Societies and social groups within them are becoming aware that food and fiber are not gifts of nature that come to us cost-free from the natural world because their production involves consumption of renewable and nonrenewable resources as well as expenses for capital and variable inputs in the production process, plus outlays for transportation, processing, marketing, and food preparation. The essence of food and fiber production is that on one hand, the key production resources (seeds, tubers, soil, manures, and rain water) are renewable resources, thus potentially enabling agriculture to be a highly sustainable activity. On the other hand, agriculture has some actual or potential characteristics of an extractive industry, similar to mining, and accordingly has the potential to be highly unsustainable. In addition, food and fiber production may involve long-term nonenvironmental costs (e.g. impacts on workers, communities, regions, and consumers) to a greater or lesser degree. In this paper, I use the expression “societal costs” of agriculture to pertain to adverse impacts of agrofood systems on human health, environmental quality, and the welfare and livelihoods of social groups. (A focus on the societal costs of food and fiber production does not, of course, involve a presumption that the benefits of this production, both to humans and non-human portions of the biosphere, are insignificant.)

HOW SHOULD FOOD AND FIBER PRODUCTION BE REGULATED?

The notion that agriculture has societal costs is related to the neoclassical economics concepts of “market failure” and “externalities.” Market failure exists when the self-interested behavior of economic actors in a market leads to a suboptimal allocation of resources. Externalities—reductions in the welfare of others that are not accounted for in the price system or through compensation—are one of the most common types of market failures. (Typically, the term externality is employed in a manner that presumes that the referent is to negative consequences for the welfare of individuals or society as a result of the production process. Note, however, that there logically exist “positive” externalities, which economists often refer to as “external economies of production” or a “spillover effect.” In this paper, the notion of externality will be used to refer to negative outcomes rather than external economies and spillovers.) Economists tend to hypothesize that, in principle (although not necessary in practice, given the vagaries of the policy-making process), compensatory market incentives can be introduced that will readily reduce the societal costs of food and fiber production and do so in an efficient manner. As I will stress below, however, this is not always the case with some of the most important and contested societal costs of food and fiber production.

How should the human need for food and the social benefits of the food and fiber production systems be assessed in relation to the societal costs of production systems and practices? For most of the history of western agriculture, there has been little explicit awareness that agricultural production might have significant societal costs, and there has been even less impulse to influence the behavior of agriculturalists and performance of agriculture accordingly. This may be surprising because history teaches us that early civilizations declined because they did not pay attention to the environmental ravages of their agricultural practices. Even so, there have been a good many efforts, such as the promulgation of land use regulations, the expansion of support for public agricultural research, and the development of food, chemical, and drug safety rules, that can be thought of as institutional interventions to reduce the societal costs of agriculture. In addition, measures to curb the power of large landlords, industrial farm operations, railroads, and agribusinesses were undertaken to ensure broader public benefit from the food and fiber production system (Danbom, 1995). These regulatory impulses, however, have tended to be weaker in the United States than in most other industrial countries. Our family farming heritage and respect for the yeoman food producer have caused policy-makers to be cautious about harming hard-working rural small businesspeople through mandatory regulation. Most agricultural pollutants are from non-point rather than from point sources, which makes measurement and regulation difficult. Finally, the spaciousness of the United States and our extensive pattern of rural land use have historically made dispersion of pollutants a socially—if not a technically—feasible alternative to regulating farms in the same manner that metropolitan industry and municipalities have been regulated. My analysis of the issues surrounding how we could go about internalizing those societal costs is based on the U.S. experience, but the lessons that are learned are not limited to the United States.

GROWING ATTENTION TO THE SOCIETAL COSTS OF FOOD AND FIBER PRODUCTION

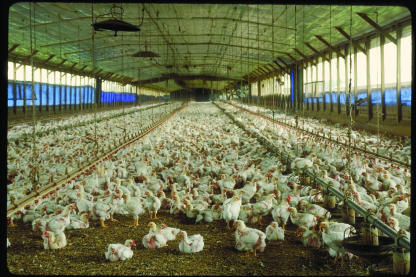

In recent years, we have witnessed greater attention to the societal costs associated with agricultural production systems and practices. This expanded attention has three major origins. First, there has been growing attention by environmental groups and environmental regulatory agencies in the United States to the impacts of agricultural practices on environment, human health, and animal welfare. In many instances, these environmental problems have crossed the line from non-point (cows in a pasture) to point (cows in a large feedlot) sources of pollution and have led to increasingly vehement calls by activist groups to regulate farm producers the same way the government treats other point sources of pollution. Second, the rise of increasingly large-scale industrial agriculture enterprises—especially “factory”-like concentrated animal feed operations (CAFOs) and large-scale field crop monocultures— has generated opposition in their own right; in many instances, for example, activist groups contesting the practices of CAFOs are as interested in eradicating large-scale animal agriculture as they are in achieving rural environmental quality. Third, there are growing concerns from public interest groups about the social and environmental impacts of particular new technologies such as precision farming, genetically modified crops, the use of recombinant bovine somatotropin, or the use of antibiotics as feed additives in poultry farms (Fig. 1; Cranor, 2003). The anti-genetically modified (GM) crop movement is a particularly important instance of this third thrust involved in the growing attention to the societal costs of agriculture, in that the costs and risks of GM crops and foods that generate concern are often not seen as costs and risks by many scientists, farmers, and regulatory personnel.

Figure 1.

Societal costs of agricultural practices. The sub-therapeutic use of antibiotics in cattle, swine, and poultry rations is most common on farms with large-scale confinement facilities, such as this poultry farm in Florida. Use of antibiotics in animal feed that are employed to treat humans tends to foster antibiotic resistance in bacteria that can then be transmitted to bacteria that cause infectious diseases in humans. U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) photo by Larry Rana.

Finally, recent changes in regulatory doctrine and practices, such as the “precautionary principle” (PP) and the “fourth hurdle,” which are the de facto regulatory doctrine in the European Union (EU), have signaled a new receptivity to preventing, rather than merely ameliorating, the societal costs of agricultural production. Each of these relatively recent initiatives is aimed at altering or influencing the behaviors of agriculturalists to reduce the actual or perceived costs of agrofood systems. The PP—sometimes referred to as the Precautionary Polluter Pays Principle (or “4P”), in recognition of the fact that it is premised on the notion that firms should be directly responsible (including the payment of fines to the government and compensating victims) if a technology or production practice proves to be harmful—is a regulatory doctrine that involves several departures from the U.S. approach. First, it involves a shift in the burden of proof from government regulatory agencies to private firms; thus, under the PP, it is not the obligation of government to prove that a new product or production practice is harmful, but rather an obligation of private firms to prove that it is safe. Second, the scientific standard for implementing the PP in regulatory decision-making is a more encompassing one than in the U.S. system (which is generally referred to as a “substantial equivalence” system). (Substantial equivalence regulatory doctrine essentially involves the principle that “if the new or modified food or food component is determined to be substantially equivalent to an existing food, then further safety or nutritional concerns are not expected to be significant” [Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development, 1993]. There is now a vigorous and growing debate as to whether the PP or substantial equivalence is the most appropriate regulatory framework for assessing new technologies that may have major implications for human and animal health and ecosystem integrity [see Millstone et al., 1999; Juma, 2000].) Products or practices could be disapproved if there is evidence of any harm and/or if there it is a plausible scientific rationale that approval could lead to negative health or environmental effects (for a critique of the PP as applied to new agricultural technologies, see van den Belt, 2003).

The fourth hurdle is not a formal regulatory policy practice, but rather it is the term some observers use to refer to the EU procedure that gives national-government ministers the final authority to approve or disapprove a regulatory request (Lacy, 2002). The fourth hurdle is an allusion to the fact that there is an implicit “social impact” hurdle beyond the three regulatory criteria—product efficacy, safety with respect to human health, and safety with respect to the environment and animals—that are widely accepted in both the EU and the United States. In recent years, the EU has apparently based some regulatory decisions, such as the moratoria on recombinant bovine somatotropin (1993) and new genetically modified crop varieties (1999), at least in part on “political” criteria such as the likely social implications or impacts of a new technology. The U.S. government— particularly the State Department and the U.S. Trade Representative—has been highly critical of these decisions and about the EU practice of permitting politicians to have the final say on regulatory decisions. In activist quarters, however, the PP of the EU and the ability of the EU to pose a de facto fourth hurdle are admired and seen as the direction in which public policy-making in the United States ought to move. The PP and the fourth hurdle are embraced most strongly by the EU, but there is support for these two regulatory doctrines in much of East Asia and the developing world. The more independent and science-driven system in the United States for approving new agricultural technologies is often incompatible with the regulatory systems of other countries, particularly those of the EU.

ALTERNATIVE APPROACHES TO INTERNALIZING THE SOCIETAL COSTS OF FOOD AND FIBER PRODUCTION

The sustainability imperative and the notion that agricultural institutions should maximize the social benefits and reduce the social costs of food and fiber production do not lead to a straightforward public policy formula or even to a straightforward analytical procedure for simultaneous optimization of sustainability and social benefits. In practice, the sustainability component of agrofood systems tends to be dealt with within particular regulatory agencies (e.g. the Environmental Protection Agency, state environmental protection or natural resources departments, local planning and zoning boards), whereas the main thrusts of U.S. agricultural policy—commodity programs, public research, and conservation programs—are dealt with separately by other parties such as the U.S. Congressional and Senate committees that shape the Farm Bill, national and state departments of agriculture, and state legislatures. Within each of these, there are multiple conflicts among multiple actors.

There are two basic strategies for internalizing the costs of food and fiber production: regulation and market incentives. Regulation refers mainly to state (national or subnational government) practices aimed at supervising and controlling private economic activities to accomplish more or more social goals such as ensuring competition, reducing externalities, promoting fairness, and ensuring health and welfare (although there are some instances in which private regulation, such as third-party, organic producer-organized standard-setting that predated the new USDA National Organic Program, can occur). The two main types of regulatory approaches are: (a) use of the legislative process to develop liability and torts law, which establishes civil penalties for damages resulting from behavior that is harmful to other individuals or groups, and (b) legislative or administrative processes that result in government regulatory controls (e.g. health regulations, environmental regulations, technology approval practices, and GM product regulations) that directly prescribe or proscribe producer behaviors and practices.

Market incentives approaches are also generally based on government action, but instead of the state directly prescribing or proscribing producer behavior, these approaches involve modifying the system of price signals in some significant way to encourage producers to engage in appropriate behavior (e.g. soil conservation structures). Also, market incentives approaches may occur in tandem with a regulatory approach. There are three main types of market incentives programs. The first is that of “conventional” subsidy programs, which reduce the cost of a producer engaging in desirable behavior; the US Soil Conservation Service and the National Resources Conservation Service and state government cost-sharing of soil and water conservation investments have been particularly important historical examples of this approach. The second type of market incentives approach is one that ties the receipt of production subsidies or other benefits to agricultural producers to environmental compliance (e.g. cross-compliance provisions of 1980s U.S. Farm Bills that required use of reduced-tillage practices in exchange for benefits from commodity programs; Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Mechanisms to mitigate societal costs of agriculture. Tying production subsidies to specific agricultural practices is one way that governments can influence those practices. Shown here is a large farm in Iowa that is practicing no-till farming. No-till practices reduce soil erosion and air pollution (from dust) and save water. USDA photo by Tim McCabe.

The third type of market incentive program is one that aims to influence farmer or agribusiness behavior indirectly through, for example, “green taxes.” Note that although there are significant green taxes in some European countries (e.g. 15% taxes on agricultural chemicals in Norway), no green taxes have been implemented in the United States. In fact, there are “negative green taxes” in many American states because agricultural chemicals are often exempted from state sales taxes; such “negative green taxes” basically amount to a tax subsidy of their use. Many U.S. advocates of the green taxation approach are now pushing for “environmental tax shifting,” which involves repealing tax exemptions on pesticides and fertilizer that subsidize or encourage their use while reducing other taxes (e.g. on net farm income) to make the shift “revenue equal”—a crucial consideration in a the current political environment of obsession with “no new taxes” and preoccupation with the efficiency of government programs.

THE COSTS AND BENEFITS OF AGRICULTURE DO NOT ALWAYS LEND THEMSELVES TO BEING MEASURED IN YEN, DOLLARS, OR EUROS

Thus far, the discussion has presumed that the notion of “costs” (and “benefits”) is a straightforward one—that what is a cost or benefit is quite tangible, is widely agreed upon, and can readily be measured. But many costs are not highly tangible because, for example, they cannot be directly observed. For example, much of the knowledge about “ecosystem services” in agriculture has only been developed over the past decade or so (for some of the pioneering references, see Costanza et al., 1997; Dailey, 1997; Pearce, 1998). Many ecosystem services (e.g. carbon sequestration) cannot be directly observed. Many of the positive and negative things that agriculture does with respect to the environment (e.g. water purification and nutrient run-off, respectively, depending on the type of farming operation and agro-ecosystem) are largely invisible. Others (provision of wildlife habitat and creation of a scenic countryside) are very valuable to some and without value to others. We now know much more about how agriculture creates or maintains, as well as how it can destroy, ecosystem services such as the quantity and quality of water. There are frequent attempts to quantify these less tangible benefits and costs of food and fiber production. But doing so is difficult.

Costs and benefits are partly an objective matter, which lend themselves to “cost-benefit” analysis and, if things go well, to public policies that use these data to maximize benefits and minimize costs. The growing demand for accountability in government makes it increasingly imperative that new regulations, new taxes, repeals of tax subsidies and exemptions, and new expenditures on incentives be justified in cost-benefit terms. Many costs and benefits, however, do not readily lend themselves to measurement in monetary terms; many of the costs and benefits of food and fiber production, in fact, are “incommensurable” in that they do not lend themselves to measurement with a common metric, such as yen, dollars, or euros. This is partly because costs and benefits have a subjective dimension. The fact that costs and benefits are partly subjective makes it particularly likely that various groups in society will disagree about the particulars. The fact that costs and benefits may be incommensurable makes it even more likely that various groups in the agrofood production system will make radically different judgments on these matters.

THREE ETHICAL DILEMMAS IN INTERNALIZING SOCIETAL COSTS

There are three particularly vexing ethical dilemmas about whether and how to internalize the costs of agricultural production. The first dilemma is rooted in the fact that farmers and the rest of society may have quite different views about the benefits and costs of food and fiber production. Farmers, of course, tend to select enterprises and practices to maximize private benefits, whereas the bulk of the costs of agricultural production are externalized onto non-farmers. (These processes are clearly not specific to agriculture. A major theory in environmental policy, that of the “distancing and the quest for frontiers” [Princen, 2002] is based on the notion that rational producers and resource decision-making entities can be expected to strive to externalize costs of production and that “business strategy and state policy creates a never ending search for frontiers, defined in political, economic, and ecological terms.” The two main processes of creating a “frontier economy”—one that lacks jurisdictional authority over externalized costs, little social resistance to externalization of costs, and free or inexpensive waste sinks—are shading [the obscuring of costs] and distancing [the spatial separation of production and consumption]. For Princen, agriculture is one of the prototypical instances of a modern frontier economy.) Further, farmers may be quite divided about whether and how measures should be taken to reduce the societal costs of food and fiber production. Should policy-makers pay greatest heed to the views and interests of farmers when designing policies? If farmer stakeholders' views are judged most important, should decision-makers pay most attention to the small handful of farmers that produce the bulk of the nation's food and fiber? Or should they give equal or greater attention to the views and interests of small- and medium-sized traditional family farmers, who are numerically the most predominant but who tend not to comprise the dominant component of the overall production system? Should policy-makers pay most attention to the views and interests of the mass of citizens and consumers, who are far more numerous than farmers as a whole and who pay the lion's share of the tax revenues that go to farmers as subsidies? Should policy-makers rely mainly on scientists' recommendations based on established “sound science”? Or should policy-makers consider more preliminary results from scientific work and strive to regulate in a manner that is precautionary and is able to prevent—rather than just ameliorate—pollution, other forms of environmental degradation, and other types of societal costs of agriculture?

A second ethical dilemma related to the first concerns the matter of who should decide about whether the societal costs of food and fiber production should be internalized. One way to approach this dilemma is to think about what are the central or “hot-button” issues in the area of societal costs of food and fiber production. Most observers would likely agree that regulation, registration, and re-registration of pesticides; regulation of GM crops; regulation of air and water pollution by CAFOs; the hypoxia zone, point, and non-point pollution by farm operations; the industrialization of agriculture; multifunctionality; agri-environmental payments, land use, and urban sprawl; antibiotic resistance from subtherapeutic use of human antibiotics in animal feeds; and enhancement of ecosystem services are eight of the most important issues. Most of these issues are, at least indirectly, environmental issues. One seemingly obvious conclusion is that environmental agencies, such as the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and state departments of environmental protection or natural resources, should be the lead agencies in assessment of societal costs and development of policies to address these costs. But there is clearly no national consensus on this point. It is clearly the case that over the past 20 years, and especially during the Bush Administration years, the authority of the U.S. EPA and of state departments of environmental protection has been decisively reduced. The EPA and other environmental regulatory agencies enjoyed substantially more authority in the 1970s when there was not a strong counterweight to the environmental movement. But since that time, there has arisen an influential anti-environmental movement that is now at its political apogee.

Given this new political environment, the third ethical dilemma and the most fundamental one concerns how the disparate public policy criteria of efficiency, effectiveness, fairness, and social acceptability should be used to weigh the various policy alternatives for internalizing the costs of food and fiber production. Farmers tend to be resistant to initiatives to reduce the societal costs of agriculture if these initiatives would be costly or would portend a “slippery slope” of inviting more stringent regulation; these groups invariably have a preference for incentives and voluntary programs over mandatory regulation. But there is also usually considerable internal variation among farmers as to their views on initiatives to reduce the societal costs of food and fiber production. The most common tendency is that the largest commercial producers are most resistant to changes to the status quo, whereas some smaller or medium-sized producers may welcome new regulations or market incentives if they feel they will enhance the competitive standing of smaller or “familytype” producers. Other farm producers will react to such initiatives largely on ideological grounds—typically resisting regulation or being negative about new taxes under almost all circumstances, being against more government involvement in principle, or believing that there is something special about agriculture that ought to exempt it from citizen reviews and social regulation. Put somewhat differently, Thompson (1998) has noted that “Agricultural producers and those who support them with technology may have been seduced into thinking that so long as they increased food availability, they were exempt from the constant process of politically negotiating and renegotiating the moral bargain that is at the foundations of modern democratic society.”

Equal or greater variability in the views of agricultural researchers and non-farm people on these issues exists as well. Lyson's (1986) empirical research on general public views about farmers and farming has revealed that non-farm people now tend to have little interest in agriculture and are increasingly apathetic about farmers' problems. The rank-and-file of the public at large tends not to have high awareness of or knowledge on any of these “externality issues” nor does it tend to have strongly held a priori views—or at least this tends to be the case in the United States, although there are clear differences with respect to the GM crop issue (Gaskell et al., 1999). Public apathy toward agriculture frequently gives way to significant local resistance, however, when attempts are made to site CAFOs in agricultural regions (Constance et al., 2003). And the nonfarming public also contains social movement organizations and other organizations and groups with very strongly held, diametrically opposed views that parallel (and that help to reinforce) the extreme partisanship in the U.S. political and policy-making system. Wells (2003) terms this juxtaposition of aggressive producer and trade group organizations with equally aggressive social movements and a public that is alternatively apathetic and mobilized the “contingent creation of rural interest groups.” Policy-making that pertains to the externalities and costs of agriculture has thus become more ideological, partisan, and contested, much like a good many other issue areas in contemporary politics.

TWO EXAMPLES ILLUSTRATE THE DIFFICULTIES IN RESOLVING THESE ETHICAL DILEMMAS THROUGH LEGISLATION

The ethical dilemmas associated with addressing the societal costs of food and fiber production can be illustrated through very brief case studies of two prominent problems of contemporary agriculture: (a) the “excess” of fixed nitrogen that leads to the hypoxia (or the “dead zone”) in the Gulf of Mexico, other coastal waters, and some lakes (Vitousek and Howarth, 1991; Howarth et al., 1996; Vitousek et al., 1997), and (b) the air and water pollution problems (particularly hydrogen sulfide emissions that apparently can lead to severe neurological damage in humans) resulting from large-scale pork production facilities (U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, 1996; Fig. 3). (“Hypoxia” means “low oxygen,” and is generally used to refer to a concentration of <3 mg L-1 water. The largest hypoxia zone is in the Gulf of Mexico, but other coastal areas, particularly Long Island Sound, have repeated hypoxic events. Hypoxia is caused by an overabundance of nutrients that result in algal blooms. When the algae decay, they deplete the water of oxygen. Hypoxia kills fish and is believed to cause habitat destruction and long-term changes in the ecology of coastal waters; http://esa.sdsc.edu/hypox5.htm.)

Figure 3.

Agricultural practices that cause air pollution. Lagoons such as this one are commonly used to store and treat hog manure on large CAFO hog farms. Lagoons emit hydrogen sulfide, a toxic gas. As much as 65% to 75% of the nitrogen content of manure is lost during storage, treatment, and handling. Much of this lost nitrogen contaminates the air and water downstream and downwind from large hog farms. USDA photo by Ken Hammond. Legend for the hypoxia map. A U.S. Geological Survey map shows the Mississippi River drainage basin and the extent of the hypoxia zone in the Gulf of Mexico in the late 1990s (http://webserver.cr.usgs.gov/hypoxia/html/graphics.html; http://www.meteor.iastate.edu/gccourse/issues/agri/images/paper1.gif; http://webserver.cr.usgs.gov/hypoxia/html/graphics4.html).

Both issues have several critical characteristics in common. First, both problems have their origins in the structural changes of modern agriculture. Hypoxia problems, for example, are caused by algal blooms that result from nutrient enrichment. In this case, the use/overuse of nitrogen fertilizers made possible by industrial nitrogen fixation has permitted large-scale monocultures of field crops in the Mid-west and the Mississippi River basin and has resulted in large amounts of N entering the Gulf of Mexico (Vitousek et al., 1997). Hydrogen sulfide air pollution is caused by the industrialization and spatial concentration of swine production—namely, manure disposal in lagoons and through ground application or aerial spraying of manure (Donham et al., 2002; Iowa State University and the University of Iowa Study Group, 2002). Both problems could in some sense be resolved if these agricultural-structural changes could be reversed by returning to more diversified farms, crop rotations, smaller animal production units, and the closer integration of crop and livestock enterprises. But doing so would be almost impossible to accomplish because there are enormous investments and sunk capital costs involved in both types of production systems; these investments and sunk costs occur not only at the farm level but all across the commodity chain from inputs through production, processing, and marketing.

Second, both problems are documented in the scientific literature at a level that could be characterized as reasonably persuasive but not “open-and-shut.” The connections of hypoxia and hydrogen sulfide pollution to prevailing agricultural practices are documented in the scientific literature to a degree that the typical scientist would accept that there is probable cause to believe that a bona fide problem exists and that ameliorative action is warranted. (In the case of the hypoxia, the chief uncertainty claim that is made is that integrated assessments of the hypoxia problem may exaggerate agricultural causes and underestimate the role of forests, municipalities, and other sources of N entering the Gulf of Mexico [see the “public comments” on the NOAH hypoxia assessment at http://www.nos.noaa.gov/products/pubs_hypox.html]. In the case of hydrogen sulfide, the principal uncertainty argument is that there is no clear evidence that hog-farm-produced hydrogen sulfide emissions are causally connected to the neurological and respiratory illnesses experienced by neighbors.) In terms of the regulatory categories discussed earlier, the science behind these phenomena would arguably justify “precautionary” action, but it would likely not be sufficient to lead to major civil penalties. Neither problem has served as the justification for a major new regulatory initiative or for a costly incentive program capable of dealing with the problem. The lack of “drop-dead” evidence that these problems are causally related to prevailing practices leaves room for persuasive “uncertainty arguments”—claims that because of the lack of firm scientific evidence, there is no clear basis for more regulation or for civil liability claims, and the societal benefits of modern, intensive production could well be as great or greater than any actual costs. Third, given the remaining scientific uncertainties, there are fierce differences of view about how serious these problems are, the degree to which they are caused by agricultural practices, and whether regulations of production practices are warranted. The American Farm Bureau Federation, the Fertilizer Institute, the National Cattleman's Association, the National Pork Producers Council, and a good many other producer groups fervently resist the notion that there are any substantiated connections among large-monoculture, large-scale animal confinement systems; the hypoxia zone; hydrogen sulfide-caused human neurological disorders; and antiobiotic-resistant bacteria. By contrast, most environmental organizations, sustainable agriculture organizations, and profamily farming groups believe that the connections are “practically undeniable,” to quote Dr. Kaye Kilburn, a University of Southern California professor and one of the most visible researchers working in the area of hog CAFOs and hydrogen sulfide air pollution (http://www.nytimes.com/2003/05/11/health/11HOGS.html).

Fourth, these pollution problems of modern agriculture involve bringing farm operations, especially larger ones, increasingly within the scope of the Clean Air Act and Clean Water Act—legislation that had previously been applied mainly to industrial corporations and municipalities. This shift of regulatory milieu raises the stakes involved in development of policy responses. Fifth, there do not appear to be any magic-bullet technologies that are compatible with large-scale agricultural systems and that ameliorate either problem sufficiently to mollify activists. Finally, there are no obvious incentives that would address the problem and that would be acceptable to producers and the public, or at least the activist public. Large-scale farmers, for example, reject the notion of making any major shifts in production technology, whereas activist groups' goal typically is not only to abate air and water pollution by ultimately to decisively reverse the industrialization of American agriculture.

ROLES FOR PUBLIC RESEARCH

Another dilemma common to problems such as hypoxia, nitrogen sulfate emissions, and so on concerns the roles that publicly funded research should play. Many societal costs of agriculture may be reduced through development of abatement or other technologies, and in many instances, there are rationales for public research institutions to participate in developing these technologies (e.g. Zahn et al., 2001). Public research that ameliorates a significant societal cost of modern large-scale agriculture has an obvious efficiency rationale, as well as an obvious appeal to large commercial farmers, agribusinesses, and leaders of other agricultural institutions. (This is not to presume, of course, that all societal costs of modern agriculture are accounted for by the largest farms. There is a tendency, however, for increases in farm scale to make certain externalities such as environmental degradation more likely. It is also the case that the social costs created by very large, industrial-type farms are most likely to be of concern to the public.) But doing so also raises troublesome ethical questions of whether the public agricultural research system should in effect subsidize the types of producers that are externalizing major costs onto society, whereas the research system by and large eschews research to benefit smaller or medium-sized producers whose practices are more environmentally benign and less problematic socially.

Busch (1994) has written persuasively that public agricultural research is at an impasse partly because of the continued hegemony of the notion that its key goal is to increase productivity (Chrispeels and Mandioli, 2003; see also the perceptive historical and ethical reflection on the “productivist paradigm” by Thompson, 1995). Busch's objection to productivity being the unstated but pervasive bottom line of public research is that the conditions are no longer propitious for widespread public acceptance of productivity increase as the understood goal for publicly supported research. This is partly because post-World War II productivity increases exacted unrecognized and uncompensated societal costs, as has been noted in this paper, so that part of the productivity success story was somewhat illusory. But a more important shortcoming of the productivity raison d'eêtre of (domestic) agricultural research is that the advanced industrial countries are mired in a persistent crisis of global overproduction, which can only be exacerbated by output increase. (Productivity and output increase are, of course, not coterminous, although in practice, they bear a close biophysical and ideological relationship.) The global impasse over agricultural trade, export subsidies, and domestic agricultural support suggests that this overproduction situation will continue indefinitely. Productivity increase thus tends to marginalize the very groups, mainly farmers, who are the ostensible beneficiaries of agricultural research. In addition, “true productivity increase,” which would imply simultaneously increased input-output, allocative, and “natural-capital” efficiency, is premised on the existence of input prices that provide realistic signals as to the actual scarcity of inputs. For Busch, inexpensive publicly subsidized irrigation water, the fact that prices for chemical inputs do not reflect the costs of agricultural pollution, the unpaid costs of depletion of natural resources, and loss of ecosystem services involved in agricultural production are factors that are currently not reflected in factor and product markets in agriculture. With such a distorted system of price signals, agricultural technologies based on these input prices will lead to distortions in resource allocation—and to the illusion of productivity increase. He also stresses that the United States currently lacks a comprehensive national data system to monitor the social and environmental costs and benefits—particularly the additions to and deletions from the natural capital and ecosystem services “stocks”—of agriculture. The lack of research on the societal costs of agriculture and the corresponding lack of an information system on these costs not only makes it more likely that these costs will be ignored, but it also makes it more likely that technical disagreements will make the regulatory and policy-making processes more politicized, arbitrary, and ineffective than they need to be (Busch, 1994).

TOWARD SATISFICING, PRECAUTIONARY SOLUTIONS

In this paper, I have argued that there are scientific, ethical, political, and practical reasons why it is difficult to implement programs to internalize the societal costs of food and agricultural production. Which way forward? I offer four modest proposals, with full awareness of ethical complexities and uncertain political realties.

First, there is abundant evidence, albeit of a precautionary nature, that the relative inexpensiveness of fertilizers and biocides contributes to heavy levels of use and to a greater or lesser amount of off-site movement of nutrients, toxins, and soil (Matson et al., 1997). Thus, there is a sound precautionary rationale to discourage farming practices that tend to increase the off-site movement of these materials. One important place to start is to remove state tax exemptions on agricultural chemicals. A modest federal tax on these chemicals would at least begin to discourage profligate use of these inputs. Austria, Finland, Norway, and Sweden already tax fertilizers and/or pesticides, and similar programs have been on the books in Iowa, Nebraska, and Wisconsin. The current Norwegian policy, for example, involves a 15% tax on N, P, and K. These agri-environmental taxes would be consistent with a market-oriented policy and would be cost effective from a government fiscal point of view. A second precautionary policy would be to move toward a consensus that agricultural production units should be subject to the same environmental and human safety standards that other non-farm businesses must comply with. Doing so is consistent with fairness and would ensure that farm enterprises are neither exempted from accepted regulatory standards nor penalized for being unwanted rural land uses. Third, U.S. federal investments in wetland restoration through the Farm Bill should be expanded. Wetland restoration has strong justification on biodiversity and ecosystem services grounds, and wetland restoration almost certainly would enhance water quality, flood prevention, and a range of other ecosystem services. Appropriately designed programs would be income-neutral if not beneficial for producers.

Fourth, given the likelihood that massive federal farm program payments will continue for the indefinite future, serious attention should to be given to implementing “multifunctionality policies” (Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development, 2001). Multifunctionality (see also Dundon, 2003) is the notion that, in addition to production of food and fiber (and other marketable goods), agriculture has a number of other, mostly non-commodity, outputs (e.g. environmental protection, flood control, ecosystem services, maintenance of landscape or habitat, rural development, maintenance of agricultural heritage or culture, and so on). Non-commodity outputs, because they do not have a market price, tend to be underproduced. Multifunctionality policy would involve fundamentally changing the rationale and procedure behind subsidies of farmers. Instead of farmers receiving payments with no “strings attached” or no performance requirement, a multifunctionality payment system would compensate farmers for noncommodity outputs they already provide and for additional services to society that they could and should provide (Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development, 2001). Thus, farmers would cease being paid for overproducing farm commodities and instead would be paid for providing socially valuable but non-marketable goods and services (Dundon, 2003).

Each of these four suggestions involves satisfying rather than optimizing, which is probably the best that can be done given the low level of data and information on the societal costs and benefits of food and fiber production. Each has a moderate price tag, and in aggregate, they would probably be revenue neutral for governments. Each is low risk; it is almost certain that each would do some good, and there is almost no chance that the outcomes of any of the four would entail higher societal costs of agriculture in the future. Each would deal with multiple social costs of agriculture.

A NEW DIRECTION FOR AGRICULTURAL RESEARCH

Looking to the future, we can observe two related but contradictory trends. On one hand, the past 20 or so years have led to justifiable scrutiny of the efficiency and efficacy of government programs. This has led to healthy skepticism whenever new public policies are being considered. On the other hand, the “rationalization capacity” of the government is declining due to budget cuts, deregulatory zeal, and the demonization of government—even by people who work therein! The United States has also become a global outlier among developed nations in its policies toward trade, agriculture, foreign aid, the global environment, and many other policy areas. One of the difficulties of U.S. government “going it alone” and isolation is that we are invariably unwilling or unable to take advantage of new public policy models being developed elsewhere. It would appear that in most respects, some European countries are far ahead of the United States in developing policies to internalize the societal costs of food and fiber production. In 1998, the EU, for example, banned antibiotics used in human medicine from use as growth promoters in livestock production, and several European countries have enacted levies on fertilizers and or pesticides, although these levies have arguably been too modest to affect their use to a significant degree. (The European Fertilizer Manufacturers Association is no doubt correct that levies on fertilizer would benefit livestock producers over arable farmers because of the access of the former to animal manures [http://www.efma.org/Publications/EUBook/Section03.asp], and thus on both environmental as well as equity grounds, levies on chemicals should be accompanied by incentives that discourage air and water pollution from livestock confinement facilities.) In sum, there is much going on across the Atlantic that would be of great assistance to the United States in responding to the dilemmas of organizing agriculture in an increasingly metropolitan and resource-scarce world.

But as much as there is to admire about some of the approaches being implemented in parts of Europe, neither side of the Atlantic is aggressively prioritizing research to decisively reverse the long-term trends of declines in the efficiency of the use of nitrogen, phosphorous, and water in western and world agricultures. It is particularly difficult, but particularly crucial, to control the fate of N in cropping systems. Tilman et al. (2002) has illustrated in global aggregate terms the magnitude of the problem by showing the adverse global trend in nitrogen use efficiency (for nitrogen-use efficiency data for maize, rice, and wheat in the developed and developing countries, see Cassman et al., 2002; for data on nitrogen increasing strategies [in the conventional sense], which have little relationship to the integrated research, regulatory, and incentive-based systems that are so sorely needed, see Matson et al., 1998). There needs to be research on closing nitrogen and phosphorous cycles rather than on patching up the problems caused by farmers and production systems that do not, and cannot, do so. There also need to be more integrative approaches such as the development of biota and management systems for commercial-scale agroforestry and development of the techniques, tools, and policies for landscape-scale management of multifunctional agriculture. Agro-ecology should become a research priority comparable with biotechnology. Functional genomics (and related techniques such as marker-assisted selection) should be harnessed for the development of locally adapted cultivars and other biota that increase the natural resource efficiency of production and close nitrogen and phosphorus cycles rather than largely to the pursuit of genetic traits aimed at further intensification. The answers to these problems do not lie solely in the area of research, but research will clearly be critical in developing innovative solutions.

References

- Busch L (1994) The state of agricultural science and the agricultural science of the state. In A Bonanno, L Busch, WH Friedland, L Gouveia, E Mingione, eds, From Columbus to Con-Agra. University Press of Kansas, Lawrence, pp 69-84

- Cassman KG, Doberman A, Walters DT (2002) Agroecosystems, nitrogen-use efficiency, and nitrogen management. Ambio 31: 132-140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chrispeels M, Mandioli DF (2003) Agricultural ethics. Plant Physiol 132: 4-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Constance DH, Kleiner AM, Rikoon JS (2003) The contested terrain of swine production: deregulation and reregulation of corporate farming laws in Missouri. In J Adams, ed, Fighting for the Farm. University of Philadelphia Press, Philadelphia, pp 75-95

- Constanza R, d'Arge R, de Groot R, Farber S, Grasso M, Hannon B, Limburg K, Naeem S, O'Neill RV, Paruelo J et al. (1997) The value of the world's ecosystem services and natural capital. Nature 387: 253-260 [Google Scholar]

- Cranor CF (2003) How should society approach the real and potential risks posed by new technologies? Plant Physiol 133: 3-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dailey G, editor (1997) Nature's Services. Island Press, Washington, DC

- Danbom DB (1995) Born in the Country. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore

- Donham KJ, Thorne PS, Breuer GM, Powers W, Marquez S, Reynolds SJ (2002) Chapter 8. In Iowa State University and the University of Iowa Study Group, editors, 2002 Concentrated Animal Feeding Operations Air Quality Study. College of Public Health, University of Iowa, Iowa City, pp 164-183

- Dundon S (2003) Agricultural ethics and multifunctionality are both unavoidable. Plant Physiol 133: 427-437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaskell G, Bauer M, Durant J, Allum N (1999) Worlds apart: the reception of GM foods in the United States and Europe. Science 285: 384-387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howarth RW, Billen G, Swaney D, Townsend A, Jaworski N, Lajtha K, Downing JA, Elmgren R, Caraco N, Jordan T et al. (1996) Regional nitrogen budgets and riverine N, P fluxes for the drainages to the North Atlantic Ocean: natural and human influences. Biogeochemistry 35: 75-139 [Google Scholar]

- Iowa State University and the University of Iowa Study Group, editors (2002) Concentrated Animal Feeding Operations Air Quality Study. College of Public Health, University of Iowa, Iowa City

- Juma C (2000) Science, New Foods, and Public Policy: Using the Concept of Substantial Equivalence. Center for International Development, Harvard University. http://www.botanischergarten.ch/debate/Juma.pdf (May 7, 2003)

- Lacy WB (2000) Agricultural biotechnology, socioeconomic issues, and the fourth criterion. In TJ Murray and M Mehlman, eds, Encyclopedia of Ethical, Legal and Policy Issues in Biotechnology. John Wiley & Sons, New York, pp 76-89

- Lyson TA (1986) Who cares about the farmer? Apathy and the current farm crisis. Rural Sociol 51: 490-502 [Google Scholar]

- Matson PA, Parton WJ, Power AG, Swift MJ (1997) Agricultural intensification and ecosystem properties. Science 277: 504-509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matson PA, Naylor R, Ortiz-Monasterio I (1998) Integration of environmental, agronomic, and economic aspects of fertilizer management. Science 280: 112-116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millstone E, Brunner E, Mayer S (1999) Beyond “substantial equivalence.” Nature 401: 525-526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (1993) Safety Evaluation of Foods Derived by Modern Biotechnology: Concepts and Principles. Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development, Paris

- Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (2001) Multifunctionality: Towards an Analytical Framework. Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development, Paris

- Pearce D (1998) Auditing the earth: the value of the earth's ecosystem services and natural capital. Environment 40: 23-28 [Google Scholar]

- Princen T (2002) Distancing: consumption and the severing of feedback. In T Princen, M Maniates, K Conca, eds, Confronting Consumption. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA, pp 103-131

- Thompson PB (1995) The Spirit of the Soil: Agriculture and Environmental Ethics. Routledge, London

- Thompson PB (1998) Agricultural Ethics. Iowa State University Press, Ames

- Tilman D, Cassman KG, Matson PA, Naylor R, Polasky S (2002) Agricultural sustainability and intensive production practices. Nature 418: 671-677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (1996) Swine CAFO Odors. Region 6. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Dallas

- van den Belt H (2003) Debating the precautionary principle: “guilty until proven innocent” or “innocent until proven guilty.” Plant Physiol 132: 1122-1126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vitousek PM, Aber J, Howarth RW, Likens Howarth, Matson PA, Schindler DW, Schlesinger WH, Tilman GD (1997) Human alteration of the global nitrogen cycle: causes and consequences. Issues Ecol 1: 737-750 [Google Scholar]

- Vitousek PM, Howarth RW (1991) Nitrogen limitation on land and in the sea: How can it occur? Biogeochemistry 13: 87-115 [Google Scholar]

- Wells M (2003) The contingent creation of rural interest groups. In J Adams, ed, Fighting for the Farm. University of Philadelphia Press, Philadelphia, pp 96-110

- Zahn JA, Tung AE, Roberts BA, Hatfield JA (2001) Abatement of ammonia and hydrogen sulfide emissions from a swine lagoon using a polymer biocover. J Air Waste Management Assoc 51: 562-573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]