Abstract

Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) is a human γ-herpesvirus associated with cancer, including Burkitt lymphoma, nasopharyngeal, and gastric carcinoma. EBV reactivation in latently infected B cells is essential for persistent infection whereby B cell receptor (BCR) activation is a physiologically relevant stimulus. Yet, a global view of BCR activation-regulated protein ubiquitination is lacking when EBV is actively replicating. We report here, for the first time, the long-term effects of IgG cross-linking-regulated protein ubiquitination and offer a basis for dissecting the cellular environment during the course of EBV lytic replication. Using the Akata-BX1 (EBV+) and Akata-4E3 (EBV−) Burkitt lymphoma cells, we monitored the dynamic changes in protein ubiquitination using quantitative proteomics. We observed temporal alterations in the level of ubiquitination at ∼150 sites in both EBV+ and EBV− B cells post-IgG cross-linking, compared with controls with no cross-linking. The majority of protein ubiquitination was downregulated. The upregulated ubiquitination events were associated with proteins involved in RNA processing. Among the downregulated ubiquitination events were proteins involved in apoptosis, ubiquitination, and DNA repair. These comparative and quantitative proteomic observations represent the first analysis on the effects of IgG cross-linking at later time points when the majority of EBV genes are expressed and the viral genome is actively being replicated. In all, these data enhance our understanding of mechanistic linkages connecting protein ubiquitination, RNA processing, apoptosis, and the EBV life cycle.

Keywords: : proteomics, big data, Association Study

Introduction

Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) is a human γ-herpesvirus that establishes lifelong persistent infections and is closely associated with several types of cancers, including Burkitt lymphoma, nasopharyngeal, and gastric carcinoma (Tsao et al., 2015; Vockerodt et al., 2015). EBV reactivation in latently infected B cells plays a critical role in lifelong persistent infection and transmission to uninfected populations.

One of the physiologically relevant stimuli for EBV reactivation is antigen-induced B cell receptor (BCR) activation. The cellular response to BCR activation involves the assembly of BCR signaling proteins that regulate a cascade of downstream signaling events, including protein phosphorylation and ubiquitination (Jayasundera et al., 2014; Matsumoto et al., 2009; Satpathy et al., 2015). System-wide identification of downstream signaling events has revealed important roles for phosphorylation and ubiquitination within minutes of the BCR activation process. Some of these early signaling events have been shown to play a critical role in triggering EBV reactivation (Bryant and Farrell, 2002).

In addition to the early signaling events, BCR activation by IgG cross-linking potentially reprograms the cellular environment during EBV lytic replication (Mattes et al., 2009; Yuan et al., 2006). Therefore, to better understand the contribution of the B cell environment to EBV life cycle, it is important to dissect the long-term signaling alterations upon BCR activation.

Ubiquitination, catalyzed by a cascade of three enzymes, plays important roles in the control of key cellular processes, including signal transduction, cell cycle progression, transcriptional regulation, and apoptosis. The EBV life cycle is tightly associated with the ubiquitination and deubiquitination pathways (Shackelford and Pagano, 2004, 2005). For example, the E3 ubiquitin ligase, RNF4, triggers the ubiquitination of the EBV transactivator, RTA, to limit EBV lytic replication and virion production (Yang et al., 2013). EBV latent membrane protein 1 (LMP1) induces K63-linked ubiquitination of p53 to rescue tumor cell apoptosis (Li et al., 2012a).

LMP1 can also stimulate receptor-interacting protein (RIP)-dependent TNFR-associated factor 6 (TRAF6)-triggered K63-linked ubiquitination of IRF7 (Huye et al., 2007; Ning et al., 2008). However, LMP1-stimulated IRF7 ubiquitination is negatively regulated by the cellular deubiquitinase A20 (Ning and Pagano, 2010). Others have shown that LMP1 coordinates with TRAF1-mediated polyubiquitin signaling to promote activation of the cell survival pathway (Greenfeld et al., 2015).

The ubiquitin ligase Itch regulates EBV maturation through BFRF1-mediated nuclear envelope modification (Lee et al., 2016). EBV EBNA3C regulates the ubiquitin ligase activity of Mdm2 to facilitate p53 ubiquitination and degradation (Forte and Luftig, 2009; Saha et al., 2009). The EBV EBNA1 protein recruits deubiquitinase USP7 to the EBV latent origin of replication to alter histone modification (Sarkari et al., 2009). EBV LMP1 induces the expression of a cellular deubiquitinase UCH-L1 during viral latency (Bentz et al., 2014), while EBV EBNA3 family proteins target a USP46/USP12 deubiquitinase complex for virus-induced growth transformation (Ohashi et al., 2015).

In addition, EBV also encodes a deubiquitinase BPLF1, which regulates the deubiquitination of viral and cellular proteins to foster viral replication (Gastaldello et al., 2010; Saito et al., 2013; van Gent et al., 2014; Whitehurst et al., 2009, 2012). BPLF1 also coordinates with Rad6/18 ubiquitin complex to regulate virus infectivity (Kumar et al., 2014). Taken together, these studies indicate that ubiquitination plays an important role in the EBV life cycle. However, a global view of BCR activation-regulated protein ubiquitination when EBV is being actively replicated is still lacking.

In this study, we employed stable isotope labeling by amino acid in cell culture (SILAC)-based quantitative proteomics (Li et al., 2015; Pinto et al., 2015; Zhong et al., 2012) to monitor the dynamic changes in protein ubiquitination in EBV+ and EBV− B cells upon IgG cross-linking-mediated BCR activation. For the first time, this report describes the long-term effects of BCR activation on protein ubiquitination, which offers a basis for dissecting the cellular environment during the course of EBV lytic replication.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture and treatment

The Akata-BX1 (EBV+) and Akata-4E3 (EBV−) cells were grown in RPMI 1640 media supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Gibco) in 5% CO2 at 37°C (Li et al., 2011, 2012b). To label cells with stable isotopic amino acids, EBV+ and EBV− cells were propagated in RPMI 1640 SILAC media deficient in both L-lysine and L-arginine (Cat. no. 26140079; Thermo Fisher Scientific) and supplemented with light lysine (12C614 N2-K) and arginine (12C614 N4-R) for light state (Cat. nos. L-9037 and A-8094; Sigma),13C614 N2-K and 13C614 N4-R for medium state (Cat. nos. CLM-2247-H-1 and CLM-2265-H-1; Cambridge Isotope Laboratories), and 13C615 N2-K and 13C615 N4-R for heavy state labeling (Cat. nos. CNLM-291-H-1 and CNLM-539-H-1; Cambridge Isotope Laboratories) (Li et al., 2015). Cells were cultured for at least six doubling times for complete incorporation. The light-labeled EBV+ and EBV− cells were untreated (0 h) and the medium- and heavy-labeled EBV+ and EBV− cells were treated with goat anti-human IgG (1:200; Cat. No. 55087; MP Biomedicals) for 24 and 48 h, respectively.

Sample preparation

The untreated and IgG-treated cells (5 × 108 cells each condition) were harvested by centrifugation at 400 g for 5 min. Pellets were washed twice by resuspending in 250 mL of prechilled Dulbecco's PBS (Cat. no. 10010-049; Thermo Fisher Scientific). The cell pellets were resuspended in 20 mL freshly prepared Urea Lysis Buffer [20 mM HEPES pH 8.0, 9 M urea, and protease inhibitors (Cat. no. 05892791001; Roche) for sonication. The lysate was centrifuged at 15,000 g for 10 min at 18°C. The supernatant was stored at −80°C for proteomic analysis. Protein concentration was measured by BCA assay (Cat. no. 23227; Pierce). Peptides were prepared by an in-solution tryptic digestion protocol (Li et al., 2015). Trypsin digestion efficiency was assessed by SDS-PAGE and Coomassie Brilliant Blue staining before further processing.

Protein digests were acidified by 1% (v/v) trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) and subjected to centrifugation at 2000 g at 25°C for 5 min. The supernatant of the protein digests was loaded onto a Sep-Pak C18 column (Cat. no. WAT051910; Waters, Columbia, MD) equilibrated with 0.1% (v/v) TFA. Columns were washed with 6 mL of 0.1% (v/v) TFA twice and peptides were eluted in 2 mL of 40% (v/v) acetonitrile (ACN) with 0.1% (v/v) TFA three times. Eluted peptides were lyophilized and subjected to enrichment for ubiquitinated peptides by immunoprecipitation using anti-K-ɛ-GG antibody-conjugated beads (Cat. no. 5562; Cell Signaling Tech), according to the manufacturer's instructions.

In brief, anti-K-ɛ-GG antibody beads were washed four times with 1 mL of the ice-cold immunoprecipitation buffer (IAP) (50 mM MOPS, pH 7.2, 10 mM sodium phosphate, 50 mM NaCl). For each of the biological replicates, 15 mg lyophilized peptides were resuspended in 1.5 mL IAP buffer and incubated for 2 h with the anti-K-ɛ-GG antibody beads on a rotator at 4°C. Anti-K-ɛ-GG antibody beads were washed three times with 1 mL of cold IAP buffer and twice with 1 mL of cold H2O before elution with 65 μL of 0.15% TFA solution twice. Eluted peptide supernatants were desalted using C18 STAGE tips. STAGE tips were packed with a C18 Empore disk (Cat. no. 2315, 3M; St. Paul, MN) and conditioned with 50 μL of 100% ACN and two applications of 50 μL of 0.1% TFA before the peptide solution was loaded. Peptides were washed twice with 50 μL of 0.1% TFA and eluted with three times 20 μL of 50% ACN (0.1% TFA). Desalted peptides were dried and kept at −80°C in a freezer until further analysis.

Liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry analysis

The enriched peptides were analyzed on an LTQ-Orbitrap Elite mass spectrometer interfaced with Easy-nLC II nanoflow LC system (Thermo Scientific) using the same parameters as preciously described (Li et al., 2015).

MS data analysis

The MS derived data were screened using MASCOT (version 2.2.0) and SEQUEST search algorithms against a human RefSeq database (version 59) using Proteome Discoverer 1.4 (Thermo Scientific). The search parameters for both algorithms included carbamidomethylation of cysteine residues as a fixed modification and N-terminal acetylation, oxidation at methionine, GlyGly addition to lysine, and SILAC labeling 13C615 N2-K, 12C614 N2-K, 12C6 14N4-R, and 13C615 N4-Ras variable modifications. MS/MS spectra were searched with a precursor mass tolerance of 10 ppm and fragment mass tolerance of 0.05 Da. Trypsin was specified as the protease and a maximum of two missed cleavages were allowed.

The data were screened against a target decoy database and the false discovery rate (FDR) was set to 1% at the peptide level. The SILAC ratio for each peptide-spectrum match (PSM) was calculated by the quantitation node. The wrongly assigned ubiquitination sites (the C-terminal lysine in the peptide) were manually corrected. Because BCR activation triggers a dramatic downregulation in ubiquitination at later time points, it is not suitable to obtain a cutoff value using a normal distribution-based method for regulated ubiquitination. Therefore, we applied a commonly used cutoff value of twofold change for differentially regulated ubiquitination upon BCR activation (Satpathy et al., 2015; Tong et al., 2014). Peptides with ratios greater than twofold change were used for further analysis.

Data availability

The MS data have been deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium (http://proteomecentral.proteomexchange.org) through the PRIDE partner (Vizcaino et al., 2016) repository with the dataset identifier PXD004562.

Immunoblotting

Cells were harvested and lysed in 2 × SDS-PAGE sample buffer and boiled for 5 min. The samples were separated on 4–20% TGX gels (Biorad), transferred to PVDF membranes, and probed with primary and horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies. Primary antibodies purchased from Cell Signaling Technology were anti-cleaved PARP (Cat. no. 5625), anti-cleaved caspase substrate motif (Cat. no. 8698), and anti-K63-linkage-specific polyubiquitin (D7A11) Rabbit mAb (Cat. no. 5621). Rabbit anti-β-actin polyclonal antibody (Cat. no. A5441) was obtained from Sigma Aldrich. Rabbit anti-Bcl-2 was bought from Bethyl (Cat. no. A303-675A). Mouse anti-ZTA antibody (Cat. no. 11-007) was purchased from Argene. Mouse anti-BGLF4 antibody has been described previously (Wang et al., 2005).

Bioinformatic analysis

The gene ontology (GO) annotation and enrichment of differentially regulated ubiquitinated proteins were obtained through Cytoscape (V3.2.0) plugin BiNGO following the methods described in Maere et al. (2005). Statistical significance was determined by hypergeometric test after FDR correction.

Results and Discussion

Strategy for analysis of BCR activation-regulated ubiquitination during EBV reactivation

Previously, proteomic studies were performed to examine the ubiquitination events shortly after IgG cross-linking of mouse or human B cell lines (Jayasundera et al., 2014; Satpathy et al., 2015). To obtain a global view of the long-term effects on protein ubiquitination, we utilized SILAC-based proteomics to survey the dynamic changes in ubiquitination in EBV+ B cells upon IgG cross-linking (Harsha et al., 2008; Ong et al., 2002). To better understand the effects of BCR activation on ubiquitination, we used both Akata-BX1 (EBV+) (Molesworth et al., 2000) and Akata-4E3 (EBV−) B cells (Shimizu et al., 1994). The Akata-BX1 (EBV+) cell line was derived from Akata-4E3 (EBV−) B cells with recombinant EBV. Therefore, both cell lines have the same genetic background, allowing for a direct comparison.

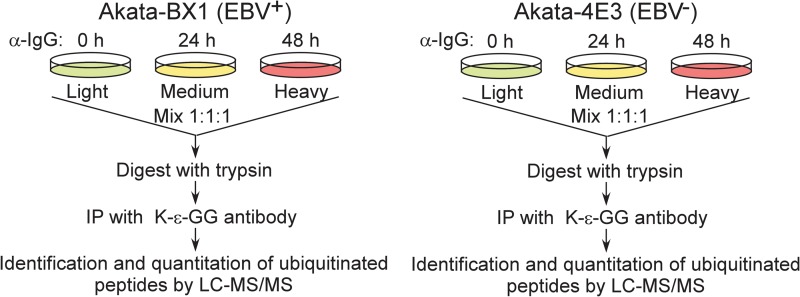

These Burkitt lymphoma cells express surface immunoglobulin receptors of the G(κ) (IgG) class, which is suitable to investigate BCR activation-regulated changes in ubiquitination (Daibata et al., 1990; Shimizu et al., 1994; Takada, 1984; Takada et al., 1991). As shown in Figure 1, both EBV+ and EBV− cells were isotopically labeled using light (12C6, 14N2-lysine and 12C6, 14N4-arginine), medium (13C6, 14N2-lysine and 13C6, 14N4-arginine), and heavy (13C6, 15N2-lysine and 13C6, 15N4-arginine) amino acids, respectively. IgG was added into the medium- and heavy-labeled cells for 24 and 48 h before harvesting. An equal amount of cell lysate was mixed and then digested by trypsin.

FIG. 1.

Schematic illustration of the SILAC-based quantitative proteomic approach. Akata-BX1 (EBV+) and Akata-4E3 (EBV−) cells were cultured in light, medium, and heavy media, as indicated. EBV, Epstein-Barr virus; SILAC, stable isotope labeling by amino acid in cell culture.

To facilitate the identification of ubiquitination events, we employed a di-Gly capture method to enrich ubiquitinated peptides (Tong et al., 2014). The enriched ubiquitinated peptides were then analyzed on an LTQ-Obitrap Elite mass spectrometer (Fig. 1). The acquired data were processed and searched using MASCOT and SEQUEST search algorithms through the Proteome Dicoverer platform and stringently filtered for an FDR of 1% at the peptide level. A good correlation was observed between the replicated analyses for both EBV+ and EBV− cells (Supplementary Fig. S1).

Global view of proteomic data

To obtain a global picture of the regulated ubiquitination events, we first performed a distribution analysis. Interestingly, we found that there were widespread changes in protein ubiquitination at the 48-h time point compared with the 24-h time point (Fig. 2A). To rule out any systematic bias on the observed changes, we also analyzed the nonubiquitinated peptides captured in our analysis. We found that the majority (>98%) of SILAC ratios of these peptides were changed less than twofold after both 24 and 48 h (Fig. 2B). These results demonstrate that the large change in protein ubiquitination was not simply due to alteration in protein levels.

FIG. 2.

Widespread changes in protein ubiquitination upon IgG cross-linking. (A) IgG cross-linking triggers widespread changes of protein ubiquitination. Scatter plot showing the SILAC ratio (24 h/0 h and 48 h/0 h) and signal intensity of ubiquitinated peptides identified from EBV+ and EBV− B cells. Red dots: peptides with ubiquitination downregulated or upregulated; Blue dots: peptides not regulated by IgG cross-linking. (B) IgG cross-linking triggers minimal changes of nonubiquitinated peptides. Scatter plot showing the SILAC ratio (24 h/0 h and 48 h/0 h) and signal intensity of nonubiquitinated peptides identified from EBV+ and EBV− B cells. Red dots: downregulated or upregulated peptides; Blue dots: peptides not regulated by IgG cross-linking. See also Supplementary Tables S1 and S2 and Supplementary Figure S1.

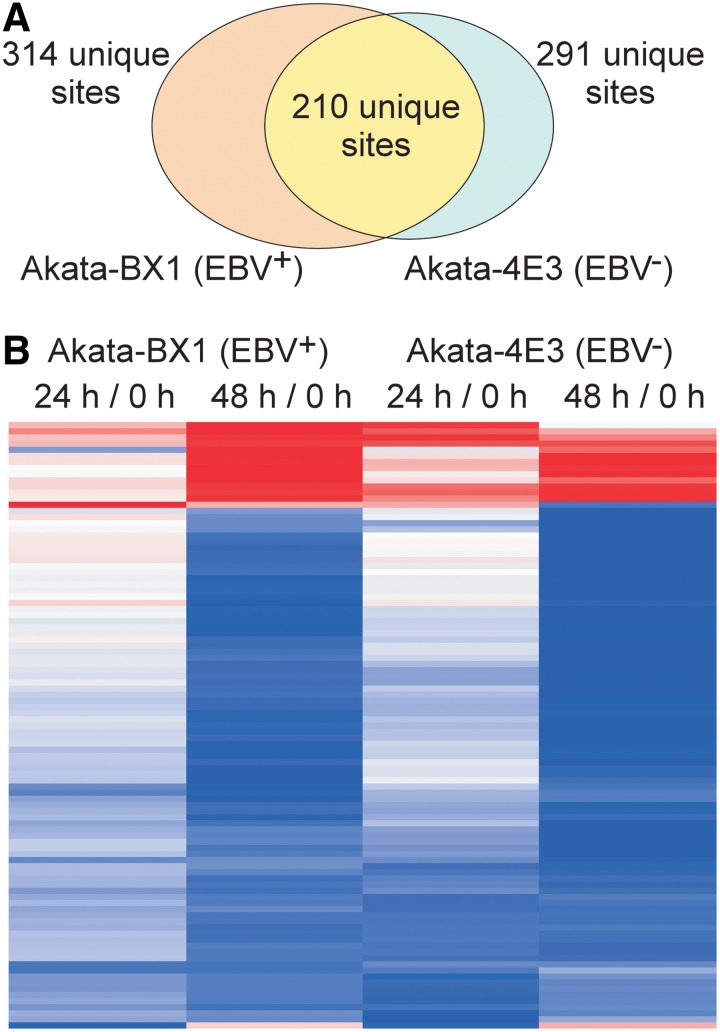

We identified 314 and 291 unique ubiquitination events for EBV+ and EBV− cells, respectively, with 210 sites identified in both cell lines (Fig. 3A). To identify ubiquitination events that were differentially regulated by IgG cross-linking, we used a cutoff value of twofold change for both increased and decreased ubiquitination. As summarized in Table 1, in EBV+ cells, ubiquitination at 7 and 29 sites showed a twofold increase at 24 and 48 h post-IgG cross-linking, respectively (Supplementary Table S1). In contrast, ubiquitination at 86 and 127 sites was downregulated by twofold at 24 and 48 h post-IgG cross-linking, respectively (Table 1 and Supplementary Table S1). Similarly, in EBV− cells, we observed 15/15 hyperubiquitination sites and 122/142 hypoubiquitination sites at 24/48 h post-IgG treatment, respectively (Table 1 and Supplementary Table S2).

FIG. 3.

Analysis of IgG-triggered protein ubiquitination in EBV+ and EBV− B cells. (A) Overlap of identified ubiquitinated sites in EBV+ and EBV− B cells. (B) Heat map analysis of ubiquitinated sites with significant changes in EBV+ B cells and the corresponding changes of these sites in EBV− B cells. Red: highest abundance; Blue: lowest abundance. See also Supplementary Table S3.

Table 1.

Summary of Identified Ubiquitinated Sites for EBV+ and EBV− B Cells

| Akata-BX1 (EBV+) | Akata-4E3 (EBV−) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unique ubiquitinated site no. | Unique ubiquitinated protein no. | Unique ubiquitinated site no. | Unique ubiquitinated protein no. | |||||

| α-IgG treatment, h | 24 | 48 | 24 | 48 | 24 | 48 | 24 | 48 |

| Upregulated | 7 | 29 | 7 | 24 | 15 | 15 | 13 | 13 |

| Downregulated | 86 | 127 | 53 | 81 | 122 | 142 | 78 | 86 |

| All quantified | 311 | 235 | 193 | 151 | 284 | 212 | 166 | 129 |

EBV, Epstein-Barr virus.

Because EBV reactivation has been shown to regulate cellular gene expression (Yuan et al., 2006), we then asked whether the general ubiquitination is also regulated by EBV reactivation. We first used a hierarchical clustering method to analyze the regulated ubiquitination events for EBV+ cells (Eisen et al., 1998), and then we matched the same ubiquitination events to those detected in the EBV− cells. Surprisingly, we found that changes in ubiquitination were highly similar for both cell lines (Fig. 3B), suggesting that IgG cross-linking plays a dominant role in regulation of protein ubiquitination regardless of EBV reactivation. In addition, we also noticed that the majority of ubiquitination gradually decreased from the 24-h time point to 48-h time point. Taken together, these global analyses suggested that there were dramatic changes in ubiquitination at later time points post-BCR activation and these changes were largely not affected by the presence of EBV.

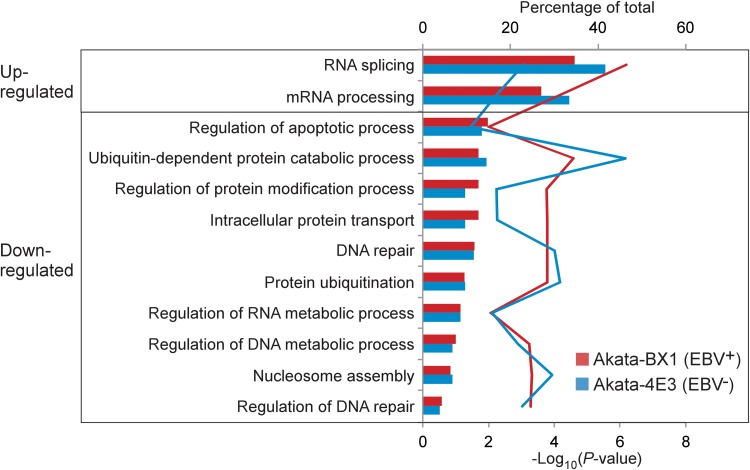

Cellular processes affected by BCR activation

To gain insight into the cellular pathways regulated by BCR activation, we performed a GO enrichment analysis of the proteins with upregulated or downregulated ubiquitination sites at either 24 or 48 h post-IgG treatment in the two cell lines by Cytoscape plugin BiNGO. The commonly enriched biological process items in both cell lines were extracted and are presented in Figure 4. Interestingly, we found that for the proteins containing upregulated ubiquitination sites, RNA splicing and mRNA-processing factors were highly enriched. For the proteins containing downregulated ubiquitination sites, factors regulating the apoptotic process, ubiquitin-dependent protein catabolic process, and DNA repair were statistically enriched. The percentage of proteins in each GO term was similar between EBV+ and EBV− cells (Fig. 4), further suggesting that IgG cross-linking played a major role in protein ubiquitination regardless of EBV status.

FIG. 4.

GO enrichment of hyper- and hypoubiquitinated proteins from EBV+ and EBV− B cells. Significantly over-represented (p < 0.05) biological processes are shown by line chart. p values were determined by hypergeometric test after FDR correction. The percentage of each GO item is shown by bar chart. FDR, false discovery rate; GO, gene ontology.

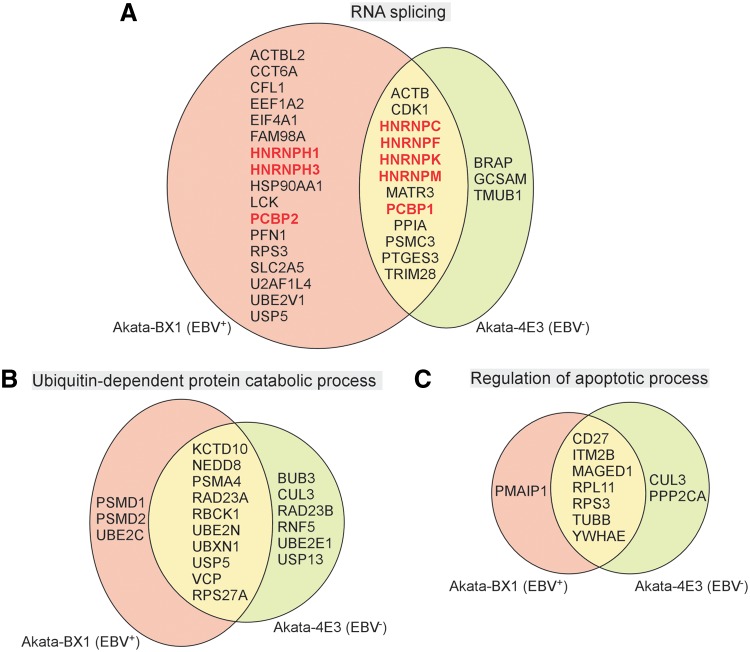

Among the hyperubiquitinated proteins, our analysis revealed that 8 of these 29 proteins in EBV+ cells and 5 of 15 proteins in EBV− cells were directly involved in RNA splicing (Fig. 5A and Supplementary Tables S1 and S2). All these RNA splicing-related proteins belong to the heterogeneous ribonucleoprotein family. Interestingly, many members of this family have been shown to play a role in the EBV life cycle. For example, HNRNPC interacts with the EBV SM splicing protein to regulate viral mRNA processing (Key et al., 1998). HNRNPK was reported to coordinate with EBNA2 to enhance viral latent membrane protein 2A (LMP2A) expression (Gross et al., 2012). We observed a dramatic increase in ubiquitination at Lys-8 of HNRNPC and Lys-198 of HNRNPK at 48 h for both EBV+ and EBV− Akata cells (Supplementary Table S3).

FIG. 5.

The overlap of proteins involved in three major GO items between EBV+ and EBV− B cells. (A) The overlap of proteins with upregulated ubiquitination sites between EBV+ and EBV− B cells. Proteins highlighted by red and bold belong to the enriched GO item of RNA splicing. (B) The overlap of proteins (containing downregulated ubiquitination sites) involved in ubiquitin-dependent protein catabolic process between EBV+ and EBV− B cells. (C) The overlap of proteins (containing downregulated ubiquitination sites) involved in regulation of apoptotic process between EBV+ and EBV− B cells.

Another RNA-binding protein, PCBP2, was recently identified as a negative regulator of EBV lytic replication (Koganti et al., 2015). The hyperubiquitination on Lys-115 observed in our screen (Supplementary Table S3) suggested that BCR activation may regulate the function of PCBP2 to facilitate the EBV lytic replication. Because HNRNPK Lys-198 and PCBP2 Lys-115 are located within the conserved RNA binding K homology (KH) domains (Teplova et al., 2011), ubiquitination on these sites may regulate their RNA binding ability and impact viral mRNA processing.

Among the hypoubiquitinated proteins detected in either EBV+ and EBV− cells, 19 proteins are involved in ubiquitin-dependent protein catabolic process, including the ubiquitin precursor protein (RPS27A), three ubiquitin conjugation enzymes (UBE2C, UBE2T, and UBE2E1), four E3 ubiquitin ligases/ligase complex subunits (RNF5, CUL3, KCTD10, and RBCK1), three proteasome subunits (PSMD1, PSMD2, and PSMA4), two deubiquitinases (USP5 and USP13), and four ubiquitin-associated proteins (RAD23A, RAD23B, UBXN1, and VCP) (Fig. 5B and Supplementary Table S3).

Consistent with previous reports (Berard et al., 1999; Donjerkovic and Scott, 2000; Yoshida et al., 2000), we also found that proteins involved in the regulation of apoptotic process were significantly enriched for both cell lines. As shown in Figure 5C, most of these proteins were identified for the two cell lines, including VCP, TUBB, MAGED1, RPS3, RPL11, CD74, YWHAB, CD27, YWHAE, and YWHAZ. Because the ubiquitin-proteasome system is highly connected with apoptosis induction (Orlowski, 1999), it is not surprising that some proteins were enriched in both ubiquitin-dependent protein catabolic process and regulation of apoptotic process, including VCP and CUL3 (Fig. 5B, C). For ubiquitin (RPS27A) itself, we detected 4 hypoubiquitination sites (K6, K11, K27, K63) with all of the levels significantly decreased at 48 h post-IgG cross-linking (Table 2).

Table 2.

The Dynamic Changes of Different Ubiquitination Sites on Ubiquitin (RPS27A) in EBV+ and EBV− B Cells upon IgG Cross-Linking

| Akata-BX1 (EBV +) | Akata-4E3 (EBV −) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 24 h/0 h | 48 h/0 h | 24 h/0 h | 48 h/0 h | |

| Ubiquitin (RPS27A) | ||||

| K6 | 0.55 | 0.13 | 0.39 | 0.10 |

| K11 | 0.67 | 0.29 | 0.57 | 0.20 |

| K27 | 0.58 | 0.17 | 0.76 | 0.24 |

| K63 | 0.92 | 0.23 | 0.44 | 0.05 |

To validate the SILAC-MS results, we performed western blot analysis using K63-linkage-specific antibody. Consistent with the MS results (Fig. 6A), we found a gradual decrease in K63-linkage-specific polyubiquitination level for both cell lines upon IgG cross-linking (Fig. 6B). Because linkage-specific polyubiquitination plays different roles in protein turnover and signaling (Adhikari and Chen, 2009; Li and Ye, 2008; Xu et al., 2009), the misregulation of ubiquitination may affect multiple aspects of normal cell function during EBV replication. Together, these results suggest that BCR activation plays a major role in the regulation of ubiquitination of proteins involved in RNA processing and apoptosis among others.

FIG. 6.

IgG cross-linking reduces ubiquitin chain formation. (A) MS spectra showing the relative abundance of ubiquitin K63 containing ubiquitinated peptide at 24 and 48 h after IgG cross-linking of both EBV+ and EBV− Akata cells. (B) Validation of SILAC results. EBV+ and EBV− B cells were treated with IgG cross-linking as indicated. Western blot analysis of K63 ubiquitination on ubiquitin (RPS27A) was performed by using K63-linkage-specific antibody. β-Actin was included as loading control.

Differential regulation of apoptosis

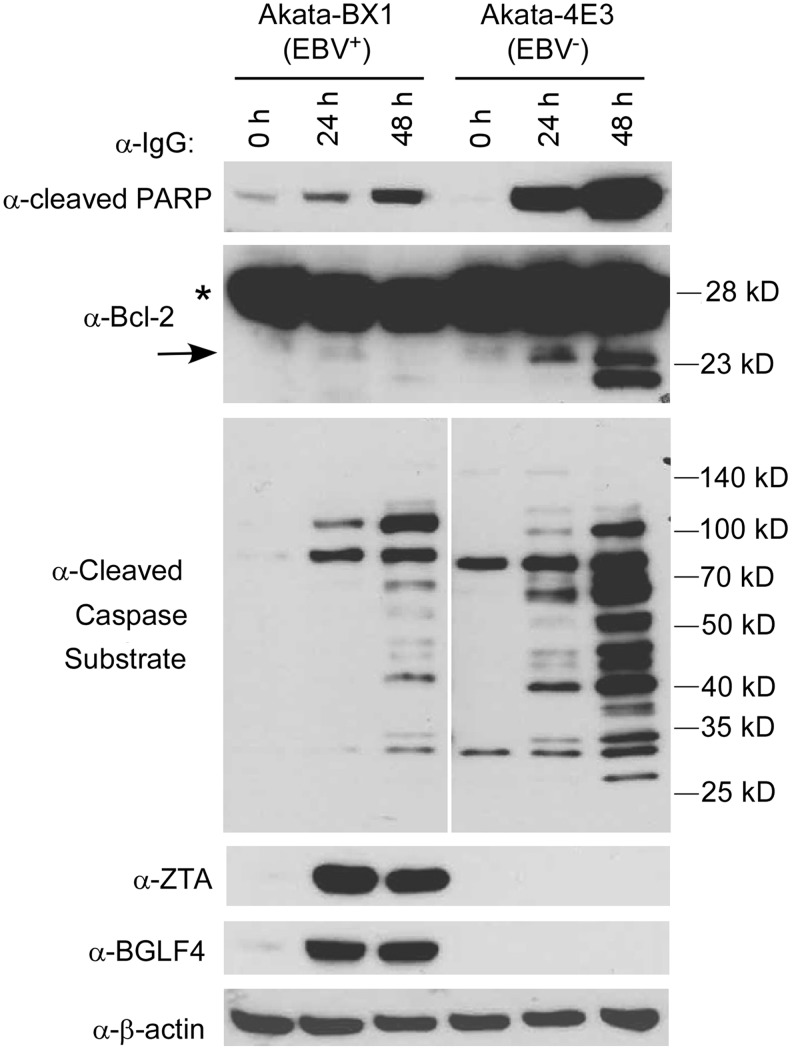

Due to the similar trend of ubiquitination for both EBV+ and EBV− cells, we tested whether apoptosis was similarly induced in these cells upon BCR activation. We first monitored the level of cleaved PARP, a marker for caspase activation and apoptosis. Interestingly, the level of cleaved PARP slightly increased in EBV+ cells, but dramatically increased in EBV− cells following IgG cross-linking (Fig. 7, top panel). To further confirm these results, we checked the level of cleaved Bcl-2, another marker of apoptosis (Kirsch et al., 1999). We found that Bcl-2 cleavage was evident in EBV− cells, but not in EBV+ cells (Fig. 7, the second panel). Furthermore, we examined the general caspase-mediated cleavage of cellular substrates by a motif-specific antibody.

FIG. 7.

IgG cross-linking triggers apoptosis induction. EBV+ and EBV− B cells were treated with IgG cross-linking as indicated. Western blot analysis showing the cleavage of PARP, Bcl-2, and general caspase substrates. Asterisk denotes uncleaved Bcl-2 and arrow denotes cleaved Bcl-2. EBV lytic transactivator ZTA and protein kinase BGLF4 blots were included to indicate lytic induction efficiency. β-Actin was included as loading control.

As expected, the cleavage signals were weaker in EBV+ cells than those seen in EBV− cells (Fig. 7, the third panel). Taken together, these results demonstrate that BCR activation-mediated apoptosis induction is partially blocked by EBV replication, which is likely due to the expression of multiple EBV proteins with antiapoptosis function, including EBNA3C and BHRF1 (a viral homology of Bcl-2) (Cai et al., 2011; Desbien et al., 2009; Kvansakul et al., 2010; McCarthy et al., 1996; Yuan et al., 2006). Future studies should focus on the ubiquitination system and its functional importance in apoptosis, RNA processing, and EBV reactivation upon BCR activation.

Conclusions and Expert Outlook

In this study, we applied quantitative proteomics to dissect the long-term effects of BCR activation in protein ubiquitination during the course of EBV lytic replication. Our study revealed that BCR activation initiates widespread changes in ubiquitination of proteins involved in multiple cellular processes, such as mRNA processing and apoptosis. Although EBV gene expression leads to dramatic changes in cellular gene expression, we found that the trend of individual protein ubiquitination was highly similar between EBV+ and EBV− cells. For hyperubiquitinated proteins, only those involved in RNA splicing and mRNA processing were highly enriched.

Interestingly, the ubiquitination sites at HNRNPK, HNRNPM, HNRNPH1/H3, PCBP1, and PCBP2 are located within their conserved RNA binding domains, indicating that ubiquitination may affect their RNA binding ability. Because EBV genes are tightly regulated by the RNA-processing machinery, ubiquitination of these RNA-processing proteins could affect viral gene processing.

Importantly, we demonstrated that IgG cross-linking also led to downregulation of ubiquitination on many proteins involved in apoptosis and that apoptosis was triggered in both EBV+ and EBV− Akata cells. However, apoptosis induction in EBV+ cells was partially suppressed compared with that seen in EBV− cells. This is consistent with the fact that EBV has evolved multiple strategies to counteract apoptosis to promote viral replication.

In summary, these comparative and quantitative proteomic observations represent the first analysis on the effects of IgG cross-linking at later time points when the majority of EBV genes are expressed and the viral genome is actively being replicated. Our study offers a global view of ubiquitination upon BCR activation and contributes new knowledge on mechanistic linkages among protein ubiquitination, RNA processing, apoptosis, and the EBV life cycle.

Supplementary Material

Abbreviations Used

- BCR

B cell receptor

- EBV

Epstein-Barr virus

- FDR

false discovery rate

- GO

gene ontology

- LC

liquid chromatography

- MS

mass spectrometry

- PSM

peptide-spectrum match

- RIP

receptor-interacting protein

- SILAC

stable isotope labeling by amino acid in cell culture

- TFA

trifluoroacetic acid

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Diane Hayward and Iain Morgan for comments and suggestions for the article. The authors acknowledge Diane Hayward for providing the Akata-4E3 (EBV−) cells, Lindsey Hutt-Fletcher for providing the Akata-BX1 (EBV+) cells, and Mei-Ru Chen for anti-BGLF4 antibody. This work was supported by NIH K99AI104828/R00AI104828 to R.L. and NIH U54GM103520, U24CA160036, and HHSN268201000032C to A.P. (http://grants.nih.gov/grants/oer.htm). R.L. received support from the VCU Philips Institute for Oral Health Research and the VCU NCI Designated Massey Cancer Center (NIH P30 CA016059).

Author Disclosure Statement

The authors declare that no conflicting financial interests exist.

References

- Adhikari A, and Chen ZJ. (2009). Diversity of polyubiquitin chains. Dev Cell 16, 485–486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentz GL, Bheda-Malge A, Wang L, Shackelford J, Damania B, and Pagano JS. (2014). KSHV LANA and EBV LMP1 induce the expression of UCH-L1 following viral transformation. Virology 448, 293–302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berard M, Casamayor-Palleja M, Billian G, Bella C, Mondiere P, and Defrance T. (1999). Activation sensitizes human memory B cells to B-cell receptor-induced apoptosis. Immunology 98, 47–54 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryant H, and Farrell PJ. (2002). Signal transduction and transcription factor modification during reactivation of Epstein-Barr virus from latency. J Virol 76, 10290–10298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai Q, Guo Y, Xiao B, et al. (2011). Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigen 3C stabilizes Gemin3 to block p53-mediated apoptosis. PLoS Pathog 7, e1002418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Daibata M, Humphreys RE, Takada K, and Sairenji T. (1990). Activation of latent EBV via anti-IgG-triggered, second messenger pathways in the Burkitt's lymphoma cell line Akata. J Immunol 144, 4788–4793 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desbien AL, Kappler JW, and Marrack P. (2009). The Epstein-Barr virus Bcl-2 homolog, BHRF1, blocks apoptosis by binding to a limited amount of Bim. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106, 5663–5668 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donjerkovic D, and Scott DW. (2000). Activation-induced cell death in B lymphocytes. Cell Res 10, 179–192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisen MB, Spellman PT, Brown PO, and Botstein D. (1998). Cluster analysis and display of genome-wide expression patterns. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 95, 14863–14868 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forte E, and Luftig MA. (2009). MDM2-dependent inhibition of p53 is required for Epstein-Barr virus B-cell growth transformation and infected-cell survival. J Virol 83, 2491–2499 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gastaldello S, Hildebrand S, Faridani O, et al. (2010). A deneddylase encoded by Epstein-Barr virus promotes viral DNA replication by regulating the activity of cullin-RING ligases. Nat Cell Biol 12, 351–361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenfeld H, Takasaki K, Walsh MJ, et al. (2015). TRAF1 coordinates polyubiquitin signaling to enhance Epstein-Barr virus LMP1-mediated growth and survival pathway activation. PLoS Pathog 11, e1004890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross H, Hennard C, Masouris I, et al. (2012). Binding of the heterogeneous ribonucleoprotein K (hnRNP K) to the Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigen 2 (EBNA2) enhances viral LMP2A expression. PLoS One 7, e42106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harsha HC, Molina H, and Pandey A. (2008). Quantitative proteomics using stable isotope labeling with amino acids in cell culture. Nat Protoc 3, 505–516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huye LE, Ning S, Kelliher M, and Pagano JS. (2007). Interferon regulatory factor 7 is activated by a viral oncoprotein through RIP-dependent ubiquitination. Mol Cell Biol 27, 2910–2918 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jayasundera KB, Iliuk AB, Nguyen A, Higgins R, Geahlen RL, and Tao WA. (2014). Global phosphoproteomics of activated B cells using complementary metal ion functionalized soluble nanopolymers. Anal Chem 86, 6363–6371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Key SC, Yoshizaki T, and Pagano JS. (1998). The Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) SM protein enhances pre-mRNA processing of the EBV DNA polymerase transcript. J Virol 72, 8485–8492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirsch DG, Doseff A, Chau BN, et al. (1999). Caspase-3-dependent cleavage of Bcl-2 promotes release of cytochrome c. J Biol Chem 274, 21155–21161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koganti S, Clark C, Zhi J, et al. (2015). Cellular STAT3 functions via PCBP2 to restrain Epstein-Barr Virus lytic activation in B lymphocytes. J Virol 89, 5002–5011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar R, Whitehurst CB, and Pagano JS. (2014). The Rad6/18 ubiquitin complex interacts with the Epstein-Barr virus deubiquitinating enzyme, BPLF1, and contributes to virus infectivity. J Virol 88, 6411–6422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kvansakul M, Wei AH, Fletcher JI, et al. (2010). Structural basis for apoptosis inhibition by Epstein-Barr virus BHRF1. PLoS Pathog 6, e1001236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee CP, Liu GT, Kung HN, et al. (2016). The ubiquitin ligase itch and ubiquitination regulate BFRF1-mediated nuclear envelope modification for Epstein-Barr virus maturation. J Virol 90, 8994–9007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Li W, Xiao L, et al. (2012a). Viral oncoprotein LMP1 disrupts p53-induced cell cycle arrest and apoptosis through modulating K63-linked ubiquitination of p53. Cell Cycle 11, 2327–2336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li R, Liao G, Nirujogi RS, et al. (2015). Phosphoproteomic profiling reveals Epstein-Barr virus protein kinase integration of DNA damage response and mitotic signaling. PLoS Pathog 11, e1005346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li R, Wang L, Liao G, et al. (2012b). SUMO binding by the Epstein-Barr virus protein kinase BGLF4 is crucial for BGLF4 function. J Virol 86, 5412–5421 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li R, Zhu J, Xie Z, et al. (2011). Conserved herpesvirus kinases target the DNA damage response pathway and TIP60 histone acetyltransferase to promote virus replication. Cell Host Microbe 10, 390–400 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W, and Ye Y. (2008). Polyubiquitin chains: Functions, structures, and mechanisms. Cell Mol Life Sci 65, 2397–2406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maere S, Heymans K, and Kuiper M. (2005). BiNGO: A Cytoscape plugin to assess overrepresentation of gene ontology categories in biological networks. Bioinformatics 21, 3448–3449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto M, Oyamada K, Takahashi H, Sato T, Hatakeyama S, and Nakayama KI. (2009). Large-scale proteomic analysis of tyrosine-phosphorylation induced by T-cell receptor or B-cell receptor activation reveals new signaling pathways. Proteomics 9, 3549–3563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattes MJ, Michel RB, Goldenberg DM, and Sharkey RM. (2009). Induction of apoptosis by cross-linking antibodies bound to human B-lymphoma cells: Expression of Annexin V binding sites on the antibody cap. Cancer Biother Radiopharm 24, 185–193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy NJ, Hazlewood SA, Huen DS, Rickinson AB, and Williams GT. (1996). The Epstein-Barr virus gene BHRF1, a homologue of the cellular oncogene Bcl-2, inhibits apoptosis induced by gamma radiation and chemotherapeutic drugs. Adv Exp Med Biol 406, 83–97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molesworth SJ, Lake CM, Borza CM, Turk SM, and Hutt-Fletcher LM. (2000). Epstein-Barr virus gH is essential for penetration of B cells but also plays a role in attachment of virus to epithelial cells. J Virol 74, 6324–6332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ning S, Campos AD, Darnay BG, Bentz GL, and Pagano JS. (2008). TRAF6 and the three C-terminal lysine sites on IRF7 are required for its ubiquitination-mediated activation by the tumor necrosis factor receptor family member latent membrane protein 1. Mol Cell Biol 28, 6536–6546 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ning S, and Pagano JS. (2010). The A20 deubiquitinase activity negatively regulates LMP1 activation of IRF7. J Virol 84, 6130–6138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohashi M, Holthaus AM, Calderwood MA, et al. (2015). The EBNA3 family of Epstein-Barr virus nuclear proteins associates with the USP46/USP12 deubiquitination complexes to regulate lymphoblastoid cell line growth. PLoS Pathog 11, e1004822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ong SE, Blagoev B, Kratchmarova I, et al. (2002). Stable isotope labeling by amino acids in cell culture, SILAC, as a simple and accurate approach to expression proteomics. Mol Cell Proteomics 1, 376–386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orlowski RZ. (1999). The role of the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway in apoptosis. Cell Death Differ 6, 303–313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinto SM, Nirujogi RS, Rojas PL, et al. (2015). Quantitative phosphoproteomic analysis of IL-33-mediated signaling. Proteomics 15, 532–544 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saha A, Murakami M, Kumar P, Bajaj B, Sims K, and Robertson ES. (2009). Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigen 3C augments Mdm2-mediated p53 ubiquitination and degradation by deubiquitinating Mdm2. J Virol 83, 4652–4669 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito S, Murata T, Kanda T, et al. (2013). Epstein-Barr virus deubiquitinase downregulates TRAF6-mediated NF-kappaB signaling during productive replication. J Virol 87, 4060–4070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarkari F, Sanchez-Alcaraz T, Wang S, Holowaty MN, Sheng Y, and Frappier L. (2009). EBNA1-mediated recruitment of a histone H2B deubiquitylating complex to the Epstein-Barr virus latent origin of DNA replication. PLoS Pathog 5, e1000624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satpathy S, Wagner SA, Beli P, et al. (2015). Systems-wide analysis of BCR signalosomes and downstream phosphorylation and ubiquitylation. Mol Syst Biol 11, 810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shackelford J, and Pagano JS. (2004). Tumor viruses and cell signaling pathways: Deubiquitination versus ubiquitination. Mol Cell Biol 24, 5089–5093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shackelford J, and Pagano JS. (2005). Targeting of host-cell ubiquitin pathways by viruses. Essays Biochem 41, 139–156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu N, Tanabe-Tochikura A, Kuroiwa Y, and Takada K. (1994). Isolation of Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)-negative cell clones from the EBV-positive Burkitt's lymphoma (BL) line Akata: Malignant phenotypes of BL cells are dependent on EBV. J Virol 68, 6069–6073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takada K. (1984). Cross-linking of cell surface immunoglobulins induces Epstein-Barr virus in Burkitt lymphoma lines. Int J Cancer 33, 27–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takada K, Horinouchi K, Ono Y, et al. (1991). An Epstein-Barr virus-producer line Akata: Establishment of the cell line and analysis of viral DNA. Virus Genes 5, 147–156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teplova M, Malinina L, Darnell JC, et al. (2011). Protein-RNA and protein-protein recognition by dual KH1/2 domains of the neuronal splicing factor Nova-1. Structure 19, 930–944 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong Z, Kim MS, Pandey A, and Espenshade PJ. (2014). Identification of candidate substrates for the Golgi Tul1 E3 ligase using quantitative diGly proteomics in yeast. Mol Cell Proteomics 13, 2871–2882 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsao SW, Tsang CM, To KF, and Lo KW. (2015). The role of Epstein-Barr virus in epithelial malignancies. J Pathol 235, 323–333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Gent M, Braem SG, de Jong A, et al. (2014). Epstein-Barr virus large tegument protein BPLF1 contributes to innate immune evasion through interference with toll-like receptor signaling. PLoS Pathog 10, e1003960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vizcaino JA, Csordas A, del-Toro N, et al. (2016). 2016 update of the PRIDE database and its related tools. Nucleic Acids Res 44, D447–D456 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vockerodt M, Yap LF, Shannon-Lowe C, et al. (2015). The Epstein-Barr virus and the pathogenesis of lymphoma. J Pathol 235, 312–322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang JT, Yang PW, Lee CP, Han CH, Tsai CH, and Chen MR. (2005). Detection of Epstein-Barr virus BGLF4 protein kinase in virus replication compartments and virus particles. J Gen Virol 86, 3215–3225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitehurst CB, Ning S, Bentz GL, et al. (2009). The Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) deubiquitinating enzyme BPLF1 reduces EBV ribonucleotide reductase activity. J Virol 83, 4345–4353 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitehurst CB, Vaziri C, Shackelford J, and Pagano JS. (2012). Epstein-Barr virus BPLF1 deubiquitinates PCNA and attenuates polymerase eta recruitment to DNA damage sites. J Virol 86, 8097–8106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu P, Duong DM, Seyfried NT, et al. (2009). Quantitative proteomics reveals the function of unconventional ubiquitin chains in proteasomal degradation. Cell 137, 133–145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang YC, Yoshikai Y, Hsu SW, Saitoh H, and Chang LK. (2013). Role of RNF4 in the ubiquitination of Rta of Epstein-Barr virus. J Biol Chem 288, 12866–12879 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida T, Higuchi T, Hagiyama H, Strasser A, Nishioka K, and Tsubata T. (2000). Rapid B cell apoptosis induced by antigen receptor ligation does not require Fas (CD95/APO-1), the adaptor protein FADD/MORT1 or CrmA-sensitive caspases but is defective in both MRL-+/+ and MRL-lpr/lpr mice. Int Immunol 12, 517–526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan J, Cahir-McFarland E, Zhao B, and Kieff E. (2006). Virus and cell RNAs expressed during Epstein-Barr virus replication. J Virol 80, 2548–2565 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong J, Kim MS, Chaerkady R, et al. (2012). TSLP signaling network revealed by SILAC-based phosphoproteomics. Mol Cell Proteomics 11, M112..017764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The MS data have been deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium (http://proteomecentral.proteomexchange.org) through the PRIDE partner (Vizcaino et al., 2016) repository with the dataset identifier PXD004562.