Abstract

The neuroinflammatory response has received increasing attention as a key factor in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Microglia, the innate immune cells and resident phagocytes of the brain, respond to accumulating Aβ peptides by generating a nonresolving inflammatory response. While this response can clear Aβ peptides from the nervous system in some settings, its failure to do so in AD accelerates synaptic injury, neuronal loss, and cognitive decline. The complex molecular components of this response are beginning to be unraveled, with identification of both damaging and protective roles for individual components of the neuroinflammatory response. Even within one molecular pathway, contrasting effects are often present. As one example, recent studies of the inflammatory cyclooxygenase–prostaglandin pathway have revealed both beneficial and detrimental effects dependent on the disease context, cell type, and downstream signaling pathway. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), which inhibit cyclooxygenases, are associated with reduced AD risk when taken by cognitively normal populations, but additional clinical and mouse model studies have added complexities and caveats to this finding. Downstream of cyclooxygenase activity, prostaglandin E2 signaling exerts both damaging pro-inflammatory and protective anti-inflammatory effects through actions of specific E-prostanoid G-protein coupled receptors on specific cell types. These complexities underscore the need for careful study of individual components of the neuroinflammatory response to better understand their contribution to AD pathogenesis and progression.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, microglia, amyloid β, neuroinflammation, cyclooxgenases, prostaglandin E2, EP2 receptor, EP3 receptor, EP4 receptor

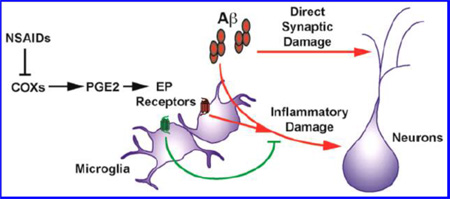

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most common cause of dementia among the elderly, with a prevalence of one in eight people over the age of 65. With projected demographic shifts toward an aging population, the annual incidence of new AD cases is projected to triple by 2050,1 with costs of care rising from $226 billion in 2015 to more than $1 trillion by 2050 (Alzheimer’s Association Facts, 2015). This coming epidemic represents one of the most serious challenges to our health care system in the coming decades. There is an urgent need for strategies to treat and, perhaps even more importantly, to prevent AD. Given that AD prevalence doubles every 5 years after the age of 65, strategies delaying the onset of AD by even 5 years would be predicted to reduce disease burden by 50%.

In the quest to develop preventive and therapeutic strategies, the first step has been to characterize disease progression itself. Over a century ago, Alois Alzheimer first identified a case of dementia for which post-mortem brain tissue demonstrated abnormal extracellular protein deposits and intracellular tangled structures.2 Since that initial discovery, the amyloid-β (Aβ) peptide has been identified as the major component of extracellular plaques in AD3 and the microtubule associated protein tau as the major component of intracellular neurofibrillary tangles.4 Supporting a causative role for Aβ in AD, mutations in both amyloid precursor protein (APP) and presenilin-1 (PS1), which cleaves APP to form Aβ, are associated with pedigrees in which early onset AD is genetically inherited.5,6 These findings are the basis of the “amyloid hypothesis” that Aβ generation is a driving force in the development of AD.7 Lending additional support to this hypothesis, an APP mutation that reduces Aβ production and protects against the development of AD has recently been identified.8 At the same time, the amyloid hypothesis of AD is not without controversy. The spatial progression of tau-containing neurofibrillary tangles correlates better with neuronal death and AD progression than do Aβ plaque deposits.9 Moreover, Aβ plaques are present in the brains of many cognitively normal elderly patients, although some studies suggest that this represents a preclinical stage of AD.10,11 To resolve this controversy, additional studies of Aβ and its downstream pathological effects will be necessary.

Aβ exerts a number of toxic effects on neurons, resulting in synapse loss, neuronal network dysfunction, and ultimately neuron death, as reviewed in ref 12. Strategies aimed at reducing Aβ levels in the brain are thus a major focus of AD research. Unfortunately, several recent trials of monoclonal antibodies for Aβ have failed to alter cognitive outcomes in AD patients. This may be due to overall limitations of this strategy, including potential adverse effects of cerebral microhemorrhages and edema associated with perivascular amyloid deposits.13 Hope remains for future studies focused on anti-Aβ strategies as preventive interventions among patients at risk for AD,14 as long as care is taken to avoid adverse effects. However, the need remains for additional targets that may be able to mitigate the detrimental effects of Aβ in the brain. One such target is the neuroinflammatory response to Aβ, a complex process that may be the third factor, along with Aβ and tau, driving AD pathogenesis (reviewed in ref 15). However, neuroinflammation exerts both toxic and protective effects in disease progression, so general strategies to reduce inflammation may not be as effective as more selective approaches targeting maladaptive inflammation. Identifying and developing targeted strategies to reduce toxic effects or increase protective effects remains a potential avenue for future preventive or therapeutic interventions in AD.

Detrimental and beneficial effects of neuroinflammation in AD

Activation of the brain’s inflammatory response has long been recognized as a hallmark of AD pathology. Numerous features found in the AD brain suggest that a robust inflammatory response occurs either as a precursor to or as a consequence of Aβ plaque deposition and neurodegeneration. Many of these features resemble those seen in the innate immune response to pathogens or tissue injury: activated microglia, reactive astrocytes, complement proteins, cytokines, chemokines, and enzymes that generate reactive oxygen species are all elevated in the AD brain (reviewed in refs 16 and 17). Increasing evidence supports the idea that soluble Aβ oligomers or fibrils act directly on microglia, the resident phagocytes of the central nervous system, to drive this inflammatory process in AD (Figure 1). Microglia phagocytose Aβ in a manner dependent on scavenger receptors including CD36.18 This uptake of Aβ activates inflammatory pathways, including those that lead to secretion of the inflammatory cytokine IL-1β.19 In addition, Aβ promotes signaling via Toll-like receptors in microglia that drives production of reactive oxygen species and activation of the canonical pro-inflammatory transcription factor NF-κB.20 Moreover, genome-wide analysis of microglia treated with Aβ shows enriched up-regulation of genes containing promoter sequences for NF-κB and IRF1/IRF7, other canonical mediators of inflammatory responses.21

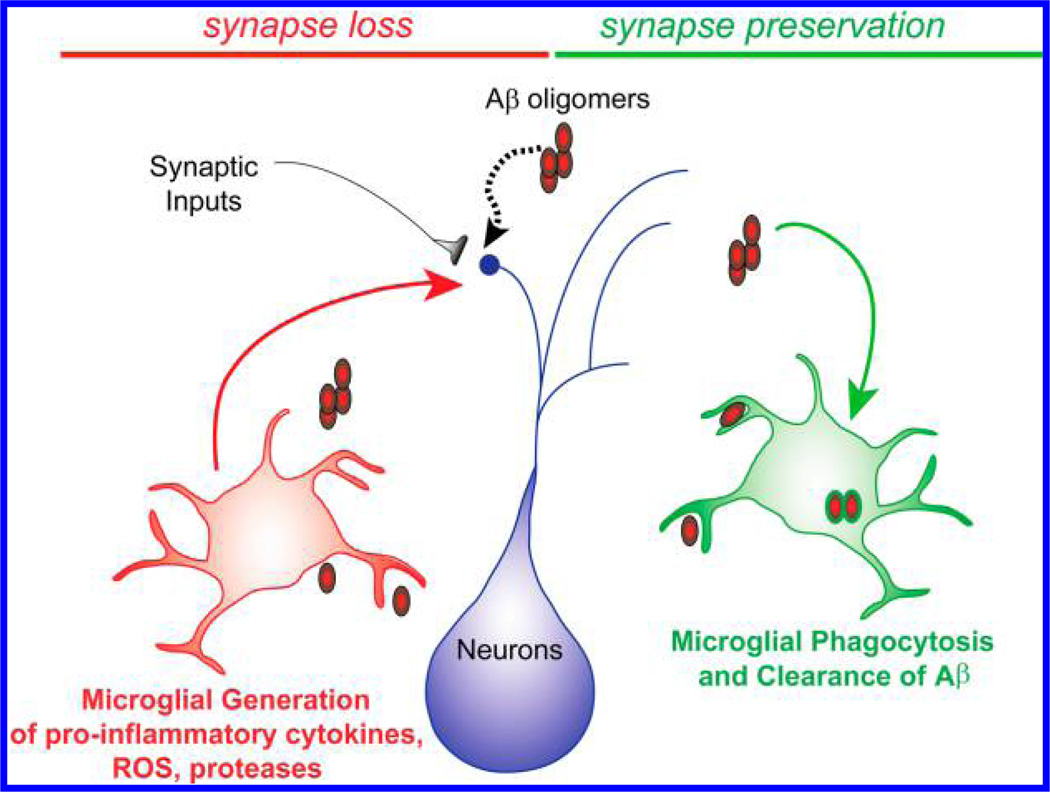

Figure 1.

The microglial neuroinflammatory response in AD. In AD, accumulating soluble Aβ species lead to synaptic loss through direct toxicity to synapses (black dashed arrow) and through maladaptive activation of microglia that produce damaging reactive oxygen species (ROS), cytokines, proteases, and chemokines. Alternatively, microglial activation can exert beneficial effects and maintain synaptic integrity and homeostasis by efficient clearance and phagocytosis of toxic misfolded proteins, such as oligomeric or fibrillar Aβ species, as well as removal of damaged synapses.

In addition, genome-wide association study (GWAS) data from late-onset AD patients has identified variants in a number of genes implicated in the microglial inflammatory response. The E4 allele of the APOE gene is by far the most frequent genetic variant in late-onset AD and one of the earliest identified;22 its role in the microglial inflammatory response is becoming increasingly clear. Microglia expressing the E4 allele of APOE have increased levels of pro-inflammatory COX-2 and prostaglandin production, with decreased levels of the microglial receptor TREM2.23 Alleles of TREM2 itself have also been associated with AD.24 The precise mechanism by which TREM2 contributes to AD is an active area of current study, with two recent reports indicating that TREM2 deficiency reduces reactive microgliosis in mouse models of AD, although the ultimate effect on Aβ accumulation and neuronal survival appears to depend on the mouse model and time point examined.25,26 Several other genetic polymorphisms associated with AD, including those in CD33 and complement receptor 1, have been found to play important roles in microglial inflammatory responses or clearance of Aβ (reviewed in ref 15). Taken together, these studies suggest that impaired microglial function plays a central role in driving AD pathogenesis.

A major hypothesis of AD etiology poses that this ongoing inflammatory response promotes synaptotoxicity and other neuronal damage leading to AD. This idea is bolstered by a number of epidemiological studies showing that the use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) is associated with reduced risk of AD, reviewed in refs 17 and 27, as discussed in more detail below. At the same time, other studies suggest that the brain inflammatory response may play a beneficial role, particularly with respect to the clearance of toxic Aβ species, as reviewed in ref 28 and discussed below. A more complete understanding of the complex balance between toxic and beneficial roles of inflammation in AD will be necessary for improved approaches to AD prevention and treatment.

The microglial inflammatory response to Aβ promotes a number of processes that appear to cause additional damage to neurons. Much of this evidence comes from mouse models of familial AD, where transgenes drive nervous system expression of mutant forms of the amyloid precursor protein (APP) or presenilin 1 (PS1) genes or both. For example, a recent study showed that microglial proliferation, which is increased in the AD patient brain, appears to drive synaptic toxicity. In APPSwe/ PS1ΔE9 transgenic mice, pharmacologically inhibiting microglial proliferation by blocking the CSF1 receptor leads to increased synaptic density and improved working memory behavior without altering Aβ accumulation.29 Specific molecular pathways within microglia appear to contribute to this neurotoxicity. C1q, the first component of the classical complement pathway, is elevated both in the AD brain and in the Tg2576 APPSwe transgenic mouse model. When C1q is genetically deleted, amyloid plaque levels remain largely constant while synaptic and dendritic loss is rescued, suggesting a role for complement in neuronal toxicity in AD.30 Another inflammatory pathway, signaling through the receptor for advanced glycation endproducts (RAGE), appears to play an important role in promoting neuronal dysfunction. In the J9 APPSwe,Ind transgenic mouse model, genetic overexpression of RAGE accelerates spatial memory deficits in the radial arm water maze, while expression of a dominant negative form of RAGE rescues performance in the same task.31 Taken together with the clear protective effects of NSAIDs in preventing AD,27 these results suggest a role for inflammatory processes in accelerating neuronal damage and consequent memory deficits in mouse models of AD.

At the same time, inflammation may perform valuable functions such as clearance of toxic Aβ peptides from the brain. Complement, for example, which appears to have toxic functions in some contexts,30 may also perform valuable functions in promoting Aβ clearance. Overexpression of the complement inhibitor protein sCrry in the J20 APPSwe,Ind model of AD results in reduced microglial activation, increased Aβ plaque deposition, and loss of neurons in the CA3 region of the hippocampus.32 The central importance of microglial clearance of Aβ has been demonstrated similarly in a study examining the role of the cytokine TGF-β in the J9 APPSwe,Ind model, where overexpression of TGF-β increases microglial activation, reduces Aβ deposition in the brain parenchyma, and reduces numbers of dystrophic neurites.33 In addition to this role for cytokines in promoting the Aβ clearance capacity of microglia, chemokine recruitment of microglia to sites of Aβ accumulation appears to be another important beneficial pathway. The chemokine receptor CCR2, expressed by macrophages that infiltrate the nervous system after injury,34 mediates migration of immune cells to sites of inflammation. In the Tg2576 APPSwe mouse model, genetic deletion of CCR2 results in reduced brain microglia and macrophage activation, increased brain Aβ levels, and a dramatically accelerated mortality for both CCR2+/− and CCR2−/− Tg2576 mice.35 These studies have in common the finding that lower levels of microglial activation are associated with higher Aβ levels and worse outcomes at the neuronal or organismal level, suggesting that the microglial inflammatory response carries out important beneficial functions in AD. At the same time, it will be important for future research to note that what is observed as “microglial activation” (often by immunostaining for the expression of marker proteins) likely constitutes several different activation states that may play context-dependent toxic or beneficial roles.36 Specifically, an age-dependent increase in toxic cytokine expression by microglia, accompanied by a decrease in receptors and enzymes associated with Aβ clearance, may underlie some of the seemingly conflicting studies identifying either toxic or beneficial roles for the microglial inflammatory response in AD models.37 Strategies aiming to tip the balance away from toxic effects and toward beneficial actions of microglia will thus be particularly important for translational studies in the future.

Mixed findings for nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in AD prevention and treatment

Extensive epidemiological, clinical, and basic science literature supports a role of NSAIDs in preventing AD. The initial finding of this association came from McGeer and colleagues,38 who reported a surprisingly low comorbidity for rheumatoid arthritis and AD, demonstrating a lower risk of AD in a patient population likely to take NSAIDs. Subsequent analysis of epidemiological data from several studies confirmed that chronic NSAID use was associated with lower risk of AD in normal aging populations.39 Strikingly, prospective studies in targeted populations in Maryland,40 Utah,41 and The Netherlands,42 and in the US Veteran’s Affairs system43 confirmed the protective effects of NSAIDs. Moreover, these studies found that longer NSAID use was associated with significantly greater protection, with up to 80% risk reduction for patients who had taken NSAIDs for more than two years.42 These consistent findings present a compelling case for the exploration of NSAID-based mechanisms in the prevention of AD. However, as discussed below, the story of NSAID use as a protective strategy carries several major caveats.

Beyond the well-known gastric and renal complications of long-term NSAID use, close examination of epidemiological and clinical trial data suggests that if NSAIDs have a protective effect, it is only when started long before the onset of AD. Later in disease progression, NSAIDs may even worsen AD symptoms. Several major studies on NSAIDs and AD have noted that NSAID use, even for several years, does not confer protection if it occurs less than two years before AD onset.40–42 Studies of normal age-related cognitive decline confirm this effect: in a population based study, patients who started NSAID use before age 65 demonstrated slower cognitive decline in their 70s and 80s, whereas those who started NSAID use after age 65 had either no change or accelerated cognitive decline depending on the population examined.44 These observational findings provide hope for strategies based on NSAID use in middle age, many years before AD onset would normally occur. Unfortunately, the clinical trials and randomized studies performed to date have generally focused on later stages of cognitive decline and have largely found no beneficial effect of NSAID treatment at this stage (reviewed in ref 17).

The general failure of these clinical trials for NSAIDs in AD reinforces the hypothesis that NSAID use is protective only if initiated long before disease onset. While one initial study found improved cognitive performance with indomethacin treatment compared with placebo in a small group of AD patients,45 other trials have been disappointing. Neither naproxen nor rofecoxib had any effect on cognitive decline in 1-year placebo-controlled trials in patients with established AD.46,47 In an attempt to study the effect of earlier NSAID use in nondemented populations, the AD Anti-Inflammatory Prevention Trial (ADAPT) was initiated to test in a placebo-controlled study whether naproxen or celecoxib prevented AD onset and slowed cognitive decline in patients over 70 years old at the time of enrollment. Unfortunately, treatment in this study was halted after cardiovascular complications were discovered with the use of these drugs in other clinical trials.48 In ADAPT, treatment with either celecoxib or naproxen was terminated prematurely because of cardiovascular safety concerns; as a result, treatment with either celecoxib or naproxen lasted a median of 14.8 months, as opposed to the originally planned 7 years. Although a follow-up study on these subjects revealed no change in the risk of AD development 6 years after discontinuation of treatment,52 other follow-up analyses have yielded additional insights. Analysis from the first four years after randomization demonstrated an increased risk for AD development among celecoxib- and naproxen-treated patients,49 consistent with the worsening of cognitive decline seen in some populations who begin NSAID use after age 65.44 Later reanalysis of the ADAPT study removed from the data set patients with any symptoms of cognitive impairment at the start of the trial and those who developed AD in the first 2.5 years of observation, thereby limiting the study to patients who were cognitively intact at the outset of the trial. In this post hoc analysis, naproxen-treated patients showed significantly reduced rates of AD.50 Moreover, CSF samples taken from a randomized subset of these patients demonstrated that naproxen significantly reduced the tau/Aβ42 ratio, a biomarker positively correlated with the risk of cognitive decline and AD among elderly populations.51 While these data come from a post hoc analysis of a trial initially designed for different measures, they offer a hint of support for the preventive role of NSAIDs in AD.

One possibility is that long-term NSAID use protects against AD only when initiated long before cognitive decline begins. The failure of previous clinical trials in AD patients likely reflects the paradoxically detrimental effects of NSAID use when cognitive decline leading to AD has already begun. Future clinical studies will thus need to examine the longer-term effects of NSAID treatment beginning in younger patients. These trials, however, will be challenging to pursue both in terms of time and funding. Moreover, the side effects associated with NSAID use suggest that identifying the downstream mechanism for NSAID protection could yield safer, more targeted interventions. Translational studies to identify these mechanisms in animal models may thus offer key insight for AD prevention strategies.

To date, more than 20 studies have assessed the effects of NSAID treatment in transgenic mouse models overexpressing mutant APP or PS1 or both, as listed in Table 1. Many of these studies have focused on the ability of NSAIDs to modulate brain Aβ levels, because NSAIDs such as ibuprofen modulate γ- secretase activity to produce less Aβ42 from APP in cultured cells.53 In general, the studies that have administered NSAIDs to mice after the onset of amyloid plaque deposition54–57 have found reduced amyloid plaque load and microglial activation in the brains of AD model mice treated with NSAIDs such as ibuprofen over the course of several months. However, it is important to note that this effect depends on which PS1 mutant is used in the model, because many familial PS1 mutations render the protein insensitive to γ-secretase modification by NSAIDs.58 Indeed, ibuprofen treatment reduces inflammatory markers but has no effect on Aβ levels or working memory in the 5x-FAD model containing one such mutant form of PS1.59 The above data are consistent with the proposed Aβ-lowering mechanism for NSAID protection against AD. Yet other studies have found that NSAIDs can reverse spatial memory deficits in Tg2576 APPSwe mice without altering Aβ levels or markers of inflammation,60 calling in to question the hypothesis that NSAIDs achieve protection through reduced Aβ42 generation or even through anti-inflammatory effects. Moreover, ibuprofen treatment before plaque onset in the slow-progressing R1.40 model prevents the onset of neuronal cell cycle re-entry, a marker of vulnerable neurons in AD, without altering APP processing or Aβ levels.61 These conflicting results suggest the need for animal studies that mirror the effects of NSAIDs in human patients as much as possible to uncover the mechanisms at work in the reduced risk of AD. In addition, the molecular targets and downstream signaling effects of NSAIDs may yield more specific answers.

Table 1.

Selected Studies on NSAIDs in Mouse Models of AD

| ref | Year | Model | drug used | age start (months) |

treat time | age end (months) |

Aβ effect | inflamm. Markers |

neuronal or behavioral effect |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 55 | 2000 | Tg2576 | ibuprofen | 10 | 6 months | 16 | decreased | decreased | fewer dystrophic neurites |

| 88 | 2001 | Tg2576 | ibuprofen | 10 | 6 months | 16 | rescued open field; lowered caspase activation | ||

| 14 | 17 months | 17 | decreased | decreased | |||||

| 53 | 2001 | Tg2576 | ibuprofen | 3 | 3 days | 3 | decreased | ||

| naproxen | 3 | 3 days | 3 | decreased | |||||

| 89 | 2002 | TG2576 × PS1M146L |

ibuprofen | 7 | 5 months | 12 | decreased | no change | |

| NCX-2216 | 7 | 5 months | 12 | decreased | increased | ||||

| 90 | 2003 | Tg2576 | 13 different NSAIDs |

3 | 3 days | 3 | decreased | ||

| 91 | 2003 | Tg2576 | indomethacin | 12 | 8 months | 20 | decreased | no change | |

| 57 | 2003 | Tg2576 | ibuprofen | 11 | 4 months | 15 | decreased | decreased | |

| pioglitazone | 11 | 4 months | 15 | decreased | no change | ||||

| 92 | 2004 | Tg2576 | indomethacin | 8 | 7 months | 15 | decreased | decreased | |

| 54 | 2005 | APPV717I | ibuprofen | 10 | 7 days | 10 | decreased | decreased | |

| pioglitazone | 10 | 7 days | 10 | decreased | decreased | ||||

| 93 | 2005 | Tg2576 | flurbiprofen | 3–4 | 3 days | 3–4 | decreased | ||

| 94 | 2005 | APP-PS1 | flurbiprofen | 8 | 6 months | 14 | no change | no change | |

| NO-flurbiprofen | 8 | 6 months | 14 | decreased | decreased | ||||

| 95 | 2007 | Tg2576 | flurbiprofen | 8 or 17 | 6 months or 2 weeks |

14 or 19 | no change | rescued Morris water maze | |

| 60 | 2008 | Tg2576 | ibuprofen | 12 | 1 month | 13 | no change | decreased | rescued Morris water maze |

| ibuprofen | 5 | 5 months | 10 | decreased | rescued Morris water maze | ||||

| MF tricyclic | 12 | 1 month | 13 | no change | decreased | rescued Morris water maze | |||

| naproxen | 12 | 1 month | 13 | no change | decreased | rescued Morris water maze | |||

| 96 | 2008 | 3xTg-AD | ibuprofen | 1 | 5 months | 6 | decreased | rescued Morris water maze | |

| 61 | 2009 | R1.40 | ibuprofen | 3 | 3 months | 6 | no change | decreased | lowered markers of neuronal cell-cycle entry |

| naproxen | 3 | 3 months | 6 | no change | decreased | lowered markers of neuronal cell-cycle entry | |||

| 56 | 2012 | R1.40 | ibuprofen | 15 | 9 months | 24 | decreased | decreased | |

| 59 | 2012 | 5x-FAD | ibuprofen | 3 | 3 months | 6 | no change | decreased | worsened cross maze |

| 97 | 2013 | 3xTg-AD | flurbiprofen | 5 | 2 months | 7 | no change | rescued radial arm water maze | |

| 98 | 2013 | 3xTg-AD | SC-560 | 20 | 8 days | 20 | decreased | decreased | rescued Morris water maze |

| 99 | 2013 | R1.40 | tolfenamic acid | 14–20 | 1 month | 15–21 | decreased | rescued Morris water maze and Y Maze | |

| 100 | 2014 | 3xTg-AD | ibuprofen | 1 | 15–22 months |

16–23 | decreased | rescued hippocampal volume by MRI |

Detrimental and beneficial effects of prostaglandin signaling in AD

NSAIDs inhibit cyclooxygenase enzymes—the constitutively expressed COX-1 and the inducible COX-2, cytosolic enzymes that generate PGH2 from membrane stores of arachidonic acid. PGH2 is further modified to produce the prostaglandins PGE2, PGD2, PGI2, and PGF2a, and the thromboxane TXA2. While the effect of NSAIDs to oppose inflammation has led to a generalized view of COX activity as toxic in neuroinflammatory disease, recent studies demonstrate a diversity of both toxic and protective functions for the prostaglandin products of COX-1 and COX-2. This divergence became vividly clear in the clinical development and subsequent discontinuation of several selective COX-2 inhibitors, originally aimed at inhibiting toxic COX-2 activity while avoiding inhibition of protective COX-1 activity in the gut. More extensive clinical studies found an unexpected increase in the rates of myocardial infarction and thrombotic stroke among patients on COX-2 inhibitors; however, this began only after 18 months of treatment.48,62 One hypothesized mechanism for the toxic effect of COX-2 inhibition lies in the balance of COX-2 derived prostacyclin, which promotes vasodilation and restrains platelet activation, and COX-1 derived thromboxane, which promotes vasoconstriction and aggregation of platelets.63,64 Another potential mechanism may involve an off-target effect of compounds that manifests very late after chronic COX-2 suppression. This finding indicates that, while some prostaglandin pathways are toxic, others are beneficial in a manner that is likely context dependent. Moreover, the general reluctance to use COX-2 inhibitors in the clinic underscores the need for identification of more specific interventions downstream of COX activity.

To this end, a number of recent studies have investigated the role of the downstream prostaglandin products and their receptors in models of neurological disease. Among the prostaglandins, PGE2 is of particular interest because it is found at relatively high concentrations in the brain.

PGE2 levels are increased in the CSF of probable AD patients65 and in AD patients with mild memory impairment.66 PGE2 exerts its cellular effects through four distinct G protein-coupled E-prostanoid receptors, EP1 to EP4. In vivo localization of PGE2 receptors in the brain has been limited because of poor specificity and high background of available antibodies to EP receptors; however in situ hybridization studies of mouse brain indicate that the EP1 and to a lesser extent the EP3 and EP4 receptors are expressed basally in neurons of forebrain and cerebellum (Allen Brain Atlas, www.alleninstitute.org). As described in detail below, in settings of innate immune neuroinflammation, expression levels of EP2 and EP4 transcripts are induced in microglia. Activation of PGE2 receptors triggers intracellular signals that lead to modifications in production of cAMP or phosphoinositol (PI) turnover. The effects of PGE2 are complex because PGE2 can bind to four distinct EP (for E-prostanoid) receptors, EP1 through EP4, that have divergent second messenger systems. The EP2 and EP4 receptors are coupled to Gαs, increasing cAMP production upon PGE2 binding; EP3 is coupled to Gαi and decreases cAMP production; while EP1 is coupled to Gαq and increases intracellular Ca2+ concentrations.67 Consistent with findings of beneficial as well as toxic effects of COX activity, emerging evidence indicates both protective and toxic functions for the EP receptors in ways that are receptor-, context-, and cell-type-specific, as reviewed in refs 68 and 69. However, a growing number of studies on chronic inflammatory models suggest that EP1, EP2, and EP3 receptors promote neuronal injury in models of chronic neurodegenerative disease, whereas EP4 exerts largely beneficial effects.

Of the four EP receptors, the role of EP1 in inflammatory neurodegenerative disease is least clear. EP1 exerts neurotoxic effects in models of oxidative stress, where inhibition of EP1 signaling rescues dopaminergic neurons from 6-hydroxydopamine mediated cell death.70 EP1 also appears to play a role in models of AD: genetic deletion of EP1 in the APPSwe/PS1ΔE9 mouse model of AD reduces amyloid plaque numbers in the hippocampus.71 However, the specific role of EP1 in microglia or other cell types remains to be specified.

EP2, by contrast, has been widely studied in models of inflammatory neurodegeneration. Deletion of EP2 in the APPSwe/PS1ΔE9 mouse model of AD results in decreased brain lipid oxidation and reduced Aβ levels, potentially through reduced activity of the APP cleaving enzyme BACE-1,72 an enzyme whose expression and enzymatic activity is responsive to oxidative damage in neurons.73 The functions of EP2 in promoting oxidative damage extend more generally to models of LPS-induced innate immune activation, where EP2 deletion completely abolishes the increase in brain lipid oxidation after immune activation.74 Here, at least some of the toxicity of EP2 is due to activity in microglia: cultured microglia from EP2 deficient mice fail to mount a neurotoxic oxidative response to LPS.75 Moreover, EP2 is a central player in the neurotoxic response of microglia to Aβ: as in the case of LPS, cultured microglia exposed to Aβ promote neuron death, but not when the microglia are deficient for EP2. Here, EP2 may promote further damage in models of AD, because signaling through EP2 suppresses the ability of microglia to phagocytose Aβ.76 Consistent with this finding, lethally irradiated APPSwe/PS1ΔE9 mice show reduced cerebral Aβ burden when their microglial populations are reconstituted with EP2-deficient bone marrow-derived cells compared with wild-type cells.77 The mechanism behind this effect may lie at least partially in the ability of EP2 signaling to suppress expression of the scavenger receptor CD36, a key mediator of Aβ phagocytosis by microglia.78 To specifically assess the role of microglial EP2 in models of AD, recent studies using the Cre/loxP system to delete EP2 in microglia79 have shown increased brain insulin-like growth factor levels, restored working memory, and increased synaptic density in APPSwe/PS1ΔE9 mice lacking EP2 specifically in microglia.80 Thus, microglial EP2 may promote toxicity in AD through the multiple mechanisms of reducing Aβ clearance, increasing the microglial oxidative response to Aβ, and suppressing protective growth factor production.

The EP3 receptor, though less studied so far in models of AD, appears to possess similar properties to the EP2 receptor. Deletion of EP3 in APPSwe/PS1ΔE9 mice reduces inflammatory protein expression, markers of oxidative stress, Aβ levels, and BACE-1 activity.81 Here again, the response of BACE-1 to oxidative damage73 may underlie some of the antiamyloidogenic effects of EP3 deletion, or EP3 may regulate the clearance of Aβ by microglia. These studies suggest that, although EP1, EP2, and EP3 receptors signal through distinct and even opposing G-protein coupled pathways, they each contribute to oxidative stress and damaging inflammatory responses in chronic models of AD.

In contrast, the EP4 receptor appears to exert protective effects in models of innate immunity and AD, as well as neuroprotective effects against hypoxic damage in models of stroke.82 As detailed above, stimulation of the innate immune response through peripheral injection of LPS in mice elicits a brain inflammatory response characterized by microglial activation, cytokine secretion, and production of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species that increase brain lipid oxidation. Direct stimulation of EP4 receptors in cultured microglia dramatically reduces this response to LPS,83,84 suggesting that EP4 signaling is sufficient for attenuation of the microglial innate immune response. The substrate for this divergence between EP2 and EP4 inflammatory signaling may lie in functions encoded in the extended carboxy-tail of EP4, which binds proteins that signal to inhibit inflammatory NF-κB transcriptional activity.83 In line with this, EP4 appears to be necessary for resolution of the inflammatory response. In wildtype mice, cytokine and oxidative enzyme expression in the brain is significantly elevated by 6 h after LPS injection but largely returns to baseline by 24 h. In mice with selective deletion of EP4 in microglia, this inflammatory response in the brain persists at least to 24 h.84 The anti-inflammatory effect of EP4 signaling appears to extend to the periphery as well: genetic deletion or pharmacological inhibition of EP4 exacerbates inflammation and tissue damage in a model of ulcerative colitis.85 These findings strongly implicate EP4 signaling as a pivotal factor in resolving the innate immune response in inflammatory disease. Recent studies have extended this to models of AD as well: pharmacological stimulation of the EP4 receptor in cultured microglia reduces the inflammatory response to Aβ and promotes phagocytic clearance of Aβ, while conditional deletion of the EP4 receptor in microglia exacerbates inflammatory responses, Aβ accumulation, and synaptic protein loss in APPSwe/PS1ΔE9 mice.21 Taken together, these data support an anti-inflammatory and protective role for microglial EP4 signaling in models of AD.

The above data suggest a complex mechanism in which signaling by one ligand, PGE2, may promote both an initial inflammatory response (e.g., through EP2 or EP3) and a compensatory resolution of immune activation through EP4. Given the findings above, several potential therapeutic strategies emerge to combat the damaging inflammatory response in AD: suppressing the toxic effects of EP1, EP2, and EP3 signaling or harnessing the protective effects of EP4 signaling. In the AD brain in particular, the balance among EP receptors appears to be weighted toward maladaptive pro-inflammatory signaling, as EP3 protein levels increase while EP4 protein levels decrease in the brains of mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and AD patients.21,81 This mechanism also presents a potential explanation for the contrasting protective and detrimental effects of NSAIDs seen in studies of patients at different stages of disease progression. It may be that inhibition of prostaglandin production is beneficial only at early stages when it can adequately suppress toxic signaling through EP2 and EP3 while preserving beneficial signaling through EP4.

As an additional layer of complexity, COX-1, COX-2, and EP receptors are expressed in other cell types including neurons, where their effects and contributions to AD progression may be distinct from those in microglia. COX-2 itself is a neuronal immediate early gene whose expression is rapidly induced in response to NMDA-dependent synaptic activity in the cortex and hippocampus.86 Excessive neuronal COX-2 activity may be another contributing factor to AD, because neuronal overexpression of COX-2 in the APPSwe/PS1ΔE9 mouse model worsens spatial working memory behavior.87 In light of this, neuronal COX-2 may be yet another target of NSAIDs that could contribute to their protective effects, in addition to their suppression of damaging pathways in the neuroinflammatory response.

Conclusion

The need for molecular, cellular, and temporal specificity in AD research

In light of the clinical and animal model studies discussed above, there may be limited value in pursuing interventions aimed at broad-scale inhibition of COX activity in AD without regard to timing, cellular specificity, or downstream signaling complexity. The mixed evidence for preventive effects of NSAIDs in AD and the contrasting effects of NSAIDs in different mouse models at different pathological stages accentuate the need to identify which mechanism(s) underlie NSAID protection so that more targeted strategies can be pursued. Within prostaglandin signaling, the balance between protective and toxic signaling through different PGE2 receptors underscores the need for additional detailed investigations of cell- and receptor-specific strategies. In the wider neuroinflammatory response to Aβ, these studies add to a growing consensus that it is too simplistic to think of the inflammatory response in AD as entirely damaging or entirely protective. Instead, future studies targeting individual components of the neuroinflammatory response may yield new insights in the search for preventive and therapeutic strategies against AD.

Acknowledgments

The authors were supported by R01AG030209 (KIA), R01AG15799 (KIA), R21AG033914 (KIA), R01AG048232 (KIA), P50 AG047366 (KIA), Alzheimer’s Association (KIA), Bright Focus (KIA), and NRSA F31AG039195 (NSW).

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hebert LE, Scherr PA, Bienias JL, Bennett DA, Evans DA. Alzheimer disease in the US population: prevalence estimates using the 2000 census. Arch. Neurol. 2003;60:1119–1122. doi: 10.1001/archneur.60.8.1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alzheimer A. Über eine eigenartige Erkrankung der Hirnrinde [About a peculiar disease of the cerebral cortex] Allg. Z. Psychiatr. Psych.-Gerichtl. Med. 1907;64:146–148. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Glenner GG, Wong CW. Alzheimer’s disease: initial report of the purification and characterization of a novel cerebrovascular amyloid protein. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1984;120:885–890. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(84)80190-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grundke-Iqbal I, Iqbal K, Tung YC, Quinlan M, Wisniewski HM, Binder LI. Abnormal phosphorylation of the microtubule-associated protein tau (tau) in Alzheimer cytoskeletal pathology. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1986;83:4913–4917. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.13.4913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goate A, Chartier-Harlin MC, Mullan M, Brown J, Crawford F, Fidani L, Giuffra L, Haynes A, Irving N, James L, et al. Segregation of a missense mutation in the amyloid precursor protein gene with familial Alzheimer’s disease. Nature. 1991;349:704–706. doi: 10.1038/349704a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sherrington R, Rogaev EI, Liang Y, Rogaeva EA, Levesque G, Ikeda M, Chi H, Lin C, Li G, Holman K, Tsuda T, Mar L, Foncin JF, Bruni AC, Montesi MP, Sorbi S, Rainero I, Pinessi L, Nee L, Chumakov I, Pollen D, Brookes A, Sanseau P, Polinsky RJ, Wasco W, Da Silva HA, Haines JL, Perkicak- Vance MA, Tanzi RE, Roses AD, Fraser PE, Rommens JM, St George-Hyslop PH. Cloning of a gene bearing missense mutations in early-onset familial Alzheimer’s disease. Nature. 1995;375:754–760. doi: 10.1038/375754a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hardy JA, Higgins GA. Alzheimer’s disease: the amyloid cascade hypothesis. Science. 1992;256:184–185. doi: 10.1126/science.1566067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jonsson T, Atwal JK, Steinberg S, Snaedal J, Jonsson PV, Björnsson S, Stefansson H, Sulem P, Gudbjartsson D, Maloney J, Hoyte K, Gustafson A, Liu Y, Lu Y, Bhangale T, Graham RR, Huttenlocher J, Bjornsdottir G, Andreassen OA, Jönsson EG, Palotie A, Behrens TW, Magnusson OT, Kong A, Thorsteinsdottir U, Watts RJ, Stefansson K. A mutation in APP protects against Alzheimer’s disease and age-related cognitive decline. Nature. 2012;488:96–99. doi: 10.1038/nature11283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Arriagada PV, Growdon JH, Hedley-Whyte ET, Hyman BT. Neurofibrillary tangles but not senile plaques parallel duration and severity of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology. 1992;42:631–631. doi: 10.1212/wnl.42.3.631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morris JC, Storandt M, McKeel DW, Rubin EH, Price JL, Grant EA, Berg L. Cerebral amyloid deposition and diffuse plaques in normal aging: Evidence for presymptomatic and very mild Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology. 1996;46:707–719. doi: 10.1212/wnl.46.3.707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vlassenko AG, Mintun MA, Xiong C, Sheline YI, Goate AM, Benzinger TLS, Morris JC. Amyloid-beta plaque growth in cognitively normal adults: longitudinal [11C]- Pittsburgh compound B data. Ann. Neurol. 2011;70:857–861. doi: 10.1002/ana.22608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Palop JJ, Mucke L. Amyloid-beta-induced neuronal dysfunction in Alzheimer’s disease: from synapses toward neural networks. Nat. Neurosci. 2010;13:812–818. doi: 10.1038/nn.2583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wisniewski T, Konietzko U. Amyloid-beta immunisation for Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet Neurol. 2008;7:805–811. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(08)70170-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miller G. Alzheimer’s research. Stopping Alzheimer’s before it starts. Science. 2012;337:790–792. doi: 10.1126/science.337.6096.790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mhatre SD, Tsai CA, Rubin AJ, James ML, Andreasson KI. Microglial Malfunction: The Third Rail in the Development of Alzheimer’s Disease. Trends Neurosci. 2015;38:621–636. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2015.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Akiyama HH, Barger SS, Barnum SS, Bradt BB, Bauer JJ, Cole GMG, Cooper NRN, Eikelenboom PP, Emmerling MM, Fiebich BLB, Finch CEC, Frautschy SS, Griffin WSW, Hampel HH, Hull MM, Landreth GG, Lue LL, Mrak RR, Mackenzie IRI, McGeer PLP, O’Banion MKM, Pachter JJ, Pasinetti GG, Plata-Salaman CC, Rogers JJ, Rydel RR, Shen YY, Streit WW, Strohmeyer RR, Tooyoma II, Van Muiswinkel FLF, Veerhuis RR, Walker DD, Webster SS, Wegrzyniak BB, Wenk GG, Wyss-Coray TT. Inflammation and Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol. Aging. 2000;21:383–421. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(00)00124-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heneka MT, Carson MJ, Khoury JE, Landreth GE, Brosseron F, Feinstein DL, Jacobs AH, Wyss-Coray T, Vitorica J, Ransohoff RM, Herrup K, Frautschy SA, Finsen B, Brown GC, Verkhratsky A, Yamanaka K, Koistinaho J, Latz E, Halle A, Petzold GC, Town T, Morgan D, Shinohara ML, Perry VH, Holmes C, Bazan NG, Brooks DJ, Hunot S, Joseph B, Deigendesch N, Garaschuk O, Boddeke E, Dinarello CA, Breitner JC, Cole GM, Golenbock DT, Kummer MP. Neuroinflammation in Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet Neurol. 2015;14:388–405. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(15)70016-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.El Khoury JB, Moore KJ, Means TK, Leung J, Terada K, Toft M, Freeman MW, Luster AD. CD36 mediates the innate host response to beta-amyloid. J. Exp. Med. 2003;197:1657–1666. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Halle A, Hornung V, Petzold GC, Stewart CR, Monks BG, Reinheckel T, Fitzgerald KA, Latz E, Moore KJ, Golenbock DT. The NALP3 inflammasome is involved in the innate immune response to amyloid-beta. Nat. Immunol. 2008;9:857–865. doi: 10.1038/ni.1636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reed-Geaghan EG, Savage JC, Hise AG, Landreth GE. CD14 and Toll-Like Receptors 2 and 4 Are Required for Fibrillar A -Stimulated Microglial Activation. J. Neurosci. 2009;29:11982–11992. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3158-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Woodling NS, Wang Q, Priyam PG, Larkin P, Shi J, Johansson JU, Zagol-Ikapitte I, Boutaud O, Andreasson KI. Suppression of Alzheimer-Associated Inflammation by Microglial Prostaglandin-E2 EP4 Receptor Signaling. J. Neurosci. 2014;34:5882–5894. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0410-14.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Poirier J, Davignon J, Bouthillier D, Kogan S, Bertrand P, Gauthier S. Apolipoprotein E polymorphism and Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet. 1993;342:697–699. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)91705-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li X, Montine KS, Keene CD, Montine TJ. Different mechanisms of apolipoprotein E isoform–dependent modulation of prostaglandin E2 production and triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells 2 (TREM2) expression after innate immune activation of microglia. FASEB J. 2015;29:1754–1762. doi: 10.1096/fj.14-262683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guerreiro R, Wojtas A, Bras J, Carrasquillo M, Rogaeva E, Majounie E, Cruchaga C, Sassi C, Kauwe JSK, Younkin S, Hazrati L, Collinge J, Pocock J, Lashley T, Williams J, Lambert J-C, Amouyel P, Goate A, Rademakers R, Morgan K, Powell J, St George Hyslop P, Singleton A, Hardy J. TREM2Variants in Alzheimer’s Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013;368:117. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1211851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jay TR, Miller CM, Cheng PJ, Graham LC, Bemiller S, Broihier ML, Xu G, Margevicius D, Karlo JC, Sousa GL, Cotleur AC, Butovsky O, Bekris L, Staugaitis SM, Leverenz JB, Pimplikar SW, Landreth GE, Howell GR, Ransohoff RM, Lamb BT. TREM2 deficiency eliminates TREM2+ inflammatory macrophages and ameliorates pathology in Alzheimer’s disease mouse models. J. Exp. Med. 2015;212:287–295. doi: 10.1084/jem.20142322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang Y, Cella M, Mallinson K, Ulrich JD, Young KL, et al. TREM2 Lipid Sensing Sustains the Microglial Response in an Alzheimer’s Disease Model. Cell. 2015;160:1061. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.01.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mcgeer PL, McGeer EG. NSAIDs and Alzheimer disease: epidemiological, animal model and clinical studies. Neurobiol. Aging. 2007;28:639–647. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2006.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wyss-Coray T. Inflammation in Alzheimer disease: driving force, bystander or beneficial response? Nat. Med. 2006;12:1005–1015. doi: 10.1038/nm1484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Olmos-Alonso A, Schetters STT, Sri S, Askew K, Mancuso R, Vargas-Caballero M, Holscher C, Perry VH, Gomez-Nicola D. Pharmacological targeting of CSF1R inhibits microglial proliferation and prevents the progression of Alzheimer’s-like pathology. Brain. 2016;139:891. doi: 10.1093/brain/awv379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fonseca MI, Zhou J, Botto M, Tenner AJ. Absence of C1q leads to less neuropathology in transgenic mouse models of Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neurosci. 2004;24:6457–6465. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0901-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Arancio O, Zhang HP, Chen X, Lin C, Trinchese F, Puzzo D, Liu S, Hegde A, Yan SF, Stern A, Luddy JS, Lue L-F, Walker DG, Roher A, Buttini M, Mucke L, Li W, Schmidt AM, Kindy M, Hyslop PA, Stern DM, Du Yan SS. RAGE potentiates Abeta-induced perturbation of neuronal function in transgenic mice. EMBO J. 2004;23:4096–4105. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wyss-Coray T, Yan F, Lin A, Lambris J, Alexander J, Quigg R, Masliah E. Prominent neurodegeneration and increased plaque formation in complement-inhibited Alzheimer’s mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2002;99:10837–10842. doi: 10.1073/pnas.162350199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wyss-Coray T, Lin C, Yan F, Yu GQ, Rohde M, McConlogue L, Masliah E, Mucke L. TGF-beta1 promotes microglial amyloid-beta clearance and reduces plaque burden in transgenic mice. Nat. Med. 2001;7:612–618. doi: 10.1038/87945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mizutani M, Pino PA, Saederup N, Charo IF, Ransohoff RM, Cardona AE. The Fractalkine Receptor but Not CCR2 Is Present on Microglia from Embryonic Development throughout Adulthood. J. Immunol. 2012;188:29–36. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1100421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.El Khoury J, Toft M, Hickman SE, Means TK, Terada K, Geula C, Luster AD. Ccr2 deficiency impairs microglial accumulation and accelerates progression of Alzheimer-like disease. Nat. Med. 2007;13:432–438. doi: 10.1038/nm1555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Colton CA. Heterogeneity of Microglial Activation in the Innate Immune Response in the Brain. J. Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2009;4:399–418. doi: 10.1007/s11481-009-9164-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hickman SE, Allison EK, El Khoury J. Microglial Dysfunction and Defective Beta-Amyloid Clearance Pathways in Aging Alzheimer’s Disease Mice. J. Neurosci. 2008;28:8354–8360. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0616-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McGeer PL, McGeer E, Rogers J, Sibley J. Antiinflammatory drugs and Alzheimer disease. Lancet. 1990;335:1037. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(90)91101-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McGeer PL, Schulzer M, McGeer EG. Arthritis and anti-inflammatory agents as possible protective factors for Alzheimer’s disease: A review of 17 epidemiologic studies. Neurology. 1996;47:425–432. doi: 10.1212/wnl.47.2.425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stewart WF, Kawas C, Corrada M, Metter EJ. Risk of Alzheimer’s disease and duration of NSAID use. Neurology. 1997;48:626–632. doi: 10.1212/wnl.48.3.626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zandi PP, Anthony JC, Hayden KM, Mehta K, Mayer L, Breitner J. Reduced incidence of AD with NSAID but not H2 receptor antagonists: the Cache County Study. Neurology. 2002;59:880–886. doi: 10.1212/wnl.59.6.880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.in t Veld BA, Ruitenberg A, Hofman A, Launer LJ, van Duijn CM, Stijnen T, Breteler MM, Stricker BH. Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs and the risk of Alzheimer’s disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2001;345:1515–1521. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa010178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vlad SC, Miller DR, Kowall NW, Felson DT. Protective effects of NSAIDs on the development of Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2008;70:1672–1677. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000311269.57716.63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hayden KM, Zandi PP, Khachaturian AS, Szekely CA, Fotuhi M, Norton MC, Tschanz JT, Pieper CF, Corcoran C, Lyketsos CG, Breitner JCS, Welsh-Bohmer KA the Cache County Investigators. Does NSAID use modify cognitive trajectories in the elderly? The Cache County study. Neurology. 2007;69:275–282. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000265223.25679.2a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rogers J, Kirby LC, Hempelman SR, Berry DL, McGeer PL, Kaszniak AW, Zalinski J, Cofield M, Mansukhani L, Willson P, Kogan F. Clinical trial of indomethacin in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology. 1993;43:1609–1611. doi: 10.1212/wnl.43.8.1609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Aisen PS, Schafer KA, Grundman M, Pfeiffer E, Sano M, Davis KL, Farlow MR, Jin S, Thomas RG, Thal LJ the Alzheimer's Disease Cooperative Study. Effects of rofecoxib or naproxen vs placebo on Alzheimer disease progression: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA, J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2003;289:2819–2826. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.21.2819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Reines SA, Block GA, Morris JC, Liu G, Nessly ML, Lines CR, Norman BA, Baranak CC the Rofecoxib Protocol 091 Study Group. Rofecoxib: no effect on Alzheimer’s disease in a 1-year, randomized, blinded, controlled study. Neurology. 2004;62:66–71. doi: 10.1212/wnl.62.1.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bresalier RS, Sandler RS, Quan H, Bolognese JA, Oxenius B, Horgan K, Lines C, Riddell R, Morton D, Lanas A, Konstam MA, Baron JA the Adenomatous Polyp Prevention on Vioxx (APPROVe) Trial Investigators. Cardiovascular events associated with rofecoxib in a colorectal adenoma chemoprevention trial. N. Engl. J. Med. 2005;352:1092–1102. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.ADAPT Research Group. Martin BK, Szekely C, Brandt J, Piantadosi S, Breitner JCS, Craft S, Evans D, Green R, Mullan M. Cognitive function over time in the Alzheimer’s Disease Anti-inflammatory Prevention Trial (ADAPT): results of a randomized, controlled trial of naproxen and celecoxib. Arch. Neurol. 2008;65:896–905. doi: 10.1001/archneur.2008.65.7.nct70006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Breitner JC, Baker LD, Montine TJ, Meinert CL, Lyketsos CG, Ashe KH, Brandt J, Craft S, Evans DE, Green RC, Ismail MS, Martin BK, Mullan MJ, Sabbagh M, Tariot PN ADAPT Research Group. Extended results of the Alzheimer’s disease anti-inflammatory prevention trial. Alzheimer's Dementia. 2011;7:402–411. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2010.12.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sonnen JA, Montine KS, Quinn JF, Kaye JA, Breitner JC, Montine TJ. Biomarkers for cognitive impairment and dementia in elderly people. Lancet Neurol. 2008;7:704–714. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(08)70162-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.ADAPT Research Group. Results of a follow-up study to the randomized Alzheimer’s Disease Anti-inflammatory Prevention Trial (ADAPT) Alzheimer's Dementia. 2013;9:714–723. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2012.11.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Weggen S, Eriksen JL, Das P, Sagi SA, Wang R, Pietrzik CU, Findlay KA, Smith TE, Murphy MP, Bulter T, Kang DE, Marquez-Sterling N, Golde TE, Koo EH. A subset of NSAIDs lower amyloidogenic Abeta42 independently of cyclooxygenase activity. Nature. 2001;414:212–216. doi: 10.1038/35102591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Heneka MT, Sastre M, Dumitrescu-Ozimek L, Hanke A, Dewachter I, Kuiperi C, O’Banion K, Klockgether T, van Leuven F, Landreth GE. Acute treatment with the PPARgamma agonist pioglitazone and ibuprofen reduces glial inflammation and Abeta1–42 levels in APPV717I transgenic mice. Brain. 2005;128:1442–1453. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lim GP, Yang F, Chu T, Chen P, Beech W, Teter B, Tran T, Ubeda O, Ashe KH, Frautschy SA, Cole GM. Ibuprofen suppresses plaque pathology and inflammation in a mouse model for Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neurosci. 2000;20:5709–5714. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-15-05709.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wilkinson BL, Cramer PE, Varvel NH, Reed-Geaghan E, Jiang Q, Szabo A, Herrup K, Lamb BT, Landreth GE. Ibuprofen attenuates oxidative damage through NOX2 inhibition in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol. Aging. 2012;33:197.e121–197.e132. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2010.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yan Q, Zhang J, Liu H, Babu-Khan S, Vassar R, Biere AL, Citron M, Landreth G. Anti-inflammatory drug therapy alters beta-amyloid processing and deposition in an animal model of Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neurosci. 2003;23:7504–7509. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-20-07504.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Czirr E, Leuchtenberger S, Dorner-Ciossek C, Schneider A, Jucker M, Koo EH, Pietrzik CU, Baumann K, Weggen S. Insensitivity to Abeta42-lowering nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and gamma-secretase inhibitors is common among aggressive presenilin-1 mutations. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:24504–24513. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M700618200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hillmann A, Hahn S, Schilling S, Hoffmann T, Demuth H-U, Bulic B, Schneider-Axmann T, Bayer TA, Weggen S, Wirths O. No improvement after chronic ibuprofen treatment in the 5XFAD mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol. Aging. 2012;33:833.e39–833.e50. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2011.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kotilinek LA, Westerman MA, Wang Q, Panizzon K, Lim GP, Simonyi A, Lesne S, Falinska A, Younkin LH, Younkin SG, Rowan M, Cleary J, Wallis RA, Sun GY, Cole G, Frautschy S, Anwyl R, Ashe KH. Cyclooxygenase-2 inhibition improves amyloid-beta-mediated suppression of memory and synaptic plasticity. Brain. 2008;131:651–664. doi: 10.1093/brain/awn008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Varvel NH, Bhaskar K, Kounnas MZ, Wagner SL, Yang Y, Lamb BT, Herrup K. NSAIDs prevent, but do not reverse, neuronal cell cycle reentry in a mouse model of Alzheimer disease. J. Clin. Invest. 2009;119:3692–3702. doi: 10.1172/JCI39716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bombardier C, Laine L, Reicin A, Shapiro D, Burgos-Vargas R, Davis B, Day R, Ferraz MB, Hawkey CJ, Hochberg MC, Kvien TK, Schnitzer TJ the VIGOR Study Group. Comparison of upper gastrointestinal toxicity of rofecoxib and naproxen in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2000;343:1520–1528. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200011233432103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Egan KM, Lawson JA, Fries S, Koller B, Rader DJ, Smyth EM, Fitzgerald GA. COX-2-derived prostacyclin confers atheroprotection on female mice. Science. 2004;306:1954–1957. doi: 10.1126/science.1103333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Fitzgerald GA. Coxibs and cardiovascular disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2004;351:1709–1711. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp048288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Montine TJT, Sidell KRK, Crews BCB, Markesbery WRW, Marnett LJL, Roberts LJL, Morrow JDJ. Elevated CSF prostaglandin E2 levels in patients with probable AD. Neurology. 1999;53:1495–1498. doi: 10.1212/wnl.53.7.1495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Combrinck M, Williams J, De Berardinis MA, Warden D, Puopolo M, Smith AD, Minghetti L. Levels of CSF prostaglandin E2, cognitive decline, and survival in Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neurol., Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 2006;77:85–88. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2005.063131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Breyer RM, Bagdassarian CK, Myers SA, Breyer MD. Prostanoid receptors: subtypes and signaling. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2001;41:661–690. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.41.1.661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Andreasson K. Emerging roles of PGE2 receptors in models of neurological disease. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediators. 2010;91:104–112. doi: 10.1016/j.prostaglandins.2009.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Johansson J, Woodling N, Shi J, Andreasson K. Inflammatory Cyclooxygenase Activity and PGE2 Signaling in Models of Alzheimer’s Disease. Current Immunology Reviews. 2015;11:125–131. doi: 10.2174/1573395511666150707181414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Carrasco EE, Casper DD, Werner PP. PGE(2) receptor EP1 renders dopaminergic neurons selectively vulnerable to low-level oxidative stress and direct PGE(2) neurotoxicity. J. Neurosci. Res. 2007;85:3109–3117. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zhen G, Kim YT, Li R-C, Yocum J, Kapoor N, Langer J, Dobrowolski P, Maruyama T, Narumiya S, Doré S. PGE2 EP1 receptor exacerbated neurotoxicity in a mouse model of cerebral ischemia and Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol. Aging. 2012;33:2215–2219. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2011.09.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Liang X, Wang Q, Hand T, Wu L, Breyer RM, Montine TJ, Andreasson K. Deletion of the prostaglandin E2 EP2 receptor reduces oxidative damage and amyloid burden in a model of Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neurosci. 2005;25:10180–10187. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3591-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Tamagno EE, Bardini PP, Obbili AA, Vitali AA, Borghi RR, Zaccheo DD, Pronzato MAM, Danni OO, Smith MAM, Perry GG, Tabaton MM. Oxidative stress increases expression and activity of BACE in NT2 neurons. Neurobiol. Dis. 2002;10:279–288. doi: 10.1006/nbdi.2002.0515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Montine TJ, Milatovic D, Gupta RC, Valyi-Nagy T, Morrow JD, Breyer RM. Neuronal oxidative damage from activated innate immunity is EP2 receptor-dependent. J. Neurochem. 2002;83:463–470. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2002.01157.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Shie F-S, Montine KS, Breyer RM, Montine TJ. Microglial EP2 is critical to neurotoxicity from activated cerebral innate immunity. Glia. 2005;52:70–77. doi: 10.1002/glia.20220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Shie F-S, Breyer RM, Montine TJ. Microglia lacking E Prostanoid Receptor subtype 2 have enhanced Abeta phagocytosis yet lack Abeta-activated neurotoxicity. Am. J. Pathol. 2005;166:1163–1172. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)62336-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Keene CD, Chang RC, Lopez-Yglesias AH, Shalloway BR, Sokal I, Li X, Reed PJ, Keene LM, Montine KS, Breyer RM, Rockhill JK, Montine TJ. Suppressed Accumulation of Cerebral Amyloid {beta} Peptides in Aged Transgenic Alzheimer’s Disease Mice by Transplantation with Wild- Type or Prostaglandin E2 Receptor Subtype 2-Null Bone Marrow. Am. J. Pathol. 2010;177:346. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.090840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Li X, Melief E, Postupna N, Montine KS, Keene CD, Montine TJ. Prostaglandin E2 receptor subtype 2 regulation of scavenger receptor CD36 modulates microglial Aβ42 phagocytosis. Am. J. Pathol. 2015;185:230–239. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2014.09.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Johansson JU, Pradhan S, Lokteva LA, Woodling NS, Ko N, Brown HD, Wang Q, Loh C, Cekanaviciute E, Buckwalter M, Manning-Boğ AB, Andreasson KI. Suppression of inflammation with conditional deletion of the prostaglandin E2 EP2 receptor in macrophages and brain microglia. J. Neurosci. 2013;33:16016–16032. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2203-13.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Johansson JU, Woodling NS, Wang Q, Panchal M, Liang X, Trueba-Saiz A, Brown HD, Mhatre SD, Loui T, Andreasson KI. Prostaglandin signaling suppresses beneficial microglial function in Alzheimer’s disease models. J. Clin. Invest. 2015;125:350–364. doi: 10.1172/JCI77487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Shi J, Wang Q, Johansson JU, Liang X, Woodling NS, Priyam P, Loui TM, Merchant M, Breyer RM, Montine TJ, Andreasson K. Inflammatory prostaglandin E2 signaling in a mouse model of Alzheimer disease. Ann. Neurol. 2012;72:788–798. doi: 10.1002/ana.23677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Liang X, Lin L, Woodling NS, Wang Q, Anacker C, Pan T, Merchant M, Andreasson K. Signaling via the prostaglandin E2 receptor EP4 exerts neuronal and vascular protection in a mouse model of cerebral ischemia. J. Clin. Invest. 2011;121:4362–4371. doi: 10.1172/JCI46279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Minami M, Shimizu K, Okamoto Y, Folco E, Ilasaca M-L, Feinberg MW, Aikawa M, Libby P. Prostaglandin E receptor type 4-associated protein interacts directly with NF-kappaB1 and attenuates macrophage activation. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:9692–9703. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M709663200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Shi J, Johansson J, Woodling NS, Wang Q, Montine TJ, Andreasson K. The prostaglandin E2 E-prostanoid 4 receptor exerts anti-inflammatory effects in brain innate immunity. J. Immunol. 2010;184:7207–7218. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0903487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Kabashima KK, Saji TT, Murata TT, Nagamachi MM, Matsuoka TT, Segi EE, Tsuboi KK, Sugimoto YY, Kobayashi TT, Miyachi YY, Ichikawa AA, Narumiya SS. The prostaglandin receptor EP4 suppresses colitis, mucosal damage and CD4 cell activation in the gut. J. Clin. Invest. 2002;109:883–893. doi: 10.1172/JCI14459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Yamagata K, Andreasson KI, Kaufmann WE, Barnes CA, Worley PF. Expression of a mitogen-inducible cyclooxygenase in brain neurons: regulation by synaptic activity and glucocorticoids. Neuron. 1993;11:371–386. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(93)90192-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Melnikova T, Savonenko A, Wang Q, Liang X, Hand T, Wu L, Kaufmann WE, Vehmas A, Andreasson KI. Cycloxygenase-2 activity promotes cognitive deficits but not increased amyloid burden in a model of Alzheimer’s disease in a sex-dimorphic pattern. Neuroscience. 2006;141:1149–1162. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Lim G. Ibuprofen effects on Alzheimer pathology and open field activity in APPsw transgenic mice. Neurobiol. Aging. 2001;22:983–991. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(01)00299-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Jantzen PT, Connor KE, DiCarlo G, Wenk GL, Wallace JL, Rojiani AM, Coppola D, Morgan D, Gordon MN. Microglial activation and beta - amyloid deposit reduction caused by a nitric oxide-releasing nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug in amyloid precursor protein plus presenilin-1 transgenic mice. J. Neurosci. 2002;22:2246–2254. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-06-02246.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Eriksen JL, Sagi SA, Smith TE, Weggen S, Das P, McLendon DC, Ozols VV, Jessing KW, Zavitz KH, Koo EH, Golde TE. NSAIDs and enantiomers of flurbiprofen target gamma-secretase and lower Abeta 42 in vivo. J. Clin. Invest. 2003;112:440–449. doi: 10.1172/JCI18162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Quinn J, Montine T, Morrow J, Woodward WR, Kulhanek D, Eckenstein F. Inflammation and cerebral amyloidosis are disconnected in an animal model of Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neuroimmunol. 2003;137:32–41. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(03)00037-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Sung S, Yang H, Uryu K, Lee EB, Zhao L, Shineman D, Trojanowski JQ, Lee VM-Y, Pratico D. Modulation of Nuclear Factor-κB Activity by Indomethacin Influences Aβ Levels but Not Aβ Precursor Protein Metabolism in a Model of Alzheimer’s Disease. Am. J. Pathol. 2004;165:2197–2206. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)63269-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Lanz TA, Fici GJ, Merchant KM. Lack of specific amyloid-beta(1–42) suppression by nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in young, plaque-free Tg2576 mice and in guinea pig neuronal cultures. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2005;312:399–406. doi: 10.1124/jpet.104.073965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.van Groen T, Kadish I. Transgenic AD model mice, effects of potential anti-AD treatments on inflammation and pathology. Brain Res. Rev. 2005;48:370–378. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2004.12.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Kukar T, Prescott S, Eriksen JL, Holloway V, Murphy MP, Koo EH, Golde TE, Nicolle MM. Chronic administration of R-flurbiprofen attenuates learning impairments in transgenic amyloid precursor protein mice. BMC Neurosci. 2007;8:54. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-8-54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.McKee AC, Carreras I, Hossain L, Ryu H, Klein WL, Oddo S, LaFerla FM, Jenkins BG, Kowall NW, Dedeoglu A. Ibuprofen reduces Abeta, hyperphosphorylated tau and memory deficits in Alzheimer mice. Brain Res. 2008;1207:225–236. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.01.095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Carreras I, McKee AC, Choi J-K, Aytan N, Kowall NW, Jenkins BG, Dedeoglu A. R-flurbiprofen improves tau, but not Aβ pathology in a triple transgenic model of Alzheimer’s disease. Brain Res. 2013;1541:115–127. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2013.10.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Choi S-H, Aid S, Caracciolo L, Minami SS, Niikura T, Matsuoka Y, Turner RS, Mattson MP, Bosetti F. Cyclooxygenase-1 inhibition reduces amyloid pathology and improves memory deficits in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neurochem. 2013;124:59–68. doi: 10.1111/jnc.12059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Subaiea GM, Adwan LI, Ahmed AH, Stevens KE, Zawia NH. Short-term treatment with tolfenamic acid improves cognitive functions in Alzheimer’s disease mice. Neurobiol. Aging. 2013;34:2421–2430. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2013.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Choi J-K, Carreras I, Aytan N, Jenkins-Sahlin E, Dedeoglu A, Jenkins BG. The effects of aging, housing and ibuprofen treatment on brain neurochemistry in a triple transgene Alzheimer’s disease mouse model using magnetic resonance spectroscopy and imaging. Brain Res. 2014;1590:85–96. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2014.09.067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]