Abstract

Extinction of fear to a Pavlovian conditioned stimulus (CS) is known to be context-specific. When the CS is tested outside the context of extinction, fear returns, or renews. Several studies have demonstrated that renewal depends upon the hippocampus, although there are also studies where renewal was not impacted by hippocampal damage, suggesting that under some conditions context encoding and/or retrieval of extinction depends upon other regions. One candidate region is the retrosplenial cortex (RSC), which is known to contribute to contextual and spatial learning and memory. Using a conditioned-suppression paradigm, Experiment 1 tested the impact of pre-training RSC lesions on renewal of extinguished fear. Consistent with previous studies, lesions of the RSC did not impact acquisition or extinction of conditioned fear to the CS. Further, there was no evidence that RSC lesions impaired renewal, indicating that contextual encoding and/or retrieval of extinction does not depend upon the RSC. In Experiment 2, post-extinction lesions of either the RSC or dorsal hippocampus (DH) also had no impact on renewal. However, in Experiment 3, both RSC and DH lesions did impair performance in an object-in-place procedure, an index of place memory. RSC and DH contributions to extinction and renewal are discussed.

Keywords: fear extinction, renewal, conditioned suppression, retrosplenial, hippocampus

Extinction is a fundamental process of behavior change that allows organisms to adapt to ever-changing contingencies in the environment (e.g., Bouton & Todd, 2014). In Pavlovian extinction, conditioned responding declines as the conditioned stimulus (CS) is repeatedly presented in the absence of the unconditioned stimulus (US). Importantly, Pavlovian extinction in the laboratory is often viewed as the preclinical counterpart of exposure-based therapy (Vervliet, Craske, Hermans, 2013).

Although conditioned responding decreases during extinction, it is now well accepted that extinction does not erase the original learning (Bouton, 2002, 2004; Rescorla, 2001; Vurbic & Bouton, 2014; cf. Delamater & Westbrook, 2014). Instead, extinction results in new learning that is especially context-dependent. In conditioning experiments, contexts are often operationally defined as the background stimuli that are provided by the experimental apparatus. They typically differ in their olfactory, tactile and visual characteristics (Bouton, 2010). Extinction is thought to be context dependent because under a variety of circumstances extinguished responding will recover when the context changes (see Bouton, 2002, 2004). For instance, in renewal, extinguished responding returns when the CS is presented in a context different from the one in which it was extinguished (e.g., Bouton & Bolles, 1979). When conditioning occurs in one context (A) and extinction in another (B), responding returns when the CS is then presented in Context A (i.e., ABA renewal, Bouton & King, 1983). Renewal also occurs when testing takes place in a neutral third context (i.e., ABC renewal, Bouton & Bolles, 1979) or when conditioning and extinction both occur in Context A, and the CS is then tested in Context B (i.e., AAB renewal, Bouton & Ricker, 1994). The ABC and AAB forms of renewal are especially important in that they demonstrate that removal from the context of extinction is sufficient for renewal to occur. Since a return to the original conditioning context is not required, extinction must result in inhibitory learning that is specific to the extinction context (e.g., Bouton, 1993).

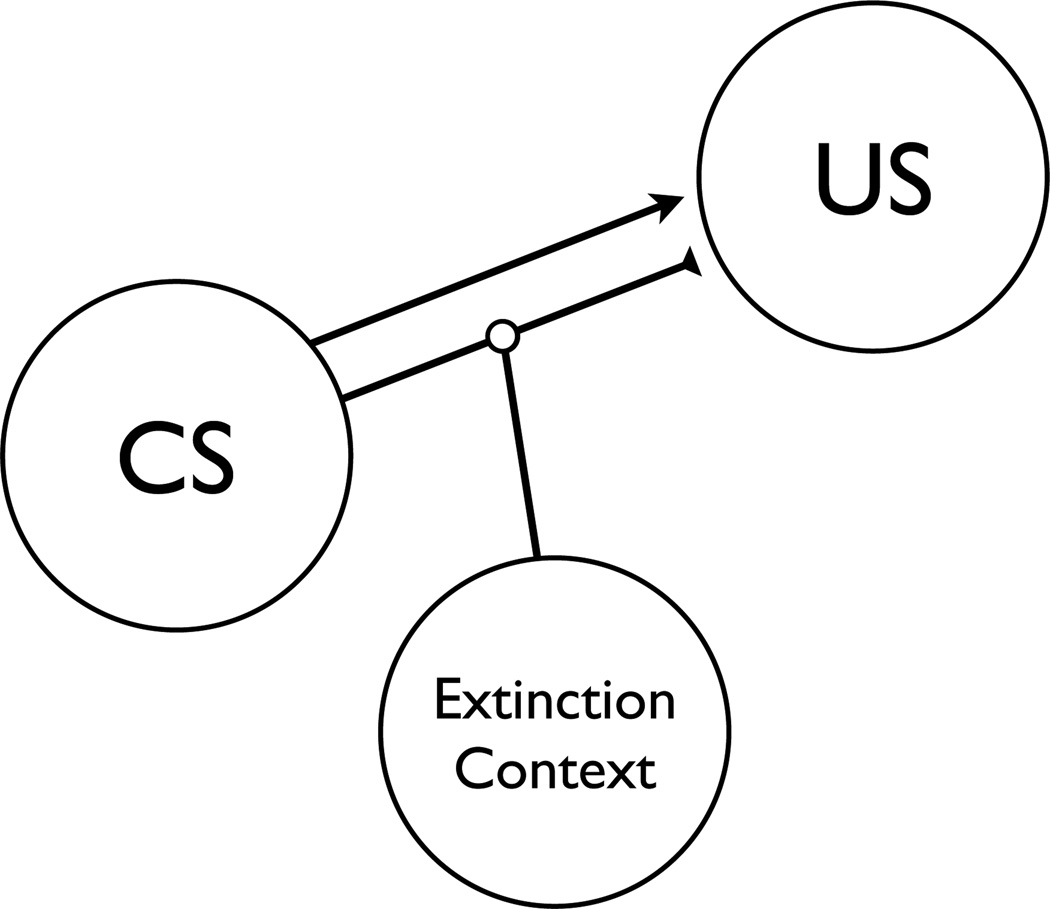

Behaviorally, it is reasonably well accepted that the extinction context acts as a negative occasion setter and modulates an inhibitory association between the CS and US (Bouton, 1993, 1994, 1997, 2004; Bouton & Nelson, 1994, 1998; Bouton & Todd, 2014; Todd, Vurbic, & Bouton, 2014). As shown in Figure 1, inhibition between the CS and US requires input from both the extinction context and the CS. When the CS is tested outside the context of extinction, inhibition is not present and responding recovers. The behavioral understanding of extinction has informed an understanding of the neurobiological mechanisms of extinction and renewal (for reviews see Maren, 2001, 2011; Maren, Phan, Liberzon, 2013; Maren & Quirk, 2004). The overall circuit includes the amygdala and the medial prefrontal cortex, with the hippocampus playing a central role in contextual encoding and retrieval of extinction (e.g., Maren, 2011). A role for the hippocampus is supported by the finding that lesions of the dorsal hippocampus eliminate ABA renewal of freezing behavior (Ji & Maren, 2005), and temporary inactivation of the dorsal hippocampus at the time of test eliminates AAB and ABC renewal of freezing (Corcoran, Desmond, Frey, & Maren, 2005; Corcoran & Maren, 2001, 2004). However, although data such as these support the notion that the hippocampus has a crucial role in the contextual modulation of extinction, there are several studies that have failed to find hippocampal contributions to renewal (e.g., appetitive conditioning, Campese & Delamater, 2013; conditioned suppression, Frohardt, Guarraci & Bouton, 2000; conditioned suppression, Wilson, Brooks, & Bouton, 1995; see also Zelikowsky, Pham, & Fanselow, 2012). This suggests that, at least under certain conditions, alternative regions/pathways are responsible for the contextual encoding and/or retrieval of extinction.

Figure 1.

Hypothetical model of Pavlovian extinction (e.g., Bouton & Todd, 2014). “CS” = conditioned stimulus, “US” = unconditioned stimulus. Arrow indicates an excitatory association between the CS and US, while the blocked line indicates an inhibitory association. The inhibitory association requires input from both the CS and the Extinction Context.

The purpose of the present experiments was to examine the role of the retrosplenial cortex (RSC) in extinction and renewal using a conditioned suppression paradigm. Importantly, using nearly identical methods, Bouton and colleagues reported no effect of either pre-training hippocampal or fornix lesions on ABA renewal (Frohardt et al. 2000; Wilson et al., 1995). Thus, under these parameters, some other region or pathway must be responsible for contextual encoding and/or retrieval of extinction. The RSC is a suitable candidate given it is anatomically well positioned to process contextual information (Sugar, Witter, van Strien, & Cappaert, 2011; Wyss & van Groen, 1992). For example, the RSC has reciprocal connections with visual-spatial processing areas, as well as several regions in the parahippocampal – hippocampal memory network, and is considered part of the “where” processing stream (e.g., Bucci & Robinson, 2014; Ranganath & Ritchey, 2012). Indeed, the RSC is critically involved in contextual and spatial learning and memory (for reviews see Bucci & Robinson, 2014; Miller, Vedder, Law, & Smith, 2014; Todd & Bucci, 2015; Ranganth & Ritchey, 2012; Vann, Aggleton, & Maguire, 2009), which is consistent with its potential involvement in the contextual encoding/retrieval of extinction.

Experiment 1

The experimental design for Experiment 1 is presented in Table 1. All rats received Sham or electrolytic lesions of the RSC prior to training. Then, using a conditioned suppression paradigm, all rats received pairings of a visual CS with footshock in Context A, while receiving equal exposure to Context B. Extinction then occurred in Context B with equal exposures to Context A. There were no footshocks delivered during the extinction phase. Finally, over the course of two-days, all rats received test presentations of the CS in both the extinction (B) and renewal (A) contexts in a counterbalanced order. During the test, no footshocks were delivered. In addition to providing the first test of RSC involvement in ABA renewal, Experiment 1 is also one of the first to examine the effect of RSC lesions on conditioning and extinction in a conditioned suppression paradigm (cf. Todd, Huszár, DeAngeli, & Bucci, 2016).

Table 1.

Design of Experiments 1 and 2.

| Pre-exposure | Conditioning | Extinction | Renewal Test |

|---|---|---|---|

| AL−, B− | AL+, B− | BL−, A− | AL− and BL− or BL− and AL− |

Note. “A” = Context A and “B” = Context B. “L” = flashing light CS. “+” = footshock (.5 mA, .5 s), and “−” = nonreinforcement. Renewal testing was within subject with test order counterbalanced. Half of each group was tested in A and then B, and half were tested in B and then A.

Method

Subjects

The subjects were 16 adult male Long Evans rats, obtained from Harlan Laboratories (Indianapolis, IN), and were about ~60 days old upon arrival. Rats were housed individually and allowed at least 6 days to acclimate to the vivarium prior to surgery. Food was available ad libitum (Purina standard rat chow; Nestle Purina, St. Louis, MO). Throughout the study, rats were maintained on a 14:10 light-dark cycle and monitored and cared for in compliance with association for Assessment and Accreditation of laboratory Animal Care guidelines and the Dartmouth College Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. All rats had previously been in an aversive conditioning experiment, and a Pavlovian conditioning experiment with visual and auditory stimuli and an appetitive reinforcer. However, they were naïve to the current configuration of the context (i.e., the combination of visual, tactile, and olfactory cues), lever pressing, and the visual stimulus used in the current experiment. The behavioral procedures for Experiment 1 began approximately 2 months following surgery.

Surgery

All surgeries took place over a 4-day period that immediately followed the acclimation period. Subjects were anesthetized with isoflurane gas (1.5% - 3% in oxygen) and placed in a Kopf stereotaxis apparatus. The skin was retracted and holes were drilled through the skull above each of the intended lesion sites (see Table 2) using the rat brain atlas of Paxinos and Watson (2009). Eight rats received bilateral electrolytic lesions (2 mA, 15 s at each site) of the RSC prior to behavioral training. Control rats received sham lesions consisting of a craniotomy and shallow, non-puncturing burr holes to minimize damage to the underlying cortex. Rats were allowed to recover for at least 2 weeks prior to behavioral training in a separate experiment. Rats were food restricted and maintained at 85% body weight throughout the current experiment.

Table 2.

Stereotaxic coordinates for restrosplenial cortex and dorsal hippocampus lesions.

| Lesion | AP | ML | DV |

|---|---|---|---|

| RSC | −2.0 | ± 0.3 | −2.0 and −2.7 |

| −3.5 | ± 0.4 | −2.0 and −2.7 | |

| −5.0 | ± 0.4 and ± 1.0 | −2.0 and −2.7 (medial site) and −2.0 (lateral site) | |

| −6.5 | ± 0.8 and ± 1.5 | −2.0 and −2.8 (medial site) and −3.4 (lateral site) | |

| −8.0 | ± 1.6 and ± 2.4 | −2.5 (medial site) and −3.1 (lateral site) | |

| −9.0 | ± 3.4 | −4.0 | |

| DH | −2.8 | ± 1.6 and ± 2.6 | −3.7 |

| −4.2 | ±3.6 and ± 4.2 | −3.7 (medial site) and −4.0 (lateral site) |

Note. All anterior-posterior (AP), medial-lateral (ML) and dorsal-ventral (DV) measurements are derived from bregma, midline, and skull surface, respectively (measurements are in mm). RSC = restrosplenial cortex, DH = dorsal hippocampus.

Behavioral apparatus

Two sets of four conditioning chambers served as the two contexts (counterbalanced). All chambers were of the same standard design (Med Associates, Inc., St. Albans, VT, ENV-007; 24 cm W × 30.5 cm L × 29 cm H) and each was housed in its own sound attenuation chamber (Med Associates, ENV-017M; 66 cm W × 56 cm H × 56 cm D) and outfitted with an exhaust fan to provide airflow and background noise (~68 dB). Each chamber was outfitted with a food cup, recessed in the center of the front wall, and a retractable lever (Med Associates, ENV-112CM) positioned to the right of the food cup. Each chamber had a panel light (Med Associates, ENV-221M) mounted approximately 16 cm above the grid floor centered over the food cup, and a house light (Med Associates, ENV-215M) mounted approximately 24 cm above the grid floor on the back wall of the chamber. A speaker (Med Associates, ENV-224AM) was located 20 cm above and to the right of the food cup and was used to present the auditory stimuli. Both sets of chambers were illuminated with a 2.8-W bulb (with a red cover), mounted to the ceiling of the sound attenuating chamber.

In one set of chambers, the sidewalls and ceiling were made of clear acrylic plastic and the front and rear walls were made of brushed aluminum. The grid floor was stainless steel rods (5-mm diameter) spaced 1.5 cm apart (center-to-center). In the second set of chambers the grids of the floor were staggered such that odd- and even-numbered grids were mounted in two separate planes, one 0.5 cm above the other. The staggered grid floor provided a distinct tactile feature. The ceiling, back wall, and door were covered with laminated black and white checkerboard paper (1-cm squares) to provide distinct visual cues.

Because these two sets of chambers were located within the same room of the laboratory, in order to prevent diffusion of the olfactory cues we used one olfactory cue for Context A sessions, and a second olfactory cue for Context B sessions. During Context A sessions, 3 mL of Pine-Sol (Clorox, Co., Oakland, CA) and for Context B sessions 3 mL of 10% lemon solution was used (McCormick & Co Inc., Hunt Valley, MD).

The houselight mounted to the back wall served as the visual stimulus. During CS presentation, it flashed twice per second for 30 s. Footshocks (.5 mA, .5 s) were generated by a Med Associates shock generator (ENV-414) connected to each chamber. The reinforcer was a 45-mg grain based rodent food pellet (BioServ, Flemington, NJ). The apparatus was controlled by computer equipment located in an adjacent room. Surveillance cameras located inside the sound-attenuating chambers were used to monitor the rats’ behavior.

Behavioral procedures

Baseline lever-press training

On the first day of the experiment, each rat was assigned to one chamber (Context A) and received a single session of magazine training. During this session, food pellets were delivered freely on random-time 60-s (RT 60-s) schedule, resulting in 60 pellets being delivered on average. In addition, all lever presses were reinforced with a single pellet. On the next day, all rats received an identical session of training in the alternative context (Context B). On the following two days, rats received a 1-h session in which lever responding was reinforced on a random-interval (RI) 15-s schedule, one in Context A and one in Context B. The schedule increased to RI 30 s for the following two days (one session in A and one in B), and for the next 8 subsequent days (alternating between Context A and B) the schedule was increased to RI 60 s. The RI 60 s schedule was in place for the remainder of the experiment.

Pre-exposure

Following baseline lever press training, there was an additional session in Context A, where “baseline” suppression was recorded even though the flashing light CS was never presented. Lever pressing was recorded during 30-s periods for 4 “baseline” trials. The intertrial interval (ITI) for the “baseline” trials was variable, with an average ITI of 13.75 minutes (± 25%). On the next day, all rats received a single session of lever press training in Context B. The third day was the pre-exposure session in Context A. During this session the light was presented 4 times (at the exact times as the previously scheduled “baseline” trials), and as usual responding throughout the session was reinforced on a RI 60 s schedule. On the final day of this phase all rats received a lever press training session in Context B.

Conditioning

Conditioning occurred over the course of three daily sessions. On Day 1, all rats received 4 pairings of the light with footshock (.5 mA, .5 s) in Context A. The ITI was variable, with an average ITI of 13.75 minutes (± 25%). On Day 2, all rats received a baseline lever press training session in Context B. On Day 3, rats received an additional 4 light-shock pairings in Context A.

Extinction

Extinction training started the subsequent day. Extinction occurred over the course of 4, two-day cycles. On the first day of each cycle, all rats received 8 nonreinforced presentations of the light in Context B (no shocks were presented). The ITI was variable, with an average ITI of 6.8 minutes (± 25%). On the second day of each cycle, all rats received a baseline lever training session in Context A.

Renewal

Renewal testing occurred over the course of the next two subsequent days. All rats received 4 nonreinforced presentations of the light CS in both Contexts A and B, with test order counterbalanced. Half of the rats in each group were first tested in A and half in B. The other half of the rats received the opposite test order. During the test, the ITI was variable, with an average ITI of 13.75 minutes (± 25%).

Behavioral observations and data analysis

Throughout the experiment, suppression to the light stimulus was indexed in terms of standard suppression ratios of the form x/(x+y), where x represents the number of lever presses made during the 30 s stimulus, and y represents the number of lever presses made during the 30 s period just prior to the onset of the stimulus (pre-CS). Thus, a score of .5 indicates no suppression, whereas a score of 0 indicates complete suppression. Trials were excluded in cases where rats failed to make at least 1 press during the pre-CS period (e.g., Nelson, Sanjuan, Vadillo-Ruiz, Pérez, & León, 2011). Over the course of the entire experiment (pre-exposure, conditioning, extinction, renewal), this resulted in a total of 5 trials removed for Sham and 6 for RSC lesioned rats. Suppression ratios and pre-CS scores were analyzed with analysis of variance (ANOVA) using a rejection region of p < .05.

Lesion verification and analysis

After the behavioral procedures were completed (i.e., after Experiment 3) rats were deeply anesthetized with an overdose of sodium pentobarbital and transcardially perfused with 0.9% saline for 2 min, followed by 10% buffered formalin for 6 min. Coronal brain sections (60 µm) were collected using a freezing microtome and were Nissl-stained using thionin. Using a compound microscope (Axioskop I, Zeiss, Inc.), we identified gross tissue damage as necrosis, missing tissue, or marked thinning of the cortex. Outlines of the lesions were drawn onto digital images adapted from Paxinos and Watson (2009) using PowerPoint at 6 levels along the rostro-caudal extent of the RSC (−1.8, −3.0, −4.2, −5.4, −6.6, and −7.8 mm from bregma). At each level, area measurements where then made with ImageJ, including the total area of the target region and the area of the target region that exhibited gross tissue damage. From these measurements, we report the average percentage of RSC that was damaged. In addition, we report the average percentage of sections across the rostro-caudal plane that exhibited RSC damage (out of ~24 sections collected for each rat), the average percentage of sections with damage outside the RSC, and the number of rats with damage to regions outside the RSC.

Results

Histology

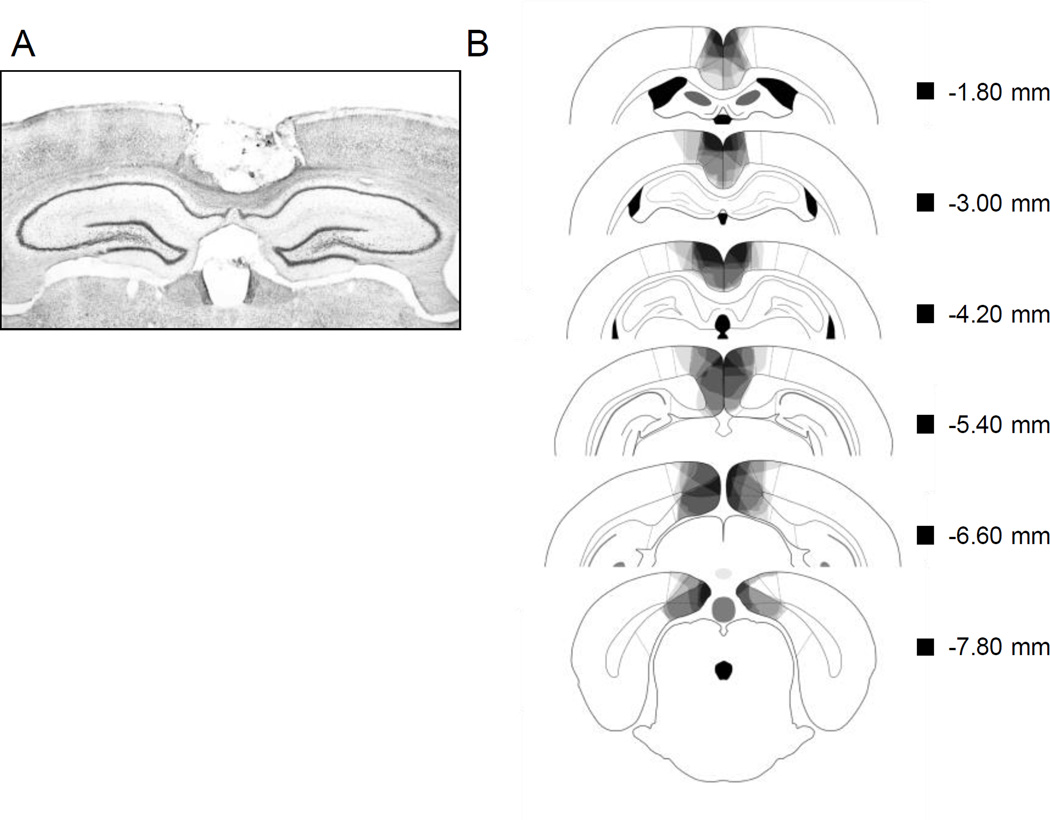

Figure 2a shows a photomicrograph of a representative RSC lesion. In Figure 2b, lesion drawings are stacked onto a single atlas image for each of the 6 coronal levels. Bilateral RSC damage was observed in all rats, and the average area of RSC damaged on each section analyzed was 58.8% (SEM = 7.18). There was minor damage outside the RSC in all rats (e.g., anterior cingulate, visual cortex, motor cortex, cingulum bundle, forceps major corpus callosum). Damage to the RSC was present on 99.1% (SEM = 0.62) of the sections collected for each subject, indicating that damage extended throughout the rostro-caudal extent of the RSC. In contrast to RSC damage, the minor damage outside RSC was present on only 43.9% (SEM = 10.1) of sections collected.

Figure 2.

A: Photomicrograph of a representative RSC lesion. B: Drawings of lesions at six levels along the rostro-caudal extent of the RSC (−1.8, −3.0, −4.2, −5.4, −6.6, and −7.8 mm posterior to bregma). At each level, lesion drawings were stacked onto a single image. The darkness of an area indicates the number of lesions cases that include that area. Grey boxes (next to the bregma values) represent the expected darkness for overlap from all subjects. Adapted from The Rat Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates (Compact 6th ed.), by G Paxinos and C. Watson, 2009.

Behavior

Baseline

The acquisition of lever pressing proceeded similarly for both groups. A 2 (Group) × 2 (Context) × 7 (Session) ANOVA revealed a main effect of session, F(6, 84) = 15.48, p < .01, and an interaction between context and session, F(6, 84) = 3.82, p < .01. The main effect of context approached significance, F(1, 14) = 4.10, p = .06. No other main effects or interactions were significant, largest F(1, 14) = 1.55, p = .23. The groups did not reliably differ during the final lever press training session in Contexts A and B, Fs < 1. The mean responses per 30 s period averaged 8.4 (Sham) and 8.7 (RSC), and 7.9 (Sham) and 7.9 (RSC) for the final session in A and B, respectively.

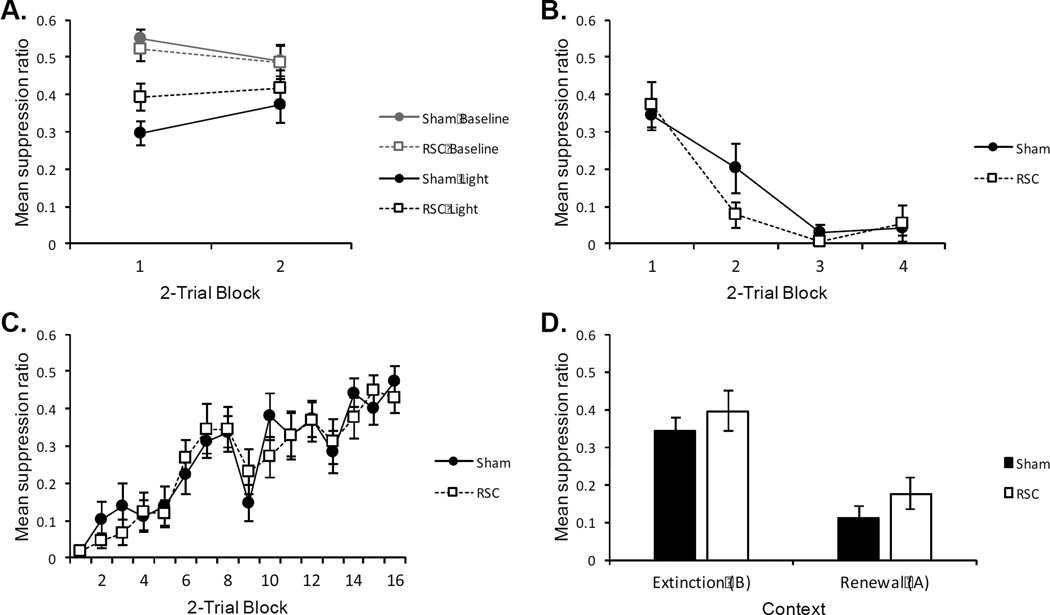

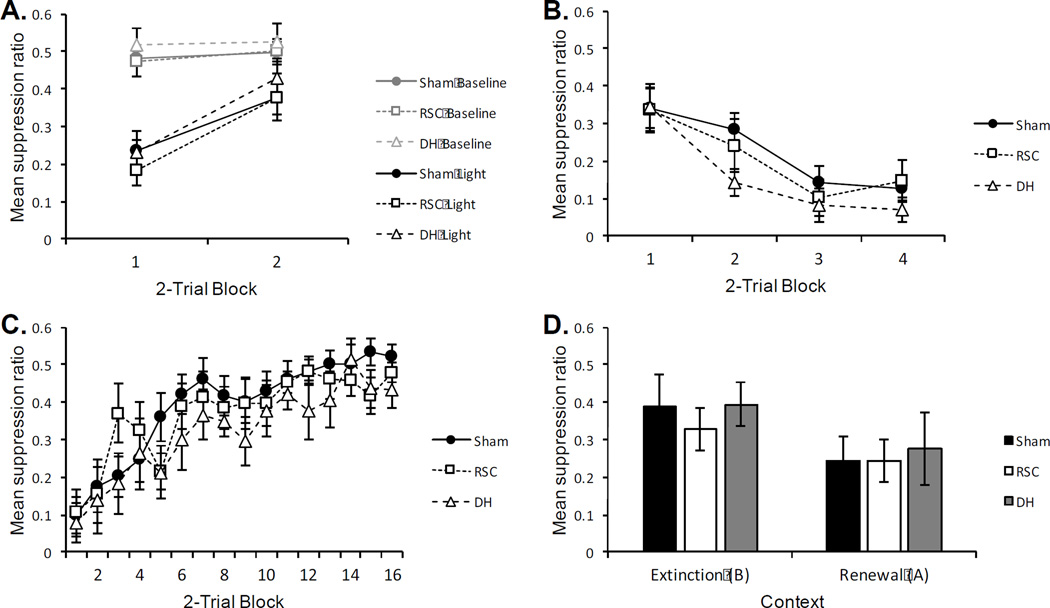

Pre-exposure

Mean responding during the pre-exposure phase of the Experiment is presented in the top left panel of Figure 3 (Panel A). There was unconditioned suppression to the flashing light relative to the previous baseline training session (Baseline). A 2 (Group) × 2 (Trial Block) × 2 (Session: “Baseline” vs. “Light”) ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of session, F(1, 14) = 33.33, p < .01, indicating greater suppression during the pre-exposure session (“Light”) relative to the baseline session (“Baseline”). The interaction between trial block and session approached significance, F(1, 14) = 3.385, p = .07. As is evident in top left panel of Figure 3 (Panel A), there appeared to be more unconditioned suppression during the first trial block, relative to the second trial block. No other main effects or interactions were significant, largest F(1, 14) = 2.89, p = .11. An identical analysis of pre-CS responding did not reveal any significant main effects or interactions, largest F(1, 14) = 2.64, p = .13. The average pre-CS responses were 10.00 and 9.06 for Sham and RSC lesioned rats, respectively.

Figure 3.

A (Pre-exposure): Unconditioned suppression to non-reinforced presentations of the flashing houselight in Context A. “Baseline” = suppression ratio calculated during a baseline session in which the light stimulus was not presented. “Light” = suppression ratio calculated from the pre-exposure session in which the light stimulus was presented 4 times. B (Conditioning): Mean suppression during the conditioning phase of Experiment 1. All rats received 8 reinforced presentations of the light CS. C (Extinction): Mean suppression during the extinction phase of Experiment 1. All rats received 32 nonreinforced presentations of the light CS (8 per session) D (Renewal): Mean suppression to the light CS during renewal testing in Experiment 1. All rats received 4 nonreinforced test trials of the light CS in both the extinction context (B) and the renewal context (A; test order counterbalanced). In all panels: Sham = sham lesioned rats, RSC = retrosplenial lesioned rats. Error bars represent ±1 SEM.

Conditioning

The acquisition of conditioned suppression is presented in the top right panel of Figure 3 (Panel B). Suppression increased over the course of conditioning, and was near complete during the final trial block. The rate of conditioning did not differ between Sham and RSC lesioned rats. A 2 (Group) × 4 (Trial Block) ANOVA revealed a main effect of trial block, F(3, 42) = 32.28, p < .01. Neither the main effect of group, nor the group by trial interaction approached significance, largest F(3, 42) = 1.58, p = .21.

Similarly, analysis of pre-CS responding yielded a main effect of trial, F(3, 42) = 4.57, p < .01, and neither the main effect of group nor the group by trial interaction were significant Fs < 1. During the first trial block, average pre-CS responses were 12.63 and 13.56 for Sham and RSC rats, respectively. Responding decreased by the final trial block, likely the results of general suppression due to the presentation of shock. During the final trial block of acquisition, the average pre-CS responses were 4.94 (Sham) and 6.94 (RSC).

Extinction

The results of the extinction phase are presented in the bottom left of Figure 3 (Panel C). As extinction progressed, conditioned suppression weakened for both groups at a similar rate. A 2 (Group) × 16 (Trial Block) ANOVA revealed a main effect of trial, F(15, 210) = 25.61, p < .001. Neither the main effect of group nor the interaction between group and trial interaction were significant, Fs < 1. An identical analysis on pre-CS responding did not reveal any significant main effects or interactions, Fs < 1. Over the course of extinction, the average pre-CS responses were 9.73 and 10.57 for Sham and RSC rats, respectively.

Renewal

The results of the within-subject renewal test, averaged over all 4 test trials, are presented in the bottom right panel of Figure 3 (Panel D). Renewal was observed for both groups; there was more suppression in the renewal context (A) relative to the extinction context (B) A 2 (Group) × 2 (Context) ANOVA revealed a main effect of context, F(1, 14) = 50.17, p < .001. Neither the main effect of group nor the interaction between group and context were significant, largest F(1, 14) = 1.48, p = .24. Thus, renewal was evident and equally strong in both Sham and RSC lesioned rats. Analysis of pre-CS responding did not reveal any significant main effects or interactions, Fs < 1. The average pre-CS responses were 12.39 (Sham) and 9.97 (RSC).

Discussion

The main finding from Experiment 1 was that lesions of the RSC had no impact on ABA renewal in a conditioned suppression paradigm. Further, the fact that RSC lesions had no impact on either acquisition or extinction, extends the generality of previous findings that have demonstrated no impact of RSC lesions on the acquisition or extinction of Pavlovian delay fear conditioning as assessed with freezing (Keene & Bucci, 2008a, 2008c; Kwapis et al., 2014, 2015). Similarly, a recent study also found no effect of pre-training RSC lesions on extinction of conditioned suppression (Todd et al., 2016).

Experiment 2

For Experiment 2, Sham or RSC lesions were made following extinction training. This was done to rule out potential compensation by other brain regions that may occur when lesions are made prior to training, as in Experiment 1 (see Fanselow, 2010). Post-extinction lesions therefore have the potential to reveal if the RSC is normally involved in extinction learning. In addition, a third group of rats received post-extinction lesions of the dorsal hippocampus (DH), allowing for a direct comparison between the effects of RSC and DH lesions. The addition of the post-extinction DH lesions group also extended previous work by Bouton and colleagues in which lesions of either the fornix or hippocampus were made prior to training (Frohardt et al., 2000; Wilson et al., 1995).

Method

Subjects

The subjects were 24 experimentally naïve adult male Long Evans rats, purchased from the same vendor as those in the previous experiment and maintained under the same conditions. Prior to the start of behavioral training rats were food restricted to 85% of their baseline weight.

Surgery

The procedure for Sham and RSC lesions was the same as Experiment 1, and the same general procedure was used for lesions of the DH. Eight rats received bilateral electrolytic lesions (2.5 mA, 25 s at each site) of the DH at 8 sites (see Table 2).

Behavioral apparatus and procedures

The apparatus and procedures were the same as those used in Experiment 1, with the following exception. All lesions occurred during a 2-day period following the extinction phase of Experiment 2. After 14 days of recovery, all rats received a single baseline recovery session in both Context A and B, in which lever pressing was reinforced on an RI 60 s schedule and no stimuli were presented. Renewal testing began the following day.

Behavioral observations and data analysis

Behavioral observation and data analysis were the same as Experiment 1. As in Experiment 1, trials were excluded in cases where rats failed to make at least 1 press during the pre-CS period. Over the course of the entire experiment (pre-exposure, conditioning, extinction, renewal), this resulted in a total of 5 trials removed for Sham, 8 for RSC lesioned rats, and 0 for DH lesioned rats.

Lesion verification and analysis

RSC lesions were verified and analyzed using the same procedures as Experiment 1. For DH lesions, coronal brain sections (60 µm) were collected using a freezing microtome and were Nissl-stained using thionin for visualization of the lesion. Lesions were verified by visual inspection of lesion outlines drawn onto images adapted from Paxinos and Watson (2009).

Results

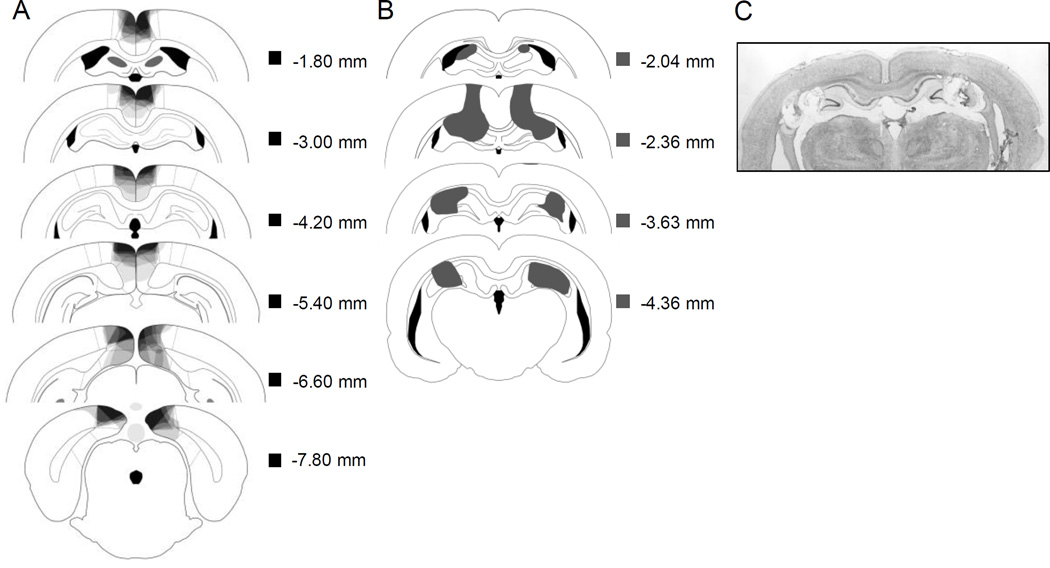

Histology

In Figure 4a, RSC lesion drawings are stacked onto a single atlas image for each of the 6 coronal levels. Bilateral RSC damage was observed in all rats, and the average area of RSC damaged on each section analyzed was 42.4% (SEM = 3.16). There was minor damage outside the RSC in all rats (e.g., anterior cingulate, visual cortex, motor cortex, cingulum bundle, forceps major corpus callosum). Damage to the RSC was present on 98.8% (SEM = 1.19) of the sections collected for each subject, indicating that damage extended throughout the rostro-caudal extent of the RSC. In contrast to RSC damage, the minor damage outside RSC was present on only 47.48% (SEM = 8.74) of sections collected.

Figure 4.

A: Drawings of lesions at six levels along the rostro-caudal extent of the RSC (−1.8, −3.0, −4.2, −5.4, −6.6, and −7.8 mm posterior to bregma). At each level, lesion drawings were stacked onto a single image. The darkness of an area indicates the number of lesions cases that include that area. Grey boxes (next to the bregma values) represent the expected darkness for overlap from all subjects. B. Schematic representation of a representative DH lesions (grey area). C. Photomicrograph of a representative DH lesion. Adapted from The Rat Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates (Compact 6th ed.), by G Paxinos and C. Watson, 2009

A schematic representation and a photomicrograph of a representative DH lesion are presented in Figure 4b and 4c, respectively. One rat died during surgery, and a second was removed from the analysis due to insufficient damage to the DH. In the remaining six rats, the lesions consisted of bilateral damage to areas CA1, CA3, and the dentate gyrus. There was damage to cortical regions dorsal to the hippocampus in all rats, and in two rats there was minor damage to the fornix.

Behavior

Baseline

The acquisition of lever pressing proceeded similarly for all groups. A 3 (Group) × 2 (Context) × 7 (Session) ANOVA revealed a main effect of session, F(6, 12) = 37.56, p < .01. No other main effects or interactions were significant, largest F(1, 19) = 3.63, p = .07. The groups did not reliably differ during the final lever-press training session in Contexts A and B, largest F(2, 19) = 1.38, p = .28. The mean responses per 30 s period averaged 7.8 (Sham), 8.3 (RSC), 9.0 (DH) and 6.6 (Sham), 8.8 (RSC), 9.6 (DH), for the final session in A and B, respectively.

Pre-exposure

Mean responding during the pre-exposure phase of the Experiment is presented in the top left panel of Figure 5 (Panel A). There was some unconditioned suppression to the flashing light relative to the previous baseline training session (Baseline). A 3 (Group) × 2 (Trial Block) × 2 (Session: “Baseline” vs. “Light”) ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of session, F(1, 19) = 40.56, p < .01, indicating greater suppression during the pre-exposure session relative to the baseline session. The effect of trail block was significant, F(1, 19) = 27.93, p < .01, as was the interaction between trial block and session, F(1, 19) = 15.22, p < .01. As shown in Figure 5 (Panel A), unconditioned suppression was stronger during the first trial block than during the second. No other main effects or interactions were significant, Fs < 1.

Figure 5.

A (Pre-exposure): Unconditioned suppression to non-reinforced presentations of the flashing houselight in Context A. “Baseline” = suppression ratio calculated during a baseline session in which the light stimulus was not presented. “Light” = suppression ratio calculated from the pre-exposure session in which the light stimulus was presented 4 times. B (Conditioning): Mean suppression during the conditioning phase of Experiment 2. All rats received 8 reinforced presentations of the light CS. C (Extinction): Mean suppression during the extinction phase of Experiment 2. All rats received 32 nonreinforced presentations of the light CS (8 per session). D (Renewal): Mean suppression to the light CS during the first 2-trial block of renewal testing in Experiment 2. All rats received 4 nonreinforced test trials of the light CS in both the extinction context (B) and the renewal context (A; test order counterbalanced). In all panels: Sham = sham lesioned rats, RSC = retrosplenial lesioned rats, DH = dorsal hippocampus lesioned rats. All lesions occurred post-extinction training. Error bars represent ±1 SEM.

An identical analysis of pre-CS responding did not reveal any significant main effects or interactions, largest F(1, 19) = 2.52, p = .13. The average pre-CS responses during the pre-exposure phase were 8.4 (Sham), 9.9 (RSC), and 9.0 (DH).

Conditioning

The results of the conditioning phase are presented in the top right of Figure 5 (Panel B). A 3 (Group) × 4 (Trial Block) ANOVA revealed a main effect of trial block, F(3, 57) = 15.35, p < .01. Neither the main effect of group, nor the interaction between group and trial approached significance, Fs < 1. Analysis of pre-CS responding failed to reveal any significant main effects or interactions, Fs < 1. During the conditioning phase, pre-CS responding averaged 8.1 (Sham), 9.4 (RSC), and 10.4 (DH).

Extinction

The results of the extinction phase are presented in the bottom left of Figure 5 (Panel C). One rat from the RSC group lost baseline responding during the first 4 trial blocks. We therefore conducted an initial 3 (Group) × 4 (Trial Block) ANOVA on the first 4 extinction blocks, excluding this rat. This analysis revealed a main effect of trial, F(3, 54) = 13.10, p < .01. Neither the main effect of group, nor the interaction between group and trial block were significant, largest F(6, 54) = 1.31, p = .27. For the remaining twelve trial blocks (i.e., blocks 5–16), with all rats included, a 3 (Group) × 12 (Trial Block) ANOVA revealed a main effect of trial block, F(11, 209) = 5.88, p < .01. Once again, neither the main effect of group nor the interaction between group and trial block were significant, largest F(1.58), p = .23.

A 3 (Group) × 16 (Trial Block) ANOVA of pre-CS responding revealed a significant main effect of trial block, F(15, 285) = 2.33, p < .01, but no effect of group or interaction between group and trial block, Fs < 1. For the first trial block, pre-CS responding averaged 8.8 (Sham), 9.12 (RSC), and 8.8 (DH). For the final trial block, pre-CS responding averaged 11.1 (Sham), 12.2 (RSC), and 12.3 (DH).

Prior to renewal testing, all rats had one baseline recovery session in Context A and then B, where they were allowed to freely lever press on a RI-60 second schedule. A 3 (Group) × 2 (Context) ANOVA revealed a marginally significant effect of context, F(1, 19) = 4.15, p = .056, presumably due to an increase in responding from Context A (first session) to Context B (second session). Neither the main effect of group nor the interaction with context were significant, largest F(2, 19) = 2.49, p = .11. In Context A, the mean responses per 30 s period were 7.1 (Sham), 7.2 (RSC), and 7.3 (DH). In Context B, the mean responses per 30 s period were 7.8 (Sham), 8.5 (RSC), and 7.1 (DH).

Renewal

An initial analysis of all test trials revealed that renewal was mainly evident during the first two-trial block of testing. Thus, the first two-trial block of testing is presented in the bottom right panel of Figure 5 (Panel D). One Sham lesioned rat lost baseline responding during testing and was therefore excluded from analysis. On the first two-trial block, a 3 (Group) × 2 (Context) ANOVA revealed a main effect of context, F(1, 18) = 6.33, p = .02, indicating more suppression in the renewal context (A) than extinction context (B). Neither the main effect of group, nor the interaction between group and context were significant, Fs < 1. Thus, regardless of lesion condition, conditioned suppression renewed in Context A relative to Context B. A 3 (Group) × 2 (Context) ANOVA on pre-CS responding did not reveal any significant main effects or interactions, Fs < 1. During the first two-trial block, pre-CS responding averaged 8.1 (Sham), 9.8 (RSC), and 7.7 (DH).

During the second two-trial block, neither the main effect of context, nor the effect of group was significant, largest F(1, 18) = 1.98, p = .18. However, there was a significant interaction between context and group, F(2, 18) = 5.14, p = .02. DH rats showed significantly more suppression in Context A relative to Context B (p < .01). This was not significant for either Sham (p = .75) or RSC (p = .21) lesioned rats. During the second two-trial block, mean suppression ratios were .47 (Sham), .40 (RSC), and .48 (DH) in Context B, and .45 (Sham), .44 (RSC), and .38 (DH) in Context A. Thus, the renewal effect persisted into the second two-trial block for DH, but not Sham or RSC, lesioned rats. A 3 (Group) × 2 (Context) ANOVA on pre-CS responding did not reveal any significant main effects or interactions, largest F(2, 18) = 1.49, p = .25. During the second two-trial block, pre-CS responding averaged 9.2 (Sham), 8.7 (RSC), and 8.8 (DH).

Discussion

In Experiments 1 and 2, lesions of either the RSC or the DH had no impact on renewal after the extinction of conditioned suppression. However, it seems unlikely that the extent of the lesions was inadequate to produce behavioral impairments. For example, RSC damage reported here is consistent with previous studies that have demonstrated behavioral impairments following RSC lesions (e.g., Keene & Bucci, 2008a, 2008c; Robinson et al., 2012, 2014). Furtheremore, all DH rats exhibited bilateral damage to area CA1 (as well as CA3 and dentate gyrus), and previous research has demonstrated that selective damage to area CA1 is sufficient to disrupt the contextual modulation of extinction (Ji & Maren, 2008). Nevertheless, the purpose of Experiment 3 was to demonstrate that the RSC and DH lesions made in both Experiments 1 and 2 were significant to affect behavior.

Experiments 3a and 3b

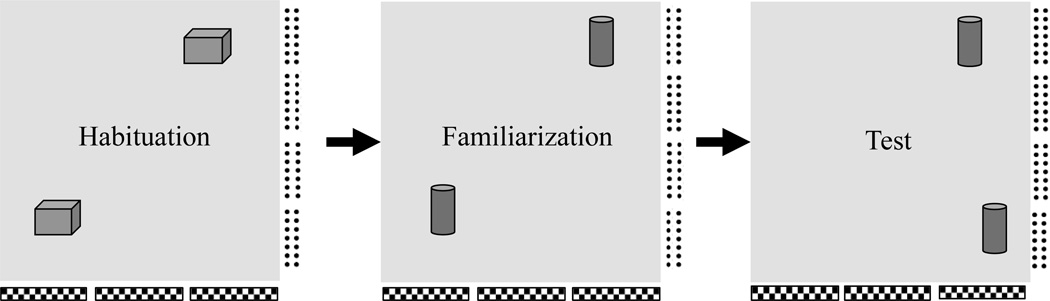

In the third experiment, rats from Experiment 1 and Experiment 2 were tested in an object-in-place procedure (Mumby, Gaskin, Gleen, Schramek, Lehmann, 2002; Vann & Aggleton, 2002). In this procedure (see Figure 6), subjects are first habituated to a set of identical objects in an open field arena. Then, subjects are familiarized to a different set of identical objects. After a short retention interval spent in the home cage, rats are then returned to the arena for a final test session in which one of the objects is now positioned in a different location of the arena. Normal rats spend more time exploring the object located in the novel place, which is thought to reflect memory for where the object was previously encountered. Based on previous findings, we expected that RSC and DH lesions would produce impairments in the object-in-place procedure (Mumby et al., 2002; Vann & Aggleton, 2002).

Figure 6.

Schematic representation of the apparatus and procedure for Experiment 3. In the “Habituation” phase, each rat was allowed to explore the environment for 3, 20 minute session. New objects were presented for the 5-minute place “Familiarization” phase. Finally, for the 3-minute place “Test”, one of the objects was presented in a novel location in the environment.

Method

Subjects

The subjects from Experiments 1 were used in Experiment 3a and the subjects from Experiment 2 were used in 3b. After the completion of Experiments 1 and 2, they were returned to ad lib food for 14 days prior to the start of Experiment 3.

Behavioral Apparatus

The apparatus consisted of an open field arena (100 cm × 100 cm × 50 cm) constructed of plywood and painted grey (see Figure 5). Sheets of laminated paper containing visual cues were affixed to two adjacent sides of the apparatus. One set of four panels consisted of 42 black circles (diameter 1.2cm, evenly spaced in rows and columns). The second set of three panels consisted of a checkered pattern (1cm black and white squares). In order to monitor behavior, a video camera was mounted to the ceiling, positioned directly above and in the center of the open field arena.

Two sets of two identical objects were used. The objects were created from colorful plastic blocks built into various shapes averaging 5.5 cm × 4 cm × 5 cm. The first set was a pair of cubes, and used only during the habituation session. The second set, cylindrical in shape, was used during the familiarization and testing phase. The objects and apparatus were cleaned thoroughly with quatricide between subjects and trials.

Behavioral Procedures

Habituation

For three consecutive days each rat was habituated to the arena for 20 min. During the habituation session two identical objects, that were similar in overall dimension to the test objects, were present in the arena. These objects were not used in the place familiarization or place test phases.

Place familiarization

On place trials, each rat was placed into the arena with two identical objects, placed 29 cm outwards from the corners or the arena (see Figure 6). Rats were allowed to explore the objects and the arena for 5 minutes, and were then removed from the area and returned to their homecage in the testing room for a 5-minute retention interval.

Place test

Following the retention interval, each rat was then returned to the arena for a 3-minute test session. Prior to the test session, one of the objects was moved to a new location, 18 cm outward from the corner of the arena. The apparatus and objects were cleaned thoroughly with quatricide between the exploration phase and the retention test.

Behavioral observations

Overall activity

During the habituation, place familiarization, and place test, the overall activity of each rat was assessed with Limelight video tracking software (Actimetrics, Wilmette, IL, USA). To do so, the arena was divided into 4 equal quadrants, and the total number of crosses into each quadrant was recorded.

Object exploration

Object exploration was scored during the place familiarization and place test. During each session, the amount of total time spent exploring each object was recorded. The rat was counted as exploring when orienting towards the object within a 4 cm radius of the object.

Results

Habituation

In Experiment 3a, the average number of quadrant crosses per habituation session was not significantly different between Sham (94.25) and RSC (94.37) lesioned rats (p = .98). However, in Experiment 3b, RSC lesioned rats made significantly more crosses than both Sham and DH lesioned rats (ps < .05). The average number of crosses per session was 132.37 (Sham), 131.77 (DH), and 183.58 (RSC).

Place familiarization

In Experiment 3a, during the 5-m place familiarization session, the average number of quadrant crosses for Sham (26.71) and RSC (19.37) lesioned rats did not differ (p > .10). Further, Sham and RSC rats spent a similar amount of time exploring the objects (p > .5) averaging 46.7 s (Sham) and 40.4 s (RSC).

In Experiment 3b, RSC (55.25) lesioned rats made more crosses during the 5-m place familiarization test than either Sham (38.12) or DH (33.33) lesioned rats (ps < .01). However, there were no differences (p > .60) in the times spent exploring the two objects, averaging 92.98 (Sham), 80.55 (RSC), and 77.60 (DH).

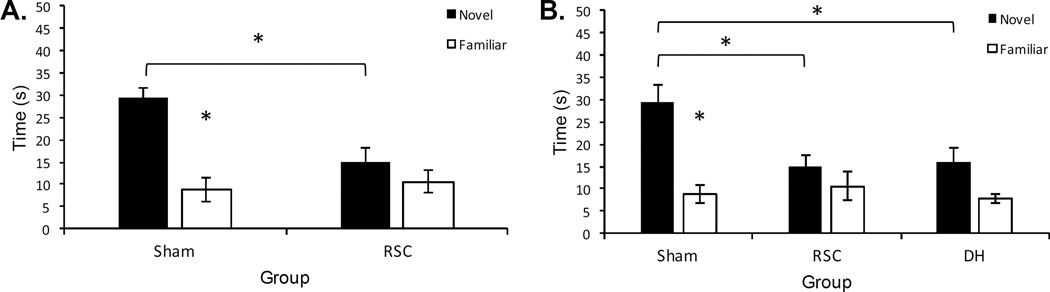

Place test

The results of the final place test, for Experiment 3a, are presented in the left portion of Figure 7 (Panel A). A 2 (Object: Novel vs. Familiar) × 2 (Group) ANOVA revealed a main effect of group, F(1, 14) = 4.75, p < .05, object, F(1, 14) = 14.21, p < .01, and an interaction between the two factors, F(1, 14) = 18.38, p < .05. The difference between the novel and familiar object was significant for Sham lesioned rats (p < .01) but not RSC lesioned rats (p = .72). Further, Sham lesioned rats spent more time exploring the novel object than RSC lesioned rats (p < .01), and the time spent exploring the familiar object did not differ between groups, (p = .70). There were no differences in overall activity, as measured by total number of quadrant crosses between groups (p = .36; RSC = 16.75, Sham = 20.14).

Figure 7.

A: Results of Experiment 3a. B: Results of Experiment 3b. Sham = sham lesioned rats, RSC = retrosplenial lesioned rats, DH = dorsal hippocampus lesioned rats. Error bars represent ±1 SEM. *p < .05.

On the basis of the present data, it seems safest to conclude that the hippocampus is important in a behavioral phenomenon that depends on context-shock associations.

The results of the place test for Experiment 3b are presented in the right panel of Figure 7 (Panel B). A 2 (Object: Novel vs. Familiar) × 3 (Group) revealed a main effect of group, F(1, 19) = 4.13, p < .05, object, F(1, 19) = 21.92, p < .01, and an interaction between the two factors, F(1, 19) = 4.73, p < .05. Although Sham lesioned rats spent more time exploring the novel object (p < .01), this effect was not significant for either the RSC (p = .27) or DH (p = .09) lesioned rats. In addition, Sham lesioned rats explored the novel object-in-place more than the RSC and DH (ps < .01) lesioned rats. There were no differences in the amount of time spent exploring the familiar object (p > .44). Finally, in contrast to Experiment 3b, RSC lesioned rats made more crosses during the final test session than either the Sham (p < .01) or DH (p < .01) lesioned rats. The Sham and DH lesioned rats did not differ (p = 43). The average number of crosses was 26.25 (RSC), 22.83 (DH), and 39.75 (RSC).

Discussion

In contrast to Experiments 1 and 2, the current experiments found a behavioral impairment resulting from lesions of the RSC or DH. Lesions of either the RSC (Experiments 3a and 3b) or the DH (Experiment 3b) impaired performance in an object-in-place procedure. Although Sham lesioned rats spent more time exploring the novel-in-place compared to familiar-in-place object, RSC and DH lesioned rats did not. More so, Sham lesioned rats spent more time exploring the novel-in-place object than either RSC or DH lesioned rats. One unexpected finding from Experiment 3b was that RSC lesioned rats were more active during the habituation, place familiarization, and test phases than either Sham and DH lesioned rats, as measured by total quadrant crosses. However, this difference in activity levels cannot fully account for the impairments caused by RSC lesions in the test phase, since there was no difference in activity levels in Experiment 3a.

General Discussion

In Experiment 1, RSC lesions had no impact on acquisition or extinction of Pavlovian fear conditioning to a visual CS. The acquisition data are consistent with previous studies that have found no effect of pre-training RSC lesions on conditioned responding to a light CS paired with a food pellet reinforcer (e.g., Keene & Bucci, 2008b; Robinson et al., 2012), as well as studies that measured freezing to a tone CS paired with shock (e.g., Keene & Bucci, 2008a, 2008c; Kwapis et al., 2015). In addition, it has recently been demonstrated that following delay fear conditioning to a tone CS, extinction is not affected by temporary inactivation of the RSC (Kwapis et al., 2014). Thus, Experiment 1 extends previous findings by demonstrating the RSC is not necessary for acquisition or extinction of Pavlovian fear conditioning in a conditioned suppression paradigm (see also Todd et al., 2016). The generality of these findings to a conditioned suppression paradigm is relevant because although freezing reliably correlates with conditioned suppression (e.g., Bouton & Bolles, 1980), there is also evidence that certain lesions can have a differential impact on freezing and conditioned suppression (e.g., McDannald, 2010). Analysis of the functional role of the RSC across multiple conditioning paradigms informs a broader understanding of the RSC’s contributions to the expression of fear (e.g., Maren, 2008).

Neither pre-training RSC lesions (Experiment 1) nor post-extinction RSC lesions (Experiment 2) had any measurable impact on ABA renewal of conditioned suppression. Thus, the ability of the context to modulate responding to an extinguished CS does not critically rely on the RSC. This extends a recent study examining the effects of RSC inactivation on extinction of freezing to a tone CS (Kwapis et al., 2014, Experiment 4). In that study, after conditioning in Context A, extinction occurred in Context B with rats receiving pre-extinction infusions of either an NMDAR receptor antagonist (APV) or vehicle into the anterior RSC. In a drug-free test the next day in Context B, freezing to the tone CS was similar for rats that received either APV or vehicle infusions, suggesting that plasticity in the RSC is not necessary for extinction of delay fear conditioning. However, in that experiment, since testing occurred in Context B it was not clear if plasticity in the RSC was required for the contextual encoding of extinction. It is possible, for example, to impair renewal without affecting the rate of extinction itself (e.g, Ji & Maren, 2005, Experiment 2).

Although several studies have demonstrated a role for the hippocampus in extinction and renewal, especially in experiments measuring conditioned freezing (e.g., Corcoran et al., 2005; Corcoran & Maren, 2001, 2004; Ji & Maren, 2005), there are other studies, in both appetitive and aversive conditioning paradigms, that have failed to find hippocampal involvement in renewal (aversive conditioning: Frohardt et al., 2000; Wilson et al., 1995; appetitive conditioning: Campese & Delamater, 2013). For example, Bouton and colleagues found no impact of hippocampal or fornix lesions on ABA renewal in a conditioned suppression paradigm (Frohardt et al., 2000; Wilson et al., 1995). However, since the experiments by Bouton and colleagues, and the current Experiment 1, involved pre-training lesions it is possible that other brain regions were able to compensate for any loss of function induced by the lesions. This reasoning is in line with a dynamic view of memory systems (e.g., Fanselow, 2010). According to this perspective, there are primary and alternative pathways capable of contextual learning and memory. Although the primary system typically dominates in intact animals, if this pathway is damaged (i.e., pre-training lesions) then other regions/pathways are capable of forming context representations. Since the primary system is thought to dominate in intact animals, post-extinction lesions are expected to have a severe impact on behavior. In Experiment 2, there was no impact of post-extinction lesions of either the RSC or DH on renewal, demonstrating that even when compensation is not possible, neither the RSC nor DH are necessary for renewal of conditioned suppression.

The current experiments, and the experiments by Bouton and colleagues (Frohardt et al., 2000; Wilson et al., 1995), examined ABA renewal after extinction of conditioned suppression. In contrast to the AAB and ABC forms of renewal, since ABA renewal involves a return to the original conditioning context, we cannot be sure that removal from the extinction context was the sole determinant of renewal (i.e., the mechanism depicted in Figure 1). At least theoretically, there are several other mechanisms that could result in response recovery upon a return to Context A, including: 1) fear conditioned directly to Context A, 2) fear conditioned directly to a configuration of Context A and the CS, or 3) Context A acting as an occasion setter and modulating the retrieval of the association between the CS and US (Harris, Jones, Bailey, & Westbrook, 2000; Bouton & Swartzentruber, 1986; Bouton & King, 1983; Nelson et al., 2011). It is worth noting that Bouton & King (1983) observed ABA renewal of conditioned suppression, and found no evidence for the former two mechanisms. Since the current experiments did not include independent assessment of the associative value of Context A, it is not possible to conclusively state if any of these mechanisms contributed to the response recovery observed. However, the fact that Experiment 2 examined ABA renewal cannot fully account for the finding that DH lesions had no impact on renewal. Ji and Maren (2005) found that electrolytic lesions of the dorsal hippocampus impaired ABA renewal of conditioned freezing, indicating that at least under some conditions the hippocampus is necessary for ABA renewal (see also Zelikowsky et al., 2012). Nevertheless, it remains to be determined if the RSC and/or DH contribute to renewal of conditioned suppression where renewal occurs in a context different from the context of conditioning (e.g., AAB and ABC renewal).

In Experiment 3, we found that RSC and DH lesions impaired performance in an object-in-place procedure, replicating previous findings (e.g., Vann & Aggleton, 2002). Thus, our lesions were sufficient to induce behavioral deficits. It is tempting to speculate about why we found impairments in object-in-place performance, but not renewal, given that both procedures seemingly involve “recognizing” an object or stimulus in a new location or context. However, the numerous procedural differences make this comparison difficult. Nevertheless, it is interesting to note that there is an explicit spatial component to the object-in-place procedure, which might make it especially sensitive to RSC and DH involvement (e.g., Vann, Aggleton, & Maguire, 2009). Indeed, renewal is not observed in conditioned suppression when the only differences between Contexts A and B are their spatial location in the laboratory, and unintended differences between copies of the same box (e.g., Thomas, Larson, & Aryes, 2003). Thus, RSC involvement in object-in-place performance and not renewal of conditioned fear could be the result of the former placing stronger demands on spatial processing than the latter.

In the current experiments, RSC and DH damage was produced by electrolytic lesions, which damages both cell bodies and fiber tracts, including fibers passing through the region. One benefit of electrolytic lesions is that, in our laboratory, these lesions typically produce more damage to the RSC than neurotoxic lesions (e.g, Keene & Bucci, 2008c), which may be especially important considering size of the RSC (~8 mm in length). Although these lesions had no impact on renewal, they did impact performance on the object-in-place procedure, demonstrating that damage to either the RSC or DH was sufficient to produce behavioral impairments. However, it is possible that the object-in-place task is simply more sensitive to RSC and DH damage than renewal. Thus, we cannot rule out the possibility that even greater damage to either area would impact renewal. It is worth noting however, that single-site infusions of pharmacological agents into the RSC have been shown to impact behavior (e.g., Corcoran et al., 2001; Kwapis et al., 2014, 2015), and single-site infusions into the DH have been shown to attenuate renewal of conditioned freezing (e.g., Corcoran et al., 2001; Corcoran & Maren, 2001, 2004). Presumably, local infusion would have less of an impact on the entire region than the current lesions, especially with respect to the RSC given its size. These caveats aside, the data reported here suggest that neither the RSC nor DH is involved in renewal of conditioned suppression.

In summary, pre-training RSC lesions had no effect on acquisition, extinction, or renewal of conditioned suppression. Likewise, post-extinction lesions of either the RSC or DH did not impact renewal. Overall, this suggests that neither the RSC nor DH are necessary for contextual encoding and/or retrieval of extinction in a conditioned suppression paradigm. It is still not clear what neural mechanisms support renewal of conditioned suppression, and it remains to be determined why damage to the hippocampus does not impact renewal in this paradigm (see also Frohardt et al., 2000; Wilson et al., 1995). One possibility is that the conditioned suppression paradigm, which requires extensive exposure to both contexts during lever-press training, might naturally recruit brain regions other than the hippocampus and the RSC. There is evidence, for example, that the hippocampus is not required for contextual fear conditioning that is distributed across multiple sessions (Lehman et al., 2009; see Rudy, 2009). However, this is just one of many differences between studies that have found hippocampal involvement in renewal, and those that have not. Additional studies are required to determine what the crucial differences are, and the neural mechanisms that control renewal of conditioned suppression.

Highlights.

Pre-training lesions of the retrosplenial cortex (RSC) had no impact on renewal after extinction of conditioned fear.

RSC lesions had no impact on acquisition or extinction of conditioned suppression.

RSC lesions impaired performance in an object-in-place procedure.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Science Foundation Grant IOS1353137 (D.J.B.) and National Institutes of Health Grant MH105125 (T.P.T.). We thank Max Mehlman for technical assistance.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Bouton ME. Context, time, and memory retrieval in the interference paradigms of Pavlovian learning. Psychological Bulletin. 1993;114:80–99. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.114.1.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouton ME. Signals for whether versus when an event will occur. In: Bouton ME, Fanselow MS, editors. Learning, motivation, and cognition: The functional behaviorism of Robert C. Bolles. Washington, D. C.: American Psychological Association; 1997. pp. 385–409. [Google Scholar]

- Bouton ME. Context, ambiguity, and unlearning: Sources of relapse after behavioral extinction. Biological Psychiatry. 2002;52:976–986. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(02)01546-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouton ME. Context and behavioral processes in extinction. Learning & Memory. 2004;11:485–494. doi: 10.1101/lm.78804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouton ME. The multiple forms of “context” in associative learning theory. In: Mesquita B, FeldmanBarrett L, Smith ER, editors. The mind in context. New York: The Guilford Press; 2010. pp. 233–258. [Google Scholar]

- Bouton ME, Bolles RC. Contextual control of the extinction of conditioned fear. Learning and Motivation. 1979;10:445–466. [Google Scholar]

- Bouton ME, Bolles RC. Conditioned fear assessed by freezing and by the suppression of three different baselines. Animal Learning & Behavior. 1980;8:429–434. 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Bouton ME, King DA. Contextual control of the extinction of conditioned fear: Tests for the associative value of the context. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Animal Behavior Processes. 1983;9:248–265. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouton ME, Nelson JB. Context-specificity of target versus feature inhibition in a feature negative discrimination. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Animal Behavior Processes. 1994;20:51–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouton ME, Nelson JB. Mechanisms of feature-positive and feature-negative discrimination learning in an appetitive conditioning paradigm. In: Schmajuk N, Holland PC, editors. Occasion setting: Associative learning and cognition in animals. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 1998. pp. 69–112. [Google Scholar]

- Bouton ME, Ricker ST. Renewal of extinguished responding in a second context. Animal Learning & Behavior. 1994;22:317–324. [Google Scholar]

- Bouton ME, Swartzentruber D. Analysis of the associative and occasion-setting properties of contexts participating in a Pavlovian Discrimination. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Animal Behavior Processes. 1986;12:333–350. [Google Scholar]

- Bouton ME, Todd TP. A fundamental role for context in instrumental learning and extinction. Behavioural Processes. 2014;104:13–19. doi: 10.1016/j.beproc.2014.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bucci DJ, Robinson S. Toward a conceptualization of retrohippocampal contributions to learning and memory. Neurobiology of learning and memory. 2014;116:197–207. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2014.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campese V, Delamater AR. ABA and ABC renewal of conditioned magazine approach are not impaired by dorsal hippocampus inactivation or lesions. Behavioral Brain Research. 2013;248:62–73. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2013.03.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corcoran KA, Desmond TJ, Frey KA, Maren S. Hippocampal inactivation disrupts the acquisition and contextual encoding of fear extinction. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2005;25:8978–8987. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2246-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corcoran KA, Maren S. Hippocampal inactivation disrupts contextual retrieval of fear memory after extinction. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2001;21:1720–1726. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-05-01720.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corcoran KA, Maren S. Factors regulating the effects of hippocampal inactivation on renewal of conditional fear after extinction. Learning & Memory. 2004;11:598–603. doi: 10.1101/lm.78704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delamater AR, Westbrook RF. Psychological and neural mechanisms of experimental extinction: a selective review. Neurobiology of Learning and Memory. 2014;108:38–51. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2013.09.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fanselow MS. From contextual fear to a dynamic view of memory systems. Trends in Cognitive Science. 2010;14:7–15. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2009.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frohardt RJ, Guarraci FA, Bouton ME. The effects of neurotoxic hippocampal lesions on two effects of context after fear extinction. Behavioral Neuroscience. 2000;114:227–240. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.114.2.227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris JA, Jones ML, Bailey GK, Westbrook RF. Contextual control over conditioned responding in an extinction paradigm. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Animal Behavior Processes. 2000;26:174–185. doi: 10.1037//0097-7403.26.2.174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji J, Maren S. Electrolytic lesions of the dorsal hippocampus disrupt renewal of conditional fear after extinction. Learning & Memory. 2005;12:270–276. doi: 10.1101/lm.91705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji J, Maren S. Differential roles for hippocampal areas CA1 and CA3 in the contextual encoding and retrieval of extinguished fear. Learning & Memory. 2008;15:244–251. doi: 10.1101/lm.794808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keene CS, Bucci DJ. Contributions of the retrosplenial and posterior parietal cortices to cue-specific and contextual fear conditioning. Behavioral Neuroscience. 2008a;122:89–97. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.122.1.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keene CS, Bucci DJ. Involvement of retrosplenial cortex in processing multiple conditioned stimuli. Behavioral Neuroscience. 2008b;122:651–658. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.122.3.651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keene CS, Bucci DJ. Neurotoxic lesions of retrosplenial cortex disrupt signaled and unsignaled contextual fear conditioning. Behavioral Neuroscience. 2008c;122:1070–1077. doi: 10.1037/a0012895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwapis JL, Jarome TJ, Lee JL, Gilmartin MR, Helmstetter FJ. Extinguishing trace fear engages the retrosplenial cortex rather than the amygdala. Neurobiology of Learning and Memory. 2014;113:41–54. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2013.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwapis JL, Jarome TJ, Lee JL, Helmstetter FJ. The retrosplenial cortex is involved in the formation of memory for context and trace fear conditioning. Neurobiology of Learning and Memory. 2015;123:110–116. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2015.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann H, Sparks FT, Spanswich SC, Hadikin C, McDonald RJ, Sutherland RJ. Making context memories independent of the hippocampus. Learning & Memory. 2009;16:417–420. doi: 10.1101/lm.1385409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maren S. Neurobiology of Pavlovian fear conditioning. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2001;24:897–931. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.24.1.897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maren S. Pavlovian fear conditioning as a behavioral assay for hippocampus and amygdala function: cautions and caveats. European Journal of Neuroscience. 2008;28:1661–1666. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2008.06485.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maren S. Seeking a spotless mind: extinction, deconsolidation, and erasure of fear memory. Neuron. 2011;70:830–845. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.04.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maren S, Phan KL, Liberzon I. The contextual brain: implications for fear conditioning, extinction and psychopathology. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2013;14:417–428. doi: 10.1038/nrn3492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maren S, Quirk GJ. Neuronal signaling of fear memory. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2004;5:844–852. doi: 10.1038/nrn1535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDannald MA. Contributions of the amygdala central nucleus and ventrolateral periaqueductal grey to freezing and instrumental suppression in Pavlovian fear conditioning. Behavioural Brain Research. 2010;211:111–117. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2010.03.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mumby DG, Gaskin S, Glenn MJ, Schramek TE, Lehmann H. Hippocampal damage and exploratory preference in rats: memory for objects, places and contexts. Learning & Memory. 2002;9:49–57. doi: 10.1101/lm.41302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller AM, Vedder LC, Law LM, Smith DM. Cues, context, and long-term memory: the role of the retrosplenial cortex in spatial cognition. Front Hum Neurosci. 2014;8:586. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2014.00586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson JB, Sanjuan MC, Vadillo-Ruiz S, Pérez J, León SP. Experimental renewal in human participants. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Animal Behavior Processes. 2011;37:58–70. doi: 10.1037/a0020519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranganath C, Ritchey M. Two cortical systems for memory-guided behaviour. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2012;13(10):713–726. doi: 10.1038/nrn3338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rescorla RA. Experimental extinction. In: Mowrer Klein, BRR S., editors. Handbook of contemporary learning theories. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaaum; 2001. pp. 119–154. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson S, Keene CS, Iaccarino HF, Duan D, Bucci DJ. Involvement of retrosplenial cortex in forming associations between multiple sensory stimuli. Behavioral Neuroscience. 2012;125:578–587. doi: 10.1037/a0024262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson S, Poorman CE, Marder TJ, Bucci DJ. Identification of functional circuitry between retrosplenial and postrhinal cortices during fear conditioning. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2012;32:12076–12086. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2814-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson S, Todd TP, Pasternak AR, Luikart BW, Skelton PD, Urban DJ, Bucci DJ. Chemogenetic silencing of neurons in retrosplenial cortex disrupts sensory preconditioning. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2014;34(33):10982–10988. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1349-14.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudy JW. Context representations, context functions, and the parahippocampal - hippocampal system. Learning & Memory. 2009;16:573–585. doi: 10.1101/lm.1494409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugar J, Witter MP, Strien NM, Cappaert NL. The retrosplenial cortex: intrinsic connectivity and connections with the (para) hippocampal region in the rat. An interactive connectome. Frontiers in neuroinformatics. 2011;5(7):1–13. doi: 10.3389/fninf.2011.00007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas BL, Larsen N, Ayres JJB. Role of context similarity in ABA, ABC, and AAB renewal paradigms: implications for theories of renewal and for treating human phobias. Learning and Motivation. 2003;34:410–436. [Google Scholar]

- Todd TP, Bucci DJ. Retrosplenial cortex and long-term memory: Molecules to behavior. Neural plasticity. 2015;2015:414173. doi: 10.1155/2015/414173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todd TP, Huszár R, DeAngeli NE, Bucci DJ. Lesions of the retrosplenial cortex have no impact on second-order fear conditioning, but attenuate first-order discrimination learning. Neurobiology of Learning & Memory. 2016;133:257–264. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2016.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todd TP, Vurbic D, Bouton ME. Bheavioral and neurobiological mechanisms of extinction in Pavlovian and instrumental learning. Neurobiology of Learning and Memory. 2014;108:52–64. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2013.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vann SD, Aggleton JP. Extensive cytotoxic lesions of the rat retrosplenial cortex reveal consistent deficits on tasks that allocentric spatial memory. Behavioral Neuroscience. 2002;116:85–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vann SD, Aggleton JP, Maguire EA. What does the retrosplenial cortex do? Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2009;10:792–803. doi: 10.1038/nrn2733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vervliet B, Craske MG, Hermans D. Fear extinction and relapse: state of the art. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2013;9:215–248. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-050212-185542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vurbic D, Bouton ME. A contemporary behavioral perspective on extinction. In: McSweeney FKB, editor. Wiley-Blackwell Handbook of Operant and Classical Conditioning. New York: Wiley-Blackwell; 2014. pp. 53–76. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson A, Brooks DC, Bouton ME. The role of the rat hippocampal system in several effects of context in extinction. Behavioral Neuroscience. 1995;109:828–836. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.109.5.828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyss JM, Van Groen T. Connections between the retrosplenial cortex and the hippocampal formation in the rat: a review. Hippocampus. 1992;2(1):1–11. doi: 10.1002/hipo.450020102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zelikowsky M, Pham DL, Fanselow MS. Temporal factors control hippocampal contributions to fear renewal after extinction. Hippocampus. 2012;22:1096–1106. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]