Abstract

Objective

Neuro-cognitive deficits are common and serious consequences of obstructive sleep apnea (OSA). Currently, the gold standard treatment is continuous positive air pressure (CPAP) therapy, although the clinical responses to this intervention can be variable. This study examined the effect of one night of CPAP therapy on sleep-dependent memory consolidation, attention and vigilance as well as subjective experience.

Methods

15 healthy controls and 29 patients with obstructive sleep apnea of whom 14 underwent a full night CPAP titration completed the Psychomotor Vigilance Test (PVT) and motor sequence learning task (MST) in the evening and the morning after undergoing overnight polysomnography. All participants also completed subjective evaluations of sleep quality.

Results

Participants with OSA showed significantly less overnight improvement on the MST compared to controls without OSA, independent of whether or not they had received CPAP treatment, while there was no significant difference between the untreated OSA and CPAP-treated patients. Within the OSA group, only those receiving CPAP exhibited faster reaction times on the PVT in the morning. Compared to untreated OSA patients, they also felt subjectively more rested and reported that they slept better.

Conclusion

Our results demonstrate an instant augmentation of subjective experience and, based on PVT results, attention and vigilance after one night of CPAP, but a lack of an effect on offline sleep-dependent motor memory consolidation. This dissociation may be explained by different brain structures underlying these processes some of which might require longer continued adherence to CPAP to generate an effect.

Keywords: obstructive sleep apnea, sleep-dependent memory, CPAP, PVT

Introduction

Disorders of breathing during sleep are a major health problem; in particular obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) has been associated with important health consequences including an increased risk for cardiovascular 2–7 and cerebrovascular disease 8, 9, mortality 6, 10–15 and cognitive impairment, independent of daytime sleepiness. 16–22

The majority of studies assessing cognition show spared global cognitive functioning and basic language functions. 23–25 In contrast, most OSA patients are impaired on testing of vigilance i.e. tests that require sustained attention for a period of time, a finding which has important implications for the ability to drive and for general occupational functioning. 26–29 It is therefore not surprising that OSA has been linked to an increased risk of motor vehicle accidents and thus, if left untreated, not only imposes a health risk to the individual, but also to those around them.

Continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) treatment restores normal respiration during sleep, thereby improving sleep architecture and is considered the first line of treatment for OSA.30,1 Nightly use of CPAP can markedly reduce sympathetic activity and blood pressure and thus decrease the risk of mortality. 31, 32 Studies examining cognitive function pre- and post- CPAP treatment have indicated selective improvement in neuropsychological deficits after CPAP-treatment. 33–38 The results have been difficult to interpret due to variations in hypoxia, apnea hypopnea index (AHI) and cognitive areas tested. Some investigators have also speculated that CPAP only improves deficits related to sleep fragmentation but not due to hypoxemia 38, with which there may be irreversible injury to certain brain regions. 39

Sleep can affect learning and memory in a number of ways. Specific sleep dependent memory tasks have been used with increasing popularity to assess the dynamic processes during which initial, labile memory representations are converted (either stabilized or enhanced) into more permanent ones. But thus far few studies have investigated sleep-dependent memory processes in patients with obstructive sleep apnea.40, 41 Given that the precise domains of sleep-dependent memory impairment present in OSA have not been sufficiently studied, important questions remain concerning their reversibility with CPAP treatment.

Several studies have demonstrated that the motor sequence task shows a robust enhancement of performance after a night of sleep, but not after an equivalent time spent awake.42, 43 We recently published a study, in which we demonstrated that memory consolidation for this procedural motor skill task is affected by OSA even in young people with relatively mild disease, and that this effect is not the result of a difference in attention or vigilance.40 Thus, given the significance of sleep-related processes for improvement on this task, we sought to examine how quickly patients with OSA could recover from the effects of their disease on this form of sleep-dependent memory consolidation.

Patients with OSA often report a major subjective improvement after using CPAP for the first time. The aim of this study was thus to delineate the effect of first-time experience with CPAP on subjective experience, measures of vigilance, and sleep-dependent procedural motor memory consolidation.

Methods

The first 44 patients, who underwent either a diagnostic polysomnography or a CPAP titration study at Brigham and Women’s Hospital Sleep Disorders Laboratory, agreed to participate and met inclusion criteria were enrolled in the study. Post-PSG, participants were subdivided into 3 groups: 1) Healthy controls (Control group), 2) Patients, who were found to have obstructive sleep apnea, but did not undergo any treatment intervention (OSA group) and 3) Patients with OSA, who were CPAP-naive and underwent a whole night with continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP group). To qualify as healthy controls, participants had to have an apnea-hypopnea index less than 5/h, whereas an AHI of greater than 15/h was required for the OSA group.

Exclusion criteria

Participants were excluded if they (1) were found to have a periodic limb movement index of > 15/h based on their PSG, (2) had another diagnosed sleep or circadian disorder, (3) had a history of alcohol, narcotic, or other drug abuse, (4) had a history of a medical, neurologic or psychiatric disorder (other than OSA and treated hypertension) that could influence excessive daytime sleepiness, (5) used medications known to have an effect on sleep and daytime vigilance (e.g., psychoactive drugs or medications, sedatives or hypnotics, including SSRIs), or (6) were left-handed.

Study design

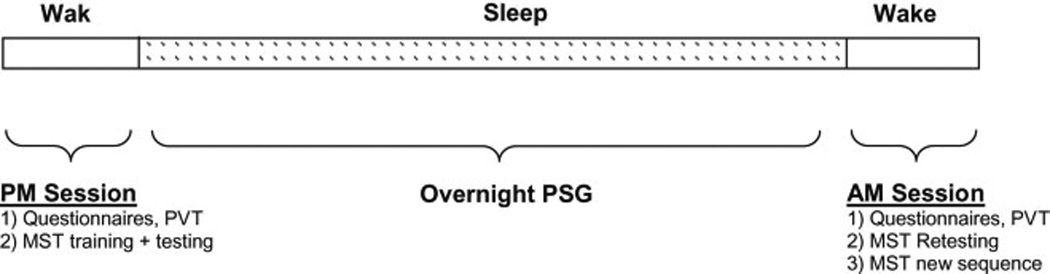

All participants performed a 5 minute version of the psychomotor vigilance task (PVT) and then trained on the motor sequence task (MST) in the evening between 8 and 9 PM.44, 45

The MST requires repeated typing of a 5-digit sequence on a standard computer keyboard (e.g., 4-1-3-2-4) with their non-dominant (left) hand. The specific sequence to be typed is displayed on the computer screen at all times. Typing is performed in 30-second trials separated by 30-second rest periods. Training and retest each included 12 trials. Following training, participants spent the night in the laboratory and underwent standard sleep recording. The following morning subjects were woken up and then repeated the PVT and were tested on the MST. After a 10 minute break, they trained on a new MST sequence. Since learning the motor sequence task is sequence specific, there is no transfer of learning to new sequences. 46 This study design allowed us to compare learning in the evening and morning, to confirm that there was no general time-of-day effect on motor sequence performance, and that overnight improvement reflected specific enhancement of performance on the previously learned. MST sequences were counterbalanced for evening and morning training across all participants within groups to control for any order effect. The main performance measure for the MST is the number of correctly typed sequences per 30-second trial, thereby reflecting both speed and accuracy.

The PVT is an objective measurement of sustained attention and reaction time and has been shown to be sensitive to sleep deprivation, partial sleep loss, and circadian variation in performance efficiency. 47 As such it allowed us to verify that differences in overnight improvement on the MST were related to differences in overnight memory consolidation, and not to differences in attention. In this task, subjects push a button as fast as they can whenever they see a small (3 mm high, 4 digits wide) LED millisecond clock begin counting up from 0000. Pressing the button stops the digital clock, allowing the subject 1.5 seconds to read the reaction time (RT). The inter-stimulus interval on the task varies randomly from 2 to 10 seconds. The duration of the task can be either 5 – as in our case - or 10 minutes. 48 Participants also completed subjective evaluations of sleep quality in the morning. These questions included 2 categories: 1) “Would you describe your sleep last night as (a) better, (b) same (c) worse than usual” and 2) a yes-no question “Do you feel rested this morning?”. In addition, they filled out a questionnaire asking them about their previous typing experience.

Polysomnography

Standard overnight PSG recording and data interpretation were performed in accordance with the American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM) scoring manual. 49, 50 This approach included standard electroencephalogram (EEG) leads (F3, F4, C3, C4, O1, and O2), as well as bilateral electrooculogram (EOG), submental electromyogram (EMG), bilateral anterior tibialis electromyogram (EMG), and standard electrocardiogram (ECG) electrodes. Nasal/oral airflow (thermistor), nasal pressure (Validyne transducer), chest plus abdominal wall motion (piezo electrodes) and oxygen saturation were also recorded.

All studies were scored by a registered PSG technologist, blinded to subject performance. In particular, hypopneas required a clear (discernable) amplitude reduction of a validated measure of breathing during sleep, and were associated with either an oxygen desaturation of > 3% or an arousal lasting ≥ 10 sec.

Arousals were scored visually according to the AASM manual scoring criteria, which require an abrupt shift of EEG frequency including alpha, theta and/or frequencies greater than 16 Hz (but not spindles) that last at least 3 seconds preceded by 10 seconds of stable sleep.

PSG Data Analysis

PSG data were preprocessed and analyzed using BrainVision Analyzer 2.0 (BrainProducts, Munich Germany). Artifacts were automatically detected and removed and EEG data were filtered at 0.5–35Hz. Artifact rejection was confirmed by visual inspection. Power spectral density (µV2/Hz) was calculated by Fast Fourier Transform (FFT), applying a Hanning window to 5s epochs of N2 and N3 sleep with 50% overlap.

Based on previous studies, spindle analysis (number and density) was performed from the C3 and C4 location for stage 2 sleep manually and by using a wavelet-based algorithm. Data were pre-processed and analyzed using BrainVision Analyzer 2.0 and MatLab R2009b (The MathWorks, Natick MA) as described by Wamsley et al. 51

Statistical analysis

Variables were compared between healthy controls and OSA patients with and without CPAP. One way ANOVAs were performed to compare demographic and PSG-derived sleep data including sleep spindle analyses. Subjective sleep quality evaluations were analyzed using chi square tests.

Overnight MST improvement was calculated as percent change in performance speed (correct sequences per 30-sec trial) for initial and plateau improvement taking into account the characteristic performance curves over the 12 training trials and 12 test trials [initial improvement = percent increase in performance from the last three training trials in the evening to the first three test trials in the morning and plateau improvement = percent improvement from the last 6 training trials in the evening to the last 6 test trials in the morning].

Percentage values for improvement across the three groups were compared by applying one-way ANOVAs and post-tested with Tukey’s HSD (honestly significant differences) tests.

Statistical analysis was performed using JMP Version 10 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). A p-value of <0.05 was considered significant. Variability is expressed as standard deviation (S.D.).

Sample Size Justification

For the motor sequence task, published results indicate an effect size of 1.64.44 The required sample size to achieve a power of 80% with the alpha-level set to 0.05, is an n = 14 for a two-tailed test and n = 12 for a single-tailed test. All groups had n ≥ 14.

Ethics Statement

All participants provided written informed consent. The study was approved by the Partners’ Institutional Review Board.

Results

Demographic and sleep variables

Demographic and sleep characteristics are shown in Table 1. Among the 3 groups, there was no significant difference in age or BMI. In addition, measures of sleep architecture including total sleep time, sleep efficiency and sleep stage distribution were very similar.

Table 1.

Group demographics and sleep characteristics.

| CPAP (n=14) |

OSA (n=15) |

Control (n=15) |

P- value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 44.4 ± 11.1 | 43.3 ± 13.0 | 37.3 ± 10.5 | 0.19 |

| BMI (kg/m²) | 32.0 ± 5.4 | 30.2 ± 5.5 | 27.6 ± 5.8 | 0.12 |

| TST (min) | 332.3 ± 57.7 | 308.5 ± 51.9 | 345.7 ± 27.9 | 0.11 |

| Sleep Efficiency (%) | 84.3 ± 8.5 | 82.5 ± 11.5 | 86.0 ± 10.7 | 0.61 |

| Sleep stages: | ||||

| Stage N1 (%) | 8.0 ± 4.0 | 8.6 ± 4.4 | 8.3 ± 4.8 | 0.66 |

| Stage N2 (%) | 60.8 ± 10.0 | 63.4 ± 8.3 | 58.5 ± 8.42.2 | 0.30 |

| Stage N3 (%) | 11.6 ± 13.3 | 11.9 ± 10.5 | 15.2 ± 11.73.0 | 0.71 |

| REM (%) | 19.7 ± 3.4 | 16.1 ± 7.9 | 18.0 ± 7.82.0 | 0.37 |

| AHI (events/h) | 5.9 ± 4.6 | 23.9 ± 10.0 *,§ | 3.5 ± 1.30.4 | < 0.0001 |

| Oxygen nadir (%) | 90.7 ± 3.3 | 86.4 ± 4.2 *,§ | 91.4 ± 2.6 | < 0.0001 |

| Arousal index (A/h) | 17.2 ± 5.6 | 25.6 ± 12.7 * | 18.3 ± 7.3 | 0.03 |

Values are presented as mean ± S.D. P-values represent results of ANOVA across the three groups.

Asterisks represent post-hoc comparisons using Tukey HSD tests: * (CPAP/OSA);

(CPAP/Control);

(Control/OSA)

As expected, untreated OSA patients had a significantly higher AHI and arousal index as well as the lowest oxygen nadir compared to healthy controls and OSA patients treated with CPAP.

Performance measures of the Motor Sequence Task (MST)

Evening training

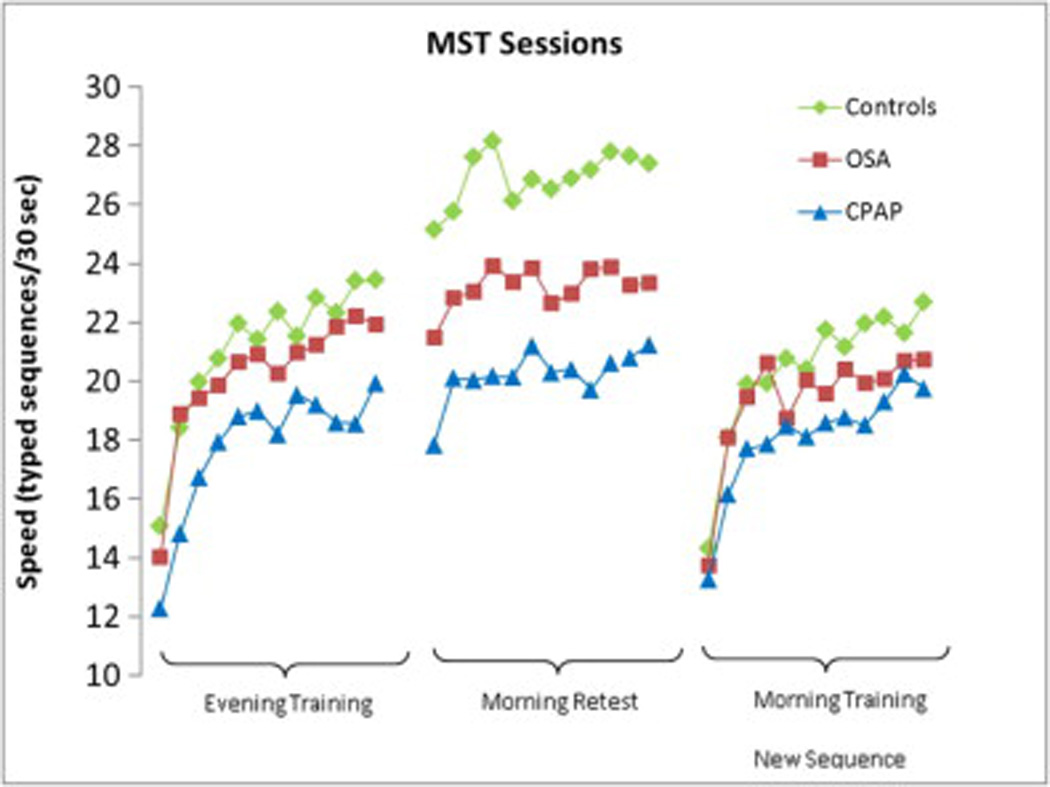

Though healthy controls were overall able to type more sequences throughout the 12 evening training trials, this difference was not significant. All three groups showed similar practice-dependent improvement across the 12 evening training trials (percent increase in performance from the first 2 trials to the last 3 trials; ANOVA, p=0.291). (Fig 2)

Figure 2.

Trial-by trial MST performance across groups

Overnight Improvement

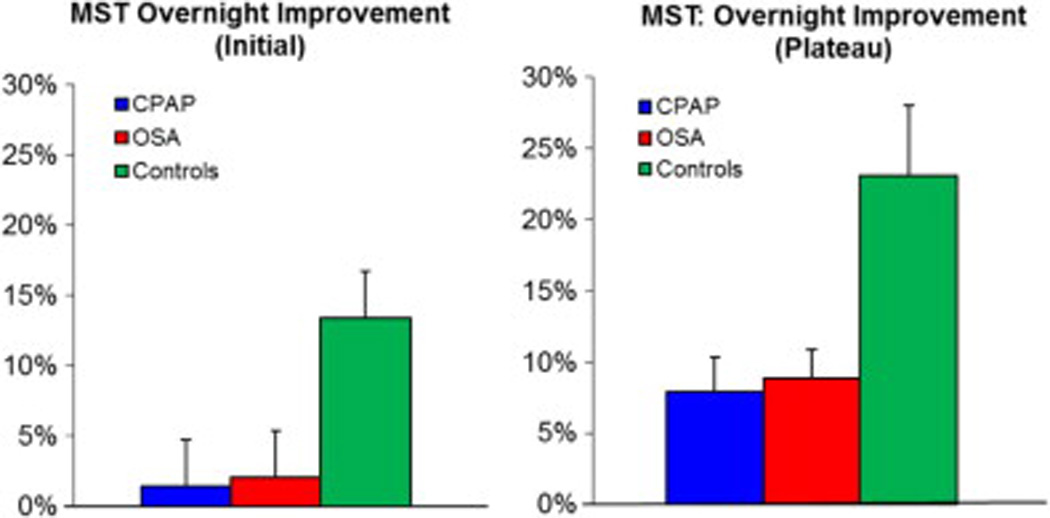

Independent of whether they received treatment, OSA participants (both, OSA and CPAP groups) showed significantly less initial overnight improvement on the MST compared to healthy sleepers (OSA 2.0 ± 13.0% [S.D.], CPAP 1.4 % ± 12.6%, Controls 13.4% ± 13.5%; F=4.1, df=2, p=0.02 [ANOVA across groups]; Fig 3A). Post-hoc Tukey HSD comparisons revealed p=0.05 for Controls compared to OSA patients and p=0.04 for Controls compared to the CPAP group. No significant differences were seen between the OSA and CPAP groups (p=0.99). Similar results were found for comparisons of overnight plateau improvement (OSA 8.9% ± 7.8%, CPAP 8.0% ± 9.1%, Controls 24.0% ± 19.3%; F=6.0, df=2, p=0.005 Fig 3B [ANOVA across groups]; Fig 2B). Here, post-hoc comparisons revealed significant differences between Controls and OSA patients (p=0.02) and between Controls and the CPAP group (p=0.01), but no significant difference between the OSA and CPAP groups (p=0.98). Importantly, the level of performance at the end of the evening training session (average of last 3 trials) did not correlate with the amount of overnight improvement (Pearson correlation r²=0.05, p= 0.14).

Figure 3.

MST Overnight Improvement

Changes in PVT reaction time between evening and morning

Morning Training

After completing the MST testing in the morning, all participants were trained on a novel sequence in order to control for circadian influences on performance. No significant within-group differences in performance were found between the two training sequences (evening versus morning; all p’s > 0.28). Thus, circadian influences do not explain the overnight changes in performance between groups.

Sleep spindles

Previous research has shown an association between motor sequence learning and sleep spindles during stage 2 (N2) sleep. 52, 53 Based on these reports, sleep spindles were assessed during stage 2 (N2) sleep only. A significant difference among the three groups in total number of sleep spindles as well as in spindle density was observed at both central electrodes (C3, C4). The most notable difference was seen over the C3 electrodes where CPAP-treated OSA patients demonstrated significantly higher total number of sleep spindles (p= 0.01 [ANOVA across groups], p= 0.01 [CPAP vs. OSA]) and central sleep spindle density (p= 0.008 [ANOVA across groups], p= 0.007 [CPAP/OSA]) compared to Controls and untreated OSA patients. Significant differences were also present over C4 (p= 0.03 [ANOVA, C4 total number], p= 0.02 [ANOVA, C4 density]). Post-hoc Tukey HSD test demonstrated significant differences again only for CPAP/OSA group comparisons (p= 0.02 [C4 total number], p= 0.01 [C4 density]). (Table 2)

Table 2.

Sleep Spindles

| CPAP | OSA | Control | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spindles –C3 | 435.9 ± 149.4* | 318.5 ± 135.8 | 377.4 ± 75.3 | 0.01 |

| Spindles – C4 | 420 ± 162.2* | 310.9 ± 123.8 | 400.7 ± 85.8 | 0.03 |

| Spindle density C3 | 2.3 ± 1.0 * | 1.6 ± 0.5 | 1.9 ± 0.3 | 0.01 |

| Spindle density C4 | 2.2 ± 1.0 * | 1.6 ± 0.5 | 2.0 ± 0.4 | 0.02 |

Values are presented as mean ± S.D. P-value represents results of ANOVA across the three groups.

Asterisks represent post-hoc comparisons using Tukey HSD tests: * (CPAP/OSA)

Contrary to previous reports, we did not find any correlation between total number of central spindles or central spindle density and overnight MST improvement for any of the groups.

Measures of alertness

PVT Performance

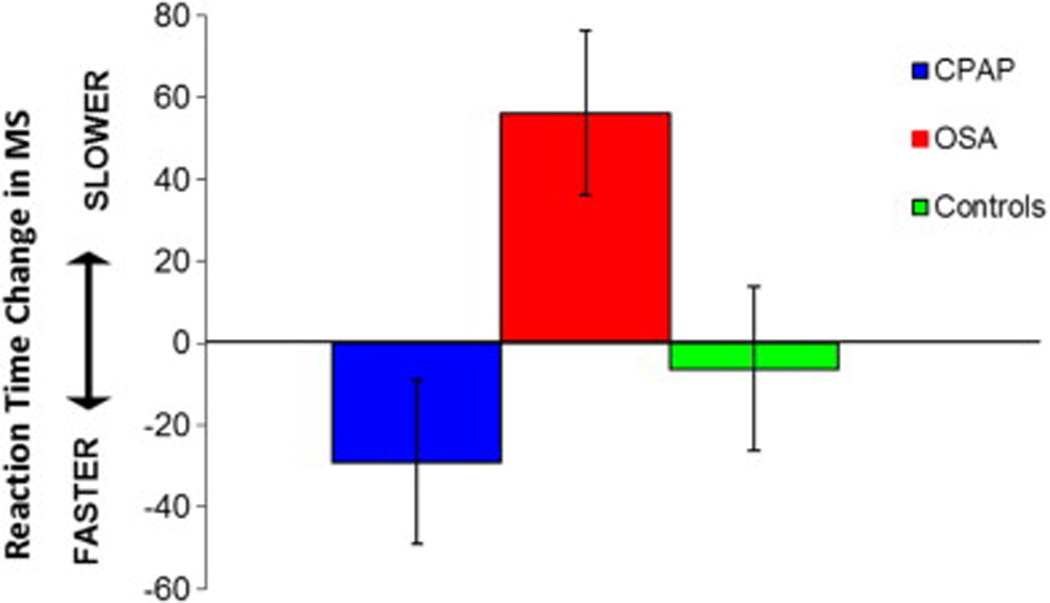

In the evening, the mean reaction time for baseline PVT performance was 387.9 ± 121.4 ms. (lapses [RT>500ms] = 9.0 ± 11.5) for OSA patients without CPAP and 440.0 ± 142.6 ms. (lapses = 11.6 ± 13.1) for OSA patients on CPAP, compared to a mean reaction time of 409.7 ± 125.3 ms. (lapses = 8.1 ± 11.9) for controls (p = 0.56 [ANOVA across all groups]).

The control group showed very similar PVT performance in the morning compared to the evening (p= 0.88). Among all the OSA patients, only those who received a full night on CPAP (CPAP group) exhibited faster reaction times on the PVT in the morning than those who did not (OSA group) (p=0.04 [OSA/CPAP]). (Figure 4)

Figure 4.

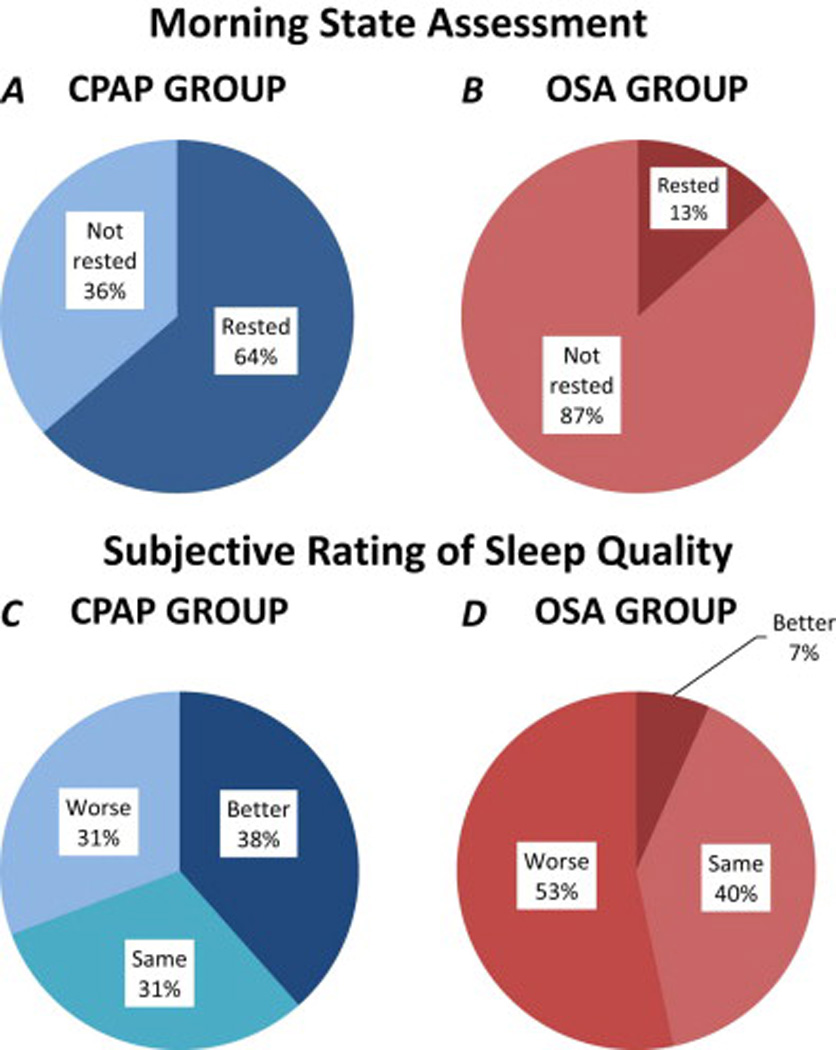

Subjective Sleep Ratings

Subjective ratings

Compared to untreated OSA patients, more full night CPAP participants reported both feeling more rested (64% vs. 36%, p= 0.005) and having improved sleep quality (38.5% vs. 6.7%, p= 0.04) the next morning (Fig 4 A–D). We did not find any correlations between subjective ratings and PVT performance or overnight MST improvement in any of the three groups.

Discussion

Previous studies have indicated selective improvement in neurocognitive deficits after CPAP treatment. 37 54 However, little is known about the effect of CPAP on sleep-dependent memory consolidation.

Our study shows resolution of sleep disordered breathing during the first night of treatment with CPAP, including oxygen saturations and arousal indices similar to healthy controls. Those OSA patients who experienced their first night on CPAP demonstrated an instant improvement in attention and vigilance based on PVT results the next morning. They also felt subjectively more rested and reported improved sleep quality. Despite this finding, however their overnight improvement on the MST remained virtually identical to that seen in untreated OSA patients and distinctly poorer than in healthy controls. Therefore, even though patients, who received CPAP reported that they felt they had slept better and felt more rested, they failed to show the normal memory benefits from the night’s sleep.

Our results demonstrate that acute recovery after one night of CPAP is limited and selective and confirm that improvement of cognitive deficits caused by OSA depends on multiple likely intertwined mechanisms. Previous studies investigating the effects of CPAP on cognitive recovery have applied CPAP exposure duration from one week 55, to up to 12 months 56. The study by Bardwell et al. investigated the effectiveness of one week CPAP treatment versus placebo-CPAP on a board battery cognitive outcomes and was able to demonstrate that CPAP improved overall cognitive functioning, but not in any specific domain tested. In particular only one of the 22 neuropsychological tests scores (Digit Vigilance—Time) showed significant changes specific to CPAP treatment. Munoz et al, investigated the long-term use of CPAP and demonstrated that a significant improvement in somnolence and vigilance was already evident after three months of treatment and continued to persist after 12.1 months. On the other hand, their study results also showed that long-term use of CPAP does not normalize the levels of depression and anxiety.

The present study is the first study to investigate the effect of the first night on CPAP and the results provide compelling evidence that improvement in some cognitive areas may already be present after one day of treatment.

While many cognitive areas improve after CPAP, there have also been some reports of persistent deficits after continued use of CPAP, which have included deficits attributable to frontal lobe function such as executive function, short-term memory, planning abilities, but also manual dexterity and psychomotor function.38, 57

It is therefore likely that the sensitivity to the effects of CPAP treatment may not only depend on the duration of treatment and nightly compliance, but also to the specific cognitive areas tested und the recoverability of their underlying brain structures.

Thus, whether sleep-dependent memory consolidation processes can recover with continued adherence to CPAP remains unknown.

Sleep spindles are presumed to reflect experience-dependent activation patterns as part of the hippocampal–neocortical dialogue involved in the consolidation of new learning thus facilitating synaptic plasticity and also representing an index of the capacity for learning. 58, 59 Few studies have analyzed sleep spindles in patients with sleep-disordered breathing. Our findings confirm a reduction of sleep spindles in OSA patients compared to healthy controls.

In contrast, those in the CPAP group showed spindle numbers significantly higher than the OSA group and even the control group. Without spindle values from before CPAP interpretations of this finding remain speculative. Based on the link between sleep spindles and stability of sleep, one possible explanation might be, that the higher number of sleep spindles in the CPAP group could be interpreted as a recovery phenomenon in conjunction with the improvement of the sleep fragmenting nature of OSA. 60, 61

Contrary to the differences in sleep spindles, there were no significant differences in sleep architecture among the three groups. It is unclear why we do not see significantly poorer sleep architecture in the OSA group, despite their significantly higher AHI and arousal index, and lower oxygen nadir. It may simply reflect how well apnea patients can fall back asleep after these arousals. These findings replicate our previous study 40 where the extent of impairment of sleep-dependent consolidation correlated with number of arousals, but not other sleep parameters.

We acknowledge limitations to our study. Despite the limited sample size, we were still well-powered for our primary outcomes and do believe that we can draw meaningful conclusions from these data. Second, we studied a relatively young population compared to some prior studies, and our conclusions cannot be extended to older OSA patients. Further research will be required to determine the effects of various covariates such as age and gender on these outcomes. Third, in an effort to dissociate the subjective improvements in symptoms from the objective changes in neuro-cognitive function, we studied only a single night of CPAP. Thus, we cannot draw conclusions about the effects of longer-term therapy on sleep-dependent memory consolidation or whether the observed abnormalities are in fact irreversible. A related relevant factor is the duration of disease prior to diagnosis; however, this , parameter is notoriously difficult to estimate and thus we are unable to determine whether patients with long standing disease have less improvement in memory consolidation compared to those with more recent onset of disease.

Despite these limitations, we believe that our findings represent a useful addition to the literature, and help fuel additional research in this area.

Supplementary Material

Figure 1.

Schematic overview of the visit protocol

HIGHLIGHTS.

There are several aspects of our findings that make this study an important one:

First study to demonstrate the effect of the first night of CPAP

Varying effect of CPAP on subjective experience, vigilance, and memory consolidation

Evidence that cognitive recovery after one night of CPAP exposure is limited and selective

Improvement in some cognitive areas may already be present after that first night of treatment

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Dr. Erin Wamsley and Dr. Matthew Tucker for providing spindle analysis tools and their helpful advice.

This was not an industry supported study. The study was funded by NIH grant # K23HL103850 and American Sleep Medicine Foundation grant #54-JF-10.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Loredo JS, Ancoli-Israel S, Dimsdale JE. Effect of continuous positive airway pressure vs placebo continuous positive airway pressure on sleep quality in obstructive sleep apnea. Chest. 1999;116:1545–1549. doi: 10.1378/chest.116.6.1545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grunstein RR, Stenlof K, Hedner J, Sjostrom L. Impact of obstructive sleep apnea and sleepiness on metabolic and cardiovascular risk factors in the Swedish Obese Subjects (SOS) Study. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1995;19:410–418. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jennum P, Sjol A. Snoring, sleep apnoea and cardiovascular risk factors: the MONICA II Study. Int J Epidemiol. 1993;22:439–444. doi: 10.1093/ije/22.3.439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Newman AB, Enright PL, Manolio TA, Haponik EF, Wahl PW. Sleep disturbance, psychosocial correlates, and cardiovascular disease in 5201 older adults: the Cardiovascular Health Study. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 1997;45:1–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1997.tb00970.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Newman AB, Nieto FJ, Guidry U, et al. Relation of sleep-disordered breathing to cardiovascular disease risk factors: the Sleep Heart Health Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2001;154:50–59. doi: 10.1093/aje/154.1.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Newman AB, Spiekerman CF, Enright P, et al. Daytime sleepiness predicts mortality and cardiovascular disease in older adults. The Cardiovascular Health Study Research Group. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2000;48:115–123. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb03901.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shahar E, Whitney CW, Redline S, et al. Sleep-disordered breathing and cardiovascular disease: cross-sectional results of the Sleep Heart Health Study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;163:19–25. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.163.1.2001008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yaggi H, Mohsenin V. Obstructive sleep apnoea and stroke. Lancet neurology. 2004;3:333–342. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(04)00766-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yaggi HK, Concato J, Kernan WN, Lichtman JH, Brass LM, Mohsenin V. Obstructive sleep apnea as a risk factor for stroke and death. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2034–2041. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ancoli-Israel S, Kripke DF, Klauber MR, et al. Morbidity, mortality and sleep-disordered breathing in community dwelling elderly. Sleep. 1996;19:277–282. doi: 10.1093/sleep/19.4.277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kripke DF, Garfinkel L, Wingard DL, Klauber MR, Marler MR. Mortality associated with sleep duration and insomnia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59:131–136. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.2.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Manabe K, Matsui T, Yamaya M, et al. Sleep patterns and mortality among elderly patients in a geriatric hospital. Gerontology. 2000;46:318–322. doi: 10.1159/000022184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mant A, King M, Saunders NA, Pond CD, Goode E, Hewitt H. Four-year follow-up of mortality and sleep-related respiratory disturbance in non-demented seniors. Sleep. 1995;18:433–438. doi: 10.1093/sleep/18.6.433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rockwood K, Davis HS, Merry HR, MacKnight C, McDowell I. Sleep disturbances and mortality: results from the Canadian Study of Health and Aging. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2001;49:639–641. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2001.49125.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stone KL, Ewing SK, Ancoli-Israel S, et al. Self-reported sleep and nap habits and risk of mortality in a large cohort of older women. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2009;57:604–611. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.02171.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bonnet MH. Cognitive effects of sleep and sleep fragmentation. Sleep. 1993;16:S65–S67. doi: 10.1093/sleep/16.suppl_8.s65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Crenshaw MC, Edinger JD. Slow-wave sleep and waking cognitive performance among older adults with and without insomnia complaints. Physiol Behav. 1999;66:485–492. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(98)00316-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dealberto MJ, Pajot N, Courbon D, Alperovitch A. Breathing disorders during sleep and cognitive performance in an older community sample: the EVA Study. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 1996;44:1287–1294. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1996.tb01397.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Edinger JD, Glenn DM, Bastian LA, Marsh GR. Slow-wave sleep and waking cognitive performance II: Findings among middle-aged adults with and without insomnia complaints. Physiol Behav. 2000;70:127–134. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(00)00238-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Engleman HM, Kingshott RN, Martin SE, Douglas NJ. Cognitive function in the sleep apnea/hypopnea syndrome (SAHS) Sleep. 2000;23(Suppl 4):S102–S108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Granat P. Sleep loss and cognitive performance. J Fam Pract. 1990;30:632. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McCann UD, Penetar DM, Shaham Y, et al. Sleep deprivation and impaired cognition. Possible role of brain catecholamines. Biological psychiatry. 1992;31:1082–1097. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(92)90153-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Greenberg GD, Watson RK, Deptula D. Neuropsychological dysfunction in sleep apnea. Sleep. 1987;10:254–262. doi: 10.1093/sleep/10.3.254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lojander J, Kajaste S, Maasilta P, Partinen M. Cognitive function and treatment of obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Journal of sleep research. 1999;8:71–76. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2869.1999.00141.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Redline S, Strauss ME, Adams N, et al. Neuropsychological function in mild sleep-disordered breathing. Sleep. 1997;20:160–167. doi: 10.1093/sleep/20.2.160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Barbe, Pericas J, Munoz A, Findley L, Anto JM, Agusti AG. Automobile accidents in patients with sleep apnea syndrome. An epidemiological and mechanistic study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998;158:18–22. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.158.1.9709135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Findley L, Unverzagt M, Guchu R, Fabrizio M, Buckner J, Suratt P. Vigilance and automobile accidents in patients with sleep apnea or narcolepsy. Chest. 1995;108:619–624. doi: 10.1378/chest.108.3.619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Findley LJ, Suratt PM, Dinges DF. Time-on-task decrements in “steer clear” performance of patients with sleep apnea and narcolepsy. Sleep. 1999;22:804–809. doi: 10.1093/sleep/22.6.804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bedard MA, Montplaisir J, Richer F, Malo J. Nocturnal hypoxemia as a determinant of vigilance impairment in sleep apnea syndrome. Chest. 1991;100:367–370. doi: 10.1378/chest.100.2.367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Giles TL, Lasserson TJ, Smith BH, White J, Wright J, Cates CJ. Continuous positive airways pressure for obstructive sleep apnoea in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006:CD001106. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001106.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Keenan SP, Burt H, Ryan CF, Fleetham JA. Long-term survival of patients with obstructive sleep apnea treated by uvulopalatopharyngoplasty or nasal CPAP. Chest. 1994;105:155–159. doi: 10.1378/chest.105.1.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Faccenda JF, Mackay TW, Boon NA, Douglas NJ. Randomized placebo-controlled trial of continuous positive airway pressure on blood pressure in the sleep apnea-hypopnea syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;163:344–348. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.163.2.2005037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bedard MA, Montplaisir J, Malo J, Richer F, Rouleau I. Persistent neuropsychological deficits and vigilance impairment in sleep apnea syndrome after treatment with continuous positive airways pressure (CPAP) J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 1993;15:330–341. doi: 10.1080/01688639308402567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Montplaisir J, Bedard MA, Richer F, Rouleau I. Neurobehavioral manifestations in obstructive sleep apnea syndrome before and after treatment with continuous positive airway pressure. Sleep. 1992;15:S17–S19. doi: 10.1093/sleep/15.suppl_6.s17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Engleman HM, Martin SE, Deary IJ, Douglas NJ. Effect of CPAP therapy on daytime function in patients with mild sleep apnoea/hypopnoea syndrome. Thorax. 1997;52:114–119. doi: 10.1136/thx.52.2.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kotterba S, Rasche K, Widdig W, et al. Neuropsychological investigations and event-related potentials in obstructive sleep apnea syndrome before and during CPAP-therapy. Journal of the neurological sciences. 1998;159:45–50. doi: 10.1016/s0022-510x(98)00131-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Matthews EE, Aloia MS. Cognitive recovery following positive airway pressure (PAP) in sleep apnea. Progress in brain research. 2011;190:71–88. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-444-53817-8.00004-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Naegele B, Pepin JL, Levy P, Bonnet C, Pellat J, Feuerstein C. Cognitive executive dysfunction in patients with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome (OSAS) after CPAP treatment. Sleep. 1998;21:392–397. doi: 10.1093/sleep/21.4.392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gozal D. CrossTalk proposal: the intermittent hypoxia attending severe obstructive sleep apnoea does lead to alterations in brain structure and function. The Journal of physiology. 2013;591:379–381. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2012.241216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Djonlagic I, Saboisky J, Carusona A, Stickgold R, Malhotra A. Increased sleep fragmentation leads to impaired off-line consolidation of motor memories in humans. PloS one. 2012;7:e34106. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0034106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kloepfer C, Riemann D, Nofzinger EA, et al. Memory before and after sleep in patients with moderate obstructive sleep apnea. J Clin Sleep Med. 2009;5:540–548. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Huber R, Ghilardi MF, Massimini M, Tononi G. Local sleep and learning. Nature. 2004;430:78–81. doi: 10.1038/nature02663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kuriyama K, Stickgold R, Walker MP. Sleep-dependent learning and motor-skill complexity. Learning & memory (Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y. 2004;11:705–713. doi: 10.1101/lm.76304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Walker M, Brakefield T, Morgan A, Hobson JA, Stickgold R. Practice with sleep makes perfect: Sleep dependent motor skill learning. Neuron. 2002;35:205–211. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00746-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Karni A, Meyer G, Rey-Hipolito C, et al. The acquisition of skilled motor performance: fast and slow experience-driven changes in primary motor cortex. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1998;95:861–868. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.3.861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fischer S, Hallschmid M, Elsner AL, Born J. Sleep forms memory for finger skills. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2002;99:11987–11991. doi: 10.1073/pnas.182178199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Van Dongen HP, Maislin G, Mullington JM, Dinges DF. The cumulative cost of additional wakefulness: dose-response effects on neurobehavioral functions and sleep physiology from chronic sleep restriction and total sleep deprivation. Sleep. 2003;26:117–126. doi: 10.1093/sleep/26.2.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Roach GD, Dawson D, Lamond N. Can a shorter psychomotor vigilance task be used as a reasonable substitute for the ten-minute psychomotor vigilance task? Chronobiol Int. 2006;23:1379–1387. doi: 10.1080/07420520601067931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Iber C, Ancoli-Israel S, AL C, SF Q. The AASM Manual for the Scoring of Sleep and Associated Events: Rules, Terminology, and Technical Specifications. Westchester, Ill, American Academy of Sleep Medicine. 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 50.Anbar RD, Hehir DA. Hypnosis as a diagnostic modality for vocal cord dysfunction. Pediatrics. 2000;106:E81. doi: 10.1542/peds.106.6.e81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wamsley EJ, Tucker MA, Shinn AK, et al. Reduced sleep spindles and spindle coherence in schizophrenia: mechanisms of impaired memory consolidation? Biological psychiatry. 71:154–161. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2011.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nishida M, Walker MP. Daytime naps, motor memory consolidation and regionally specific sleep spindles. PloS one. 2007;2:e341. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ungerleider LG, Doyon J, Karni A. Imaging brain plasticity during motor skill learning. Neurobiology of learning and memory. 2002;78:553–564. doi: 10.1006/nlme.2002.4091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Canessa N, Castronovo V, Cappa SF, et al. Obstructive sleep apnea: brain structural changes and neurocognitive function before and after treatment. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183:1419–1426. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201005-0693OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bardwell WA, Ancoli-Israel S, Berry CC, Dimsdale JE. Neuropsychological effects of one-week continuous positive airway pressure treatment in patients with obstructive sleep apnea: a placebo-controlled study. Psychosomatic medicine. 2001;63:579–584. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200107000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Munoz A, Mayoralas LR, Barbe F, Pericas J, Agusti AG. Long-term effects of CPAP on daytime functioning in patients with sleep apnoea syndrome. Eur Respir J. 2000;15:676–681. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3003.2000.15d09.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Feuerstein C, Naegele B, Pepin JL, Levy P. Frontal lobe-related cognitive functions in patients with sleep apnea syndrome before and after treatment. Acta Neurol Belg. 1997;97:96–107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Fogel SM, Smith CT. The function of the sleep spindle: a physiological index of intelligence and a mechanism for sleep-dependent memory consolidation. Neuroscience and biobehavioral reviews. 2011;35:1154–1165. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2010.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wilson MA, McNaughton BL. Reactivation of hippocampal ensemble memories during sleep. Science (New York, N.Y) 1994;265:676–679. doi: 10.1126/science.8036517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kim A, Latchoumane C, Lee S, et al. Optogenetically induced sleep spindle rhythms alter sleep architectures in mice. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2012;109:20673–20678. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1217897109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gottselig JM, Bassetti CL, Achermann P. Power and coherence of sleep spindle frequency activity following hemispheric stroke. Brain. 2002;125:373–383. doi: 10.1093/brain/awf021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.