Abstract

In the sensory epithelium, macrophages have been identified on the scala tympani side of the basilar membrane. These basilar membrane macrophages are the spatially closest immune cells to sensory cells and are able to directly respond to and influence sensory cell pathogenesis. While basilar membrane macrophages have been studied in acute cochlear stresses, their behavior in response to chronic sensory cell degeneration is largely unknown. Here we report a systematic observation of the variance in phenotypes, the changes in morphology and distribution of basilar membrane tissue macrophages in different age groups of C57BL/6J mice, a mouse model of age-related sensory cell degeneration. This study reveals that mature, fully differentiated tissue macrophages, not recently infiltrated monocytes, are the major macrophage population for immune responses to chronic sensory cell death. These macrophages display dynamic changes in their numbers and morphologies as age increases, and the changes are related to the phases of sensory cell degeneration. Notably, macrophage activation precedes sensory cell pathogenesis, and strong macrophage activity is maintained until sensory cell degradation is complete. Collectively, these findings suggest that mature tissue macrophages on the basilar membrane are a dynamic group of cells that are capable of vigorous adaptation to changes in the local sensory epithelium environment influenced by sensory cell status.

Keywords: Macrophage, Hair cells, C57BL/6J, Cochlea, Aging, Immunity

1. Introduction

Under steady-state conditions, mature tissue macrophages are pervasive throughout many cochlear partitions including the stria vascularis, the spiral ligament, the spiral ganglion and the basilar membrane (Hirose et al., 2005; Lang et al., 2006; Okano et al., 2008; Sato et al., 2008; Tornabene et al., 2006; Yang et al., 2015). In the event of cochlear stresses, circulating monocytes infiltrate into the cochlea. Together with mature, fully differentiated tissue macrophages, these cells participate in all phases of pathogenesis.

Our current understanding of macrophage responses to cochlear stresses is derived primarily from studies of acute cochlear pathogeneses including acoustic injury (Fredelius et al., 1990; Hirose et al., 2005; Tornabene et al., 2006; Yang et al., 2015), ototoxicity (Ladrech et al., 2007; Sato et al., 2010), and cochlear implantation (Bas et al., 2015). Within mere hours following acoustic overstimulation, monocytes infiltrate cochlear tissues including the scala vestibuli, modiolous, lateral wall (Du et al., 2011; Hirose et al., 2005; Sautter et al., 2006; Tornabene et al., 2006; Wakabayashi et al., 2010), Reissner’s membrane (Sautter et al., 2006), and the basilar membrane (Tornabene et al., 2006; Yang et al., 2015) with a particularly manifest increase in the monocyte population having been reported in the spiral ligament, scala tympani, and spiral limbus (Du et al., 2011; Hirose et al., 2005; Miyao et al., 2008; Sautter et al., 2006; Tornabene et al., 2006). The pervasive nature of macrophage infiltration into cochlear tissues following damage supports the notion that macrophages play a vital role in cochlear responses to acute cochlear insult.

The infiltrating monocytes transform into activated macrophages locally in the cochlea and express proinflammatory proteins (Yang et al., 2015). While the exact functions of infiltrating macrophages in cochlear responses to stresses are not clear, several studies have suggested distinct roles for macrophages including phagocytosis of cellular materials from damaged or dead hair cells and production of inflammatory molecules (Fredelius et al., 1990; Fujioka et al., 2006; Tornabene et al., 2006).

While macrophage responses to acute cochlear damage have been investigated, the behaviors of macrophages in response to chronic sensory cell degeneration are not fully understood. Chronic sensory cell degeneration differs from acute sensory cell degeneration in many ways. Whereas OHC damage and subsequent monocyte infiltration into the sensory epithelium occur in brief succession to acute cochlear insult, chronic sensory cell degeneration presents with chronic inflammation, a slower progression of OHC loss, and a protracted activated cochlear immune response. Because of these differences, we hypothesize that mature tissue macrophages, and not newly infiltrating macrophage cells, play the dominant role in local cochlear immunity in response to chronic alterations in the local sensory epithelium environment, particularly in reaction to the slow progression of sensory cell degeneration. Due to the important role that the immune response plays in cochlear homeostasis, macrophage activities related to chronic sensory cell degeneration warrant further investigation. Such an undertaking could help shed light on both the functional changes these cells undergo and discrepancies in the cochlear immune response as a function of sensory cell degeneration.

C57BL/6J mice have been employed as an animal model for investigations into age-related sensory cell degeneration (Henry et al., 1980; Hequembourg et al., 2001; Ison et al., 2007; Li et al., 1991; Mikaelian et al., 1974; Shnerson et al., 1981; White et al., 2000; Willott, 1986). This strain of mice contains a naturally-occurring gene associated with age-related hearing loss (Erway et al., 1993). Mice who are homozygous for the Ahl mutation (C57BL/6J) display an early (1–2 months of age) onset of both hearing loss initiating in the high frequencies (Hequembourg et al., 2001) and sensory cell degeneration starting from the basal portion of the cochlea. This sensory cell degeneration progresses toward the apical section of the cochlea with increase in age (Harding et al., 2005; Ou et al., 2000). This slow progression of sensory cell pathogenesis provides an ideal model for investigating how macrophages respond to chronic sensory cell degeneration.

The primary objective of this study was to determine how mononuclear phagocytes beneath the basilar membrane respond to chronic sensory cell pathogenesis. We found dynamic changes in both macrophage morphology and number in the sensory epithelium of aging cochleae. These changes are spatially correlated to the stages of sensory cell degeneration. Importantly, we found that macrophages transform into an activated amoeboid morphology preceding the onset of sensory cell pathogenesis. These results indicate that sensory epithelium macrophages are an immune sensor for sensory cell pathogenesis. Moreover, the finding of proinflammatory activation of macrophages suggests potential roles for these immune cells in modulating hair cell degeneration during age-related cochlear pathogenesis.

2. Experimental Procedures

2.1 Subjects

C57BL/6J mice (The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME, USA) were utilized in this investigation. Both male and female animals were used in the course of this study. Animals were housed at the University at Buffalo’s Lab Animal Facility and were protected from overt noise exposure for the duration of the investigation. Procedures involving the use and care of the animal subjects were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the State University of New York at Buffalo.

2.2 Auditory brainstem responses (ABR)

Auditory brainstem response (ABR) measurements were conducted to assess the auditory function in young 1-month old animals (4–6 weeks) before the onset of sensory cell degeneration, and subsequently in intermediate-aged (3–5 months) and old animals (10–12 months), using a method that was described in our previous publication (Hu et al., 2012). Briefly, an animal was anesthetized with an intraperitoneal injection of a mixture of ketamine (87 mg/kg) and xylazine (3 mg/kg). Body temperature was maintained at 37.5 °C with a warming blanket (Homeothermic Blanket Control Unit; Harvard Apparatus). Stainless-steel needle electrodes were placed subdermally over the vertex (non-inverting input) and posterior to the stimulated and nonstimulated ears (inverting input and ground) of the animal. Elicitation of the ABRs were accomplished with tone bursts at 4, 8, 16, and 32 kHz (0.5 ms rise/fall Blackman ramp, 1 ms duration, alternating phase) at the rate of 21/s. The tone-bursts were generated digitally (SigGen; TDT) using a digital-to-analog converter (100 kHz sampling rate; RP2.1; TDT) and fed to a programmable attenuator (PA5; TDT), an amplifier (SA1; TDT), and a closed-field loudspeaker (CF1; TDT). Electrode outputs were delivered to a preamplifier/base station (RA4LI and RA4PA/RA16B; TDT). Responses were filtered (100–3000 Hz), amplified, and averaged using TDT hardware and software. These responses were then stored and displayed on a computer. The ABR threshold was defined as the lowest intensity that reliably elicited a detectable response.

2.3 Cochlear tissue collection

Cochlear tissues were harvested at three time points, 1 month (4–6 weeks), 3–5 months, or 10–12 months, in a manner reported by Yang et al (2015). Animals were killed by CO2 asphyxiation and subsequently decapitated. The cochleae were quickly removed from the skull and were fixed with 10% buffered formalin overnight. The cochleae were dissected in 10 mM Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) to collect the sensory epithelia for subsequent morphological and biological analyses. Further description of sample preparation and cell composition of the samples is provided in following sections.

2.4 Immunolabeling of macrophage surface markers

The methods for immune cell staining and image capture have been previously described in detail (Yang et al., 2015). Immunolabeling of CD45 protein, a pan-leukocyte marker, was used to identify macrophages and the nature of macrophages was confirmed using a macrophage-specific marker, F4/80. After dissection, sensory epithelium tissues were treated with 0.5% Triton X-100 and 10% donkey or goat serum albumin in PBS (pH 7.4) for 1 hour at room temperature. Tissues were subsequently incubated overnight at 4 °C with a primary antibody (goat CD45 polyclonal antibody, 1:100 AF114, RD Inc., Minneapolis, MN, USA or rat anti-F4/80 monoclonal antibody [CI:A3-1] 1:150, ab6640, Abcam Inc., Cambridge, MA, USA). After incubation with the primary antibody, the tissues were rinsed with PBS (3x) and incubated in the dark with a secondary antibody (CD45 staining: Alexa Fluor® 488 donkey anti-goat IgG, 1:100 in PBS, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA; F4/80 staining: Alexa Fluor® 488 or 594 donkey anti-rat IgG, 1:100 in PBS, Invitrogen) for 2 hours at room temperature. After secondary antibody incubation, the samples were rinsed in PBS and then mounted on slides with an antifade medium (Prolong® Gold antifade reagent, Invitrogen). In order to determine nuclear morphology, certain tissues were counterstained with a nuclear dye, propidium iodide (5 μg/ml in PBS) or DAPI (1 μg/ml in PBS).

The specificity of the primary antibodies used in this study has been previously confirmed by Yang et al. (2015): Western blotting was used to confirm the molecular weights of the proteins targeted by the CD45 antibody using spleen and lymph node tissues. To prevent false-positive identifications due to non-specific labeling of the secondary antibodies, certain samples were incubated with only the secondary antibodies. No clear fluorescence in the tissues was found.

2.5 Determination of sensory cell damage

The assessment of sensory cell damage was accomplished by means of the procedure also reported in Yang et al. (2015). The pattern of sensory cell damage was determined by quantifying the number of missing OHCs along the sensory epithelium from the apex to the base of the cochlea. Tissue collection was undertaken at the three time points already described. After cochlear dissection in PBS, the sensory epithelium surface preparations were incubated with the staining solution containing Alexa Fluor 488 phalloidin (1:75; Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA USA) in 10 mM PBS at room temperature in the dark for 30 minutes. After the staining, the tissue was mounted on a slide.

2.6 Tissue observation and image capture

The tissues were examined using an epifluorescence illumination microscope (Z6 APO apochromatic zoom system) equipped with a digital camera (DFC3000 G microscope camera) that was controlled by Leica Application Suite V4 PC-based software (Leica Microsystems, Buffalo Grove, IL, USA). The entire length of the sensory epithelium was photographed. To observe detailed structural changes, certain samples were further examined and photographed using a confocal microscope (LSM510 multichannel laser scanning confocal image system) with associated ZEN Blue 2012 image processing software (Zeiss, Thornwood, NY, USA) utilizing a methodology previously reported (Cai et al., 2014). The collected images were processed to improve the clarity of cells. Specifically, we used the functions of image adjustment offered in Adobe Photoshop CS6 (version 13.0.1, Adobe Systems, San Jose, CA, USA) to enhance image contrast.

2.7 Qualitative and quantitative analysis of macrophage morphology and distribution along the basilar membrane

Macrophages were identified based on their shapes and sizes. These cells are larger than other types of leukocytes and have unique shapes including dendritic and amoeboid shapes, or an irregular shape with projections. Visualization of these cells were achieved using CD45 immunostaining. The nature of macrophages was further confirmed using F4/80 immunostaining.

Basilar membrane macrophages, identified as a distinct subset of cochlear macrophages, were distinguished from neighboring macrophages (e.g., lateral wall macrophages and modiolus macrophages) using the following methods. Bright-field illumination was employed when observing cells under epifluorescence illumination microscopy which provided clear visual distinction between the sensory epithelium and surrounding cochlear tissues (e.g., lateral wall and modiolus). During confocal microscopy, the application of differential interference contrast (DIC) provided clear visualization of tissue orientation which allowed for easy identification of basilar membrane tissues. Only macrophages situated within basilar membrane tissues were evaluated for our investigation. Macrophage phenotype and distribution were evaluated and described per the following criteria. General shape. A qualitative description of immune cell morphology was conducted: e.g., dendritic, amoeboid, transitionary. Cell Size. Measurement of cell size was achieved using Adobe Photoshop to trace cell membrane boundaries. The area contained within each outlined cell was calculated and employed as a metric to estimate cytoplasmic cell area. For each tissue specimen, the area of the five largest cells was averaged to provide a single representative number for each individual cochlea. Identification of basilar membrane locality at which morphological changes become observable. This was described in terms of both a percentage of distance from the apical extreme and as an absolute length (in μm) from this same starting location.

2.8 Data analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using SigmaPlot (version 10.0.1.25, San Jose, CA, USA). An α-level of 0.05 was chosen to denote significance for all statistical tests. To determine the distribution, morphology, and additional physiological characteristics of specific cells, we surveyed cells of interest which had been positively stained with known specific protein markers (Phalloidin for OHCs and CD45 for macrophages). Positive cells were identified and distinguished from surrounding cochlear tissue by their ability to exhibit strong staining patterns in relation to adjacent cells. Distribution cochleograms and macrophage-grams were generated by quantifying the number of cells present per unit length along the basilar membrane (150 μm for sensory cells and 450 μm for immune cells). The mean for these counts was then computed to produce an average value per unit length. Subsequently, each given unit of length was then converted to a percent distance of the total expanse of the basilar membrane from the apical extreme to the basal terminus (approximating 6000 μm). For OHCs in particular, we undertook the additional step of converting the absolute number of missing cells to percentile of sensory cell loss per unit length. Group means were acquired by averaging cell counts per unit across specimens for each age group. Comparisons of cellular morphology and cell density across the length of the cochlea from apex to basal extreme was made possible by dividing cochleae into an apical (approximately 0–50%) and basal sections (50–100% distance from the apex). Student’s t test was employed when comparing any two experimental groups (e.g., young vs. aged cochleae). A one-way ANOVA was utilized when analyzing variation among three or more groups when examining one parameter condition at a time.

ABR results were evaluated with the application of a two-way ANOVA to define the interplay between stimulus frequency and the three subject age groups. The correlation between immune cell size and the number of missing sensory cells was determined with the Pearson product moment correlation coefficient aimed at revealing the linear relationship between these two variables.

3. Results

3.1 Degeneration of sensory cells in the basal portion of the sensory epithelium with advancing age

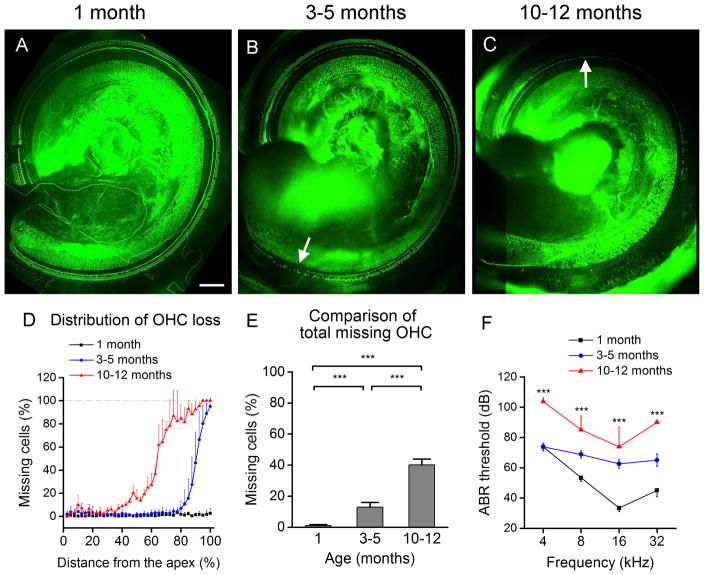

To provide a context for interpreting the findings of macrophage activities in aging cochleae, we examined the integrity of sensory cells using phalloidin labeling of f-actin in the cuticular plates of hair cells. Loss of cuticular plates demonstrates substantial detriment to the sensory cells, and this method was employed to assess the degree of sensory cell damage. We found an age-related sensory cell degeneration initiating at the basal extreme of the sensory epithelium which progresses apically with aging (Figs. 1A–D). In young mice (1 month), little to no sensory cell loss was found throughout the entire organ of Corti. Intermediate-aged mice (3–5 months) displayed the early onset of sensory cell loss beginning in the basal extreme of cochleae. By 10–12 months of age, sensory cell lesions further expanded with complete OHC loss in the region approximately 80–100% from the apex and near-complete to intermittent cell loss in the region about 60–80% distance from the apex. This increase in the numbers of missing cells is statistically significant in both the 3–5 month and 10–12 month groups (Fig. 1E, One-way ANOVA, F (2, 34) = 343.8, P = <0.001, Tukey post-hoc all pairwise multiple comparison, 10–12 months vs. 1 month, q = 36.83, P = <0.001, 10–12 months vs. 3–5 months, q = 26.77, P = <0.001, 3– 5 months vs. 1 month, q = 17.94, P = <0.001). The finding of the base-dominated sensory cell degeneration in C57BL/6J mice is consistent with the findings of previous studies (Henry et al., 1980; Spongr et al., 1997).

Figure 1.

Age-related cochlear degeneration in C57BL/6J mice. (A–C) Typical images of F-actin staining using Alexa 488-labeled phalloidin in hair cells approximately 50–100% distance from the apex where hair cell degeneration occurs. The young 1 month old cochlea (A) shows little to no sensory cell loss. The 3–5 month old cochlea (B) displays the loss of sensory cells pointed to by the arrow in the basal extreme around 80–100% distance from the apex. The 10–12 month old cochlea (C) presents with extensive OHC loss in the basal extreme and near-complete to intermittent OHC loss 60–80% distance from the apex (pointed to by the arrow). Scale bar = 100 μm. (D) The cochleogram showing the distribution of OHC damage along the basilar membrane for young (n = 13), intermediate-aged (n = 20) and old (n = 4) mice. Notice that progressive OHC loss starts from the basal end of the cochlea. (E) Comparison of the total number of missing OHCs among the three age groups. A significant increase in the number of missing OHCs is observed with advancing age (One-way ANOVA, F (2, 34) = 343.8, P = <0.001, Tukey post-hoc all pairwise multiple comparison. *** P = <0.001). (F) Comparison of ABR thresholds at the 4 tested frequencies among the three age groups (1 month, n = 12; 3–5 months, n = 4; 10–12 months, n = 4). The thresholds are significantly elevated above baseline with an increase in age (Two-way ANOVA, F (2, 68) = 14.1, P = <0.001, Holm-Sidak post-hoc method for all pairwise comparisons, 10–12 months vs. 1 month, P < 0.001, 3–5 months vs. 1 month, P = 0.005).

We further examined ABR thresholds at the frequencies 4, 8, 16 and 32 kHz to assess auditory function. We found an average threshold shift of 16.1 ± 3.0 dB beginning at the middle and high frequencies (8–32 kHz) for 3–5 month old mice. The shift expanded to the lowest tested frequency (4 kHz) and the level of the shift was increased to 36.8 ± 6.2 dB for 10–12 month old mice (Fig. 1F, Two-way ANOVA, F (2, 68) = 14.1, P = <0.001, Holm-Sidak post-hoc method for all pairwise comparisons, 10–12 months vs. 1 month, P < 0.001, 3–5 months vs. 1 month, P = 0.005). This high frequency-dominated auditory dysfunction is consistent with the basal sensory cell degeneration. Together, the pathological and functional assessments revealed a basal-to-apical sensory cell pathogenesis and a high-to-low frequency loss of hearing sensitivity in aging C57BL/6J mice.

3.2 Site-specific diversity in macrophage morphology

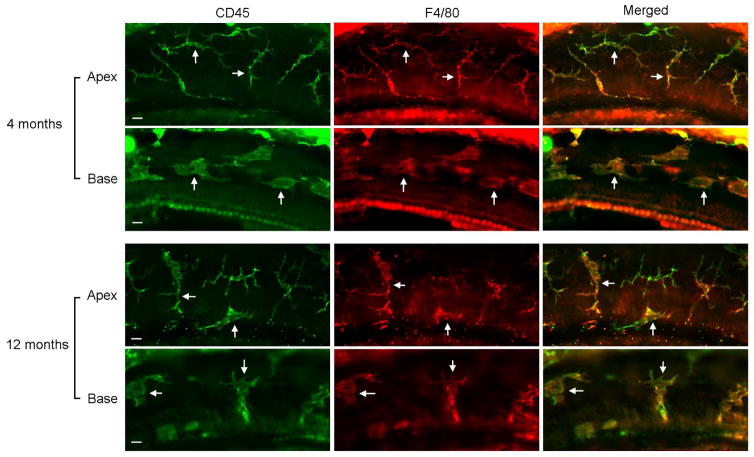

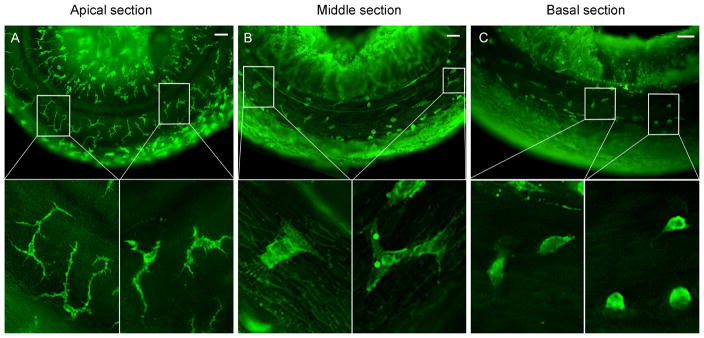

Basilar membrane macrophages were identified using immunostaining of CD45, a pan-leukocyte marker (Morris et al., 1991), and were confirmed in certain samples using immunolabeling of F4/80, a macrophage-specific marker (Fig. 2). The macrophages were found on the scala tympani side of the basilar membrane. Under normal conditions, these macrophages display a site-specific diversity in their morphological phenotypes. The apical region of the sensory epithelium (0–30% distance from the apex) is dominated by dendritic macrophages with a slim body and multiple long projections (Fig. 3A). The intermediary region approximating 30–70% distance from the apex features macrophages with a dendritic-to-amoeboid transitional phenotype (Fig. 3B). The basal region of the sensory epithelium (70–100% distance from the apex) is characterized by macrophages with an amoeboid morphology (Fig. 3C). These observations are consistent with the findings of the macrophage diversity described in our previous publication (Yang et al., 2015).

Figure 2.

Colocalization of CD45 (a pan-leukocyte marker) and F4/80 (a macrophage specific marker) immunoreactivity in the immune cells of the basilar membrane. The tissues were collected from a cochlea of a 4-month old mouse and a cochlea of a 12-month old mouse. Notice that in both the apical and basal regions of the basilar membrane, cells that have the macrophage morphology display both the CD45 and F4/80 immunoreactivity. This observation indicates that these cells are macrophages. Bar = 20 μm.

Figure 3.

CD45 immunolabeling of tissue basilar membrane macrophages in young, 1 month old cochleae demonstrating site-specific morphology. (A) Apical sections (0–30% distance from the apex) present with ramified, dendritic macrophages. (B) In the middle region of the sensory epithelium (30– 70% distance from the apex), macrophages display a dendritic-to-amoeboid transitionary phenotype. (C) Basal portions (70–100% distance from the apex) are dominated by macrophages with an amoeboid morphology. The insets show the high-magnification view of typical cells in each section. Scale bars = 75 μm.

3.3 Activation of basilar membrane macrophages in aging cochleae

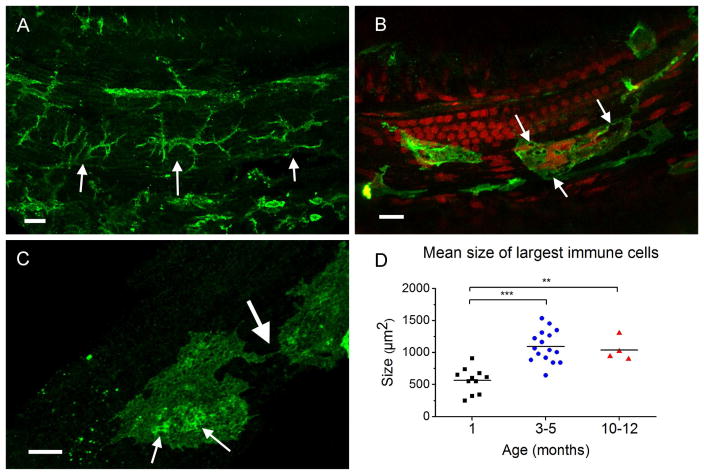

To define age-related changes in macrophage activity, we examined the macrophage morphology, an essential indicator of macrophage activation. In aging cochleae, apical sections continued to feature ramified cells exhibiting a dendritic shape (Fig. 4A) with no significant change in morphology as compared to young specimens. However, macrophages in the middle and basal regions of the sensory epithelium displayed enlarged cell bodies and a grainy appearance with easily visible vacuoles and numerous particulate inclusions (Figs. 4B and 4C). Further, certain macrophages were observed to have processes projecting toward adjacent macrophages (larger arrow, Fig. 4C), and giant macrophages with irregular-shaped nuclei (Fig. 4B) were also observed. These changes were observed in both the 3–5 month and 10–12 month group samples.

Figure 4.

Macrophage morphology of aging cochlea. (A) The typical macrophage morphology in the apical section of a cochlea collected from a 5 month old mouse. The macrophages maintain their dendritic shape with narrow bodies and slim projections. Scale bar = 20 μm. (B) Typical macrophages in the middle and basal portion of the sensory epithelium of a 5 month old mouse. The arrows point to numerous vacuoles of various sizes located within an amoeboid macrophage showing an enlarged body and grainy cytoplasm. Scale bar = 20 μm. (C) Image showing macrophages with particulate inclusions indicated by the smaller arrows. The larger arrow points to the site where two macrophages have established a physical contact. Scale bar = 10 μm. (D) Comparison of macrophage sizes among the three age groups. Both intermediate-aged (n = 16) and old (n = 4) cochleae exhibit a significant increase in macrophage size compared to young healthy cochleae (n = 11) (One-way ANOVA, F (2, 28) = 19.3, P < 0.001, Tukey post-hoc all pairwise multiple comparison. *** P < 0.001, ** P = 0.003).

To quantify the morphological change, we compared the sizes of macrophages among the three age groups. The average size of macrophages in the 1 month old cochleae (564.0 ± 194.5 μm2) was significantly smaller than those of the macrophages in both the 3–5 month and the 10–12 month cochleae (1094.3 ± 247.4 μm2 and 1038.4 ± 182.6 μm2; One-way ANOVA, F (2, 28) = 19.3, P < 0.001, Tukey post-hoc all pairwise multiple comparison, 3–5 months vs. 1 month, q = 8.58, P < 0.001, 10–12 months vs. 1 month, q = 5.15, P = 0.003; Fig. 4D).

As in young cochleae, aging cochleae had a few CD45-positive cells showing a small round shape that is the monocyte phenotype. The number of these cells was found to be similar between the young and the aging samples, suggesting that the aging basilar membrane lacks the infiltration of monocytes. Collectively, our observations reveal site-specific changes in macrophage morphology, and this morphological transformation is a sign of macrophage activation (Davis et al., 1994; Raivich et al., 1999; Stence et al., 2001; Young et al., 1969).

3.4 Age-related changes in macrophage numbers

To further define the age-related changes in macrophage activity, we quantified the number of CD45-positive cells as a function of the distance from the apex to the base of the basilar membrane. These numbers were compared among the three age groups.

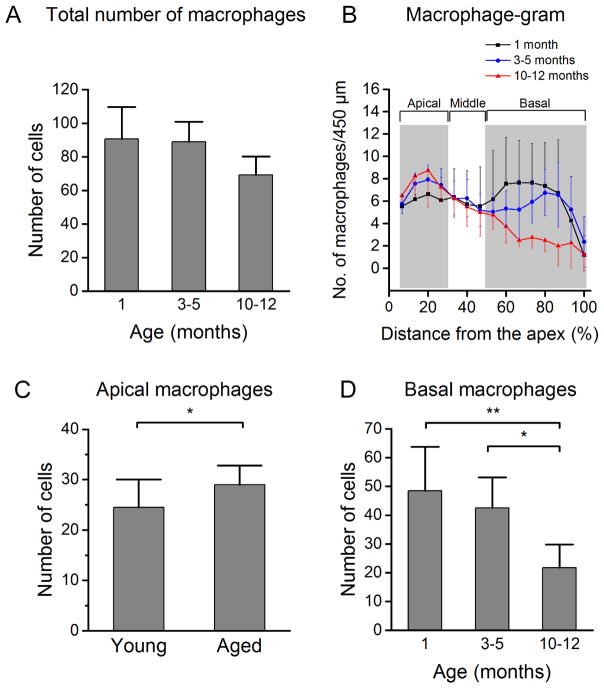

As compared with the young cochleae, the average number of macrophages per cochlea remained unchanged in the 3–5 month group and was decreased in the 10–12 month group (Fig. 5A). However, the change was not statistically significant (One-way ANOVA, P > 0.05). Further analysis of the macrophage-gram revealed a heterogeneous change in macrophage numbers along the gradient of the sensory epithelium (Fig. 5B). In the apical section of the sensory epithelium (0–30% from the apex), the average number of macrophages increased from 25 ± 6 at the age of 1 month to 29 ± 3 at the age of 3–5 months and 30 ± 6 at the age of 10–12 months. The difference between the young and the aging cochleae is statistically significant (Fig. 5C, Student’s t test, t (29) = −2.71, P = 0.011). In contrast to the apical section, the middle section showed no change in the number of macrophages in both aging groups (Fig. 5B, see the section marked by Middle).

Figure 5.

Age-related changes in macrophage numbers. (A) Comparison of the total number of macrophages across the entire length of the sensory epithelium among the three age groups (1 month, n = 11; 3–5 months, n = 16; 10–12 months, n = 4). While there is a trend of reduction with an increase in age, the change is not statistically significant (One-way ANOVA, P > 0.05). (B) Macrophage-gram showing the distribution of macrophages spanning the full length of the basilar membrane. Note the non-homogeneous change in macrophage number in different regions of the sensory epithelium as a result of advancing age. (C) Comparison of the total numbers of macrophages in the apical section between the young (1 month) and aging cochleae (3–12 months). The number is significantly increased in aged compared to young cochleae (Student’s t test, t (29) = −2.71, * P = 0.011). (D) Comparison of the total numbers of macrophages in the basal portion. A progressive reduction in macrophage numbers occurs among age groups, and this reduction is statistically significant (One-way ANOVA, F (2, 28) = 7.1, P = 0.003, Tukey post-hoc all pairwise multiple comparison, ** P = 0.002, * P = 0.014).

The basal section of the sensory epithelium (50–100% distance from the apex) exhibited a decline in the total number of macrophages with advancing age. The average number of mature tissue macrophages was reduced from 49 ± 15 observed for the young group to 43 ± 11 for intermediate-aged group, and further down to 22 ± 8 for the 10–12 month group (Fig. 5D, One-way ANOVA, F (2, 28) = 7.1, P = 0.003, Tukey post-hoc all pairwise multiple comparison, 10–12 months vs. 1 month, q = 5.30, P = 0.002, 10–12 months vs. 3–5 months, q = 4.27, P = 0.014). This result suggests a site-dependent reorganization of macrophage quantities in the basilar membrane as age increases.

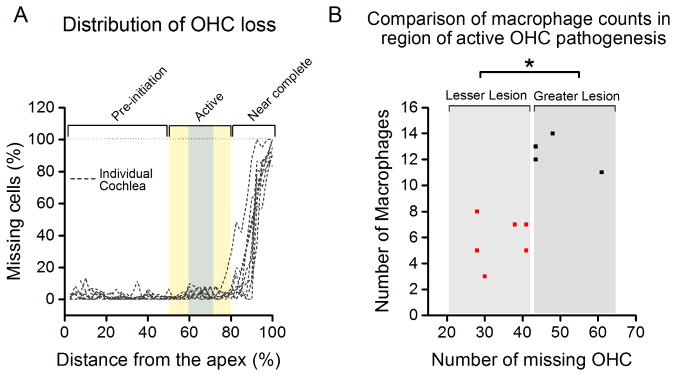

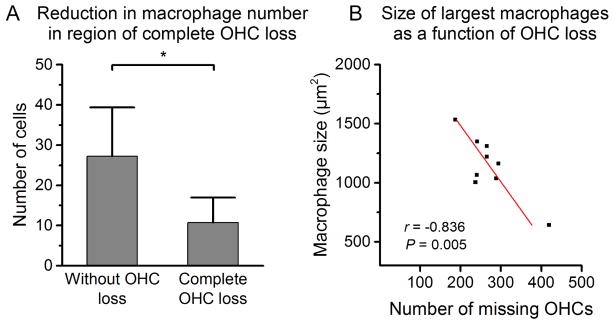

3.5 Enhanced macrophage activity in the region of active sensory cell degeneration

We sought to determine how the changes in macrophage activities were correlated to the activity of sensory cell pathogenesis. To this end, we divided the sensory epithelium into three anatomic zones representing three stages of sensory epithelium pathogenesis: pre-initiation, active (on-going), and complete (Fig. 6A). The pre-initiation stage represents early sensory cell degeneration before the onset of hair cell death. The completed stage denotes the terminating stage of sensory cell lesions that has culminated in complete or near complete sensory cell degradation. The active stage represents active sensory cell degeneration where the onset of hair cell loss is rapidly commencing in the intervening region between the zones comprising the pre-initiation stage and the complete stage.

Figure 6.

(A) Three stages of sensory cell pathogenesis: pre-initiation, active and near complete. The data are derived from cochleograms showing the distribution of OHC loss for ten 3–5 month old cochleae. The number of missing OHC was calculated in the center region of active sensory cell degeneration (gray shaded region). This area was selected for the analysis of macrophage numbers (acquired from the immediately surrounding regions, shaded yellow) in cochleae demonstrating either greater or lesser OHC lesion for Fig. 6B. (B) Comparison of macrophage counts in the basilar membrane regions with greater and lesser OHC loss. The levels of OHC damage were quantified in the basilar membrane region that displayed the active sensory cell pathogenesis (marked with light gray in Fig. 6A). The macrophages we quantified are all located in and around the region of active sensory cell pathogenesis (marked with yellow and light gray in Fig. 6A). Cochleae with a greater number of missing OHCs (black dots, n = 4) exhibit a greater quantity of macrophages when compared to cochleae with lesions of less severity (red dots, n = 6) (Student’s t test for missing OHC comparison, t (8) = 3.98, ** P = 0.004; Student’s t test for macrophage comparison, t (8) = -2.50, * P = 0.037). This observation suggests that a greater degenerative activity of sensory cells leads to greater macrophage activity.

We quantified the number of missing OHCs in the central region of the active zone of sensory cell pathogenesis (see the gray shaded area in Fig. 6A) for 10 cochleae from which corresponding macrophage numbers were also collected. Based on the numbers of missing OHCs, the cochleae were divided into two groups, the lesser damage group and the greater damage group, and the two groups displayed a significant difference in the average numbers of missing OHCs (Fig. 6B, Student’s t test, t (8) = −2.50, P = 0.037). We then quantified the number of macrophages present in the same and immediately surrounding region of the basilar membrane where these fresh lesions were initiating (see the yellow shaded area in Fig. 6A). As expected, the cochleae with greater OHC lesions displayed statistically more mature tissue macrophages than the cochleae with less severe OHC lesions, and this difference is significant (Fig. 6B, Student’s t test, t (8) = 3.98, P = 0.004). This observation suggests that active sensory cell degeneration leads to enhanced macrophage activity, and therefore, a more robust immune response.

3.6 Reduction in macrophage activity in the sensory epithelium region showing complete OHC degradation

We further quantified the number of macrophages in the cochlear region displaying the complete stage of sensory cell degeneration (see Fig. 6A), and found a significant reduction in the number of macrophages as compared to the number of macrophages in the same region of young cochleae where no OHC lesion was found (Fig. 7A, Student’s t test, t (13) = 2.54, * P = 0.025). This observation suggests that macrophage activity is reduced once sensory cell degradation is completed.

Figure 7.

(A) Comparison of macrophage numbers between the basilar membrane regions exhibiting no OHC loss (n = 11) and the regions showing complete or near complete OHC loss (n = 4). The number of macrophages in the region showing complete or near complete OHC loss is significantly reduced (Student’s t test, t (13) = 2.54, * P = 0.025). (B) Correlation between the size of the five largest immune cells per cochlea and the number of missing OHCs in the sensory epithelium region 50–100% distance from the apex. As the magnitude of OHC loss increases along the sensory epithelium, the average size of mature tissue macrophages decreases (Pearson product moment correlation, r = −0.836, P = 0.005).

To provide further evidence for the reduction in macrophage activity, we performed a correlation analysis to determine how macrophage size changed as a function of the number of missing OHCs, a parameter for the size of OHC lesions, in the basal 50% of the sensory epithelium. We found that the two parameters were negatively correlated (Fig. 7B, Pearson product moment correlation, r = − 0.836, P = 0.005), indicating that macrophage size decreases as the size of OHC lesions increases. This result is consistent with the finding that macrophage number decreased in the region where OHC degradation is completed. These observations suggest that macrophage activity diminishes as sensory cell pathogenesis has reached the complete stage of OHC loss.

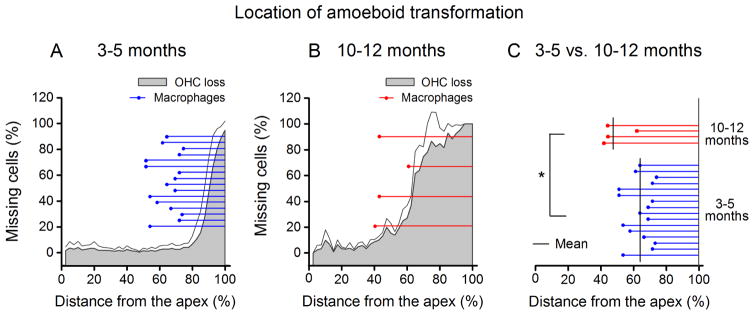

3.7 Amoeboid transformation precedes the onset of sensory cell death

We sought to determine how the amoeboid transformation of macrophages, a sign of macrophage activation, is spatially correlated to the progression of sensory cell lesions as they advance apically. The distance along the basilar membrane from the apical extreme to the nearest amoeboid macrophages was measured in 31 cochleae. In both the 3–5 and 10–12 month groups, the distribution of amoeboid macrophages was more apical than that of OHC lesions (Figs. 8A and 8B). The average percent-distance from the apex to the nearest amoeboid macrophage was 62.6 ± 8.0% in the 3–5 month group. The distance was reduced to 46.3 ± 9.2% in the 10–12 month group (Fig. 8C, Student’s t test, t (29) = −2.71, P = 0.011). These results demonstrate that activation of macrophages occurs in the sensory epithelium area ahead (more apical) of regions presenting with substantial sensory cell death.

Figure 8.

The spatial relationship between the site of amoeboid macrophages and the site of OHC loss in 3–5 month old (A) and 10–12 month old cochleae (B). Note that the most-apical locality of amoeboid cells (indicated by the left-end blue and red dots of the lines) appears more apical to the site of the cochlear region demonstrating any degree of sensory cell pathogenesis (gray shaded area). Each blue or red line projecting to the right of each dot shows the distance along the basilar membrane where amoeboid cells are found. Each blue or red line represents a single cochlea. The thin gray line above the gray shaded area represents standard deviation of OHC loss. (C) Comparison of the distribution areas of amoeboid macrophages between the 3–5 month group and the 10–12 month group. The mean location of the most apical amoeboid cell for both age groups is indicated by vertical black lines. Macrophage transformation into an amoeboid phenotype was observed to advance apically in 10–12 month old cochleae (n = 4) when compared to 3–5 month old (n = 16) specimens, and this difference is significant (Student’s t test, t (29) = −2.71, P = 0.011).

4. Discussion

The goal of the current investigation is to determine how basilar membrane macrophages respond to chronic sensory cell degeneration in a mouse model of age-related sensory cell degeneration. We reveal four major findings. First, it is mature, fully differentiated tissue macrophages that are the major type of macrophage populations responsible for the cochlear immune response in age-related hair cell degeneration, and newly infiltrated monocytes are rare. Second, the mature tissue macrophages display a site-dependent change in their morphology and numbers and these changes are related to the dynamic progression of sensory cell degeneration. Third, apical and basal macrophages display different phenotypes under steady state conditions and have different response patterns to sensory cell degeneration. Finally, mature tissue macrophages are a sensitive internal sensor for early sensory cell degeneration. Together, these results suggest that the macrophage-mediated immune response is an integral part of the cochlear response to age-related chronic sensory cell degeneration.

4.1 Why are basilar membrane macrophages examined?

Mature tissue macrophages have been identified in the cochlea under both normal and pathological conditions. Though these cells are present in multiple sites within the cochlea, our study focused specifically on basilar membrane macrophages positioned immediately beneath the organ of Corti on the scala tympani side of the basilar membrane. This decision was made with the following two conditions. First, the basilar membrane macrophages are in closest proximity to the sensory cells and therefore are more prone to hair cell-related activation. This notion is supported by our finding of robust activation of basilar membrane macrophages in reaction to the insidious progression of sensory cell degeneration. Second, macrophages in this region reside on the flat surface of the basilar membrane, facilitating a detailed analysis of cell morphology using confocal microscopy. With this experimental paradigm, we were able to make multiple novel findings.

4.2 Difference in macrophage responses between acute and chronic sensory cell damage

Our study reveals the major difference between macrophage responses provoked by acute and by chronic cochlear pathogeneses. In the event of acute sensory cell damage induced by ototoxicity, immune challenge or acoustic injury, a large number of undifferentiated monocytes from circulation expeditiously infiltrate into the cochlea (Hirose et al., 2005; Kaur et al., 2015; Okano et al., 2008; Shi, 2010; Tornabene et al., 2006; Yang et al., 2015). Therefore, infiltrated macrophages are the major executor for the immune activities, including phagocytosis of broken-down cellular material (Fredelius et al., 1990) and inflammatory molecule production (Fujioka et al., 2006; Gloddek et al., 2002; Tornabene et al., 2006; Yang et al., 2015). In contrast, in the event of chronic sensory cell degeneration, the immune response is fulfilled primarily by mature tissue macrophages. This conclusion is supported by our finding that, in aging sensory epithelia, infiltrating monocytes are rare and that mature tissue macrophages display strong reaction to age-related degeneration. This finding emphasizes the importance for mature tissue macrophages in chronic sensory cell pathogenesis.

4.3 Macrophage activity is correlated to the stages of the progression of sensory cell lesions

We sought to uncover how macrophage activity is influenced by the progressive stages of sensory cell pathogenesis. OHC loss in our animal model initiates in the basal portion of the cochlea and proceeds apically until the lesion reaches 60% distance from the apex by approximately one year of age. Based on this pattern of lesion growth, we categorize the sensory cell pathogenesis into three stages: pre-initiation, active and complete (See Fig. 6A). We reveal that macrophage activities are modulated by these three stages of hair cell pathogenesis. In the region showing the advanced pathology featuring completion or near completion of sensory cell degradation, the number and the size of macrophages are reduced. This suggests that macrophage activity requires signals from sensory cells. Once sensory cell loss is completed, the biological incentive for macrophage activity diminishes.

The sensory epithelium section featuring the active stage of sensory cell degeneration is located in the juncture between the regions of severe and minor sensory cell loss. It is not surprising that the macrophage number in this region is positively related to the level of sensory cell loss because more active sensory cell degradation provokes greater macrophage activity. The tendency for immune cells to congregate in greater numbers in the vicinity of more active lesions is likely related to localized enhancement of molecular signaling linking macrophage activity to sensory cell status. Macrophage detection of sensory cell degradation is likely to be mediated in part by Tlr4, a membrane receptor that is capable of binding either extrinsic molecules from bacteria or intrinsic molecules from damaged tissues. This speculation is made based on our recent finding that Tlr4 is expressed in basilar membrane macrophages and that Tlr4 knockout suppresses the production of inflammatory mediators such as Il6 and inhibits the expression of major histocompatibility complex II, an antigen presentation molecule in macrophages (Cai et al., 2014; Vethanayagam et al., 2016).

An unexpected finding of the current study is that activation of macrophages as evidenced by amoeboid transformation occurs in the sensory epithelium region where sensory cell lesions are yet to initiate. This early activation of macrophages suggests that macrophage activation precedes sensory cell death, which in turn suggests that early changes in the immune environment could serve as a triggering event for sensory cell pathogenesis. While we do not have further evidence to support this speculation, our study reveals that macrophage activity in the sensory epithelium is closely related to the progressive status of sensory cell pathogenesis.

4.4 Potential roles for macrophages in sensory cell pathogenesis?

The finding of macrophage activity raises an important question as to the functional roles for mature tissue macrophages in sensory cell pathogenesis. In non-cochlear tissues, macrophages perform essential functions related to tissue homeostasis and pathogenesis. For example, microglia, the resident macrophages in the brain, have been shown to play a complex role of either neuroprotection or destructive neuronal necrosis and apoptosis, depending on the degree of neurodegenerative insult (Aschner et al., 1999; Banati et al., 1993; Bruce-Keller, 1999). Many parallels can be drawn between microglia and mature tissue macrophages of the cochlear sensory epithelium. Microglia are present as several different phenotypes with each individual morphology believed to perform a distinct immunological function (Davis et al., 1994; Raivich et al., 1999). Our results reveal a site-dependent morphology of basilar membrane macrophages, suggesting a manifest immune capacity for cells of a dendritic shape versus amoeboid cells. While mature dendritic mononuclear phagocytes represent primarily latent immune cells engaged in monitoring the local tissue environment (Kreutzberg, 1996), cells of an amoeboid morphology have been demonstrated to epitomize a highly activated immune cell state (Kloss et al., 1999; Peters et al., 1979; Stence et al., 2001; Vaughan et al., 1974; Young et al., 1969). Here we present evidence of site-dependent activation of amoeboid macrophages in regions of the sensory epithelium associated with substantial OHC loss, suggesting that amoeboid macrophages are activated in response to sensory cell status in the local environment. Scrutinizing these amoeboid cells in older specimens revealed extensive morphological transformations associated with the induction of proinflammatory mediators. Based on these findings, we suspect that macrophages contribute to deterioration of the sensory cell microenvironment. This speculation is further supported by the finding that active macrophage transformation occurs in the region of the sensory epithelium where sensory cell degeneration has not yet initiated. Our findings suggest that macrophage activities serve as a contributing factor for sensory cell pathogenesis, which warrants further investigations.

4.5 Summary

Our study reveals that mature tissue macrophages in the sensory epithelium are a group of plastic immune cells capable of vigorous adaptation to changes in the local sensory epithelium environment influenced by sensory cell status. This nature of macrophages enables them to serve as a sensitive immune sensor for sensory cell homeostasis. Moreover, the finding of macrophage activation during age-related sensory cell degeneration suggests potential roles for these immune cells in modulating hair cell degeneration. Further studies are warranted to elucidate the molecular mechanisms for regulating macrophage activity and the functional role of macrophage activity in cochlear sensory cell pathogenesis.

HIGHLIGHTS.

Chronic cochlear degeneration activates basilar membrane macrophages.

The activation pattern is affected by the phases of hair cell pathogenesis.

Macrophage activation precedes sensory cell pathogenesis.

Apical versus basal macrophages exhibit different immune response patterns.

Mature tissue macrophages are an immune sensor for chronic hair cell degeneration.

Acknowledgments

Research reported in this publication was supported by National Institutes on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders of the National Institutes of Health under award number: R01DC010154 (BHH).

Abbreviations

- ABR

auditory brainstem response

- Ahl

age related hearing loss gene

- CD45

cluster of differentiation 45

- F-actin

filamentous actin

- NIHL

noise-induced hearing loss

- OHC

outer hair cell

- PBS

phosphate-buffered saline

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Aschner M, Allen JW, Kimelberg HK, LoPachin RM, Streit WJ. Glial cells in neurotoxicity development. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 1999;39:151–73. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.39.1.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banati RB, Gehrmann J, Schubert P, Kreutzberg GW. Cytotoxicity of microglia. Glia. 1993;7:111–8. doi: 10.1002/glia.440070117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bas E, Goncalves S, Adams M, Dinh CT, Bas JM, Van De Water TR, Eshraghi AA. Spiral ganglion cells and macrophages initiate neuro-inflammation and scarring following cochlear implantation. Front Cell Neurosci. 2015;9:303. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2015.00303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruce-Keller AJ. Microglial-neuronal interactions in synaptic damage and recovery. J Neurosci Res. 1999;58:191–201. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4547(19991001)58:1<191::aid-jnr17>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai Q, Vethanayagam RR, Yang S, Bard J, Jamison J, Cartwright D, Dong Y, Hu BH. Molecular profile of cochlear immunity in the resident cells of the organ of Corti. Journal of Neuroinflammation. 2014;11:173. doi: 10.1186/s12974-014-0173-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis EJ, Foster TD, Thomas WE. Cellular forms and functions of brain microglia. Brain Res Bull. 1994;34:73–8. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(94)90189-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du X, Choi CH, Chen K, Cheng W, Floyd RA, Kopke RD. Reduced formation of oxidative stress biomarkers and migration of mononuclear phagocytes in the cochleae of chinchilla after antioxidant treatment in acute acoustic trauma. International journal of otolaryngology. 2011;2011:612690. doi: 10.1155/2011/612690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erway LC, Willott JF, Archer JR, Harrison DE. Genetics of age-related hearing loss in mice: I. Inbred and F1 hybrid strains. Hear Res. 1993;65:125–32. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(93)90207-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredelius L, Rask-Andersen H. The role of macrophages in the disposal of degeneration products within the organ of corti after acoustic overstimulation. Acta oto-laryngologica. 1990;109:76–82. doi: 10.3109/00016489009107417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujioka M, Kanzaki S, Okano HJ, Masuda M, Ogawa K, Okano H. Proinflammatory cytokines expression in noise-induced damaged cochlea. Journal of Neuroscience Research. 2006;83:575–583. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gloddek B, Bodmer D, Brors D, Keithley EM, Ryan AF. Induction of MHC class II antigens on cells of the inner ear. Audiol Neurootol. 2002;7:317–23. doi: 10.1159/000066158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harding GW, Bohne BA, Vos JD. The effect of an age-related hearing loss gene (Ahl) on noise-induced hearing loss and cochlear damage from low-frequency noise. Hearing Research. 2005;204:90–100. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2005.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry KR, Chole RA. Genotypic differences in behavioral, physiological and anatomical expressions of age-related hearing loss in the laboratory mouse. Audiology. 1980;19:369–83. doi: 10.3109/00206098009070071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hequembourg S, Liberman MC. Spiral ligament pathology: a major aspect of age-related cochlear degeneration in C57BL/6 mice. J Assoc Res Otolaryngol. 2001;2:118–29. doi: 10.1007/s101620010075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirose K, Discolo CM, Keasler JR, Ransohoff R. Mononuclear phagocytes migrate into the murine cochlea after acoustic trauma. The Journal of Comparative Neurology. 2005;489:180–194. doi: 10.1002/cne.20619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu BH, Cai Q, Hu Z, Patel M, Bard J, Jamison J, Coling D. Metalloproteinases and Their Associated Genes Contribute to the Functional Integrity and Noise-Induced Damage in the Cochlear Sensory Epithelium. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2012;32:14927–14941. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1588-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ison JR, Allen PD, O’Neill WE. Age-related hearing loss in C57BL/6J mice has both frequency-specific and non-frequency-specific components that produce a hyperacusis-like exaggeration of the acoustic startle reflex. J Assoc Res Otolaryngol. 2007;8:539–50. doi: 10.1007/s10162-007-0098-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaur T, Zamani D, Tong L, Rubel EW, Ohlemiller KK, Hirose K, Warchol ME. Fractalkine Signaling Regulates Macrophage Recruitment into the Cochlea and Promotes the Survival of Spiral Ganglion Neurons after Selective Hair Cell Lesion. J Neurosci. 2015;35:15050–61. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2325-15.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kloss CU, Werner A, Klein MA, Shen J, Menuz K, Probst JC, Kreutzberg GW, Raivich G. Integrin family of cell adhesion molecules in the injured brain: regulation and cellular localization in the normal and regenerating mouse facial motor nucleus. J Comp Neurol. 1999;411:162–78. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(19990816)411:1<162::aid-cne12>3.0.co;2-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreutzberg GW. Microglia: a sensor for pathological events in the CNS. Trends Neurosci. 1996;19:312–8. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(96)10049-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ladrech S, Wang J, Simonneau L, Puel JL, Lenoir M. Macrophage contribution to the response of the rat organ of Corti to amikacin. J Neurosci Res. 2007;85:1970–9. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang H, Ebihara Y, Schmiedt RA, Minamiguchi H, Zhou D, Smythe N, Liu L, Ogawa M, Schulte BA. Contribution of bone marrow hematopoietic stem cells to adult mouse inner ear: Mesenchymal cells and fibrocytes. The Journal of Comparative Neurology. 2006;496:187–201. doi: 10.1002/cne.20929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li HS, Borg E. Age-related loss of auditory sensitivity in two mouse genotypes. Acta oto-laryngologica. 1991;111:827–34. doi: 10.3109/00016489109138418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikaelian DO, Warfield D, Norris O. Genetic progressive hearing loss in the C57-b16 mouse. Relation of behavioral responses to chochlear anatomy. Acta oto-laryngologica. 1974;77:327–34. doi: 10.3109/00016487409124632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyao M, Firestein GS, Keithley EM. Acoustic Trauma Augments the Cochlear Immune Response to Antigen. The Laryngoscope. 2008;118:1801–1808. doi: 10.1097/MLG.0b013e31817e2c27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris L, Graham CF, Gordon S. Macrophages in haemopoietic and other tissues of the developing mouse detected by the monoclonal antibody F4/80. Development. 1991;112:517–26. doi: 10.1242/dev.112.2.517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okano T, Nakagawa T, Kita T, Kada S, Yoshimoto M, Nakahata T, Ito J. Bone marrow-derived cells expressing Iba1 are constitutively present as resident tissue macrophages in the mouse cochlea. Journal of Neuroscience Research. 2008;86:1758–1767. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ou HC, Bohne BA, Harding GW. Noise damage in the C57BL/CBA mouse cochlea. Hearing Research. 2000;145:111–122. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(00)00081-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters A, Swan RC. The choroid plexus of the mature and aging rat: the choroidal epithelium. Anat Rec. 1979;194:325–53. doi: 10.1002/ar.1091940303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raivich G, Bohatschek M, Kloss CU, Werner A, Jones LL, Kreutzberg GW. Neuroglial activation repertoire in the injured brain: graded response, molecular mechanisms and cues to physiological function. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 1999;30:77–105. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(99)00007-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato E, Shick HE, Ransohoff RM, Hirose K. Repopulation of cochlear macrophages in murine hematopoietic progenitor cell chimeras: The role of CX3CR1. The Journal of Comparative Neurology. 2008;506:930–942. doi: 10.1002/cne.21583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato E, Shick HE, Ransohoff RM, Hirose K. Expression of fractalkine receptor CX3CR1 on cochlear macrophages influences survival of hair cells following ototoxic injury. J Assoc Res Otolaryngol. 2010;11:223–34. doi: 10.1007/s10162-009-0198-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sautter N, Shick E, Ransohoff R, Charo I, Hirose K. CC Chemokine Receptor 2 is Protective Against Noise-Induced Hair Cell Death: Studies in CX3CR1+/GFP Mice. JARO. 2006;7:361–372. doi: 10.1007/s10162-006-0051-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi X. Resident macrophages in the cochlear blood-labyrinth barrier and their renewal via migration of bone-marrow-derived cells. Cell Tissue Res. 2010;342:21–30. doi: 10.1007/s00441-010-1040-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shnerson A, Pujol R. Age-related changes in the C57BL/6J mouse cochlea. I. Physiological findings. Brain Res. 1981;254:65–75. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(81)90059-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spongr VP, Flood DG, Frisina RD, Salvi RJ. Quantitative measures of hair cell loss in CBA and C57BL/6 mice throughout their life spans. J Acoust Soc Am. 1997;101:3546–53. doi: 10.1121/1.418315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stence N, Waite M, Dailey ME. Dynamics of microglial activation: a confocal time-lapse analysis in hippocampal slices. Glia. 2001;33:256–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tornabene SV, Sato K, Pham L, Billings P, Keithley EM. Immune cell recruitment following acoustic trauma. Hearing Research. 2006;222:115–124. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2006.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaughan DW, Peters A. Neuroglial cells in the cerebral cortex of rats from young adulthood to old age: an electron microscope study. J Neurocytol. 1974;3:405–29. doi: 10.1007/BF01098730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vethanayagam RR, Yang W, Dong Y, Hu BH. Toll-like receptor 4 modulates the cochlear immune response to acoustic injury. Cell Death Dis. 2016;7:e2245. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2016.156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakabayashi K, Fujioka M, Kanzaki S, Okano HJ, Shibata S, Yamashita D, Masuda M, Mihara M, Ohsugi Y, Ogawa K, Okano H. Blockade of interleukin-6 signaling suppressed cochlear inflammatory response and improved hearing impairment in noise-damaged mice cochlea. Neuroscience Research. 2010;66:345–352. doi: 10.1016/j.neures.2009.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White JA, Burgess BJ, Hall RD, Nadol JB. Pattern of degeneration of the spiral ganglion cell and its processes in the C57BL/6J mouse. Hear Res. 2000;141:12–8. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(99)00204-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willott JF. Effects of aging, hearing loss, and anatomical location on thresholds of inferior colliculus neurons in C57BL/6 and CBA mice. J Neurophysiol. 1986;56:391–408. doi: 10.1152/jn.1986.56.2.391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang W, Vethanayagam RR, Dong Y, Cai Q, Hu BH. Activation of the antigen presentation function of mononuclear phagocyte populations associated with the basilar membrane of the cochlea after acoustic overstimulation. Neuroscience. 2015;303:1–15. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2015.05.081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young RW, Bok D. Participation of the retinal pigment epithelium in the rod outer segment renewal process. J Cell Biol. 1969;42:392–403. doi: 10.1083/jcb.42.2.392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]