabricate in situ nanotube arrays and has been widely used in anodizing various metals, such as 1D TiO2 nanotube arrays (TiO2 NTAs). Compared with the nanotubes constructed by the hydrothermal method, the size controllable TiO2 nanotube arrays fabricated by the anodization method are highly ordered and oriented perpendicular to the surface of the electrode substrate. Typically, these TiO2 NTAs are ideal photoanode materials which have been used for a long time due to its excellent stability, non‐toxicity, recyclability and cost‐effectivity.

In a typical experiment, a clean Ti plate is anodized in a fluoride‐based electrolyte (HF, NaF, or KF) using platinum as counter electrode under 10–25 V for 10–30 min.112 Usually, acetic acid, HNO3, H3PO4, H2SO4 or citric acid are used to adjust the acidity.106 Crystallized TiO2 nanotubes are obtained after the anodized Ti plate is annealed at 300–500 °C for 1–6 h in oxygen.113 In general, the length and wall thickness of the TiO2 NTAs could be controlled over a wide range with the applied potential, electrolyte type and concentration, pH, and temperature etc.114 The first known report on porous anodized TiO2 was published by Assefpour‐Dezfuly et al. in 1984, where the Ti metal was etched in alkaline peroxide at first, and then anodized in chromic acid.115 After that, Zwilling et al. reported the formation of self‐organized porous/tubular TiO2 structures in fluoride‐based electrolyte in 1999,116, 117 greatly prompting the development of tubular TiO2 structures.

The length of nanotubes in the first generation is limited to only approximately 500 nm or less, and it could not meet the requirement for some specific applications. In 2001, Grimes et al. first reported the preparation of self‐organized TiO2 nanotube arrays by utilizing anodization of titanium foil in a H2O‐HF electrolyte at room temperature.118 Subsequently, buffered neutral electrolytes containing various fluoride salts such as NaF or NH4F had been developed to prepare the second generation of nanotubes which have longer lengths up to several micrometers.119, 120, 121, 122, 123 It is noted that the nanotube length was increased to about 7 μm by controlling the pH of the anodization electrolyte and reducing the chemical dissolution of TiO2 during anodization.124 Later, the third generation TiO2 NTAs were anodized in non‐aqueous organic solvent electrolyte containing F– with smooth and taller nanotube morphologies. Various organic solvents such as glycerol, ethylene glycol, formamide, and dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) had been used for the formation of TiO2 nanotubes with lengths up to approximately hundreds of micrometers.125, 126, 127, 128, 129 Some efforts have been made to produce TiO2 NTAs in a fluorine‐free electrolyte such as HClO4‐containing electrolyte, and they are commonly considered as the fourth‐generation nanotubes.130, 131 In addition, hexagonal nanotubes close packed arrays with high order via a multi‐step approach were achieved by Schmuki and Shin et al.,132, 133 and it was also thought as the fifth generation nanotubes. Since then, much effort has been made to optimize experimental parameters with different electrolytes or reacting conditions in order to efficiently achieve high quality self‐organized TNAs.134, 135, 136

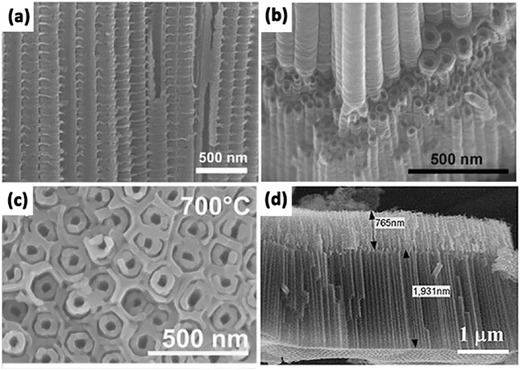

In general, the anodization time and etching rate decide the tube length and nanotube‐layer thickness, while the diameter of the nanotubes is controlled linearly by the applied voltage.137, 138, 139, 140 And the nanotubes grown from organic electrolytes, such as ethylene glycol, glycerol, or ionic liquids, show some significant differences in morphology and composition compared with nanotubes grown in F–‐based aqueous electrolytes.141 For example, tube length is limited to 500–600 nm in electrolytes at low pH. In neutral electrolyte systems, the reduced chemical dissolution can lead to layer thicknesses of up to 2–4 μm. While in some glycerol or ethylene glycol based systems, reduced water content can further decrease chemical dissolution, thus the growth of tube could be significantly extended.137 Importantly, etching of the tube at their top could form grass‐like morphologies, which lead to inhomogeneous top structures (Figure 7 a,b,e,f,i,j). The collapsed and bundled tube tops mainly because the walls become too thin to support the capillary forces or their own weight during drying. The morphology of either thinned or partially dissolved tube walls is not favorable for carrier transport, and limits the energy conversion efficiency, thus efforts must be put forward to avoid this irregular nanotube structure during anodization. Kim et al. demonstrated a simple approach to prevent this effect by pretreating the polished Ti surfaces in F‐containing electrolytes to form a comparably compact rutile layer in the initial stages of anodization.142 This layer shows a comparably high resistance to chemical etching and can efficiently protect the tube tops, and thus allow the growth of nanotube layers with highly ordered and defined morphology in the subsequent tube growth process (Figure 7c,d). This ordered “nanograss”‐free tubes show significantly increased photocurrents and conversion efficiencies in dye‐sensitized solar cells. Similarly, Song et al. obtained anodic self‐organized TiO2 nanotube layers with a significantly improved tube morphology by forming a rutile layer on the Ti substrate by high temperature oxidation in air before the anodic tube growth.143 As a result, high aspect ratio nanotubes can be grown with an intact tube top (Figure 7g,h). In addition, Albu's group reported a very simple approach to produce anodic TiO2 nanotube arrays with highly defined and ordered tube openings by coating the surface with a photoresist that is slowly soluble in the electrolyte.144 With the thin layer of photoresist acting as a sacrificial initiation layer, open and “grass”‐free TiO2 nanotubes with clear tubular shape could be easily synthesized (Figure 7k,l).

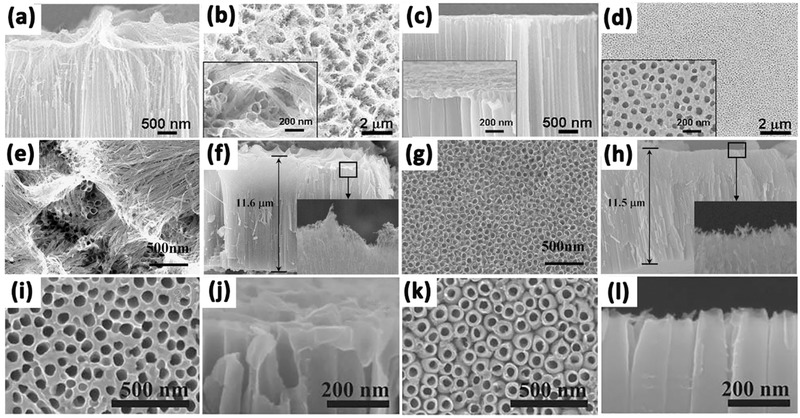

Figure 7.

Side‐view (a) and top‐view (b) SEM images of TiO2 nanotube layers anodized in ethylene glycol and HF on non‐polished Ti plate. Side‐view (c) and top‐view (d) images of TiO2 nanotube layers anodized in ethylene glycol and HF on polished Ti plate. SEM images of TiO2 nanotube layers anodized in ethylene glycol and NH4F without (e,f) and with (g,h) protective layer. Top view (i) and side view (j) of the sample anodized under conventional method; top view (k) and side view (l) of the sample anodized using the new method at 80 °C post‐baking temperature for 10 min. (a–d) Reproduced with permission.142 Copyright 2008, Elsevier. (e–h) Reproduced with permission.143 Copyright 2009, The Electrochemical Society. (i–l) Reproduced with permission.144

Based on the chemical etching mechanism, by changing the anodization conditions, such as the applied voltage during the tube growth process, various modifications in the tube geometry can be achieved. For example, bamboo‐like stratification layers can be generated when stepping first to a lower voltage for a time and then stepping back to the original high voltage (Figure 8 a).145, 146 If the voltage is lowered during anodization, tube growth will be stopped or drastically slowed down. And at some point the oxide is thinned down sufficiently to continue growth under lower field conditions (the tube diameter will in this case adjust to the lower field and thus tube branching may occur (Figure 8b) owing to the permanent etching of the tube bottom in the fluoride environment. If tube wall separation (tube splitting) is faster than the etching process through the tube bottom, then second tube layer will initiate between the tubes and double‐walled tubes would be formed (Figure 8c).147, 148 Moreover, when the first layer of nanotubes is treated with an organic hydrophobic monolayer (octadecylphosphonic acid, ODPA), and re‐grown again in an organic electrolyte, amphiphilic tube stacks would be fabricated (Figure 8d).149

Figure 8.

(a) Bamboo nanotubes fabricated by alternating voltage anodization. (b) branched nanotubes by voltage stepping. (c) double‐walled nanotubes. (d) amphiphilic double‐layer tubes.(a,b) Reproduced with permission.145 (c) Reproduced with permission.148 (d) Reproduced with permission.149 Copyright 2009, American Chemical Society.

3.4. Template Method

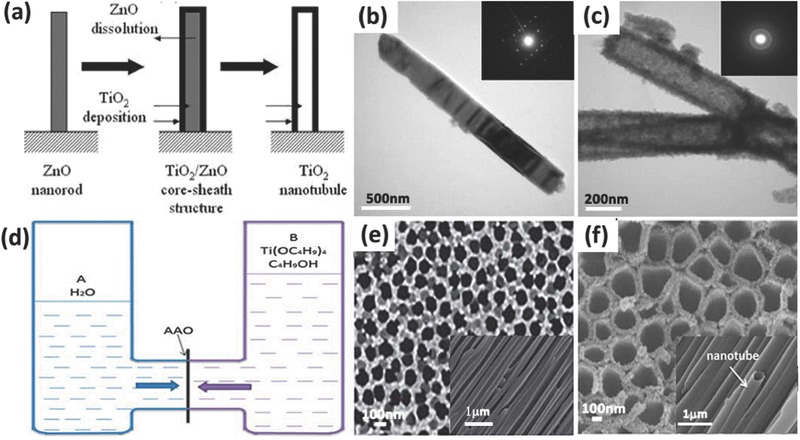

Template method is a very commonly used synthesis technique that prepares nanostructure with a morphology which follows the known and characterized templates. Typically, anodic aluminium membranes (AAM), ZnO, and silica etc. are used as templates,150, 151, 152, 153 because they can be easily removed via chemical etching or combustion, leaving the resultants with a pre‐set porosity and reversely duplicated morphology. In general, numerous TiO2 materials in various morphologies can be prepared easily by adjusting the morphology of the template material in certain conditions, such as TiO2 nanoparticles,154 TiO2 hollow fibers,155, 156 TiO2 spheres157, 158 and so on. Templates can be divided into positive and negative according to the way the materials grow with the templates.159, 160 Positive template synthesis leads to outer surface coating of the materials,161 while negative template synthesis are suitable for those to be deposited inside the template inter space.162 Lee et al. fabricated aligned TiO2 one‐dimensional nanotube arrays using a one‐step positive templating solution approach (Figure 9 a–c).163 The deposition of TiO2 and the selective‐etching of the ZnO template proceeded at the same time through careful control of process parameters. By precisely controlling the deposition time, the resulted different thickness of TiO2 sheaths lead to the formation of nanotubes or nanorods. In addition, Yuan et al. successfully developed TiO2 nanotube arrays through an anodic aluminium oxide (AAO) template‐based Ti(OC4H9)4 hydrolysis process (Figure 9d–f).164 In the synthesis process, two kinds of solutions in either half of the U‐tube are allowed to diffuse across the holes of the AAO membrane and then react through hydrolysis or precipitation at the interface. By carefully controlling the molar concentrations of Ti(OC4H9)4, TiO2 nanotube arrays can be obtained.

Figure 9.

Schematic of the steps for forming the end‐closed TiO2 nanotube using positive template (a). TEM images of ZnO nanorods (b), TiO2 nanotubes (c), and their associated selected area electron diffraction patterns. Schematic diagram of the experimental device composed of two half U‐tube cells separated by an AAO membrane (d), the typical surface and section SEM images of AAO (e), and SEM images of TiO2 nanotubes prepared with Ti(OC4H9)4 solution in half‐cell B (f).(a–c) Reproduced with permission.163 Copyright 2005, Royal Society of Chemistry. (d–f) Reproduced with permission.164 Copyright 2013, Royal Society of Chemistry.

The first report on preparation of TiO2 nanotubes using template‐assisted method was by Hoyer et al. in 1996.165 In their work, TiO2 nanotubes were formed by electrochemical deposition into polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA) which was produced by porous AAO membrane. Zinc oxide (ZnO) nanostructure was commonly employed as a template due to its low cost and easy fabrication, and it can be easily dissolved in mild acids. As described before, Lee et al. also demonstrated that the removal of ZnO nanorod template when prepared TiO2 nanotubes could even be achieved by the reaction with hydrogen ions during liquid phase deposition process.163 Besides, carbon nanotubes have been considered to be an ideal template due to its small diameter, easy removal and self‐supported tubular morphology.166

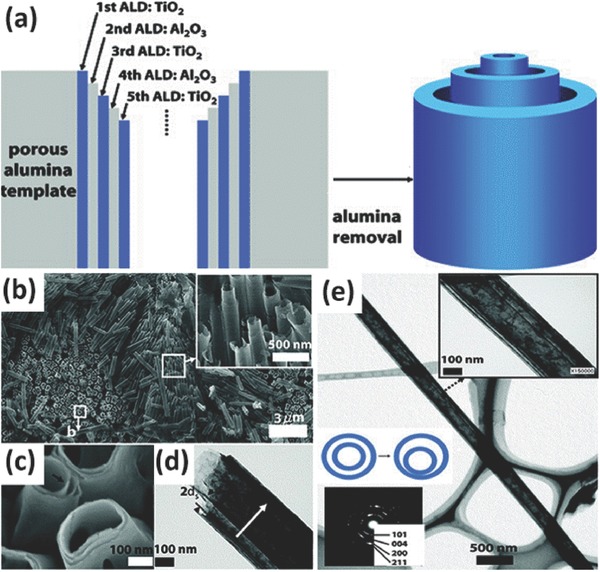

In a typical template preparation process, TiO2 sol–gel is prepared by mixing tetrabutyl titanate or titanium isopropoxide in acetic acid in the presence of templating agents. Then the polymerization of TiO2 in the templates or deposition of TiO2 onto the surface of the template aggregates occurrs. Finally, selectively removal of the templating agent and calcination of the resultants are needed.167 In addition, atomic layer deposition (ALD) combined template is also a good method to prepare TiO2 nanomaterials with certain structures. Bae et al. successfully fabricated multi‐walled anatase TiO2 nanotubes by alternating TiO2 and aluminium oxide onto porous aluminium oxide templates with ALD method, followed by etching of the sacrificial aluminium oxide (Figure 10 ). The diameter, length, wall thickness, and wall layers of the multi‐walled TiO2 nanotubes can be easily adjusted.168

Figure 10.

Schematic illustration of process to fabricate multiwall anatase TiO2 nanotubes using negative template (a). SEM image of triple‐wall TiO2 NTAs and sacrificial Al2O3 layers (b), and the broken ends of triple‐wall NTAs (c). TEM of a sextuple‐wall TiO2 NTAs (d). TEM image of long quintuple‐wall NTs: the left inset is a representative electron diffraction pattern, and the right inset shows the separated TiO2 walls (e). Reproduced with permission.168 Copyright 2009, American Chemical Society.

However, there are also many disadvantages which cannot be ignored about the templated method. As can be seen from the preparation process, the used template needs to be removed after synthesis in most cases, which generates waste and adds to the cost of material processing. The dissolution process may have the risk of destroying the formed TiO2 nanostructures. Besides, it requires tedious steps including pre‐fabrication template and post‐removal of template, which are time consuming and laborious for the practical applications. Moreover, the size and morphology varieties of templates are limited. In this regard, template method may not be suitable for large scale TiO2 nanotube preparation.

4. Surface Engineering Strategy

TiO2 nanostructured materials are widely used in photocatalysis, dye‐sensitized solar cells, water splitting, lithium‐ion batteries and biomedical devices due to its low‐cost, good physical and chemical properties. As an ideal photocatalytic material, it must possess a sufficiently large specific surface area, high light absorption efficiency over a broad light absorption spectrum, as well as effective separation of the photo‐induced electron/hole pairs.169 However, associated with the width of energy band gap (anatase: 3.2 eV, rutile: 3.0 eV), TiO2 can only absorb ultraviolet light (3–5% solar light), leaving the abundant visible light from the Sun unutilized. In addition, the recombination of electron/holes is very fast, and all these disadvantages largely limit the wide applications of TiO2 for solar energy applications. Especially for the anodized TiO2 nanotube arrays, they have lower specific surface area and unconformable surface compared to TiO2 nanoparticles. TiO2 nanotubes synthesized by hydrothermal method are usually unfavorable for good contact with reactants in rigorous conditions. Therefore, it is of great importance to overcome these drawbacks to improve power conversion efficiency and photo/photoelectro‐catalytic efficiencies. Over the past decades, considerable efforts have been put into extending the light absorption, enlarging surface area and suppressing combination of electron/holes.170, 171, 172, 173, 174

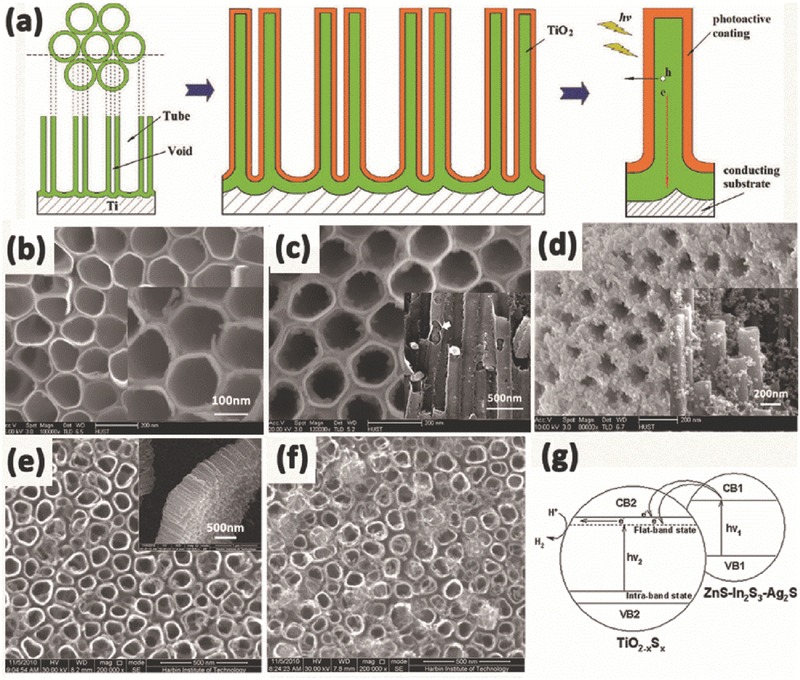

4.1. Enlargement of the Photocatalytically Active Surface

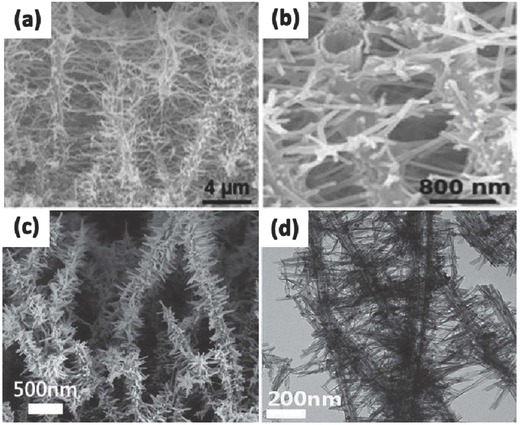

It is noted the photocatalysis of 1D TiO2 for degradation of organic molecules or water‐splitting only occur on the surface where contains enough photocatalytically active sites. Therefore, the specific surface area and the active site concentration of a photocatalyst must be taken into account for the design and synthesis of a 1D TiO2 nanotubes for use in photocatalytic applications. Compared with TiO2 nanoparticles, the 1D TiO2 nanostructure has lower specific surface area and lower photocatalytic performance. To enlarge the specific surface area, there are two effective methods in general: (1) decorating second phase materials such as nanoparticles, nanorods or nanowires on the surface of the 1D TiO2 nanostructure; (2) constructing a coarse surface with numerous uniformly distributed nanoparticles using an acid corrosion process. Though the size, distribution and density of the loaded nanomaterials on the 1D TiO2 nanotubes are difficult to control, both approaches greatly improve its photocatalytic activity. On the one hand, the surface area is significantly increased due to the large specific surface area of the nanoparticles on the surface; on the other hand, nanomaterials on the 1D TiO2 nanostructure surface form surface heterostructures, which enhances the separation of photo‐induced charge carriers and holes. By using TiO2 nanotubes as backbones, branched double‐shelled TiO2 nanotubes can be synthesized on fluorine doped tin oxide (FTO) substrates via ZnO nanorod array template‐assisted method (Figure 11 a,b).161 The ZnO templates were removed by using wet chemical etching in 0.015 M TiCl4 aqueous solution for 1.5 h at room temperature. The branched nanotubes have good power conversion efficiency resulted from the increased surface area and the dye loading due to the radial TiO2 branches with a small diameter. In addition, Roh et al. prepared hierarchical pine tree‐like TiO2 nanotube arrays consisting of a vertically oriented long nanotube stem and a large number of short nanorod branches with an anatase phase directly grown on an FTO substrate via a one‐step hydrothermal process (Figure 11c,d).175 The morphologies of pine tree‐like TiO2 nanotube can be controlled by adjusting the water/diethylene glycol ratio. Owing to the larger surface area, improved electron transport and reduced electrolyte/electrode interfacial resistance from the pine tree‐like TiO2 nanotube arrays, the assembled dye‐sensitized solar cells exhibited a superior power conversion efficiency of 8.0%.

Figure 11.

SEM images of branched double‐shelled TiO2 nanotubes in low (a) and high resolution (b). SEM image of hierarchical pine tree‐like TiO2 nanotube array (c) and its TEM image (d). (a,b) Reproduced with permission.161 Copyright 2012, Royal Society of Chemistry.(c,d) Reproduced with permission.175

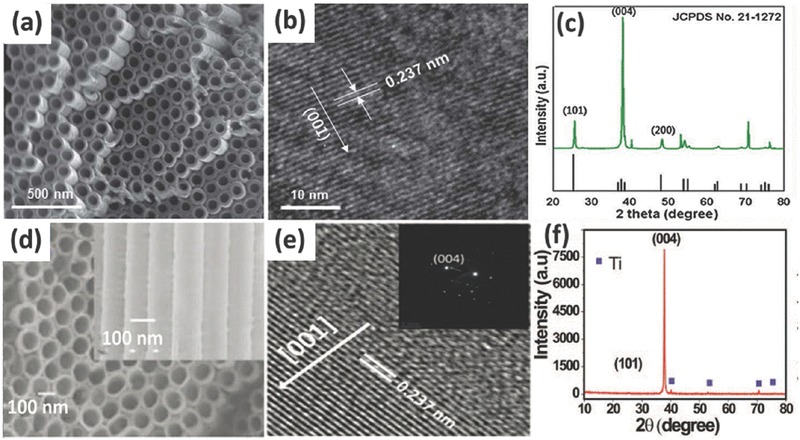

In addition, the chemical activity of anatase TiO2 is closely related to its different facets which are determined by the surface energy. It is reported that the surface formation energies of TiO2 facets are 0.90 J m–2 for the (001), 0.53 J m–2 for the (100) and 0.44 J m–2 for the (101).176 The (001) facet possesses the highest surface energy due to the coordinatively unsaturated Ti and O atoms on (001) and very large Ti–O–Ti bond angles,177, 178 but it is difficult to prepare exposed (001) facets in TiO2 nanostructures due to the reduced stability, or the proposed synthesis method is time‐consuming with high cost and low efficiency. Recently, Lu et al. made great progress in the preparation of anatase TiO2 with exposed (001) facets using TiF4 as the raw material via the hydrothermal method.179 Inspired by this, many efforts have been put on preparing anatase TiO2 with exposed (001) facets from different starting chemicals since then.180, 181, 182 Jung et al. synthesized single‐crystal‐like anatase TiO2 nanotube with a mainly exposed and chemically active (001) facet relied on an oriented attachment mechanism using surfactant‐assisted processes with poly (vinyl pyrrolidone) (PVP) and acetic acid (Figure 12 a–c).183 The PVP in electrolyte was preferentially adsorbed onto the (101) surfaces, and then the growth of the (001) facets proceeded more quickly, leading to single‐crystal‐like anatase TiO2 with mainly the (001) plane. Such highly exposed (001) facets have shown high efficiency in retarding the occurrence of charge recombination in dye sensitized solar cells, and led to enhanced conversion efficiency. Recently, John et al. fabricated single crystal like TiO2 nanotubes oriented along the (001) direction with improved electronic transport property.184 The tubes were synthesised by a two‐stage technique: in the first stage, well‐aligned and uniform amorphous TiO2 nanotubes were fabricated on a titanium foil by electrochemical anodization technique; the second stage consists of zinc assisted preferential orientation of grains in the nanotubes. In this stage, Zn incorporation in the amorphous nanotubes is done in a three electrode system by applying a negative voltage to TiO2 nanotubes with ZnSO4 solution as the electrolyte. After annealing, the surface deposited oxidized zinc was removed by dipping the tubes in HCl solution; finally (001) orientated single crystal like nanotubes were obtained (Figure 12d–f). The success of this method to grow the nanotubes with the intense (001) preferential orientation could be attributed to the zinc assisted minimization of the (001) surface energy. The single crystal like TiO2 nanotubes shown superior electrochemical performance as supercapacitor electrodes.

Figure 12.

SEM (a) and TEM (b) images of a TiO2 nanotube array. XRD patterns of TiO2 nanotubes after annealing (c). SEM image (d), high resolution TEM image (e) and XRD image (f) of single crystal like Zn‐incorporated TiO2 nanotubes representatively. (a–c) Reproduced with permission.183 Copyright 2012, Royal Society of Chemistry. (d–f) Reproduced with permission.184 Copyright 2015, Royal Society of Chemistry.

4.2. Broadening of Light Absorption

TiO2 has a wide band gap of about 3.2 eV and can only absorb UV light, which only makes up 3–5% of solar light.181, 185 This intrinsic drawback largely limits the harvesting of solar light. Thus it is of great importance to enhance the absorption of the 1D TiO2 nanostructure by enhancement of light harvesting or broadening the light absorption from UV light to the visible light range.

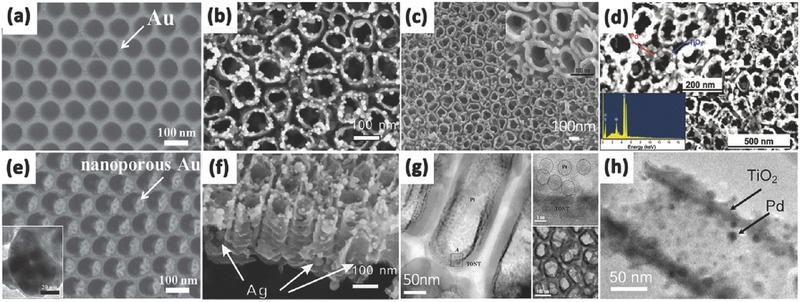

Enhancing the light absorption ability is usually realized by utilizing the surface plasmon resonance (SPR) effect of metallic nanoparticles assembled on the surface of the 1D TiO2 nanostructure. The decorating materials used mainly focused on various noble metals (Au, Ag, Pt, Pd or alloys) because they can be optically excited in the visible region.186, 187, 188, 189, 190 The modification with noble metals can also restrain the recombination of electron/hole pairs and enhance photo/photoelectro‐catalytic activity. Upon visible light illumination, the noble metal nanoparticles could be photo‐excited and generate electrons on its surface due to the SPR effect. Moreover, SPR can improve solar light conversion because of enhanced light absorption and scattering at the interface of the heterostructure and induce direct electron‐hole separation as well as plasmonic energy‐induced electron‐hole separation. All of these processes can greatly increase solar light conversion efficiency.191, 192, 193, 194, 195 Strategies used for decorating 1D TiO2 nanomaterials with noble metal nanoparticles always include UV irradiation reduction, plasma sputtering, electrodeposition, electrospinning and hydrothermal methods, among which the hydrothermal method has been most widely used due to its better control of the metal particle size and dispersion. Wu et al. constructed highly dispersed Au nanoparticles on the TiO2 nanotube arrays by the electrodeposition method, and the composite Au/TiO2 NTAs showed much higher photocatalytic degradation of methyl orange (MO) under visible light.196 Nguyen et al. demonstrated a novel method for fabricating a photocatalytic platform consisting of anodic TiO2 nanotubes supporting arrays of highly ordered porous Au nanoparticles (Figure 13 a,e).187 This approach used highly ordered‐TiO2 nanotubes as a morphological guide for an optimized sputtering‐dewetting‐dealloying sequential approach of a co‐catalyst layer. The metal nanoparticle size, shape, and distribution were controlled uniformly and the final nanoporous Au/TiO2 nanostructures showed an enhanced photocatalytic hydrogen production from ethanol/water mixtures. Similarly, Yin et al. uniformly deposited Au nanoparticles on the surface of highly ordered TiO2 nanotube arrays through anodization and microwave‐assisted chemical reduction route.197 The composite Au/TiO2 nanotubes exhibited excellent visible light absorption due to the localized SPR effect of Au nanoparticles. Typically, the synergistic effect between nanotubular structures of TiO2 and Au nanoparticles, as well as the small bias potential and strong interaction between Au and TiO2, facilitated the Au plasmon‐induced charge separation and transfer, which lead to highly efficient and stable photoelectrocatalytic activity. Xie et al. constructed highly dispersed Ag nanoparticles on TiO2 nanotube arrays by pulse current deposition (Figure 13b,f).198 The Ag/TiO2 nanotube arrays exhibited higher photocatalytic activities than the pure TiO2 nanotube arrays under both UV and visible light irradiation. Lee and his colleague synthesized Pt/TiO2 nanotube catalysts by two different deposition methods of sputtering and evaporation (Figure 13c,g).199 It is evident that Pt particles are deposited preferentially to the open top end of the TiO2 by sputtering, which results in a more conformal coating than evaporation. The Pt deposited on the nanotubes enhanced the rate of oxygen reduction reaction and it is promising for fuel cell applications. Similarly, Mohapatra et al. prepared vertically oriented TiO2 nanotube arrays functionalized with Pd nanoparticles of ∼10 nm size.200 The Pd nanoparticles distributed uniformly throughout the TiO2 nanotubular surface by a simple incipient wetness method (Figure 13d,h). This functionalized material was found to be an excellent heterogeneous photocatalyst for rapid and efficient decomposition of non‐biodegradable azo dyes (e.g., methyl red and methyl orange) under solar light.

Figure 13.

TiO2 nanotubes after 10 nm Au sputtering (a) and porous Au nanoparticle after dealloying in HNO3 (e). Top view (b) and cross‐sectional (f) SEM images of TiO2 nanotube arrays obtained under pulse current deposition. SEM (c) and TEM (g) images of Pt sputtered on TiO2 nanotube arrays. SEM (inset shows the EDX spectrum of the Pd/TiO2 surface) (d) and TEM (h) image of Pd nanoparticle‐functionalized TiO2 nanotube.(a,e) Reproduced with permission.187 (b,f) Reproduced with permission.198 Copyright 2010, Elsevier. (c,g) Reproduced with permission.199 Copyright 2008, The Electrochemical Society.(d,h) Reproduced with permission.200 Copyright 2008, American Chemical Society.

It is noted that loading of metallic particles should be controlled carefully. If the amount is excessively high, the channels of TiO2 nanotubes could be partially blocked, leading to the decrease in the photo/photoelectro‐catalytic activity.

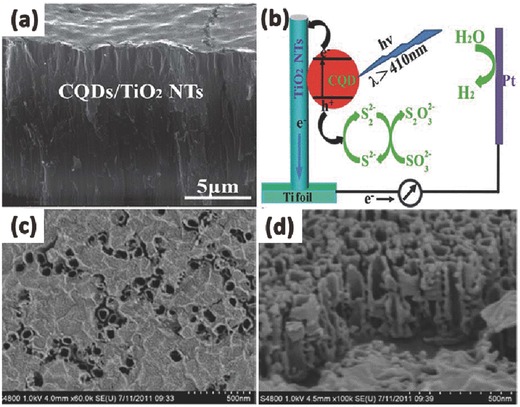

At the same time, broadening the photocatalytically active wavelength region to visible light is also one of the most important design principles for fabricating improved 1D TiO2 nanotubes. Tuning the physical and chemical properties of the TiO2 and constructing surface heterostructures by semiconductor materials are good choices. By modifying the high UV photocatalytic properties of TiO2 with the visible photocatalytic properties of semiconductor nanoparticles or specially shaped noble metal nanoparticles with a narrower band gap, an active light wavelength broadened photocatalyst can be achieved. Besides, except for UV light and visible light, infrared light comprises more than 50% of solar light energy. Thus making use of infrared light would have great potential for photocatalysis or water splitting for hydrogen generation. An important approach for assembly of TiO2 nanostructures with visible‐infrared light photocatalytic activity is to decorating TiO2 with specific materials containing d‐block or f‐block elements (such as Yb3+, Er3+, etc.), carbon or graphene quantum dots which absorbed long wavelength light and converted to shorter wavelengths that lie within the visible and UV regions.201, 202 TiO2 nanotubes can easily obtain high photocatalytic performance under near‐infrared light irradiation by assembling these up‐conversion nanoparticles. Since graphene or carbon quantum dots can convert infrared light to visible light, and then to UV light, it is also promising to use these newly emerging material to improve the photocatalytic properties of TiO2.203, 204 Zhang et al. fabricated TiO2 nanotube arrays loaded with carbon quantum dots (CQD) by electrodeposition (Figure 14 a).205 The excited electrons from the CQDs transferred to the conduction band of the TiO2 nanotubes in contact, and then transported to the counter electrode for the hydrogen evolution reaction (Figure 14b). The CQDs that were electrodeposited on the TiO2 nanotubes can significantly broaden the photoresponse range to the visible and NIR regions. As a result, the enhanced optical absorption can effectively improve the light‐to‐electricity efficiency for hydrogen generation. Song et al. developed a hybrid material composed of graphene oxide (GO) network on the surface of TiO2 nanotube arrays by a simple impregnation method.206 After a simple assembly process in the GO suspension, a sheet of GO coated the most surface of the TiO2 nanotube arrays (Figure 14c,d). The obtained GO modified TiO2 nanotube arrays showed a 15 times increase in the photoconversion efficiency (η) compared with pristine TiO2 under visible light illumination. The use of carbon and graphene quantum dots is cost‐effective, environmentally friendly, and thus promising to combine with TiO2 for the utilization of visible light under ambient conditions.

Figure 14.

SEM images (a) of TiO2 nanotubes after CQD deposition. (b) The schematic diagram of the sensitization mechanism of the CQDs deposited on the surface TiO2 nanotubes. The top (c) and cross‐section (d) of GO/TiO2 composite nanotube arrays. (a,b) Reproduced with permission.205 Copyright 2013, Royal Society of Chemistry. (c,d) Reproduced with permission.206 Copyright 2012, Royal Society of Chemistry.

4.3. Suppression of Charge Carrier Recombination

The photocatalytic capacity of TiO2 mainly originates from photo‐induced charge carriers, while the charge carriers are governed by the excitation of electrons from the valence band to the conduction band, the diffusion of charge carriers and their recombination/separation that occurs at the surface or in the bulk.169 Thus to improve photo/electro‐catalytic water splitting efficiency, attention should be put not only on the increase of photo‐generated charge carriers by enhancement or extension of light absorption, but also on how to prohibit the recombination of these carriers.

4.3.1. Heterojunction

When the TiO2 is coupled with SPR metal particles, electrons excited in the conduction band can escape from the plasmonic nanostructures and transfer to a contacted semiconductor, thereby forming a metal‐semiconductor Schottky junction.207, 208 These semiconductors have a great effect on the charge injection efficiency under suitable conditions. And photo‐induced charge carriers in the semiconductor can accumulate at the interface or flow into the metal leaving holes in the valence band of the semiconductor, then the charge carriers are significantly separated.

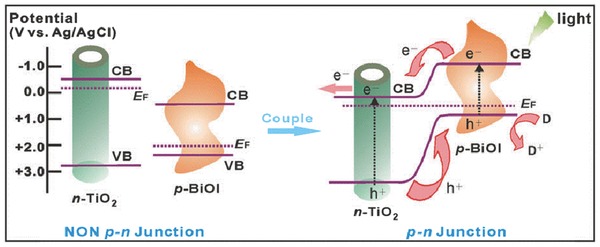

Another important principle for 1D TiO2 nanotubes to improve photo‐induced carrier separation is to form p‐n junction between the surface nanoparticles and the 1D TiO2 substrate. Since TiO2 is an n‐type semiconductor, it would be one of the most effective strategies to construct a p‐n junction with another p‐type semiconductor due to the existence of an internal electric field at the interface.209, 210, 211, 212 When a p‐n junction is constructed, the formed local electric field drive the photo‐generated electrons move to the n‐type semiconductor side, and holes to the p‐type semiconductor side (Figure 15 ).213 At the same time, the charge carriers can diffuse into the space charge region. As a result, the separation of photo‐induced electron‐hole pairs can be effectively realized, leading to enhanced photo/photoelectro‐catalytic activity.

Figure 15.

Schematic diagrams for the energy bands of p‐type BiOI and n‐type TiO2 before and after coupling, as well as the specific charge transfer process at the formed p‐n junction under visible‐light irradiation. Reproduced with permission.213 Copyright 2014, Nature Publishing Group.

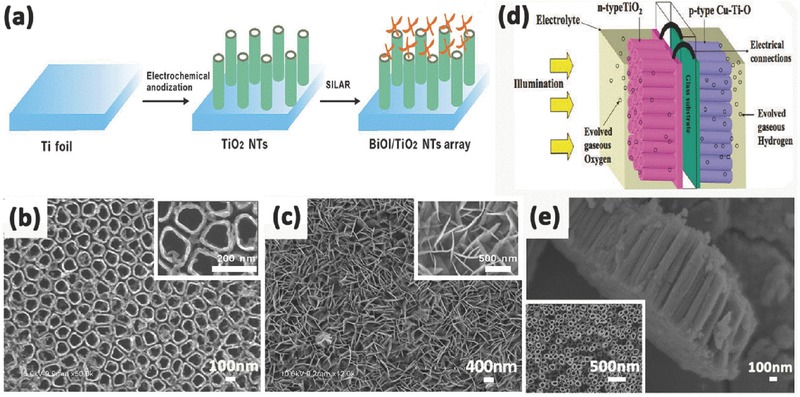

Liu et al. successfully decorated the n‐type TiO2 with p‐type BiOI by immersing annealed TiO2 NTAs into Bi(NO3)3·5H2O and NaI, respectively.214 The BiOI nanoflakes grow perpendicular to the wall of nanotubes, which is beneficial for the increase in the specific surface area. And they loaded on both the outer and inner walls of TiO2 nanotubes, acting as the light‐transfer paths for distribution of the photo energy onto the deeper surfaces. Furthermore, the internal electric field caused by p‐n BiOI/TiO2 heterojunction effectively prevented the recombination of electrons and holes. Accordingly, the BiOI/TiO2 NTAs exhibited a more effective photo‐conversion efficiency than single TiO2 nanotubes under visible light irradiation. Zhao et al. used the p‐n heterojunction comprised of p‐type BiOI nanoflakes array and n‐type TiO2 nanotubes array fabricated by successive ionic layer adsorption and reaction (SILAR) (Figure 16 a) for the detection of cancer biomarker vascular endothelial growth factor.213 The crossed BiOI nanoflakes on perpendicularly aligned and highly ordered TiO2 nanotubes possessed unique layered structures (Figure 16b,c). Specifically, charge separation could occur simultaneously both in BiOI nanoflakes and TiO2 NTAs. Then, the photoelectrons of p‐type BiOI would promptly inject into the conuction of n‐type TiO2, while the holes of latter would transfer to the valence band of the former. These injected electrons on the conduction band of TiO2 NTAs were then rapidly collected by the Ti substrate as photocurrent due to the efficient charge transport within the arrayed tubes. The synergistic effect of these factors could substantially promote the spatial charge separation and the subsequent migration of these carriers, impeding the charge recombination and thus improving the excitation and conversion efficiency. Mor et al. fabricated vertically oriented p‐type Cu–Ti–O nanotube array films by anodization of copper rich (60% to 74%) Ti metal films co‐sputtered onto FTO coated glass (Figure 16e).215 In combination with n‐type TiO2 nanotube array films, p/n‐junction photochemical diodes capable of generating a chemical fuel were formed (Figure 16d) with a photocurrent of approximately 0.25 mA cm2, at a photoconversion efficiency of 0.30%.

Figure 16.

Schematic illustration for fabricating crossed BiOI nanoflakes/TiO2 nanotubes arrayed structure (a). SEM image of the self‐organized TiO2 nanotubes (b) and 3D interlaced network of BiOI layer on TiO2 nanotubes (c). Illustration of photoelectrochemical diode for water splitting comprised of n‐type TiO2 and p‐type Cu–Ti–O nanotube array films, with their substrates connected through an ohmic contact (d), lateral and top view FESEM images of Cu–Ti–O nanotube array (e). (a–c) Reproduced with permission.213 Copyright 2014, Nature Publishing Group. (d,e) Reproduced with permission.215 Copyright 2008, American Chemical Society.

Some ternary metal oxides with the perovskite structure such as SrTiO3, CaTiO3, BaTiO3, MgTiO3, etc., have been found to be catalytically active and can be potentially used in photocatalysis by forming TiO2 heterostructures.48, 216, 217, 218, 219 Of particular interest, SrTiO3 has attracted much interest for water splitting due to its high corrosion resistance and excellent photocatalytic activity. Furthermore, SrTiO3 possesses only a 200 mV conduction band edge, which is more negative than TiO2, thus it makes SrTiO3 a good candidate for coupling TiO2 and improving photoelectrochemical properties by shifting the Fermi level of the composite to more negative potentials.220 In 2009, Zhang et al. tailored TiO2–SrTiO3 heterostructure nanotube arrays by converting electrochemical anodized TiO2 nanotube arrays into TiO2–SrTiO3 heterostructures through controlled substitution of Sr under hydrothermal conditions (Figure 17 a,b).220 The photoelectrochemical performance of such a vertically aligned heterostructure array is strongly dependent on its composition and morphology. At the hydrothermal reaction time equal to 1 h, nanoparticles with a diameter of approximately 50 nm start to form on the surface of TiO2 nanotubes. In this condition the TiO2 nanotube electrodes exhibited greater photocurrent than other composite TiO2 nanotubes with longer reacting time. Only well‐dispersed SrTiO3 nanocrystallites on TiO2 nanotube arrays can efficiently cause the Fermi level to equilibrate and reduce the recombination of charge carriers at the surface of the heterostructure, and finally improve the overall photoelectrochemical performance. This work provides a convenient way to tailor the photoelectrochemical properties of TiO2–SrTiO3 nanotube arrays and employ them for dye‐sensitized solar cells or photocatalytic hydrogen production. In 2011, Hamedani et al. reported highly ordered Sr‐doped TiO2 nanotube arrays synthesized via a one‐step electrochemical anodization technique (Figure 17c,d).221 The morphology and quality of the fabricated materials were highly related to the pH of the electrolyte and the solubility limit of Sr(OH)2 in the electrolyte. Moreover, Sr doping of TiO2 nanotubes showed a red shift in the absorption edge, which resulted in an electrode photoconversion efficiency of 0.69%, more than 3 times higher than that of the undoped nanotube arrays (0.2%) under the same conditions. Additionally, metallic elements such as Nb, Cr are usually doped into TiO2/SrTiO3 nanotubular heterostructures to enhance their photoelectrocatalytic activities.222, 223 For example in the SrTiO3/TiO2 composites, the electrons of pure SrTiO3 can only be excited from the valence band (O 2p) to the conduction band (Ti 3d) by photons with energy greater than 3.2 eV. While in Cr‐doped SrTiO3, a Cr 3d level appears within the forbidden gap, and the mixing of the Cr 3d with the Ti 3d level slightly lowers the conduction band, which effectively narrows the bandgap of SrTiO3. So electrons can directly transit from the newly formed dopant states (Cr 3d) to the conduction band (Ti 3d and Cr 3d). In this way the visible‐light response of SrTiO3/TiO2 heterostructures can be greatly improved by the partial substitution of Cr3+ for Sr2+ cations in the SrTiO3 (Figure 17e,f).223

Figure 17.

SEM and TEM (insets) images of (a) TiO2 nanotube array after annealing at 450 °C and (b) TiO2–SrTiO3 hybrid nanostructures obtained after 1 h hydrothermal treatment. Top‐view and bottom‐view (inset) images of Sr‐doped TiO2 nanotubes (c) and its corresponding cross‐sectional views in 0.04 M dopant concentration at pH = 3 (d). SEM images (e) and schematic illustration (f) of charge separation and transport of heterostructured Cr‐doped SrTiO3 nanocube/TiO2 nanotube array heterostructures. (a,b) Reproduced with permission.220 Copyright 2009, American Chemical Society. (c,d) Reproduced with permission.221 Copyright 2011, American Chemical Society. (e,f) Reproduced with permission.223

4.3.2. Band Structure Engineering

A good matching of the conduction and valence bands of two semiconductors enables efficient charge carrier transfer from one to another.224 It is reported that wide band gap energy of TiO2 nanotubes coupled with small band gap semiconductor could result in the formation of heterojunctions, which simultaneous enhances visible light harvest and charge separation.225, 226

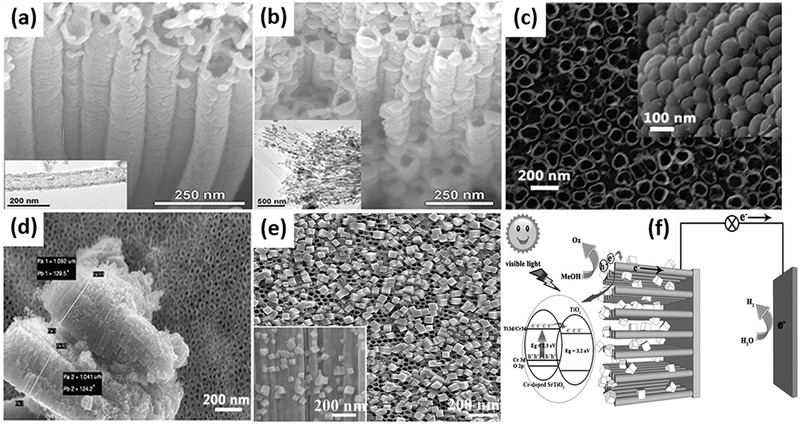

The modification of TiO2 nanotubes with quantum dots with narrow band gap is a promising approach since it can improve the photocatalytic activity effectively. Cadmium sulfide (CdS) is a well‐known semiconductor and widely used to modify TiO2 materials. CdS has a narrow band gap of 2.4 eV, which matches well with the spectrum of sunlight and allows CdS to act as photo‐sensitizer to absorb visible light. The combination of CdS and TiO2 can be achieved by electrochemical deposition and sequential chemical bath deposition. In a typical synthesis procedure, dipping the prepared TiO2 nanotube arrays film into the precursor solution containing Cd2+ for several minutes and dried at 60 °C in air are needed first. Then them are placed into the precursor solution of S2– followed by treatment with electrochemical deposition or sequential chemical bath deposition. Usually the two steps are repeated several times to realize a total deposition. And finally the mixtures are heated at 450 °C for 2 h in a nitrogen atmosphere.227, 228 Zhu et al. reported the coaxial heterogeneous composite material formed from self‐assembled TiO2 nanotubes and the narrow‐band‐gap compound semiconductor CdS using the electrochemical ALD technique (Figure 18 a).229 The modified electrochemical ALD technique produced uniform thin films of narrow‐band‐gap compound semiconductors coating onto large‐surface‐area nanostructured substrates in various deposition potentials (Figure 18b–d). These coaxial heterogeneous structures enhanced CdS/TiO2 and CdS/electrolyte contact areas and reduced the distance of holes and electrons to the electrolyte or underlying conducting substrate. This results in enhanced photon absorption and photocurrent generation, which are favorable for water photoelectrolysis and toxic pollutant photocatalytic degradation. By using a small applied potential and white light, CdS‐coated TiO2 nanotube arrays could totally inactivate bacteria in very short time due to the enhanced generation of OH• radicals and with H+, which has great potential in wastewater treatment.230 It has been proven that TiO2 nanotubes have directionality benefits in oriented arrays through improvements in electron mobility and separation of charges, but the accessiblity of two sides for illumination is still limited when directly used for solar cell.231, 232 Thus the detachment and reassembly of TiO2 nanotubes on another conducting surface are necessary. In order to deal with such problem and assess the behavior of randomly structured nanotubes versus oriented nanotubes, David et al. conducted a photoelectrochemical study by modifying each of these systems with CdS.233 They removed etched TiO2 nanotubes from the titanium foil substrate by sonication and reassembled them onto new electrodes. The random nanotube structures can directly transfer electrons conducting substrate without a barrier layer and have a higher intertube porosity, providing additional space for the electrolyte solution, which allows for faster mass transfer of the redox couple. The photoelectrochemical results of these reassembled TiO2–CdS electrodes showed a slight decrease in photocurrent response but a small increase in photopotential as compared to oriented TiO2–CdS electrodes. Reconstruction of the nanotubes onto new substrates does not significantly reduce the benefits of the one dimensional TiO2 nanostructure, and it creates opportunities for various critical applications.

Figure 18.

Schematic of narrow‐band‐gap semiconductor/TiO2 nanotube coaxial heterogeneous structural design (a). Top‐surface FE‐SEM and enlarged (inset) images of CdS electrodeposited onto TiO2 nanotube arrays at –0.65 V (b), –0.70 V (c) and –0.75 V (d) (vs Ag/AgCl) representatively. SEM images of TiO2 nanotubes (e) and ZnS–In2S3–Ag2S@TiO2 nanotubes (f). The band structures and the mechanism of electron transport for ZnS–In2S3–Ag2S solid solution coupled with TiO2–xSx nanotubes film catalyst (g). (a–d) Reproduced with permission.229 Copyright 2010, American Chemical Society. (e–g) Reproduced with permission.234 Copyright 2012, Elsevier.

Besides CdS quantum dot, Jia et al. successfully prepared ZnS–In2S3–Ag2S solid solution coupled with TiO2–xSx nanotubes film catalyst by a two‐step process of anodization and solvothermal methods.234 After sovolthermal treatment, the TiO2 nanotubes still kept their tube‐like structures, and the needle‐like ZnS–In2S3–Ag2S nanorods deposited on the most part of the surface of TiO2 nanotubes (Figure 18e,f). Typically, the doping of multiple elements could modify the band structure, narrowing the band gap of TiO2 and inducing visible light absorption at the sub‐band‐gap energies (Figure 18g). Such ZnS–In2S3–Ag2S@TiO2–xSx nanotubes composite presents the enhanced absorption in visible region and the efficient transfer of photoelectron between the solid solution and TiO2–xSx nanotubes, which leads to the excellent photocatalytic activity for the photocatalytic hydrogen evolution from aqueous solutions.

It is noted that the band gap of TiO2 can be narrowed by non‐metal ion doping via using anions such as N, C, B, F, P, S and I etc.235, 236, 237, 238 The commonly used methods to prepare doped TiO2 nanostructures are: thermal treatments or synthesis of TiO2 NTAs in certain gas atmospheres such as N2, CO, Ar, etc.; co‐sputtering or sputtering with doping materials; ion implantation and electrochemical oxidation.147 Thermal treatment in gas atmospheres of the doping species is frequently used for nitrogen or carbon doping. Ion implantation and electrochemical oxidation are recognized as facile doping means to incorporate nitrogen‐containing species into the TiO2 lattice. However, the sputtering and ion implantation need high energy accelerators in high operating voltage, and the implantation depth is only several micrometers, which lead to inhomogeneous dopant distribution. Among all the nonmetal doped TiO2, N‐ and C‐ doped TiO2 are the most successful approaches and have been most widely studied. And combing with the intrinsic defects of TiO2, such as reduced Ti species and oxygen vacancies, the formation of localized states which may merge to form sub‐band gap level and thus creating a lower energy excitation pathway.105 Recently, Su et al. synthesized a graphitic carbon nitride quantum dots (CNQDs) modified TiO2 nanotube arrays (NTAs) photoelectrode by electrochemical anodization technique and a followed organic molecular linkage using bifunctional organic molecule as an effective linker.239 The modification of TiO2 by CNQDs showed a significant improvement in the photoelectrochemical activity owing to enhanced light absorption and improved photo‐generated electron‐hole pairs separation. Upon solar light irradiation, photo‐generated holes and electrons are generated in the valence band (VB) and conduction band (CB) of TiO2 and CNQDs, respectively. These electrons in CB of CNQDs can transfer easily to the CB of TiO2 due to the band alignment and potential difference, and they finally reach the Ti substrate along the vertical tubular structures, realizing fast charge transfer and separation. Under the electric field, the electrons transfer to the counter electrode to complete hydrogen production. At the same time, the accumulated holes in the VB of CNQDs which come from VB of TiO2 continuely oxidize water to form oxygen. Thus, the photo‐generated electron‐hole pairs are effectively separated, thereby leading to the significantly enhanced photoelectrochemical performance.

5. Application of Photo/photoelectro‐catalytic Water Splitting

With the fast development of economy and increasing depletion of natural fossil fuels, the environmental problems and energy shortage are becoming more and more serious. Human beings have been urgently called up to deal with these problems. As discussed above, TiO2 nanotubes have shown to be an excellent photocatalyst for hydrogen production and decomposition of pollutants due to low‐cost, non‐toxicity, strong redox power, and physical and chemical stability.240, 241, 242

5.1. Photocatalytic Water Splitting for Hydrogen Production

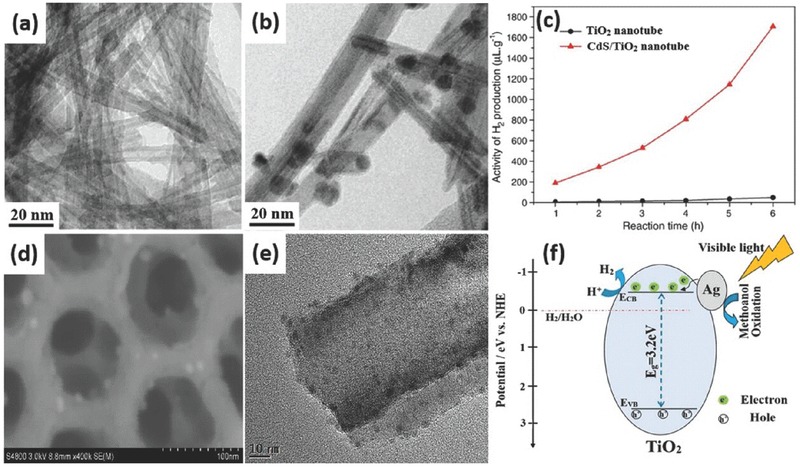

Photocatalysis is the simplest water‐splitting approach, more amenable to cheap, large scale applications of H2 production.243, 244, 245 In general, the hydrogen production rate is greatly depending on the sacrificial agent (methanol, ethanol, KOH etc.), light intensity, and TiO2 morphology and structure.246 D'Elia et al. compared the hydrogen production activity of TiO2 nanotube with TiO2 nanoparticles by using methanol as sacrificial agent. TiO2 nanotube was found to be more active than TiO2 nanoparticles under UV light because of the oriented structure for superior charge transport and lower recombination of electron/hole pairs.247 In addition, Kim et al. and Sun et al. explored the influence of anodization time and annealing temperature of TiO2 nanotube arrays on the photocatalytic water splitting activity, respectively. The results showed that TiO2 NTAs with high ratio of anatase and media tube length displayed higher photocatalytic hydrogen production activity.248, 249 Besides, Xu et al. successfully synthesized 1D mesoporous TiO2 nanotubes with lengths ranging from 100 nm to 400 nm and diameters around 10 nm by a hydrothermal‐calcination process.250 They exhibited excellent photocatalytic activity for simultaneous photocatalytic H2 production and Cu2+ removal from water. However, TiO2 nanotubes still show low photocatalytic hydrogen production activity under visible light due to fast recombination of electron/hole pairs and low utilization of visible light. Therefore, it is essential to increase the surface area or construct heterostructures by modifying TiO2 nanotubes with metal, non‐metal and semiconductors to improve the photocatalytic performances. CdS, a well‐known semiconductor (2.4 eV), which can increase visible light absorption of TiO2 nanotube and facilitate the transfer of the photo‐generated electrons at the interface between CdS and TiO2, is widely used to modify TiO2 nanotubes to improve photocatalytic water splitting activity. Zhang et al. prepared CdS/TiO2 nanotubes composite by a facile chemical bath deposition method (Figure 19 a–c).251 Hexagonal phase CdS nanoparticles with an average particle size of ca. 8 nm were uniformly anchored inside TiO2 nanotubes in average tubular diameter of ca. 15 nm. The absorption edge of TiO2 nanotubes can be extended to visible region by loading with CdS nanoparticles. The CdS/TiO2 nanotubes composite exhibited high activity of hydrogen production (284.7 μL h–1 g–1) in a mixure of Na2S and Na2SO3 solution under visible light irradiation due to the enhanced separation efficiency of photogenerated electron‐hole pair. In addition, noble metal particles such as Au, Ag, Pt etc. are also widely used to decorate TiO2 nanotubes for improving photocatalytic hydrogen production activity because of surface plasmon resonance (SPR) effect for enhanced visible light absorption and suppressed combination of electron/holes.252, 253, 254, 255 Recently, we reported an enhanced hydrogen generation rate of 2 μmol h–1 cm–2 by a two‐step electrochemical anodized TiO2 NTAs with a ordered hexagonal and regular porous top layer.256 Moreover, we found that Ag nanoparticles sensitized TiO2 NTAs by an ultrasonication‐assisted in situ deposition strategy exhibited highly efficient photocatalytic hydrogen production rate of 30 μmol h–1 cm–2 under visible light illumination (15 times over its pristine TiO2 NTA counterpart) (Figure 19d–f). Except for binary, ternary Fe/Ag/TiO2 NTAs, Cu2O/Cu/TiO2 NTAs, CdSe/CdS/TiO2 NTAs structures are widely investigated and they all showed improved photocatalytic water splitting activity under both UV and visible light.257, 258, 259

Figure 19.

TEM images of TiO2 nanotube (a) and CdS/TiO2 nanotube (b), respectively. Activities of H2 evolution for TiO2 nanotube and CdS/nanotube under visible light irradiation for 6 h (c). SEM (d) and TEM (e) image of Ag/TiO2 NTAs, respectively. Schematic diagram showing the energy band structure and electron‐hole pairs separation in Ag/TiO2 NTAs under visible light irradiation (f). (a–c) Reproduced with permission.251 Copyright 2008, Elsevier. (d–f) Reproduced with permission.256 Copyright 2016, Royal Society of Chemistry.

5.2. Photoelectrocatalytic Water Splitting for Hydrogen Production

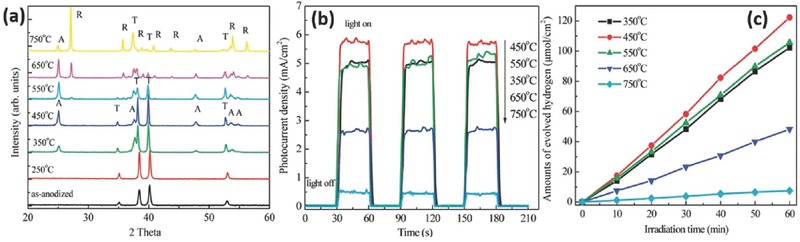

Although intense efforts have been put into photocatalytic water splitting in order to increase hydrogen generation activity, it still faces several challenging issues such as fast recombination of electron/hole pairs, low quantum efficiency in the visible range and solar‐to‐hydrogen (STH) efficiencies less than 0.1%. Photoelectrolysis using photocatalyst electrodes with additional electrical power provided by a photovoltaic element has been proven a facile and promising route to improve the water splitting performance with higher STH efficiency over than 5%.260, 261, 262, 263, 264 Lin et al. obtained an enhanced hydrogen production by photoelectrocatalytic water splitting using extremely highly ordered nanotubular TiO2 arrays with three‐step electrochemical anodization.265 The TiO2 NTAs constructed through the third anodization showed appreciably more regular architecture than that of the sample by conventional single anodization under the same conditions. It was found that the photoelectrocatalytic water splitting for hydrogen evolution rate of the third‐step anodic TiO2 nanotubes was higher than that of single‐step and second‐step anodic TiO2 nanotubes. In addition, Sun's group discussed the effect of annealing temperature on the hydrogen production of ordered TiO2 nanotube arrays, which were synthesized by a rapid anodization process in ethylene glycol electrolyte (Figure 20 ).266 The results indicated that the crystal phase and morphology of TiO2 NTAs had no great changes at low annealing temperatures. Anatase phase and tubular structure of TiO2 NTAs were stable up to 450 °C. With further increase in temperature, the crystallization transformation from anatase to rutile phase appeared, accompanied by the destruction of tubular structures. Due to the excellent crystallization and the maintenance of tubular structures, TiO2 NTAs annealed at 450 °C exhibited the highest photoconversion efficiency of 4.49% and maximum hydrogen production rate of 122 μmol h–1 cm–2, which is consistent with Li's results.267 Besides, Liang's group reported a study to improve the solar water splitting activity of TiO2 photoanodes by tuning the average wall thickness, inner diameter and porosity of the nanotube arrays.268 Further analysis reveals that the photoconversion efficiency increases monotonously with porosity rather than with wall thickness or inner diameter because large porosity can ensure a much shorter hole diffusion path toward wall surface and accelerate ion migration in the tube to overcome the kinetic bottleneck, thus enhancing the photoelectrocatalytic water splitting efficiency.

Figure 20.

X‐ray diffraction patterns (a), transient photocurrent response (b) and comparison of the rates of hydrogen production (c) of TiO2 NTAs annealed at various temperatures ranging from 350 to 750 °C. A, anatase; R, rutile; T, titanium. Reproduced with permission.266 Copyright 2011, American Chemical Society.

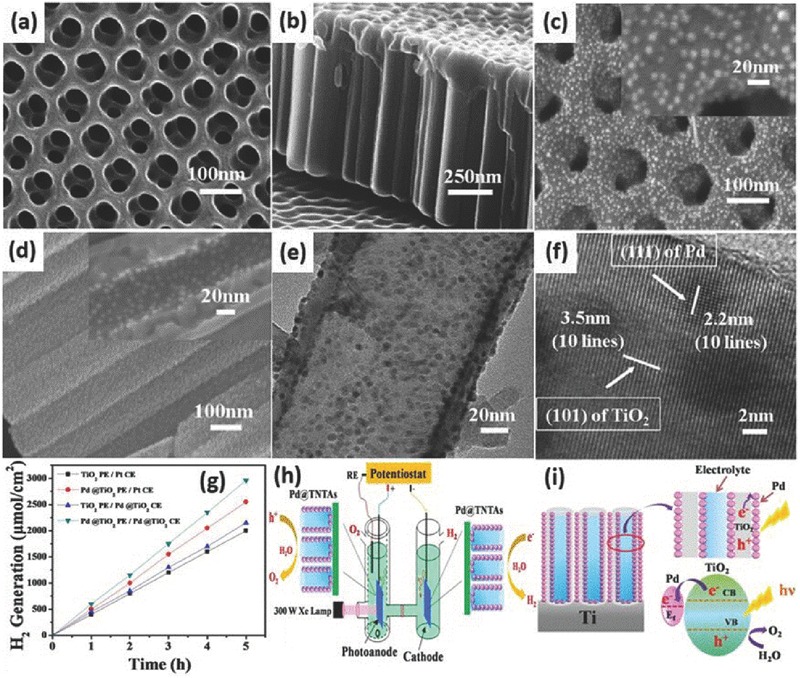

However, pristine TiO2 nanotubes suffer from not only low electrical conductivity, but also fast recombination of electro/hole pairs and weak visible‐light harvest due to the larger band gap, resulting in a low STH conversion efficiency. The band engineering of TiO2 nanotubes by using dye, quantum dot sensitization, chemical doping and narrow gap semiconductor coupling has been proposed to enhance light absorption and obtain a higher STH efficiency.269, 270, 271 Recently, black titania was reported by annealing in the hydrogen atmosphere to boost solar light harvesting impressively for enhanced photocatalytic and photoelectrochemical performances.272, 273 This was attributed to considerable amount of Ti3+ defects and oxygen vacancies introduced into lattice of TiO2 nanotube for expanding visible light absorption, facilitating charge transport and charge separation. In addition, Ye et al. sensitized TiO2 nanotube arrays by palladium quantum dots (Pd QDs) by a facile hydrothermal strategy. As shown in Figure 21 a,b, the nanotube arrays were crack‐free and smooth with an average tube diameter of 80 nm and a wall thickness of 30 nm after a three‐step electrochemical anodization.135 After hydrothermal reaction, Pd QDs were uniformly dispersed over the entire surface of the nanotubes, both inside and outside of the nanotubes with very small particle size of 3.3 ± 0.7 nm (Figure 21c–f). By exploiting Pd@TNTAs nanocomposites as both photoanode and cathode, a substantially increased photon‐to‐current conversion efficiency of nearly 100% at λ = 330 nm and a greatly promoted photocatalytic hydrogen production rate of 592 μmol h–1 cm–2 at –0.3 VSCE in Na2CO3 and ethylene glycol solution under 320 mW cm–2 irradiation were achieved (Figure 21g–i).

Figure 21.