Abstract

This review describes the various fasts observed by adherents of the Jain religion. It attempts to classify them according to their suitability for people with diabetes and suggests appropriate regime and dose modification for those observing these fasts. The review is an endeavor to encourage rational and evidence-based management in this field of diabetology.

Keywords: Diabetes, fasting, India, insulin, Jain, religion

INTRODUCTION

In India, people celebrate festivals by fasting, feasting, or both. “Upavaasa,” a Sanskrit word for fasting, is formed from “upa” which means near and “vaasa” which means to stay, i.e., to stay near God. India is a land of many religions, all of which have fasting as an integral part of life. Gandhiji used fasting as a formidable tool to protest and prevailed over the British. Therefore, the practice of effective diabetes care is incomplete without the knowledge of management of a fasting individual with diabetes.

THE JAIN FASTS

Jainism is an important religion of India. Fasting is interwoven in the Jain lifestyle. Fasting is a simple and proven way to cleanse one's body, including one's bad karma. It espouses the main tenet of Jain philosophy, which is to absolve oneself of desire. Jain fasts can last from 1 day to more than a month.[1,2,3] This review builds upon an earlier publication which has focused on the glycemic management of feasts, fasts, and festivals, as observed in the Hindu religion.[1]

There are several types of fasting in Jainism:

Complete fasting: Giving up food and water completely for a period

-

Partial fasting:

- Eating less than you need to avoid hunger

- Limiting the number of items of food eaten

- Giving up favorite foods.

During the pious occasion of Paryushana, Jains observe fasts of different types and of different duration. The duration of Paryushana is 8 days for Shwetambar Jains and 10 days for Digambar Jains. In this, people either keep ekasana or upavas, which differs from person to person. Even within the same families, different members may keep different types of fasts. In the Digambar sect, Shravakas do not take food and/or water (boiled) more than once in a day when observing fasts, while those of the Shwetambar sect observing a fast survive on boiled water, which is consumed only between Sunrise and Sunset.

Majority of Jains observe what is known as the “Ratri Bhojan Tyag,” in which they do not eat anything after Sunset. Some abstain from water during this time as well. For many working people, it is difficult to have an early evening meal, so the majority follow “Ratri Bhojan Tyag” only during Paryushan.

PERSON-CENTERED APPROACH

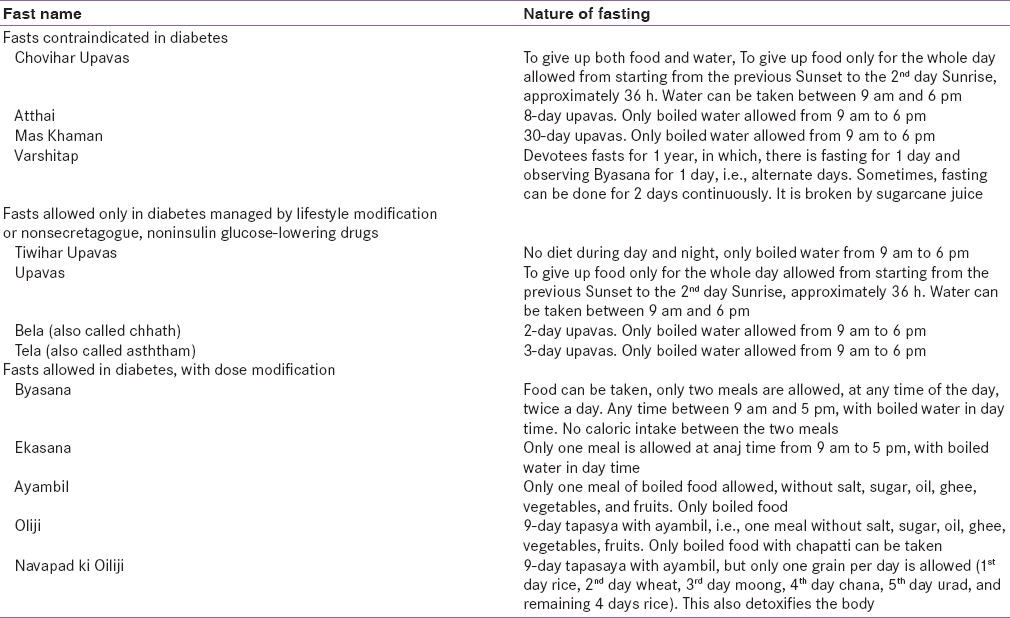

Just as other religions provide special concessions to their followers who are ill or traveling or in some way unable to keep fasts, so does the Jain religion. There are many ways in which a follower of the Jain religion can offer his/her prayer and perform a fast. A doctor who is well informed of the methods of fasting in the Jain religion can easily devise a safe, yet fulfilling fast plan, and craft an effective management strategy. The doctor can request the patient to observe one type of fast which is less demanding on the patient's body instead of the ones which require significant caloric restriction and staying without water or food for a long time. A religious leader of the Sthanak Shwetamber sect at Indore is of the view that just by eating less, one can offer prayer, and this too will be considered a fast. The various Jain fasts are classified from a diabeto-centric viewpoint in Table 1.

Table 1.

Jain fasts and diabetes

PREFAST COUNSELING/ASSESSMENT

Discussion about fasting should be initiated prior to the fast.[1,4] This should include the potential discomforts and risks of fasting, and means of mitigating them. The person's exact perspective of fasting, including duration of fast, allowance for liquids and snacks during the day, and acceptance of sublingual foods and freedom to break the fast in case of significant discomfort must be clarified. Prefast assessment comprises comprehensive history taking, physical examination, and investigations aimed at identifying stigmata of target organ damage so that strategies can be made to optimize health during fasts. Factors that may increase the risk of hypoglycemia, hypoglycemia unawareness, and dehydration must be noted. Prefast counseling should include an explanation of the symptoms of hypoglycemia and hypoglycemia awareness training.[5]

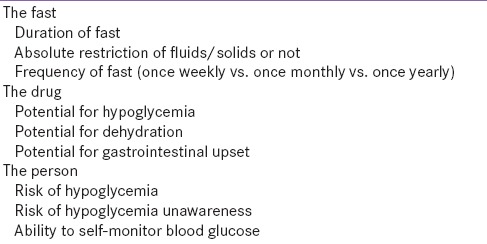

The concept of shared decision-making and person-centeredness must be followed in letter and inspirit while considering whether a particular individual can fast safely or not.[6] While some fasts are contraindicated, other may be allowed with appropriate dose modification of glucose-lowering therapy [Table 2]. Risk stratification is necessary for many persons with diabetes, especially those on insulin.[7] This needs a comprehensive assessment as shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Factors influencing the approach to glucose-lowering drug treatment during fasting

GLYCEMIC MANAGEMENT OF JAIN FASTS

All Jain fasts can be divided into three categories, with regard to their suitability for persons living with diabetes. While some should be strictly avoided by all persons with diabetes, others may be attempted, with caution, under medical supervision, by those controlled on diet and exercise.

HIGH-RISK FASTS

Certain fasts such as tiwihar upavas, upavas, bela (chhath), and tela (asththam) are discouraged in persons taking any form of glucose-lowering therapy. However, persons on once weekly glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor analogs (GLP1RA) may be able to observe these fasts safely. Prudence dictates that due doses of once weekly GLP1RA should be postponed till the completion of fasting: Posologic instructions allow for a 3-day delay in the dose administration of dulaglutide or exenatide QW. Persons on nonsecretagogue therapy, for example, metformin, DPP4i, α-glucosidase inhibitor, or sodium-glucose co-transporter 2 (SGLT2i) may omit their therapy on the day of complete upavas; however, such fasting should be allowed only in healthy individuals, under close medical supervision.

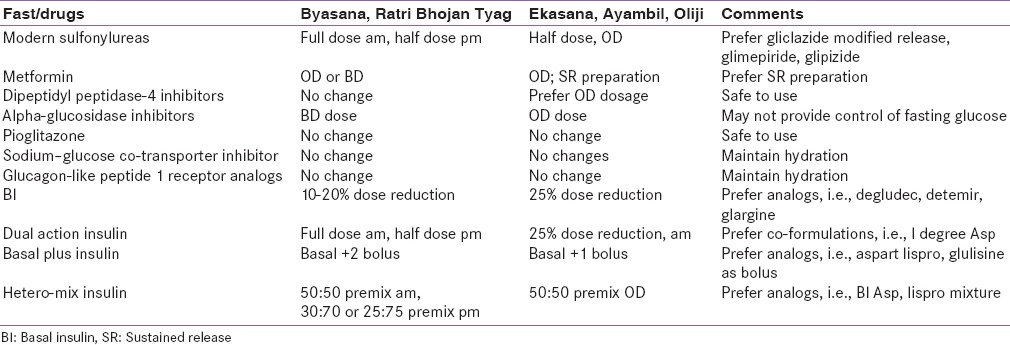

LOW-RISK FASTS

Byasana, Ekasana, and Ratri Bhojan Tyag can be practiced by the majority of healthy Type 2 diabetes, provided appropriate regime and dose adjustments are made. Most oral glucose-lowering drugs including sensitizers, indirectly acting secretagogues, glucose absorption inhibitors, and excretion enhancers can be used safely.[8] Directly-acting secretagogues, including modern sulfonylureas and meglitinides, may require dose reduction.[9] GLP1RA, both once daily and once weekly preparations, need no modification in dose.[10]

All oral glucose-lowering drugs can be used in Ratri Bhojan Tyag albeit with modification. The evening dose can be a DDP IV inhibitor, SGLT2i, or a glucosidase inhibitor. Secretagogues should preferably be avoided, or taken in half dose, in patients wish to fast from dusk to dawn. SGLT2i should be avoided during prolonged periods of abstinence from water. The evening dose should preferably be avoided, or taken in half dose, in patients wish to fast from dusk to dawn.

Insulin-based regimens may need to be modified[7] to suit Jain fasts. Persons who practice Ratri Bhojan Tyag should prefer insulin analogs with a lower risk of nocturnal hypoglycemia. If basal insulin is inadequate, prandial coverage may be achieved by either adding a rapid-acting insulin analog or by using dual action insulin. The variable duration of Ratri Bhojan Tyag fast, with fasting period extending to 14–15 h during winter, call for the use of flexible insulin regimens and preparations. Insulin degludec aspart (I Deg Asp), which need not necessarily be injected at antipodal meals,[11] is a suitable option for Jains who practice Ratri Bhojan Tyag. An intensive regimen of two rapid-acting insulin and one dual-acting regimen may be required if a twice daily strategy proves inadequate.

During intensive fast with strict restrictions, for example, Byasana and Ekasana, further modification in insulin regimens may be required [Table 3]. Postfast counseling and review[12] is done to evaluate the patient's health and to lessons learned for review the future periods of fasting.

Table 3.

Dose modification in Jain fasts

CONCLUSION

This review has attempted to describe and classify Jain fasts from a diabeto-centric viewpoint. The author suggests rational therapeutic modification which may allow devout adherent to fast in a safe and fulfilling manner. It is hoped that this collation helps achieve better glycemic management for those who observe Jain fasts, and stimulates scientific research in this field of diabetology.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kalra S, Bajaj S, Gupta Y, Agarwal P, Singh SK, Julka S, et al. Fasts, feasts and festivals in diabetes-1: Glycemic management during Hindu fasts. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2015;19:198–203. doi: 10.4103/2230-8210.149314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jain Rituals and Ceremonies. [Last accessed on 2016 Apr 26]. Available from: http://www.fas.harvard.edu/~pluralsm/affiliates/jainism/workshop/Sutaria%20Jain%20Rituals.pdf .

- 3.Other Austerities. [Last accessed on 2016 Apr 26]. Available from: http://www.jainworld.com/philosophy/austerities_others.asp .

- 4.Jaleel MA, Raza SA, Fathima FN, Jaleel BN. Ramadan and diabetes: As-Saum (The fasting) Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2011;15:268–73. doi: 10.4103/2230-8210.85578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ahmad J, Pathan MF, Jaleel MA, Fathima FN, Raza SA, Khan AK, et al. Diabetic emergencies including hypoglycemia during Ramadan. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2012;16:512–5. doi: 10.4103/2230-8210.97996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jawad F, Kalra S. Diabetes care in Ramadan: An exemplar of person centered care. J Pak Med Assoc. 2015;65(5 Suppl 1):S1–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pathan MF, Sahay RK, Zargar AH, Raza SA, Khan AK, Ganie MA, et al. South Asian consensus guideline: Use of insulin in diabetes during Ramadan. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2012;16:499–502. doi: 10.4103/2230-8210.97992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kelwade J, Sethi BK, Vaseem A, Nagesh VS. Sodium glucose co transporter 2 inhibitors and Ramadan: Another string to the bow. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2014;18:874–5. doi: 10.4103/2230-8210.141397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kalra S, Aamir AH, Raza A, Das AK, Azad Khan AK, Shrestha D, et al. Place of sulfonylureas in the management of type 2 diabetes mellitus in South Asia: A consensus statement. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2015;19:577–96. doi: 10.4103/2230-8210.163171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pathan MF, Sahay RK, Zargar AH, Raza SA, Khan AK, Siddiqui NI, et al. South Asian consensus guideline: Use of GLP-1 analogue therapy in diabetes during Ramadan. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2012;16:525–7. doi: 10.4103/2230-8210.98003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kalra S. Insulin degludec aspart: The first co-formulation of insulin analogues. Diabetes Ther. 2014;5:65–72. doi: 10.1007/s13300-014-0067-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jawad F, Kalra S. Ramadan and diabetes management – The 5 R’s. J Pak Med Assoc. 2015;65(5 Suppl 1):S79–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]