Plants take up inorganic nitrogen (N) primarily as nitrate but also to a lesser extent as ammonium. Nitrate is reduced to nitrite in the cytoplasm by the highly regulated enzyme nitrate reductase. Nitrite is transported into the chloroplast and further reduced by nitrite reductase to ammonium. Ammonium is assimilated into the amino acid pool by the coordinate action of Gln synthetase (GS) and Glu synthase (GOGAT), also known as the GS/GOGAT cycle. Glu dehydrogenase (GDH) resides in the chloroplast and mitochondria. It is thought to function primarily in a catabolic role, and likely only plays a capacity in the assimilation of inorganic N when ammonium concentrations are very high (Melo-Oliveira et al., 1996). The reactions catalyzed by these three enzymes are shown below.

|

|

|

The Glu and Gln derived from the GS/GOGAT reactions function as N donors for the synthesis of most other amino acids and the other major N-containing compounds in the cell, including nucleic acids, cofactors, chlorophyll, and many secondary metabolites. For this reason, Glu and Gln are referred to as the pivotal amino acids. The GS/GOGAT cycle sits at the interface of N and carbon (C) metabolism. Recent work has shown that plant N and C metabolism are tightly coordinated. The coordination of N and C metabolism is required as the assimilation of N demands a C skeleton in the form of 2-oxoglutarate, and considerable ATP and reductant are needed for the reduction of nitrate to ammonium and the incorporation of ammonium into Glu and Gln (Lancien et al., 2000).

Most microorganisms face a similar situation as plants, that is, the assimilation of fluctuating and often-scarce amounts of inorganic N must be precisely coordinated with C metabolism (Ninfa and Atkinson, 2000; Arcondéguy et al., 2001). In all organisms, an appropriate biological response to changing cellular conditions implies the function of two processes, the sensing of cellular status and an adaptive response that signals a coordinated change in the activity of the relevant enzymes and signal transduction proteins. In bacterial C and N metabolism, the PII signal transduction protein performs both the sensing and signaling functions. Bacterial PII protein performs a role likened to a central processing unit to sense and coordinate the cell's response to change in key C and N metabolite levels (Magasanik, 2000).

Genome sequencing has revealed that PII is nearly ubiquitous in the prokaryote world, with the exceptions generally being pathogens (Arcondéguy et al., 2001). Pathogenic microorganisms have evolved to receive their N-containing compounds from their hosts and, therefore, do not need to constantly evaluate their own C and N status. The first eukaryote identified to have a PII-like protein was the red algae Porphyra purpurea (Reith and Munholland, 1995). More recently, PII has been identified in numerous plant species, including Arabidopsis, castor bean (Ricinus communis), rice (Oryza sativa), alfalfa (Medicago sativa), and tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum). This Update will provide a framework for understanding plant PII function by examining what is known about bacterial PII proteins and then discussing recent findings concerning plant PII.

The Discovery of Bacterial PII

The history of PII represents one of the classic stories of biochemistry and signal transduction. Early work on Escherichia coli GS revealed that the enzyme was feedback inhibited by downstream products of Gln metabolism (His, Trp, AMP, CTP, carbamoylphosphate, glucosamine-6-phosphate, and NAD+), and, additionally, by the amino acids Ala and Gly (Woolfolk and Stadtman, 1964; Stadtman, 2001). Individually, each was a weak inhibitor of GS activity, but together these metabolites inhibited GS by approximately 90%. This work coined the term cumulative feedback inhibition (Woolfolk and Stadtman, 1964, 1967). It was then discovered that if the bacterial cells were cultured under different growth conditions, different kinetic forms of GS could be purified. One form was feedback inhibited by the metabolites described above, whereas the other was not. The sole difference between these enzymes was that the GS that could be inhibited by the down-stream products of Gln metabolism was adenylylated (GS-AMP) on a specific Tyr residue. At this point, an enzyme activity was found that could deadenylylate GS (Shapiro and Stadtman, 1968). During purification on a gel filtration column, it was noted that much of this deadenylylation activity was lost but could be recovered again if a column fraction mixing experiment was performed. Two pools of fractions were designated PI and PII (Shapiro, 1969). The deadenylylation activity resided in the PI fraction and was purified to homogeneity. This enzyme, adenylyltransferase (ATase), was bifunctional, catalyzing both the adenylylation/deadenylylation reactions, and its activity was modulated by the PII fraction, Gln, 2-oxoglutarate, UTP, and ATP (Anderson and Stadtman, 1971). One protein present in the PII fraction was necessary to modulate ATase activity, and the name PII has held ever since. The effect of UTP on this system was revealed when it was found that the PII protein was covalently modified by uridylylation (PII-UMP) on a Tyr residue. Another bifunctional enzyme, uridylyltransferase/removing enzyme (UT/UR), from the PI fraction catalyzed the uridylylation/deuridylylation reactions (Mangum et al., 1973). PII was purified to homogeneity and shown to be a 12-kD protein with a native mass of 44 kD (Adler et al., 1975). A crystal structure determination later revealed PII to be a homotrimer (Cheah et al., 1994).

How Does E. coli Coordinate C and N Metabolism?

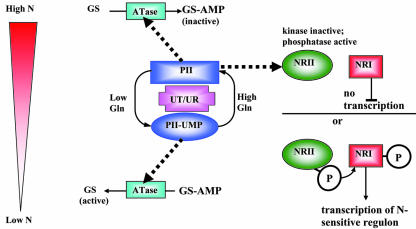

Many years of biochemistry, molecular biology, and bacterial genetics have produced the following model for how the 112-amino acid PII protein orchestrates the interactions of C and N metabolism in E. coli and related bacteria. PII does not have an enzymatic activity. It interprets the intracellular concentration of the key energy, C, and N metabolites (ATP, 2-oxoglutarate, and Gln, respectively) and interacts with two other proteins to regulate their function (Magasanik, 2000; Ninfa and Atkinson, 2000; Arcondéguy et al., 2001). This is illustrated in Figure 1. PII, unmodified by UMP, binds to ATase. The PII-ATase complex stimulates the adenylylation of GS and allows GS to be feedback inhibited by other metabolites, i.e. “inactive” GS (Jiang et al., 1998). Unmodified PII also associates with NRII, which is both a protein kinase and phosphatase (Kamberov et al., 1995). NRII is part of a two-component signaling system whereby NRII autophosphorylates on a His residue and transfers this phosphate to an Asp on the response regulator, NRI. The transcription of N-regulated genes (which includes GS and the proteins necessary for utilization of other extracellular N sources) requires the activated (phosphorylated) form of the transcription factor NRI. The binding of PII to NRII suppresses the kinase and activates the phosphatase activities of NRII, thereby dephosphorylating NRI and preventing transcription of the N-sensitive regulon.

Figure 1.

Model for the role of PII in E. coli. During conditions of N sufficiency, cellular levels of Gln (N status signal) promote deuridylylation of PII and subsequent interaction of unmodified PII with ATase, which adenylates GS to inactivate the enzyme. In parallel, PII binds N regulator II (NRII) to suppress its protein kinase activity and activate its phosphatase activity, maintaining the transcription factor NRI in a dephosphorylated, inactive state. When Gln levels drop and both the C and energy status is interpreted as adequate, PII is uridylylated by the UT/UR. PII-UMP now stimulates the activation of GS and, in the absence of affinity for NRII, allows NRII to activate NRI and promote transcription of the N-sensitive regulon. Thick dashed lines, Protein:protein interactions. Substrates for the covalent modification reactions (UTP and ATP) are not shown for simplicity.

The cellular N status molecule is Gln. A low Gln concentration allows the uridylyltransferase (UT) to modify PII by uridylylation on a specific Tyr in the T loop. It is the T-loop region that interacts with the target proteins of PII (Jiang et al., 1997; Arcondéguy et al., 2000). PII-UMP stimulates the deadenylylation of GS-AMP (by ATase), thereby promoting GS activity. PII-UMP has no affinity for NRII, which permits high protein kinase activity of NRII, leading to increased phospho-NRI and, therefore, transcription of the N-regulated genes. Conversely, a high level of Gln (N-sufficient conditions) allosterically activates the uridylyl-removing activity of the bifunctional UT/UR enzyme to deuridylylate PII-UMP. Unmodified PII activates the ATase to adenylylate and, therefore, inactivate GS. Gln also allosterically affects the ATase, stimulating the adenylylation reaction.

The C signal, 2-oxoglutarate, is sensed allosterically by PII. Each subunit of the PII trimer can bind one molecule of ATP and 2-oxoglutarate. ATP readily binds all three subunits of PII. The ATP-binding residues of PII are the most highly conserved amino acids of all compared PII sequences. 2-Oxoglutarate will not bind PII unless ATP is bound first. If ATP is bound to PII, the first 2-oxoglutarate will bind with high affinity but confers strong negative cooperativity on the binding of the next 2-oxoglutarate molecule such that saturation of PII with 2-oxoglutarate only occurs at the high end of the physiological range (Ninfa and Atkinson, 2000). For UT to uridylylate PII, 2-oxoglutarate must first be bound to PII. This signaling mechanism ensures that C is available for amino acid biosynthesis before GS is activated. Similarly, for PII to interact with NRII, it must have associated 2-oxoglutarate. If Gln concentrations are low, the C-saturated form of PII is readily uridylylated by the UT, and PII-UMP in turn activates GS in response to the high-C skeleton, low-Gln signal. The synergistic binding of ATP and 2-oxoglutarate to PII is thought to integrate the status of C and energy in the cell (Arcondéguy et al., 2001).

At this point, we must note that other PII-like proteins have been identified in prokaryotes. E. coli GlnK is 67% identical to PII, and its discovery explained several anomalies in the PII literature. The GlnK gene is invariably linked to the ammonium transporter gene amtB in prokaryotes, suggesting a functional link. It was found that GlnK binds AmtB at the membrane; this negatively regulates ammonium transport (Coutts et al., 2002). Two other PII-like proteins (NifI1 and NifI2) found in the diazotrophic methanogens play a role in the ammonium shut-off response of N fixation (Kessler and Leigh, 1999; Kessler et al., 2001). We refer readers to recent reviews (Ninfa and Atkinson, 2000; Arcondéguy et al., 2001).

Role of PII in Photosynthetic Bacteria

A homolog to the E. coli PII protein was identified from 32Pi in vivo labeling experiments in Synechococcus PCC 7942 (Forchhammer and Tandeau de Marsac, 1994). Similar to E. coli PII, the size of the PII polypeptide was estimated at 13 kD. The native mass of Synechococcus PCC 7942 PII was 36 kD, which correlates with a trimeric structure. PII is likely present in all cyanobacterial genomes (Arcondéguy et al., 2001), but in contrast to proteobacteria, additional PII-like genes have yet to be identified in cyanobacteria (Palinska et al., 2002). Cyanobacterial PII is regulated at the transcriptional level. The level of PII gene expression was the same in ammonium or nitrate-grown Synechocystis PCC 6803 cells but increased 10-fold during 7 h of N deprivation. When cells were transferred to the dark, the PII transcript decreased to undetectable levels after 5 h, and this effect could be blocked by adding Glc to the growth medium. PII protein levels remained constant for up to 10 h after transition to the dark (Garcia-Dominguez and Florencio, 1997).

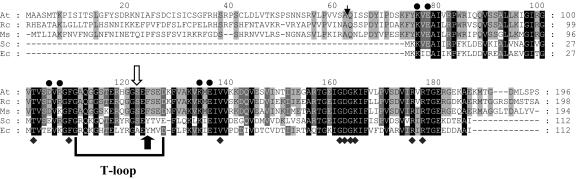

Notably, the cyanobacterial PII is posttranslationally modified by phosphorylation rather than by uridylylation. The phosphorylated residue is located at Ser-49 (Forchhammer and Tandeau de Marsac, 1995a) whereas the tyrosyl residue modified by uridylylation in E. coli PII remains conserved at position 51 (Fig. 2). In cyanobacteria, the degree of PII phosphorylation varies with N source and C supply. When Synechococcus PCC 7942 was grown in the presence of excess ammonium, PII was not phosphorylated, whereas N-starved cells exhibited a PII phosphorylated on two or three of the subunits of the PII trimer. PII from nitrate-grown cells displayed an intermediate phosphorylation state that increased with elevated inorganic C and decreased when CO2 fixation was blocked by a low concentration of inorganic C or D,L-glyceraldehyde (Forchhammer and Tandeau de Marsac, 1995b). PII-null mutant studies indicate a function linked to N uptake. In an ammonium regime, dephospho-PII controls the inhibition of nitrate and nitrite uptake, whereas in the absence of ammonium, it is thought that the liganded (2-oxoglutarate being the likely effector), phosphorylated PII alleviates this inhibition (Lee et al., 1998, 2000). Furthermore, a PII-null mutant demonstrated that the high-affinity bicarbonate transport system of Synechocystis PCC 6803 is under PII control (Hisbergues et al., 1999).

Figure 2.

Comparison of the deduced amino acid sequences of the PII polypeptides of Arabidopsis (AT), castor bean (Rc), alfalfa (Ms), Synechococcus PCC 7942 (Sc), and E. coli (Ec). Black boxes, Amino acid residues conserved in the PII proteins. The PII signature domains (T-loop and ATP-binding residues [♦]) are highlighted. Solid circles, Series of (basic/acidic-X-acidic/basic) residues that form salt bridges between the subunits of E. coli PII [•]. Solid black arrow, Position of the Tyr residue that is uridylylated in E. coli PII. White arrow, Position of the Ser residue that is phosphorylated in Synechococcus PCC 7942 and is the putative phosphorylation site in Arabidopsis. The Arabidopsis sequence before residue Q63 (and the equivalent residues in the Rc and Ms proteins) is predicted to encode a chloroplast transit peptide that is cleaved in the mature protein. The expected cleavage site (ChloroP; http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/ChloroP/) is indicated with an arrowhead.

The mechanism that regulates the posttranslational modification of cyanobacterial PII has been partially characterized. From in vitro studies, a soluble protein kinase activity was identified from Synechococcus PCC 7942 cells that phosphorylated PII at Ser-49. The protein kinase activity is dependent on the presence of the small molecules ATP and 2-oxoglutarate binding synergistically to PII (Forchhammer and Tandeau de Marsac, 1995a). The ATP and 2-oxoglutarate molecules do not effect the protein kinase directly (ATP is a substrate in the reaction as well), indicating that these small molecules confer a PII conformation that is recognized by the kinase. In contrast to the posttranslational modification of E. coli PII, phosphorylation of cyanobacterial PII is not regulated by Gln. An in vitro protein phosphatase activity was partially purified and separated entirely from the kinase activity, suggesting that these activities implicate different proteins (Irmler et al., 1997). The PII phosphatase activity was Mg2+ dependent, a characteristic of type 2C protein phosphatases (PP2C). Very recently, Forchammer's group systematically inactivated every gene encoding a type 2C protein phosphatase in Synechocystis PCC 6803 and identified the gene open reading frame sll1771 (gene product termed PphA) as that which encodes the PP2C that dephosphorylates PII (Irmler and Forchhammer, 2001). In contrast to the protein kinase that phosphorylates PII, the phosphatase activity was impaired by ATP and 2-oxoglutarate binding PII (Ruppert et al., 2002). In addition, ADP and GTP, like ATP, could partially inhibit PphA in the absence of 2-oxoglutarate. The addition of 2-oxoglutarate had no effect on PphA activity in the presence of ADP or GTP but dramatically reduced dephosphorylation in combination with ATP. Furthermore, it was shown that when the 2-oxoglutarate concentration is low, the ability of PphA to dephosphorylate PII depended upon the concentration of ATP, directly linking energy status to PII regulation (Ruppert et al., 2002). Glu or Gln had no effect on this protein phosphatase activity. This notion of PII sensing the energy status of the cell is also supported by work on Rhodospirillum rubrum (Zhang et al., 2001). Thus, the two small molecules, ATP and 2-oxoglutarate, control the conformation of cyanobacterial PII such that a molecular switch (phosphorylation/dephosphorylation) can function based on these metabolite concentrations.

In cyanobacteria, PII likely functions as a main control point to regulate nitrate/nitrite uptake and high-affinity bicarbonate transport. At this point, the identity of the PII receptors in cyanobacteria is not known.

Do Plants Have a PII Protein?

Coruzzi's group (Hsieh et al., 1998) first identified plant PII in Arabidopsis. Genome and EST sequencing has fueled the discovery of genes encoding PII proteins in plants. We have explored the EST databases and, at the time of writing, we were able to identify greater than 20 plant species having sequences with very high identity to Arabidopsis PII. This list not only includes castor bean, alfalfa, soybean (Glycine max), tomato, and rice, but numerous other monocots and dicots. There appears to only be one PII gene in each of these species and no GlnK-like proteins. The Arabidopsis PII gene product shares 50% and 54% sequence identity to E. coli and Synechococcus/Synechocystis PII, respectively, with a very high degree of sequence conservation in the ATP-binding residues (Fig. 2). The nuclear-encoded plant PII gene contains a predicted chloroplast transit peptide (ChloroP Center for Biological Sequence Analysis, 2001; Smith et al., 2003), and biochemical data indicate that PII resides in this compartment (Hsieh et al., 1998). Notably, the T-loop of plant PII contains the conserved Ser-49 residue (phosphorylated in Synechococcus PCC 7942) and the Tyr-51 residue, uridylylated in E. coli, is replaced by Phe. This amino acid sequence suggests that the plant PII may be posttranslationally modified by phosphorylation.

The expression of the plant PII gene has been shown to be regulated by light and metabolites. In dark-treated cells, PII mRNA levels were very low and were rapidly induced by light, reaching maximal levels after 8 h, and phytochrome did not appear to play a role in this induction (Hsieh et al., 1998). PII mRNA was induced in dark-adapted plants by Suc addition, and the combination of light and Suc caused accumulation beyond light-induced levels. The induction of PII mRNA could also be partially reversed by the addition of Glu or Gln (but not Asn) in the presence of light and Suc.

Plants grown in the presence of Suc but without an N source accumulate anthocyanin pigments. This process can be reversed by inorganic N or Gln addition (Hsieh et al., 1998). Transgenic Arabidopsis plants overexpressing PII accumulated anthocyanin when grown on media containing sufficient Suc but without an N source. This anthocyanin accumulation was reversed in the transgenic Arabidopsis by the addition of inorganic N but could not be relieved by addition of Gln, indicative of an inability to sense or metabolize this amino acid (Hsieh et al., 1998). These initial studies on the function of PII were suggestive of its role in an N-/C-sensing signal transduction system.

Does Plant PII Function as a Metabolite Sensor?

A survey of many important energy, C, and N metabolites showed that plant PII selectively binds ATP and 2-oxoglutarate with high affinity. Although ATP binds Arabidopsis PII in the absence of 2-oxoglutarate, affinity for ATP increases in the presence of the C signal molecule. Regardless of 2-oxoglutarate levels, the ATP-binding constants are well below chloroplast ATP concentrations, strongly suggesting that, in the plant, PII is continually bound by ATP (Smith et al., 2003). Binding studies further showed that the plant PII may function as a direct sensor of plastid C levels. As in bacteria, the plant PII binds 2-oxoglutarate only in the presence of liganded ATP (Kamberov et al., 1995; Smith et al., 2003). Importantly, the binding constant (Kd) of 2-oxoglutarate (Kd = 107 μm) is close to the estimated concentration of chloroplast 2-oxoglutarate (Kd = 70 μm; Winter et al., 1994). We have suggested that this could allow the plant PII to be a precise sensor of fluctuations of the C signal molecule. The PII signaling system may include further subtleties to monitor and coordinate cellular energy status with N assimilation. Plant PII also binds ADP with an affinity well within physiological chloroplast levels (Smith et al., 2003), but this affinity decreases in the presence of 2-oxoglutarate. Possibly, this functions as an emergency flag in the signaling cascade in the event of a precipitous drop in ATP levels and the concomitant rise in ADP concentration. Further work is necessary to establish that this is physiologically relevant.

What Can We Infer about Plant PII from Sequence Comparisons and Modeling?

Comparison of the sequences of plant and bacterial PII proteins reveals several striking features (Fig. 2). Certain residues are highly conserved, most notably the ATP-binding residues and the amino acids necessary for salt bridge formation between the three subunits. Further examination of the ATP-binding residues, as determined from the E. coli PII-ATP crystal structure (Xu et al., 2001), shows that they are the most conserved residues in all PII proteins. This undoubtedly illustrates a critical function for ATP binding and likely links perception of cellular energy status with PII function. Benelli et al. (2002) recently solved the structure of Herbaspirillium seropedicae PII and noted that this PII shared relatedness to 5-carboxymethyl-2-hydroxymuconate isomerase and 4-oxalocrotonate tautomerase, both of which isomerize α-ketoacids. A superposition of PII with 4-oxalocrotonate tautomerase bound to 2-oxo-3-pentynoate (an inhibitor of isomerization) indicated that 2-oxoglutarate might bind very near ATP in the cleft between two subunits. The two proposed 2-oxoglutarate-binding residues, Lys-90 and Arg-101 (in E. coli PII), are highly conserved in all PII proteins, including plant PII.

Interestingly, the region that forms the T loop, which is responsible for protein:protein interactions between bacterial PII and its targets, is not highly conserved between plants and bacteria. This may reflect the evolution of plant PII to interact with different proteins than the known targets in bacteria. The entire plant PII sequence (minus the transit peptide) was easily modeled on the E. coli structure with a low root mean square deviation. Recombinant Arabidopsis PII minus the predicted chloroplast transit peptide chromatographed as a 50-kD protein during gel filtration and migrated as 17 kD on SDS-PAGE implying that, like bacterial PII, plant PII is a homotrimer (Smith et al., 2002, 2003). Sequence comparisons, molecular modeling, and the observed mass of plant PII further support the notion that this protein maintains the same architecture as its bacterial counterparts and binds ATP and 2-oxoglutarate in a similar fashion.

Research Questions Ahead

The plant PII amino acid equivalent to the cyanobacterial phosphorylation site (Ser-49) is conserved. In light of the fact that covalent modification is so significant in prokaryotic PII function, we predict that plant PII will be phosphorylated at this position also, although data to support this hypothesis are lacking (Smith et al., 2003). This implies that a protein kinase and phosphatase exist in the chloroplast to perform the regulatory role. The other major question to be resolved is the identification of the protein targets of plant PII. Only when we identify the downstream targets of PII will we be able to dissect the signaling pathway and the regulatory events controlled by PII in plants. In cyanobacteria, PII clearly plays a role in the uptake of nitrate and nitrite (Lee et al., 2000). It is attractive to speculate that the plant PII signaling cascade plays a similar role; in this case, the uptake of nitrite and ammonium into the chloroplast. Nitrite produced in the cytosol and ammonium, much of which is derived from photorespiration, is transported into the chloroplast. Ammonium transporters have yet to be well defined in the chloroplast membrane. The Arabidopsis ammonium transporter, AtAMT1;2, has a putative chloroplast transit peptide, but initial studies failed to demonstrate chloroplast import (Shelden et al., 2001). The regulated transport of nitrite into the chloroplast has been addressed in the algae Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Evidence suggests that the Nar1;1 gene and possibly other family members encode high-affinity chloroplast nitrite transporters in C. reinhardtii. It is unclear if a plastid membrane NAR family exists in plants, although nitrite transporters are thought to reside here (Galván et al., 2002).

CONCLUSIONS

PII is one of the most conserved and widespread signal transduction proteins known, with paralogs found across the three domains of life. This remarkable conservation suggests that PII is likely an ancient molecule that evolved early in life's history. In recent years, there has been a resurgence of interest in the link between energy, C, and N metabolism and the regulation of other cellular processes. For instance, the histone deacetylase Sir2 has been found to be dependent upon NAD+ for activity and may provide a link between the redox status of the cell and chromatin remodeling and transcriptional silencing (Denu, 2003). The mammalian protein kinase mTOR senses amino acid and ATP availability and, in accordance, adjusts protein and ribosome biosynthesis (Dennis et al., 2001). In the yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) TOR signaling pathway, Gln appears to be the key amino acid signal (Crespo et al., 2002). In mammalian cells, the ratio of AMP to ATP elicits a response by AMP-activated protein kinase that, in turn, modifies the cellular metabolic program in response to changing ATP levels (Hardie and Hawley, 2001). The cumulative observations that certain metabolites play a capacity in global regulation of cellular processes reinforce the notion that a molecule like PII, which interprets key energy, C, and likely N metabolites, is going to be of fundamental importance to the metabolism of the plastid.

Acknowledgments

We thank Hue Tran for assistance in sequence comparisons.

This work was supported by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada.

References

- Adler SP, Purich D, Stadtman ER (1975) Cascade control of Escherichia coli glutamine synthetase: properties of the PII regulatory protein and the uridylyltransferase-uridylyl removing enzyme. J Biol Chem 16: 6264–6272 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson WB, Stadtman ER (1971) Purification and functional roles of the PI and PII components of Escherichia coli glutamine synthetase deadenylylation system. Arch Biochem Biophys 143: 428–443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arcondéguy T, Jack R, Merrick M (2001) PII signal transduction proteins, pivotal players in microbial nitrogen control. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 65: 80–105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arcondéguy T, Lawson D, Merrick M (2000) Two residues in the T-loop of GlnK determine NifL-dependent nitrogen control of nif gene expression. J Biol Chem 275: 38452–38456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benelli ME, Buck M, Polikarpov I, Maltempi de Souza E, Cruz LM, Pedrosa FO (2002) Herbaspirillum seropedicae signal transduction protein PII is structurally similar to the enteric GlnK. Eur J Biochem 269: 3296–3303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheah E, Carr PD, Suffolk PM, Vasudevan SG, Dixon NE, Ollis DL (1994) Structure of the Escherichia coli signal transducing protein PII. Structure 2: 981–990 0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ChloroP Center for Biological Sequence Analysis (2001) ChloroP 1.1 Prediction Server. http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/ChloroP/

- Coutts G, Thomas G, Blakey D, Merrick M (2002) Membrane sequestration of the signal transduction protein GlnK by the ammonium transporter AmtB. EMBO J 21: 536–545 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crespo JL, Powers T, Fowler B, Hall MN (2002) The TOR-controlled transcription activators GLN3, RTG1, and RTG3 are regulated in response to intracellular levels of glutamine. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 99: 6784–6789 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis PB, Jaeschke A, Saitoh M, Fowler B, Kozma SC, Thomas G (2001) Mammalian TOR: a homeostatic ATP sensor. Science 294: 1102–1105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denu JM (2003) Linking chromatin function with metabolic networks: Sir2 family of NAD(+)-dependent deacetylases. Trends Biochem Sci 28: 41–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forchhammer K, Tandeau de Marsac N (1994) The PII protein in the cyanobacterium Synechococcus sp. strain PCC 7942 is modified by serine phosphorylation and signals the cellular N-status. J Bacteriol 176: 84–91 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forchhammer K, Tandeau de Marsac N (1995a) Phosphorylation of the PII protein (glnB gene product) in the cyanobacterium Synechococcus sp. Strain PCC 7942: analysis of in vitro kinase activity. J Bacteriol 177: 5812–5817 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forchhammer K, Tandeau de Marsac N (1995b) Functional analysis of the phosphoprotein PII (glnB gene product) in the cyanobacterium Synechococcus sp. strain PCC 7942. J Bacteriol 177: 2033–2040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galván A, Rexach J, Mariscal V, Fernandez E (2002) Nitrite transport to the chloroplast in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii: molecular evidence for a regulated process. J Exp Bot 53: 845–853 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Dominguez M, Florencio FJ (1997) Nitrogen availability and electron transport control the expression of glnB gene (encoding PII protein) in the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. Plant Mol Biol 35: 723–734 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardie DG, Hawley SA (2001) AMP-activated protein kinase: the energy charge hypothesis revisited. Bioessays 23: 1112–1119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hisbergues M, Jeanjean R, Joset F, Tandeau de Marsac N, Bedu S (1999) Protein PII regulates both inorganic carbon and nitrate uptake and is modified by a redox signal in Synechocystis PCC 6803. FEBS Lett 463: 216–220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh M, Lam H, Van de loo FJ, Coruzzi G (1998) A PII-like protein in Arabidopsis: putative role in nitrogen sensing. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95: 13965–13970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irmler A, Forchhammer K (2001) A PP2C-type phosphatase dephosphorylates the PII signaling protein in the cyanobacterium Synechocystis PCC 6803. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98: 12978–12983 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irmler A, Sanner S, Dierks H, Forchhammer K (1997) Dephosphorylation of the phosphoprotein P(II) in Synechococcus PCC 7942: identification of an ATP and 2-oxoglutarate-regulated phosphatase activity. Mol Microbiol 26: 81–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang P, Zucker P, Atkinson MR, Kamberov ES, Tirasophon W, Chandran P, Schefke BR, Ninfa AJ (1997) Structure/function analysis of the PII signal transduction protein of Escherichia coli: genetic separation of interactions with protein receptors. J Bacteriol 179: 4342–4353 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang P, Peliska JA, Ninfa AJ (1998) The regulation of Escherichia coli glutamine synthetase revisited: role of 2-ketoglutarate in the regulation of glutamine synthetase adenylylation state. Biochemistry 37: 12802–12810 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamberov ES, Atkinson MR, Ninfa AJ (1995) The Escherichia coli PII signal transduction protein is activated upon binding 2-ketoglutarate and ATP. J Biol Chem 270: 17797–17807 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler PS, Daniel C, Leigh JA (2001) Ammonia switch-off of nitrogen fixation in the methanogenic archaeon Methanococcus maripaludis: mechanistic features and requirement for the novel GlnB homologues, NifI(1) and NifI(2). J Bacteriol 183: 882–889 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler PS, Leigh JA (1999) Genetics of nitrogen regulation in Methanococcus maripaludis. Genetics 152: 1343–1351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lancien M, Gadal P, Hodges M (2000) Enzyme redundancy and the importance of 2-oxoglutarate in higher plant ammonium assimilation. Plant Physiol 123: 817–824 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee HM, Flores E, Forchhammer K, Herrero A, Tandeau De Marsac N (2000) Phosphorylation of the signal transducer PII protein and an additional effector are required for the PII-mediated regulation of nitrate and nitrite uptake in the Cyanobacterium synechococcus sp. PCC 7942. Eur J Biochem 267: 591–600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee HM, Flores E, Herrero A, Houmard J, Tandeau de Marsac N (1998) A role for the signal transduction protein PII in the control of nitrate/nitrite uptake in a cyanobacterium. FEBS Lett 427: 291–295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magasanik B (2000) PII: a remarkable regulatory protein. Trends Microbiol 8: 447–448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mangum JH, Magni G, Stadtman EM (1973) Regulation of glutamine synthetase deadenylylation by the enzymatic uridylylation and deuridylylation of the PII regulatory protein. Arch Biochem Biophys 158: 514–525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melo-Oliveira R, Oliveira IC, Coruzzi GM (1996) Arabidopsis mutant analysis and gene regulation define a nonredundant role for glutamate dehydrogenase in nitrogen assimilation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 93: 4718–4723 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ninfa AJ, Atkinson MR (2000) PII signal transduction proteins. Trends Microbiol 8: 172–179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palinska KA, Laloui W, Bedu S, Loiseaux-de Goer S, Castets AM, Rippka R, Tandeau de Marsac N (2002) The signal transducer P(II) and bicarbonate acquisition in Prochlorococcus marinus PCC 9511, a marine cyanobacterium naturally deficient in nitrate and nitrite assimilation. Microbiology 148: 2405–2412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reith ME, Munholland J (1995) Complete nucleotide sequence of the Porphyra purpurea chloroplast genome. Plant Mol Biol Rep 13: 333–335 [Google Scholar]

- Ruppert U, Irmler A, Kloft N, Forchhammer K (2002) The novel protein phosphatase PphA from Synechocystis PCC 6803 controls dephosphorylation of the signaling protein PII. Mol Microbiol 44: 855–864 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro BM (1969) The glutamine synthetase deadenylylation enzyme from Escherichia resolution into two components, specific nucleotide stimulation and cofactor requirements. Biochemistry 8: 659–710 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro BM, Stadtman ER (1968) Glutamine synthetase deadenylylating enzyme. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 30: 32–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shelden MC, Dong B, de Bruxelles GL, Trevaskis B, Whelan J, Ryan PR, Howitt SM, Udvardi K (2001) Arabidopsis ammonium transporters, AtAMT1;1 and AtAMT1;2, have different biochemical properties and functional roles. Plant Soil 231: 151–160 [Google Scholar]

- Smith C, Zaplachinski S, Meunch D, Moorhead GBG (2002) Expression and purification of the chloroplast putative nitrogen sensor PII, of Arabidopsis thaliana. Protein Expr Purif 25: 342–347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith C, Weljie AM, Moorhead GBG (2003) Molecular properties of the putative nitrogen sensor PII from Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J 33: 353–360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stadtman ER (2001) The story of glutamine synthetase regulation. J Biol Chem 276: 44357–44364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winter H, Robinson DG, Heldt HW (1994) Subcellular volumes and metabolite concentrations in spinach leaves. Planta, 193: 530–535 [Google Scholar]

- Woolfolk CA, Stadtman ER (1964) Cumulative feedback inhibition in the multiple end-product regulation of glutamine synthetase activity in Escherichia coli. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 17: 313–319 [Google Scholar]

- Woolfolk CA, Stadtman ER (1967) Regulation of glutamine synthetase: III. Cumulative feedback inhibition of glutamine synthetase from Escherichia coli. Arch Biochem Biophys 118: 736–755 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y, Carr PD, Huber T, Vasudevan SG, Ollis DL (2001) The structure of the PII-ATP complex. Eur J Biochem 268: 2028–2037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Pohlmann EL, Ludden PW, Roberts GP (2001) Functional characterization of three GlnB homologs in the photosynthetic bacterium Rhodospirillum rubrum: roles in sensing ammonium and energy status. J Bacteriol 83: 6159–6168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]